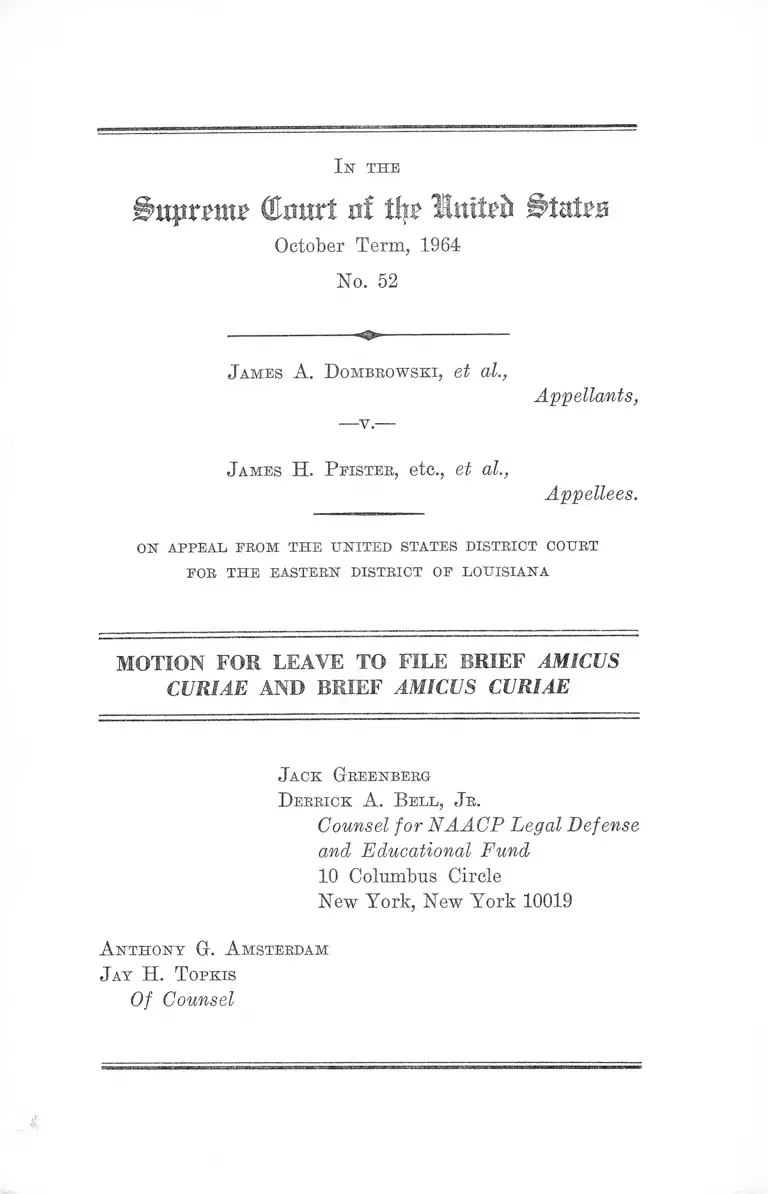

Dombrowski v. Pfister Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dombrowski v. Pfister Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1964. 98e5fb0c-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a5c0a5c6-01e9-4f6c-91e2-97145aeb5a5c/dombrowski-v-pfister-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I jST t h e

#tt$iraa» (Entttt rtf tli? Imteh &Ut?B

October Term, 1964

No. 52

J ames A . D om brow ski, et al.,

■— v . —

Appellants,

J am es H. P eister, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

ON A PPE A L PRO M T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTR IC T COURT

EOR T H E EA STE R N D IST R IC T OP L O U ISIA N A

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE AND BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

J ack G reenberg

D errick A. B ell , Jr.

Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

J ay H . T opkis

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Motion For Leave To File Brief Amicus Curiae........... 1

Brief Amicus Curiae .......................................................... 7

Co n c l u s io n .......................................................... .......................... 18

T able of Cases

Areeneaux v. Louisiana, 376 U. S. 336 (1964) ............... 11

Arkansas ex rel. Bennett v. NAAC.P Legal Defense

Fund, No. 45183 (Cir. Ct., Pulaski County) ........... 6

Arkansas ex rel. Bennett v. NAACP Legal Defense

Fund, No. 44679 (Cir. Ct., Pulaski County) ........... 5-6

Ashton Bryan Jones v. State of Georgia, No. 506, Octo

ber Term, 1964, see certified transcript, pp. 45-84 .... 5

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964) ...................9,11,16

Baines v. Danville, 4th Cir., Nos. 9080-9084, 9149-9150,

9212, decided August 10, 1964 ....................................... 10

Barr v. Columbia, 378 U. S. 146 (1964) ...................... . 11

Browder v. Gayle, D. C. M. D. Ala., 142 F. Supp.

707, affirmed 1956, 352 U. S. 903 (1956) ....................... 7

Brown v. Allen, 344 U. S. 443 (1953) ............................... 14

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 194 F. Supp.

182 (E. D. La., 1961) .................................................. 7

City of Tallahassee v. Patricia Due, No. 18863— Chan

cery Cir. Ct., Tallahassee, Florida ......... ................... 5

Cleary v. Bolger, 371 U. S. 392 (1963) ........................... 9

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319 IT. S. 157 (1943) ..7, 8, 9,

11,15,16,17,18

Dresner v. Tallahassee, 375 U. S. 136 (1963)------ U. S.

------ , 84 S. Ct. 1895 (1964)

PAGE

11

11

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229, p. 20 (1963) 10

England v. Louisiana State Board of Medical Ex

PAGE

aminers, 375 U. S. 411, 416-417 (1964) ................... 16,17

Ex Parte Royall, 117 LT. S. 254 (1886) ........................... 9

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 (1963) ................................... 14

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, p. 20 (1951) ........... 11

Fields y . South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 (1963) ............... 10

Hunter v. Wood, 209 U. S. 205 (1908) ........................... 9

In re Loney, 134 U. S. 372 (1890) ..... 9

In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1 (1890) .................................. 9,13

In The Matter of R. Jess Brown, Civ. No. 3382 (S. D.

Miss. 1963), appeal pending (5th Cir. No. 21224) .... 4

Lefton v. Hattiesburg, 333 F. 2d 280, 286 (1964) ........... 10

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 509 (1946) ............... 8

Matter of S. W. Tucker, Circuit Court Greenville

County, Virginia, February 15, 1962. Case filed as

“ ended Law case #407” .............................................. 4

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 (1963) 15

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961) ...........................12,15

Murdock v. Penn., 319 U. S. 105 (1943) ........................... 7

N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 433 (1963) ....5,10,11

NAACP v. Committee on Offenses Against Adminis

tration of Justice, 201 Va. 890, 114 S. E. 2d 721

(1963) ................................................................................ 5

NAACP Legal Defense Fund v. Gray, Civ. No. 2436

(E. D. Va.) ...................................................................... 6

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254, 269-270

(1964) 8

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319, 326-27 (1937) ....... 8

People v. McLeod, 25 Wend. 482 (Sup. Ct. N. Y. 1841) 13

Pea y. United States, 350 U. S. 214 (1956) ................... 9

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513, 525 ........................... 16

Stefanelli v. Miiiard, 342 U. S. 117 (1951) ................... 9

Texas v. NAACP, District Court No. 56-649, 7th Judi

cial District, Smith County, Texas, May 8, 1957 .... 5

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963) ....... ........... 14,16,17

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 (1879) ........................... 9

United States v. Harpole, 263 P. 2d 71, 82 (1959) ....... 3

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, 533 (1963) ............... 18

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) ....................... 11

Constitutional P rovisions and S tatutes

28 U. S. C. §§1331, 1441 (1958) ..................................... 15

28 U. S. C. §1343 (1958) ................................................ 11,15

28 U. S. C. §2241(c) (3) (1958) ....................................... 14

28 U. S. C. §2283 (1958) .................................................. 8

Act of February 13, 1801, Ch. 4, §11, 2 Stat. 89, 92 re

pealed by the Act of March 8, 1802, Ch. 8, 2 Stat. 132 12

Aet of March 8, 1802, ch. 8, 2 Stat. 132 ....................... 12

Act of February 4, 1815, ch. 31, §8, 3 Stat. 195, 198 .... 13

Act of March 3, 1815, ch. 43, §6, 3 Stat. 231, 233 ........... 13

Act of August 29, 1842, ch. 257, 5 Stat. 539 ................... 13

Act of March 3, 1863, ch. 81, §5, 12 Stat. 755-756 ....... 13

Act of March 7,1864, ch. 20, §9,13 Stat. 14 ,17 .......... 13

Ill

PAGE

IV

page

Act of June 30, 1864, eh. 173, §50, 13 Stat. 223, 241 .... 13

Act of April 9, 1866, Ch. 31, §3, 14 Stat. 2 7 ................... 14

Act of May 11, 1866, ch. 80, 14 Stat. 46 ....................... 13

Act of July 13, 1866, ch. 184, §§67-68, 14 Stat. 98, 171,

172 ...................................................................................... 13

Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 27-28, 14 Stat. 385 ...........13,14

Act of May 31, 1870, Ch. 114, §§8, 18, 16 Stat. 140, 142,

144 ...................................................................................... 14

Act of April 20,1871, Ch. 22, §1,17 Stat. 1 3 ................... 14

Act of March 1, 1875, Ch. 114, §3, 18 Stat. 335, 336 .... 14

First Judiciary Act of September 24, 1789, Ch. 20, 1

Stat. 73, 81-82 ................................................................. 12,13

Force Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §§3, 7, 4 Stat. 632,

633, 634 .............................................................................. 13

Judiciary Act of March 3, 1875, ch. 137, 18 Stat. 470 .... 14

Ku Klux Act of April 20, 1871, Ch. 22, 17 Stat. 13 ....12,15

Eev. Stat. §1979, 42 U. S. C. §1983 (1958) ...............11,15

United States Constitution, Art. I ll , §1 ......................... 12

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment,

§5 12

V

Oth er A uthorities

page

Bail in the United States: 1964, A Report to the Na

tional Conference on Bail and Criminal Justice (May

27-29, 1964) ...................................................................... 10

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1834 (4/7/66) ....... 13

Dunning, Essays on the Civil War and Reconstruction,

147, 156-163 (1898) ..................................... 13

Frankfurter & Landis, The Business of the Supreme

Court 64-65 (1928) ........................................................ 14

Hart & Wechsler, The Federal Courts and the Federal

System 727 (1954) ........................................................ 12

Harvard Law Record, March 7,1963, p. 1 ....................... 4

Morgan, A Time to Speak (Harper & Row: New York,

N. Y., 1964) ............................... - .................................... 5

1 Morison & Commager, Growth of the American Re

public 426-429, 475-485 (4th ed. 1950) ....................... 13

N. Y. Times, July 4, 1963, p. 38, c. 1 ............................... 4

N. Y. Times, June 28, 1964, p. 46, c. 1, 2 ....................... 2

Resolution, Board of Bar Commissioners of the Missis

sippi State Bar, July 15, 1964 ................................... 3

United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1963 Re

port, 117-9.......................................................................... 3

Wechsler, Federal Jurisdiction and the Revision of the

Judicial Code, 13 Law & Contemp. Prob. 216, 230

(1948) ................................................................................ 15

I n t h e

§>npxmx (tart nt % Inttd* Stairs

October Term, 1964

No. 52

J ames A. D om brow ski, et al.,

Appellants,

J am es H. P eistee, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPE A L EEOM T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E EASTERN DISTRICT OF L O U ISIA N A

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AMICUS CURIAE

Petitioner, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., respectfully moves this Court for permission to file

the attached brief amicus curiae for the following reasons:

This case presents the issue of whether the civil rights

decisions of this Court and the civil rights legislation

enacted by the Congress may be deprived of significance

by attacks on their advocates.

According to the record here, the plaintiffs-intervenors

are two lawyers practicing in New Orleans; they have been

active in civil rights cases, representing Negroes in de

segregation cases and other litigation asserting rights con

ferred by the Constitution.

Acting on a search warrant issued under color of certain

Louisiana statutes, city and state police conducted a search

2

at gun point of the law offices of the plaintiffs-intervenors.

The police inspected all of the lawyers’ confidential legal

files and seized and took away some of them.

The purpose of this search, according to plaintiffs-in

tervenors, was to destroy their work in the field of civil

rights. Anticipating further action under color of the same

statutes, plaintiffs-intervenors asked the Court below for

injunctive relief and for a declaration that the statutes are

unconstitutional on their face and as applied. The requested

relief was refused without a hearing.

Thus, according to the decision below, an unconstitutional

statute may be used to destroy the work of lawyers en

gaged in civil rights cases, and the federal courts will with

hold relief.

The interest of petitioner NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund in any such ruling is, we suggest, mani

fest. Petitioner is a New York corporation organized for

the purpose, among others, of securing equality before the

law, without regard to race, for all citizens. For many

years, we have been the principal organization regularly

supplying the legal services to Negro citizens who claim

that they have been denied equal protection of the laws,

due process of law and other rights secured by the consti

tution and laws of the United States. N. Y. Times, June

28, 1964, p. 46, c. 1, 2.

While we have no connection with the plaintiffs-inter

venors in this case, and have not worked with them in the

past, if the files of our legal staff and our cooperating

attorneys may be subjected to the same lawless invasion

as is here alleged to have occurred, without relief being

available in the federal courts, our activities and, indeed,

the cause of civil rights will be most severely prejudiced.

3

The problem would perhaps be of lesser consequence

were a plethora of advocates available to represent civil

rights causes. But the precise opposite is true. According

to a survey conducted by the United States Commission on

Civil Bights, 1963 Report, 117-9, only a small segment of

the Southern bar handles civil rights issues. And from

our own experience we know that, until 1961, only one

lawyer in Mississippi handled civil rights litigation, and

even today there are only three. Only this summer has the

Mississippi Bar Association adopted a resolution asserting

the duty of its members to appear in civil rights cases.1

But results from this resolution are yet to be made clear

and there is no reason to believe that there will soon be a

drastic change.

In part, this dearth of counsel is doubtless due to the

social pressures which are brought to bear on advocates of

civil rights causes. One-third of the lawyers who reported

to the Commission on Civil Rights that they had handled

civil rights cases reported also that they had suffered

threats of physical violence, loss of clients, or social os

tracism as a result. Ibid. The Fifth Circuit, in United

States v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d 71, 82 (1959) noted that lawyers

who “ fight against the systematic exclusion of Negroes

from juries sometimes do so at the risk of personal sacrifice

which may extend to loss of practice and social ostracism.”

The present case and similar instances demonstrate that

the pressures are not merely business or social: in many

areas, civil rights advocates face governmental and judicial

action which has no parallel in the experience of counsel

who do not appear in civil rights causes. Among the more

disquieting examples are:

1 Resolution, Board of Bar Commissioners of the Mississippi

State Bar, July 15, 1964.

4

1. Disbarment proceedings were begun in 1959 against

S. W. Tucker, Esq., a Negro member of the Virginia bar,

on charges that, in 1950 and 1952, he appeared in three

cases at the behest of the NAACP. Only after a year of

litigation were the charges dismissed. Matter of S. W.

Tucker, Circuit Court, G-reensville County, Virginia. Feb.

15, 1962. Case filed as “ ended Law case #407” .

2. Disciplinary proceedings were begun against R. Jess

Brown, Esq., a Negro member of the Mississippi bar, on

the grounds that, in a school desegregation case, he had

appeared for one of 13 plaintiffs without authority and had

inserted an unfounded allegation in the complaint. After

a hearing which demonstrated that Mr. Brown’s appear

ance was authorized and the allegation was not groundless,2

the citation was discharged, but costs were taxed against

Mr. Brown on the apparent ground that he had demon

strated his innocence only at the hearing. In the Matter of

R. Jess Brown, Civ. No. 3382 (S. D. Miss. 1963), appeal

pending (5th Cir., No. 21224). Mr. Brown is the Mississippi

attorney earlier mentioned who has handled civil rights

cases since before 1961. Cf. Harvard Law Record, March

7,1963, p. 1; N. Y. Times, July 4,1963, p. 38, c. 1. concerning

the disbarment of a white Mississippi attorney who repre

sented Episcopalian ministers involved in the Jackson Free

dom Rides.

2 The unfounded allegation was that shots had been fired into

the home of a named plaintiff. In point of fact, however, shots were

fired into a cafe owned by that plaintiff, into the homes of at least

six of her neighbors, and into her brother’s home. In the Matter of

B. Jess Brown, Record on Appeal, pp. 96-97, 225-9; Supplemental

Record 338, 370.

5

3. Tobias Simon, Esq., appeared for the Florida Civil

Liberties Union in eases involving hundreds of civil rights

demonstrators. He has appeared also in this Court in civil

rights cases. In a local Tallahassee court, he was charged

with contempt for having failed to appear on behalf of a

young girl arrested in a civil rights demonstration. Follow

ing the efforts of his counsel, Florida’s former governor,

Fuller Warren, Esq., the charges were ultimately dismissed.

City of Tallahassee v. Patricia Due, No. 18863— Chancery,

Cir. Ct., Tallahassee, Fla.

4. Howard Moore, Jr. and Donald L. Hollowed, of the

Georgia bar, were recently ordered to show cause why

they should not be held in contempt of court because of a

motion which they filed to recuse Judge Durwood T. Pye

on the grounds of bias and prejudice. The contempt citation

followed the denial of the motion by Judge Pye, who de

scribed the very presentation of the motion as an insult to

the court. The hearing on the order to show cause has

been continued. Cf. Ashton Bryan Jones v. State of Geor

gia, No. 506, October Term, 1964, see certified transcript,

pp. 45-84.

5. Charles Morgan, Jr., a successful practicing Bir

mingham attorney, was forced to leave Alabama after

speaking out against the bombing of a Negro church where

four Negro Sunday School children were killed. His ex

perience is detailed in: A Time to Speak (Harper & Row,

New York, N. Y., 1964).

Among actions taken against civil rights. organizations

operating in the courts, see NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S.

415 (1963); NAACP v. Committee on Offenses Against

Administration of Justice, 201 Va. 890, 114 S. E. 2d 721

(1963); Texas v. NAACP, District Court No. 56-649, 7th

Judicial District, Smith County, Texas, May 8, 1957;

Arkansas ex rel. Bennett v. NAACP Legal Defense Fund,

6

No. 44679 (Cir. Ct., Pulaski County); Arkansas ex rel.

Bennett v. NAACP Legal Defense Fund, No. 45183 (Cir.

Ct., Pulaski County); NAACP Legal Defense Fund v.

Gray, Civ. No. 2436 (E. D. Va.).

The courts can, of course, do little about the social and

economic pressures which operate against counsel in civil

rights matters. All the more reason then, we respectfully

suggest, for speedy judicial intervention in behalf of those

counsel who suffer from official action.

Because of the broad significance of this case, which may

not adequately appear in argument on behalf of the parties,

we respectfully submit that the views of petitioner may be

of interest to the Court.

We have asked permission of the parties to file this brief

amicus curiae; counsel for appellees refused.

W herefore petitioner prays that the attached brief

amicus curiae be permitted to be filed with this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

D errick A. B e ll , J r .

Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

J ay H. T opkis

Of Counsel

I n th e

f&tpran* (£mxt of % Inlfoft BMm

October Term, 1964

No. 52

J ames A. D om brow ski, et al.,

Appellants,

J ames H. P fister, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

ON A PPE A L FRO M T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E EASTERN DISTRICT OF L O U ISIA N A

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

This brief speaks only to the question whether the doc

trine which Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157 (1943),

broadly and unnecessarily1 announced should now be disap

proved. The jurisdiction, in a strict sense, of the three-

judge federal district court below to enjoin the enforce

ment of state criminal statutes found, on their face or as

administered, to violate the Fourteenth Amendment civil

rights of the plaintiffs is clear beyond cavil,2 and the in

1 Douglas v. Jeannette might have been disposed of simply on

the ground put forth in 319 U. S. at 165, that the ordinance sought

to be enjoined was that very day declared unconstitutional in

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105 (1943), and nothing in

the record suggested that the threat of its enforcement endured

a decision of the Supreme Court striking it down.

2 The Jeannette case itself so says, 319 U. S. at 162; and see

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 194 F. Supp. 182 (E. D.

La. 1961) (3-judge court), aff’d per curiam, 368 U. S. 11 (1961);

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala, 1956) (3-judge

court), aff’d per curiam, 352 U. S. 903 (1956).

8

applicability of the statutory bar of 28 U. S. C. § 2283

(1958) evident.3 Nevertheless, language in Jeannette does

support the refusal of a federal court to enjoin prosecution

under even a state statute which infringes the “ supremely

precious” 4 freedoms of the First Amendment, and the rele

gation of those freedoms to the “ remedy” of state prosecu

tion and appeal.5 It is the contention of this amicus that

such refusal is impermissible, and that federal equity should

entertain injunctive challenges to state criminal statutes

claimed invalid under the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments, quite without regard to whether a plaintiff under

takes (as the present plaintiffs did) the onerous evidentiary

burden of showing that defendant state officials are conspir

ing to deprive the plaintiff of his federal constitutional

rights.

Amicus recognizes at the outset that this issue is not

easily resolved. There are weighty justifications for this

Court’s reluctance, manifest in several forms, to permit the

federal courts’ involvement in state criminal prosecutions

until those prosecutions have finally come to rest in the

state courts. Abstention pending state court litigation

avoids potentially unnecessary federal constitutional deci

sion, acknowledges state legitimate concern for the expedi

tious administration of state criminal law, and declines to

3 See Judge Wisdom’s dissenting opinion below.

4 A. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 433 (1963). Cf. Po.lko

v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319, 326-327 (1937); Marsh v. Alabama,

326 U. S. 501, 509 (1946), and authorities cited; New York Times

Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254, 269-270 (1964), and authorities cited.

5 Of course, even the language of Jeannette does not support the

result below. The premise of Jeannette is that “No person is im

mune from prosecution in good faith for his alleged criminal acts.”

319 U. S. at 163. Plaintiffs here allege bad faith prosecution. This

amicus does not press the issue of bad faith, however; bad faith

being a virtually impossible matter to prove in many cases where

in fact it exists, the amicus seeks a broader ground of federal equity.

9

make available collateral sniping devices susceptible of

abuse to disrupt orderly state court proceedings. Cf. Vir

ginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 (1879) (limiting civil rights

removal statute to exclude cases where removal is sought

by reason of speculative claims of federal constitutional

violation at future state tria l); Ex parte Royall, 117 U. S.

254 (1886) (authorizing discretionary denial of federal ha

beas corpus to try in advance of state criminal trial issues

fairly triable in the state prosecution) ; Stefanelli v. Minard,

342 U. S. 117 (1951), and Cleary v. Bolger, 371 XL S. 392

(1963) (disallowing federal suppression of evidence to be

offered at state criminal trial). As the cited cases reflect,,

the seriousness of potential disruption of state processes

by federal court anticipatory action is greatest where—

unlike the present case—state prosecutions have once been

begun and are actually underway. And, of course, none of

the doctrines of federal judicial abstention are so steel-

clad as not to admit of exceptions where particularly sensi

tive federal interests are implicated. See, e.g., the excep

tion to Royall recognized in In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1

(1890); In re Loney, 134 U. S. 372 (1890); Hunter v. Wood,

209 U. S. 205 (1908); the exception to Stefanelli recognized

in Rea v. United States, 350 U. S. 214 (1956); cf. Baggett

v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964), infra.

Weighing against the considerations which favor federal

abstention where the state criminal process touches fed

erally protected freedoms of expression are certain hard

realities. Consider the consequences of a federal district

court’s refusal, on Jeannette grounds, to enjoin a state

statute which criminally punishes First Amendment pro

tected conduct:

(1) Persons exercising First Amendment freedoms will

be arrested for prosecution. The arrests may cost them

their jobs or such benefits as unemployment compensation.

10

See, e.g., Baines v, Danville, 4th Cir., Nos. 9080-9084, 9149-

9150, 9212, decided August 10, 1964. In order to obtain

their release from jail pending trial, they will have to make

bail in amounts and forms which the reporters of B ail in

t h e U nited S tates : 1964, A R eport to t h e N ational

C onference on B ail and Crim in al J ustice (May 27-29,

1964) found are frequently set in civil rights cases “ as pun

ishment or to deter continued [civil rights activity]. . . . ”

Id. at 53. Professional bonds will often be the only prac

ticable way to make bail; once paid, the premiums are

irrecoverably lost to the defendants, whatever the outcome

of the prosecution.

(2) The cases will come to criminal trial in a state court.

As this Court knows, see e.g., Edwards v. South Carolina,

372 U. S. 229 (1963); Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S.

44 (1963), statutes repressive of free expression lend them

selves to mass prosecutions, mass trials. The burden of

conducting a defense in such trials is indescribable. Apart

from the obvious problem that legal manpower willing to

undertake the defense is least available in areas where it

is most needed, see N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415,

443 (1963); Lefton v. Hattiesburg, 333 F. 2d 280, 286 (1964),

the protection of an individual defendant’s interests in such

trials is next to impossible. Following trial and conviction,

state appeals will be taken. Appeal or appearance bonds

will be required, unless forma pauperis procedure is em

ployed. Realistically, forma pauperis procedure is that in

name only, for the cost in fees and time of securing the

required notarized pauper’s oaths for several hundred de

fendants is itself considerable.

(3) The defendants will attempt to preserve their federal

claims as they run the gauntlet of state appellate proce

dure. Some will succeed, with assistance from this Court,

11

e.g., Wriglit v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963); Barr v.

Columbia, 378 U. S. 146 (1964). Others w ill'fail, e.g.,

Arceneaux v. Louisiana, 376 U. S. 336 (1964); Dresner v.

Tallahassee, 375 U. S. 136 (1963);------ U. S .------- , 84 S. Ct.

1895 (1964).

(4) Those who preserve their federal claims on the

merits will ask this Court to review their convictions on

records in which all testimonial conflicts have been resolved

by state judges or juries. Unfavorable findings of fact will

lose federal constitutional rights. E.g., Feiner v. New York,

340 U. S. 315 (1951).

(5) With so many vicissitudes and contingencies of liti

gation standing as potential obstacles to the ultimate vin

dication of their federal claims, many persons will simply

forego the exercise of their constitutional rights of free

expression rather than run the risk of prosecution. See

N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 432-438 (1963);

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360, 375-379 (1964). And this

repression of free expression will be unequal in its effect,

for the discretion of the prosecuting agencies and the ex

pectable hostility of state courts and juries will weigh with

particular force upon the proponents of unpopular causes.

These being the facts which this Court’s own experience

has exposed, does the doctrine of Douglas v. Jeannette,

remitting to state prosecution plaintiffs who invoke the fed

eral civil rights injunctive jurisdiction given by 28 U. S. C.

§1343 (1958) and Eev. Stat. § 1979, 42 U. S. C. §1983

(1958) to challenge state criminal statutes under the First

and Fourteenth Amendments, strike a balance consistent

with the appropriate relations between state and national

courts? The question is in the first instance one of con

struction of the jurisdictional statutes, for (subject to con

stitutional restrictions not arguably involved here) Con

12

gress is given by the Constitution the primary responsi

bility in designing the shape of our federalism—particu

larly as regards the effect of the Fourteenth Amendment,

II. S. Const., A m en d . XIY, § 5— and in defining the role

of the federal courts in effectuating its goals, TJ. S. C onst .,

A r t . I ll , § 1.

The plaintiffs here seek relief under statutes originating

in the first section of the Ku Klux Act of April 20, 1871,

ch. 22, 17 Stat. 13, an enactment which this Court has found

was intended “ to afford a federal right in federal courts

because, by reason of prejudice, passion, neglect, intol

erance or otherwise, state laws might not be enforced and

the claims of citizens to the enjoyment of rights, privileges,

and immunities guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

might be denied by the state agencies.” Monroe v. Pape,

365 U. S. 167, 180 (1961). In addition to the 1871 legisla

tive background carefully canvassed in Monroe v. Pape, the

larger sweep of history is instructive. During three quar

ters of a century following the First Judiciary Act of Sep

tember 24, 1789, ch. 20, 1 Stat. 73, Congress acted substan

tially on the principle “ that private litigants must look to

the state tribunals in the first instance for vindication of

federal claims, subject to limited review by the United

States Supreme Court.” H art & W echsler , T he F ederal

C ourts and th e F ederal S ystem 727 (1954). It was not

then supposed that the necessary and proper place for the

trial litigation of all issues of federal law wras in the lower

federal courts, and no general federal question jurisdiction

wras given those courts.6 Particularly were the lower fed

eral courts excluded from involvement in the state crim

6 Save in the federalist Act of February 13, 1801, ch. 4, § 11,

2 Stat. 89, 92, repealed by the Act of March 8, 1802, ch. 8, 2 Stat.

132.

13

inal process,7 although from time to time limited incursions

were authorized in classes of cases where there was more

than ordinary reason to distrust the state judicial insti

tutions.8 With the advent of the Civil War, Congress mul

tiplied the incursions,9 and subsequently the Reconstruction

commanders, familiar with the temper of the state courts,

withdrew from those courts civil and criminal jurisdiction

over cases involving Union soldiers and freedmen, and gave

the jurisdiction to national military tribunals.10

7 See particularly § 14 of the Judiciary Act of September 24,

1789, ch. 20, 1 Stat. 73, 81-82, excepting state prisoners from the

federal habeas corpus jurisdiction.

8 In the face of New England’s resistance to the War of 1812,

see 1 Morison & Commager, Growth of the A merican Republic

426-429 (4th ed. 1950), federal removal jurisdiction was extended

to civil and criminal cases involving federal customs officials in

1815. Act of February 4, 1815, ch. 31, § 8, 3 Stat. 195, 198; Act

of March 3, 1815, ch. 43, § 6, 3 Stat. 231, 233. South Carolina’s

resistance to the tariff in 1833, see 1 Morison & Commagee, supra,

475-485, evoked the Force Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 57, §§ 3, 7,

4 Stat. 632, 633, 634, creating civil and criminal removal juris

diction for cases involving federal revenue officers and habeas

corpus jurisdiction to discharge all persons confined for acts done

under federal authority. McLeod’s case (People v. McLeod, 25

Wend. 482 (Sup. Ct. N. Y. 1841)) gave rise to the habeas corpus

extension of the Act of August 29, 1842, ch. 257, 5 Stat. 539.

See In re Neagle, 135 U. S. 1, 71-72 (1890).

9 The removal provisions of the 1833 act, note 8 supra were ex

tended to cover eases involving internal revenue collection. Act

of March 7, 1864, ch. 20, § 9, 13 Stat. 14, 17; Act of June 30, 1864,

ch. 173, § 50, 13 Stat. 223, 241; Act of July 13, 1866, ch. 184,

§§ 67-68, 14 Stat. 98, 171, 172. Further, the Act of March 3, 1863,

ch. 81, § 5, 12 Stat. 755, 756, authorized removal of civil and

criminal cases brought in the state courts against persons for acts

done during the rebellion under color of authority derived from

presidential order or act of Congress. Procedures under the 1863

act were improved by the Act of May 11, 1866, ch. 80, 14 Stat.

46, and the Act of February 5, 1867, ch. 27, 14 Stat. 385.

10 See Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1834 (4 /7 /66 ); Dun

ning, E ssays on the Civil W ae and Reconstruction 147, 156-163

(1898).

14

The War radically altered the view which the national

legislature had previously taken, that generally the state

legislatures, courts and executive officials were the sufficient

protectors of the rights of the American people. The Thir

teenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments wrote into

the Constitution broad new guarantees of liberty and equal

ity in which the federal government committed itself to

protect the individual against the States. The four major

civil rights acts undertook to elaborate and effectively es

tablish the new liberties and, significantly, each of the acts

contained jurisdictional provisions making the federal

courts the front line of federal protection.11 No longer was

it assumed that the state courts were the normal place for

the enforcement of federal law save in the rare and narrow

cases where they affirmatively demonstrated themselves

unfit or unfair. Now the federal courts were seen as the

needed organs, the ordinary and natural agencies, for the

administration of federal rights. F ran k fu rter & L andis,

T he B usiness op th e S uprem e C ourt 64-65 (1928). This

is apparent in the enactment of the Act of February 5, 1867,

ch. 28, 14 Stat. 385, the federal habeas corpus statute now

found in 28 U. S. C. § 2241(c) (3) (1958), which assured

that every state criminal defendant having a federal de

fensive claim would have a federal trial forum for the liti

gation of the facts underlying that claim. See Brown v.

Allen, 344 U. S. 443 (1953); Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391

(1963); Townsend v. Sam, 372 U. S. 293 (1963). It is ap

parent in the Judiciary Act of March 3, 1875, ch. 137, 18

Stat. 470, which created general federal question jurisdic

tion in original and removed civil actions and thus wrote

permanently into national law the provision of a federal

11 Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, § 3, 14 Stat. 27; Act of May 31,

1870, ch. 114, §§ 8, 18, 16 Stat. 140, 142, 144; Act of April 20,

1871, ch. 22, § 1, 17 Stat. 13; Act of March 1, 1875, ch. 114, § 3,

18 Stat. 335, 336.

15

trial court for every civil litigant engaged in a significant

controversy based on a claim arising under the federal

Constitution and laws. See 28 U. S. C. §§ 1331, 1441 (1958).

Particularly, in view of the Reconstruction Congress’ over

riding concern for the effective enforcement of civil rights,

it is manifest in the supervening federal trial jurisdiction

created by § 1 of the Ku Klux Act of 1871, now Rev. Stat.

§ 1979, 42 U. S. C. § 1983 (1958), and 28 U. S. C. §1343

(1958). Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961), supra;

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 (1963).

“ There Congress has declared the historic judgment that

within this precious area, often calling for a trial by jury,

there is to be no slightest risk of nullification by state

process. The danger is unhappily not past. It would be

moving in the wrong direction to reduce the jurisdiction

in this field—not because the interest of the state is smaller

in such cases, but because its interest is outweighed by

other factors of the highest national concern.” Wechsler,

Federal Jurisdiction and the Revision of the Judicial Code,

13 L aw & C on tem p . P rob. 216, 230 (1948).

Seen against this background, it respectfully is sub

mitted, the broad language of Douglas v. Jeannette errs

in two fundamental aspects. First, it fails to give due re

gard to the Congressional judgment of importance of fed

eral judicial protection of federal civil rights under the

pattern of federalism which emerged from the post-war

amendments and enforcing legislation. Second, it ignores

the large shift in congressional temper which caused the

Reconstruction Congress—framers of the federal civil

rights jurisdiction—to see the federal courts, not the state

courts, as the generally fitting forum for the litigation of

questions of federal law; and it thereby overlooks the in

consistency with congressional purpose of remitting to the

state courts litigants for whose particular protection from

the state courts federal trial jurisdiction was created. This

16

is not to deny the legitimacy of Jeannette’s concern for the

state interest in state criminal law administration. The

problem is to weigh that interest appropriately. Where a

state statute is challenged on its face under the First and

Fourteenth Amendments—where a sustainable claim is

made that the statute in any and every instance and applica

tion violates freedom of expression— a State’s interest in

that statute’s undisturbed administration seems hardly to

preponderate over the prejudice to federal freedoms of

their suppression during “an undue length of time” required

for their vindication in the hazards and delays of state

criminal litigation. Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. 8. 360, 379

(1964). And where the statute is attacked as applied—

where its application to a particular set of facts is claimed

to infringe First-Fourteenth Amendment rights—it is all

the more important that the trier of the facts be a federal

trier. Holding last Term that a federal-question plaintiff

remitted to state court civil proceedings under the absten

tion doctrine was entitled to return for federal trial of

issues of fact at the conclusion o f the state proceeding,

this Court said:

“ Limiting the litigant to review here [the Supreme

Court] would deny him the benefit of a federal trial

court’s role in constructing a record and making fact

findings. How the facts are found will often dictate the

decision of federal claims. ‘It is the typical, not the

rare, case in which constitutional claims turn upon the

resolution of contested factual issues.’ Townsend v.

Sain, 372 U. S. 293, 312. ‘There is always in litigation

a margin of error, representing error in fact finding.

. . . ’ Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513, 525. . . . The

possibility of appellate review by this Court of a state

court determination may not be substituted, against a

party’s wishes, for his right to litigate his federal

claims fully in the federal courts.” England v. Louisi

17

ana State Board of Medical Examiners, 375 U. S. 411,

418-417 (1964).

The Jeannette doctrine, of course, does precisely what

England says may not be done: in a case admittedly within

congressionally given federal trial jurisdiction, it refuses

to hear the plaintiff and sends him into a state criminal

trial from which there is no federal trial return.12 This

it does notwithstanding, in cases touching First Amendment

liberties, the delays and dangers of state criminal trial may

appear to him so costly that suppression is the better part

of valor.

Amicus urges the Court to restrict Jeannette to its facts

and, reversing the judgment below, make clear the obliga

tion of the federal district courts to enjoin enforcement of

state criminal statutes which on their face or in their

threatened application violate federal freedoms of expres

sion. Such a mandate to the district courts is a matter of

urgent necessity. It is no hyperbole to say that the critical

issues of human liberty in this country today are not issues

of rights, but of remedies. The American citizen has had

a right to a desegregated school since 1954 and to a deseg

regated jury since 1879, but schools and juries throughout

vast areas of the country remain segregated. The American

citizen has a right of free expression, but he may be ar

rested, jailed, fined under the guise of bail and put to every

risk and rancor of the criminal process if he expresses him

self unpopularly. The “ right” is there on paper; what is

12 Except via the post-conviction habeas corpus route, with its

inevitable delay, and subject to the discretion of the federal dis

trict judge to deny the habeas petitioner an independent federal

trial of the facts under Townsend v. Sain, 372 U. S. 293 (1963).

In cases where First Amendment attack is made upon the criminal

statute on which the prosecution or threatened prosecution is

based, anticipatory federal injunction no more intrudes into state

criminal administration than post-conviction federal habeas corpus:

the only significant difference is that the first remedy is timely

and effective, while the latter is not.

18

needed is the machinery to make the paper right a practical

protection. Congress created some part of that machinery

in the federal injunctive jurisdiction given in 1871. There

remains to make the machine work. I f it does not, it is

merely delusive to suppose that the “basic guarantees of our

Constitution are warrants for the here and now . . . ”

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, 533 (1963).

CONCLUSION

As set forth in the above Motion for leave to file this

brief amicus curiae, the decision of the court below sub

jects lawyers engaged in civil rights cases to prosecution

under unconstitutional statutes with clearly predictable

harm to both the attorneys and those whom they are at

tempting to help. It is submitted that the doctrine of Doug

las v. Jeannette is inapplicable and that federal courts have

both jurisdiction to hear this case and ample statutory au

thority to grant the relief to which appellants are entitled,

and which all such attorneys must have to continue repre

senting persons seeking vindication of constitutional rights

in the courts.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

D errick A . B ell , J r .

Counsel for NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A n t h o n y G-. A msterdam

J ay H . T opkis

Of Counsel

38