Singleton v Jackson Municipal School District Memorandum of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

14 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Singleton v Jackson Municipal School District Memorandum of Appellants, 1969. f676f984-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a5245783-6ff2-48a4-9d10-fc2c3557db41/singleton-v-jackson-municipal-school-district-memorandum-of-appellants. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

V

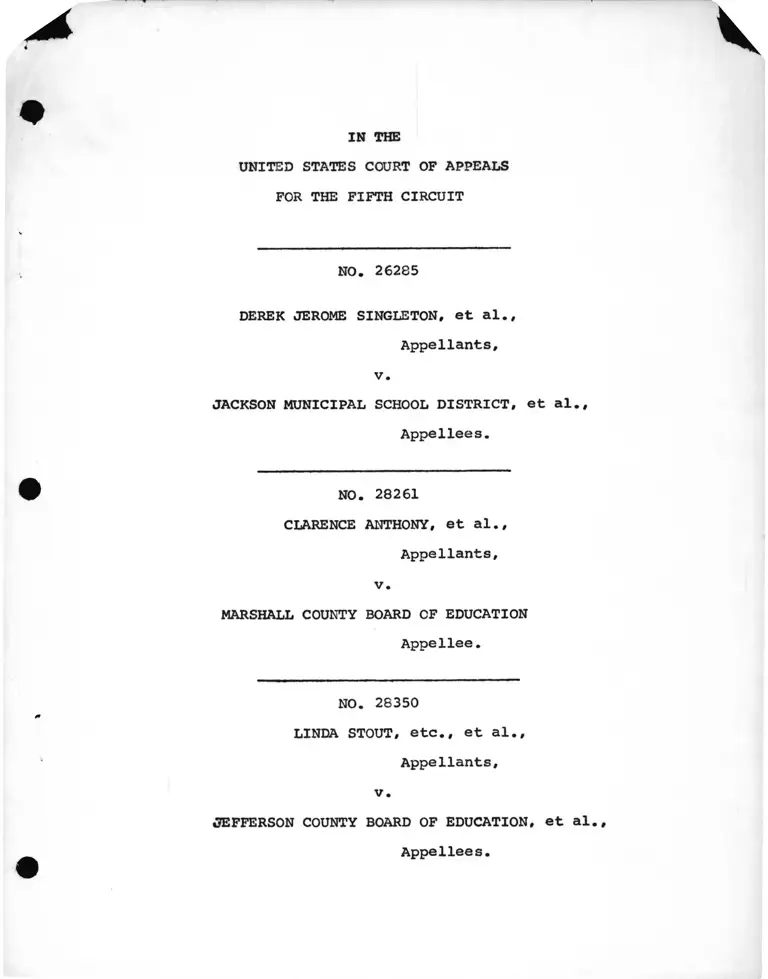

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 26285

DEREK JEROME SINGLETON, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

JACKSON MUNICIPAL SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Appellees.

NO. 28261

CLARENCE ANTHONY, et al..

Appellants,

v.

MARSHALL COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION

Appellee.

NO. 28350

LINDA STOUT, etc., et al..

Appellants,

v.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al..

Appellees

DORIS ELAINE BROWN, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY

OF BESSEMER, et al.,

Appellees.

NO. 28349

BIRDIE MAE DAVIS, et al..

Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF SCHOOL COMMISSIONERS OF

MOBILE COUNTY, et al..

Appellees.

NO. 28409

NEELY BENNETT, et al..

Appellants,

v.

R. E. EVANS, et al.,

Appellees.

ALLENE PATRICIA ANN BENNETT, etc., et al.

Appellants,

v.

BURKE COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al..

Appellees.

NO. 28407

SHIRLEY BIVINS, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

BIBB COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION

AND ORPHANGE FOR BIBB COUNTY, et al..

Appellees.

NO. 28408

OSCAR C. THOMIE, JR., et al.,

Appellants,

v.

HOUSTON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION

Appellee.

NO. 27863

JEAN CAROLYN YOUNGBLOOD, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

THE BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION

OF BAY COUNTY, FLORIDA, et al..

Appellees.

NO. 27983

LAVON WRIGHT, et al..

Appellants,

v.

THE BOARD OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION OF

ALACHUA COUNTY, FLORIDA, et al.,

Appellees

MEMORANDUM OF APPELLANTS

In accordance with the Court's direction# appellants in these

nine cases submit this memorandum concerning the validity,

significance and applicability, etc. to the cases before the Court

of Section 407 (a)(2) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§2000c-6.

That section provides that:

. . . nothing herein shall empower any

officer or court of the United States to

issue any order seeking to achieve a

racial balance in any school by requiring

the transportation of pupils or students

from one school to another or one school

district to another in order to achieve

such racial compliance with constitutional

standards.

yThe language and the legislative history of the section were

reviewed in United States v. Jefferson County Bd„ of Educ., 372

F.2d 836, 880 (1966), aff'd en banc, 380 F.2d 335 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied sub nom. Caddo parish School Bd,. v. united States, 389 U.S.

840 (1967) where this Court held that Section 407(a)(2) did not

restrict the remedial powers either of HEW or of the federal courts

in school desegregation suits brought to redress the deprivation of

The Memorandum of the United States in these cases supports

the interpretation of the legislative history set out herein.y

2/constitutional rights.

Numerous other federal courts have since passed upon this

section and all have concluded that the Act does not bar a federal

court from requiring busing as a means of achieving integration if

such is necessary to meet the affirmative obligations of school

boards to erect unitary non-racial school systems. United States

v. School District No. 151 of Cook County, 286 F. Supp. 786 (N.D.

111.), aff'd 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968); Moore v. Tangipahoa

Parish School Bd., Civil No. 15556 (E.D. La., July 2, 1969); Keyes

v. School District No. 1, Denver, Civil No. C-1499 (D. Colo.,

Aug. 14, 1969), stay pending appeal granted, ___ F.2d ___ (10th

Cir. No. 432-69, Aug. 27, 1969), stay vacated, ___S.Ct. ____

(Mr. Justice Brennan, Acting Circuit Justice, Aug. 29, 1969); Dowell

v. School Bd. of Okla. City, Civil No. 9452 (W.D. Okla. Aug. 8, 1969

vacated, ___ F.2d ___ (10th Cir. No. 435-69, Aug. 27, 1969),

reinstated, ___ S.Ct. _____ (Mr. Justice Brennan, Acting Circuit

Justice, Aug. 29, 1969); cf. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ., ___ F. Supp. ___, Civ. No. 1974 (W.D. N.C., April 23, 1969).

2/ The Jefferson dissenters were concerned with what appeared

to them to be the declaration of different constitutional

rules for north and south. As we read the decisions, the

applicable constitutional principles are the same wherever

a school district has had a hand in creating a segregated

public school system, north or south. United States v.

School District 151 of Cook County, 286 F. Supp. 786 (N.D.

HI.) aff'd 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968). And, as Judge

Heebe has put it, "most situations of so-called 'de facto

segregation' are, in reality, the result of intentional

discrimination by state officials." Moses v. Washington

Parish School Bd., 276 F. Supp. 834, 847 (E.D. La., 1967).

- 2 -

The issue, as it has been framed by school boards at various

3/txmes, xs whether that section of the Act bars a federal court,

in an action to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment, from requiring

transportation of black or white students to or from any school

facility as part of an effective desegregation plan.

There are several reasons not to construe the law to embrace

such a broad bar. In the first place, it is a truism of statutory

interpretation that statutes should be construed, whenever possible,

so as to sustain their constitutionality. If Section 407 were

construed as a limitation upon the power of the federal curts to

fashion a remedy for the deprivation of Fourteenth Amendment rights,

serious constitutional questions concerning the validity of the

legislation would be presented. Generally speaking, the power of

a court of equity to fashion remedies is commensurate with the

scope of the wrong. And where racial discrimination constitutes

the wrong, federal courts have "not merely the power but the duty

to render a decree which will so far as possible eliminate the

discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like discriminatior

in the future." Louisiana v. united States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965)

Cf. United States v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 395 U.S. 225

(1969); Gray v. Main, ___ F. Supp. ____, No. 2430-N (M.D. Ala.,

3/ The language in question is found in that part of the

statute which authorizes the Attorney General of the United

States, upon complaint, to sue individual school districts

which operate segregated public school systems. However, we

assume arguendo, as suggested by this Court in Jefferson,

that application of Section 407(a)(2) is not limited to suits

brought by the Attorney General.

I

March 29, 1968); Hogue v. Aubartin, 291 F. Supp. 1003 (S. D. Ala.

1968) ; Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1966); Plaquemines

Parish School Bd. v. United States, No. 24009 (5th Cir., August 15,

1969) (slip opinion at pp. 29-31).

But the Court need not decide the constitutional question.

There is little reason to believe that Congress intended such a

drastic limitation upon the remedial powers of the federal courts.

We think it is clear from the repeated references by several

senators and representatives to Bell v. School City of Gary, Ind«,

213 F. Supp. 819 (N. D. Ind.), aff'd 324 F.2d 209 (7th Cir. 1963),

cert, denied 377 U.S. 924 (1964), that the provision was added to

the legislation to negate any possible construction of the statute

supporting a new statutory cause of action to redress innocently

arrived at, de facto racial imbalance in the schools. The law

of the Bell case was that where a court found no State involvement

in creating the pattern of segregated schools, there was no right

to a decree requiring that the pattern be altered by the school

board. Senator Humphrey, floor manager of the bill in the Senate

(where the most important changes in and additions to the bill

were made; see, <e.c[., pent v. St. Louis-S.F. Ry. Co., 406 F.2d 399

(5th Cir. 1968)), said that. Section 407(a)(2) was added to write

"the thrust of the court's opinion [in the Gary case] into the

proposed substitute." 110 Cong. Rec. 12714-15 (1964).

When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was drafted, the distinction

between de facto and de jure segregation had already been drawn.

- 4

and the use of the phrase "racial imbalance" to refer to the former

(as contrasted with "segregation1) had already become common. Thus,

the language of the section, that "nothing herein" (emphasis supplied

shall empower the courts to deal with "racial imbalance" cases

(saying nothing of existing judicial power derived from the

Constitution or other statutes), also supports the view that it was

intended only as a safeguard against interpretations of the statute

which would expand the jurisdiction of the federal courts. The Act

was not to be construed as making any change in the basic

prerequisites which had to be met in order to invoke the jurisdic

tion of the federal courts in school desegregation cases. The Act

was not intended to imply that plaintiffs in such actions need no

longer prove complicity by the school board or the State in creating

a segregated condition in the public schools.

It would be wrong to impute to Congress any intention to

intervene in the declaration of constitutional doctrine — the

function of the judiciary. The language added to the Act was

designed to make clear that by enacting the law, Congress was not

attempting to change established constitutional principles.

Any other construction of the statute would seriously hamper

effectuation of the constitutional rights of hundreds of thousands

of Negro schoolchildren. For example, the requirement that a

school district's bus transportation system be reorganized on a

nonracial basis, when combined with even as modest a desegregation

plan as freedom of choice, amounts to a directive to transport

5

students to schools in order to dismantle a dual system of education

created and maintained by state action. It was for this reason

that Jefferson construed Section 407(a)(2) as inapplicable to limit

the remedial powers of the federal courts in dealing with school

districts in which there was de jure segregation.

Moreover, "busing" is a rather familiar feature on the

educational scene, in 1967-68, some 17,271,718 public school

students in the United States were given transportation at school

district expense, in the States represented by the cases before

this Court the figures were as follows:

Number of Enrolled Pupils Trans-

State ported at Public Expense, 1967-68

Alabama 397,754 ~

Florida 368,968

Georgia 517,517

Louisiana 508,007

Mississippi 313,466

Texas 491,85514/

It is also well known that virtually all private schools and

kindergartens in the country transport their students by bus. Thus

a decree requiring the use of school buses as a means of achieving

a unitary system injects nothing of startling significance into

school desegregation cases. As the court stated in Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg 3d. of Educ., supra, slip opinion at p. 16,

4/ Statistics on School Transportation (National Commission

on Safety Education of the National Education Association,

1963).

'397,754

368,968

517,517

508,007

313,466

491,855 "4

6

The Board has the power to use school

busses for all legitimate school

purposes. Busses for many years were

used to operate segregated schools.

There is no reason except emotion (and

I confess to having felt my own share

of emotion on this subject in all the

years before I studied the facts) why

school busses cannot be used by the

Board to provide the flexibility and

economy necessary to desegregate the

schools. Busses are cheaper than new

buildings; using them might even keep

property taxes down.

The busing issue is at least indirectly involved in all of

the cases before the Court. In every case there is at least the

possibility that an effective desegregation plan which meets the

standards previously declared by this court, i,e., elimination of

all-Negro schools and eradication of racial identifiability, may

require busing of students from one school to another. Every

district has in the past bused students to schools outside their

residence neighborhoods to maintain segregation. These districts

should be required to use buses to achieve integration. But the

Department of Health, Education and welfare, which has served this

Court much as a special master in school desegregation cases, ê .£.

Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, ____ F.2d ___ (5th Cir

1969), has declined to recommend plans which call for busing, even

where it is required to achieve a unitary school system, because

5/of purported doubts as to its legality. It is therefore

5/ Consider the following statements by HEW in its July 10,

1969 report to the district court on the Mobile school system

(p. 100) :

Our recommendations undoubtedly raise the question

whether, under the circumstances here, assignments

legally are required to be in a desegregation plan

if they require substantial additional transporta

tion. This, we believe, is a legal question which

we can only leave to the parties and to the court.

appropriate that the Court, sitting en banc, should make clear the

obligation of the district courts to require busing, if needed, as

a means of effectuating a unitary school system. If transportation

is necessary in order to operate the schools constitutionally,

district courts should entertain neither constitutional nor

statutory objections to this procedure.

In all of these cases, the record establishes that each of the

school districts has in the past used busing to maintain segregationr

In some, such as Singleton, Youngblood and Davis, the record shows

that an effective plan to establish a unitary school system will

require busing to achieve integration. In every instance the school

boards object, on the grounds of Section 407, to a decree requiring

the use of busing as a means of desegregation. But in most district

transportation will be required to achieve one element 6f a

quality1 education:--integration. , Transportation, like any other

aspect of quality education: books, schools, teachers, etc., is

thus the responsibility of the school districts.

In some instances, school districts seek to transport only

Negro students, leaving all-black schools and placing the burden

of desegregation once again on Negro schoolchildren.

We commend to the court's attention the following language

from Brice v. Landis, Civil No. 51805 (N.D. Cal., Aug. 8, 1969)

slip opinion at pp. 6-7.

8 -

It is true that the bussing of Negro children

to achieve integration, when the circumstances

so require, is not in itself discrimination.

As a practical matter some transfer by bussing

of Negro children will obviously be involved in

most integration plans. There may be practical

situations in which minority groups could not

reasonably complain that an equal or fairly

comparable number of white children were not

also being transferred by bussing, e.g., when

the predominantly Negro school is dilapidated

or a fire hazard or otherwise physically

unsuitable as to require closing.

Where* however, the closing of an apparently

suitable Negro school and transfer of its

pupils back and forth to white schools without

similar arrangements for white pupils, is not

absolutely or reasonably necessary under the

particular circumstances, consideration must be

given to the fairly obvious fact that such a

plan places the burden of desegregation entirely

upon one racial group.

The Minority children are placed in the position

of what may be described as second-class pupils.

White pupils, realizing that they are permitted

to attend their own neighborhood schools as usual,

may come to regard themselves as "natives" and to

resent the Negro children bussed into the white

schools every school day as intruding "foreigners."

It is in this respect that such a plan, when not

reasonably required under the circumstances,

becomes substantially discriminating in itself.

This undesirable result will not be nearly so

likely if the white children themselves realize

that some of their number are also required to

play the same role at Negro neighborhood schools.

See also. Felder v. Harnett County Bd. of Educ., 409 F.2d 1070,

1075 (4th Cir. 1969): " . . . That plan. . . was patently not in

compliance with the court's order. . . . There was no explanation

offered as to how the School Board determined upon particular

schools for extinction, nor did the closing plan disclose criteria

for assignment of the students of the closed schools except for a

cryptic reference to bus routes."

- 9 -

We urge the court also to make clear to district courts in

this circuit that non-racial reasons must support the closing of

all-Negro schools in preference to their utilization by white

students, or the proposal of one-way busing only.

Respectfully submitted.

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN C. AMAKER

WILLIAM ROBINSON

MICHAEL DAVIDSON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

DREW DAYS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

MELVYN LEVENTHAL

REUBEN V. ANDERSON

FRED L. BANKS

538% N. Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

LOUIS R. LUCAS

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee

JOHN L. MAXEY, II

STANLEY L. TAYLOR, JR.

North Mississippi Rural Legal

Services program

Holly Springs, Mississippi

0. W. ADAMS, JR.

U. W. CLEMON

1630 Fourth Avenue, N.

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

DAVID HOOD

2111 Fifth Avenue, N.

Bessemer, Alabama 35020

VERNON Z. CRAWFORD

FRANKIE L. FIELDS

1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

JOHN H. RUFFIN, JR.

930 Gwinnett Street

Augusta, Georgia 30903

THOMAS M. JACKSON

655 New Street

Macon, Georgia 31201

10

V

THEODORE R. BOWERS

1018 North Cove Boulevard

Panama City, Florida 32401

EARL M. JOHNSON

REESE MARSHALL625 West Union Street Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Attorneys for Appellants

11