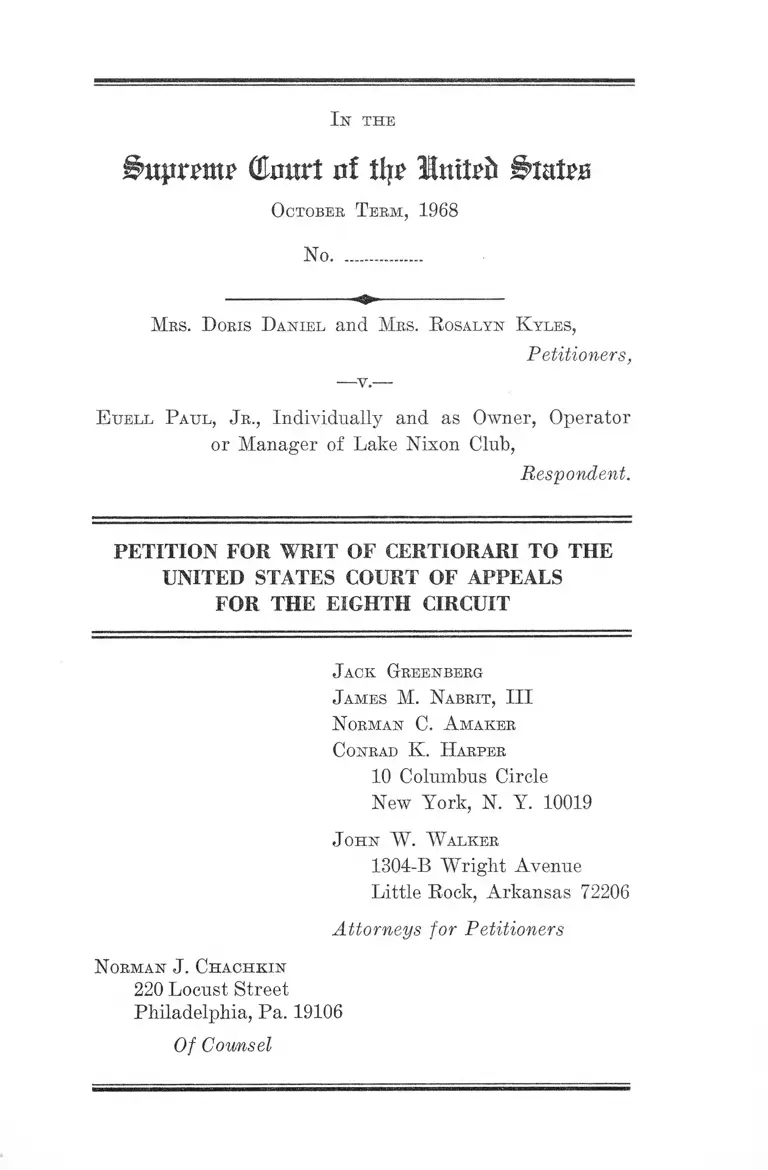

Daniel v. Paul Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Eigth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Daniel v. Paul Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Eigth Circuit, 1968. 9a2df2eb-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a4f9bb1e-faef-4b60-9bd5-e8e16d1b2cda/daniel-v-paul-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-eigth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

(Emtrt nf % Iniftd

October Teem, 1968

No..................

Mrs. D oris Daniel and Mrs. R osalyn K yles,

Petitioners,

--- y .----

E uell P aul, Jr., Individually and as Owner, Operator

or Manager of Lake Nixon Club,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Norman C. A maker

Conrad K. H arper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

J ohn W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

Attorneys for Petitioners

Norman J. Chachkin

220 Locust Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19106

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions B elow ................... 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 2

Questions Presented........................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 3

Statement ....................................................... ...................... 5

Jurisdiction of the District Court ................................... 8

Reasons for Granting the Writ ....................................... 8

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted (a) to Resolve a

Conflict Between the Courts of Appeals for the

Eighth and Fifth Circuits as to Establishments

Covered by §201(b)(4) and (c)(4 ) of the 1964

Civil Rights Act, and (b) to Resolve a Conflict

Between These Same Courts as to the Meaning of

“ Place of Entertainment” in §201(b) (3) and (c) (3)

of the Same Act .......................................................... 8

A. Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act Applies

to the Whole of Lake Nixon Because of Its

Lunch Counter’s Operations................................. 9

B. Lake Nixon Is Place of Entertainment as De

find by Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act .... 13

11

II. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine

Whether the Equal Right to Make and Enforce

Contracts and to Have an Interest in Property,

Guaranteed by 42 U. S. C. §§1981, 1982, Includes

the Right of Negroes to Have Access to a Place

of Public Amusement .................................................. 18

Conclusion ........................... 20

A ppendix :

Memorandum Opinion of the District Court............. la

Decree ............................................................................ 15a

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals .... 16a

Judgment ...................................................................... 41a

Order Denying Rehearing........................................... 42a

A uthorities Cited

Cases:

Bolton v. State, 220 Ga. 632, 140 S. E. 2d 866 (1965) .... 10

Codogan v. Pox, 266 P. Supp. 866 (M. D. Fla. 1967) .... 11

Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U. S. 130 (1967) .... 19

Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., 261 F. Supp. 474 (E. D.

Va. 1966) ................................ 10,13

Fazzio Real Estate Co. v. Adams, 396 F. 2d 146 (5th

Cir. 1968) .......................................................................... 12

Gregory v. Meyer, 376 F. 2d 509 (5th Cir. 1967) ......... 11

Griffin v. Southland Racing Corp., 236 Ark. 872, 370

S. W. 2d 429 (1963)

PAGE

19

H I

Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306 (1964) .... ........... ...10,13

Jones v. Mayer, 36 U. S. L. W. 4661 (U. S. June 17,

1968) ....... 18,19,20

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 394 F. 2d 342

(5th Cir. en banc 1968) ................................ 10,14,15,16,17

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprise, Inc., 256 F. Supp.

941 (D. S. C. 1966), rev’cl on oth. gds., 377 F. 2d 433

(4th Cir. 1967), mod. and aff’d on oth. gds., 19 L. Ed.

1263 (1968) ...................................................... 11

Scott v. Young, 12 Race Rel. L. Rep. 428 (E. D. Va.

1966) .................................................................................. 13

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 36 U. S. L. W. 3481

(U. S. June 17, 1968) ........................................................ 19

Vallee v. Stengel, 176 F. 2d 697 (3rd Cir. 1949) ....... 19

Constitutional Provisions:

United States Constitution

Thirteenth Amendment ..

Fourteenth Amendment

PAGE

2, 3,18

.... 3, 5

Statutes :

28 U. S. C. §1254(1)

28 U. S. C. §1343(3)

28 U. S. C. §1343(4)

42 IT. S. C. §1981.......

42 U. S. C. §1982 .... .

42 U. S. C. §2000a.....

42 U. S. C. §2000a(b)

42 U. S. C. §2000a(c)

2

8

............. 2, 3, 5,18,19

........ ........ 2, 3,18,19

.2, 5,10,13,14,15,16

........ ...... 3,4, 8, 9,12

.........4, 5, 8, 9,16,17

Commerce Clause

Art, 1, §8, cl. 3 ................................................................ 3

Miscellaneous:

Hearings on Miscellaneous Proposals Regarding Civil

Rights Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the House

Committee on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

ser. 4, pt. 2 (1963) .......... ........ ............ .......................... 15

Hearings on H. R. 7152 Before the House Committee

on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. ser. 4, pt. 4

(1963) ......................... 15

Hearings on S. 1732 Before the Senate Committee on

Commerce, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. ser. 26 (1963) ........... 11

H. R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) ........... 13

S. Rep. No. 872 on S. 1732, 88th Cong., 2nd Sess. 3

(1964) ...... 17

109 Cong. Rec. 12276 (1963) ................ .......................... 15,16

110 Cong. Rec. 6557 (1964) ........................................ 17

110 Cong. Rec. 7383 (1964) ........ ...................................... 15

110 Cong. Rec. 7402 (1964) ............................................... 16

110 Cong. Rec. 13915 (1964) ............................................. 17

110 Cong. Rec. 13921 (1964) ............................................... 17

110 Cong. Rec. 13924 (1964) .............................................. 17

iv

PAGE

1st th e

l&uprm? (tart of tijr luit^ States

October Term, 1968

No......... ........

Mrs. D oris Daniel and Mrs. R osalyn K yles,

— v.—

Petitioners,

E uell P aul, Jr., Individually and as Owner, Operator

or Manager of Lake Nixon Club,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit entered in the above-entitled action on

May 3, 1968, rehearing denied June 10, 1968.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit and the dissenting opinion of Judge

Heaney are reported at 395 P. 2d 118, 127. They are set

forth in the appendix, pp. 16a-40a. The opinion of the

LTnited States District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas is reported at 263 F. Supp. 412 and is set forth

in the appendix, pp. la-14a.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit was rendered May 3, 1968. A peti

tion for a rehearing en banc was denied on June 10, 1968.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U. S. C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Lake Nixon Club is a privately owned and operated

recreational area open to the white public in general. Lake

Nixon has facilities for swimming, boating, picnicking,

sunbathing, and miniature golf. On the premises is a snack

bar principally engaged in selling food for consumption on

the premises which offers to serve interstate travelers

and which serves food a substantial portion of which has

moved in commerce.

a) Is the snack bar a covered establishment within the

contemplation of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

and if so, does this bring the entire recreational area within

the coverage of Title II?

b) Is the Lake Nixon Club a place of entertainment

within the scope of Title II?

2. Petitioners are denied admission to Lake Nixon Club

solely because they are Negroes. Have petitioners been

denied the same right to make and enforce contracts and

have an interest in property, as is enjoyed by white citi

zens, in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment and an

Act of Congress, 42 U. S. C. §§1981, 1982?

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This ease involves the Commerce Clause, Art. 1, §8, cl. 3,

and the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the

Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves the following United States

statutes:

42 U. S. C. §1981:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States

shall have the same right in every State and Territory to

make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evi

dence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and

proceedings for the security of piersons and property as

is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like

punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions

of every kind, and to no other.

42 U. S. C. §1982:

All citizens of the United States shall have the same

right, in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white

citizens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and

convey real and personal property.

42 U. S. C. §2000a(b) :

Each of the following establishments which serves the

public is a place of public accommodation within the mean

ing of this subchapter if its operations affect commerce,

or if discrimination or segregation by it is supported by

State action:

4

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch counter,

soda fountain, or other facility principally engaged in sell

ing food for consumption on the premises, including, but

not limited to, any such facility located on the premises

of any retail establishment; or any gasoline station;

(3) any motion picture house, theater, concert hall, sports

arena, stadium or other place of exhibition or entertain

ment; and

(4) any establishment (A) (i) which is physically located

within the premises of any establishment otherwise covered

by this subsection, or (ii) within the premises of which is

physically located any such covered establishment, and

(B) which holds itself out as serving patrons of such

covered establishment.

42 U. S. C. §2000a(c) :

The operations of an establishment affect commerce

within the meaning of this subchapter if . . . (2) in the

case of an establishment described in paragraph (2) of

subsection (b) of this section, it serves or offers to serve

interstate travelers or a substantial portion of the food

which it serves, or gasoline or other products which it

sells, has moved in commerce; (3) in the case of an estab

lishment described in paragraph (3) of subsection (b) of

this section, it customarily presents, films, performances,

athletic teams, exhibitions, or other sources of entertain

ment which move in commerce; and (4) in the case of an

establishment described in paragraph (4) of subsection (b)

of this section, it is physically located within the premises

of, or there is physically located within its premises, an

5

establishment the operations of which affect commerce

within the meaning of this subsection. For purposes of

this section, “ commerce” means travel, trade, traffic, com

merce, transportation, or communication among the sev

eral States, or between the District of Columbia and any

State, or between any foreign country or any territory or

possession and any State or the District of Columbia, or

between points in the same State but through any other

State or the District of Columbia or a foreign country.

Statement

On July 18, 1966, petitioners, Mrs. Doris Daniel and Mrs.

Rosalyn Kyles, Negro citizens of the City of Little Rock,

Pulaski County, Arkansas, instituted a class action in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas against Euell Paul, Jr., individually and as owner

of Lake Nixon Club, Pulaski County, Arkansas (R. 1, 3, 4).1

The petitioners claimed that the Lake Nixon Club was

depriving them, and Negro citizens similarly situated, of

rights, privileges and immunities secured by (a) the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States;

(b) the Commerce Clause of the Constitution; (c) Title II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U. S. C. §2000a), pro

viding for injunctive relief against discrimination in places

of public accommodation; and (d) 42 U. S. C. §1981, pro

viding for the equal rights of citizens and all persons

within the jurisdiction of the United States (R. 3). The

complaint alleged that the Lake Nixon Club pursues a

1 The certified record consists of one volume with district court

proceedings independently paginated from the Eighth Circuit pro

ceedings. All citations in the text are to the district court pro

ceedings.

6

policy of racial discrimination in the operation of its facili

ties, services and accommodations; petitioners prayed for

injunctive relief (R. 3).

On August 3, 1966, Mr. Euell Paul, Jr., answered the

complaint (R. 1). At the trial, Mrs. Paul was made a party

defendant without objection (R. 42; 263 F. Supp. at 414).

After a trial without a jury, the District Court, on Feb

ruary 1, 1967, held that the Lake Nixon Club is not a place

of public accommodation within the contemplation of the

Civil Rights Act and that its operations do not affect com

merce, and dismissed the complaint with prejudice (R. 61,

63; 263 F. Supp. at 420). The petitioners filed notice of

appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit on

March 2, 1967 (R. 63).

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth

affirmed the judgment of the District Court on May 3,

1968, Judge Heaney dissenting, 395 F. 2d 118, 127. On

June 10, 1968, petitioners’ petition for a rehearing was

denied.

Lake Nixon Club is a recreational area comprising 232

acres (R. 43) and located about 12 miles west of Little

Rock, Arkansas (Appellee’s Brief in the Court of Appeals,

1). There is a State highway located 5 miles north of Lake

Nixon and a U. S. highway located 5 miles to the south

(Appellee’s Brief in the Court of Appeals, 2).

During each season, approximately 100,000 people avail

themselves of Lake Nixon’s swimming, picnicking, boating,

sun-bathing, and miniature golf (R. 44, 54; 263 F. Supp.

at 416). The exact number of members is unknown and

the Pauls do not maintain a membership list (R. 56, 263

F. Supp. at 417).

7

At Lake Nixon there is a snack bar which sells ham

burgers, hot dogs, milk and sodas for consumption on the

premises (R. 12, 30, 35; 263 F. Supp. at 416). The snack

bar is operated by Mrs. Paul’s sister under an oral agree

ment whereby the parties share the profits from the snack

bar (R. 32). In 1966 the gross receipts from food sales ac

counted for almost 23% of the total gross receipts ($10,-

468.95 out of a total of $46,326.00) (R. 12, 63).

The equipment of Lake Nixon includes two juke boxes

manufactured out of Arkansas (R. 55; 263 F. Supp. at

417); 15 aluminum paddle boats leased from an Oklahoma

company, and a surfboard or yak purchased from, the same

company (R. 28, 29). The rental cost of the paddle boats

is based on a percentage of the profits realized from their

rental to patrons of Lake Nixon (R. 28).

Lake Nixon Club was advertised in the following media:

(a) once in 1966 in Little Bock Today, a monthly publica

tion distributed free of charge by Little Rock’s leading

hotels, chambers of commerce, motels and restaurants to

their guests, newcomers and tourists; (b) once in 1966 in

the Little Rock Air Force Base publication; (c) and three

days each week from May through September, 1966, over

radio station KALO (R. 11; Petition for Rehearing En

Banc, 5; 263 F. Supp. at 417-418). A typical radio an

nouncement stated:

“Attention all members of Lake Nixon. In answer to

your requests, Mr. Paul is happy to announce the Sat

urday night dances will be continued . . . Lake Nixon

continues their policy of offering you year-round en

tertainment. The Villagers play for the big dance Sat

urday night and, of course, there’s the jam session

Sunday afternoon . . . also swimming, boating, and

8

miniature golf . . . ” 395 F. 2d at 130, n. 10 (dissenting

opinion).

On July 10, 1966, the petitioners sought admission to Lake

Nixon (R. 38, 39). The District Court found that they

were refused admission because they are Negroes (R. 58;

263 F. Supp. at 418). The District Court also found that

Lake Nixon Club is not a private club within the contem

plation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, but is a facility open

to the white public in general (R. 58; 263 F. Supp. at 418).

Jurisdiction of the District Court

Jurisdiction of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Arkansas was based on 28 U. S. C.

§§1343(3) and 1343(4).

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I.

Certiorari Should Be Granted (a) to Resolve a Con

flict Between the Courts of Appeals for the Eighth and

Fifth Circuits as to Establishments Covered by §201 (b)

(4) and (c) (4 ) of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and (b)

to Resolve a Conflict Between These Same Courts as to

the Meaning of “ Place of Entertainment” in §201 (b)

(3 ) and (c) (3 ) of the Same Act.

Lake Nixon Club is a public accommodation within the

coverage of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 on both

of the following grounds:

A) within the premises of Lake Nixon is physically lo

cated a lunch counter jjrincipally engaged in selling food

9

for consumption on the premises which offers to serve in

terstate travelers and which serves food a substantial por

tion of which has moved in commerce, and this lunch counter

serves all patrons of Lake Nixon. 42 U. S. C. §2000a(b)(4)

and (c)(4 ).

B) Lake Nixon is a place of entertainment which custom

arily presents sources of entertainment which move in

commerce. 42 U. S. C. §2000a(b)(3) and (c)(3 ).

A. Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act Applies to the Whole

of Lake Nixon Because of Its Lunch Counter’s Operations

It is not disputed that the lunch counter at Lake Nixon

is principally engaged in selling food for consumption on

the premises. Coverage of the snack bar under Title II

thus depends on whether it offers to serve interstate trav

elers or serves food or other products a substantial portion

of which has moved in commerce.

The Court of Appeals found a total lack of proof of

any offer to serve interstate travelers, 395 F. 2d at 127.

The District Court did not specifically find whether the

Pauls offered to serve interstate travelers. The District

Court found no evidence that Lake Nixon “ ever tried to

attract interstate travelers as such” (R. 57; 263 F. Supp.

at 418) (emphasis added).

Both Courts erred in failing to find that Lake Nixon

offers to serve interstate travelers. The District Court

specifically found that Lake Nixon is open to the white

public in general (R. 58; 263 F. Supp. at 418) and con

cluded that “ it is probably true that some out-of-state peo

ple” have used the facilities of Lake Nixon (R. 57; 263

F. Supp. at 418). An offer to serve the general public,

under circumstances which make it reasonable to assume

10

that some interstate travelers will accept the offer, is an

offer to serve interstate travelers, where there is no in

quiry made as to the customers’ origin. Hamm v. Rock

Hill, 379 U. S. 306 (1964); Miller v. Amusement Enter

prises, Inc., 394 F. 2d 342 (5th Cir. en banc, 1968); Evans

v. Laurel Links, Inc., 261 F. Supp. 474 (E. D. Va. 1966);

Bolton v. State, 220 Ga. 632, 140 S. E. 2d 866 (1965).

Circumstances which make it reasonable to assume that

some interstate travelers will accept the offer to serve the

general public are present in this case. The Pauls placed

advertisements in magazines distributed to tourists and

servicemen. Although radio announcements were addressed

to “members” of Lake Nixon, 100,000 “members” use Lake

Nixon’s facilities each year and “ members” bring guests.

A reasonable conclusion is that a significant number of

people know that Lake Nixon is in fact open to the white

public in general and that a nominal membership fee of

25 ̂ is charged simply to exclude undesirables including

Negroes (see dissenting opinion of Judge Heaney, 395

F. 2d at 130). The radio announcements suggest no geo

graphical or other limitation on membership, 395 F. 2d at

130, n. 10 (dissenting opinion). That advertising is not

geographically restricted is an important factor in finding

an offer to serve interstate travelers. Miller v. Amusement

Enterprises, Inc., supra.

Lake Nixon is only 5 miles from a U. S. highway and

5 miles from the nearest State highway. For the courts

below this was too remote to affect commerce (395 F. 2d

at 123,125; R. 57; 263 F. Supp. at 418). In Evans v. Laurel

Links, Inc., supra, however, the location of a golf course

4 blocks from a State highway and 5 miles from the nearest

federal highway was deemed material to coverage under

Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

11

There is no evidence that any inquiry is made as to the

origin of “ members” or their guests. No address is re

quired on the membership cards, 395 F. 2d at 130, n. 9 (dis

senting opinion). There is no list of members (R. 56; 26o

F, Supp. at 417). No signs are posted excluding interstate

travelers, 395 F. 2d at 130, n. 9 (dissenting opinion).

Not only does Lake Nixon offer to serve interstate trav

elers, but in addition a substantial portion of the food

served and other products sold at the snack bar have moved

in commerce, It is settled that substantial means “more

than minimal” . Gregory v. Meyer, 376 F. 2d 509, 511 n. 1

(5th Cir. 1967); Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprise, Inc.,

256 F. Supp. 941 (D. S. C. 1966), rev’d on other grounds,

377 F. 2d 433 (4th Cir. 1967), modified and a fif'd on other

grounds, 19 L. Ed. 1263 (1968) (18% is substantial); Codo-

gan v. Fox, 266 F. Supp. 866 (M. D. Fla. 1967) (23-30% is

substantial); Hearings on 8. 1732 Before the Senate Com

mittee on Commerce, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., ser. 26 at 24

(1963) (testimony of Attorney General Kennedy).

The only food served at the snack bar is hamburgers, hot

dogs, sodas and milk (R. 12, 30, 35; 263 F. Supp. at 416);

many soft drinks and hamburgers are sold (R. 32, 35). The

District Court took judicial notice that the principal ingre

dients of bread are produced in states other than Arkansas,

and that some of the ingredients of the soft drinks prob

ably originated outside Arkansas (R. 58; 263 F. Supp. at

418). In addition, the snack bar contains a juke box manu

factured outside of Arkansas; many of the records played

on the juke box are also manufactured out of state (R. 55;

263 F. Supp. at 417). Therefore, the District Court and the

Court of Appeals erred in failing to find that more than a

minimal amount of the food served and the music played in

the snack bar have moved in interstate commerce.

12

Because the snack bar is physically located within the

premises of Lake Nixon and holds itself out as serving

patrons of Lake Nixon, all of the facilities and privileges

of Lake Nixon comprise a place of public accommodation

within the contemplation of Title II.

Both the District Court and the Court of Appeals held

that, because the gross income from food sales constitutes

a relatively small percentage of the total gross income

(23%) and the sale of food is merely an adjunct to the

Pauls’ principal purpose of providing recreational facili

ties, Lake Nixon is a single unit operation and thus not cov

ered by 42 U. S. C. §2000a(b) (4). For the Eighth Circuit,

coverage under Title II requires at least two establishments

under separate ownership. See 395 F. 2d at 123. This

holding is in conflict with the decision of every other court

which has considered this subsection.

In Fazsio Real Estate Co. v. Adams, 396 F. 2d 146 (5th

Cir. 1968), the Court held that where the operators of a

bowling alley also operated a snack bar for the patrons of

the bowling alley, the entire establishment was covered by

this subsection. In Fazsio, income from the sale of food

and beer represented 23% of the total gross income; in

come from the sale of food alone represented 8 to 11% of

the total gross income. The Court held that even 8 to 11%

could not be considered an insignificant adjunct and explic

itly rejected the substantial business purpose test applied

by the Eighth Circuit, compare 396 F. 2d at 150 with 395

F. 2d at 123. The Fifth Circuit stated, 396 F. 2d at 149 :

The Act contemplates that the term “ establishment”

refers to any separately identifiable business operation

without regard to whether that operation is carried on

in conjunction with other service or retail sales oper

13

ations and without regard to questions concerning

ownership, management or control of such operations.

In Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., supra, the Court held an

entire golf course within the coverage of Title II, because

the operators of the golf course maintained a lunch counter

for the patrons of the course. Income from food sales con

stituted 15% of the total gross income of the golf course.

See also Hamm v. Rock Hill, supra,- Scott v. Young, 12

Bace Eel. L. Eep. 428 (E. D. Va. 1966) (recreational area

with snack bar). The legislative history supports the ma

jority rule. The Eeport of the House Judiciary Committee

states that subsection (b) (4) “ would include, for example,

retail stores which contain public lunch counters otherwise

covered by Title II” . H. E, Eep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. 20 (1963).

Even under its own rule that Title II covers only sepa

rately managed but physically connected establishments,

the Eighth Circuit erred in failing to find the snack bar’s

operations made Lake Nixon a public accommodation within

the coverage of Title II. The evidence is that the snack

bar is a separate enterprise managed by Mrs. Paul’s sister

pursuant to an oral contract whereby the Pauls and Mrs.

Paul’s sister share the profits from food sales (B. 32).

B. Lake Nixon Is Place of Entertainment as Defined by

Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

Even if Lake Nixon is found to be within the scope of

subsection (b)(4) because of the presence of a snack bar

within its premises, this Court should also determine

whether Lake Nixon is a place of entertainment within

the contemplation of the Civil Eights Act of 1964. The

snack bar could be eliminated for the purpose of removing

.14

Lake Nixon from Title II coverage; further litigation

would then be necessary to determine whether Lake Nixon

is a place of entertainment. This possibility is not fanciful

for in a companion case involving a similar recreational

area, all sales of food were discontinued after the peti

tioners instituted an action under Title II (R. 54; 263 F.

Supp. at 417). In addition, the conflict between the Eighth

Circuit’s construction of “ place of entertainment” and that

of the Fifth Circuit in Miller v. Amusement Enterprises,

Inc., supra, should be resolved.

The Eighth Circuit also held Lake Nixon was not a

“ place of entertainment” , because the Court found a total

lack of evidence that Lake Nixon’s activities or entertain

ment moved in commerce, 395 F. 2d at 125. The District

Court defined “ other place of entertainment” to mean an

establishment where the patrons are spectators or listeners

and their physical participation is non-existent or minimal,

and held that Lake Nixon is not within this definition

(R. 60; 263 F. Supp. at 419).

In Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., supra, the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, sitting en banc,

reversed the prior decision of a three-judge panel (re

ported at 391 F. 2d 86), and held that the Fun Fair amuse

ment park is a place of entertainment within the coverage

of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Noting that

it was not necessary to its decision, the Court held that

even under a narrow construction of “ place of entertain

ment” to include only places which present exhibitions for

spectators, Fun Fair is a covered establishment, because

“many of the people who assemble at the park come there

to be entertained by watching others, particularly their

own children, participate in the activities available” , 394

F. 2d at 348. Swimming, boating, picnicking, sun-bathing

15

and dancing at Lake Nixon are certainly as much, if not

more, spectator activities as ice-skating and “ kiddie rides” ,

see 394 F. 2d at 348.

In Miller, the Fifth Circuit rejected a narrow construc

tion of “place of entertainment” and held that, in view of

the inconclusive nature of the relevant legislative history

and of the overriding purpose of the Civil Eights Act,

“place of entertainment” should be construed liberally to

mean “ a place of enjoyment, fun and recreation” , 394 F. 2d

at 349.

The overriding purpose of Title II of the Civil Eights

Act was to eliminate discrimination in those facilities which

were the focal point of civil rights demonstrations. Hear

ings on H. R. 7152 Before the House Comm, on the Judi

ciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., ser. 4, pt. 4, at 2655 (1963)

(Testimony of Attorney Gen’l Kennedy). President Ken

nedy clearly intended that recreational areas and other

places of amusement be covered. Hearings on Miscellane

ous Proposals Regarding Civil Rights Before Subcomm.

No. 5 of the House Comm, on the Judiciary, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess., ser. 4, pt. 2, at 1448-1449 (1963). Facilities which

were the focal point of demonstrations were consistently

identified in both the Senate and House hearings as lodg

ing houses, eating places, and places of amusement or rec

reation. 110 Cong. Eec. 7383 (1964) (Eemarks of Sen.

Young). While the Senate was debating the Act, there

were demonstrations at the Gwynn Oak Amusement Park

in Maryland; Senator Humphrey stated that this was proof

of the need for this Act. 109 Cong. Eec. 12276 (1963).

Under either a narrow or a liberal construction of “ place

of entertainment” , coverage depends on whether Lake

Nixon customarily presents sources of entertainment which

move in commerce. The Eighth Circuit could not discern

16

any evidence that any source of entertainment customarily

presented by Lake Nison moved in interstate commerce,

395 F. 2d at 125.

In fact, “ sources of entertainment” were intended to in

clude equipment. In a discussion of subsection (c)(3 ),

Senator Magnuson, floor manager of Title II, pointed out

that if “ establishments which receive supplies, equipment

or goods through the channels of interstate commerce . . .

narrow their potential markets by artificially restricting

their patrons to non-Negroes, the volume of sales and

therefore, the volume of interstate purchases will be less,”

110 Cong. Eec. 7402 (1964) (emphasis added). In the

discussion of the demonstration at the Gwynn Oak Amuse

ment Park, Senator Humphrey believed that the park

would be covered by the Act in part because he was “ con

fident that merchandise and facilities used in the park

were transported across State lines,” 109 Cong. Rec. 12276

(1963).

Lake Nixon purchases and leases its boats from an Okla

homa company. The Pauls rent two juke boxes which

were manufactured outside Arkansas and which play rec

ords manufactured outside Arkansas. In view of these

facts the Eighth Circuit is in direct conflict with Fifth

Circuit’s decision in Miller. The Miller Court relied in part

on the fact that 10 of the 11 “kiddie rides” at the park

were purchased from out of state, 394 F. 2d at 351, to

find an effect on commerce. But the Court also concluded

that even under a narrow construction of the Act, since

Fun Fair is located on a major highway and does not

geographically restrict its advertising, the logical conclu

sion is that a number of the patron-performers move in

commerce, 394 F. 2d at 349. The same circumstances which

make it reasonable to assume that some interstate travelers

17

will accept Lake Nixon’s offer to serve the general public

make it reasonable to assume that some of Lake Nixon’s

patron-performers move in commerce.

The Eighth and Fifth Circuits are also in conflict as to

the meaning of “move in commerce” . The District Court

found that Lake Nixon’s operations do not affect commerce

on the ground that, although the boats, juke boxes and

records have moved in commerce, they do not now move

(R. 62; 263 F. Supp. at 420). The Court concluded that

because the phrase, “has moved” , appears in the section

concerning eating facilities, Congress must have intended

to limit the section concerning places of entertainment to

sources which “move” , and therefore sources of entertain

ment which have, but no longer move, are not covered (R.

61-62; 263 F. Supp. at 420). The Fifth Circuit, on the

other hand, expressly concluded in Miller that Congres

sional use of the present tense of “move” was not intended

to exclude other tenses, 394 F. 2d at 351-52.

The legislative history supports the conclusion of the

Fifth Circuit. The Report of the Senate Committee on

Commerce refers within a single paragraph to “ sources

of entertainment which move in interstate commerce” and

“ entertainment that has moved in interstate commerce” ,

as within the contemplation of subsection (c)(3 ). S. Rep.

No. 872 on S. 1732, 88th Cong., 2nd Sess. 3 (1964). See

also 110 Cong. Rec. 6557 (1964) (remarks of Sen. Kuchel).

In addition, a proposal to amend section 2000a(c) (3) to read

“ sources of entertainment which move in commerce and

have not come to rest within a state” was rejected. 110

Cong. Rec. 13915, 13921 (1964). The subsequent debate

indicates that Congress intended the bill to reach busi

nesses which had a minimal or insignificant impact on

interstate commerce. 110 Cong. Rec. 13924 (1964).

18

II.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine Whether

the Equal Right to Make and Enforce Contracts and to

Have an Interest in Property, Guaranteed by 42 U. S. C.

§§1981, 1982, Includes the Right of Negroes to Have

Access to a Place of Public Amusement.

In the Civil Rights Act of 1866, enacted pursuant to

the Thirteenth Amendment, Congress provided, inter alia,

for citizens to have the same right to make and enforce

contracts and have an interest in property as is enjoyed

by white citizens. These provisions are now embodied in

42 U. S. C. §§1981, 1982. Petitioners have been denied

this right because the Pauls refused them the right to

acquire for 25 ,̂ a so-called “membership” in Lake Nixon

Club solely on racial grounds. The district court found

that “white applicants for membership are admitted as a

matter of routine” (R. 56; 263 F. Supp. at 417).

In Jones v. Mayer, 36 U. S. L. W. 4661 (U. S. June 17,

1968), this Court held that §1982 forbade privately in

flicted racial discrimination with respect to the acquisition

and use of real property. This cause presents the impor

tant question whether the Jones principle applies, either

directly or by necessary implication, to a place of public

amusement. Neither of the lower courts ruled on this

issue since Jones was decided subsequent to the Eighth

Circuit’s denial of rehearing.

In Jones this Court found §1982 justified as a legitimate

exercise of Congressional power under the Thirteenth

Amendment outlawing badges and incidents of slavery.

This approval of the equal property rights guarantee of §1982

19

is directly applicable here because admission to Lake Nixon

is in the nature of a right to use, for a time, the real and

personal property of which the area consists. The fact that

§19S2 was not pleaded below does not bar petitioners from

relying on it here because this Court has made clear that

the “ mere failure” to raise a constitutional question “ prior

to the announcement of a decision which might support it

cannot prevent a litigant from later invoking such a

ground” Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U. S. 130, 142-

143 (1967), and cases cited. Furthermore, this precise is

sue was before this Court just last term in Sullivan v.

Little Hunting Park, 36 U. S. L. W. 3481 (U. S. June 17,

1968) where this Court vacated the judgment of the Vir

ginia Court of Appeals and remanded the case for further

consideration in light of Jones even though the Sullivan

petitioners did not rely on §1982 in the Virginia courts.

In any case, 42 U. S. C. §1981, which was specifically

pleaded in the complaint herein, outlaws racial discrimina

tion in contractual arrangements and, therefore, applies

here because petitioners’ race was the sole reason they

were not permitted to purchase “ membership” privileges

at Lake Nixon.2 It follows that the Jones holding that the

1866 Civil Eights Act, of which §1981 was an integral part,

bars private racial discrimination is at least as applicable

to Lake Nixon’s “memberships” as it was to the corporate

shares in Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, supra.

2 There is little doubt that purchase of “membership” privileges,

like the purchase of a ticket, to a place of public amusement in

cludes judicially enforceable contractual rights, see Griffin v. South

land Racing Corp., 236 Ark. 872, 370 S. W. 2d 429 (1963) ; Vallee

v. Stengel, 176 F. 2d 697 (3rd Cir. 1949).

20

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the writ of certiorari should

issue as prayed and the judgment of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit should be re

versed or, in the alternative, vacated and remanded for

further consideration in light of Jones v. Mayer, 36

U. S. L. W. 4661 (U. S. June 17, 1968).

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Norman C. A maker

Conrad K. H arper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

J ohn W. W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

Attorneys for Petitioners

Norman J. Chachkin

220 Locust Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19106

Of Corns el

A P P E N D I X

la

In the United States District Court Eastern District

of Arkansas Western Division

Rosalyn Kyles and Doris Daniel, )

Plaintiffs, )

v. ) LR-66-0-149

Euell Paul, Jr., Individually and as Owner )

Manager or Operator of the Lake )

Nixon Club, )

Defendant. )

Rosalyn Kyles and Doris Daniel, )

Plaintiffs, )

v. ) LR-66-C-150

J. A. Culberson, Individually and as '

Owner, Manager or Operator of Spring )

Lake, Inc. )

Defendant. )

Memorandum Opinion of the District Court

These two suits in equity, brought under the pro

visions of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, P.L.

88-352, §§201 et seq., 78 Slat. 243 et seq., 42 U.S.C.A..,

§§2000a and 2000a-l through 2000a-6, have been consoli

dated for trial and have been tried to the Court without a

jury. Federal jurisdiction is not questioned and is es

tablished adequately by reference to section 207 of the

Act, 42 U.S.C.A., §2000a-6.

Plaintiffs are Negro citizens of Little Rock, Pulaski

County, Arkansas. The defendants in No. 149, Mr. and

Mrs. Euell Paul, Jr., own and operate a recreational

facility known as Lake Nixon. The corporate defendant

in No. 150, Spring Lake Club, Inc., own and operate a

similar facility known as Spring Lake. All of the stock

2a

in Spring Lake Club, Inc., except one qualifying share,

is owned by the defendant, J. A. Culberson, and his wife.

The two establishments are not far from each other.

Both are located in Pulaski County some miles west of

the City of Little Rock. In July 1966 the two plaintiffs

presented themselves at both establishments and sought

admission thereto. They were turned away in both in

stances on the representation that the establishments were

“ private clubs.”

On July 19 plaintiffs commenced these actions on

behalf of themselves and others similarly situated. The

complaints allege in substance that both Lake Nixon and

Spring Lake are “ Public Accommodations” within the

meaning of Title II of the Act, and that under the pro

visions of section 201(a) they, and others similarly sit

uated, are “ entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the

goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, and ac

commodations (of the facilities) without discrimination or

segregation on the ground of race, color, religion, or

national origin.” They pray for appropriate injunctive

relief as provided by section 201 of the Act.

In their answers the defendants1 deny that Lake

Nixon and Spring Lake are public accommodations within

the meaning of the Act; affirmatively, they plead that the

two facilities are “ private clubs” and are exempt from

the Act by virtue of section 201(a), even if initial coverage

exists.

Sections 201(a) and 201(b) of the Act prohibit racial

discrimination in certain types of public accommodations

if their operations “ affect” interstate commerce, or if

racial discrimination or segregation in their operation is

“ supported by State action.”

'Originally, the suits were brought against Mr. Paul and Mr.

Culberson only. At the commencement of the trial Mrs. Paul and

Springs Lake Club, Inc., were made parties defendant without ob

jection, and they have adopted, respectively, the answers of Mr.

Paul, and Mr. Culberson.

3a

Section 201(b) makes tlie prohibition applicable to

four categories of business establishments, namely:

“ (1) any inn, hotel, motel, or other establishment

which provides lodging to transient guests, other than an

establishment located within a building which contains not

more than five rooms for rent or hire and which is actually

occupied by the proprietor of such establishment as his

residence;

“ (2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch

counter soda fountain, or other facility principally en

gaged in selling food for consumption on the premises, in

cluding, but not limited to, any such facility located on the

premises of any retail establishment; or any gasoline

station;

“ (3) any motion picture house, theater, concert hall,

sports arena, stadium or other place of exhibition or en

tertainment; and

“ (4) any establishment (A) (i) which is physically

located with in the premises of any establishment other

wise covered by this subsection, or (ii) within the premises

of which is physically located any such covered establish

ment, and (B) which holds itself out as serving patrons of

such covered establishment.”

Section 201(c) sets forth criteria whereby it may be

determined whether an establishment affects interstate

commerce. That section is as follows:

“The operations of an establishment affect commerce

within the meaning of this subchapter if (1) it is one of

the establishments described in paragraph (1) of subsec

tion (b) of this section; (2) in the case of an establish

ment described in paragraph (1) of subsection (b) of this

section, it serves or offers to serve interstate travelers or

a substantial portion of the food which it serves, or gaso

line or other products which it sells, has moved in com

merce; (3) in the case of an establishment described in

paragarph (3) of subsection (b) of this section, it custom

arily presents films, performances, athletic teams, ex

4a

hibitions, or other sources of entertainment which move in

commerce; and (4) in the case of an establishment de

scribed in paragraph (4) of subsection (b) of this section,

it is physically located within the premises of, or there is

physically located within its premises, an establishment

the operations of which affect commerce within the mean

ing of this subsection. For purposes of this section, “ com

merce” means travel, trade, traffic, commerce, transpor

tation, or communication among the several states, or be

tween the District of Columbia and any State, or between

any foreign country or any territory or possession and any

State or the District of Columbia, or between points in the

same State but through any other State or the District

of Columbia or a foreign country.”

Section 101(d) is as follows:

“ Discrimination or segregation by an establishment is

supported by State action within the meaning of this sub

chapter if such discrimination or segregation (1) is car

ried on under color of any law, statute, ordinance, or regu

lation; or (2) is carried on under color of any custom or

usage required or enforced by officials of the State or

political subdivision thereof; or (3) is required by action

of the State or political subdicision thereof.”

The exemption invoked by defendants appears in sec

tion 201(e) which provides that the provisions of Title II

of the Act do not apply to “a private club or other estab

lishment not in fact open to the public, except to the ex

tent that the facilities of such establishment are made

available to the customers or patrons of an establishment

within the scope of subsection (b) of this section.”

Federal prohibitions of racial, ethnic or religious dis

crimination or segregation in State and municipal facili

ties are based ultimately on the 14th Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. Title II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 finds its constitutional sanction in the

commerce clause of the Constitution itself. Constitution,

Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3. That Title II, as written,

is constitutional is now settled beyond question, at least

5a

as far as this Court is concerned at this time. Heart of

Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U.S. 241; Katzenbach

v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294; Willis v. The Pickrick Restau

rant, E.D. Ga., 231 F.Supp. 396, appeal dismissed; Maddox

v. Willis, 382 U.S. 18, rehearing denied, 382 U.S. 922.

The rationale of those holdings is that Congress per

missibly found that racial discrimination, including racial

segregation, in certain types of business establishments

adversely affects interstate commerce, and acted constitu

tionally to prohibit such discrimination. These eases

also establish that, even though practices on the part of

an individual enterprise have no significant or even meas

urable impact on commerce, such practices by such enter

prise are prohibited where they are of a type which Con

gress has found affects commerce adversely.

In coming to the latter conclusion the Court in Mc

Clung drew an analogy between an individual business

man who practices racial discrimination and an individual

farmer who violates a provision of the Government farm

program. It was said (pp. 300-301 of 379 U.S.):

“ It goes without saying that, viewed in isolation, the

values of food purchased by Ollie’s Barbecue from sources

supplied from out of state was insignificant when com

pared with the total foodstuffs moving in commerce. But,

as our late Brother Jackson said for the Court in Wickard

v. Filburn, 317 U.S. I l l (1942):

“ ‘That appellee’s own contribution to the demand for

wheat may be trivial by itself is not enough to remove him

from the scope of federal regulation where, as here, his

contribution taken together with that of many others simi

larly situated, is far from trivial . . .

The burden in these cases is upon the plaintiffs to

establish, first, that the facilities in question are estab

lishments covered by the Act and, second, that plaintiffs

have been subjected to racial discrimination prohibited by

the Act. On the other hand, the burden is upon the re

spective defendants to show that they are entitled to the

private club exemption which they invoke.

6a

There is no serious dispute as to the facts in either

case.

Lake Nixon has been a place of amusement in Pulaski

County for many years. Several years ago the proper

ties were acquired and improved by Mr. and Mrs. Paul,

the present owners and operators. The Spring Lake

property was acquired by Mr. Culberson in the spring of

1965 and the Spring Lake Club. Inc., was organized as an

ordinary business and corporation under the general cor

poration laws of Arkansas on April 12 of that year.2 Both

establishments are operated for the financial profit of the

owners or owner. During 1963 and 1966 Lake Nixon

earned substantial profits; Mr. Culberson is not sure

whether Spring Lake has earned profits; no dividends

have been paid by the corporation, and Mr. Culberson has

drawn no salary. He is engaged in a number of business

enterprises, and Spring Lake is actually operated by hired

employees of the corporation.

The facilities available at both establishments are es

sentially the same although those at Lake Nixon are con

siderably more extensive than those available at Spring

Lake. Primarily, the recreation offered is of the out

door type, such as swimming, boating, picnicing, and sun

bathing. Lake Nixon also has a miniature golf course.

There is a snack bar at each establishment at which

hamburgers, hot dogs, some sandwiches, soft drinks, and

milk are sold to patrons during 1965 and 1966. However,

the snack bar operations were purely incidental to the

recreational facilities, and the income derived from the

sales of food and drinks was small in comparison to the

income derived from fees for the use of the recreational

facilities. About the middle of August 1966 and after

this suit was filed, the sale of food items at Spring Lake

was discontinued entirely.

2Mr. Culberson did no' recall definitely whether title to the

property was taken originally in his name and then transferred to

the corporation or whether the former owner conveyed directly to

the corporation. The matter is not material. Mr. Culberson’s pri

mary purpose in incorporating his operation was to avoid personal

tort liability in case of accidental injury to a patron.

7a

In each of the snack bars there is located a mechani

cal record player, commonly called a “ Juke Box,” which

patrons operate by the insertion of coins. Patrons may

dance to the juke box music or may simply sit and listen

to it. There is no dispute that the juke boxes were man

ufactured outside of Arkansas, and the same thing may

be said about at least many of the records played on the

machines. The machines are rented from their local

owner or owners by both of the establishments here in

volved.

During the months in which Lake Nixon is open, a

dance is held once a week on Friday or Saturday night.

An attendance charge is made with respect to these dances,

and there is “ live music” supplied by local bands made

up of young people who call themselves by such names as

“ The Romans,” “ The Pacers,” or “ The Gents.” Al

though the bands are compensated for their playing,

actually the musicians are little more than amateurs, and

their operations do not in general extend beyond the Little

Rock-North Little Rock areas; certainly, there is nothing

to indicate that these young musicians move in interstate

commerce.

On occasions similar dances are held at Spring Lake,

but they are sporadic and care is taken not to schedule a

dance at Spring Lake for the same night on which a dance

is to be held at Lake Nixon.

The operators of both facilities have stated candidly

that they do not want to serve Negro patrons for fear

of loss of business, and they do not desire to be covered

by the Act. In this connection it appears that Mr. Cul

berson is willing to do just about anything in the future to

avoid coverage if Spring Lake is in fact covered and non

exempt at this time.

Following the passage of the Act, Mr. and Mrs.

Paul began to refer to their operation as a private

club, and patrons have been required, at least during 1965

and 1966, to purchase “ memberships” for the nominal

fee of twenty-five cents a year or per season. These

8a

fees are in addition to regular admission charges. A

similar procedure has been following at Spring Lake

which was not organized until after the passage of the

Act. At Lake Nixon “ memberships” to the “ club” are

sold by either Mr. or Mrs. Paul; at Spring Lake “ mem

berships” are sold by whatever employee or employees

happen to be in charge of the operation at the time.

The Court finds that neither facility has any mem

bership committee; there is no limit on the number of

members of either “ club,” 3 no real selectivity is practiced

in the selection of members, although at each establish

ment the management reserves the right to refuse to

adult undesirables; there are no membership lists. The

Pauls do not know how many people are “members” of

the Lake Nixon Club; Mr. Culberson estimates that Spring

Lake, the smaller of the operations, has about 4,000 “ mem

bers.” Subject to a few more or less accidental excep

tions at Spring Lake, Negroes are not admitted to “ mem

bership” in either “ club.” White applicants for mem

bership are admitted as a matter of routine unless there

is a personal objection to an individual white person

making use of the facilities.

The record reflects that during 1965 and 1966 Lake

Nixon has used the facilities of Radio Station KALO to

advertise its weekly dances; the announcements were

made on Wednesday, Thursdays, and Fridays of each

week from the last of May through September 7. Dur

ing the same period Lake Nixon inserted one advertise

ment in “ Little Rock Today,” a monthly magazine indi

cating available attractions in the Little Rock area, and

inserted one advertisement in the “ Little Rock Air Force

Base,” a monthly newspaper published at the Little Rock

Air Force Base at Jacksonville, Arkansas.

3When plaintiffs applied for admission to Lake Nixon and asked

about joining the “club,” they were told that the membership was

full; the Pauls now admit that such statement was false in thay there

has nev°r been and is not now any limit to t he “membership” of

the “club” .

9a

On June 4, and June 30, 1966, Spring Lake advertised

Saturday niglit dances over Radio Station KALO; on

May 26, 27, and 28 a dance was advertised over Station

KAAY. Station KALO apparently leased the premises

for a picnic held in July and advertised that picnic from

June 6 through July 16.

In 1965 Spring Lake advertised certain dances by

means of announcements over Station KALO. Two of

these announcements indicated that there would be diving

exhibitions during the intermissions, and one of the an

nouncements was to the effect that in addition to the div

ing exhibition there would be a display of fireworks.

The record contains a sample of a brochure put out by

Spring Lake; that brochure shows pictures of the facilities,

describes them in some detail, refers without emphasis

to “ guest fees” in addition to the regular admission

charge and points out that the fee of twenty-five cents

is to be paid only once. Readers of the brochure are

advised that the facilities may be reserved for private

parties by telephoning “ well in advance.” The brochure

also contains a map showing one how to reach Spring

Lake, and the “ membership cards” of Spring Lake depict

a similar map.

As stated, both establishments are located some miles

west of Little Rock. Both are accessible by country

roads; neither is located on or near a State or federal

highway. There is no evidence that either facility has

ever tried to attract interstate travelers as such, and the

location of the facilities is such that it would be in the

highest degree unlikely that an interstate traveler would

break his trip for the purpose of utilizing either estab

lishment. Of course, it is probably true that some out-

of-state people spending time in or around Little Rock

have utilized one or both facilities.

Food and soft drinks are purchased locally by both

establishments. The record before the Court does not

disclose where or how the local suppliers obtained the

products which they sold to the establishments. The

10a

meat products sold by defendants may or may not have

come from animals raised, slaughtered, and processed in

Arkansas. The bread used by defendants was baked and

packaged locally, but judicial notice may be taken of the

fact that the principal ingredients going into the bread

were produced and processed in other States. The soft

drinks were bottled locally, but certain ingredients were

probably obtained by the bottlers from out-of-State

sources.

Turning now to the law, the Court will take up the

issues in what appears to it to be a convenient, if perhaps

not a strictly logical, order.

Defendants’ claims of exemption as private clubs will

be rejected out of hand. The Court finds it unnecessary

to attempt to define the term “ private club,” as that term

is used in section 201(a) because the Court is convinced

that neither Lake Nixon nor Spring Lake would come

within the terms of any rational definition of a private

club which might be formulated in the context of an ex

ception from the coverage of the Act. Both of these

establishments are simnly nrivately owned accommoda

tions operated for profit and open in general to all of

the public who are members of the white race. Cf. United

States v. Northwest Louisiana Restaurant Club, W.D. La.,

256 F. Supp. 151.

The Court finds without difficulty that plaintiffs were

excluded from both facilities because they are Negroes.

That fact was expressly admitted by Mr. Paul speaking

for Lake Nixon and is inferable if not substantially^ ad

mitted with respect to Spring Lake. The Court finds

also that any other individual Negroes who might have

applied for admission to the facilities during 1966 would

have been excluded on account of their race, and that

defendants will continue to exclude Negroes unless the

Court determines that the facilities are covered by the

Act.

This brings the Court to a consideration of the basic

issue of coverage. The question is not whether Lake

11a

Nixon and Spring Lake are “ public accommodations,”

but whether they are public accommodations falling within

one or more of the four categories of establishments cov

ered by the Act.

It is not suggested that either establishment falls

within the first statutory category, and the Court is per

suaded that neither falls within the fourth. In that con

nection the Court finds that both Lake Nixon and Spring

Lake are single unit operations with the sales of food

and drink being merely adjuncts to the principal business

of making recreational facilities available to the public.

Section 201(b)(4) plainly contemplates at least two es

tablishments, one of them covered by the Act, operating

from the same general premises. See e.g. Pinkney v.

Meloy, M.D. Fla., 241 F. Snpp. 943. That situation does

not exist here.

The second category set out in section 201(b)(2) con

sists of establishments “ principally engaged” in the sale

of food for consumption on the premises. Food sales

are not the principal business of the establishments here

involved, and the second category does not cover them.

Cf. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., D.C., S.C.,

256 F. Supp 941.4

The third category, section 201(b)(3), includes cer

tain specifically described places of exhibition or enter

tainment and also “ any other place of exhibition or enter

tainment.” It is clear that neither Lake Nixon nor Spring

Lake is a motion picture house, concert hall, theatre, sports

arena, or stadium. Hence, if either establishment is

covered by the third category it must be on the theory

that it falls within the catch-all phrase above quoted.

Determination of the scope of the catch-all phrase

calls for an application of the Rule of ejusdem generis

4In using the term “food sales” the Court includes sales of both

food and soft drinks. That sales of drinks would not be considered

as sales of “food” is indicated by Chava v. Sdrales, 10 Cir., 344 F.

2d 1019; Robertson v. Johnston, E.D. La., 249 F. Supp. 615; Tyson v.

Cazes, E.D. La., 238 F. Supp. 937, rev’d on other grounds, 3 Cir. 363

F. 2d 742.

12a

Robertson v. Johnston, E.D. La., 248 F.Supp. 618, 622.

In that case it was pointed out that “place of entertain

ment” is not synonymous with “place of enjoyment.” And

in addition this Court will point out that “ entertainment”

and “recreation” are not synonymous or interchangeable

terms.

The statutory phrase “ other place of exhibition or

entertainment” must refer to establishments similar to

those expressly mentioned. When one considers the ex

hibitions and entertainment offered by motion picture

houses, theatres, concert halls, sports arenas and stadiums,

it is clear at once that basically patrons of such establish

ments are edified, entertained, thrilled, or amused in their

capacity of spectators or listeners; their physical partici

pation in what is being offered to them is either non-exist

ent or minimal; their role is fundamentally passive.

The difference in what is offered by the establish

ments named in section 201(b)(3) and what is offered at

Lake Nixon and Spring Lake is obvious. The latter es

tablishments do not offer “ entertainment” in the sense in

which the Court is convinced that Congress used the word;

what they offer primarily are facilities for recreation

whereby their patrons can enjoy and amuse themselves.

In adopting section 201(b)(3) Congress must have

been aware that “ entertainment” and “recreation” are not

synonymous or co-extensive, and had Congress intended

to provide coverage with respect to a “place of recreation,”

it could have said so easily. The Court thinks that it is

quite significant that neither the category in question nor

any other category mentioned in section 201(b) makes

any mention of swimming pools, or parks, or recreational

areas, or recreational facilities. And the Court concludes

that establishments like Lake Nixon and Spring Lake do

not fall within section 201(b)(3) or any other category

appearing in that section as it is presently drawn.

In coming to this conclusion the Court has not over

looked the dancing which has gone on at both establish

ments or the diving exhibitions and fireworks display at

13a

Spring Lake. These exhibitions and that display were

isolated events which took place in 1965, which have not

been repeated, and which Mr. Culberson says will not be

repeated. They were insignificant anyway, and it ap

pears that the diving, which was done by life savers em

ployed by Spring Lake, was not so much for the purpose

of entertaining patrons as to demonstrate to them the

competency of the life saving personnel.

As to the dancing, there are two things to be said:

first, the dances held at Spring Lake play no significant

part in the operations of that establishment, and the part

played by the dances held regularly at Lake Nixon would

seem to play a minor role in the Lake Nixon operation.

Second, and more basically, it seems to the Court that

dancing, whether to “ live music” or to records played on

a juke box, falls more within the concept of “recreation”

than within the concept of “ entertainment” .

But, even if it be conceded to plaintiffs that the chal

lenged establishments are “places of entertainment,” the

Court cannot find that under the law their operations af

fect interstate commerce. Certainly, the racial discrimi

nation which the defendants have practiced has not been

supported by the State of Arkansas or any of its political

subdivisions.

Referring to section 201(c), the criterion which it

establishes for the determination of whether a place of

exhibition or entertainment “ affects commerce” is whether

the establishment in question customarily presents films,

performances, athletic teams, exhibitions or other sources

of entertainment which move in commerce.” (Emphasis

supplied.)

The emphasized words are not without significance

when read in comparison with the statutory criterion for

determining whether the operations of an eating estab

lishment affect interstate commerce. With regard to

such an establishment it is sufficient if it has served or

offered to serve interstate travelers or if a substantial

portion of the food which it serves has moved in inter

14a

state commerce. There is a distinct difference between

person or thing which moves in interstate commerce and

a person or thing which simply has moved in interstate

commerce.

As indicated, there is no evidence here and no rea

son to believe that the local musicians who play for the

dances at Lake Nixon and Spring Lake have ever moved

as musicians in interstate commerce or that they are now

doing so. Nor do the juke boxes, the records and other

recreational apparatus, such as boats, utilized at the re

spective establishments “move” in interstate commerce,

although it is true that the juke boxes, some of their rec

ords, and part of the other recreational equipment and ap

paratus were brought into Arkansas from without the

State.

The Court’s approach to and its solution of the prob

lems presented by these cases find full support in the

opinion of Judge West in Miller v. Amusement Enter

prises, Inc., E.D. La., 239 F.Supp. 323, a case involving a

privately owned amusement park in Baton Rouge, Louisi

ana.®

From what has been said it follows that a decree will

be entered dismissing the complaints in the respective

cases.

Dated this 1st day of February, 1967.

s / J. Smith Henley

United States District Judge

5That case was decided on September 13, 1966, and the opinion

was published on December 12 of that year after the instant cases

were tried.

15a

Decree

These two cases having been consolidated for purposes

of trial and having been tried together, and the Court

being well and sufficiently advised, and having filed

herein its opinion incorporating its findings of fact and

conclusions of Law in both cases,

It is by the Court Considered, Ordered, Adjudged,

and Decreed that plaintiffs in said cases take nothing by

their complaints, and that both of said complaints be, and

they hereby are, dismissed with prejudice and at the cost

of plaintiffs.

Dated this 1st day of February, 1967.

s / J. Smith Henley

United States District Judge

16a

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 18,824

Mrs. Doris Daniel and Mrs. Rosa->.

lyn Kyles,

Appellants,

v.

Euell Paul, Jr., Individually and as

Owner, Operator or Manager of

Lake Nixon Club,

Appellee.

A p p e a l from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Eastern District of

Arkansas.

[May 3, 1968.]

Before V an Oosterhotjt, Chief Judge; Mehaffy and

Heaney, Circuit Judges.

Mehaffy, Circuit Judge.

Doris Daniel and Rosalyn Kyles, plaintiffs-appellants,

Negro citizens and residents of Little Rock, Pulaski County,

Arkansas, were refused admission to the Lake Nixon Club,

a recreational facility located in a rural area of Pulaski

County and owned and operated by the defendant-appellee

Euell Paul, Jr. and his wife, Oneta Irene Paul. Plaintiffs

17a

brought this suit seeking injunctive relief from an alleged

discriminatory policy followed by defendant denying Ne

groes the use and enjoyment of the services and facilities

of the Lake Nixon Club.1 This suit was brought as a class

action under Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

P.L. 88-352, §§ 201 et seq., 78 Stat. 243 et seq., 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000a et seq., alleging that the Lake Nixon Club is a

“ public accommodation” as the term is defined in the Act,

and that, therefore, it is subject to the A ct’s provisions.

For the purpose of trial this case was consolidated with

a similar suit brought by plaintiffs against Spring Lake

Club, Inc. The trial was to Chief District Judge Henley

who held that neither Lake Nixon Club nor Spring Lake,

Inc. was a “ public accommodation” as defined in and

covered by Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and

ordered dismissal of the complaints. We are concerned

solely with the court’s decision with regard to Lake Nixon

Club, since there was no appeal from the portion of the

decision regarding Spring Lake, Inc. Chief Judge Henley’s

memorandum opinion is published at 263 F.Supp. 412. We

affirm.

The plaintiffs alleged in their complaint that the Lake

Nixon Club is a place of public accommodation within the

meaning of 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000a et seq.; that it serves and

offers to serve interstate travelers; that a substantial por

tion of the food and other items which it serves and uses

moves in interstate commerce; that its operations affect

travel, trade, commerce, transportation, or communication

among, between and through the several states and the

District of Columbia; that the Lake Nixon Club is oper

ated under the guise of being a private club solely for

i At the trial, an oral amendment was made and accepted making

Mrs. Paul a party to the action.

18a

the purpose of being able to exclude plaintiffs and all

other Negro persons; and that the jurisdiction of the court

is invoked to secure protection of plaintiffs’ civil rights

and to redress them for the deprivation of rights, privi

leges, and immunities secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, Section 1;

the Commerce Clause, Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of

the Constitution of the United States; 42 U.S.C. § 1981,

providing for the equal rights of citizens and all persons

within the jurisdiction of the United States; and Title II

of the Civil Eights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 243, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000a et seq., under which they allege that they are

entitled to an injunction restraining defendant from deny

ing them and others similarly situated admission to and

full use and enjoyment of the “ goods, services, facilities,

privileges, advantages, and accommodations” of the Lake

Nixon Club.

The defendant denied that Lake Nixon is a place of

public accommodation within the meaning of the Act;

denied that Lake Nixon serves or offers to serve inter

state travelers or that a substantial portion of the food

and other items which it serves and uses moves in inter

state commerce; denied that its operations affect travel,

trade, commerce, transportation or communication between

and through the several states and the District of Columbia

within the meaning of the Act; and, further answering,

averred that defendant operates Lake Nixon Club as a

place to swim; that he has a large amount of money in

vested in the facility; that if he is compelled to admit

Negroes to the lake, he will lose the business of white

people and will be compelled to close his business; that the

value of his property will be destroyed: and that he will

be deprived of his rights under the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.

19a

The provisions of the Civil Eights Act of 1964 which

define “ a place of public accommodation” as covered by

the Act, and which plaintiffs contend bring the Lake Nixon

Club within its coverage, are contained in 42 U.S.C. § 2000a

(b), and provide as follows:

“ (b) Each of the following establishments which

serves the public is a jjlace of public accommodation

within the meaning of this subchapter if its operations

affect commerce, or if discrimination or segregation

by it is supported by State action:

“ (1) any inn, hotel, motel, or other establishment

which provides lodging to transient guests, other

than an establishment located within a building

which contains not more than five rooms for rent

or hire and which is actually occupied by the pro

prietor of such establishment as his residence;

“ (2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch

counter, soda fountain, or other facility prin

cipally engaged in selling food for consumption

on the premises, including, but not limited to, any

such facility located on the premises of any retail

establishment; or any gasoline station;

“ (3) any motion picture house, theater, concert

hall, sports arena, stadium or other place of ex

hibition or entertainment; and

“ (4) any establishment (A ) (i) which is physically