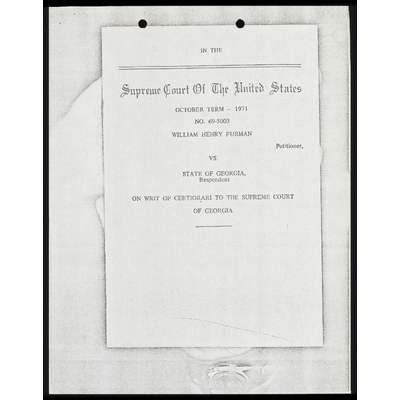

Supreme Court Judgment Affirming Decision

Public Court Documents

1971

16 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Furman v. Georgia Hardbacks. Supreme Court Judgment Affirming Decision, 1971. d4a72ba9-b225-f011-8c4e-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a5d80a3d-16cf-4a4c-909a-de41282445c9/supreme-court-judgment-affirming-decision. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

: | IN THE

AS 4 45 2049 S44 40 | f 7 pis] +1 Pe! A= 4,

Supreme @ourt Of The Lvited States |

| OCTOBER TERM — 197] |

i

| NO. 69-5003 :

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN |

Petitioner,

VS.

Sn |

STATE OF GEORGIA, |

Respondent

|

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPR REME COURT |}

:

no f

OF GEORGIA |

|

i

|}

AS BESS i SSS

IN THE

E

T

S

SO

Supreme Court Of The United Dtates

OCTOBER TERM — 1971

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NO. 69-5003

WILLIAM HENRY FURMAN

i

|

Petitioner,

VS.

H

STATE OF GEORGIA,

|

Respondent

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF GEORGIA

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

34 Lawyers Edition, page 519, 136 U.S,, 436,447 ... 3

| 95 Lawyers Edition, page 345,99 U.S., p- 130 sie. 4

i 356 U.S. page 86, 7 Lawyers Edition 2,p.630 ...... 5

i 93 Lawyers Edition, p. 1337,337 U5. p. 20-353...

325 Federal 2d page CT EER AT

U TR LE Ea 7

| 329 U.S. page 459-481, 91 Lawyers Fd.p.422 ..... 9

Bill of Rights of 1688 and Act of Parliment .......- 10

I ap th SAE

A TR Amt wo) Base oe ys SE Ss ss ATPL TaN Satta

RE AR Rss ie . . iid # SS SRR SAS deni Sa RE a rE ER Sal I bln St A oi I ii NAR

i

STATEMENT OF FACTS

William Henry Furman was tried and convicted

on the 20th day of September, 1968, for the murder of

William Joseph Micke, Jr., and sentenced to death by

electrocution as a result of the verdict of the Jury.

Mrs. Lanell Micke after being sworn testified

that between the hours of 2:00 and 2:30 A.M., on

August 11, 1967, she and her husband thought they

heard one of their five children, Jimmy, walking in the !

kitchen. The son Jimmy, was a chronic sleep walker. (Tr. |

of E. page 17, lines 19 through 33). She and her husband

lay in bed about five minutes and heard the noise again

coming from the kitchen and her husband removed

himself from the bed to investigate. (Tr. of E. page 18

lines 25 through 40). She heard her husband call out to

Jimmy to get back in bed, heard his footsteps quicken

and all of a sudden heard a loud sound and he screamed.

(Tr. of E. page 17 lines 1 through 14). She became

frightened got all her children in one room and started

screaming for Mr. Dozier, the next door neighbor. (Tr. of

E. page 17, lines 16 through 20). Mr. Dozier and a person

named Johnnie came over shortly after the screaming of

Mrs. Micke and called the Police. (Tr. of E. page 19 lines

25 through 29). She testified that there was a back porch

to the house where she and her husband lived and that

you could gain entry into the kitchen from this back

porch. The porch was enclosed by a screen and the screen

door has a lock which she did not remember whether the

screen door was locked that night. (Tr. of E. page 19 lines

38 through 41, page 20 lines 1 through 13). Mrs. Micke

did not go to the kitchen because she was scared and

feared for the lives of her children. (Tr. of E. page 21

lines 39 through 41, page 22 lines 1 through ©}.

Sgt. G.W. Spivey of the Savamnah Police

Department testified that he answered a call 10 S08 West

63rd Street, the home of the deceased, at approximately

2:30 A.M., on August 11, 1967. (Tr. of E. page 24 lines

15 through 20). When he arrived he went in the back

door and acting on information he received azd believing

the subject was still in the house crouched in the

doorway leading to the kitchen at which time he saw the

pS he Seg ie rd Xa

body which later was identified as Mr. Micke. (Tr. of E.

page 25 lines 1 through 29). Upon his examination he did

not find anyone else in the house other than Mrs. Micke

and her children. (Tr. of E. page 725 lines 21 through 29).

Dr. Harold Smith, Coroner for Chatham County,

Georgia, testified that on the 11th day of August, 1967,

he examined the body of William Joseph Micke, Jr., and

that death was caused by a bullet wound which entered

the upper chest causing severe lung hemorrhage. (Tr. of

E. page 32, lines 23 through 28). He removed the bullet

from the body of Mr. Micke and turned this bullet over

to Detective B.W. Smith. (Tr. of E. page 32, lines 29

through 34). :

Sgt. J.E. Mincey of the Savannah Police

Department Identification Officer, testified that on

August 11, 1967, he went to the address of 508 West

63rd Street and lifted from the back porch on a washing

machine some latent fingerprints that he compared these

prints with the known prints of William Henry Furman

and that they were identical. (Tr. of E. page 33 lines 20

through 35, page 34, lines 1 through 14). These prints,

both latent and known prints were sent to the Federal

Bureau of Investigation in Washington, D.C.. (Tr. of E.

page 34, lines 16 through 19).

John F. Walters, Federal Bureau of Investigation

Identification Division, testified that he examined and

compared the prints sent by Officer Mincey and that the

known prints of Furman are identical with the latent

prints. (Tr. of E. page 35 lines 21 through 29, page 36

lines 1 through 20).

Officer Alphonso Hall, Savannah Police

Department, testified that he answered the call to 508

West 63rd Street at approximately 2:30 AM., on August

11, 1967. (Tr. of E. page 37 lines 28 through 30). Officer

Hall left the residence to search the general area for the

suspect. (Tr. of E. page 37, lines 35 through 37). He

stationed himself southwest of 508 West 63rd Street and

observed a subject coming out of the wooded area from

the direction where Mr. Micke was killed. (Tr. of E. page

38 lines 1 through 24). After radioing for help he

followed this subject to 5020 Temple Street where he

found the subject under the house. (Tr. of E. page 39,

lines

sub)

rem:

Offi

(Tr.

Dep

mac

whi

40 1

Dey

stat

kitc

the

sho

Cr:

tha

boa

ball

vict

pet

stat

sta

acc

55

she

po

de

me

51

lines 9 through 40, page 40 lines 1 through 18). After the

subject, who Officer Hall identified as Petitioner was

removed from under the house he was searched by

i Officer Goode and a 22 pistol removed from his person.

(Tr. of E. page 40 lines 25 through 33).

Officer 1.R. Goode, Savannah Police

Department, testified that on August 11, 1967, that he

made a search of the Defendant and removed a 22 pistol

which he identified as the pistol in Court. (Tr. of E. page

40 lines 24 through 35, page 42 lines 1 through 10).

Detective B. W. Smith, Savannah Police

Department, testified that the petitioner made a

statement to him whereby he admitted being in the man’s

kitchen, the man saw him grabbed for him, he went out

the door, slammed the door, turned around and fired one

shot and ran. (Tr. of E. page 47 lines 36 through 41).

Dr. Charles Sullenger, Senior Toxicologist, State

Crime Laboratory, Chatham County, Georgia, testified

that he was given the bullet removed from the victim’s

body and the pistol taken from petitioner, made the

ballistics test and found that the bullet taken from the

victim’s body was fired from the pistol taken from

petitioner. (Tr. of E. page 50 lines 8 through 18).

Petitioner took the stand and in an unsworn

statement admitted going in the house of the victim but

stated that he fell back and. the gun discharged

3 accidentally. (Tr. of E. page 54, lines 33 through 40, page

1 55 lines 1 through 2).

; . ARGUMENT AND LAW :

1 Respondent contends that the death penalty

should be kept in force and effect and in support of this

position directs this Honorable Court to an old case

decided by the United States Supremze Court in the

matter of William Kemmler, 34 Lawyers Edition, page

519, 136, U.S., 436, 447, wherein the Court held:

“The provisions in reference to cruel and

unusual punishment taken from the well-known

Act of Parliament of 1688, entitled rehearsing

the various grounds of grievances and among

others, that ‘excessive bail hati: been required of

persons committed in criminal cases, to elude

a eit be pee EP a et EE

the benefit of the laws made for the liberty of

the subjects; and excessive fines have been

imposed; and illegal and cruel punishment

inflicted: it is declared that ‘excessive bail ought

not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed,

nor cruel and unusual punishment inflicted.”

The Court after declaring this Act of Parliament

went on further to state that the language used in the

Constitution of the State of New York, from which this

case came, was intended particularly to operate upon the

legislature of the State, and while the language of the

Constitution of the State of New York was similar to the

declaration of rights referred to, that the Courts of the

State of New York had the right to declare punishment

cruel and unusual. This to include burning at the stake,

crucifixion, breaking on the wheel or the like.

The Court in, In Re: Kemmler, Supra, further

stated:

“Punishments are cruel when they involve

torture or a lingering death; but the punishment

of death is not cruel, within the meaning of that

word as used in the Constitution. It implies

there something inhuman and barbarious,

something more than mere extinguishment of

life.”

The United States Supreme Court in the case of

Wallace Wilkerson vs. People of the United States in the

Territory of Utah, 25 Lawyers Edition, page 345, 99

U.S., page 130, in reference to the death penalty, stated:

“Difficulty would attend the effort to define

with exactness the extent of the constitutional

provision which provides that cruel and unusual

punishment shall not be inflicted; but it is safe

to affirm that punishments of torture such as

those mentioned by the commentator referred

to, and all others in the same line of unnecessary

cruelty, are forbidden by that Amendment to

the Constitution.”

In the Wilkerson case the Court was concerned

with the mode of punishment declared by the trial Court.

The Defendant was on the 14th day of December next

between the hours of 10:00 in the forenoon and 3:00 in

a

A.

3

a

t

e

r

Y

P

S

E

T

E

E

T

T

T

o

m

LL

a

n

p

he

Le

a a Ra TEE (Raper a Of Wah a I La i :

1 ig i Ra ea inn a a A RE a EE a ee dy Tat

the afternoon to be taken to a place certain and there

publicly shot until dead. The Court in its opinion stated:

“Cruel and unusual punishment is forbidden by

the Constitution, but the authorities referred to

are quite sufficient to show that the punishment

of shooting as a mode of executing the death

penalty for the crime of murder in the first

degree is not included in that category, within

the meaning of the Eighth Amendment.”

It can be seen that the question of cruel and

unusual punishment dates back as far as the eighteen

hundreds and the Supreme Court of these United States

even then recognized that there was difference in the

mode of executing the death penalty and even then they

drew a distinction between the humane death and

inhumane death such as torture or lingering death.

In the case of Trop vs. Dulles, 356 U.S. page 86,

2 Lawyers Edition 2, page 630, 78 Supreme Court 590,

the Court in an opinion delivered by Chief Justice Warren

joined in by Mr. Justice Black, Mr. Justice Douglas, Mr.

Justice Whitaker stated the following:

“At the outset, let us put to one side the death

penalty as an index of the Constitutional limit

on punishment. Whatever the argument may be

against capital punishment, both on moral

grounds and the terms of accomplishing the

purpose of punishment; and they are forceful,

the death penalty has been employed

throughout our history, and, in a day when it is

still widely accepted, it can not be said to violate

the Constitutional concept of cruelty. But it is

equally plain that the existence of all death

penalties is not a license to the Government to

devise any punishment short of death within the

limit of its imagination.”

“The exact scope of the constitution phrase

‘cruel and unusual’ has not been detailed by this

Court. But the basic policy reflected in these

words is firmly established in the

Anglo-American tradition of criminal justice.

The phrase in our Constitution was taken

directly from the English Declaration of Rights

Jans BYE

4 | of 1688, and the principle it represents can be

8 | traced back to the Magna Carta. The basic

| concept underlying the Eighth Amendment is

nothing less than the dignity of man. While the

State has the power to punish, the Amendment

stands to assure that this power be exercised

i within the limits of civilized standards.”

Ԥ The Trop case was decided March 31, 1958, {

B almost one hundred years after the Wilkerson case was ;

1 decided. The concept of the United States Supreme

41 Court with regard to the death penalty, in the late

eighteen hundreds and the middle nineteen hundreds has

not varied or changed. The concept of the death penalty

as being cruel and unusual punishment is only limited by

the execution of that death penalty. The Courts through

the years have consistently held that if the mode of oil

executing the death penalty is not that of our ancestors

T

C

E

S

T

ii

3 | from England, such as breaking on the wheel, torture, or

11 a slow and lingering death then it does not come within

11 the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States. If the mode of execution is a dignified means then

this type of execution has been accepted by our Courts as

| being within the frame work of our Constitution and

al should continue to’be within that frame work.

Throughout the years the Supreme Court has

not seen fit to remove from States the power or powers

to deal with criminals in the way they saw best provided

that it did follow civilized standards.”

The consent of not interferring with the States’

powers was exemplified in a decision handed down by

Mr. Justice Black, June 3, 1949, in the case of Samuel

Titto Williams vs. The People of the State of New York,

93 Lawyers Edition page 1337, 337 U.S., page 240

through 253. This is a case where the petitioner was

charged with murder and in a two-week trial was found

guilty and recommendation of life imprisonment was ¢

B forth coming from the Jury. Under New York state law

1 the Judge had the power and the right to either accept

1 the recommendation of the Jury or to impose a sentence

| he felt justified. In this particular case after the verdict of

the Jury, the trial Judge heard additional evidence as to

the past activities of the petitioner and sentenced him to

mi

eri. of RR RAL 5 «ov en ia

ip Ee Cl Sh SE A ,

EPR,

T

P

A

D

death. In giving his reasons for imposing the death

sentence the Judge discussed in open Court the evidence

upon which the Jury had convicted stating:

“That this evidence had been considered in the

light of information obtained through the

Court’s probation department and through other

sources.’

The case was appealed to the United States

Supreme Court for violation of due process in

that petitioner was not allowed to examine the

extra-ordinary evidence or to cross-examine the

witnesses who gave this evidence.

Mr. Justice Black in delivering the opinion of

this Court stated the following:

“To deprive sentencing Judges of this kind of

information would undermind modern

penological procedural policies that has been

cautiously adopted throughout the nation after

careful consideration and experimentation. We

must recognize that most of the information

now relied upon by Judges to guide them in the

intelligent imposition of sentences would be

unavailable if information were restricted to that

given in open court by witnesses subject to

cross-examination.”

Mr. Justice Black went on to say:

“The due process clause should not be treated as

a device for freezing the evidential procedure of

sentencing in the mold of trial procedure. So to

treat the due process clause would hinder if not

preclude all courts, state and federal, from

making progressive efforts to improve the

administration of criminal justice.”

It can be seen by Mr. Justice Black’s opinion in

the Wiliams case that states must have a right and the

power, within the confines of the Constitution of the

United States of America, to deal with criminal justice as

their Legislatures deem best.

In the case of Laurence Aikin Jackson vs. Fred

R. Dixon, 325 Federal 2d page 573, the Appellant in his

petition and on argument in the Ninth Circuit Court of

Appeals contended that the carrying out of the death

TTT SES LRT i] rem Caio ER < ED ba BA SR TL adi ak pa on Nn Si oS COR SR EIS Ce Tah

| penalty would deprive him of due process and also that it |

: would amount to cruel and unusual punishment in

violation of the Eighth Amendment of the United States

Constitution. In delivering the opinion, Circuit Judge

Duniway stated:

«Traditionally the death penalty has been

deemed an appropriate punishment for murder.” |

Circuit Judge Deniway went on to say: ;

“Here there is no suggestion as there was in !

certain of the cases above cited, that the method | a

of administering of penalty is cruel and unusual.

|

The contention is only that the penalty itself is :

of that character. This contention, in light of the

foregoing authorities we must reject.”

i

“Jackson’s arguments, which attack the penalty |

as incompatible with modern concepts of justice, would |

more properly be addressed to the California Legislature.

T

r

—

—

—

a

b

i

A

a

E

i

n

c

a

It is not for us to write our personal views on the matter, |

whatever they may be, into the Constitution. We hold 4

that if the State is free to find Jackson guilty of murder pi {

| in the first degree, as Leland makes clear that it was in i

Hi this case, it does not violate the Eighth Amendment,

- made applicable to it by the Fourteenth Amendment, by

| imposing the death penalty upon him.”

I think Judge Duniway has made clear the

position which we believe should be taken by this

H Honorable Court, that position being that regardless of

our personal feelings toward the death penalty and

regardless of whether we feel that a person deserves or

does not deserve ultimate punishment that we must

H confine ourselves to the question of whether or not the

death penalty is, or is not, prohibited by the Eighth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of

America. We think it goes without saying that any type

of torture or lingering death that is calculated to put a

person in misery before he dies, is the type of death

penalty outlawed and prohibited by the Eighth

; Amendment of the Constitution. Any type of death

4 penalty, such as death by electrocution, by being shot, or

by being put to death by gas, is the type of execution

that is known to civilized men and is a type of execution

that is constitutionally protected by the Eighth

PR

E

S

S

E

E

n

eS

ER

I

I

A

i

S

W

a

,

: Si eek Ge ok SU RA Sed ihe UCR | LES aaa Ad

Amendment and has been constitutionally protected by

the United States Supreme Court in former years.

We find it difficult in 1971 to say that death by

electrocution is wrong now but was right in the year

1958 and was right in 1879. The offense of murder, as

the offense of rape, was wrong in 1879, it was wrong in

1958, and is wrong in 1971. The punishment for those

crimes has been the same for almost one hundred years

and we can not see now where the punishment should be

deemed cruel and unusual.

Petitioner contends that the death penalty 1s

cruel and unusual punishment and therefore should be

eliminated because it violates the Eighth Amendment of

the Constitution of the United States of America.

Respondent respectfully directs the Court’s

attention to a case decided by this Honorable Court on

the 13th day of January, 1947, which was a cas of State

of Louisiana ex rel. Willie Francis, Petitioner, vs. E. Al

Resweber, Sheriff of the Parish of St. Martin, Louisiana,

et al., 329 U.S. 459 through 481, 91 Lawyers Edition

page 422, wherein petitioner Francis was convicted of the

offense of murder and sentenced to die in the electric

chair on the 3rd day of May, 1946, pursuant to a death

warrant. On the 3rd day of May, 1946, Petitioner was

prepared for execution and sat in the electric chair and

the Executioner threw the switch but, presumably,

because of some mechanical malfunction, the current did

not come On and dealth did not result. Therefore

petitioner was removed from the electric chair and a new

death warrant issued by the Governor of Louisiana fixing

the date of execution for May 9, 1946.

After a refusal of an application to the Supreme

Court of the State of Louisiana, petitioner brought his

case before the United States Supreme Court alleging a

denial of due process and also alleging cruel and unusual

punishment. The denial of due process consisted of the

violation of the Fifth Amendment which was double

jeopardy and the cruel and unusual punishment consisted

of the violation of the Eighth Amendment, cruel and

unusual punishment, all as applied to the State of

Louisiana through the Fourteenth Amendment.

oo

r

r

E

—

—

—

|

H

i

t

ih

if

£

£1

i

It

£3

:

PR

GP

IC

r

N

E

C

TE

C

P

In announcing the decision, which was joined in

by the Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Black and Mr. Justice

Jackson, Mr. Justice Reed stated the following:

“Our minds rebel against permitting the same

sovereignity to punish an accused twice for the

same offense ... But where the accused

successfully seeks review of a conviction, there is

no double jeopardy upon a new trial. ... Even

where a state obtains a new trial after conviction

because of errors, while an accused may be

placed on trial a second time, it is not the sort of

hardship to the accused that is forbidden by the

Fourteenth Amendment ...

As this is a prosecution under State law, so far as

double jeopardy is concerned, the Palco case is decisive.

For we see no difference from a constitutional point of

view between a new trial for error of law at the instance

of the State that results in a death sentence instead of

imprisonment for life and the execution that follows

because of failure of equipment. When an accident, with

no suggestion of malevolence, prevents the

consummation of a sentence, the State’s subsequent

course in the administration of its criminal law is not

affected on that account by any requirement of due

process under the Fourteenth Amendment. We find no

double jeopardy here which can be said .to amount to a

denial of federal due process in the proposed execution.”

“We find nothing in what took place here which

amounts to cruel and unusual punishment in the

Constitutional sense. The case before us does not call for

an examination into any punishment except that of

death...” The traditional humanity of modern

Anglo-American law forbids the infliction of unnecessary

pain in the execution of the death sentence. Prohibition

against the wanton infliction of pain has come into our

law from the Bill of Rights of 1688. The identical words

appear in our Eighth Amendment. The Fourteenth

Amendment would prohibit by its due process clause

execution by a state in a cruel manner.

“Petitioner’s suggestion is that because he once

underwent the pyschological strain of preparation for

electrocution, now to require him to undergo this

TATE PR TRS

I —————— EL Lk SL a Al

ER eT CA 2

> R

E

N

N

,

2

—-

preparation again subjects him to a lingering or cruel and

unusual punishment. Even the fact that petitioner has

already been subjected to a current of electricity does not

make his subsequent execution any more cruel in the

constitutional sense than any other execution. The

cruelty against which the Constitution protects a

convicted man is cruelty inherent in the method of

punishment, not the necessary suffering involved in any

method employed to extinguish life humanely. The fact

that an unforeseeable accident prevented the prompt

consummation of the sentence cannot, it seems to us, add

an element of cruelty to a subsequent execution. There is

‘no purpose to inflict unnecessary pain nor any

unnecessary pain involved in the proposed execution. The

situation of the unfortunate victim of this accident is just

as though he had suffered the identical amount of mental

anguish and physical pain in any other occurrence, such

as, for example, a fire in the cell block. We cannot agree

that the hardship imposed upon the petitioner rises to

that level of hardship denounced as denial of due process

because of cruelty.”

We can see by the Francis case (Supra) that the

Supreme Court of the United States still upheld the

theory that unless the type of execution to effect the

death penalty is that of torture or lingering death then,

even though the malfunction of the device used occurred

to effect that type of punishment failed, it still is not

excluded by the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution.

Surely this Honorable Court would agree that the Francis

case (Supra) would come close, if not the closest, to

meeting a definition of a lingering death. Can this Court

say that to prepare a person for death, see him upon the

instrument that would cause his death, and let him

experience all the fears of death including meeting the

Supreme Being that created him, whether he stands in his

favor or not, and death not resulting and then have this

person returned at a later date to this instrument for the

purpose of accomplishing the end that theretofore had

failed, would not come within a lingering death? This was

answered by the highest Court of our land in the year

1946, in the negative. Can this Honorable Court, as

presently constituted, sixteen years later, say that death

k

¥

5

§

|

I

O

C

l

a

a

m

i

3

ol

se

um

ai

t

S

u

a

E

by electrocution in a penal institution, in the sovereign

state of Georgia, now constitutes cruel and unusual

punishment and is a type of punishment prohibited by

the same Eighth Amendment of the United States

Constitution that existed in 1946?

As the Court can well see we have a young

couple with five children in the safety of their home at

2:30 AM., on August 11, 1967. The victim, Mr. Micke

believing his child is sleep walking, leaves his bed, and his

wife and goes into the kitchen to find not his child but an

intruder. In an effort to protect his wife and five children

he attempted to stop this intruder whereupon Petitioner

runs out, slamming the door and fires at Mr. Micke.

Petitioner says the penalty of death for this murder is too

cruel and too unusual and therefore should be prohibited

by the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States of America. I wonder what Mrs. Micke,

who is now left alone to rear five children, thinks of what

he did to her husband at 2:30 A.M., on August 11, 1967?

I wonder if Petitioner’s battery of Attorneys would say

that William Henry Furman committed an act of cruel

and unusual punishment on William Joseph Micke, Jr.? I

wonder if they would say that William Henry Furman

committed an act of cruel and unusual punishment on

Mrs. Micke and her five young children? I am sure they

think this is a deliberate crime and they grieve for the

widow and fatherless: children but now say that it is not

right to take the life of a burglar, murder, who left the

widow and five fatherless children. We don’t accept the

view taken by Petitioner or his Attorneys. We think the

crime that he has committed is senseless, hideous and one

for which he should be given the ultimate punishment

which is death by electrocution.

We have a person before this Court, who broke

into the house where a mother and father and five

children lived. After being discovered by the head of the

household he ran, but when he was outside on that porch

after having slammed the door between Mr. Micke and

himself, he wasn’t content with just running away, he

turned around and in a wanton, wilful disregard for

human life he fired that 22 pistol through the door and

into Mr. Micke’s chest causing the death of Mr. Micke.

EE -e. et tM dE Er DT ah rE A YY OE ey a PW LW TI NTT PO SBN TS RE TAR ; RETR ie i =I

ie fC NaF AA cep

AT

—

E

T

—

ha

ri

E

E

A

C

I

Can this Court now say that the crime committed was

not a crime that deserved the death penalty? Throughout

our legal history and throughout Biblical history man has

invoked the death penalty, the Church has invoked the

death penalty. The death penalty in our United States has

been upheld as cited to this Court on numerous

) occasions. It has been guaranteed the protection by the

| Eighth Amendment for numerous years. Provided that it

is not a torturious death or a lingering death. Our Bible

1 says: “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, a life

| for a life.”

Our Bible says: “Render unto God the things

that are God’s and to Ceasar the things that are Ceasar’s.”

We take the position that the State of Georgia has seen fit

to invoke the death penalty; that our Legislature has seen

"fit to allow this Statute to remain on the books of the

State of Georgia and now we are only rendering to Ceasar =

the things that are Ceasar’s.

Ed

Petitioner in this case, as the petitioner in the

case of Lucious Jackson, has made the same over-tones of

racial discrimination. Let it be well understood by this E13

Court that this State stands not for discrimination :

because of race, color or creed, but it stands for justice.

Should it be a person of color that killed Mr. Micke or

should it have been a white man and had he received the

death penalty as petitioner did, this writer and this State

would be as strong in favor of that execution being

carried out as they are in this execution being carried out.

This writer has never experienced an intruder in this

house in the middle of the night and hopes he never will,

I think there is nothing more terrifying than to be

awakened in the middle of the night and find an outsider

in my house.

We contend that when Petitioner broke into the

victim’s house he was armed with a pistol; we believe that

he carried that pistol for the express purpose that if he

was detected he would use that pistol to accomplish his

end, whether it meant the extinguishment of life or not.

We think the crime that he has committed deserved the

death penalty; deserved the State taking his life, as he

took the life of William Joseph Micke, Jr.

a

F

E

So

E

A

T

—

R

n

d

iri

nd

E

P

A

[

t

e

g

s

B

R

R

{

i

t

§

|

{

H

|

t 3

We ask only that this Honorable Court decide

this case on the same legal basis that past Supreme Courts

have decided this question.

Death by electrocution is not that type of

torture or lingering death that is prohibited by the Eighth

Amendment of our Constitution. It is not that type of

death which shocks the senses of civilized men. It is that

type of punishment that has been sanctioned by this

Court for almost one hundred years. It is that type of

| punishment that has been sanctioned by the English

Parliament for hundreds of years.

We. respectfully request that this Court affirm

the decision of Georgia Supreme Court and uphold the

death penalty as a proper means for punishment.

-

a ; ~~ ~~ f

2 Ls

|

05h YA]

I

DISTRICT , ATTORNEY, EASTERN

| JUDICIAL y

F GEORGIA

ArT

i

4 or wy i 2 Cf

i

‘EF / ASSISTANT DISTRICT

| ATTORNEY,

i

EASTERN JUDICIAL CIRCUIT OF

I GA.

1 Post Office Address:

| : 402 Courthouse Building

| Savannah, Georgia 31401

F

A

A

R

R

A

BI

SA

S

i

»,