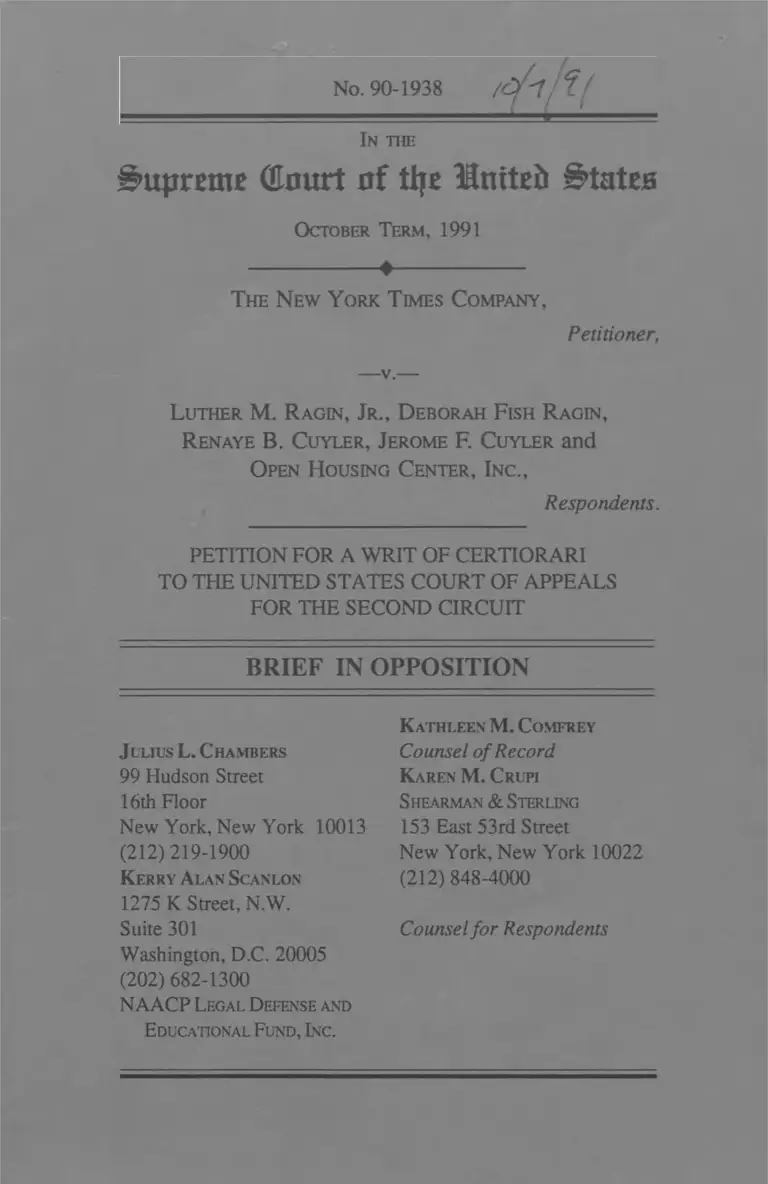

The New York Times Company v. Ragin Brief in Opposition

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. The New York Times Company v. Ragin Brief in Opposition, 1991. 4cc0658f-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a4d56358-1c05-4893-aed8-c76aa2fa3430/the-new-york-times-company-v-ragin-brief-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In th e

Supreme (Eourt of ttje lEnitefc States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1991

---------------------- ♦ ----------------------

The N ew Y ork T imes Company,

Petitioner,

Luther M. R agin, Jr., D eborah F ish R agin,

R enaye B. Cuyler, Jerome F. Cuyler and

O pen H ousing C enter, Inc .,

Respondents.

PE T IT IO N FO R A W R IT O F C E R T IO R A R I

T O T H E U N IT E D STA TES C O U R T O F A PPEA L S

FO R TH E SE C O N D C IR C U IT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

J u lius L. C h am bers

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212)219-1900

K erry A lan S c a n lo n

1275 K Street, N.W .

Suite 301

W ashington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

N A A C P L egal D efense and

E ducational F u n d , In c .

K a t h l e e n M . C o m fr e y

Counsel o f Record

K a r e n M . C rupi

S hearm an & S terling

153 East 53rd Street

New York, New York 10022

(212) 848-4000

Counsel fo r Respondents

Q U ESTIO N PRESEN TED

1. Should the Court grant certiorari to consider an interlocutory

decision interpreting the Fair Housing Act that is in agreement

with the only other circuit court decision on point, from

which this Court recently denied certiorari, and that is

supported by the applicable administrative regulations?

- i -

PARTIES BELOW

Pursuant to Rule 29.1 o f the Rules of this Court, respondent Open

Housing Center, Inc. informs the Court that it has no parent company and

has no subsidiary other than Open Housing Services, Inc., a wholly-

owned subsidiary.

- Ill -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTION PRESENTED................................................................... i

PARTIES BELO W ................................................................................ ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............................................................... v

CONSTITUTIONAL, STATUTORY AND

REGULATORY PR O V ISIO N S......................................................... 1

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE C A S E ...................................... 3

REASONS FOR DENYING THE W R IT ......................................... 4

I. RESPONDENTS’ DISCRIMINATORY

ADVERTISING CLAIM IS PLAINLY

SUFFICIENT TO SURVIVE A MOTION

TO D ISM ISS ................................................................. 4

A. THERE IS NO CONFLICT AMONG

THE CIRCUIT CO U R TS................................ 4

B. THE SECOND CIRCUIT’S

DECISION IS SUPPORTED

BY LONGSTANDING ADMINIS

TRATIVE IN TERPRETA TIO N .................... 7

C. THE FIRST AMENDMENT DOES

NOT SHIELD COMMERCIAL

SPEECH THAT INDICATES A

RACIAL PREFERENCE ............................... 8

II. REVIEW OF THE INTERLOCUTORY

DECISION BELOW IS PREM ATURE.................... 10

CONCLUSION 11

APPENDIX Page

Exhibits to Complaint

Ex. 1 - Consent Agreement With The Washington P o s t ............... lb

Ex. 2 - The New York Tim es’ Correspondence to Advertisers

Regarding Its Advertising Acceptability Policy............. 13b

Ex. 3 - The New York Tim es’ Standards of Advertising

A cceptability ............................................................................ 15b

- iv -

- V -

TA BLE O F A U TH O RITIES

Cases Page

American Constr. Co. v. Jacksonville, Tampa, and Key

West Ry. Co., 148 U.S. 372 (1893)............................................. 10

Ashwander v. TVA, 297 U.S. 288 (1936)................................... 10

Associated Press v. NLRB, 301 U.S. 103 (1937)...................... 8n

Board o f Trustees v. Fox, 492 U.S. 469 (1989)........................ 9

Central Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Public

Serv. Comm’n, 447 U.S. 557 (1980)........................................... 9

Chevron U.S A., Inc. v. Natural Resources

Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984).............................. 8

Cohen v. Cowles Media Co., 59 U.S.L.W. 4773

(U.S. June 24, 1991 No. 90-634)................................................. 8n

Fenwick-Schafer v. Sterling Homes Corp.,

No. R-90-1376, (D. Md. Mar. 28, 1 9 9 1 )................................... 5, 7

Gladstone, Realtors v. Village ofBellwood,

441 U.S. 91 (1979).......................................................................... 7-8

Hamilton-Brown Shoe Co. v. Wolf Bros. & Co.,

240 U.S. 251 (1916)........................................................................ 10

Housing Opportunities Made Equal v. The

Cincinnati Enquirer, Inc., 731 F. Supp. 801

(S.D. Ohio 1990), appeal pending, No. 90-3176 (6th Cir.).... 5, 6, 10

Maryland v. Baltimore Radio Show, Inc.,

338 U.S. 912 (1950)........................................................................ 10

Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co., 110 S. Q . 2695 (1990)...... 9-10

Ohralik v. Ohio State Bar Ass’ n, 436 U.S. 447 (1 9 7 8 ).......... 9

Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Comm’n on Human

Relations, 413 U.S. 376 (1973).................................................... 9

Cases Page

Posadas de Puerto Rico Assocs. v. Tourism

Co. o f Puerto Rico, 478 U.S. 328 (1986)................................... 9

Ragin v. Steiner, Clateman and Assocs., Inc.,

714 F. Supp. 709 (S.D.N.Y. 1989).............................................. 5, 6, 8, 10

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court o f Los Angeles,

331 U.S. 5 4 9 (1 9 4 7 )....................................................................... 10

Saunders v. General Services Corp., 659 F. Supp.

1042 (E.D. Va. 1987)..................................................................... 5, 6

Spann v. Colonial Village, Inc., 662 F. Supp.

541 (D. D.C. 1987), rev’d in relevant part and

remanded, 899 F.2d 24 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied,

111 S. Ct. 508, 509 (1990) and 111 S. Ct. 751

(1 9 9 1 )................................................................................................ 5 ,6

Spann v. Colonial Village, Inc., 124 F.R.D.

1 (D. D.C. 1988), rev’d on other grounds and

remanded, 899 F.2d 24 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied,

111 S. Q . 508, 509 (1990) and 111 S. Ct. 751

(1 9 9 1 )................................................................................................ 8

Spann v. Colonial Village, Inc., 899 F.2d

24 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied. 111 S. Q .

508, 509 (1990) and 111 S. Ct. 751 (1 9 9 1 )............................... 5 ,6

Spann v. The Carley Capital Group, 734

F. Supp. 1 (D. D.C. 1988)............................................................. 5, 7

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co.,

409 U.S. 205 (1972)....................................................................... 8

- vi -

United States v. Hunter, 459 F.2d 205 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 934 (1972).......................... 7 ,8

- V l l -

Cases

Constitutional Provisions

U.S. Const, amend. I ...................................................................... 1 ,4 , 8-9

Rules & Regulations

Federal Rules o f Civil Procedure

Rule 12(b)(6).................................................................................... 3

Supreme Court Rules

Rule 2 9 .1 ............................................................................ ii

HUD Regulations

37 Fed. Reg. 6700 (1 9 7 2 ).............................................. 7

45 Fed. Reg. 57102 (1 9 8 0 )............................................ 7

24 C.F.R. § 109.10........................................................... 1 ,5

24 C.F.R. § 109.16(a)(1)................................................. 1 ,5

24 C.F.R. § 109.25(c)...................................................... 1-2, 5, 7

24 C.F.R. § 109.30(b)..................................................... 2-3, 5, 7

Statutes

Fair Housing Act

42 U.S.C. § 3601 (1 9 8 2 )................................................................ 8

42 U.S.C. § 3604(c) (1988) (as am ended)................................. passim

1

CO N STITU TIO N A L, STATUTORY

AND REG U LA TO RY PROV ISIO N S

The pertinent text of the First Amendment and the Fair Housing

Act o f 1968 (the “Act”), 42 U.S.C. § 3604(c) (1988) (as amended), is set

forth in the Petition at 3.1 Below are reproduced in full the relevant

regulations issued by the United States Department o f Housing and Urban

Development (“HUD”), 24 C.F.R. Part 109 (1990):

§ 109.10 Purpose.

The purpose of this part is to assist all advertising media,

advertising agencies and all other persons who use advertising to make,

print, orpublish, orcauseto be made, printed, orpublished, advertisements

with respect to the sale, rental, or financing of dwellings which are in

compliance with the requirements of the Fair Housing Act. These

regulations also describe the matters this Department will review in

evaluating compliance with the Fair Housing Act in connection with

investigations of complaints alleging discriminatory housing practices

involving advertising.

§ 109.16 Scope.

(a)(1) Advertising media. This part provides criteria for use by

advertising media in determining whether to accept and publish advertising

regarding sales or rental transactions. Use o f these criteria will be

considered by the General Counsel in making determinations as to

whether there is reasonable cause to believe that a discriminatory housing

practice has occurred or is about to occur.

§ 109.25 Selective use of advertising media or content.

The selective use of advertising media or content when particular

combinations thereof are used exclusively with respect to various housing

developments or sites can lead to discriminatory results and may indicate

a violation of the Fair Housing Act. For example, the use o f English

1. The opinions of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and the

United States District Court for the Southern District of New York are reported at 923

F.2d 995 (2d Cir. 1991) and 726 F. Supp. 953 (S.D.N.Y. 1989).

2

language media alone or the exclusive use o f media catering to the

majority population in an area, when, in such area, there are also available

non-English language or other minority media, may have a discriminatory

impact. Similarly, the selective use o f human models in advertisements

may have a discriminatory impact. The following are examples of the

selective use of advertisements which may be discriminatory:

* * * *

(c) Selective use of human models when conducting an

advertising campaign. Selective advertising may

involve an advertising campaign using human models

primarily in media that cater to one racial or national

o rig in segm ent o f the popu lation w ithout a

complementary advertising campaign that is directed

at other groups. Another example may involve use

o f racially mixed models by a developer to advertise

one development and not others. Similar care must

be exercised in advertising in publications or other

media directed at one particular sex, or at persons

without children. Such selective advertising may

involve the use of human models of members o f only

one sex, or of adults only, in displays, photographs

or drawings to indicate preferences for one sex or the

other, or for adults to the exclusion of children.

§ 109.30 Fair housing policy and practices.

In the investigation of complaints, the Assistant Secretary will

consider the implementation of fair housing policies and practices provided

in this section as evidence of compliance with the prohibitions against

discrimination in advertising under the Fair Housing Act.

* * * *

(b) U se o f hum an m odels. H um an m odels in

photographs, drawings, or other graphic techniques

may not be used to indicate exclusiveness because of

race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status,

or national origin. If models are used in display

advertising campaigns, the models should be clearly

3

definable as reasonably representing majority or

minority groups in the metropolitan area, both sexes,

and, when appropriate, families with children.

Models, if used, should portray persons in an equal

social setting and indicate to the general public that

the housing is open to all without regard to race,

color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status, or

national origin, and is not for the exclusive use of one

such group.

CO U N TERSTA TEM EN T O F T H E CASE

1. Because this case arises on a threshold Rule 12(b)(6) motion

to dismiss, there has been no discovery and the decision is interlocutory.

The record is, therefore, ill-suited to plenary review by the Court of the

broad legal issues The New York Times (the ‘T im es”) seeks to raise here.

2. Contrary to petitioner’s assertion that respondents “did not

allege a single fact, direct or circumstantial, indicating any intent on the

part o f The Times to convey any such discriminatory preference,”

Petition at 5, the Complaint alleges, among other things, that the Times

has engaged in a lucrative, twenty-year practice of publishing racially

exclusive real estate ads “featuring thousands of human models of whom

virtually none were black,” Complaint 8 ,1 1 ,1 2 (Pet. App. 48a, 50a);

that those few Blacks who were depicted in real estate ads were portrayed

in m inor or subservient roles “as building maintenance employees,

doormen, entertainers, sports figures, small children, or cartoon characters,”

rather than as potential homeowners or renters, Complaint f 12 (Pet. App.

50a); and that all-W hite human models were featured in ads for

predominately White buildings or neighborhoods and all-Black models

were featured in ads for predominately Black buildings or neighborhoods.

Complaint 18 (Pet. App. 52a). The Complaint further alleges that the

Times, after receiving direct notice from respondents that its practices

were illegal, continued to publish single-race advertising. Complaint

UK 14-18 (Pet. App. 51a-52a). These facts are more than sufficient to

support respondents’ general allegation that the Times “intentionally and

maliciously violated their civil rights.” Complaint H 22 (Pet. App. 52a).

4

3. Petitioner misstates the holding of the District Court when it

asserts that it held that “the Fair Housing Act requires a ‘ fair representation’

of models by race.” See Petition at 6. To the contrary, the District Court

simply concluded, consistent with the plain statutory language and prior

caselaw, that the ultimate issue for the factfinder is whether “the natural

interpretation” of the ads published by petitioner indicates a racial

preference to the ordinary reader. See 726 F. Supp. at 957 (Pet. App. 26a)

(citation omitted). In so holding, the District Court recognized that a

factfinder could lawfully conclude from proof that the challenged ads

contained a paucity o f Blacks that the ads conveyed an illegal racial

message. 726 F. Supp. at 961 (Pet. App. 34a).

4. Contrary to petitioner’s assertions, the Second Circuit’s

construction of the Act does not compel publishers to impose “mandatory

percentages” of minority models, or to investigate each advertiser’s

intent. See Petition at 16, 17. Instead, it merely requires the Times to

screen the ads it publishes for racially discriminatory messages. In

rejecting petitioner’s First Amendment arguments, the Second Circuit

took notice of the extensive monitoring procedures the Times already has

in place, 923 F.2d at 1004 (Pet. App. 14a-15a), and observed that“ [g]iven

that this extensive monitoring — for purposes that are both numerous and

often quite vague— is routinely performed, it strains credulity beyond the

breaking point to assert that monitoring ads for racial messages imposes

an unconstitutional burden.” 923 F.2d at 1004 (Pet. App. 16a); see also

Complaint Ex. 2, 3 (Res. App. 13b-16b); cf. Complaint Ex. 1 (Res. App.

lb-12b).

REASONS FO R DENYING T H E W R IT

I. RESPO N D EN TS’ D ISC RIM IN A TO RY

A D VERTISIN G CLAIM IS PLA IN LY

SU FFIC IEN T TO SURVIVE A M O TIO N

TO DISM ISS

A. T H ER E IS NO C O N FL IC T AM ONG TH E

C IR C U IT COURTS

Section 3604(c) of the Fair Housing Act prohibits the publishing

o f any real estate advertising “that indicates any preference, limitation, or

discrimination based on race [or] color.” 42 U.S.C. § 3604(c). The

5

Second Circuit did nothing more than allow respondents’ claim to

proceed on the uncontroversial premise that a reasonable jury could find

that petitioner’s consistent practice of printing and publishing real estate

ads with a paucity of Black models in a metropolitan area with a

significant Black population indicates a racial preference. 923 F.2d at

1001 (P e t App. 10a). The alarm raised by petitioner at the possibility o f

incurring liability for real estate ads that fail to match the precise

“percentage” or “proportion” of every protected group under the Act, see

Petition at 16-17, is simply a straw man. See 923 F.2d at 1001 (Pet. App.

10a); 726 F. Supp. at 959 (Pet. App. 30a).

The Second Circuit’s standard for discriminatory advertising —

the natural interpretation of the ad to the ordinary reader — is supported

by the nearly uniform caselaw on the issue. The federal courts have

consistently concluded that, as a matter o f law, a complaint challenging

real estate ads featuring all-White or virtually all-White models, such as

those involved in this case, states a cognizable claim under the Act. See

Spann v. Colonial Village, Inc., 899 F.2d 24, 29-30, 34-35 (D.C. Cir.),

cert, denied, 111 S. Ct. 508,509 (1990) and 111 S. Ct. 751 (1991); Ragin

v. Steiner, Clateman andAssocs., Inc., 714 F. Supp. 709, 713 (S.D.N.Y.

1989); Spann v. The Carley Capital Group, 734 F. Supp. 1, 3 (D. D.C.

1988); Saunders v. General Services Corp., 659 F. Supp. 1042, 1058

(E.D. Va. 1987); Fenwick-Schafer v. Sterling Homes Corp., No. R-90-

1376, slip op. at 10 (D. Md. Mar. 28,1991); see also 24 C.F.R. §§109.10;

109.16(a)(1); 109.25(c); 109.30(b). The only decision supporting the

T im es’ position is a solitary District Court opinion now on appeal to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. See Housing

Opportunities Made Equal v. The Cincinnati Enquirer, Inc. ,131 F. Supp.

801 (S.D. Ohio 1990), appeal pending, No. 90-3176 (6th Cir.).

The principal case relied upon by the Times — the District

Court’s decision in Spann v. Colonial Village, Inc., 662 F. Supp. 541,546

(D. D.C. 1987), rev’d in relevant part and remanded, 899 F.2d 24 (D.C.

Cir.), cert, denied. 111 S .Q . 508,509(1990) and 111 S .C t.751 (1991),

and quoted throughout the petition — was reversed by the Court of

Appeals on the precise liability point for which the Times cites it. See

Colonial Village, 899 F.2d at 29-30. In Colonial Village, the District

Court had dismissed claims based on a developer’s and an advertising

agency’s all-White advertising practices on statute o f limitations grounds.

The District Court indicated that in order to state a claim under Section

6

3604(c), the plaintiffs would have to show eitherthat the racial preference

was “obvious from the ad itse lf’ or “that such preference be ascertainable

through extrinsic circumstances.” Colonial Village, 662 F. Supp. at 546.

The Court of Appeals’ disagreement with the District Court’s

intent or extrinsic circumstances standard is apparent from the opinion.

See Colonial Village, 899 F.2d at 29-30. Reversing the District Court’s

findings that the all-White advertising claims were untimely, see id. at 34-

35, the District o f Columbia Circuit adopted the ordinary reader standard,

and expressly remanded the proceeding for a jury trial on the question of

whether all-White advertising by itself violates Section 3604(c). Id. at 29-

30, 34-35; see also id. at 29-30 (recognizing that it is a “question o f fact

for [the] jury whetherall-whiteadvertisementsviolate42U.S.C.§ 3604(c)”

(citing Ragin v. Steiner, Clateman and Assocs., Inc., 714 F. Supp. 709,

713 (S.D.N.Y. 1989)). The defendants in the Colonial Village case

sought certiorari on the same questions the Times now seeks to raise, and

the Court denied certiorari. See 111 S. Ct. 508,509 (1990) and 111 S. Ct.

751 (1991).

In light o f this reversal, the District Court’s decision in Housing

Opportunities Made Equal v. The Cincinnati Enquirer, lnc.,13\ F. Supp.

801 (S.D. Ohio 1990), appeal pending, No. 90-3176 (6th Cir.) — also

relied on heavily by petitioner — fails for the same reasons. In that

decision, the District Court placed almost singular reliance on the

extrinsic circumstances or intent analysis contained in the District Court

decision in Colonial Village. See id. at 803-04. However, less than a

month after the Cincinnati Enquirer decision was issued, the District of

Columbia Circuit reversed in relevant part the District Court’s holding in

Colonial Village. Moreover, the District Court’s interpretation o f the

Saunders and Steiner, Clateman cases as requiring extrinsic evidence of

intent, id. at 804, is contrary to the plain language of those decisions. See

Saunders, 659 F. Supp. at 1058; Steiner, Clateman, 714 F. Supp. at 713.

The Times ’ description— or om ission— of the other lower court

precedents is equally inaccurate. See Saunders, 659 F. Supp. at 1058

(applying the ordinary reader standard and holding that virtually all-

White real estate ads indicate a racial preference to the ordinary reader);

Steiner, Clateman, 714 F. Supp. at 713 (holding that all-White human

model real estate advertising states a viable claim under Section 3604(c));

7

Carley Capital, 734 F. Supp. at 3 (holding that all-White human model

advertising states a claim); Fenwick-Schafer v. Sterling Homes Corp.,

No. R-90-1376, slip op. at 5-6, 10 (D. Md. Mar. 28,1991) (holding that

all-White ads can indicate a racial preference to the ordinary reader); cf.

United States v. Hunter, 459 F.2d 205, 215 (4th Cir.) (applying the

ordinary reader standard and holding that it “would severely undercut the

objectives o f the [Fair Housing Act]” to permit subtle forms of racial

preference to be used in substitution for more blatant discriminatory

phrases), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 934 (1972).

The purported conflict among the courts alleged by petitioner,

therefore, does not exist.

B. T H E SECOND C IR C U IT ’S D ECISIO N IS

SU PPO RTED BY LO NGSTANDING

AD M IN ISTRA TIV E IN TER PR E TA TIO N

Contrary to petitioner’s assertion that the Second Circuit “did not

base its interpretation of Section 3604(c) on the HUD regulations,” see

Petition at 15 n. 10, the Second Circuit expressly stated that it was relying

on the HUD regulations “as additional support for the view that racial

messages conveyed by the use of human models are not exempted” from

the scope of Section 3604(c). 923 F.2d at 1000 n .l (Pet. App. 7a n .l).

Since 1972, HUD has expressly interpreted Section 3604(c) to

prohibit the use o f human models in real estate ads to indicate racial

exclusiveness, and its regulations directly support respondents’ claim

here. See 37 Fed. Reg. 6700 (1972); 45 Fed. Reg. 57102 (1980). H U D’s

regulations provide that “ [h]uman models in photographs, drawings, or

other graphic techniques may not be used to indicate exclusiveness

because of race [or] color” and “should be clearly definable as reasonably

representing majority and minority groups in the metropolitan area.” 24

C.F.R. § 109.30(b); see also 24 C.F.R. § 109.25(c) (discussing examples

of the discriminatory use of human models in violation o f Section

3604(c)).

Contrary to petitioner’s suggestion that the regulations are

“precatory,” see Petition at 15 n. 10, HUD is “the federal agency primarily

assigned to implement and administer” the Act, and its “interpretation of

the statute ordinarily commands considerable deference.” Gladstone,

8

Realtors v. Village of Bellwood, 441 U.S. 91, 107 (1979); see also

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205, 210 (1972)

(HUD’s interpretation “is entitled to great weight”) (citations omitted).

The statutory language o f Section 3604(c) broadly prohibits all forms of

racially discriminatory advertising practices and makes no exception for

the use of discriminatory pictures. Given that the Act must be construed

broadly to effectuate Congress’ purpose to provide “for fair housing

throughout the United States,” 42 U.S.C. § 3601 (1982); Trafficante, 409

U.S. at 209, it is clear that H U D’s interpretation of Section 3604(c) to

apply to the discriminatory use of human models is reasonable, not

contrary to clear congressional intent, and thus must be followed here.

See Chevron U.S A ., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.,461

U.S. 837,842-45 (1984); see also Hunter, 459 F.2d at 215 n .l 1 (citing the

HUD regulations in support of its conclusion thatnewspapers are explicitly

subject to the Act); Steiner, Clateman,l\4 F. Supp. at 713 n.3 (“use of all

white human model display advertising is contrary to H.U.D. regulations

which are entitled to deference”); Spann v. Colonial Village, Inc., 124

F.R.D. 1, 3 (D. D.C. 1988) (“ [t]he regulations are of course entitled to

substantial deference by the Court when interpreting the Fair Housing

Act”) (citation omitted), rev’don other grounds and remanded, 899 F.2d

24 (D.C. Cir.) cert, denied, 111 S. Ct. 508,509 (1990) and 111 S. Ct. 751

(1991).

C. TH E FIR ST AM ENDM ENT DOES NOT

SH IELD C O M M E R C IA L SPEEC H TH A T

IND ICA TES A RA CIA L PR E FE R E N C E

Contrary to the overstated First Amendment claims of petitioner,

the Second Circuit’s decision does not in any way affect a news publisher’s

editorial independence, but rather involves the T im es’ highly lucrative

and purely commercial real estate advertising section. See 923 F.2d at

1002-1003 (Pet. App. 11 a-14a).2 * As this Court recently emphasized,

2. The Second Circuit properly recognized that, as a newspaper, petitioner is accorded

no special immunity from compliance with the A ct See 923 F.2d at 1003-1004 (Pet.

App. 13a-14a). Indeed, this Court recognized justlastmonththatitis“beyonddispute

that4 [t]he publisher of a newspaper has no special immunity from the application of

general laws.’ ” Cohen v. Cowles Media Co., 59 U.S.L.W. 4773,4775 (U.S. June 24,

1991 No. 90-634)(quoting Associated Press v. NLRB, 301 U.S. 103,132-33 (1937));

see also 726 F. Supp. at 962 n.l (Pet. App. 37a n.l).

9

commercial speech is accorded only “ ‘a limited measure o f protection,

commensurate with its subordinate position in the scale of First Amendment

values, ’ and is subject to ‘ modes of regulation that might be impermissible

in the realm of noncommercial expression.’ ” Board o f Trustees v. Fox,

492 U.S. 469,477 (1989)(quoting Ohralik v. Ohio State Bar Ass’n, 436

U.S. 447, 456 (1978)). Moreover, it is beyond dispute that illegal

commercial speech receives no First Amendment protection. See Posadas

de Puerto Rico Assocs. v. Tourism Co. o f Puerto Rico, 478 U.S. 328,340

(1986); Central Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Public Serv. Comm’ n, 447

U.S. 557, 563-64, 566 (1980).

As the Second Circuit correctly observed, the Court has already

rejected petitioner’s argument that the First Amendment protects a

newspaper’s publication of discriminatory advertisements. See 923 F.2d

at 1003 (Pet. App. 12a). In Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Comm’ n

on Human Relations, 413 U.S. 376 (1973), a newspaper violated an

ordinance prohibiting gender-based employment advertising by printing

ads under sex-designated columns. In upholding the ordinance over the

newspaper’s First Amendment challenge, the Court found that such ads

are not protected by the First Amendment, even though the ads were

discriminatory only by “implication” and not “overtly.” See id. at 387-

89.

Similarly, the Times’ argument that it is merely the passive

publisher o f the content-based decisions of third parties has already been

squarely rejected. A “newspaper may not defend a libel suit on the ground

that the falsely defamatory statements are not its own,” and this argument

has no greater force in the commercial speech or discrimination context.

See id. at 386.

Finally, there is no authority for petitioner’s argument that the

ordinary reader standard adopted by the Second Circuit is too vague under

the First Amendment. See Petition at 19. Indeed, just last year, the Court

held that even with respect to a newspaper editorial, the legal standard for

determining whether the newspaper is liable for defamatory opinions is

“whether reasonable readers would have actually interpreted the statement

as implying defamatory facts.” Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co., 110 S.

Cl 2695, 2710 n.3 (1990) (Brennan, J., dissenting) (stating unanimous

aspect o f decision); id. at 2707 (majority opinion) (test is whether

statement “ reasonably implies” defamatory facts or contains “false

10

connotations”). This reasonable reader standard, which newspapers must

follow in publishing opinions about matters of public concern, is no more

standardless or difficult to apply than the ordinary reader standard applied

by the Second Circuit to determine liability for racially discriminatory

advertising.

H . R EV IEW O F TH E IN TER LO C U TO R Y D ECISIO N

BELO W IS PR EM A TU RE

As the Second Circuit merely held that respondents’ complaint is

sufficient to withstand a threshold motion to dismiss, there is no reason

for the Court to consider this case at this time. The petition also raises

constitutional issues which should not be ruled upon because the case can

be resolved on other grounds. See, e.g.. Rescue Army v. Municipal Court

o f Los Angeles, 331 U.S. 549,568-69 (1947); Ashwanderv. TV A, 297 U.S.

288, 346 (1936) (Brandeis, J., concurring).

Reluctance to review interlocutory decisions is a time-honored

principle followed by the Court in exercising its discretion to grant

certiorari. Absent “extraordinary inconvenience and embarrassment in

the conduct o f the cause,” the Court has traditionally declined to review

decisions that do not finally resolve the litigation. American Constr. Co.

v. Jacksonville, Tampa, and Key West Ry. Co., 148 U.S. 372,384 (1893).

Lack of finality is often by itself “sufficient ground for the denial of the

application.” Hamilton-Brown Shoe Co. v. Wolf Bros. & Co., 240 U.S.

251 ,258 (1916).

Finally, the Court should deny certiorari in this case to give other

courts an opportunity to rule in similar pending cases. See Housing

Opportunities Made Equal v. The Cincinnati Enquirer, Inc., 731 F. Supp.

801 (S.D. Ohio 1990), appeal pending, No. 90-3176 (6th Cir.); Ragin v.

Steiner, Clateman & Assocs., Inc., 714 F. Supp. 709 (S.D.N.Y. 1989)

(trial to commence in Nov. 1991). Even if there were ultimately a need

for the Court to address the issues raised by petitioner, the Court should

allow the lower courts time to address those issues first. See, e.g.,

Maryland v. Baltimore Radio Show, Inc., 338 U.S. 912, 918 (1950)

(Frankfurter, J„ commenting on a denial o f certiorari).

11

CO NCLUSIO N

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for a writ of certiorari

should be denied.

Dated: New York, New York

July 22, 1991

Respectfully submitted,

Ju l iu s L . C h a m b e r s

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

K e r r y A l a n S c a n l o n

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

N A A C P L e g a l D e fe n se a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , I n c .

/s / K athleen M . C om frey

K a t h l e e n M . C o m fr e y

Counsel o f Record

K a r e n M. C rupi

S h e a r m a n & S ter lin g

153 East 53rd Street

New York, New York 10022

(212) 848-4000

Counsel for Respondents

APPENDIX

lb

‘The ‘Washington Tost

1150 15th Street, N.W.

WASHINGTON, D.C. 20071

(202)334-6000

BOISEFEUILLET JONES, JR.

Vice President and Counsel

(202) 334-7141

August 4, 1986

Kerry Alan Scanlon, Esq.

Washington Lawyers Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W., Suite 450

Washington, D.C. 20005

Dear Kerry:

This letter sets forth the agreement we have reached in settlement

o f the real estate display advertising claims you have raised on behalf of

the Fair Housing Council of Greater Washington, the Metropolitan

Washington Planning & Housing Association, Inc., and Girardeau A.

Spann.

By August 5, 1986, the Post will issue a policy statement

regarding its commitment to nondiscriminatory equal housing opportunity

in real estate advertising. The policy will be sent to all advertisers who

placed real estate display advertisements during the first six months of

1986 and will be sent to all new advertisers who place real estate display

advertisements in The Post during the next three years. The policy will

specify the following positions on logos and human models, to become

effective as o f the September 5, 1986 editions.

Logos

Advertisements o f four column inches or larger must display the

Equal Housing Opportunity logo, which includes the “Equal Housing

Opportunity” slogan, published at24 C.F.R. § 109.30(a), or the substance

o f the following statement:

2b

“We are pledged to the letter and spirit o f U.S. policy for

the achievement of equal housing opportunity throughout

the Nation. We encourage and support an affirmative

advertising and marketing program in which there are no

barriers to obtaining housing because of race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin.”

The logo in such advertisements must meet the following minimum

size requirements:

i. 2" x 2" in half page or larger;

ii. 1" x 1" in one-eighth page to half page;

iii. 1/2" x 1/2" in four column inches to one-eighth

page.

All logos or statements must be clearly visible, and must be

printed in display face roughly equivalent to other print found in the

advertisement.

The Post will include in its Saturday real estate display advertising

section the substance of the following Equal Housing Opportunity

statement:

“All real estate advertised herein is subject to the Federal

Fair Housing Act of 1968 which makes it illegal to

indicate “any preference, limitations, or discrimination

based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin, or

an intention to make any such preferences, limitations, or

discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or

national origin, or an intention to make any such

preferences, limitation, or discrimination.”

“We will not knowingly accept any advertising for real

estate which violates the law. All dwellings advertised

are available on an equal opportunity basis.”

Human Models

Real estate display advertisements that depict human models

who are racially identifiable, excepting only those humans obviously not

3b

depicted as residents or potential residents, should reflect an approximate

cross-section o f the greater Washington, D.C. metropolitan area population,

and to that goal must meet the following criteria:

1. In advertisements for a particular residential development or

complex that depict a single model, one or two couples, or a single family,

at least one out of every four advertisements are to include one or more

blacks. (For advertisements for multiple developments or no particular

development, this criterion will be applied according to the firm, owner

or developer placing the ads.)

2. In each advertisement depicting three or more individuals,

not falling within the first category, blacks must constitute at least 25%

of the human models — i.e., one black in a group of three or four models,

two blacks in groups o f five to eight models, three blacks in group of nine

to 12 models, etc.

3. Black models must be depicted in a manner and setting

generally comparable to the depiction o f white models in any particular

advertisement or series of advertisements placed by the same advertiser.

* * *

Recordkeeping

To carry out the above policy, The Post will perform the following

recordkeeping. Beginning August 30, 1986 and for a period of three

years, The Post through its real estate advertising sales manager will keep

three copies o f each Saturday real estate display section (or o f whatever

day of the week The Post runs the real estate display section if not

Saturdays) and of each “W eekend” section. On a weekly basis during this

period The Post will record data on the attached form regarding real estate

display ads of four column inches in size or larger appearing in the section.

Every four months during this period The Post will provide a summary of

the weekly data to you (or other designated representative o f your clients).

Upon request, The Post will make available the copies o f the real estate

and W eekend sections it has saved and the weekly data forms it has

compiled.

4b

Enforcement

The Post will make a good-faith effort to enforce the policy and

will give prompt written notice to any advertiser who materially fails to

comply with the policy as soon as such non-compliance is discovered by

The Post. This notice will also inform advertisers that they must comply

with the policy, and that The Post will enforce such compliance. If an

advertiser again fails to comply at any time within the three months after

the notice, The Post will again write the advertiser and state that the next

ad containing human models must include one or more blacks and that any

subsequent ads must conform with The Post’s policy. In the case of

category 2 non-compliance, The Post will also make personal contact

with the advertiser to emphasize that the non-complying ad must not be

used again. If the non-complying advertiser fails to comply with the

notices at any time during the next six months, The Post will notify you

o f that fact and will either prohibit the advertiser from using human

models in its real estate display advertisements or require pre-clearance

of such ads with The Post until compliance (including adequate black

human models to correct for the past non-com pliance) has been

demonstrated for a period o f three months.

The Post will maintain a file of copies of all notices mailed to non

complying advertisers and will permit you or your representative to

inspect that file upon request. The Post will also place responsibility for

monitoring compliance in a senior member o f its staff. If your clients have

questions or concerns about The Post’s monitoring or enforcement

efforts, including any apparent efforts by advertisers to circumvent the

policy, we will be glad to meet with you promptly. You or your clients

also agree to meet with The Post to resolve questions or concerns if The

Post’s policy, monitoring, or enforcement efforts have unreasonable

consequences.

It is my understanding that The Post’s policy, if implemented as

set forth in this letter, will satisfy the concerns of your clients, the Fair

Housing Council o f Greater Washington, the Metropolitan Washington

Planning & Housing Association, Inc., and Girardeau Spann. In

consideration for the implementation of the policy and requirements

described in this letter, your clients agree not to pursue any legal or other

action against The Post regarding the publication o f logos and human

models in real estate display ads published in The Post to date. It is also

5b

my understanding that you and your clients are working with Journal

Newspapers, Inc. so that it will enforce a similar policy. The Post

understands that if in any material way it fails to act in accordance with

the terms o f this letter, your clients will be free to institute litigation to

enforce this agreement.

The initial term o f this agreement is three years, and it will be

extended for an additional two years if during the 12-month period after

the initial term ends the number of black human models appearing in The

Post’s real estate display ads is less than 20% of the total number o f such

models. The limited term of this agreement does not mean that thereafter

The Post intends to be less committed to a policy o f non-discriminatory

real estate display advertising and to the principle that such advertising

should be representative of the racial makeup of the greater Washington,

D.C. metropolitan area.

Sincerely,

/s/ Bo Jones______

Boisfeuillet Jones, Jr.

Agreed:

/s/ Kerry Alan Scanlon________________

Kerry Alan Scanlon, Esq.

W ashington Lawyers’ Committee

for Civil Rights Under Law

on behalf o f The Fair Housing Council of

Greater Washington and The Metropolitan

Planing & Housing Association, Inc., and

Girardeau A. Spann

The Washington Post - Real Estate Display Section Date of Edition

Advtr. (Dev. or

firm/owner/

developer)

Logo / Statement Human Models Location

Conf. Non-Conf. None Cate. 1 Cate. 2 DC Alex Arl. Frfx Mtgy PG Ot.

#Wh #Blk #Wh #BUt

Developments or Firms/Owners/Developers Advertising in The Washington Post

For 3 months period from

Advtr.

# of

Ads

# w/

Conf.

Logos

# w/

Non. Conf.

Logos

# w/

no

Logos Cate. 1 Ads

Category 1 Ads

Cate. 2 Ads

Category 2 Ads

#Blk #W h #Blk #Wh

Noncompliance Notices Sent

For 3 month period from

Advertiser 1st or 2nd Notice Date and Category of Non-Complying Ad Date of Notice

9b

'The 'W ashington (Post

1150 15th Street, N.W.

WASHINGTON, D.C. 20071

(202)334-6000

JAMES E. CUMMINS

SALES MANAGER

REAL ESTATE

334-7639

August 5, 1986

Dear Advertiser:

This letter is to inform you that The Washington Post is adopting

a policy with very specific standards regarding human models and logos/

statements in real estate display advertising. The policy is attached and

will become effective as of the Friday, September 5,1986, editions o f the

newspaper.

The Post is adopting specific standards at this time because

experience has shown that a policy of general principles alone has not

worked well.

We approach this problem with an awareness of the history of

housing advertising in the Washington, D.C. area. Until the early 1960s

newspapers here carried separate “colored” listings in the classified

section, and they allowed advertisements with explicit or subtle racial

preferences during the 1960s.

In 1973, in response to complaints, The Post took affirmative

measures to ensure that advertisements connoted non-discriminatory

housing opportunity. The real estate department was instructed that

human models in real estate display advertising must not have the effect

o f signaling an intent to practice racial discrimination, and accordingly

that models used in a series of such advertisements could not be solely of

one race, but rather must contain a mixture so as to negate any possible

mistaken inference of racial preferment. Advertisers were encouraged to

make prominent use of the equal housing opportunity logo, as many

10b

already did. The Post itself placed its Equal Housing Opportunity

statement in a more prominent position in the display advertising section

and included the statement with greater frequency and intervals throughout

the section.

Since then, The Post has on occasion called advertisers’ attention

to the human model provisions of H.U.D.’s “Fair Housing Guidelines,”

which state that models should reasonably represent majority and minority

groups in the metropolitan area.

Recently, however, representatives of fair housing organizations

which have monitored display advertising in The Post during the last year

called our attention to the fact that the use of black human models has not

been close to proportionate to this group’s representation in the D.C.

metropolitan area. These organizations also found that few ads contained

Equal Housing Opportunity logos or statements conforming with the

standards suggested by H.U.D.’s guidelines. The purpose of the logos

and statements, of course, is to inform the reader that property is available

to persons regardless of race, etc.

As a result of these statistics, The Post agreed with the fair

housing organizations that specific standards were now necessary, and

that The Post would monitor compliance by advertisers. While there may

be differing opinions on what the specific standards ought to be, I think

people will agree that those adopted by The Post are reasonable. If you

have any questions regarding the policy, you should not hesitate to get in

touch with me or others in the real estate display department.

Sincerely,

/s/ James E. Cummins

James E. Cummins

Attachment

l ib

The Washington Post Policy on Human Models and Logos

In Real Estate Display Advertisements

Human Models

Real estate display advertisements that depict human models

who are racially identifiable, excepting only those humans obviously not

depicted as residents or potential residents, should reflect an approximate

cross-section of the greater Washington, D.C. metropolitan area population,

and to that goal must meet the following criteria:

1. In advertisements for a particular residential development or

complex that depict a single model, one or two couples, o ra single family,

at least one out of every four advertisements are to include one or more

blacks. (For advertisements for multiple developments, or no particular

development, this criterion will be applied according to the firm, owner

or developer placing the ads.)

2. In each advertisement depicting three or more individuals,

not falling within the first category, blacks must constitute at least 25%

of the human models — i.e., one black in a group o f three or four models,

two blacks in groups o f five to eight models, three blacks in group of nine

to 12 models, etc.

3. Black models must be depicted in a manner and setting

generally comparable to the depiction of white models in any particular

advertisement or series of advertisements placed by the same advertiser.

Logos

Advertisements o f four column inches or larger must display the

Equal Housing Oopportunity logo, which includes the “Equal Housing

Opportunity” slogan, published at24C .F.R . § 109.30(a), or the substance

o f the following statement:

“We are pledged to the letter and spirit of U.S. policy for

the achievement o f equal housing opportunity throughout

the Nation. We encourage and support an affirmative

advertising and marketing program in which there are no

barriers to obtaining housing because of race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin.”

12b

The logo in such advertisements must meet the following minimum

size requirements:

i. 2" x 2" in half page or larger;

ii. 1" x 1" in one-eighth page to half page;

iii. 1/2" x 1/2" in four column inches to one-eighth

page.

All logos or statements must be clearly visible, and must be

printed in display face roughly equivalent to other print found in the

advertisement.

8/4/86

13b

THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY

229 West 43 Street

New York 10036

Dear Advertiser:

It is a cornerstone o f The New York Tim es advertising

acceptability policy that discriminatory advertising is unacceptable for

publication. The Times also aware that discriminatory policies may at

times be communicated in subtle ways — ways that the most careful

advertising review procedures might not catch.

The Times has recently received complaints that certain real

estate advertising published in The Times does not comply with federal

and state fair housing laws and regulations.

For example, it has been pointed out that some ads do not carry

the “Equal Housing Opportunity” tag line, while other ads appear not to

be in compliance with the regulations’ guidelines for use of professional

models.

W hile it is not the intention o f The Times to usurp the role of

government agencies in enforcing the law, we steadfastly believe that our

policies must reflect both the requirement and spirit o f the fair housing

laws.

Accordingly, The Times has taken the following steps:

• With our 1988 Classified Rate cards, The Times has included

a reminder and reference to federal Fair Housing Act regulations.

Additionally, The Tim es’s advertising acceptability standards, which

already prohibit discriminatory ads has been amended to incorporate by

specific reference the requirements of the Fair Housing Act and other

laws against discrimination.

• All real estate advertising contracts will also refer advertisers

to federal and state legal requirements, as well as to The Tim es’s

acceptability standards. We urge all real estate advertisers and advertising

14b

agencies to review the Fair Housing Act regulations to ensure that their

ads are in compliance with both the letter and spirit o f the law.

• Effective January 1,1988, The Times will require that all real

estate display ads include the “Equal Housing Opportunity” tag line

recommended by the federal regulations. Ads which fail to include this

statement will be rejected.

• Finally, we intend to notify our fellow publishers in the New

York Metropolitan area of the foregoing and will urge them to adopt

similar measures.

While you have already received the 1988 rate card, we are

enclosing an additional rate card to bring to your attention its reminder

and reference to the federal Fair Housing Act requirements.

We know that you join us in the desire to make fair housing

practices a reality in the New York Metropolitan area.

/s/ Robert P. Smith_______________

Robert P. Smith

Advertising Acceptability Manager

15b

STANDARDS OF ADVERTISING ACCEPTABILITY

THE NEW YORK TIMES

The following describes some of the kinds of advertising

which The Times will not accept:

1. Generally

• Advertisements which contains fraudulent, deceptive,

or misleading statements or illustrations.

• Attacks of a personal character.

• Advertisements that are overly competitive or that refer

abusively to the goods or services o f others.

2. Investments

Advertisements which do not comply with applicable federal,

state and local laws and regulations.

3. Occult Pursuits

Advertisements for fortune telling, dream interpretations and

individual horoscopes.

4. Foreign Languages

Advertisem ents in a foreign language (unless an English

translation is included) except in special circumstances and when a

summary o f the advertisement in English is included.

5. Discrimination

A dvertisem ents w hich fail to com ply w ith the express

requirements o f federal and state laws against discrimination, including

Title VII and the Fair Housing Act, or which otherwise discriminate on

grounds o f race, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital status or

disability.

16b

6. Offensive to Good Taste

Indecent, vulgar, suggestive or other advertising that, in the

opinion o f The Times, may be offensive to good taste.

This list is not intended to include all the types o f advertisements

unacceptable to The Times. Generally speaking, any other advertising

that may cause financial loss to the reader, or injury to his health, or loss

of his confidence in reputable advertising and ethical business practices

is unacceptable.

RETAIL ADVERTISING

1. Competitive Claims

A. Statements or representations which disparage the goods,

price, service, business methods or advertising o f any

competitor by name are not acceptable.

B. Statements which make or imply unsupportable claims

that an advertiser will undersell competitors are not

acceptable.