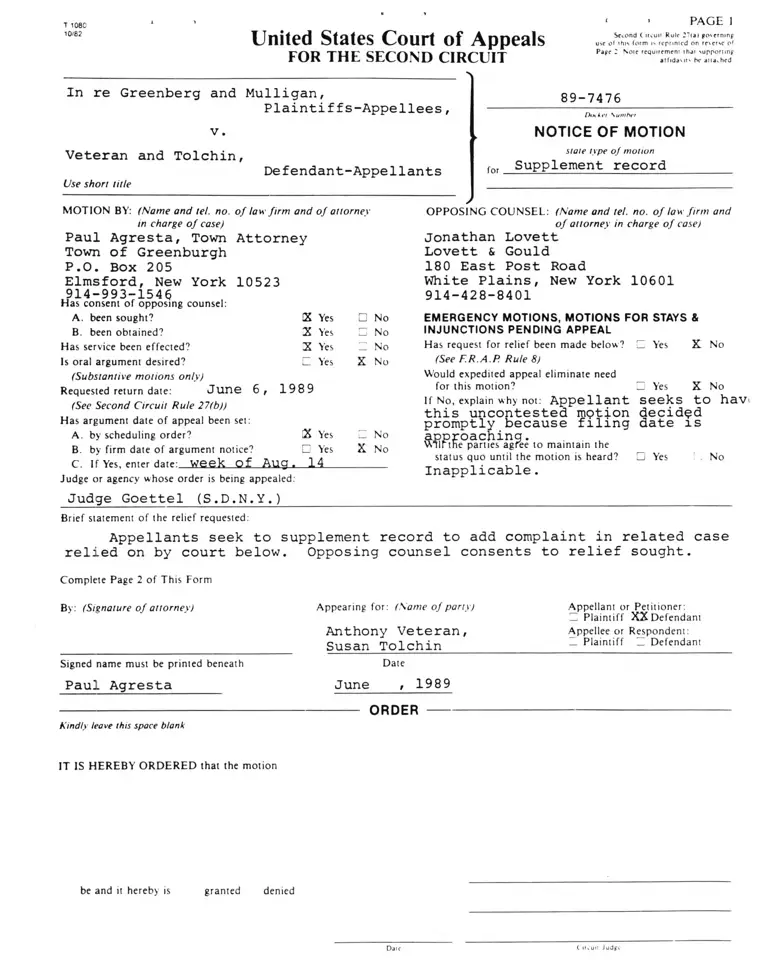

Greenberg v. Veteran Notice of Motion for Supplement Record

Public Court Documents

June 8, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Greenberg v. Veteran Notice of Motion for Supplement Record, 1989. a8f76558-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a606e70e-4a04-49d5-822f-6378d04f738c/greenberg-v-veteran-notice-of-motion-for-supplement-record. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

T 108C

10/82 United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

« 1 P A G E I

Second C ircu it Rule 2 "(a i governing

use o f this form is reprim ed on reverse of

Page 2 Note requiremen! that supporting

a ffidav its he attached

In re Greenberg and Mulligan,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

Veteran and Tolchin,

Defendant-Appellants

Use short title

_________89-7476________

D t x i e i \ um ber

NOTICE OF MOTION

slate type o f motion

for Supplement record

MOTION BY: (Name and tel. no. o f taw firm and o f attorney

in charge o f case)

Paul Agresta, Town Attorney

Town of Greenburgh

P.O. Box 205

Elmsford, New York 10523

914-993-1546Has consent of opposing counsel:

A. been sought? X Yes □ No

B. been obtained? X Yes Z j No

Has service been effected? X Yes ' ; No

Is oral argument desired? L_2 Yes X No

(Substantive motions only)

Requested return date: June 6 , 19 8 9

(See Second Circuit Rule 27(b))

Has argument date of appeal been set:

A. by scheduling order? X Yes Z No

B. by firm date of argument notice? □ Yes X No

C. If Yes, enter date: W e e k O f A u g .__ 1 4 ____________

Judge or agency whose order is being appealed.

7

OPPOSING COUNSEL: (Name and tel. no. o f law firm and

o f attorney in charge o f case)

Jonathan Lovett

Lovett & Gould

180 East Post Road

White Plains, New York 10601

914-428-8401

EMERGENCY MOTIONS, M OTIONS FOR STAYS &

INJUNCTIONS PENDING APPEAL

Has request for relief been made below? Z Yes X No

(See F .R .A .P Rule 8)

Would expedited appeal eliminate need

for this motion?

If No, explain why not: Appellant this uncontested motion promptly because filingapproaching.

Wilrthe parties agree to maintain the

status quo until the motion is heard?

Inapplicable.

□ Yes X No

seeks to hawdecideddate is

□ Yes No

Judge Goettel (S.D.N.Y.)______________________________________________________

Brief statement of the relief requested:

Appellants seek to supplement record to add complaint in related case

relied on by court below. Opposing counsel consents to relief sought.

Complete Page 2 of This Form

By: (Signature o f attorney)

Signed name must be printed beneath

Paul Agresta______

Kindly leave this space blank

Appellant or Petitioner:

Z Plaintiff XX Defendant

Appellee or Respondent:

_ Plaintiff Z Defendant

Date

June , 1989

----- ORDER ----

Appearing for: (Name o f party)

Anthony Veteran,

Susan Tolchin

IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that the motion

be and it hereby is granted denied

Date C ircu ii Judge

PAG! 2

Previous requesis for similar relict and disposit ion: Appellants sought the Same relief in a

motion dated May 17, 1989, filed with this Court. The Clerk s office

rejected that motion by letter dated May 24, 1989 because it was

included with a motion to consolidate this appeal with a forthcoming

mandamus petition.

Statement of the issuc(s) presented b> this motion: Should record on appeal be supplemented to

include complaint in a related case relied on by the court below.

Brief statement of the facts {with page references to the moving papers): Def endantS-Appe 1 lantS removed

this case from state court under provisions conferring jurisdiction in

certain civil rights actions and in federal question cases. The court

below held that civil rights jurisdiction was lacking, and that it^should

abstain from exercising federal question jurisdiction. Having decided

to abstain, the court remanded. (Agresta Affidavit 1111 8-10)

Summarv of the argument (with page references to the moving papers):This case was one of two related cases below. The court below relied

on the complaint in the related case for background facts and referred

to it in its decision. (Agresta Affidavit 1111 7, 12) Thus, that

complaint should be readily available to this Court on this appeal.

Opposing counsel has consented to the relief sought.

Because there is no opposition, and because joint appendix and

Appellants brief are due June 19, 1989, Appellants apply for a

June 6, 1989 return date.

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

______________________________________________ _

In the Matter of the Application

of MYLES GREENBERG and FRANCES M. :

MULLIGAN,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

Docket No. 89-7476

AFFIDAVIT

-against-

ANTHONY F. VETERAN and

SUSAN TOLCHIN,

Defendants-Appellants.

__________________________________________ _

STATE OF NEW YORK )) ss. :

COUNTY OF WESTCHESTER )

PAUL AGRESTA, being sworn, states:

1. I am Town Attorney for the Town of Greenburgh,

counsel for Defendants-Appellants Anthony F. Veteran (the

"Town Supervisor") and Susan Tolchin. ^ I submit this

affidavit in support of the Town Supervisor's motion to

supplement the record on this appeal to include the complaint

in a related action, Jones v. Deutsch, 88 Civ. 7738 (GLG)

(S.D.N.Y.), which was also before the Court below, and which

the Court below considered in connection with the order

Susan Tolchin, the Town Clerk, is a nominal party, whose

interests are aligned with those of the Town Supervisor.

For simplicity's sake, I will refer only to the Town

Supervisor.

2

appealed from. Opposing counsel has consented to the relief

sought. For this reason — and because the dates for filing

the record (June 12) and the joint appendix and Appellants'

brief (June 19) are rapidly approaching — I respectfully ask

that the Court hear this motion on a shorter time schedule

than would ordinarily be followed.

2. This appeal arises from an order of the United

States District Court for the Southern District of New York,

which remanded a removed proceeding to the New York State

Supreme Court. (Annexed Exhibit 1) Part of the order below

held that there was no basis for removal, and it is appeal-

able as of right under a statutory provision applicable only

to the remand of civil rights actions. See 28 U.S.C. §§

1443 and 1447(d).

Summary of the Case

3. The District Court aptly captured the essence

of the controversy underlying the litigation:

This case, at its core, is unmistakably a product

of the "NIMBY Syndrome" — i.e., that syndrome_

triggered by proposals to locate prisons, public^

housing, waste facilities, and other such community

additions usually perceived by the targeted commu

nity as undesirable, the abiding characteristic of

which is to ensure that the proposed facility be

placed somewhere if it must but "Not In My Back

Yard." The public project at issue here is the

proposed construction of emergency housing for the

homeless. (Exhibit 1, pp. 2-3; emphasis in origi

nal)

3

4. Announced in early 1988, the proposed shelter

is part of a County of Westchester/Town of Greenburgh effort

to house homeless families with children — overwhelmingly

members of racial minorities. Community resistance developed

immediately; it includes an effort to assume control of the

development site by incorporating a new village, pursuant to

the New York Village Law. As a leading proponent of the new

village has said; "We'll go ahead with secession and take a

nice piece of taxable property with us." (Annexed Exhibit 2,

1 23)

5. Before the secession could proceed, however,

state law required the Town Supervisor to consider the

petition to incorporate. After studying the proposed village

map and holding a hearing, the Town Supervisor concluded that

"[i]n the entire 30 years during which I have held elective

office I have never seen such a blatant and calculated

attempt to discriminate" on grounds of race. (Annexed

Exhibit 3, p. 2) Thus, finding a racially discriminatory

impact, as well as several other state law deficiencies in

the petition to incorporate, the Town Supervisor rejected the

attempt to secede.

6. Appellees thereupon filed this proceeding in

the Westchester County Supreme Court, pursuant to Article 78

of the New York Civil Practice Law and Rules. The Article 78

petitioners seek to overturn the Town Supervisor's decision,

4

alleging, among other claims, that the New York Village Law

does not authorize rejecting an incorporation effort on

grounds of invidious discrimination.

Proceedings in the District Court

7. On November 1, 1988, an alliance of community

blacks, homeless persons with families, the White

Plains/Greenburgh branch of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, Inc. and the National Coali

tion for the Homeless filed suit in the Southern District of

New York against proponents of the secession, and the Town

Supervisor. That action, Jones v. Deutsch, 88 Civ. 7738

(GLG) (Exhibit 2), alleges civil rights conspiracy claims

arising under 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3). It also seeks a declara

tory judgment affirming the Town Supervisor's right and

obligation to reject the incorporation petition. Upon its

filing, the case was assigned to Judge Goettel.

The Filina and Removal of this Case

8. A few weeks after Jones was filed, the Town

Supervisor rendered his decision. (Exhibit 3) This state

court Article 78 proceeding followed, and the Town Supervisor

filed a petition removing it to the Southern District of New

5

York. Upon removal, the Article 78 proceeding was assigned

2 /to Judge Goettel as a case related to Jones.— '

9. As authority for removal, the Town Supervisor

relied in part on the "refusal clause" of 28 U.S.C.

§ 1443(2), a provision applicable to civil rights actions.

In pertinent part, the statute provides that:

Any of the following civil actions . . . may be

removed by the defendant to the district court of

the United States for the district and division

embracing the place wherein it is pending:

* * *

(2) For any act under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights, or for

refusing to do any act on the ground that it would

be inconsistent with such law.

The Town Supervisor also invoked federal question removal

jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1441(b), based on an Article

78 proceeding claim that he had violated the secessionists'

First Amendment rights. Section 1441(b), in relevant part,

provides that:

Any civil action of which the district courts have

original jurisdiction founded on a claim or right

arising under the Constitution, treaties or laws of

2/ Besides the Town Clerk of Greenburgh, hundreds of

opponents of secession are also named respondents in the

Article 78 proceeding. Some of these respondents

(including the plaintiffs in Jones) joined the removal

petition below. Although not formal parties on these

appellate proceedings, these additional removing parties

are aligned in interest with the Town Supervisor.

6

the United States shall be removable without regard

to the citizenship or residence of the parties.

The Remand Decision Below

10. The Article 78 petitioners did not seek to

remand. However, the District Court sua sponte directed the

parties to address whether removal was appropriate and

whether the Court should abstain under the doctrine of

Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Co., 312 U.S. 496

(1941). After oral presentations and written submissions,

the Court below issued its decision. (Exhibit 1) Remanding

the case, in summary, the Court below: (a) rejected removal

under the refusal clause of § 1443(2); and (b) as to federal

3/question removal, invoked the Burford abstention doctrine.

11. The Town Supervisor has filed a notice of

appeal from that part of the District Court's order rejecting

removal under the refusal clause of § 1443(2). That appeal

is authorized by 28 U.S.C. § 1447(d), which provides that a

remand order in a case which "was removed pursuant to section

1443 of this title shall be reviewable by appeal or other

wise." The Town Supervisor also intends to file ^ petition

for a writ of mandamus to review that part of the order below

3/ See Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U.S. 315 (1943) .

7

abstaining on Burford grounds. See Corcoran v. Ardra Ins.

Co.. 842 F .2d 31 (2d Cir. 1988).

The Relief Sought On This Motion:

Supplementing the Record to Include the Jones Complaint

12. The relief sought is in the nature of house

keeping. We ask leave to supplement the record to the extent

of including the complaint in Jones v. Deutsch, 88 Civ. 7738

(GLG) (Exhibit 2). That complaint was before the District

Court since the two matters here are related. The Court

below referred to Jones in its remand decision (Exhibit 1,

pp. 4-5, 6 & fn. 3, 29 & fn. 11), and plainly relied in part

on the allegations in that case for background facts that

appear in its decision. In these circumstances, that same

pleading should be before this Court, conveniently available,

on the Town Supervisor's appeal.

13. To reiterate, opposing counsel does not object

to our application, and the record must be filed by June 12,

1989. Our appeal papers also are due by June 19, 1989.

Accordingly, I respectfully request that our motion be

promptly heard by the Court, and granted.

Paul Agresta

Sworn to before me this

____ day of June 1989.

Notary Public

Exhibit 1

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

In the Matter of the Application :

of MYLES GREENBERG and FRANCES M.

MULLIGAN, :

Petitioners, : 89 Civ. 0591 (GLG)

-against- : O P I N I O N

ANTHONY F. VETERAN, et al., :

Respondents. :

A P P E A R A N C E S :

Counsel for Petitioners:

LOVETT & GOULD

180 East Post Road *

White Plains, New York 10601

By: Jonathan Lovett, Esq.

Of Counsel

Counsel for Respondents Anthony F. Veteran and

Susan Tolchin:

PAUL AGRESTA, ESQ.

Town Attorney

Town of Greenburgh

P.O. Box 205

Elmsford, New York 10523

Counsel for Respondents Keren Developments, Inc.

and Robert Martin Company:

CUDDY & FEDER

90 Maple Avenue

White Plains, New York 10601

By: Ruth E. Roth, Esq.

Of Counsel

Counsel for Respondent Ruth E. Roth (Pro Se):

RUTH E. ROTH, ESQ.

90 Maple Avenue

White Plains, New York 10601

Counsel for Respondents Anita Jordan, April Jordan,

Latoya Jordan, Anna Ramos, Lizette Ramos,

Vanessa Ramos, Gabriel Ramos, Thomas Myers,

Lisa Myers, Thomas Myers, Jr., Linda Myers\

Shawn Myers, and National Coalition for the Homeless:

-and-

Local Counsel for Respondents Yvonne Jones, Odell A.

Jones, Melvin Dixon, Geri Bacon, Mary

Williams, James Hodges and National

Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, Inc.

White Plains/Greenburgh Branch:

PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, WHARTON & GARRISON

1285 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10019

By: Jay L. Himes, Esq.

Cameron Clark, Esq.

Melinda S. Levine, Esq.

William N. Ger=»on, Esq.

Of Counsel * *

Counsel for Respondents Yvonne Jones, Odell A. Jones,

Melvin Dixon, Geri Bacon, Mary Williams/

James Hodges and National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People, Inc.

White Plains/Greenburgh Branch:

GROVER G. HANKINS, ESQ.

NAACP, Inc.

4805 Mount Hope Drive

Baltimore, Maryland 21215-3297

By: Robert M. Hayes, Esq.

Virginia G. Shubert, Esq.

COALITION FOR THE HOMELESS

105 East 22nd Street

New York, New York 10010

Julius L. Chambers, Esq.

John Charles Boger, Esq.

Sherrilyn Ifill, Esq.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

Andrew M. Cuomo, Esq.

12 East 33rd Street - 6th Floor

New York, New York 10016

Of Counsel

G O E T T E L , D.J.:

Federalism is a concept whose vitality is perceived by some

to be rather fluid. There are those, for example, who believe it

worthy only of lip service and that, as a general proposition, if

a matter may be brought in a court it may be brought in federal

court. To that thinking, the retort is quite simple: "federal

courts are courts of limited jurisdiction."1 Still others, while

cognizant of the notion's existence, perceive its recognition as

"seasonal" in nature, going in and out of style with the

philosophical predilections of a given administration and the

quantity and temperament of its judicial appointments. As to that

point of view, we note only that the document serving as

federalism's source is entitled to greater deference than the whims

* •

of current majoritaxian thinking.

There are those, however, who share our view that federalism

is a neutral constant of federal jurisprudence, the necessary

product of our dualist system. The proceeding before us is rife

with federalist implications, and it is our recognition of and

respect for those concerns which shapes and guides our handling of

the matter.

New York has provided an avenue for judicial review of state

and municipal administrative action under N.Y. Civ. Prac. L. & R.

("NYCPLR") §§ 7801-06 (McKinney 1981 & Supp. 1989), the so-called

Article 78 proceeding. Judicial review under these provisions

1 Owen Equip. & Erection Co. v. Kroger. 437 U.S. 365, 374

(1978) .

1

generally is limited to determining whether the official's actions

constituted an abuse of discretion, were unsupported by sufficient

evidence, or were contrary to existing law. id. at § 7803.

Although an Article 78 proceeding cannot be initiated in federal

court, Chicaqo,— Rock Island & Pacific R.R. Co. v. Stude. 34 6 U.S.

574, 581 (1954) , it is contended that such a proceeding nonetheless

may be removed here so long as a federal question is asserted in

the Article 78 petition — apparently no matter how tangential or

attenuated or if the respondents allegedly were acting pursuant

to federal law protecting equal rights — even if that law

parallels similar state law mandating like action.

As will become clear, we harbor certain reservations as to

this interest in "federalizing'; Article 78 proceedings generally

and this proceeding in particular. Fortunately, at least in this

case a solution presents itself. Animated chiefly by due respect

for the principles of comity and federalism that serve as the

essential bedrock for healthy federal-state relations, we find that

abstention is proper in this case and, consequently, we remand the

matter sua sponte to the court from whence it originated and

belongs (in our view) — the New York Supreme Court for the County

of Westchester. I.

I. BACKGROUND

This case, at its core, is unmistakably a product of the

NIMBY Syndrome" i.e., that syndrome triggered by proposals to

locate prisons, public housing, waste facilities, and other such

2

community additions usually perceived by the targeted community as

undesirable, the abiding characteristic of which is to ensure that

the proposed facility be placed somewhere if it must but "Not In

My BackYard." The public project at issue here is the proposed

construction of emergency housing for the homeless.

In January of last year, the Town of Greenburgh, in

conjunction with the County of Westchester, proposed to build

emergency or "transitional" housing to accommodate 108 homeless

families on land owned by the County in the Town. The proposed

developer is West H.E.L.P., Inc. ("West HELP"), a not-for-profit

corporation formed for the express purpose of constructing housing

for the homeless of Westchester County. It is generally

acknowledged that the vast majority of homeless people who would* «

gualify for residence in the West HELP project are minorities,

specifically blacks.

In response to that announcement, a number of Greenburgh

residents living in the area immediately surrounding or adjacent

to the proposed site formed the Coalition of United Peoples, Inc.

("COUP"). COUP'S purpose, de facto or otherwise, is to coordinate

opposition to the West HELP project and, most importantly, to

ensure that the project is not constructed in COUP'S backyard. As

part of those efforts, COUP began a drive under N.Y. Village Law

§§ 2-200 to 2-258 (McKinney 1973 & Supp. 1989) (the "Village Law")

to incorporate an area encompassing the proposed West HELP project

as a separate village to be denominated the Village of Mayfair

3

Knollwood.2 On September 14, 1988, pursuant to section 2-202 of

the Village Law, COUP presented an incorporation petition to

Greenburgh Town Supervisor Tony Veteran, whose responsibility it

is in the first instance to determine whether the petition complies

with the requirements of the Village Law. In accord with section

2-204 of the Village Law, a public hearing on the matter was

conducted on November 1 at which oral testimony was received. Town

Supervisor Veteran then adjourned conclusion of the hearing until

November 21 for the sole purpose of entertaining written comments

on the petition.

Also on November 1, and prior to any decision by Town

Supervisor Veteran on the merits of the petition, various citizens

of the Town of Greenburgh, a nujnber of homeless people living in♦ «

Westchester County," the National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, and the National Coalition for the Homeless

joined forces as plaintiffs in a federal action in this court

against COUP, certain of its members, and Town Supervisor Veteran.

Jones v. Deutsch. No. 88 Civ. 7738 (GLG). The complaint alleges,

inter alia , a civil rights conspiracy amongst the named defendants

pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1985, the ostensible purpose of which is

to deprive plaintiffs of voting, housing, and emergency-shelter

Just how incorporation of the proposed village would

obstruct construction of housing for the homeless on what is

admittedly County-owned property is not entirely clear to us.

Presumably, COUP believes that leaders of the newly formed village

would be able to so bog down and delay approval of necessary zoning

and other permits that pursuit of the project would become

undesirable.

4

rights grounded in federal and state law. Plaintiffs also sought

a declaratory judgment directing that Town Supervisor Veteran

reject the allegedly discriminatory incorporation petition,

contending that such a result would be consistent with the proper

execution of his oath of office. The COUP defendants moved to

dismiss that action on various grounds (among them ripeness and

standing). The motion was adjourned sine die pending determination

of the instant matter, which had been removed to this court during

the interim.

Town Supervisor Veteran, apparently not in need of a federal

court order controlling his actions, issued a decision on December

1, 1988 rejecting COUP'S incorporation petition (the "December 1

Decision"). In a carefully worded opinion, six specific grounds* •

were enumerated as the bases for the decision:

(1) the proposed boundaries are not described with "common

certainty," as required by section 2-202 of the Village Law;

(2) the proposed boundaries, where ascertainable, evidence an

intent to discriminate and are gerrymandered to exclude black

residents, rendering the petition violative of "rights granted by

the federal and state constitutions";

(3) the petition was prepared for the invidious purpose of

"preventing the construction of transitional housing for homeless

families," rendering it violative of "rights granted by the federal

and state constitutions";

(4) substantial petition signatures were obtained under false

pretenses;

5

(5) substantial petition signatures are irregular; and

(6) numerous Town residents (particularly newer residents)

are not identified as would-be inhabitants of the proposed village,

as required by section 2—202 of the Village Law.

Under the express provision of section 2-210 of the Village

Law, review of a town supervisor's decision on an incorporation

petition may be had only through an Article 78 proceeding on

grounds that the decision "is illegal, based on insufficient

evidence, or contrary to the weight of evidence." Eleven days

after Town Supervisor Veteran issued his decision on the COUP

petition, two COUP members instituted an Article 78 proceeding in

New York Supreme Court challenging that decision. On January 30

of this year, the respondents in that proceeding filed a petition* * «

for removal in the Southern District of New York, designating the

matter as related to the pending Deutsch action.

Urging that the December 1 Decision be reversed and the

petition to incorporate the Village of Mayfair Knollwood be

sustained, the Article 78 petition sets forth five specific bases

allegedly supporting the relief requested:

(1) since section 2-206(3) of the Village Law requires that

testimony offered at a petition hearing "must be in writing" and

that the "burden of proof shall be on objectors," and since only

oral testimony was taken at the November 1 hearing, Veteran's 3

3 Principally as a result of that action, an̂ amended

complaint was filed in the Deutsch action which, inter alia, drops

defendant Veteran as a member of the alleged civil rights

conspiracy.

6

actions were contrary to the requirements of the Village Law and

thus illegal or, alternatively, his decision was not supported by

sufficient evidence?

(2) since a town supervisor's authority under section 2-206

of the Village Law to review incorporation petitions allegedly is

strictly ministerial (i.e., limited to assessing the validity of

only those objections related to petition requirements set forth

by the statute), and because the statute does not provide for an

examination of or inquiry into the petitioners' intent, Veteran's

decision is illegal because it went beyond the scope of his

ministerial authority or, alternatively, his perceptions of

discriminatory intent are not supported by sufficient evidence;

(3) since under section 2-206 of the Village Law the sole* •

evidence Veteran purportedly was allowed to consider was that

adduced at the November 1 public hearing and reduced to writing,

his reliance on material received during the period he allowed for

further written comment between November 1 through 21 renders his

decision illegal or, alternatively, contrary to the weight of the

objecting evidence received at the November 1 hearing;

(4) since no objections allegedly were filed with respect to

the means by which petition signatures were gathered or as to the

sufficiency of the list of regular inhabitants, Veteran's decision

is illegal or is unsupported by sufficient evidence; and

(5) since the petitioners' opinions, motives, or intentions

are matters allegedly protected by the First Amendment of the

7

United States Constitution, Veteran's decision violates those

rights.4

Freely expressing our doubt as to the propriety of removal in

this case, a conference in chambers was scheduled to discuss, inter

alia. (i) whether, as a general proposition, Article 78 proceedings

may be removed to federal court, (ii) if so, whether removal in

this case is justified under either of the pertinent statutory

provisions invoked, to be discussed infra. and (iii) whether,

assuming the instant proceeding can be removed, principles of

abstention dictate that we stay our hand or dismiss in deference

to a state proceeding addressing some or all of the issues raised.

Memoranda and letters on these subjects were submitted to the

court prior and subsequent to tĥ e. scheduled conference. Generally,

all parties are of the belief that the Article 78 proceeding at bar

could be and properly was removed, and only counsel for the Article

78 petitioners expressed any concern as to possible abstention

implications. In sum, it is readily apparent that the parties are

content to be before this court and believe that this court is the

proper forum in which to address the Article 78 matter; no motion

to remand is contemplated. Notwithstanding this state of affairs,

but consistent with the primacy of this court's obligation to

protect its jurisdiction, the court has engaged in its own research

4 As discussed infra, we add only that it appears certain

of the questions bearing on the legality of the procedures employed

and whether Veteran exceeded the scope of his authority under the

Village Law are unsettled questions of New York law (indeed, from

what we are told by petitioners' counsel, certain of the state

questions may be matters of first impression).

8

on the matter. See Railway Co. v. Ramsey. 89 U.S. (22 Wall.) 322,

328 (1874) (noting court's authority to remand sua sponte if

jurisdiction is found lacking); Cutler v. Rae, 48 U.S. (7 How.)

729, 731 (1849) (holding consent of parties does not confer federal

jurisdiction; it remains "duty of this court to take notice of the

want of jurisdiction, without waiting for an objection from either

party"). Finding that, even if this proceeding properly was

removed, we should abstain pursuant to familiar jurisprudential

considerations, we now remand this proceeding sua sponte. See

Corcoran v. Ardra Ins. Co.. 842 F.2d 31, 36-37 (2d Cir. 1988)

(holding "that when the district court may properly abstain from

adjudicating a removed case, it has the power to remand the case

to state court"). * II.

II. DISCUSSION

The right to remove a state case to federal court is, of

course, a unique incident to our federalist system with no

antecedent at common law. Consequently, removal must be founded

upon one of the statutory bases provided by Congress. Gold-Washing

and Water Co. v. Keves. 96 U.S. 199, 201 (1877) . The instant

petition invokes two such statutory provisions. First, the Article

78 respondents contend that removal is warranted under the

infrequently utilized "refusal clause" of the civil rights removal

statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1443(2). Second, it is contended that the

assertion of the First Amendment challenge to the December 1

Decision presents a federal question and warrants removal under the

9

general federal removal statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1441(b). We

consider each of these provisions in turn.

a. 28 U.S.C. $ 1443(2 )

Respondents devote the lion's share of their argument to the

propriety of removal in this case under the refusal clause of the

civil rights removal statute. The refusal clause permits removal

in those cases where a person acting "under color of authority" is

"refusing to do any act on the ground that it would be inconsistent

with [federal law providing for equal rights]." Of the precedent

that exists construing this awkwardly worded statute, perhaps the

two leading decisions were rendered by two of this circuit's most

learned and respected jurists.^.

Certainly, the most complete analysis of the statute provided

to date in any circuit is then District Judge Newman's opinion in

Bridgeport Edu. Ass'n v. Zinner. 415 F. Supp. 715 (D. Conn. 1976),

which sets out the criteria to be employed in a refusal clause

analysis. Generally adopting what he termed Judge Newman's

"exhaustive and scholarly review of the subject," now Chief Judge

Brieant, sitting by designation and writing for the two-member

majority in White v. Wellington. 627 F.2d 582 (2d Cir. 1980),

succinctly summarized the relevant inquiry: the refusal clause

"may be invoked when the removing defendants [state or municipal

officials] make a colorable claim that they are being sued for not

acting 'pursuant to a state law which, though facially neutral,

would produce or perpetuate a racially discriminatory result as

10

applied.'" Id. at 586 (quoting Zinner. 415 F. Supp. at 722). The

statute is exceptional in that it allows the presence of a federal

defense to control the question of jurisdiction. Zinner. 415 F.

Supp. at 723 n. 7 (citing Louisville & Nashville R.R. v. Mottlev.

211 U.S. 149 (1908)).

Recognizing, we think, that the statute, if left open-ended,

could lead to the "federalization" of standard state cases

involving challenges to official state or municipal action, an

important limitation (consistent with the existing legislative

history) has been read into the law's meaning. To state a

"colorable claim" under the statute, the removal petition must

contain a good faith allegation that there exists a conflict

between the state law in issue and a federal law protecting equal* «

rights. As Chief Judge Brieant put it, the removal petition must

allege "a colorable claim of inconsistent state/federal

requirements." Wellington. 627 F.2d at 587. See also Armeno v.

Bridgeport Civil Serv. Comm'n. 446 F. Supp. 553, 557 (D. Conn.

1978) (Newman, J.) (noting refusal clause permits removal when

official "declined to observe state requirements that he believes

are inconsistent with the obligations imposed on him by a federal

law protecting equal rights"). The basis of the conflict

requirement seems self-evident: without a colorable federal-state

conflict, the need to remove to federal court to ensure the proper

vindication of superior federal mandates is not manifested. When

federal and state interests are compatible, the state court is

poised to assure that the defendant's parallel justification for

11

action under state law is given proper consideration. cf.

ington, 627 F.2d at 590 (Kaufman, J. , concurring) (state

officials will seek "extraordinary" option of removal under the

refusal clause and forego the familiar confines of a state forum

"because the federal issue they seek to litigate is so

substantial").

Indeed, Judge Meskill, dissenting in Wellington, characterized

the colorable conflict requirement as the "jurisdictional

touchstone" under the refusal clause. Wellington, 627 F.2d at 592.

The Wellington majority concurred with that assessment:

We agree fully with Judge Meskill's

description of the "jurisdictional touchstone"

as "a colorable conflict between state and

federal law" leading to the removing

defendant's refusal .to follow plaintiff's

interpretation of st&te law because of a good

faith belief that to do so would violate

federal law. That good faith belief is tested

objectively, in that the claim to that effect

of the removing defendant must be "colorable."

Id- at 586-87. Where the majority and dissent parted ways was on

what would constitute a "colorable conflict." In that case, the

defendants had phrased their removal petition in the alternative;

i.e., they contended that they had not violated the applicable

state statute or, if it were found that they had, then they actedl

as they did for to do otherwise would have been inconsistent with

the requirements of federal law protecting equal rights. Judge

Meskill felt that alternative allegations of this nature did not

justify removal under the exceptional provisions of the refusal

clause. Id. at 591. The majority, however, found "no reason why

12

a removal petition cannot contain inconsistent allegations in the

nature, here, of a traditional plea of confession and avoidance

without confession," so long as the petition contains "a colorable

claim of inconsistent state/federal requirements." id. at 587.

Put differently, the contrary nature of state law need not be a

matter definitively resolved, so long as the defendant

alternatively can assert in good faith a colorable claim of

conflict with federal law. Id^ at 590 (Kaufman, J., concurring).

Guided by these holdings, we find that a colorable conflict

between federal and state law is neither asserted in the instant

petition nor can such a conflict in good faith be found to exist.

As outlined supra. Town Supervisor Veteran denied the

incorporation petition on six enumerated grounds. Only grounds (2)

and (3) implicate federal concerns relating to equal rights; the

remaining grounds for denial are largely ministerial in nature,

based entirely on the filing requirements of New York's Village

Law. Grounds (2) and (3), however, each conclude that even though

the Village Law "does not specifically address itself to the

'intent' of the petitioners, I firmly believe that the rights

granted by the federal and state constitutions transcend the

procedural technicalities set forth in the Village Law." December

1 Decision 5 2, at 4; id. 3, at 6. The referenced constitutional

protections are not identified in either the December 1 Decision

or the removal petition, but it seems plain that the allusions are

13

to the Fourteenth Amendment's command of equal protection.5 Thus,

respondents conclude, the Village Law, though neutral on its face,

would produce a discriminatory result if applied in ignorance of

federal constitutional proscriptions, and therein rests the

Citing only Gomillion v. Liahtfoot. 364 U.S. 339 (1960),

respondents' memorandum notes simply that "Supervisor Veteran

relied on ̂ federal constitutional protections against race

discrimination . . . [and] [t]here can be no genuine doubt that

these provisions are laws 'providing for equal civil rights.'"

Respondents' Conference Memorandum at 9. See also Town of

Greenburgh's Memorandum at 4 (same). Gomillion struck down a

gerrymandered plan redefining the boundaries of the City of

Tuskegee, Alabama as violative of the Fifteenth Amendment. That

amendment provides that the right of citizens to vote shall not be

denied on account of race or color. Justice Whittaker, noting that

"the Gomillion plaintiffs were not being denied their right to vote

"in the Fifteenth Amendment sense" (i.e., they could still vote,

albeit not within the newly defined city limits), concurred in the

decision but on grounds that the "fencing out" of black citizens

"is an unlawful segregation of* races of citizens, in violation of

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment . . . ."

Id̂ . at 349. Although of no moment, we think Justice Whittaker

makes a cogent point. More importantly, however, it has been

suggested that the Supreme Court has come ultimately to embrace

Justice Whittaker's analysis. See Karcher v. Daggett. 462 U.S.

725, 748 (1983) (Stevens, J., concurring) (noting "the Court has

subsequently treated Gomillion as though it had been decided on

equal protection grounds") (citing Whitcomb v.Chavis. 403 U.S. 124,

149 (1971)). Accord City of Mobile v. Bolden. 446 U.S. 55, 86-87

& n .7 (1980) (Stevens, J., concurring). We will not belabor the

reader with citation to a number of Court cases, both majority and

concurring opinions, which have cited Gomillion in the Fourteenth

Amendment context. Suffice it to say that gerrymandering by race,

although a Fifteenth Amendment violation under Gomillion. certainly

falls within the reach of the Equal Protection Clause as well.

That additional support could be especially pertinent here since

those who would be excluded from the allegedly gerrymandered

boundaries of the Village of Mayfair Knollwood would not, unlike

the plaintiffs in Gomillion. be deprived of their pre-existing

right to vote (here, in the Town of Greenburgh) . See especially

Caserta v. V illage of Dickinson. 491 F. Supp. 500, 506 n.14 (S.D.

'̂’eX- _ 1980) (distinguishing Gomillion since excluded plaintiffs

retained their pre-existing right to vote; "[t]hose not within the

°f Dickinson boundaries have merely maintained their status

quo as members of Galveston County"), aff'd in relevant part. 672

F.2d 431, 432-33 (5th Cir. 1982).

14

colorable conflict. Respondents' Conference Memorandum at 8-9.

Whether or not this is so, however, we believe respondents'

argument misses a crucial point.

Wellington repeatedly references and requires a conflict

between federal and "state law," not a state law or statute. The

corpus of pertinent "state law" under Wellington, it seems to us,

must necessarily include state constitutional law, for it is a

fundamental maxim of any constitutional society, as New York is,

that constitutional mandates govern and delimit legislative and

regulatory enactments of the majority. Thus, at least one New York

court has noted that incorporation petitions, even if in compliance

with the ministerial requirements of the Village Law, will not be

sustained if their end is that^of advancing facial discrimination.

In re Rose, 61 Misc.2d 377, 305 N.Y.S.2d 721, 723 (Sup. Ct. 1969),

aff'd mem. , 36 A.D.2d 1025, 322 N.Y.S.2d 1000 (2d Dep' t 1981) .6

Although state law in such a case may be found by resort to the

State Constitution, as opposed to the Village Law, it is "state

law" nonetheless which forbids the invidious result.

As is made plain by the December 1 Decision, Town Supervisor

Veteran relied on both the Federal and State Constitutions in

rejecting the petition. No conflict between the pertinent federal

and state constitutional provisions was perceived by Supervisor

Veteran; he acted at the command of both. See especially

Whether a town supervisor, as opposed to the courts, has

authority to make that determination was not discussed in Rose and

is not addressed here.

15

Wellington. 627 F.2d at 587 (central inquiry is whether official

subjectively believed an actual conflict between federal and state

law existed); id. at 590 (Kaufman, J., concurring) (same). Nor is

any such conflict to be found by reference to existing state law;

federal and New York constitutional law governing equal protection

are in harmony. See Seaman v. Fedourich. 16 N.Y.2d 94, 262

N.Y.S.2d 444, 450 (1965) (noting New York's equal protection

clause, embodied in N.Y. Const, art. 1, § 11, "is as broad in its

coverage as that of the Fourteenth Amendment"); Dorsey v.

Stuyvesant Town Corp.. 299 N.Y. 512, 530 (1949) (holding protection

afforded by New York's equal protection clause is coextensive with

that granted by Fourteenth Amendment), cert, denied. 339 U.S. 981

(1950).' 7 * «

The case at bar, therefore, is readily distinguishable from

Cavanagh v. Brock. 577 F. Supp. 176 (E.D.N.C. 1983) (three-judge

panel) , a case cited by respondents. Removal in that case was

permitted under the refusal clause because the removing defendants

argued that the relevant provisions of the North Carolina

Constitution. which were alleged to be in conflict with the

Fourteenth Amendment, either had been rescinded or, if in effect,

could not be complied with due to the contrary dictates of the

Federal Constitution. Id. at 179-80. Here, the Equal Protection

Clause will embrace whatever discrimination allegedly would have

occurred, supra note 5, and Seaman and Dorsey make plain that the

corollary state constitutional provision is at least as broad as

its federal counterpart. Thus, if Town Supervisor Veteran was

16

required by the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to act as he did, he similarly would be required to so act by the

equal protection clause of the New York Constitution since the

latter is to be read in pari materia with its federal relation.

Certainly, notwithstanding Supervisor Veteran's belief that

he was complying with state constitutional law, respondents'

ability to remove this case under the refusal clause is not lost

if the removal petition contains an allegation based on that

belief. Such is the teaching of Wellington. Respondents, however,

must in good faith be able to plead alternatively that if they were

not acting in accordance with state law, then their refusal to so

act was the product of conflict between federal and state mandates.

Wellington, 627 F.2d at 587. Ng such good faith assertion can be♦ «

made here. Federal and state law are coextensive in this area.

See also Fed. R. Civ. P. 11 (requiring that any "pleading, motion,

or other paper" submitted to the court and signed by an attorney

be grounded in good faith belief that its substance is warranted

by facts, law, or good faith argument for the law's modification).

The jurisdictional paragraph of the removal petition

acknowledges this reality. See Verified Petition for Removal f 1 1 ,

at 4-5 ("proposed village petition was rejected in part on the

basis of federal and state Constitutional and statutory provisions

providing for equal rights . . . [and,] [accordingly, this action

may be removed to this Court by respondents pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§ 1443(2)") (emphasis added). The petition's conclusion, however,

does not state the law. If it did, then in every case challenging

17

state or municipal action relying on federal authority parallelling

cited state law, the case could be removed to federal court. This

is not the conundrum contemplated by the refusal clause; indeed,

it is no conundrum at all. Federal and state law must not merely

parallel one another; they must be in conflict (or, more

accurately, there must be a good faith allegation of conflict).

See especially In re Quirk, 549 F. Supp. 1236, 1241 (S.D.N.Y. 1982)

(refusal clause satisfied since colorable conflict existed between

federal court order and New York civil service law); In re Buffalo

Teachers— Fed 1 n , 477 F. Supp. 691, 694 (W.D.N.Y. 1979) (removal

under refusal clause appropriate since "state defendant caught

between the conflicting requirements of a Federal [court] order and

of state law"); Zinner, 415 F.^Supp. at 718 {noting refusal clause

"'intended to enable state officers, who shall refuse to enforce

state laws discriminating in reference to [civil rights] on account

of race or color, to remove these cases to the United States courts

when prosecuted for refusing to enforce those laws'") (quoting

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1115 (1863) (statement of Rep.

Wilson)). Contrasted with those scenarios, respondents here are

being prosecuted for having acted as they saw fit under the State's

equal protection clause, not for having failed to do so, and that

provision tracks its federal namesake.

Consequently, we find that there is no colorable conflict

between federal and state law in this case, and that removal, if

18

justified here, must be found for reasons other than those provided

under the refusal clause.7

b. 28 U.S.C. 5 1441f

Under 28 U.S.C. § 1441(b), »[a]ny civil action of which the

district courts have original jurisdiction founded on a claim or

right arising under the Constitution, treaties or laws of the

United States shall be removable without regard to the citizenship

or residence of the parties." Clearly, the assertion of the First

Amendment claim in the petition presents a federal question. We

are not so sure, however, that an Article 78 proceeding

automatically qualifies as a "civil action" under the removal

statute. ** «

The term "civil action" (or the predecessor term "civil suit")

has been capaciously defined. Thus, the Supreme Court has opined

that appeals from state or municipal administrative action via writ

of prohibition or mandamus may qualify for removal:

The principle to be deduced from [our] cases

is, that a proceeding, not in a court of

justice, but carried on by executive officers

in the exercise of their proper functions, as

Our decision on the refusal clause might appear

gratuitous in light of our holding infra that, even if this case

was properly removed, principles of abstention warrant a remand.

Our ruling on the abstention/remand, however, might be different

were we to find that the case could be removed under the refusal

clause. Congress's explicit determination that state officials

facing the type of federal-state conflict outlined above should be

the option of a Federal forum would inevitably color an

abstention analysis. Respect for the state interests outlined

infra might very well have to give way in such a circumstance to

the overarching federal concern. Federalism (and respect for it)

does, after all, have a federal as well as state component.

19

i-1} the valuation of property for the just

distribution of taxes or assessments, is

purely administrative in its character, and

cannot, in any just sense, be called a suit;

and that an appeal in such a case, to a board

of assessors or commissioners having no

judicial powers, and only authorized to

determine questions of quantity, proportion

and value, is not a suit; but that such an

appeal may become a suit, if made to a court

or tribunal having power to determine

questions of law and fact, either with or

without a jury, and there are parties litigant

to contest the case on the one side and the other.

Upshur County v.__Rich, 135 U.S. 467, 475 (1890). Accord

Commissioners_of Road Improvement Dist. No. 2 v. St. Louis S.W.

Ry_:— COi, 257 U.S. 547, 557, 559 (1922) . Cf. Weston v. City Council

.of— £-har~leston/ 27 U.S. (2 Pet.) 449, 464 (1829) (the term "civil

suif/" in defining Supreme Court's appellate jurisdiction over

state cases, is a comprehensive one including various modes of

proceeding; so long as an adversary proceeding inter partes. it

qualifies as a "civil suit").

That said, it is beyond cavil that a statutory appeal of

administrative state action, whether or not it involves diverse

parties or a federal question, may not be filed in federal court.

Department of Transp . and Dev, of Louisiana v. Beaird-Poulan. Inc..

449 U.S. 971, 973-74 (1980) (Rhenquist, J., dissenting from denial

of certiorari) (citing Stude, 346 U.S. at 581). Following from

that principle, we doubt that Congress intended the term "civil

action" under the removal statute to be so sponge-like as to allow

its absorption of every conceivable type of proceeding involving

appeal from state or municipal administrative action which touches

20

upon a federal question. To believe otherwise is to suggest that

Congress was ignorant of notions of comity and federalism that are

such an important part of our constitutional and jurisprudential

fabric. Cf. St. Louis S.W. Rv.. 257 U.S. at 554 ("[a]n

administrative proceeding transferred to a court usually becomes

judicial, although not necessarily so") (emphasis added).8

In New York, an Article 78 proceeding, although admittedly

civil in nature, is manifestly circumscribed by the terms of the

statute, and it possesses numerous indicia distinguishing it from

a typical inter partes civil action. It is a self-styled "special

proceeding," NYCPLR § 7804(a), designed to supplant the previous

writs of certiorari, mandamus, and prohibition, id. at § 7801.

Consequently, and consistent with the predecessor writs, the scope♦ •

of review in an Article 78 proceeding is narrowly confined, id. at

§ 7803, and the relief recoverable is limited, id. at § 7806. A

number of other substantive and procedural irregularities are

unique to this form of proceeding. See especially NYCPLR § 103

(expressly noting distinction between "civil action" and "special

Indeed, the proper application in the modern context of

19th-Century Court precedent defining "civil action" is a matter

not free from doubt. Those Courts could not possibly have

envisioned the rise of populism, the demise of economic due

process, and ultimately the advent of the New Deal, all of which

radically changed economic life and governance in this society.

Mirroring the federal model produced by the New Deal, a multitude

of administrative agencies now permeate the ranks of state

decisionmaking. In that context, we think it a legitimate question

to wonder whether the Supreme Court and/or the Congress believe it

appropriate to define expansively the term "civil action" so as to

allow the universal removal of garden-variety appeals from state

administrative action.

21

proceeding," and vesting courts with authority to convert a special

proceeding into a civil action if nature of claim or relief sought

goes beyond confines of the former); j. Weinstein, H. Korn, & a .

Mlller' ~ York Civil Practice §§ 7801-06 (1988 & Supp. Dec. 1988)

(discussing nature of Article 78 proceeding); D. Siegel, Handbook

on. New York Civil Practice §§ 557-70 (1978 & Supp. 1988) (same).9

Given the unique nature of the action, the fingerprints of

federalism inevitably will be so spread upon an Article 78

proceeding that we doubt the proceeding ordinarily can be wiped

clean of its essential state administrative character by the mere

presence of a federal question, no matter how insignificant, and

be rendered removable thereby. Therefore, to permit generally the

removal of Article 78 proceedings under 28 U.S.C. § 1441 is, we* «

think, to invite disruption with well-settled notions of comity

and federalism. See, e ^ , Crivello y. Board of Adjustment i83

F. Supp. 826, 828 (D.N.J. i960) (holding appeal of state

administrative action via writ of certiorari, although nominally

denominated a "civil action at law," did not constitute a "civil

action" as that term is used under the general removal statute);

Collins v. Public Serv. Com m 'n of Missourir 129 F. Supp. 722, 725

9

4- ^hus' for example, an Article 78 proceeding is f a r

Libfrt^MutifaT x hG ^dministrative "appeal" at issue in Horton~v.

th^t a ’ U,S- 348 (1961)- The Court there heldworker's a Texas administrative determination on a

"civil Ltfon" o C°Uld bS filed in Federal court as anrovtde! ? on grounds of diversity, but only because Texas law

?i?t ?! ^ t * ?USh 9 challen9e "is not an appellate proceeding[;]

been decide? hv t I D S t S ~ l l y with°dt reference to Shat may hav!«d f d\d b-Y thS [Texas Industrial Accident] Board." id. at 354-55 (emphasis added) .

22

(W.D. Mo. 1955) (finding appeal of state administrative action by

writ of certiorari to county court "was a mere continuation of the

administrative proceeding" and, thus, could not be removed). But

— t y of Owatonna v. Chicago. Rock Island & Pacific r .r . co.

298 F. Supp. 919, 922 (D. Minn. 1969) (and cases cited therein).10

Despite our misgivings, we assume for present purposes that

an Article 78 proceeding may be removed under the general removal

statute, for our concerns and respect for federalism can be

accommodated in this case by the law of this circuit relating to

10

Our conclusion would by necessity be different when

ctlZi1o?f2fnu T j Cl1 ™ ? ^ eedi ng iS s°^htyunder the^refuSl?5 28 u -s *c : § 1443(2), the civil rights removal statute discussed supra. Since an Article 78 proceeding is the prescribed

avenue of challenge to administrative action in this State such

a proceeding must be removable under the refusal clause if that clause is to be given effect in New York. clause if that

ArHrlp ™ 1S°' theJ e may be times when the federal interest in an Article 78 proceeding may so predominate as to warrant the

proceeding s removal under 28 U.S.C. § 1441. Thus, in a series Sf

cases involving appeals to state courts from tobacco quotas imposed

rLoval ufdi"1S?HratiVe reV1leW federal coSts p e S ? “ dremoval under the general removal statute. In those cases

however, the local committees were authorised by federal iSJand

AaJt^m temberS aPPointed bY the United States Secretary of

th e ' manifest;Ln9 the obvious federal interest in regulating

(E D ^ C — yis y- Joyner, 240 F. Supp. 689, 690-91

c l ™ V ,cases Clted therein)* Cf, Yonkers Racinggprp. v. city of Yonkers, 858 F.2d 855, 863-64 (2d Cir. 1988?

ifiswi?9 r®moval authorized under All Writs Act, 28 U.S.C. § )/ where real possibility that underlying Article 78

cou??eoirt9 C°Uld be. used to frustrate implementation of federal

cert dentp/e^ 9Hec to remedy racial discrimination in Yonkers) , £ert •— denied, 57 U.S.L.W. 3619 (1989). '

Absent special circumstances, however, we remain dubious

Articl 7s *l s d o m °f a general rule permitting the removal of

h ™ k 78 proceedlngs - Although several Article 78 proceedings have boen removed to courts in this circuit, this specific question

abil?tve^ beSn addressed* Obviously, it could be argued that the

assirapH SUCh Proceedings heretofore simply has beenassumecJ without the need for extended discussion. We are not sosUic •

23

our remand authority. The Supreme Court has held that removed

actions generally may not be remanded except within the narrow

confines of the remand statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1447(c) (i.e., that the

case was removed improvidently or without jurisdiction). Thermtron

Prod., Inc, v. Hermansdorfer. 423 U.S. 336, 345 & n. 9 (1976). The

Second Circuit, however, has found a practical exception to that

rule, concluding "that when the district court may properly abstain

from adjudicating a removed case, it has the power to remand the

case to state court." Corcoran v. Ardra Ins. Co.. 842 F.2d 31, 36-

37 (2d Cir. 1988). Accord Naylor v. Case and McGrath. Inc.. 585

F.2d 557, 565 (2d Cir. 1978). The exception, among other things,

is grounded in the reality that no purpose would be served by

retaining a removed case and then dismissing it on abstention

grounds, if applicable, rather than simply remanding the matter to

the appropriate state forum. Because the fingerprints of

federalism referenced earlier are so clearly discernible here, we

find abstention to be appropriate and we thus remand the matter in

accord with the remand exception outlined in Ardra Insurance.

c. Abstention

Jurisprudential limitations on our jurisdiction long ago»

announced in Burford v. Sun Oil Co.. 319 U.S. 315 (1943) largely

control our view of this matter.

Burford, of course, involved a challenge to the validity of

state administrative action permitting the drilling of certain

wells in an east Texas oil field. The legal challenge was

24

initiated in federal court on grounds of diversity and federal

question (due process) ; the case at bar was removed to federal

court on the latter basis. In granting dismissal of the Burford

challenge in the exercise of its equity jurisdiction, the Court

noted:

Although a federal equity court does have

jurisdiction of a particular proceeding, it

may, in its sound discretion, whether its

jurisdiction is invoked on ground of diversity

of citizenship or otherwise, "refuse to

enforce or protect legal rights, the exercise

of which may be prejudicial to the public

interest" fUnited States ex rel. Greathouse v.

Dern, 289 U.S. 352, 360 (1933)]; for it "is in

the public interest that federal courts of

equity should exercise their discretionary

power with proper regard for the rightful

independence of state governments in carrying

out their domestic policy." [Pennsylvania v.

Williams. 294 U.S. 176, 185 (1935).]» «

Burford, 319 U.S. at 317—18 (footnotes omitted). Those concerns

were found to be present in Burford. which involved important state

interests (the division of oil-drilling rights) that were the

subject of comprehensive state regulation.

The Second Circuit has distilled the principles underlying

Burford thusly:

[Burford] abstention is appropriate when a

federal case presents a difficult issue of

state law, the resolution of which will have

a significant impact on important state

policies and for which the state has provided

a comprehensive regulatory system with

channels for review by state courts or

agencies. fBurford. 319 U.S.] at 333-34, 63

S. Ct. at 1107-08. In short, federal courts

should "abstain from interfering with

specialized, ongoing state regulatory schemes."

25

Alliance of American Insurers v. Cuomo. 854 F.2d 591, 599 (2d Cir.

1988) (quoting Levy v. Lewis. 635 U.S. 960, 963 (2d Cir. 1980)).

In the case at bar, petitioners seek the incorporation of the

Village of Mayfair Knollwood, which requires a grant of state

authority. N.Y. Const, art. 10, § 1; Village Law § 2-200; 1 E.

McQuillen, The Law of Municipal Corporations §§ 1.19 & 2.07b (3d

ed. 1987) ("McQuillen"). As Town Supervisor Veteran alluded to in

his December 1 Decision, the legal concept of village incorporation

was created to allow residents of a particular area the opportunity

to band together for the purposes of securing fire and police

protection and other public services, such as water and sewer.

December 1 Decision f 2, at 3-4. Given these uniquely local

interests, and particularly in an age of increasingly scarce

* •

resources (both natural and fiscal), it would seem beyond

peradventure that the State of New York retains as profound an

interest in certifying village incorporation petitions as does the

State of Texas in certifying oil-drilling licenses. See especially

Gomillion. 364 U.S. at 342 (recognizing "the breadth and

importance" of a State's power "to establish, destroy, or

reorganize by contraction or expansion its political subdivisions,

to wit, cities, counties, and other local units"); Hunter v. City

of Pittsburgh. 207 U.S. 161, 176, 178-79 (1907) (noting creation

of municipal incorporations and definition of their size and nature

are matters peculiarly within jurisdiction of the States). Accord

1 McQuillen § 3.02, at 235; 2 McQuillen at §§ 4.03 & 7.03; C.

Rhyne, Municipal Law §§ 2-2 & 2-26 (1957). Thus, that as a general

26

proposition federal courts should not be muddying the waters in

which the village incorporation process swims seems to us an

unremarkable and inevitable conclusion.

Further, and acting partly as confirmation of the above state

interest, New York has established a "comprehensive regulatory

system with channels for review by state courts or agencies,"

American— Insurers, 854 F.2d at 599, to assess the propriety of

village incorporation petitions:

the statute specifically identifies what geographic areas may

be incorporated as a village, section 2-200 of the VillageLaw; ^

it spells out in elaborate detail who may petition for

incorporation and what the contents of the petition must comprise, section 2-202;

it establishes a public notice and hearing requirement once

f is filed with, -a town supervisor, again setting

forth in greatuietail the hearing requirements, section 2-204;

it specifically^ notes what objections may be lodged against

^ village petition, and how and when these objections should be presented, section 2-206;

it sets forth a specific timetable for action on the petition

following hearing, and outlines the prerequisites for the

written decision that the town supervisor must issue on the matter, section 2-208;

^ specifically provides that review of a town supervisor's

decision may be had only by resort to an Article 78 proceeding

on grounds that the "decision is illegal, based on

insufficient evidence, or contrary to the weight of the evidence," section 2-210(1);

it requires that appeal via the Article 78 route must be taken

within 30 days from filing of the town supervisor's decision,

section 2-210(2), and that such appeal shall have preference

over all civil actions and proceedings, section 2-210(4) (e);

it goes on to delineate the right to and procedures for

conducting^ an election to determine the question of

incorporation, sections 2-212 to 2-222;

27

it sets forth the procedure for judicial review of an

incorporation election, and provides for a new election if the

original election is set aside, sections 2-224 to 2-230; and finally, '

it outlines the formalities of incorporating, the procedures

for electing and appointing officers, the conduct of village

meetings, the effect on public services, and the taxing

authority possessed by the village, sections 2-232 to 2-258.

this does not constitute a comprehensive statutory scheme,

regulating in this case a matter within the fundamental

prerogatives of the state, then the court would be hard pressed to

identify such a scheme. Certainly, the scheme is as comprehensive

and the interest as strong as those existing in Levy, where the

Second Circuit directed abstention due to New York's "complex

administrative and judicial system for regulating and liquidating

domestic insurance companies." Levy. 635 F.2d at 963. To* «

paraphrase Burford, we think the regulation of village

incorporations so obviously involves a matter of uniquely state

policy that wise judicial discretion counsels in favor of avoiding

needless federal intervention in the state's affairs, especially

since a comprehensive regulatory scheme to address this matter has

been put in place. Burford. 319 U.S. at 332.

That this proceeding also implicates a federal question does

not alter our conclusion. Burford. too, involved a federal

question but, as the Supreme Court noted, ultimate review of that

question before the Court was preserved fully by their action, id.

at 334- Accord Levy. 635 F.2d at 964.

Moreover, the federal question here asserted may never need

be reached. Four of the five challenges to the December 1 Decision

28

asserted in the Article 78 petition (claims (l)-(4), delineated

supra) involve challenges to the propriety of Veteran's actions

under the Village Law.11 Petitioners' counsel has represented that

certain of these questions — particularly those involving the

nature of the local hearing to be held on these matters, how and

what evidence can be received and relied upon, and the scope of the

town supervisor's statutory authority — appear to be matters of

unsettled state law. We have found little case law specifically

^dd^sssing the state issues here raised. If the December 1

Decision is reversed on any of these grounds, the First Amendment

assertion will not be reached. When unsettled questions of state

law are susceptible of an interpretation which may obviate the

federal constitutional question presented, the federal Court should

* «

defer on these questions — at least in the first instance — to

a state tribunal. Orozco v. Sobol. 703 F. Supp. 1113, 1121

(S.D.N.Y. 1989) (cases collected, including Railroad Comm'n of

Texas v. Pullman, 312 U.S. 496 (1941)). See also L e w . 635 F.2d

at 964 (since federal question was bound with state issues, best

left in the first instance to state courts with review available *

We add that the existence of these purely state

administrative issues places this case in a posture far different

from that found in Gomillion and cases like it, which constitute

straight constitutional challenges to gerrymandered municipal

boundary plans devised upon conclusion of the legislative or

administrative drafting processes. Had the instant incorporation

petition been approved under the Village Law, and the Deutsch

defendants (assuming they had standing) then challenged that action

in federal court on Fourteenth Amendment grounds, we have little

doubt that we properly would have jurisdiction over the subject

matter and that plaintiffs' choice of a federal forum would be

respected. That is not the posture of this case.

29

These concerns militate

further in support of abstention.12

As Levy concludes, in words equally applicable here:

The claims [in Burford] amounted to an attack

. ^he reasonableness of the state

administrative action. Thus federal review

while involving decision of a federal

question, would have entailed a

reconsideration of the state administrative

decision, carrying with it the potential for

creating inequities in the administration of

the state scheme. Burford thus suggests that

p^2pe^ resPect for the expertise of state officials and the expeditious and evenhanded

ultimately before the Supreme Court).

"rb*? s P ̂ uhoatKh?/h sss-cSk:

s o o t h e “ nsion^iS^rent P/ranel judicia! processes. ■

this case Is ^ 26 n '9 <M 8 7 > • Thus, althoughexistence of 9 largely -Burford considerations, theexistence of Pullman concerns certainly is relevant

Notwithstanding Pennzoil's footnote 9, however, there do exist

important procedural differences between the "various types of

Pjrtinent here, we note that the product of Burfo?d abstention is dismissal, while under Pullman fod^r-ai ~

issues nay be bifurcated, with the — federal court retain!^

ifrl«turai£a OVtor thatf°?"er anr the liti,3ants allowed the option - . , eturning to that forum to address the federal con ce rn s

following state review. Enqland v. Louisiana state Bd. of Medical

Examiners, 375 U.S. 411, 421-22 (1964).---ait see Harris S !

ggmm rs Court v. Moore, 420 U.S. 77, 88 & n.14 (19751 (dismissal

state- courtCiurisd?ot^rifte H necessarV to remove obstacles to federal and iL-*.1 diCtl°n) .* ItT makes no sense to bifurcate the ?nd ?tate issues in this case, especially since to do so

for como^ettla11/ frustrate the Village Law's scheme of providing FnJth^nPl t aild exPe.dlti°us review of incorporation petitions9

210 M W b ) of Sthe ev niWalth Tthe *arvice requirements of section 2- ■7Q i, Village Law, the costs of bringing a new Article

(gi^e^th^nuiiler^?633 State issues ”°uld be substantial"lolutiM" ine^i taSf Parctles evolved) , arguably rendering that instant nrnpo bl Since Burford concerns predominate in the

remand th^ e n ? ? ^ 9 ' ? ? Ch°OSe to keep the proceeding whole and

in both Burford anH T 6r to state court which, as was emphasized Fir-gt ~ rfo^d .and bevy, is entirely competent to address the First Amendment issue asserted here (if it need be reached).

30

administration of state programs counsels

restraint on the part of federal courts.

Levy, 635 F.2d at 964. Here, Article 78 review under the Village

Law is designed to provide the aggrieved party with the opportunity

for expedited and confined judicial review of state administrative

action. That review is, in essence, largely an extension of the

administrative process itself given the reviewing court's limited

scope and remedial authority, and it is that forum which should be

deciding the state issues which predominate in this matter. If

federal questions are implicated in that process and improperly are

decided, ultimate review before the Supreme Court is preserved.

Abstention, therefore, is warranted here.

Assuming the general removability of Article 78 proceedings,

the instant matter involves a federal question and may be removed

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1441(b). Consistent with Ardra Insurance,

however, and because we would abstain from deciding the issues here

presented under familiar jurisprudential considerations, the

instant proceeding is remanded to the court from whence it was

removed, the New York Supreme Court for Westchester County.

Cor»clusion

SO ORDERED

Dated: White Plains, N.Y

April /o , 1989April f*i

GERARD L. GOETTEL

U.S.D.J.

31

Exhibit 2

UNITED STATES DISTRICT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK m m

YVONNE JONES, ANITA JORDAN, APRIL

JORDAN, LATOYA JORDAN, ANNA RAMOS,

LIZETTE RAMOS, VANESSA RAMOS,

GABRIEL RAMOS, THOMAS MYERS,

LISA MYERS, THOMAS MYERS, JR.,

LINDA MYERS, SHAWN MYERS,

ODELL A. JONES, MELVIN DIXON,

GERI BACON, MARY WILLIAMS,

JAMES HODGES, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED

PEOPLE, INC., WHITE PLAINS/

GREENBURGH BRANCH, AND NATIONAL

COALITION FOR THE HOMELESS,

88 n vVi I • "( i a C ?

Plaintiffs,

-against-

LAURENCE DEUTSCH, COLIN EDWIN

KAUFMAN, STEVEN NEIL GOLDRICH,t

MICHAEL JAMES TONE, COALITION*OF

UNITED PEOFLES, INC., and

ANTHONY F. VETERAN, as Supervisor

of the Town of Greenburgh,

Defendants.

1 |« .

U

it*--

NOV 1 t993 1

- - -1'- C-, £ P i

■svl

88 Civ.

COMPLAINT

Plaintiffs, by their attorneys, for their con-

plaint, allege (on information and belief except as to

paragraphs 3-5, 8, and 39-50):

Nature of the Action and Background

1. This action is brought by a number of black

citizens of Greenburgh, parents of homeless families in

Westchester County, the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People, White Plains/Greenburgh Branch

("NAACP") and the National Coalition for the Homeless (the

"National Coalition") to obtain redress against a racially

motivated conspiracy formed by the defendants other than

Anthony Veteran (hereinafter the "Conspiring Defendants") for

the purpose of depriving racial minorities and homeless

persons of constitutional and statutory rights. The

Conspiring Defendants are residents of Westchester County who

have banded together to seek incorporation of a new, almost

totally segregated village. Their declared purpose is to

defeat a project to build housing for homeless families, most* «

of whom belong td racial minorities, by using the new

village's zoning power. In furtherance of this scheme, they

have drawn the village boundaries in a grotesque shape,

thereby attempting to ensure its all-white composition and to

guarantee attaining their racially exclusionary objective.

Defendants' conduct constitutes a conspiracy in violation of

42 U.S.C. § 1985 that should be declared unlawful, enjoined,

and remedied, as against the Conspiring Defendants but not

defendant Veteran, by an appropriate award of monetary

damages.

2. This conspiracy is a direct attack on a

coordinated effort by state, county and municipal government

-- aided by a non-profit, charitable organization — to

2

establish safe and decent temporary housing for homeless

families with children in Westchester County. Westchester

County currently shelters approximately 957 families with

1978 children in a number of sub-standard facilities includ