Bernard v. City of Dallas Water Department Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bernard v. City of Dallas Water Department Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1994. 7c08ecb5-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a5643f85-509c-4f84-8f29-387523425660/bernard-v-city-of-dallas-water-department-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

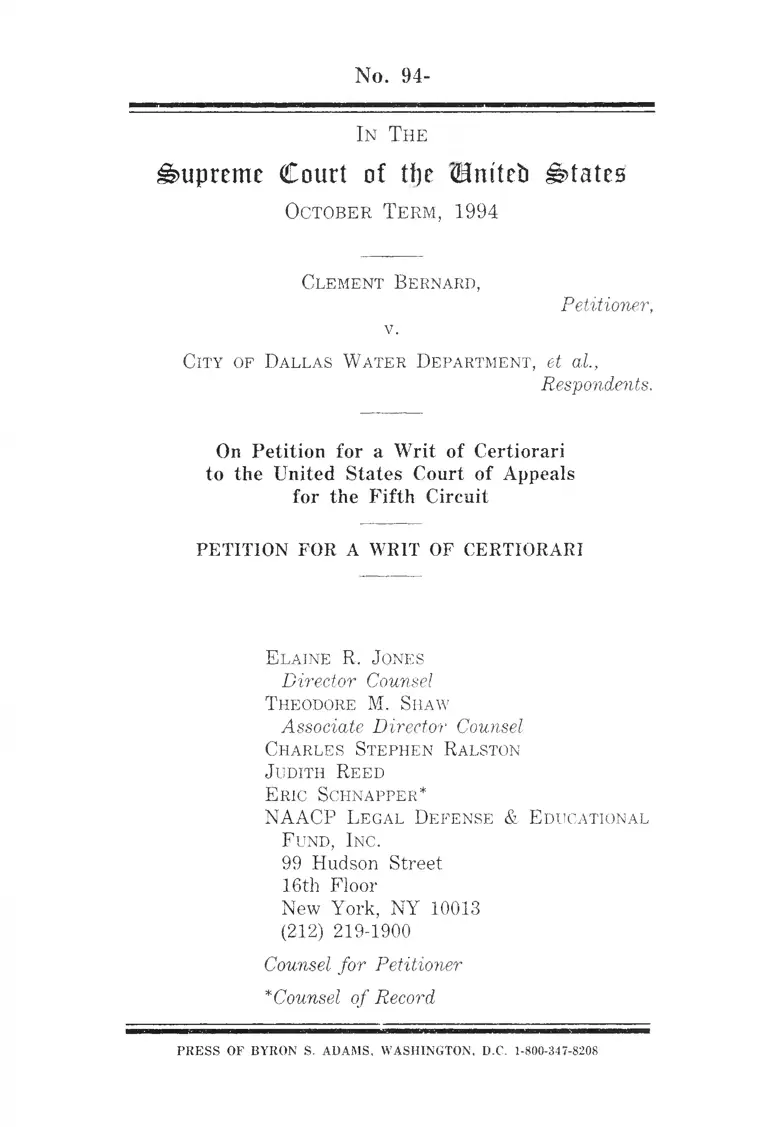

No. 94-

In The

Supreme Court of tfje (Hrn'tct) States

October Term, 1994

Clem en t Bernard ,

Petitioner,

v.

C ity of Dallas W ater D epartm ent , et al.,

Respondents.

On Petition for a W rit of Certiorari

to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

E laine R. J ones

Director Counsel

T heodore M. Shaw

Associate Director Counsel

Charles Steph en Ralston

J udith R e ed

E ric Sc h n a ppe r*

NAACP L egal De fen se & E ducational

F und , In c .

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel fo r Petitioner

*Counsel o f Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. 1-800-347-8208

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

(1) Did the Court of Appeals err in holding,

contrary to decisions of this Court and of the Fourth and

Sixth Circuits, that an employer which knows of a pattern of

racial harassment need not act to prevent the harassment of

any particular victim until that victim has filed a complaint?

(2) Did the Court of Appeals err in holding,

contrary to decisions in other circuits, that a claim of a

discrimination in promotions cannot be grounded on proof

of intentional racial discrimination in the training necessary

to qualify for the promotion at issue?

u

PARTIES

The parties who participated below are the petitioner,

Clement Bernard, and the respondents, the City of Dallas

and the City of Dallas Water Department.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ........................................... i

PARTIES ............................................................................. ii

OPINIONS BELOW .......................................................... 2

JURISDICTION ................................................................. 2

STATUTE INVOLVED ................................................... 2

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W R I T ................. 7

I. T H E D E C I S I O N B E L O W

CONFLICTS WITH DECISIONS OF

THIS COURT AND OF THE

FOURTH AND SIXTH CIRCUITS

REGARDING THE OBLIGATION

OF AN EMPLOYER TO STOP

KNOWN INVIDIOUS

H A RA SSM EN T......................................... 7

II T H E D E C I S I O N B E L O W

CONFLICTS WITH DECISIONS OF

OTHER CIRCUITS THAT A

PROMOTION CLAIM CAN BE

B A S E D O N T H E

DISCRIMINATORY DENIAL OF

THE TRAINING REQUIRED FOR

PROMOTION........................................... 13

CONCLUSION 15

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Long v. Ford Motor Company,

496 F.2d 500 (6th Cir. 1974) ............................. 15

Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson,

477 U.S. 57 (1986)........................................... 7, 8, 9

Paroline v Unisys Corp.,

879 F.2d 100 (4th Cir. 1989) modified on other

grounds 900 F.2d 27 (4th Cir. 1990) . . . . . . 10, 11

Rowlett v. Anheuser-Busch, Inc.,

832 F.2d 194 (1st Cir. 1 9 8 7 ).............. ........... 14, 15

Wright v National Archives & Records Service,

609 F.2d 702 (4th Cir. 1979) .............. .. 14

Yates v. Avco Corp.,

819 F.2d 630 (6th Cir. 1987) ............................. 10

Statutes: Pages:

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) .............................................. ........... .. 2

42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq................ passim

In The

Supreme Court of tfje Um teb S ta te s

October Term, 1994

CLEMENT BERNARD,

Petitioner,

V.

CITY OF DALLAS WATER DEPARTMENT, et al.,

Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to

the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Clement Bernard respectfully prays that a writ of

certiorari issue to review the judgment and opinion of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered

in this proceeding on April 7, 1994.

2

OPTNTONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States District Court for

the Northern District of Texas, which is not officially

reported, is set out at pp. la-20a of the Appendix. The

opinion of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which is not

published, is set out at pp. 22a-25a of the Appendix.

JURISDICTION

The decision of the Fifth Circuit was entered on

April 7, 1994. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28

U.S.C. §1254(1).

STATUTE INVOLVED

Section 2000e-2(a) of 42 U.S.C. states in pertinent

part:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice

for an employer -

(1) to ... discriminate against any individual

with respect to his ... terms, conditions, or

privileges of employment, because of such

individual’s race ....

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an action under Title VII of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq., seeking redress for

3

discrimination in the terms and conditions of petitioner’s

employment. Petitioner is an employee at a water treatment

plant operated by the respondent City of Dallas Water

Department. The complaint alleged, inter alia, that

petitioner had been the victim of racial harassment and had

been denied promotions because of his race. The complaint

was filed on July 31, 1990, in the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Texas.

On June 23, 1993, the district court granted

respondents’ motion for summary judgment, dismissing all of

petitioner’s claims with prejudice. (la-21a). On April 7,

1994, the Fifth Circuit affirmed that dismissal. (22a-25a).

Certain facts with regard to petitioner’s harassment

claim are not in dispute. For several years an employee at

the Water Department, one Harry B. Ketter, had engaged

in systematic harassment of minorities and women in the

unit where petitioner worked. Ketter was a higher ranking

employee who was often assigned to work as petitioner’s

supervisor.1 The harassment had begun well before

petitioner was hired into that unit,2 and prior to petitioner’s

arrival Ketter had directed that abuse to other employees.

As the district court noted, Ketter generated and distributed

1 District Court Record (hereinafter "D. Ct. Rec.") 162

(affidavit of Linda Kelsey).

2 D. Ct. Rec. 159-60 ("I can verify that the racial . . .

harassment was going on long before Mr. Bernard went to work for

DWU . . . Marvin Williams is a black male at [the unit involved],

[He] has been there for years before Mr. Bernard. [He] also was

subjected to this type of racial harassment . . ..") (affidavit of Linda

Kelsey); D. Ct. Rec. 164 (graffiti all over the walls "even before

Clement Bernard started working") (affidavit of Danny Holland); D.

Ct. Rec. 168 (racist material displayed from 1987 onwards) (affidavit

of Michael Gonzalez); D. Ct. Rec. 169 (racist displays obvious when

affiant hired in mid-1987) (affidavit of Mark DuPree).

4

racist paraphernalia (15a), and used racial epithets. (3a, 14a)

Id. Ketter prominently displayed a statue depicting black

female genitalia, an object he had carved on government

time.3 Ketter repeatedly accosted black workers with

accusations that blacks were intellectually inferior and that

"the white race, like the Germans, are superior."4 Ketter

openly used the plant walls and bulletin boards to display his

racist propaganda,5 and created a display of racist

paraphernalia that for months was "in full view" of anyone

in the unit.6 A number of black and female workers had

resigned when it became apparent that respondent was

taking no steps to end the harassment.7 The district court

concluded that Ketter’s "many transgressions" were "indeed

unconscionable" and "indefensible". (16a-18a). The Court of

Appeals held that petitioner had adduced "sufficient

evidence of a racially hostile working environment,"

including Ketter’s "racially insulting conduct and display ...

[of] materials derogatory of blacks in the workplace." (24a).

In response to the motion for summary judgment,

petitioner also submitted several undisputed affidavits

demonstrating that the plant managers were understandably

aware of Ketter’s harassing activities before petitioner was

victimized. A prior black worker had been harassed by

Ketter "with management’s knowledge."8 Victims of

harassment were instructed on several occasions that they

3 D. Ct. Rec. 161 (affidavit of Linda Kelsey).

4 D. Ct. Rec. 166 (affidavit of Danny Holland).

5 Id.-, D. Ct. Rec. 168 (affidavit of Michael Gonzalez).

6 D. Ct. Rec. (affidavit of Mark DuPree).

7 D. Ct. Rec. 163 (affidavit of Linda Kelsey).

8 D. Ct. Rec. 160 (affidavit of Linda Kelsey).

5

would have to "ignore" the abusive remarks.9 The offensive

statue was displayed where management officials regularly

saw it, and had been created by Ketter out of city materials

"with the knowledge of management."10 Ketter’s more

elaborate display of racist paraphernalia was in a room

regularly visited by managers and supervisors.11 The Court

of Appeals correctly observed that although ”[t]his activity

apparently went on for some time, ... management did not

take action to stop it until ... October, 1988". (24a).

The Court of Appeals nonetheless concluded that on

this record summary judgment should be granted to the

respondent employer. The Fifth Circuit held that under

Title VII the employer’s only obligation to petitioner was to

take action if and when petitioner complained about Ketter.

Petitioner filed such a complaint in October, 1988, objecting

that he, like other employees at the plant, had been

repeatedly harassed by Ketter. After Ketter had "persisted

in his disruptive and antagonistic behavior" (15a) for three

additional months, respondent finally reassigned him to an

area of the plant where he would have less contact with

petitioner. The Fifth Circuit reasoned that respondents’

knowing inaction prior to October 1988 was legally

irrelevant, and that the legal inquiry was limited to whether

the city had responded adequately once Bernard formally

complained. Finding the city’s actions after October 1988

sufficient, the court of appeals concluded that summary

judgment in favor of respondent was required on the racial

harassment claim.

Petitioner’s promotion claim concerned his

unsuccessful efforts to promote to the position of T-9

10 D. Ct. Rec. 161 (affidavit of Linda Kelsey).

11 D. Ct. Rec. 170 (affidavit of Mark DuPree).

6

Instrument Technician. Petitioner had been hired as a T-7

Apprentice Instrument Technician (la). Petitioner alleged

that because of his race he was denied the training needed

to promote to Instrument Technician.12 As a journeyman

Instrument Technician, Harry Ketter was responsible for

providing that training. In addition to the evidence of racial

harassment by Ketter described supra, petitioner adduced

direct evidence of a discriminatory motive behind the denial

of training. In response to the summary judgment motion,

petitioner submitted an affidavit describing remarks by

Ketter and by petitioner’s regular supervisor, Don Pierce:

It was ... Harry Ketter[’]s place to train T-7’s

for promotions. [He] made the comment on

several occasions as long as he was there no

black man Mr. Bernard or [another black

worker] would become [a] T-9 or higher.

Don Pierce the T-10 had the same opinion.

He also said that on several occasions.13

Having been denied the necessary training, petitioner was

unable to pass the civil service examination for promotion to

Instrument Technician. After repeatedly failing in his

attempts to promote to the position of Instrument

12 2a, 10a. The complaint alleged, inter alia:

"Plaintiff ... was required ... to be

trained by one of Defendant’s em

ployees, Harry Ketter. Defendant’s

agent Ketter flatly refused to train

Plaintiff because of Plaintiffs race,

black, and Plaintiff reported this to

... [the] Assistant Manager of the

Plant"

Par. 5.

13 D. Ct. Rec. 162 (affidavit of Linda Kelsey).

7

Technician, petitioner ultimately found another worker who

would train him to work as a Mechanic Technician, and he

succeeded in promoting into that position. (13a).

Both courts below held that any such discrimination

in training was legally irrelevant. They reasoned that the

proper inquiry under Title VII was limited to whether there

was discrimination in the promotion decisions themselves.

Ketter’s racial animus was irrelevant, they insisted, because

Ketter himself did not make the actual promotion

decisions.14 The court of appeals concluded that summary

judgement was mandated by the fact that petitioner "did not

pass the required test for promotion." (23a).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I. THE DECISION BELOW CONFLICTS

WITH DECISIONS OF THIS COURT AND

OF TH E FO U R TH AND SIXTH

CIRCUITS REGARDING THE OBLIGA

TION OF AN EMPLOYER TO STOP

KNOWN INVIDIOUS HARASSMENT

The decision below reopens a loophole in the

nation’s anti-discrimination laws which this Court intended

to close eight years ago. In Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson,

A ll U.S. 57 (1986), this Court unanimously rejected the

argument that an employer had no obligation to stop the

sexual (or racial) harassment of an employee until and

unless that employee lodged a complaint objecting to such

discrimination.

14 2a ("At no time during plaintiffs employment ... did Harry

Ketter have the power to ... promote ... the plaintiffjf]."), 23a ("Harry

Ketter ... could not directly influence this decision").

8

[W]e reject [the employer’s] view that the

mere existence of a grievance procedure ...

coupled with [the employee’s] failure to

invoke that procedure, must insulate [the

employer] from liability.

477 U.S. at 72. In Meritor the employer expressly conceded

that it would have been liable if it "knew [or] reasonably

could have known of the alleged misconduct." 477 U.S. at 70.

This Court observed that an employer would of course be in

violation of Title VII if the acts of harassment were "so

pervasive and so long continuing ... that the employer must

have become conscious of [them]." 477 U.S. at 72.

The Fifth Circuit decision in the instant case

endorses an interpretation of Title VII expressly rejected by

this Court and disavowed by the employer in Meritor. Under

the decision below, even actual knowledge by the employer

that racial harassment is occurring imposes no obligation on

the employer to act unless, and until, each particular victim

complains. On the Fifth Circuit’s view, an employer has no

general duty to end known racial harassment, or to protect

employees whom it has reason to know will be or are being

harassed. Only when and if one of those known victims

chooses to complain does Title VII impose any

responsibility, the circuit court concluded, and that

responsibility is limited to assisting to that particular victim.

A failure to respond to such a complaint does not expose

the employer to lability to any other victim of the known

harassment.

In this case the court of appeals acknowledged there

was sufficient, largely undisputed evidence to establish that

the harassment had created "a racially hostile working

environment." (24a-25a). The Fifth Circuit also

acknowledged that racial harassment at the facility was a

9

longstanding problem, which the employer did nothing about

until October, 1988:

The activity apparently went on for some

time, but management did not take action to

stop it until Bernard complained in October,

1988. At that time, management began

regularly to enforce its policy of preventing

displays of offensive material.

(24a) (Emphases added). The undisputed evidence made

clear that management had known about the harassment

long before October 1988. (See pp. 4-5, supra).

Under these circumstances, Mentor clearly dictated a

finding of employer liability. The Fifth Circuit reached

precisely the opposite result, holding that liability to Bernard

was to be determined, not based on the years of knowing in

action by respondents prior to October 1988, but solely by

how the city had responded after petitioner Bernard

complained:

[T]he circumstances demonstrate that the

managers ... took prompt action when

informed that Bernard found Ketter’s conduct

offensive ...

(25a) (Emphasis added). Although plant managers had

earlier failed to act on misconduct known to all, and thus

clearly signaled that the misconduct was acceptable, the Fifth

Circuit thought it sufficient to defeat this action that

"[management's handling of this situation after Bernard

complained never suggested that Ketter’s offensive conduct

was tolerated or excusable." (25a) (Emphasis added).

Although city officials had cavalierly instructed previous

harassment victims that they would have to try to ignore

Ketter’s harassment, that deliberate inaction, the Fifth

Circuit held, was irrelevant because management did not

10

"advise Bernard to ignore Ketter’s behavior." (25a)

(Emphasis added.)

The Fourth and Sixth Circuits have expressly rejected

the Fifth Circuit rule in this case, holding instead that once

an employer learns of ongoing harassment it must act to

protect all employees, not merely those, if any, who have

complained. In Yates v. Avco Corp., 819 F. 2d 630 (6th Cir.

1987), the company sought to avoid liability to the plaintiffs

at issue by insisting it "took remedial action once the

plaintiffs registered complaints." 819 F.2d at 636. The Sixth

Circuit rejected that argument, noting that the employer

"had notice" of the problem years earlier. 819 F.2d at 835).

Under "agency principles", the Sixth Circuit reasoned, the

employer was liable to the plaintiffs and any other

subsequent victims because their injuries were "foreseeable."

819 F.2d at 636.

[The employer’s] duty to remedy the problem,

or at a minimum, inquire, was created earlier

when the initial allegations of harassment

were reported.

Id.

Similarly, in Paroline v Unisys Corp., 879 F.2d 100

(4th Cir. 1989) modified on other grounds 900 F.2d 27 (4th

Cir. 1990), the Fourth Circuit reversed a district court

decision which had granted summary judgment "because

Unisys took prompt remedial action after Paroline’s

complaint." 879 F.2d at 102 (Emphasis added). The Fourth

Circuit rejected the employer’s argument that it was entitled

to summary judgement if it merely proved that it "took

prompt and adequate remedial steps once Paroline

complained." 879 F.2d at 106 (Emphasis added). The

Fourth Circuit noted that there had been prior complaints

by other employees about sexual harassment by the same

individual who ultimately victimized the plaintiff, and that

there was evidence suggesting that Unisys had earlier taken

11

only nominal measures in response to the known

harassment. 879 F.2d at 106-07. The Fourth Circuit held:

In a hostile environment case under Title VII,

we will impute liability to an employer who

anticipated or reasonably should have

anticipated that the plaintiff would become a

victim of sexual harassment in the work-place

and yet failed to take action reasonably

calculated to prevent such harassment. An

employer’s knowledge that a male worker has

previously harassed female employees other

than the plaintiff will often prove highly

relevant in deciding whether the employer

should have anticipated that the plaintiff too

would become a victim of the male

employee’s harassing conduct.

879 F.2d at 107 (Emphasis in original). The Fifth Circuit’s

decision in the instant case applies precisely the opposite

rule.15

The Fifth Circuit decision in this case has the effect

of virtually suspending in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi

the Title VII prohibition against sexual and racial

harassment. Employers in those states no longer need

prevent foreseeable acts of harassment or deal with known

harassers. Faced with a substantiated complaint of racial or

sexual harassment, employers in the Fifth Circuit are under

no legal obligation to end the misconduct or discipline the

wrongdoer, but are required only to protect the specific

complainant. An employer may now meet its statutory

obligations in the Fifth Circuit merely by separating the

15 The reasoning of the courts below that the respondents’

conduct did not violate Title VII is not affected by the changes in

Title VII remedies under the 1991 Civil Rights Act.

12

complainant and the wrongdoer, even though the harasser

remains free to redirect his abuse at other employees.

That is precisely what occurred in the instant case.

Both courts below concluded that respondents had met their

obligations under Title VII simply by relocating Ketter, an

employee whose record of racial and sexual harassment was

well known, to another part of the plant;

[After] Ketter proved unwilling to conform

his behavior to the standards of the workplace

... he [was] transferred out of plaintiffs work

area. While Ketter’s behavior in the

workplace is indefensible, there is nothing

inherently unlawful or inequitable about the

treatment accorded Ketter by his

supervisors....

(17a).16 On this view, Title VII imposes on employers, not

an obligation to prevent sexual or racial harassment, but

only a duty to periodically provide the harasser with a fresh

set of victims. Under the decision of the courts below,

respondents could tomorrow knowingly and deliberately

designate as petitioner’s supervisor an avowed bigot with a

persistent history of racial harassment, so long as they chose

a racist other than Harry Ketter.

16See also 15a (employer concedes Ketter remained "uncontrite

and persisted in his disruptive and antagonistic behavior")

13

II THE DECISION BELOW CONFLICTS

WITH DECISIONS OF OTHER CIRCUITS

THAT A PROMOTION CLAIM CAN BE

BASED ON THE DISCRIMINATORY

DENIAL OF THE TRAINING REQUIRED

FOR PROMOTION.

The second question presented by the decision below

is whether the Title VII prohibition against discrimination in

promotions can be evaded by the simple expedient of

denying black workers the training needed to qualify for

promotion.

The circumstances of this case present a classic case

of such a scheme to circumvent Title VII. Petitioner offered

uncontradicted evidence that Ketter was responsible for

providing to T-7 Apprentice Instrument Technicians the

training required to promote to T-9 Instrument Technician.

(See p. 6, supra). Both courts below recognized that Ketter

had a long history of racial harassment of black workers.

Petitioner also adduced direct evidence of statements by

Ketter, and by petitioner’s regular supervisor, that they were

determined to prevent any black worker from promoting into

a T-9 position. Petitioner’s allegation that he was in fact

denied needed training was also uncontradicted.

Both courts below dismissed this evidence as legally

irrelevant. Candidly recognizing Ketter’s racial animus, the

lower courts regarded as irrelevant Ketter’s training

responsibilities, insisting his racism was unimportant so long

as Ketter himself did not make the actual promotion

decisions. (2a, 23a). The dispositive fact, the Fifth Circuit

insisted, was that Bernard "did not pass the required test for

promotion." (23a). To the Court of Appeals it was of no

legal significance that petitioner alleged he was unable to

pass that test precisely because Ketter refused to give him

the needed training.

14

The three other circuits to address this issue have all

held, contrary to the decision of the Fifth Circuit in this

case, that Title VII prohibits an adverse employment action

that is grounded on a discriminatory denial of training. In

Wright v National Archives & Records Service, 609 F.2d 702

(4th Cir. 1979) (en banc), the plaintiff claimed that he had

been unlawfully denied the training necessary for promotion

from a GS-5 position to a GS-9 position. Although the en

banc court was divided as to whether the plaintiff had

proven intentional racial discrimination in training, all

members of the Fourth Circuit agreed that such proof would

have entitled the plaintiff to relief for the ensuing promotion

denial.

In Rowlett v. Anheuser-Busch, Inc., 832 F.2d 194 (1st

Cir. 1987), the plaintiff alleged that he had been unfairly

denied pay raises because his job performance was adversely

affected by the discriminatory denial of job training accorded

to whites. 832 F.2d at 196-97. There, as alleged here, the

individual responsible for providing the relevant training

flatly refused to do so. The First Circuit upheld a finding of

liability based in part on that discrimination. 832 F.2d at

201-02:

The district court found that Anheuser-Busch

had discriminated against Rowlett on the

basis of race in the pay raises he received.

He established ... that he received smaller

raises than the white foremen received.

Anheuser-Busch explained this ... as resulting

from Rowlett’s evaluations. The district court

found this reason to be ... intricately related

to the denial of training. Rowlett had been

criticized for his lack of skills .... Yet the

court found that the lack of skills were

15

directly related to the discriminatorily denied

training .... We find this reasoning persuasive

832 F.2d at 202.

Finally, in Long v. Ford Motor Company, 496 F.2d 500

(6th Cir. 1974), the plaintiff, who had been dismissed for

allegedly inadequate job performance, claimed that any such

deficiencies were due to inadequate training by the

employer. 496 F.2d at 502. The Sixth Circuit held that the

plaintiff would be entitled to prevail if he could demonstrate

that the denial of training was the result of intentional

discrimination on the basis of race. 496 F2d at 505.

As a result of the decision below, the scope of the

protections afforded by Title VII now vary according to the

location of the employer. An employer in the Fifth Circuit

can legally discriminate in promotions -- and, presumably in

wages or discharges - by intentionally denying needed

training to minorities or women. In the First, Fourth and

Sixth Circuits, on the other hand, such a scheme of

intentional discrimination is a per se violation of federal law.

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, a writ of certiorari should be

granted to review the judgment and opinion of the Fifth

Circuit Court of Appeals.

Respectfully submitted,

ELAINE R. JONES

Director Counsel

THEODORE M. SHAW

Associate Director Counsel

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

JUDITH REED

ERIC SCHNAPPER*

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Petitioner

*Counsel of Record

No. 93-1651

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF YTEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION__________

CLEMENT BERNARD,

Plaintiff,

VS.

CITY OF DALLAS, CITY OF DALLAS WATER

DEPARTMENT

(Dallas Water Utilities),

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

Now before the Court is Defendant’s Motion For

Summary Judgment, filed on February 6, 1992. Plaintiffs

Response was filed on March 11, 1992.

I. UNDISPUTED FACTS

1. Plaintiff is a black male who began work on

March 12, 1986 as an Apprentice Water Instrument

Technician T-7 at the Southside Wastewater Treatment

Plant’s Instrument Section ("SSWWTP") for the Dallas

Water Utilities ("DWU”).

2a

2. On July 31, 1990, Plaintiff filed this lawsuit

against Defendants City of Dallas and DWU alleging racial

discrimination in training, racial harassment and retaliation

under 42 U.S.C., §2000(e).

3. Harry B. Ketter was also an employee of

DWU. He was a Water Instrumentation Technician T-9.

At no time during Plaintiffs employment with DWU did

Harry Ketter have the power to fire, promote or otherwise

directly affect the plaintiffs employment

4. Plaintiff alleged racial discrimination and/or

intimidation on January 23, 1989 in his first EEOC

complaint (#310-89-0858), two years after he began working

at SSWWTP. The EEOC determination on these charges

found that there was no evidence that Plaintiff was denied

proper training because of his race. The EEOC cause

determination also concluded that the City of Dallas took

remedial action once made aware of harassment by a fellow

employee, and that no additional relief was necessary.

5. In October, 1988, Plaintiff verbally complained

3a

to Ted Kilpatrick, Southside Wastewater Treatment Plant

(SSWWTP) Manager. The verbal complaint involved

ongoing disagreements Plaintiff had with fellow employee

Harry Ketter who had made derogatory statements

concerning Plaintiffs race (black). Plaintiff further alleged

Ketter had posted derogatory drawings and pictures on the

walls of the Instrument Section work area. Ted Kilpatrick

directed Don Perez, SSWWTP Assistant Manager, to

investigate the incidents, and to monitor the employees of

the Instrument Section for inappropriate activities.

Approximately one week later, Don Perez reported to

Kilpatrick that he had counseled with the parties, and each

party was committed to going forward and working

harmoniously. As plant manager, Kilpatrick also had a

policy of maintaining the work place free of inappropriate

literature. The investigation did find some pictures of a

sexual and religious connotation and Mr. Kilpatrick ordered

that they be removed immediately. On December 14, 1988,

Kilpatrick met with Plaintiff to determine the status of the

4a

grievance. According to the Plaintiff, the concerns expressed

in the complaints were resolved.

6. On or about December 22, 1988, Ted

Kilpatrick held a counseling session with Plaintiff, Ketter

and Don Pierce, who then was the supervisor of Plaintiff

and Ketter. Kilpatrick again discussed his policy of

maintaining the work place free of inappropriate literature

and the responsibility of each employee to work

cooperatively. Plaintiff and Ketter both pledged that they

would work cooperatively in the work place. Also, on

December 22, 1988, Ted Kilpatrick conducted a separate

counseling session with Don Pierce concerning his

responsibilities in overseeing the Instrumentation Group.

Ted Kilpatrick directed Don Pierce to monitor the

employees and document any misconduct.

7. On December 28,1988, Plaintiff again verbally

complained with Ted Kilpatrick. Plaintiff alleged that the

incidents of harassment by Harry Ketter were continuing. In

response Ted Kilpatrick directed another investigation. On

5a

or about January 9, 1989, Kilpatrick ordered that the

Instrument Section be reorganized and that the parties

having conflicts in the work place be assigned to different

areas of the plant, and not to work together. Kilpatrick also

ordered that Harry Ketter not be left in charge as acting

supervisor should the supervisor Don Pierce not be on duty.

Plaintiff did not appeal Kilpatrick’s actions to his complaint.

8. Inspections for inappropriate literature and

materials were continually conducted until September, 1989

by Kilpatrick, Don Perez/SSWWTP Assistant Manager, Jesse

Beard/SSWWTP Maintenance Supervisor and Kathryn

Hedges/Dallas Water Utilities Personnel Representative.

9. Plaintiff alleged retaliation in violation of Title

VII in his second EEOC complaint filed April 13, 1990.

Plaintiff asserted that the retaliation occurred when he was

denied a merit increase as a result of his yearly performance

evaluation. The performance evaluation was received from

Plaintiffs direct supervisor, Don Pierce, a white male. Don

Pierce notified Plaintiff the year earlier that his performance

6a

would have to improve to get the Top Step merit increase.

Don Pierce gave Plaintiff a satisfactory performance rating,

however, he had also recommended that Plaintiff needed to

perform at a higher rate in order to qualify for the top merit

increase. Don Pierce did not deny the increase, but

recommended another evaluation in six months.

As a standard procedure, all performance evaluations

and recommendations of merit increases are reviewed by the

section’s division manager, which in this case was Ted

Kilpatrick, also a white male. After discussing with Plaintiff

his concerns regarding his annual evaluation and merit

increase recommendation, Division Manager Kilpatrick met

with Plaintiffs immediate supervisor Don Pierce. In this

meeting with Kilpatrick, Pierce reviewed his evaluation

process and his recommendation that Plaintiff needed to be

performing at a higher level to qualify for his top merit

increase. Thereafter, as is standard practice for all

employees, Kilpatrick reviewed P lain tiff’s merit

recommendation and the information provided by Plaintiff

7a

and Pierce. Subsequently, Kilpatrick recommended that

Plaintiff receive his merit raise.

10. Dallas Water Utilities Management had a

policy of maintaining all work areas free of inappropriate

literature. On or about December 9, 1988, Mr. Ted

Kilpatrick/SSWWTP Plant Manager discovered several

playboy-type magazines in Ketter’s desk area. Kilpatrick

confiscated those magazines and verbally reprimanded

Ketter for having inappropriate material in the work place.

When questioned about the magazines, Ketter acknowledged

he had read the magazines, but denied ownership. Ketter

received a written reprimand for insubordination on March

22, 1989.

11. After counseling sessions proved unsuccessful,

Kilpatrick ordered the permanent transfer of Ketter from

the Instrumentation Section in September, 1990.

12. On or about May 11, 1990, the EEOC issued

a Right to Sue letter based on a second EEOC charge, No.

310890858, filed against the City of Dallas Water

8a

Department by Plaintiff.

13. Plaintiff filed suit based on the Right to Sue

Letter on July 31, 1990.

II. SUMMARY JUDGMENT REQUIREMENTS

Summary judgment is proper when the pleadings and

evidence on file show that no genuine issue exists as to any

material fact and that the moving party is entitled to

judgment or partial judgment as a matter of law. See Fed.

R. Civ. P. 56. As the Fifth Circuit stated in Christophersen

v. Allied-Signal Corp., 902 F.2d 362, 364 (5th Cir. 1990),

"[bjefore a court may grant summary judgment, the moving

party must demonstrate that it is entitled to judgment as a

matter of law because there is no actual dispute as to an

essential element of the plaintiffs case."

Where the nonmovant bears the burden of proof at

trial, the movant may discharge its burden by showing, that

is, by pointing out to the court, that there is an absence of

evidence to support the nonmovant’s case. Celotex Corp. v.

Catrett, A ll U.S. 317, 324 (1986). Where the nonmovant

9a

bears the burden of proof at trial, the movant is not required

to produce evidence to negate the opponent’s claims. Lujan

v. National Wildlife Fed’n, 497 U.S. 871, 110 S.Ct. 3177, 3187,

111 L.Ed.2d 695 (1990). For that reason, there is no burden

on the movant to support its motion with affidavits or other

similar materials where the nonmovant will bear the burden

of proof at trial. Celotex, 477 U.S. at 323. Rather, the

movant need only demonstrate that the evidence which does

exist does not "present a sufficient disagreement to require

submission to a jury...." Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., A ll

U.S. 242, 251-252, 106 S.Ct. 2505, 91 Led. 2d 202, 214

(1986).

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56(e) prescribes

what form the non-movant’s response must take in order to

defeat a properly pled and supported motion for summary

judgment or partial summary judgment:

When a motion for summary judgment is made and

supported as provided in this rule, an adverse party

may not rest upon the mere allegations or denials of

the adverse party’s pleading, but the adverse party’s

response, by affidavits or as otherwise provided in

this rule, must set forth specific facts showing that

10a

there is a genuine issue for trial. If the adverse part

does not so respond, summary judgment, if

appropriate, shall be entered against the adverse

party. Fed.R.Civ.p. 56(e).

III. PLAINTIFF’S CAUSES OF ACTION

Plaintiff alleges three basic causes of action in his

complaint against Defendant:

(1) . Plaintiff claims he was discriminated against

and discharged in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq. in

retaliation for his filing of the initial EEOC charge.

(2) . Plaintiff claims that he suffered racial

harassment in the workplace while employed by Defendant,

in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq.

(3) Plaintiff claims racial discrimination against

him by Defendant in job training and promotions in

violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq.

(3). Plaintiff seeks the following:

A. A declaratory judgment that the practices

11a

alleged in Plaintiffs Original Complaint are in violation of

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42

U.S.C. §2000e et seq.

B. An injunction prohibiting Defendant from

engaging in the aforesaid practices.

C. An injunction prohibiting Defendant from

engaging in racial discrimination.

D. An injunction prohibiting Defendant from

engaging in retaliation for the exercise of protected rights.

E. Damages in the form of wages and other

benefits he would have received but for Defendant’s

discrimination, including promotion to a position that he is

qualified to hold, and in a department where he will not

have to work with or be supervised by those individuals who

have discriminated against Plaintiff, and pre-judgment and

post-judgment interest.

F. An award to Plaintiff of costs and attorneys’

fees

12a

IV. DEFENDANTS MOTION FOR SUMMARY

JUDGMENT

A DISPARATE TREATMENT THEORY

ARGUMENTS

Defendant asserts that Plaintiff cannot recover under

a disparate treatment theory because Plaintiff cannot meet

the burden of proof for such cases established by the

Supreme Court in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411

U.S. 792 (1973). In McDonnell, Id., the Supreme Court

required that a plaintiff can recover against an employer

under a disparate treatment theory only by making a prima

facie showing that (1) he is a member of a protected group;

(2) he is qualified for the job to which he sought promotion;

(3) he was denied promotion; and, (4) after his denial of a

promotion, others who are not members of the protected

class were promoted into those positions.

If a prima facie case is made by a plaintiff, then

under McDonnell the employer must articulate a legitimate

nondiscriminatory reason for its action.

13a

If a legitimate nondiscriminatory reason is articulated

by the employer, then McDonnell requires the plaintiff to

show by a preponderance of the evidence that the

employer’s reason is merely pretextual.

Defendant argues that Plaintiff has not made a prima

facie case of disparate treatment. Defendant contends that

Plaintiff had every opportunity to train for and compete for

promotions within his department, that in fact he passed the

T-9 Mechanic Technician Test with the help of a white

supervisor, after failing the examination several times.

Plaintiff has not shown, Defendant argues, where similarly

situated white employees were provided training to qualify

for promotions, while black employees like himself were not.

B. H O S T I L E W O R K E N V I R O N M E N T

ARGUMENTS

Defendant argues that Plaintiff also cannot prevail

under a Title VII hostile work environment action because

to do so requires that Plaintiff must prove that the work

environment is "so heavily polluted with discrimination as to

14a

destroy completely the emotional and psychological stability

of minority group workers...." Rogers v. Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, 454 F.2d 234 (5th Cir. 1971).

First, Defendant contends that the primary

contributor to work pollution in Plaintiffs work

environment, Harry Ketter, was in no position to affect

adversely Plaintiff because Ketter was not Plaintiffs

supervisor.

Second, Defendant argues that Plaintiff and Ketter

voluntarily engaged in acrimonious conversations with each

other about various racial, religious, and sexual issues.

Third, Ketter’s use of racial epithets alone do not rise

to the level of work environment pollution that would violate

Title VII.

Fourth, the behavior of Ketter was not the norm in

the workplace.

And his activities were not condoned by his

supervisors. And, fifth, the racist paraphernalia generated

and distributed by Ketter was limited and not pervasive in

15a

the work environment.

Defendant also argues that management at the Dallas

Water Department took an active role in curtaining the

activities of Ketter, and eventually transferred him out of

Plaintiffs work area when he proved uncontrite and

persisted in his disruptive and antagonistic behavior.

C. RETALIATION THEORY ARGUMENTS

Defendant argues that Plaintiff cannot prevail under

his retaliatory action theory under 42 U.S.C. §2000(e)

because he cannot meet the burden of proof to maintain

such an action: (1) that he was engaged in a protected

activity; (2) that an adverse employment action occurred;

and (3) that there is a causal connection between the

protected activity and the adverse employment decision.

Jones v. Flagship Intemat’l, 793 F.2d at 714, 724 (5th Cir.

1986).

Defendant contends that Plaintiff fails the second

prong of the test because he has not established that his

performance evaluations and timely merit increase in salary

16a

on March 12,1990 constitute an adverse employment action.

V. PLAINTIFF’S RESPONSE

Plaintiffs Response to Defendant’s Summary

Judgment Motion consists of four affidavits, all of which are

from fellow co-workers who discussed their recollection of

the many transgressions in the work place of Harry Ketter.

VI. DISCUSSION

The Court finds persuasive Defendant’s arguments

refuting Plaintiffs disparate treatment claim. Plaintiff has

not established a prima facie case of disparate treatment with

respect to promotions. A summary judgment ruling in favor

of Defendant on the disparate treatment claim is justified.

The Court finds persuasive Defendant’s arguments

refuting Plaintiffs hostile work environment theory. Harry

Ketter’s behavior in the workplace, gleaned from affidavits,

depositions and exhibits submitted by Plaintiff and

Defendant, was indeed unconscionable. But the Court finds

that Plaintiff has not met the standard for a hostile work

17a

environment set forth in Rogers, supra. While in retrospect

it may appear that Ketter’s supervisors should have taken

decisive action against Ketter in a more expeditious manner,

they cannot be faulted for taking the course they followed.

Ketter was afforded every opportunity to improve his

behavior. After Plaintiff advised Ketter’s supervisors of

Ketter’s disruptive and antagonistic activities, they began to

monitor Ketter’s activities and warned or reprimanded

Ketter when he transgressed. It was only after Ketter

proved unwilling to conform his behavior to the standards of

the workplace was he transferred out of Plaintiffs work area.

While Ketter’s behavior in the workplace is indefensible,

there is nothing inherently unlawful or inequitable about the

even handed and judicious treatment accorded Ketter by his

supervisors at DWU.

Furthermore, the very fact that Ketter was

indiscriminate in his antagonistic remarks and activities

mitigates against a finding that there exists a hostile work

environment within the meaning of Rogers. Ketter did not

18a

focus exclusively on Plaintiff. Rather, as the affidavits

Plaintiff cites in his Response attest, Ketter harassed all his

section co-workers equally. See Vaughn v. Pool Offshore Co.,

Etc., 683 F.2d 922 (1982).

The Court finds persuasive Defendant’s argument

countering Plaintiffs retaliation theory claims. Plaintiff does

indeed fail to meet the second prong of the three prong test

set forth in Jones, Id. He has not shown that an adverse

employment action occurred as a result of his engaging in a

protected activity, to wit: filing a complaint with the EEOC.

Consequently, Plaintiff also fails to meet the third prong of

the Jones test. A Summary judgment ruling in favor of

Defendant on Plaintiffs retaliation theory is therefore

justified.

C. RULING

Having considered the law and the evidence, the

Court GRANTS Defendant’s Motion For Summary

Judgment in all respects.

SO ORDERED.

19a

Signed this 23rd day of June, 1993

_____________ S/S______________

JORGE A. SOLIS

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

20a

3:90-CV-1783-P

IN THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF YTEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION

Filed July 23

CLEMENT BERNARD,

Plaintiff,

CITY OF DALLAS, CITY OF DALLAS WATER

DEPARTMENT

(Dallas Water Utilities),

Defendants.

FINAL JUDGMENT

By Memorandum Opinion and Order of this date, the

Court has granted Defendants’ Motion for Summary

Judgment.

It is ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that Plaintiff,

CLEMENT BERNARD, take nothing, and that the action

be dismissed with prejudice.

It is further ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that all

21a

relief not specifically granted herein is denied.

Signed this 23rd day of June, 1993

_____________ S/S______________

JORGE A. SOLIS

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

22a

Filed Apr. 07, 1994

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 93-1651

Summary Calenndar

CLEMENT BERNARD,

Plaintiff-Appellants,

vs.

CITY OF DALLAS AND CITY OF DALLAS WATER

DEPARTMENT

(Dallas Water Utilities),

Defendants-Appeliees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Texas

3:90-CV-1783-P

Before DAVIS, JONES, and DUHE, Circuit Judges.*

PER CURIAM:

"Local Rule 47.5 provides: "The publication of

opinions that have no precedential value and merely decide

particular cases on the basis of well-settled principles of law

imposes needless expense on the public and burdens on the

legal profession." Pursuant to that Rule, the Court has

determined that this opinion should not be published.

23a

On appeal from the trial court’s grant of summary

judgment against his claim of racial discrimination in

employment, appellant Bernard raises two issues. He

contends there were genuine issues of material fact

regarding whether the City of Dallas water department in

which he works was charged by a racially hostile

environment and whether he was denied a promotion

because of discrimination.

Although our analysis differs somewhat from that of

the district court, we affirm the grant of summary judgment.

1. The promotion claim.

Bernard asserts that he was discriminated against in

his attempts to be promoted to the rank of T-9 Instrument

Technician, but he did not present sufficient admissible

evidence that this was based on racial animus. Harry Ketter,

a coworker, could not directly influence this decision.

Further, Bernard did not pass the required test for

promotion. He was, however, promoted to T-9 Mechanic

Technician. He did not bring forth enough evidence to

24a

create a genuine fact issue concerning this claim.

2. The hostile environment claim.

We disagree with the district court’s conclusion that

Bernard did not produce sufficient evidence of a racially

hostile working environment. His coworker Ketter, who

substituted as supervisor occasionally, engaged in racially

insulting conduct and displayed materials derogatory of

blacks (and religion) in the workplace. This activity

apparently went on for some time, but management did not

take action to stop it until Bernard complained in October,

1988. At that time, management began regularly to enforce

its policy of preventing displays of offensive material.

Management also counseled regularly with Bernard and

Ketter in order to stem Ketter’s offensive conduct and insure

that everyone could work together. In January, 1989 Ketter

was transferred to another part of the plant where he would

not encounter Bernard. Later, Ketter was permanently

transferred.

While the circumstances, including Bernard’s

25a

summary judgment affidavits of coworkers, suggest that a

racially hostile working environment may have existed, they

also demonstrate that the managers of the water plant took

prompt remedial action when informed that Bernard found

Ketter’s conduct offensive. Within three months of

Bernard’s first complaint, Ketter was transferred to another

part of the plant. During that interval, management

counseled Ketter on several occasions to shape up.

Management’s handling of this situation after

Bernard complained never suggested that Ketter’s offensive

conduct was tolerated or excusable, nor did management

ever advise Bernard to ignore Ketter’s behavior. Bernard’s

summary judgment evidence did not contest the facts

concerning the city’s handling of Ketter’s misbehavior. The

city’s uncontroverted actions constituted a prompt remedial

response to Bernard’s complaints.

Because there was no genuine issue of material fact

raised in the foregoing particulars, the district court’s

judgment is AFFIRMED.