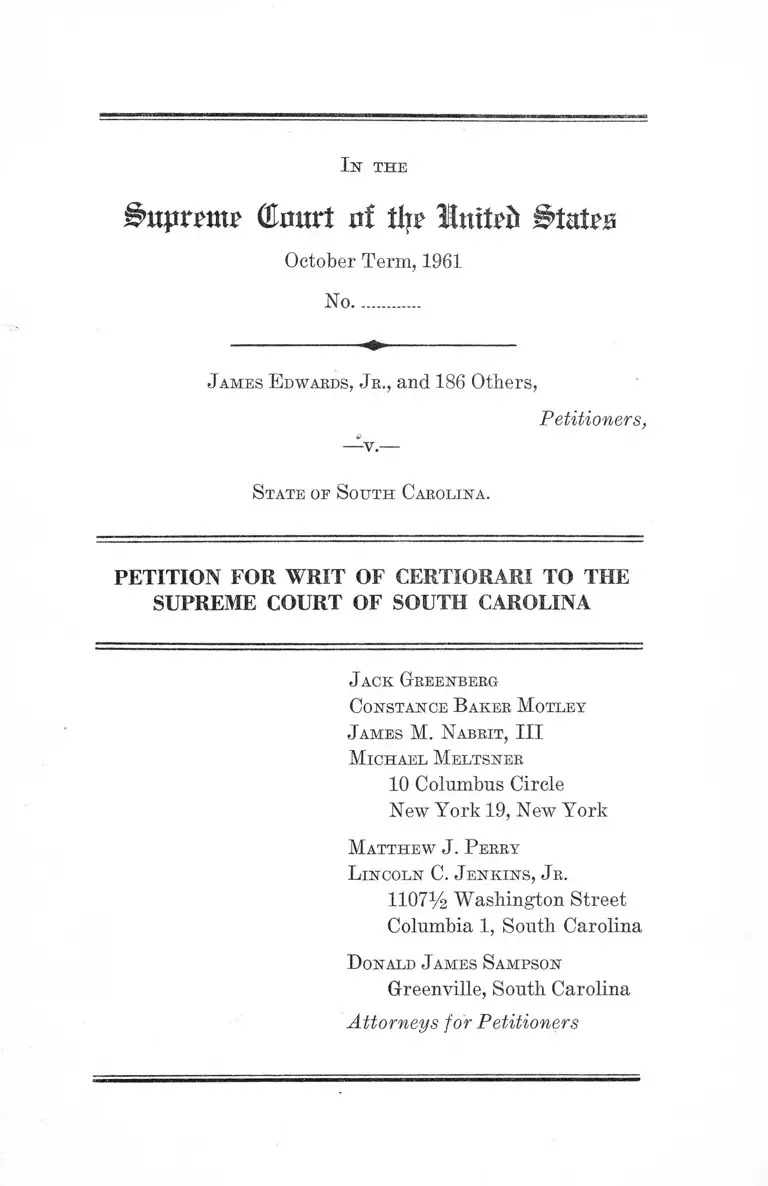

Edwards v. South Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Edwards v. South Carolina Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of South Carolina, 1961. ed2ebc98-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a62a481f-75db-4eb9-952e-687776664b0c/edwards-v-south-carolina-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-south-carolina. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In' the

§>upt?m ? Glmirt nf tljp

October Term, 1961

No............

J am es E dwards, J r ., and 186 Others,

Petitioners,

— v .—

S tate op S o u th Caro lin a .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

J ack G reenberg

C onstance B aker M otley

J am es M . N abeit , III

M ic h ael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

M a t t h e w J . P erry

L in co ln C. J e n k in s , Jr.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia 1, South Carolina

D onald J am es S am pson

Greenville, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below............................................. 1

Jurisdiction ................................................ ...................... 1

Questions Presented .................................... 2

Constitutional Provisions Involved ...... 2

Statement ................................................................ 2

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided .. 8

Reasons for Granting the Writ ..................................... 10

I. Petitioners’ conviction on warrants charging that

their conduct “ tended directly to immediate vio

lence and breach of the peace” is unconstitu

tional in that it rests on no evidence of violence

or threatened violence ......................................... 11

II. Petitioners’ convictions were obtained in viola

tion of their rights to freedom of speech, assem

bly and petition for redress of grievances in

that they were convicted because their protected

expression tended to lead to violence and breach

of the peace on the part of others ...................... 16

C o n c l u s io n ......................................................................... 20

Appendix ........................................................................... la

Opinion of the Richland County Court .......................... la

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina ....... la

Denial of Petition for Rehearing ................................. 16a

11

T able of C ases

page

Beatty v. Gillbanks (1882) L. E. 9 Q, B. Div. 308 .... 19

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296...........11,12,15,17,18

Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196 ............................ ......... 11

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ......................................... 19

Be Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ............................. 11,15

Feiner v. New York, 300 N. Y. 391, 91 N. E. 2d 319.......3,10

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 ..............................12,18

Garner v. Louisiana, 7 L. ed. 2d 207 .............. 11,12,14,16

Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496 ......................12,15,16,17,18

Runs v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 ................................. 18

Robeson v. Fanelli, 94 F. Supp. 62 (S. D. N. Y. 1950) .... 17

Rockwell v. Morris, 10 N. Y. 721 (1961) cert, denied

7 L. ed. 2d 131........................................................15,18,19

Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877 (8th Cir. 1947) cert.

denied 332 U. S. 851 ................................. 12,15,17,18,19

State v. Langston, 195 S. C. 190, 11 S. E. (2d) 1 ........... 14

Strutwear Knitting Co. v. Olsen, 13 F. Supp. 384 (D. C.

Minn. 1936) ................................................................... 19

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ............................. 12,19

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199......................... 11,16

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ............................. 18

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542 ...................... 16

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 ............................. 15,16

O th e r A u th o rity

8 American Jurisprudence 834 et seq. 14

I n th e

j§>uprTmT (£mxt of fl?s? H&nxUh ^Utm

October Term, 1961

No............

J am es E dwards, J r ., and 186 Otters,

Petitioners,

—y.—

S tate oe S o u th Carolin a .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

entered in the above entitled case on December 5, 1961,

rehearing of which was denied on December 27, 1961.

Citation To Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina,

which opinion is the final judgment of that Court, is as yet

unreported and is set forth in the appendix hereto, infra

pp. 10a-15a. The opinion of the Richland County Court is

unreported and is set forth in the appendix hereto, infra

pp. la-9a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

was entered December 5, 1961, infra pp. 10a-15a. Petition

2

for Rehearing was denied by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina on December 27, 1961, infra p. 16a.

The Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1257(3), petitioners

having asserted below and asserting here, deprivation of

rights, privileges and immunities secured by the Constitu

tion of the United States.

Questions Presented

Whether petitioners were denied due process of law as

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States:

1. When convicted of charges that their conduct, which

was an assembly to express opposition to racial segregation

on the State House grounds, “tended directly to immediate

violence and breach of the peace” on a record containing no

evidence of threatened, imminent, or actual violence.

2. When convicted of the common law crime of breach of

the peace because exercise of their rights of free speech and

assembly to petition for a redress of grievances allegedly

“ tended” to result in unlawful conduct on the part of other

persons opposing petitioners’ views.

Constitutional Provisions Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

Warrants issued against petitioners charged them with

common law breach of the peace on March 2, 1961 at the

3

South Carolina State Capitol grounds. The warrants al

leged inter alia that they:

“ . . . did commit a breach of the peace in that they,

together with a large group of people, did assemble

and impede the normal traffic, singing and parading

with placards, failed to disperse upon lawful orders of

police officers, all of which tended directly to immediate

violence and breach of the peace in view of existing

conditions” (ft. 3,). (Emphasis supplied.)

The City Manager of Columbia who was supervising the

police department at the time (R. 18-19) testified that “My

official reason for dispersing the crowd was to avoid pos

sible conflict, riot and dangers to the general public. . . . ”

(R. 16-17).

The Chief of Police testified that he took action “ [t]o

keep down any type of violence or injury to anyone” (R.

46; and see R. 53, 100, 101, 106, to the same effect).

The trial court sitting without a jury found petitioners

guilty of common law breach of the peace. The Court

imposed fines of $100 or 30 days in jail in most cases; in

many of these cases one-half of the fine was suspended.

In a few cases the defendants were given $10 fines or five

days in jail (R. 78 f 155; 217-218; 229-230).

The Richland County Court affirmed, principally upon

authority of People v. Feiner, 300 N. Y. 391, 91 N. E. 2d

319,»concluding there was a “ dangerous” (R. 238) situation

and actions which a “ reasonable thinking citizen knows or

should know would stir up passions and create incidents

of disorder” (R. 239).

The Supreme Court of South Carolina affirmed on the

ground that:

“ The orders of the police officers under all of the

facts and circumstances were reasonable and motivated

4

solely by a proper concern for the preservation of

order and prevention of further interference with traf

fic upon the public streets and sidewalks.”

In fact, the record furnishes no evidence of violence or

even a threat of violence either by or against petitioners.

Nor, indeed, does the record demonstrate that the peti

tioners, who were carrying their placards and walking about

wholly within the State House grounds, had themselves

stopped the sidewalks or traffic; only that bystanders were

attracted who moved on at police request, and that traffic

was somewhat slowed, a condition which did not presage

violence. Either after arrest, or after the police order to

disperse, petitioners sang hymns and patriotic songs in a

singing, chanting, shouting response, as one might find

in a religious atmosphere. All of these facts are developed

at greater length, with appropriate record citations, below,

r , t ! . ’- j '•

j_ The genesis of this criminal prosecutionslies in a decision

of various high school and college students in Columbia,

South Carolina to protest to the State Legislature and

government officials against racial segregation:

“ To protest to the citizens of South Carolina, along

with the Legislative Bodies of South Carolina, our

CL feelings and our dissatisfaction with the present con

dition of discriminatory actions against Negroes, in

general, and to let them know that we were dissatisfied

and that we would like for the laws which prohibited

Negro privileges in this State to be removed” (R. h§8).

The State House is occupied by the State Legislature

which was in session at the time (R.4ST).

The Police Chief recognized that the demonstration was

part of “ a widespread student movement which is designed

to possibly bring about a change in the structure of racial

segregation laws and custom” (R. 49). f

5

The petitioner who testified to" 'this/James Jerome- Kit-

ron, a third year student at Benedict College (JR. 142),

stated that the),petitioners had. met at Zion Baptist Church

on March 2, 1961, divided into groups of 15 to 18 persons

(R. 135), and proceeded to the State House grounds which

occupy two square blocks (R. 168). They are in a horse

shoe shaped area, bounded by a driveway and parking lot

which is “used primarily for the parking of State officials’

cars” (R. 159). There is some passage in and out of this

area by vehicular traffic and by people leaving and enter

ing the State building. In addition, there are main side

walk areas leading into the State Capitol on either side of

the horseshoe area (R. 159). The horseshoe area “ is not

really a thoroughfare” (R. 123). It is an entrance and

exit for those having business in the State House (R. 123).

During the time of the demonstration no traffic was blocked

going in and out of the horseshoe area; no vehicle made any

effort to enter (R. 119).

The students proceeded from the church to the parking

area in these small groups which were, as petitioner Kitron

put it, approximately a half block apart, or as Chief Camp

bell put it, about a third of a block apart (R. 107), although

at various times they moved closer together (R. 107, 169).

But, “ there never was at any time any one grouping of

all of these persons together” (R. 111).

The police informed petitioners “ that they had a right,

as a citizen, to go through the State House grounds as any

other citizen has, as long as they were peaceful” (R. 43,

47, 104, 162). Their permission, however, was limited to

being “allowed to go through the State House grounds one

time for purposes of observation” (R. 162). This took

about half an hour (R. 163). As they went through the

State House grounds they carried signs, such as “ I am

proud to be a Negro,” and “ Down with Segregation” (R,

141). The general feeling of the group was that segrega

6

tion in South Carolina was against general principles of

humanity and that it should be abolished (R. 138).

iJEhere is dispute in the record whether it was before

or after arrest (Compare R. with R. W9) that petition

ers commenced singing religious songs, the “ Star Spangled

Banner” and otherwise vocally expressing themselves, but

there is agreement that none of this occurred until at

least after the police ordered petitioners to disperse (see

R. 38) $2). As the City Manager described it, this was

“a singing, chanting, shouting response, such as one would

get in a religious atmosphere . . . ” (R. f@).f Thereafter the

students were lined up and marched to the City Jail and

the County Jail (R. 18).

The students were at all times well demeaned, well

dressed, orderly (R. 29). The City Manager disagreed

with this designation only to the extent that petitioners

engaged in the religious and patriotic singing described

above (R. 29).

Nowhere in the record, h*fWsewery--ean any evidence h€

found that violence ..occurred/ 5r that violence was threat-

■ ■ * 1 ; - ’ .1 ...

enech The City Manager testified that among the onlookers

he “ recognized possible trouble makers” (R. 33), but “ took

no official action against [the potential trouble makers]

because there was none to be taken. They were not creating

a disturbance, those particular people were not at the time

doing anything to make trouble, but they could have been.”

He did not even “ talk to the trouble makers” (R. 34). When

onlookers were “ told to move on from the sidewalks” they

complied (R. 38). None refused (R. 38).

The City Manager stated that thirty to thirty-five officers

were present (R. 22). The Police Chief of Columbia had

fifteen men in addition to whom were State Highway Patrol

men, South Carolina Law Enforcement officers, and three

Deputy Sheriffs (R. 50). This was, in the City Manager’s

7

words “ ample policemen” (R. 168). But he believed that

“ Simply because we had ample policemen there for their

protection and the protection of others, is no reason for

not placing them under arrest when they refused a lawful

request to move on” (R. 168).

The police had no particular “ trouble makers in mind,”

merely that “you don’t know what might occur and what is

in the mind of the people” (R. 50). Asked “ You were afraid

trouble might occur; from what source?” the Chief replied

“ You can’t always tell” (R. 54). Asked “Are you able, sir,

to say where the trouble was?” he replied, “ I don’t know”

(R. 54). None of the potential “trouble makers” was ar

rested and pedestrians ordered to “move on at [the Chief’s]

command” did so (R. 114).

So far as obstruction of the street or sidewalks is con

cerned, there is a similar absence of evidence. The City

Manager testified that the onlookers blocked “ the side

walks, not the streets” (R. 32). But they cleared the side

walks when so ordered (R. 34). While petitioners “prob

ably did” (R. 109, 111) slow traffic in crossing the streets on

the way to the grounds (R. 109), once there, they were

wholly within,the grounds (R. 188). They did not, as stated

above, block traffic within the grounds (R. -83), no vehicle

4tavmgnnademmei¥orb to enter the parking area during this

period of time. Their singing, however, was said by the

City Manager to have slowed traffic (R. 92). And the

noise, he said, was disrespectful to him (R. 99).

Columbia has an ordinance forbidding the blocking of

sidewalks and petitioners were not charged under this ordi

nance (R. 54). Pedestrians within the grounds could move

to their destinations (R. 48, 52,195). Onlookers moved along

when ordered to by the police (R. 34). There is no evidence

at all, as stated in the charge that traffic congestion tended

to any violence at all.

8

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

The petitioners were tried before the Columbia City

Magistrate of Richland County in four separate trials on

the 7th, 13th, 16th and 27th of March, 1961. At the close

of the prosecution’s case on the 7th of March, petitioners

moved to dismiss the case against them:

“ . . . on the ground that the evidence shows that

by arresting and prosecuting the defendants, the offi

cers of the State of South Carolina and of the City of

Columbia were using the police power of the State of

South Carolina for the purpose of depriving these

defendants of rights secured them under the First and

Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Consti

tution. I particularly make reference to freedom of

assembly and freedom of speech” (R. 76).

This motion was denied (R. 76). Following judgment

of conviction petitioners moved for arrest of judgment or

in the alternative a new trial relying, inter alia, on the

denial of petitioners’ rights to freedom of speech and as

sembly guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States (R. 79, 80). The motions

were denied (R. 80).

Similar motions to dismiss and for arrest of judgment

or in the alternative a new trial all claiming protection of

petitioners’ rights, under the Constitution of the United

States, to freedom of speech and assembly in that the evi

dence showed petitioners “were included in a peaceful and

lawful assemblage of persons, orderly in every respect

upon the public streets of the State of South Carolina”

(R. 134, 201) were made at the trials on the 13th (R. 134,

152, 155), the 16th (R. 201, 214, 218) and the 27th (R, 228,

9

229, 230). These motions were all denied by the trial Court

(R. 135, 152, 155, 201, 214, 218, 228, 229, 230).

Petitioners appealed to the Richland County Court where,

by stipulation, the appeals were treated as one “ since the

facts and applicable law were substantially the same in

each case” (R. 232).

The Richland County Court, upon the authority of Feiner

v. New York, 300 N. Y. 391, 91 N. E. 2d 319 (R. 236, 237,

238) held:

“While it is a constitutional right to assemble in a hall

to espouse any cause, no person has a right to organize

demonstrations which any ordinary and reasonable

thinking citizen knows or reasonably should know would

stir up passions and create incidents of disorder.”

Petitioners appealed to the Supreme Court of the State

of South Carolina, excepting to the judgment below as

follows:

“4. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the

evidence shows conclusively that by the arrest and

prosecution of appellants, the police powers of the

State of South Carolina are being used to deprive

appellants of the rights of freedom of assembly and

freedom of speech, guaranteed them by the First

Amendment to the United States Constitution, and fur

ther secured to them under the equal protection and

due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States” (R. 240).

The Supreme Court of South Carolina, in treating peti

tioners constitutional objections, stated (infra pp. lla-12a):

“While the appellants have argued that their arrest and

conviction deprived them of their constitutional rights

10

of freedom of speech and assembly . . . it is conceded

in argument before us that whether or not any consti

tutional right was denied to them is dependent upon

their guilt or innocence of the crime charged under the

facts presented to the trial Court. If their acts con

stituted a breach of the peace, the power of the State to

punish is obvious. Feiner v. New York, 71 S. Ct. 303,

340 U. S. 315, 95 L. ed. 295.”

The Supreme Court of South Carolina then proceeded to

define breach of the peace generally and found it to include

“ an act of violence or an act likely to produce violence” ,

infra p. 14a, and held that “ the orders of the police officers

under all of the facts and circumstances were reasonable

and motivated solely by a proper concern for the preserva

tion of order and prevention of further interference with

traffic upon the public streets and sidewalks”, infra p. 15a.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

This case raises a question of recurring importance to a

democratic society—the extent to which a state may limit

public expression on issues of national importance and

concern on the ground that such expression may lead to

violence although none in fact has occurred or even been

threatened—answered in the Courts below in a manner con

trary to principles enunciated by this Court.

11

I

Petitioners’ conviction on warrants charging that tiieir

conduct “ tended directly to immediate violence and

breach of the peace” is unconstitutional in that it rests

on no evidence of violence or threatened violence.

It is settled that this Court cannot be concerned with

whether this record proves the commission of some crime

other than that with which petitioners were charged. Con

viction of an accused for a charge that was never made is a

violation of due process. Cole v. Arkansas, 333 U. S. 196;

De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353, 362. It is equally true

that an accused cannot be convicted “ upon a charge for

which there is no evidence.” Garner v. Louisiana, 7 L. ed.

2d 207, 214; Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199, 206.

Petitioners were convicted of common law breach of the

peace, for expressing their disapproval of the racial policies

of the State of South Carolina, upon warrants (E. 2, 3, 156,

157, 225, 226) charging that:

“On March 2, 1961, on State Capitol grounds, on

adjacent sidewalks and streets, did commit a breach

of the peace in that they, together with a large group

of people, did assemble and impede normal traffic sing

ing and parading with placards, failed to disperse upon

lawful orders of police officers, all of which tended

directly to violence and breach of the peace in view of

existing conditions” (E. 2, 3, 157, 226). (Emphasis

added.)

To sustain conviction on such a charge the Constitution

requires proof of a substantial evil that rises far above

public inconvenience, annoyance and unrest and a clear

and present danger that that evil will occur, Cantwell v.

12

Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 311. The Supreme Court of

South Carolina equated this constitutional standard with

the offense charged, infra pp. 10a, 11a. These warrants

charge petitioners with conduct which “ tended directly to

immediate violence and breach of the peace” , and, there

fore, they cannot be convicted on proof of less.

This record is, however, without proof of violence or

threatened violence on the part of either the petitioners or

the onlookers to their demonstration. The very most that

may be said of petitioners’ conduct is that they sang the

“ Star Spangled Banner,” “America” and religious hymns

loudly, though not in a contemptuous manner (R, 39) and

stomped their feet when told to disperse. There is no

testimony of any kind that any of the demonstrators or the

onlookers made any remark or action or, indeed, gesture

which could be considered a prelude to violence. Those who

watched the demonstration appear to have been curious

and nothing more.

When asked why he thought there was a possiblity of

violence, the City Manager who ordered the arrests, testi

fied he noticed some “ possible troublemakers” among the

bystanders (R. 33-36). But these “possible troublemakers” ,

who were not identified, did nothing, said nothing and moved

on when so requested by the police (R. 33-36, 38, 54, 175).

Petitioners cannot be convicted on the totally unsubstanti

ated opinion of the police of possible disorder. Garner v.

Louisiana, 7 L. ed. 2d 207. Cf. Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S.

496, 516. Compared to the body contact and threats in

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, 317, 318; the riotous

circumstances of Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, 3 and

the mob action in Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877 (8th

Cir. 1947) cert, denied 332 U. S. 851, this record hardly indi

cates even a remote threat to public order.

13

Although the police testified that petitioners’ demonstra

tion was stopped because the situation had become “poten

tially dangerous” and not because of traffic problems (R.

16-17, 46, 53, 100-101, 186), and petitioners were charged

with conduct which “ tended directly to immediate violence

and breach of the peace” , the Supreme Court of South Caro

lina considered interference with traffic as an element of

petitioners’ offense, infra p. 15a. Even if causing inter

ference with traffic alone could uphold these convictions, the

conclusory language of the Supreme Court of South Caro

lina concerning “impeding traffic” does not bear analysis.

The City Manager and various police officers testified

that vehicular traffic was slowed on the city street in front

of the State House Building by those attracted by the dem

onstration; that the lanes leading to the dead-end parking

area directly in front of the legislative building were occa

sionally obstructed; that the sidewalk near the horseshoe

area (and part of the State House grounds) where the

demonstration took place was crowded; and that the side

walk on the other side of the city street from the horseshoe

was crowded with onlookers. On the uncontradicted testi

mony of the City Manager and the police officers, however,

no one attempted to use the lanes leading to the parking

area (R. 119, 123) ; while vehicular traffic on the city street

was slowed, a police officer was dispatched and kept it mov

ing (R. 45, 48); and the curious who had congregated to

watch the demonstration moved on promptly when re

quested by the police (R. 38). Passage of pedestrians was

not blocked on any sidewalk (R. 48, 52, 195). The police

were in complete control of any traffic problems (R. 34, 48,

168, 22).

These facts do not permit an inference of violence or

threatened violence. Petitioners were not charged with

obstructing traffic (although there is a specific South Caro-

14

lina statute prohibiting obstruction of traffic on the State

House Grounds, §1-417, Cumulative Supplement, 1952 Code

of Laws, see infra p. 12a (E. 54)) but rather with conduct

which “tended directly to immediate violence and breach

of the peace.” Without evidence of verbal threats, dis

obedience of police orders to move on, surging and milling

or body contact, any conclusion that a group of bystanders,

observing a demonstration in front of the State House

would turn immediately violent, while at least 30 policemen

were in attendance, is purely speculative.

Nor can a conclusion that petitioners’ demonstration

caused some slowing of vehicular and pedestrian traffic in

and of itself be used to uphold these convictions. Peti

tioners were charged with the broad offense of common

law breach of the peace. The Supreme Court of South

Carolina adopted the general definition of breach of the

peace found in 8 Am. Jur. 834, infra p. 14a, which definition

extends to an act “ of violence or an act likely to produce

violence.” Neither the general definition quoted by the

Supreme Court of South Carolina or the remainder of the

section on Breach of the Peace, 8 Am. Jur. 835, 836, 837,

delineates as breach of the peace, the holding of a non

violent demonstration which causes slower traffic on streets

and sidewalks. Petitioners have been unable to locate any

South Carolina decision applying breach of the peace to

any such situation or related situation.1 In this regard, Mr.

Justice Harlan’s words in Garner v. Louisiana, supra at

p. 236, are here relevant:

1 Compare the South Carolina cases cited by the Supreme Court

of South Carolina, infra p. 14a, all but one of which deal with

repossessing goods sold on the installment plan. State v. Langston,

195 S. C. 190, 11 S. E. (2d) 1, the other case, upheld the con

viction of a Jehovah’s Witness who played phonograph records on

the porches of private homes and used a soundtruek.

15

“But when a State seeks to subject to criminal sanc

tions conduct which, except for a demonstrated para

mount state interest, would be within the range of

freedom of expression as assured by the Fourteenth

Amendment, it cannot do so by means of a general and

all-inclusive breach of the peace prohibition. It must

bring the activity sought to he proscribed within the

ambit of a statute or clause ‘narrowly drawn to define

and punish specific conduct as constituting a clear and

present danger to a substantial interest of the State.’ ”

To convict petitioners because a byproduct of their expres

sion was interference with traffic would be to open South

Carolina’s use of common law breach of the peace to the

vice of vagueness. Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296,

307, 308. ;

One of the purposes of rights of freedom of speech, as

sembly and petition for redress of grievances is to influence

public opinion and persuade others to one’s own point of

view. De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353, 365; Sellers v.

Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877, 881 (8th Cir. 1947) cert, denied

332 U. S. 851; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 310;

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357, 375 (Mr. Justice

Brandeis concurring). Cf. Rockwell v. Morris, 10 N. Y. 721

(1960) cert, denied 7 L. ed. 2d 131. The exercise of these

rights on controversial issues will inevitably lead to situa

tions where numbers of persons hostile to the views ex

pressed are in attendance. If it were otherwise, the salutory

function of these rights would be lost and, ironically, suc

cessful attraction of others to hear and see your views

would result in the denial of the right to express those

views. To allow the police to use the very fact that there

are other persons besides the demonstrators in attendance

as the basis for a conclusion as to the likelihood of violence

would be to subject these rights “ to arbitrary suppression

of free expression.” Hague v. C. I. O., supra at 516.

16

II

Petitioners’ convictions were obtained in violation o f

their rights to freedom o f speech, assembly and peti

tion for redress o f grievances in that they were con

victed because their protected expression allegedly

tended to lead to violence and breach o f the peace on

the part o f others.

Mr. Justice Brandeis has written, Whitney v. California,

274 U. S. 357, 378, concurring opinion, that:

“ • . . the fact that speech is likely to result in some

violence or in destruction of property is not enough

to justify its suppression. There must be the prob

ability of serious injury to the State. Among free men,

the deterrents ordinarily to be applied to prevent crime

are education and punishment for violations of the

law, not abridgement of the rights of free speech and

assembly.”

Petitioners demonstrated their desire for reform of the

racially discriminatory policies of the State of South Oarer-

lina on the .gtoundsu3Lthe_Sj^te^egMatiWBHiiattignvMle-

the Legislature of the State of South Carolina was in ses

sion. It would be difficult to conceive of a more appro

priate time and place to exercise the rights of freedom of

expression. Cf. Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496, 515; United

States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542.

Petitioners have argued that this record is barren of any

evidence of conduct which was violent or threatened dis

order. But even if this Court should hold that the evidence

is adequate to avoid the rule of Thompson v. Louisville,

supra, and Garner v. Louisiana, supra, such a determination

still does not overcome the flaw in the convictions here.

For these convictions were sustained below on the ground

17

that petitioners’ conduct threatened violence and breach of

the peace on the part of those who observed the demonstra

tion, In the circumstances of this case, however, the duty

of the police was to protect petitioners from the unlawful

conduct of others, not to silence freedom of expression.

This is especially true when the disorder is not actual and

imminent but (as testified by the officers) “possible”, and

where, as here, large numbers of policemen are present

and in control of the situation. Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S.

at 516; Sellers v. Johnson, 163 F. 2d 877, 881 cert, denied

332 U. S. 851. Cf. Robeson v. Fanelli, 94 F. Supp. 62, 69,

70 (S. D. N. Y. 1950).

If this is the duty of the police when there are potential

threats of violence it must a fortiori be the duty of the

police when traffic adjustment is involved. The minor in

conveniences necessitated by traffic control and asking by

standers to move on cannot be enlarged into a justification

for abridging the freedoms of expression so fundamental

to the health of the democratic process. Petitioners have

not been convicted pursuant to a statute evincing a legisla

tive judgment that their expression should he limited in

the interests of some other societal value, but under a

generalized conception of common law breach of the peace.

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. at 307. Here as in the

Cantwell case, there has been no such specific declaration

of state policy which “would weigh heavily in any challenge

of the law as infringing constitutional limitations” (310

U. S. at 308). Petitioners were not charged with violating

§1-417, Cum. Supp. 1952 Code of Laws of South Carolina,

in which the Legislature did address itself to the problem

of traffic control in the State House area.2 In the absence

2 §1-417 provides as follows:

“ It shall be unlawful for any person:

1. Except State officers and employees and persons having

lawful business in the buildings, to use any of the driveways,

18

of a state statute, narrowly drawn, South Carolina cannot

punish expression which only leads to minor interference

with traffic. Petitioners’ “ communication, considered in the

light of the constitutional guarantees, raised no such clear

and present menace to public peace and order as to render

[them] liable to conviction of the common law offense in

question” Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 311; cf.

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88,105,106. See Statement,

supra, p. 7.

This Court has found the interests of the State insuffi

cient to justify restriction of freedom of speech and assem

bly in circumstances far more incendiary than these. Ter-

miniello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1; Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S.

496; Runs v. New York, 340 U. S. 290. Cf. Sellers v. John

son, 163 F. 2d 877 (8th Cir. 1947) cert, denied 332 U. S.

851; Rockwell v. Morris, 10 N. Y. 721 (1961) cert, denied

7 L. ed. 2d 131. In this case there is no indication of immi

nent violence as in Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, 318,

where a “pushing, milling and shoving crowd” was “moving

forward.”

The right to assemble peacefully to express views on

issues of public importance must encompass security

against being assaulted for having exercised it. Otherwise,

the exercise of First and Fourteenth Amendment freedoms

would be contingent upon the unlawful conduct of those * 2

alleys or parking spaces upon any of the property of the

State, bounded by Assembly, Gervais, Bull and Pendleton

Streets in Columbia upon any regular weekday, Saturdays and

holidays excepted, between the hours of 8 :30 A.M., and 5 :30

P.M., whenever the buildings are open for business; or

2. To park any vehicle except in spaces and manner marked

and designated by the State Budget and Control Board, in

cooperation with the Highway Department, or to block or

impede traffic through the alleys and driveways.”

19

opposed to the views expressed.3 Such a result would only

serve to provoke threats of unlawful and violent opposition

as a convenient method to silence minority expression. Such

a result should not be sanctioned when important consti

tutional rights are at stake. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S.

1, 14; Termmiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1; Sellers v. John

son, supra; Rockwell v. Morris, supra. “ Carried to its

logical conclusion, th[is] rule would result in civil authori

ties suppressing lawlessness by compelling the surrender

of the intended victims of lawlessness. The banks could

be closed and emptied of their cash to prevent bank rob

beries; the post office locked to prevent the mails being

robbed; the citizens kept off the streets to prevent holdups;

and a person accused of murder could be properly sur

rendered to the mob which threatened to attack the jail in

which he was confined.” Strutwear Knitting Co. v. Olsen,

13 F. Supp. 384, 391 (D. C. Minn. 1936).

3 See Beatty v. Gillhanks (1882) L. R. 9 Q. B. Div. (Eng)

holding street paraders not guilty of breach of the peace for

parade they knew would cause violent opposition.

20

CONCLUSION

W herefore , f o r the fo re g o in g reason s, it is re sp e ctfu lly

subm itted that the p e tition f o r w r it o f ce r t io ra r i sh ou ld he

gran ted .

R e sp e c tfu lly subm itted ,

J ack G reenberg

Constance B ak er M otley

J am es M . N abrit , I I I

M ic h ael M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

M a t t h e w J . P erry

L in co ln C. J e n k in s , J r .

1107% Washington Street

Columbia 1, South Carolina

D onald J am es S am pson

Greenville, South Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

I n t h e R ich lan d Co u n ty C ourt

T h e S tate

-v.-

J am es .E dwards, Jr., et at.

ORDER

This is an appeal from conviction in magistrate’s court

of the common law crime of breach of the peace. There

are almost 200 appellants, who were convicted by the

^magistrate, City of Columbia, Richland County, in four

trials, trial by jury having been waived by the appellants

in each case. By stipulation between counsel for the ap

pellants and the counsel for the State, the appeals will be

treated here as one since the facts and applicable law

were substantially the same in each case. The trial Magis

trate imposed fines upon each of the appellants ranging

from $10.00 to $100.00. Due and timely notice of appeal

from conviction was served and oral arguments were heard

before me in open court. At mv suggestion and with the

agreement of counsel for both sides, written briefs were

filed.

The appellants except to the finding of the Magis

trate’s Court and the fines imposed as a result of such

finding of guilt upon the grounds that the State by the

evidence failed to establish the corpus delicti, that the

State failed to prove a prima facie ease, that the evidence

showed that the police powers of the State of South Caro

lina were used against the appellants to deprive them of

2a

the right of freedom of speech guaranteed by the Consti

tution of the United States and the Constitution of South

Carolina, and that the evidence presented before the Magis

trate showed only that the appellants at the time of their

arrests were engaged in a peaceful and lawful assemblage

of persons, orderly in every respect upon the public streets

of the State of South Carolina.

Testimony before the Magistrate sets out the following

series of events which culminated in the arrest of the

appellants and the issuance of warrants charging them

with breach of the peace. Shortly before noon on the third

day of March, 1961, the appellants, acting in concert and

with what appeared to be a preconceived and definite plan,

proceeded on foot along public sidewalks from Zion Baptist

Church in the City of Columbia to the State House grounds,

a distance of approximately six city blocks. They wrnlked

in groups of twelve to fifteen each, the groups being sepa

rated by a few feet, Testimony shows that the purpose of

this assemblage and movement of students was to walk

in and about the grounds of the State House protesting,

partly by the use of numerous placards, against the segre

gation laws of this State. The General Assembly was in

session at the time.

Upon their approach to an area in front of and im

mediately adjacent to the State House building, known

as the “horseshoe” , the Negro students were met by police

authorities of the State and the City of Columbia. After

brief conversation between the leader of the students and

police officers, the students proceeded to walk in and about

the State House grounds displaying placards, some of

which, at least, might be termed inflammatory in nature.

There is some evidence also that a few groups of students

were singing during this period. Such activity continued

Order

3a

for approximately 45 minutes during which the students

met with no interference from anyone. Testimony from

city and state authorities wras to the effect that during

this period of time, while the students were marching in

and about the grounds without hindrance from officers,

large numbers of onlookers, evidently attracted by the

activity of the students, had gathered in the “horseshoe”

area, entirely blocking the vehicular traffic lane and inter

fering materially with the movement of pedestrian traffic

on the sidewalks in the area and on city sidewalks im

mediately adjacent. Testimony of city and state authorities

was that vehicular traffic on the busy downtown streets of

Gervais and Main, one running alongside the grounds and

the other “dead-ending” at the State House, was noticeably

and adversely affected by the large assemblage of students

and onlookers which had filled the “horseshoe” area and

overflowed into Gervais and Main Streets. Some testi

mony disclosed that in and about the “horseshoe” area it

was necessary for the police to issue increasingly frequent

orders to keep pedestrian traffic moving, even at a slow

rate.

The Chief of Police of the City of Columbia and the

City Manager of the City of Columbia testified that they

recognized in the crowd of onlookers persons whom they

knew to be potential troublemakers. It was at this time

that the police authorities decided that the situation had

become potentially dangerous and that the activities of

the students should be stopped. The recognized and ad

mitted leader of the students was approached by city au

thorities and informed that the activities of the students

had created a situation which in the opinion of the officers

was potentially dangerous and that such activities should

cease in the interest of the public peace and safety. The

Order

4a

students were told through their leader that they must

disperse in 15 minutes. The leader of the students, ac

companied by the City Manager of Columbia, went from

one group of students to the other, informing them of the

decision and orders of the police authorities.

The City Manager testified that the leader of the students

refused to instruct or advise them to desist and disperse

but that instead he “harangued” the students, whipping

them into what was described by the City Manager as a

semi-religious fervor. He testified that the students, in

response to the so-called harangue by their leader, began

to sing, clap their hands and stamp their feet, refusing to

stop the activity in which they were engaged and refusing

to disperse. After 15 minutes of this activity the students

were arrested by state and city officers and were charged

with the crime of breach of the peace.

With regard to the position taken by the appellants

that their activities in the circumstances set forth did

not constitute a crime, the attention of the Court has been

directed to several of our South Carolina eases upon this

point, one of them being the case of State v. Langston,

195 S. C. 190, 11 S. E. (2d) 1. The defendant in that case

was a member of a religious sect known as Jehovah’s Wit

nesses. He, with others, went on a Sunday to the homes of

other persons in the community and played records on

the porches announcing his religious beliefs to anyone who

would listen. He also employed a loud speaker mounted on

a motor vehicle to go about the streets for the same pur

pose. Crowds of persons were attracted by this activity.

No violence of any kind occurred. Upon his refusal to

obey orders of police officers to cease such activity, the

defendant was arrested and convicted for breach of the

peace. The Court in upholding the conviction said:

Order

5a

“It certainly cannot be said that there is not in this

State an absolute freedom of religion. A man may

believe what kind of religion he pleases or no religion,

and as long as he practices his belief without a breach

of the peace, he will not be disturbed.

“ In general terms, a breach of the peace is a viola

tion of public order, the disturbance of public tran

quility, by any act or conduct inciting to violence.

“It is not necessary that the peace be actually

broken to lay the foundation of prosecution for this

offense. If what is done is unjustifiable, tending with

sufficient directness to break the peace, no more is

required.”

With further reference to the argument advanced by the

appellants that they had a constitutional right to engage

in the activities for which they were eventually charged

with the crime of breach of the peace, regardless of the situ

ation which was apparently created as a result of such

activities, this Court takes notice of the New York State

case of People v. Feiner, 300 N. Y. 391, 91 N. E. (2d) 319.

In that case the Court of Appeals of the State of New York

wrote an exhaustive opinion in a case which arose in that

State in 1950, the factual situation being similar in many

respects to the cases presently before this Court upon ap

peal.

Feiner, a University student, stationed himself upon one

of the city streets of the City of Syracuse and proceeded

to address his remarks to all those who would listen. The

general tenor of his talk was designed to arouse Negro

people to fight for equal rights, which he told them they

did not have. Crowds attracted by Feiner began to fill up

the sidewalks and overflow into the street. There was no

Order

6a

disorder, but in the opinion of police authorities there was

real danger of a disturbance of public order or breach of

the peace. Feiner was requested by police to desist. He

refused. The arrest was then made and Feiner was charged

and convicted of disorderly conduct.

In upholding the conviction, the New York Court quoting

from Cantwell v. State of Connecticut, 310 TJ. S. 296, 60

S. Ct. 900, 84 L. Ed. 1213, 128 A. L. B. 1352, said:

“ The offense known as breach of the peace embraces

a great variety of conduct destroying or menacing

public order and tranquility. It includes not only vio

lent acts, but acts and words likely to produce violence

in others. No one would have the hardihood to suggest

that the principle of freedom of speech sanctions incite

ment to riot or that religious liberty connotes the privi

lege to exhort others to physical attack upon those be

longing to another sect. When clear and present danger

of riot, disorder, interference with traffic upon the

public streets or other immediate threat to public

safety, peace or order appears, the power of the State

to prevent or punish is obvious.”

The appellants in the present case have emphasized re

peatedly in the trials and in their arguments before the

Court and in their Brief that no one of them individually

committed any single act which was a violation of law.

It is their contention that they had a right to assemble and

act as they did so long as they did no other act which was

in itself unlawful. Apparently they reject the proposition

that an act which is lawful in some circumstances might be

unlawful in others. The New York Court in answering a

similar contention made by the defendant in the Feiner

case said:

Order

7a

“W e are well aware of the caution with which the

courts should proceed in these matters. The intolerance

of a hostile audience may not in the name of order be

permitted to silence unpopular opinions. The Consti

tution does not discriminate between those whose ideas

are popular and those whose beliefs arouse opposition

or dislike or hatred—guaranteeing the right of free

dom of speech to the former and withholding it from

the latter. We recognize, however, that the State must

protect and preserve its existence and unfortunate

as it may be, the hostility and intolerance of street

audiences and the substantive evils which may follow

therefrom are practical facts of which the Courts and

the law enforcement officers of the State must take

notice. Where, as here, we have a combination of an

aroused audience divided into hostile camps, an inter

ference with traffic and a speaker who is deliberately

agitating and goading the crowd and the police officers

to action, we think a proper case has been made out

under our State and Federal Constitutions for punish

ment.”

In the present case the appellants were not prevented

from engaging in their demonstration for a period of ap

proximately an hour, nor were they hindered in any way.

After such activity had gone on for approximately 45

minutes, police officers saw that streets and sidewalks had

been blocked by a combination of students and a crowd of

200 or 300 onlookers which had been attracted by their

activities. They recognized potential troublemakers in the

crowd of onlookers which was increasing by the minute.

State and city authorities testified that in their opinions

the situation which had been created by the students had

Order

8a

reached a point where it was potentially dangerous to the

peace of the community. Instead of taking precipitous

action even at this point, police authorities ordered the

students to cease their activities and disperse, giving them

the reasons for such order. The students were told that

they must cease their activities in 15 minutes. The students

refused to desist or to disperse. There is no indication

whatever in this ease that the acts of the police officers

were taken as a subterfuge or excuse for the suppression

of the appellants’ views and opinions. The evidence is clear

that the officers were motivated solely by a proper concern

for the preservation of order and the protection of the

general welfare in the face of an actual interference with

traffic and an imminently threatened disturbance of the

peace of the community.

Petitioning through the orderly procedures of the Courts

for the protection of any rights, either invaded or denied,

has been followed by the American people for many years.

It is the proper and the correct course to pursue if one is

sincerely seeking relief from oppression or denial of rights.

While it is a constitutional right to assemble in a hall to

espouse any cause, no person has a right to organize demon

strations which any ordinary and reasonable thinking citi

zen knows or reasonably should know would stir up passions

and create incidents of disorder.

The State of South Carolina, the City of Columbia, and

the County of Richland in the exercise of their general

police powers of necessity have the authority to act in

situations such as are detailed in the evidence in these cases

and if the conduct of their duly appointed officers of the

law is not arbitrary, capricious and the result of prejudice

but is founded upon clear, convincing and common sense

reasoning, there is no denial of any right.

Order

9a

All exceptions of tlie appellants are overruled and the

convictions and sentences are affirmed.

/ s / L egare B ates,

Senior Judge, Richland County

Court.

Order|

Columbia, South Carolina,

July 10th, 1961.

10a

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA

I n T h e S u prem e C ourt

T h e S tate ,

—v.—

J am es E dwards, J r ., et al.,

Respondent,

Appellants.

A P PE A L P R O M R IC H L A N D C O U N T Y , LEGARE B ATES, C O U N T Y JU D G E

A ffirm ed

L ew is , A.J.:

The appellants, one hundred eighty seven in number,

were convicted in the Magistrate’s Court of the common

law crime of breach of the peace. The charges arose out

of certain activities in which the appellants were engaged

in and about the State House grounds in the City of

Columbia on March 2, 1961. The only question involved

in their appeal to this Court is whether or not the evidence

presented to the trial Court was sufficient to sustain their

conviction. Conviction was sustained by the Richland

County Court, from which this appeal comes. While the

appellants have argued that their arrest and conviction

deprived them of their constitutional rights of freedom of

speech and assembly, guaranteed to them by both the

State and Federal Constitutions, it is conceded in argu

ment before us that whether or not any constitutional right

was denied to them is dependent upon their guilt or in

nocence of the crime charged under the facts presented

11a

to the trial Court. If their acts constituted a breach of the

peace, the power of the State to punish is obvious. Feiner

v. New York, 71 S. Ct. 303, 340 IT. S. 315, 95 L. Ed. 295.

It is well settled that the trial Court must be affirmed

if there is any competent evidence to sustain the charges

and, in determining such question, the evidence and the

reasonable inferences to be drawn therefrom must be

viewed in the light most favorable to the State.

The testimony discloses the following events which re

sulted in the arrest of the appellants and the issuance of

warrants charging them with breach of the peace.

Shortly before noon on March 2, 1961, a group of ap

proximately 200 Negro students, after attending a meet

ing at the Zion Baptist Church in the City of Columbia,

walked in groups of approximately fifteen each from the

church along public sidewalks to the State House grounds,

a distance of approximately six blocks. The purpose of

the movement of the group to the State House was to

parade about the grounds in protest to the General As

sembly and the general public against the laws and cus

toms of the State relative to segregation of the races,

such demonstration to continue until, as the testimony

shows, their conscience told them that the demonstration

had lasted long enough. The General Assembly was in

session at the time.

As they reached the State House grounds, the group

was met by police authorities of the State and the City

of Columbia. After a brief conference between their leader

and police officers, the group proceeded to parade about

the State House grounds. They continued to parade around

the State House for approximately forty-five minutes

during which time they met with no interference. Dur

ing this forty-five minute period a crowd, evidently at-

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

12a

tracted by the activities of the paraders, began gathering

in the area in front of the State House, known as the

“horseshoe”, blocking the lanes for vehicular traffic through

such area and materially interfering with the movement of

pedestrian traffic on the sidewalks in the area and on side

walks immediately adjacent. Vehicular traffic on the ad

jacent city streets was noticeably and adversely affected by

the large assemblage of paraders and the crowd which had

overflowed the horseshoe area into the adjacent streets.

The traffic situation can best be understood in relation

to the area involved. Columbia is the State Capitol. Main

and Gervais Streets in Columbia intersect in front of the

State House. Gervais Street runs in an east-west direc

tion, along the northern side of the State House grounds.

Main Street, running north and south, intersects Gervais

Street in front of the State House, where it dead-ends. The

area referred to as the “horseshoe” is in effect a continua

tion of Main Street into the State House grounds. It is

about % block in length and about the width of Main

Street. Situated at the center of the entrance to the “horse

shoe” is a monument, with space on each side for vehicular

traffic to enter and leave the area. It is reserved for park

ing of vehicles and, on the occasion in question, was filled

with automobiles. It is a violation of law to block or im

pede traffic in the area. Section 1-417, Cumulative Supple

ment, 1952 Code of Laws. Sidewalks are located around

the area for use by pedestrians.

The intersection of Main and Gervais Streets in front

of the State House in Columbia is, by common knowledge,

one of the busiest intersections in the State of South Caro

lina, both from the standpoint of vehicular and pedestrian

traffic.

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

13a

On the occasion in question, in addition to the approxi

mately 200 paraders in the area, there had gathered ap

proximately 350 onlookers and the crowd was increasing.

With the paraders and the increasingly large number of

onlookers congregated in the above area seriously affect

ing the flow of pedestrian and vehicular traffic, the officers

approached the admitted leader of the paraders and in

formed him that the situation had reached the point where

the activities of the group should cease. They were told

through their leader that they must disperse within fifteen

minutes. The parade leader, accompanied by the police

authorities, went among the paraders and informed them

of the decision and orders of the police. The leader of the

group refused to instruct or advise them to disperse but

instead began a fervent speech to the group and in re

sponse they began to sing, shout, clap their hands and

stamp their feet, refusing to disperse. After about fifteen

minutes of this noisy demonstration, the appellants, who

were engaging in the demonstration, were arrested by

State and City officers and charged with the crime of

breach of the peace. Upon the trial, all of the appellants

were identified as participants in the parade and activities

out of which the charge arose.

The warrants issued against appellants charge that they

“ on March 2, 1961, on the State Capitol grounds, on ad

jacent sidewalks and streets, did commit a breach of the

peace in that they, together with a large group of people,

did assemble and impede the normal traffic, singing and

parading with placards, failed to disperse upon lawful

orders of police officers, all of which tended directly to

immediate violence and breach of the peace in view of

existing conditions.”

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

14a

“ Breach of the peace is a common law offense which is

not susceptible to exact definition. It is a generic term,

embracing ‘a great variety of conduct destroying or men

acing public order and tranquility’. Cantwell v. State of

Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 60 S. Ct. 900, 905, 84 L. Ed. 1213,

128 A. L. R. 1352.” State v. Randolph, 239 S. C. 79, 121

S. E. (2d) 349.

The general definition of the offense of breach of the

peace approved in our decisions is that found in 8 Am. Jur.

834, Section 3 as follows: “ In general terms, a breach of

the peace is a violation of public order, a disturbance of

the public tranquillity, by any act or conduct inciting to

violence . . . , it includes any violation of any law enacted

to preserve peace and good order. It may consist of an

act of violence or an act likely to produce violence. It

is not necessary that the peace be actually broken to lay

the foundation for a prosecution for this offense. If what

is done is unjustifiable and unlawful, tending with suffi

cient directness to break the peace, no more is required.

Nor is actual personal violence an essential element in

the offense. . . .

“By ‘peace,’ as used in the law in this connection, is

meant the tranquillity enjoyed by citizens of a municipality

or community where good order reigns among its mem

bers, which is the natural right of all persons in political

society.”

See: Soulios v. Mills Novelty Co., 198 S. C. 355, 17 S. E.

(2d) 869; State v. Langston, 195 S. C. 190, 11 S. E. (2d)

1; Childers v. Judson Mills Store, 189 S. C. 224, 200 S. E.

770; Webber v. Farmers Chevrolet Co., 186 S. C. I l l , 195

S. E. 139; Lyda v. Cooper, 169 S. C. 451, 169 S. E. 236.

In determining whether the acts of the appellants con

stituted a breach of the peace, we must keep in mind that

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

the right of the appellants to hold a parade to give expres

sion to their views is not in question. They were not ar

rested for merely holding a parade, nor were they arrested

for the views which they held and were giving expression.

Eather, appellants were arrested because the police au

thorities concluded that a breach of the peace had been

committed.

The parade was conducted upon the State House grounds

for approximately forty-five minutes. It was not until

the appellants and the crowd, attracted by their activities,

were impeding vehicular and pedestrian traffic upon the ad

jacent streets and sidewalks that the officers intervened in

the interest of public order to stop the activities of the ap

pellants at the time and place. Notice was given to appel

lants by the officers that the situation had reached the point

where they must cease their demonstration. They were

given fifteen minutes in which to disperse. The orders of

the police officers under all of the facts and circumstances

were reasonable and motivated solely by a proper concern

for the preservation of order and prevention of further

interference with traffic upon the public streets and side

walks. The appellants not only refused to heed and obey

the reasonable orders of the police, but engaged in a fiftten

minute noisy demonstration in defiance of such orders.

The acts of the appellants under all the facts and circum

stances clearly constituted a breach of the peace.

Affirmed.

T aylor , C . J O xn eb , L egge and Moss, JJ., concur.

Opinion of the Supreme Court of South Carolina

16a

Denial of Petition for Rehearing

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA

T h e S tate ,

—against—

Respondent,

J am es E dwards, J r ., et al.,

Appellants.

CERTIFICATE

I, Harold R. Boulware, hereby certify that I am a prac

ticing attorney of this Court and am in no way connected

with the within case. I further certify that I am familiar

with the record of this case and have read the opinion of

this Court which was filed December 5, 1961, and in my

opinion there is merit in the Petition for Rehearing.

/&/ H arold R. B oulw are

Harold R. Boulware

Columbia, South Carolina

December 13,1961

(Indorsed on back of this document):

Petition denied.

s / C. A. T aylor

s / G. D ew ey O xner

s / L ionel K . L egge

s / J oseph R . M oss

s / J . W oodrow L ew is

%