McFerren, Jr. v. County Board of Education of Fayette County, Tennessee Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 8, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McFerren, Jr. v. County Board of Education of Fayette County, Tennessee Brief for Appellants, 1974. 16288384-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a4c7a7a5-ab8e-4f1a-b16e-ed9aeb315968/mcferren-jr-v-county-board-of-education-of-fayette-county-tennessee-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

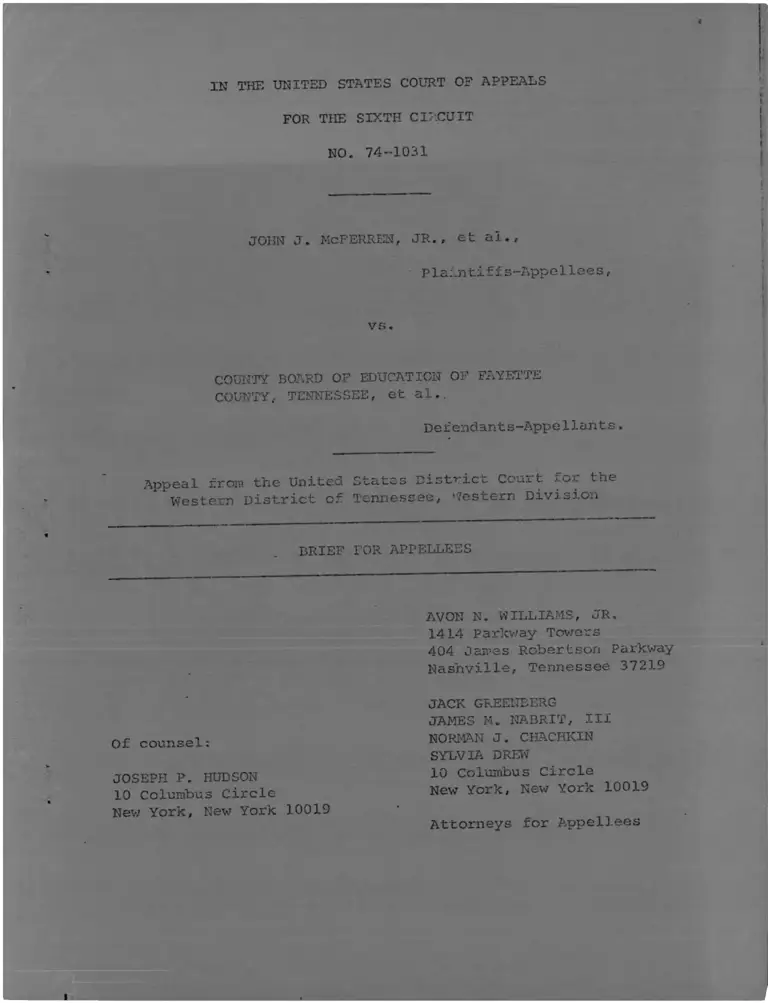

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-1031

JOHN J. McFERREN, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

vs.

COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION OF FAYETTE

COUNTY, TENNESSEE, et al..

Defendants-AppeHants.

Appeal from the United

Western District of

States District Court for the

Tennessee, Western Division

BRIEF.FOR APPELLEES

Of counsel:

JOSEPH P. HUDSON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellees

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities................................... ii

Issues Presented for Review .......................... 1

Statement ............................................ 2

ARGUMENT—

Introduction........... 6

I. The School Board Has Presented No

Reason for Overturning The District

Court's Disapproval Of Its Modified

Desegregation P l a n .......... . ............. 7

II. The District Court Did Not Abuse

Its Discretion By Requiring The

School Board To Use A Consultant . . . . . . . 15

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . .......... . . . . . . . . 16

Certificate of Service ................................ 17

l

Table of Authorities

Cases:

?ag.e.

Bell v. West Point Municipal Separate School

Dist., 446 F.2d 1362 (5th Cir. 1971) . . . . . . 13

Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 429

F.2d 382 (5th Cir. 1970) ...................... . 4n

Chambers v. Iredell County Bd. of -Educ., 423

F.2d 613 (4th Cir. 1970) ......................

Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 402

U.S. 33 (1971) . .......... . .................

Goss v. Board of Educ., 432 F.2d 1044 (6th Cir.

1973), cert, denied, 42 U.S.L.W. 3423 (Jan.

21, 1974) .................................. COir-•

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) . . . 8, 12

Hill v. Franklin County Bd. of Educ., 390 F.2d

583 (6th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ........................ . 8

Newburg Area Council, Inc. v. Board of Educ., 489

F.2d 925 (6th Cir. 1973) ....................

Northcross v. Board of Educ., 412 U.S. 427 (1973) . . 16

Northcross v. Board of Educ., 489 F.2d 15 (6th Cir.

1973), cert, denied, 42 U.S.L.W. 3595 (April

22, 1974) .................................

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 467 F.2d

1187' (6th Cir. 1972)........................

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 442 F.2d

255 (6th Cir. 1971) ........................ . 8

Rolfe v. County Bd. of Educ., 391 F.2d 77 (6th

Cir. 1968) ..................................

Seals v. Quarterly County Court of Madison

County, No. 73-1673 (6th Cir., April 23, 1974) . 4n

n

(cases)

Sloan v.

433

Swann v.

U.S

Statutes

Title I,

F.R. Civ

Rule 9,

Table of Authorities (continued)

Page

Tenth School Dist. of Wilson County,

F.2d 587 (6th Cir. 1970) . . ................ 10, 11

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

. 1 (1971) .............. .................. . 3, 5, 9, 11,

12, 16

and Rules:

ESEA, 20 U.S.C. §§241a et secu . . . . . . . . . 2

. P. 52 . . .............. 8

U.S. Court of Appeals, 6th Cir. . . . . . . . . 7

i n

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-1031

JOHN J. McFERREN, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

vs.

COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION OF FAYETTE

COUNTY, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Detendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

______ Western District of Tennessee, ifestern Division_____

■ BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Issues Presented for Review

1. Did the District Court err in disapproving defendant

school board's proposal to amend its desegregation plan, which

amendment the Court found would have caused the discriminatory

closing of a black school, and which would not have provided

for comprehensive desegregation of defendants' system?

2. Did the District Court abuse its discretion in direct

ing that the defendant school board consult with an outside

expert and either "present a plan that will more completely

desegregate the school system, or explain why further changes

on the existing plan are not required by the controlling auth

orities [Swann and Davis]"?

\

Statement

This school desegregation suit, originally commenced in

1965, appears before this Court for the second time. It was

previously he;:rd on cross-appeals by the school board and a

group of discharged black schoolteachers seeking their rein

statement. 4:55 F.2d 199 (6th Cir.) , cert. denied, 407 U.S. 934

(1972). It has resulted in numerous hearings before the District

Court with respect to pupil desegregation, the discharged teacher

1/issues, and ancillary matters.

As appellants' brief correctly notes, the last District

Court order approving a plan of pupil assignment for Fayette

County was entered September 23, 1970; at that time, in accord

ance with controlling precedent, a geographic-zoning plan was

substituted for an ineffective freedom-of-choice decree (199a).

After the school board on March 5, 1973 sought the District

Court's approval to place portable facilities at various sites,

in order to conduct a compensatory education program under Title

1/ . . .I, ESEA, and to undertake certain additional construction at

1/ See, e.q., 17a, 23a [citations are to the printed Appendix

on this appeal] (suspension of minor plaintiff) .

2/ 20 U.S.C. §§241a et seq..

-2-

the Braden and Jefferson schools,— the plaintiffs filed a

Motion for Further Relief (2a) which, as amended and supplemented

4/on June 21, 1973,“ alleged, inter alia, that the public schools

of Fayette County were not effectively desegregated (13a-16a).

The motion for further relief sought the adoption and implemen

tation of a new elementary school desegregation plan consistent

with Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1

(1971) and Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 402 U.S..

33 (1971) (19a-20a).

On August 3, 1973, the date of the hearing scheduled by

the District Court to consider the parties' motions, and some

few weeks prior to the start of the school term, the school

board for the first time proposed a new plan of elementary pupil

assignment for the Fayette Countv system (see 31a). Under this

plan, the traditionally black Bernard Elementary School would

be closed and its area added to a new, combined Jefferson-

Somerville zone; certain relatively minor zone changes at other

schools would be made; and the school board would proceed with

its construction plans at Jefferson and Braden schools (Brief

for Appellants, pp. 3-6).

3/ A line drawing of the county, showing the approximate loca

tions of the elementary school facilities, is found in the

separate Exhibit Appendix, at 3.

4/ On March 28, 1973, the District Court permitted the erection

of the temporary buildings for Title I purposes, but postponed

consideration of the school board's request to undertake permanent

construction at Braden and Jefferson (12a-13a).

-3-

The principal issue of concern to the parties and the

District Court was the board's sudden (see 86a-93a) request to

close the Bernard School, to which plaintiffs objected as

discriminatory and unnecessary (31a-33a). Defendants presented

5 /the testimony of a black man appointed to the school board-

two weeks before the court hearing (34a), and the testimony of

the school superintendent, in support of their request (34a-42a;

84a-115a). Both sought to establish that the deteriorated

6/physical condition of the Bernard School warranted its closing;

however, neither was able to compare the condition of the Bernard

facility with all other county schools (40a-41a; 70a-71a; l'16a;

. 1/124a; 144a). Both were subjected to detailed cross-examination

(42a-91a; 99a-105a; 116a-155a) by plaintiffs, who also intro

duced photographs of each school facility (81a—82a; 114a~115a)

as well as the testimony of other witnesses who had long famil

iarity with the county school system (158a-196a).

After hearing the proof, the District Court ruled that the

board's plan to close the Bernard School, transfer the black

5/ 46a; see Seals v. Quarterly County Court of Madison County,

No. 73-1673 (6th Cir., April 23, 1974), slip op. at 5.

6/ See, e.g., Chambers v. Iredell County Bd. of Educ., 423 F.2d

613 (4th Cir. 1970); Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ.,

429 F.2d 382 (5th Cir. 1970).

7/ Although appellants claim their proof with respect to the

_ condition of the Bernard School was "largely uncontroverted"

(Brief at 10), the testimony of their own witnesses was substan

tially weakened by their responses on cross-examination. For

example, the black school board member, who had no training or

expertise in construction or maintenance of buildings (68a),

[continued]-4-

a Jefferson-Somerville pair, and maintain the existing, 57%-w'nite

Braden school zone without change, except to enlarge the capacity

of the school in the face of white population growth in western

Fayette County (121a-122a), was racially discriminatory (202a-

2 04a) .

elementary students residing within the former Bernard zone to

8/

The Court reviewed the status of desegregation in Fayette

County in light of the commands of Swann and Davis (199a-202a),

and concluded that further desegregation of the elementary schools

was required (205a). The Court declined to adopt pairing pro

posals suggested by the plaintiffs (204a) but announced that it

would require the school board to employ a consultant and "come

up with a plan that will more completely desegregate the school

9/system . . . " (205a).

7/ [continued]

characterized Bernard as "rundown," "dangerous and hazardous,"

"broken from the bottom to the top" (40a-41a), and he sard the

roof of the building was "really sagging" like "a sway-back

horse" (70a). When shown a photograph of the school and asked

to point out this serious sagging, however, he replied: "It's

a peculiar thing what a camera can do for a building. . . (83a).

Shown another view, he contended it revealed sinking rafters (84a);

the photographs were studied by the District Court (ibid.). He

also admitted that he had made no inquiry of the system's main

tenance department to determine whether the building could be

repaired (69a), even though it was his view that repairing the

school, combining the Bernard and Braden zones, and pairing Jef

ferson and Somerville, would be a more effective and fairer

desegregation plan (85a-86a).

8/ The Fayette County system is between 80% and 85% black (110a,

204a).

9/ As previously noted, the Court's order required submission of

such a plan or an explanation why it was not required under law (26a).

— 5 —

Based upon the evidence, the District Court found also

that the school board's policy of neglecting maintenance at the

Bernard School (see 82a) left that facility in neeo. of repairs

(203a), and it directed that the school be restored to sound

condition in time for the opening of school (26a; 205a).

ARGUMENT

Introduction

On this appeal, the school board questions the District

Court's ruling in three particulars: disapproving the board's

request to amend its desegregation plan by closing Bernard Schcol

and making the other changes outlined; declining to permit the

board, on the evidence before the Court, to reconstruct a

portion of the Jefferson School and to expand the capacity of

the Braden School; and directing the board to obtain the services

of an outside consultant in preparing a new desegregation plan

for its elementary schools. Although the board's brief attempts

to separate the Jefferson—Somerville pairing, which it contends

would “improve" desegregation in the county, from the Bernard

School closing, it is clear that the entire package— including

the construction at Jefferson necessary to accommodate the

reassigned Bernard students and the expansion of Braden was

presented to the District Court as a unified proposal. The

District Court observed the witnesses, heard the evidence, and

(with his long familiarity with the Fayette County school system)

-6-

rejected the proposal:

But we do know that the total

combination of what the Board

approves would risk or would

build in further racial discrim

ination against black people in

this county. (206a)

On this record, the factual findings and legal rulings of

the District Court are clearly correct; and the Court did not

abuse its discretion in recjuiring the board to consult with an

outside expert to draft a new desegregation plan. The judgment

should be affirmed. indeed, we respectfully suggest that upon

study of the briefs, the ruling below should be upheld without

oral arcfument (see Rule 9, U.S. Court of Appeals, 6th Cir.) .

I

The School Board Has Presented

No Reason For Overturning The

District Court's Disapproval Of

Its Modified Desegregation Plan

Nothing in the Brief for Appellants supports reversal of

the district court's judgment in this matter. While we deal

below with the individual arguments of the school- board, we think

it proper, first, to sketch the context of this Court's review.

In the first place, the findings and judgment of the

District Court carry with them presumptions of correctness,

subject to reversal by this Court only if "clearly erroneous."

Goss v. Board of Educ., 482 F.2d 1044 (6th Cir. 1973), cert.

-7-

denied, 42 U.S.L.W. 3423 (Jan. 21, 1974); Robinson v. Shelby

County Bd. of Educ., 467 F.2d 1187 (6th Cir. 1972); Northcros3

v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 489 F.2d 15 (6th Cir. 1973), cert.

denied, 42 U.S.L.W. 3595 (April 22, 1974); F.R. Civ. P. 52; cf.

Newburg Area Council, Inc, v. Board of Educ., 489 F.2d 925 (6th

Cir. 1973). The "clearly erroneous" doctrine is particularly

appropriate in this case, since defendants' and plaintiffs' wit

nesses clashed on various factual matters, including the condition

and repairability of the Bernard School, and the burden placed

upon black students if it were closed.

Furthermore, the burden of proof was upon the school author

ities to justify their proposed modified desegregation plan, in

terms both of its effectiveness, Green v. County School Bd., 391

U.S. 430 (1968); Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 442 F.2d 255

(6th Cir. 1971), and of its fairness. In particular, a proposal

to close a black school as part of a desegregation plan places

a heavy burden upon school officials to show the absence of dis

criminatory motivation and impact. Brief for Appellants, at 10.

The principle is the same as that applied in teacher discharge

cases. E.g., McFerren v. County Bd. of Educ., supra; Hill v.

Franklin County Bd. of Educ., 390 F.2d 583 (6th Cir. 1968);

Rolfe v. County Bd. of Educ., 391 F.2d 77 (6th Cir. 1968).

These two principles combine to insulate the District Court's

judgment from reversal unless egregious error or misinterpretation

-8-

of the evidence is demonstrated. This the school board has failed

to do.

The board argues, first (Brief for Appellants, p. 9) that

the District Court's decision impinges upon school authorities'

need for "considerable flexibility in exercising their discretion

to locate and maintain public schools," and refers to the dis

cussion in Swann, 402 U.S., at 20-21. But the board distorts

the Supreme Court's meaning, for what the Court was emphasizing

in the passages to which reference is made was the vast potential

for racial, discrimination in site selection and construction

practices. Significantly, the Court commented:

. . In addition to the classic pattern

of building schools specifically intended

for Negro or white students, school

authorities have sometimes, since Brown,

closed schools which appeared likely to

become racially mixed through changes in

neighborhood residential patterns. This

was sometimes accompanied by building

new schools in the areas of white subur

ban expansion farthest from Negro popula

tion cen :ers in order to maintain the

separatian of the races with a minimum

departure from the formal principles of

"neighborhood zoning." . . . Upon a proper

showing a district court may consider this

in fashioning a remedy.

. . . In devising remedies where legally

imposed segregation has been established,

it is the responsibility of local auth

orities and district courts to see to it

that future school construction and

abandonment is not used and does not serve

to perpetuate or re-establish the dual

system. . . . (402 U.S., at 21.)(emphasis

supplied)

-9-

*

The Supreme Court's discussion is but a restatement of the

principles expressed by this Court in Sloan v. Tenth School Dlst.

of Wilson County, 433 F.2d 587, 589, 590 (6th Cir. 1970), affirming

a district court's retention of jurisdiction in order to supervise

future construction:

. . . Courts of Appeals have recognized the

possibility of the construction of new

schools and the expansion of existing facil

ities creating or preserving the racial

segregation of pupils in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment, as well as the possi

bility of a school board selecting sites

for new schools in order to effect an

incorporation of existing residential segre

gation into the school system. . . . school

construction planning [may be] designed to

reinforce trends in population growth

regardless of whether such planning rein force[s]

and extend ( s] residential racial segregation .

. . . (emphasis supplied)

The excerpts from both opinions describe the factual situ

ation before the District Court in this case: the school board

was proposing to close a black school in the northwest section

of the county, an area toward w’hich white population growth was

moving (109a, 122a, 126a). The black students residing within

the school's present attendance area would be included in a new

zone for two paired elementary schools to the east, with a

resulting pupil population 80% black (Exhibit App., at 5); to

the west of the present Bernard zone, the formerly white Braden

Elementary, now the "whitest" school in the county (203a), would

be unaffected by the reallocation of the Bernard zone. But in

the context of the system-wide proportions, maintenance of this

-10-

*

disproportionately white school, the district court found, would

not only "incorporate existing residential segregation" but would

attract additional white families to the area (204a), thus

"extend[ing] residential racial segregation" in the county.

Indeed, the evidence showed that this was the Superintendent's

expectation: the population growth in the Braden zone is mostly

white (109a); the Superintendent expected the increase in

population in that area to bring Braden to capacity this year

(ibid.) and to necessitate expansion of the facility (the construe

tion proposed in the board's plan) in the future (110a, 126a).

The record shows there are over 200 vacant spaces at

Jefferson (12.S<i) , permitting a general, realignment of the

Jefferson-Somerville-Bernard-Braden zone lines in an eastward

and southward direction, increasing desegregation at each facil

ity by adding black students to Somerville and white students to

Braden, and obviating the necessity for additional construction.

(See Exhibit App., at 3). Alternatively, plaintiffs' proposal

to pair Bernard and Braden, and Jefferson and Somerville, would

achieve these ends. The alternative selected by the school board

results in the greatest degree of continued segregation, based

upon existing and projected residential patterns. The District

Court was clearly authorized, indeed required, by Swann and Sloan

to reject it.

-11-

*

The board's argument (Brief for Appellants, at 10) that the

District Court was obligated to allow the Braden-Jefferson-Somer-

ville pairing because, viewed in isolation from the remainder of

the county, it would "increas[e]" desegregation, is untenable

in the light of the obligation to desegregate "root and branch,"

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) and to achieve

"the greatest possible degree of actual desegregation" throughout

the school system, Swann, supra; Davis, supra.

The school board next argues that the District Court's

conclusion that the proposal to close Bernard was if cX cially

discriminatory is clearly erroneous. None of the "overwhelming

(and largely uncontroverted) proof" is cited in the board's

argument (Brief for Appellants, at 10) .. In its Statement of

Facts, however, the board makes a serious misrepresentation,

consistent with its tactical defense of calling a black school

board member to dispel thoughts of racial motivation. Mr. Maclin

did not, as the board's brief (at 5) suggests, initiate the

proposal to close the Bernard School. That decision had been

made by the school board prior to his appointment (64a, 98a). At

the first board meeting following his appointment, under the

impression that Bernard School was definitely to be closed (64a,

67a), he did make the motion to assign the Bernard students to

the Jefferson-Somerville pair (41a-42a, 64a).

Furthermore, the record contains substantial evidence from

both Mr. Maclin and plaintiffs' witnesses, which the District

-12-

Court could properly have credited in determining that Bernard

was to- be .closed because of opposition from Braden white parents

who did not wish to send their children to Bernard if the schools

were paired (see 87a, 162a-165a). Bell v. West Point Municipal

Separate School Dist., 446 F.2d 1362 (5th Cir. 1971). The

District Court was not clearly erroneous in concluding that the

board's plan "is discriminatory in its overall purpose" (204a).

Likewise, the evidence with respect to the unrepairability

of the Bernard structure is not so one-sided as to make clearly

erroneous the District Court's finding that Bernard is not "a

hazardous school" (205a). The repair estimate cited in the

board's brief (at 11) was admitted over objection (101a-105a)

and the District Court specifically rejected its reliability as

an indication of the soundness of the Bernard structure (205a,

211a). None of the plaintiffs' witnesses (who were as qualified

in construction and maintenance of buildings as Mr. Maclin) felt

Bernard was ready to fall down, or suffered from anything except

the "benign neglect" of the Fayette County School Board over the

years (178a, 182a, 187a, 192a-193a).

Finally, the board argues (Brief, at 11) that there is no

support for a finding that closing Bernard and merging its zone

into a Jefferson-Somerville pair would put a disproportionate

busing burden on black children. The board cites school-to-

school distances, not the lengths of travel which would be

required of children living within the zones. When these are

-13-

considered, the pattern is very clear. The Superintendent

himself admitted that a single Braden-Bernard paired attendance

zone would be smaller than the Jefferson-Somerville zone (120a),

much less the Bernard-Jefferson-Somerville zone— although he

refused to estimate actual busing distances (121a). He later

reiterated that travel distances would be less in a Braden-Bernard

pairing (132aj and said that pairing Jefferson and Somerville

without the Bernard zone included would bring about more effec

tive desegregation (137a). The plaintiffs who reside in north

western Fayette County viewed the board's proposal as discriminatory

because of the extensive distance to Somerville, as compared to

Braden (182a, 186a-187a). The District Court1s finding that the

proposal was discriminatory cannot realistically be characterized

10/as clearly erroneous.

In summary, we repeat that the school board has totally

failed to demonstrate that the findings and conclusions of the

District Court were clearly erroneous and reversible. The

District Court has extensive familiarity with the long history

of racial discrimination in Fayette County; his efforts to insure

that blacks are not unfairly treated in the desegregation process

are commendable.

10/ The board also refers in passing (Brief for Appellants, at

11) to the "poor road conditions surrounding and leading to

Bernard School." The difference between the board's plan and a

Braden-Bernard pairing is merely that under the former, only

black students will use those roads, while under the latter both

black and white children will (177a).

-14-

II

' The District Court Diet Not

Abuse Its Discretion By Requiring

The School Board to Use A Consultant

The board's entire argument on this issue is contained

in a single sentence:

Defendants especially contend that the

imposition upon Defendants of the cost

and burden of hiring yet another expert

to come up with yet another plan for

desegregation is unwarranted and constitutes

an abuse of discretion. (Brief for Appel

lants, at 12).

To the contrary, the District Court demonstrated greater modesty

than plaintiffs believe was warranted under the circumstances.

The school board had defaulted in its obligation under Swann to

come up with an acceptable plan; instead, it proposed a discrim

inatory scheme whose total impact would have been to increase

desegregation slightly at three schools, leave unchanged the

composition of four schools, and reduce desegregation at three

schools (Brief for Appellants, at 6-7; 132a-140a). Plaintiffs

proposed contiguous pairings which would far more effectively

have desegregated the Fayette County elementary schools (see

132a-140a; Exhibit App. at 11). In its discretion, the District

Court declined to order implementation of the pairings "without

further study" (204a) and directed the board to undertake such

study with the assistance of a consultant. Surely this modest

directive was within the power of the District Court upon the

-15-

board's failure to produce an acceptable plan. See Swann,

supra, 402 U.S., at 24-25.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, the judgment of the

District Court should be affirmed; and, upon submission of

documentation with their Bill of Costs, reasonable attorneys'

fees as well as the costs of this appeal should be awarded to

the plaintiffs. Norihcross v. Board of Educ.. , 412 U.S. 427 (1973).

Respectfully submitted.

- i ; . ? / / Q F

•-C' ' ^

AVOW K. WILLIAMS, JR.

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Of counsel:

JOSEPH P. HUDSON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 100IS

Attorneys for Appellees

-16-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 8th day of May, 1974, I

served two copies of the Brief for Appellees in this cause upon

counsel for the appellants herein, by depositing same in the

United States mail, first class postage prepaid, addressed as

follows:

G. Wynn Smith, Jr., Esq.

Canada, Russell & Turner

1213 Union Planters Bank Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

i

-17-

r