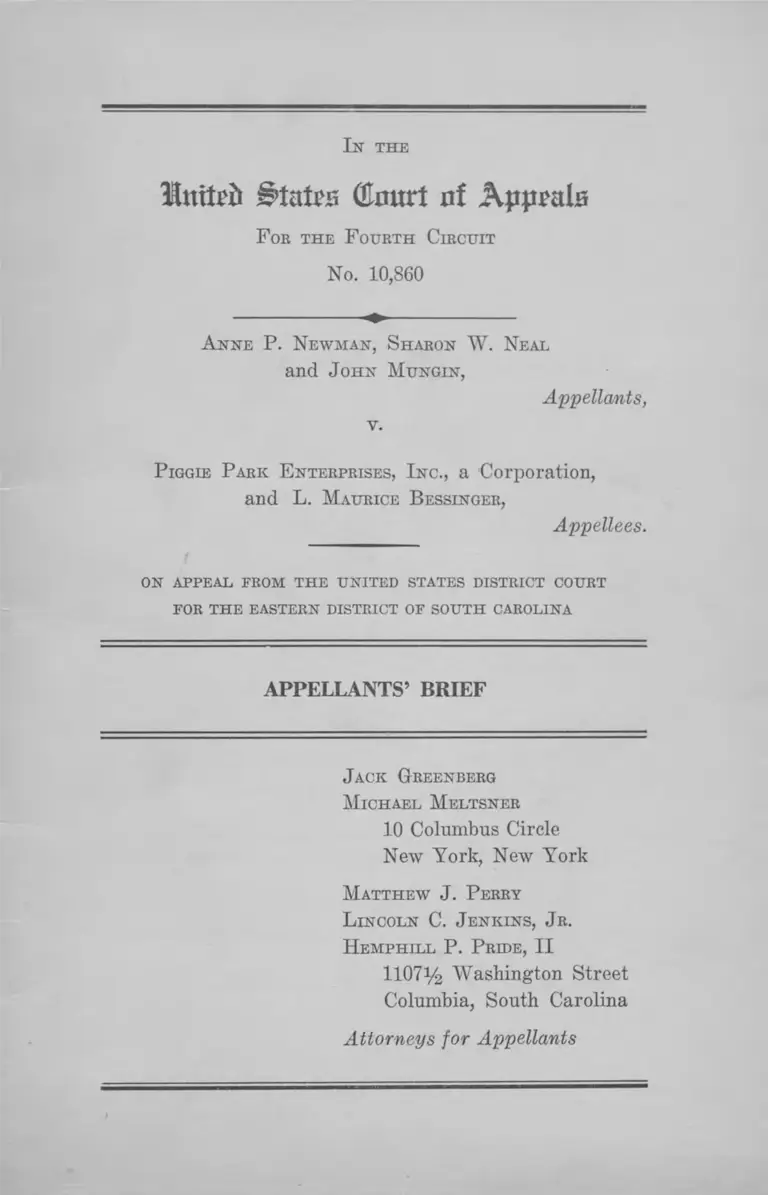

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises Appellants' Brief, 1966. 5dfa5789-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a45bb7f3-5841-4ea1-9837-1aab1e757435/newman-v-piggie-park-enterprises-appellants-brief. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

Uttiteb States (Huurt af Appeals

F or t h e F ourth Circuit

No. 10,860

In the

A n n e P. N ew man , S haron W . N eal

a n d J ohn M u n g in ,

Appellants,

v.

P iggie P ark E nterprises, I n c ., a Corporation,

and L. M aurice B essinger,

Appellees.

o n a p p e a l fr o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d ist r ic t co urt

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J ack Greenberg

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

M atthew J . P erry

L incoln C. J e n k in s , J r.

H e m ph il l P. P ride, II

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement .......................................................................... 1

Questions Presented ................................................... 8

A rgument :

I. The District Court Erred by Excluding Drive-in

Eating Places From Coverage as Public Ac

commodations Within the Meaning of Title II

of the Civil Bights Act of 1964 ...................... 9

II. Negro Appellants Are Entitled to a Reasonable

Attorney’s F e e ........................................................ 21

Conclusion ....... 27

T able of Cases

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321 F. 2d

494 (4th Cir. 1963) ...................................................... 26

Franklin v. Peppers, 9 R.R. L. Rept. 1843 (M. D. Fla.

1964) ...... 24

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 ..................................... 22

Guardian Trust Co. v. Kansas City Southern, 28 F. 2d

283 (8th Cir. 1928) .................................................... 25

Katzenbach v. McClung, 371 U. S. 291 ......................... 24

McClung v. Katzenbach, 233 F. Supp. 815 (N. D. Ala.

1964)

PAGE

14

11

Rolax v. Atlantic Coastline Railroad Co., 186 F. 2d

473 (4th Cir. 1951) ....................................................... 25

Sprague v. Taconic National Bank, 307 U. S. 161

(1939) ............. ........................ .................. ..... ............ 25

Twitty v. Vogue Theatre Corp., 242 F. Supp. 281 (M. D.

Fla. 1965) ...................................................................... 23

Willis v. Pickrick, 231 F. Supp. 396 (N. D. Ga. 1964) ..20, 21

Statutes Involved:

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

42 U. S. C. §2000a .................................................. 1

§2000a-l................................................ 22

§2000a-2................................................ 22

§2000a-3................................ 21

§2000a-5................................................ 22

§2000a-(3) ( a ) ....................................... 22

§2000a-(3) ( b ) ................................. 1, 22,24

§2000a-(b) (1 ) ....................................... 18

§2000a-(b) (2) .......................7,9,11,19, 21

§2000a-(b) (3 ) .....................................19, 24

§2000a-(c) (1) ....................................... 19

§2000a-(c)(2)

§2000a-(c)(3)

PAGE

.6, 14, 20, 21, 24

........................ 7,19

Ill

Other Authorities:

110 Cong. Rec. 1449, 1569 (Daily Ed., January 31,

1964) .............................................................................. 13

110 Cong. Rec. 1456 (Daily Ed., Jan. 31, 1964) . 14

110 Cong. Rec. 7177 (Daily Ed., Apr. 9, 1964) . 15

110 Cong. Rec. 1901 (Daily Ed., Feb. 5, 1964) .............. 14

110 Cong. Rec. 1902 (Daily Ed., February 5, 1964)

at 1902 ............................................................................ 15

110 Cong. Rec. 14201 (June 17, 1964) ............. 22

110 Cong. Rec. 14214 (June 17, 1964) ............. 23

2 U. S. Code & Cong. News, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. 1964,

pp. 2395, 2410, 2424, 2465, 2480, 2494 .......................... 13

House Committee on the Judiciary, 2 U. S. Cong, and

Admin. News, 1964, p. 2391 .......................................... 20

Hearings Before Comm, on Commerce, U. S. Senate,

88th Cong., 1st Sess. Part I, pp. 61, 333 ..................13,18

Hearings Before the Comm, on the Judiciary 88th

Cong. 1st Sess. Part II pp. 1374-75 ............................. 18

Hearings Before Comm, on Judiciary, House of Rep

resentatives, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. Part IV, p. 2701 .... 13

77 Harv. L. Rev. 1135 (1964) ...................................... 25

PAGE

In the

llmti'ii i'tutni (Enurl of Appeals

F oe t h e F ourth Circuit

No. 10,860

A n n e P. N ew man , S haron W. N eal

an d J ohn M u n g in ,

Appellants,

v .

P iggie P ark E nterprises, I n c ., a Corporation,

and L. M aurice B essinger,

Appellees.

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement

This is a class action for an injunction brought by Negro

appellants against the corporate operator of a restaurant

chain, and its president and principal stockholder, pur

suant to Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C.

§§2000a et seq. The district court denied relief as to all

but one of six restaurants owned by the corporation and

declined to order payment of counsel fees as authorized by

42 U. S. C. $2000a-3(b).

The complaint was filed in the district court for the

district of South Carolina, December 18, 1964 alleging, in

summary, that Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., operates

restaurants at various locations in South Carolina; that

2

operation of these restaurants affects commerce within

the purview of Title II and that Negroes are refused ser

vice at the restaurants pursuant to corporation policy

(la-7a).

The corporation and its President answered by denying

that Negroes are refused service at the restaurants; that

their operations affect commerce; and that they operated

any place of “public accommodation” as that term is de

fined in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.1 It was asserted

that Title II is unconstitutional in violation of the Com

merce Clause (Art. I, §8); the privileges and immunities

clause (Art. IV, §2); the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment; and the Thirteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States. In

addition, the corporation President L. Maurice Bessinger,

alleged that service of food to Negroes, as required by

Title II, violated his freedom of religion as protected by

the First Amendment (8a-10a; lla-13a; 17a-20a).

The facts adduced at a trial held April 4 and 5, 1966

(21a-205a) and as found by the district court are not

materially disputed. The corporation operates six eating

places, five of which are drive-in facilities (211a-212a). At

three of these drive-ins there are no chairs or stools; on

premises food consumption takes place in a customers auto

mobile. In addition to automobile service, two of the five

drive-ins maintain “two or three small tables . . . with a

couple of chairs at each table” (183a-184a). The sixth

facility, Little Joe’s Sandwich Shop, contains tables and

1 Defendants filed an answer February 5, 1965, an amended

answer August 23, 1965 and were permitted by the district court

to file a second amended answer March 19, 1964. All three plead

ings generally deny the allegations of the complaint.

3

chairs for approximately sixty customers and has no drive-

in facilities (212a). The district court summarized the

manner of operation of these restaurants as follows: “In

order to be served at one of the drive-ins a customer drives

upon the premises in his automobile and places his order

through an intercom located on the teletray immediately

adjacent to and left of his parked position. After pushing

a button located on the teletray his order is taken by

an employee inside the building who is generally out of

sight of the customer. When the order is prepared a curb

girl then delivers the food or beverage to the customer’s

car and collects for same. This is generally the only con

tact which any of defendant’s employees has with any cus

tomer unless additional service is desired. The orders are

served in disposable paper plates and cups, and may be

consumed by the customer in his automobile on the premises

or after he drives away, solely at his option. There are no

tables and chairs, or counters, bars or stools at any of the

drive-ins sufficient to accommodate any appreciable number

of patrons. The service is geared to service in the cus

tomers’ cars” (212a, 213a). On the basis of testimony by

Mr. Bessinger the Court found that at the five drive-ins

off-the-premises food consumption averages fifty percent

during the year:

“Q. Mr. Bessinger, with reference to the total volume

of your business, do you know how much of your

business is carry out, or take away business from your

drive-ins? A. Yes. Of course, as I said, we try to en

courage this to the maximum degree. This would aver

age 50%. Carry out would average 50%. I say aver

age, because in the real cold temperature it would

jump up to eighty to ninety percent; in the real hot

4

temperature it would also jump up to eighty to ninety

percent. So it will have an overall percentage of my

business that I know for a fact is carried back to the

office or carried back home or carried on a picnic, what

have you” (213a).

“Little Joe’s Sandwich Shop”, is operated as a “cafeteria

type sandwich shop” specializing in barbecue. Its food

sales are almost entirely consumed on the premises. The

sandwich shop is located in the prime shopping area of

Columbia’s Main Street; whereas the five drive-in restau

rants are all located on interstate highway routes across

the state (212a, 214a).

Two appellants were denied service on August 12, 1964

at the restaurant located on U. S. Highway 76 and 378 in

Columbia. At first a waitress approached their automobile

but seeing their race went back into the building without

taking their order. Then a man with an order pad came to

their car, but refused to take their order, “and gave no

reason or excuse for this denial of service, although other

white customers were being served there at that time”

(214a). Although the second amended answer, filed less

than two months before trial denied exclusion (17a) both

President Bessinger, a corporation bookkeeper, and a

waitress admitted that Negroes are only served on a

kitchen door-take out basis2 (160a, 169a, 172a, 189a). The

court found denial of full and equal service to Negroes

at all six eating places to be “completely established” by

the evidence (215a).

2 The limited Negro customers who are served must place and

pick up their orders at the kitchen windows and are not permitted

to consume their purchases on the premises.

5

The district court found “at least” forty per cent of the

approximately $230,000.003 in food purchased by the restau

rants each year moved in commerce on the basis of “defen

dant’s admission that from eighteen to twenty five per cent

of its ‘food’ in a finished or ready-for-use form moved in

commerce . . . also the . . . large quantities of live cattle,

hogs and chickens purchased by defendant’s suppliers from

outside of the state and slaughtered and processed within

the state before delivery to defendant, which were not in

cluded hy defendant in its out-of-state percentages, along

with other foodstuffs purchased by it which were shipped

into the state and purchased herein, together with such

related items as sugar, salt, pepper, spices and sauces which

admittedly moved in commerce . . . ” (221a) (emphasis

supplied). Testimony of defendant’s suppliers and book

keeper detail the large amounts of meat, poultry, beverages

and other items obtained from producers and suppliers

outside of South Carolina (216a-220a).

The court also found as an “inescapable conclusion” that

the restaurants serve “many interstate travelers” in view

of the “limited” action taken by the corporation to deter

mine the travel status of its customers (215a-216a). Piggie

Park displays on each of its establishments one small sign

located generally in the front window advising that it does

not serve interstate travelers and its newspaper advertise

ments include a notice in small print at the bottom of the

ad advising that “we do not serve interstate travelers.”

However, at the drive-ins the defendants only claim to

3 The corporation bookkeeper stated total food purchases as

follows (220a) :

1963- 64 — $240,565.58

1964- 65 $222,845.26

1965 (six months) $122,724.13

6

attempt to determine a customer’s travel status after his

order is prepared and actually delivered to his automobile.4

No inquiry whatever is ever made of any customers who

are riding in an automobile with South Carolina license

plates. No effort is made to determine whether a Negro

customer who purchases food on a take-out basis is an

interstate traveler. No mention of the practice of not serv

ing interstate travelers is included in any of Piggie Park’s

radio advertisements although all five of the drive-ins are

located at “strategic” positions upon main and much trav

eled interstate highways. No steps are taken at “Little

Joe’s Sandwich Shop” to determine whether a customer

is actually an interstate traveler (215a-216a).

D istrict C ourt: Conclusions o f Law

The court found that operation of all six of the res

taurants “affect commerce” within the meaning of Title II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §2000a-(c) (2)

as they serve a substantial portion of food which moves in

interstate commerce and also serve interstate travelers.

Regardless of whether 18 per cent or 25 per cent (figures

supplied by the corporation which excluded goods originat

ing out of South Carolina but processed or slaughtered

within the state) or “at least forty per cent” (the proportion

determined by the court) the district court had “no hesi

tancy” concluding that a “substantial” portion of food

served at the six restaurants moved in commerce (222a-

224a).

4 “If the curb girl who serves the order notices that a customer’s

car bears an out-of-state license, she is instructed to inquire whether

such customer is an interstate traveler or is residing in South

Carolina. There is testimony to the effect that if the customer

admits that he is an interstate tourist service is denied to him

although the food has been especially prepared to his order” (216a).

7

The district court found that the restaurants serve inter

state travelers on the basis of the following factors: (1)

testimony that no inquiry was made of a customer’s place

of residence; (2) all five drive-ins are located on major

interstate highways and large signs at each location ad

vertise the restaurants; (3) additional advertisements are

placed in newspapers and on radio; (4) the corporation

“employs no reasonably effective means of determining

whether its customers are inter or intra-state travelers”

(224a).

Having determined that the operation of the six eating

facilities “affect commerce” within 42 U. S. C. §2000a-

(c)(3) the court considered whether they were places of

public accommodation as defined by 42 U. S. C. §2000a-

(b)(2) to include:

“Any restaurant, cafeteria, luncheon, lunch counter,

soda fountain, or other facility principally engaged in

selling food for consumption on the premises.”

The court found that Little Joe’s Sandwich Shop was

such a facility and was covered by the Act but that the five

drive-in eating establishments were beyond its reach (225a-

228a). In the court’s view, the sandwich shop is covered

because it is “mainly engaged in serving food for on-the-

premises consumption” and caters to “walk-in customers

who are furnished chairs and tables.” The five drive-in

facilities do not have such accommodations and cater to

motorized customers, half of whom on the average consume

their food off the premises. Such facilities, the court con

cluded, are not covered by Title II {Ibid.). On the basis

of this distinction the court enjoined racial discrimination

only at the sandwich shop and not at the five drive-in

8

facilities (229a). A reasonable attorney’s fee, as sought by

appellants, was denied (Ibid.). Notice of Appeal from the

order of the district court was filed August 9, 1966.

Questions Presented

1. Whether five drive-in eating facilities which (1) deny

service to Negroes, (2) serve substantial quantities of food

moving in commerce and (3) serve interstate travelers are

excused from compliance with the provision of Title II of

tho Civil Rights Act of 1964 on the ground that an average

of fifty per cent of their customers eat on the premises.

2. Whether Negroes refused service at an eating facility,

clearly within the terms of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

are entitled to counsel fees, pursuant to congressional au

thorization, when (1) the evidence produced at trial over

whelmingly established racial discrimination and involve

ment with commerce between the states; (2) the restaurant

refused to admit facts establishing discrimination and

participation in interstate commerce prior to trial and

(3) the restaurant has failed to desegregate although

clearly required to do so by law and persists in raising con

stitutional defenses settled adverse to it by the United

States Supreme Court.

9

A R G U M E N T

I.

The District Court Erred by Excluding Drive-in Eat

ing Places From Coverage as Public Accommodations

Within the Meaning of Title II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964.

The district court enjoined racial discrimination at one

of the corporation’s restaurants hut denied relief with re

spect to five drive-in eating facilities on the ground that

Congress did not intend such facilities to come within the

statutory definition of public accommodation:

“Any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch counter,

soda fountain or other facility principally engaged in

selling food for consumption on the premises . . . ” (42

U. S. C. §2000a-(b)(2)).

In support of this conclusion the court reasoned that there

are no accommodations at the drive-ins for diners to walk

into buildings, sit down and eat5 and customers consume

their food inside their automobiles. Principal reliance was

placed on a finding that “fifty per cent of all foods served

. . . is consumed off the premises” (225a, 228a). Although

its opinion does not rely for the proposition on any par

ticular legislative debate or report, the court also con

cluded that the history of the Civil Rights Act revealed

a congressional purpose not to reach drive-in eating facili

ties.

5 The record shows that this is true with respect to only three

of the five drive-ins, the other two containing two or three tables

each (183a-184a).

10

We believe that the court seriously misconstrues the lan

guage of Title II, the intent of Congress, and the legislative

history, but even under the standard adopted by the court

(which we believe are erroneous) Negro appellants should

be entitled to relief against the five drive-in establishments.

In finding that fifty per cent of the food sold at the drive-

ins were consumed off premises the court relied on the

following testimony by Corporation President Bessinger:

“Q. Mr. Bessinger, with reference to the total vol

ume of your business, do you know how much of your

business is carry out, or take away business from your

drive-ins! A. Yes. Of course, as I said, we try to

encourage this to the maximum degree. This would

average 50%. Carry out would average 50%. I say

average, because in the real cold temperature it would

jump up to eighty to ninety percent; in the real hot

temperature it would also jump up to eighty to ninety

percent. So it will have an overall percentage of my

business that I know for a fact is carried back to the

office or carried back home or carried on a picnic, what

have you” (193a). (Emphasis supplied.)

Thus, in certain seasons as few as 10 or 20 per cent of

Piggie Park’s customers carry food off the premises; in

other seasons as few as 10% or 20% eat on the premises.

Fifty per cent is at best a yearly average which represents

wide seasonal fluctuation. Unless the Act is read to man

date an inflexible yearly standard—and its language and

history do not suggest such an interpretation—the Negro

denied service in certain seasons is denied service at a

place of public accommodation which is, even under the

district court’s construction, “principally engaged in sell

ing food for consumption on the premises.” It is not clear,

11

in light of the purposes of the Act, see infra, pp. 13-18,

why the drive-ins should be exempt because at other times

they may not be so “principally engaged.” We submit that

if an eating facility serves 90% of its patrons on premises

in “hot weather” coverage is established regardless of the

yearly average.

The legislative history is clear that Congress intended to

eliminate interference with commerce by (1) covering eat

ing facilities generally, and (2) eliminating uncertainty

with respect to coverage so that citizens and restaurateurs

would know their rights, see infra, pp. 13-18. But the same

disruption of commerce is produced by a Negro traveler’s

uncertainty, by mass demonstrations, or merely by artificial

restriction of the market whether the drive-ins are “prin

cipally engaged” (again using the district court’s construc

tion) seasonally or yearly. By requiring a yearly average

of greater than 50 percent the district court is introducing

an arbitrary element into the Act which Congress never

considered. To be sure if “principally engaged . . . ” means

what the district court believes it to mean it should be read

to cover a facility’s experience over a reasonable period

of time, but certainly high on premises food consumption

in “hot weather” is sufficient to establish coverage under

an Act intended to eliminate discrimination in all eating

facilities.

We have urged that in light of the plain purpose of the

Act the district court misapplied its own standard. In

addition, we urge that this Court repudiate that standard

itself and construe 42 U. S. C. §2000a-(b) (2) to accomplish

the ends for which it was written.

Certainly the facilities operated by the corporation are

not any less “Any restaurant, etc. . . . ” because the cus

12

tomer eats in his ear rather than at a table. The effect on

travel, trade and commerce or the evils of discrimination

which the legislative history reveals are not lessened be

cause the Negro is refused on premises food service in his

car rather than inside a building or because, if served, he

would consume his meal in his car parked on the premises

rather than at a table on the premises.6 Thus, the district

court considered the critical factor in its decision to be

that “fifty per cent of all foods served . . . is consumed off

the premises.” In the court’s view, the drive-ins were not

covered “restaurants etc. . . . ” because “ . . . one who serves

fifty per cent or less of its food which is taken and eaten

off the premises cannot be held to be principally engaged

in selling food for consumption on the premises” (emphasis

in original). “ [Principally engaged, etc. . . . ” is taken,

therefore, as a criterion for coverage under the Act. Un

less proof establishes that more than 50 per cent of the

customers of “Any restaurant, etc. . . . ” consume food on

the premises, the restaurant is not covered and may ex

clude Negroes.

We believe the court’s conclusion is erroneous for the

phrase “principally engaged in selling food for consump

tion on the premises” is directed not to the per cent of

take out orders in any particular facility but to the char

acter of the eating facility itself. Everything sold at these

drive-ins (with the exception of a small amount of bulk

barbecue) could be consumed on the premises. The food

is sold in a form which permits convenient consumption

on the premises. The decision to eat on or off premises is

solely the customer’s and the drive-ins exercise no control

over these individual decisions. Such a facility is clearly

Cf. Note 5 supra.

13

“principally engaged in selling food for consumption on

the premises.” (Emphasis supplied.)

Focus on the character of the establishment—distinguish

ing eating facilities and retail markets for example—is the

only construction consistent with the plain congressional

intent to eliminate interference with the flow of commerce

at all but an eccentric (and probably nonexistent) class of

restaurants which had slight connections with interstate

commerce and none at all with interstate travelers. To a

Negro traveler driving an interstate highway only the ex

ternal character of an eating establishment is visible. He

has no way of knowing whether 35 or 75 per cent of its

customers eat on premises or take out. All he sees is a

restaurant that obviously holds itself out as being engaged

in selling food for consumption on the premises. To make

his right to service depend on the vagaries of each restau

rant’s per cent on-premises food consumption is to inject

a variable in the statute which invites the very uncertainty

and interference with commerce which Congress sought to

eliminate. If some percentage of on-premise business must

be shown before a facility is covered one would expect some

debate in Congress on the question but we have found none

reported.

On the other hand, the legislative record show beyond

doubt that key legislators assumed coverage of virtually

all restaurants.7 Even a court which declared the Act un

7 Legislators and witnesses often spoke in terms of eating estab

lishments so as to be totally inclusive. See e.g., 2 U. S. Code &

Cong. News, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. 1964, pp. 2395, 2410, 2424, 2465,

2480, 2494; Hearings Before Comm, on Judiciary, House of Repre

sentatives, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. Part IV, p. 2701; Hearings Before

Comm, on Commerce, U. S. Senate, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. Part I,

p. 61; 110 Cong. Rec. 1449, 1569 (Daily Ed., January 31, 1964).

14

constitutional concluded as a “simple truth” that Congress

intended “to put an end to racial discrimination in all res

taurants,” McClung v. Katzenbach, 233 F. Supp. 815, 825

(N. D. Ala. 1964) reversed 379 U. S. 294.8

When Representative Willis sought to amend Section 42

U. S. C. §2000a-(c) (2) to strike “it serves or offers to

serve interstate travelers or” and insert in lieu thereof

the following: “a substantial number of the patrons it

serves are interstate travelers and . . . ” (emphasis sup

plied), 110 Cong. Rec. 1901 (Daily Ed., Feb. 5, 1964) Con

gressman Celler opposed the amendment:

This amendment would change that. Instead of being

in the disjunctive, it would be in the conjunctive, and

the Attorney General would have to prove two things.

First, he would have to prove that in a particular res

taurant the service is to a substantial number of inter

state travelers. Not merely to interstate travelers but

to a ‘substantial’ number of interstate travelers. And,

in addition, he would have to prove that a substantial

portion of the food which is served has moved in inter

state commerce. That is a proof that is twofold, and

it makes it all the more difficult for the Attorney Gen

eral to establish that proof. It cuts, as it were, the

import of the words ‘affect commerce,’ which are on

page 43, line 24, in half. You have this situation, for

example. Whereas, in the proposal before us, many

restaurants are within the orbit of the prohibition of

8 In presenting the Bill, Congressman Celler, Chairman of the

Judiciary Committee, said:

“All we do here is to apply what those 30 States are now doing

and what the District of Columbia is now doing to the rest

of the States so that there shall be no discrimination in places

of public accommodation privately owned. . . . ” 110 Cong.

Rec. 1456 (Daily Ed., January 31, 1964).

15

the bill, many of such restaurants would not be covered

under this amendment. Take, for example, a roadside

restaurant which sells home-grown food which does

not come from outside the State. That would not be

covered under the amendment. Furthermore, a local

restaurant which serves local people with food coming

from all over the United States would not be covered

under the amendment. Let me repeat that

“We have very significant results here. Instead of

having all restaurants covered, under this amendment

you would eliminate the restaurant, for example, a

roadside restaurant that sells home-grown food. You

would also eliminate the local restaurant that serves

local people with food that comes from all over the

country. I do not think we want such a situation to

develop, and for that reason I believe that the whole

purpose of covering restaurants would be defeated by

this amendment” (110 Cong. Rec. 1902 (Daily Ed.

February 5, 1964) at 1902) (emphasis supplied).

The amendment was rejected at p. 1903.

In the Senate, Senator Magnuson, Chairman of the Com

merce Committee, presenting an analysis of Title II, said:

“Most public eating places would be within the ambit

of Title II because of their connection with interstate

travelers or interstate commerce. And in some areas,

public eating places would come within the ambit of

Title II, because of the factor of State action.

“At any rate, it is clear that few, if any, proprietors

of restaurants and the like would have any doubt

whether they must comply with the requirements of

Title II.” 110 Cong. Rec. 7177 (Daily Ed., Apr. 9,

1964) (emphasis supplied).

16

Attorney General Kennedy stated the central purpose of

the Act as follows:

Arbitrary and unjust discrimination in places of

public accommodation insults and inconveniences the

individuals affected, inhibits the mobility of our citi

zens, and artificially burdens the free flow of commerce.

Consider, for instance, the plight of the Negro trav

eler in some areas of the United States.

For a white person, traveling for business or pleas

ure ordinarily involves no serious complications. He

either secures a room in advance, or stops for food

and lodging when and where he will.

Not so the Negro traveler. He must either make

elaborate arrangements in advance, if he can, to find

out where he will be accepted, or to subject himself

and his family to repeated humiliation as one place

after another refuses them food and shelter.

He cannot rely on the neon signs proclaiming “Va

cancy,” because too often such signs are meant only

for white people. And the establishments which will

accept him may well be of inferior quality and located

far from his route of travel.

The effects of discrimination in public establish

ments are not limited to the embarrassment and frus

tration suffered by the individuals who are its most

immediate victims. Our whole economy suffers. When

large retail stores or places of amusement, whose goods

have been obtained through interstate commerce, arti

ficially restrict the market to which these goods are

offered, the Nation’s business is impaired.

Business organizations in this country are increas

ingly mobile and interdependent, and they tend to ex

17

pand beyond the areas of their origins. As they find it

necessary or feasible to engage in regional or national

operations, they establish plants and offices in various

parts of the country. These installations benefit the

localities in which they are established and affect the

commerce of the country. Artificial restrictions on

their employees limit this type of mobility and its bene

fits to the national economy.

Further, if we add together only a minor portion

of all the discriminatory acts throughout the country

in any one year which deny food and lodging to

Negroes, it is not difficult at all to see how, in the

aggregate, interstate travel and interstate movement

of goods in commerce may be substantially affected.

No matter—in Mr. Justice Jackson’s words—“how

local the operation which applies the squeeze,” com

merce in these circumstances discouraged, stifled, and

restrained among the States as to provide an appro

priate basis for congressional action under the com

merce clause.

Mr. Chairman, discrimination in public accommoda

tions not only contradicts our basic concepts of liberty

and equality, but such discrimination interferes with

interstate commerce and the development of unob

structed national market.

We pride ourselves on being a people who are gov

erned by laws. This pride is justified when we provide

legal means for the settlement of human differences

and the satisfaction of justified complaints. Mass

demonstrations disrupt the community in which they

occur; they also disrupt the country as a whole. But

no one can in good faith deny that the grievances which

these demonstrations protest against are real. (Hear

18

ings Before the Comm, on the Judiciary, 88th Cong.

1st Sess. Part II, pp. 1374-75.

And Congress was aware that the evils to be eliminated

by the Act could be produced by discrimination at drive-in

restaurants:

Reverend Mack. We have a drive-in that insists

on continuing that particular practice of segregation.

Princess Anne is 14 miles on the farther side of us

going toward the Virginia line. Many of the students

from the Maryland State College who take part in

demonstrations in Cambridge, and what have you,

pass through Salisbury right by this particular drive-

in. That has been one of our concerns, that we might

be able to open this particular drive-in in order that

those students might not stop there, because with all

of our major restaurants open, they are still looking

at that particular place every time they pass. Why is

it that this place continually keeps its segregated pat

tern?

Senator Monroney. And a demonstration against

that might spread.

Reverend Mack. It could spread, yes.

(Hearings, Senate Commerce Committee, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess. p. 333.)

It should be noted that although the district court found

legislative intent to exclude drive-ins it cited no authority

for this conclusion in the legislative history.

The congressional intent to cover virtually all restau

rants just as clearly as Congress wished to cover almost

all hotels, motels, etc., by 42 U. S. C. §§2000a-(b) (1) and

19

(c)(1) and almost all motion picture houses, etc., by

§§2000a-(b) (3) and 2000a-(c)(3) is defeated by the con

struction of §2000a-(b) (2) adopted below. In contrast, re

stricting “principally engaged . . . ” to modifying only

“other facility” is consistent with the congressional intent

for the legislative history apparently does not contain any

discussion of the facilities which would be excluded from

coverage by the district court’s construction. This would

be highly unusual if Congress intended to restrict the

reach of the statute. Far more reasonable is the notion

that after enumerating a variety of eating places which

it intended to bring within the terms of the statute Con

gress defined the remainder of class which it intended to

cover—eating facilities in general—in terms of a common

characteristic, namely, sale of food which may be and con

veniently is consumed on the premises. The “principally

engaged” criteria serves to keep the class of “other” facili

ties from converging on the classes of other establishments

which sell food such as food markets by defining the char

acter of the facilities dealt with in §2000a-(b) (2).9

In short, the legislative purpose requires that the dis

junctive “or” in §2000a-(b) (2) limit the qualifying phrase

“other facility.” In other words, “or other facility prin

9 Without the explanatory phrase “principally engaged etc.

. . . ” the statute would read:

Any restaurant cafeteria, lunchroom lunch counter, soda foun

tain or other facility

By inserting “principally engaged etc. . . . ” Congress added lan

guage which made the ambiguous phrase “other facility” definite

and clearly demonstrated the congressional intent to reach eating

facilities generally. Indeed if Congress had not done so a court

faced with the question would have likely construed “other facility”

to mean other eating facilities and not other food sellers such as

markets. “Principally engaged in selling food for consumption

on the premises” merely provides such a definition of eating facili

ties by referring to their most prominent common characteristic.

20

cipally engaged in selling food for consumption on the

premises” means only “and similar establishment,” a class

in which drive-in eating facilities clearly fit if for some

reason, not apparent to us, they are not restaurants.10

Otherwise there would he no explanation for the numerous

statements by key legislators and by the Attorney General

which indicate that eating places as a class are covered.

There can be no question but that the operation of all

six of the eating places involved “affect commerce” as found

by the district court. “At least” forty percent of the food

sold by the restaurants has moved in commerce, the por

tion sold is “substantial,” 11 42 U. S. C. §2000a-(c)(2), un

less the word is to be robbed of its usual meaning.12 Like

wise, the record clearly establishes that these eating places

serve interstate travelers. This is demonstrated by a num

ber of factors but conclusively by the failure to determine

10 As noted by the district court this construction is also sup

ported by the report of the House Committee on the Judiciary, 2

U. S. Cong, and Admin. News, 1964, pp. 2391, 2395 which states:

Section 201(b) defines certain establishments to be places of

public accommodation if their operations affect commerce . . .

these establishments are . . . (2) restaurants, lunch counters

and similar establishments, including those located in retail

store and gasoline station.

11 Without merit is the contention of the corporation that only

food delivered to it from out of state in the original package and

not foodstuffs processed or slaughtered in South Carolina should

be considered having moved in commerce. Such a restrictive notion

of the Commerce Clause was rejected in Katzenbach v. McClung,

379 U. S. 294, 302. See also Willis v. Pickrick, 231 P. Supp. 396,

399 (N. D. Ga. 1964). It should be noted that even the corpo

ration’s conception of movement in commerce results in 25 per

cent or 18 per cent of its purchase being so considered and such a

figure is also plainly “substantial.”

12 In Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U. S. 294, 296, 298, the restau

rant received 46% of its food from outside of Alabama and con

ceded coverage.

21

the status of persons driving automobiles with South Caro

lina license plates and thus indulging in the faulty assump

tion that one driving such a vehicle cannot be an interstate

traveler.13 Although the corporation continued to challenge

the Act at trial, the constitutionality of 42 U. S. C. §2000a-

(b)(2) is settled by Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U. S. 294.

Nor can the corporate President avoid the Civil Rights Act

because of his religious persuasion as the cases cited by the

district court show (209a). Negro appellants are, therefore,

entitled to an order enjoining racial discrimination at all

of the corporation’s restaurants.

II.

Negro Appellants Are Entitled to a Reasonable Attor

ney’s Fee.

In actions brought under Title II, the Civil Rights Act of

1964 provides that a prevailing party may be allowed a

reasonable attorney’s fee (42 U. S. C. §2000a-3):

(b) In any action commenced pursuant to this sub

chapter, the court, in its discretion, may allow the

prevailing party, other than the United States, a

reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the costs. . . .

Although the district court had “no trouble” enjoining racial

discrimination at one of the six restaurants, and taxed

13 It should be noted that 42 U. S. C. §2000a-(c) (2) does not

require proof that a “substantial” number of interstate travelers

are served. Unlike the immediately contiguous criterion relating

to movement of foods in commerce the clause “serves or offers to

serve” does not have a substantiality requirement. Such a require

ment was proposed in the House hut an amendment containing such

language was defeated, see supra, p. 14. See also Willis v.

Pickrick, 241 F. Supp. 396, 399 (N. D. Ga. 1964).

22

costs against the corporation, the court denied the prayer

of Negro appellants for a reasonable counsel fee. We be

lieve Negro appellants are entitled to fees under any rea

sonable construction of 42 U. S. C. §2000a-3(b).

Title II as a whole demonstrates a plain desire to insure

rapid and effective compliance with its terms and to deter

insubstantial and prolonged litigation.14 The counsel fee

provision of 42 U. S. C. §2000a-3(b) is part of a congres

sional scheme for deterring evasion and resistance to the

“full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities,

privileges, advantages and accommodations of any place of

public accommodation,” 42 U. S. C. §2000a-l. Although the

legislative record is scanty, such debate as relates to the

provision is consistent with an intent to induce compliance

by penalizing assertion of frivolous claims and to induce

attorneys to represent those with substantial claims. Sena

tor Ervin sought to eliminate the provision from the Act

on the ground that it would make those benefiting from it

special favorites of the law and would encourage “ambu

lance chasing.” 110 Cong. Rec. 14201, 14213-14 (June 17,

1964). Senator Pastore made a brief statement in defense

of the provision stating that its purpose was to deter frivo

lous suits but he clearly intended the provision to guard

against frivolous defenses also because he stated “ . . . the

court within its discretion is given power to order payment

14 Thus, 42 U. S. C. §2000a-3(a) permits intervention by the

Attorney General in privately initiated public accommodation suits,

appointment of counsel for a person aggrieved, and “the commence

ment of the civil action without the payment of fees, costs or

security.” 42 U. S. C. §2000a-5 authorizes the Attorney General

to commence litigation where there is “a pattern or practice of

resistance to the full enjoyment” of Title II rights. 42 U. S. C.

§2000a-2 broadly prohibits any attempt to punish, deprive, or

interfere with rights to equal public accommodations. See Georgia

v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780.

23

of attorneys’ fees to the prevailing party . . . It is not

favoritism towards one party as against the other,” 110

Cong. Ree. 14214 (June 17, 1964).15 Senator Miller opposed

the amendment on the ground that attorneys would be com

pensated only if they raised positions with merit:

. . . I believe that this is the answer to the Senator

from North Carolina, that if we are concerned about

ambulance chasing, we had better realize that the

ambulance.chasers are not about to be in the business

if there is no profit in it for them. They will be in the

business only if they can make a profit. They are not

going to make much profit out of any cases except those

which are meritorious, so I believe that the point is

exaggerated, and I believe the amendment is inad

visable (110 Cong. Rec. 14214 (June 17, 1964)).

In Twitty v. Vogue Theatre Cory., 242 F. Supp. 281, 288,

89 (M. D. Fla. 1965) the court applied such a construction.

It determined a reasonable fee to be $500.00 but taxed only

$100.00 as costs because the suit was the first under 42

15 Senator Pastore stated:

The purpose of this provision in the modified substitute is to

discourage frivolous suits. Here, the court within its discretion

is given power to order payment of attorneys’ fees to the pre

vailing party. First of all, it is within the discretion of the

court. It is not favoritism towards one party as against the

other. When a person realizes that he takes the chance of

having attorneys’ fees assessed against him if he does not

prevail, he will deliberate before he brings suit. He will make

certain that he is not on frivolous ground. (110 Cong. Rec.

14214 (June 17, 1964).)

Senator Pastore’s emphasis on frivolous suits is clearly explained

by the character of the challenges raised to the section by Senator

Ervin. The only construction of Senator Pastore’s remarks con

sistent with their context and the language employed in the statute

is that the provision was meant to penalize the assertion of frivolous

claims by either party.

24

U. S. C. §2000a-(b) (3) (motion picture houses, etc.); and

it arose at a time when a district court had declared other

portions of the Act unconstitutional as applied to its opera

tions. Other courts have apparently granted attorneys fees

as a matter of course. Franklin v. Peppers, 9 B.R. L. Kept.

1843,1845 (M. D. Fla. 1964).

Here there are no mitigating factors as those relied upon

by the court in Twitty, supra, in restricting counsel fees to

a token amount. The corporation has pursued various

claims that 42 U. S. C. §2000a-(c) (2) is unconstitutional

long after that question has been definitively resolved by

the United States Supreme Court in Katsenbach v. Mc-

Clung, 371 U. S. 291 (December 14, 1964). Indeed, it filed

a second amended answer raising such defenses March 30,

1966 after “carefully reviewing the pleadings heretofore

filed” (16a). The corporation also denied its activities

affect commerce forcing appellants to offer lengthy proof.

After trial, the district court, which excluded the drive-in

facilities as a matter of law, had no trouble determining

that the sandwich shop (and the drive-ins) were clearly

covered by the Act both because a substantial portion of

the corporation’s food moved in commerce and because it

failed to ascertain the travel status of its customers. It

should be noted that either circumstance would have satis

fied the “affect commerce” standard of the Act. Finally,

patently frivolous defenses were raised, such as denial of

racial discrimination and claim that serving Negroes inter

feres with a right to free exercise of religion.

Given the purpose of 42 U. S. C. §2000a-3(b) the only

ground on which the corporation might argue it was not

liable for attorney’s fees is that the district court found the

five drive-in restaurants not covered by the Act. This would

25

not, however, excuse the failure of the corporation to de

segregate the sandwich shop. Nor does it justify consistent

maintenance of unsupportable legal positions which un

necessarily complicate and prolong disposition of the ques

tions of law before the court. This resistance necessitated

a trial of a day and one-half, a long witness list, and ex

tensive preparation devoted primarily to establishing racial

discrimination, service of interstate travelers and substan

tial interstate food purchases (all matters ultimately estab

lished by overwhelming evidence). The refusal of the cor

poration to take initiative in complying with the law has

insured that the sandwich shop has had two extra years

of segregated operation despite a congressional determina

tion in 1964 that discrimination in public accommodations

was not in the public interest.

Negro appellants assert not only their own rights, hut

those of a class of persons whom restaurateurs are clearly

on notice they must serve except in extraordinary circum

stances. Counsel fees are necessary here not only in order

to protect individual rights but because of the class char

acter of racial discrimination and because of the serious

dislocation of trade and commerce, as found by Congress,

caused by such discrimination in public accommodations.16

In writing a comprehensive public accommodations title

into the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Congress plainly deter

16 The principle is demonstrated in a class of cases in which the

defendant is trustee of a common fund and as such hound by law

to protect the interests of the plaintiffs who are beneficiaries of

the fund. In such cases where the trust has been violated courts

do not hesitate to award attorneys fees to plaintiffs. Rolax v.

Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Co., 186 F. 2d 473 (4th Cir. 1951);

Guardian Trust Co. v. Kansas City Southern, 28 F. 2d 283 (8th

Cir. 1928); Sprague v. laconic National Bank, 307 U. S. 161

(1939). The public interest in full and equal enjoyment of public

facilities requires no less. See note 77 Harv. L. Rev. 1135 (1964).

26

mined to end once and for all such discriminatory prac

tices.17 Denial of attorneys fees here will encourage other

restaurants to continue evasive, dilatory, and obstructive

efforts to avoid the Act and gain a two year extension of

segregation. Thus the denial by the district court of a

reasonable attorney’s fee encourages further litigation.

In Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321 F. 2d

494, 500 (4th Cir. 1963) this Court set out criteria for

awarding counsel fees in the school desegregation cases.

They include (1) refusal to take any initiative to desegre

gate the schools; (2) interposing administrative obstacles

to thwart the valid wishes of plaintiffs for a desegregated

education; (3) long continued pattern of evasion and ob

struction. The Bell court concluded that the “equitable

remedy would be far from complete and justice would not

be obtained if counsel fees were not awarded in a case so

extreme.” There was, of course, in Bell no federal statute

evidencing a congressional intent for the prevailing party

to be awarded counsel fees. The action of Congress in

providing for counsel fees to the prevailing party in the

face of objections that such a provision was not usual in

our law makes award of counsel fees far stronger here but

appellants submit that this case meets even the Bell cri

teria. The corporation has refused to take any initiative

to desegregate a restaurant clearly covered by the Act over

two years after the enactment of a statute by Congress

designed to insure nondiscrimination. Despite the Supreme

Court’s definitive action in upholding the constitutionality

of the Act, the corporation has interposed a variety of

frivolous constitutional defenses. It has refused to narrow

the issues and put Negro appellants to an unnecessary

17 See supra, pp. 13-18.

27

task of developing proof. The corporation is doing just

what Congress sought to deter, calling for exercise of dis

cretion to award counsel fees.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, fo r the fo reg o in g reaso n s , ap p e llan ts p ra y

the ju d g m en t below be v aca ted and m odified.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

M ichael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

M atthew J . P erry

L incoln C. J e n k in s , J r .

H e m ph il l P. P ride, II

1107y2 Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

38