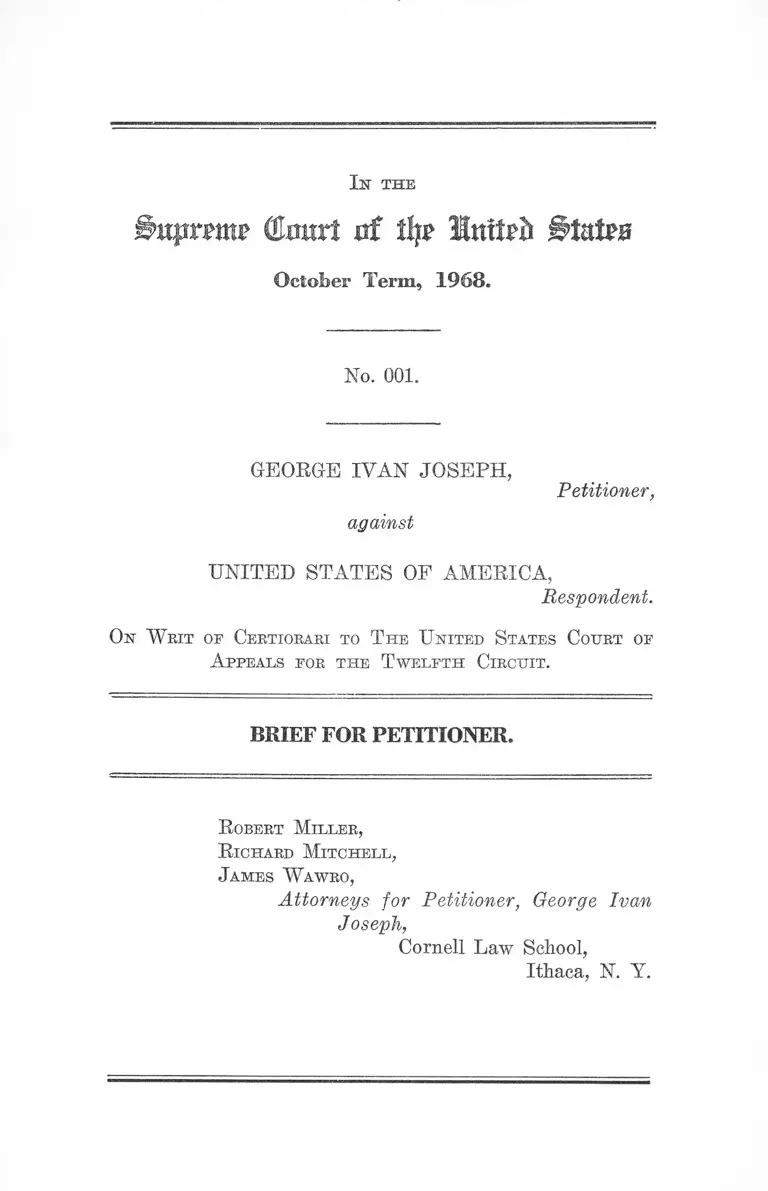

Joseph v. United States of America Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Joseph v. United States of America Brief for Petitioner, 1968. b8c4f284-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a489909e-93fe-45b9-8efb-bde79798dea2/joseph-v-united-states-of-america-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I k the

Bu$rm$ Glmxt iif % Ittttpft BUUb

October Term, 1968.

No. 001.

GEORGE IVAN JOSEPH,

against

Petitioner,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Respondent.

Ok W rit of Certiorari to T h e U nited S tates C ourt of

A ppeals for t h e T w e l f t h C ir c u it .

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER.

R obert M ill e r ,

R ichard M it c h e l l ,

J am es W awro,

Attorneys for Petitioner, George Ivan

J oseph,

Cornell Law School,

Ithaca, N. Y.

Table of Contents.

Page

Preliminary Statement ........... ............................... ..... 1

Questions Presented ...................................... ............. 2

Constitutional Provisions and Treaties Involved ....... 3

Statement of Facts ...................................................... 3

Summary of Argument ......... ...... ................ ........... . 4

Argument .................... ..... .......................................... 5

I. Under the modern approach to the “Political Ques

tion” doctrine this court has both the power

and the responsibility to adjudicate the issue

of petitioner being ordered to participate in

an undeclared war in Vietnam which violates

the Constitution of the United States, its

treaty obligations, and international law ...... 5

II. The deprivation of the petitioner’s Fifth Amend

ment rights gives this court jurisdiction over

the subject matter of his action challenging

the constitutionality of the war. This depriva

tion of his legal rights coupled with his ob

vious adverse interest to the President’s con

duct of the war gives petitioner standing to

sue 11

11.

Page

III. Executive action in committing our military

forces to a war of the scope and size of that

in Vietnam is an unconstitutional usurpation

of the power of Congress to declare war ...... 14

A. Neither by its actions nor by its words has

Congress exercised its sole prerogative to com

mit the nation’s armed forces to a war such

is being conducted in Vietnam _______ ______ 14

B. The President’s power as Commander-in-

Chief is not sufficient constitutional authori

zation for engaging five-hundred thousand

troops in an extended foreign war without the

required Congressional authorization .............. 19

IV. The unilateral action of the United States in

Vietnam violates the duties and obligations

this country has assumed as a member of the

United Nations and directly conflicts with the

clear provisions of the SEATO treaty _____ 22

A. The present war was entered into in direct

contravention of Article 33 (1) of the United

Nations charter in that it disrupted a “peace

ful solution” previously reached at the Geneva

Conference of 1954 ........... ..... ...................... 23

B. The charter’s exceptional authorization of col

lective and individual self-defense is unavail

able as a justification for United States inter

vention in Vietnam ........ ............... .................. 24

C. The United States has violated the explicit

directives of the SEATO treaty under which

it purports to justify its unilateral interven

tion ............... ................................................ ...... . 26

Page

iii.

V. The United States, as a member of the United

Nations and of the civilized world community,

is bound by international law to refrain from

disturbing efforts among other nations and

peoples to peacefully settle their differences .... 29

A. The war in Vietnam is a civil war and no

right of intervention on the part of the United

States exists on behalf of one or the other of

the factions involved therein ______ _____ ~ 30

B. United States participation is a direct sabo

tage of the Geneva Accords, which were ar

rived at in accordance with the “peaceful set

tlement” provisions of Article 31 of the United

Nations charter ________________________ 32

Conclusion ________________________________—. 36

Appendix A _______________ ____ ________ __— 39

Appendix B _________________________ ______ 46

IV .

CITATIONS

Cases:

Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186 (1962) -------- 6, 8, 11, 12, 13

Bas. v. Tingey, 4 Dali. 37 (1800) ....... ...........-......----- 10

Braxton County Court v. West Virginia, 208 U. S.

192 (1903) .................. - - .........-......- - ......-.... 12

The Brig Amy Warwick, 2 Black 635 (1863) ........... 21

Carrol v. Becker, 285 II. S. 380 (1932) .................—- 8

Colegrove v. Green, 383 U. S. 549 (1946) .................. 9

Coleman v. Miller, 307 U. S. 433 (1939) ................ -.... 7, 8

Cook v. United States, 288 IT. S. 102 (1933) .............. 29

Ex Parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 (1944) ....... ................. 18

Federal Communications Commission v. Sanders,

309 U. S. 470 (1940) ____________________ 13

Flast v. Cohen, 393 U. S. 83 (1968) _____ ___ ___ 12, 13

Greene v. McElroy, 360 IJ. S. 474 (1959) ...... ........... 18

The Habana, 175 U. S. 677 (1900) ....... ................. 11, 29

Hearne v. Smylle, 378 U. S. 563 (1964) ................. 12

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81 (1943) .... 10

Joint Anti-Fascist Befugee Committee v. McGrath,

341 U. S. 123 (1951) ............ .............. ............ 13

Koenig v. Flynn, 285 U. S. 375 (1932) .................... . 8

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214 (1944) .... 10

Page

V.

Page

Levine v. O’Connell, 275 App. Div. 217, 88 N. Y. S.

2d 672 (1949), aff’d 300 N. Y. 658 (1950) ...... 15

Luftig v. McNamara, 373 F. 2d 664 (D. C. Cir. 1967),

cert, denied sub nom. Mora v. McNamara, 389

U. S. 934 (1967) ............................ -................. 36

Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803) ............- 6

Muskrat v. United States, 219 U. S. 346 (1911) ...... 12

O’Neal v. United States, 140 F. 2d 908 (6th Cir.

1944), cert, denied 322 U. S. 729 (1944) .......... 22

Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan, 293 0. S. 388 (1935) 15

Perkins v. Leukins Steel Co., 310 U. S. 113 (1940) .... 13

Prize Cases, 2 Black 635 (1863) ....... ............... ......... 10,11

Reid v. Covert, 354 U. S. 1 (1.957) ....... ..................... 26

San Lorenzo Title and Improvement Company v.

Caples, 48 S. W. 2d 329 (Texas, 1932) _____ 23

Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 259 U. S.

495 (1935) ................................................... - 15

Scholle v. Hare, 359 U. S. 429 (1962) ______ ____ 12

Smiley v. Holm, 285 U. S. 355 (1932) ........ ................. 8

United States v. Macintosh, 283 U. S. 605 (1931) — 29

United States v. Minnesota, 270 U. S. 181 (1926) .... 26

United States v. Robel, 389 U. S. 258 (1967) ........... 15

Westberry v. Sanders, 376 IT. S. 1 (1964) ................. 8, 9

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U. S.

479 (1952) ...... .......... .................................... 19, 20

V I.

Constitution:

United States Constitution

Article I, Section 4, Clause 1 ........... ................ 9, 39

Article I, Section 8, Clause 11 ..... ........... 14, 27, 39

Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 ___ ____ ____ 19, 39

Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 ................. ........... 27

Article VI, Clause 2 ................................... . 22, 24, 39

Amendment V ........................................... ........... 39

Resolutions:

Page

Affirmation of the Principles of International Law

Recognized by the Charter and Judgment of

the Nuremberg Tribunal, G. A. Res. 95 (I),

9 U. N. Gaor, at 188 U. N. Doc. A/64/Add.

1 (1947) ............ ......................................

Southeast Asia Joint Resolution (Gulf of Tonkin

Resolution), Aug. 10, 1964, 78 Stat. 384 .. 14, 15, 18,

28, 44

Statutes:

28 U. S. C. 1331(a)

28 U. S. C. 2201 ......

12

12

Treaties and International Documents:

Geneva Conference on the Problem of Restoring

Peace in Indo-China, (Geneva Accords of

1954) July 21, 1954, Great Britain Misc. #20

(1954) (Cmd. 9239); reproduced in 60 A. J.

I. L. 629 (1966) ............. 18, 23, 24, 25, 30, 31, 32,

33, 34, 35, 40

V ll .

Page

Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty

(SEATO), Sept. 8, 1954 (1955), 6 XT. S. T. 81,

T. I. A. S. 3170; 209 U. S. T. S. 28 .... 22, 26, 27,

28, 42

United Nations Charter, June 26, 1945, 59 Stat. 1031

(1945); T. S. No. 993

Article 33 (1) ___ _____ ___________23, 24, 32, 43

Article 51.............................. ............... . 24, 25, 43

United States Declaration on Indo-China, 31 Depart

ment of State Bulletin 162 (1954) .............. 34, 41

Miscellaneous:

Congressional Record, vol, 112 (1964) .......... . 16, 17, 18

Department of State, Office of the Legal Adviser,

The Legality of the United States Participa

tion in the Defense of Vietnam, 60 A. J. I. L.

565 (1966) ..................18, 19, 20, 21, 24, 25, 26, 30, 33

Falk, Vietnam Critique, 75 Tale L. J. 1134 (1966) .... 31

Pall, Vietnam Witness: 1953-1966 (1966) ...... ....... 25, 31

Fourth Interim Report of the International Control

Commission, Vietnam No. 3, Cmd. No. 9654

(1955) __________________ ____ _____ ___ 33, 34

Hackworth, Digest of International Law (1943) ___ 28

Hyde, International Law (2nd ed. 1947) ............... . 36

LaCoutre, The Two Vietnams (1966) ................. 25, 30

Majority Leader Mansfield, Report to the Senate,

90th Cong. 1st Sess. (1967) ............................. 26

McDougal and Associates, Studies in World Public

Order (1960) 32

V l l l .

Page

Oppenheim, International Law (7th ed., Lauterpacht,

1955) ............ ...................................................... 36

Padelford, International Law and Diplomancy in The

Spanish Civil War (1939) ____ ____________ 31

Undersecretary of State Katzenbach, Hearings be

fore the Committee on Foreign Relations of

the United States Senate, 90th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1967) ................................ ............. ....... . 20

I n t h e

( to r t of ilio HUnxUb Btixtis

O ctober T erm , 1968.

No. .001

George I van J oseph

Petitioner,

v.

U n ited S tates of A merica .

Respondent.

O n W rit of Certiorari to t h e U nited S tates C ircuit

C ourt of A ppeals for t h e T w e l ft h C ir c u it .

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER.

Preliminary Statement.

The petitioner in this action is a private in the United

States Army seeking an injunction against the United

States forbidding the Secretaries of Defense and of the

Army from ordering him to serve in Vietnam (R. 6, 7),

and a declaratory judgment that United States military

involvement in Vietnam is unconstitutional and violative

of various treaties to which the United States is a party,

(R. 7). The United States Government has consented to

be sued in this action, (R. 8).

The United States District Court of the Middle Dis

trict of Bliss dismissed the complaint for failure to state

a cause of action on the ground that the issues were

political in nature and could not be heard by the court.

2

(E. 4). The Court of Appeals for the Twelfth Circuit

affirmed the dismissal (R. 12) and the Supreme Court

granted certiorari. (R. 13).

Questions Presented.

1. Whether, in light of the modern developments in

volving the “political question” doctrine, this court may

properly adjudicate issues relating to executive usurpation

of Congressional power to declare war, and violations

of treaties and international law. (see infra, pages 5 to

11) .

2. Whether forcing petitioner to participate in a war

which is both unconstitutional and violative of interna

tional law is such an abridgement of his Fifth Amend

ment Due Process Rights as to constitute an “immediate

legal injury,” thereby giving him “standing” to bring

this suit? (see infra, pages 11 to 13).

3. Whether the large-scale continuing committment to

combat of United States’ armed forces in Yietnam with

out congressional authorization or declaration of war

violates Article I, Section 8, of the United States Con

stitution, which gives Congress and Congress alone the

power to declare war. (see infra, pages 14 to 22).

4. Whether the unilateral intervention by the United

States in an internal war between the two sections of

Vietnam is in violation of our obligations under the

United Nations Charter, and of our duties as a signatory

of the SEATO treaty, (see infra, pages 22 to 29).

5. Whether the United States’ committment of armed

forces to the conflict in Vietnam is in violation of inter

national law as a disruption of the previous “negotiated

settlement” effected by the Geneva Conference of 1954.

(see infra, pages 29 to 36).

3

Constitutional Provisions and Treaties Involved.

United States Constitution:

Article I, Section 4, Clause 1

Article I, Section 8, Clause 11

Article II, Section 2, Clause 1

Article VI, Clause 2

Amendment V

Treaties:

Charter of the United Nations, June 26, 1945, 59 Stat.

1031 (1945); T.S. No. 93

Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, (SEATO)

Sept. 8, 1954 (1955), 6 U.S.T. 81; T.I.A.S., No. 3170; 209

U.S.T.S. 28

(The pertinent texts of these provisions are set forth in

full in the appendix, and where applicable in the argu

ment).

Statement of Facts.

The petitioner, George Ivan Joseph, registered for the

draft in February, 1962, when he reached eighteen years

of age. (R. 1, 9). The local draft board classified the peti

tioner 2-S (deferred) and continued to classify him 2-S

for the next four years while he was in college. (R. 1, 9).

Upon his graduation from college in 1966, petitioner’s

local board reclassified him 1-A (available for military

service). (R. 1, 9). Joseph objected to the classifica

tion on the ground that he was a conscientious objector

to the Vietnam war in particular; but after a hearing in

November, 1966, the local board denied petitioner con

scientious objector status because he was not opposed to

“war in any form” within the meaning of Section 456 (J)

of the Uniform Military Training and Service Act. (R.

4

1, 2, 9, 10). Appeal from the Board’s decision was de

nied and petitioner was drafted on June 20, 1967. (R. 2,

10). He duly reported for induction, and went into the

army (R. 2). Petitioner did not then nor does he now

seek to escape from military service. (R. 2). He simply

seeks to aviod participation in what he claims to be an

illegal war. (R. 3, 5). Judge Phaire, in the District

Court opinion beloAv noted that “few young men with

his belief have attempted so scrupulously to abide by

laws and regulations.” (R. 2).

Upon completion of basic training and advanced in

fantry training at Fort Dunning, Bliss, the petitioner

was assigned to a unit scheduled to be sent to Vietnam.

(R. 2). At that time, petitioner requested through the

proper military channels that he be assigned to another

unit since he was conscientiously opposed to the Viet

nam war (R. 2, 5, 6, 10). The request was denied and

review thereof finally denied by the Secretary of the

Army (R. 2). On December 4, 1967, petitioner was or

dered to report to his assigned unit, but he refused to do

so and was ordered confined to the post pending court-

martial proceedings (R. 2). A general court-martial

was convened, but hearings were postponed until twenty

days after the final determination of this action (R. 2, 6,

7, 10).

Summary of Argument.

The petitioner is alleging that he has been ordered to

fight in an undeclared and therefore unconstitutional

war which is in violation of United States treaty obliga

tions and international law. We contend that the courts

below erred in characterizing the subject matter of this

suit as political in nature. In light of the Supreme

Court’s continued erosion of the “political question” doc

trine, and in light of the great magnitude of the issues

5

involved, it is our position that petitioner should be

granted a realistic day in this court by having it hear

the merits of his claim. Certainly it cannot be argued

that petitioner lacks standing to sue for lack of an ad

verse personal interest or legal injury if the respondent

persists in its order that he be shipped to Vietnam.

On the merits, the petitioner contends that the Vietnam

war is unconstitutional because the executive has single-

handedly committed our forces to the conflict without

Congressional authorization or declaration of war. In

addition, the unilateral American intervention in Vietnam

is unconstitutional because it is in direct violation of

treaties to which the United States is a party, and of

prevailing doctrines of international law. Because the

war in Vietnam is unconstitutional, the Due Process

Clause of the Fifth Amendment precludes the United

States from ordering petitioner to participate in it.

ARGUMENT.

I.

Under the modern approach to the “Political Ques

tion” doctrine this court has both the power and the re

sponsibility to adjudicate the issue of petitioner being

ordered to participate in an undeclared war in Vietnam

which violates the Constitution of the United States,

its treaty obligations, and international law.

We anticipate that if this court reaches the merits of

this controversey it will find that the Vietnam wTar is

an unconstitutional executive usurpation of Congressional

power. The crucial question, therefore, is whether, as

suming the war to be unconstitutional, this court can

or should so adjudicate it over the “political question”

6

objection raised by the government. Petitioner suggests

that an affirmative answer is compelled under a full

consideration of the current judicial definition of a

“political question”. It is our position that, in light of

the demonstrated inability or unwillingness of Congress to

act during our involvement in this war, this court is the

only branch of the government which can and must now

intervene to prevent a continuous violation of the United

States Constitution.

Historically, the power of the court to delineate the

authority of the various branches of government has

been a major part of the court’s role in the constitutional

scheme. As Chief Justice Marshall said in Marbury

v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803), at 177-178:

It is, emphatically, the province and duty of the

judicial department, to say what the law is. Those

who apply the rule to particular cases, must of

necessity expound and interpret that rule. If

two laws conflict with each other, the courts must

decide on the operation of each. So, if a law be in

opposition to the constitution; if both the law

and the constitution apply to the particular case,

so that the court must either decide that case, con

formable to the law, disregarding the constitution;

or conformable to the constitution disregarding the

law; the court must determine which of these con

flicting rules governs the case; this is of the

very essence of judicial duty.

Recently, in Baber v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), at 211,

the court said:

Deciding whether a matter has in any measure been

committed by the Constitution to another branch

of government, or whether the action of that

branch exceeds whatever authority has been com

mitted . . . is a responsibility of this court as

ultimate interpreter of the Constitution.

7

Thus, from its inception, to the very recent past, this

court has consistently held that it has the power to

determine which branch of the federal government has

the constitutional authority to make particular decisions.

The Supreme Court has also held, however, that certain

cases otherwise properly presented before it would not

be decided by the court because these cases presented

issues which should more properly be decided by other

branches of the government. The “political question”

doctrine, which the government seeks to invoke here does

not apply to the case at bar.

The test for what constitutes a “political question” has

evolved considerably in recent years. In Coleman v.

Miller, 307 U.S. 433 (1939), the court declined to hear

the merits of a case on the grounds that it presented

a political question, saying, at 454:

In determining whether a question falls within that

category, the appropriateness under our system

of government of attributing finality to the action

of the political departments and also the lack

of satisfactory criteria for a judicial determination

are dominant considerations.

This test indicates that the court will not decide a ease

where there is a lack of satisfactory criteria for a judicial

determination. In the case at bar, the petitioner is

asking the court to declare the war in Vietnam uncon

stitutional and violative of treaties and international

law. The legal criteria necessary for such a determina

tion can be found in the plain language of the Constitution

and the treaties to which the United States is a signatory.

In Coleman v. Miller, supra, there was no constitutional,

provision for the court to interpret in deciding whether

a state legislature could ratify a Constitutional amend

ment after once having rejected it. The Coleman case

was a proper case for the court to invoke the “political

question” doctrine because there was no authority what

soever applicable to the issues. But here, there is abund

ant constitutional and treaty authority for the court to

apply. Therefore, the case at bar satisfies the test of

sufficient legal criteria to determine the issues.

As the “political question” doctrine was invoked in

cases subsequent to Coleman v. Miller, 307 U.S. 433

(1939), a new test began to evolve for “political ques

tions.” In Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), the court

defined “political questions” by saying, at 211:

The nonjusticiability of a political question is

primarily a function of the separation of powers

. . . Deciding whether a matter has in any measure

been committed by the Constitution to another

branch of government . . . is a responsibility of

this court as the ultimate interpreter of the Con

stitution.

Thus, the emphasis of the “political question” doctrine

had shifted in Baker v. Carr, supra, from the lack of

judicial criteria to the principle of separation of powers.

The government argues in this case that the Vietnam

war is a “political question” since the decision to con

duct it is within the province of the executive department

of the government. Their argument is that, once the

Executive has made a decision to commit the nation to

war, the court cannot review that decision.

However, since the decision of this court in Wesberry v.

Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964), the argument can no longer

be maintained that a decision, even if made by the de

partments of government charged in the Constitution with

making the decision, is not reviewable by the Supreme

Court. See also: Carrol v. Becker, 285 U.S. 380 (1932);

Koenig v. Flynn, 285 U.S. 375 (1932); Smiley v. Holm,

285 U.S. 355 (1932). Article I, Section 4, Clause 1, of

the Constitution provides:

9

The Times, Places, and Manner of holding Elections

for Senators and Representatives shall be pre

scribed in each State by the Legislature thereof;

but the Congress may at any time by Law make

or alter such Regulations, except as to the places

of choosing Senators.

Clearly, the Constitution charges the States with the

duty of providing for the election of Congressmen and

provides that Congress shall be the forum for change if

the States have not faithfully discharged this duty. How

ever, the court in Wesberry, supra, changed a state’s

reapportionment rule and ordered “one man, one vote”

to be the rule in selecting Representatives. The court

itself changed the rule, eAmn though a co-ordinate branch

of the government was specifically charged with this

duty, and in spite of a decision squarely holding that

reapportionment was a “political question” solely within

the province of Congress. Colegrove v. Green, 328 TJ.S.

549 (1946). After the court’s Wesberry decision it

can hardly be said that the court cannot hear cases

involving decisions made by co-ordinate branches of gov

ernment. The political question test does not preclude

the court from hearing the present case merely on the

grounds that a co-ordinate branch of government, the

Executive, has found the war to be consonant with the

Constitution.

The impact of these decisions is obvious. The issues

presented in this case do not fall within the classic tests

for invoking the “political question” doctrine. In ad

dition, these tests have been eroded to the point where

the doctrine is one primarily of “judicial restraint”. This

court in Wesberry v. Sanders, supra, had exercised re

straint for over sixty years from the time the fact of

illegal apportionment was first presented, before the

court corrected the situation. The court finally deter

mined that it could wait no longer for Congress to act,

and stepped in itself to right this clear constitutional

10

wrong. In the case at bar, Congress has failed to rec

tify an unconstitutional situation existing since at least

1964. Since the issues presented here are those of the

very lives of thousands of servicemen in Vietnam and

the petitioner in particular, this court should abandon its

restraint and afford petitioner a forum to rectify this

unconstitutional deprivation of his Fifth Amendment

rights. There is no reason, in light of the magnitude of

the issues involved, for petitioner to be forced to wait

longer to air his constitutionally justified grievances.

The traditional tests and the court’s more recent treat

ments of “political questions” do not preclude the court

from hearing this ease. In addition, the court should

hear the merits of the petitioner’s claim. Surely, if

some future President were, on his own, to embark

upon world conquest, unconstitutionally committing our

troops to world war, this court would not retreat from

the merits of the controversy. The magnitude of the

issues and the clear illegality of the President’s action

would require this court to adjudicate the case. In

fact, a far less clearly illegal executive action has, in

the past, prompted this court to rule on the constitution

ality of our going to war. When Confederate forces

fired on Fort Sumter in 1861, President Lincoln declared

a naval blockade of all Southern ports. Privateers seized

ships pursuant to the blockade and the ownership of

these vessels was litigated in the Prize Cases, 2 Black

635 (1863). The issue there was whether a state of

war legally existed when the President declared the

blockade. The Supreme Court did not dismiss the suit

because it presented a “political question,” but rather

passed upon the merits in the action, holding, inter alia,

that Congress had specifically ratified the acts of the

President. See also: Bas v. Tingey, 4 Dali. 37 (1800);

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943); Kore-

matsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944); The Paquette

11

Habana, 175 U.S. 677 (1900). The Prize Cases, supra,

are clear precedent for the proposition that the court

faces no political question when the issue in a case

is which branch of the federal government has the ultimate

power to commit the nation to war—the precise issue

raised in the case at bar.

The conclusion from this investigation of the “political

question” doctrine is that the petitioner’s case can and

should be decided on its merits. This court is the

ultimate interpreter of the Constitution and should dis

charge that function unless a case otherwise properly

presented before the court involves a “political question.”

Under the traditional tests and recent judicial definitions

of “political questions,” no such question is presented

in this ease. Finally, in the Prize Cases, supra, the court

lias passed upon the precise issues raised in this case.

Therefore, the court has the constitutional power and

duty to pass on the merits here presented.

II.

The deprivation of the petitioner’s Fifth Amendment

rights gives this court jurisdiction over the subject

matter of his action challenging the constitutionality

of the war. This deprivation of his legal rights

coupled with his obvious adverse interest to the

President’s conduct of the war gives petitioner standing

to sue.

In Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), this court

exhaustively dealt with the requirements necessary for

subject matter jurisdiction. The court said that a suit

would be dismissed for lack of subject matter jurisdiction

only if it did not:

12

arise under the Federal Constitution, laws or

treaties . . . or is not a “case or controversy”

within the meaning of that section; or the cause

is not one described by any jurisdictional statute.

369 U.S. at 199

See also: Hearne v. Smylle, 378 U.S. 563 (1964); Scholle

v. Hare, 369 U.S. 429 (1962).

In the present case, the cause arises under the Federal

Constitution because the petitioner is claiming that by

sending him to Vietnam the Secretaries of the Army

and Defense are depriving him of life and liberty with

out due process of law in contravention of the Fifth

Amendment. The present suit is a “ease or controversy”

within the meaning of Article III, Section 2, Clause 1, of

the Constitution because the petitioner is presenting a

real controversy rather than a friendly suit, Muskrat v.

United States, 219 U.S. 346 (1911); the petitioner is

“interested in, and adversely affected by, the decision”

of which he seeks review, Braxton County Court v.

West Virginia, 208 U.S. 192, 197 (1903); the petitioner’s

interest is “of a personal, and not of an official, nature”,

Braxton, supra, at 197; and the petitioner’s interest is

substantial, with a “logical nexus between the status

asserted and the claim sought to be adjudicated”, Blast

v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83, 102 (1968). Finally, the case

is one described by 28 U.S.C. Sections 1331 (a) and

2201. Therefore, since the petitioner’s case clearly meets

all of the requirements for subject matter jurisdiction

set forth in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), the court

may exercise jurisdiction.

The test for the standing of a plaintiff to sue is also

set forth in Baker v. Carr, supra, at 204:

Have the appellants alleged such a personal stake

in the outcome of the controversy as to assure

that concrete adverseness which sharpens the pres

entation of issues upon which the court so largely

13

depends for illumination of difficult constitutional

issues? This is the gist of the question of stand

ing.

This court has held that the requisite adverse personal

interest may consist of nothing more than mere economic

competition. Federal Communications Commission v.

Sanders, 309 U.S. 470 (1940). Since the petitioner in

this case will be sent to armed combat in Vietnam unless

this court directs otherwise, the petitioner has the req

uisite adverse personal interest necessary to maintain

this suit.

In addition to a personal stake in the outcome of the

controversy, this court has held that the petitioner

must have a “legal right” upon which to base his

claim. Perkins v. Leukins Steel Co., 310 U.S. 113 (1940).

Such a legal right to be free from the alleged injury can

be based on the common law, Perkins v. Leukins Steel Co.,

supra; a statute, Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962); or

the Constitution, Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee

v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123 (1951). The plaintiff is here

alleging that ordering him to participate in an uncon

stitutional war violates his Fifth. Amendment Due Process

rights. Hence, the petitioner’s “legal right” is a con

stitutional right and is sufficient to sustain his claim.

See Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83 (1968).

Therefore, since the petitioner has both an adverse

personal interest and a “legal right” based upon the

Constitution, he has standing to sue in this action.

14

III.

Executive action in committing our military forces

to a war of the scope and size of that in Vietnam is

an unconstitutional usurpation of the power of Con

gress to declare war.

The Constitution specifically relegates the power to

declare war to the legislative branch. Article I, Section

8, Clause 11, United States Constitution, states:

“The Congress shall have Power . . . (11) to declare

War . . . ” By conducting continuous large-scale military

operations in Vietnam, the executive branch is acting

beyond the Constitution and has usurped Congress’ power

to declare war. Clearly, the Framers of the Constitution

intended that such power not be lodged in one man. The

petitioner does not deny that some war powers are lodged

in the President. However, the petitioner contends that

a conflict of the magnitude of Vietnam is not within

those powers but is a war which only Congress may

constitutionally commit ns to. Starting with the premise

that only Congress can declare war, it is our position that

the narrow Presidential war powers do not authorize

him to conduct the present level of armed combat.

A. N either by its actions nor by its words has Congress

exercised its so le prerogative to com m it the n ation’s

arm ed forces to a war such as is b eing conducted in

the instant case.

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, 78 Stat. 384 (1964), is

not the equivalent of a congressional declaration of war,

nor does it authorize the present conduct of the Executive

in Vietnam. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, supra,

provides in pertinent p a rt:

15

. . . the Congress approves and supports the de

termination of the President as Commander-in-

Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel

any armed attack against the forces of the United

States and to prevent further aggression. . . .

Consonant with the Constitution of the United

States and the Charter of the United Nations

and in accordance with its obligations under the

Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, the

United States is, therefore, prepared as the Presi

dent determines, to take all necessary steps, in

cluding the use of armed force, to assist any mem

ber or protocol state of the Southeast Asia Col

lective Defense Treaty requesting assistance in

defense of its freedom.

By its very terms, the Resolution refutes the notion

that it is a declaration of an unlimited war. In Section

1, it speaks to the problem of attacks on United States

destroyers and authorizes the President to repel these

attacks and to prevent their future occurrence. Section

2 authorizes the use of armed force to aid South Vietnam,

but only if that aid is “consonant with the Constitution.”

The Resolution is not, by its terms, a declaration of

war and does not delegate to the President all of Con

gress’ power to declare war, since such a delegation would

be patently unconstitutional and not therefore “con

sonant with the constitution.” Panama Refining Co. v.

Ryan, 293 U.S. 388 (1935); Schechter Poultry Corp. v.

United States, 295 U.S. 495 (1935); United States v.

Robel, 389 U.S. 258, 275 (1967). If Congress has delegated

away part of its Avar poAAmrs in the Gulf of Tonkin Resolu

tion, supra, it is essential to examine the legislative his

tone surrounding its passage to determine A\rhat limits

Congress intended to set on its delegation to the Presi

dent. Levine v. O’Connell, 275 App. Drv. 217, 88 N.Y.S.

2d 672 (1949), aff’d. 300 N.Y. 658 (1950).

The President’s initial message to Congress in support

of the Resolution said:

16

“As I have repeatedly made clear the United

States intends no rashness and seeks no wider war.”

112 Cong. Rec. 18132 (1964).*

Senator Fullbright, who was instrumental in sponsoring

the Resolution in the Senate and who has subsequently

become the war’s harshest Senate critic, continually de

clared in answer to questions that the Resolution did

not contemplate any expansion of the war. For example,

in response to a question by Senator Brewster about “the

landing of large American armies in Vietnam or China,”

112 Cong. Rec. 18403, Senator Fullbright responded,

“There is nothing in the resolution, as I read it, that

contemplates it. I agree with the Senator that that

is the last thing we would want to do.” 112 Cong. Rec.

18403. Later in the debate, Senator Fullbright, in speak

ing for the Foreign Relations Committee, stated that

everyone he had heard agreed that the United States

must not become involved in an Asian land war and

that the purpose of the Resolution was to deter the

North Vietnamese from spreading the war. The Senator

admitted that the language of the Resolution would not

prevent the President from escalating the war, but he

Indicated that this was not the intent of Congress. 112

Cong. Rec. 18403. Senator Morton stressed the fact that

the purpose of the Resolution was to prevent the United

States from landing vast armies on the Asian continent.

112 Cong. Rec. 18404. Senator Nelson stated that the

Resolution was not to authorize a direct land confronta

tion by the American Army in Vietnam. 112 Cong.

Rec. 18407. Senator Stennis said that the intent of the

Resolution was to avoid full-scale war. 112 Cong. Rec.

18415. Senator Church emphasized that the policy of the

United States was not to expand the war. 112 Cong,

Rec. 18415. Senator Randolph stated that the course of

•Date hereinafter omitted.

17

action authorized by the resolution did not involve the

danger of unlimited hostile activity. 112 Cong. Rec.

18419.

Senator Nelson even offered an amendment to the

Resolution in the course of the debates on it. 112 Cong.

Rec. 18459. The purpose of the amendment was to

make it even more clear that the mission in South Vietnam

was to be confined to assistance and advice to the South

Vietnamese. Senator Fullbright said that the amend

ment accurately reflected the thinking of the President,

the Senators, and the Foreign Relations Committee; and

he rejected the amendment on the sole ground that its

inclusion would delay the Joint Resolution since the

PXouse had already passed the version before the Senate.

The debate over the Resolution in the House of Repre

sentatives is an even clearer indication of what was in

tended by the Resolution. Congressman Morgan stated

that the Resolution was “definitely not an advance decla

ration of war. The Committee has been assured by the

Secretary of State that the Constitutional power of

Congress in this respect will continue to be scrupulously

observed.” 112 Cong. Rec. 18539. Congressman Adair

said that Congress was not abdicating its power to

declare war, that it was the attitude of the Executive

that the Resolution was not an advance approval of any

action the Executive may see fit to take in the future.

112 Cong. Rec. 18543. Congressmen Gross and Fascell

stated that the Resolution was not a declaration of war.

112 Cong. Rec. 18549, 19576.

The Congressional intent that emerges from the debate

on the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution indicates that the

Senators and Representatives voting for the Resolution

felt that it wras not a declaration of war and that it

did not authorize escalation of the hostilities. In light

of these statements of intent by Congress, it is clear

18

that the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution does not authorize

the present activities of the Executive in Vietnam.

In support of the contention that Congress has rati

fied the President’s action by the Gulf of Tonkin Resolu

tion, supra, the argument has also been made that Con

gress ratifies the actions of the President by appropriat

ing money to support the military in Vietnam. Depart

ment of State, Office of the Legal Advisor, “The Legality

of the United States Participation in the Defense of

Vietnam,” 60 A.J.I.L. 565 (1966).2 This boot-strap argu

ment cannot support the Executive’s action in Vietnam.

Regardless of whether a Congressman agrees or disagrees

with the overall action of the President, he cannot deny

weapons and food to American soldiers fighting in a

foreign war, even if they are fighting there as a direct

result of Executive usurpation of Congress’ power to de

clare war. A vote for an appropriation bill can in no

sense be deemed a ratification of the executive action in

Vietnam. If voting for appropriation bills gives the

President ratification for his acts, then the President has

unlimited power to declare war. All that a President

need do to declare such a war is to commit troops to

a war and then ask for appropriations to prevent their

annihilation. In fact, this court has specifically held, in

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 (1959), that where execu

tive action is of dubious constitutionality it is not sufficient

to argue that Congress has impliedly ratified the action by

appropriating money. See also: Ex Parte Endo, 323 U.S.

283 (1944). As the court made clear at 360 U.S. 507,

explicit ratification is necessary to insure:

careful and purposeful consideration by those re

sponsible for enacting and implementing our laws.

Without explicit action by the lawrmakers, decisions

of great constitutional import would be relegated

hereinafter cited as State Department Brief, with page ref

erences being to 60 A. J. I. L. (1966).

19

by default to administrators who, under our system

of government, are not endowed with authority to

decide them.

Respondents can point to no congressional actions which

satisfy this clear requirement of congressional ratification.

B. T he P resident’s pow er as Com m ander-in-Chief is not

sufficient constitutional authorization fo r engaging

five hundred thousand troops in an extended foreign

war w ithout the required C ongressional authorization.

The executive has argued that the President, as Com

mander-in-Chief, United States Constitution, Art. II, See.

2, clause 1, can carry on large-scale warfare. State De

partment Brief, 579. This argument not only makes the

military supreme over the civilian authorities (i. e.,

Congress) in the matter of declaring war, but also author

izes the President to usurp the legislative power of

Congress. During the Korean War, President Truman,

under the same rationale as the government would have

the court accept in this case, seized the steel mills, stating

that his power as Commander-in-Chief authorized him

to insure the uninterrupted production of steel for that

war. But this court refuted his contention in Youngstown

Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 IT.S. 579 (1953), say

ing, at 587,

we cannot with faithfulness to our constitutional

system hold that the commander-in-chief of the

armed forces has the ultimate power as such to

take possession of private property. . . . This is

a job for the nation’s law-makers, not for its

military authorities.

Despite the holding of Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co.

v. Sawyer, supra, the government contends that the past

history of executive deployment of American armed forces

under his commander-in-chief powers supports the con

20

tention that he may fight a large-scale undeclared war.

State Department Brief, 584. On some 125 occasions

in the past the President has deployed American troops

without a congressional declaration of war. State De

partment Brief, 584. With the exception of the Korean

War, these instances do not provide precedent for stating

that the President has the power to fight a large-scale

undeclared war. Under Secretary of State Katzenbach

calls these precedents “relatively minor uses of force.”

Hearings Before the Committee on Foreign Relations of

the United States Senate, 90th Cong. 1st Sess. 81 (1967).

Such minor uses of force cannot serve as precedent for

the extensive military operations in Vietnam.

Nor can the Korean War serve as a precedent for

the legality of the Vietnam war. That action was author

ized by a resolution of the United Nations Security Coun

cil as a multi-lateral peacekeeping action. On the other

hand, even if it is assumed that the Korean War was

an executive usurpation of the congressional power to

declare war, it cannot be said that this usurpation is pre

cedent for subsequent usurpation of the Congress’ war

power. In Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer,

343 U.S. 579 (1952) the government argued that President

Truman had the power to seize the steel mills because on

several occasions other Presidents bad seized private

businesses in emergency situations. The court rejected

the argument, stating, at 588,

It is said that other presidents without Con

gressional authority have taken possession of pri

vate business enterprises in order to settle labor

disputes. But even if this be true, Congress has

not thereby lost its exclusive constitutional author

ity to make laws necessary and proper to carry

out the powers vested by the Constitution “in the

Government of the United States, or any De

partment of Offices thereof.” (Italics provided.)

21

In short, there is no precedent for the proposition that

the Constitution allows the President to fight a large-scale

undeclared war without Congressional approval.

Despite the historical limitations on the Commander-in-

Chief powers, the executive argues that the inferred

powers to repel attack justify his action in Vietnam.

State Department Brief, 565. Sometimes the executive

must of necessity commit our armed forces before Con

gress has an opportunity to declare war. The Brig Amy

Warwick, 2 Black 685 (1863). An example of this was

President Roosevelt’s forced and immediate response in

"World "War IT to an armed attack on the United States

before he asked Congress to declare war on Japan. From

this incontrovertible fact of political life, the executive ar

gues that it can carry on a war, regardless of the sudden

ness of the attack, whenever the executive feels any

belligerent act on the part of a foreign power requires a

response. During the past three and one-half years,

the executive has conducted large-scale military opera

tions in Vietnam. There has been more than ample

time during this period for the executive to ask for a

Congressional declaration of war. Yet, it is the position

of the executive branch that congressional action is en

tirely unnecessary. State Department Brief, 583. The

executive branch argues that the President had the power

in his sole discretion to escalate the war from the point

of repelling alleged, and as yet unproven, attacks on

a destroyer in the Gulf of Tonkin to a point where over

half of a million men are engaged in military operations

and where twice as much bomb tonnage has been dropped

than was dropped on all of America’s enemies in World

War II. This argument, if accepted, is a complete nulli

fication of Congress’ power to declare war. The only way

the Congressional power to declare war is to have any

meaning is for this court to hold that the President has

the power to repel sudden armed attacks, but that he

22

must obtain a Congressional declaration of general or

limited war as soon as possible. This guideline was

followed by President Roosevelt in World War II, and

presents a vital check on the power of the President to

commence an enormous war on the basis of a minor

international incident. Viewed in this light, the Execu

tive power to repel attack does not authorize the war in

Vietnam, since the Executive had and has ample time in

which to secure a Congressional declaration of war. He

may not usurp Congress’ ultimate legislative responsibility

under the Constitution. O’Neal v. United States, 140 F. 2d

908 (6th Cir., 1944), cert, denied 322 U.S. 729 (1944).

IV.

The unilateral action of the United States in Vietnam

violates the duties and obligations this country has

assumed as a member of the United Nations and di

rectly conflicts with the clear provisions of the SEATO

treaty.3

The United States Constitution, Article VI, Clause

2, states:

. . . all treaties made . . . under the authority

of the United States shall be the supreme law of

the land . . . and the judges in every state shall

be bound thereby.

This is a clear constitutional mandate to the courts that

theirs is the duty, not simply the prerogative, to enforce

the provisions of the treaties to which this country is a

valid signatory. Certainly, if the courts are bound to

enforce the provisions of such treaties, they are free to

3South East Asia Collective Defense Treaty, 6 U. S. T. 81,

T. I. A. S. No. 3170, 209 U. N. T. S. 28 (1955), hereinafter

cited as SEATO treaty.

interpret and apply the provisions thereof. Petitioner’s

contention is that past and present participation of the

United States Armed Forces in Vietnam is in direct viola

tion of this country’s treaties. It is the duty of this court

to weigh the legality of the conduct of the United States

Government in light of our treaties, and in addition, to

adjudicate personal rights affected thereby. San Lorenzo

Title and Improvement Co. v. Caples, 48 S.W. 2d 329

(Texas 1932).

A. T he present war has been entered into and conducted

in direct contravention o f A rticle 3 3 ( 1 ) o f the U nited

N ations Charter as it d isrupted “ a peacefu l so lu tion ”

under the Geneva Accords.

The United Nations Charter, June 26, 1945, 59 Stat. 1031

(1945), T. S. No. 993, Article 33(1), states:

the parties to any dispute, the continuance of which

is likely to endanger the maintenance of inter

national peace and security, shall first of all,

seek a solution by negotiation.

The Geneva: Accords'' was a “peaceful solution” worked

out by the main parties in the struggle of the Viet Minh

against French colonial rule. A direct sabotage of the

Geneva Accords’ peaceful solution was engineered by

the United States’ refusal to abide by the election pro

visions agreed upon by the parties to the Accords in

1954. When the United States began to assume the role

of the French in Southeast Asia, and the Viet Minh

began to resist, the United States did not abide by

Article 33(1) of the United Nations Charter, supra, by

submitting the dispute to the Security Counsel or by

iGeneva Conference on the Problem of Restoring Peace in

Indo-China, Great Britain, Misc. No. 20 (1954); (Cmd. 9239);

60 A. J. I. L. 629 (1966), hereinafter cited as Geneva Accords.

24

attempting to seek a solution by negotiation. The basie

purpose of Article 33(1) is to limit the use of unilateral

force by unilateral decision when there is time to go

to the Security Council. Not only did the United States

undermine an existing joeaceful “solution by negotia

tion” in Vietnam, but it compounded its sins by refusing

to submit the dispute arising out of the sabotage of the

Geneva Accords to the Council until fully two years

after the major portion of the conflict began and nearly

four years after we had undertaken a major commitment

to the Saigon regime’s effort to remain in power in the

face of growing and eminently more potentially suc

cessful challenges to their assumed authority. By 1962,

fully 10,000 United States troops were actually involved

in the effort to combat this growing insurgency, yet

the United States did not call for United Nations review

until 1966. This delay on the part of the United States

is in direct contravention of our duties and obligations

under the Charter of the United Nations, which Article

VI, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, makes the

“supreme law of the land.”

B. The Charter’s exceptional authorization o f collective

and individual self-defense is unavailable as a ju sti

fication fo r U nited States in tervention in V ietnam .

The Executive generally claims as a defense to its partic

ipation in Vietnam authorization under the United

Nations Charter, Article 51. State Department Brief,

567. Article 51 states:

Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the

inherent right of individual or collective self-

defense if an armed attack occurs against a mem

ber of the United Nations . . .

The facts overwhelmingly point to a patent fabrication on

this country’s part in characterizing the action of the

25

Viet Cong insurgents and their North Vietnamese counter

parts as an “armed attack” within the obvious meaning

of Article 51. South Vietnam is not a “member of the

United Nations” and even its characterization as a “na

tion” may be validly questioned. Fully two-thirds of

its present land area was controled by the Viet Minh

under Ho Chi Minh in 1954—who, for the most part,

withdrew to await elections in accordance with the dic

tates of the Geneva Conference of 1954. LaCourtre,

The Two Vietnams, pp. 290-358 (1966). They left be

hind certain of their forces as a practical matter because

they were suspicious (and justifiably so) of Saigon’s

intentions, and also to counter the almost immediate sup

planting of the French military and economic effort by

that of the United States. Fall, Vietnam Witness 1953-

1966 (1966). The Executive itself admits that from 1957

until 1962 there was a gradual infiltration of approxi

mately “23,000 armed and unarmed guerrillas” from North

Vietnam to the South. State Department Brief, 576.

The Executive chooses to term this gradual infiltration

of South Vietnam by guerrillas, largely South Vietnamese

in origin (State Department Brief, 576), as an “armed

attack” triggering the right of collective self-defense.

This definition of “armed attack” hardly squares with

what the United Nations defined it to be (Unanimous vote

of the General Assembly of the United Nations, 1st

Sess.. Resolution 95[1]):

Self-defense is permissible only when the necessity

for action is instant, overwhelming, and leaving

no choice of means and no moment for delibera

tion.

United States participation in the unhappy state of affairs

in Vietnam began in 1954. It seems logical that the very

party that had ended one hundred years of colonial dom

ination by a foreign power could be expected to guar

antee for itself, by leaving behind certain elements of its

26

forces, participation in the affairs of the country they had

freed after many years of bloody struggle without being,

of necessity, labeled an armed attacker. Majority Leader

Mansfield, Report to the Senate, 90th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1967), has made it clear that the infiltration of signif

icant numbers of men and material from North Vietnam

began only after massive United States’ intervention in

South Vietnam and the bombing of North Vietnamese

territory itself. Self-defense is legally permissible only

in response to particularly grave, immediate emergencies.

Any such claim to the right of self-defense is unavailable

to South Vietnam and, a fortiori, to the United States

acting as any ally in collective self-defense with South

Vietnam.

C. T he U nited States has violated the exp licit directives of

the SEATO Treaty under w hich it purports to justify

its unilateral in tervention.

The Executive has argued that the President may com

mit the nation to war in order to fulfill the treaty obliga

tions of the United States. State Department Brief, 584.

The argument is that the SEATO Treaty provides that

an armed attack against one of the parties is a threat to

all, and that each signatory may act to meet the threat in

accordance with its “constitutional processes.” State

Department Brief, 585. Executive action has shown

that the executive considers the term “constitutional

processes” to mean that the United States can fight a

full-scale war in Southeast Asia when the President, in

his sole discretion, decides to fight. This argument

is faulty on two grounds. First, a treaty cannot order

what the Constitution forbids, Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1

(1957); United States v. Minnesota, 270 U.S. 181, 207-

208 (1926); and second, the Constitution provides that

Congress, not the President, shall make the final decision

to go to war. Congress must therefore decide whether

27

particular treaty obligations require entry into a war.

When the SEATO Treaty says that resistance is to be

effected according to the “constitutional processes” of

the signatories, United States Constitutional law dic

tates that Congress must make the decision. If the

President makes the decision, and the proper inter

pretation of the treaty is that this is permissible, then

the treaty violates the constitution and cannot be fol

lowed. If the proper interpretation of the SEATO treaty

is that Congress must decide when to enter a war, then

the Executive action so far in Vietnam violates the

SEATO treaty because it was not done in accordance

with the “constitutional processes” of the United States.

In either case, the treaty obligations of the United

States do not authorize the present Executive action in

Vietnam. The fallacy of the government’s position, which

in effect states that there may be a declaration of war by

treaty, becomes even more obvious when it is considered

in light of the fact that the Constitution requires only

executive and Senate action in binding this country to

a treaty obligation, United States Constitution, Article

2, Clause 2, Section 2, whereas the concurrence of both

houses of Congress is necessary in order to ultimately

commit the nation to war. United States Constitution,

Article 1, Section 8, Clause 11.

Assuming arguendo that the government’s contention

that there was an armed attack is correct, then it must

justify its intervention under Article IV (1) of the

SEATO Treaty. This deals with the situation when there

is “aggression by means of armed attack” and provides

that “ [mjeasures taken under this paragraph shall be

immediately reported to the Security Council of the

United Nations.” (Italics added.) The United States

intervention in Vietnam began as early as 1954, and yet

our government did not report the situation to the

United Nations until recently. Our government ignored

28

the letter and the spirit of paragraph 1 of Article IV,

and its actions cannot be justified thereunder.

A more logical analysis of the Vietnam conflict and more

in conformity with the government’s admission of a

gradual infiltration, supra, would bring the United States

intervention within paragraph 2 of Article IV which

provides tha t:

“If in the opinion of any of the Parties, the

inviolability or the integrity of the territory or

the sovereignty or political independence of any

Party in the treaty areas . . . is threatened in any

way other than by armed attach or is affected or

threatened by any fact or situation which might

endanger the peace of the area, the Parties shall

consult immediately in order to agree on the

measures which should be taken for the common

defense. (Italics added.)

This provision requires that the parties make a col

lective determination prior to taking any action. If

this provision, rather than paragraph 1 of Article IV,

does not govern the Vietnam conflict, it is difficult to

imagine what purpose it serves. If it does cover the

Vietnam war, the United States intervention is in con

travention thereof, as there was no consultation among

the parties and there was no collective determination as

to the measures which should be taken.

No matter which provision governs, paragraph 1 or

paragraph 2 of Article IV, the United States flagrantly

violated its terms. Though charged with the faithful

execution of the law of the land, the President has ignored

the clear dictates of our treaties, and in so doing, has

engaged the nation in an illegal war. While it is

true that a later inconsistent statute may modify a treaty,

Hackworth, Digest of International Law 185, 186 (1943),

the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, 78 Stat. 384 (1964), did not

have this effect. A treaty will not be deemed modified

29

or abrogated by a later act of Congress unless such pur

pose on the jjart of Congress is clear. Cook v. United

States, 288 U.S. 102, 120 (1933). The Tonkin Gulf

Eesolution explicitly provides that the President’s actions

shall be “ [cjonsonant with the Constitution of the United

States and the Charter of the United Nations and in

accordance with its obligations under the Southeast

Asia Collective Defense Treaty . . .” In addition to show

ing that Congress did not intend, to modify any of our

treaty commitments, this provision also demonstrates that

the President has far exceeded any powers delegated

to him by the Congress.

V .

The United States, as a member of the United

Nations, and of the civilized world community, is bound

by international law to refrain from disturbing efforts

among other nations and peoples to peacefully settle

their differences.

Where there is no treaty that validly supersedes it, or

where there is no controlling executive or legislative act

or judicial decision, resort must be had to international

law, and the customs and practices of civilized nations.

United States v. Macintosh, 283 U.S. 605 (1931). As this

court said in The Hub ana, 175 U.S. 677 (1900) at 700:

International law is part of the law of the United

States and must be ascertained and administered

by the courts of justice of appropriate jurisdiction

as often as questions of right depending upon it

are duly presented for their determination.

30

A. T he war in V ietnam is a civil war, and n o right o f

in tervention on the part o f the U nited States exists on

behalf o f one or the other o f the factions involved

therein.

From 1946 onward, immediately following the failure

of France at the end of World War II to recognize and

provide for basic nationalistic sentiment in Indo-China,

the Viet Minh under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh

began its struggle to oust the French from colonial

control of Southeast Asia. This effort culminated in

success in 1954 at Dien Bein Phu. The Geneva Accords

provided for the establishment of a national government

by free elections two years hence in 1956. This was to

provide for a cooling-off period for the antagonistic

elements among the indigenous people of Vietnam itself,

and a suitable period for the withdrawal of foreign

troops. When the formula of Geneva failed to pro

duce this single governmental entity, due to the outside

sabotage of the election provisions by the United States

which had immediately supplanted the defeated French

influence in Vietnam, the insurgency began in the South.

This insurgency was aided and fostered by both Southern

and Northern elements which had previously withdrawn to

the North in accordance with the dictates of the Geneva

Conference. That this was then and now is a civil war

in nature, is also shown by the following facts:

1. The Viet Minh fully controlled two-thirds of the

total land area of the whole of Vietnam in 1954,

at the conclusion of the French War. LaCourtre,

The Two Vietnams, pp. 290-358 (1966);

2. The United States has claimed that the infiltration

of 40,000 armed guerrillas constituted the basis

for its intervention, and yet admits that these

troops were Southern in origin. State Department

Brief, 566;

31

3. The Geneva Conference recognized all Vietnam as

on entity, and observers at the time of the begin

ning of the conflict acknowledged that. Ho Chi

Minh was indeed the national leader of all of

Vietnam and was assured of popular election, if

such elections were held at the time. Fall, Vietnam

Witness 1953-1966 (1966).

The constant rhetoric of United States policy makers in

characterizing the conflict in Vietnam as being precipitated

by an invasion from the North is not accurate. By the

terms of the Geneva Accords, there was no legal en

tity as a nation from which an armed invasion could

be launched, and there was no legal entity as a nation

invaded. Both areas were deemed one state. It is

also significant that North Vietnam has never recognized

the South as a state and considers its role as simply

one of attempted forceful reunion. There is absolutely

no precedent for the United States to massively inter

vene in behalf of one side of a civil war. I t is significant

to note that in the Spanish Civil War, neither Germany

and Italy on behalf of Franco, nor the Soviet Union on

behalf on the Loyalists, claimed a right to bomb each

other’s territory when they intervened, nor did they

claim the right to intervene massive numbers of their

own forces. Padelford, International Law and Diplomacy

in the Spanish Civil War (1939). It has been shown

that the absurdity of our claim of legal intervention could

be carried to the extent that North Vietnam in turn could

correspondingly claim, the right to bomb the territory of

the United States. Falk, Vietnam Critique, 75 Yale

L.J. 1134 (1966).

Finally, the Korean conflict provides no precedent

for our action in South Vietnam. Korea was indeed an

armed attack by an independent country upon the ter

ritory of another independent country, and internationally

recognized as such. The United States acted after going

32

before the Security Council of the United Nations; and

there was a total of thirty-two nations involved fighting

to repel aggression under United Nations authorization.

The United States never claimed any right of “collective’

self-defense” in Korea, but acted in accordance with

international law under United Nations auspices. The

token aid given in South Vietnam by “allies” of the

United States (under intense United States pressure)

can hardly be analogized to the participation of foreign

nations in the Korean conflict. McDougal and Associates,

Studies in World Public Order, 718-760 (1960).

B. U nited States participation is a direct sabotage of the

Geneva Accords, w hich w ere arrived at in accordance

with the “ P eacefu l Settlem ent” provisions o f A rticle 31

of the U nited N ations Charter.

The American military presence in South Vietnam

from its inception until the present time is in direct

violation of the Geneva Conference and of the plan

for “peaceful settlement” of the conflict between indigenous

forces of the Vietnamese nation which was devised by that

conference in 1954.

As previously noted, the defeat of the French after

eight years of war left the Viet Minh occupying the entire

area North of the thirteenth parallel. Under the terms

of the Geneva Accords, the Viet Minh agreed to withdraw

above the seventeenth parallel in exchange for the with

drawal of all foreign troops. Geneva Accords, Chapter

II, Article 12, pp. 631-32. Within two years elections

were to be held under international supervision to unify

the country so that the temporary division of Vietnam

into a North and South zone would end by July of 1956.

Geneva Accords, Final Declaration, pp. 643-44. The

extent of control over the land area that the forces of

Ho Chi Minh exercised at that time, is shown by the

33

plan for withdrawal and the stipulation of day by which

all forces were to withdraw to the respective territories,

as per the Geneva Accords, supra, Article 15(2):

The withdrawals and transfers shall be effected

in the following order and within the following

periods (from the date of the entry into force of

the present Agreement):

Forces of French Union

Hanoi perimeter __________ __ _______ 80 days

Haiduong perimeter ................... .............. 100 days

Haiphong perimeter ________________ 300 days

Forces of the People’s Army of Viet Nam

Ham Tan and Xuyenmoc provisional as

sembly area --------------------- ---------- 80 days

Central Viet Nam provisional assembly

area first installment ...................... ..... . 80 days

Plaine des Jones provisional assembly

area .......................................... ............... 100 days

Central Viet Nam provisional assembly

area second installment „......... ........... 100 days

Pointe Caman provisional assembly area 200 days

Central Viet Nam provisional assembly

area last installment ____________ .... 300 days

From the above it is obvious that the French colonial

power at the time and its small contingent of Vietnamese

occupied only the major port cities, insofar as land area,

and the Viet Minh was the only other significant military

presence in the country. It is further obvious that Ho

Chi Minh had three hundred days to withdraw his forces

from the South. It is often claimed by the United States

that he failed to withdraw his troops within the time

sequence allowed. This fact is used by the United

States to claim a material breach of the Geneva Accords.

State Department Brief, 577-78. However, the Fourth

Interim Report of the International Control Commission,

34

Vietnam No. 3, Cmd. No. 9654 (1955), shows that the

Hanoi interim government generally kept its agreement

to withdraw its troops and to eschew violence. It is

intimated in that report that Hanoi was so sure of

winning the agreed upon elections that it did not wish

to risk alienating the people in the South upon whom

Hanoi depended for its election success. But beginning

in September, 1954, the South Vietnamese temporary

government and the United States made clear their

intention to sabotage the settlement engineered in Geneva

less than one and half months before.

The Final Declaration of the Geneva Accords, 643-

44 provided:

No military base under the control of a foreign

state may be established in the re-grouping zones of

the two parties, the zones . . . shall not constitute

part of any military alliance . . .

The military demarcation line is provisional and

should not in any way be interpreted as constitut

ing a political or territorial boundary.

General elections shall be held in July, 1956 under

the supervision of an international commission

composed of representatives of the member states

of the International commission . . . consultations

will be held on this subject between the competent

representative authorities of the two zones from the

20th of July, 1955 onwards.

This declaration forbids foreign military bases, states

that the North-South demarcation line is completely

arbitrary, forbids any political interpretation of the boun

dary, and provides for elections to unite the country

under one head. Although the United States Declaration

on Indo-China, 31 Dept, of State Bulletin 162 (1954),

issued in lieu of our actually signing the Geneva Accords,

seemed to indicate that the United States would abide by

the accords:

35

the Government of the United States being resolved

to the strengthening of peace . . . declares . . .

(i) that it will refrain from the threat or use of

force to disturb them.

The SEATO treaty made it immediately clear that the

above quoted declaration was worth no more than the

paper it was written on. Under the protocol to the

SEATO treaty, appended to the main treaty, the parties

designated

“For the purposes of Article 4 . . . the free

territory under the jurisdiction of the State of

Vietnam . . . ”

Less than one and a half months after the Geneva Accords

were signed in September, 1954, this protocol, made it

abundantly clear that the United States did not intend

to abide by the spirit of the Geneva Accords which, as

shown above, called for free elections and the non-

recognition of territorial division in Vietnam itself. The

SEATO treaty further established that the United States

considered the “free territory of the State of Vietnam”

as coming within the alliance’s protection, by stating

in Article 4, Clause 2, of that treaty that:

if in the opinion of the parties, the inviolability

or the independence of the territory, or the sover

eignty, or political independence of any state or

territory to which the provisions of Paragraph 1 of

this article apply, is threatened in any way other

than by armed attack, the parties shall consult im

mediately to agree on measures to be taken.

Article 4, Clause 3, of the protocol continues:

each party recognizes that aggression by means

of armed attack against any state or territory which

the parties may hereinafter designate would en

danger its own peace and safety and agrees it