Keeten v. Garrison Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keeten v. Garrison Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1985. 5eed2fa9-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a5cdc903-0b90-4ad9-b7d1-7b94db7c3ca4/keeten-v-garrison-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

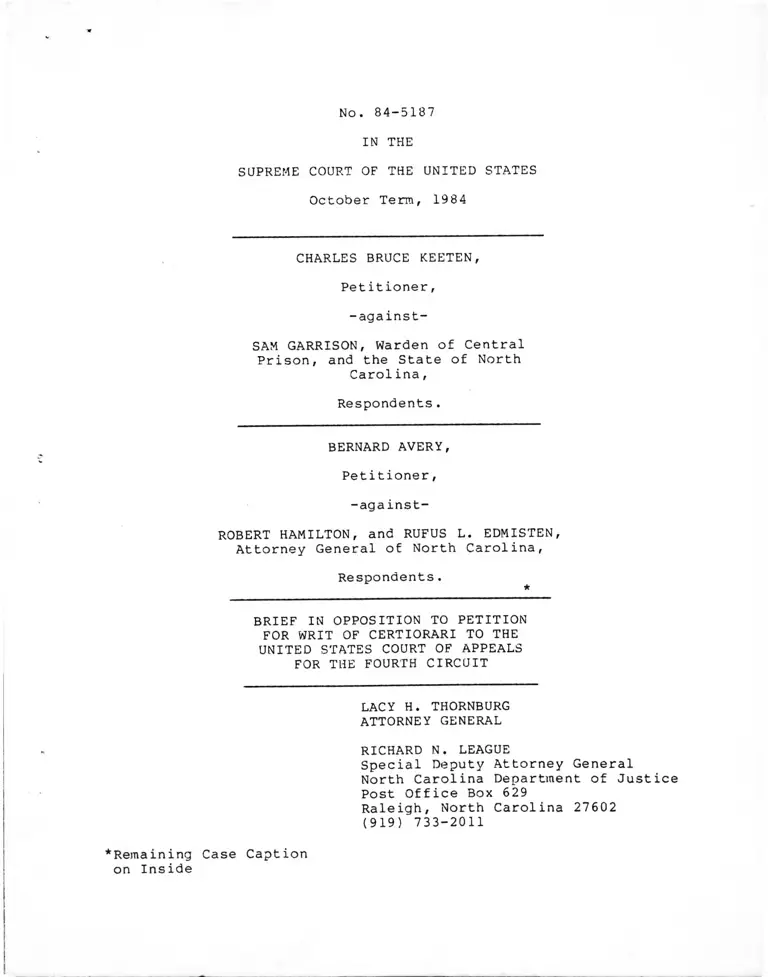

No. 84-5187

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Tern, 1984

CHARLES BRUCE KEETEN,

Petitioner,

-against-

SAM GARRISON, Warden of Central

Prison, and the State of North

Carolina,

Respondents.

BERNARD AVERY,

Petitioner,

-against-

ROBERT HAMILTON, and RUFUS L. EDMISTEN,

Attorney General of North Carolina,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION

FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

LACY H. THORNBURG

ATTORNEY GENERAL

RICHARD N. LEAGUE

Special Deputy Attorney General

North Carolina Department of Justice

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

(919) 733-2011

*Remaining Case Caption

on Inside

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. SHOULD CERTIORARI ISSUE TO CONSIDER WHETHER THE

EXCLUSION OF PERSONS WHOSE DEATH PENALTY OPPOSITION

CURRENTLY PREVENTS THEIR INCLUSION ON CAPITAL CASE

JURIES CREATES AN UNCONSTITUTIONALLY

CONVICTION-PRONE JURY OR DEPRIVES ACCUSED PERSONS

OF A FAIR CROSS-SECTION OF THE COMMUNITY ON THEIR

JURIES?

II. SHOULD CERTIORARI ISSUE TO CONSIDER WHETHER THE WAY

VOIR DIRES ARE CONDUCTED IN CAPITAL CASES CREATES

AN UNCONSTITUTIONALLY CONVICTION-PRONE JURY?

HI. SHOULD CERTIORARI ISSUE TO CONSIDER IF IT WAS

CONSTITUTIONAL TO EXCUSE A JUROR BECAUSE, WHENEVER

ASKED, SHE STATED SHE WAS NOT SURE COULD VOTE FOR

THE DEATH PENALTY EVEN IF THE LAW REQUIRED IT ON

THE FACTS OF THE CASE INVOLVED?

Pages

QUESTIONS PRESENTED............................................... 1

TABLE OF CASES.................................................... 11

OPINION BELOW...................................................... 2

JURISDICTION....................................................... 2

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND STATUTES............................ 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE...........................................2

REASONS THE WRIT SHOULD NOT ISSUE.................................. 3

CONCLUSION........................................................ 12

APPENDIX A:....................................................... 13

APPENDIX ..........................................................15

APPENDIX ..........................................................17

TABLE OF CASES

DUNAGIN v. CITY OF OXFORD, MISSISSIPPI,

713 F . 2d 738 , ( 5 Cir. 1983).................................... 7

GRIGSBY v. MABRY, ____ F.2d _____ (8 Cir. 1985)..................2

PEOPLE v. FIELDS, 673 P.2d. 680 (Cal. 1984.)......................2

REASE v. UNITED STATES, 403 F.2d 322 (DCApp. 1979 ).............. 11

RISTAINO v. ROSS, 424 US 589 , 595 ( 1976)......................... 11

SMITH, KLINE AND FRENCH LABORATORIES V.

A. H. ROBINS COMPANY, 61 FRD 24, (ED PA 1973)................ 9

STATE v. AVERY, 299 NC 126 (1980)............................... 10

STATE v. COLVIN, 297 NC 691 (1979).............................. 10

STATE v. WEBB, 364 S02d 984 (La 1978)........................... 11

UNITED STATES v. GENERAL MOTORS CORPORATION,

384 US 127, (1966 ).......................

TABLE OF CONTENTS

7

NO. 84-5187

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1984

CHARLES BRUCE KEETEN,

Petitioner,

-against-

SAM GARRISON, Warden of Central

Prison, and the State of North

Carolina,

Respondents.

BERNARD AVERY,

Petitioner,

-against-

ROBERT HAMILTON, and RUFUS L. EDMISTEN,

Attorney General of North Carolina,

Respondents.

LARRY DARNELL WILLIAMS,

Petitioner,

-against-

NATHAN A. RICE, Warden of Central

Prison, and RUFUS EDMISTEN,

Attorney General of North Carolina,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR

WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR

WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Respondents oppose a grant of certiorari in these

cases. Although there is a conflict in the circuits on the

conviction-prone jury issue, respondents feel the court will have

no trouble summarily reversing the Eighth Circuit in Grigsby v.

Mabry, ______ F . 2d ________ (8 Cir. 1985) in which certiorari will

soon be sought by the State of Arkansas. In addition, the

California Supreme Court seems to have recently moved away from

its Hovey decision in People v. Fields, 673 P.2d. 680 (Cal. 1984)

so that this remaining pillar of support for Petitioners may yet

fall on its own. The method-of-voir-dire issue is based only on

a single study and therefore is too undeveloped for meaningful

court review. Finally, the single juror exclusion issue in

Petitioner Williams' case is clearly covered by Wainwright v.

Witt, ____ US ______ ( 1985) .

OPINION BELOW

JURISDICTION

CONSTITUTIONAL

PROVISIONS AND STATUTES

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Pursuant to Rule 34.2 of the Supreme Court, these items

are omitted.

2

REASONS THE WRIT SHOULD NOT ISSUE

I. THE CONVICTION-PRONE JURY ISSUE SHOULD

NOT BE REVIEWED IN THIS CASE BECAUSE THE

FACTUAL PREDICATES FOR FINAL DECISION

ARE PROBABLY MISSING.

This case has been approached by the Petitioners as

purely an evidence case and, as such, is too mundane for the

court's consideration. They have tried to put it into both a

directed-verdict mold, claiming all the evidence is in and on

their side; and a trial-court-findings-bind-appellate-courts

mold, which in view of the endorsement of the studies by the

district court might automatically win for them. Neither

approach, however, is correct; each will clutter the court's

final decision on this issue, to be made most likely in Grigsby;

and Petitioners have not shown so far (or even sought to show)

that any of the excluded jurors in their cases could have been

fair and impartial on the issue of guilt, despite their death

penalty opposition. This was not expressly covered in voir dire

and it is crucial to Petitioners because they say inclusion of

such jurors is their only aim, not inclusion of all current

Witherspoon excludables (WEs).

A.

Petitioner's first argument — that the evidence is

exclusively favorable to them — is wrong; and not only that, the

deficiencies noted in Witherspoon have not been remedied. If

taken at face value, the studies Petitioners rely on are

consistent with the idea that the stronger one's opposition to

the death penalty, the likelier one is to have a somewhat

jaundiced view of the criminal justice system; and that in mock

3

trials without such things as an oath or deliberations

beforehand, the likelier they are to acquit. This, however, is

exactly what the proof showed in Witherspoon, albeit more

modestly. What was not shown then, or now, is (i) that general

pre-trial attitudes about the criminal justice system will affect

real juror behavior in concrete cases in the face of voir dire,

oath, evidence, instructions, and deliberations; ̂ (ii) that

nullification is not a real problem or that it can be adequately

handled if WEs sit on capital case juries; (iii) that if there is

a true phenomenon of conviction—proneness, it has the substantial

effect Witherspoon requires; and (iv) that mock jury trials

predict the outcome of real jury cases. With these deficiencies

in the predicate factual proof, the legal issue of whether

conviction proneness in juries is constitutional cannot be

reached.

Putting aside the probability of nullification and the

1The district court claimed that this was just common

sense but it is an issue on which the general field of psychology

is split into four groups — attitudes cause behavior, behaviors

cause attitudes, each cause the other, neither operates on the

other, "Attitudes Cause Behaviors" (ST), Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 37: 315 (March 1979). The quantification

of the attitude — behavior relationship frequently has been

noted to be only about 10 percent at most. Put another way,

differences in attitude account for (not necessarily cause) 10

percent of the variation in behavior. Dr. Allen Wicker found

this generally true in the 1959 survey of research on this

relationship up until that date, "Attitudes Verses Actions

(ST) , "Journal of Social Issues, Autumn 1969 :4 . Dr. Gerald S’nure

testified to this in the Grigsby hearing; and Dr. Michael Saks

found this to be true in the single-attitude variable in jurors

he tested, Saks and Hastie, Social Psychology in Court (New York

1978) 65. The only close relationship between attitude and

action appears when the former is closely linked to the

possibility of the latter, such as attitudes favoring political

candidates causing a person to speak out in their behalf or

strong religious beliefs causing a persons to attend church.

4

lack of substantial impact on which there is virtually nothing

favorable to Petitioners and focusing on the first and fourth of

the above since they involve the inferences Petitioners want to

be drawn from their two main groups of studies, there are two

pertinent adverse studies unmentioned by them, one by Dr. Steven

Penrod, another by Dr. Hans Zeisel. Neither study appears to

have been cited to the courts in either the Hovey or Grigsby

cases.

Dr. Penrod, a well-known jury researcher, did a study

for his doctoral thesis to determine if 347 persons in answering

attitude questions about the criminal justice system and in

voting in four mock cases (three criminal) showed any correlation

between the several attitudes, between the several verdicts, or

between the attitudes and the verdicts. This research is

especially important because none of Petitioners studies test

these; and the attitudes checked included whether a person not

testifying probably had something to hide, a person being

prosecuted was probably guilty by virtue of that fact, and guilty

persons often escaped on technicalities, all similar to tnose in

the studies Petitioners rely on. Dr. Penrod's tables and a

rearrangement of his conclusions appear in Appendix A and he

found virtually no correlations. In the Fourth Circuit,

petitioners said only that Dr. Penrod had changed his mind due to

a recent collaboration with Dr. Hastie, Petitioner s witness in

Griqsby, and a statement appearing in their book, (a copy of

which is attached as Appendix B for the court's own determination

on this); disclaimed reliance on attitudes affecting behavior (an

5

assertion that immediately made their six surveys and about half

of their testimony irrelevant); and asserted Dr. Penrod's study

had no bearing because it did not differentiate between death

penalty proponents and opponents, even though this fact showed

that whatever group one was in, the attitudes and verdicts did

not correlate. These skimpy arguments do not warrant the Court's

rev iew.

Dr. Zeisel's study on "felt responsibility" in

simulations is set out in detail as Appendix C and its impact on

the issues cannot be minimized. After comparing the results of

10 real juries and two sets of "shadow" juries hearing the same

cases and being treated in the same way, Zeisel concluded that

the real juries' convictions in only one-half of the cases

compared with one set of shadow juries' convictions in 3 of 10

cases and the others' convictions in all 10 cases indicated that:

...despite all efforts to equate experiences,

jurors on the real jury had a different

standard for the meaning of "guilty beyond a

reasonable doubt" than those whose decision

was not binding on the defendant, whose

conviction could not send an individual to

prison.

Against this in the Fourth Circuit, however, Petitioners only

claimed'that Zeisel was their witness, which was true despite

this study which he did not mention in his testimony; that

Zeisel's 1955 survey was not considered on this point, although

it did not deal with felt responsibility at all and Zeisel

himself described it as being "full of such weak points" (Moore

Tp 83); and that Zeisel had changed his orginial conclusions in

6

"The Effect of Peremptory Challenges" (ST) 30 Stanford L. Rev.

194, 498, 511-513 (1978) although this was true with only one set

of the shadow jurors and was caused these jurors having been

subject to voir dire, something missing in all the mock jury

tests on which Petitioners relyl These arguments are also

undeserving of this Court's time.

B.

Petitioners' other evidentiary-based argument — that

the district court's factual findings bound the circuit court,

thereby automatically winning for them — is both legally and

factually incorrect also.

First, in a "documents case," as this is, appellate

courts historically have taken more leeway in reviewing district

court decisions, see e.g. United States v. General Motors

Corporation, 384 US 127, 144 (1966) fn. 16 even within the

confines of this rule. Moreover, as social science literature

and testimony is involved,strict use of this principle of review

would permit different results district-wide in this country, not

just in individual cases. Only decisions on 'natters of law

reviewable on appeal normally can have this effect. Therefore,

this sort of review of similar evidence has been rejected

recently in Dunagin v. City of Oxford, Mississippi, 718 F.2d 738,

748 (5 Cir. 1983) fn.8. Were this not so, however, the district

court's decision would remain incorrect for three reasons.

First, in the district court's opinion at p 1171-1177,

it finds only that the studies presented by Petitioners are as

they appear to be in terms of their procedures, calculations and

7

outcome. It does not find the criticism of those studies untrue

or that Respondents studies and evidence are not true but only

that they do not persuade it of the ultimate legal conclusion

Respondents argue for. Therefore, no impediment to use of

Respondents' evidence on appellate review exists.

Second, even under the standards of Zenith Radio

Corporation v. Hazeltine Research, Inc., 395 US 100 (1969), the

District Court's findings do not pass muster as they are not

supported by substantial evidence, especially in light of the

Penrod and Zeisel studies previously mentioned. Finally, the

District Court misapplied the law and rested its decision on

assumptions about attitudes affecting behavior, nullification

being no problem, mock jury results predicting real world

results, and substantiality of impact which are not proven.

Therefore, the court need not wrestle with the transcript

— searching exercise Petitioners have in mind for it on this

issue.

II. THE METHOD—OF-VOIR-PIRE-ISSUE , COMMON

TO ALL THREE CASES, SHOULD NOT BE

REVIEWED AS IT IS BASED ON ONLY A

SINGLE PIECE OF SOCIAL SCIENCE

RESEARCH YET ARGUES FOR A DRASTIC

PROCEDURAL CHANGE

One of Petitioner's studies is a singular one done by

Dr. Craig Haney of the University of California at Santa Cruz.

Rather than dealing with conviction-proneness because of

pre-existing attitudes about the death penalty, its thesis is

that the way voir dire is held may have a biasing effect, mainly

in that death penalty opponents are excluded (denigrated) while

8

others in saying they will consider the death penalty are

accepted (favored) and have made a public (reinforced) commitment

which increases their likelihood of imposing the death sentence.

This is a separate issue because a claim for relief is

the aggregate of operative facts which give rise to enforceable

right, Smith, Kline and French Laboratories v. A. H. Robins

Company, 61 FRD 24, 28 (ED Pa 1973); and the method claim alone

meets this description. Whether a jury is conviction-prone

because of attitudes on the criminal justice system or the death

penalty is simply not the same as whether it is conviction-prone

because of the way the court holds a voir dire. To satisfy the

Petitioners on the latter point all that needs occur is an

individual voir dire and a single death penalty question, as

proposed by Dr. Haney. However, to satisfy Petitioners on the

first point requires inclusion of those persons currently

excluded under the Witherspoon. If either of these were done

alone, they would not ameliorate the other complaint.

Respondents have argued so far that the test was poorly

done, to which there has been no substantial answer by

Petitioners in either the District Court or the Fourth Circuit.

However, even were Dr. Haney's study the best possible one,

Respondents doubt that the court would make Dr. Haney a one man

constitutional convention by requiring as a constitutional

imperative the voir dire remedies his single study proposes

which, as noted above, are a single question on the death

penalty and an individual, sequestered voir dire.

In light of the above, certiorari should not be granted

to review this issue.

9

III. THE INDIVIDUAL JUROR ISSUE IN

WILLIAMS' CASE — EXCLUSION OF

MS. MELTON FOR HER OPPOSITION

TO THE DEATH PENALTY — SHOULD

NOT BE FURTHER REVIEWED AS IT

IS ADEQUATELY COVERED BY

WAINWRIGHT V. WITT.

Ms. Melton, while stating generally she could do her

duty as a juror, nevertheless hedged on three occasions when

asked if her death penalty views would stand in the way of her

following the law and the court's instructions if that would lead

to the death penalty, saying she was not sure she could return a

death sentence. She was excused for cause and no rehabilitation

was attempted, although objection was then made by the defense

and the North Carolina Supreme Court reviewed the issue on its

merits. The Witherspoon, Adams and Witt cases cited by

Petitioners all prevent relief on this issue and do this so

clearly that no further exposition of the law need be made.

First, under Witt, Judge Snepp's voir dire and his

decision to strike are the same sort of findings that Witt held

entitled to acceptance under 28 USC §2254, absent circumstances

not present here. This being so, his decision all but ends the

review as he certainly knew the law, having been on the bench as

a Superior Court judge since at least 1963, 273 NC iv; thereafter

presiding over several capital case voir dires, see e.g. State v

Colvin, 297 NC 691 (1979), State v. Avery, 299 NC 126 (1980) and

having questioned Ms. Melton in language consistent with

Witherspoon, Adams and Witt.

Second, while there are semantic differences between

the language of two the prospective jurors, the Witt standard

10

easily covers Ms. Melton's responses. Uncertainty and the lack

of a commitment before an oath obviously compromise and invite

its demeaning if it is ultimately taken, so as to prevent or

substantially impair the performance of juror duties. Also, the

situation noted in Witt seems to be present here — that bias may

not be made clear by some people's spoken language, yet be

revealed by their overall appearance. This is why the usual

approach is to commit the decision on a juror to a trial court's

discretion in an ambiguous situation, see e.g. Ristaino v. Ross,

424 US 589, 595 (1976), Rease v. United States, 403 F.2d 322

(DCApp. 1979), State v. Webb, 364 S02d 984 (La 1978).

Third, Judge Snepp's decision is bolstered by

recollection that it is a general and unremarkable principle of

law that while at the outset of voir dire, all persons are

presumed competent to be jurors, if voir dire reveals an

uncertainty about this due to views on punishment, the juror is

disqualified, United States v. Gonzalez, 483 F.2d 223 (2 Cir.

1973), rather than making the litigants take a chance on this.

Any other system would be absurd and Respondents cannot believe

that this raises a constitutional question.

In light of the above, certiorari should not be granted

to review this issue.

11

CONCLUSION

court will

certiorari

For the reasons above, Respondents pray that the

deny the Petitioners application for a writ of

l —

This /3 rd day of March, 1985 .

LACY H. THORNBURG

ATTORNEY GENERAL

Richard N. League

Special Deputy Attorney General

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, NC 27602

(919) 733-2011

12

APPENDIX A: THE PENROD STUDY

Bearing in mind that in social science, a statistical

correlation of .30 is low, Downie

Methods (New York, 1974) Chapter

for only 9% of any variance found

this case , Dr. Pen rod found: (a)

and Health, Basic Statistical

7 and that a .30 would account

according to the evidence in

on attitude verdict correlation:

CORRELATIONS BETWEEN ATTITUDE VARIABLES

TABLE 12 AND VERDICT PREFERENCES

Cases

Predictor Attitude

Variables Harder Rape Robbery Nellis Attitudi

lA Harsh Sentences .0 3 .02 .03 -,0d .25'

2* Punish Causers of Death -.01 .15 -.01 -.on ,n8'-

3* WeaDon Carriers Trouble .07 .08 -.02 -.05 .60 '

Minority Trials Unfair .01 -.on .06 .on • .16 '

5* No Testr.nony=Hldlnit -.03 .07 .03 -.06 .51 .

6 Require Rape Resistance .22 .26 -.02 -.01 .02

7 Drunlc Defendant Affect Verd .02 -.03 .02 .09 ' .01

8* Escape on Technicalities .09 .00 .02 -.11 .ns »

9* Prosecuted Probably Guilty .on .13 .06 .09 ! .36 -r

10 Collect on Pain & Suffering .01 .06 -.05 -.01 -. m

11 Awards Cause Suits .13 .01 .00 -.15 .25

12 Consider Defendant's Wealth .08 .05 -.07 -.01 .on

Attitude Scale (Sun •) l • o -1 .16 .06 -.06

This caused him to conclude:

The pattern of correlations clearly^ shows that most

of the attitude variables bear no relationship to the

verdict perferences (with the notable exception of

the rape resistance question and the rape verdict):

23 of the 48 relevant correlations are negative....

The ultimate resolution of this problem was to

construct a sing~le_new_,^t titude_ scale based on the

summed normalized responses of the jurors on the

seven attitude variables concerned with crimina1

behavior',' 'inferences of ~de fendant' s guilt.and

punitiveness.... The results for the scale .are

even weaker. In each instance the scale correlates

in the wrong direction wich the case verdicts.

(The text above was rearranged for purposes of emphasis; emphasis

was supplied. )

13

(b) on inter-attitude correlation:

The intercorrelations between the attitude variables

were rather low - only the "weapons" with "no

testimony" (r=.25), the "harsh sentence" with

"minority trial fairness" (r=.23), the "harsh

sentence" with "drunk defendant" (r=.21) and the

"consider wealth" with "awards cause suits" (r=.2)

exceeded r= .2. twenty—two other correlations

ranged between .10 and .20 and 40 others were under .10.

(c) and on correlation between verdicts:

TABLE II CORRELATIONS AMONG VERDICTS

,c a us in g

Murder Raoe Robberv

Rape Verdicts -.131

Robbery Verdicts .040 .021

Negligence Verdicts .030 .036 -.025

him to conclude:

These verdict preferences were not highly interre

lated. As shown in Table II the highest correlation

(-.13) is between the rape and murder verdicts (p <.02).

None of the other correlations are statistically

significant. The low correlations suggest there are

no general conviction- or acquitta-l-prone juror

"types" (e.g. authoritarians or dogmatists) whose

behavior can be predicted across cases.

While Dr. Penrod's subjects were not divided by death

penalty views into DQs and WEs and therefore his study does not permit

a comparison between the groups, the fact that in recent years DQs

have greatly outnumbered WEs, coupled with the fact that the correlations

were virtually non-existent appear to mean that because DQs' attitudes

on the matters inquired about do not relate to their vote, these persons

are not conviction-prone to any significant degree on account of their views.

14

APPENDIX B: HASTIE & PENROD

INSIDE THE JURY (CAMBRIDGE, 1983)

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES AM ONG JURORS

In fact. estimates of the method's efficacy arc not precise. An accuracy

rate of TO percent has been claimed (Kairvs et al.. 1975: Silver, 1978). How

ever. if half of all jurors are expected to vote for conviction, simple guessing

or coin-flijipmg would yield a 50 percent accuracy rate. And il 80 percent

of the jurors preier conviction, either in a single case or across cases, an 80

percent accuracy rate can be achieved by always predicting conviction.

Efforts to select jurors on the basis of their demographic, personality, or

attitudinal characteristics also have not enjoyed much success (Berman 6c

Sales, 1977). The few relationships observed do not provide significant ad

vantages in jury selection. In one study 780 jurors viewed the same video

taped burglarv trial and then deliberated, as pines, to a verdict (Saks. 1977 .

Demographic and attitudinal information from the jurors was used to pre

dict their votes. The single best predictor, a question on whether crime was

mainly the product of "bad people” or of "bad social conditions,” ac

counted for only 9 percent of the variance, and the four best predictors to

gether accounted for less than 13 percent.

The relationships between juror behavior and juror attitudes, personahtv.

and demographic characteristics are not well understood. More than i60

jurv studies provide little systematic evidence' that personality variables,

such as authoritarianism, locus of control, ana legal attitudes, provide tne

predictive power needed to detect and challenge biased jurors, even assum

ing that requisite information on prospective jurors is available in voir dire

(Berg & Vidmar. 1975; Buckhout. 1973; Boehm. 1968; Jurow. 1971; Buckh-

out ct al., 1979; Sosis. 197-1; Kauffman 6c Rvekman. 1979). Furthermore, de

liberation may operate to nullify biases that exist before deliberation t Kap

lan 6c Miller, 1978). On the whole, this implies low efficacy for jury selection

strategies based on personality characteristics.

But attitudes about crime in general, particular crimes, or particular

cases are a fruitful source of information on juror bias. Public opinion pods

find that jurors who arc strongly opposed to the death penalty tend to be

less conviction prone than jurors who are not strongly opposed t Bronson.

1970, 1980; Harris. 1971; Ellsworth 6c Fitzgerald. 1983). Data Irom posttrjjij

interviews with actual jurors and simulated juror decision-making studies

are also consistent with the conclusion that those strongly opposed to the

death penalty are likelier to vote tor acquittal (Zeisel. 1969; Guldlierg.

1970; jurow. 1971; Ellsworth. Thompson. 6c Cowan. i983). Researchers

found that iiirors' altitudes regarding rape are also related to their decisions

in rajie cases iFcild. 1973). Attitudes on punishment were toimd to tie the

127

15

a civil case—which included upcninc, and closing arguments, witness lesti-

mon>. and instructions by a judge iPenrod. 19791. Analysis of the jurors al

titudinal and demographic characteristics showed that no variable had a

strong relationship to actual verdict preferences, the highest correlation

-being +.I-S. lutiddition. multiple regression techniques showed an average

of 11 percent explained variance for the verdict preferences in the four

casev with the highest R* = .16 for the rape case. This implies that anyone

■who is aware of the relationships between the attitudes, demographic fac

tors. and verdict preferences in the rape ease can. in principle, do better

than chance in predicting juror preferences. If half the jurors in a jury ve

nire vote to convict at the end of the trial, those relationships would accu

rately predict the verdict preferences of TO percent of the jury venire, as

opposed to the 50 percent accuracy rate obtained by coin flipping. Of

course, this assumes that all the appropriate attitudinal and demographic

data arc available to the jury selection team. It is quite unlikely, however,

that the usual systematic methods of jury selection will yield a criterion as

reliable as the verdict preferences obtained in the Penrod study.

AID analyses were also performed in Penrod’s study. The results were

similar to the regression results: in none of the four cases was it possible to

predict verdict preference at high levels of accuracy. Although the AID

analyses could sometimes account for as much as 25% of the variance in

verdicts, subsequent tests demonstrated that much of the variance ac

counted for" was actually error variance. In effect, no research lias pro

vided evidence that social scientific methods can be a powerful aid to at

torneys in the task of detecting juror bias. However, attitudes, particularly

case-relevant attitudes, such as toward the death penalty or rape, appear;Jo

be the most powerful individual difference predictors of verdict preference

peM&sii that have been studied to date.

■ One purpose of the present mock jury study was to evaluate jury selec

tion techniques. The 825 jurors provided information on their personal

backgrounds in a postdeliberation questionnaire, including age. gender, oc

cupation. residence, education, political party, ideology, marital status, in

come. race, number of previous cases heard as a juror, and number of previ

ous criminal cases heard as a juror. This information was entered into a

step-wise multiple regression, with variables such as occupation and resi

dence included to reflect socioeconomic status, and using predelilieration

verdict preference as the dependent variable, assuming equal interval

values ranging from one lor first degree murder to lour for self-tleleiise.

Only four variables produced significant /•"’s (overall /•' [5. i-12| = 5.22). htn-

plovcd versus nonemployed. including retired, entered first with the highest

correlation r = .119. Juror gender ir = —.073) brought the multiple H to

.115. number of previous criminal eases as jurors (r = —.059) raised R to . 15.»

128

APPENDIX C: ZEISEL

STUDY

l } • >

► :• ■

iC

.t*iA

1 (J . J:

Proceedings

of the irJ: '...

Division of Personality.

and ; " •

Social Psychology,. 1974

*♦ ..

1 *' ; ’ ‘ T

- t

U a;u ~ii f, u l*v** p,*! p< \* vy .J !:• h '/ y lV ft tj „ t... y m i ij t/ r# yc.f M 1 M j--g O a H • •Livi'E.A.-a LJJ ...

; ** /

• -i' . IVti-•*’.< * ; - •• ■

•VjJ V ;i.fj* .* ••. v.-a'.: . ■* ■ *

. I' t| •V ‘ ■■'I1 • i: .•••.'•'•:• *. ••• i•i.. vu-\

17

Circle

276

A Courtroom Experiment on

Juror Selection and Decision-Making

Shari Seidman Diamond, University of Illinois, Chic;

Hans Zeisel, University of Chicago Law School

— r. la£t several years psychologists have begun to turn their attention

_of their investigations have centered on the jury,j^deciliw*.

, iacr several vears psychologists have begun to cum m e n

In the las y investigations have centered on the jury. Apart iT

f !°socIoUg « l ^ d f b hKalven and Zeisel (1967) comparing Judge and Jury decis^.

large sociol B , a the laboratory with mechanically reproduced trial

» » « of the »ort ha, boon - * “ “ " . l l a a y s . haunting suspicion that lnfot-

frequently using stud.nt. “ ™"'ndsubject populations will not apply »

of their case. This experiment was planned to test tne accuracy

aactclsing. such challcngas.^ ^ federal tt?rles cases in the b S. CM*,,

for the northern District of Illinois uas tried ‘- the presence o f t h r e } ” “ J; ...

r -S p ec^ u /h y

not°learn ^interviewing indicated that this

system had successfully avoided juror awareness). , ;th were present i» l*

" During the trial, all three juries were coi^ro^ihen the lawyers

courtroom throughout the trial, they were rem 4Uror fee by the Courts, and their

wished the Jury absent, they were paid the standard Juror f b y ^ ^ gf the trial, e»‘

employers were notified they were involved in jury ser . A ^ evidence for inspec*

jury went to its own deliberation room, receiv|£ cop*“ lunchtime occurred during

tion, and deliberated until a verdict was reached ^ tion on a point of U« ~

deliberations, free meals were supplied. If any Jury " exocJilnental Juries were treated

ing deliberation, the Judge answered it. In short, the T f*rth Jhe judge impressed

ms nearly as possible as though they were real juries. A case began. The

pon them the importance of their Job in a special sessionh / their verdict would «»* de ______ m rh* exnerimental Jurors knew that cneir v«=‘ ___

ir Job in a special session betore m e -e.

ii; differences' were: (1) Che experimental Jurors knew Chet the rver Q)„,

ide the case; (2) they sat in the spectators' seats ^ r" ions Indicating hi.

T5r“ i”^?s- •« -

tTen"criminal'cases lasting f ™ several

:rom draft evasion to conspiracy and extortion, before the jury returned it*

:hree separate jury verdicts were produced p^thermore dccision would h.«

/evdict, the judge in the case indicated on a questionnaire wn

>een.

Cuilty

Judge

9

Real Jury

5

EnCJisn juiv

10 6

Hot Guilty 1 5 0 2

------oiatti"--.. i- vice upre related and the tour occision-maac...------ Iince the cells frequencies , fcipoel 1956) The obtaintd !ets of jud^ents, Cochran's Q was used to analyze the data (Siegel, 1956). T ̂ j

W3S The^pat tern5of these results suggests that, despite all efforts to equate t*- ,|,r* ,

18

277

jjperience, jurors on the real jury had p different standard for the meaning of "guilty

^yond 4 reasonable doubt" than those whose decision was not binding on the defendant,

conviction could not send an individual to prison. While such a pattern also may

jjve resulted from the differences in jury composition, an important point.argues against

thi»* The En6li-sh or random jury is really a composite of the two other juries, those

cicused plus those retained, yet the random jury convicted in every-case with a sub-

,:intial majority favoring conviction on the first vote. Clearly, the only way to

pliably test the effect of real decision-making in this situation, would be to get

,t:orneys in a series of cases to select two juries. Both would hear the case, and the >

fJly difference between them would be that one jury would know that it would be deciding

ictual verdict and the other would be aware that its decision would not affect the

rt*l outcome of the case.

With this important caveat on the interpretation of this study, the predeliberation

billots of the jurors on the challenged Jury were compared with the source of their

iitusal. It- seven of the ten cases, defense attorneys successfully eliminated more Jurors

¥we favored a guilty verdict than a not guilty verdict, while in two cases equal numbers

ef friendly and unfriendly jurors were removed, and in one case errors exceeded accurate

rc,0vals. Despite the generally greater willingness of experimental Jurors to convict,

t».e prosecutors did almost as well in their jury selection. In five cases they elimi-

y.cd more jurors who voted for acquittal than for conviction, in two cases their removals

balanced, and in three others the excused jurors were more likely to vote for conviction,

ifter the juror selection in each case, attorneys filled out a brief questionnaire

jfldieating the reasons for each excusal. The msot frequently mentioned reasons were

■‘cr-canor, occupation, residence, sex, age, and race. Excuses motivated (at least in

ft) by race were most likely to be correct (89%), followed by demeanor (76%), residence

(JO'’.), age (67%) and occupation (62%). Sex was least likely to be a successful predictor

{-»)•All conclusions drawn from this study, however, are subject to the same potential

.'oblcrs of interpretation surrounding the conviction pattern. We do not know the extent

to which studies of jury behavior are distorted, not merely on likelihood of conviction,

i. j on other variables and interactions with other variables as well. The differences

|3 percept ion between real and simulation decision-makers may affect the structures of

^liberations as well as their outcomes. Yet true field experiments with juries and

ether decision-makers of interest, although theoretically possible (2eisel and Diamond, 1974),

jjv be limited by legal, ethical, or practical constraints.

References .

filven, H. 6 Zeisel, The American Jury. Boston: Little, Brown 6 Co., 1967.

Sicgd, S. Konparnmetric Statistics for the Bchaviora1 Sciences, New York: McGraw-Hill, p

1956.

♦tiseli H. 6 Diamond, S. S. "Convincing Empirical Evidence", University of Chicago Law

Review, Spring, 1974.

>1

19

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

A copy of the foregoing has been deposited in

the United States Mail, postage prepaid and addressed as

follows:

Mr. Jack Boger

Attorney at Law

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10019

Mr. Anthony Amsterdam

40 Washington SQ. S

New York, NY 10012

Mr. Samuel Gross

886 Richardson Court

Palo Alto, CA 94303

Mr. James C. Fuller, Jr.

Attorney at Law

P. 0. Box 470

Raleigh, NC 27602

Mr. James E. Ferguson, II

Mr. Thomas M. Stern

Attorneys at Law

951 S. Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, NC 28202

Mr. Adam Stein

Ms. Ann B. Petersen

Attorneys at Law

P. O. Box 1070

Raleigh, NC 27602

This / day of March______ , 1985.

Special Deputy Attorney General