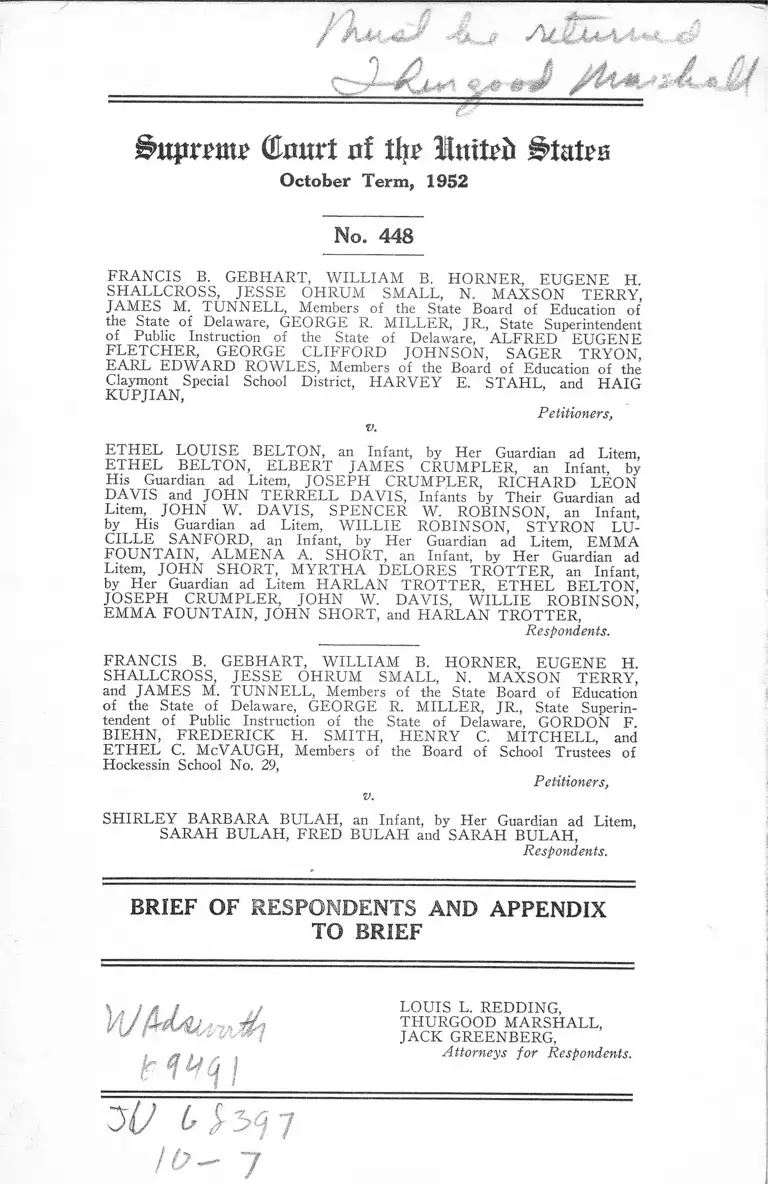

Gebhart v. Belton Brief of Respondents and Appendix to Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gebhart v. Belton Brief of Respondents and Appendix to Brief, 1952. 9d9901fe-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a5831ae4-c3b6-42f2-a118-6cba91648874/gebhart-v-belton-brief-of-respondents-and-appendix-to-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

gwprpmp (&mvt rtf lutfrfi States

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, WILLIAM B. HORNER, EUGENE H.

SHALLCROSS, JESSE OHRUM SMALL, N. MAXSON TERRY,

JAMES M. TUNNELL, Members of the State Board of Education of

the State of Delaware, GEORGE R. MILLER, JR., State Superintendent

of Public Instruction of the State of Delaware, ALFRED EUGENE

FLETCHER, GEORGE CLIFFORD JOHNSON, SAGER TRYON,

EARL EDWARD ROWLES, Members of the Board of Education of the

Claymont Special School District, HARVEY E. STAHL, and HAIG

KUPJIAN,

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem,

ETHEL BELTON, ELBERT JAMES CRUMPLER, an Infant, by

His Guardian ad Litem, JOSEPH CRUMPLER, RICHARD LEON

DAVIS and JOHN TERRELL DAVIS, Infants by Their Guardian ad

Litem, JOHN W. DAVIS, SPENCER W. ROBINSON, an Infant,

by His Guardian ad Litem, WILLIE ROBINSON, STYRON LU

CILLE SANFORD, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem, EMMA

FOUNTAIN, ALMENA A. SHORT, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad

Litem, JOHN SHORT, MYRTHA DELORES TROTTER, an Infant,

by Her Guardian ad Litem HARLAN TROTTER, ETHEL BELTON,

JOSEPH CRUMPLER, JOHN W. DAVIS, WILLIE ROBINSON,

EMMA FOUNTAIN, JOHN SHORT, and HARLAN TROTTER,

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, WILLIAM B. HORNER, EUGENE H.

SHALLCROSS, JESSE OHRUM SMALL, N. MAXSON TERRY,

and JAMES M. TUNNELL, Members of the State Board of Education

of the State of_ Delaware, GEORGE R. MILLER, JR., State Superin

tendent of Public Instruction of the State of Delaware, GORDON F.

BIEHN, FREDERICK H. SMITH, HENRY C. MITCHELL, and

ETHEL C. McVAUGH, Members of the Board of School Trustees of

Hockessin School No. 29,

SHIRLEY BARBARA BULAH, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem,

SARAH BULAH, FRED BULAH and SARAH BULAH,

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS AND APPENDIX

TO BRIEF

October Term, 1952

No. 448

Respondents.

Respondents.

LOUIS L. REDDING,

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

JACK GREENBERG,

Attorneys for Respondents.

~dU (f J 3d 7

/ O - 7

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Preliminary Statement ................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................... 2

Opinions Below .............................................................. 2

Questions Presented ..................................................... 3

Statutes Involved .......................................................... 3

Statement of the C ase ................................................... 4

Summary of Argument ............................................... 9

Argument ....................................................................... 9

Factors Relevant in Equating Educational Offer

ings ..................................................................... 9

I— The Injury Inflicted By Segregation ............... 11

II- A—The Judgment Below Should Be Affirmed

Because the Nature of the Right Requires Imme

diate Relief ............................................................ 13

II- B—There is No Evidence That Inequalities in

Facilities Will Be Corrected in One Y ear.............. 13

The Elementary Schools.................................... 13

The High Schools............................................... 15

III— Respondents Were Properly Admitted to

Schools Which Had Been Set Aside For Whites

Only, Because the Delaware Courts Cannot Ad

minister a Decree Ordering Equalization ............. 18

Appendix ...................................................................... 21

11

Table of Cases

PAGE

Gong Lnm v. Bice, 275 U. S. 7 8 ................................ 6,12

Helvering v. Lerner Stores, 314 IT. S. 463, 466 ......... 11

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State (Regents, 339 IT. S. 637.. 10,12

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ............................. 6,12

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631................ 12,13

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 IT. S. 629 ............................ 9,12,13

Taylor v. Smith, 13 Del. Ch. 39, 115 A. 405 .............. 18

Authorities Cited

Miller, Adolescent Negro Education in Delaware,

A Study of the Negro Secondary School and Com

munity Exclusive of Wilmington, p. 178.............. 11

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment .................................... 3, 5

Statutes and Constitution of the

State of Delaware

Constitution of the State of Delaware, Article X . . . . 21

Revised Code of Delaware, 1935, Par. 2631 ............. 21

32 Laws of Delaware, Ch. 163, Sec. 2 ....................... 17, 23

37 Laws of Delaware, Ch. 202, Sec. 1 ....................... 17, 23

Ihtpmt? ©our! of ttft Inttefr States

October Term, 1952

No. 448

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, WILLIAM B. HORNER, EUGENE H,

SHALLCROSS, JESSE OHRUM. SMALL, N. MAXSON TERRY,

JAMES M. TUNNELL, Members of the State Board of Education of

the State of Delaware, GEORGE R. MILLER, JR., State Superintendent

of Public Instruction of the State of Delaware, ALFRED EUGENE

FLETCHER, GEORGE CLIFFORD JOHNSON, SAGER TRYON,

EARL EDWARD ROWLES, Members of the Board of Education of the

Claymont Special School District, HARVEY E. STAHL, and HAIG

KUPJIAN,

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem,

ETHEL BELTON, ELBERT JAMES CRUMPLER, an Infant, by

His Guardian ad Litem, JOSEPH CRUMPLER, RICHARD LEON

DAVIS and JOHN TERRELL DAVIS, Infants by Their Guardian ad

Litem, JOHN W. DAVIS, SPENCER W. ROBINSON, an Infant,

by His Guardian ad Litem, WILLIE ROBINSON, STYRON LU

CILLE SANFORD, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem, EMMA

FOUNTAIN, ALMENA A. SHORT, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad

Litem, JOHN SHORT, MYRTHA DELORES TROTTER, an Infant,

by Her Guardian ad Litem HARLAN TROTTER, ETHEL BELTON,

JOSEPH CRUMPLER, JOHN W. DAVIS, WILLIE ROBINSON,

EMMA FOUNTAIN, JOHN SHORT, and HARLAN TROTTER,

Respondents.

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, WILLIAM B. HORNER, EUGENE H.

SHALLCROSS, JESSE OHRUM SMALL, N. MAXSON TERRY,

and JAMES M. TUNNELL, Members of the State Board of Education

of the State of Delaware,. GEORGE R. MILLER, JR., State Superin

tendent of Public Instruction of the State of Delaware, GORDON F.

BIEHN, FREDERICK H. SMITH, HENRY C. MITCHELL, and

ETHEL C. McVAUGH, Members of the Board of School Trustees of

Hockessin School No. 29,

SHIRLEY BARBARA BULAH, an Infant, by Her Guardian ad Litem,

SARAH BULAH, FRED BULAH and SARAH BULAH,

Respondents.

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS AND APPENDIX

TO BRIEF

Preliminary Statement

The petition for writ of certiorari filed in this Court

on November 13, 1952, was served upon respondents on

November 17, 1952. Because of the grave importance of

2

the issues raised and their similarity to issues raised in

Nos. 8, 101, 191, and 413, pending before this Court, re

spondents waived the filing of a Brief in Opposition and

moved that, if certiorari were granted, the argument be

advanced and heard immediately following argument on

the above-numbered cases.

On November 24, 1952, this Court entered an order

granting the petition for writ of certiorari and granting

respondents’ motion to advance. Brief for petitioners is

to be filed not later than three weeks after argument.

So that before argument the Court will have before it a

fuller exposition of the facts and issues than could be con

tained in the petition for writ of certiorari and so that the

Court may have before it a fuller exposition of their posi

tion, respondents are filing their Brief in advance of peti

tioners’ Brief.

Jurisdiction

The statement as to jurisdiction is set forth in the

petition for writ of certiorari.

Opinions Below 1

The opinion of the Chancellor of the State of Delaware

(A. 338) is reported in 87 A. (2d) 862. The opinion of the

Supreme Court of the State of Delaware (B. 37) is reported

in 91 A. (2d) 137.

1 The record in this case consists of five separate parts: appendix

to petitioners’ brief in the court below, the supplement thereto, appen

dix to respondents’ brief in the court below, the supplement thereto,

and the record of proceedings in the Supreme Court of Delaware.

These will be referred to in respondents’ brief as follows:

Appendix to petitioners’ brief below will be indicated by A; the

supplement to the petitioners’ appendix below will be referred to as

SA ; respondents’ appendix below will be referred to as R A ;

the supplement to respondents’ appendix below will be referred

to as R SA ; the record of proceedings in the Supreme Court of Dela

ware will be referred to as R.

3

Questions Presented

1. Whether in cases in which the evidence establishes

that racial segregation imposed by the State creates inferior

education for Negro school children, the State constitution

and statutes causing such inequality should be struck down

to the extent that they require segregation, as contrary to

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution.

2. Whether in cases in which the evidence establishes

that the State offers Negro children educational oppor

tunity inferior to that which it offers white children simi

larly situated, the courts below were correct in ordering

admission of the Negro children to the superior facilities

pursuant to the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the United States Constitution.

3. Whether, where the Courts of the State of Delaware

have stated in this case that they do not see how a decree

ordering inferior educational facilities equalized could be

administered by a court of equity, they were correct in

ordering, as the only available relief, Negro respondents

admitted to schools which, pursuant to State constitution

and statutes had been maintained exclusively for white

children.

Statutes Involved

The constitutional and statutory provisions of the State

of Delaware involved in this case are printed in the Appen

dix to this brief.

4

Statement of the Case 2

This litigation arises from two several complaints (A.

3-13, 13-30) filed in class actions in the Court of Chancery

of the State of Delaware by Negro school children and their

guardians (respondents here) seeking admittance of the

children to two public schools maintained by the petitioners,

as agents of the State of Delaware, exclusively for white

children in New Castle County, Delaware.

One complaint (A. 3-13) alleges that respondents, resid

ing in the Claymont Special School District, were refused

admittance to the Claymont High School, maintained by

petitioner members of the State Board of Education and

members of the Board of Education of the Claymont Special

School District. This refusal was solely because of respond

ents ’ 3 color or ancestry. As a consequence, respondents

are required to attend the Howard High School (BA. 47), a

public school maintained separately for Negroes in Wil

mington, Delaware. This high school conducts classes in

two separate buildings, one known as “ Carver” being nine

city blocks from the main Howard Building (BA. 50). All

Wilmington public schools, including* Howard, are operated

and controlled by the corporate “ Board of Public Educa

tion in Wilmington,” which is not a party to this cause

(A. 314-315, 352, B. 57, BA. 203).

2 This statement of facts is a concise description of what has gone

before in accordance with the rules. However, in view of the brevity

of time between the granting of certiorari and the argument herein,

and in view of the complicated state of the record which has been filed

consisting of five volumes numbering more than 700 pages which in

large part overlap, respondents believe that the Court may be assisted

in following the evidence by a somewhat lengthier statement which

organizes the evidence taken below. For this purpose, we have placed

in the appendix to this brief such a statement, which we hope will be

of assistance to the Court in following the record.

3 “Respondents” hereafter in this brief refers to the infant re

spondents.

5

The second complaint (A. 14-30) alleges that the

respondent, seven years old, resides in the village of

Hockessin (A. 28) and that solely because of her color was

refused admittance to Hockessin School No. 29, a public

elementary school, comprising grades one to six, which is

maintained exclusively for white children by petitioner

members of the State Board of Education and petitioner

members of the Board of School Trustees of Hockessin

School No. 29. The separate Hockessin School No. 107 is

maintained for Negroes, by the aforesaid State Board of

Education.

Respondents in both complaints assert that this exclu

sion, or segregation (a) requires respondents to attend

schools substantially inferior to the schools for white chil

dren to which admittance is sought and (b) injures the

mental health, impedes the mental and personality develop

ment of respondents and thereby also makes inferior their

educational opportunity as compared with the educational

opportunity afforded white children living in Claymont and

Hockessin. Such exclusion, respondents assert, is pro

hibited by the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

Petitioners’ answers (A. 31-33, 34-37) in both cases

defend the exclusion (a) upon mandatory constitutional and

statutory provisions of the State of Delaware requiring that

separate schools be maintained for white and colored chil

dren and (b) upon the claim that the educational oppor

tunities and advantages afforded respondents by petitioners

are equal to those afforded white children -similarly situated.

The two cases were consolidated and tried before the

Chancellor.

In an opinion (A. 338-356) filed April 1, 1952, the Chan

cellor set forth a finding of fact, based on the undisputed

oral testimony of experts in education, sociology, psychol

ogy, psychiatry and anthropology (A. 340-341) that in “ our

Delaware society,” segregation in education practiced by

petitioners as agents of the State “ itself results in the

6

Negro children, as a class, receiving educational oppor

tunities which are substantially inferior to those available

to white children otherwise similarly situated.” However,

the Chancellor denied respondents’ prayers for a judgment

declaring that the Delaware constitutional and statutory

provisions violate respondents ’ right to equal protection.

The disputed issues of fact as to the inequality of the

“ Negro” schools as compared to the “ white” schools, the

Chancellor resolved by finding the former substantially

inferior to the latter. As to the high school for Negroes,

he based this conclusion on his factual finding of inferiority,

by comparison, in the following factors, which he viewed

both independently and cumulatively: teacher training,

pupil-teacher ratio, extra-curricular activities, physical

plant and esthetic considerations, and the greater burden,

time-wise and distance-wise, suffered by respondents in

attending this school. As to the elementary school for

Negroes, the trial court found it inferior in building and

site, including esthetic values, teacher preparation, and in

a total absence of transportation facilities or the equivalent

thereof.

Expressly rejecting, for reasons to which we shall refer

later (A. 352-353), petitioners’ contention that they should

be directed to equalize the inferior segregated educational

facilities assigned to respondents, the Chancellor issued an

order, dated April 15, 1952, enjoining petitioners from ex

cluding respondents, because of color from the high school

and the elementary school found to be superior.

On appeal by the school officials, the Supreme Court of

Delaware, in an opinion dated August 28, 1952, determined

that the Chancellor’s factual finding that State-imposed

segregation in public schools and equality of education are

inherently incompatible was, in view of the doctrine enunci

ated by this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537

(1896), and Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 (1927), “ imma

terial.” The Delaware Supreme Court therefore expressly

7

approved the Chancellor’s declination of a declaratory judg

ment that the Delaware Constitution and statutes providing

for schools segregated on the basis of color contravened

respondents ’ right to equal protection.

A stipulation was filed in the Supreme Court of Delaware

setting forth counsel’s acknowledgment that the “ schedule

of the Wilmington Board of Education calls for” transfer

of three grades at the Howard High School to another

Wilmington school in September, 1953 (It. 35-36).

The Supreme Court of Delaware reviewed the evidence

relating to educational facilities for the purpose of making

its independent finding of fact and drawing its own conclu

sion as to whether there was “ substantial equality” (E. 45).

As to both high school facilities and elementary school

facilities, the Supreme Court concluded that those afforded

respondents were not substantially equal to those available

to white children similarly situated and that plaintiffs were

injured by the inequality (E. 56, ,B. 63).

However, in reaching this conclusion the appellate court

rejected conclusions of the trial court that certain of the

factors compared were influential, or differed as to the

degree of the influence. In evaluating the evidence as to

the high schools, the appellate court found that differences

in pupil-teacher ratio and formal training of teachers were

not sufficiently significant to warrant a finding of inferiority

in the “ Negro” school in those respects. Differences in

extra-curricular activities also were deemed too insubstan

tial to support a finding of inequality. There was, however,

no rejection by the appellate court of any of Chancery’s

conclusions with respect to the equation between the ele

mentary schools.

Under the sub-heading “ Belief” , the opinion of the

State Supreme Court also specifically pondered whether

“ the form of the [Chancellor’s] decree,” in directing de

fendants to admit plaintiffs to the facilities found to be

superior was erroneous (E. 56). The Supreme Court con

8

sidered the appropriateness of a decree to equalize the

high school facilities and noted two preliminary difficulties:

one, that the legal entity having control of the Wilmington

public schools was not a party to the cause; two, that the

court could not see how it could supervise and control the

expenditure of state funds in a matter committed to the

administrative discretion of school authorities. Determin

ing, with respect to the high school facilities, that “ To

require the plaintiffs to wait another year under present

conditions would be in effect to deny them that to which we

have held they are entitled, ’ ’ the Supreme Court upheld the

“ injunction of the court below” as “ rightly awarded”

(R. 58).

As to the relief with respect to the inferior elementary

school facilities, the Delaware Supreme Court said: “ The

burden was clearly upon the defendants to show the extent

to which the remedial legislation had improved conditions

or would improve them in the near future. This the de

fendants failed to do.” The Court then alluded to its ante

cedent discussion of the matter of relief for the high school

respondents and said: “ It accordingly follows that the

Chancellor’s order in respect of the admittance of the

plaintiff” [respondent, here] to the elementary school found

to be superior “ must be affirmed” (R. 63).

Mandates of affirmance of the judgment of the Court of

Chancery in the high school and elementary school cases

were issued separately by the Supreme Court on September

9,1952 (R. 65, 66).

On September 23,1952, a motion was made by petitioners

to the Chancellor for a stay of his order of April 15, 1952,

and denied by the Chancellor (Appendix to Respondents’

brief, p. 26).

Motion to the Supreme Court of Delaware to review the

Chancellor’s order denying a stay was made by the peti

tioners on September 25, 1952, and the same day denied by

the court (Appendix to Respondents’ brief, pp. 25-27).

9

Summary of Argument

The kind of harm here inflicted by segregation warrants

affirming the judgment below because this Court has legally

recognized such injury in prior cases.

The other injuries inflicted by inferiority in perhaps

more measurable facilities also require affirming the order

of immediate admission because immediacy is an integral

part of the right.

The Delaware courts have held that they cannot issue

the kind of decree the State requests. Therefore the decree

which was issued represents the only method by which relief

can be granted.

Argument

F ac to rs R e lev an t In E q u a tin g E d u ca tio n a l O fferings

In determining whether two educational offerings are

“ equal” or not, the first problem appears to be to select

the factors to be placed on each side of the equation. This

Court has never exhaustively catalogued these; it has

never been called upon to do so. And it is probably impos

sible to compile a complete list in a field as dynamic as

education. But, this Court has set up some criteria. For

purposes of this case, we may turn also to specific factors

which professional educators deem relevant, certainly, at

least insofar as petitioners’ witnesses agreed with respond

ents.

In several recent cases dealing with education at a

different level, this Court has pointed out factors which

are or might be significant in the kind of equation we are

trying to set up. In the case of a law school (Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U. S. 629), it has especially noted the number

of the faculty, variety of courses, and opportunity for

specialization, size of student body, scope of the library,

and certain extra-curricular activities. Qualities ‘ ‘incapable

10

of objective measurement” have also been weighed and it

was pointed out that the law school cannot be effective in

isolation from the individuals and institutions with which

the law interacts.

In dealing with graduate education preparatory to

teaching (McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S.

637), this Court again considered the factor of enforced

isolation in that setting and determined that appellant

there was thereby handicapped in his pursuit of effective

graduate instruction.

That there are specific factors relevant in judging the

institutions which are the subject of this case need not be

left to counsel’s interpretation of the decided cases. Pro

fessional educators, witnesses for respondents and petition

ers have agreed on many, and respondents’ witnesses were

uncontradicted as to the importance of others. These

included factors related to those detailed above. Let us

list them.

1. Travel. Respondents’ testimony (RA. 131 et seq.),

Petitioners’ testimony (RSA. 31).

2. Sites and Buildings. Respondents’ testimony (RA.

59,114, 136), Petitioners’ testimony (RSA. 25, 26, 31).

3. Teacher training, teaching load. Respondents’ testi

mony (RA. 62, 65; RSA. 25, 26, 30), Petitioners’ testimony

(RSA. 18, 31).

4. Class size. Respondents’ testimony (RA. 64), Peti

tioners’ testimony (RA. 163, 177; RSA. 20).

5. Curriculum. Respondents’ testimony (RA. 66; RSA.

2), Petitioners’ testimony (RA. 178-179; RSA. 28-29).

6. Extra-curricular activities. Respondents’ testimony,

(A. 99, 137), Petitioners’ testimony (RSA. 29).

7. The effects of segregation. Respondents’ testimony

(RA. 69 et seq., 99, 123 et seq., 141 et seq., 144-145, 146 et

seq., 151 et seq., 155 et seq.).

11

Petitioners did not contradict this testimony. But for

agreement with this testimony see Miller, Adolescent Negro

Education in Delaware, a Study of the Negro Secondary

School and Community Exclusive of Wilmington (1943),

p. 178. This is a doctoral thesis written by the State

Superintendent of Education of the State of Delaware

(A. 308) who is one of the petitioners in this case. It is

on file in the Library of Congress, among other places.4

The courts below found inequalities in most of these

areas, and the problem with which they were faced was to

determine what legal consequences flowed from such dis

crepancies.5

I

The Injury Inflicted By Segregation

We urge that in affirming the judgment of the court

below this Court give recognition and legal validity to the

facts indisputably established in the record and found

by the Chancellor, to the effect that state-enforced racial

segregation inflicts a grievous mental injury on the Negro

children who are set apart in education, even though this

reasoning was rejected in the courts below.6

4 “If one could be assured that equal opportunities for education

would be realized under a policy of segregation, one would not

consider the practice as entirely unfair. But if one considers edu

cation as life, and that the schools must somehow or other reproduce

within themselves opportunities for life, segregation offers little

opportunity to meet this requirement.” Miller, supra, at p. 178.

5 See the Statement of the Case, supra, pp. 6-7, and the Appendix

hereto, infra, pp. 27-44, for a detailed exposition of the inequalities.

6 Cf. Helvering v. Lerner Stores, 314 U. S. 463, 466: “. . . Re

spondent filed no cross-petition for certiorari. Yet a respondent

without filing a cross-petition, may urge in support of the judgment

under review grounds rejected by the court below.”

12

The Court of Chancery held that the Negroes’ mental

health and therefore their educational opportunity are

adversely affected by state imposed segregation in educa

tion. But the Chancellor also held that he could not legally

recognize the factual condition because to do so would be

in effect to rule that racially segregated educational facil

ities for Negroes could never be equal to those set apart

for whites and were, therefore, unconstitutional; whereas,

this Court had fairly implied that racial segregation in

education is constitutional. The Supreme Court of Dela

ware accepted this legal conclusion and did not review

the factual finding.

Stating the matter simply, we do not believe that this

Court, in the Plessy and Gong hum casfes, to which the

Chancellor referred, intended to uphold racial segregation

irrespective of what could be established concerning its

effects. We do not believe that it was intended that facts

which could demonstrate the impossibility of segregated

facilities being equal should be ignored. They were not

ignored in the McLaurin case, and they were not ignored

in the Sweatt case. (Even the Gong Lum case, upon which

petitioners so heavily rely, stated that if the pleadings had

alleged inconvenience to the plaintiff there, a different

issue would have been presented. And the injuries in

flicted by segregation which this record reveals are more

serious than mere inconvenience.)

To deny legal validity to what the record has clearly

shown and remit plaintiffs to the vicissitudes of an ever-

changing educational picture would place them under a

threat of litigation that would cover all their school years.

Where the undisputed testimony, as here, reveals that no

matter what physical changes are instituted, Negro children

will be disadvantaged by segregation, only a decision based

on that ground can fully protect respondents’ rights to

equality.

13

il-A

The Judgment Below Should Be Affirmed

Because the Nature of the Right Requires

Immediate Relief

But even if relief on this ground is denied, we submit

that the grounds employed by the court below are reasons

why the judgment should be affirmed. After all, there is

no reason why respondents should be denied the perhaps

more measurable opportunities which the State had denied

them. An education consists of so many years of school

ing and the more time respondents are required to spend

in inferior schools, to that degree is their sum total of

education inferior. The sooner respondents are admitted

the closer can they come to full equality in total educa

tion although, unfortunately, there is no way to recoup

the losses of earlier segregated years. Immediate admis

sion is an integral part of the right—full equality.

The necessity of such immediacy has been determined

by this Court, Sweatt v. Painter,, 339 U. S. 629; Sipuel v.

Board of Regents, 332 IT.’ S. 631.

II-B

There is No Evidence That Inequalities in

Facilities W ill Be Corrected in One Year

T h e E lem en ta ry Schools

Petitioners can refer to no evidentiary support for

their claim of effective equalization in one year. At pages

5-6 of their petition, they assert that “ inequalities with

the equalization of funds provided in the last few years,

will probably shortly disappear,” and they refer to part

of the opinion of the Supreme Court of Delaware set forth

at R. 62-63, presumably as support. However, fuller

14

reference to the whole text of the opinion reveals the

infirmity of petitioners’ claim of any support therein.

The Delaware Supreme Court compared the two ele

mentary schools in (1) public funds, (2) buildings and

sites, (3) equipment, (4) teachers, (5) transportation. As

to #1, public funds, the Court found current equality,

but “ prior inequality” in the allotment of public funds

continued “ of importance” in the equation. As to #3,

equipment, substantial inequality was found in one item,

namely, “ medical supplies and equipment,” with no sub

stantial inequality in the remaining equipment. With

respect to #2, buildings and sites, #4, teachers, and #5,

transportation, the Court found substantial inequality.

The Supreme Court of Delaware found the petitioners

had proved nothing in the way of substantial progress in

the direction of equalization of existing inequalities.

As to #2, buildings and sites, the Court said: “ There

is testimony that the State in recent years has spent or

allotted funds for School 107, [for Negroes] in excess of

those budgeted, for ‘delayed repairs’. This fact would

indicate an attempt to improve the condition of the build

ing of No. 107, but the State proffered no testimony that

such expenditures had been made or had substantially

equalized the condition of the physical plants of the two

schools, or would equalise them in the near future. Knowl

edge of the facts must certainly by attributed to the de

fendants, and this failure to adduce them, or to show that

disparities in the physical plant would he promptly

remedied, is significant. ’ ’

As to #4, teachers, the Court found those at the school

for whites “ possess a superiority” and pointed out that

an inequality in salaries for teachers at the school for

Negroes was “ a direct violation of our constitutional and

statutory provisions . . .” . “ Beginning with the fiscal

year of 1951-1952 this inequality has been remedied. The

15

plaintiff’s testimony, however, related to conditions at

School No. 107 in October, 1951, [the time of the trial]

and thus tended to show that the effect of the prior wrongful

apportionment of funds still persisted. The burden was

clearly upon the defendants to show the extent to which

the remedial legislation had improved conditions or would

improve them in the near future. This the defendants

failed to do.”

As to #5, transportation, no showing was made by

petitioners of measures looking toward effectuation of

equality.

Upon analysis, petitioners’ assumption that they have

made a reasonable showing of correcting, within any

definite time, or at all, the inequalities which both the

Delaware trial and appellate court concluded to exist in

the facilities at the elementary school for respondents, is

baseless.

T he High Schools

The Supreme Court of Delaware found, and approved

the trial court’s finding of, substantial inferiority of the

physical plant available to respondents at Howard-Carver

as compared to the physical plant to which respondents

sought admittance. Specifically included in this item were

site and the esthetic attributes thereof.

As to instruction, the State Supreme Court found that

available to respondents in the subject of physical educa

tion clearly unequal.

As to travel and facilities therefor, the court below

declared there was “ clear evidence of substantial inequality

and unlawful discrimination on account of race or color.”

Petitioners expressly disclaim making challenge to these

findings of inequalities (Petition, 4). However, to sub

stantiate their contention that they have “ reasonably

16

shown” the possibility and probability of elimination of such

inequalities in one year, petitioners now contend that they

established and that the court below found (Petition, p. 5)

that the “ schedule” of the Wilmington Board of Education

contemplates certain changes to be accomplished by the

beginning of the school year in September, 1953. These

changes include removal of three grades at the Howard

High School, enlargement of that school, and abandonment

of its Carver building. An additional high school for

Negroes is under construction in New Castle County.7

Petitioners, however, fail to take into account in their claim

of possible and probable future equalization, that Clay-

mount also is planning an extensive building program to

improve its school (A. 76).

Both Delaware courts throughly canvassed these asser

tions of prospective change, weighing them in connection

with petitioners’ request for a decree to equalize facilities.

The trial court determined that it could not see how the

plans advanced by petitioners would “ remove all the objec

tions to the present arrangement” (A. 352). That is to

say, even if and when consummated, petitioners’ projected

changes would not produce substantial equality of the

separate and inferior high school facilities for Negroes.

The trial court further declared: “ I conclude that the

State’s future plans do not operate to prevent the granting

of relief to these plaintiffs by way of an injunction prevent

ing the authorities from excluding these plaintiffs, and

others similarly situated, from admission to Claymont High

School on account of their color” (A. 353).

The Delaware Supreme Court stressed, first, that “ the

Board of Education of the City of Wilmington, which has

7 One of the petitioners, the State Superintendent of Education,

testified that this new school would be located 30 miles from Clay

mont, respondents’ home community, and would entail 60 miles of

travel per day for them (RA. 184).

17

direct supervision of the Wilmington schools, is not a party

to the cause” (R. 57). That is to say, the claim of change

by petitioners was wholly gratuitous, since petitioners were

utterly without power to bring them about. The Wilming

ton Board of Public Education was not shown to be under

any duty to petitioners to make the alleged changes. Since

that Board,8 not petitioners, control the public schools in

Wilmington, that Board could with impunity change its

plans for change.

To pursue this further: The separate high school facili

ties available to respondents are located in the city of

Wilmington (RA. 46). They are part of the public school

system of Wilmington.8 See also the last quoted remarks

of the Supreme Court of Delaware, supra. The petitioner

State Superintendent of Public Instruction testified that

the petitioners “ have no function of administration or

organization in any specific sense under the law as far as

schools of Wilmington are concerned” (A. 315). The peti

tioners could not require the Wilmington public school

authorities to establish “ a certain course at a certain

school” (A. 315) or, it appears, select textbooks from lists

published by petitioners, the members of the State Board

of Education (A. 315-316). The public schools in Wilming

ton are administered and controlled by the “ Board of Public

Education in Wilmington,” a corporate entity,8 which,

as both Delaware courts (A. 352, R. 57) pointed out, is not

a party to this action. Since petitioners do not administer

or control the Wilmington public schools a decree ordering

8 Respondents call attention to the following statutes of the State

of Delaware set forth in the Appendix to this brief, p. ,

37 Laws of Delaware, Ch. 202, Sec. 1—creating the Board of Public

Education in Wilmington as a body corporate and vesting in it title

to all public school property in the city of Wilmington; 32 Laws of

Delaware, Ch. 163, Sec. 2—conferring on the Board of Public Edu

cation in Wilmington control and management of all public schools

and public school property in the city of Wilmington and all powers

of administration of the public school system therein.

18

them to equalize high school facilities in that city—which

are the only high school facilities petitioners assert there

are plans to equalize—would be a futility. Since the cor

porate entity that controls the Wilmington facilities is not

a party to these proceedings, a decree directed against it

also would be a futility and legally impermissible. The

Delaware courts have previously held that a decree preju

dicial to a person having a material interest in the subject-

matter of a suit cannot be made unless such person is

before the Court as a party, is a well-established elementary

principle. Taylor v. Smith, 13 Del. Ch. 39, 115 A. 405.

Ill

Respondents W ere Properly Admitted to

Schools W hich Had Been Set Aside For

W hites Only, Because the Delaware Courts

Cannot Administer a Decree Ordering

Equalization

But apart from all that has been stated above, immediate

admission to the superior facilities is the only remedy for

another compelling reason. No one denies that there are

inequalities, and the facts as to their nature and extent

have been thoroughly presented above.

Now, the Attorney General of Delaware says that a

decree to equalize the inferior facilities is called for. But,

the Court of Chancery and the Supreme Court of Delaware

have held in this case, as a matter of State law, that they

do not see how an equalization decree could be implemented

(A. 352-353, R. 57).

If respondents are entitled to some relief, as the State

concedes, and if Delaware courts find it so difficult to issue

a decree to equalize facilities that they refuse to issue it

(though if they could we would consider it inadequate),

19

then the only available relief is the admission order which

was issued.

W herefore respondents pray that the judgment below

be affirmed.

Louis L. Redding,

Thurgood Marshall,

J ack Greenberg,

Attorneys for Respondents.

21

APPENDIX

Article X of the Constitution of the State of Delaware

provides in part as follows:

“ Section 1. The General Assembly shall provide

for the establishment and maintentance of a general

[fol. 46] and efficient system of free public schools,

and may require by law that every child, not physi

cally or mentally disabled, shall attend the public

school, unless educated by other means.

“ Section 2. In addition to the income of the in

vestments of the Public School Fund, the General

Assembly shall make provision for the annual pay

ment of not less than one hundred thousand dollars

for the benefit of the free public schools which, with

the income of the investments of the Public School

Fund, shall be equitably apportioned among the

school districts of the State as the General Assembly

shall provide; and the money so apportioned shall

be used exclusively for the payment of teachers’

salaries and for furnishing free text books; pro

vided, however, that in such apportionment, no dis

tinction shall be made on account of race or color,

and separate schools for white and colored children

shall be maintained. All other expenses connected

with the maintenance of free public schools, and

all expenses connected with the erection or repair of

free public school buildings shall be defrayed in

such manner as shall be provided by law.”

Paragraph 2631, Revised Code of Delaware, 1935, pro

vides as follows:

“ Sec. 9. Shall Maintain Uniform School Sys

tem; Separate Schools for White Children, Colored

Children, and Moors; Elementary Schoo l sThe

22

State Board of Education is authorized, empowered,

directed and required to maintain a uniform, equal

and effective system of public schools throughout

the State, and shall cause the provisions of this

Chapter, the bylaws or rules and regulations and the

policies of the State Board of Education to be car

ried into effect. The schools provided shall be of

two kinds: those for white [fol. 47] children and

those for colored children. The schools for white

children shall he free for all white children between

the ages of six and twenty-one years, inclusive; and

the schools for colored children shall be free to all

colored children between the ages of six and twenty-

one years, inclusive. The schools for white children

shall be numbered and the schools for colored chil

dren shall be numbered as numbered prior to the

year 1919. The State Board of Education shall

establish schools for children of people called Moors

or Indians, and if any Moor or Indian school is in

existence or shall be hereafter established, the State

Board of Education shall pay the salary of any

teacher or teachers thereof, provided that the school

is open for school sessions during the minimum num

ber of days required by law for school attendance

and provided further that such school shall be free

to all children of the people called Moors, or the

people called Indians, between the ages of six and

twenty-one years. No white or colored child shall

be permitted to attend such a school without the per

mission of the State Board of Education. The pub

lic schools of the State shall include elementary

schools which shall be of such number of grades as

the State Board of Education shall decide after con

sultation with the Trustees of the District in which

the school is situated.”

23

37 Laws of Delaware, Chapter 202, Section 1

Section 1. That the City of Wilmington with the terri

tory within its limits, or which in the future may be included

by additions thereto, shall be and constitute a consolidated

school district, and the supervision and government of pub

lic schools and public school property therein shall be vested

in a board of six members, to be called and known as the

‘ ‘ Board of Public Education in Wilmington, ’ ’ Said Board,

as hereinafter constituted, is hereby created a corporation,

having perpetual existence and succession, and by and in

said name shall have power to purchase, lease, receive, hold

and sell property, real and personal, sue and be sued, and to

do all things necessary to accomplish the purpose for which

such school district is organized, and shall succeed to and be

vested with, and be seized and possessed of all the privileges

and property of whatever kind or nature granted or belong

ing to any previous school corporation, or Board of Educa

tion, or school districts in the City of Wilmington and said

territory, or officers thereof authorized or empowered by an

enactment of the General Assembly of the State to do any

thing in reference to public education, or to hold any of said

property.

32 Laws of Delaware, Chapter 163, Section 2

P a ra g ra p h s 1 a n d 2

Section 2. The Board of Public Education in Wilming

ton shall have general and supervising control, government

and management of all the public schools and public school

property of the city; shall exercise generally all powers in

the administration of the public school system therein,

appoint such officers, agents and employees as it may deem

necessary, define their duties and fix their compensation;

24

shall have power to fix the time of its meetings, to make,

amend and repeal rules and by-laws for its meetings and

proceedings, for the government, regulation and manage

ment of the public schools and school property of the city,

and for the transaction of its business. The said Board also

shall have power:

1. To establish kindergartens, playgrounds, elementary

schools, secondary schools, high schools, manual training

schools or classes, trade, vocational and continuation schools

or classes, evening schools, schools for adults, whether

native or foreign-born, special and truant schools, training

schools or classes for teachers, or any other schools or

classes which it may deem necessary or wise, for the purpose

of training and educating the inhabitants of said city,

whether minors or adults; and to discontinue or consolidate

any of such schools or classes.

2. To establish or change the grades of all schools and

to adopt and modify courses of study therefor.

25

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE

---------------------------------o — — — — ■

No. 15, A. D. 1952

F rancis B. Gebhart, et al,

vs.

Appellants,

E thel L ouise Belton, et al,

Appellees.

No. 16, A. D. 1952

F rancis B. Gebhabt, et al,

vs.

Appellants,

Shirley Barbara Bulah, et al,

Appellees.

o

(September 25, 1952)

Southerland, C. J ., and Wolcott, J., sitting.

Application of defendants below to review an order of

tbe Chancellor of September 23, 1952.

H. Albert Yonng, Attorney General, and Louis J. Finger,

Deputy Attorney General, for the applicants.

Louis L. Redding, of Wilmington, opposed.

26

Southerland, C. J .: .

This is an application to review an order of the Chan

cellor dated September 23, 1952, refusing a stay of the

provisions of his final order of April 15, 1952, in the cause

below, directing the admission of the infant plaintiffs to

certain public schools of this State.

The opinion of this Court in the cause was filed August

28, 1952. Under the provisions of Rule 14 the mandate of

this Court issues as of course to the court below in the

absence of a petition for re-argument, unless the Court

otherwise orders. No such petition or order was made

within the ten-day period, and the mandate duly issued in

accordance with the Rules.

On September 23, 1952, the defendants applied to the

Chancellor for a stay of the final order of April 15, 1952.

That order had been partly carried into effect by the admis

sion of the infant plaintiffs to the public schools as required.

The application for stay was of a limited nature, that is, a

stay barring the admission to the Claymont and Hockessin

schools of any other Negro pupils similarly situated.

The Chancellor denied the application for a stay and

the defendants now seek a review of his order of denial.

We find three infirmities in the position of the de

fendants.

First. The application purports to be one under Rule 22

of this Court with respect to stays of proceedings in equity.

We do not think Rule 22 has any application to the case. It

refers to stays in connection with appeals to this Court.

There is no appeal pending in this Court and we think we

are without power or jurisdiction to review the Chancellor’s

order. The present application cannot be considered as an

application for further relief under paragraph 4 of the final

order of the Chancellor of April 15, 1952, since no factual

showing justifying such an application has been made.

Second. If, however, this application (notwithstanding

the failure to comply with our rules respecting appeals)

27

may be regarded as properly bringing before this Court the

merits of the Chancellor’s decision, we think that he was

clearly right in refusing the application. It appears to be

settled law that after affirmance of a decree of the trial court

and the issuance of a mandate to that effect any further

proceedings below must be in accordance with the mandate.

Here the judgment of the court below, affirmed by this Court,

was that those “ similarly situated” were entitled to the

benefit of the decree. The defendants’ application is in

effect that those “ similarly situated” be denied the benefit

of the decree. Thus the stay requested of the Chancellor

would be in contravention of the mandate of this Court.

Third. The purpose of the defendants to maintain the

status quo pending certiorari proceedings in the Supreme

Court of the United States could readily have been achieved

by an appropriate application to this Court within the time

permitted by Rule 14. If the period of ten days specified

could have been made for an extension of time. No applica

tion of any sort was made by the defendants within the time

allowed, and the present application comes too late.

The application is denied.

(Clerk’s certificate to foregoing paper omitted in print

ing.)

The Evidence

Educational O p p o rtu n ity — C laym ont vis-a-vis Howard

Travel and Its Significance

Undisputed testimony of plaintiffs (RA. 46-49) and

admission in defendants’ answer (Answer in No. 258, par. 6,

RA. 15-16) show that these plaintiff children must travel

daily, by walking and public bus, nine miles from Claymont

to Wilmington to attend all-Negro Howard High School

and that in making the eighteen-mile roundtrip fifty min

28

utes are consumed each way. Claymont High School is

one and one-half miles from plaintiffs’1 homes and, afoot

and by public bus, travel one way would consume twenty-

three minutes. Some of the courses for Howard Students

are given at Carver (ESA. 21), which is part of Howard

(ESA. 21), in a building nine and one-half city blocks from

the main Howard location (EA. 48), so that plaintiff Ethel

Louise Belton, who wishes to be a stenographer, on two

afternoons a week walks to Carver after the regular How

ard hours and spends the two hours from 3:30 to 5:30

P. M. in classes in typing and shorthand. These courses

she could take in the normal school day, ending at 3:00

P. M., if given at the main Howard building. All courses

at Claymont High School, including these two commercial

subjects, are given in one building and the travel back

and forth prevalent in the Howard arrangement and the

consumption of five extra hours per week would not occur

(BA. 159, ESA. 19). In addition, one afternoon a week,

after school, this plaintiff takes piano lessons.

An expert witness, a professor of psychology at Ohio

State University, who is also a clinical psychologist and

a consultant to the neuropsychiatric service of the Veterans

Administration, to the United States Public Health Service

and to many other institutions, public and private, testified

that such bus travel renders educational opportunity at

Howard inferior to that at Claymont, in that it “ increases

irritability as well as fatigue” and renders plaintiffs “ less

psychologically prepared for the learning processes which

the school hopes to induce” (EA. 131). Further, that the

time consumed in the greater bus travel diminishes an

important block of the children’s time, namely, that for

self-initiated activities, and thus also “ would be a detri

ment in the child’s over-all education” (EA. 133). This

testimony was uncontradicted and undisputed. That time

spent by students is “ a disadvantage” and would “ curtail

* * * opportunity” is stated also by the State Superintend

ent of Public Instruction (ESA. 31).

29

The Expert’s Survey

An expert in evaluating the educational programs of

secondary (i.e., high) schools testified as to his findings

on the basis of a comparative survey which he made of

the Claymont and Howard High Schools (IRA. 55-56). No

testimony indicated that a comparable study was made by

the defendants. Below is stated what the survey revealed.

Sites and Buildings

Claymont High School is located on a thirteen or four

teen-acre site, ornamented by shrubbery (RA. 59; RSA. 18),

has a football field, a quarter-mile track, girls’ hockey field

and playground equipment (RSA. 18). The main Howard

building is located on a three-and-one-half-acre site, flanked

on two sides by industrial buildings and by poor housing

on a third side. It has no playing fields of its own but

its students may use near-by public Kirkwood Park, which

has no football or hockey field or other regulation playing

fields (RSA. 6; RA. 166). The Carver building of Howard

is on a congested site, without land in front or play space

in the rear (RA. 60). In connection with the relative size

and adaptation of the sites, it is added that there was tes

timony, concurred in by defendants and plaintiffs, that

Claymont, in grades 1 to 12, inclusive, has an enrollment

of 800, of whom. 400 are high school pupils, and Howard en

rollment of 1,274, high school pupils only (RSA. 4-5, 16).

See also testimony of the Assistant Superintendent in

charge of secondary schools: “ Well, if I had a boy of

my own I would rather have him on a place where there is

a larger plot” (RSA. 26).

As to buildings, both the Claymont structure and the

Howard main building are good. No inference can be

drawn that one is better than the other, except that the

Howard auditorium, unlike Claymont’s, must frequently

be used for instruction of classes and to shelter home room

30

sections (ESA. 3). Howard’s gymnasium, unlike Clay-

mont’s, is inadequate, some physical education classes at

Howard being held in a private gymnasium three and a

half blocks away (ESA. 1, EA. 167). Also, Howard has some

instruction shops in a near-by annex reached by an out-door

passageway unprotected from the weather (EA. 59). What

is actually a third Howard building, Carver, is very old,

without auditorium or gymnasium and with a dingy base

ment room as a make-shift cafeteria, devoid of tables or

chairs. It has a single lavatory for boys with unsanitary

cement floors (EA. 59).

Teacher-Preparation and Load

A comparison of academic preparation of the teachers

at the two schools reveals that 37.73% of those at Howard

have master ’s degrees and 59% of the teachers at Claymont

have master’s degrees. At Howard, the lower bachelor’s

degree is held by 49% of the teachers and at Claymont

by 36%. At Howard, seven teachers, or 9.4%, have no

degree; at Claymont, one teacher, or 4.45%, appear,

according to plaintiffs’ witness, to be without a degree

(EA. 61). However, one of the defendants, the Superin

tendent of Schools at Claymont, who was the only witness

produced on this point by the defendants, testified that

59% of the teachers there have the master’s degree; 41%,

the bachelor’s and no teacher is without a degree (ESA. 17).

Howard has persons without any degree teaching academic

subjects, such as, English and mathematics, and physical

education, as well as vocational (i.e., trade) subjects (EA.

61), and also acting as librarian at Carver is a person not

trained as a librarian and with a degree from an unac

credited school (EA. 5). Claymont has no teacher without

a degree teaching academic subjects and perhaps none

without degree in vocational subjects (ESA. 17). Plain

tiffs’ and defendants’ witnesses agree that the formal train

ing of teachers, as measured by the attainment of academic

degrees, is an index of teacher preparation and proficiency

31

(BA. 62; BSA. 25, 26). And in direct examination, de

fendant, Dr. George B. Miller, Jr., State Superintendent

of Public Instruction, said: “ Now with regard to degrees,

of course we must admit that the possession of degrees

carries with it the assumption that the teacher is going

to be the better teacher. We can’t get out of that” (BSA

30). It appears that under State law and practice, teacher

salary is scaled, at least in part, upon the possession of

academic degrees, a salary higher by $200 being paid to

a holder of a master’s degree than to the holder of only

a bachelor’s (BSA. 17; BA. 175; BSA. 26; BSA. 31).

As to average class size at the Claymont and Howard

high schools, undisputed testimony of the expert stated the

comparative figures, showing in six instances substantial

disparities in favor of Claymont, as follows:

Claymont Howard

English 25.56 32.26

Foreign Languages 25.75 31.10

Home Economics 16.2 24.71

Industrial Arts 17.14 23.9

Mathematics 30.60 33.25

Natural Sciences 34.87 32.26

Physical Education 24.28 43.67

Social Studies 33.88 32.05

(BA. 62-63)

While these figures are as to average class size, the

uncontradicted evidence was that in some classes in Physi

cal Education at Howard the number of pupils was 55 and

in one, 88 (BA. 167), and that such numbers were “ so large

as to seriously jeopardize” the possibility of education in

that field (BA. 65). The optimum class size is conceded to

be twenty-five (BSA. 20). The evidence reveals no class

load situation at Claymont comparable to the extraordi

narily large classes at Howard.

32

In the above table, in the two instances in which average

class sizes at Claymont were greater than in similar courses

of study at Howard, the relative disparities are much

smaller than in any of the six groups of classes where

Howard class sizes exceed Claymont’s (RA. 64). The

expert in school evaluation testified that pupils in the

smaller classes have better educational opportunity, because

they can participate more and learn from participation and

because the teacher has more time to handle individual

differences of pupils and to prepare, to grade papers, and

to evaluate notebooks (RA. 64). Defense witnesses agreed

too that the “ teacher begins to feel overloaded in regard

to the services she can give pupils if it runs over 25” (RA.

177), although. other defense testimony deemed the differ

ences insubstantial (A. 272-276, 329-330, 302-306).

At Claymont the average teacher has a teaching load of

149 pupils per week; at Howard, the teaching* load carried

by the average teacher is 178 pupils per week (RA. 65).

Defendant Stahl, Superintendent of Schools at Claymont,

testified on cross-examination that at Claymont the average

teacher teaches between 140' and 150 pupils per wyeek and

that a teacher with such a teaching load would teach more

effectively than one teaching 178 pupils per week (RSA.

17-18, RA. 163).

Curricula and Extra-Curricular Activities

At Claymont, according to the evidence, seven academic

courses are offered which are not offered at Howard. These

include Public Speaking, Spanish, Trigonometry, Mathe

matics Review7, Sociology, Economics and Air Age, or World

Geography (RSA. 2-3, 13-14). That courses so designated

do not exist at Howard seems conceded. This is a factor

in evaluation, defendants’ testimony agreed (RA. 178-179).

But defendants says the following: Howard, with no public

speaking course, has a debating team as an extra-curricular

activity (RSA. 20); while both Spanish and French now are

33

the modem languages taught at Claymont and only French

at Howard (ESA. 20), Claymont is now in a transition back

to French alone (ESA. 13-14). As for the sociology and

economics courses which Claymont gives, Howard has a

course known as “ Problems in Democracy,” which defend

ants “ presume * * # would be very comparable” (ESA. 14)

or would embrace some of the content of a course in soci

ology (ESA. 21-22). Trigonometry also is taught to one

student at Howard in a class where others are being taught

intermediate algebra (ESA. 21). The mathematics review

at Claymont is an “ open air course, ’ ’ for students needing

review before going out to get a job, but principally for

students “ who are not willing to work hard enough to

master the other mathematical courses” (ESA. 15). How

ard also offers seven vocational courses not offered at

Claymont (ESA. 3).

With a school newspaper, a Leaders Corps, Art Club,

Mathematics Club, Drivers’ Club, Square Dance Club, and

Tumbling Girls, Claymont has wider pupil, or extra-cur

ricular activities than provided by the Story Hour Club,

Science Club, and French Club fostered at Howard (EA.

67-68; ESA. 16).

Miscellaneous Facts

Accreditation

Both Claymont and Howard are accredited by the

Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools of Middle

States and Maryland, which means that both schools have

met minimum requirements although there may be wide

discrepancies between the qualities of the schools con

cerned (A. 47).

Equipment

Both schools are well supplied and well equipped (A. 66).

34

Health Services

The Claymont School has a full-time nurse. The How

ard School has a nurse four-fifths of the time (A. 62). The

Howard School, along with all other high schools of the

city of Wilmington, shares in the services of a number of

psychologists, psychiatrists, dentists, physicians, hygien

ists, nurses (A. 150, 153). At the Claymont School, the

nurse inspects the children yearly and the doctor inspects

the children no more than once every other year (A. 185).

Library

The librarian at Howard has adequate training (A. 71).

The librarian at Carver holds a degree from a non-accred-

ited school (A. 71). The librarian at Claymont holds a

degree in Library Science (A. 72).

The copyrights and basic reference material at both

schools are very satisfactory. Howard High School has

the larger library (A. 72).

Guidance

There are two, full-time guidance teachers at Howard

(A. 196). There is a full-time guidance teacher at Clay

mont (A. 171). Howard High School shares in the citywide

guidance program of Wilmington (A. 150, 153).

Opinion Testimony on the Ilowurd-Claymont

Comparison

Having surveyed the two schools and placed in evidence

the comparative facts disclosed by his survey, the expert

in school evaluation testified also as to his opinion that the

educational opportunity offered at Claymont High School

was superior to that at Howard High School (RA. 66).

On the basis of this surveyor’s testimony as to the com

parative facts relating to the respective Claymont-Howard

school sites, buildings, teacher preparation, teacher load,

curriculum, and extra-curricular activities, and on the basis

35

of a hypothetical question embodying these facts, pro

fessionals specializing in the science of education, some

of them professors employed in the public college system

of the State of Delaware, placed in evidence their expert

opinions that Claymont offered superior eductional op

portunity to that offered by Howard (BA. 98-99, 133-137,

137-138, 143-144).

No contrary value judgments, or opinions, were offered

by the defendants to counterbalance the evidence put into

the record by these experts.

E d u ca tio n a l O p p o rtu n ity — H ockessin School

No. 107 vis-a-vis School No. 29

Expert’s Survey

A second expert (BA. 101-103) in evaluating the educa

tional facilities and programs of elementary schools testi

fied as to his findings on the basis of a comparative survey

which he made of Hockessin Schools No. 107 and No. 29.

No testimony indicated that a comparable study was made

by the defendants.

Sites and Buildings

School No. 29 is on a five-acre site (BA. 173), described

as “ extraordinary beautiful,” landscaped and having a

pine watershed, a multiflora rose border, bushes, trees

(BA. 107-108). On the playground are eight varieties of

play equipment, and marked off are a baseball diamond,

with benches and backstop, and separate courts for basket

ball, volleyball, and soccer (BA. 114). No. 107 is on a two-

acre sit (BA. 173), unenhanced since the school was con

structed, with no landscaping (BA. 107). It has three

varieties of play equipment, in part in need of repair, and

no diamond or courts as at No. 29 (BA. 114). The Assistant

State Superintendent of Education in charge of elementary

schools, a witness for defendants, stated that the play

36

ground at No. 29 is superior to No. 107’s. That size of site

(RA. 173; ESA. 26; RA. 178) specially prepared and

equipped playing fields (RA. 176) have significance in

comparing two schools to determine which is superior was

acknowledged by witnesses called by the defendants, as

well as by testimony for plaintiffs. That beauty has value

for the learning process also is concurred in by witnesses

called by the defendants (RSA. 19; RA. 174; RSA. 25;

RA. 178) and by plaintiffs (RA. 107-108).

School No. 29, constructed in 1932 (RA. 105), is a build

ing with four classrooms (RA. 103). Its original cost was

$55,438.83 (RA. 105). School No. 107, completed as a one-

room school in 1922, at a cost of $21,382.74, has a present

value of $13,100 (RA. 105). The appreciation in value of

No. 29 of 39%, and the depreciation of No. 107 of 39%,

reflect disparities between the two schools in improvement,

maintenance and upkeep (RA. 105-106). No. 107 became

a two-room school by the insertion of a sliding partition

(RA. 103).

No. 29 has a full-time custodian equipped with an electric

vacuum cleaner, power lawn mower, manual lawn mower,

besides brooms, mops, and pails. No. 107 has a part-time

custodian equipped only with brooms, brushes, mops, pails

and wastebaskets (RA. 106).

There are other differences: No. 29 has an auditorium;

No. 107 has none (RA. 111). No. 29 has an indoor basket

ball court which petitioners’ witness testified is no longer

in use (A. 215); No. 107 has none (RA. 111). No. 29 has a

partial basement, providing storage space and more ade

quate space for heating and hot water systems; No. 107

has none (RA. 111-112). No. 29 has several of the pro

fessionally accepted forms of drinking fountain; No. 107

does not have professionally acceptable drinking facilities

(RA. 112). No. 29 has sanitary toilet and lavatory facilities

in a large, well-ventilated, well-lighted room; No. 107 has

one commode in a closet-like, small room adjoining storage

space for children’s lunches, clothing, janitorial materials,

37

and the school’s drinking water bottles (RA. 112). No.

29 has a well-equipped nurse’s office; it also has a part-

time nurse, paid by the State (ESA. 22-23; RA. 172; RSA.

24). No. 107 has but a first-aid packet and no nurse (RA.

113). No. 29 has an electric refrigerator for the storage of

milk and has a milk program; No. 107 has neither (RA. 112-

113). For protection against the hazard of fire, No. 29

has seven fire extinguishers and five exits; No. 107 has three

fire extinguishers, its one main exit and another through

its furnace room (RA. 121).

On the Strayer-Englehart score card, an index developed

and employed by educators to evaluate the physical condi

tion of a school plant (RA. 114-115, 185-188), School No.

29 scored 594 out of a possible 644 points; School No. 107,

281 out of the same possible point score (RA. 115).

Instructional Materials and Accessories

No. 29 has 779 library books of separate title; No. 107

has a library of 394 books of separate title (RA. 116-117).

No. 29 has a globe in each of its four classrooms; No. 107

has one globe for its two classrooms (RA. 117). No. 29

has a victrola in each classroom; No. 107 has one victrola

(RA. 117). No. 29 has a film library for film strips,

“ catalogued and rather complete’’; No. 107 has but several

film strips (RA. 117). The State Superintendent of Public

Instruction stated that the availability of instruction ma

terials is a factor in comparing two schools (RA. 177-178).

As to some of the disparities in playground, site, drink

ing fountains, physical education and recreation equipment,

milk program and institutional equipment, petitioners pro

duced exhibits and testimony which sought to show that

the property was given to the State by the Parents-Teachers

Association (A. 215-217, 229-230).

38

Relative Expenditures for Schools 29 and 107

For 1949-1950, the latest year for which the information

was available, the total expenditure of $18,170.73 for No.

29, and $5,489.52 for No. 107 (RA. 110), when itemized,

revealed the following differences:

Administrative Control

Instructional Services

Operation of Plant

Maintenance ................

Promotion of Health .

Capital Outlay ...........

Library Books ...........

No . 29 No. 107

$ 72.06 Nothing

12,805.47 $4,663.70

2,942.92 540.78

135.78 301.24

317.74 Nothing

1,731.30 149.26

119.37 34.52

Total for educational purposes $18,170.73 $5,489.52

(RA. 109-110).

When these expenditures are translated in terms of the

number of pupils in each school, on the basis of average

daily attendance, the expenditure per pupil in No. 29 was

$178.13; in No. 107, $137.22 (RA. 110). There was spent on

the education of each child in No. 107 only 77% of the

amount spent on each child in No. 29 (RA. 110-111).

Teacher Preparation, Rating and Load

In School No. 29, two teachers have both the Bachelor

of Arts and Master of Arts degrees, and the remaining

two have no degree, although one of the latter would re

ceive her Bachelor of Arts degree in elementary education

at the end of the then current semester (i.e., in January,

1952) (RA. 118; RSA. 6). At No. 107, one teacher had the

Bachelor of Arts degree; the other teacher had no degree.

The additional training possessed by teachers with Mas

ter’s degrees is awarded higher pay by the State (RSA. 17;

RA. 175; RSA. 25, 30, RA. 178) and, according to the testi

mony of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction,

carries the assumption of better teaching (RSA. 30).

39

The same Comity Supervisor has rated all teachers in

both schools; all four in No. 29 are rated “ A ” teachers;

both, in No. 107, are rated “ B ” teachers. The “ A ” rating

is given teachers who are superior in classroom presenta

tion, skill, techniques in accomplishing aims, progress made

by the class, scholarship, professional growth and definite

ness of aim. “ B ” teachers, rated on the same criteria, do

not achieve in so high a degree (BA. 118-119). The Assist

ant State Superintendent for elementary schools and the

State Superintendent testified that “ A” teachers are

superior to “ B ” teachers (BA. 174-175, 181).

Because in No. 29 each teacher is required to allot her

instructional time between two grades in a classroom, and

in No. 107 a teacher makes similar allotment among three

grades in a classroom, a pupil in No. 107 can receive but

60 days of individual attention for his grade level; where

as, a pupil in No. 29 receives 90 days per school year. A

teacher at No. 29 can give 50% of her school day to each of

her two grades; a teacher at No. 107, but 33%% to each of

her three grades (BA. 116). State testimony recognizes that

teaching load is a significant factor in school comparisons

(ERA. 176).

Achievement Tests

In achievement tests, pupils in No. 29 surpass pupils in

No. 107. This, at least partially, can be attributed to the

disparity in physical plant, instructional and recreational

equipment, teacher training and skills, and opportunity for

teacher attention (BA. 118-120). That it is not attributable

to any innate differences in capacity determined by race,

has been established by scientific research, as testified to by

an authority in intelligence measurement, Dr. Otto Kline-

berg, of Columbia University (RA. 122). No contradiction

was offered to this testimony, nor any attempt made to

weaken it by cross-examination, which was waived.

40

Travel

Bus transportation is afforded to No. 29 for pupils sit

uated similarly to infant plaintiff. Neither bus transporta

tion nor its equivalent is furnished to No. 107 (BA. 51-55).

Opinion Testimony on the No. 107 No. 29 Comparison

Having comparatively surveyed Hockessin Schools No.

29 and No. 107, the professional educator who made the

survey testified “ that there is no evidence of equality in

the educational facilities afforded in the two schools” , and

that No. 29 affords facilities “ far superior” to those af

forded by No. 107 (BA. 120-121).

Other professional educators placed in the record their

separate opinions, based on the facts in evidence, that

School No. 29 offered educational opportunity superior to

that offered by School No. 107 (BA. 98-99,, 133-137,143-144).

No opposing expert opinion was offered by the defendant,

although the Assistant State Superintendent in charge of

elementary schools, including the two schools being com