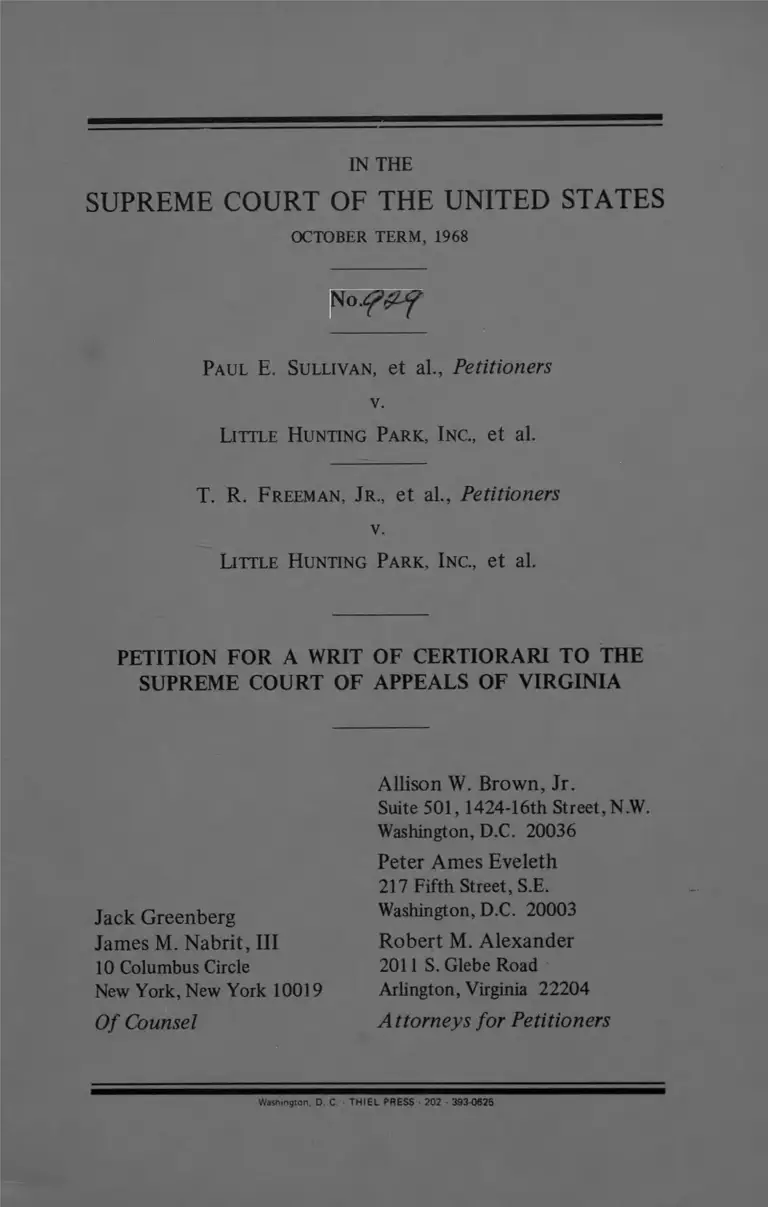

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1969. 64085054-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a62a121d-7be8-40f8-b53a-07e65256cdf1/sullivan-v-little-hunting-park-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1968

P a u l E. S u l l iv a n , e t a l., Petitioners

L ittle H u n t in g Pa r k , I n c ., e t al.

T. R. F r e e m a n , Jr., et al., Petitioners

Little H u n t in g P a r k , I n c ., e t al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

Allison W. Brown, Jr.

Suite 501, 1424-16th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Peter Ames Eveleth

217 Fifth Street, S.E.

v.

v.

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Of Counsel

Washington, D.C. 20003

R obert M. A lexander

2011 S. Glebe Road

Arlington, Virginia 22204

A ttorneys for Petitioners

Washington. D. C. • T H IE L PR ESS • 202 393-0625

INDEX

PRIOR OPINIONS ............................................................................ 2

JURISDICTION................................................................................. 2

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ............................................................. 2

STATUTORY AND CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS .......... 3

STATEMENT...................................................................................... 4

A. Introduction ............................................................................ 4

B. Little Hunting Park, Inc. - Its purpose and manner of

operation ................................................................................. 6

C. The corporation’s directors refuse to approve the assign

ment of Paul E. Sullivan’s share because the assignee,

Dr. T. R. Freeman, Jr., and his family are Negroes .......... 8

D. The corporation’s directors expel Paul E. Sullivan be

cause of his criticism of their refusal to approve the

assignment of his share to Dr. T. R. Freeman, Jr. on

the basis of r a c e ...................................................................... 9

E. Relief so u g h t............................................................................ 11

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT ..................................... 13

CONCLUSION ...........................................' .................................... 27

CITATIONS

CASES:

Amalgamated Food Employees Union Local 590 v. Logan

Valley Plaza, Inc., 391 U.S. 308 ......................................... 17, 21

Bacigalupo v. Fleming, 199 Va. 827, 102 S.E.2d 321 .......... 25, 26

Baird v. Tyler, 185 Va. 601, 39 S.E.2d 642 15

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ................................. 16, 17, 20, 23

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 ............................................................ 20, 21

Bernstein v. Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Ass’n, 139 Cal.

App. 2d 241,293 P.2d 862 ....................................................... 16

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 .................................................. 20

Callender v. Florida, 383 U.S. 270 ................................................... 27

(i)

Callender v. Florida, 380 U.S. 5 1 9 ................................................... 27

Clifton v. Puente, 218 S.W.2d 272 (Tex. Civ. A p p .).................... 21

Cook v. Virginia Holsum Bakeries, Inc., 207 Va. 815, 153

S.E.2d 209 ...................................................................................... 26

Crossen v. Duffy, 90 Ohio App. 252, 103 N.E.2d 769 ............... 21

Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130 ......................... 12, 23

Daniel v. Paul, No. 488, certiorari granted, Dec. 9, 1968 .......... 14

Edwards v. Habib, 397 F.2d 687 (C.A.D.C.) .............................. 16

Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296 ......................................... 17, 18, 19

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 ............................................................. 28

Gallagher v. American Legion, 154 Misc. 281, 277 N.Y.S. 81,

aff’d, 242 App. Div. 604, 271 N.Y.S. 1012 ............................ 22

Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1 ........................................................ 28

Grimes v. Crouch, 175 Va. 126, 7 S.E.2d 1 1 5 ......................... 26, 27

Harris v. Sunset Island Property Owners, Inc., 116 So.2d

622 (Fla.) ...................................................................................... 15

Hurwitz v. Directors Guild of America, 364 F.2d 67 (C.A.

2), certiorari denied, 385 U.S. 971 ......................................... 22

Hyde v. Woods, 94 U.S. 523 ............................................................. 15

Hyson v. Dodge, 198 Va. 792, 96 S.E.2d 792 .............................. 25

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 .......... 5, 12, 13, 14, 15

Kornegay v. City of Richmond, 185 Va. 1013, 41 S.E.2d

45 ........................................................................................... 25, 26

Kreshik v. St. Nicholas Cathedral, 363 U.S. 190 ......................... 28

Lauderbaugh v. Williams, 409 Pa. 351, 186 A.2d 39 ............... 15

Madden v. Atkins, 4 N.Y.2d 283, 151 N.E.2d 7 3 ......................... 22

Malibou Lake Mountain Club v. Robertson, 219 Cal. App.

2d 181, 33 Cal. Rptr. 7 4 ............................................................. 16

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 ............................................. 17, 21

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 1 Wheat. 304 ................................... 13, 28

McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316 ........................................ 28

Mitchell v. International Ass’n of Machinists, 196 Cal. App.

2d 796, 16 Cal. Rptr. 813

(ii)

21, 22

Mountain Springs Ass’n v. Wilson, 81 N J. Super. 564, 196

A.2d 270 ...................................................................................... 15

Mulkey v. Reitman, 64 Cal. 2d 529, 413 P.2d 825, affd,

387 U.S. 369 ................................................................................. 19

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288 5

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 360 U.S. 240 13

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 5

Naim v. Naim, 350 U.S. 985 ................................... 27

National Labor Relations Board v. Industrial Union of Marine

and Shipbuilding Workers, 391 U.S. 4 1 8 ................................... 16

Nesmith v. Young Men’s Christian Ass’n of Raleigh, N.C.,

397 F.2d 96 (C.A. 4) .................................................................. 18

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 ......................... 23

Page v. Edmunds, 187 U.S. 596 .................................................. 15

Parrot v. City of Tallahassee, 381 U.S. 1 2 9 ................................... 5

Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563 .................... 21, 23

Public Utilities Comm’n v. Pollack, 343 U.S. 451 .................... 17

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 ............................................. 20, 23

Rice v. Sioux City Memorial Cemetery, 349'U.S. 70 ............... 21

Rockefeller Center Luncheon Club, Inc. v. Johnson, 131 F.

Supp. 703 (S.D. N .Y .).................................................................. 18

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 ................................................... 15, 20

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 376 U.S. 339 .................... 27

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F.2d 959

(C.A. 4), certiorari denied, 376 U.S. 938 .............................. 17

Snead v. Commonwealth, 200 Va. 850, 108 S.E.2d 399 .......... 27

Spayd v. Ringing Rock Lodge No. 665, 270 Pa. 67, 113 Atl.

70 16

Spencer v. Flint Memorial Park Ass’n, 4 Mich. App. 157, 144

N.W.2d 622 21

Stanley v. Schwalby, 162 U.S. 255 28

State ex rel. Waring v. Georgia Medical Society, 30 Ga. 608 . . . 16

Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 U.S. 313 ......................................... 5

( iii)

(iv)

Stokely v. Owens, 189 Va. 248, 52 S.E.2d 164 ......................... 26

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 392 U.S. 657 .................. 2, 5

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, In c .,___Va. ____, 163 S.E.

2d 588 ........................................................................................... 2

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 12 Race Rel. L. Rep.

1008 ................................................................................................ 2

Taylor v. Wood, 201 Va. 615, 112 S.E.2d 907 .................... 26, 27

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 ........................................................ 17

Thompson v. Grand International Brotherhood of Locomo

tive Engineers, 41 Tex. Civ. App. 176, 91 S.W. 834 ............... 16

Town of Falls Church v. Myers, 187 Va. 110, 46 S.E.2d 31 . . . 26

Tuckerton Beach Club v. Bender, 91 N.J. Super. 167, 219

A.2d 529 ........................................................................................ 15

Tyler v. Magwire, 17 Wall. 253 .................................................. 13, 28

United States v. Richberg, 398 F.2d 523 (C.A. 5) .................... 18

Ward v. Board of County Comm’rs, 253 U.S. 1 7 ......................... 27

Williams v. Bruffy, 12 Otto 248 ................................................... 28

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 .................................................... 27

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS:

Article VI of the Constitution ................................................... 3, 13

First Amendment to the Constitution.......................3, 11, 13, 21, 22

Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution .................... 3, 11, 14

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution..................3, 11, 12, 13

Civil Rights Act of 1866 (14 Stat. 27):

42 U.S.C. § 1981................................... 2, 3, 11, 14, 15, 16, 17

42 U.S.C. § 1982........................................ 2 , 3 , 1 1 , 1 4 , 1 5 , 1 7

28 U.S.C. § 1257(3) ....................................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. § 1651(a)............................................................................ 28

28 U.S.C. § 2106 ............................................................................ 28

Code of Virginia, 1950 (1949 ed.), § 13-220................................... 6

Rules of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, Rule 5:1,

§ 3(f), 2 Code of Virginia, 1950 (1957 Replace. Vol.) 602. . . 4, 5

25, 26

MISCELLANEOUS:

Practical Builder, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Lebruary 1 9 6 4 )....................... 19

Urban Land Institute, Open Space Communities in the Mar

ket Place (Tech. Bulletin 57, 1966)............................................. 18

Washington Post (June 12, 1967) ................................................... 19

(v)

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1968

No.

P a u l E . S u l l iv a n , e t a l., Petitioners

v.

L ittle H u n t in g Pa r k , In c ., e t al.

T. R . F r e e m a n , J r ., e t a l., Petitioners

v.

L ittle H u n t in g P a r k , In c ., e t al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the decision of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

entered October 14, 1968, in these two related cases.^

^Petitioners in the Sullivan case, in addition to Paul E. Sullivan, are

Flora L. Sullivan, his wife, and their seven minor children, William F.

Sullivan, Graciela P. Sullivan, Ana I. Sullivan, Maire Sullivan, M. Dolo

res Sullivan, M. Monica Sullivan, and Brigid Sullivan, who sued by and

through Paul E. Sullivan, their father and next friend. In the Freeman

case the petitioners, in addition to T. R. Freeman, Jr., are Laura

Freeman, his wife, and their two minor children, Dale C. Freeman

and Dwayne L. Freeman, who sued by and through T. R. Freeman,

Jr., their father and next friend. Respondents in both cases, in addi

tion to Little Hunting Park, Inc., are Mrs. Virginia Moore, Ronald L.

Arnette, S. Leroy Lennon, Raymond R. Riesgo, Mrs. Marjorie Madsen,

William J. Donohoe, Oskar W. Egger, and Milton W. Johnson, individ

uals who were directors of said corporation at times material herein.

2

PRIOR OPINIONS

This Court’s earlier per curiam opinion remanding these

cases to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia is reported

at 392 U.S. 657, and is printed in Appendix B hereto,

infra, p. 32. The opinion of the Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia subsequent to the order of remand is reported at

163 S.E.2d 588, and is printed in Appendix B hereto, infra,

pp. 33-35. The memorandum orders of the Supreme Court

of Appeals of Virginia rejecting the appeals from the trial

court are not reported and are printed in Appendix B hereto,

infra, pp. 36-37. The decision of the trial court in the Sul

livan case was contained in a letter to the parties dated April

7, 1967, which is reported at 12 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1008, and

the decree was entered April 12, 1967; they are printed in

Appendix B hereto, infra, pp. 38-41. The trial court’s deci

sion in the Freeman case was contained in a letter dated

April 21, 1967, which is not reported, and the decree was

entered May 8, 1967; they are printed in Appendix B

hereto, infra, pp. 42-44.

JURISDICTION

The decision of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

was rendered on October 14, 1968. The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1257(3).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

properly relied upon a non-federal procedural ground as the

sole basis for refusing to accept the remand of this Court

after this Court had held that such ground was inadequate

to bar consideration of the federal questions presented by

this case.

2. Whether the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981, 1982) which guarantees Negroes the same rights as

are enjoyed by white persons to make and enforce contracts

3

and to lease and hold property is violated when a Negro,

because of his race, is not permitted by the board of direc

tors of a community recreation association to use a mem

bership share which has been assigned to him by his landlord

as part of the leasehold estate.

3. Whether a landlord who is expelled from a community

recreation association because he voices disagreement with

with the directors’ racially motivated refusal to approve his

assignment of a share in the association to his Negro tenant

may obtain relief from the association’s retaliatory action

under the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982).

4. Whether the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States is violated by a community recre

ation association when it excludes from its facilities on the

basis of his race, a person who is otherwise eligible to use

them, and by a state court in sanctioning the exclusion.

5. Whether the free speech protections of the First and

Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States are violated by a community recreation association

when it expels a shareholder for dissenting from its discrim

inatory racial policy, and by a state court in sanctioning the

expulsion.

STATUTORY AND CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

The statutory provisions involved are 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981

and 1982. The provisions of the Constitution of the United

States involved are Article VI, the First Amendment, the

Thirteenth Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment,

Section 1. The foregoing provisions are set forth in Appen

dix A, infra, pp. 29-30.

4

STATEMENT

A. Introduction

Briefly, respondent Little Hunting Park, Inc. is a Virginia

non-stock corporation organized for the purpose of operat

ing a community park and swimming pool for the benefit

of residents of certain housing subdivisions in Fairfax

County, Virginia. A person who owns a membership share

entitling him to use the association’s facilities is permitted

under the corporate by-laws, in the event he rents his house

to another, to assign the share to his tenant, subject to

approval by the board of directors. In the instant case the

directors refused to approve such an assignment from Paul

E. Sullivan to Dr. T. R. Freeman, Jr., solely on the ground

that Freeman and the members of his family are Negroes.

When Sullivan protested the directors’ discriminatory racial

policy and sought to reverse their refusal to approve the

assignment, they expelled him.

Petitioners sued separately in the state court challenging

on federal, as well as state, grounds the racial restriction

imposed by the directors on the assignment of the share in

the association, and asserting the unlawfulness of Sullivan s

expulsion; injunctive relief and monetary damages were

sought. Following trials, the lower court dismissed the

complaints holding that the corporation is a “private social

club” with authority to determine the qualifications of

those using its facilities, including the right to deny such

use on the basis of race. The court also held that the cor

poration’s expulsion of Sullivan was permitted by its

by-laws and was justified by the evidence. Petitions for

appeal were thereafter submitted to the Supreme Court of

Appeals of Virginia, which were rejected by that court for

the stated reasons that petitioners had failed to comply with

a procedural rule of that court.2

2The Virginia court, citing its Rule 5:1, Sec. 3(f), (Appendix A, infra,

pp. 30-31), stated that the appeals were “not perfected in the man

ner provided by law in that opposing counsel was not given reasonable

5

In their petition for a writ of certiorari filed in this Court

on March 1, 1968, petitioners contended that the Virginia

court’s application of its procedural rule to bar the appeals

was arbitrary and unreasonable—warranted neither by the

facts nor the court’s prior construction of its procedural

rule. Accordingly, petitioners asserted that in view of the

claimed violations of their federally protected rights, the

procedural ground on which state court based its decision

should be examined to determine its adequacy to bar review

by this Court.-3 * 5

This Court in a per curiam opinion rendered June 17,

1968, stated (392 U.S. 657):

The petition for a writ of certiorari is granted and

the judgment is vacated. The case is remanded to

the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia for fur

ther consideration in light of Jones v. Alfred H.

Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409.

The order of remand was thereafter received by the

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, and on October 14,

written notice of the time and place of tendering the transcript and a

reasonable opportunity to examine the original or a true copy of it.”

The rule referred to provides that as part of the procedure for certify

ing a record for appeal the reporter’s transcript must be tendered to

the trial judge within 60 days and signed at the end by him within 70

days after final judgment. The rule also states: “Counsel tendering

the transcript . . . shall give opposing counsel reasonable written notice

of the time and place of tendering it and a reasonable opportunity to

examine the original or a true copy of it.” 2 Code of Virginia, 1950

(1957 Replace. Vol.) 602.

3Citing Parrot v. City of Tallahassee, 381 U.S. 129; N.A.A.C.P. v.

Alabama, 377 U.S. 288, 297; Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 U.S. 313,

318-320; N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449, 454-458. In their

petition for certiorari, petitioners related in detail the steps they had

gone through to comply with the state court’s procedural rule, and

showed how they had in fact complied with it in both substance and

form, on the basis of the state court’s prior construction of its rule.

(For the convenience of the Court, the relevant facts and authorities

relied on by petitioners in support of their contention are repeated

infra, pp. 23-27.) The opposition to the petition for certiorari filed by

respondents was based exclusively on the procedural issue.

6

1968, that court issued an opinion declaring its refusal to

accept the remand. The court cited as its reason the same

ground originally given for refusing to hear the cases, i.e.,

petitioners, asserted failure to perfect their appeals from the

trial court because of noncompliance with the procedural

rule.

In view of the unavailability of the state court as a

forum for consideration of the asserted violations to the

petitioners’ federally protected rights, petitioners now appeal

to this Court for a second time, and respectfully urge it to

consider the merits of the significant questions presented

herein.

B. Little Hunting Park, Inc.—Its purpose

and manner of operation

Little Hunting Park, Inc. was incorporated in 1954 under

the Virginia Non-Stock Corporation Law'* for the purpose,

as set forth in its certificate of incorporation, of organizing

and maintaining “a community park and playground facili

ties” for “ community recreation purposes” (T. 184-185).4 5

Pursuant to this object, the corporation owns land on which

it has built and operates a swimming pool, tennis courts

and other recreation facilities for the benefit of residents of

specified subdivisions and certain adjacent neighborhoods in

Fairfax County, Virginia (T. 186, 228). The corporation’s

by-laws provide that shares may be purchased by adult per

sons who “reside in, or who own, or who have owned

housing units” in one of the specified subdivisions (T. 186).

A share entitles all persons in the immediate family of the

shareholder to use the corporation’s recreation facilities (T.

186-187).

The by-laws limit the number of shares in the corpora

tion to 600 (T. 186). There is no limitation, however, on

4§ 13-220, Code of Virginia, 1950 (1949 ed.).

^“T.” refers to the transcript in the Sullivan case. “F.T.” refers to

the Freeman transcript.

7

the number of shares that an individual may own, and it is

not unusual for a person owning more than one house in

the neighborhood served by Little Hunting Park pool to

own a separate share for the use of the family occupying

each house (T. 9, 189-190). Shares may also be purchased

by institutions and corporations owning property in the

area where the swimming pool is located. Thus, a share is

owned by a church located in the neighborhood, and shares

have been owned by two real estate companies that built

and marketed the houses in Bucknell Manor and Beacon

Manor, subdivisions served by Little Hunting Park. These

two corporations have, at various times, owned at least 25

shares which they have retained for periods ranging from 5

to 7 years (F.T. 42-44).

The right to use Little Hunting Park’s facilities may be

acquired by purchase or by temporary assignment of a cor

porate share. The share may be purchased directly from

the corporation, from any shareholder, or, upon buying a

house in the community, from the vendor as part of the

consideration for the purchase price of the house (T. 9,

187-189). A person residing within one of the subdivisions

served by Little Hunting Park may obtain temporary assign

ment of a share; however, an assignment may only be made

from landlord to tenant. (T. 187, 200).6

The corporation’s by-laws have always provided that the

issuance and assignment of shares are subject to the approval

of the board of directors (T. 15, 192, 251-252). There

were 1,183 shares issued and 322 shares assigned during the

period from 1955 through 1966, the first 12 years of the

corporation’s existence (T. 192-193, 196-197). However,

with the exception of the assignment described below to

Dr. T. R. Freeman, Jr., there is no record of any assignment

ever being denied approval by the directors (T. 199). One

^Regardless of whether the swimming pool and park facilities are

used by the shareholder or assignee, the owner of a share is obligated

to pay an annual assessment in order to keep his share valid. (T. 9-10,

199-200).

8

applicant for the purchase of a share was disapproved during

that period, but there is no evidence that this was other

than because of the individual’s failure to satisfy the geo

graphic residence requirement of the by-laws (T. 198-199).

C. The corporation’s directors refuse to approve the

assignment of Paul E. Sullivan’s share because the

assignee, Dr. T. R. Freeman, Jr., and his family,

are Negroes.

From December 1950 to March 1962, Paul E. Sullivan

and his family lived in a house which Sullivan owned and

continues to own on Quander Road in the Bucknell Manor

subdivision (T. 7). In May 1955, shortly after Little Hunt

ing Park, Inc. was organized, Sullivan purchased a share,

No. 290, for $150 (T. 7-8). In March 1962, Sullivan

and his family moved a short distance to another house

that Sullivan purchased located on Coventry Road in the

White Oaks subdivision where, as part of the purchase price

for the property, Sullivan acquired a second share from the

seller of the house. Share No. 925 was thereafter issued to

Sullivan by the corporation (T. 8-9, 66-67). After moving

to Coventry Road, Sullivan continued paying the annual

assessments on shares Nos. 290 and 925, and leased his

house on Quander Road to various tenants. In considera

tion of the rent, he assigned share No. 290 as part of the

leasehold interest (T. 9-10, 12, 14-16). Sullivan testified

that the lease arrangement was a “package deal . . . the

house, the yard, and the pool share” (T. 10).

On February 1, 1965, Sullivan leased the Quander Road

premises for a term of one year to Dr. T. R. Freeman, Jr.

at a rent of $1,548, payable in monthly installments of

$129 (T. 10-11). The deed of lease described the property

demised as “ the dwelling located at 6810 Quander Road,

Bucknell Manor, Alexandria, Virginia 22306, and Little

Hunting Park, Inc. pool share No. 290” (T. 11). The lease

was extended in identical terms as of February 1, 1966, and

February 1, 1967 (T. 10-11). Dr. Freeman met all of the

9

eligibility requirements for an assignee of a share in the cor

poration, since he is an adult, and the house that he leased

from Sullivan is in Bucknell Manor subdivision (T. 204-

205). Freeman has no disqualifications; he is an agricul

tural economist with a Ph.D. degree from the University

of Wisconsin, and at the time of the events herein was

employed by the Foreign Agriculture Division of the United

States Department of Agriculture (T. 176-177). He also

holds the rank of Captain in the District of Columbia

National Guard (T. 177). Dr. Freeman and his wife and

children are Negroes (T. 178).

In April 1965, Paul E. Sullivan paid the annual assessment

of $37 on share No. 290 and, pursuant to his obligation

contained in the lease on the Quander Road property, com

pleted the form prescribed by the corporation affirming

that Dr. Freeman was his tenant and therefore eligible to

receive the assignment of that share (T. 11-12). Addition

ally, Dr. Freeman supplied certain information and signed

the form, thereby doing everything required by the corpo

ration to qualify as an assignee of the share (T. 12). How

ever, the board of directors of the corporation, meeting on

May 18, 1965, refused to approve the assignment of share

No. 290 to Dr. Freeman, because he and the members of

his family are Negroes (T. 13, 17-18, 164, 204-205, 239-

240, 281). On May 25, 1965, Sullivan received a letter

from S. L. Lennon, the corporation’s membership chairman,

notifying him that his assignment of share No. 290 to Dr.

Freeman had been denied approval by the board of direc

tors; no reason was given (T. 13).

D. The corporation’s directors expel Paul E. Sullivan

because of his criticism of their refusal to approve

the assignment of his share to Dr. T. R. Freeman,

Jr. on the basis of race.

Sullivan, upon learning of the directors’ disapproval of his

assignment to Dr. Freeman, sought further information con

cerning their action (T. 13-14, 16). In response to his

10

inquiry, a delegation from the board-membership chairman

S. L. Lennon, John R. Hanley, a former president and

director of the corporation, and Oskar W. Egger, a director-

visited Mr. and Mrs. Sullivan at their home on May 28,

1965, and admitted that Dr. Freeman had been rejected

solely because of his race (T. 16-18, 163-164, 250, 259,

278, 281). To Sullivan, this action was shocking, and as a

matter of his religious teaching and conviction, immoral; he

so informed the delegation. Furthermore, as a resident of

the neighborhood for many years and as a member of Little

Hunting Park, Inc. since its inception, he could not believe

their assertion that the board’s action reflected the unani

mous view of the members of the corporation (T. 19, 22,

164) . Nor could Sullivan in good conscience accept the

board’s offer to purchase share No. 290 which he had con

tracted to assign to Dr. Freeman (T. 18-19).

Following this meeting, Sullivan and Dr. Freeman, who

was also his fellow parishioner, sought the advice of their

priest, Father Walsh, who suggested that the board might

reconsider its action if the directors had an opportunity to

meet with Dr. Freeman and consider his case on its merits

(T. 26). The suggestion that such a meeting be held was

rebuffed, however, by Mrs. Moore, the corporation’s presi

dent, when Sullivan spoke to her on June 9 (T. 28-29,

165) . At about the same time, Sullivan spoke with several

other shareholders, who, upon learning of the board's

action, wrote letters to President Moore in which they

expressed their strong disagreement with the board’s action

in disapproving Dr. Freeman (T. 217-223). After receipt

of these letters, the board met on June 11, and decided

that there appeared to be “due cause” for Sullivan’s expul

sion from the corporation because of his “non-acceptance

of the Board’s decision” on the assignment of his share

“along with the continued harassment of the board members,

etc.” (T. 29-31, 204, 220).7

n

The sole ground for expulsion provided under the corporate

by-laws is for conduct “inimicable [sic] to the corporation’s members.”

Article III, Section 6(b). The board purported to act under this sec

tion in expelling Sullivan (T. 29-31, 206-207).

11

Sullivan was told of the board’s action in a letter from

President Moore dated July 7, 1965, which also informed

him that he would be given a “hearing” by the directors on

July 20, 1965 (T. 29-31, 206). Because the directors refused

to postpone the hearing in order that Sullivan’s attorney

could appear with hirp, and because they refused to provide

Sullivan with a statement of the conduct alleged to consti

tute the basis for his expulsion, Sullivan was compelled to

commence a civil action in the Circuit Court of Fairfax

County (T. 52-53). Settlement of the action was reached

upon the corporation’s agreeing to postpone the hearing to

August 17, 1965, and to furnish a detailed statement of the

charges against him (T. 53). A statement specifying the

alleged grounds for Sullivan’s expulsion was thereafter fur

nished to him (T. 20-21).

At the “hearing” held by the directors on August 17, no

evidence was introduced in support of any of the allegations

against Sullivan, and he was not permitted to learn the

identity of the persons making charges against him, nor to

question them. He was also denied permission to have a

reporter present to transcribe the proceeding. He had only

the opportunity to present evidence concerning the charges

as he understood them, and to state his views (T. 45-46,

53-55, 62-63, 129-130, 131, 286-287, 289). On August 24,

1965, the board met, and unanimously voted to expel Sulli

van (T. 228). By letter of August 27, 1965, Sullivan was

notified by President Moore of his expulsion, and he was

tendered the then current “sale price” of his two shares,

plus prorated annual assessments on the two shares, the

total amounting to $399.34 (T. 55, 173-174).

E. Relief sought

Petitioners seek injunctive relief and monetary damages

under the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (14 Stat. 27, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981 and 1982), as well as under the First, Thirteenth

and Fourteenth Amendments. However, since the petition

ers in the Freeman case no longer reside in the area served

12

by Little Hunting Park, Inc., their claim is now limited

solely to compensatory and punitive damages, pursuant to

the allegations of their complaint, as the result of having

been denied access for 2 years to the community recreation

facilities operated by the association.5 Petitioners in the

Sullivan case seek an order compelling full reinstatement of

Paul E. Sullivan in Little Hunting Park, Inc. and reinstate

ment of shares Nos. 290 and 925. They also seek compen

satory and punitive damages from respondents for Paul E.

Sullivan’s wrongful expulsion from the association and the

denial to them of the use of its facilities.

The federal statutory questions involved here were the

basis for the Court’s remand of this case to the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia for further consideration in

light of Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. Petitioners have also

relied throughout the proceeding on the Fourteenth Amend

ment, asserting that Little Hunting Park, Inc., by its opera

tion of a community park and recreation facility, exercises

a public function and hence is prohibited by the Equal

Protection clause from denying persons the use of its facili

ties on the basis of race (Freeman memorandum to trial

court in opposition to demurrer, pp. 22-23). Petitioners

have further contended that their rights under the Four

teenth Amendment are violated by the state court’s giving

validity to the racial restriction imposed by respondents on

the Little Hunting Park facilities (Sullivan and Freeman

complaints). Finally, petitioner Paul E. Sullivan contended

at the trial that his expulsion from the association because

of his dissent from its racial policy violated his constitutional

right of free speech (T. 224-245). In his petition for appeal,

Sullivan further contended on the basis of Curtis Publishing

Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130, which had been decided in the

interim between the trial and the filing of the appeal, that

5In June 1967, Dr. Freeman and the members of his family left

the United States, and they currently reside in Pakistan where Dr.

Freeman is Assistant Agricultural Attache in the United States

Embassy.

13

the directors of Little Hunting Park, Inc. were “public

figures” in the community within the meaning of that case.

Hence, it was asserted that the court could not under the

First and Fourteenth Amendments apply state law to “sanc

tion or recognize as valid the directors’ action in expelling

Sullivan from the association merely because he exercised

his right to speak out critically concerning their discrimina

tory racial policy” (Sullivan petition for appeal, p. 34).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

1. The Court, by granting certiorari in this proceeding in

the first instance, impliedly held that the non-federal ground

on which the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia rejected

the appeals in these cases was inadequate to bar considera

tion of the federal questions involved. Upon remand, how

ever, the Virginia court adhered to its prior holding, again

asserting that because the procedural rule had not been

complied with, the cases were not properly before it. The

court, therefore, refused to consider the issues on the merits

in light of Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., as required by this

Court’s mandate.

The refusal by the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

to comply with this Court’s order of remand is itself com

pelling reason for the Court to grant certiorari in this case.

By its action, the state court has disregarded its duty under

the Supremacy Clause, and for this Court to allow this

extraordinary conduct to pass without notice can only be

detrimental to our system of government. Martin v. Hunter’s

Lessee, 1 Wheat. 304.9

2. Certiorari should be granted to determine whether

petitioners have been denied rights guaranteed to them by

9Petitioners assume that this Court’s holding that the state ground

of decision is inadequate to bar review of the federal questions is not

now subject to reexamination by the Court. Tyler v. Magwire, 17

Wall. 253, 283-284; N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 360 U.S. 240, 245, and

cases cited.

14

the Thirteenth Amendment and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982

(Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 21).10

Last Term, in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., supra, the

Court held that 42 U.S.C. § 1982, which was part of § 1

of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 “bars all racial discrimina

tion, private as well as public, in the sale or rental of

property, and that the statute, thus construed, is a valid

exercise of the power of Congress to enforce the Thirteenth

Amendment.” 392 U.S. at 413 (emphasis in original). The

Court in the Jones case did not specifically consider 42

U.S.C. § 1981. However, since that section also originated

in § 1 of the Act of 1866, the Court by implication held

that § 1981 similarly “bars all racial discrimination, private

as well as public,” insofar as it affects the right of Negroes,

inter alia, “ to make and enforce contracts.” 392 U.S. at

413, 441-442 n. 78.

The complaint in the Freeman case embodied two causes

of action: one alleging wrongful interference by respondents

with performance of the deed of lease between Sullivan and

Freeman, and the other asserting wrongful deprivation by

respondents of Freeman’s full use and enjoyment of the

leasehold estate demised to Freeman under the deed of

lease. By disapproving the assignment of share No. 290 to

Freeman and thus preventing performance of the contract

between Sullivan and Freeman solely because of the latter’s

race, respondents violated Freeman’s right guaranteed by

§ 1981 to make and enforce contracts under the same con

ditions as white persons. Freeman’s rights guaranteed him

by § 1982 were also violated by respondents. Thus, since

share No. 290 was an integral part of the leasehold estate

conveyed from Sullivan to Freeman and represented part of

the value for which Freeman paid the rent specified in the

/0The provisions of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982 are also at issue in

Daniel v. Paul, No. 488, October Term 1968, certiorari granted

December 9, 1968. The Court’s concurrent consideration of the

Daniel case and the one at bar would be beneficial from the standpoint

of clarifying the scope and effect of these statutory provisions.

15

lease, respondents’ refusal to approve the assignment violated

Freeman’s right under that section to lease and hold real

property without restriction on account of his race. Fur

ther, the membership share in Little Hunting Park, Inc., a

non-stock corporation, in itself constitutes personal property

and hence comes within the terms of § 1982. Hyde v.

Woods, 94 U.S. 523; Page v. Edmunds, 187 U.S. 596; Baird

v. Tyler, 185 Va. 601, 39 S.E.2d 642, 645-646. It is clear,

therefore, that the Freemans have been deprived of rights

falling squarely within the ambit of §§ 1981 and 1982 if the

statute “means what it says.” Jones, supra, 392 U.S. at

421.

In dismissing Freeman’s complaint, the trial court relied

on the provision of the corporation’s by-laws which condi

tioned Sullivan’s assignment of share No. 290 on the

approval of the board of directors. In this respect, the situ

ation here is no different than in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U.S. 1, where the property owner similarly did not have an

unlimited right to transfer his property. It too was subject

to a racially restrictive covenant which was a “condition

precedent” to the right of sale. 334 U.S. at 4. The exer

cise, therefore, by the board of directors of its “right” to

approve assignments and determine membership eligibility

on the basis of race amounts to nothing less than the

explicit racial covenant in Shelley. Thus, whether expressly

denominated a racial covenant or a right of approval is of

no moment;;i it remains a racial restriction on the use or

transfer of property and hence is invalid under the 1866

statute.

3. As well as creating rights for Negroes to be free from

discriminatory treatment, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982 impose

correlative obligations on persons not to deal discriminatorily 11

11 Lauderbaugh v. Williams, 409 Pa. 351, 186 A.2d 39; Mountain

Springs Ass’n v. Wilson, 81 N.J. Super. 564, 196 A.2d 270, 275-277;

Tuckerton Beach Club v. Bender, 91 N.J. Super. 167, 219 A.2d 529;

and see Harris v. Sunset Islands Property Owners, Inc., 116 So. 2d 622

(Fla.).

16

with Negroes. Thus, if Sullivan had refused to assign share

No. 290 to Freeman because of the latter’s race he would

have violated the statute.

Sullivan was expelled from the corporation, and his two

shares were revoked, however, as a direct result of his having

dealt with Freeman, as the statute requires, on a non-

discriminatory basis, and because he sought to reverse the

directors’ discriminatory refusal to approve the assignment

in order that he could perform his obligation to Freeman

under their contract/2 The expulsion was unquestionably

retaliatory, and as “a matter of statutory construction and

for reasons of public policy . . . cannot be permitted.” Ed

wards v. Habib, 397 F.2d 687, 699 (C.A.D.C.), and cases

cited at n. 38. Sullivan “was expelled from the association

for doing that which the law . . . not only authorizes but

encourages.” State ex rel. Waring v. Georgia Medical Soci

ety, 30 Ga. 608, 629. The action was therefore contrary to

public policy and he is entitled to reinstatement. Ibid. Ac

cord: Malibou Lake Mountain Club v. Robertson, 219 Cal.

App. 2d 181, 33 Cal. Rptr. 74, 77; Spayd v. Ringing Rock

Lodge No. 665, 270 Pa. 67, 113 Atl. 70; Bernstein v.

A lame da-Contra Costa Medical Assn, 139 Cal. App. 2d 241,

293 P.2d 862, 865; Thompson v. Grand International Bro

therhood o f Locomotive Engineers, 41 Tex. Civ. App. 176,

91 S.W. 834, 838. Cf. National Labor Relations Board v.

Industrial Union o f Marine and Shipbuilding Workers, 391

U.S. 418, 424-425.

Furthermore, the Court recognized in Barrows v. Jackson,

346 U.S. 249, that to sanction “punishment” of a person

because he has refused to discriminate would be to render

nugatory the rights of Negroes to be free from discrimina

tion. As the Court stated there, “The law will permit

respondent to resist any effort to compel her to observe

^Sullivan’s membership in the association, including his right to

assign his share, was also based on a contract in the form of the cor

porate by-laws. The directors’ invocation of this contract to disapprove

the assignment of Sullivan’s share to Freeman on racial grounds thus

independently violated 42 U.S.C. § 1981, a matter which only Sulli

van, who was bound by the by-laws, was in a position to protest.

17

such a covenant . . . since she is the only one in whose

charge and keeping reposes the power to continue to use

her property to discriminate or to discontinue such use.”

346 U.S. at 259. Similarly here, for the law to sanction

Sullivan’s punishment by expulsion because of his refusal to

discriminate would render Freeman’s rights under §§ 1981

and 1982 illusory, indeed.13

4. In addition to the statutory grounds for reversal of

the court below, there are compelling constitutional reasons

why its decision should not stand. It is well recognized

that where facilities are built and operated primarily for

public benefit and their operation is essentially a public

function, they are subject to the limitations to which the

State is subject and cannot be operated in disregard of the

Constitution. Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296; Marsh v.

Alabama, 326 U.S. 501; Amalgamated Food Employees

Union Local 590 v. Logan Valley Plaza, Inc., 391 U.S.

308.14 The record here shows that Little Hunting Park, like

Baconsfield Park which was the subject of Evans v. Newton,

performs the public function of providing recreation for

members of the community and, accordingly may not be

operated on a racially discriminatory basis. Respondent

association was organized and incorporated for the express

purpose, as stated in its certificate of incorporation, of

operating “a community park and playground facilities” for

“community recreation purposes” (T. 184-185). Pursuant

to this object, it operated its park and swimming pool for

11 years, making its facilities open to everyone who lived in

the geographic area defined in the by-laws. Consistent with

/ ?Although the statute declares the rights of Negroes not to be

discriminated against, Sullivan, a Caucasian, has standing to rely on

the invasion of the rights of others, since he is “the only effective

adversary” capable of vindicating them in litigation arising from his

expulsion. Barrows, supra, 346 U.S. at 259.

^Accord: Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 \ Public Utilities Comm’n

v. Pollack, 343 U.S. 451 \Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital,

323 F.2d 959, 968 (C.A. 4), certiorari denied, 376 U.S. 938.

18

its stated purpose, the corporation never pursued a policy

of exclusiveness. It was not until 1965, when Freeman was

disapproved, that there was a departure from the corporate

purpose, making the park available to everyone in the com

munity, except Negroes./5

The impact on the community of the racial policy here is

even greater than it was in Evans v. Newton. For, rather

than being a mere prohibition against the use of a public

recreation facility by Negroes, Little Hunting Park possesses

the power to significantly affect the racial composition of

the community which it serves.

There can be little doubt that the availability of a com

munity swimming pool and recreation facility is a major

factor enhancing the desirability and value of residential

p r o p e r t y . T h e real estate advertisements in any metropol-

^T he trial court’s finding that Little Hunting Park is a “private

social club” is neither supported by the record nor dispositive of the

issues in this case. As in the cases just cited, “private” ownership is

not determinative if the entity performs a public function. Unlike a

conventional private club, membership in Little Hunting Park, Inc. is

not personal to the individual; rather, multiple memberships for

investment purposes are permitted and may be held by corporate

bodies as well as individuals. Further, the corporation has never exer

cised any policy of genuine selectivity in passing on applicants for

membership and assignment. The sole requirement for membership

specified by its charter and by-laws is residence within a specified

geographical area; within that area, it “is open to every white person,

there being no selective element other than race.” Evans v. Newton,

supra, 382 U.S. at 301. As the Fourth Circuit recently declared,

“ [Sjerving or offering to serve all members of the white population

within a specified geographic area is certainly inconsistent with the

nature of a truly private club.” Nesmith v. Young Men’s Christian

Ass’n o f Raleigh, N.C., 397 F.2d 96, 102. See also, Rockefeller

Center Luncheon Club, Inc. v. Johnson, 131 F. Supp. 703, 705 (S.D.

N.Y.); United States v. Richberg, 398 F.2d 523 (C.A. 5).

^Expert testimony to this effect was offered by petitioners in the

court below (T. 133-136, 138, 146-147). Also see, Urban Land Insti

tute, Open Space Communities in the Market Place (Tech. Bulletin

57, 1966), 7, 21, 41, 47-48 (Plaintiffs’ Exh. 28).

19

itan newspaper reveal the emphasis that is placed on the

accessibility of a swimming pool in a neighborhood, and

attest to the great importance that is attached to this feature

in marketing homes.77

However, the evidence in this case shows that munici

pally-owned public swimming pools are virtually non-existent

in the Washington metropolitan area of Northern Virginia;

the “public function” of providing “mass recreation” (Evans

v. Newton, supra, 382 U.S. at 302) through community

swimming pools has been assumed by privately organized

recreation associations.* 75 Because of the “abdication” by

local municipalities of this “ traditional governmental func

tion” (Mulkey v. Reitman, 64 Cal. 2d 529, 413 P.2d 825,

832, aff’d, 387 U.S. 369), a significant role is played by

“private” associations such as Little Hunting Park in ful

filling this community need. Accordingly, Negroes will be

discouraged from moving into a neighborhood where such

an association denies them access to the only convenient

recreation facilities because of their race. Conversely, a

property owner owning a share in such an association will

be deterred from selling or renting his house to a Negro,

since the Negro will be ineligible for purchase or assignment

of the share. Accordingly, since as shown, a house has

greater market value if the purchaser or tenant is eligible to

use such a facility, if a Negro is able to obtain housing

in a community where he is barred from the swimming pool

association in which the seller or landlord is a shareholder,

77“ [T]he community swimming pool is considered by most builders

as one of their most popular sales appeals to people of all ages and

incomes.” 29 Practical Builder No. 2, p. 94 (Feb. 1964) (T. 148,

Plaintiffs’ Exh. 29). See also T. 148-151, Plaintiffs’ Exh. 30.

7SIn the Northern Virginia metropolitan suburbs with a population

of nearly 700,000 persons, there are only two municipally owned

swimming pools and one lake for swimming (T. 138-139). By con

trast, in this same area there are nearly 50 community swimming

pools of the same type as Little Hunting Park. In the suburbs of

Maryland and Virginia there are over 105 pools of this type. The

Washington Post, p. A20, June 12, 1967.

20

there is an immediate loss in the value of the residence

which must be borne by one of the parties to the transac

tion. Thus, an owner in these circumstances will either

refuse to sell or rent to a non-Caucasian or else will require

him to pay a higher price than the property is worth absent

access to the recreation facility. “Solely because of their

race, non-Caucasians will be unable to purchase, own, and

enjoy property on the same terms as Caucasians.” Barrows

v. Jackson, supra, 346 U.S. at 254. And if this pattern is

widespread, and as the record shows to be true for Northern

Virginia, governments are unwilling to duplicate privately

owned community recreation facilities with municipally

operated facilities, non-Caucasians will be discouraged from

purchasing or renting housing in whole sections of the

State.

Undoubtedly, a significant factor underlying this Court’s

decision in Barrows v. Jackson, supra, and the closely related

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, was recognition of the fact

that a racially restrictive covenant is usually part of a sys

tem, the effect of which can be to blanket an entire com

munity with racial restrictions, which create Negro and

white ghettos. The racially discriminatory policy of Little

Hunting Park, no less than the discriminatory policies of

those who enter into racial covenants, creates a system

which is the equivalent of, and has the effect of a racial

zoning ordinance. It is “as if the State had passed a statute

instead of leaving this objective to be accomplished by a

system of private contracts, enforced by the State.” Bell v.

Maryland, 378 U.S. 226, 329 (dissenting opinion of Justice

Black), quoted in Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369, 385

(concurring opinion of Justice Douglas). Cf. Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U.S. 60./9

;9 It should be further noted that the instant case, like Shelley v.

Kraemer, involves an agreement voluntarily entered into by a white

property owner and a Negro attempting to acquire property, with

attempted intervention by a third party seeking to prevent perform

ance. Shelley and Barrows make clear that where, as here, “both

parties are willing parties” to such a contract a state court may not

21

5. Constitutional considerations provide further warrant

for reversal of the state court’s affirmance of Sullivan’s

expulsion from the corporation. If the directors’ summary

expulsion of Sullivan because of his dissent from their racial

policy is allowed to stand, it will have the effect of granting

them an immunity from criticism to which they are not

constitutionally entitled. By assuming roles of leadership in

Little Hunting Park, Inc.—an organization devoted to devel

oping and operating a community recreation facility—the

directors necessarily became parties to any matters of public

interest or public controversy in which the association might

become involved. It is apparent that whatever way the

directors had acted with respect to the Freeman assignment,

their decision was likely to be a subject for comment and

criticism by members of the association, as well as other

persons with an interest in the affairs of the community.

The directors were not entitled, however, to expel Sullivan

because he voiced opposition to their discriminatory racial

policy. Since, as we have shown above, the public function

performed by Little Hunting Park, Inc. makes it subject to

constitutional limitations, forfeiture of an individual’s rights

under the First Amendment may not be made a condition

of use of its facilities. Marsh v. Alabama, supra, 326 U.S.

501; Amalgamated Food Employees Union Local 590 v.

Logan Valley Plaza, Inc., supra, 391 U.S. at 308; and see

Pickering v. Board o f Education, 391 U.S. 563.“° * 20

give legitimacy to the effort to defeat the contract “on the grounds

of the race or color of one of the parties.” Bell v. Maryland, supra,

378 U.S. at 331 (dissenting opinion of Justice Black) (emphasis in

original). It is, of course, immaterial whether the racial restriction is

relied on as a basis for seeking affirmative relief, or, as here, is raised

as a defense. Spencer v. Flint Memorial Park Ass’n, 4 Mich. App.

157, 144 N.W.2d 622, 626; Clifton v. Puente, 218 S.W.2d 272, 274

(Tex. Civ. App.). And see, Rice v. Sioux City Memorial Cemetery,

349 U.S. 70, 80 (dissenting opinion).

20Courts have frequently been guided by the First Amendment in

protecting the right of dissent within voluntary associations. See, e.g.,

Crossen v. Duffy, 90 Ohio App. 252, 103 N.E.2d 769, 778; Mitchell

v. International Ass’n o f Machinists, 196 Cal. App. 2d 796, 16 Cal.

22

The state court’s sanctioning of Sullivan’s expulsion from

the recreation association because of his criticism of the

directors’ erection of a racial barrier to the use of its facili

ties is contrary to this Court’s decision in Curtis Publishing

Co. v. Butts, supra, 388 U.S. 130, holding that the First

Amendment protects criticism of “public figures” who par

ticipate in events of public concern to the community. As

was stated there (in the concurring opinion of Chief Justice

Warren writing for a majority of the Court) with respect to

the urbanized society that we know today:

In many situations, policy determinations which tra

ditionally were channeled through formal political

institutions are now originated and implemented

through a complex array of boards, committees,

commissions, corporations and associations, some

only loosely connected with the Government. This

blending of positions and power has also occurred in

the case of individuals so that many who do not

hold public office at the moment are nevertheless

intimately involved in the resolution of important

public questions or by reason of their fame, shape

events in areas of concern to society at large.

Viewed in this context then, it is plain that

although they are not subject to the restraints of the

political process, “public figures,” like “public offi

cials,” often play an influential role in ordering

society. 388 U.S. at 163-164.

There can be little doubt that Little Hunting Park, Inc.

plays the type of public role in the community that is

referred to by the Chief Justice, and that the directors of

the corporation are “public figures,” as he used the term in

the Curtis Publishing case. Further, as that case holds, it is

violative of the First Amendment for the State to lend its

Rptr. 813, 816-820; Madden v. Atkins, 4 N.Y.2d 283, 151 N.E.2d

73, 78; Gallagher v. American Legion, 154 Misc. 281, 277 N.Y.S. 81,

85, affd 242 App. Div. 604, 271 N.Y.S. 1012; Hurwitz v. Directors

Guild o f America, 364 F.2d 67, 75-76 (C.A. 2), certiorari denied, 385

U.S. 971.

23

judicial processes to vindicate the aggrievement asserted by

a public figure against critics of his manner of participating

in events of public interest. Applied to the instant case,

this means that the Virginia court could not sanction the

directors’ action in expelling Sullivan from the association

merely because he refused to acquiesce in their discrimina

tory racial policy, but instead exercised his right to speak

out critically concerning the matter. By holding that Sulli

van’s dissent from the association’s policy constituted justi

fication for his expulsion, the trial court invoked a standard

of state law which had the effect of depriving Sullivan of

rights protected by the First Amendment. Pickering v.

Board o f Education, 391 U.S. 563.21 This clearly is state

action falling within the ambit of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. “The test is not the form in which state power has

been applied, but whatever the form, whether such power

has in fact been exercised.” New York Times Co. v. Sulli

van, 376 U.S. 254, 265. Accord: Curtis Publishing Co. v.

Butts, supra, 388 U.S. at 146-155.

In addition, to permit the state court to sanction Sulli

van’s expulsion from Little blunting Park, Inc. for protesting

Freeman’s exclusion from the community park would be to

allow the State to “punish” him for his failure to abide by

the directors’ determination that he must “discriminate

against non-Caucasians in the use of [his] property. The

result of that sanction by the State would be to encourage”

the use and observance of such racial restrictions on prop

erty. Barrows v. Jackson, supra, 346 U.S. at 254. See also

Reitman v. Mulkey, supra, 387 U.S. at 380-381.

6. The state court’s rejection of the appeals was arbitrary

and unreasonable, and is not a bar to this Court’s review of

the important federal questions presented in this case. The

21 Little weight should be given to the board of directors’ determi

nation that Sullivan’s conduct was “inimicable” [sic] to the corpo

ration’s members in view of the patent procedural deficiencies in the

“hearing” granted him prior to his expulsion {supra, p. 11). See Pick

ering v. Board o f Education, supra, 391 U.S. at 578-579 n. 2.

24

decree was entered in the Sullivan case by the trial court on

April 12, 1967, and in the Freeman case on May 8, 1967,

It is undisputed, as shown by the affidavits of counsel filed

in the trial court, and incorporated in the record, that on

the morning of June 9, 1967, counsel for the petitioners,

Mr. Brown, notified Mr. Harris, counsel for the respondents,

by telephone that he would submit the reporter’s transcripts

in the two cases to the trial judge that afternoon. Mr. Brown

further informed Mr. Harris that because of errors in the

transcripts, he was filing motions for correction of the rec

ord, noticing them for hearing one week hence, Friday,

June 16, 1967, which was the court’s next Motion Day.

Finally, Mr. Brown told counsel that he would request the

trial judge to defer signing both transcripts for a 10-day

period to allow time for Mr. Harris to consent to the

motions or to have them otherwise acted on by the court.

That same day, June 9, Mr. Brown wrote Mr. Harris to con

firm their telephone conversation, and in his letter Mr.

Brown reiterated that he would request the judge not to

sign the transcripts until they had been corrected. The

afternoon of June 9, when Mr. Brown sought to tender the

transcripts to the judge, the latter was away from his office

and not expected to return that day, so Mr. Brown left the

transcripts as well as a copy of his letter to Mr. Harris with

the judge’s secretary; the judge later ruled that the tender

of the transcripts was made on Monday, June 12, the day

that he received them. Meanwhile, motions to correct the

two transcripts were served on Mr. Harris, along with the

notice that they would be brought to hearing before the

court on Friday, June 16.

On Monday morning, June 12, the trial judge acknowl

edged to Mr. Brown over the telephone that he had received

the transcripts and the motions to correct the record. Pur

suant to Mr. Brown’s request, he agreed to defer signing the

transcripts until the motions had been acted on. That same

day, Mr. Harris wrote to Mr. Brown in reference to their

telephone conversation of the preceding Friday, noting that

because he did not have copies of the transcripts he could

25

not consent to the requested corrections without reviewing

the testimony.

On Friday, June 16, the judge stated in court that the

transcripts had been available in his office for one week,

since the preceding Friday, for examination, but since it

appeared that Mr. Harris had not examined them, the

motions to correct the record would not be acted on until

Mr. Harris indicated his agreement or disagreement with

the changes requested. In order to facilitate Mr. Harris’

examination of the transcripts, Mr. Brown lent him the

petitioners’ duplicate copies, which Mr. Harris had in his

possession from 1:20 p.m., June 16, until 6:30 p.m., June

19, at which time they were returned to Mr. Brown. Upon

returning the transcripts, Mr. Harris stated that he had no

objections to any of the corrections requested by the peti

tioners or to the entry of orders granting the motions to

correct the transcripts. Mr. Harris then signed the proposed

orders granting the motions which Mr. Brown had prepared.

The proposed orders were submitted to the trial judge on

June 20, who thereupon entered them, and after the neces

sary corrections were made, signed the transcripts on that

date.

On the basis of the foregoing facts and relevant decisions

of the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, it is clear that

petitioners fully complied with Rule 5:1, Sec. 3(f). That

court has repeatedly held that the rule is complied with

when, as here, opposing counsel has actual notice of the

tender of the transcript to the trial judge and has a reasona

ble opportunity to examine the transcript for accuracy

before it is authenticated by the judge. See, Bacigalupo v.

Fleming, 199 Va. 827, 102 S.E.2d 321, 326; Hyson v.

Dodge, 198 Va. 792, 96 S.E.2d 792, 798-799; Kornegay v.

City o f Richmond, 185 Va. 1013, 41 S.E.2d 45, 48-49. In

construing the rule, the Virginia court follows the practice

of considering the facts and circumstances of each case, and

on numerous occasions has overruled objections to appeals

where, as here, it appears that the purpose of the rule has

26

been satisfied and the appellee has not shown that he was

“in any way prejudiced” by the procedure followed. Stokely

v. Owens, 189 Va. 248, 52 S.E.2d 164, 167.22 The Baciga-

lupo case, supra, involved circumstances almost identical to

those presented here, and illustrates the liberal construction

customarily placed by the Virginia court on the rule in

question. There the trial judge, after ruling that the prior

notice to opposing counsel of tender had not met the

requirement of reasonableness, advised the parties that he

would defer signing the transcript for seven days to afford

counsel opportunity to examine the transcript and indicate

his objections, if any. In holding that this procedure com

plied with Rule 5:1, Sec. 3(f), the Supreme Court of Appeals

stated (102 S.E.2d at 326):

The requirement that opposing counsel have a rea

sonable opportunity to examine the transcript sets

out the purpose of reasonable notice. If, after receipt

of notice, opposing counsel be afforded reasonable

opportunity to examine the transcript, and to make

objections thereto, if any he has, before it is signed

by the trial judge, the object of reasonable notice

will have been attained.

It is thus clear that even if insufficient advance notice

was given to respondents’ counsel, Mr. Harris, of the tender

of the transcripts to the judge, this deficiency was cured by

the ample opportunity that Mr. Harris had after the tender

to examine the transcripts and the motions to correct the

transcripts, and to make any objections thereto. Further,

Mr. Harris’ signing of the proposed orders granting the

motions to correct the transcripts reflect the fact that he

had examined the transcripts and the proposed corrections,

and “waived” any further objections that he had to the

procedure being followed. Kornegay v. City o f Richmond,

22See also, Cook v. Virginia Holsom Bakeries, Inc., 207 Va. 815,153

S.E.2d 209, 210; Grimes v. Crouch, 175 Va. 126, 7 S.E.2d 115, 116-

117; Town o f Falls Church v. Myers, 187 Va. 110, 46 S.E.2d 31,

34-35; Taylor v. Wood, 201 Va. 615, 112 S.E.2d 907, 910.

27

supra; Grimes v. Crouch, supra; Taylor v. Wood, supra.

Although the state court, in the opinion it cites as the basis

for rejecting the appeals, characterized the rule in question

as “jurisdictional” (Snead v. Commonwealth, 200 Va. 850,

108 S.E.2d 399, 402), it is clear from the Bacigalupo deci

sion and other cases cited above, that the court exercises

considerable discretion in determining whether it has been

complied with. The state court thus not only ignored its

own precedents in reaching the result it did here, but under

the mode of practice that it allows, could have exercised its

discretion to hear the appeals. That court’s “discretionary

decision” to deny the appeals did “not deprive this Court

of jurisdiction to find that the substantive issue[s]” were

properly before it. Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375, 389;

Shuttlesworth v. City o f Birmingham, 376 U.S. 339. See

also, Ward v. Board o f County Commissioners, 253 U.S. 17,

22; and cases cited supra, p. 5, n. 3.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the Court should grant this

petition for a writ of certiorari and decide the case on the

merits. In the event that the Court holds for the petitioners,

it would appear that another remand to the Supreme Court

of Appeals of Virginia would be futile, in view of that

court’s insistence that it does not have jurisdiction over the

proceeding. Therefore, petitioners respectfully suggest that

the Court may wish to treat this petition as a petition for a

writ of certiorari to the Circuit Court of Fairfax County,

Virginia, where the cases were tried. See Callender v. Florida,

383 U.S. 270, 380 U.S. 519. Cf. Naim v. Naim, 350 U.S.

985. Alternatively, the Court could formulate an order

reversing the judgments of the courts below, and directing

28

the Circuit Court to enter an appropriate decree, including

provision for such damages as that court may fix. See

Stanley v. Schwalby, 162 U.S. 255, 279-283; 28 U.S.C.

§ 2106; 28 U.S.C. § 1651(a).25

Respectfully submitted,

Allison W. Brown, Jr.

Suite 501, 1424-16th Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Peter Ames Eveleth

217 Fifth Street, S. E.

Washington, D. C. 20003

Robert M. Alexander

2011 S. Glebe Road

Arlington, Virginia 22204

Attorneys for Petitioners

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Of Counsel

January 1969.

25“The power to enter judgment and, when necessary, to enforce

it by appropriate process, has been said to be inherent in the Court’s

appellate jurisdiction.” Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 467 (dissenting

opinion of Justice Harlan). See Williams v. Bruffy, 12 Otto 248, 255-

256; Tyler v. Magwire, supra, 17 Wall, at 289-293; Martin v. Hunter’s

Lessee, supra, 1 Wheat, at 361 \ McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316,

437; Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1, 239; Kreshik v. St. Nicholas

Cathedral, 63 U.S. 190, 191.

29

APPENDIX A

STATUTES

42 U.S.C. Section 1981. Equal rights under the law

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States

shall have the same right in every State and Territory to

make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence,

and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings

for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by

white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and

to no other. R.S. § 1977.

42 U.S.C. Section 1982. Property rights of citizens

All citizens of the United States shall have the same right,

in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white citizens

thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey

real and personal property. R.S. § 1978.

CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES

Article VI

* * *

This Constitution, and the laws of the United States

which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties

made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the

United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the

judges in every State shall be bound thereby, anything in

the Constitution of laws of any State to the contrary not

withstanding.

* * *

Amendments

Article I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment

of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or

30

abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right

of people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Govern

ment for a redress of grievances.

* * *

Article XIII

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude,

except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall

have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United

States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this

article by appropriate legislation.

* * *

Article XIV

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United

States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens

of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States,

nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law; nor deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the

laws.

* * *

RULES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS

OF VIRGINIA

Rule 5:1. The Record on Appeal

Sec. 3. Contents of Record

* * *

(f) Such a transcript or statement not signed by counsel

for all parties becomes part of the record when delivered to

the clerk, if it is tendered to the judge within 60 days and

signed at the end by him within 70 days after final judgment.

31

It shall be forthwith delivered to the clerk who shall certify

on it the date he receives it. Counsel tendering the transcript

or statement shall give opposing counsel reasonable written

notice of the time and place of tendering it and a reasona

ble opportunity to examine the original or a true copy of

it. The signature of the judge, without more, will be deemed

to be his certification that counsel had the required notice

and opportunity, and that the transcript or statement is

authentic. He shall note on it the date it was tendered to

him and the date it was signed by him.

* * *

32

APPENDIX B

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1967.

SULLIVAN e t a l . v. LITTLE HUNTING PARK,

INC., ET AL.

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA.

No. 1188. Decided June 17, 1968.

P er C u r i a m .

The petition for a writ of certiorari is granted and the

judgment is vacated. The case is remanded to the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia for further consideration in

light of Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409,

decided this date.

Mr. Justice Harlan and Mr. Justice White dissent for the

reasons stated in Mr. Justice Harlan’s dissenting opinion in

Jones v. James H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 449, decided this

date.

33

SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS

OF VIRGINIA

Present: All the Justices

PAUL E. SULLIVAN, ET AL.

-v- Record No. R-8257

LITTLE HUNTING PARK, INC.,

ET AL.

T. R. FREEMAN, JR., ET AL.

-v- Record No. R-8176

LITTLE HUNTING PARK, INC.,

ET AL.

On August 4, 1967, a petition for appeal was filed in this

court by Paul E. Sullivan, his wife, and their seven minor

children. On August 25, 1967, a petition for appeal was

filed by T. R. Freeman, Jr., his wife, and their two minor

children. The petitions sought the reversal of decrees of the