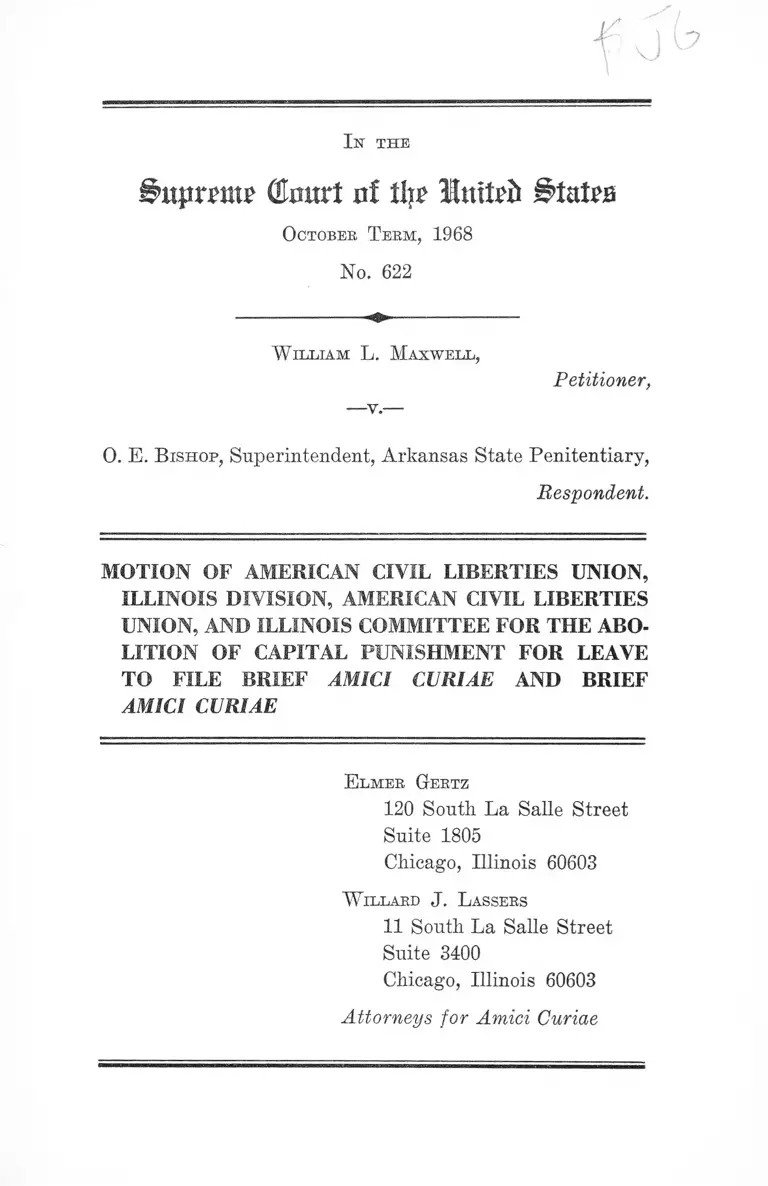

Maxwell v. Bishop Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and ACLU Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v. Bishop Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and ACLU Brief Amici Curiae, 1969. 93dcfc5c-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a615a3a6-5eb6-46df-b9cb-3de405240e56/maxwell-v-bishop-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amici-curiae-and-aclu-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Bnpxmt (Emtrt of 'Mnxtxb l̂ fafaa

October T erm, 1968

No. 622

W illiam L. Maxwell,

Petitioner,

0. E. B ishop, Superintendent, Arkansas State Penitentiary,

Respondent.

MOTION OF AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

ILLINOIS DIVISION, AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION, AND ILLINOIS COMMITTEE FOR THE ABO

LITION OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT FOR LEAVE

TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE AND BRIEF

AMICI CURIAE

Elmer Gertz

120 South. La Salle Street

Suite 1805

Chicago, Illinois 60603

"Willard J. Lassers

11 South La Salle Street

Suite 3400

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

I N D E X

Brief of A mici Curiae ................................................ 5

I. The single verdict procedure violates the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments .............................. 6

II. Imposition of the death penalty in the absolute

discretion of the jury, uncontrolled by standards

or direction of any kind, violates due process .. 14

Conclusion.............................................................. 21

Table of Cases

In re Anderson, 73 Cal. Reptr. 21 at 36, 40-59 ........... 14

Bradshaw v. Commonwealth, 174 Ya. 391, 4 S. E. 2d

752 (1939) ......................................................................... 16

Commonwealth v. Madaffer, 291 Pa. 270, 139 Atl. 875

(1927) ................................................................................. 16

Eacret v. Holmes (Governor), 215 Ore. 121, 333 P. 2d

741, 744 (1958) ................................................................ 19

Ex parte Grossman, 267 U. S. 87 (1924) ........................... 19

Hernandez v. State, 43 Ariz. 424, 32 P. 2d 18 (1934) .. 16

Howell v. State, 102 Ohio 411, 131 N. E. 706 (1921) .... 16

Jamison v. Flanner, 116 Kan. 624, 228 P. 82 (1924) .... 19

PAGE

11

PAGE

Marshall v. State, 33 Tex. 664 (1871) .......................... 16

Martin v. State, 21 Tex. App. 1, 17 S. W. 430 (1886) .. 19

McGee v. Arizona State Board of Pardons and Paroles,

92 Ariz. 317, 376 P. 2d 779 (1962) ................................ 18

Montgomery v. Cleveland, 134 Miss. 132, 98 So. I l l

(1923) ............................................................................... 19

In re Opinion of Justices, 120 Mass. 600 (1876) ........... 19

People v. Bernette, 30 111. 2d 359, 197 N. E. 2d 463

(1964) ....... 14

People v. Bonner, 37 111. 2d 553, 229 N. E. 2d 527 (1967) 17

People v. Dukes, 12 111. 2d 334, 146 N. E. 2d 14 (1957) 17

People v. Jenkins, 325 111. 372, 156 N. E. 290 (1927) 18

People v. Meyers, 35 111. 2d 311, 220 N. E. 2d 297

(1966), cert. den. 87 S. Ct. 752, 385 U. S. 1019, 17

L. Ed. 2d 557 ................................ -................................ 17

People ex rel. Page v. Brophy, 248 App. Div. 309, 289

N. Y. S. 362 (1936) ...................................................- 19

People v. Smith, 14 111. 2d 95, 97, 150 N. E. 2d 815

(1958) ............................................................................... 16

People v. Taylor, 33 111. 2d 417, 211 N. E. 2d 673 (1965) 17

Pope v. U. S., 372 F. 2d 710, 727-730 (CA 8th 1967) 13

Smith v. State, 205 Ark. 1074, 172 S. W. 2d 248 (1943) 16

State v. Chaney, 117 W. Va. 605, 186 S. E. 607 (1936) 16

State v. Christensen, 166 Kan. 152,199 P. 2d 475 (1948) 16

State v. Harrison, 122 S. C. 523, 115 S. E. 746 (1923) 19

State v. Wilson, 151 Iowa 698, 141 N. W. 337 (1913) .... 16

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U. S. 510 (1968) ...............2, 21

Constitutions and Statutes

page

Ala. Code tit. 14, sec. 318 (1940) .................................. 14,15

Ariz. Rev. Stat. sec. 13-453 (1956) .............................. 14

Ark. Stat. Ann. secs. 41-2227, 43-2153 (1947) ............... 14

Cal. Pen. Code sec. 190 (1955) ...................................... 14

Code of Criminal Procedure of 1963 Sec. 121-9 ........... 12

Colo. Rev. Stat. ch. 40, art. 2-3 (1963) .......................... 14

Conn. Stat. Ann. sec. 53-10 (1958) .................................. 15

Dela. Code Ann. tit. 11, sec. 571 (1953) ....................... 15

Fla. Stat. secs. 782.04, 919.23 (1951) .............................. 15

Ga. Code Ann. sec. 26-1005 (1953) .................................. 15

Idaho Code sec. 18-4004 (1947) ...................................... 15

Illinois Constitution, Art. II, Sec. 2 .............................. 17

Illinois Constitution, Art. 5, Sec. 13 .............................. 18

Illinois L. 1819, p. 213, Sec. 2 ...................................... 7

Rev. Laws 1827, Crim. Code §§22-24 ....... 7

Rev. Stat. 1845, ch. 30, §§22-24................................ 7

Rev. Stat. 1874, ch. 38, §142...................................... 8

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38, secs. 9-1, 1-7 (c) (1) (1967) .... 7, 8

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38 sec. 1-7 (g) (1967) ...................7,14,15

Ind. Ann. Stat. secs. 10-3401, 9-1819 (Burns 1956) .. 15

Kan. Stat. Ann. sec. 21-403 (1964) .............................. 15

Ky. Rev. Stat. secs. 431.130, 435.010 (1948) ................... 15

La. Rev. Stat. tit. 14, sec. 30, tit. 15 sec. 409 (1950) .. 15

Md. Ann. Stat. Art. 27, sec. 413 (1957) .......................... 15

Mass. Laws Ann. ch. 265, sec. 2 (1956) ............. 15

Miss. Code Ann. sec. 2217 (1942) .................................. 15

I l l

IV

Mo. Stat. Ann. see. 559.030 (1949) ....... ,.......................... 15

Mont. Rev. Code Ann. sec. 94-2505 (1947) ................... 15

Neb. Rev. Stat. see. 28-401 (1943) ............................... 15

Nev. Rev. Stat. sec. 200.030 (1963) ................................ 15

N. H. Rev. Stat. Ann. sec. 585.4 (1955) ..................... 15

N. J. Stat. Ann. tit. 2A, ch. 113, sec. 4 (1953) ............ 15

N. M. Stat. Ann. ch. 40A, sec. 29-2 (1953) .................... 15

N. Y. Penal Code sec. 1045 ............................................. 15

N. C. Gen. Stat. sec. 14-17 (1953) ................................. 15

Ohio Rev. Code tit. 29, sec. 2901.01 (1964) ................ 15

Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 21, sec. 707 (1951) ................... 15

Pa. Stat. Ann. tit. 18, sec. 4701 (Purdon 1963) ........... 15

S. C. Code of Laws tit. 16 sec. 16-52 (1962) ................... 15

S. D. Code of 1939 (1960 Sapp.) Ch. 13.20 sec. 13.2012

(1960) .... ............................................................................ 15

Tenn. Code Ann. sec. 39-2405 (1955) ............................ 15

Tex. Pen. Code art. 1257 (1961) ...................................... 15

Utah Code Ann. tit. 76, sec. 76-30-4 (1953) ............... 15

Yt. Stat. Ann. tit. 13, sec. 2303 (1959) ....................... 15

Wash. Rev. Code Ann. tit. 9, sec. 9.48.030 (1961) .... 15

Wyo. Stat. Ann. sec. 6-54 .............................................. 15

PAGE

V

Other A uthorities

page

16 C. J. S. Const. Law sec. 157, p. 830 .......................... 19

Executive Clemency in Capital Cases, 39 N. T. U.

Law R. 136, 178 (1964) ................................................ 19

Kalvin and Zeisel, “ The American Jury and the Death

Penalty,” 33 TJ. Chi. L. Rev. 769, 770 (1966) ........... 15

National Prisoner Statistics—Executions No. 42, June

1968, Table 10, page 2 2 .................................................. 6

Pease, Laws of the Northwest Territory—1788-1800,

page 13 ............................................................................. 6

Philbrick, Pope’s Digest, 1815, Vol. 1, page 91 ........... 7

Rules of the Supreme Court of Illinois (Rule 615 (b)

(4)) ............................................ -................................... 11,16

In t h e

Bnpvmt (tort nf ttjr Imtrtu Itote

October T erm, 1968

No. 622

W illiam L. Maxwell,

Petitioner,

— v.—

0. E. B ishop, Superintendent, Arkansas State Penitentiary,

Respondent.

Motion of American Civil Liberties Union, Illinois Divi

sion, American Civil Liberties Union, and Illinois

Committee for the Abolition of Capital Punishment

for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae

The American Civil Liberties Union and the Illinois

Committee for the Abolition of Capital Punishment, move

the Court for leave to appear as Amici Curiae in this case

and to file a brief in support of the petitioner. Petitioner

has consented to the filing of this brief. The respondent’s

attorney has not replied to our request.

The American Civil Liberties Union, an organization de

voted to the preservation of a free and open society, prin

cipally through the Bill of Bights and the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, has

taken the position that capital punishment is inherently a

civil liberties issue.

2

With leave of this Court, the Illinois Division of the

American Civil Liberties Union filed an Amicus Curiae

brief in Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U. S. 510 (1968). In

that brief, and particularly in points III and IV (pp. 19-

30), pertaining to the absence of legislative and judicial

guidelines, the A.C.L.U. anticipated in some aspects the

issues to which the grant of certiorari herein has been

limited.

Capital punishment must be examined, not as if it were

one among many punishments society chooses to impose

upon its offenders, but one awful in contemplation and

irrevocable in result. The issues as framed by this Court

must be considered in light of the fact that the death

penalty is withering away everywhere. The dramatic de

cline is shown by the fact that in 1968 there was not one

execution in the entire country; in 1967, there were two

executions, and in 1966 one. A substantial and growing

segment of all Americans, probably a majority, is opposed

to the death penalty. Tet almost 500 persons are now under

sentence of death. This creates a moral and constitutional

dilemma that must be confronted and resolved by this

Court.

The Illinois Committee to Abolish Capital Punishment

joins with the American Civil Liberties Union in this appli

cation. This Committee numbers in its membership lead

ing citizens of the State of Illinois, of all religious faiths

and professional, social and economic levels. It has been

active in its field for several years and is familiar with

3

the problems involved herein. Counsel for Movants are

members of the Committee.

Respectfully submitted,

E lmer Gertz

120 South La Salle Street

Suite 1805

Chicago, Illinois 60603

W illard J. Lassers

11 South La Salle Street

Suite 3400

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Attorneys for Movants

Ik t h e

Supreme (tort nf tlj? Itutpfc BtntBB

October T erm, 1968

No. 622

W illiam L. Maxwell,

— v .—

Petitioner,

0. E. B ishop, Superintendent, Arkansas State Penitentiary,

Respondent.

---------- -— --------------- ---- ---

BRIEF OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

ILLINOIS DIVISION, AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION, AND ILLINOIS COMMITTEE FOR THE ABO

LITION OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT, AMICI CURIAE

Because the attorneys for Amici practice in Illinois, this

brief will be devoted largely to the Illinois experience

and will supplement what is before the court respecting

Arkansas.

Presently twenty-one men and one woman are under the

death sentence in Illinois. At the end of 1967, the last year

for which full statistics have been published, Illinois had

nineteen inmates on death row and ranked eighth among

the states in the number of capital prisoners.

The Illinois experience has broad relevance to the ease

at bar because all of those awaiting execution in Illinois

have been convicted of murder. Thus the Illinois cases

6

present the mainstream of the problem.* Furthermore,

under Illinois law there is both a unitary trial and an ab

sence of statutory and case law standards. Thus each of

the questions upon which certiorari has been granted is an

Illinois issue. There are, however, subtle differences be

tween Illinois law and Arkansas law. Comment on these

differences will put the issues at bar in broader perspective.

A R G U M E N T

I.

The single verdict procedure violates the Fifth and

Fourteenth Amendments.

The single verdict procedure became part of the law of

Illinois by historical accident. The earliest statute on

murder, enacted for the Northwest Territory, was the law

of September 6, 1788. (Pease, Laws of the Northwest Ter

ritory— 1788-1800, page 13). It provided tersely:

“ If any person or persons shall with malice aforethought,

kill or slay another person, he, she, or they so offending

shall be deemed guilty of murder, and upon conviction

thereof shall suffer the pains of death.”

Under this statute, there was no occasion to separate

the issues of guilt or innocence from the issues of mitiga

tion or aggravation, because there was only a single penalty

for murder. The definition of the crime of murder varied

somewhat over the years, but the sole statutory penalty

* For 1967, of 435 individuals then under sentence of death

nationally, 357 were sentenced for murder. National Prisoner

Statistics— Executions No. 42, June 1968, Table 10, page 22.

7

provided for murder was death. (See the statute enacted

for Illinois Territory in 1807, Philbrick, Pope’s Digest, 1815,

Volume 1, page 91.) It was re-enacted in the first criminal

code of the State (Laws 1819, page 213, Section 2). (For

later enactments see Revised Code of Laws, 1827, Criminal

Code, Sections 22-24 and Rev. Stats., 1845, Chapter 30,

Sections 22-24.)

In 1867, for the first time, the mandatory sentence of

death for murder was abolished. In its place the jury was

authorized to impose a sentence of death, life imprison

ment, or a term of not less than 14 years. The humani

tarian purposes of this statute are apparent from its text

(Laws 1867, page 90):

“ That in all cases of felonies, which, by existing laws

are punishable with death, it shall be competent for

the jury empaneled, to return with their verdict of

guilty, and as part of the same, either that the prisoner

shall suffer death by hanging, as now provided by law,

or that he be imprisoned in the penitentiary for the

term of his natural life, or for a term of not less than

fourteen years, as they may decide; and no person shall

be sentenced to death by any court, unless the jury

shall have so found in their verdict upon trial.” *

* The foregoing statute remained essentially unchanged until

enactment of the Criminal Code of 1961, Illinois Revised Statutes

1967, Chapter 38, Secs. 1-7 (c) and 9-1.

Sec. 9-1 (b) provides:

A person convicted of murder shall be punished by death or

imprisonment in the penitentiary for any indeterminate term

with a minimum of not less than 14 years. If the accused is

found guilty by a jury, a sentence of death shall not be im

8

The Illinois Statutes were codified in the mid 1870’s. The

earlier enactments, together with the 1867 amendment, ap

peared in the Revised Statutes of 1874, Chapter 38, §142,

as follows:

“ Murder-Punishment. §142. Whoever is guilty of mur

der, shall suffer the punishment of death, or imprison

ment in the penitentiary for his natural life, or for a

term not less than fourteen years. If the accused is

found guilty by a jury, they shall fix the punishment

by their verdict; upon a plea of guilty, the punishment

shall be fixed by the court. R. S. 1845, P. 155, §24;

L. 1867, p. 90 §1.”

posed by the court unless the jury’s verdict so provides in

accordance with Section 1-7 (c) (1) of this Code.

Sec. 1-7 (e) (1) provides:

Where, upon a trial by jury, a person is convicted of an of

fense which may be punishable by death, the jury may return

a verdict of death. Where such verdict is returned by the

jury, the court may sentence the offender to death or to im

prisonment. Where such verdict is not returned by the jury,

the court shall sentence the offender to imprisonment.

Thus under present law, the jury determines guilt and then may

recommend the death penalty. It has no further role to play in

sentencing. If the jury recommends death, the judge may impose

death or a term of not less than fourteen years. If the jury does

not recommend death, the judge may not impose death but only

imprisonment.

Illinois law prior to 1961 was similar to Arkansas law in that

the jury determined both the death sentence and the term of im

prisonment. It differed in that under Illinois law the jury had

to make a positive decision to fix the punishment at death, whereas

under the Arkansas law in effect in the case at bar, it had only

to find petitioner guilty of rape (without rendering a verdict of

life imprisonment), whereupon the death sentence became man

datory (398 P. 2d 138, 139). (Of the 22 pending Illinois capital

cases, two are subject to the pre-1961 law).

9

The 1874 codification preserved the purposes of the 1867

amendment, but the humanitarian history of the amend

ment was obscured.

In the century which has passed since 1867, our percep

tion of the world and of man has undergone a revolution.

The world of 1867, compared to today’s, was relatively

simple in its awareness of human motivation. It may have

been enough then to give the jury a choice of punishments.

The need for a two step procedure by which first to deter

mine guilt and then punishment doubtless was not per

ceived. Perhaps imprisonment was viewed as an act of

grace; perhaps it was felt that evidence on the guilt-inno

cence issue provided ample evidence as to punishment.

Whatever the reason in 1867, it is apparent today that a

new constitutional standard must be applied.

Today, largely because of the Fourteenth Amendment,

our vision of the criminal trial is clearer. There is ini

tially a need to determine whether the accused was respon

sible (in a physical, not a moral sense) for the death of

the deceased. Only after this determination has been made

adversely to the defendant, is it appropriate, indeed con

stitutional, to consider his punishment. The death penalty,

once routine, is today exceptional. Evidence in mitigation

ought constitutionally to relate to the full sweep of the

defendant’s personality and other relevant circumstances.

Yet how do we try a capital case before a jury? The

guilt-innocence question is center-stage. Often the crime

itself is horrible. The courtroom rings with detailed de

scriptions of the terrible scene. Graphic photographs may

be in evidence. Pathologists may report in dry but telling

terms of the damage to vital organs causing death.

10

I f the defense contends that the accused was not re

sponsible (again in a physical sense) for the death of the

deceased his defense will be confined to his alibi or other

defense. Throughout the trial it is unlikely that the jury

will have learned anything meaningful about the defen

dant. True, if the defense admits physical responsibility

for the death hut claims, for example, that the crime was

not murder but manslaughter, or that the defendant acted

in self-defense, or that he was incapable of forming the

requisite intent, or some other similar defense depending

upon the defendant’s state of mind, the jury may obtain

some picture of the defendant as a human being. Absent

this circumstance it is almost certain that the jury will

retire knowing almost nothing of the defendant relevant

to sentencing should they find him guilty. Indeed, if the

defendant exercises his constitutional privilege not to tes

tify, the jury may well never hear him speak a word

during the course of the trial.

True, again, the defendant has a theoretical right to in

troduce evidence in mitigation. To do so where the defense

is that he did not commit the crime, would surely undercut

that defense so severely that it could scarcely he risked.

No cautionary remarks from the Judge would overcome

the enormous handicap to the defense. Who would be

lieve a defendant who simultaneously declared his inno

cence and then asked a jury to show him mercy if it did

not believe his assurance of innocence?

Nor is that all. The attorney for the defense is unable

to make an effective plea for mercy because it too would

undercut the defense and also because there is no, or at

any rate, very little evidence in the record for mitigation.

Even where there is a “ state of mind” defense, e.g., that

11

the defendant reasonably acted in self-defense, it may be

inconsistent to argue for mercy while simultaneously con

tending that there were reasonable grounds to believe, for

example, that the deceased was about to make a deadly

assault upon the defendant.

But the prosecutor suffers scarcely any limitations. A

substantial portion of his case has been devoted to a

minute examination of the crime. The murder itself cries

out to the jurors. Perhaps he may not be able to intro

duce evidence solely for the purpose of showing aggrava

tion but in many cases, perhaps most, such evidence will

scarcely be needed because the crime itself effectively per

forms that task for the prosecutor.

Thus the jury retires to consider its verdict. On the

question of guilt or innocence its focus is necessarily upon

the crime where it properly belongs, but after reaching

its verdict of guilt its focus remains upon the crime in

determining punishment rather than shifting to the de

fendant and to the circumstances where it then belongs.

I f these were all of the inequities endured by the defen

dant they would be heavy enough, but they are not. Even

in a state such as Illinois which now permits a judge to

accept or reject a jury’s recommendation of death the

defendant goes before the judge carrying the burden of

such a recommendation, made in ignorance of the person

ality and life history of the defendant. Thus even in Illi

nois, where there is an opportunity to present evidence in

mitigation to a judge, the defendant enters the battle

for his life burdened with a constitutionally impermissible

handicap. On appeal, the Supreme Court of Illinois has

power to modify the sentence. (See Buie 615 (b) (4) of

12

the Rules of the Supreme Court of Illinois, which pro

vide that on appeal the reviewing court may “ reduce the

punishment imposed by the trial court.” ) The power to

mitigate, first enacted as Section 121-9 of the Code of

Criminal Procedure of 1963, has not been exercised by

the Supreme Court of Illinois in the six years that this

provision has been part of Illinois law. (See Point II,

pp. 14-20 below.) We cannot explain with certainty the re

luctance of the Supreme Court to reduce sentences, but

it may, at least in part, be because of the initial impetus

to the death sentence provided by an uninformed jury.

When the defendant comes before the Governor seeking

commutation, having exhausted his judicial remedies, he

again carries with him the burden of a jury recommenda

tion, now fortified by sentence, and affirmance on appeal.

(See further Point II, pp. 18-20 below.)

I f the unitary trial had been forced upon us by special

exigencies or as a compromise between conflicting values,

or for some other rational cause, it would be a serious

enough deprivation of constitutional rights. There are

no such reasons. In fact, the remedy for this gross evil

is plain and has already been adopted in a number of

states. We need only confine the trial initially to the guilt-

innocence question and ask the jury to rule upon it. If

the jury finds the defendant guilty, the prosecution and

defense can then introduce evidence in mitigation. It

seems clear to us that the sole reason we do not now

have such a procedure is because of the historical develop

ment outlined above. A practice originating prior to the

14th Amendment ought not to be retained when its evils

are manifest, the remedy plain, and the practice contrary

to due process.

13

The only grounds adduced hy the court below for re

fusing to require splitting of the issues are insubstantial.

The court below, 398 F. 2d at 150, relied upon its prior

decision in Pope v. U. S., 372 F. 2d 710, 727-730 (8th Cir.

1967). In Pope, the court held that a two stage trial was

not constitutionally required. It should be noted that Pope

admittedly shot three bank employees in the course of a

robbery, 372 F. 2d at 712; hence the trial centered essen

tially about the question of criminal responsibility.

Separation of the issues of guilt-innocence and penalty

is constitutionally necessary. Where we are concerned

not with life or death but simply with money judgments

in personal injury litigation, Civil Rule 21 of the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois

provides that there may be separate trials of the liability

and the damage issues. The damage issues may be tried

before the same jury or another jury. What we do in

personal injury litigation to achieve more exact justice,

surely we must do as a matter of constitutional necessity

when human life is at stake.

14

II.

Imposition of the death penalty in the absolute dis

cretion of the jury, uncontrolled by standards or direc

tion of any kind, violates due process.

The argument here was spelled out most persuasively

in the separate opinion of Mr. Justice Tobriner in In re

Anderson, 73 Cal. Eeptr. 21 at 36, 40-59. We add only the

following.

The Illinois statutes cited above, which are typical of

those in other states, require explicit agreement of jury

and court as a condition to imposition of death. Yet no

standard is provided by which they can determine whether

the death penalty is proper. As the Illinois Supreme Court

stated in People v. Bernette, 30 111. 2d 359, 197 N. E. 2d

463 (1964): “ The jury . . . was free to select or reject as

it saw fit.” Id. at 370.

111. Rev. Stat. ch. 38, sec. l-7 (g ) (1967) does provide

that the Court may hear evidence in mitigation before

deciding if death is proper. Such evidence may concern

the “moral character, life, family, occupation, and crim

inal record of the offender.” But nowhere in this statute

does a standard appear by which the jury or judge can

assess these very vague “mitigating circumstances.”

Illinois is not alone in allowing the jury unfettered dis

cretion in deciding whether to impose the death penalty or

not. All state legislatures which have not abolished the

death penalty have left complete discretion in the jury.*

* Ala. Code tit. 14, sec. 318 (1940); Ariz. Rev. Stat. sec. 13-453

(1956); Ark. Stat. Ann. secs. 41-2227, 43-2153 (1947); Cal. Pen.

Code sec. 190 (1955); Colo. Rev. Stat. ch. 40, art. 2-3 (1963);

15

There are no explicit standards to guide the jury. As

Kalven and Zeisel state: “ The discretion which the jury

in the United States is asked to exercise is, it should be

emphasized, striking: there is neither rule nor standard

to guide it . . . ” “ The American Jury and the Death

Penalty,” 33 U. Chi. L. Rev. 769, 770 (1966).

New York has limited capital punishment to murder of

a police officer or prison guard, N. Y. Penal Code sec. 1045,

but even as so limited the jury has complete discretion

in deciding whether to impose the death penalty. Some

states have classified murder by “ degrees.” But within the

highest degree which is punishable by death the jury has

no statutory or judicial standard by which it can guide

itself; e.g., Ala. Code tit. 14, secs. 314, 318 (1940); Idaho

Code secs. 18-4003, 18-4004 (1947); Ind. Stat. Ann. sec.

10-3401 (1956); Mo. Stat. Ann. sec. 559.030; Pa. Stat. Ann.

tit. 18, sec. 4701 (Purdon 1963).

Conn. Stat. Ann. sec. 53-10 (1958) ; Dela. Code Ann. tit. 11, sec.

571 (1953); Pla. Stat. secs. 782.04, 919.23 (1951); Ga. Code Ann.

sec. 26-1005 (1953); Idaho Code sec. 18-4004 (1947) ; 111. Rev.

Stat. ch. 38, secs. 9-1, l -7 (e ) ( l ) (1967); Ind. Ann. Stat. secs.

10-3401, 9-1819 (Burns 1956); Kan. Stat. Ann. sec. 21-403 (1964) ;

Ky. Rev. Stat. secs. 431.130. 435.010 (1948); La. Rev. Stat. tit. 14,

sec. 30, tit. 15, sec. 409 (1950); Md. Ann. Stat. Art. 27, sec. 413

(1957) ; Miss. Code Ann. sec. 2217 (1942) ; Mo. Stat. Ann. sec.

559.030 (1949); Mont. Rev. Code Ann. sec. 94-2505 (1947); Neb.

Rev. Stat. sec. 28-401 (1943) ; Nev. Rev. Stat. sec. 200.030 (1963) ;

N. H. Rev. Stat. Ann. sec. 585:4 (1955); N. J. Stat. Ann. tit. 2A,

ch. 113, sec. 4 (1953); N. M. Stat. Ann. ch. 40A, sec. 29-2 (1953);

N. Y. Penal Code sec. 1045; N. C. Gen. Stat. sec. 14-17 (1953);

Ohio Rev. Code tit. 29, sec. 2901.01 (1964); Okla. Stat. Ann. tit.

21, sec. 707 (1951) ; Pa. Stat. Ann. tit. 18, sec. 4701 (Purdon

1963) ; S. C. Code of Laws tit. 16, sec. 16-52 (1962); Tenn. Code

Ann. see. 39-2405 (1955); Tex. Pen. Code art. 1257 (1961) ; Wash.

Rev. Code Ann. tit. 9, sec. 9.48.030 (1961) ; Wyo. Stat. Ann. sec.

6-54; Mass. Laws Ann. ch. 265, sec. 2 (1956); S. D. Code of 1939

(1960 Supp.) Ch. 13.20, sec. 13.2012 (1960) ; Utah Code Ann. tit.

76, sec. 76-30-4 (1953); Vt. Stat, Ann. tit. 13, sec. 2303 (1959).

16

It thus appears that the jury is given no statutory or

judicial guides. What type of instructions must be given

to the jury to guide them! There are no Illinois cases

on this point but it seems well established by other courts

that the trial court need only instruct the jury that it has

discretion to decide what penalty should be imposed. Fail

ure to so instruct would be reversible error. Smith v.

State, 205 Ark. 1074, 172 S. W. 2d 248 (1943); State v.

Wilson, 151 Iowa 698, 141 N. W. 337 (1913); State v. Chris

tensen, 166 Kan. 152, 199 P. 2d 475 (1948); Commonwealth

v. Madaffer, 291 Pa. 270, 139 Atl. 875 (1927); Marshall v.

State, 33 Tex. 664 (1871); Bradshaw v. Commonwealth,

174 Ya. 391, 4 S. E. 2d 752 (1939); State v. Chaney, 117

W. Va. 605, 186 S. E. 607 (1936). But telling the jury of

its discretion is to do no more than repeat a statute which

is itself standardless. It has in fact been held that merely

reading or quoting the statute which grants discretion is

sufficient. Hernandez v. State, 43 Ariz. 424, 32 P. 2d 18

(1934); Howell v. State, 102 Ohio 411,131 N. E. 706 (1921).

Assuming that the jury finds the defendant guilty and

imposes the death penalty, and assuming that the trial

judge concurs, the Supreme Court of Illinois may, as we

have noted, reduce the penalty under Rule 615. But this

rule too provides no guidelines by which to judge the lower

court’s decision on the penalty.

The Illinois Supreme Court has taken a very limited

view of its power under this provision. Prior to Rule 615

and its statutory predecessor, in People v. Smith, 14 111. 2d

95, 97, 150 N. E. 2d 815 (1958), the Court said that a

reviewing court should not upset a sentence unless it clearly

appears that the penalty constitutes a great departure

17

from the spirit of the law or that the penalty is mani

festly in excess of the prescription of Sec. 2, Art. II of

the Illinois Constitution which requires penalties to be pro

portioned to the nature of the offense.*

Subsequent to adoption of the statute allowing sentence

reduction, the Court in People v. Taylor, 33 111. 2d 417,

211 N. E. 2d 673 (1965), admonished itself to proceed

with caution and circumspection in reducing sentences. The

trial judge, it observed, has superior opportunity to make

a sound determination concerning the punishment to be

imposed. In People v. Bonner, 37 111. 2d 553, 229 N. E. 2d

527 (1967), the Court stated that the imposition of sentence

was a matter of judicial discretion, and in absence of

manifest abuse of that discretion it will not be altered by

reviewing court. Although these cases were non-capital

cases, they demonstrate the reluctance of a reviewing court

in Illinois to reduce the penalty imposed by the trial court

even though reviewing courts are given that power by

statute. A case in which the Court said it would not reduce

the death penalty is People v. Meyers, 35 111. 2d 311, 220

N. E. 2d 297 (1966) cert. den. 87 S. Ct. 752, 385 U. S. 1019,

17 L. Ed. 2d 557. The Court characterized the crime as

“brutal” and “ atrocious” .

* People v. Dukes, 12 111. 2d 334, 146 N. E. 2d 14 (1957) was a

capital case. The Court said that where the charge is murder, a

jury has wide discretion in fixing the punishment. It added that

when the jury in the exercise of that discretion inflicts the death

penalty, it could not affirm the judgment even though proof of

guilt is clear, if prejudicial error occurred in the trial. This seems

to give the defendant some protection; but it is protection only

from the possibility that the jury may have decided to impose the

death penalty because of the prejudicial error. If there were no

prejudicial error, the court would defer to the “wide discretion”

of the jury and would not change the penalty.

18

Every murder is “brutal and atrocious.” Our concern

should be not with the crime, but with the criminal. Lack

ing standards to turn to, the Court looked to the deed,

rather than to the doer. The case demonstrates the evil

of a path unilluminated by statutory guides.

The absence of standards continues to affect the defen

dant even when he seeks executive clemency. There too

clemency may be granted or withheld without statutory or

constitutional guide.

Article 5, see. 13 of the Constitution of Illinois provides:

“ The governor shall have power to grant reprieves,

commutations and pardons, after conviction, for all

offenses, subject to such regulations as may be pro

vided by law relative to the manner of applying there

for.”

Several Illinois cases have considered the Governor’s

power of commutation. In People v. Jenkins, 325 111. 372,

156 N. E. 290 (1927), the court held, “ [t]he only restric

tion which the Legislature may impose on the Governor’s

power refers to the regulations relative to the manner of

applying for reprieves, commutations, and pardons, and

the act on that subject does not purport to and does not,

restrict the Governor’s authority except to that extent.”

325 111. at 375, 156 N. E. at 291.

The exclusive discretion of the Governor in matters of

commutation, without judicial review or legislative control,

is practically a universal rule. With only one exception,*

* In McGee v. Arizona State Board of Pardons and Paroles, 92

Ariz. 317, 376 P. 2d 779 (1962), the Arizona Supreme Court held

that a condemned defendant had a right to, and compelled the

board to grant, a full due process hearing despite the absence of

19

those courts which have been presented with the issue have

held that the actions of the clemency authority are not

within the purview of due process, and are not subject to

challenge in the courts. Executive Clemency in Capital

Cases, 39 N. Y. U. Law R. 136, 178 (1964). The Supreme

Court of Oregon, in Eacret v. Holmes, 215 Ore. 121, 333

P. 2d 741, 744 (1958), held:

“ Where the constitution thus confers unlimited power

on the Governor to grant reprieves, commutations and

pardons, his discretion cannot be controlled by judicial

decision. The courts have no authority to inquire into

the reasons or motives which actuate the Governor

in exercising the power, nor can they decline to give

effect to a pardon for an abuse of power.”

As authorities for this general proposition, the Oregon

court cited: In re Opinion of Justices, 120 Mass. 600

(1876); State v. Harrison, 122 S. C. 523, 115 S. E. 746

(1923) ; Martin v. State, 21 Tex. App. 1, 17 S. W. 430

(1886); People ex rel. Page v. Brophy, 248 App. Div. 309,

289 N. Y. S. 362 (1936); Ex parte Grossman, 267 U. S. 87

(1924) ; Jamison v. Flanner, 116 Kan. 624, 228 P. 82 (1924);

Montgomery v. Cleveland, 134 Miss. 132, 98 So. I l l (1923);

16 C. J. S. Const. Law’ sec. 157, p. 830.

Although the author of Executive Clemency in Capital

Cases, 39 N. Y. U. Law Rev. 136, 159-177 (1964), found

any constitutional, statutory, or regulatory provision for a hear

ing. Under the court’s construction, the defendant would have to

be provided with notice, an opportunity to be heard, an oppor

tunity to present witnesses, and an opportunity to present evidence

mitigating circumstances. The court held due process required

this result, but nowhere specified whether the federal Constitution

or the state constitution was the source of this right.

20

that clemency authorities sometimes referred to such

“ standards” as the nature of the crime, fairness of the

trial, mitigating circumstances, doubt as to guilt, mental

and physical condition of defendant, recommendations of

prosecutor and trial judge, and political pressure and pub

licity, it is plain that these “ standards” still cannot be

reviewed by a court or be imposed by the legislature.

The totally unfettered discretion given to the Governor,

although tending to eliminate some of the harshness of

capital punishment, has thus resulted in the creation of

a system with no standards.

Amici do not argue that the Governor should he limited

in exercising his power of communication. Since he is the

last resort open to one sentenced to death, he should

have the widest possible discretion in making such a deci

sion. We call attention to this point to emphasize that a

man may go to his death and yet at no place in the elab

orate judicial and executive machinery is there a legislative

or case law standard set for judging who shall live and who

shall die. Such situation is repugnant to due process.

21

CONCLUSION

What this court said in Witherspoon v. Illinois respect

ing a “hanging jury” applies with equal force to the issues

of dividing the guilt-innocence and penalty determinations,

and the issue of lack of legislative and case law standards:

“ The State . . . has stacked the deck against the

petitioner. To execute this death sentence would de

prive him of his life without due process of law.” 391

IT. S. at 510, 521.

Respectfully submitted,

E lmer Gertz

120 South La Salle Street

Suite 1805

Chicago, Illinois 60603

W illard J. L assers

11 South La Salle Street

Suite 3400

Chicago, Illinois 60603

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

January 1969

RECORD PRESS, INC. — 95 Morion Street — New York, N. Y. 10014 — (212) 243-5775

■ĝ lpaiP 38