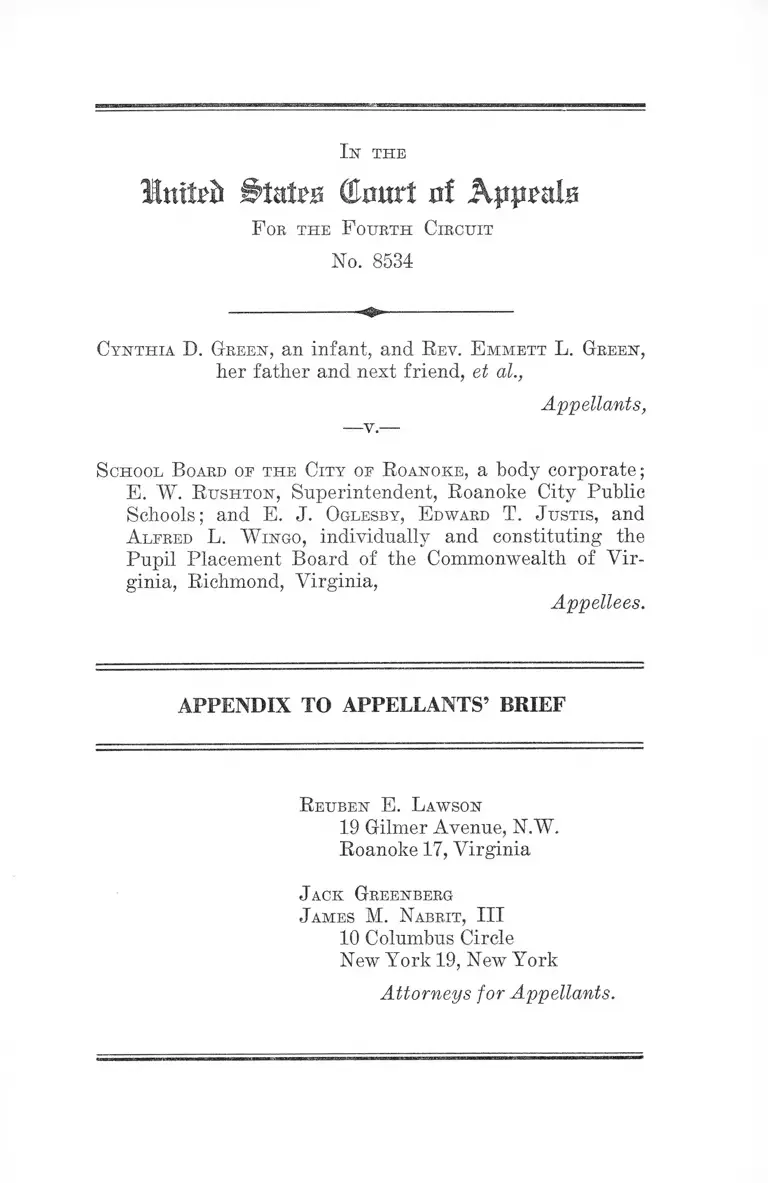

Green v. City of Roanoke School Board Appendix to Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Green v. City of Roanoke School Board Appendix to Appellants' Brief, 1961. 21f90c33-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a4d99c20-90c7-4a73-9441-1e491a4b5882/green-v-city-of-roanoke-school-board-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed March 05, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

In itsb (Urntrt nt Appmis

F or t h e F o u rth C ircu it

No. 8534

Cy n t h ia D. Gr e e n , an infant, and R ev. E m m ett L. Gr e e n ,

her father and next friend, et al.,

Appellants,

S chool B oard op t h e C ity of R oanoke, a body corporate;

E. W. R u sh t o n , Superintendent, Roanoke City Public

Schools; and E. J . Oglesby, E dward T. J u st is , and

A lfred L. W ing o , individually and constituting the

Pupil Placement Board of the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia, Richmond, Virginia,

Appellees.

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

R e u b e n E . L awson

19 Gilmer Avenue, N.W.

Roanoke 17, Virginia

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants.

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Relevant Docket Entries ........................................... la

Complaint ...................................... -.............................. 3a

Motion to Dismiss and Answer ............. ................... 19a

Answer of the Pupil Placement B oard ..................... 24a

Excerpts From Transcript of Trial, May 25, 26, 1961 27a

Plaintiffs’ Witnesses:

E. W. Rushton

Direct...................................................... 31a

Dorothy L. Gfibney

Direct...................................................... 79a

Recalled—-

Direct........... .................................. 114a

B. S. Hilton

Direct............................................... 87a

Recalled—•

Redirect.................................................... 191a

Dr. James A. Bayton

Direct...................................................... 92a

Redirect............................. 110a

Ernest J. Oglesby

Direct.............................. ...................... - 134a

Cross .......................................... — ...... 154a

Redirect........................................... -........ 155a

By the Court......................................... 156a

11

PAGE

Defendants’ Witness:

A. L. Wingo

By the Court........... ................................ 161a

Cross ...................................................... 177a

Exhibits Introduced at Trial ...................................... 193a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit A ....... 193a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit H ........ 197a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit J ............................................. 200a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit I ....... 201a

Memorandum Opinion................................................. 202a

Plaintiffs’ Objections to Report of Pupil Placement

Board.......... .............................................................. 212a

Judgment ..................................................................... 216a

Notice of Appeal.......................................................... 220a

R elevan t D ocket E n tries

1960

Aug. 20

Aug. 23

Sept. 12

Sept. 14

Nov- 30

1961

May 22

Filed complaint, motion for interlocutory injunc

tion, and plaintiffs’ statement of points and au

thorities in support of motion for an interlocu

tory injunction. # # #

# # #

Hearing by Judge John Paul on plaintiffs’ mo

tion for interlocutory injunction, and defendant

Roanoke School Board’s oral motion for dis

missal.

Entered orders this day denying plaintiff’s mo

tion for interlocutory injunction and defendant

Roanoke School Board’s oral motion for dis

missal. Copies cert, to counsel.

Filed answer and motion to dismiss on behalf

of the School Board of the City of Roanoke and

E. W. Rushton, Superintendent, with certificate

of service noted thereon.

Received answer of Pupil Placement Board, with

cert, of service noted thereon, and the time for

filing same having expired, endorsed same “prof

fered for filing September 14, 1960.”

Filed designation by Chief Judge Simon E.

Sobeloff of Oren R. Lewis to hear this action.

# * *

Filed depositions of Dorothy L. Gibboney, E. W.

Rushton, B. S. Hilton, J. P. Cruickshank and

Richard P. Yie on behalf of plaintiffs in sealed

envelope. Deposition marked “proffered for fil

ing May 25, 1961 by Leigh B. Hanes, Jr., Clerk.”

2a

Relevant Docket Entries

May 25 Trial by court—continued to May 26, 1961.

May 26 Trial by court concluded—order entered on trial

proceedings, and exhibits received.

# m *

July 10 Filed memorandum opinion.

Sept. 8 Filed plaintiffs’ objections to report of Pupil

Placement Board, copy only.

Oct. 4 Order of judgment entered, dated October 4, 1961

—copies certified to counsel of record (civil order

book #18, page 44).

Nov. 1 Filed plaintiffs’ notice of appeal from the judg

ment entered in this cause on October 4, 1961,

denying injunctive relief. * * *

* * #

3a

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe t h e W estern D istrict of V irg in ia

R oanoke D ivision

Civil Action No, 1093;

C om plaint

C y n th ia D. Gr e e n , P aula L, G reen and A r len e Y. Gr e e n ,

infants by Rev. Emmett L. Green, their father and

next friend,

D e n n is G ordon L ogan, an infant by Farris R. Logan and

Dorothy Logan, his father and mother and next friend,

W alter L. W h ea to n , III, an infant by Walter S. Wheaton,

Jr., his father and next friend,

M elvin D. F r a n k l in , J r., an infant by Dollie L. Franklin

and Melvin D. Franklin, his mother and father and next

friend,

George W. W arren , B everly E. W arren and Carolyn J.

W arren , infants b y George Willie Warren and Pearl

T. Warren their father and mother and next friend,

T heodore B row n , an infant b y Emma Brown his mother

and next friend,

J ack T. L ong, J r., B renson E. L ong and S ylvia E. L ong,

infants by Jack T. Long and Elizabeth Long their father

and mother and next friend,

L inda L. A nderson and M elvin C. A nderson , III, infants

by Melvin C. Anderson and Elsie A. Anderson their

father and mother and next friend,

C urtis L. S trawbridge, an infant by Purcell Strawbridge

and Marceline Strawbridge his father and mother and

next friend,

4a

Complaint

M arzennia G ayle M oore, an infant b y Zennie Moore, her

mother and next friend,

N ancy Lee M artin and P h y llis D ia n e M a rtin , infants

by Vernard Martin, their mother and next friend,

J erome E ric Groan, an infant by James A. Croan, his

father and next friend,

C h r ist o ph e r N. K aiser, an infant by Louise E. Kaiser and

Napoleon D. Kaiser, his mother and father and next

friend,

B everley A r len e C olem an , an infant by Jessie Coleman,

her mother and next friend,

N a n n ie D orethea R oberson, R oberta L ouise R oberson, and

R obert H arry R oberson, infants by Lucille Roberson,

their mother and next friend,

C ttart.e s H. P e n n ix , an infant b y Richard H. Pennix his

father and next friend,

C harlotte I nez W illia m s , an infant by Charles Williams

her father and next friend,

R obert Long, an infant b y Janies Long his father and

next friend,

and

E m m ett L . Gr e e n , F arris R . L ogan, D orothy L ogan,

W alter S. W h ea to n , J r., D ollie L . F r a n k l in , M elvin

D. F r a n k l in , G eorge W ill ie W arren , P earl T. W arren ,

E m m a B row n , J ack T. L ong, E lizabeth L ong, M elvin

C. A nderson , E lsie A . A nderson , P urcell S trawbridge,

M arceline S trawbridge, Z e n n ie M oore, V ernard M ar

t in , J ames A . Croan, L ouise E . K aiser, N apoleon D .

5a

Complaint

K aiser, J essie Colem an , L u cille R oberson, R ichard H .

P e n n ix , C harles W illia m s , J ames L ong,

Plaintiffs,

— Yg—

S chool B oard of t h e C ity of R oanoke, a body corporate,

Roanoke, Virginia,

and

E . W . R u sh t o n , Superintendent, Roanoke City Public

Schools,

and

E. J. Oglesby, E dward T. J u stis , a n d A lfred L. W ingo ,

in d iv id u a lly a n d c o n s ti tu tin g the P u p il P lacem ent

B oard of t h e C o m m onw ealth of V irg in ia , R ich m o n d ,

V ir g in ia .

1. (a) Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title

28, United States Code, Section 1331. This action arises

under Article 1, Section 8, and the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Constitution of the United States, Section 1, and

under the Act of Congress, Revised Statutes, Section 1977,

derived from the Act of May 31, 1870, Chapter 114, Section

16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title 42, United States Code, Section

1981), as hereafter more fully appears. The matter in

controversy, exclusive of interest and cost, exceeds the

sum of Ten Thousand Dollars ($10,000.00).

(b) Jurisdiction is further invoked under Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1343. This action is authorized

by the Act of Congress, Revised Statutes, Section 1979,

derived from the Act of April 20, 1871, Chapter 22, Sec

6a

tion 1, 17 Stat. 13 (Title 42, United States Code, Section

1983), to be commended by any citizen of the United States

or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to redress

the deprivation under color of state law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom or usage of rights, privileges and im

munities secured by the fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States and by the Act of Congress,

revised Statutes, Section 1977, derived from the Act of

May 31, 1870, Chapter 114, Section 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title

42, United States Code, Section 1981), providing for the

equal rights of citizens and of all persons within the juris

diction of the United States as hereafter more fully appears.

2. Infant plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens of the

United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

are residents of and domiciled in the City of Roanoke. They

are within the age limits of eligibility to attend the public

schools of the said City and possess all qualifications and

satisfy all requirements for admission to the public schools

of said City.

3. Adult plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens of the United

States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and are resi

dents of and domiciled in the City of Roanoke. They are

parents or guardians of the infant plaintiffs, and are

taxpayers of the United States and of the said Common

wealth and City. All adult plaintiffs having control or

charge of any unexempted child who has reached his seventh

birthday and has not passed his sixteenth birthday are re

quired to send said child to attend school or to receive in

struction (Code of Virginia, 1950, Title 22, Chapter 12,

Article 4, Sections 22-251 to 22-256).

Complaint

Complaint

4. Plaintiffs bring this action in their own behalf and,

there being common questions of law and fact affecting the

rights of all other Negro children attending the public

schools of the City of Roanoke and their respective parents

and guardians, similarly situated and affected with refer

ence to the matters here involved, who are so numerous as

to make it impracticable to bring all before the Court,

and a common relief being sought, as will hereinafter more

fully appear, bring this action, pursuant to Rule 23(a)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, as a class action

also on behalf of all other Negro children attending the

public schools of the City of Roanoke and their respective

parents and guardians similarly situated and affected with

reference to the matters here involved.

5. Defendant The City School Board of The City of

Roanoke, Virginia, exists pursuant to the Constitution and

laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia as an administrative

department of the Commonwealth of Virginia, discharging

governmental functions (Constitution of Virginia, Article

IX, Section 133, Code of Virginia, 1950, Title 22, Chapter

1, Sections 22-1, 22-2, 22-5 to 22-9.3, Chapter 6, Article 1,

Sections 22-45 to 22-58, Chapter 6, Article 2, Sections 22-59

to 22-79, Chapters 7 to 15, Sections 22-101 to 22-330) ; and

is declared by law to be a body corporate (Code of Virginia,

1950, Chapter 6, Article 2, Section 22-63).

6. Defendant E. W. Rushton is Superintendent of

Schools for Roanoke City, Virginia. He holds office pur

suant to the Constitution and Laws of the Commonwealth

of Virginia as administrative officer of the Public free

school system of Virginia (Constitution of Virginia, Article

IX, Section 133; Code of Virginia, 1950, Title 22, Chapter 1,

8a

Sections 22-1, 22-2, 22-5 to 22-9.3, Chapter 4, Sections 22-31

to 22-40, Chapter 6 to 15, Sections 22-45 to 22-330). He is

under the authority, supervision and control of, and acts

pursuant to, the orders, policies, practices, customs and

usages of defendant The School Board of the City of

Roanoke. He is made a defendant herein in his official

capacity.

7. The Commonwealth of Virginia has declared public

education a state function. The Constitution of Virginia,

Article IX, Section 129, provides:

“Free schools to be maintained. The General As

sembly shall establish and maintain an efficient system

of public free schools throughout the State.”

Pursuant to this mandate, the General Assemblv of

Virginia has established a system of public free schools

in the Commonwealth of Virginia according to a plan set

out in Title 22, Chapter 1 to 15, inclusive, of the Code of

Virginia, 1950. The establishment, maintenance and ad

ministration of the public school system of Virginia is

vested in a State Board of Education, a Superintendent

of Public Instruction, Division Superintendent of Schools,

and County, City and Town School Boards (Constitution

of Virginia, Article IX, Sections 130-133; Code of Virginia,

1950, Title 22, Chapter 1, Section 22-2).

8. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United

States declared the principle that State-imposed racial

segregation is violative of the Fourteenth Amendment of

the Constitution of the United States. Pursuant to said

decision, as recognized and applied by this Court, formal

applications have heretofore been made to defendants in

Complaint

9a

behalf of infant plaintiffs for admission, enrollment and

education in designated free schools under the jurisdiction

and control of defendants, to which said infant plaintiffs,

but for the fact that they are Negroes, in all other respects

are qualified for admission and enrollment. However, de

fendants and each of them, have failed and refused to act,

favorably upon these applications and purposefully, will

fully, and deliberately continue to pursue and enforce the

aforesaid policy, practice, custom and usage of racial segre

gation against infant plaintiffs and all other children

similarly situated and affected.

9. Defendants will continue to pursue and enforce against

plaintiffs, and all other children similarly situated, the

policy, practice, custom and usage specified in Paragraph 8,

supra, and will continue to deny to infant Negro Plaintiff’s

admission, enrollment or education in any public school

under defendant’s supervision and control operated for

children who are not Negroes, unless restrained and en

joined by this Court from so doing.

10. The public schools of the City of Roanoke, Virginia

are under the control and supervision of defendants acting

as administrative agencies of the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia. Defendant, The School Board of the City of Roanoke,

Virginia, is empowered and required to establish and main

tain an efficient system of public free schools in said City

(Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, Sections 22-1, 22-5);

to provide suitable and proper school buildings, furniture

and equipment, and to maintain, manage and control the

same (Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, Section 22-97);

to determine the studies to be pursued, the methods of

teaching, and the government to be employed in the schools

Complaint

10a

(Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, Sections 22-97, 22-

233 to 22-240.1); to employ teachers (Code of Virginia,

1950, as amended Sections 22-203); to provide for the

transportation of pupils (Code of Virginia, 1950, as

amended, Sections 22-276 to 22-277, 22-282 to 22-294); to

enforce the school laws (Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended

Section 22-97); and to perform numerous other duties,

activities and functions essential to the establishment, main

tenance and operation of the schools of said City (Code of

Virginia, 1950, as amended, Sections 22-1 to 22-10, 22-30 to

22-44, 22-45 to 22-55, 22-57 to 22-58, 22-89 to 22-100, 22-101

to 22-166, 22-188.3 to 22-210, 22-212 to 22-246, 22-248 to

22-277, 22-279 to 22-330).

11. Defendants E. J. Oglesby, Edward T. Justis and

Alfred Wingo, constituting the Pupil Placement Board of

the Commonwealth of Virginia, purportedly are invested

with all power of enrollment or placement of pupils in,

and determination of school attendance districts for, the

public schools in Virginia (Code of Virginia, 1950, as

amended, Section 22-232.1), and to perform the numerous

other duties, activities and functions pertaining to the

enrollment or placement of pupils in, and the determination

of school attendance districts for, the public schools of

Virginia (Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, Sections 22-

232.3 to 22-232.4).

12. Each school child who has heretofore attended a

public school and who has not moved from a county, city

or town in which he resided while attending such school is

required to attend the same school which he last attended

until graduation therefrom unless enrolled in a different

school by the Pupil Placement Board (Code of Virginia,

Complaint

11a

1950, as amended, Section 22-232.6). This provision per

petuates the pre-existing requirement, policy, practice,

custom and usage of the Commonwealth of Virginia of

racial segregation in the public schools thereof save as to

such children as may be able, for good cause shown, to

establish an exception thereto by pursuing the procedure

specified in Sections 22-232.8 to 22-232.14.

13. Any child desiring to enter a public school for the

first time, and any child who is graduated from one school

to another within a school division or who transfers to or

within a school division, or any child who desires to enter

a public school after the ending of the session, is required

to apply to the Pupil Placement Board for enrollment and

is required to enroll in such school as the Board deems

proper (Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, Section 22-

232.7), and if aggrieved thereby is required to pursue the

procedure specified by law (Code of Virginia, 1950, as

amended, Sections 22-232.8 to 22-232.14).

14. The procedure specified in Sections 22-232.8 to 22-

232.14 is expensive prolix and inadequate to secure and

protect the rights of plaintiffs, and others similarly situated,

seeking relief from the imposition of segregation require

ments, policies, practices, customs or usages based on race

or color.

15. Defendants endorse, maintain, operate and perpetu

ate separate public schools for Negro and white children,

respectively and deny infant plaintiffs and all other Negro

children because of their race or color, assignment, enroll

ment and admission to an education in any public school

operated for white children, and compel infant plaintiffs

Complaint

12a

and all other Negro children, because of their race or color,

to attend public schools set apart and operated exclusively

for Negro children, pursuant to a policy, practice, custom

and usage of segregating, on the basis of race or color,

all children attending the public schools of said City.

16. Timely application on behalf of each infant plaintiff

was made to defendants for admission for the 1960-61 school

session to a public school in the City of Roanoke, Virginia

heretofore and now maintained for and attended by white

persons only, but defendants, acting pursuant to a policy,

practice, custom and usage of segregating school children

on the basis of race or color, denied the application of each

on account of race or color.

17. The aforesaid action of defendants denies infant

plaintiffs and each of them, and others similarly situated,

their liberty without due process of law and the equal pro

tection of the laws secured by the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Constitution of the United States, Section 1, and

the rights secured by Title 42, United States Code, Section

1981.

18. Defendants will continue to pursue against plaintiffs,

and all other Negro children similarly situated, the policy,

practice, custom and usage hereinbefore specified and will

continue to deny them assignment, admission, enrollment

or education to and in any public school operated for

children residing in said City who are not Negroes unless

plaintiffs are afforded the relief sought herein.

19. Plaintiffs and those similarly situated and affected

are suffering irreparable injury and are threatened with

Complaint

13a

irreparable injury in the future by reason of the policy,

practice, custom and usage and the actions of the defen

dants herein complained of.

W h erefo re , p la in tif fs re s p e c tfu lly p r a y th a t , u p o n th e fil

in g o f th is co m p la in t, a s m a y a p p e a r proper a n d co n v en ien t

to th e Court:

(A) This Court enter judgment declaring that:

(1) The enforcement, operation or execution of Sec

tion 22-232.6 Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended,

which by its terms and in its operation perpetuates

the pre-existing requirement, policy, practice, cus

tom and usage of the Commonwealth of Virginia of

segregating, on the basis of race or color, children

attending the public schools of the Commonwealth,

deprives infant plaintiffs of their rights to non-

segregated education secured by the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of Section 1 of the

Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States;

(2) The enforcement, operation or execution of Sec

tions 22-232.8 to 22-232.14, Code of Virginia, 1950,

as amended, which by their terms and in their

operation require incoming, graduating and trans

ferring public school children to pursue the proce

dure thereby specified, deprives infant plaintiffs of

their rights to non-segregated education secured by

the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States;

(3) The procedure prescribed by Sections 22-232.3

to 22-232.14, Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended,

Complaint

14a

is inadequate to secure and protect the rights of

infant plaintiffs to non-segregated education and

need not be pursued as a condition precedent to

judicial relief from the imposition of segregation

requirements based on race or color; and

(4) The action of defendants E. J. Oglesby, Edward

T. Justis, and Alfred L. Wingo, in administering

and enforcing the provisions of Sections 22-232.5 to

22-232.14, Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, so

as to preserve, perpetuate and effectuate the policy,

practice, custom and usage of assigning children,

including infant plaintiffs, to separate public schools

on the basis of their race or color, deprives infant

plaintiffs of their liberty without due process of

law and equal protection of the laws secured by Sec

tion 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States.

(B) This Court enter a temporary and permanent in

junction restraining and enjoining the defendant

School Board of the City of Roanoke and defendant

E. W. Rushton, Superintendent of Schools of the

City of Roanoke, Virginia and each of them, their

successors in office, and their agents and employees

and all persons in active concert and participation

with them, forthwith, from any and all action that

regulates or affects, on the basis of race or color,

the admission, enrollment or education of the in

fant plaintiffs, or any other Negro child similarly

situated, to and in any public school operated by

the defendants.

(C) In the event defendants request any delay in effect

ing full and immediate compliance with Paragraphs

Complaint

Complaint

(a) and (b), supra, and for bringing about a transi

tion to a school system not operated on the basis of

race, direct defendants to present to this Court,

within ten (10) days a complete and comprehensive

plan, adopted by them which is designed to effect

compliance with Paragraphs (a) and (b), supra, at

the earliest practicable date, and which shall pro

vide for a prompt and reasonable start toward de

segregation of the public schools under defendants’

jurisdiction and control and a systematic and effec

tive method for achieving such desegregation with

all deliberate speed; and that following the filing

of such plan with this Court, a further hearing will

be held in this cause, at which time defendants shall

have the burden of establishing that such delay as is

requested is necessary in the public interest and is

consistent with good faith compliance at the earliest

practicable date. \ C '-’J •

(D) Allow plaintiffs their costs herein, and reasonable

attorney’s fee for their counsel, and grant such

further, other, additional, or alternative relief as

may appear to the Court to be equitable and just

in the premises.

Cy n th ia D. Gre e n , P aula L. Green and

A r len e Y. G r een , infants by Emmett

L. Green, their father and next friend,

D e n n is Gordon L ogan, an infant by Farris

R. Logan and Dorothy Logan, his

father and mother and next friend,

W alter L. W h ea to n , III, an infant by

Walter S. Wheaton, Jr., his father

and next friend,

16a

M elv in 1). F r a n k l in , J r., an infant by

Dollie L. Franklin and Melvin D.

Franklin, his mother and father and

next friend,

George W. W arren , B everly E. W arren ,

and Carolyn J. W arren , infants by

George Willie Warren and Pearl T.

Warren, their father and mother and

next friend,

T heodore B row n , an infant by Emma

Brown his mother and next friend,

J ack T. L ong, J r ., B renson E. L ong and

S ylvia K. L ong, infants by Jack T.

Long and Elizabeth Long, their father

and mother and next friend,

L inda L . A nderson and M elvin C. A nder

son , III, infants b y Melvin C. Ander

son, and Elsie A. Anderson their

father and mother and next friend,

C urtis L. S trawbridge, and infant by Pur

cell Strawbridge and Marceline

Strawbridge his father and mother

and next friend,

M arzennia Gayle M oore, an infant by

Zennie Moore her mother and next

friend,

N ancy L ee M artin and P h y llis D iane

M a rtin , infants b y Yernard Martin

their mother and next friend,

Complaint

17a

J erome E ric Groan, an infant by James

A. Groan bis father and next friend,

Ch r isto ph er N. K aiser, an infant by

Louise E. Kaiser and Napoleon D.

Kaiser, Ms mother and father and

next friend,

B everley A rlen e Colem an , an infant by

Jessie Coleman her mother and next

friend,

N a n n ie D oretha R oberson, R oberta

L ouise R oberson and R obert H arry

R oberson, infants by Lucille Rober

son their mother and next friend,

C harles H. P e n n ix , an infant by Richard

H. Pennix his father and next friend,

C harlotte I n ez W illia m s , an infant by

Charles Williams her father and next

friend,

Robert Long, an infant by James Long

his father and next friend,

E m m ette L . Gr e e n , P arris R. L ogan,

D orothy L ogan, W alter S. W h ea to n ,

J r ., D ollie L . F r a n k l in , M elvin D .

F r a n k l in , George W il l ie W arren ,

P earl T. W arren , E m m a B row n ,

J ack T. L ong, E liza beth L ong, M e l

vin C. A nderson , E lsie A . A nderson ,

P urcell S trawbridge, M arceline

S trawbridge, Z e n n ie M oore, Y ernard

M a rtin , J ames A . Croan, L ouise E .

Complaint

18a

K aiser, N apoleon D. K aiser, J essie

Colem an , L u cille R oberson, R ichard

H. P e n n ix , Charles W illia m s , J ames

L ong,

Complaint

By / s / R eu ben E. L awson

Counsel for Plaintiffs

Reuben E. Lawson

19 Gilmer Avenue, Northwest

Roanoke, Virginia

19a

[ caption o m itted]

Defendants, School Board of the City of Roanoke and

E. W. Rushton, move the court to dismiss the complaint

on the following grounds:

(1) It fails to state a claim upon which relief may be

granted in that there are no allegations of fact supporting

the pleader’s conclusion that the denial of the individual

plaintiffs’ applications for school enrollment was on ac

count of their race or color. The admitted enrollment of

nine Negro pupils in the same schools for which plaintiffs

seek admission negates the allegations of a purpose or

policy to exclude Negroes as a class from these schools.

(2) The individual plaintiffs have failed to exhaust the

administrative remedies provided by Chapter 12, Article

1.1 of the Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended. Their

right to do so still exists, and the remedies are adequate.

(3) In view of the peculiar circumstances of this case,

the court should exercise its discretionary power to decline

jurisdiction and should relegate the plaintiffs to the judicial

review provided in the state courts unless and until it be

comes apparent that the remedies there provided are in

adequate to protect plaintiffs’ constitutional rights.

A nsw er

Without waiving their motion to dismiss, the defendants,

School Board of the City of Roanoke and E. W. Rushton,

answer the complaint with specific reference to the num

bered paragraphs thereof as follows:

M otion to D ism iss and A nsw er

20a

(1) The allegations of paragraph (1) as to jurisdiction

are negated by subsequent allegations in the complaint

which affirmatively show that plaintiffs have failed to ex

haust their administrative remedies in the Pupil Place

ment Board.

(2) The allegations of paragraph (2) are admitted.

(3) The allegations of paragraph (3) insofar as they

are within the knowledge of these defendants are admitted.

(4) The allegations of paragraph (4) are denied. These

defendants specifically allege that these plaintiffs cannot

maintain a class action because they are not representative

of the alleged class and for other reasons hereinafter al

leged.

(5) The allegations of paragraph (5) are admitted.

(6) The allegations of paragraph (6) are admitted.

(7) The allegations of paragraph (7) are admitted.

(8) Defendants admit that infant plaintiffs formally ap

plied for admission to certain public schools in the City

of Roanoke and that they were assigned to other schools

than those applied for. All other allegations of paragraph

(8) are specifically denied and these defendants specifically

allege that the denial of these applications was based on

considerations of educational policy, pupil welfare, and

school administrative needs not related to the infant plain

tiffs’ race or color.

(9) The allegations of paragraph (9) are categorically

denied.

Motion to Dismiss and Answer

21a

(10) The allegations of paragraph (10) are admitted.

(11) The allegations of paragraph (11), exclusive of

implications arising from the use of the word “pur

portedly”, are admitted.

(12) The allegations of the first sentence of paragraph

(12) are admitted. The pleader’s conclusion in the second

sentence thereof is denied.

(13) The allegations of paragraph (13) are admitted.

(14) The allegations of paragraph (14) are denied.

(15) The allegations of paragraph (15) are denied and

are manifestly untrue, as nine Negro children are presently

enrolled in schools predominantly attended by white chil

dren.

(16) These defendants admit, as alleged in paragraph

(16), that infant plaintiffs applied for and were denied

admission to certain public schools in the City of Roanoke.

The pleader’s conclusion that the applications were denied

for the reasons stated in this paragraph is categorically

denied.

(17) Paragraph (17) states an erroneous conclusion of

law and requires no answer.

(18) The allegations of paragraph (18) are denied in

toto.

(19) The allegations of paragraph (19) are denied in

toto.

And for further answer to the complaint these defendants

make the following allegations of fact:

Motion to Dismiss and Answer

22a

(a) For a period of a great many years prior to the

filing of the applications of the infant plaintiffs in May of

1960, the School Board of the City of Roanoke had devoted

itself to a concerted effort to maintain good race relation

ships in the public school system and, pursuant to that

policy, had desegregated teachers’ meetings, the annual

Science Fair, and other school activities. Prior to the filing

of the applications of the infant plaintiffs and 11 other

Negro pupils in May of 1960, no application had thereto

fore been received from any Negro pupils desiring admis

sion to schools predominantly attended by white children.

(b) For many years the School Board of the City of

Roanoke has had a member of the Negro race on the board.

(c) At no time has the School Board or the superinten

dents of the Roanoke City school system adopted a policy

by resolution or otherwise requiring the continued segrega

tion of the races in the public schools.

(d) Of the 39 Negro pupils who applied in May of 1960

for admission to schools previously attended exclusively

by white pupils, the Pupil Placement Board by order en

tered August 15, 1960, granted the application of 9, which

9 Negro pupils are presentely enrolled in three schools

previously attended exclusively by white children. Two of

the remaining 30 Negro pupils seeking admission to the

three schools in question are not parties to the present

suit and are presumptively satisfied with the assignments

made by the Pupil Placement Board. The 28 infant plain

tiffs were assigned to schools attended only by Negro

pupils for reasons based on educational policy, pupil wel

fare and the school administrative needs in the City of

Motion to Dismiss and Answer

23a

Motion to Dismiss and Answer

Roanoke, and these defendants specifically deny that the

applications of the infant plaintiffs, or of any of them,

were denied on account of their race or color.

Respectfully,

R an G. W h it t l e

S idney F. P arham , J r.

Attorneys for the above named defendants

Ran G. Whitte, City Attorney

Municipal Building

Roanoke, Virginia

Sidney F. Parham, Jr.

301 Boxley Building

Roanoke, Virginia

(Certificate of Service omitted.)

24a

[ caption o m itted]

For their joint and several answer to the Complaint in

these proceedings, in so far as advised material and proper,

the defendants E. J. Oglesby, Edward T. Justis and Alfred

L. Wingo say:

1— Strict proof of all of the allegations of paragraphs 1,

2, 3 and 4 of the Complaint is called for.

2— That E. W. Rushton is Division Superintendent of

Schools for the City of Roanoke, Virginia, and that these

defendants constitute the Pupil Placement Board of the

Commonwealth of Virginia, is admitted.

3— All of the other allegations of the Complaint are

denied or constitute a recital of laws and legal conclusions

as to which no answer is required.

F u r t h e r A n sw e r in g :

4— A rule and regulation of the Pupil Placement Board,

generally applicable in all cases and duly adopted with

out regard to race, color or creed, is to the effect that no

pupil shall be transferred from one school to another in

the absence of a favorable recommendation by local school

officials, such rule resting upon the necessity for attaining,

as between these defendants and the local school officials,

orderly administrative proceedings in the operation of the

public schools. There has been no such recommendation in

the case of any of the plaintiffs.

5— These defendants deny that they have enrolled or

placed any of the plaintiffs in, or denied requested transfer

to, public schools on the sole ground of race or color in

contravention of any constitutional rights. These defen

A nsw er o f the P u p il P lacem en t B oard

25a

dants aver, on the contrary, that they have attempted to

enroll each pupil so as to provide for the orderly adminis

tration of public schools, the competent instruction of the

pupils enrolled and the health, safety and general welfare

of such pupils, in strict accordance with law governing and

controlling their actions.

6— They further aver that they are under no obligation

or compunction to promote or to accelerate the mixing* of

the races in the public schools; that no court is constitu

tionally empowered to direct the mixing of the races in the

public schools; that no negro child or white child or child

of any other race has the right to attend a specific school

merely because he is negro or white or a member of any

other race; that in the placing of over 450,000 pupils in the

public schools of the Commonwealth of Virginia, an in

finitesimal number of complaints has been made to this

Board by any person on the ground of racial discrimina

tion ; that voluntary segregation of the races is lawful and

the normal wish of the parents and children of the over

whelming majorities of both the negro and white races is,

in general, in accord with the welfare of the children of

each race, is not the proper concern of any court, and that

until appealed to in a specific case, this Board should not

assume the contrary.

7— F u rth er A n sw erin g , that it is also provided by law

that any party aggrieved by a decision of the Pupil Place

ment Board may file with it a protest, pursuant to which

the Board shall conduct a hearing, consider and decide

each case separately on its merits, which decision enroll

ing such pupil in the school originally designated or in

such other school as shall be deemed proper, shall set

forth the finding upon which such decision is based. That

the burden of proving discrimination in the placement of

Answer of the Pupil Placement Board

26a

pupils on the sole ground of race or color rests upon the

one alleging discrimination; that the welfare of each child,

regardless of race or color, is a factual question to be con

sidered and decided by this Board after complaint is made,

hearing held and full evidence concerning all surrounding

circumstances is made available; and that until such pro

cedure is pursued no person should be in a position to

challenge the action of this Board on the ground that it

has discriminated on the sole ground of race or color. That

notwithstanding ability, readiness and willingness to afford

a prompt and full hearing in accordance with law as to

any specific complaint or grievance, none of the plaintiffs

has filed any protest with the Pupil Placement Board or

any of these defendants with respect to any action taken

by it or them.

W h erefo r e , unless and until this is done and such ad

ministrative remedies have been exhausted, the plaintiffs

should be denied relief.

E . J . O glesby

E dward T. J ustis

A lfred L. W ingo ,

Constituting the Members of the

Pupil Placement Board of the

Commonwealth of Virginia

by Counsel

A. B. S cott, of

Ch r ist ia n , M arks, S cott & S pic er ,

Counsel for Pupil Placement Board

1309 State-Planters Building

Richmond 19, Virginia.

Answer of the Pupil Placement Board

(Certificate of Service omitted.)

E xcerp ts F ro m T ra n sc rip t o f T ria l, May 2 5 , 2 6 , 1961

# # % #

Mr. Lawson: We are the attorneys for all of the Plain

tiffs.

At this point, sir, I would like to move the Court that

paragraph 2 and paragraph 3, which have been admitted

in the Defendants’ answer, he admitted without formal

proof.

Mr. Parham: No objection.

The Court: So ordered.

Mr. Lawson: If Your Honor please, I should also like

to move the Court that all of the exhibits, which have been

agreed to, be admitted, subject to objection at the proper

time, without formal proof, and we would like to list those

now.

Mr. Parham: No objection.

Mr. Lawson: Plaintiffs’ Exhibit A will be a letter of

May 25, accompanied by petition from Reuben Lawson to

the Superintendent of Schools and the Roanoke County

School Board.

—3—

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit B will be a letter dated June 18, 1960,

from Reuben E. Lawson to Superintendent Rushton and

the Roanoke School Board.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit C will be a letter dated June 23, 1960,

from Superintendent Rushton and the Roanoke School

Board.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit D will be three letters dated August

22, 1960, on which are specimens of the letters sent by

the School Board, the local School Board, and by the State

Pupil Placement Board, when denying requests for trans

fers.

— 2—

28a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit E, three similar letters dated August

22, which are specimens of the letters when they are granted

transfers.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit F—F-l through F-39—the Pupil

Placement forms for 39 Negro pupils who sought admis

sion to previously all-white schools prior to the current

school term. This group of 39 includes 28 Plaintiffs, 9

pupils who were Negroes who were admitted to white

schools, and, in addition, the forms of 2 pupils who were

denied admission but did not join in the suit.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit G is a map of the City of Roanoke

which contains on it large colored circles for the location

of the schools and the names and the legend is that schools

marked in red are elementary schools, dark purple—junior

high schools, and the light blue marks high schools.

—4—

Now, Plaintiffs’ Exhibit H is a memorandum dated Feb

ruary 21, 1961, from the Office of the Superintendent,

Roanoke County Public Schools. It contains information,

a good deal of information—the number of classrooms,

capacity, and estimated enrollment for September, 1961.

In addition there was agreed between the parties that

in lieu of extracts of the minutes of the meeting of the

Pupil Placement Board on August 15, 1960, dealing with

the Roanoke applicants, you might insert in the record a

reading of those minutes which took place at the deposi

tion of Mr. Hilton. I might read this now.

The Court: All right. Read it into the record.

Mr. Lawson: “Inasmuch as the local school authorities

of Roanoke City applied, at the request of the Pupil Place

ment Board, criteria and standards dealing with the trans

Motions

29a

fers and assignments of pupils of different races to the

schools of that school division, which are regarded by this

Board as valid and reasonable, and since, through the ap

plication of these criteria and standards, the local school

authorities are not in a position to oppose legally the fol

lowing assignments and transfers, the Pupil Placement

Board takes the following action: Sylvia Moran Long

transferred to Monroe Junior High School; Milton Ran

dolph Long transferred to Melrose Elementary School:

Roswin Cheryl Long transferred to Melrose Elementary

—5—

School; Ula Amber Poindexter transferred to Monroe

Junior High School; Sandra Monroe Wilkins transferred

to Melrose Elementary School; Jane Neff transferred to

Melrose Elementary School; Darwin Poindexter trans

ferred to West End Elementary School; Charles Everett

James transferred to West End Elementary School; Judith

Ann James transferred to West End Elementary School.”

If Your Honor please, I should also like to move the

Court that the depositions which were taken in this mat

ter on March 21, 1961, be admitted to supplement live

testimony.

The Court: On what grounds ?

Mr. Lawson: Well, according to Rule 26, Your Honor,

we feel the purpose was to supplement live testimony.

The Court: Motion is denied.

The Court is of the opinion that the Rule 26 does not

apply where the witnesses are available to testify in per

son, and especially so when the depositions were taken

under the pretrial discovery rule; and, further, that they

do not supplement testimony, that is, have a witness testify

Motions

30a

partly on the stand and partly by deposition. Motion is

denied.

Mr. Lawson: If Tour Honor please, we take the posi

tion that the Rule 26 makes an exception where the parties

who testified are parties to the suit. And that was the—

The Court: The Court disagrees with your construc

tion and if your construction is correct, all Federal trials

— 6—

could be, as far as the parties are concerned, a matter of

deposition, as distinguished from the testimony of the

witnesses. The motion is denied.

Mr. Lawson: Now, if Tour Honor please, we should

also like to make a motion that Tour Honor indicated that

the numbering system would be used relative to these

pupils in lieu of names.

The Court: That is agreeable.

Mr. Parham: All right, sir.

The Court: It is understood, so that the record may

be easily read—and if it hasn’t been done, I think you

ought to do it now. File with the Clerk a list of the persons

with the key numbers so that may be made a part of the

record and when anyone is reading it, they can go back for

identification purposes.

Mr. Parham: All right, sir, we will do that. This will

be an exhibit, I believe?

The Court: I don’t need to make it an exhibit.

* ■31. -Jt-

Motions

31a

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

—7—

E. W. R u s h t o s , called as a witness for the Plaintiffs,

having been duly sworn, testified as follows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Nabrit:

Q. State your name and position with the School Board,

please. A. My name is E. W. Bushton, Superintendent

of School, Roanoke City.

Q. How long have you served in that capacity? A. I

have been Superintendent of Schools since 1953.

-U- -Hr -ilc-fc 'A' 'r,~ Tv* *vr

—8—

# # # # #

Q. When you became Superintendent here in 1953, I as

sume the public schools were racially segregated under

the laws which required that? A. They were.

Q. Do you know what I am talking about when I speak

of the Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 on school segre

gation? A. Tes.

Q. Now, since that time, have you or has your Board

made any public announcements on the subject of segrega-

—9—

tion or desegregation or anything relating to that opinion?

A. You mean by that whether or not we made any public

statement as to the segregated schools or desegregated

schools?

Q. That is correct. A. I do not know. I do not know

whether any name of segregation or desegregation ap

peared in any statement.

32a

Q. Official statement by you as Superintendent or offi

cial statements? A. No, sir. No, sir.

Q. Has there been any formal action by the Board on

the general subject of ending segregation? A. No, sir.

Q. Now, sir, I take it that the Board has never adopted

any plan for desegregation or anything of that character?

A. That is correct.

Q. Has there ever been any discussion of that in official

Board meetings? A. At official school meetings we have

not discussed it.

Q. So that there are no plans, no present plans, for

instituting any type of desegregation program as such?

A. You mean on the local level?

Q. That is right. A. No, sir.

Q. We all know now that here in the City of Roanoke

— 10—

there were nine Negro students admitted to previously all-

white schools last September, 1960. Was that the first

time that there was desegregation here in the system? A.

First time.

Q. Negro and white pupils went to school together? A.

First time.

Q. In the public schools? A. Well, I have only juris

diction over the public schools, only for them, yes.

Q. Is it correct to state that other than that all of the

pupils in the system attend schools separately; that is,

all of the other Negro pupils, except those nine, go to

all-Negro schools and all of the white pupils in the system,

except those in schools with those nine, attend classes with

all-white pupils; is that true? A. Correct.

Q. Now, these nine Negroes who were admitted attend

three schools, don’t they? A. Yes.

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

33a

Q. Melrose— A. Melrose, West End and Monroe Junior

High School.

Q. Now, do you know the number of schools in the sys

tem and the number of high schools and elementary schools ?

A. Yes.

Q. Do you have that with you? A. Yes.

— 11—

Q. I believe that the Exhibit H—

The Court: Mr. Nabrit, I don’t want to cut you

off, but what has this got to do with determining the

question in this case? Isn’t the question in this case

to determine whether or not the petitioners were

improperly denied their transfer applications to

schools in question?

Mr. Nabrit: I would say that is a question in the

case; yes, sir.

The Court: What is the other question in this

suit?

Mr. Nabrit: The additional question presented by

the pleadings, it would seem to me, would be—

The Court: They do not have a plan?

Mr. Nabrit: Essentially that, sir.

The Court: I think we will stipulate that.

Mr. Nabrit: No, sir. That there is no systematic

program for eliminating the various facets of segre

gation which I think I have to show.

The Court: The Court understands that is a fact

and the Defendants are willing to stipulate that the

City of Roanoke, insofar as the local body is con

cerned, has made no plans and does not have any

now for desegregating the schools in any manner

other than what may or may not be operating through

the State Pupil Placement Board; isn’t that correct?

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs-—Direct

— 12—

Mr. Parham: That is correct, sir.

Mr. Nabrit: We will admit that with proviso.

The Court: With the proviso that, so the record

is very complete-—you couldn’t make it more com

plete by going into all of the details, because they

haven’t done it. Now, if they have to, that is an

other story.

.̂ . ^

—13—

̂ ̂ ^

The Court: If you have any reasonable facts that

you want to put in, you state what they are and I

can see if I can get them to stipulate. I t is going to

save time. If you want to know how many pupils

in the school are colored and white, ask if that is

correct, and they may stipulate, and be a part of

the record.

Mr. Nabrit: Will the local board stipulate that

there are approximately 18,900 or maybe closer to

19,000 pupils in the system and that about between

4000-4100 of those pupils are Negroes?

Mr. Parham : That is correct.

The Court: All right. So stipulated.

Mr. Nabrit: That there are approximately 790

teachers employed in the system and that about 176

of those are Negroes?

Mr. Parham: That is correct.

Mr. Nabrit: That the teachers are assigned on a

segregated basis to this extent that in all-Negro

schools all of the staff—teachers, principals and so

forth—-are Negroes; in the all-white schools all of

35a

the staff personnel are white; in the three schools

where these nine Negroes have been admitted all of

—14—-

the staff—principals and so forth—are white.

Mr. Parham: We will stipulate the fact that you

take out the word segregated; that is where they

are assigned as of now.

The Court: They will stipuate that that is a fact.

Mr. Nabrit: Now, will the Board stipulate that

they employ a system for assigning pupils, the local

authorities do, based on a neighborhood system for

elementary schools and then connected with a feeder

system for junior high schools by which certain

elementary schools feed students to certain junior

high schools which in turn feed students routinely

to certain high schools; that the school system is

divided into six sections in this feeder number six

which are indicated on Plaintiffs’ Exhibit H; that

section 2 on Plaintiffs’ Exhibit H is the section for

the Negro schools indicating that the four existing

and one proposed Negro elementary school feed

pupils to Booker T. Washington School and Booker

T. Washington feeds pupils to the Adam School.

The Court: Did they make up that exhibit?

Mr. Nabrit: Yes.

The Court: I am sure they will stipulate.

Mr. Nabrit: I was describing the exhibit, sir.

Mr. Parham: We want to point out that we can

not stipulate that we assign. The assignments are

—15—

made by the Student Placement Board.

The Court: With the exception, that is a descrip

tion of the physical setup and the so-called feeder

system in operation in the City of Roanoke?

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs-—Direct

36a

Mr. Parham: That is entirely correct, sir.

Mr. Nabrit: And that Exhibit H also contains the

estimated enrollment based upon the system for

1961.

The Court: They stipulate all of the information

on that exhibit is correct.

Mr. Parham : All of it is correct.

.B. ,1!. -JfcW W IT IT ®

Mr. Nabrit: Now, will the Board also stipulate

that it is anticipating next September in the all-

white and predominantly white schools there will be

approximately 1300 empty seats; that by mid-term

it is anticipated—second semester—there will be ap-

—16—

proximately 2100 empty seats in the white schools;

and that in the all-Negro schools there will be ap

proximately 400 children in excess of capacity in

September; that the system as a whole expects

about 19,200 pupils in September, 1961, and that the

capacity of the system, estimated on the basis of 30

seats per class room, is about 21,000 pupils?

Mr. Parham: Mr. Nabrit, those figures are new

to me. I don’t know whether we will stipulate to

them or not. Ask Doctor Rushton if he can answer

or if you wait maybe we can.

Mr. Nabrit: Perhaps I can put that question right

now to him.

The Witness: I will try to answer that. That is

assuming that a child is assigned to every seat, that

is correct. During this building program we have

had many changes that had to be made. We had

some double session classes. In the elementary

schools we extended classes. On the high school

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

37a

level we started school earlier in the morning and

went late in the afternoon. That is based on the

number of empty seats, if one child were assigned

to every seat in the City, which, of course, the popu

lation is such that children are not necessarily where

they necessarily are. And then, of course, we can

use a seat more than once. But what you have there,

essentially, is what it is on that basis.

—17—

Mr. Nabrit: These—

The Court: He stated those figures are essentially

correct.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Now, in this connection, is it also true that for next

Fall it is proposed that there will be double sessions—that

double sessions will be necessary in some of the Negro

schools'? A. That is correct. There will be double sessions

in both the white and Negro schools. We do not know when

the schools that are now under construction will be finished

nor when those double sessions will end.

# # # # #

— 20—

# # # # #

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Now, Mr. Superintendent, do you recall the occasion

when, approximately, in May, 1960—May 25, 1960—when

you received a group of applications from Negro students

to attend previously all-white schools? A. Yes.

Q. And, thereafter, several additional applications went

in the next few weeks of the same nature? A. Yes, I have

a record here.

38a

Q. I believe we already have those applications and let-

— 21—

ters in evidence. Can you tell us the sequence of events

and what transpired when you got these applications? That

is, what you did. A. All right. Then going to May 25, 1960,

the Pupil Placement forms for 30 pupils seeking admis

sion into the three nonsegregated schools were then re

ceived and, following that, 9 more came in, 9 more applica

tions, which made a total of 39. And these applications

were accompanied by a petition addressed to the School

Board of the City of Roanoke, the Superintendent of

Schools, the State Pupil Placement Board. And then on the

20th of June, 1960, the petition, together with the 39 Pupil

Placement applications, were then presented to the Roanoke

City School Board.

Q. What date was that? A. That was the 20th of June,

1960.

Q. Yes, sir. A. And then informed the School Board of

this—about receiving these applications—and then they

were forwarded then to the Pupil Placement Board just as

they were received by me.

Q. Was this meeting on the 20th of June, was that an

informal or formal meeting of the Board? A. It was a

formal meeting of the Board at which time—formal meet

ing of the Board, correct.

Q. What else transpired in connection with these ap

plications? A. On following that, then they went, as I

said, to the Pupil Placement Board. And then I was asked

—22—

by the Pupil Placement Board on the 28th of July to submit

additional information and they asked for it, I think, on

the 4th of August, which had to do with such things as

maps showing the location of pupils and academic records,

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiff's-—Direct

39a

health records and any other pertinent information which

might he helpful in understanding the local situation.

That was just general, what I got.

Q. Now, in that connection, was there a specific request

from Mr. Wingo, on the Pupil Placement. Board, for you

to answer three questions? Bo you recall that? A. I

would say that was not requested on Mr. Wingo as much

as it was that I discussed it with Mr. Wingo, asking what

kind of information would be helpful and he did submit

three questions to which we did guide our discussions with

Pupil Placement Board.

Q. Do you have those questions there? A. Yes, I do.

Q. Would you read them, please. A. Are there Negro

pupils who cannot be excluded from attending white schools

except for race? That is number one. Number two: Would

the Superintendent and School Board so certify to the

Pupil Placement Board. Number three: And in our judg

ment, what would happen in the local communities if some

Negro pupils were assigned to white schools? Those were

the three questions.

The Court: Those are the three questions that Mr.

Wingo asked you; is that right?

—23—

The Witness: Yes, sir.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. When he asked you this, was he asking you to bring

to the Board answers to those questions and did you sub

sequently do that? A. Ask that question again.

Q. Do I understand that Mr. Wingo asked you—told you

he wanted answers to these questions, for you to bring to

the Pupil Placement Board? A. I think it was Mr. Wingo’s

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

40a

suggestion that we might answer these questions when we

went to the Pupil Placement Board. He didn’t ask that I

do it.

Q. Now, did you subsequently have any of your staff em

ployes make any investigations of records and things like

that? A. Yes, sir, we did.

Q. The records of these 39 pupils were examined and

reviewed? A. That is correct.

Q. Who were the People? Would you explain who the

people who did this and what they did? A. Mr. A. B.

Camper—is now deceased—Director of Instruction was

primarily responsible for this assignment. Along with him

was Mrs. Dorothy Gibney. And I am sure they were the

principal ones, together with me.

Q. Now, was this the general type of information that

you gathered? Let’s see if I can state a fair summary of

—24—

what you gathered on these 39 pupils—information like

their name, age, school, grades, school applied for, parents’

name and occupation—those items included? A. Yes.

Q. Names of other children and their families and the

schools they attended? Would you answer each part of it?

A. All right. Go ahead.

Q. Proximity of the schools they sought to attend, the

schools they presently attend, to their home? A. Yes.

Q. Relative percentage of capacity of the schools in

question; that is, in terms of overcrowding? A. Yes, I

think that was part of it.

Q. Whether contemplated school construction would af

fect their assignments in the future—that type of informa

tion? A. Probably so, but I don’t remember exactly in

that way.

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

41a

The Court: Does the Superintendent have a rec

ord of the information that they did get?

Mr. Nabrit: No, sir. Apparently because of Mr.

Camper’s death.

The Court: I will ask him: Do you have a record?

Did you record the information that you gathered

in reference to these applications?

The Witness: Yes, sir, we did.

—25—

The Court: Do you have it?

The Witness: We have portions of it because we

were unable to get all that was gathered because of

the man who was responsible for this died and his

office—I mean his record in it did not show it.

The Court: Would presenting that which you have,

would that be, in your opinion, a fair sample of what

was done in all of these cases?

The Witness: I would say so; yes, sir.

The Court: I will ask you to produce it.

The Witness: Well, may I confer with the person

who would have this information?

Teh Court: I don’t care what the person says. If

you have it, it is part of the school record and I

would like you to produce it.

The Witness: All right.

Mr. Parham: If Your Honor please, on that point,

prior to trial set previously, I had Doctor Bushton’s

office reconstruct this information. Opposing coun

sel has a copy of it. We have no objection to its

getting in.

The Court: If we have it. Apparently, it is going

to save the Court a lot of time. There are a lot of

numbers and names for me to remember. And the

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

42a

school official that died compiled this information,

I am sure I can study it and examine it better than

—26—

what he might say about each individual one. So, for

the purpose of saving* time and in aiding the Court,

if they have a written record and the answers to all

of the questions and information they sought that

they used, let’s put it in the record and then I will

know what they did do.

Mr. Nabrit: Your Honor, I think we have difficulty

here. These information sheets which Counsel fur

nished us were prepared in January, 1961, in con

nection with the ease. Presentation last summer, as

I understand it, was all handwritten notes, and the

presentation that these people made to the—the local

people made to the Pupil Placement Board was oral.

There was no presentation of summary sheets like

these.

In addition, these summary sheets contain—well,

they don’t contain some of the information that was

communicated to the Pupil Placement Board. Spe

cifically, they don’t contain the class medians that

these pupils were measured against. In other words,

they contain these pupils’ test scores, but I was ad

vised, during the depositions—-

The Court: I don’t know what you are talking

about—made in ’61. I asked the Doctor if he had

any official memorandum of information that they

had gathered at the time he was gathering the in

formation for the use and benefit of the Pupil Place

ment Board. He said he had a good part; he didn’t

—2 7 -

have all of it. And I asked him what he had, that

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

43a

is the original, was a fair sample of what they had

done in this ease and he said yes. And, therefore,

I want to see the fair sample, not what he made up

in 1961, if yon have that information.

The Witness: Yes, sir, I have it. It is in raw

form. It is rather voluminous. I will be glad to get

it for you.

The Court: At the noon recess, let’s present it

and, of course, that is the best evidence. I don’t

care whether it is in longhand at the time it was

made.

The Witness: All right, sir, I will be glad to get it

for you.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Now, proceeding on in the sequence of events, Doctor

Rushton— A. Yes, sir.

Q. —isn’t it true that on August 15th you and Mr.

Camper and Mrs. Gfibney went to Richmond and met with

the members of the Pupil Placement Board and Mr. Hilton,

Executive Secretary, and discussed these 39 pupils? A.

We did.

Q. And that at that time you made an oral presentation,

you and your staff made an oral presentation of various

facts about these pupils? A. We discussed with the Pupil

- 2 8 -

Placement Board the 39 applications; yes, sir.

Q. The material that you are going to gather at lunch

time were the notes that you made for this discussion—

the material that you agreed to furnish the Court? A. I

am going to give every bit of the information that I have

with respect to the way we studied these pupils and what

we carried with us, as much as I can.

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

44a

The Court: When you made this report to the

Pupil Placement Board, was that transcribed by

anybody at the time ?

The Witness: No, sir.

The Court: No record was made of what you

people said to each other1?

The Witness: So far as I know there was no rec

ord of that kind.

The Court: All right. There is no record of it.

You may ask what he said, if you are interested in

knowing* what he told the Board.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Well, sir, was it true that during this meeting you

discussed these pupils and placed them in certain cate

gories? A. Wait a minute. I discussed them—assigned

them?

Q. You discussed these 39 pupils in terms of certain

categories, such as one group would be pupils whose intelli-

—29—

gence test or achievement test score or other academic

test score fell below the median score of the pupils in that

grade of the white school they were seeking to enter?

Wasn’t that one group? A. Let me say, as the question

was asked us by the Pupil Placement Board members we

tried to answer their questions, and I am sure each of it

came out along the line that you are talking about. If I

would say that this happened and that, I do not recall;

that those are the specific things that were done. I do re

member discussing it with them and the staff is here that

were there in Richmond and I would be glad to answer

everything I know. But I cannot go down the line—did we

do this, that and the other.

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

45a

Q. Now, do you remember that, at the end of the meet

ing, that same day— A. Yes, sir.

Q. —the Pupil Placement Board made its announcement

of the nine pupils, nine of these Negro Pupils would be

granted transfers? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And that those nine pupils that were granted trans

fers were pupils that you had indicated to the Board could

not be excluded for any reason other than race in terms

used in that question that Mr. Wingo asked? A. That was

my judgment; yes, sir.

Q. Now, is it true that these nine pupils were pupils

who had been very successful in their school work, on the

—3 0 -

intelligence test, on the achievement test; one thing common

to those that were admitted? A. Yes. The record shows

that.

Q. Now, was there discussion of them at this meeting in

terms of how far they were in terms of the relationship of

their scores?

The Court: Mr. Nabrit, what difference does it

make about the nine? They have been transferred.

Their requests were granted. They are in these

schools, are they not? What the Court wants to find

out is why the 30 were not granted transfers, not

why the nine are in. Certainly, you don’t want to

change those transfers. Let’s hear about the ones

that were not in and why they were not admitted.

Mr. Nabrit: Yes, sir.

By Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Now, was it true, Doctor Rushton, that the pupils

who were not admitted, there were several pupils who you

E. W. Rushton—for Plaintiffs—Direct

46a

advised the Board that fell below the median of the class

that they were applying to ? A. Yes.

Q. Is that it? A. Yes; that is correct.

Q. When I say the median of the class they are applying

—31—

to enter, this was the— A. To the class they were going.

Q. The median score obtained by the white pupils in the

grades who would be in the grades they sought to enter

the coming year ? A. Uh-huh.

Q. In the given school involved for each child? A. Yes,

to which they were seeking admission.

Q. So, in other words, to give an example, a Negro child

seeking admission to X school in the sixth grade, his score

was compared to the score of the white pupils who were

going to be in the sixth grade with him who are in the fifth

grade the year before; isn’t that it? A. If a child was

being transferred into a school and that grade, which he

was going into, we take the average of that grade and we

measure whether he would be below the median of that

class.

# * # # *

E. W. RusMon—for Plaintiffs•—Direct

—32—

# # # # *

The Court: I didn’t mean to question it that way.

I mean, on his recommendation. I understood he

testified that the nine of them in his opinion were

eligible for transfer except on the ground of grades

and they didn’t use that ground, so they were trans

ferred. So, I want to know what he told the Pupil

Placement Board, if they are relying on that,

—33—

whether or not he recommended any to be denied

47a

solely on the ground of not coming up to this median

average.

The Witness: Your Honor, as I recall the dis

cussion, there were some who were below the median

of the class to which they were asking for admission.

And that was the main criterion by which we did

not, in our judgment, think they should be con

sidered for that transfer.

By the Court:

Q. Would you say this: And I don’t want you to say

it if it isn’t your considered opinion. If they had been

up to the median average and not below it, would you

have recommended that they were eligible for admission

to the school sought except for that one fact! A. Your

Honor, I am not trying to evade your question either. I

think there are certain other circumstances that might be

taken into consideration other than the fact that they

would be up to the average of the class.

Q. I am not talking about all of the 39. So, therefore,

there isn’t any that was excluded solely on the ground that

they didn’t come up to the median? A. Yes, that is cor

rect. I wouldn’t say that any single criterion would have

been applicable within itself. And I don t remember dis

cussing it in that vein either.

Q. Now, the reason X am asking the question of course,

—34—

this may not be correct. The summary that has been given

to me indicates that 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 of the students

denied transfers were denied on the ground that they were

below the class median—achievement test. And I wanted

to know whether or not those nine—that wras the sole

E. W. Iiushton—for Plaintiffs■—Direct

48a

ground. So, if it is all we have to do is to determine what

the median test was and whether it was a fair and equi

table test—in other words, if you deny a person on the

grounds of residence and on the grounds of this, maybe

the residence alone is sufficient to so we don’t have to

come to the second one, is the point I am getting at. A.

I think that that would be the main criterion. I have the

same list, too, what you have.

—35—

-Y- -Y- -It- -it- -U-•Jp -Sf TF W TP

By the Court:

Q. I am not asking you to without checking to state

that the nine pupils listed under Category C were in fact

denied a transfer on that ground alone. I am merely ask

ing you if you recommended to the Board any student or

students to be denied a transfer solely on the ground of

being below the class median, under the achievement. A.

Well, sir, I did not make any recommendations at all to

the Pupil Placement Board. I did not make any recom

mendations at all. They asked if the School Board made

a recommendation.

Q. Well, the School Board did? A. And there was no

—3 6 -

recommendation, sir.

Q. There was not? A. No, sir.

Q. Then, I am correct that neither the School Board of