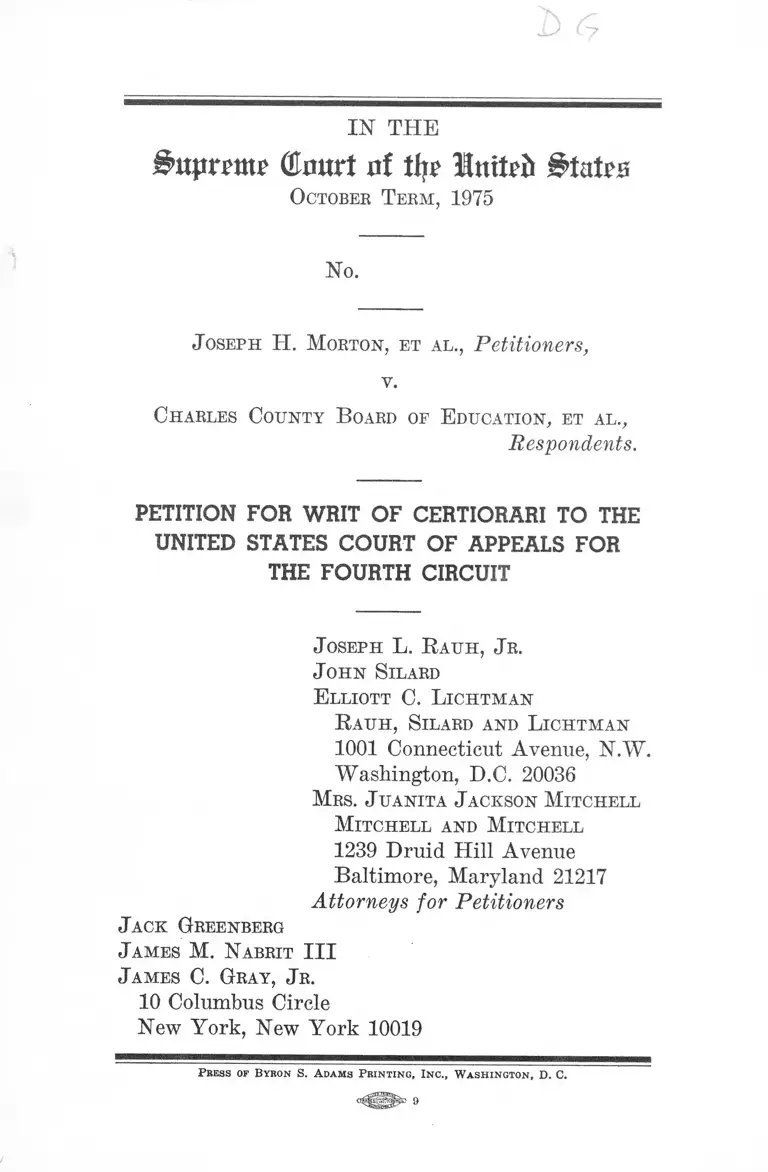

Morton v. Charles County Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Morton v. Charles County Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1975. 70dee3d2-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a5017a12-d296-4442-b446-43a8b68d38c6/morton-v-charles-county-board-of-education-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

(Emtrt uf tlir United States

Octobee Teem, 1975

No.

J oseph H. Moeton, et al., Petitioners,

v.

Chaeles County B oaed of Education, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

J oseph L. B auh, J e.

J ohn Silaed

E lliott C. L ichtman

R auh, Silaed and L ichtman

1001 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Mbs. J uanita J ackson Mitchell

Mitchell and Mitchell

1239 Druid Hill Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland 21217

Attorneys for Petitioners

J ack Geeenbeeg

J ames M. Nabeit III

J ames C. Gkay, Je.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Press of Byron S. A dams Printing, Inc., Washington, D. C.

\

INDEX

Page

Opinions B elow .................................................... ...................... 1

J u r is d ic t io n ................................................................ 1

Q uestions P r e s e n t e d ................................................................... 2

Constitutional and S tatutory P rovisions I nvolved 3

S tatem ent of the C a s e ......................................... 3

1. The Period of Segregation Prior to 1967 . . . . 4

2. Racially Discriminatory Employment Practices

Between 1967 and State Board Ruling in 1970 5

3. The State Board’s Discrimination Findings and

Remedial Orders ....................................................... 8

4. Continuing Employment Discrimination after

1970 .......................................................................... 10

5. The Complaint in This Case and the District

Court’s R u lin g ..................... 11

6. The Court of Appeals ’ Decision ...................... 12

R eason F or Granting T he W r i t : T his C o u rt ’s R e

view Is R equired T o I nsure D esegregation In

T he F aculty C omponent of F ormerly S egregated

P ublic S chool S ystems ........................... 13

I . ' The Decision Below Severely Erodes The Impor

tant Principle That Shifts the Burden of Justifi

cation to a School System Which Curtails Its

Black Faculty Component at the Time of Student

Desegregation ............................... 14

II. The Decision Below Erodes This Court’s Wright

Ruling by Refusing to Apply its Objective Stand

ard to the Faculty Desegration Area .................... 17

III. A Major Constitutional Issue Arises From the

Lower Court’s Refusal to Honor and Give Effect

to The State’s Own Findings of the School

Board’s Discriminatory Practices ....................... 19

Conclusion ................... 24

11 C IT A T IO N S

Cases : Page

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) ......... 16

Brewer v. Hoxie School District, 238 F.2d 91 (8th

Cir. 1956) ..................................................................... 22

Broivn v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) 4,15,17

Brown v. Gaston Co. Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d

1377, (4th Cir. 1972) ............................. ................ . 17

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972) .......... 19

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

364 F.2d 189 (1966) ....................................... 2,12,14,16

The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883 ).................... 21

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, (1880) ..................... 21

Gomillion v. Light foot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ............. 21

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) . .13,17

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .......... 19

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 413

U.S. 189 (1973) ......................................................2,12,14

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) ...................... 22

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ....................... 17

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974) ........................................................... 17

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, (1964) ....................... 21

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ............................. 16

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir.

1972) ........................................... 17

Swann v. Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) . .13,16,17

Trenton v. New Jersey, 262 U.S. 182 (1923) ................ 21

United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715 (1966) . . 22

Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d

387 (2nd Cir. 1973) ................................................. 19

Williams v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 289

U.S. 36 (1933) ........................................................... 21

Wilson v. Board of Education, 234 Md. 561, 200 A.2d

67 (1964) .................................................................... 22

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) ............................................................. 2,12,17,18

Citations— Continued in

Page

C onstitutions and S tatutes :

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment

passim

United States Code:

28 U.S.C. § 1254 (1) ................................................. 2

28 U.S.C. § 1331 ......................................................... 11

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ......................................................... 11

28 U.S.C. § 1739 ............................. .......................... 22

Emergency School Aid Act (20 U.S.C. §§ 1601 et seq) 6

Maryland Constitution, Article VIII § 1 ...................... 20

Maryland Code

Article 77, § 6 ............................................................. 20

Article 77, § 113 .................................................... 20, 21

M iscellaneous :

Amicus Curiae Brief of National Education Associa

tion in United States v. Georgia (5th Cir. No.

30,338) 14

Hearings Before Senate Select Committee on Equal

Educational Opportunity, 91st Cong., 2nd Sess.

(1970), 92nd Cong. 1st Sess. (1971) ..................... 14

-

IN THE

(Euurt ni % Intteii States

October Term, 1975

No.

J oseph H. Morton, et al., Petitioners,

v.

Charles County B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOB

THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Joseph H. Morton, et al., petition for a writ of

certiorari to review the Judgment and Opinion of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Cir

cuit.

OPINIONS BELOW

The Opinion of the Court of Appeals (App. A, p.

la infra) is unreported at this time. The Judgment

is reproduced as Appendix B, p. 16a, infra. The Opin

ion of the District Court (App. C, p. 17a, infra) is

reported at 373 F.Supp. 394.

JURISDICTION

The Judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered

on July 24, 1975, and this petition for certiorari is

being filed within 90 days of that date. The jurisdic

2

tion of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254

( 1 ) .

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

In a racial discrimination case against a previously

segregated school system, where petitioners proved

that at the time of, and immediately subsequent to,

dismantlement of the segregated system

(a) the percentage of black teachers and prin

cipals sharply declined;

(b) the School Board made far greater efforts

to recruit whites than blacks;

(c) black teacher applicants had to meet

higher qualifications standards than white appli

cants; and

(d) assignments of teachers were made on the

basis of race

1. Did the majority of the Court of Appeals err in

declining, in accordance with Keyes (413 U.S. 189

(1973)) and Chambers (364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966)),

to hold that the burden shifts to the School Board to

justify its hiring and promotion practices by clear and

convincing evidence.

2. Did the majority of the Court of Appeals err in

declining to apply to the School Board’s hiring and

promotion practices the “ effect” discrimination test

under Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) rather than a racial motivation standard.

3. Did the Court of Appeals err in refusing to honor

the Maryland State Board of Education’s findings of

discriminatory faculty practices by Charles County

/

3

school officials, and in refusing to enforce the State

Board’s mandate that those practices, be discontinued.

4. Did the majority of the Court of Appeals err in

refusing to permit petitioners to maintain a class

action.1

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The pertinent portions of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, the United States Code and the Maryland Code

are set forth as Appendix D, p. 51a, infra.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case presents in bold relief a widespread prac

tice of school districts undertaking student desegre

gation to alter their faculty employment policies to

the prejudice of black teachers and administrators. It

arises in a “ Deep South” district whose student

bodies remained segregated until the late 1960s.2

When the Charles County Board of Education finally

desegregated its student bodies 13 years after Brown,

it immediately undertook radical changes in its faculty

1 While the class action question is presented in this case, we

do not make it a separate reason for granting the writ. I f certiorari

is granted, we will contend that the dissenting judge of the Court of

Appeals was correct on the cla«s action issue (see pp. 14a-15a, infra)

and that a reversal on the merits should be accompanied by reversal

on the class action question in order to provide fully effective relief.

8 Charles County was a ‘ ‘ Deep South ’ ’ community when it under

took student desegregation in 1967 and it remains so. As the in

vestigative Committee appointed by the Maryland State Board of

Education stated in its 1970 Report to the Board (A. 837), Charles

County “ is still basically a rural society. The races are segregated

socially and economically. . . . The traditions of the Deep South

run deep. The County as a whole still tends to be resistant to

change.” ( “ A ” references are to the Joint Appendix in the Court

of Appeals.)

4

hiring and promotion practices: prior to 1967 the fac

ulty of the school system had been almost 50% black,

and exactly half the schools had black principals. But

black teachers and principals deemed good enough for

black students were viewed by the school system in

a different light when it came to integrated schools and

classrooms. In 1967-68, when white students were

finally to be taught by black teachers, the school system

initiated new hiring and promotion practices which

resulted in the precipitous decline of the percentage of

the system’s black faculty and black principals. In

stead of continuing the half white, half black faculty

proportion, in 1967 the School Board began a consis

tent policy of hiring four white teachers for each black.

Moreover, while the number of black principals re

mained static, the number of white principals was

doubled. In a few short years the black teacher compo

nent dropped from 44% to 27% and the blacks de

creased from 50% to 30% in the school principal posi

tions.

The issues arising from this course of action by the

School Board with respect to the system’s faculty

component are of paramount importance, for they af

fect many hundreds of school districts across the na

tion required to develop unitary school systems and

manv thousands of black administrators, teachers and

applicants for employment with these districts. A brief

review of salient facts and the proceedings in this case

will place these issues in proper perspective:

1. The Period of Segregation Prior to 1987

For many years after this Court’s 1954 decision in

Broivn v. Board of Education, the Charles County

Board of Education continued to operate a segregated

5

school system. As late as the 1964-65 school year, only

296 black students attended white schools and only 2

white students attended black schools in a system

whose student enrollment number 8,999, of whom 45

percent were black (A. 707-09). Full student desegre

gation occurred for the first time in the 1967-68 school

year (A. 509-10, 707-13). While faculty segregation

had also been continued until the middle 1960’s, the

district had continued to hire and promote substantial

numbers of qualified blacks, although to teach or su

pervise almost exclusively black students. Thus in

1964-65, 50 percent of Charles County’s school princi

pals were black, and in the last year before student

desegregation, 44.2 percent of the teachers were black

(A. 129-32, 704-13, 1180).

2. Racially Discriminatory Employment Practices Between

1987 and State Board Ruling in 1970

When the Charles County Board of Education final

ly yielded to this Court’s rulings and integrated its

student bodies in 1967, this school system which had

previously hired an almost half-black faculty sud

denly changed its hiring and promotion practices.

This change occurred at the very moment that black

teachers and principals were reassigned to teach white

students. Thus, with the onset of student desegrega

tion, a school system which had previously hired al

most 50% black teachers began hiring four white

teachers for each black. That 80%-20% white-black

hiring quota which was implemented each year after

1967-68, soon caused a precipitous drop in the percen

tage of black teachers in the Charles County School

System. In the first year of student desegregation, the

44.2 percent black faculty dropped to 37.3 percent (A.

1180). By 1969-70, two years later, the black teacher

6

component had declined another 7 points, to 30.4 per

cent (A. 1180). Thus within the first three years after

desegregation of the student bodies, there was almost

a one-third decline in the proportion of black teachers

in the system. By the time of the 1973 trial, the black

teachers had decreased to 27 percent. Since respond

ents continued to hire according to the 4-1 ratio, the

faculty proportions continue to decline to an ultimate

one-fifth black faculty.

The sharp decline in black teacher hiring was paral

leled among black principals. Of the 16 principals in

1964-65, eight were black. In the very first year of full

student desegregation, there were twice as many

white principals (12) as blacks (6). By the time of

the 1973 trial, the number of black principals re

mained 8 while the number of white principals had

more than doubled, to 18 (A. 1125-32, 707-13, 129-32).3

The reduction in the black teacher-principal compo

nent is explained by the School Board’s recruiting and

hiring practices during the crucial post-1967 period of

student desegregation. Thus, between 1967 and 1970

3 In 1973 the Department of Health, Education and Welfare

investigated respondents’ application for funding under the Emer

gency School Aid Act (20 U.S.C. §§ 1601 et seq.) and denied it.

H EW wrote in a letter to the school district:

“ Your district has had a disproportionate reduction of black

principals since the 1964-65 school year. In 1964-65, there was

a total of 16 principals, of whom eight (8) were black and

eight (8) were white. In 1964-65, black principals represented

50 percent of the total number of principals in the district

and white principals represented 50 percent. However, in

1972-73, black principals represent 29 percent of the total

number of principals and white principals represent 71 per

cent of the total. Black principals have decreased by 25 per

cent over the period, while white principals have increased

by 137 percent.” (A .704-05).

7

Charles County recruited at 156 predominantly white

colleges, while visiting only 26 predominantly black

colleges. During that same period white recruiters

made visits on 197 occasions, while blacks made only

20 trips (A. 959-76, 871).

A comparison of the qualifications of black and

white persons hired during these years further dem

onstrates the discrimination in Charles County’s hir

ing practices. It was far easier for white applicants

to secure professional employment than for blacks

with comparable qualifications (A. 873-958). The

school system hired numerous whites without degrees

and with the lowest state qualifications, while hiring

virtually no blacks with such limited qualifications.4

Similarly, during these years, the white professional

employees hired by the school system generally had

less teaching experience than the blacks hired. More

over, among the teachers hired who did have teaching

experience, blacks had a greater average teaching ex

perience (id.). In sum, the record of diminishing

black faculty due to discriminatory recruitment prac

tices was bolstered by undisputed evidence that dis

parate qualification standards were applied.

In addition to limiting black hiring and leadership

in the years immediately following student desegre

gation, the school system also discriminated in its

assignment of blacks already employed. Between 1967

4 During the 1967-68 school year, 21 whites hired (16.2% of the

new white employees) had a 4, 5, or 6 state department certification

status, while only one black hired (2.7% of the new black em

ployees) had such a low rating. In the same year respondents hired

20 whites without college degrees while hiring only one, black

without a degree. For the two following years, the Charles County

school system hired 23 whites but only two blacks with a 4, 5, or 6

rating.

8

and 1970, respondents’ faculty assignments were ra

cially identifiable in almost two-thirds of its school

faculties, and the District Court did grant a declara

tory judgment with respect to these racial assign

ments (A. 1025-26, 1217-24).

Finally, the record shows that the school system

consistently employed a disproportionately low per

centage of blacks in central office administrative posi

tions, among the superintendent’s most immediate as

sistants and among secretaries, maintenance workers

and cafeteria managers. Only black custodians were

employed in high numbers (A. 808-09, 1179, 1161-66,

317-30, 1213-14, 1216, 977-1019).

3. The State Board's Discrimination. Findings and

Remedial Orders

The discriminatory practices just reviewed were the

subject of repeated complaints to the Charles County

Board of Education. When respondents failed to pro

vide any redress, a formal complaint of discrimination

was filed with the Maryland State Board of Edu

cation in 1969. Hearings were held by the State Board

in late 1969 and early 1970. Seventeen witnesses, in

cluding 3 of the individual petitioners herein, testified

concerning discrimination suffered by blacks in hir

ing, promotion, demotions and discharges (A. 783).

At the conclusion of the complainants’ testimony, the

State Board adopted a suggestion by Charles County

school officials and created a 4-member special com

mittee to investigate in Charles County “ the status of

integration, any deficiencies that can be noted, and

suggestions for future guidance” (id.). After a com

prehensive investigation (A. 393-98), the State

Board’s Committee issued a Report to the State

Board on April 24, 1970 which generally upheld the

9

allegations of racial discrimination in the School

Board’s hiring and promotion practices (A. 789-90,

792-95, 799-800, 804-05, 808-10, 813-16).5 In addition,

the Committee recommended corrective measures to

redress the discriminations found (A. 850-60). On

July 16, 1970, the State Board of Education upheld

the findings of its Committee and issued a series of di

rectives essentially adopting the remedial measures

suggested by the Committee (A. 862-70). The Board’s

remedial orders required sharp modification in the

school system’s hiring and promotion practices, or

dered deliberate and extensive recruitment of quali

fied black personnel, significant increases in recruiting

at black or predominantly black colleges by black re

cruiters, and. the adoption of a policy and practice of

employing, assigning and promoting black staff mem

bers in order to produce “ greater equity” and to “ in

sure black students a greater opportunity for motiva

tion and achievement” (A. 866-68).

6 For example, concerning the School Board’s hiring practices,

the Committee found:

“ The Committee stresses that whether or not the hiring prac

tices of the Charles County school system are or were pur

posely intended to exclude or keep to a minimum the number

of blacks employed, the hiring practices have had just that

effect. Whether or not the original intent was or is to discrimi

nate against blacks the result has been and is one of discrimi

nation” (A. 815).

On the School Board’s hiring and recruiting policies, the Com

mittee found:

“ . . . the evidence before the Committee does indicate that

Charles County school officials have fallen into de facto dis

criminatory hiring practices by following a procedure of

recruiting almost exclusively at predominantly white colleges,

using primarily white recruiters” (A. 793).

10

4, Continuing Employment Discrimination after 1970

Despite the findings and remedial directives of the

State Board in 1970, and the filing of this suit in 1971,

the Charles County Board of Education continued the

same discriminatory faculty practices. Respondents

continued to hire at the same 80 percent white-20 per

cent black ratio which caused a continuing drop in the

proportion of black faculty (A. 873-958, 1180). The

percentage of black principals remained low at 30

percent, the School Board adding three white princi

pals and only one black in the three years prior to the

1973 trial (A. 1176).

These hiring data reflected respondents’ continuing

discrimination in recruiting. Despite the State Board’s

Order requiring the Charles County Board of Educa

tion to engage in deliberate and extensive recruitment

of qualified black personnel and to place black staff

members on all recruiting teams, respondents contin

ued to visit far more white colleges than black colleges

with far more white than black recruiters. Moreover,

Die School Board’s continuing double standard to

ward white and black applicants was compounded,

when its Director of Personnel issued a 1971 directive

requiring that only “ superior” and “ above average”

black applicants be interviewed without placing any

such limitation on the interviewing and selection of

white applicants (A. 1119-21). Finally, the Charles

County system continued its racial assignment of

faculties despite the State Board’s express directive

that its school faculties must have “ balanced assign

ments” (A. 868). During the years between the State

Board ruling and the 1973 trial, about half of the

school faculty assignments were racially identifiable

(A. 1025-26, 1217-24).

11

5. The Complaint in This Case and the District Court's Ruling

When the County School Board failed to implement

the 1970 remedial directives of the Maryland State

Board of Education, six black applicants and employ

ees filed this action in 1971.6 They alleged individual

acts of employment discrimination and sought to rep

resent a class of blacks who had likewise been refused

employment or promotion or been demoted by re

spondents on grounds of race. The District Court

ruled that petitioners could not maintain a class ac

tion, but it allowed nine additional applicants and

employees to intervene as named plaintiffs. After a

trial at which petitioners presented the above record

of racially discriminatory actions and policies, the

District Judge rejected most of petitioners’ claims.

Although he found racial discrimination in faculty

assignments and in the failure to promote a single

black Vice-Principal, the District Judge gave these

findings no weight at all when he reviewed the specific

challenged actions of the school officials and their dis

criminatory general hiring policies. Despite the his

tory of segregation prior to 1967 and the unrefuted

proof that the Charles County Board of Education,

coincident with student integration, initiated vastly

Afferent hiring and promotion procedures which had

the effect of progressively reducing the black faculty

component, the District Judge refused to shift the

burden of proof to the School Board to explain its

hiring and promotion actions. In his view, “ [t]his

case is nothing like Chambers v. Hendersonville

Board of Education, 364 E.2d 189 (4 Cir. 1966)” be

cause the respondents had not discharged black fac

ulty at the time of desegregation (p. 29a infra).

6 Petitioners invoked jurisdiction of the District Court under

28 U.S.C. § 1331, 1343.

12

The District Court also declined to apply the prin

ciple of Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407

U.S. 451 (1972) : that even if not racially motivated,

desegregating school systems are proscribed from tak

ing actions which have the effect of impeding desegre

gation. Instead of granting relief against the Charles

County Board’s faculty employment actions, which

clearly had the effect of reducing the black faculty

component, the Court denied relief because of peti

tioners’ failure to prove to its satisfaction that the

School Board’s actions had been motivated by racial

prejudice (see, e.g., pp. 29a, 36a infra). Finally, the

District Court refused to honor, or give any iveight

at all to, the State Board of Education Committee’s

1970 finding of racially discriminatory faculty prac

tices by respondents, and the ensuing remedial orders

of the State Board itself directing abandonment of

those practices (pp. 26a-27a infra).

6* The Court of Appeals’ Decision

Dividing two to one, a panel of the Court of Ap

peals affirmed the District Court’s ruling on the

ground that the District Court properly placed the

burden of proof on petitioners because the 1967 stu

dent desegregation was “ voluntary” and because no

discharges of black faculty members accompanied the

desegregation. In the Court’s view, the immediate

precipitous drop in the hlack faculty proportion upon

integration of the student bodies was explained or

somehow justified by the expanding white student

population in the county. In short, the majority found

no justification to shift the burden of proof to the

School Board under this Court’s Keyes decision and

the Fourth Circuit’s Chambers ruling (pp. 5a-6a

infra).

13

A detailed critique of the District Court decision in

the dissenting opinion of Judge Butzner (pp. 10a to

15a infra) emphasized that the District Court ruling

was marred by two basic errors of law: (1) applica

tion of the Keyes-Chambers rule required that the

burden of proof should have been shifted to the School

Board because the Charles County school system had

a history of segregation and because the post-1967

hiring and promotion policies were shown to have a

racially discriminatory effect—a burden of explana

tion which the school system failed to meet; (2) ap

plying this Court’s Wright decision, the District

Court’s premise that petitioners were required to

show purposeful racial discrimination was fallacious.

In the “ reason for granting the writ” we urge that

vital questions are presented concerning the faculty di

mension of school desegregation, and that the narrow

distinctions espoused by the court below against the

governing authorities invite perpetuation among pub

lic school faculties of the racial segregation which

this Court has ordered eliminated “ root and branch” .

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 438

(1968).

REASON FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

THIS COURT'S REVIEW IS REQUIRED TO ASSURE EFFECTIVE

DESEGREGATION IN THE FACULTY COMPONENT OF

FORMERLY SEGREGATED PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEMS.

The major student desegregation undertaken

throughout the South under this Court’s Green and

Swann rulings has increased rather than reduced re

sistance to faculty desegregation. No problem has been

more unyielding in the process of school desegregation

14

than the substantial decline in the employment of black

teachers and supervisors which far too frequently has

occurred following the desegregation of pupils.7 This

case presents in clearest illumination practices in

dulged in by many school districts to continue discrim

ination and segregation in the faculty component of

the school system. Moreover, we urge the necessity of

this Court’s review because the lower courts’ refusal

to apply established Fourteenth Amendment princi

ples tangibly threatens the perpetuation in faculty em

ployment of the racism formerly practiced under com

pulsion of state law.

I. THE DECISION BELOW SEVERELY ERODES THE IM

PORTANT PRINCIPLE THAT SHIFTS THE BURDEN OF

JUSTIFICATION TO A SCHOOL SYSTEM WHICH

CURTAILS ITS BLACK FACULTY COMPONENT AT THE

TIME OF STUDENT DESEGREGATION.

In Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo

rado, 413 U.S. 189 (1973) this Court quoted and

adopted the holding of the Fourth Circuit in Cham

bers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education, 364

F.2d 189, 192 (1966) that “ . . . in a school system

with a history of segregation, the discharge of a dis

proportionately large number of Negro teachers in

cident to desegregation ‘ thrust[s] upon the School

Board the burden of justifying its conduct by clear

7 See Amicus Curiae Brief of National Education Association in

United, States v. Georgia, (5th Cir. No. 30,338) reproduced in

Hearings Before Senate Select Committee on Equal Educational

Opportunity, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970), 92d Cong., 1st Sess.,

(1971) (herein “ Hearings” ) pp. 5025, 5042, 5074; Hearings,

Part 10— ‘ ‘ Displacement and Present Status of Black School Prin

cipals in Desegregated School Districts, ’ ’ Appendix 5, pp. 5147-

5390; Hearings, “ NEA Report of Task Force Survey of Teacher

Displacement in Seventeen States,” pp. 1082,1124.

15

and convincing evidence.’ ” (413 U.S. at 209). In this

case, the majority below rejects the applicability of the

Keyes-Champers principle, because in Charles County

in 1967 student desegregation occurred “ voluntarily”

and because no actual discharge of black teachers oc

curred. Such a distinction disregards the underlying

meaning and purpose of the Keyes-C hampers rule.

»

While in Charles County the student desegregation

did not occur pursuant to a specific court order, its

ultimate action was belatedly undertaken to comply

with this Court’s order in Brown. Moreover, and more

importantly, while not discharging black teachers, the

School Board achieved the same result of curtailing

its black faculty component by initiating discrimina

tory hiring and promotion procedures. Thus a school

system with almost 50% black teachers suddenly began

hiring four white teachers for each black. In the very

first year following student desegregation, the black

faculty dropped from 44% to 37% ; and in two more

years to 30%. The four to one white-black hiring ratio

has continued each year after 1967, even after the

Maryland State Board of Education in 1970 expressly

ordered a sharp modification in the School Board’s

hiring and promotion practices and directed the de

liberate and extensive recruitment of qualified black

personnel. Just as Charles County initiated new

teacher hiring procedures at the time of desegregation,

it stopped promoting blacks to the important leader

ship position of school principal. While the number

of black principals remained static, whites were con

tinually appointed to these positions and more than

doubled in number, resulting in a decrease in the black

principal proportion from 50% to 30%.8

8 The majority of the Court of Appeals accepted respondents

argument that demographic changes in the Charles County popu

16

The School Board thus accomplished by its hiring

and promotion policies what the school board in

Chambers accomplished by discharges. As the dissent

ing Judge below stated:

“ The record demonstrates that, incident to de

segregation of the schools, the board disadvan-

tageously treated a disproportionately large num

ber of black personnel, not by discharge, as men

tioned in Keyes, but by its hiring and promotion

policies. For the purposes of shifting the burden

of proof, the difference between discharging black

teachers and refusing to hire or promote them is

inconsequential. The board’s practices, though

more subtle than outright discharge, nevertheless

disproportionately diminish the black faculty”

(p. 11a infra).

Though perhaps “ more subtle than outright dis

charge,” the subtlety of the hiring discrimination was

certainly not lost on the system’s black pupils who

perceived the sharp curtailment in the black faculty

proportion. From their point of view, the discrimina

tion was very real and, as this Court has held, the

impact of faculty discrimination on the students is the

paramount concern. Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198, 200

(1965) ; Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) ;

Swann v. Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 18 (1951).9

lation during the 1960-1970 decade somehow explained the precipi

tous drop in the black faculty component. But as Judge Butzner

persuasively pointed out in dissent, the record reflects that the

School Board “ does not look only to the availability of white

teachers living in the county, and for years both black and white

teachers have been recruited from colleges all over the country.

Consequently, the number of black applicants who live in the

county is irrelevant” (See p. 13a infra).

9 While this case involves school desegregation, it, of course, also

concerns employment discrimination. In cases of employment dis

crimination, statistical evidence has uniformly been held to estab-

17

During the middle and late 1960’s thousands of

Southern black school administrators and teachers

were discharged, demoted and refused employment at

the time of desegregation.10 The Chambers principle

which this Court adopted in its 1973 Keyes decision

provides an important deterrent to the continuation

of the practice of eliminating black faculty at the

time that these faculty members are assigned to teach

white children. Numerous school districts across the

country are still in the process of desegregation. The

pernicious effect of the majority opinion below is to

erode the important continuing protection furnished

by the Keyes-Chambers rule, which places a heavy

burden on the school district to justify its action. This

Court’s review is required where the opinion below

invites evasion of full desegregation by discriminatory

faculty hiring practices.

II. THE DECISION BELOW ERODES THIS COURT'S WRIGHT

RULING BY REFUSING TO APPLY ITS OBJECTIVE STAND

ARD TO THE FACULTY DESEGREGATION AREA.

In Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 IT.S.

451 (1972), this Court enunciated an important prin

lish a prim,a facie ease shifting the burden to the employer to

rebut the inference of discrimination arising therefrom. See, e.g.,

Crown v. Gaston Co. Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377, 1382

(4th Cir. 1972); Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348,

357-58 (5th Cir. 1972); Pettway v. Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d

211, 225, n. 34 (5th Cir. 1974). The lower courts surely erred in

failing to apply these authorities to petitioners’ pattern or practice

of discrimination claim. Moreover, in treating petitioners’ individ

ual clams of discrimination, the lower courts failed to shift the

burden of proof to the employer School Board in accordance with

the “ order and allocation of proof” set forth in this Court’s

opinion in McDonnell Douglas Corp. w. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800-04

(1973).

10 See p. 14 n. 7 supra.

18

ciple of school desegregation law flowing from Brown,

Green, and Swann: in evaluating a desegregating

school district’s actions it is the effect which is con

trolling rather than the motivation of school officials.

As stated in Wright (407 U.S. at 462), where the court

below had upheld creation of a new school district ‘ ‘ de

signed to further the aim of providing quality educa

tion” (442 F.2d 570, 572), the focus must be upon

“ the effect—not the purpose or motivation—of a

school board’s action in determining whether it is a

permisible method of dismantling a dual system. The

existence of a permissible purpose cannot sustain an

action that has an impermissible effect.”

The District Judge, affirmed by the ruling below,

refused to apply the Wright ‘ ‘ discriminatory effect”

test to the faculty practices of the Charles County

School Board. For example, in denying relief to pe

titioner William Griffis, a black principal for 16 years

in the segregated school system, who was demoted one

year after his school was integrated, the District Judge

•equired petitioner to prove that the demotion was

“ made on the basis of race, or because of any racial

prejudice” (p. 36a infra, see also p. 15a). As dissent

ing Judge Butzner emphasized, the District Court’s

Opinion contains a “ basic error of law that flaws this

case: the fallacious premise that the evidence must re

veal purposeful discrimination in order for the com

plainants to prevail” (p. 12a infra). To Judge Butz

ner’s conclusion that the Wright “ effect” test should

have been applied—- and that its application requires a

finding of unlawful School Board conduct here—the

majority below makes no response. Plainly, Judge

Butzner is correct in rejecting any operative distinc

tion which would make the Wright rule inapplicable

19

to the faculty component in school desegregation. This

Court’s review is thus required to vindicate the appli

cability of an “ effect” standard for desegregation of

the faculties of formerly segregated school systems no

less than their student bodies.

Moreover, the refusal by the Court below to apply

an objective standard to the School Board’s employ

ment policies sharply curtailing the black faculty com

ponent, cuts directly against the grain of this Court’s

objective standard in employment cases covered by

the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).11 Tinder Griggs, that is

true even though the employer has had no past segre

gation record such as existed in Charles County and

even though the private employer is free of constitu

tional limitations. Surely this Court ought review a de

cision which makes inapplicable to public employment

the objective standard of Griggs which now applies

in all private employment.

HL A MAJOR CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUE ARISES FROM THE

LOWER COURT'S REFUSAL TO HONOR AND GIVE EFFECT

TO THE STATE'S OWN FINDINGS OF THE SCHOOL

BOARD'S DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES.

The duties of the Maryland State Board of Educa

tion under the Fourteenth Amendment and state law

were duly invoked in 1969 by charges filed with the

Board alleging widespread discrimination against

11 "While Griggs was brought under Title V II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq.), its standards have generally

been applied in employment discrimination cases brought under

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983. See, e.g., Vulcan Society v. Civil

Service Commission, 490 F.2d 387, 394 n. 9 (2d Cir. 1973);

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725, 733 (1st Cir. 1972).

20

black faculty by Charles County school officials.12 Fol

lowing three days of hearings, the State Board ap

pointed a four member investigating committee. The

State Board’s Committee conducted a comprehensive

investigation and in April 1970 issued a unanimous

report. Finding respondent School Board guilty of

discriminatory practices and policies inhibiting the

hiring and promotion of black faculty, the State

Board’s Committee recommended corrective measures

to redress the discriminations found (A. 789-90, 792-

95, 799-800, 804-05, 808-10, 813-16, 854-59). Thereafter,

in July 1970 the State Board of Education itself up

held the findings of its Committee and issued direc

tives requiring respondent Charles County Board of

Education to modify sharply its hiring and promotion

practices and to deliberately and extensively recruit

qualified black personnel (A. 866-68).

While the District Court reluctantly received into

evidence the rulings of the State Board and its Com

mittee, it chose to disregard the findings of the State

Board’s Committee approved by the State Board.

Moreover, it declined to enforce or give any weight to

the requirements mandated by the State Board itself

12 Under the Constitution of the State of Maryland, responsi

bility for the operation and maintenance of the public education

system is placed upon the State (Maryland Constitution, Article

VIII, § 1). That State responsibility is vested in the State’s Board

of Education by Article 77 of the Maryland Code. Section 113

of Article 77 broadly prohibits any board of education from mak

ing “ any distinction or discrimination in favor of or against any

teacher . . . on account of race . . . with reference to . . . appoint

ment, assignment, compensation, promotion, transfer, dismissal,

. . . ” Under § 6 of the same Article, the State Board of Education

must “ cause the provisions of this article to be carried into effect” ,

and must “ decide all controversies and disputes that arise under

it, and their decision shall be final. ’ ’

21

seeking to end the faculty practices which were sharp

ly reducing the proportion of black teachers and prin

cipals in the Charles County school system (pp. 26a-27a

infra). The Court of Appeals similarly refused to

honor the State Board Committee’s findings or to

enforce the State Board’s remedial mandate that the

discriminatory faculty practices be discontinued

(pp. 8a-10a infra). Indeed, the majority even criti

cized the dissenting opinion’s reliance on the State

Board Committee’s Report and the State Board’s re

medial orders in finding a “ history of segregation” in

the Charles County system (p. 9a infra).

Thus the federal courts below have shrugged aside,

disregarded and declined to give effect to the State’s

own action, taken pursuant to its responsibility under

State law and under the Fourteenth Amendment.13 *

That Amendment provides that no “ state” shall deny

equal protection to its citizens, and it is settled that

the state itself bears the equal protection responsibility

for the discriminatory acts of its agents or subdivi

sions. See The Civil Rights Cases 109 U.S. 3 (1883);

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 347 (1880) ; Gomil-

lion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, 344-45 (1960); Reyn

olds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 575 (1964). Accordingly,

13 Both the Court of Appeals and the District Court state (pp.

9a, 27a infra) that the State Board and its Committee were not

charged with and did not purport to apply constitutional or sta

tutory standards. But in finding racially discriminatory employ

ment practices and in directing corrective action by the school

system, the State agency was discharging its duty to enforce the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. More

over, the State Board and its Committee were bound to enforce

Article 77, § 113 of the Maryland Code which essentially, dupli

cates the Fourteenth Amendment in prohibiting any Board of

Education from racial discrimination in matters of faculty em

ployment, promotion and assignment.

22

when the highest public education authority of Mary

land made an appropriate investigation resulting in

findings that its subordinate agency—the Charles

County School Board—-was engaging in discrimination

against black faculty and ordered corrective action,

the State was exercising its duty under the Fourteenth

Amendment precisely as the Amendment contemplates

and requires.14

An important question is thus raised by the lower

courts’ failure to give effect to the action properly

undertaken by the State Board under its equal pro

tection obligation, as well as under the State law bar

ring discrimination in faculty hiring. Given the high

importance of state respect for equal protection, the

state’s own compliance efforts are entitled to full

faith and credit in a federal litigation seeking Four

teenth Amendment remedies. Cf. Brewer v. Hoxie

School District, 238 F.2d 91 (8th Cir. 1956).15 The occa-

14 Moreover, under the Federal Constitution the State Board’s

ruling was binding on the Charles County Board of Education,

and it had no standing to challenge it. The Charles County Board

is a creature of the State of Maryland and cannot be heard in

federal court to challenge the rulings of the State Board of Edu

cation. Williams v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 289

U.S. 36, 40 (1933) ; Trenton v. New Jersey, 262 U.S. 182, 187-88

(1923). Since that is true even where as in Williams the sub

ordinate agency claims that the State is acting in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment, it is surely even more the case where,

as here, it is the State which has sought to secure Fourteenth

Amendment compliance and it is a subordinate School Board

which has flouted its remedial directives.

15 Since Maryland courts honor and give effect to remedial orders

of the State Board of Education (see Wilson v. Board of Educa

tion, 234 Md. 561, 563-66, 200 A.2d 67, 68-70 (1964)), the federal

courts below should have done the same as a matter of pendent

jurisdiction. United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U S 715 725

(1966) ; cf. 28 U.S.C. § 1739.

23

sions on which officials of the formerly segregated

states have themselves undertaken forthright correc

tive action in the school desegregation area are un

fortunately few and far between. Cf. McDaniel v.

Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971). Surely when that hap

pens, as here, federal courts cannot disregard that

action, giving a clean bill of health to School Board

officials for the same conduct which the State has

found racially discriminatory.

Maryland having found generally discriminatory

hiring and promotion policies practiced by the Charles

County Board of Education and having ordered their

discontinuance, there was provided to the District

Court an additional predicate for award of injunctive

and compensatory relief. Thus, both as a matter of

legal compulsion and as a matter of comity and judicial

wisdom, the lower courts should have given appropri

ate effect to Maryland’s discrimination findings and

remedies. Their failure to do so presents an important

additional question for this Court’s review.

24

CONCLUSION

For the several separate and compelling reasons

stated, the writ should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J oseph L . R auh, J r .

J ohn Silard

Elliott C. L ichtman

R auh, Silard and L ichtman

1001 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Mrs. J uanita J ackson M itchell

Mitchell and M itchell

1239 Druid Hill Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland 21217

Attorneys for Petitioners

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. X aiu;it I I I

J ames C. Gray, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX A

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOE THE FOUETH CIRCUIT

Nos. 74-1817 and 74-1818

J oseph H . M orton, W illiam L. Griffis, M elbourne F.

H ull, V eronica A dams, A nnie C. Y ates, M ary L inda

Plater, infant, through her father, Charles L. Plater,

Sr., M ary T heresea W ashington, infant, through her

mother, M rs. D oris C. W ashington, Cordelia E. K ing,

E lnora P in kn ey , Raymond F. Sanderlin, H erome F.

T hompson, L acey T illotson, Sandra W ashington

H earns, K enneth W right, J oseph A . J ones, B ertha

K ey,

versus

Charles County B oard of E ducation, J ames E. W ilson,

individually and as a member of the Charles County

Board of Education, B. Patrick Cox, individually and

as a member of the Charles County Board of Educa

tion, Joseph L. Gardiner, individually and as a mem

ber of the Charles County Board of Education, D aniel

C. Gardner, individually and as a member of the

Charles County Board of Education, Joan L. B owling,

individually and as a member of the Charles County

Board of Education, Mrs. A lfred Paretta M udd, in

dividually and as a member of the Charles County

Board of Education, Jesse L. Starkey, individually

and as Superintendent of Schools, Charles County,

Maryland, Charles County Board of Education,

Appellees-Appellants

Cross-appeals from the United Staes District Court for

the District of Maryland, at Baltimore. Roszel C. Thom

sen, Senior District Judge.

Argued March 5, 1975 Decided July 24, 1975

2a

Before B ryan, Senior Circuit Judge, and B utzner and

F ield, Circuit Judges.

Elliott C. Lichtman (Joseph L. Rauh, Jr., John Silard,

Rauh and Silard, Mrs. Juanita Jackson Mitchell, Mitchell

and Mitchell, Jack Greenberg, James M. Nabrit, III, Nor

man Chachkin and James C. Gray, Jr., on brief) for Ap

pellants in No. 74-1817 and Appellees in 74-1818; William

L. Marbury and E. Stephen Derby (Judith K. Sykes, Ed

ward S. Digges and Richard J. Clark on brief) for Appel

lees in No. 74-1817 and Appellants in No. 74-1818.

F ield, Circuit Judge:

This action was instituted in January of 1971 by eight

black individuals alleging discriminatory conduct in the

operation of the public school system of Charles County,

Maryland. Six of the plaintiffs were adults who charged

that they and the class of individuals which they purported

to represent had been refused employment or promotion,

or had been demoted or discharged by the defendants on

grounds of race. The other two plaintiffs were infants who

were students in the Charles County School System and

alleged that they sued on behalf of themselves and as rep

resentatives of a class consisting of all black students in

the school system who were being deprived of their civil

rights because the defendants had maintained racially

identifiable faculties. The parties engaged in broad and

exhaustive discovery procedures and on November 9, 1973,

the court determined that the prerequisites to a class ac

tion had not been met by either the adult or infant plain

tiffs. Thereafter, nine additional adults moved to inter

vene as plaintiffs, alleging that they had been the victims

of racial discrimination on the part of the defendants.

The district court conducted a twelve-day trial and filed

an opinion in which it engaged in a meticulous review of

the evidence and made detailed findings of fact. The claims

3a

of discrimination of the fourteen adult plaintiffs1 were

carefully examined and with the exception of one claim

were found to be without merit. In the case of Mrs. Elnora

Pinkney the court found that the failure to appoint her as

principal of an elementary school in 1969 was the result

of racial discrimination. With respect to the claims of the

student plaintiffs relative to the racial composition of

faculties, the court found that the School Board had at

tained an appropriate faculty ratio as required by Nesbit

v. Statesville City Board of Education, 418 F.2d 1040 (4

Cir. 1969), in all but five of its twenty-six schools.2 The

court noted that in three of these five schools the shifting

of one teacher would bring the school into conformance

with the test suggested by the plaintiffs and that in all

other schools the shifting of only two teachers would he

necessary. The only school falling substantially below this

test was the Vocational Educational Center which included

a number of specialized faculty positions.

Based upon the findings in its opinion the court entered

an order which (1) granted judgment in favor of the de

fendants with respect to the claims of all the adult plain

tiffs with the exception of Mrs. Pinkney; (2) declared that

the ratio of black and white faculty members in each

school should be not less than 75 per cent nor more than

125 per cent of the ratio of black teachers throughout the

system ;3 * (3) granted judgment in favor of Mrs. Pinkney

1 After tlie institution of this suit one of the plaintiffs, Ortis J.

Cobb, was permitted to withdraw as a party plaintiff on October

12, 1972.

2 The plaintiffs suggested that the standard of Nesbit would be

met where the ratio of black teachers to white teachers in each

public school in the county was not less than 75 per cent nor

more than 125 per cent of the ratio of black teachers to white

throughout the entire system.

3 On this issue the court accepted the standard suggested by the

plaintiffs. See, n.2, supra.

4a

in the amount of $15,796, being the difference between the

salary actually paid to her and the salary she would have

received as principal of an elementary school for the years

1969 to 1974;4 and (4) awarded attorneys’ fees of $12,000

payable to counsel for Mrs. Pinkney and the infant plain

tiffs.

Upon their appeal, the plaintiffs request that we re

verse the judgment of the district court and direct that it

take the following remedial measures. First, grant declara

tory and injunctive relief prohibiting continuance of the

hiring, promotion and demotion practices which plaintiffs

allege have caused continued attrition in the percentage

of black faculty members in the school system. Second,

issue an injunction requiring the institution of affirmative

hiring, promotion and demotion policies designed to restore

the ratio of black principals and teachers to that which

existed in the school system at the time desegregation was

undertaken. Third, set aside the adverse findings made by

the district court against the thirteen adult plaintiffs, and

reconsider their claims by applying a presumption of racial

discrimination and placing upon the defendants the burden

of proving that discriminatory policies played no part in

the rejection, non-promotion or demotion of each individ

ual plaintiff. Fourth, award compensatory and other relief

to all members of the class of unsuccessful black appli

cants for promotion and hiring in the Charles County

School system since 1968.5

4 The Board was further directed to compensate Mrs. Pinkney

on the basis of a principal’s salary until her retirement and to

make such additional contributions to the Maryland Teachers Re

tirement System on her behalf as would have been made had she

held the position of principal since 1969.

5 The plaintiffs contend that the alleged discriminatory practices

injured all unsuccessful black applicants for positions in the Charles

County school system and that the district court plainly erred in

refusing to permit the plaintiffs to pursue their class action. They

further suggest “ that a special master could be appointed to receive

5a

Primarily the plaintiffs contend that the district court

failed to give the appropriate presumptive weight to the

statistical evidence of racial discrimination in the Board’s

employment practices. They point to the fact that whereas

in 1966-67, the year prior to complete desegregation, 44.2

per cent of the teachers were black, the proportion of black

teachers had declined to 30.4 per cent in 1969-70, and that

in the same years the percentage of black principals had

dropped from 37.5 per cent to 30.7 per cent. These sta

tistics, the plaintiffs argue, call for the invocation of the

principle set forth in Chambers v. Hendersonville City

Board of Education, 364 F.2d 189, 192 (4 Cir. 1966), that

“ in the face of the long history of racial discrimination

* * * the sudden disproportionate decimation in the ranks

of Negro teachers raise[s] an inference of discrimination

which thrust[s] upon the School Board the burden of justi

fying its conduct by clear and convincing evidence.” The

district judge rejected this contention of the plaintiffs, and

we agree with him that this is not a Chambers case. First

of all, unlike Chambers where the school system resisted

“ the mandate of Brown until forced to do so by litigation,”

Id. at 192, the Charles County Board had taken affirmative

steps to desegregate its schools in the light of the evolving

law and it is conceded that complete desegregation in the

county had been voluntarily accomplished in 1967. Also,

unlike Chambers, in the present case there was no sudden

disproportionate decimation in the ranks of Negro teachers

incident to the complete integration of the school system. On

the contrary the district judge found that ‘ ‘ there is no claim

or evidence that any teacher or principal was discharged

because of his or her race.” Common to Chambers and its

progeny in this circuit6 was the fact that in each case a sub

file individual applications for reliefs,” with directions that the

master apply the presumption of discrimination set out in “ Third”

above.

6 See, Walston v. County School Board of Nansemond Cty., Va.,

492 F.2d 919 (4 Cir. 1974) ; North Carolina Teachers Ass’n. v.

Asheboro City Bd. of Ed., 393 F.2d 736 (4 Cir. 1968).

6a

stantial number of black teachers had been discharged when

the schools were integrated, and the significance of this

factors was recognized by the Court in Keyes v. School

District No. 1, Denver, Colo., 413 U.S. 189̂ 209 (1973),

where the Court stated:

‘ ‘ Again, in a school system with a history of segrega

tion, the discharge of a disproportionately large num

ber of Negro teachers incident to desegregation

‘‘ trust[s] upon the School Board the burden of justify

ing its conduct by clear and convincing evidence’.”

(Emphasis added).

In addition to the foregoing, the record clearly demon

strates that the statistical changes upon which the plain

tiffs rely so heavily were not the result of any discrimina

tory hiring policies of the Board, but rather were the result

of dramatic demographic changes which occurred in Charles

County in the 1960-1970 decade. Charles County is a small

county in southern Maryland which is experiencing rapid

growth as the suburbs of the District of Columbia expand.

Between 1960 and 1970 the population increased 46.4 per

cent from 32,500 to 47,700. In that same period the number

of students in public schools increased from 7,400 in 1960

,o 13,000 in 1970, and had further increased to 16,300 in

1973. This rapid growth in both population and school en

rollment consisted primarily of an increase in white popu

lation and white pupils. While in 1970 the black population

of the county had slightly increased in absolute numbers,

the percentage of black population had declined from 34

per cent in 1960 to 29 per cent in 1970; and the percentage

of blacks in the school population had declined from 45.7

per cent in 1960 to 39.9 per cent in 1970 and dropped even

lower to 34 per cent in 1973.

During this same period the number of black principals

in the school system increased from six to eight and in 1973

stood at 30.7 per cent while the number of black vice-prin

cipals increased from four to six and reached about 45 per

cent. The number of black administrators in the central

7a

office of the school system increased from four to ten, being

22 per cent of that job classification. The number of black

teachers had increased from 198 to 207, although the per

centage decreased to 27 per cent. The district court care

fully analyzed the school statistics in the light of the per

centage decrease of blacks in the general population as well

as the school system, and also took into consideration the

statistical data bearing upon the percentage of blacks in

the relevant employment pool from which the School Board,

of necessity, drew a substantial number of its employees.

Upon consideration of all of the relevant statistical data

and underlying evidence bearing thereon, the district judge

concluded that the evidence did not disclose a pattern of

racial discrimination which required or justified the appli

cation of the so-called Chambers rule. The record solidly

supports the findings of the district court and, assuredly,

they are not clearly erroneous.7 Williams v. Albemarle City

Board of Education, 485 F.2d 232 (4 Cir. 1973); jBridgeport

Guard., Inc. v. Members of Bridgeport C. S. Com’m., 482

F.2d 1333 (2 Cir. 1973).

The proposal of the plaintiffs that the court direct the

Board to institute an affirmative policy which will restore

the ratio of black principals and teachers to that which

existed in the system prior to desegregation of the schools

7 In Mayor v. Educational Equality League, 415 II.S. 605 (1974),

the Court criticized the use of “ simplistic percentage comparisons”

and observed:

“ We share the view expressed in the dissent that facts in

a case like the instant one, ‘ when seen through the eyes of

judges familiar with the context in which they occurred, may

have special significance that is lost on those with only the

printed page before them.’ * * * That is one reason why we

believe that the Court of Appeals, ‘with only the printed page

before [it] . . . , ’ erred in reversing the District Court. The

judge most ‘ familiar with the context in which [the facts]

occurred . . . ’ was obviously the District Judge, since he heard

and viewed the testimony and other evidence presented.” Id.,

at 620, n.2Q.

8a

would require the court to close its eyes to the changes

which have taken place in Charles County during the past

ten years. We are unaware of any constitutional principle

which would require that the racial ratios which existed

in the school system of the county in 1966-67 be rigidly

maintained ad infinitum despite the changing character of

the surrounding area. On the contrary, the inevitability of

such changes was recognized by the Chief Justice in Swann

v. Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 31-32 (1971).

“ It does not follow that the communities served by

such systems will remain demographically stable, for

in a growing, mobile society, few will do so. Neither

school authorities nor district courts are constitution

ally required to make year-by-year adjustments of the

racial composition of students bodies once the affirma

tive duty to desegregate had been accomplished and

racial discrimination through official action is elim

inated from the system. This does not mean that fed

eral courts are without power to deal with future prob

lems; but in the absence of a showing that either the

school authorities or some other agency of the State

has deliberately attempted to fix or alter demographic

patterns to affect the racial composition of the schools,

further intervention by a district court should not be

necessary.’ ’

In our opinion the present case falls within this observation

of the Chief Justice, and the record satisfies us that despite

the changing population ratio the Board has taken reason

able and affirmative steps to bring substantial numbers of

qualified blacks into every facet of the school system.

Finally, a brief comment about the special committee re

port upon which the dissent appears to place considerable

reliance. In the spring of 1969 a dispute arose over the

selection of majorettes at La Plata High School and at the

suggestion of the Board of Education and the N A A CP a

committee was appointed by the State Board of Education

to make an investigation of a variety of complaints and

report its recommendations to the Board. The committee

9a

was purely of an ad hoc nature and, as noted by the district

judge, was not charged to apply either constitutional or

statutory standards in its investigation. The committee’s

investigation was not conducted as an adversary proceeding

nor were the individuals interviewed by it subject to cross-

examination. The State Board discussed the committee re

port with representatives of the Charles County school sys

tem and the NAACP and thereafter adopted some of the

committee’s recommendations, modified some and refused

to adopt others. Again, as noted by the district judge, the

action of the State Board on the report did not purport to

be based upon either constitutional or statutory principles.8

While the dissent does not go so far as to accept the

plaintiffs’ contention that the district court was bound by

the committee report and had a responsibility to enforce its

findings as well as the recommendations of the State Board,

it nevertheless relies upon the report as demonstrating “ a

history of segregation” under the Keyes formula. This, we

think, accords the report an unwarranted role in this litiga

tion. While the district judge permitted the committee re

port to be introduced into evidence, he ultimately reached

the conclusion that its relevant findings lacked support and

made his independent findings based on the evidence before

him. In doing so he acted well within the permissible area

of his discretion. Even if the report were conceded some

official gloss its admissibility would be highly questionable,

see Moss v. Lane Company, Incorporated, 471 F.2d 853 (4

Cir. 1973); Cox v. Babcock and Wilcox Company, 471 F.2d

13 (4 Cir. 1972), and in any event, it “ is in no sense binding

on the district court and is to be given no more weight than

any other testimony given at trial.” Smith v. Universal

8 It was conceded by the plaintiffs that none of them had seen fit

to pursue the available Maryland statutory remedy by which a

person aggrieved by actions of the county school administration

may present a complaint to the School Board and, if dissatisfied

with the action of the Board, appeal to the State Board of Educa

tion. Anno. Code of Md., Art. 77 § 59 (1969 Repl. Vol.)

10a

Services, Inc., 454 F.2d 154, 157 (5 Cir. 1972). The fallacy of

placing any operative reliance on the report is more readily

apparent if we reverse the circumstances. Had the state

committee given carte blanche approval to the manner in

which the Charles County schools were being operated, we

doubt that anyone would seriously contend that such a re

port would constitute a defense to the plaintiffs’ law suit or

that it would be entitled to any substantial evidentiary con

sideration on the issues.

In our opinion the district court granted full and appro

priate relief and we affirm its judgment in all respects.9

AFFIRMED

B utzner, Circuit Judge, dissenting: ,

This case reaches the wrong result because of two basic

errors of law. The first error is the allocation of the bur

den of proof, which was placed on the black complainants.

It should have been placed on the school board in con

formity with Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver Colo

rado, 413 U.S. 189, 209 (1973), which teaches that “ in a

school system with a history of segregation, the discharge

of a disproportionately large number of Negro teachers

incident to desegregation ‘ thrust [s] upon the School Board

the burden of justifying its conduct by clear and convinc

ing evidence.’ ” Therefore, the initial inquiry should be

to determine whether the Charles County school system

has a history of segregation.

Until 1954 the county board operated a dual system, and

not until 1967 were all of the schools desegregated. In the

course of integrating the pupils, the racial composition of

faculties underwent changes that were investigated by a

special committee appointed by the Maryland State Board

9 The cross-appeal of the Board of Education challenges the

award of damages to Mrs. Pinkney, but we are not persuaded that

the finding of the district court on her claim was clearly erroneous.

11a

of Education. The committee filed an extensive report con

demning the racial discrimination practiced by the school

board in hiring and promoting the schools’ professional

and administrative staffs. The State Board of Education

approved the committee’s recommendations calling for the

extensive recruitment of qualified black personnel and the

establishment of fair and clear procedures for promotion

that would apply equally to all candidates. When it became

apparent that the school board was disregarding these

recommendations, black students, parents, and faculty in

stituted this action. The first factual predicate for shifting

the burden of proof mentioned by Keyes is “ a history of

segregation.” The school board’s former operation of a

dual system of schools and the report of the State Board

of Education amply demonstrate that this prerequisite

has been met.

The second element of the Keyes- formula is also satis

fied. The record demonstrates that, incident to desegrega

tion of the schools, the board disadvantageously treated a

disproportionately large number of black personnel, not by

discharge, as mentioned in Keyes, but by its hiring and

promotion policies. For the purposes of shifting the bur

den of proof, the difference between discharging black

teachers and refusing to hire or promote them is incon

sequential. The board’s practices, though more subtle than

outright discharge, nevertheless disproportionately dimin

ish the black faculty. The record shows that when the

pupils were segregated, 50 percent of the principals were

black and 50 percent were white. After desegregation of

the schools, the percentage of black principals decreased

to 30 percent and that of white principals increased to

70 percent. Before desegregation, black teachers consti

tuted 44.2 percent of the faculties, but by 1973 the ratio

had dropped to 27.4 percent.

I therefore conclude that both of K eyes’ factual pre

requisites for shifting the burden of proof have been satis-

12a

fied and that it was error to fail to place on “ the School

Board the burden of justifying its conduct by clear and

convincing evidence.” 413 U.S. at 209.

The school board, however, contends that even if the

burden shifted, the judgment should be affirmed. But a

proper examination of the record refutes its claim. This

brings us to the second basic error of law that flaws this

case: the fallacious premise that the evidence must reveal

purposeful discrimination in order for the complainants

to prevail. This is contrary to Wright v. Council of the

City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972). Wright teaches

that in deciding whether a school board has acted law

fully, a court must focus “ upon the effect—not the purpose

or motivation—-of a school board’s action.” 407 U.S. at

462. Rather than ascribe good or evil motives to the board,

it is sufficient to look to the effect of its conduct on the

professional staff.

The record disclosed that despite the admonition of the

State Board of Education to recruit qualified black per

sonnel extensively, the school board has curtailed recruit

ment. In 1967-1968 there were 14 recruiting visits by blacks

to various colleges. In 1968-1969 there were none, but dur

ing the same term there were 76 recruiting visits by whites.

Recruiting by blacks picked up temporarily after the State

Board of Education criticized the county board, but in

1973-1974 the number of visits dropped to two. The lack

of the board’s recruitment efforts has a significant effect

—the board hires four white teachers for every black. This

disparity cannot be attributed to unequal qualifications.

From 1967 to 1973 the board hired 47 white teachers and

only 4 black teachers with no degree and low state certifi

cation. In 1971 the supervisor of personnel services di

rected his assistant to select for interviews from among

the black applicants only those with a superior or above

average rating. No similar limitation for white applicants

was disclosed. It is quite clear, therefore, that the disparity

in the board’s hiring of blacks and whites cannot be at-

13a

tributed to rational quality control. Moreover, the absence

of fair and clear procedures for promotion that apply

equally to all candidates has resulted,. during the years

following integration of the pupils, in doubling the num

ber of white principals while the number of black prin

cipals remained static.

The school board also places emphasis on the demo

graphic changes in Charles County, intimating that an

increase in the number of white pupils justifies the pro