Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education Supplemental Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education Supplemental Brief for Appellants, 1966. a34c3b23-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a66f0c59-7c25-40fe-b324-14c735d803cb/stell-v-savannah-chatham-county-board-of-education-supplemental-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

9

I >. ft

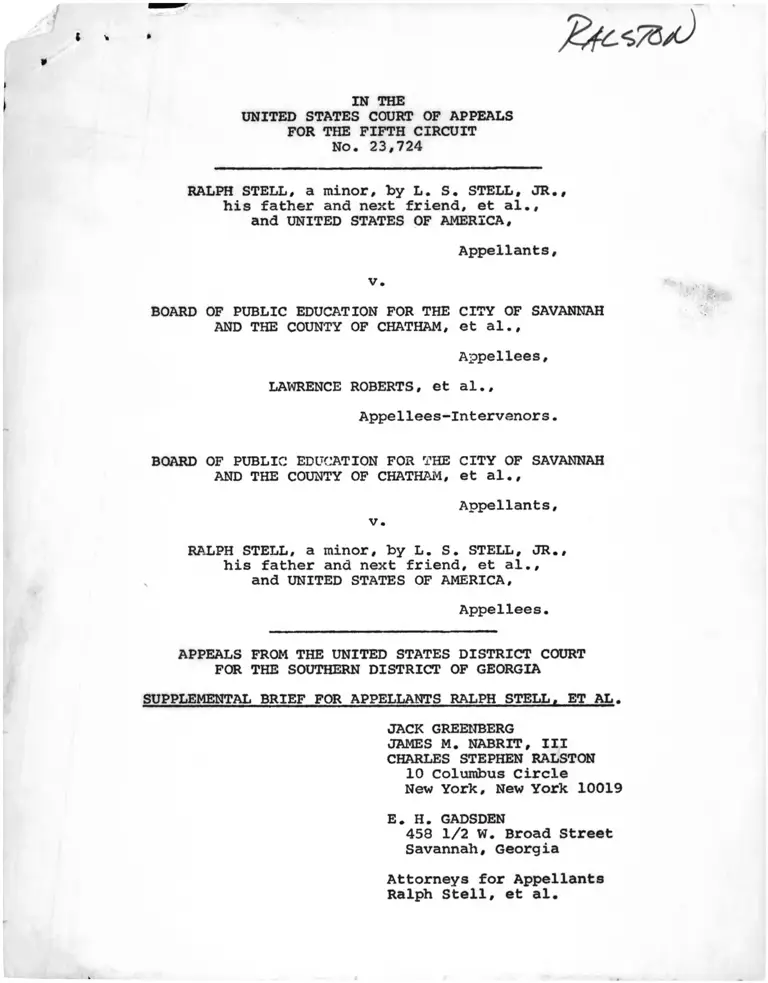

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 23,724

RALPH STELL, a minor, by L . S. STELL, JR.,

his father and next friend, et al.,

and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION FOR THE CITY OF SAVANNAH

AND THE COUNTY OF CHATHAM, et al..

Appellees,

LAWRENCE ROBERTS, et al..

Appellees-Intervanors.

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION FOR THE CITY OF SAVANNAH

AND THE COUNTY OF CHATHAM, et al..

Appellants,

v.

RALPH STELL, a minor, by L. S. STELL, JR.,

his father and next friend, et al.,

and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellees.

APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS RALPH STELL. ET AL.

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E. H. GADSDEN

458 1/2 W. Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

Ralph Stell, et al.

* «

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 23,724

RALPH STELL, a minor, by L. S. STELL, JR.,

his father and next friend, et al.,

and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION FOR THE CITY OF SAVANNAH

AND THE COUNTY OF CHATHAM, et al..

Appellees,

LAWRENCE ROBERTS, et al.,

Appellees-Intervenors,

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION FOR THE CITY OF SAVANNAH

AND THE COUNTY OF CHATHAM, et al..

Appellants,

v.

RALPH STELL, a minor, by L. S. STELL, JR., his father and next friend, et al.,

and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellees.

APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS RALPH STELL. ET AL.

Introduction

Pursuant to the request of the Court at oral argument,

appellants Ralph Stell, et al. present this supplemental brief

setting forth its position with regard to the plan for desegregation

for the Board of Public Education for the City of Savannah and

County of Chatham proposed by the School Board at oral argument.

Preliminarily, it should be pointed out that the majority

of the sections of the proposed plan of the School Board comply

to the letter with the decree set out by this Court in its en

banc decision in the United States of America, et al. v. Jefferson

County, et al.. ___F.2d ____ (1967). Appellants, of course,

agree that the unchanged sections should be entered.

The following sections have been altered by the School

Board:

I. Speed of Desegregation

II. (a) Who May Exercise Choice

(b) Annual Exercise of Choice

(c) Choice Period

(f) Mailing of Explanatory Letters

Choice Forms

(j) Choices Not on Official Forms

(k) Choice Forms Binding

IV. (a) Transfers for Special Needs

VI. (b) Remedial Programs

VIII. (d) Faculty Employment

This brief will first discuss those sections that have been

changed with which appellants have no objections and, secondly,

will discuss those changed sections with which we do have objections.

We will propose an alternative section to each of the ones to which

we have an objection. In addition, the brief will set out a

complete proposed decree.

2

I

Changed Sections not Objected to

A. 11(b)

In this Court's proposed decree, Section 11(b) — Annual

Exercise of Choice — reads as follows: "All students, both white

and Negro, shall be required to exercise a free choice of schools

annually." The School Board's proposal omits the language "both

white and Negro," so as to read only "all students shall be

required to exercise a free choice of schools annually." Appellants

have no objections to this change.

B. 11(c)

The School Board, for administrative reasons, has changed

the choice period to encompass the month of February rather than

the month of March as in the Jefferson County decree. Appellants

have no objections to this change.

C. IV (a)

The School Board has proposed a modification of provision

iy(a) dealing with transfers. They have stricken the original

section IV(a) from the Jefferson County decree on the grounds that

since all grades are now desegregated in the Savannah-Chatham school

district the provision is no longer needed. Appellants have no

objection to the striking of this section. The School Board has

also modified section IV(b) in the Jefferson plan, which becomes

IV(a) in the School Board's proposed plan, to omit the language

- 3 -

II The effect of"at the beginning of any school term or semester,

this modification is to liberalize the provision of the Jefferson

County decree so as to allow transfers during the course of the

school term if a course of study becomes available during the term.

Appellants have no objection to the modification.

II

CHANGES TO WHICH APPELLANTS OBJECT

A. I.

The School Board has modified considerably paragraph I

of the Jefferson County decree dealing with speed of desegregation.

Some modifications appellants have no objections to since they

relate to the fact that all grades are already covered by the

desegregation plan now in effect.

Appellants do have questions, however, concerning the atten

dance areas that the School Board has set up and under which it

is operating its freedom-of-choice plan. This is one of the

questions, as indicated in appellants' original brief in this

Court, that we feel it necessary to have a full hearing in the

district court in order to develop evidence concerning the effect

of the existing attendance zones on the adequacy of the desegre

gation plan.

For this reason, appellants object particularly to the

language proposed by the School Board which indicates that it is

already actually using attendance areas that operate on a dis

criminatory basis. As argued in our original brief, appellants

urge that this Court adopt a general provision as a governing rule

4 -

concerning attendance areas that is modeled on the guidelines for

school desegregation of the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare, Section 181.32 (see appellants' Brief, p. 19). This

would establish a general policy concerning the adequacy of

attendance areas and would allow the parties to litigate further

the question of the adequacy of existing attendance areas to

comply with that policy.

Appellants also object to the language proposed that states

as a fact that faculty and staff have been desegregated fully for

the present school term and that "segregation, as such, does not

now exist in its system."

Therefore, appellants propose the following as paragraph I

of the desegregation plan:

I. Speed of Desegregation

As to students, the Board of Public Education

for the City of Savannah and the County of Chatham has

been in the process of desegregating its system under

judgments of the Fifth circuit Court of Appeals since

September, 1962, having desegregated all grades in its

system commencing with the school year 1966-67; and

as to faculty and administrative staff, in part for

the school years 1966-67 and 1967-68. Its desegre

gation plan has been based largely upon a freedom-

of-choice plan and it intends to continue with

such plan for the school years 1968, 1969 and

thereafter, providing desegregation can be legally

5

accomplished by this plan; if not, then any of the

parties in this action may seek court approval of

a plan which will accomplish such objective. The

School Board is presently using attendance areas in

each of which at least two schools will be located.

No school will be located in more than one attendance

area. Free choice is offered at all schools within

each attendance area. Attendance areas established

by the School Board may be approved upon a showing

that they will most expeditiously eliminate segre

gation and all other form of discrimination.

B. 11(a)

The School Board has proposed a modification of section

11(a) dealing with who may exercise choice. It provides that:

A student and the parent or other adult

person then serving as his parent shall

jointly exercise a choice for the ninth

or higher grade, or where the student

has reached the age of fifteen at the

time of the exercise of the choice; if the parent or other adult person serving

as his parent and the student do not agree

to the school chosen, then the decision of

the former shall prevail.

Appellants feel that the requirement that both the parent and the

child sign the choice form may act as an added burden to the free

exercise of choice; therefore, they would urge that the provision

set forth in the Jefferson County decree as II(a) be retained

for this school district. Such a section will adequately protect

the ultimate right of a parent to choose his child's school.

6

C. 11(f)

The School Board has proposed a modification of section

II(f) dealing with the mailing of explanatory letters and choice

forms so as to allow as an alternative the delivery of letters and

choice forms to the students in the school system. The appellants

have no objection to such an alternative method so long as it

in fact does result in a choice form reaching every parent in

the school system and choices being made by all students.

Therefore, they would suggest the approval of the

School Board's proposed section 11(f), with the deletion of the

final sentence, _i.e., "the forms now being used by the Board and

the method employed for handling choices is affirmed and approved

as in compliance with (2) hereof." The deletion of this sentence

would allow appellants or the United States to go into court to

investigate the adequacy of the delivery of choice forms if they

feel that this is an issue.

D. II (j)

The School Board has suggested an alternative section

dealing with choices not on official forms. Appellants appreciate

the School Board's concern that sufficient information be on any

choice form they receive. However, we also feel that the required

information be kept to a minimum so as to make it as easy as

possible to exercise a choice. Therefore, appellants propose

the following:

7

II (j) Choices Not on Official Form

The exercise of choice may also be made by

the submission in like manner of any other writing

which contains the name of the student, his residence,

the school chosen, and is signed as heretofore

required in this plan.

E. II (k)

The School Board has proposed a modification of section

II(k) dealing with choice forms being binding. The modification

consists of a deletion of the language in the Jefferson County

section II(k) referring to the change of choices by parents

making different choices from their children under the provision

of paragraph 11(a) of the decree. Since appellants urge the

retention of section 11(a) in the language of the Jefferson County

decree, they also urge the retention of the language of II(k)

of that decree.

F . -jEVfd)

The School Eoard has proposed an alteration of section

IV (d) of the Jefferson County decree dealing with remedial pro

grams. Appellants urge that the provision as set forth in the

Jefferson County decree be retained so that the obligation on the

School Board will be clear.

G. VIII(a)

The School Board has modified section VIII(a) of the

Jefferson County decree dealing with faculty employment. The

- 8 -

aetGO

modification consists of changing the sentence in the decree

beginning with "defendants shall take positive and affirmative

steps...etc." In its place they have substituted a sentence

stating that "the Board has taken positive and affirmative steps

...etc." Appellants are not satisfied that this statement is

supported by the facts since it is their understanding that

affirmative assignment of teachers has not been undertaken by the

School Board as yet. Therefore, appellants desire the retention

of the language of the Jefferson County decree.

CONCLUSION

Again, appellants urge upon the Court the necessity, given

the history of this litigation, of its directing the court below

to enter a specific plan. We believe that the proposed decree

that follows is appropriate and, as indicated above, will allow

the parties to litigate those issues concerning the plan about

which there may remain questions.

PROPOSED DECREE

I

SPEED OF DESEGREGATION

As to students, the Board of Public Education for the

City of Savannah and the County of Chatham has been in the process

of desegregating its system under judgments of the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals since September, 1962, having desegregated all

9

grades in its system commencing with the school year 1966-67;

and as to faculty and administrative staff, in part for the school

years 1966-67 and 1967-68. Its desegregation plan has been based

largely upon a freedom-of—choice plan and it intends to continue

with such plan for the school years 1968, 1969 and thereafter,

providing desegregation can be legally accomplished by this plan;

if not, then any of the parties in this action may seek court

approval of a plan which will accomplish such objective. The

School Board is presently using attendance areas in each of which

at least two schools will be located. No school will be located

in more than one attendance area. Free choice is offered at

all schools within each attendance area. Attendance areas estab

lished by the School Board may be approved upon a showing that

they will most expeditiously eliminate segregation and all other

form of discrimination.

II

EXERCISE OF CHOICE

The following provisions shall apply to all grades:

(a) Who May Exercise Choice. A choice of schools may be

exercised by a parent or other adult person serving as the

student's parent. A student may exercise his own choice if he

(1) is exercising a choice for the ninth or a higher grade, or

(2) has reached the age of fifteen at the time of the exercise

of choice. Such a choice by a student is controlling unless a

different choice is exercised for him by his parent or other

adult person serving as his parent during the choice period or

10

at such later time as the student exercises a choice. Each

reference in this decree to a student's exercising a choice means

the exercise of the choice, as appropriate, by a parent or such

other adult, or by the student himself.

(b) Annual Exercise of Choice. All students shall be require

to exercise a free choice of schools cinnually.

(c) Choice Period. The period for exercising choice shall

commence February 1, 1968 and end with the last day of February,

1968, and in subsequent years shall be the entire month of

February preceding the school year for which the choice is to be

exercised. No student or prospective student who exercises his

choice within the choice period shall be given any preference

because of the time within the period when such choice was exer

cised.

(d) Mandatory Exez'cise of Choice. A failure to exercise

a choice within the choice period shall not preclude any student

from exercising a choice at any time before he commences school

for the year with respect to which the choice applies, but such

choice may be subordinated to the choices of students who exer

cised choice before the expiration of the choice period. Any

student who has not exercised his choice of school within a week

after school opens shall be assigned to the school nearest his

home where space is available under standards for determining

available space which shall be applie d uniformly throughout the

system.

11

(e) Public Notice. On or within a week before the date

the choice period opens, the defendants shall arrange for the

conspicuous publication of a notice describing the provisions of

this decree in the newspaper most generally circulated in the

community. The text of the notice shall be substantially similar

to the text of the explanatory letter sent home to parents.

Publication as a legal notice will not be sufficient. Copies

of this notice must also be given at that time to all radio and

television stations located in the community. Copies of this

decree shall be posted in each school in the school system and at

the office of the Superintendent of Education.

(f) Mailing or Personal Delivery of Explanatory Letters

and Choice Forms. On the first day of the choice period one of

two methods may be employed in notifying parents or other adult

persons serving as parents, (1) distributing by first-class mail

an explanatory letter and a choice form to the parent (or other

adult person acting as parent, if known to the Board) of each

student, together with a return envelope addressed to the

Superintendent, or (2) by delivering such explanatory letters and

choice forms to the student with adequate procedures to insure the

delivery of the notice and the exercise and return of the signed

choice form.

(g) Extra Copies of the Explanatory Letter and Choice Form.

Extra copies of the explanatory letter and choice form shall be

freely available to parents, students, prospective students, and

the general public at each school in the system and at the office

of the Superintendent of Education during the times of the year

when such schools are usually open.

— 12 —

(h) Content of Choice Form. Each choice form shall set

forth the name and location and the grades offered at each school

and may require of the person exercising the choice the name,

address, age of student, school and grade currently or most

recently attended by the student, the school chosen, the signature

of one parent or other adult person serving as parent, or where

appropriate the signature of the student, and the identity of the

person signing. No statement of reasons for a particular choice,

or any other information, or any witness or other authentication,

may be required or requested, without approval of the Court.

(i) Return of Choice Form. At the option of the person

completing the choice form, the choice may be returned by mail,

in person, or by messenger, to, (1) the school the student is

then attending, (2) the school chosen by the student, or, if not

convenient, then (3) to any other school in the system, or (4)

to the office of the Superintendent.

(j) Choices Not on Official Form. The exercise of choice

may also be made by the submission in like manner of any other

writing which contains the name of the student, his residence,

the school chosen, and is signed as heretofore required in this

Plan.

(k) Choice Forms Binding. When a choice form has once

been submitted and the choice period has expired, the choice is

binding for the entire school year and may not be changed except

in cases of parents making different choices from their children

under the conditions set forth in paragraph II(a) of this decree

13

and in exceptional cases Where, absent the consideration of race,

a change is educationally called for or where compelling hardship

is shown by the student. A change in family residence from one

neighborhood to another shall be considered an exceptional case

for purposes of this paragraph.

(l) Preference in Assignment. In assigning students to

schools, no preferences shall be given to any student for prior

attendance at a school and, except with the approval of Court in

extraordinary circumstances, no choice shall be denied for any

reason other than overcrowding. In case of overcrowding at any

school, preference shall be given on the basis of the proximity

of the school to the homes of the students choosing it, without

regard to race or color. Standards for determining overcrowding

shall be applied uniformly throughout the system.

(m) Second Choice Where First Choice is Denied. Any

student whose choice is denied must be promptly notified in writing

and given his choice of any school in his attendance area serving

his grade level where space is available. The student shall

have seven days from the receipt of notice of a denial of first

choice in which to exercise a second choice.

(n) Transportat ion. Where transportation is generally

provided, buses must be routed to the maximum extent feasible

in light of the geographic distribution of students, so as to

serve each student choosing any school in the system. Every

student choosing either the formerly white or the formerly Negro

school nearest his residence must be transported to the school

14

to which he is assigned under these provisions, whether or not

it is his first choice, if that school is sufficiently distant

from his home to make him eligible for transportation under gener

ally applicable transportation rules.

(o) Officials Not to Influence Choice. At no time shall

any official, teacher, or employee of the school system influence

any parent, or other adult person serving as a parent, or any

student, in the exercise of a choice or favor or penalize any

person because of a choice made. If the defendant school board

employs professional guidance counselors, such persons shall

base their guidance and counselling on the individual student's

particular personal, academic, and vocational needs. Such guidance

and counselling by teachers as well as professional guidance coun

sellors shall be available to all students without regard to race

or color.

(p) Protection of Persons Exercising Choice. Within their

authority school officials are responsible for the protection of

persons exercising rights under or otherwise affected by this

decree. They shall, without delay, take appropriate action with

regard to any student or staff member who interferes with the

successful operation of the plan. Such interference shall include

harassment, intimidation, threats, hostile words or acts, and

similar behavior. The school board shall not publish, allow, or

cause to be published, the names or addresses of pupils exercising

rights or otherwise affected by this decree. If officials of the

school system are not able to provide sufficient protection, they

15

shall seek whatever assistance is necessary from other appropriate

officials.

Ill

PROSPECTIVE STUDENTS

Each prospective new student shall be required to exercise

a choice of schools before or at the time of enrollment. All such

students known to defendants shall be furnished a copy of the

prescribed letter to parents, and choice form, by mail or in person,

on the date the choice period opens or as soon thereafter as the

school system learns that he plans to enroll. Where there is no

pre-registration procedure for newly entering students, copies of

the choice forms shall be available at the Office of the

Superintendent and at each school during the time the school is

usually open.

IV

TRANSFERS

(a) Transfers for Special Needs. Any student who requires

a course of study not offered at the school to which he has been

assigned may be permitted, upon his written application, to

transfer to another school which offers courses for his special

needs.

(b) Transfers to Special Classes or Schools. If the

defendants operate and maintain special classes or schools for

physically handicapped, mentally retarded, or gifted children, the

- 16

defendants may assign children to such schools or classes on a

basis related to the function of the special class or school that

is other than freedom of choice. In no event shall such assign

ments be made on the basis of race or color or in a manner which

tends to perpetuate a dual school system based on race or color.

V

SERVICES. FACILITIES. ACTIVITIES AND PROGRAMS

No student shall be segregated or discriminated against on

account of race or color in any service, facility, activity, or

program (including transportation, athletics, or other extra

curricular activity) that may be conducted or sponsored by the

school in which he is enrolled. A student attending school for the

first time on a desegregated basis may not be subject to any dis

qualification or waiting period for participation in activities

and programs, including athletics, which might otherwise apply

because he is a transfer or newly assigned student except that such

transferees shall be subject to long-standing, non-racially based

rules of city, county, or state athletic associations dealing with

the eligibility of transfer students for athletic contests. All

school use or school—sponsored use of athletic fields, meeting

rooms, and all other school related services, facilities, activities,

and programs such as commencement exercises and parent—teacher

meetings which are open to persons other than enrolled students,

shall be open to all persons without regard to race or color. All

special educational programs conducted by the defendants shall be

conducted without regard to race or color.

- 17

VI

SCHOOL EQUALIZATION

(a) Inferior Schools. In schools heretofore maintained for

Negro students, the defendants shall take prompt steps necessary

to provide physical facilities, equipment, courses of instruction,

and instructional materials of quality equal to that provided in

schools previously maintained for white students. Conditions

of overcrowding, as determined by pupil-teacher ratios and pupil-

classroom ratios shall, to the extent feasible, be distributed evenl

between schools formerly maintained for Negro students and those

formerly maintained for white students. If for any reason it is

not feasible to improve sufficiently any school formerly main

tained for Negro students, where such improvement would otherwise

be required by this paragraph, such school shall be closed as

soon as possible, and students enrolled in the school shall be

reassigned on the basis of freedom of choice. By October of

each year, defendants shall report to the Clerk of the Court pupil-

teacher ratios, pupil-classroom ratios, and per-pupil expenditures

both as to operating and capital improvement costs, and shall

outline the steps to be taken and the time within which they shall

accomplish the equalization of such schools.

(b) Remedial Programs. The defendants shall provide

remedial education programs which permit students attending or

who have previously attended segregated schools to overcome past

inadequacies in their education.

18

VII

NEW CONSTRUCTION

The defendants, to the extent consistent with the proper

operation of the school system as a whole, shall locate any new

school and substantially expand any existing schools with the

objective of eradicating the vestiges of the dual system.

VIII

FACULTY AND STAFF

(a) Faculty Employment. Race or color shall not be a factor

in the hiring, assignment, reassignment, promotion, demotion, or

dismissal of teachers and other professional staff members, in

cluding student teachers, except that race may be taken into

account for the purpose of counteracting or correcting the effect

of the segregated assignment of faculty and staff in the dual

system. Teachers, principals, and staff members shall be assigned

to schools so that the faculty and staff is not composed exclusively

of members of one race. Wherever possible, teachers shall be

assigned so that more than one teacher of the minority race (white

or Negro) shall be on a desegregated faculty. Defendants shall

take positive and affirmative steps to accomplish the desegregation

of their school faculties and to achieve substantial desegregation

of faculties in as many of the schools as possible for the 1967-68

school year notwithstanding that teacher contracts for the 1967-68

or 1968-69 school years may have already been signed and approved.

The tenure of teachers in the system shall not be used as an excuse

19

for failure to comply with this provision. The defendants shall

establish as an objective that the pattern of teacher assignment

to any particular school not be identifiable as tailored for a

heavy concentration of either Negro or white pupils in the school.

(b) Dismissals. Teachers and other professional staff

members may not be discriminatorily assigned, dismissed, demoted,

or passed over for retention, promotion, or rehiring, on the ground

of race or color. In any instance where one or more teachers or

other professional staff members are to be displaced as a result

of desegregation, no staff vacancy in the school system shall be

filled through recruitment from outside the system unless no such

displaced staff member is qualified to fill the vacancy. If, as

a result of desegregation, there is to be a reduction in the total

professional staff of the school system, the qualifications of

all staff members in the system shall be evaluated in selecting

the staff member to be released without consideration of race or

color. A report containing any such proposed dismissals, and the

reasons therefor, shall be filed with the Clerk of the Court,

serving copies upon opposing counsel, within five (5) days after

such dismissal, demotion, etc., as proposed.

(c) Past Assignmentr-. The defendants shall take steps to

assign and reassign teachers and other professional staff members

to eliminate the effects of the dual school system.

V- 20

IX

REPORTS TO THE COURT

(a) Report on Choice Period. The defendants shall serve

upon the opposing parties and file with the Clerk of the Court on

or before June 1, 1968, and in each subsequent year on or before

June 1, a report tabulating by race the number of choice appli

cations and transfer applications received for enrollment in each

grade in each school in the system, and the number of choices and

transfers granted and the number of denials in each grade of each

school. The report shall also state any reasons relied upon in

denying choice and shall tabulate, by school and by race of student,

the number of choices and transfers denied for each such reason.

In addition, the report shall show the percentage of pupils

actually transferred or assigned from segregated grades or to

schools attended predominantly by pupils of a race other than the

race of the applicant, for attendance during the 1967-68 school

year, with comparable data for the 1966-67 school year. Such

additional information shall be included in the report served upon

opposing counsel and filed with the Clerk of the Court.

(b) Report After School Opening. The defendants shall,

in addition to reports elsewhere described, serve upon opposing

counsel and file with the Clerk of the Court within 15 days after

the opening of schools for the fall semester of each year, a

report setting forth the following information:

(i) The name, address, grade, school of choice and school

of present attendance of each student who has withdrawn or requested

21

withdrawal of his choice of school or who has transferred after

the start of the school year, together with a description of any

action taken by the defendants on his request and the reasons

therefor.

(ii) The number of faculty vacancies, by school, that have

occurred or been filled by the defendants since the order of this

Court or the latest report submitted pursuant to this subparagraph.

This report shall state the race of the teacher employed to fill

each such vacancy and indicate whether such teacher is newly

employed or was transferred from within the system. The tabulation

of the number of transfers within the system shall indicate the

schools from which and to which the transfers were made. The

report shall also set forth the number of faculty members of each

race assigned to each school for the current year.

(iii) The number of students by race, in each grade of each

school.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG JAMES M. NABRIT, III

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E. H. GADSDEN458% W. Broad Street

Savannah, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

Ralph Stell, et al.

22

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that the undersigned, one of the attorneys

for appellants, served a copy of the foregoing Supplemental Brief

for Appellants upon Basil Morris, Esq., P.0. Box 396, Savannah,

Georgia, and Honorable E. Freeman Leverett. Deputy Assistant

Attorney General, State of Georgia, Elberton, Georgia, attorneys

for appellees? R. Carter Pittman, Esq., P. 0. Box 891, Dalton,

Georgia, and J. Walter Cowart, Esq., 504 American Building,

Savannah, Georgia, attorneys for appellees-intervenors? and

Brian K. Landsberg, Esq., Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.,

attorney for appellant United States of America, by mailing copies

to them at the above addresses via the United States air mail,

postage prepaid.

Done this 5th day of October, 1967.

Attorney for Appellants

Ralph Stell, et al.