Bell v. Wolfish Slip Opinion and Syllabus

Public Court Documents

May 14, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bell v. Wolfish Slip Opinion and Syllabus, 1979. 54507ba3-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a61ea738-8c72-4519-8510-6c119071d866/bell-v-wolfish-slip-opinion-and-syllabus. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

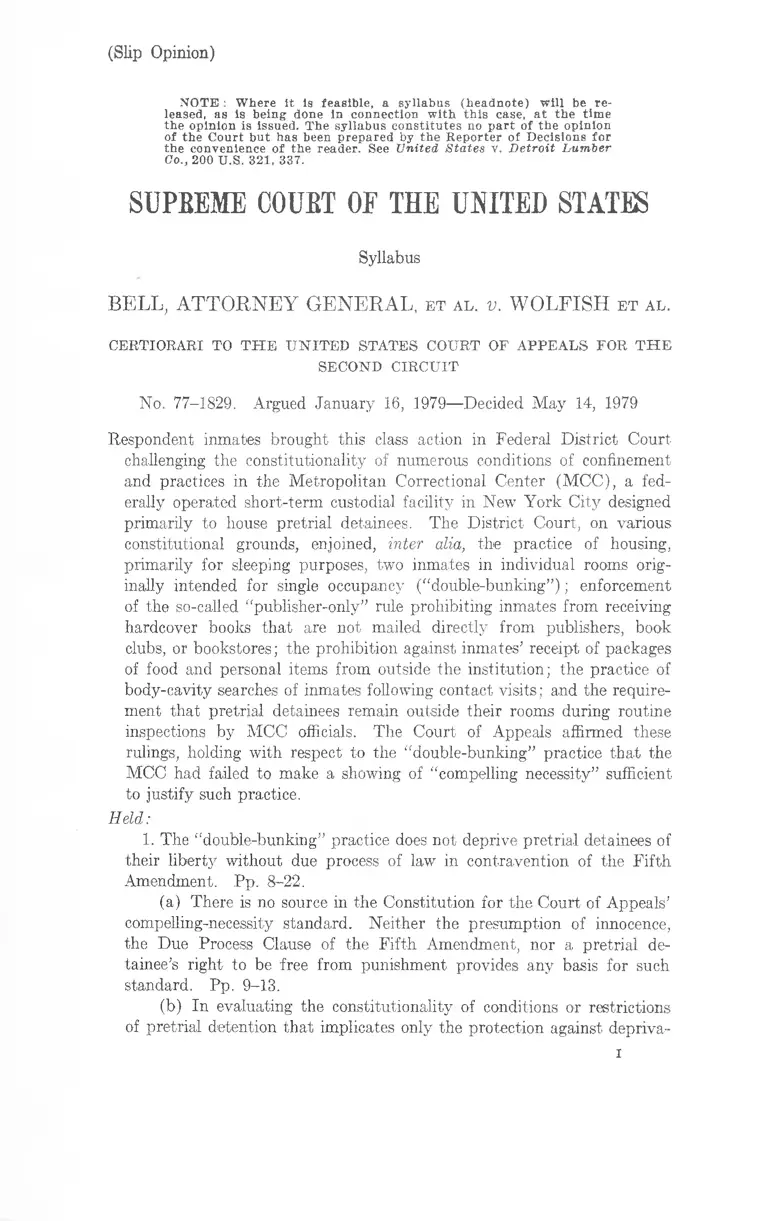

(Slip Opinion)

NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be re

leased, as is being done in connection w ith th is case, a t the time

the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no p a rt of the opinion

of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for

the convenience of the reader. See United S ta tes v. D etroit Lumber

Go., 200 U.S. 321, 337.SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

BELL, ATTORNEY GENERAL, e t a l . v . WOLFISH e t a l .

CERTIORARI TO TH E UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR T H E

SECOND CIRCUIT

No. 77-1829. Argued January 16, 1979—Decided May 14, 1979

Respondent inmates brought this class action in Federal District Court

challenging the constitutionality of numerous conditions of confinement

and. practices in the Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC), a fed

erally operated short-term custodial facility in New York City designed

primarily to house pretrial detainees. The District Court, on various

constitutional grounds, enjoined, inter alia, the practice of housing,

primarily for sleeping purposes, two inmates in individual rooms orig

inally intended for single occupancy (“double-bunking”) ; enforcement

of the so-called “publisher-only” rule prohibiting inmates from receiving

hardcover books that are not mailed directly from publishers, book

clubs, or bookstores; the prohibition against inmates’ receipt of packages

of food and personal items from outside the institution; the practice of

body-cavity searches of inmates following contact visits; and the require

ment that pretrial detainees remain outside their rooms during routine

inspections by MCC officials. The Court of Appeals affirmed these

rulings, holding with respect to the “double-bunking” practice that the

MCC had failed to make a showing of “compelling necessity” sufficient

to justify such practice.

Held:

1. The “double-bunking” practice does not deprive pretrial detainees of

their liberty without due process of law in contravention of the Fifth

Amendment. Pp. 8-22.

(a) There is no source in the Constitution for the Court of Appeals’

compelling-necessity standard. Neither the presumption of innocence,

the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, nor a pretrial de

tainee’s right to be free from punishment provides any basis for such

standard. Pp. 9-13.

(b) In evaluating the constitutionality of conditions or restrictions

of pretrial detention that implicates only the protection against depriva-

i

II BELL v. WOLFISH

Syllabus

tion of liberty without due process of law, the proper inquiry is whether

those conditions or restrictions amount to punishment of the detainee.

Absent a showing of an expressed intent to punish, if a particular con

dition or restriction is reasonably related to a legitimate nonpunitive

governmental objective, it does not, without more, amount to “punish

ment,” but, conversely, if a condition or restriction is arbitrary or pur

poseless, a court may permissibly infer that the purpose of the govern

mental action is punishment that may not constitutionally be inflicted

upon detainees qua detainees. In addition to ensuring the detainees’

presence at trial, the effective management of the detention facility once

the individual is confined is a valid objective that may justify imposi

tion of conditions and restrictions of pretrial detention and dispel any

inference that such conditions and restrictions are intended as punish

ment. Pp. 13-19.

(c) Judged by the above analysis and on the record, “double-

bunking” as practiced at the MCC did not, as a matter of law,

amount to punishment and henoe did not violate respondents’ rights

under the Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. While “double-

bunking” may have taxed some of the equipment or particular facilities

in certain of the common areas in the MCC, this does not mean that

the conditions at the MCC failed to meet the standards required by

the Constitution, particularly where it appears that nearly all pretrial

detainees are released within 60 days. Pp. 19-22.

2. Nor do the “publisher-only” rule, body-cavity searches, the pro

hibition against the receipt of packages, or the room-search rule violate

any constitutional guarantees. Pp. 22-40.

(a) Simply because prison inmates retain certain constitutional

rights does not mean that these rights are not subject to restrictions

and limitations. There must be a “mutual accommodation between

institutional needs and objectives and the provisions of the Constitution

that are of general application,” Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U. S. 539, 556,

and this principle applies equally to pretrial detainees and convicted

prisoners. Maintaining institutional security and preserving internal

order and discipline are essential goals that may require limitation or

retraction of the retained constitutional rights of both convicted pris

oners and pretrial detainees. Since problems that arise in the day-to-

day operation of a corrections facility are not susceptible of easy solu

tions, prison administrators should be accorded wide-ranging deference

in the adoption and execution of policies and practices that in their

judgment are needed to preserve internal order and discipline and to

maintain institutional security. Pp. 22-27.

BELL v. WOLFISH hi

Syllabus

(b) The “publisher-only” rule does not violate the First Amendment

rights of MCC inmates but is a rational response by prison officials to

the obvious security problem of preventing the smuggling of contraband

in books sent from outside. Moreover, such rule operates in a neutral

fashion, without regard to the content of the expression, there are

alternative means of obtaining reading material, and the rule’s impact

on pretrial detainees is limited to a maximum period of approximately

60 days. Pp. 27-31.

(c) The restriction against the receipt of packages from outside the

facility does not deprive pretrial detainees of their property without

due process of law in contravention of the Fifth Amendment, especially

in view of the obvious fact that such packages are handy devices for

the smuggling of contraband. Pp. 31-33.

(d) Assuming that- a pretrial detainee retains a diminished expec

tation of privacy after commitment to a custodial facility, the room-

search rule does not violate the Fourth Amendment but simply facili

tates the safe and effective performance of the searches and thus does

not render the searches “unreasonable” within the meaning of that

Amendment. Pp. 33-36.

(e) Similarly, assuming that pretrial detainees retain some Fourth

Amendment rights upon commitment to a corrections facility, the body-

cavity searches do not violate that Amendment. Balancing the sig

nificant and legitimate security interests of the institution against the

inmates’ privacy interests, such searches can be conducted on less than

probable cause and are not unreasonable. Pp. 36-39.

(f) None of the security restrictions and practices described above

constitute “punishment” in violation of the rights of pretrial detainees

under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment. These restric

tions and practices were reasonable responses by MCC officials to legiti

mate security concerns, and, in any event, were of only limited duration

so far as the pretrial detainees were concerned. Pp. 39-40.

573 F. 2d 118, reversed and remanded.

R ehnquist, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which Burger,

C. J., and Stewart, White , and Blackmun, J.J., joined. P owell, J.,

filed an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part. M arshall, J.,

filed a dissenting opinion. Stevens, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which

Brennan, J., joined.

NOTICE : This opinion is subject to form al revision before publication

in the prelim inary p rin t of the United S tates Reports. Readers are re

quested to notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the

United S tates, W ashington, D.C. 20543, of any typographical or other

form al errors, in order th a t corrections may be made before the pre

lim inary p rin t goes to press.SUPKEME COUET OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 77-1829

Griffin B. Bell et al., Petitioners,

v.

Louis Wolfish et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of

Appeals for the Second

Circuit.

[May 14, 1979]

Mr. J u s t ic e R e h n q u i s t delivered the opinion of the Court.

Over the past five Terms, this Court- has in several decisions

considered constitutional challenges to prison conditions or

practices by convicted prisoners.1 This case requires us to

examine the constitutional rights of pretrial detainees—those

persons who have been charged with a crime but who have

not yet been tried on the charge. The parties concede that

to ensure their presence at trial, these persons legitimately

may be incarcerated by the Government prior to a deter

mination of their guilt or innocence, infra, at 12-13 and n. 15;

see 18 U. S. C. §§ 3146, 3148, and it is the scope of their rights

during this period of confinement prior to trial that is the

primary focus of this case.

This lawsuit was brought as a class action in the United

States District Court for the Southern District of New York

to challenge numerous conditions of confinement and prac

tices at the Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC), a fed

erally operated short term custodial facility in New York

City designed primarily to house pretrial detainees. The

1 See, e. g., Hutto v. Finney, 437 U. S. 678 (1978); Jones v. North Caro

lina Prisoners’ Labor Union, 433 U. S. 119 (1977); Bounds v. Smith, 430

II. S. 817 (1977); Meachum v. Fano, 427 U. S. 215 (1976); Wolff v.

McDonnell, 418 U. S. 539 (1974); Pell v. Procunier, 417 U. S. 817 (1974);

Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U. S. 396 (1974).

2 BELL v. WOLFISH

District Court, in the words of the Court of Appeals for the

Second Circuit, “intervened broadly into almost every facet

of the institution” and enjoined no fewer than 20 MCC

practices on constitutional and statutory grounds. The Court

of Appeals largely affirmed the District Court’s constitutional

rulings and in the process held that under the Due Process

Clause of the Fifth Amendment, pretrial detainees may “be

subjected to only those ‘restrictions and privations’ which

‘inhere in their confinement itself or which are justified by

compelling necessities of jail administration.’ ” Wolfish v.

Levi, 573 F 2d 118, 124 (1978), quoting Rhem v. Malcolm,

507 F. 2d 333, 336 (CA2 1974). We granted certiorari to

consider the important constitutional questions raised by these

decisions and to resolve an apparent conflict among the

circuits.2 ----U. S .-----(1978). We now reverse.

I

The MCC was constructed in 1975 to replace the converted

waterfront garage on West Street that had served as New

York City’s federal jail since 1928. It is located adjacent to

the Foley Square federal courthouse and has as its primary

objective the housing of persons who are being detained in

custody prior to trial for federal criminal offenses in the

United States District Courts for the Southern and Eastern

Districts of New York and for the District of New Jersey.

Under the Bail Reform Act, 18 U. S. C. § 3146, a person in the

federal system is committed to a detention facility only because

no other less drastic means can reasonably ensure his presence

2 See, e. g., Norris v. Frame, ---F. 2 d ----- (CAS, filed Oct. 31, 197S)

(No. 78-1090); Campbell v. Magruder,----U. S. App. D. C. ■— , 5S0 F.

2d 521 (1978); Wolfish v. Levi, 573 F. 2d 118 (CA2 1978): Feeley v.

Sampson, 570 F. 2d 364 (CA1 1978); Main Road v. Aytch, 565 F. 2d 54

(CA3 1977); Patterson v. Morrisette, 564 F. 2d 1109 (CA4 1977); Miller

v. Carson, 563 F. 2d 741 (CA5 1977); Duran v. Elrod, 542 F. 2d 998 (CA7

1976).

BELL v. WOLFISH 3

at trial. In addition to pretrial detainees, the MCC also houses

some convicted inmates who are awaiting sentencing or trans

portation to federal prison or who are serving generally

relatively short sentences in a service capacity at the MCC,

convicted prisoners who have been lodged at the facility under

writs of habeas corpus ad prosequendum or ad testificandum

issued to ensure their presence at upcoming trials, witnesses in

protective custody and persons incarcerated for contempt.3

The MCC differs markedly from the familiar image of a

jail; there are no barred cells, dank, colorless corridors, or

clanging steel gates. It was intended to include the most

advanced and innovative features of modern design of detention

facilities. As the Court of Appeals stated: “ [I]t represented

the architectural embodiment of the best and most progressive

penological planning.” 573 F. 2d, at 121. The key design

element of the 12-story structure is the “modular” or “unit”

concept, whereby each floor designed to house inmates has one

or two largely self-contained residential units that replace the

traditional cellblock jail construction. Each unit in turn has

several clusters or corridors of private rooms or dormitories

radiating from a central 2-story “multipurpose” or common

room, to which each inmate has free access approximately 16

hours a day. Because our analysis does not turn on the

particulars of the MCC concept or design, we need not discuss

them further.

When the MCC opened in August 1975, the planned capac

ity was 449 inmates, an increase of 50% over the former West

3 This group of nondetainees may comprise, on a daily basis, between 40

and 60% of the MCC population. United States ex rel. Wolfish v. United

States, 428 F. Supp. 333, 335 (SDNY 1977). Prior to the District

Court’s order, 50% of all MCC inmates spent less than 30 days at the

facility and 73% less than 60 days. United States ex rel. Wolfish v. Levi,

439 F. Supp. 114, 127 (SDNY 1977). However, of the unsentenced

detainees, over half spent less than 10 days at the MCC, three-quarters

were released within a month and more than 85% were released within 60

days. Wolfish v. Levi, supra, at 129 n. 25.

4 BELL v. WOLFISH

Street facility. Id., at 122. Despite some dormitory accom

modations, the MCC was designed primarily to house these

inmates in 389 rooms, which originally were intended for single

occupancy. While the MCC was under construction, how

ever, the number of persons committed to pretrial detention

began to rise at an “unprecedented rate.” Ibid. The Bureau

of Prisons took several steps to accommodate this unexpected

flow of persons assigned to the facility, but despite these

efforts, the inmate population at the MCC rose above its

planned capacity within a short time after its opening. To

provide sleeping space for this increased population, the MCC

replaced the single bunks in many of the individual rooms

and dormitories with double bunks.4 Also, each week some

newly arrived inmates had to sleep on cots in the common

areas until they could be transferred to residential rooms as

space became available. See 573 F. 2d, at 127-128.

On November 28, 1975, less than four months after the

MCC had opened, the named respondents initiated this action

by filing in the District Court a petition for a writ of habeas

corpus.5 The District Court certified the case as a class

4 Of the 389 residential rooms at the MCC, 121 had been “designated”

for double-bunking at the time of the District Court’s order. 428 F.

Supp., at 336. The number of rooms actually housing two inmates, how

ever, never exceeded 73 and, of these, only 35 were rooms in units that

housed pretrial detainees. Brief for Petitioners 7 n. 6, Brief for Respond

ents 11-12; App. 33-35 (Affidavit of Larry Taylor, MCC Warden, dated

Dec. 29, 1976).

5 It appears that the named respondents may now have been trans

ferred or released from the MCC. See United States ex rel. Wolfish v.

Levi, 439 F. Supp., at 119. “This case belongs, however, to that narrow

class of cases in which the termination of a class representative’s claim does

not moot the claims of the unnamed members of the class.” Gerstein v.

Pugh, 420 U. S. 103, 110 n. 11 (19/5); see Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U. S. 393

(1975). The named respondents had a case or controversy at the time the

complaint was filed and at the time the class action was certified by the

District Court pursuant to Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 23, and there remains a

live controversy between petitioners and the members of the class repre

sented by the named respondents. See Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U. S., at 402.

BELL v. WOLFISH 5

action on behalf of all persons confined at the MCC, pretrial

detainees and sentenced prisoners alike.6 The petition served

up a veritable potpourri of complaints that implicated vir

tually every facet of the institution’s conditions and practices.

Respondents charged, inter alia, that they had been deprived

of their statutory and constitutional rights because of over

crowded conditions, undue length of confinement, improper

searches, inadequate recreational, educational and employ

ment opportunities, insufficient staff and objectionable re

strictions on the purchase and receipt of personal items and

books.7

Finally, because of the temporary nature of confinement at the MCC, the

issues presented are, as in Sosna and Gerstein, “capable of repetition, yet

evading review.” 420 U. S., at 110 n. 11; 419 U. S., at 400-401; see

Kremens v. Bartley, 431 U. S. 119, 133 (1977). Accordingly, the require

ments of Art. I l l are met and the case is not moot.

6 Petitioners apparently never contested the propriety of respondents’ use

of a writ of habeas corpus to challenge the conditions of their confinement

and petitioners do not raise that question in this Court. However,

respondents did plead an alternative basis for jurisdiction in their

“Amended Petition” in the District Court—namely, 28 U. S. C. § 1361—

that arguably provides jurisdiction. And, at the time of the relevant-

orders of the District Court in this case, jurisdiction would have been

provided by 28 U. S. C. § 1331 (a), as amended, 90 Stat. 2721. Thus,

we leave to another day the question of the propriety of using a

writ of habeas corpus to obtain review of the conditions of confinement,

as distinct from the fact or length of the confinement itself. See Preiser v.

Rodriguez, 411 U. S. 475, 499-500 (1973). See generally Lake Country

Estates, Inc. v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, ---- U. S. ---- (1979).

Similarly, petitioners do not contest the District Court’s certification of

this case as a class action. For much the same reasons as identified above,

there is no need in this case to reach the question whether Fed. Rule Civ.

Proc. 23, providing for class actions, is applicable to petitions for habeas

corpus relief. Accordingly, we express no opinion as to the correctness of

the District Court’s action in this regard. See Middendorj v. Henry, 425

U. S. 25, 30 (1976).

7 The Court of Appeals described the breadth of this action as follows:

“As an indication of the scope of this action, the amended petition also

decried the inadequate phone service; ‘strip’ searches; room searches outside

6 BELL v. WOLFISH

In two opinions and a series of orders, the District Court

enjoined numerous MCC practices and conditions. With

respect to pretrial detainees, the court held that because they

are “presumed to be innocent and held only to ensure their

presence at trial, ‘any deprivation or restriction of ... . rights

beyond those which are necessary for confinement alone, must

be justified by a compelling necessity.’ ” 439 F. Supp., at 124,

quoting Detainees of Brooklyn House of Detention v. Mal

colm, 520 F. 2d 392, 397 (CA2 1975). And while acknowl

edging that the rights of sentenced inmates are to be measured

by the different standard of the Eighth Amendment, the court

declared that to house “an inferior minority of persons . . .

in ways found unconstitutional for the rest” would amount

to cruel and unusual punishment. 428 F. Supp., at 339.8

Applying these standards on cross-motions for partial sum

mary judgment, the District Court enjoined the practice of

housing two inmates in the individual rooms and prohibited

enforcement of the so-called “publisher-only” rule, which at

the time of the court’s ruling prohibited the receipt of all

books and magazines mailed from outside the MCC except

those sent directly from a publisher or a book club.9 After a

the inmate’s presence; a prohibition against the receipt of packages or the

use of personal typewriters; interference with, and monitoring of, personal

mail; inadequate and arbitrary disciplinary and grievance procedures;

inadequate classification of prisoners; improper treatment of non-English

speaking inmates; unsanitary conditions; poor ventilation; inadequate and

unsanitary food; the denial of furloughs, unannounced transfers; improper

restrictions on religious freedom; and an insufficiently trained staff.” 573

F. 2d, at 123 n. 7.

8 While most of the District Court’s rulings were based on constitutional

grounds, the court also held that some of the actions of the Bureau of

Prisons were subject to review under the Administrative Procedure Act

(APA) and were “arbitrary and capricious” within the meaning of the

APA. 439 F. 2d, at 122-123, 141; see n. 11, infra.

9 The District Court also enjoined confiscation of inmate property by

prison officials without supplying a receipt and, except under specified cir

cumstances, the reading and inspection of inmates’ outgoing and incoming

mail. 428 F. Supp., at 341-344. Petitioners do not challenge these rulings.

BELL v. WOLFISH 7

trial on the remaining issues, the District Court enjoined, inter

alia, the doubling of capacity in the dormitory areas, the use

of the common rooms to provide temporary sleeping accom

modations, the prohibition against inmates’ receipt of packages

containing food and items of personal property, and the prac

tice of requiring inmates to expose their body cavities for

visual inspection following contact visits. The Court also

granted relief in favor of pretrial detainees, but not convicted

inmates, with respect to the requirement that detainees remain

outside their rooms during routine inspections by MCC

officials.10

The Court of Appeals largely affirmed the District Court’s

rulings, although it rejected that court’s Eighth Amendment

analysis of conditions of confinement for convicted prisoners

because the “parameters of judicial intervention into . . .

conditions . . . for sentenced prisoners are more restrictive than

in the case of pretrial detainees.” 573 F. 2d, at 125.11 Ae-

10 The District Court also granted respondents relief on the following

issues: classification of inmates and movement between units; length of

confinement; law library facilities; the commissary; use of personal type

writers; social and attorney visits; telephone service; inspection of

inmates’ mail; inmate uniforms; availability of exercise for inmates in

administrative detention; food service; access to the bathroom in the

visiting area; special diets for Muslim inmates; and women’s “lock-in.”

439 F. Supp., at 125-165. None of these rulings are before this Court.

11 The Court of Appeals held that “ [a]n institution’s obligation under

the eighth amendment is at an end if it furnishes sentenced prisoners with

adequate food, clothing, shelter, sanitation, medical care, and personal

safety.” 573 F. 2d, at 125.

The Court of Appeals also held that the District Court’s reliance on the

APA was erroneous. See n. 8, supra. The Court of Appeals concluded

that because the Bureau of Prisons’ enabling legislation vests broad dis

cretionary powers in the Attorney General, the administration of federal

prisons constitutes “ ‘agency action . . . committed to agency discretion by

law’ ” that is exempt from judicial review under the APA, at least in the

absence of a breach of a specific statutory mandate. 573 F. 2d, at 125;

see 5 U. S. C. §701 (a)(2). Because of its holding that the APA was

inapplicable to this case, the Court of Appeals reversed the District

Court’s rulings that the bathroom in the visiting area must be kept un-

8 BELL v. WOLFISH

cordingly, the court remanded the matter to the District

Court for it to determine whether the housing for sentenced

inmates at the MCC was constitutionally “adequate.” But

the Court of Appeals approved the due process standard em

ployed by the District Court in enjoining the conditions of

pretrial confinement. I t therefore held that the MCC had

failed to make a showing of “compelling necessity” sufficient

to justify housing two pretrial detainees in the individual

rooms. 573 F. 2d, at 126-127. And for purposes of our review

(since petitioners challenge only some of the Court of Appeals’

rulings), the court affirmed the District Court’s granting of

relief against the “publisher-only” rule, the practice of conduct

ing body cavity searches after contact visits, the prohibition

against receipt of packages of food and personal items from

outside the institution, and the requirement that detainees

remain outside their rooms during routine searches of the

rooms by MCC officials. Id., at 129-132.12

II

As a first step in our decision, we shall address “double-

locked, that prison officials must make a certain level of local and long

distance telephone service available to MCC inmates, that the MCC must

maintain unchanged its present schedule for social visits, and that the

MCC must take commissary requests every other day. 573 F. 2d, at

125-126, and n. 16. Respondents have not cross-petitioned from the

Court of Appeals’ disposition of the District Court’s Eighth Amendment

and APA rulings.

12 Although the Court of Appeals held that doubling the capacity of the

dormitories was unlawful, it remanded for the District Court to determine

“whether any number of inmates in excess of rated capacity could be

suitably quartered within the dormitories.” 573 F. 2d, at 128. In view

of the changed conditions resulting from this litigation, the court, also

remanded to the District Court for reconsideration of its order limiting

incarceration of detainees at the MCC to a period less than 60 days. Id.,

at 129. The court reversed the District Court’s rulings that inmates be

permitted to possess typewriters for their personal use in their rooms and

that inmates not be required to wear uniforms. Id., at 132-133. None of

these rulings are before the Court.

BELL v. WOLFISH 9

bunking” as it is referred to by the parties, since it is a con

dition of confinement that is alleged only to deprive pretrial

detainees of their liberty without due process of law in

contravention of the Fifth Amendment. We will treat in

order the Court of Appeals’ standard of review, the analysis

which we believe the Court of Appeals should have employed,

and the conclusions to which our analysis leads us in the case

of double-bunking.

A

The Court of Appeals did not dispute that the Government

may permissibly incarcerate a person charged with a crime

but not yet convicted to ensure his presence at trial. How

ever, reasoning from the “premise that an individual is to be

treated as innocent until proven guilty,” the court concluded

that pretrial detainees retain the “rights afforded unincar

cerated individuals,” and that therefore it is not sufficient that

the conditions of confinement for pretrial detainees “merely

comport with contemporary standards of decency prescribed

by the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the eighth

amendment.” 573 F. 2d, at 124. Rather, the court held, the

Due Process Clause requires that pretrial detainees “be sub

jected to only those ‘restrictions and privations’ which ‘inhere

in their confinement itself or which are justified by compelling

necessities of jail administration.’ ” Ibid., quoting Rhem v.

Malcolm, 507 F. 2d, at 336. Under the Court of Appeals’

“compelling necessity” standard, “deprivation of the rights

of detainees cannot be justified by the cries of fiscal neces

sity, . . . administrative convenience, .. . or by the cold comfort

that conditions in other jails are worse.” 573 F. 2d, at 124

(citations omitted). The court acknowledged, however, that

it could not “ignore” our admonition in Procunier v. Martinez,

416 U. S. 396, 405 (1974), that “courts are ill-equipped to

deal with the increasingly urgent problems of prison adminis

tration,” and concluded that it would “not [be] wise for [it]

10 BELL v. WOLFISH

to second-guess the expert administrators on matters on which

they are better informed.” 573 F. 2d, at 124.13

Our fundamental disagreement with the Court of Appeals is

that we fail to find a source in the Constitution for its com

pelling necessity standard.14 Both the Court of Appeals and

the District Court seem to have relied on the “presumption of

innocence” as the source of the detainee’s substantive right to

be free from conditions of confinement that are not justified

by compelling necessity. 573 F. 2d, at 124; 439 F. Supp., at

124; accord, Campbell v. Magruder, —- U. S. App. D. C. — -,

13 The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., as amicus

curiae, argues that federal courts have inherent authority to correct condi

tions of pretrial confinement and that the practices at issue in this case

violate the Attorney General’s alleged duty to provide inmates with

“suitable quarters” under 18 U. S. C. §4042 (2). Brief for the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., at Amicus Curiae 22-46.

Neither argument was presented to or passed on by the lower courts; nor

have they been urged by either party in this Court. Accordingly, we have

no occasion to reach them in this case. Knetsch v. United States, 364

U. S. 361, 370 (1960).

14 As authority for its compelling necessity test, the court cited three of

its prior decisions, Rhem v. Malcolm, 507 F. 2d 333 (CA2 1974) (Rhem I ) ;

Detainees of Brooklyn House of Detention v. Malcolm, 520 F. 2d 392

(CA2 1975), and Rhem v. Malcolm, 527 F. 2d 1041 (CA2 1975) {RhemII) .

Rhem I ’s support for the compelling necessity test came from Brenneman

v. Madigan, 343 F. Supp. 128, 142 (ND Cal. 1972), which in turn cited

no cases in support of its statement of the relevant test. Detainees found

support for the compelling necessity standard in Shapiro v. Thompson,

394 U. S. 618 (1969), Tate v. Short, 401 U. S. 395 (1971), Williams v.

Illinois, 399 U. S. 235 (1970), and Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479

(1960). But Tate and Williams dealt with equal protection challenges to

imprisonment based on inability to pay fines or costs. Similarly, Shapiro

concerned equal protection challenges to state welfare eligibility require

ments found to violate the constitutional right to travel. In Shelton, the

Court held that a school board policy requiring disclosure of personal asso

ciations violated the First and Fourteenth Amendment rights of a teacher.

None of these cases support the court’s compelling necessity test. Finally,

Rhem II merely relied on Rhem I and Detainees.

BELL v. WOLFISH 11

580 F. 2d 521, 529 (1978); Detainees of Brooklyn House of

Detention v. Malcolm, 520 F. 2d 392, 397 (CA2 1975); Rhem

v. Malcolm, 507 F. 2d 333, 336 (CA2 1974). But see Feeley v.

Sampson, 570 F. 2d 364, 369 n. 4 (CA1 1978); Hampton v.

Holmesburg Prison Officials, 546 F. 2d 1077, 1080 n. 1 (CAS

1976). But the presumption of innocence provides no sup

port for such a rule.

The presumption of innocence is a doctrine that allocates

the burden of proof in criminal trials; it also may serve as an

admonishment to the jury to judge an accused’s guilt or inno

cence solely on the evidence adduced at trial and not on the

basis of suspicions that may arise from the fact of his arrest,

indictment or custody or from other matters not introduced

as proof at trial. Taylor v. Kentucky, 436 U. S. 478, 485

(1978); see Estelle v. Williams, 425 U. S. 501 (1976); In re

Winship, 397 U. S. 358 (1970); 9 J. Wigmore, Evidence § 2511

(3d ed. 1940). It is “an inaccurate, shorthand description

of the right of the accused to ‘remain inactive and secure,

until the prosecution has taken up its burden and produced

evidence and effected persuasion . . . ’ [; an] ‘assumption’ that

is indulged in the absence of contrary evidence.” Taylor v.

Kentucky, supra, at 483-484, n. 12. Without question, the

presumption of innocence plays an important role in our

criminal justice system. “The principle that there is a pre

sumption of innocence in favor of the accused is the undoubted

law, axiomatic and elementary, and its enforcement lies at

the foundation of the administration of our criminal law.”

Coffin V. United States, 156 U. S. 432, 453 (1895). But it has

no application to a determination of the rights of a pretrial

detainee during confinement before his trial has even begun.

The Court of Appeals also relied on what it termed the

“indisputable rudiments of due process” in fashioning its com

pelling necessity test. We do not doubt that the Due Process

Clause protects a detainee from certain conditions and restric

tions of pretrial detainment. See infra, at 13-19. Nonetheless,

12 BELL v. WOLFISH

that clause provides no basis for application of a compelling

necessity standard to conditions of pretrial confinement that

are not alleged to infringe any other, more specific guarantee

of the Constitution.

It is important to focus on what is at issue here. We are

not concerned with the initial decision to detain an accused

and the curtailment of liberty that such a decision necessarily

entails. See Gerstein v. Pugh, 420 U. S. 103, 114 (1975);

United States v. Marion, 404 U. S. 307, 320 (1971). Neither

respondents nor the courts below question that the Govern

ment may permissibly detain a person suspected of commit

ting a crime prior to a formal adjudication of guilt. See

Gerstein v. Pugh, supra, at 111-114. Nor do they doubt that

the Government has a substantial interest in ensuring that

persons accused of crimes are available for trials and, ulti

mately, for service of their sentences, or that confinement of

such persons pending trial is a legitimate means of furthering

that interest. Tr. of Oral Arg. 27; see Stack v. Boyle, 342

IT. S. 1, 4 (1951).15 Instead, what is at issue when an aspect

of pretrial detention that is not alleged to violate any express

guarantee of the Constitution is challenged, is the detainee’s

right to be free from punishment, see infra, at 13-14, and his

understandable desire to be as comfortable as possible during

his confinement, both of which may conceivably coalesce at

16 In order to imprison a person prior to trial, the Government must

comply with constitutional requirements, Gerstein v. Pugh, 420 U. S., at

114; Stack v. Boyle, 342 U. S. 1, 5 (1951), and any applicable statutory

provisions, e. g., 18 U. S. C. §§ 3146, 3148. Respondents do not allege

that the Government failed to comply with the constitutional or statutory

requisites to pretrial detention.

The only justification for pretrial detention asserted by the Govern

ment is to ensure the detainees’ presence at trial. Brief for Petitioners 43.

Respondents do not question the legitimacy of this goal. Brief for

Respondents 33; Tr. of Oral Arg. 27. We, therefore, have no occasion to

consider whether any other governmental objectives may constitutionally

justify pretrial detention.

BELL v. WOLFISH 13

some point. I t seems clear that the Court of Appeals did not

rely on the detainee’s right to be free from punishment, but

even if it had that right does not warrant adoption of that

court’s compelling necessity test. See infra, at 13-19. And

to the extent the court relied on the detainee’s desire to be free

from discomfort, it suffices to say that this desire simply does

not rise to the level of those fundamental liberty interests

delineated in cases such as Roe v. Wade, 410 IT. S. 113 (1973);

Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U. S. 438 (1972); Stanley v. Illinois,

405 U. S. 645 (1972); Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479

( 1965) ; Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U. S, 390 (1923).

B

In evaluating the constitutionality of conditions or restric

tions of pretrial detention that implicate only the protection

against deprivation of liberty without due process of law,

we think that the proper inquiry is whether those conditions

amount to punishment of the detainee.16 For under the Due

Process Clause, a detainee may not be punished prior to an

adjudication of guilt in accordance with due process of law.17

16 The Court of Appeals properly relied on the Due Process Clause

rather than Eighth Amendment in considering the claims of pretrial

detainees. Due process requires that a pretrial detainee not be punished.

A sentenced inmate, on the other hand, may be punished, although that

punishment may not be “cruel and unusual” under the Eighth Amend

ment. The Court recognized this distinction in Ingraham v. Wright, 430

U. S. 651, 671-672, n. 40 (1977):

“Eighth Amendment scrutiny is appropriate only after the State has

complied with the constitutional guaranties traditionally associated with

criminal prosecutions. See United States v. Lovett, 328 U. S. 303, 317-

318 (1946) . . . . [T]he State does not acquire the power to punish with

which the Eighth Amendment is concerned until after it has secured a

formal adjudication of guilt in accordance with due process of law.

Where the State seeks to impose punishment without such an. adjudication,

the pertinent constitutional guarantee is the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.”

17 M r . J ustice Stevens in dissent claims tha t this holding constitutes

14 BELL v. WOLFISH

See Ingraham v. Wright, 430 U. S. 651, 671-672 n. 40, 674

(1977); Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U. S. 144,165-167,

186 (1963); Wong Wing v. United States, 163 U. S. 228, 237

(1896). A person lawfully committed to pretrial detention

has not been adjudged guilty of any crime. He has had only

a “judicial determination of probable cause as a prerequisite

to [the] extended restraint of [his] liberty following arrest.”

Gerstein v. Pugh, 420 U. S., at 114; see Virginia v, Paul, 148

U. S. 107, 119 (1893). And, if he is detained for a suspected

violation of a federal law, he also has had a bail hearing. See

18 U. S. C. §§ 3146, 3148.18 Under such circumstances, the

a departure from our prior due process oases, specifically Leis v. Flynt,

— - U. S. — • (1978), and PauL v. Davis, 424 U. S. 693 (1976). Post, a.t

at 2-3, and n. 6. But as the citations following this textual statement

indicate, we leave prior decisional law as we find it and simply apply

it to the case at bar. For example, in Wong Wing v. United States, 163

U. S. 228, 237 (1896), the Court held that the subjection of persons to

punishment at hard labor must be preceded by a judicial trial to establish

guilt. And in Ingraham v. Wright, 430 U. S. 651, 674 (1977), we stated

that “at least where school authorities, acting under color of state law,

deliberately decided to punish a child for misconduct by restraining the

child and inflicting appreciable physical pain, we hold that Fourteenth

Amendment liberty interests are implicated.” (Emphasis supplied.)

Thus, there is neither novelty nor inconsistency in our holding that the

Fifth Amendment includes freedom from punishment within the liberty of

which no person may be deprived without due process of law.

We, of course, do not mean by the textual discussion of the rights of

pretrial detainees to cast doubt on any historical exceptions to the general

principle that punishment can only follow a determination of guilt after

trial or plea—exceptions such as the power summarily to punish for con

tempt of court. See, e. g., United States v. Wilson, 421 U. S. 309 (1975);

Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U. S. 194 (1968); United States v. Barnett, 376 U. S.

681 (1964); Cooke v. United States, 267 U. S. 517 (1925); Ex parte Terry,

128 U. S. 289 (1888); Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 42.

18 The Bail Reform Act of 1966 establishes a liberal policy in favor of

pretrial release. 18 U. S. C. §§ 3146, 3148. Section 3146 provides in

pertinent part:

“Any person charged with an offense, other than an offense punishable

by death, shall, at his appearance before a judicial officer, be ordered

BELL v. WOLFISH 15

Government concededly may detain him to ensure his presence

at trial and may subject him to the restrictions and conditions

of the detention facility so long as those conditions and restric

tions do not amount to punishment, or otherwise violate the

Constitution.

Not every disability imposed during pretrial detention

amounts to “punishment” in the constitutional sense, how

ever. Once the Government has exercised its conceded au

thority to detain a person pending trial, it obviously is

entitled to employ devices that are calculated to effectuate

this detention. Traditionally, this has meant confinement in

a facility which, no matter how modern or how antiquated,

results in restricting the movement of a detainee in a manner

in which he would not be restricted if he simply were free

to walk the streets pending trial. Whether it be called a jail,

a prison, or custodial center, the purpose of the facility is to

detain. Loss of freedom of choice and privacy are inherent

incidents of confinement in such a facility. And the fact that

such detention interferes with the detainee’s understandable

desire to live as comfortably as possible and with as little

restraint as possible during confinement does not convert the

conditions or restrictions of detention into “punishment.”

This Court has recognized a distinction between punitive

measures that may not constitutionally be imposed prior to a

determination of guilt and regulatory restraints that may.

See, e. g., Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, supra, at 168;

Fleming v. Nestor, 363 U. S. 603, 613-614 (1960); cf. DeVeau

v. Braisted, 363 U. S. 144, 160 (1960). In Kennedy v.

Mendoza-Martinez, supra, the Court examined the automatic

forfeiture of citizenship provisions of the immigration laws

to determine whether that sanction amounted to punishment

released pending trial on his personal recognizance or upon the execution

of an unsecured appearance bond in an amount specified by the judicial

officer, unless the officer determines, in the exercise of his discretion, that

such a release will not reasonably assure the appearance of the person as

required,”

16 BELL v. WOLFISH

or a mere regulatory restraint. While it is all but impossible

to compress the distinction into a sentence or a paragraph, the

Court there described the tests traditionally applied to deter

mine whether a governmental act is punitive in nature:

“Whether the sanction involves an affirmative disability

or restraint, whether it has historically been regarded as a

punishment, whether it comes into play only on a finding

of scienter, whether its operation will promote the tradi

tional aims of punishment—retribution and deterrence,

whether the behavior to which it applies is already a

crime, whether an alternative purpose to which it may

rationally be connected is assignable for it, and whether

it appears excessive in relation to the alternative purpose

assigned are all relevant to the inquiry, and may often

point in differing directions.” 372 U. S., at 168-169

(footnotes omitted).

Because forfeiture of citizenship traditionally had been con

sidered punishment and the legislative history of the forfeiture

provisions “conclusively” showed that the measure was in

tended to be punitive, the Court held that forfeiture of

citizenship in such circumstances constituted punishment that

could not constitutionally be imposed without due process of

law. Id., at 167-170, 186.

The factors identified in Mendoza-Martinez provide useful

guideposts in determining whether particular restrictions and

conditions accompanying pretrial detention amount to punish

ment in the constitutional sense of that word. A court must

decide whether the disability is imposed for the purpose of

punishment or whether it is but an incident of some other

legitimate governmental purpose. See Flemming v. Nestor,

supra, at 613-617.19 Absent a showing of an expressed intent

19 As Mr. Justice Frankfurter stated in United States v. Lovett, 328

U. S. 303, 324 (1946) (concurring opinion): ‘’The fact that harm is

inflicted by governmental authority does not make it punishment. Figura-

BELL v. WOLFISH 17

to punish on the part of detention facility officials, that

determination generally will turn on “ [w]hether an alternative

purpose to which {the restriction] may rationally be connected

is assignable for it, and whether it appears excessive in relation

to the alternative purpose assigned [to it].” Kennedy v.

Mendoza-Martinez, supra, at 168-169; see Flemming v. Nestor,

supra, at 617. Thus, if a particular condition or restriction of

pretrial detention is reasonably related to a legitimate govern

mental objective, it does not, without more, amount to “pun

ishment.” 20 Conversely, if a restriction or condition is not

reasonably related to a legitimate goal—if it is arbitrary or

purposeless—a court permissibly may infer that the purpose

of the governmental action is punishment that may not con

stitutionally be inflicted upon detainees qua detainees. See

Flemming v. Nestor, supra, at 617.21 Courts must be mindful

that these inquiries spring from constitutional requirements

and that judicial answers to them must reflect that fact rather

tively speaking all discomforting action may be deemed punishment because

it deprives of what otherwise would be enjoyed. But there may be reasons

other than punitive for such deprivation.”

20 This is not to say that the officials of a detention facility can justify

punishment. They cannot. It is simply to say that in the absence of a

showing of intent to punish, a court must look to see if a particular restric

tion or condition, which may on its face appear to be punishment, is

instead but an incident of a legitimate nonpunitive governmental objective.

See Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, supra, at 168; Flemming v. Nestor,

supra, at 617. Retribution and deterrence are not legitimate nonpunitive

governmental objectives. Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, supra, at 168.

Conversely, loading a detainee with chains and shackles and throwing

him in a dungeon may ensure his presence at trial and preserve the

security of the institution. But it would be difficult to conceive of a

situation where conditions so harsh, employed to achieve objectives that

could be accomplished in so many alternative and less harsh methods,

would not support a conclusion that the purpose for which they were

imposed was to punish.

21 “There is, of course, a de minimis level of imposition with which the

Constitution is not concerned.” Ingraham v. Wright, supra, at 674.

18 BELL v. WOLFISH

than a court’s idea of how best to operate a detention facility.

Cf. United States v. Lovasco, 431 U. S. 783, 790 (1977);

United States v. Russell, 411 IT. S. 423, 435 (1973).

One further point requires discussion. The Government

asserts, and respondents concede, that the “essential objective

of pretrial confinement is to insure the detainees’ presence at

trial.” Brief for Petitioners 43; see Brief for Respondents 33.

While this interest undoubtedly justifies the original decision

to confine an individual in some manner, we do not accept

respondent’s argument that the Government’s interest in

ensuring a detainee’s presence at trial is the only objective

that may justify restraints and conditions once the decision is

lawfully made to confine a person. “If the government could

confine or otherwise infringe the liberty of detainees only to

the extent necessary to ensure their presence at trial, house

arrest would in the end be the only constitutionally justified

form of detention.” Campbell v. Magruder, supra, at 529.

The Government also has legitimate interests that stem from

its need to manage the facility in which the individual is

detained. These legitimate operational concerns may require

administrative measures that go beyond those that are, strictly

speaking, necessary to ensure that the detainee shows up at

trial. For example, the Government must be able to take

steps to maintain security and order at the institution and

make certain no weapons or illicit drugs reach detainees.22

Restraints that are reasonably related to the institution’s

interest in maintaining jail security do not, without more, con

stitute unconstitutional punishment, even if they are discom

forting and are restrictions that the detainee would not have

experienced had he been released while awaiting trial. We

need not here attempt to detail the precise extent of the legit

imate governmental interests that may justify conditions or

22 In fact, security measures may directly serve the Government’s inter

est in ensuring the detainee’s presence at trial. See Feeley v. Sampson,

570 F, 2d, at 369.

BELL v. WOLFISH 19

restrictions of pretrial detention. I t is enough simply to

recognize that in addition to ensuring the detainees’ presence at

trial, the effective management of the detention facility once

the individual is confined is a valid objective that may justify

imposition of conditions and restrictions of pretrial detention

and dispel any inference that such restrictions are intended as

punishment.23

C

Judged by this analysis, respondents’ claim that double-

bunking violated their due process rights fails. Neither the

District Court nor the Court of Appeals intimated that it

considered double-bunking to constitute punishment; instead,

they found that it contravened the compelling necessity test,

which today we reject. On this record, we are convinced as a

matter of law that double-bunking as practiced at the MCC

did not amount to punishment and did not, therefore, violate

respondents’ rights under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth

Amendment.24

The rooms at the MCC that house pretrial detainees have

a total floor space of approximately 75 square feet. Each of

them designated for double-bunking, see n. 4, supra, contains

a double bunkbed, certain other items of furniture, a wash

basin and an uncovered toilet. Inmates generally are locked

23 In determining whether restrictions or conditions are reasonably

related to the government’s interest in maintaining security and order

and operating the institution in a manageable fashion, courts must heed

our warning that “[s]uch considerations are peculiarly within the province

■and professional expertise of corrections officials, and, in the absence of

substantial evidence in the record to indicate that the officials have exag

gerated their response to those considerations, courts should ordinarily

defer to their expert judgment in such matters.” Pell v. Procurder, 417

U. S., at 827; see Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, supra;

Meachum v. Fano, supra; Procunier v. Martinez, supra.

24 The District Court found that there were no disputed issues of mate

rial fact with respect to respondents’ challenge to double-bunking. 428 F.

Supp., at 335. We agree with the District Court in this determination.

20 BELL v. WOLFISH

into their rooms from 11 p. m. to 6:30 a, m. and for brief

periods during the afternoon and evening head counts. Dur

ing the rest of the day, they may move about freely between

their rooms and the common areas.

Based on affidavits and a personal visit to the facility, the

District Court concluded that the practice of double-bunking

was unconstitutional. The court relied on two factors for its

conclusion: (1) the fact that the rooms were designed to house

only one inmate, 428 F. Supp., at 336-337; and (2) its judg

ment that confining two persons in one room or cell of this

size constituted a “fundamental denial [J of decency, privacy,

personal security, and, simply, civilized humanity. . . .” Id.,

at 339. The Court of Appeals agreed with the District Court.

In response to petitioners’ arguments that the rooms at the

MCC were larger and more pleasant than the cells involved in

the cases relied on by the District Court, the Court of Appeals

stated:

“ [W]e find the lack of privacy inherent in double-celling

in rooms intended for one individual a far more com

pelling consideration than a comparison of square footage

or the substitution of doors for bars, carpet for concrete,

or windows for walls. The Government has simply failed

to show any substantial justification for double-celling.”

573 F. 2d, at 127.

We disagree with both the District Court and the Court

of Appeals that there is some sort of “one man, one cell”

principle lurking in the Due Process Clause of the Fifth

Amendment. While confining a given number of people in a

given amount of space in such a manner as to cause them to

endure genuine privations and hardship over an extended

period of time might raise serious questions under the Due

Process Clause as to whether those conditions amounted to

punishment, nothing even approaching such hardship is shown

by this record.25

26 Respondents seem to argue that double-bunking was unreasonable

BELL v. WOLFISH 21

Detainees are required to spend only seven or eight hours

each day in their rooms, during most or all of which they

presumably are sleeping, The rooms provide more than ade

quate space for sleeping.26 During the remainder of the time,

the detainees are free to move between their rooms and the

common area. While double-bunking may have taxed some

of the equipment or particular facilities in certain of the com

mon areas, United States ex rel. Wolfish v. United States, 428

F. Supp., at 337, this does not mean that the conditions at

the MCC failed to meet the standards required by the Con

stitution. Our conclusion in this regard is further buttressed

by the detainees’ length of stay at the MCC. See Hutto v.

Finney, 437 U. S. 678, 686-687 (1978). Nearly all of the

detainees are released within 60 days. See n. 3, supra. We

simply do not believe that requiring a detainee to share toilet

facilities and this admittedly rather small sleeping place with

because petitioners were able to comply with the District Court’s order

forbidding double-bunking and still accommodate the increased numbers

of detainees simply by transferring all but a handful of sentenced inmates

who had been assigned to the MCC for the purpose of performing certain

services and committing those tasks to detainees. Brief for Respondents

50. That petitioners were able to comply with the District Court’s order

in this fashion does not mean that petitioner’s chosen method of coping

with the increased inmate population—double-bunking—was unreasonable.

Governmental action does not have to be the only alternative or even the

best alternative for it to be reasonable, to say nothing of constitutional.

See Vance v. Bradley, — U. S. — (1979); Dandridge v. Williams, 397

U. S. 471, 485 (1970).

That petitioners were able to comply with the District Court order also

does not make this case moot, because petitioners still dispute the legality

of the court’s order and they have informed the Court that there is a

reasonable expectation that they may be required to double-bunk again.

Reply Brief of Petitioners 6; Tr. of Oral Arg. 33-35, 56—57; see United

States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U. S. 629, 632-633 (1953).

26 We thus fail to understand the emphasis of the Court of Appeals

and the District Court on the amount of walking space in the double-

bunked rooms. See 573 F. 2d, at 127; 428 F. Supp,, at 337.

22 BELL v, WOLFISH

another person for generally a maximum period of 60 days

violates the Constitution.27

I l l

Respondents also challenged certain MCC restrictions and

practices that were designed to promote security and order

at the facility on the ground that these restrictions violated

the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, and certain

other constitutional guarantees, such as the First and Fourth

Amendments. The Court of Appeals seemed to approach the

challenges to security restrictions in a fashion different from

the other contested conditions and restrictions. I t stated that

“once it has been determined that the mere fact of confine

ment of the detainee justifies the restrictions, the institution

must be permitted to use reasonable means to insure that its

27 Respondents’ reliance on other lower court decisions concerning mini

mum space requirements for different institutions and on correctional

standards issued by various groups is misplaced. Brief for Respondents

41, and nn. 40 and 41; see, e. g., Campbell v. Magruder, supra; Battle v.

Anderson, 564 F. 2d 388 (CA10 1977); Chapman v. Rhodes, 434 F. Supp.

1007 (SD Ohio 1977); Inmates of Suffolk County Jail v. Eisenstadt, 360

F. Supp. 676 (Mass. 1973); American Public Health Association, Stand

ards for Health Services in Correctional Institutions 62 (1976); American

Correctional Association, Manual of Standards for Adult Correctional In

stitutions 4142 (1977); National Sheriff’s Association, A Handbook on Jail

Architecture 63 (1975). The cases cited by respondents concerned facili

ties markedly different from the MCC. They involved traditional jails

and cells in which inmates were locked during most of the day. Given

this factual disparity, they have little or no application to the case at

hand. Thus, we need not and do not decide whether we agree with the

reasoning and conclusions of these cases. And while the recommendations

of these various groups may be instructive in certain cases, they simply

do not establish the constitutional minima; rather, they establish goals

recommended by the organization in question. For this same reason, the

draft recommendations of the Federal Corrections Policy Task Force of

the Department of Justice regarding conditions of confinement for pre

trial detainees are not determinative of the requirements of the Consti

tution. See Dept, of Justice, Federal Corrections Policy Task Force, Draft

Federal Standards for Corrections (June 1978).

BELL v. WOLFISH 23

legitimate interests in security are safeguarded.” 573 F. 2d,

at 124. The court might disagree with the choice of means

to effectuate those interests, but it should not “second-guess

the expert administrators on matters on which they are better

informed . . . . Concern with minutiae of prison adminis

tration can only distract the court from detached consideration

of the one overriding question presented to i t : does the prac

tice or condition violate the Constitution?” Id., at 124-125.

Nonetheless, the court affirmed the District Court’s injunction

against several security restrictions. The Court rejected the

arguments of petitioners that these practices served the MCC’s

interest in security and order and held that the practices were

unjustified interferences with the retained constitutional rights

of both detainees and convicted inmates. Id., at 129-132. In

our view, the Court of Appeals failed to heed its owm admoni

tion not to “second-guess” prison administrators.

Our cases have established several general principles that

inform our evaluation of the constitutionality of the restric

tions at issue. First, we have held that convicted prisoners do

not forfeit all constitutional protections by reason of their

conviction and confinement in prison. See Jones v. North

Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, 433 U. S. 119, 129 (1977);

Meachum v. Fano, 427 U. S. 215, 225 (1976); Wolff v.

McDonnell, 418 U. S. 539, 555-556 (1974); Pell v. Procunier,

417 U. S. 817, 822 (1974). “There is no iron curtain drawn

between the Constitution and the prisons of this country.”

Wolff v. McDonnell, supra, at 555-556. So, for example, our

cases have held that sentenced prisoners enjoy freedom of

speech and religion under the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments, see Pell v. Procunier, supra; Cruz v. Beto, 405 U. S.

319 (1972); Cooper v. Pate, 378 U. S. 546 (1964), that they

are protected against invidious discrimination on the basis of

race under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, see Lee v. Washington, 390 U. S. 333 (1968),

and that they may claim the protection of the Due Process

Clause to prevent additional deprivation of life, liberty or

24 BELL v. WOLFISH

property without due process of law, see Meachum v, Fano,

supra; Wolff v. McDonnell, supra. A fortiori, pretrial de

tainees, who have not been convicted of any crimes, retain at

least those constitutional rights that we have held are enjoyed

by convicted prisoners.

But our cases also have insisted on a second proposition:

simply because prison inmates retain certain constitutional

rights does not mean that these rights are not subject to

restrictions and limitations. “Lawful incarceration brings

about the necessary withdrawal or limitation of many privi

leges and rights, a retraction justified by the considerations

underlying our penal system.” Price v. Johnston, 334 U. S.

266, 285 (1948); see Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor

Union, supra, at 125; Wolff v. McDonnell, supra, at 555 ; Pell

v. Procunier, supra, at 822. The fact of confinement as well

as the legitimate goals and policies of the penal institution

limit these retained constitutional rights. Jones v. North

Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, supra, at 125; Pell v.

Procunier, supra, at 822. There must be a “mutual accom

modation between institutional needs and objectives and the

provisions of the Constitution that are of general application.”

Wolff v. McDonnell, supra, at 556. This principle applies

equally to pretrial detainees and convicted prisoners. A de

tainee simply does not possess the full range of freedoms of

an unincarcerated individual.

Third, maintaining institutional security and preserving

internal order and discipline are essential goals that may

require limitation or retraction of the retained constitutional

rights of both convicted prisoners and pretrial detainees.28

28 Neither the Court of Appeals nor the District Court distinguished

between pretrial detainees and convicted inmates in reviewing the chal

lenged security practices, and we see no reason to do so. There is no

basis for concluding that pretrial detainees pose any lesser security risk

than convicted inmates. Indeed, it may be that in certain circumstances

they present a greater risk to jail security and order. See, e. g., Main

Road v. Aytch, 565 F. 2d 54, 57 (CA3 1977). In the federal system, a

BELL v. WOLFISH 25

“Central to all other corrections goals is the institutional con

sideration of internal security within the corrections facilities

themselves.” Pell v. Procunier, supra, at 823; see Jones v.

North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, supra, at 129;

Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U. S. 396, 412 (1974). Prison

officials must be free to take appropriate action to ensure the

safety of inmates and corrections personnel and to prevent

escape or unauthorized entry. Accordingly, we have held that

even when an institutional restriction infringes a specific

constitutional guarantee, such as the First Amendment, the

practice must be evaluated in the light of the central objective

of prison administration, safeguarding institutional security.

Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, supra, at 129;

Pell v. Procunier, supra, at 822, 826; Procunier v. Martinez,

supra, at 412-414.

Finally, as the Court of Appeals correctly acknowledged,

the problems that arise in the day-to-day operation of a cor

rections facility are not susceptible of easy solutions. Prison

administrators therefore should be accorded wide-ranging

deference in the adoption and execution of policies and prac

tices that in their judgment are needed to preserve internal

order and discipline and to maintain institutional security.

Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, supra, at 128 ;

Procunier v. Martinez, supra, at 404-405; Cruz v. Beto, 405

U. S., at 321; see Meachum v. Fano, 427 U. S., at 228-229.29

detainee is committed to the detention facility only because no other less

drastic means can reasonably assure his presence at trial. See 18 U. S. C.

§ 3146. As a result, those who are detained prior to trial may in many

cases be individuals who are charged with serious crimes or who have

prior records. They also may pose a greater risk of escape than con

victed inmates. See Joint App. (No. 77—2035, CA2) 1393—1398, 1531—1532.

This may be particularly true at facilities like the MCC, where the resident

convicted inmates have been sentenced to only short terms of incarceration

and many of the detainees face the possibility of lengthy imprisonment if

convicted.

29 Respondents argue that this Court’s cases holding that substantial

deference should be accorded prison officials are not applicable to this

26 BELL v. WOLFISH

“Such considerations are peculiarly within the province and

professional expertise of corrections officials, and, in the

absence of substantial evidence in the record to indicate that

the officials have exaggerated their response to these consid

erations, courts should ordinarily defer to their expert judg

ment in such matters.” Pell v. Procunier, supra, at 827.30

We further observe that on occasion, prison administrators

may be “experts” only by Act of Congress or of a state legisla

ture. But judicial deference is accorded not merely because

the administrator ordinarily will, as a matter of fact in a

particular case, have a better grasp of his domain than the

reviewing judge, but also because the operation of our correc-

case because those decisions concerned convicted inmates, not pretrial

detainees. Brief for Respondents 52. We disagree. Those decisions held

that courts should defer to the informed discretion of prison administrators

because the realities of running a corrections institution are complex and

difficult, courts are ill-equipped to deal with these problems and the

management of these facilities is confided to the Executive and Legislative

Branches, not to the Judicial Branch. See Jones v. North Carolina

Prisoners’ Labor Union, 433 U. S., at 126; Pell v. Procunier, 417 U. S., at

827; Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U. S., at 404-405. While those cases each

concerned restrictions governing convicted inmates, the principle of

deference enunciated in them is not dependent on that happenstance.

80 What the Court said in Procunier v. Martinez, supra, bears repeating

here:

“Prison administrators are responsible for maintaining internal order and

discipline, for securing their institutions against unauthorized access or

escape, and for rehabilitating, to the extent that human nature and in

adequate resources allow, the inmates placed in their custody. The Her

culean obstacles to effective discharge to these duties are too apparent to

warrant explication. Suffice it to say that the problems of prisons in

America are complex and intractable, and, more to the point, they are not

readily susceptible of resolution by decree. Most require expertise, com

prehensive planning and the commitment of resources, all of which are

peculiarly within the province of the legislative and executive branches

of government. For all of those reasons, courts are ill equipped to deal

with the increasingly urgent problems of prison administration and reform.

Judicial recognition of that fact reflects no more than a healthy sense of

realism.” 416 U. S., at 404-405,

BELL v. WOLFISH 27

tional facilities is peculiarly the province of the Legislative and

Executive Branches of our Government, not the Judicial.

Procunier v. Martinez, supra, at 405; cf. Meachum v, Fano,

sUpra,, at 229. With these teachings of our cases in mind, we

turn to an examination of the MCC security practices that are

alleged to violate the Constitution.

A

At the time of the lower courts’ decisions, the Bureau of

Prisons’ “publisher-only” rule, which applies to all Bureau

facilities, permitted inmates to receive books and magazines

from outside the institution only if the materials were mailed

directly from the publisher or a book club. 573 F. 2d, at

129-130. The warden of the MCC stated in an affidavit that

“serious” security and administrative problems were caused

when bound items were received by inmates from unidentified

sources outside the facility. App. 24. He noted that in order

to make a “proper and thorough” inspection of such items,

prison officials would have to remove the covers of hardback

books and to leaf through every page of all books and maga

zines to ensure that drugs, money, weapons or other contra

band were not secreted in the material. “This search process

would take a substantial and inordinate amount of available

staff time.” Ibid. However, “there is relatively little risk

that material received directly from the publisher or book

club would contain contraband, and therefore, the security

problems are significantly reduced without a drastic drain on

staff resources.” Ibid.

The Court of Appeals rejected these security and adminis

trative justifications and affirmed the District Court’s order

enjoining enforcement of the “publisher-only” rule at the

MCC. The Court of Appeals held that the rule “severely

and impermissibly restricts the reading material available to

inmates” and therefore violates their First Amendment and

due process rights. 573 F. 2d, at 130.

28 BELL v. WOLFISH

It is desirable at this point to place in focus the precise

question that now is before this Court. Subsequent to the

decision of the Court of Appeals, the Bureau of Prisons

amended its “publisher-only” rule to permit the receipt of

books and magazines from bookstores as well as publishers

and book clubs. 43 Fed. Reg. 30576 (July 17, 1978). In

addition, petitioners have informed the Court that the Bureau

proposes to amend the rule further to allow receipt of paper

back books, magazines and other soft-covered materials from

any source. Brief for Petitioners 86 n. 49, 69, and n. 51. The

Bureau regards hardback books as the “more dangerous source

of risk to institutional security,” however, and intends to

retain the prohibition against receipt of hardback books unless

they are mailed directly from publishers, book clubs or book

stores, Id., at 69 n. 51. Accordingly, petitioners request this

Court to review the District Court’s injunction only to the

extent it enjoins petitioners from prohibiting receipt of hard

cover books that are not mailed directly from publishers, book

clubs or bookstores. Id., at 69; Tr. of Oral Arg. 59-60.31

31 Because of the changes in the “publisher-only” rule, some of which

apparently occurred after we granted certiorari, respondents, citing Sanks

v. Georgia, 401 U. S. 144 (1971), urge the Court to dismiss the writ of

certiorari as improvidently granted with respect to the validity of the rule,

as modified. Brief for Respondents 68. Sanks, however, is quite different

from the instant case. In Sanks the events that transpired after probable

jurisdiction was noted “had so drastically undermined the premises on

which we originally set [the] case for plenary consideration as to lead us to

conclude that, with due regard for the proper functioning of this Court,

we should not . . . adjudicate it.” Id., at 145. The focus of that case

had been “completely blurred, if not altogether obliterated,” and a judg

ment on the issues involved had become “potentially immaterial.” Id., at

152. This is not true here. Unlike the situation in Sanks, the Govern

ment has not substituted an entirely different regulatory scheme and

wholly abandoned the restrictions that were invalidated below. There is

still a dispute, which is not “blurred” or “obliterated,” on which a judg

ment- will not be “immaterial.” Petitioners merely have chosen to limit

their disagreement with the lower courts’ rulings. Also, the question that is

BELL v. WOLFISH 29

We conclude that a prohibition against receipt of hardback

books unless mailed directly from publishers, book clubs or

bookstores does not violate the First Amendment rights of

MCC inmates, That limited restriction is a rational response

by prison officials to an obvious security problem. I t hardly

needs to be emphasized that hardback books are especially

serviceable for smuggling contraband into an institution ;

money, drugs and weapons easily may be secreted in the

bindings. E. g., Woods v. Daggett, 541 F. 2d 237 (CA10

1976).32 They also are difficult to search effectively. There

is simply no evidence in the record to indicate that MCC

officials have exaggerated their response to this security prob

lem and to the administrative difficulties posed by the necessity

of carefully inspecting each book mailed from unidentified

sources. Therefore, the considered judgment of these experts

must control in the absence of prohibitions far more sweeping