Freeman v. Pitts Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

June 21, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Freeman v. Pitts Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1991. 5ce6d78a-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a4d0440b-697a-4920-97f4-52068c466f03/freeman-v-pitts-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

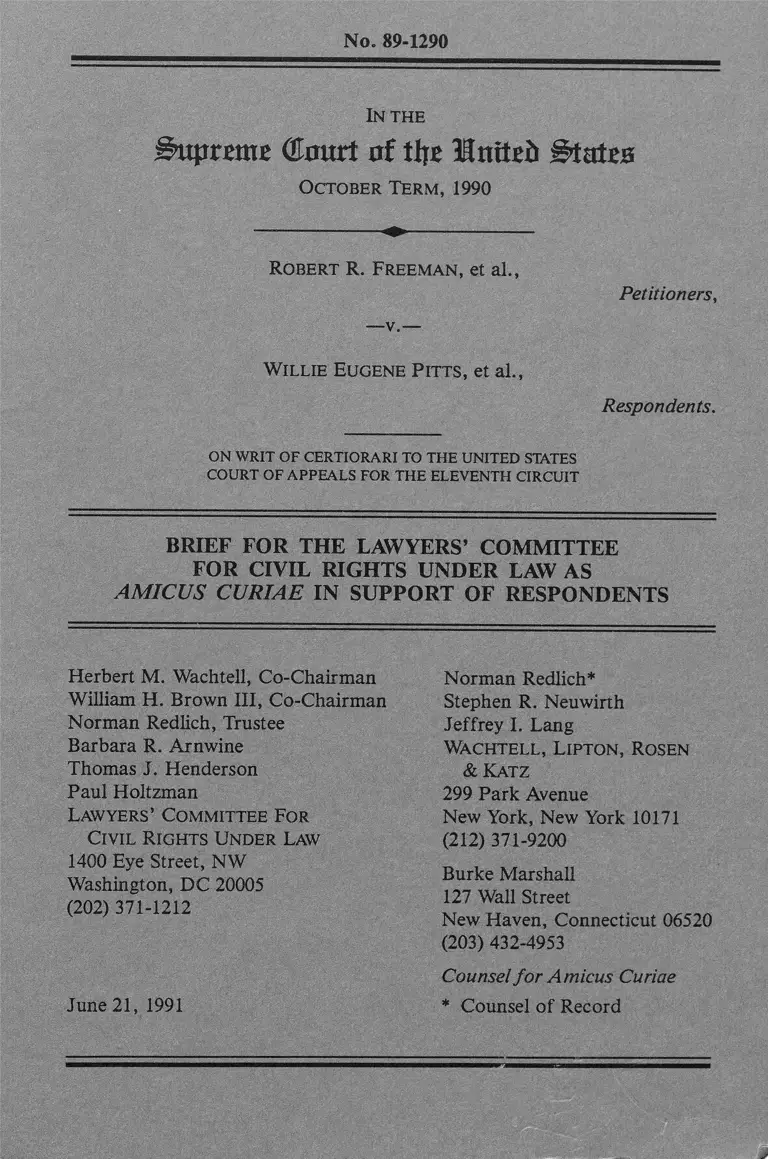

No. 89-1290

In the

Supreme Court of tlrr United & ttxtz&

October Term, 1990

Robert R. Freeman, et al.,

Petitioners,

Willie Eugene P itts, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS

A M IC U S CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Herbert M. Wachtell, Co-Chairman

William H. Brown III, Co-Chairman

Norman Redlich, Trustee

Barbara R. Arnwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Paul Holtzman

Lawyers’ Committee For

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, NW

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 371-1212

June 21, 1991

Norman Redlich*

Stephen R. Neuwirth

Jeffrey I. Lang

Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen

&Katz

299 Park Avenue

New York, New York 10171

(212)371-9200

Burke Marshall

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut 06520

(203) 432-4953

Counsel fo r Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

y

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........................................... iv

CONSENT OF PARTIES................................................. 1

INTEREST OF A M IC U S ................................................. 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUM ENT....................................... 2

ARGUMENT...................................................................... 6

I. THE AFFIRMATIVE OBLIGATION TO

ELIMINATE THE VESTIGES OF DE JURE

SEGREGATION AS FAR AS PRACTICA

BLE EXTENDS TO ALL ASPECTS OF A

SCHOOL SYSTEM, AND CANNOT BE

ACCOMPLISHED OR REVIEWED ON AN

INCREMENTAL BA SIS................................... 6

A. Incremental determinations of “ unitary”

status would be inconsistent with all prior

decisions of this Court................................. 7

1. Dowell set forth the workable stan

dards that do not allow an incremental

approach to determining when a school

system has achieved “ unitary” status . 7

2. This Court has consistently recognized

that the racial identification of schools

results from interrelated features of a

single system that cannot be isolated

from each other or subject to divisible

remedy....................................................... 9

11

PAGE

3. This C ourt’s decisions are in full

accord with the empirical findings of

educators and social scientists.............. 12

B. Incremental findings of unitary status

would frustrate the transition to unitary

school systems mandated by Brown and all

subsequent decisions of this C o u rt............

1. Incremental findings of unitary status

would allow vestiges of de jure segrega

tion to survive the termination of court

jurisdiction in a school d istrict............

2. Incremental unitary findings would

preclude future use of programs that

implicate several facets of the school

system ....................................................... 16

3. Incremental review of unitary status

would give rise to repeated and pro

tracted litigation......................... ........... 17

C. The vestiges of de jure segregation in

DeKalb County have had interrelated seg

regative effects, and cannot be considered

in iso lation ....................................... ............ 18

II. THE DEKALB COUNTY SCHOOL SYSTEM

REMAINS UNDER AN AFFIRMATIVE

DUTY TO REMEDY, TO THE EXTENT

PRACTICABLE, CURRENT RACIAL

IDENTIFIABILITY OF THE SYSTEM’S

SCHOOLS............................................................ 20

A. The demographic changes that have

occurred in DeKalb County cannot shield

the school authorities from responsibility

for remedying existing racial identity in the

school system—including in the area of

student assignments

14

14

22

m

B. Where a school board that has not com

pleted the transition to a unitary system is

not obligated to implement further affirm

ative remedial steps, school authorities,

when they do act, remain obligated to take

no action that would impede completion of

PAGE

the transition................................................... 28

CONCLUSION.................................................................. 30

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: p a g e

Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277 (8th Cir.), cert,

denied, 449 U.S. 826 (1980).....................................17, 27n*

Board o f Educ. o f Oklahoma City v. Dowell, ____

U.S. ____ , 111 S. Ct. 630 (1991)..............................passim

Bradley v. School Bd., 382 U.S. 103 (1965)................ 4, 10

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) ........................................................................2, 6, 1, 9

Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) .............................................................................2, 4, 9

Clark v. Board o f Educ., 705 F.2d 265 (8th Cir. 1983). 17

Columbus Bd. o f Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449

(1979)........................................ passim

Davis v. Board o f School Comm’rs, 402 U.S. 33

(1971)............................................................................. 4, 10

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd., I l l

F.2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1983)....................... 22

Davis v. School District, 309 F. Supp. 734 (E.D. Mich.

1970), a ff’d, 443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir.), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 913 (1971)....................................................... 27n*

Dayton Bd. o f Educ. v. Brinkman (Dayton II), 443

U.S. 526 (1979)........................................ passim

Evans v. Buchanan, 393 F. Supp. 428 (D. Del.), a ff’d,

423 U.S. 963 (1975)....................................................... 27n*

Green v. New Kent County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430

(1968)............................. passim

V

Hart v. Community School Bd., 383 F. Supp. 699

(E.D.N.Y. 1974), a ff’d, 512 F.2d 37 (2d Cir. 1975) . 27n*

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973)............... passim

Lee v. Macon County Bd. o f Educ., 616 F.2d 805 (5th

Cir. 1980)........................................................................ 22

Milliken v. Bradley {Milliken II), 433 U.S. 267 (1977) 28

Morgan v. Burke, 926 F.2d 86 (1st Cir. 1991)............ 18

Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d 313 (1st Cir. 1987).......... 18

N AACP v. Lansing Bd. o f Educ., 559 F.2d 1042 (6th

Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 997 (1977)................... 27n*

Pasadena Bd. o f Educ. v. Spangler, A ll U.S. 424

(1976)................................................................................ 12

Penick v. Columbus Bd. o f Educ., 429 F. Supp. 229

(S.D. Ohio 1977)............................................................ 24, 26

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965)................... 4, 9, 10, 15

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971)..................................................................passim

United States v. Board o f School Comm’rs, 573 F.2d

400 (7th Cir. 1978)........................................................ 27n*

United States v. Montgomery Bd. o f Educ., 395 U.S.

225 (1969).................................................................. 4, 10, 15

United States v. Scotland Neck Bd. o f Educ., 407 U.S.

484 (1972)........................................................................16, 29

United States v. Yonkers Bd. o f Educ., 624 F. Supp.

1276 (S.D.N.Y. 1985), a ff’d, 837 F.2d 1181 (2d Cir.

1987), cert, denied, 486 U.S. 1055 (1988).................. 27n*

PAGE

VI

Vaughns v. Board o f Educ., 758 F.2d 983 (4th Cir.

1985)............................. .................................................... 22

Wright v. Council o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) ...........................................................................15-16, 29

PAGE

Other Authorities:

Billingsley, et al., “ School Segregation and Residential

Segregation: A Social Science Statement,” in School

Desegregation: Past, Present, and Future (W.G.

Stephan & J.R. Feagin, eds.) (1980)................14n*, 25, 26

A. Bryk, V. Lee and J. Smith, “ High School Organi

zation and its Effects on Teachers and Students,” in

Choice and Control in American Education, Vol. I

(W.H. Clune and J.P. White, eds.) (1990)_______ 12-13

G. Forehand and M. Rogasta, “A Handbook for Inte

grated Schooling,” U.S. Dept, of Health, Education

and Welfare (1976)........................................................ 13, 14

W.D. Hawley, et al., Assessment o f Current Knowl

edge About the Effectiveness o f School Desegrega

tion Strategies, Vanderbilt University Study, Vol. I

(1981)......................... 14

W.D. Hawley, “ Equity and Quality in Education:

Characteristics of Effective Desegregated Schools,”

in Effective School Desegregation (W.D. Hawley,

ed.) (1981)......... 13

Hughes, Gordon and Hillman, Desegregating Ameri

ca’s Schools (1980) ......................................................... 13

G. Orfield, Must We Bus? Segregated Schools and

National Policy (1978)..................................................... 14n*

D. Pearce, Breaking Down Barriers: New Evidence on

the Impact o f Metropolitan School Desegregation on

Housing Patterns (1980) 27

S. Purkey and M. Smith, “ Effective Schools—A

Review,” 83(4) Elementary School Journal 440

(1983)................................................................................ 12

R. Scott and J. McPartland, “ Desegregation as

National Policy: Correlates of Racial Attitudes,” 19

Amer. Educ. Research J. 397 (1984)......................... 13

Sheehan, “A Study of Attitude Changes in Desegre

gated Intermediate Schools,” 53 Sociology o f Educa

tion 51 (1980)....................................... 13

Tauber, “ Housing, Schools, and Incremental Segrega

tive Effects,” 441 Annals o f the American Academy

o f Political and Social Science 157 (1979).................. \4n*

Tauber, Demographic Perspectives on Housing and

School Segregation, 21 Wayne L. Rev. 833 (1975).. 26

Tauber, “ School Desegregation and Racial Housing

Patterns” in New Directions fo r Testing and Mea

surement: Impact o f Desegregation (D. Monti, ed.)

(1982).............................................„................................. 27

Taylor, Brown, Equal Protection and the Isolation o f

the Poor, 95 Yale L.J. 1700 (1986)........................... 27

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Racial Isolation in

the Public Schools (1967)............................................. 13

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Fulfilling the Letter

and Spirit o f the Law: Desegregation o f the Nation’s

Public Schools (1976)................. ................................... 14n*

vii

PAGE

In t h e

BuprEme (Emtrt nf tljB lEnteii Btates

October Term, 1990

No. 89-1290

Robert R. Freeman, et al.,

Petitioners,

Willie Eugene Pitts, et al.,

Respondents.

on writ of certiorari to the united states

court of appeals for the eleventh circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS

A M IC U S CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

CONSENT OF PARTIES

Petitioners and respondents have consented to the filing of

this brief, and their letters of consent are being filed sepa

rately herewith.

INTEREST OF AMICUS

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

(“ Lawyers’ Committee” ) was established in 1963 at the

request of President Kennedy to help assure civil rights to all

Americans by affording legal services otherwise unavailable

to minorities and the poor pursuing claims for equal treat-

2

ment under the law. The Lawyers’ Committee is a non-profit

private corporation that has enlisted the services of thousands

of members of the private bar in cases involving voting, edu

cation (including school desegregation), employment, hous

ing, municipal services, the administration of justice and law

enforcement.

The Lawyers’ Committee has a long history of direct sup

port of and participation in cases in the federal courts fur

thering school desegregation. This Court’s decision will

undoubtedly have significant implications in other school

desegregation cases. Amicus submits that its experience in

school desegregation litigation enables it to provide a perspec

tive different from the parties and other amici on the issues

before this Court.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The DeKalb County public schools were segregated in

1954. They were segregated in 1969, when this case began,

and they remain segregated today. At no time has petitioner

school board fulfilled the obligation imposed on it by Brown

v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), 349 U.S. 294

(1955), and Green v. New Kent County School Bd., 391 U.S.

430 (1968), to achieve a unitary school system. Contrary to

what it would have this Court believe now, it is not operating

a school system overwhelmed by demographic changes that

frustrated its efforts to achieve “ a unitary system in which

racial discrimination would be eliminated root and branch.”

Swann v. Charlotte-Mec/clenburg Bd. o f Educ., 402 U.S. 1,

15 (1971). It made no such efforts. To the contrary, as the

Court below said (887 F.2d at 1440-41):

Despite our [previous] admonishments [in this case], the

district court ruled that the DeKalb County School

Board (“ DCSS”) is under no affirmative duty to take

steps to desegregate an acknowledged segregated system

in the area of student assignment because the DCSS

closed all of its de jure black schools in 1969,

* * * *

3

Black students constitute 47 percent of the DCSS popu

lation. Despite the system’s racial balance, 50 percent of

the black students attend schools with black populations

of more than 90 percent. Similarly, 27 percent of the

DCSS’s white students attend schools with white popula

tions of more than 90 percent. The DCSS operates a

segregated school system.

Under these circumstances the district court was plainly

wrong, under the decisions of this Court, in denying any fur

ther relief to plaintiffs except in the limited area of faculty

reassignments, and in refusing further supervision of the

school board other than in that regard. The Court below

accordingly was plainly right in reversing the district court

and requiring it to see to it that the school board continue to

take all practicable steps to achieve a unitary system. As this

Court recently said, the inquiry was properly directed to the

question “ whether [the school board has] complied in good

faith with the desegregation decree since it was entered,”

which it clearly has not, and “ whether the vestiges of past

discrimination [have] been eliminated to the extent practica

ble,” which certainly has not happened. See Board o f Educ.

o f Oklahoma City v. Dowell, ____ U.S. ____ , 111 S. Ct.

630, 638 (1991).

Petitioner seeks to avoid the force of the application of

these principles in two ways. The first, as the Court below

noted, is by reliance on its action of closing the black schools

of its dual system in 1969, thus taking a preliminary step

towards the elimination of racial student assignments. In this

way petitioners persuaded the district court to treat the mat

ter of student assignments as a closed book that could not be

reopened despite the overwhelming evidence of racial segrega

tion in the system, and despite petitioner’s admitted failure to

eliminate the vestiges of de jure segregation in other facets of

school operations, such as faculty, staff, and facilities. See

Green v. New Kent County School Bd., supra, 391 U.S. at

435; Board o f Educ. o f Oklahoma City v. Dowell, supra, 111

S. Ct. at 638. Secondly, petitioner relies on the evidence of

concededly large population moves into the county in the

4

past decade and a half, causing significant changes in the size

and racial composition of the school population.

Neither of these factors should be held to excuse petitioner

from its well-established duty to eliminate vestiges of de jure

racial segregation and achieve a unitary system in which

racial discrimination is eliminated root and branch.

With regard to the first point, the decisions of this Court

since Green, supra, have consistently required school boards

and supervising district courts to treat the task of eliminating

the vestiges of racial discrimination in terms of the entire

school system rather than its component parts. De jure segre

gation is a system-wide constitutional violation. The remedy

requires examining and treating all aspects of the school sys

tem as one problem, needful of coordinated attention. See

Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown

II); Green, supra; Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f

Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971). See also Davis v. Board o f School

Comm’rs, 402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971); Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S.

198 (1965); Bradley v. School Bd., 382 U.S. 103, 105 (1965);

United States v. Montgomery Bd. o f Educ., 395 U.S. 225,

231 (1969). Thus in Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S.

189 (1973), the Court expressly applied a presumption that

discriminatory action in a particular aspect of the system

would necessarily spread to and affect other components of

the system. Id., 413 U.S. at 196, 201-2, 214. See also Dayton

Bd. o f Educ. v. Brinkman (Dayton II), 443 U.S. 526 (1979);

Columbus Bd. o f Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 467 (1979).

The system approach was reiterated in Dowell this year. See

Dowell, supra, 111 S. Ct. at 636, 638. Here petitioner’s fail

ure to deal with its whole system in a unitary fashion is

admitted. See Point I, infra.

Wholly apart from this Court’s repeated insistence on

system-wide analysis and treatment, the incremental approach

urged by petitioner and embraced by the district court will

not work in practice. Achievement of a unitary system means

elimination, to the extent practicable, of racially identifiable

schools. It is common experience that racial segregation in

faculty and staff, such as that petitioner has permitted to per

sist in this case, along with disparities in facilities and

resources, contributes to the perception of schools as

5

“ black” or “ white.” Thus, the need for system orientation,

rather than an incremental, piece-by-piece approach, is recog

nized and endorsed by the extensive literature on school

desegregation. See Point I, infra.

The extensive demographic changes that have taken place

in DeKalb County since the entry of the judgment in this case

in 1969 do not diminish the legal and constitutional obliga

tions of petitioner. The school authorities did not cause the

onrushing tide of people into DeKalb County. But during this

period of influx the schools remained racially identifiable

because of the decisions of the DeKalb County school board

which never eliminated faculty and staff segregation and,

notwithstanding purportedly racially neutral student assign

ment practices in 1969 and 1970, assigned black students pre

dominantly to those schools where black faculty and staff

were located. Given that “ people gravitate toward schools,”

as this Court has recognized, the school authorities cannot

walk away from their responsibility for the persistence of

racially identifiable schools whose racial stamp encouraged,

and was reinforced by, the diversion of the flow of people

into two streams—white and black. See Point II, infra.

Petitioner thus remains responsible for taking all practica

ble steps to remedy existing racial identification of the

DeKalb County schools-—including in the area of student

assignments—until all vestiges of de jure segregation have

been eradicated. Throughout the transition to a unitary sys

tem, the DeKalb County school board is also obligated to

take no action, with respect to any aspect of the school sys

tem, that would impede the completion of the transition. The

Court below correctly left the question of exactly what steps

are necessary to eliminate completely the dual system to the

school board itself, and, in the event of default by school

authorities in that responsibility, to the discretion of the dis

trict court. See Point II, infra.

6

ARGUMENT

I

THE AFFIRMATIVE OBLIGATION TO ELIMINATE

THE VESTIGES OF DE JURE SEGREGATION AS FAR

AS PRACTICABLE EXTENDS TO ALL ASPECTS OF A

SCHOOL SYSTEM, AND CANNOT BE ACCOMPLISHED

OR REVIEWED ON AN INCREMENTAL BASIS

Since Brown v. Board o f Education, this Court has consist

ently reaffirmed the affirmative duty of school boards to

complete the transition from a de jure segregated school sys

tem to a system in which the vestiges of past discrimination

have been eliminated to the extent practicable. This Court

has recognized that various discriminatory acts or omissions

in a single school system have interrelated effects that cause

and perpetuate the vestiges of de jure segregation, including

racially identifiable schools, and that discrimination in one

particular component of the system cannot be considered in

isolation. Thus the Court has consistently applied system-

wide remedies to address the system-wide nature of the con

stitutional violation. This Court’s decision in Board o f Educ.

o f Oklahoma City v. Dowell reiterated these principles and

set forth the workable standards for determining when a for

merly de jure segregated school system has been brought into

compliance with the Constitution—and thus when court juris

diction in a desegregation case can properly be withdrawn.

As demonstrated below, however, incremental findings of

“ unitary” status—and with them incremental terminations of

court authority to impose remedies addressing particular

facets of a school system—would effectively preclude the type

of review of school systems, and of “ every facet of school

operations,” mandated by Dowell and the prior decisions of

this Court. Such incremental “ unitary” findings would

require district courts, based on the implementation by a

school board of particular non-discriminatory practices, to

sequentially “ carve out” discrete areas of the school system

from further judicial consideration—notwithstanding that

7

central vestiges of discrimination affecting those discrete

areas, including the racial identity of schools, had never been

remedied. Such incremental reviews of unitary status would

certainly inhibit the ability of district courts to determine, as

Dowell now requires, whether at a given point in time all ves

tiges of past discrimination have been eliminated from the

school system to the extent practicable.

Incremental reviews of “ unitary” status also would inevita

bly prove unworkable in practice. Such reviews would require

district courts to treat in isolation facets of school systems

that are, as educators and social scientists have recognized,

integrally related in fact. Such findings could also preclude

the use of such remedies as magnet schools or majority-to-

minority transfer programs that necessarily require court con

sideration of various facets of the school system—facets that

may already have been “ carved out” from the remedial

power of the district court by an earlier finding of “ unitari

ness.” Moreover, the opportunity for such incremental find

ings can only be expected to give rise to repeated and

protracted litigations, as school boards continually seek to

narrow the scope of district court review even before the

transition to a “ unitary” system has been completed.

This Court should instead reaffirm the principles articu

lated in Brown and all subsequent cases: only the transition

to a racially nondiscriminatory school system can cure the

constitutional violation of de jure segregation and justify the

removal of judicial jurisdiction over the school district.

A. Incremental determinations of “ unitary” status would be

inconsistent with all prior decisions of this Court.

1. Dowell set forth the workable standards that do not

allow an incremental approach to determining when a

school system has achieved “ unitary” status.

In Board o f Educ. o f Oklahoma City v. Dowell, ____U.S.

____ , 111 S. Ct. 630 (1991), this Court reiterated that a

school desegregation decree can be dissolved only when a

school board has “ made a sufficient showing” that “ a school

system . . . has been brought into compliance with the com

mand of the Constitution.” Id., I l l S. Ct. at 636, 638. This

8

Court set forth the inquiry necessary to determine whether

such compliance has been achieved: district courts should

consider “ whether [a school board has] complied in good

faith with the desegregation decree since it was entered, and

whether the vestiges of past discrimination [have] been elimi

nated to the extent practicable.” Id. at 638.

This Court then explained in plain terms the standard for

determining whether the vestiges of de jure segregation have

in fact been eliminated as far as practicable. Reiterating that

every facet of the school system must be free from those ves

tiges, this Court instructed that:

the District Court should look not only at student

assignments, but “ to every facet of school operations—

faculty, staff, transportation, extra-curricular activities

and facilities.” Green, 391 U.S., at 435, 88 S. Ct., at

1693. See also Swann, 402 U.S., at 18, 91 S. Ct., at

1277 (“ [E]xisting policy and practice with regard to fac

ulty, staff, transportation, extra-curricular activities, and

facilities” are “ among the most important indicia of a

segregated system”).

Id. at 638.

Dowell thus embodies fundamental tenets, articulated in

Green, Swann and the other precedents of this Court, requir

ing a school board to demonstrate that the school “system

. . . has been brought into compliance with . . . the

Constitution” —consistent with the constitutional mandate

that all vestiges of the de jure system be eliminated to the

extent practicable. This constitutional mandate would be seri

ously undermined if district courts were incrementally denied

the power, with regard to particular facets of the school sys

tem, to consider appropriate and practicable remedies to

ensure a complete transition to a unitary system in which

racial discrimination would be eliminated root and branch.

9

2. This Court has consistently recognized that the racial

identification of schools results from interrelated fea

tures of a single system that cannot be isolated from

each other or subject to divisible remedy.

The constitutional violation addressed in Brown, as in all

subsequent cases through Dowell, was the operation of

racially segregated systems, and not merely the existence of

particular discriminatory policies in discrete areas. This Court

thus anticipated systemic, rather than incremental, remedies:

district courts were instructed to apply remedies that “ may

call for elimination of a variety of obstacles in making the

transition to school systems operated in accordance with the

constitutional principles set forth in [Brown / ] .” Brown v.

Board o f Education {Brown IT), 349 U.S. 294, 300 (1955).

Green v. New Kent County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430

(1968), reiterated in unambiguous terms that the constitu

tional violation of de jure segregation is system-wide and that

even a facially non-discriminatory student assignment plan

can be rendered ineffective by vestiges of de jure segregation

in other facets of the system. The “Green factors” reflect

how in de jure segregated systems, “ [rjacial identification of

the system’s schools was complete, extending not just to the

composition of student bodies at the . . . schools but to

every facet of school operations—faculty, staff, transporta

tion, extracurricular activities and facilities.” Green, 391 U.S.

at 435. In Green, the New Kent County school board’s sole

reliance on a student assignment plan thus “ ignored the

thrust of Brown i r ' by failing to address the school system

as an integrated whole. In remanding Green, the Supreme

Court expressly instructed the district court to consider, for

example, student assignments “ in light of considerations

respecting other aspects of the school system such as the mat

ter of faculty and staff desegregation.” Id. at 442 n.6.

This consideration of school systems, rather than an incre

mental focus on discrete aspects of a school district, reflected

earlier Court decisions that had recognized the interrelated

effects of discrimination in such discrete areas as faculty and

student assignments. In Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965)

(per curiam), for example, the Court held that students have

10

standing to challenge discriminatory faculty assignments not

only because “ racial allocation of faculty denies [students]

equality of educational opportunity,” but also because a seg

regated faculty can “renderf ] inadequate an otherwise consti

tutional pupil desegregation plan.” Id. at 200 (emphasis

added). Similarly, in Bradley v. School Bd., 382 U.S. 103,

105 (1965) (per curiam), the Court recognized “ the relation

between faculty allocation on an alleged racial basis and the

adequacy of the desegregation plans.” See also United States

v. Montgomery Bd. o f Educ., 395 U.S. 225, 231-32 (1969)

(desegregation of faculty and staff is “ a goal that we have

recognized to be an important aspect of the basic task of

achieving a public school system wholly free from racial dis

crimination” ) (emphasis added). Indeed, in Davis v. Board o f

School Comm’rs, 402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971), this Court reiter

ated the general principle that it constitutes reversible error to

treat particular areas of a school district “ in isolation from

the rest of the school system.”

In light of the system-wide nature of the constitutional vio

lation, this Court since Green has consistently approved

system-wide, rather than incremental, remedies to achieve the

mandates of the Fourteenth Amendment. District courts have

“ not merely the power but the duty to render a decree which

will so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory effects of

past as well as bar like discrimination in the future,” Green,

391 U.S. at 438 n.4. This Court has reiterated that the inter

action among, and the combined effect of, discrimination in

various components of a school system causes and can per

petuate the vestiges of de jure segregation.

Swann, emphasizing a district court’s “ broad power to

fashion a remedy that will assure a unitary school system,”

thus explained that the quality of school buildings and equip

ment, or the organization of sports activities, for example,

can contribute to a school’s racial identification—

notwithstanding non-discriminatory student assignment prac

tices. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f Educ., 402

U.S. 1, 16 (1971) (emphasis added). In particular, the failure

to integrate faculty and staff will normally perpetuate such

racial identity: “ [independent of student assignment, where

it is possible to identify a ‘white school’ or a ‘Negro school’

11

simply by reference to the racial composition of teachers and

staff . . . a prima facie case of violation of substantive con

stitutional rights under the Equal Protection Clause is

shown.” Id. at 18.

Keyes similarly highlighted the extent to which the various

facets of a school system must be evaluated together to deter

mine whether the school district has fulfilled its affirmative

constitutional obligation. As the Court explained, “ [i]n addi

tion to the racial and ethnic composition of a school’s stu

dent body, other factors, such as the racial and ethnic

composition o f faculty and sta ff and the community and

administration attitudes toward the school, must be taken

into consideration.’’'' Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S.

189, 196 (1973) (emphasis added). The Court in Keyes recog

nized the interrelationship of the various “Green factors” in

perpetuating the unconstitutional racial identification of

schools: “the use o f mobile classrooms, the drafting o f stu

dent transfer policies, the transportation o f students, and the

assignment o f faculty and staff, on racially identifiable bases,

have the clear effect o f earmarking schools according to their

racial composition.” Id. at 201-02 (emphasis added). On

remand, the school board in Denver District No. 1 thus bore

the burden of showing that school board actions affecting

various aspects of the school system, “considered together,”

were “ not factors in causing the existing condition of segre

gation in these schools. Id. at 214 (emphasis added).

Similarly, in Dayton, the school board had failed to rem

edy the segregated school system by allowing the interplay of

various facets of the district—including faculty assignment,

attendance zones, school construction and grade structure—

to perpetuate the racial identity of the schools. See Dayton

Bd. o f Educ. v. Brinkman (.Dayton II), 443 U.S. 526 (1979).

This Court placed particular emphasis on the Dayton school

board’s failure to integrate faculty and staff: the district

court had erroneously “ ignored . . . the significance of pur

poseful segregation in faculty assignments in establishing the

existence of a dual school system.” Id. at 536 (citation omit

ted). Explaining that such “ purposeful segregation of faculty

by race was inextricably tied to racially motivated student

assignment practices,” this Court remained unwilling to

12

“ deprecate the relevance of segregated faculty assignments as

one of the factors in proving the existence of a school system

that is dual for teachers and students.” Id. at 536 & n.9

(emphasis in original). See also Columbus Bd. o f Educ. v.

Penick, supra, 443 U.S. at 467 (1979) (“ [t]he practice of

assigning black teachers and administrators only or in large

majority to black schools . . . served as discriminatory,

system-wide racial identification of schools” ).

This Court’s decisions have thus consistently required that

the system—and not isolated, discrete parts—be rid of the

vestiges of de jure segregation and its perpetuation. Nothing

in the Court’s decision in Spangler suggests or should allow a

different result. See Pasadena Bd. o f Educ. v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 (1976). There, this Court considered whether a dis

trict court properly refused to modify a desegregation decree

which provided that, in perpetuity, no Pasadena school could

have “ a majority of any minority” students; this Court con

cluded that the district court “ exceeded its authority” by

“ enforcing its order so as to require annual readjustment of

attendance zones.” Id. at 432, 435. That decision, however,

did not bar the district court from continuing to provide

appropriate and practicable remedies necessary to complete

the constitutionally mandated transition to a unitary system.

Indeed, to the extent this Court even considered the issue, it

observed that “ an injunction often requires continuing super

vision by the issuing court and always a continuing willing

ness to apply its powers and processes on behalf of the party

who obtained equitable relief.” Id. at 437 (quotation omit

ted).

3. This Court’s decisions are in full accord with the

empirical findings of educators and social scientists.

Rejecting the “ view that schools are relatively static con

structs of discrete variables,” education specialists have gen

erally recognized that schools are “ dynamic social systems

made up of interrelated factors.” S. Purkey and M. Smith,

“ Effective Schools—A Review,” 83(4) Elementary School

Journal 440 (1983). See also A. Bryk, V. Lee and J. Smith,

“ High School Organization and its Effects on Teachers and

13

Students,” in Choice and Control in American Education,

Vol. I (W.H. Clune and J.P. White, eds.) 139 (1990). Thus,

effective desegregation has required a system-oriented, rather

than incremental, approach. As one educator has observed:

Too often schools seem to focus on only one goal or

strategy to achieve effective desegregation. It seems

important to stress the need to develop comprehensive

plans and strategies. Generally speaking, the attainment

of one goal will enhance the possibilities of achieving

another.

W.D. Hawley, “ Equity and Quality in Education: Character

istics of Effective Desegregated Schools,” in Effective School

Desegregation 298-99 (W.D. Hawley, ed.) (1981).

Studies have consistently shown that student assignments

alone do not eliminate the racial identity of schools, and that

effective (or ineffective) desegregation results from the inter

play of such student assignments with other factors. See,

e.g., G. Forehand and M. Rogasta, “A Handbook for Inte

grated Schooling,” U.S. Dept, of Health, Education and

Welfare 11-12 (1976) (desegregation is a multi-dimensional

process affected by the various facets of the system). See also

Sheehan, “A Study of Attitude Changes in Desegregated

Intermediate Schools,” 53 Sociology o f Education 51-59

(1980); R. Scott and J. McPartland, “ Desegregation as

National Policy: Correlates of Racial Attitudes,” 19 Amer.

Educ. Research J. 397-414 (1984); Hughes, Gordon and Hill

man, Desegregating America’s Schools (1980) (noting various

measures of inequality within schools that must be reviewed

to develop an effective desegregation plan).

Among other things, educators and social scientists alike

have concluded that faculty and staff integration are essential

components of effective school desegregation. After studying

school districts in various cities, the United States Commis

sion for Civil Rights concluded in 1967 that the maintenance

of faculty and staff segregation perpetuates schools’ racial

identifiability. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Racial Iso

lation in the Public Schools 61 (1967) (“ [t]he racial identity

of Southern schools is maintained in a variety of ways”

14

including “ continued segregation of teaching staff” ).* A

1976 report prepared by the Education Testing Service for the

Department of Health, Education and Welfare similarly con

sidered the inclusion of racial minorities on faculty and

administrative staffs to be “ perhaps . . . our most important

recommendation.” See G. Forehand and M. Ragosta, “A

Handbook for Integrated Schooling,” supra, at 11-12. See

also W.D. Hawley, et al., Assessment o f Current Knowledge

About the Effectiveness o f School Desegregation Strategies,

Vanderbilt University Study (Vol. I) 86 (1981).

B. Incremental findings of unitary status would frustrate the

transition to unitary school systems mandated by Brown

and all subsequent decisions of this Court.

1. Incremental findings of unitary status would allow

vestiges of de jure segregation to survive the termina

tion of court jurisdiction in a school district.

Because incremental reviews of unitary status focus only on

whether isolated discriminatory practices have been elimi

nated from a particular facet of the school system during

some period of time, such incremental inquiries by definition

disregard those vestiges of de jure segregation-including, in

particular, the racial identification of schools—that result

from the interrelated effects of the various forms of discrimi

nation in the school system. Where such incremental findings

* The Civil Rights Commission later reiterated that “ [ajdequate

minority representation on the school staff is critical to integrated educa

tion .” Fulfilling the Letter and Spirit o f the Law: Desegregation o f the

Nation’s Public Schools 122 (1976). See also Tauber, “ Housing, Schools,

and Incremental Segregative Effects,” 441 Annals o f the American Academy

o f Political and Social Science 157-67 (1979) (manipulation of student assign

ment process, “ combined with segregative assignment of teachers, have com

bined to cause, enhance, and maintain racial identifiability of schools . . . in

Milwaukee” ); G. Orfield, Must We Bus? Segregated Schools and National

Policy 369 (1978) (in Cleveland, “ [t]he racial identity of the schools was rein

forced by intense faculty segregation” ); Billingsley, et al., “ School Segrega

tion and Residential Segregation: A Social Science Statement,” in School

Desegregation: Past, Present, and Future 235-36 (W.G. Stephan & J.R.

Feagin, eds.) (1980).

15

are permitted, school boards can sequentially demonstrate

that particular discriminatory practices affecting particular

facets of the school system have been eliminated, while ves

tiges of de jure segregation—particularly the racial identifica

tion of schools—continue to operate. If particular

discriminatory practices are considered incrementally and in

isolation, the sum of the parts of the system will be less than

the constitutionally mandated whole—a school system

cleansed of the vestiges of de jure segregation.

This means, in turn, that after a particular facet of the

school system would be “ carved out” from further judicial

review based on the implementation of particular non-

discriminatory practices, vestiges of de jure segregation could

continue to operate so that even those non-discriminatory

practices could soon be rendered ineffective. This is precisely

what this Court has always sought to avoid, as this Court has

recognized that the continuing vestiges of prior discrimination

in such areas as faculty assignments and funding can render

even non-discriminatory student assignment policies inade

quate to remedy violations of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Green, supra, 431 U.S. at 439-42. See also Rogers v. Paul,

supra, 398 U.S. at 200 (segregated faculty can “ render[ ]

inadequate an otherwise constitutional pupil desegregation

plan” ); United States v. Montgomery Bd. o f Educ., supra,

395 U.S. at 231.

At the same time, if particular facets of the school system

were to be carved out from further judicial consideration, a

school board could presumably become free to take actions

in those discrete areas that actually have the effect of imped

ing the transition to a unitary system—so long as these

actions do not otherwise constitute new violations of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Cf. Dowell, 111 S. Ct. at 638 (if the

Oklahoma City School board achieved unitary status in the

city school system, further school board actions would be

judged under “ appropriate equal protection principles” ).

Such a result would plainly impede the constitutionally man

dated transition to a system in which vestiges of de jure seg

regation have been eliminated to the extent practicable. It

would also disregard that “ [p]art of the affirmative duty

imposed by [this Court’s] cases, as . . . decided in Wright v.

16

Council o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972), is the obligation

not to take any action that would impede the process of dis

establishing the dual system and its effects.” See Dayton,

supra, 443 U.S. at 538. See also United States v. Scotland

Neck Bd. ofE duc., 407 U.S. 484 (1972); Columbus, 443 U.S.

at 460; Swann, 402 U.S. at 20-21.

Ultimately, this would mean that at whatever point in time

a school board will have finally succeeded in obtaining

sequential “ unitary” findings for all facets of the school sys

tem, remaining vestiges of de jure segregation may already

have operated to re-establish segregation in those areas where

incremental unitary findings have been made. At this point, it

would become virtually impossible to conduct any meaningful

inquiry as to whether the school board had in fact taken all

practicable steps to eliminate all vestiges of prior

discrimination—the very inquiry Dowell prescribed.

2. Incremental unitary findings would preclude future

use of programs that implicate several facets of the

school system.

In many cases, incremental findings of unitary status

would also preclude the use of remedies, such as optional

transfer programs and magnet schools, that would otherwise

be the most practicable means of completing the transition to

a school system in which the vestiges of de jure segregation

have been eliminated.

Remedies such as optional majority-to-minority transfer

programs have “ long been recognized as a useful part of

every desegregation plan.” See Swann, 402 U.S. at 26. Such

plans allow members of the majority racial group of a partic

ular school to transfer to other schools where they will be in

the minority. While this Court has explained that transfer

provisions are “ an indispensable remedy for those students

willing to transfer . . . in order to lessen the impact on them

of the state-imposed stigma of segregation,” Swann, 404

U.S. at 26, such optional transfer plans—that require adjust

ment of student assignments, faculty assignments, transporta

tion, or the allocation of school resources—would be

17

precluded in any district where any of those implicated facets

of the school system had already been declared “ unitary” .

A similar result would follow in the case of magnet school

programs, which draw students with particular qualifications

from throughout the district to a particular school. See Clark

v. Board o f Educ., 705 F.2d 265, 272 (8th Cir. 1983) (direct

ing establishment of magnet schools to promote “ equal edu

cational opportunity” ); Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d

1277, 1296-97 (8th Cir. 1980) (endorsing magnet schools as a

“ techniquef ] to ensure students . . . will receive equal edu

cational opportunities” ). Implementation of magnet school

plans plainly implicates the allocation of school resources,

student assignments, faculty assignments, and, in some cases,

transportation. The use of such magnet school remedies,

however, would be precluded where any of those facets of

the school system had already been “carved out” from fur

ther judicial consideration.*

3. Incremental review7 of unitary status would give rise

to repeated and protracted litigation.

In a regime allowing incremental “ unitary” findings, dis

trict courts could remove from further judicial consideration

particular facets of the educational system, notwithstanding

that the school system has not yet been brought into compli

ance with the Constitution. It is not difficult to contemplate

the annual or even more frequent litigation that would ensue,

as school boards could continually seek to “ carve out” more

and more components of the educational process.

* Ironically, the circumstances in DeKalb County are a plain illustra

tion of this result. If, indeed, it was appropriate to “ carve out” the area of

student assignments from further district court consideration, then presum

ably such an incremental finding could have been made as early as 1972—

after the school board had purportedly implemented a racially

non-discriminatory student assignment policy for several years. Such an

incremental finding of “ unitary” status, however, would have precluded the

implementation in subsequent years of the very majority-to-minority transfer

programs and magnet school programs that the district court considered

necessary to effectuate the transition to a school system rid of the vestiges of

de jure segregation. See J.A. 216 (majority-to-minority transfer program

adopted in 1972); J.A. 217 (magnet school program adopted in 1980’s).

18

Without having to establish that the racial identity of

schools, or any other vestiges of the de jure system, had been

eliminated, a school board could ask a district court to find

that practicable steps had been taken to eliminate discrimina

tion in some discrete area. School boards could be expected

subsequently to seek one such “ carve out” after another, as

such relief would self-evidently provide a means to limit the

school board’s obligations in the transition to a unitary sys

tem. At the same time, individual litigations over the alleged

“ unitary” status of each facet of a school system could

require protracted factual inquiry in each case—including

expert testimony, or documentary and other evidence con

cerning developments in the school district.

There is, moreover, no reason to believe that school boards

would seek only to “ carve out” the six general facets of

school systems identified in Green. Rather, motions could be

made for “ unitary” findings with respect to particular por

tions of a school district, particular schools, or even particu

lar facets of a single school. Indeed, no limit could easily be

placed on the extent to which motions for incremental “ uni

tary” findings might be narrowly focused.

These scenarios by no means represent mere hypothetical

speculation. In the First Circuit, where incremental findings

of unitary status are permitted, see Morgan v. Nucci, 831

F.2d 313 (1st Cir. 1987), the Boston school board has already

sought such incremental unitary findings for small fragments

of the system, including discrete groups within the system’s

overall teaching staff. See Morgan v. Burke, 926 F.2d 86, 92

(1st Cir. 1991) (school board sought to “ fragment” progress

in desegregation into “ very small parts” and proposed subdi

viding faculty and staff into blacks and other minorities, a

proposal considered similar to subdividing student assign

ments on a school-by-school basis).

C. The vestiges of de jure segregation in DeKalb County

have had interrelated segregative effects, and cannot be

considered in isolation.

The interrelated effects of the vestiges of discrimination in

various aspects of a school system are vividly illustrated in

19

this case. Here, the DCSS argues that it implemented a pur

portedly neutral student assignment plan for some period

beginning in 1969.* Yet even during this period—as before

and at all times thereafter—schools in DeKalb County

retained their racial identity as a result of school board action

in such areas as faculty and staff assignments. Indeed, it is

undisputed that faculty and staff in DeKalb County have

never been desegregated. This meant that the implementation

of the DCSS’s neighborhood student attendance plan, even

from 1969 to 1972, in fact resulted in black students being

assigned predominantly to schools where the black faculty

and staff were located—thereby rendering ineffective on its

face a desegregation plan that under other circumstances

might have served to limit racial identifiability.

The DCSS’s own explanation for the continued segregation

of its faculty and staff illustrates the interrelated effects of

the vestiges of discrimination. The DCSS has attributed fac

ulty and staff segregation largely to faculty and staff prefer

ences to work in schools located near their residences. See

J.A. 76; J.A. 230. This explanation makes plain that school

construction, abandonment and expansion policies—viewed

by the DCSS and the district court as generally falling within

the purview of student assignment policies—have a significant

effect on determining the effectiveness of steps in the area of

faculty assignment.

In this case, moreover, the DCSS took actions during the

life of the desegregation decree that served to exacerbate the

interrelated effects of these perpetuated vestiges. The DCSS

built and expanded existing schools and drew attendance

zones in a manner that guaranteed racial homogeneity, both

of students and faculty, rather than racial integration. Thus

in 1976 the district court had found that the DCSS had

drawn attendance zones in such a way as to increase segrega

tion within the system. J.A. 89-92. The following year, in the

context of considering an expansion of the Flat Shoals ele

mentary school, the district court specifically advised the

DCSS to consider “ alternatives to further construction, such

* The district court, however, was itself unable to determine how long

even these steps in the area of student assignments had been purportedly

effective. J.A. 214.

20

as alterations in attendance zones, and, possibly, some form

of busing, in order to remedy the overcrowding which is

bound to occur and to promote desegregation in the county

schools.” J.A. 122. Moreover, “ in considering additions to

other predominantly black schools in the county,” the DCSS

was “ admonished to keep this in mind.” The district court’s

admonition has gone unheeded.

The racial identities of schools were locked in place by the

DCSS’s continued resistance to effective minority transfer

and magnet schools programs. The DCSS consistently placed

arbitrary restraints on the number of black students able to

transfer to white schools, notwithstanding this Court’s

instruction in Swann that in order for a minority transfer

program to be effective, “ space must be made available in

the school in which [the transferring student] desires to

move.” Swann, 402 U.S. at 26-27. Thus, in 1976, the district

court found that “ the regulations imposed under the M-to-M

program perpetuate the vestiges of the dual system.” J.A. 83.

In 1979, the district court once again was forced to preclude

modifications sought by the DCSS to restrict the numbers of

black students able to transfer to white schools. J.A. 138-50.

The interrelated effects of the vestiges of discrimination in

the various facets of school operations collectively deter

mined, and have perpetuated, the racial identities of the

schools in DeKalb County. While vestiges of the de jure sys

tem remain, various facets of the school system have been

subject to their interrelated effects.

II

THE DEKALB COUNTY SCHOOL SYSTEM REMAINS

UNDER AN AFFIRMATIVE DUTY TO REMEDY, TO

THE EXTENT PRACTICABLE, CURRENT RACIAL

IDENTDIABELITY OF THE SYSTEM’S SCHOOLS

Since 1954, the schools in DeKalb County have retained

their racial identity. Notwithstanding the adoption by the

DCSS of certain purportedly non-discriminatory practices in

the area of student assignment for some period beginning in

1969, it is not disputed that the DCSS never desegregated fac-

21

ulty and staff and always assigned black students dispropor

tionately to those schools in which black faculty and staff

could be found. Moreover, since 1969, the DCSS’s school

construction and abandonment policies have served primarily

to exacerbate the racial identifiability of the schools.

Notwithstanding the continuous racial identifiability of the

schools, the DCSS now claims it should be released from

further court supervision in the area of student assignments—

not because it has satisfied its affirmative duty to complete

the transition to a school system in which the vestiges of de

jure segregation have been eliminated, but because demo

graphic changes during the life of the desegregation decree

purportedly contributed to existing segregated student assign

ments in the district. Given the DCSS’s failure ever to take

the steps necessary to eliminate the blatant racial identifiabil

ity of the county schools, however, there can be little doubt

that the DCSS itself influenced relevant demographic patterns

and their reinforcement of existing racial identification. This

Court has long recognized the causal relationship between the

perpetuation of racial identity of schools and demographic

patterns that serve to reinforce such racial identity. And, in

fact, while the demographic changes occurred, the DeKalb

County school board took steps that served to reinforce and

even exacerbate segregative effects of these patterns. The

DCSS accordingly remains under an affirmative duty to take

practicable steps to remedy the existing racial identification

that now exists in the district’s schools—including in the area

of student assignment.

It remains true that the scope of the affirmative duty to

effectuate the transition to a “ unitary” school system is

defined by the scope of the constitutional violation. Even in a

case where a school board is no longer obligated to imple

ment affirmative remedial steps, however, the school board,

when it does act, remains under a continuing obligation to

take no action that would hinder the constitutionally man

dated transition to a school system in compliance with the

Fourteenth Amendment.

22

A. The demographic changes that have occurred in DeKalb

County cannot shield the school authorities from respon

sibility for remedying existing racial identity in the school

system—including in the area of student assignments.

It is well settled that when a school district has operated a

de jure segregated system, it bears the burden of demonstrat

ing that the existence of racially identifiable schools is not the

result of school board action. See Dayton II, 443 U.S. at 537

(“ systemwide nature of the violation furnished prima facie

proof that current segregation . . . was caused at least in

part by prior intentionally segregative official acts” ); Colum

bus, 443 U.S. at 465 n.13 (burden on the school board was to

prove that its conduct was not a “ contributing cause” of

racial identifiability of schools); Keyes, 413 U.S. at 211 &

n.17 (burden is on the school board to prove that its conduct

did not “ create or contribute to” the racial identifiability of

schools, or that racially identifiable schools are “ in no way

the result of” school board action); Swann, 402 U.S. at 26

(“ [t]he court should scrutinize [predominantly one-race]

schools, and the burden upon the school authorities will be to

satisfy the court that their racial composition is not the result

of present or past discriminatory action on their part” ).

Thus the Courts of Appeals, including the Court below,

have consistently held that a school system that has not

removed all vestiges of segregation cannot avoid the constitu

tional obligation to do so on the basis of claims that ongoing

demographic changes have made the process more difficult.

See Vaughns v. Board o f Educ., 758 F.2d 983, 988 (4th Cir.

1985); Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd., 721

F.2d 1425, 1435 (5th Cir. 1983); Lee v. Macon County Bd. o f

Educ., 616 F.2d 805, 810 (5th Cir. 1980). This doctrine

reflects the principle that school authorities cannot avoid the

continuing duty to desegregate a school system based on the

consequences of their failure, to date, effectively to dismantle

all features or vestiges of the dual system. These holdings are

supported by the decisions of this Court in Columbus and

Swann and are premised on the clear recognition by this

Court that patterns of segregated schooling influence housing

choices and cause or contribute to residential segre-

23

gation—with the result that the patterns of school segregation

are compounded and exacerbated.*

In this case, it would be difficult for the DCSS to maintain

its burden of demonstrating that existing racial segregation is

not the result of school board action, given the district’s pre

viously described segregative actions. It is an insuperable bur

den in light of the responsibility of school authorities for

influencing demographic patterns that have reinforced the

racial identity of the schools, and the actions of the school

authorities that actually magnified the segregative effects of

those demographic changes.

It should come as no surprise that the demographic

changes in DeKalb County occurred in racially identifiable

patterns reinforcing the racial identifiability of the DCSS

schools. This Court has long recognized that “ people gravi

tate toward school facilities,” Swann, 402 U.S. at 20, and

that racially identifiable schools influence the gravitational

pull. Indeed, the DCSS’s claim that it should be released

from its affirmative duty to dismantle the dual system

because of demographic changes is certainly not novel, and

similar claims have already been rejected by this and lower

courts. In Columbus, for example, school authorities con

tended that “ because many of the involved schools were in

areas that had become predominately black residential areas

by the time of trial, the racial separation in the schools would

have occurred even without the unlawful conduct of [the

school board].” Columbus, 443 U.S. at 465 n.13. That

* This rule is not one of absolute liability without regard to the facts

and circumstances of a particular case, however, as the opinion of the Court

below might be read. This C ourt’s school desegregation precedent establishes

a framework according to which a previously de jure school district may seek

to demonstrate that segregation in its schools or programs is not the result of

the dual system, its failure to eradicate that system and its effects, or any

actions it has taken that have impeded that process. A school board that has

effectively implemented remedies to desegregate all aspects of a school sys

tem and, therefore, has removed the racial identifiability and stigma that

influence housing choice and residential segregation, may be in a position to

demonstrate that subsequently occurring racial imbalance is not the product

of any failure to dismantle de jure schooling. Whatever the circumstances in

which a district could carry this burden, they are not presented by the DCSS

in this case.

24

argument—then as it should be now—was easily dispatched

by this Court: “ the phenomena described by [the school

board] seems only to confirm, not disprove . . . that school

segregation is a contributing cause of housing segregation.”

Id. (emphasis added). This Court found persuasive the dis

trict court’s findings that notwithstanding adoption of an

ostensibly racially neutral attendance policy, the school

board’s failure to dismantle the dual school system perpetu

ated racially identifiable residential patterns. See Penick v.

Columbus Bd. o f Educ., 429 F. Supp. 229, 259 (S.D. Ohio

1977).

The DCSS obviously did not cause people to move into

DeKalb County. But as explained in Keyes, the perpetuation

of identifiably black or white faculty in schools

[has] the clear effect of earmarking schools according to

their racial composition, and this, in turn, together with

the elements of student assignment and school construc

tion, may have a profound reciprocal effect on the racial

composition of residential neighborhoods within a

metropolitan area, thereby causing further racial concen

tration within the schools.

—Keyes, 413 U.S. at 202.

By failing to eliminate the racial identifiability of its schools,

the DCSS cast the die for the occurrence of demographic

changes that would reinforce the racial identifiability of the

schools.

Moreover, once those demographic changes began and the

need arose for increased school capacity to accommodate the

increased student population, the DCSS affirmatively exacer

bated the effects of the demographic changes on the school

system through its policy of expansion. Rather than build

schools or expand existing schools in areas that promised a

racially diverse student body, the DCSS instead built and

expanded schools in the peripheral parts of DeKalb County

that guaranteed racial homogeneity. Together with the neigh

borhood student attendance plan and restricted minority

transfer programs, the new and expanded schools locked the

system into a separation of the races. Black schools were

25

located in areas within DeKalb County that assured their

racial identifiability would remain intact.

In Swann, this Court recognized that within a school sys

tem that had yet to achieve unitary status, the location of

schools can have a powerful effect on residential patterns,

particularly when the students are assigned to schools on a

neighborhood zoning basis:

The location of schools may thus influence the patterns

of residential development of a metropolitan area and

have important impact on composition of inner-city

neighborhoods.

In the past, choices in this respect have been used as a

potent weapon for creating or maintaining a state-

segregated school system. In addition to the classic pat

tern of building schools specifically intended for Negro

or white students, school authorities have sometimes,

since Brown, closed schools which appeared likely to

become racially mixed through changes in neighborhood

residential patterns. This was sometimes accompanied by

building new schools in the areas of white suburban

expansion farthest from Negro population centers in

order to maintain the separation of the races with mini

mum departure from the formal principles of ‘neighbor

hood zoning.’ Such a policy does more than simply

influence the short-run composition of the student body

of a new school. It may well promote segregated resi

dential patterns which, when combined with ‘neighbor

hood zoning,3 further lock the school system into the

mold o f separation o f the races.

—Swann, 402 U.S. at 20-21

(emphasis added).

Studies by social scientists have confirmed that racially

identifiable schools influence demographic patterns so as to

reinforce the schools’ racial identifiability. See, e.g., Bil

lingsley, et al., “ School Segregation and Residential Segrega

tion: A Social Science Statement,” in School Desegregation:

Past, Present, and Future 240 (W.G. Stephan & J.R. Feagin,

eds.) (1980). Indeed, as thirty-eight social scientists agreed in

26

a collective statement, “ [a]ll discriminatory acts by school

authorities that contribute to the racial identifiability of

schools promote racially identifiable neighborhoods.” Id. at

236.

Moreover, a school board can trigger or influence a

racially identifiable demographic trend in neighborhoods by

“ signalling” that the racial identity of an existing school is to

change, or, in the case of a new school, what its racial iden

tity will be. This is particularly so in communities undergoing

substantial demographic changes, because “ the changing

racial composition of a school’s pupils and staff serves as a

signal to the public—realtors, homeseekers, residents, etc.—

that school authorities expect the school to become all

black.” Tauber, Demographic Perspectives on Housing and

School Segregation, 21 Wayne L. Rev. 833, 843 (1975). See

also “ School Segregation and Residential Segregation: A

Social Science Statement,” supra, at 235 (“ [c]hange in the

racial identifiability of a school can influence the pace of

change in racial composition in a ‘changing’ residential

area” ).

A significant, and perhaps most obvious, reason for this

relationship between racially identifiable schools and demo

graphic patterns is that parents perceive that black schools

are generally inferior to white schools. See, e.g., Tauber,

Demographic Perspectives on Housing and School Segrega

tion, supra, 21 Wayne L. Rev. at 843 (“ if predominantly

black schools were not perceived as inferior schools, then

school attendance zones would play only a minor role in resi

dential choices and in the behavior of real estate busi

nesses” ).

Swann, Keyes and Columbus teach that when assessing the

relationship between racially identifiable demographic trends

and school board action, the district court must consider the

acts (and omissions) of the school board before and during

the time period in which those trends occurred. An analysis

which considers only the present overlooks the vital question:

whether past actions have contributed to present harm. This

“ segregative snowball” effect, Penick v. Columbus Bd. o f

Educ., 429 F. Supp. 229, 259 (S.D. Ohio 1977), has been rec

ognized by numerous lower courts and taken into account

27

when determining the appropriate scope of relief required to

effectively desegregate a formerly de jure school system.*

Not surprisingly, racially identifiable demographic trends

are less likely in communities which have undergone success

ful school desegregation. “ School desegregation, if effectively

implemented, removes the racial identifiability of schools,

and hence removes one of the restrictions on housing choice

by white and black families.” Tauber, “ School Desegregation

and Racial Housing Patterns,” in New Directions fo r Testing

and Measurement: Impact o f Desegregation 63 (D. Monti,

ed.) (1982). “ [S]chool desegregation has helped ease the tra

ditional patterns of rigid residential segregation. . . . Once

the racial character of a neighborhood can no longer easily

be stamped by an identification of its schools as black or

white, racial barriers in housing begin to lower.” Taylor,

Brown, Equal Protection and the Isolation o f the Poor, 95

Yale L.J. 1700, 1711 (1986) (citing D. Pearce, Breaking

Down Barriers: New Evidence on the Impact o f Metropolitan

School Desegregation on Housing Patterns (1980)).

Here, by contrast, the district court’s reliance on demo

graphic changes to relieve the DCSS of its duty to desegre

gate the schools in DeKalb County simply ignored how

demographic changes responded to, and thus reinforced,

racially identifiable schools. Had the DCSS effectively acted

to remedy the vestiges of de jure segregation, the DCSS

would not today retain its dual characteristics.

The district court’s analysis of the DCSS’s responsibility

for the current racial identifiability of the schools in DeKalb

County overlooked the critical analysis: whether those ves-

* See, e.g. , United States v. Yonkers Bd. ofEduc., 624 F. Supp, 1276

(S.D.N.Y. 1985), a ff’d, 837 F.2d 1181 (2d Cir. 1987), cert, denied, 486 U.S.

1055 (1988); United States v. Board o f School Comm’rs, 573 F.2d 400, 408-

09 n.20 (7th Cir. 1978); NAACP v. Lansing Bd. o fE duc., 559 F.2d 1042,

1049 n.9 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 997 (1977); Evans v. Buchanan,

393 F. Supp. 428, 436-37 (D. Del.), a ff’d, 423 U.S. 963 (1975); Hart v. Com

munity School Bd., 383 F. Supp. 699, 706 (E.D.N.Y. 1974), a ff’d, 512 F.2d

37 (2d Cir. 1975); Davis v. School District, 309 F. Supp. 734, 742 (E.D.

Mich. 1970), a ff’d, 443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 913 (1971).

See also Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277, 1291 (8th Cir.) (public per

ception of racial identity of a school is a powerful factor in shaping neigh

borhood residential patterns), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 826 (1980).

28

tiges of the de jure system, such as segregated faculty and

staff, which have perpetuated the racial identities of the

schools, contributed to the racially segregated character of

demographic changes. The burden properly belonged on the

DCSS to demonstrate that such segregative demographic

changes were not influenced by racial identity of the schools

that school authorities had themselves caused or perpetuated.

Moreover, the district court was clearly erroneous in conclud

ing that the DCSS’s actions in response to the demographic

changes had achieved maximum practical desegregation in

light of the DCSS’s record with regard to the location of new

schools, the neighborhood student attendance plan, and the

restricted minority transfer programs—steps that exacerbated

the segregative effects of the demographic changes.

Because the current segregation of student assignments can

only properly be considered a vestige of de jure segregation

in DeKalb County, the DCSS continues to bear the duty to

implement affirmative steps to remedy, to the extent practica

ble, this racial identifiability. Consideration of remedies, of

course, must be based upon the current circumstances in the

school system rather than those existing at an earlier point in

the desegregation process. This case should be remanded to

the district court so that the school board itself can imple

ment necessary remedies. In the event of default by the

school board in that duty, the district court will be in the best

position to fashion an appropriate remedy.

B. Where a school board that has not completed the transi

tion to a unitary system is not obligated to implement fur

ther affirmative remedial steps, school authorities, when

they do act, remain obligated to take no action that

would impede completion of the transition.

The continuing obligation of the DCSS to achieve the

transition to a unitary system is fully consistent with the

Fourteenth Amendment principle that a school board’s

affirmative duty in a given district is defined by the scope of

the constitutional violation. See, e.g., Swann, 402 U.S. at 16;

Milliken v. Bradley (Milliken II), 433 U.S. 267, 282 (1977).

This Court has, of course, long recognized that the vestiges

29

of de jure segregation can be manifest or perpetuated

through various means that are thus embodied within the vio

lation of the Fourteenth Amendment. See Point I, supra.

Moreover, as this Court reiterated in Dayton II, the obliga

tion to effectuate the transition to a unitary system includes

“ the obligation not to take any action that would impede the