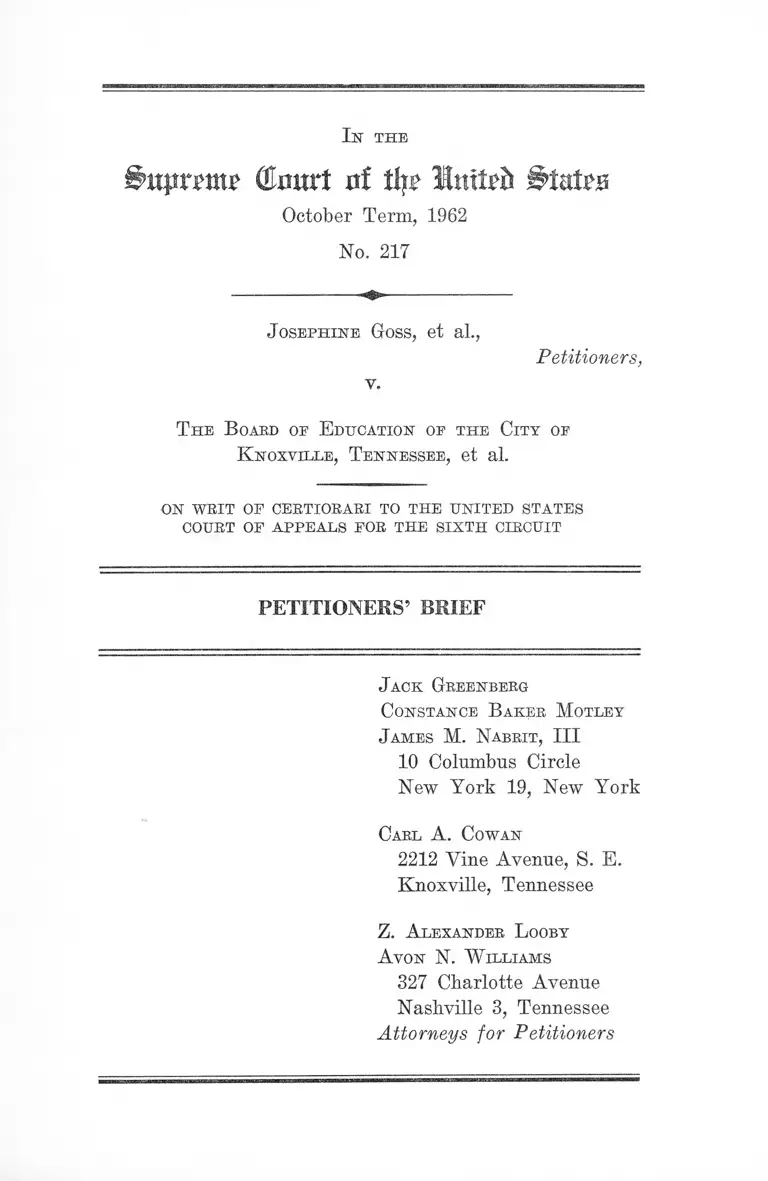

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Petitioners' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Petitioners' Brief, 1962. e37b8bea-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a6516cb3-4942-4b8a-8a5f-9f89e6d9a5a2/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-petitioners-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Bnpvmt Ghmrt ni tfy> In tt^ States

October Term, 1962

No. 217

I n the

J o s e p h in e G o ss, e t a l.,

y.

Petitioners,

T h e B oabd oe E ducation op t h e C it y oe

K n o x v il l e , T e n n e s s e e , e t a l.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E U N ITED STA TES

COURT OF A PPEA LS FOR TH E S IX T H CIRCUIT

PETITION ERS’ BR IE F

J a ck G r e e n b e r g

C o n sta n ce B a k e r M o t l e y

J a m es M. N a b r it , I I I

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

C arl A . C owan

2212 Vine Avenue, S. E.

Knoxville, Tennessee

Z. A lex a n d er L ooby

A von N. W il l ia m s

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

Attorneys fo r Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below ................................................................ 1

Jurisdiction ........................................................ 2

Question Presented ............................................................ 2

Constitutional Provision Involved.... ............................ 2

Statement .................... ......................... ~............. ................ 3

Evidence and Holdings: .......... 6

Goss Case ................................................................ 6

Maxwell Case ..................................... 10

Argument ......................................................... -................... 11

C o n clu sio n .......... 22

T a ble oe C a ses

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ..... ................... ........... 22

Boson v. Hippy, 285 P. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) .... .....16,17,18

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955) 18

Browder v. Gayle, 142 P. Supp. 707 (Mi D. Ala.

1956), aff’d 352 U. S. 903 ___ _____ _______- - ..... 15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .. 3,11,

13,18

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294

(1955) .......................... ............. .......... ............ -3 ,1 1 ,1 2 ,1 6 ,1 9

Brunson v. Board of Trustees of School District

No. 1 of Clarendon County, S. C. (4th Cir., No.

8727, Dec. 7, 1962) --- --------- --------- ---------------- --- 15

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(5th Cir. 1962) .....................~~---- ---------- --------....... 12

11 IN D EX

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956) .... 20

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 .................................. — 11,18

Dillard v. School Board of City of Charlottesville,

not yet reported (4th Cir., No. 8638, Sept. 17, 1962) 16,17

Goss v. Board of Education, 301 F. 2d 164 (6th Cir.

1962) ........ .................. .......... ............. .............................. 17,18

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, 304

F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) .........................................12,16, 20

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, 201

F. Supp. 620 (W. D. Va. 1962), rev’d in part on

other grounds, not yet reported (4th Cir., No. 8722,

Sept. 28, 1962) ........................................-.....-............ ... 16

Jackson v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg,

203 F. Supp. 701 (W. D. Va. 1962) .......................... 17

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria,

278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ....................................... - 12

Kelley v. Board of Education of the City of Nash

ville, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959) ........................9,17,18

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d

370 (5th Cir. 1960) ....................................................... 20

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga,

Tenn., 203 F. Supp. 843 (E. D. Tenn. 1962) ............ 17

Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County,

Va., 305 F. 2d 94 (4th Cir. 1962) .............................. 12, 20

Maxwell v. County Board of Education, 301 F. 2d

828 (6th Cir. 1962) ......................................................... 17

Northcross v. Bd. of Education of City of Memphis,

302 F.2,1 819 (6th Cir. 1962) ___ _______________ 12

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) .... 12, 20

PAGE

Roy v. Brittain, 297 S. W. 2d 72 (Tenn. 1956) 13

IN D EX 111

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ...... ..........- ......—.......- 16

Shuttlesworth v. Board of Education, 162 F. Supp.

372 (N. D. Ala. 1958), aff’d on limited grounds,

358 U. S. 101 ....................... ............................................ 20

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 — ............ 16

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 .................. .................. 16

Taylor v. Board of Education of the City of New

Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181 (S. D. N. Y. 1961), ap

peal dismissed, 288 F. 2d 600 (2nd Cir. 1961);

195 F. Supp. 231 (S. D. N. Y. 1961); aff’d 294 F. 2d

36 (2nd Cir. 1961), cert, den., 368 IT. S. 940 ............ 20

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County, 204 F. Supp. 620 (E. D. Va. 1962) ......... 17

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S.

173 ...................................................................................... 19

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, not

yet reported (4th Cir., No. 8643, Oct. 12, 1962) ..12,15, 21

Statutes and Other Authorities:

28 U. S. C. § 1254(1) ......................................................... 2

28 U. S. C. §§ 1331, 1343, 2201 and 2202 ........... 3

42 U. S. C. %% 1981 and 1983 .............................. 3

F. R. C. P., Rule 23(a)(3) ............................................... 3

Tennessee Code of 1955, §§ 49-3701 to 49-3703 .......... 13

Tennessee Constitution of 1870, art. 11, sec. 12 .......... 13

Black, “The Lawfulness of the Segregation Deci

sions,” 69 Yale L. J . 421 (1960) ......... ...................... 21

PAGE

I n t h e

j ^ u p r m p C o u r t o f t l j r I n t t r t J 0 t a t r u

October Term, 1962

No. 217

J o s e p h i n e G o s s , et a l . ,

v.

Petitioners,

T h e B oard oe E ducation oe t h e C it y oe

K n o x v il l e , T e n n e s s e e , e t a l.

ON W RIT OP CERTIORARI TO TH E U N ITED STA TES

COURT OF A PPEA LS FOR TH E SIX T H CIRCUIT

PETITION ERS’ BR IEF

Opinions Below

1. Goss case. The memorandum opinion of the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee

(R. 119) is reported at 186 F. Supp. 559. The opinion of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

(R. 157) is reported in 301 F. 2d 164 (6th Cir. 1962).

2. Maxwell case. The first Findings of Fact, Conclu

sions of Law and Judgment of the United States District

■ Court for the Middle District of Tennessee (R. 228) is re

ported at 203 F. Supp. 768. The second Findings of Fact,

Conclusions of Law and Judgment of that court (R. 269) is

unreported. The opinion of the United States Court of Ap-

2

peals for the Sixth Circuit (R. 282) is reported in 301 F. 2d

828 (6th Cir. 1962).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals in the Goss case

was entered on April 3, 1962 (R. 156). The judgment of

the Court of Appeals in the Maxwell case was entered on

April 4, 1962 (R. 281). The petition for certiorari was filed

June 29, 1962, and was granted October 8, 1962, limited

to Question 1 presented by the petition. The jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. § 1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether petitioners, Negro school children seeking de

segregation of the public school systems of Knoxville, Ten

nessee (Goss case), and Davidson County, Tennessee

(.Maxwell case), are deprived of rights under the Four

teenth Amendment by judicial approval of a provision in

desegregation plans adopted by their local school boards,

which expressly recognizes race as a ground for transfer

between schools in circumstances where such transfers

operate to preserve the pre-existing racially segregated

system, and which operate to restrict Negroes living in the

zones of all-Negro schools to such schools while permit

ting white children in such areas to transfer to other

schools solely on the basis of race.

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

3

Statement

These two cases involve the desegregation of the public

schools of the City of Knoxville, Tennessee, and of David

son County, Tennessee, an area adjacent to the City of

Nashville.

The cases were brought by Negro public school pupils

and their parents as class actions under Rule 23(a)(3),

F . R. C. P., against the local school authorities seeking in

junctive and declaratory relief to obtain desegregation in

accordance with Brown v. B oard o f Education, 347 U. S.

483; 349 U. S. 294.1 In each case, jurisdiction of the Dis

trict Court was invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C., §§ 1331,

1343, 2201 and 2202, and 42 U. S. C., §§ 1981 and 1983, the

cases involving alleged denials of rights under the Four

teenth Amendment. In both cases the school authorities

acknowledged by their answers that they were continuing

to operate racially segregated public school systems. After

directions from the trial courts to present desegregation

plans (R. 29, 208), both boards adopted plans to desegregate

one school grade each year over a twelve year period, be

ginning with the first grade, in 1960 in Knoxville and in

1961 in Davidson County. (For text of plans see: R. 30,

214.) While there were differences in wording, the two

plans were substantially the same. Both contained provi

sions for rezoning of schools without reference to race,

and for a system of transfers.

The transfer rule, which is at issue on this petition, pro

vided that pupils could obtain transfers from the schools

in their zones of residence to other schools upon request in

certain cases. The Knoxville plan provided:

1 The Goss case was filed December 11, 1959 in the District Court

for the Eastern District of Tennessee (R. 5). Maxwell was filed

September 19, 1960 in the Middle District of Tennessee (R. 165).

4

6. The following will be regarded as some of conditions

to support requests for transfer:

a. When a white student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school previously serving col

ored students only;

b. When a colored student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school previously serving white

students only;

c. When a student would otherwise be required to

attend a school where the majority of students of

that school or in his or her grade are of a different

rate (R. 31-32).

The transfer rule adopted by Davidson County was the

same except for one or two words not affecting the meaning,

e.g., in the introductory clause the words “valid conditions

for requesting transfer” are used instead of “valid condi

tions to support requests for transfer” as in the Goss case

(R. 214-215). Both plans also contained similar general

language that transfers would be granted when “good

cause” is shown.2

2 The Knoxville Plan provided (E. 3 1 ):

“5. Requests for transfer of students in desegregated grades

from the school of their Zone to another school will be given

full consideration and will be granted when made in writing

by parents or guardians or those acting in the position of

parents, when good cause therefor is shown and when transfer

is practicable, consistent with sound school administration.”

The Davidson County Plan provided (R. 214) :

“4. Application for transfer of first grade students, and sub

sequent grades according to the gradual plan, from the school

of their zone to another school will be given careful considera

tion and will be granted when made in writing by parents,

guardians, or those acting in the position of parents, when

good cause therefor is shown and when transfer is practicable

and consistent with sound school administration.”

5

Plaintiffs filed written objections to both plans including

specific objections to the above-quoted transfer rule (R.

32-34,. 215-219). The District Courts in both cases held

hearings to consider the adequacy of the plans at which the

parties presented evidence.

In the Goss case, the District Court found the plan ac

ceptable and approved it in all respects, except that it re

quired the school board to re-study and re-submit a plan

relating to an all-white vocational school offering technical

courses not available to Negro students. On plaintiffs’ ap

peal to the Sixth Circuit in the Goss case, the Court of Ap

peals modified this judgment “insofar as it approved the

board’s plan for continued segregation of all grades not

reached by its grade a year plan,” and remanded, instruct

ing the District Court “to require the board to promptly

submit an amended and realistic plan for the acceleration

of desegregation” (301 F. 2d at 169). Thus, the Court

sustained one of plaintiffs’ arguments saying the “evidence

does not indicate that the board is confronted with the type

of administrative problems contemplated by the Supreme

Court in the second Brown decision” (301 F. 2d at 167).

The court affirmed the approval of the plan as to the other

features, including the transfer provision, stating that this

approval was “subject to it being used for proper school

administrative purposes and not for perpetuation of seg

regation” (301 F. 2d at 168).

In the Maxwell case the District Court disapproved the

school board’s twelve year plan and modified it to require

that the first four grades be desegregated as of January 1,

1961, with an additional grade to be desegregated each

September thereafter until all grades were covered. The

District Court approved the racial transfer provision and

also refused injunctive relief to several plaintiffs who

sought admission to white schools nearer their homes as

6

exceptions to the plan in higher grades that were still seg

regated. On plaintiffs’ appeal involving these last men

tioned two issues, the Sixth Circuit affirmed the approval

of the transfer plan and the denial of injunctive relief as

to three plaintiffs who sought individual admissions.

Evidence and Holdings:

Goss Case

The major part of the testimony in the record relates to

the issue presented by the request for a twelve year delay

in desegregation, and since no review of the Sixth Circuit’s

action on this matter is sought, this factual summary is

limited to matters bearing on the transfer plan. The evi

dence touching on the transfer plan consisted of testimony

by school board members as to its meaning, their under

standing of its likely effect, and the reasons for the plan.

There was also testimony by a school administrator as to

prior transfer procedures, and several affidavits and ex

hibits were filed by plaintiffs in support of their motion

for new trial which reflect school board action establishing

transfer procedures after the trial court’s approval of the

plan.

The school board president, Dr. Burkhart, testified that

the provision for transfers based on race was adopted out

of concern for “the orderly education of our students, both

white and colored, in an effort to make available to the

community the best facilities and instructional facilities

that we can under the least possible circumstance which

might be harmful” (R. 85) ; that the board thought it

might be “harmful” to a certain number of white students

to go to school with Negroes and also “it might be harmful

to some of the colored students to go with white students

7

if they did not want to” (E. 85). He said the basis for

this feeling was:

The fact that we are talking about two separate races

of people, with different physical characteristics, who

have not in our community been very closely associated

in many ways, and certainly not in school ways. And

there would be a sudden throwing together of these

two races which are not accustomed to that sort of

thing. Either one of them might suffer from it unless

we took some steps to try to decrease that amount of

suffering or that contact which might lead to that in

case it did occur (E. 86).

The witness stated that he did not necessarily refer to

physical harm but was more concerned with “mental harm”

(E. 86). With regard to the expected operation of the

transfer rule, the school board president testified that he

did not know the mechanics as to how pupils would be

notified of their new school zones (E. 91-92). He further

testified:

Q. I am asking you do you or does the board antici

pate that any white students will remain in schools

which have been previously zoned or used for Negroes

exclusively! A. We doubt that they will.

Q. As a matter of fact, none have remained in the

City of Nashville, have they? A. I don’t know. All

I can do to keep up with the City of Knoxville.

Q. So then a Negro student who happens to be in a

zone where the school for his zone is a school which was

formerly used by Negroes only, that school will be

continued to be used for Negroes only and he will re

main in a segregated school, will he not? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And if he applied for transfer out of his zone to

a school which had been formerly serving white stu

dents only, then his application would be denied under

8

this plan, would it not, sir? A. Unless it were based

on one of the other reasons that we have established

for transfer. If transferred under one of those, it

would be granted.

# ̂ ^

Q. But a white student to transfer out of a Negro

school, as you have stated, would be entitled to do so,

to have his application granted as a matter of course

under paragraph 6, subparagraph “a” or “e” of this

plan? A. Yes, sir (R. 93-94).

Another board member, Dr. Moffett, acknowledged that

the transfer provisions “at least give the opportunity” to

perpetuate segregation insofar as they are availed of by

the students or parents (R. 108).

Mr. Marable, a school administrator in charge of handling

transfer requests, stated that under the system used before

this plan was approved, when parents request transfers he

investigates the requests and gets the views of the princi

pals concerned and determines if the family has a “valid

reason” (R. 115); that the school board “leaves that up

to me,” {Ib id . ) ; that he did not know what the board’s

written rules on transfer provided (R. 115-116); that “1

just know I have handled it so many years on my own,

and so far I haven’t stuck my neck out on it” (R. 116);

“that each case is individual. That has to be handled that

way. Could not have a rule” (R. 116); that an example of a

“valid” reason would be where a child’s mother taught at

a school and wanted the child with her because she had no

where to leave it and the school had room and the principal

agreed (R. 116-117); that generally transfers were granted

for “hardship cases and convenience” (R. 117).

After the trial court approved the plan, the school board

adopted a resolution providing for administration of the

9

provisions as follows: “All first grade pupils should either

enroll in the elementary school within their new school zone

or in the school which they would have previously attended”

(R. 141).

The District Court opinion did not discuss the transfer

plan issue in its memorandum opinion, although during the

trial the court indicated that it regarded itself as bound by

the Sixth Circuit’s prior approval of an almost identical

provision in the Nashville, Tennessee school case (R. 94).

See K elley v. Board o f Education o f Nashville, 270 F. 2d

209, 228 (6th Cir. 1959).

The Court of Appeals’ holding with respect to the transfer

plan in the Goss case was as follows (R. 162):

The transfer feature of the plan comes under sharp

criticism of the plaintiffs. They claim that the opera

tion of such a plan will perpetuate segregation. We do

not think the transfer provision is in and of itself ille

gal or unconstitutional. I t is the use and application of

it that may become a violation of constitutional rights.

It is in the same category as the pupil assignment laws.

They are not inherently unconstitutional. Shuttles-

worth v. Birmingham Board of Education, 162 F. Supp.

372, D. C. N. D. Ala., affirmed, 358 U. S. 101, 79 S. Ct.

221, 3 L. Ed. 2d 145. They may serve as an aid to

proper school administration. A similar transfer plan

was approved by this Court in Kelley v. Board of Edu

cation of City of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209, C. A. 6, cert,

denied, 361 U. S. 924, 80 S. Ct. 293, 4 L. Ed. 2d 240.

We adhere to our former ruling with the admonition

to the board that it cannot use this as a means to per

petuate segregation. In Boson v. Rippy, supra, the

court said, 285 F. 2d at p. 46, the transfer feature

“should be stricken because its provisions recognize

race as an absolute ground for the transfer of students,

10

and its application might tend to perpetuate racial dis

crimination.” (Emphasis added.) This transfer pro

vision functions only on request and rests with the

students or their parents and not with the board. The

trial judge retains jurisdiction during the transition

period and the supervision of this phase of the reor

ganization may be safely left in his hands (301 F. 2d

164,168).

Maxwell Case

With regard to the transfer plan, the Superintendent of

Schools agreed that the effect of the rule is to permit a

child or his parents ‘To choose segregation outside his zone

but not to choose integration outside of his zone” (E. 219);

that the provision was identical to that in the Nashville

plan {Ib id . ) ; and that as it operated in Nashville and was

intended to operate in Davidson County, white pupils were

not actually required to first go to the Negro schools in

their zones and then seek transfers out, and no Negro pupils

who did not affirmatively seek a transfer to an integrated

school were assigned to one (E. 219-220).

Dr. Eugene Weinstein, a professor at Vanderbilt Univer

sity in Nashville, testified about a survey of the attitudes

of Negro parents in Nashville who had a choice of whether

to send their children to desegregated schools. He indi

cated that the most frequent factor influencing those who

did not send their children to white schools was an unwill

ingness to separate several children in a family where they

had older children not eligible for desegregation under the

grade a year plan (E. 222-223). He said the experience in

Nashville indicated “mass paper transfers of Whites back

into what is historically the White school, of Negroes re

maining in what is historically the Negro school”, and that

the transfer provisions tend to keep the system oriented

11

toward a segregated system with, token desegregation (B.

226).

Six of the plaintiffs in this case reside nearer to all-Negro

schools than to white schools (B. 230 Finding No. 5).

At a further hearing held Jannary 10, 1961, on plaintiffs’

motions following the initial approval of the plan with

modifications, the evidence indicated that under the new

zones adopted under the plan, in the first four grades, there

were 288 white children in the Negro school zones and 405

Negro children in the zones of the white schools (B. 252).

The school authorities sent notices to the parents of these

children asking them to indicate within three days whether

they requested permission for the children to stay at the

school presently attended or requested permission for a

“transfer” to the newly zoned school (B. 247-250). Of

this group, only fifty-one pupils, all of them Negroes, asked

to attend the school in the new zones (B. 265).

As previously indicated the District Court approved the

transfer feature of the plan (B. 242). On appeal the Sixth

Circuit also approved this provision on the authority of

its decision in Goss (301 F. 2d at 829) (B. 284).

Argument

This case presents issues of the constitutionality of sub

stantially identical provisions in desegregation plans

adopted by two public school boards in response to direc

tions that they present plans to comply with Brown v.

B oard o f Education, 347 U. S. 483 and 349 II. S. 294. In

the second Brown decision the Court directed District

Courts “to consider the adequacy of any plans” which school

authorities might propose “to effectuate a transition to a

racially nondiscriminatory school system” (349 U. S. at

301). Subsequently, in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, the

12

Court unanimously reaffirmed Brown, stating that state

authorities were “duty hound to devote every effort toward

initiating- desegregation and bring about the elimination

of racial discrimination in the public school system” (358

U. S. at 7).

The plans for desegregation in the cases at bar provide

for gradual transition on a grade-by-grade basis for

a new system for determining the initial placement of

pupils. Under the plans, this is to be accomplished by a

geographic method of placing pupils according to residence

in desegregated school zones or attendance areas to be de

termined without reference to race. (See R. 31, ffl[ 3 and 4

of Knoxville plan and R. 214, Ulf 2 and 3 of Davidson County

plan.) This plan to change the prior pattern of separate

overlapping zones for Negroes and whites is, at least, on

its face, consistent with Brown which envisioned “revision

of school district and attendance areas into compact units

to achieve a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a nonracial basis” (349 U. S. at 300-301).3 How

ever, the challenged racial transfer provisions of the plans,

which become effective at the same time the new zoning

program goes into effect on a grade-by-grade basis,4

3 Numerous appellate decisions following Brow n have condemned

the practice which still lingers in many areas of maintaining

separate school zones for Negro and white pupils. See, e.g.,

Jon es v. School B oard o f City, o f A lexandria, 278 F . 2d 72, 76

(4th Cir. 1960) ; Marsh v. County School B oard o f R oanoke County,

Va., 305 F . 2d 94, 96 (4th Cir. 1962) ; Green v. School B oard o f

City o f R oanoke, 304 F . 2d 118, 124 (4th Cir. 1962) ; Northcross

v. Bd. o f E ducation o f City o f Memphis, 302 F. 2d 819, 823

(6th Cir. 1962) ; Bush v. Orleans Parish School B oard, 308 F . 2d

491, 498 (5th Cir. 1962) ; W heeler v. Durham City B oard o f E d u

cation, not yet reported (4th Cir., No. 8643, Oct. 12, 1962); cf.

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F . 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961).

4 The racial transfer provision thus is effective only in the grades

“desegregated” under the grade-a-year program, and not in grades

which remain under the old program of compulsory segregation

by separate racial zones.

13

operate to continue race as a factor in placing pupils in

schools, albeit on a partially optional basis. The racial

transfer rule continues a policy of racial discrimination

in the assignment of pupils to schools and to the extent

that it is used, necessarily works to preserve the racially

segregated pattern of schools previously created by state

law.5

The racial transfer rule (R. 31-32, 214-215) provides

that pupils be permitted upon written request to secure

transfers from the schools which they would be required

to attend under the nonracial zoning plan to other schools.

The eligibility of a student to obtain such a transfer is cast

in terms of race.

(1) A white student, qua white student, can transfer

from “a school previously serving colored students

only” ;

(2) a colored student, qua colored student, can transfer

from “a school previously serving white students

only” ;

(3) any student can transfer from a school “where the

majority of students of that school or in his or her

grade are of a different race.”

Thus the transfer rule is explicitly racial, providing for

transfers on the basis of a difference between the race of a

transfer applicant and either the race of the pupils whom

a school previously served, the race of a majority of the

5 School segregation was required in Tennessee by the Consti

tution of 1870, art. 11, sec. 12 and by Tennessee Code of 1955,

§§49-3701 to 49-3703. (See text at R. 14-15). The Tennessee

Supreme Court held the provisions invalid following Brow n v.

B oard o f Education, supra, in B oy v. Brittain , 297 S. W. 2d 72

(Tenn. 1956).

14

pupils in the school, or the race of a majority of the students

in the transfer applicant’s grade level in a given school.''

These transfers on the basis of racial factors operate

only in one direction, e.g., toward placing students in

schools that formerly served their own race exclusively

or schools or classes that have a majority of pupils of their

own race. This is the source of the transfer provision’s

invariable tendency to promote racial separation in schools

and of its racially discriminatory impact upon individual

pupils. No transfer is granted under this provision which

will have the effect of increasing desegregation; every

transfer necessarily will have the effect of increasing the

size of the majority race group in the schools to and from

which pupils are transferred.

The discrimination effected by the provision is equally

plain. Under the plan a white child living in the zone of a

“Negro school” (i.e., a formerly all-Negro school, or pre

dominantly Negro school, or a school with a Negro majority

in the applicant’s grade) is given the option of transferring

to a “white school.” But the plan makes no provision for

a Negro child living in the same zone to transfer out to a

white school; he must remain in the Negro school. It is

a very evident and obvious violation of equal protection to

deny a choice to one pupil and grant it to another student

similarly situated except for race.

Proponents of the racial transfer rule point to the fact

that the plan effects a correlative disparity in treatment

based on race in white school zones (where Negro pupils

can transfer out, but white pupils cannot), in an attempt to

justify the discriminatory denial of transfers to Negroes 6

6 It should be realized that the concept of pupils being initially

assigned on a nonracial basis and then transferred on a racial basis

is largely fictitious. In practice, pupils simply choose a school on

the basis of race before going to any school (R. 141, 219-220).

15

living in Negro school areas. It is argued that equal pro

tection is afforded by the plan since some whites are also

denied transfers because of their race, and thus there are

reciprocal discriminations based on race. Actually, this

symmetrical inequality of treatment based on race is

familiarly characteristic of racial segregation rules.7

Of more relevance is the fact that the racial discrimina

tions in both the Negro and white zones operate to limit

desegregation rather than to advance it. Neither a Negro

nor a white child is granted a racial transfer to extend

desegregation, but either child can obtain one if it will

operate to decrease or prevent desegregation.

But, the theory that the correlative discriminations

against Negroes and whites in some way “balance” each

other does more than merely defy the homily that “two

wrongs do not make a right.” More fundamentally, it

ignores the important constitutional principle that Four

teenth Amendment rights are personal rights.8 This Court

7 After all, a bus segregation law forbids whites from sitting

with Negroes or in the back of a bus, just as it forbids Negroes

from sitting with whites in the front. But cf. Brow der v. Gayle,

142 F . Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956), aff’d 352 U. S. 903.

8 Paradoxically, defenders of school segregation have frequently

taken the opposite tack and argued that the personal nature of

Negro pupil’s rights plus certain statutory administrative rem

edies limited the relief that a court could grant in school de

segregation eases to ruling on the admissions of individual pupils

while leaving generally applicable racial assignment policies be

yond the reach of the courts. I t is submitted that these arguments

have been properly rejected since Negro children’s right to edu

cation in a nonsegregated school system can be protected only by

removing racially discriminatory rules which apply to all mem

bers of the racial group segregated by state authorities. See, for

example, Brunson v. B oard o f Trustees o f School District No. 1

o f Clarendon County, S. C., 4th Cir., No. 8727, December 7, 1962

(reversing an order dismissing as to all plaintiffs but the first

one named in the complaint) ; W heeler v. Durham, City Board

o f Education, 4th Cir. No. 8643, decided October 12, 1962 (re

16

emphasized this in rejecting an argument that a racial re

strictive covenant on land enforced against Negroes was

valid since state courts would enforce similar covenants

against white occupancy, in Shelley v. K raem er, 334 U. 8.

1, 22 :

But there are more fundamental considerations. The

rights created by the first section of the Fourteenth

Amendment are, by its terms, guaranteed to the indi

vidual. The rights established are personal rights.

[Footnote citing McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F . R. Co.,

235 U. S. 151, 151; Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U. S. 337; Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633.] It

is, therefore, no answer to these petitioners to say that

the courts may also be induced to deny white persons

rights of ownership and occupancy on grounds of race

or color. Equal protection of the laws is not achieved

through indiscriminate imposition of inequalities.

See also, Brown v. B oard o f Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300;

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 635; Sipuel v. Board o f

Regents, 332 U. S. 631, 633, treating the rights involved

here as personal.

The appellate decisions which have dealt directly with

the issue presented here are Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43,

47 (5th Cir. 1960) and Dillard v. School Board o f City o f

Charlottesville, Va., not yet reported (4th Cir., No. 8638,

decided Sept. 17, 1962), which held the racial transfer plan

versing a trial court which had denied all relief on the ground

that plaintiffs “simply want nothing more or less than a general

order of desegregation”) ; Jackson v. School B oard o f City o f

Lynchburg, 201 F . Supp. 620, 625-629 (W. D. Ya. 1962) (re

jecting such an argument), rev’d in part on other grounds, not

yet reported (4th Cir., No. 8722, Sept. 28, 1962). See also Green

v. School B oard o f City o f Boanoke, Ya., 304 F. 2d 118, 124

(4th Cir. 1962).

17

invalid, and the three decisions of the Sixth Circuit which

upheld the transfer system, e.g., K elley v. Board o f Educa

tion, 270 F. 2d 209, 228 (6th Cir. 1959), and the two cases

now being reviewed, Goss v. B oard o f Education, 301 F. 2d

164, 168 (6th Cir. 1962), and Maxwell v. County Board

o f Education, 301 F. 2d 828, 829 (6th Cir. 1962).9

The decision in Boson v. Rippy, supra, emphasized that

the plan embodied racial classifications for transfer which

the court deemed “hardly less unconstitutional than such

classification for purposes of original assignment to a

public school” (285 F. 2d 48). In the Dillard case, supra,

the majority held the racial transfer device invalid stat

ing that “the purpose and effect of the arrangement is

to retard integration and retain the segregation of the

races” and that this “can hardly be denied.” The Court

ordered 17 Negro pupils admitted to a white school outside

their zone of residence since white pupils in the zone were

granted such transfers.

In K elley v. Board o f Education, 270 F. 2d 209, 228 (6th

Cir. 1959), the Sixth Circuit upheld the racial transfer

provision as it did in the cases at bar. The Court in K elley

held that it was permissible to allow a parent to “voluntarily

choose a school where only one race attends” (270 F. 2d at

229), but did not discuss the fact that the option to trans

fer was conferred and denied on the basis of race or the

9 Among District Court opinions dealing with the issue are

M app v. B oard o f Education o f City o f Chattanooga, Tenn., 203

F . Supp. 843, 853 (B . D. Tenn. 1962), appeal pending (transfer

plan held invalid on authority of Boson v. R ippy, su pra ; the court

declined to follow K elley v. B oard o f E ducation stating that the

primary purpose of the transfer rule was to prevent or delay

desegregation) ; Jackson v. School B oard o f the City o f Lynch

burg, Va., 203 F. Supp. 701, 704-706 (W. D. Ya. 1962), appeal

pending (transfer rule held valid) ; Thompson v. County School

B oard o f Arlington County, 204 F. Supp. 620, 625-626 (B . D. Ya.

1962), appeal pending (transfer plan held valid; injunction dis

solved).

18

asserted tendency of the rule to preserve segregation. The

Court remanded leaving open to plaintiffs only the right

to show that there were “impediments to the exercise of a

free choice” (270 F. 2d at 230). The K elley decision relied

primarily upon Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D.

S. C. 1955), which is discussed in detail in the footnote

below.10

In the Goss opinion (301 F. 2d at 168; R. 162-163), the

Sixth Circuit adhered to the result reached in K elley, supra,

but attempted to qualify its approval of the plan by stating

that while it was “not inherently unconstitutional” it might

be unconstitutional as applied and that it was approved

“subject to it being used for proper school administration

purposes and not for the perpetuation of segregation” (301

F. 2d at 168; R. 163). The Court in Goss also attempted to

distinguish Boson v. Rippy, supra, by mentioning that the

transfer rule functioned only upon the request of students

or parents and not the school board, and that supervision

might safely be left in the hands of the trial judge who

retained jurisdiction. Petitioners submit that there is no

distinction at all since both factors obtained in Boson v.

Rippy as well.

10Briggs v. E lliott, 132 F . Supp. 776 (E . D. S. C. 1955), was

an opinion rendered by a three-judge court that considered this

case (which was one of those consolidated with Brown v. B oard

o f Education, supra), on remand following this Court’s decision

in May 1955. The opinion was announced from the bench at the

beginning of the hearing as the form of an order to be entered

in accord with this Court’s mandate. No issue relating to any

specific proposal or plan for desegregation was before the Court.

The Briggs opinion attempts to state what this Court did not

decide in Brown, and stressed that court’s view as to the legality

of “voluntary segregation,” though in general terms and without

any attempt to define what would constitute “voluntary segrega

tion.” Certainly, nothing in Briggs could undercut this Court’s

unanimous declaration in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7, that

school officials are “duty bound to devote every effort toward

initiating desegregation.”

19

Beyond this, the court’s seeming qualification of its ap

proval of the plan is illusory since it did not indicate under

what conditions it would ever consider racial transfers im

proper. Nor is it evident how the trial court’s retention of

jurisdiction is thought to afford any safeguard since no

standards for judging the application of the plan are pro

vided. Moreover, there is no hint in the record that the

transfer provision was ever considered by the Court of the

parties as a temporary transitional device. Indeed, if it

had been so proffered at trial, the Court of Appeals, as a

matter of consistency, should have rejected it as inadequate

on the same ground the grade-a-year feature was rejected,

i.e., that the defendants had not sustained their burden of

establishing that the plan was consistent with good faith

compliance at the earliest practicable date by evidence of

legitimate obstacles to desegregation as contemplated by

Brown v. B oard o f Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300-301 (301

F. 2d at 166-167; R. 158-162).

There are, of course, further compelling reasons why the

racial transfer is inappropriate even as an interim device.

I t does not suppress racial discriminations or “preclude

their revival” (Cf. United States v. Crescent Amusement

Co., 323 U. 8. 173, 188 (1944)); rather, it continues racial

discrimination in a slightly different form. It bears no

rational relationship to solving any school administrative

problem relevant to the proper granting of delay in desegre

gation. Indeed, it is more likely to aggravate administra

tive problems by disturbing the efficacy of school zones

in properly distributing pupils among schools in relation to

capacity. Certainly it encourages, and, indeed, renders more

plausible, an effort to manipulate school zone lines on a

racial basis. This is true since in a given school zone estab

lished on the basis of student population and school capac

ity, if sufficient numbers of pupils of a minority race are

20

transferred out, the authorities will be justified in expand

ing the school zone to include more members of the ma

jority race (who cannot transfer out) in order to fully

utilize the available space in the school. That this is a real

and not a highly suppositious possibility is amply demon

strated by the New Rochelle, New York school system where

this sequence of events occurred. See Taylor v. B oard o f

Education o f the City o f New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181,

184-185 (S. D. N. Y. 1961), appeal dismissed 288 F. 2d 600

(2nd Cir. 1961); 195 F. Supp. 231 (S. D. N. Y. 1961), aff’d

294 F . 2d 36 (2nd Cir. 1961), cert, den., 368 U. S. 940.

Indeed, in the Taylor case, supra, the Court went beyond

condemning a practice like that here. It held that where

school officials had once permitted white children to trans

fer out of a Negro school zone but abandoned this practice

in 1949, and had manipulated school zone lines on a racial

basis, the school board was still under a duty to afford

Negro pupils in the school zone thus created an opportunity

to transfer to other schools.

Furthermore, the Sixth Circuit’s comparison of this

racial transfer rule with pupil assignment laws, e.g., as in

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham B oard o f Education, 162 F.

Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala. 1958), aff’d on limited grounds, 358

U. S. 101, and Carson v. W ar lick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir.

1956), is not at all apt, for the pupil placement laws con

spicuously did not maintain race as a factor for determin

ing transfers. The clearest holdings that racial considera

tions may not be used in determining either pupil transfers

or initial placements may be found in various cases involv

ing improper application of pupil placement laws. See, for

example, Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961);

Mannings v. Board o f Public Instruction, 277 F . 2d 370

(5th Cir. 1960) ; Green v. School Board o f City o f Roanoke,

304 F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962); Marsh v. School B oard o f

21

Roanoke County, 305 F. 2d 94 (4th Cir. 1962); W heeler v.

Durham City B oard o f Education, not yet reported (4th

Cir., No. 8643, Oct. 12, 1962).

The rise of racial factors to determine school assignments

has not and cannot be justified as reasonably related to any

legitimate governmental objectives. The classification of

school buildings on the basis of the race of the pupils for

merly occupying them is truly bizarre. Professor Charles

Black has observed that: “A small proportion of Negro

‘blood’ puts one in the inferior race for segregation pur

poses ; this is the way in which one deals with a taint, such

as a carcinogene in cranberries.” 11 By the racial transfer

rule the “taint” has been transferred to buildings, render

ing even a form erly all Negro school so unfit for white chil

dren as to justify the special provision. This serves no

legitimate state purpose.

The racial majority rule is similarly unrelated to any

proper governmental objective. It is passionately defended

by some as the means of protecting a sole tiny child from

disastrous imaginary personal consequences upon being

thrust unwilling, as the lone member of his race, into a

hostile class, when actually the provision permits transfers

by pupils in any school or class where there is not a provi

dential exact mathematical equality between the number of

pupils of each race. The school authorities have argued

that the provision is necessary to protect pupils in a small

minority from maladjustments or emotional harm upon

being placed in a hostile environment. No such blanket

racial rule as this is needed to provide transfers for truly

maladjusted children, if transfers are indicated, and the

school authorities have an inherent and unchallenged power

to grant transfers based on individual hardships and other

11 Black, “The Lawfulness of the Segregation Decisions,” 69

Yale L. J . 421, 426 (1960).

22

educationally acceptable standards unrelated to preserva

tion of the segregation system.

This Court held in Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, that

“Classifications based solely upon race must be scrutinized

with particular care, since they are contrary to our tradi

tions and hence constitutionally suspect.” The Court went

on to find segregation in public education to be “not reason

ably related to any proper governmental objective” and a

deprivation of liberty in violation of due process. Plain

tiffs respectfully submit that the racial classifications made

by the school authorities in this case are equally unconsti

tutional and that the defendants should be required to in

stitute a truly nonracial system of determining the place

ment and admission of pupils in schools.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is submitted that the

judgments of the court below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J a ck Gr e e n b e r g

C o n sta n ce B a k er M o tley

J a m es M. N a b r it , I I I

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

C arl A. C owan

2212 Vine Avenue, S. E.

Knoxville, Tennessee

Z. A lex a n d er L ooby

A von N. W il l ia m s

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

Attorneys fo r Petitioners

3 8