Jones v. The Continental Corporation Brief of Appellees

Public Court Documents

September 9, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jones v. The Continental Corporation Brief of Appellees, 1986. f0802853-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a4bbfe1e-b3eb-4815-b45b-c928423a06f3/jones-v-the-continental-corporation-brief-of-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

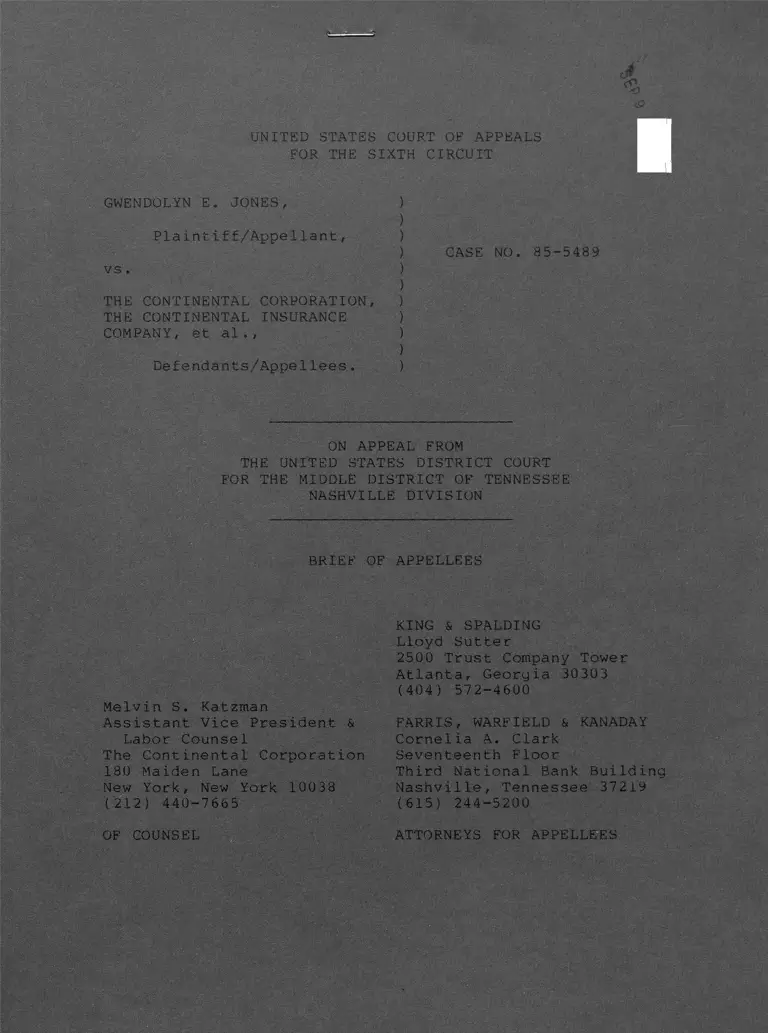

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

GWENDOLYN E. JONES', )

: ' ' ) ̂ : : V

Plaintif£/AppelXant, )

'■ ■ ' ̂ .. ) .. CASE NO. 8,5-5 489

vs. )

)

THE CONTINENTAL CORPORATION, }

THE CONTINENTAL INSURANCE )

COMPANY, et al., )

)

Defendants/Appellees. )

ON APPEAL FROM

THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

NASHVILLE DIVISION

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

Melvin S. Katzman

Assistant Vice President &

Labor Counsel

The Continental Corporation

180 Maiden Lane

New York, New York 10038

(212) 440-7665

OF COUNSEL

KING & SPALDING

Lloyd Sutter

2500 Trust Company Tower

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 572-4600

FARRIS, WARFIELD & KANADAY

Cornelia A. Clark

Seventeenth Floor

Third National Bank Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

(615) 244-5200

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEES

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

GWENDOLYN E. JONES, )

)

Plaintiff/Appellant, )

)

vs. )

)

THE CONTINENTAL CORPORATION, )

THE CONTINENTAL INSURANCE )

COMPANY, et al., )

)

Defendants/Appellees. )

CASE NO. 85-5489

ON APPEAL FROM

THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

NASHVILLE DIVISION

BRIEF OF APPELLEES

Melvin S. Katzman

Assistant Vice President &

Labor Counsel

The Continental Corporation

180 Maiden Lane

New York, New York 10038

(212) 440-7665

OF COUNSEL

KING & SPALDING

Lloyd Sutter

2500 Trust Company Tower

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 572-4600

FARRIS, WARFIELD & KANADAY

Cornelia A. Clark

Seventeenth Floor

Third National Bank Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

(615) 244-5200

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Contents..................................... i

Table of Citations.... ............................... ii

Disclosure of Corporate Affiliations

and Financial Interest (6th Cir.R.25).............. iv

Fact Sheet (6th Cir , R . 20 ) . . . ........................ v

Statement of the Issues............................... 1

Statement of the Case.... ............................ 1

Statement of the Facts......... 4

Fee Award Against Counsel......... 4

Fee Award Against Ms. Jones..... ...............

Costs Taxed Against Ms. Jones................... 8

Argument and Authorities..............................

I. Attorneys' Fees were correctly

Awarded Against Counsel.........................

A. Evidentiary Hearing Issue.................. 9

B. Counsel Multiplied Proceedings

Unreasonably and Vexatiously............... 11

II. The Award of Attorneys' Fees

Against Ms. Jones Was Proper.................... 12

III. Taxation of Costs Against

Ms. Jones was Appropriate....................... 15

Conclusion............................................ 46

Certificate of Service................................ 47

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

Judicial Decisions

Badillo v. Central Steel & Wire Co.,

717 F.2d 1160 (7th Cir. 1983).................. 16

Carrion v. Yeshiva University,

535 F. 2d 722 ( 2d Cir. 1976).................... 14

Christianburq Garment Co. v. EEOC,

• 434 U.S. 412 ( 1978 )............................ 13 , 16

Coyne-Delaney Co., Inc. v. Capital.Development Bd.,

717 F. 2d 385 ( 7th Cir. 1983)................... 16

Cross v. General Motors Corp.,

721 F.2d 1152 (8th Cir.) ,

cert. denied 104 S.Ct. 2364 ( 1983)............. 16

Delta Air Lines, Inc, v. August,

450 U.S. 346 ( 1981)........................ '---- 15

Glass v. Pfeffer,

657 F. 2d 252 ( 10th Cir. 1981).................. 9

Hall v . Cole,

417 U.S. 1 ( 1973)............................... 12

Hudson v. Nabisco Brands, Inc.,

“7 58 F. 2d 1237 (Tth Cir. 1985).................. 16

Huqhes v. Rowe,

449 U.S. 5 (1980).............................. 13

Link v. Wabash Railroad Co.,

370 U.S. 626 (1962)............................ H / 12

McDowell v. Safeway Stores, Inc.,

758 F. 2d 1293 ( 8th Cir. 1985).................. 15

Miles v. Dickson,

387 F. 2d 716 (5th Cir. 1967)................... 9

Poe v. John Deere Co.,

695 F. 2d 1103 (8th Cir. 1982).................. 16

Price v . Pelka ,

690 F.2d 98 (6th Cir. 1982) 14

Page(s)

Reynolds v. Humko Products,

756 F. 2d 469 ( 6th Cir. 1985)........... ....... 12

Roadway Express, Inc, v. Piper,

447 U.S. 752 (1980). .7777...................... 9,11,12

Smith v. Smythe-Cramer Co.,

754 F. 2d 180 (6th Cir. 1985)................... 14

Textor v. Board of Regents,

32 EPD 11 33,729 ( 7th Cir. 1983)................ 9 , 10

Tonti v .Petropoulous,

656 F. 2d 212 (6th Cir. 1981)................... 14

United States v. Ross,

535 F.2d 346 T6th Cir. 1976 )................... 12

West Virginia v. Charles Pfizer & Co.,

44 0 F . 2d 1079 ( 2d C i r 7T",

cert, denied 404 U.S. 871 (1971)............. . 12

White v. New Hampshire Dept, of Employee Services,

455 U.S. 455 (1982)............................ 3 , 4

Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 1920 . ........... ......... ............... 16

28 U.S.C. § 1927 ......................... ........... 2,12,13

42 U.S.C. § 1981......................................... 4

42 U.S.C. § 1988..................................... 13

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et_ seq.................................. 4

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k)................................... 2

Rules

Fed .R.Civ.P. 41(b)...................................... 6

Fed.R.Civ.P. 52(a)...................................

Fed.R.Civ.P. 54(d)................................... 16

Local Rules, M.D.Tenn., 11(a).......................

Local Rules, M.D.Tenn., 11(b).......................

i i i

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

GWENDOLYN E. JONES, )

)

Plaintiff/Appellant, )

)

vs. )

)

THE CONTINENTAL CORPORATION, )

THE CONTINENTAL INSURANCE )

COMPANY, et al., )

)

Defendants/Appellees. )

CASE NO. 85-5489

DISCLOSURE OF CORPORATE AFFILIATIONS

AND FINANCIAL INTEREST

Pursuant to Sixth Circuit Rule 25, Defendants/Appellees,

The Continental Corporation and The Continental Insurance

Company, make the following disclosure:

1. The Continental Insurance Company is a subsidiary

of The Continental Corporation, which is a publicly owned

corporation.

2. There is no other publicly owned corporation,

not a party to the appeal, that has a substantial financial

interest in the outcome that should be disclosed.

Lloyd Sutter

Attorney for

Defendants/Appellees

September 5, 1985

iv

FACT SHEET FOR TITLE VII APPEALS

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Case Name and Number: Gwendolyn E. Jones vs. The Continental

Corporation, The Continental Insurance Company, et al.

(seven individual defendants); Nos. 84-5658 (on the

merits) and 85-5489 (on costs and attorneys' fees).

Person Reporting: Counsel for Defendants/Appellees.

1. Date EEOC complaint(s) filed:

a. May __, 1980

b. February 13, 1982

c. September 6, 1983

d. December 20, 1983

2 .

3.

Was any compromise or settlement reached by the state

civil rights agency? YES By EEOC? YES. (Only as to

1980 charge; settlement effectuated July 14, 1980).

Date EEOC right to sue letter(s) issued:

a. June 30, 1982.

b. November 15, 1983.

c. December 22, 1983.

4. Date present action filed: June 23, 1982.

5. Have all filing been timely? Yes, but only as to

claims occurring since August, 1981. There are no

"tolling" arguments involved.

6. Nature of discrimination alleged and date(s) of occurrence

a. promotion claim - October 1, 1981.

b. compensation claim - "continuing."

c. treatment claim - "continuing."

d. retaliation claims - February to August, 1983.

e. termination claim - August 1, 1983.

v

7. Disposition: On Rule 41(b) motion, all but the October

1, 1981 promotion, the February-August, 1983 retaliation,

and the August, 1983 termination claims were decided in

defendants/appellees' favor. On June 29, 1984, the

District Court decided all remaining claims in favor of

defendants/appellees.

The instant appeal (as opposed to that on the merits,

Case No. 84-5658) involves memoranda, orders and judgment

entered January 23, 1985, and March 22, 1985, awarding

attorneys' fees against plaintiff/appellant and her

counsel, as well as approving costs taxed against

plaintiff/appellant.

vi

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Was the award of attorneys' fees against

plaintiff/appellant's (hereinafter Ms. Jones) counsel

appropriate?

A. Was counsel afforded the required due

process, i.e., notice and an opportunity to be heard on the

record?

B. Did counsel's conduct, as it related to the

motion to dismiss and pretrial order, so "unreasonably and

vexatiously" multiply the proceedings as to justify the award?

2. Was the award of attorneys’ fees against

Ms. Jones appropriate with respect to the termination issue?

3. Was the taxation of cost against Ms. Jones

appropriate notwithstanding her present financial situation?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE1

Ms. Jones and her counsel appeal here from Memoranda,

Orders, and Judgment entered January 23, 1985 (A. 94), and *

March 22, 1985 (A. 106), taxing $6,540.15 in costs against

Ms. Jones under Fed.R.Civ.P. 54(d) and 28 U.S.C. § 1920, and

awarding attorneys’ fees to defendants/appellees (hereinafter

the Company) against Ms. Jones in the amount of $4,740.25 with

respect to the termination claim under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1988 and

Counsel for Ms. Jones did not prepare and serve a Joint

Appendix with their brief. Consequently, defense counsel

have done so. References thereto are to A. (page number).

2000e-5(k) and against her counsel in the amount of $5,414.50

for certain conduct during the litigation under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1927 and the trial court's "inherent powers."

The Company timely filed with the Clerk its Bill of

Costs. (A. 17). Ms. Jones' counsel never challenged before

the Clerk or the Court any item contained in the Bill of Costs.

Rather, after the Court's approval of the taxed costs in its

January 23, 1985, Memorandum, Ms. Jones raised as an argument

for "excusing" her from the costs that she would be financially

inconvenienced. (A. 75-79). In that she was employed,

Ms. Jones could not and did not claim indigency in her

affidavit. (A. 77).

Concurrently with filing its Bills of Costs, the

Company filed its Petition for Attorneys' Fees; and, in

footnote 10 at page 21 of its Memorandum in support thereof,

suggested that the Court might factually and legally determine

that some part of the responsibility therefor lay with

Ms. Jones' counsel, rather than Ms. Jones. (A. 19, 41).

In her initial response to the Company's Petition,

Ms. Jones ignored footnote 10, as well as any contest of the

time and fee claims. (A. 57-61). In essence, Ms. Jones'

argument was one of inappropriateness of any assessment of

attorneys' fees. Less than a week later, Ms. Jones attacked

-2-

the Court's jurisdiction and sought a stay pending appellate

court determination of the merits.2

Following the trial court's decision of January 23,

1985 (A. 94), Ms. Jones and her counsel filed a motion for a

new trial or to alter or amend the attorneys' fees/costs

determination, and later an Amended Memorandum (A. 68) together

with four affidavits (A. 75-88).

Defense counsel filed two memorandum, contending that

the January 23, 1985, determination satisfied the requirements

of Rule 52(a) and that, while they did not oppose scheduling of

a "hearing," no such proceeding seemed necessary or

appropriate. (A. 62 and 89).

The trial court subsequently entered its March 22,

1985, Memorandum, Order and Judgment. (A. 106).

Ms. Jones and her counsel then filed their Notice of

Appeal. (A. 109).

A separate appeal (No. 84-5658) is pending on the

merits of the underlying action. It involved allegations of

race and sex discrimination with respect to compensation,

promotion, treatment/retaliation, and termination; and it was

This issue was appropriately abandoned on appeal. See

White v. New Hampshire Dept, of Employee Services, 455"

U.S. 445 (1982) and cases cited in trial court Memorandum

of January 23, 1985. (A. 95-96).

-3-

brought under the 1866 and 1964 Civil Rights Acts, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981 and 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. (Title VII). The parent

corporation (The Continental Corporation), its subsidiary which

employed Ms. Jones (The Continental Insurance Company), and

seven individual defendants, prevailed entirely as reflected in

the Order and Judgment entered June 29, 1984. (A. 198).

On May 22, 1985, the Company also filed a motion to

consolidate the appeals in No. 84-5658 and the instant case.

That motion is still pending. See generally, White v. New

Hampshire Department of Employment Services, supra at 454

(desirability of consolidation of appeals involving fees and

costs with those on the merits).

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

The Company believes that the facts material to the

instant appeal differ significantly from those stated in

plaintiff/appellant's brief.

The Fee Award

Against Counsel

The District Court entered its award of attorneys'

fees against counsel not on the basis of their "sloppy

pleading" only, but rather as a result of their conduct, i.e.,

failure to respond properly and timely to the Company's motion

to dismiss and refusal tô sign the pretrial order absent the

Company's waiver of any subsequent entitlement to attorneys'

' fees. (A 97-98, 107-08).

-4-

This action was commenced on June 23, 1982, with

filing of a complaint that was, on July 9, 1982, amended to

recite receipt of the requisite EEOC "right to sue" letter.

(A. Ill, see A. 4, docket entry 2).

The Confany responded in two ways: (1) with a motion

to dismiss, asserting inter alia that service of process was

deficient, that inappropriate defendants were named, and that

improper legal claims had been asserted (A. see A. 4, docket

entries 6 and 7; see also A. 21-23); and (2) with a letter

(A. 42) agreeing to such extension of time as might be

necessary for Ms. Jones to file an amended complaint in lieu of

responding to the motion.

Counsel for Ms. Jones merely amended the complaint to

add the subsidiary employer as a defendant (A. 120-21) and did

not- timely respond to the Company's renewed motion to dismiss,

although ordered to do so on or before November 10, 1982

(A. 122; see also A. 5, docket entries 33 and 33a; A. 6, docket

entries 37, 43-46; A. 7, docket entries 64 and 66).

In addition, although counsel for the parties, as

required by Local Rule 11(a), had exchanged proposed drafts of

------------.-------- ’ ......... ............................. ... ......................~ ........an Agreed Upon Pretrial Order and had reached agreement on its

contents through an all-day conference on December 9, 1982,

(including elimination of a number of issues raised in the

-5-

motion to dismiss, see A. 140-41)., counsel for Ms. Jones

refused to sign the Agreed Upon Pretrial Order unless the

OniMiim»l1,ir~------ r I '*_• ' ----

- - -------------Gomgan^.waived its entitlement to any attorneys fees with

respect to the pending motion to dismiss (A. 124, 1.47-48) .

At a hearing on December 14, 1982, pursuant to the

Company's motion, the trial court "heard", inter alia, the

Agreed Upon Pretrial Order issue, ruled that he would try the

case without the Order, and directed defense counsel to file an

Answer. (A. 155, 158, 166).3 Without an Agreed Upon Pretrial

Order simplifying the issues, defense counsel were forced to

brief all issues under Local Rule 11(b)(A. 7, docket entry 67),

and be prepared to meet whatever evidence on all issues

Ms. Jones might introduce at trial.

In fact, defendants/appellees prevailed on their Rule

41(b) motion with respect to all but two issues: whether race

discrimination had occurred as a result of the relocation from

San Francisco of a white female supervising underwriter who

Ms. Jones claimed preempted her consideration for the position

and whether, if so, either of the two individual defendants

were personally liable under 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

When Ms. Jones' counsel was unavailable to meet with

defense counsel to prepare a pretrial order for the second

phase of the trial, defense counsel notified the Court

under Rule 11 (A. 10, docket entry 117), the Court

prepared its own, largely from the proposal of defense

counsel (A. 195-97).

-6-

The Fee Award

Against Ms. Jones

While the trial was recessed and before its scheduled

September 1983 resumption, Ms. Jones sent to a major customer

an unauthorized letter accusing one of its representatives of

"hatred and prejudice." (A.185).

When she could give no reason for having sent the

letter, her employment was terminated. (Interestingly, she was

also unable to explain why she sent it to the addressee,

Ms. Price, when it was the subject of a telephone discussion

between them. (A. 237-42))

The trial resumption was postponed to allow for

additional discovery on the termination and other issues4

raised by plaintiff/appellant in her again amended complaint.

Based upon her demeanor and other conduct during the

trial,5 the Court found Ms. Jones to lack credibility and to

Ms. Jones raised a number of "retaliation" issues which

the District Court found to be without merit (A. 204-05).

While Ms. Jones claimed she had been called a "goddamn

nigger" by a representative of the customer some two

months prior to her termination, she admitted on cross-

examination that she never reported it to any Company

representative (A. 235; see also A. 240) and she

acknowledged to Ms. Price that the July 15th letter was

not prompted by anything Ms. Price had done of a racial

nature. (A. 238, 240). The trial court was justified in

its refusal to credit Ms. Jones' testimony because of at

[Footnote cont'd next page]

-7-

have been completely unjustified in sending the letter. She

knew her claim of race and sex discrimination was frivolous

from the day she wrote the July 15 letter.

Costs Taxed

Against Ms. Jones

The Company timely filed its Bill of Costs pursuant

to the Local Rules. Ms. Jones neither appeared before the

Clerk to oppose any costs specified, nor filed any written

opposition thereto.

Ms. Jones' sole contention with respect to taxation

of costs against her is that, because she lost her job with the

Company, she will be financially inconvenienced if required to

pay the costs. (A. 75-79).

[Footnote continued]

least the following: (1) she was caught in a lie with

respect to the Hatcher training incident (221, 225-26,

231, 233-34); (2) she and her counsel had made a major

retaliation issue out of the lighting and desk location

situation as late as August 1983, but had never mentioned

any "racial epithet" incident before her employment was

terminated (A. 186-88); and (3) Ms. Jones and her counsel

had attempted to deceive the Court and defense counsel by

using an elaborate "script" for her rehearsed testimony

(A. 211-20, 223-24).

-8-

ARGUMENT AND AUTHORITIES

Ms. Jones objects to the award of attorneys' fees

against her counsel and against herself, as well as to taxation

of costs against her. Each issue will be discussed seriatim.

I .

Attorneys Fees

Were Correctly

Awarded Against Counsel

A. Evidentiary Hearing

Requirement Issue

None of the authorities6 cited by Ms. Jones in her

brief, pp. 14-15, stand for her contention that an evidentiary

hearing must be held before any assessment of attorneys' fees

is made against an attorney.

The Company does not disagree with the Supreme

Court's admonition in Roadway that

"[A ]ttorney's fees certainly should not be assessed

lightly or without fair notice and an opportunity for

hearing on the record."

Roadway Express, Inc, v. Piper, 447 U.S. 752, 757 (1980);

Textor v. Bd. of Regents, 32 EPD 1133,729 (7th Cir. 1983);

Glass v. Pfeffer, 557 F.2d 252 (10th Cir. 1981); and Miles

v. Dickson, 387 F.2d 716 (5th Cir. 1967). Miles and Glass

appear to have involved sua sponte trial court assessment

of costs or attorneys' fees against counsel concurrently

with entry of the final order on the merits. Textor

involved the erroneous imposition upon counsel of the

burden to prove that the award was not justified.

-9-

447 U.S. at 767.

However, not every order entered without a

preliminary adversary hearing offends due process, as the

Supreme Court noted in Link v. Wabash Railroad Co,, 370 U.S.

626, 663 (1962):

"But this does not mean that every order entered

without notice and a preliminary adversary hearing

offends due process. The adequacy of notice and

hearing respecting proceedings that may affect a

party's rights turns, to a considerable extent, on

the knowledge which the circumstances show such party

may be taken to have of the consequences of his own

conduct. The circumstances here [i.e., dismissal for

failure to prosecute] were such as to dispense with

the necessity for advance notice and hearing."

Similarly, the Seventh Circuit, in the Textor case relied upon

by Ms. Jones, observed that ". . .[Tjruly egregious conduct by

counsel may support a finding of willful abuse without any

inquiry about counsel's intent, . . . ." 32 EPD at 30, 516.

The Company believes that, under the circumstances of

the instant case, counsel were afforded all the "due process"

required. The Company petitioned for attorneys' fees in^

writing, supported by'affidavits^^nd memorandum of authorities.

Ms. Jones had an opportunity to and did reply. The January 23, \J

1985, Order followed. Ms. Jones, thereupon, filed a motion for

"new trial or to alter or amend" with respect to the costs and

attorneys' fees awards, together with affidavits and an amended

memorandum. The Court's Order of March 22, 1985 followed.

-10-

Furthermore, counsel failed to acknowledge that their

refusal to sign the pretrial order was the subject of a hearing

held on December 14, 1982. The effect of the conduct of

counsel for Ms. Jones was obvious; and the only evidence needed

was the record with respect to the motion to dismiss to which

counsel failed to timely respond, as well as the petition for a

pretrial conference, affidavits, unexecuted Agreed Upon

Pretrial Order.

The requirements of due process, as explained in

Roadway and Link, have been satisfied; and, therefore, no

procedural error occurred with respect to assessment of

attorneys' fees against counsel.

B. Counsel Multiplied the Proceedings

Unreasonably and Vexatiously

By failing to respond timely to the Company's motion

to dismiss, counsel left "all issues" unresolved through the

time by which the Agreed Upon Pretrial Order was required to be

developed. Then, after consenting to elimination of most

issues raised by the motion to dismiss in the Agreed Upon

Pretrial Order, counsel refused to sign this otherwise agreed

upon document unless the Company waived any entitlement to

attorneys' fees. Thus, the Court was forced to try the case

without a Pretrial Order and defense counsel was forced to meet

an "all issues" case both in its Trial Brief and at trial.

-11-

Ms. Jones relies upon two cases7 which antedate the

1980 amendment to 28 U.S.C. § 1927 in support of their

contention that the Company must show "bad faith" in order to

obtain an award of fees against counsel.

In a recent decision, this Court has noted the

availability of attorneys' fees under the amended § 1927, as

well as the Roadway "inherent powers" standard. Reynolds v.

Humko Products, 756 F.2d 469, 473-74 (1985). The "bad faith"

requirement applied, according to Reynolds, only under the

"inherent powers" standard.

The trial court was also correct in ignoring the

ultimate disposition on particular issues raised in the

Company's motion to dismiss. For, as the Supreme Court has

observed:

"But § 1927 does not distinguish between winners and

losers, or between plaintiffs and defendants. The

statute is indifferent to the equities of a dispute

and to the values advanced by the substantive law.

It is concerned only with limiting the abuse of court

processes."

Roadway supra, at 762. The Supreme Court also noted, however,

that "bad faith" could be found not only in the actions that

led to the lawsuit, but also in the conduct of the litigation.

Id. at 766, citing Hall v. Cole, 417 U.S. 1, 15 (1973).

United States v. Ross, 535 F.2d 346 (6th Cir. 1976); West

Virginia v. Charles Pfizer and Co., 440 F.2d 1079 (2d

Cir.), cert. denied 404 U.S. 871 (1971).

-12-

Counsel, by their conduct with respect to responding

to the motion to dismiss and failing to sign the Agreed Upon

Pretrial Order multiplied this litigation both "unreasonably

and vexatiously" within the meaning of § 1927 and in "bad

faith" as required under the "inherent powers" principle.

The award of attorneys' fees against counsel should,

therefore, be affirmed.

II.

The Award of Attorneys'

Fees Against Ms. Jones

______ Was Proper______

The standard for assessment of attorneys' fees

against a plaintiff in a Title VII/§ 1981 action has been

established by the Supreme Court in Christianburg Garment Co.

V. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412, 422 (1978):

"Hence, a plaintiff should not be assessed his

opponent's attorneys' fees unless a court finds that

his claim was frivilous, unreasonable, or groundless,

or that plaintiff continued to litigate after it

clearly became so. And, needless to say, if a

plaintiff is found to have brought or continued such

a claim in bad faith, there will be an even stronger

basis for charging him with attorneys' fees incurred

by the defense."

See also Hughes v. Rowe, 449 U.S. 5 (1980)(Christianburg

standard applies to 42 U.S.C. § 1988). Earlier, the Court

noted that proof of "subjective bad faith" was not required for

a defendant to recover attorneys fees. 434 U.S. at 421.

-13-

Judge Morton confined his award against Ms. Jones to

time expended by defense counsel with respect to a single

issue: her employment termination for writing a July 15, 1983

letter to the company's most valuable customer, complaining

that one of the customer's representatives had engaged in

"hatred and prejudice."

The trial court did not abuse its discretion when it

concluded on the facts of the instant case that Ms. Jones knew

that her termination discrimination claim was frivolous. See

Tonti v. Petropoulous, 656 F.2d 212 (6th Cir. 1981).

Contrary to the situation involved in Smith v.

Smythe-Cramer Co., 754 F.2d 180 (6th Cir. 1985),8 the

misconduct involved in the instant case -- the July 15, 1983

letter -- directly caused Ms. Jones' termination and exposed

the Company to liability under Title VII and § 1981. As far as

Ms. Jones' "perception" is concerned, she clearly believed that

she could use Title VII and § 1981 as a sword, not just a

shield, to force employer, co-worker and customer to conform to

Smith cites Price v. Pelka, 690 F .2d 98 (6th Cir. 1982)

and Carrion v. Yeshiva University, 535 F.2d 722 (2nd Cir.

1976), for the proposition that neither successful nor

unsuccessful plaintiffs should be subjected to attorneys'

fees where the misconduct involved would not affect the

ultimate issue- of defendant's liability or the plaintiff's

basis for believing that discrimination has occurred.

-14-

her wishes or face her wrath. The Smith case is simply

inapposite to this one.

The award of attorneys' fees against Ms. Jones on her

termination claim should be affirmed.

Ill .

Taxation of Costs

Against Ms. Jones

Was Appropriate

Wholly apart from its petition for attorneys' fees,

the Company filed a Bill of Costs which was never contested.9

The trial court, almost as an aside in its January 23, 1985

memorandum approved taxation of those undisputed costs against

Ms. Jones. Only afterwards, in her motion to alter or amend or

for new trial on the attorneys' fees awards, did she argue that

she should be excused from the obligation to pay costs because

of the financial inconvenience she would suffer.

In Delta Air Lines, Inc, v. August, 450 U.S. 345, 352

(1981), the Supreme Court commented:

"Because costs are usually assessed against the

losing party, liability for costs is a normal

incident of defeat."

Failure to make a timely motion for review of a Bill of

Costs should preclude any later collateral attack. See

McDowell v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 758 F.2d 1293, 1294 (8th

Cir. 1985).

-15-

The Christianburg "double standard," applicable to attorneys'

fees awards and relied upon by Ms. Jones in her brief, p. 24,

does not apply under Fed.R.Civ. P. 54(d) and 28 U.S.C. § 1920.

See Poe v. John Deere Co., 695 F.2d 1103 (8th Cir. 1982).

In Hudson v. Nabisco Brands, Inc., 758 F.2d 1237,

1244 (7th Cir. 1985), a plea was rejected to create a general

rule that "disparate wherewithal" alone could defeat a Rule

54(d) claim for costs. A presumption of entitlement to costs

exists. Coyne-Delaney Co., Inc, v. Capital Development Bd.,

717 F .2d 385 (7th Cir. 1983).10

Under the circumstances, the trial court's discretion

should be deferred to; and the costs taxed against Ms. Jones

should be affirmed.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons heretofore stated, the Company urges

this Court to affirm the trial court's decision, awarding it

attorneys' fees in the amount of $5,414.50 against counsel and

in the amount of $4,740.25 against Ms. Jones, while also

While the presumption may be overcome by evidence of

indigency, Badillo v. Central Steel & Wire Co., 717 F.2d

1160, 1165 (7th Cir. 1983) and Cross v. General Motors

Corp., 721 F.2d 1152, 1157 (8th Cir.), cert. denied 104

S.Ct. 2364 (1983)(partial award of costs in spite of

limited financial resources), it was within the instant

trial court's discretion, reviewing Ms. Jones' affidavit

and having previously determined her lack of credibility,

to conclude that she was not indigent.

16-

affirming taxation of costs in the amount of $6,540.15

against Ms. Jones.

Respectfully submitted,

KING & SPALDING

2500 Trust Company Tower

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 572-3373

,A~ v J\JU~

FARRIS, WARFIELD & KANADAY Cornelia A. Clark usitty.

Seventeenth Floor V--V

Third National Bank Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

(615) 244-5200

Attorneys for

Defendants/Appellees

OF COUNSEL:

Melvin S. Katzman

Assistant Vice President

& Labor Counsel

The Continental Corporation

180 Maiden Lane

New York, New York 10038

(212) 440-7665

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I served counsel for

plaint iff/appellant with two copies of defendants/appellees1

brief by depositing same in the United States Mail, postage

prepaid, and addressed to Richard H. Dinkins, Williams and

Dinkins, 203 Second Avenue, North, Nashville, Tennessee

37201.

This _/^/vday of Septembwer, 1985 .

/" //

- ‘ ̂ ■* J( „ l /

Attorney for

Defendants/Appe1lees

-17-

Ill jHiS ' ' i 3 ' si

§ n

~

iasSli

SSftfil■ . _ ■ . .