Bakke v. Regents Motion for Leave to File and Supplemental Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1977 - November 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Motion for Leave to File and Supplemental Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1977. fe41d759-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a66f603d-d84c-4655-ae7c-4fae4f90fb62/bakke-v-regents-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-supplemental-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

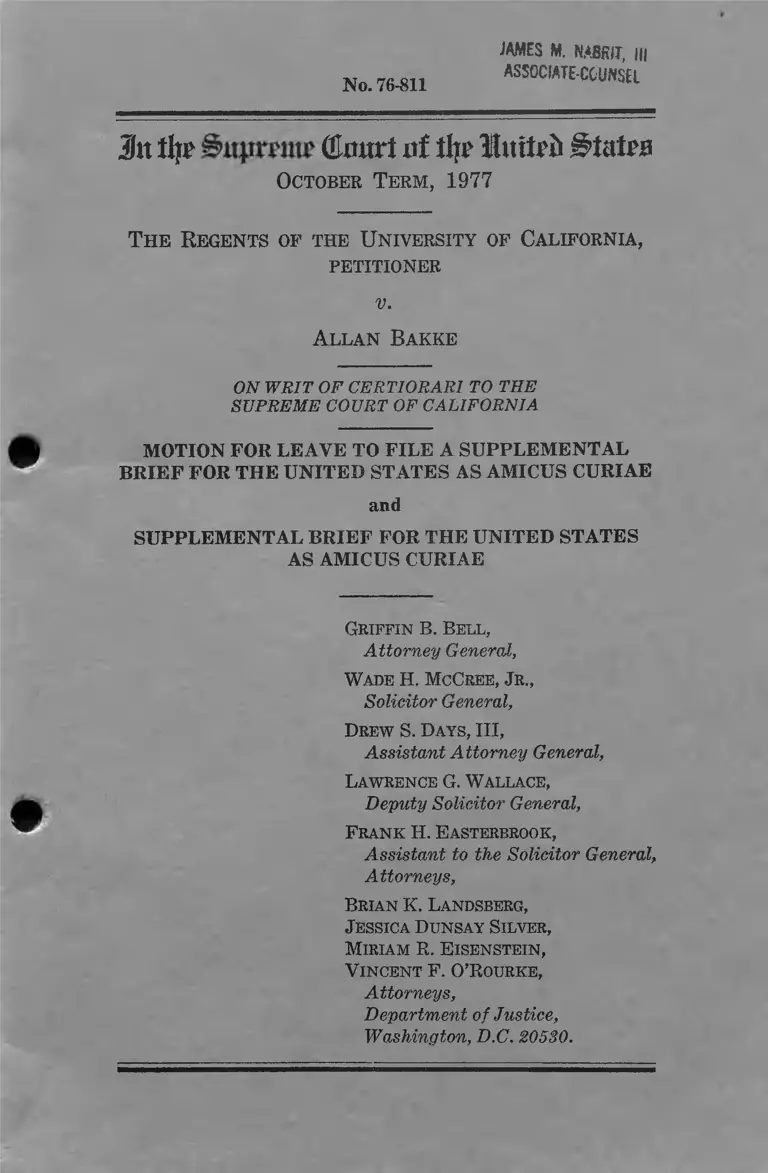

No. 76-811

JAMES M. NABfiJT, HI

ASSOCIATE-COUNSEL

Jit % (tart of % 'MnlUh ̂ tatM

October T erm , 1977

T h e R egents of the U niversity of California ,

PETITIONER

V.

A llan Bakke

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A SUPPLEMENTAL

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

and

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Gkiffin B. Bell,

Attorney General,

Wade H. McCree, J r.,

Solicitor General,

Drew S. Days, III,

Assistant Attorney General,

Lawrence G. Wallace,

Deputy Solicitor General,

Frank H. E asterbrook,

Assistant to the Solicitor General,

Attorneys,

Brian K. Landsberg,

J essica Dunsay Silver,

Miriam R. E isenstein,

Vincent F. O’Rourke,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C. 20530.

I N D E X

Page

Statement _______________________________ 1

Introduction and summary of argum en t_____ 3

Argument _______________________________ 7

I. A minority-sensitive program tailored to

overcome the effects of past discrimina

tion does not violate Title VI _______ 7

A. The legislative history shows that

Title VI was designed to assist

minority persons in obtaining the

benefits of federally-assisted pro

grams ____ 8

B. Parallel anti-discrimination provi

sions permit the use of minority-

sensitive criteria _________ ,______ 11

C. Federal regulations interpreting

Title VI endorse minority-conscious

programs _____________________ 15

D. Developments after the passage of

Title VI demonstrate that it does

not prohibit properly designed af

firmative action programs ___ 19

II. Private persons may sue to enforce the

anti-discrimination provision of Title

VI ________________________________ 24

Conclusion ------------------- 34

II

CITATIONS

Cases: Page

Adams v. Richardson, 480 F.2d 1159........ 32

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 ______________________________ 6,12,14

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393

U.S. 544 _________________________ 6,27,28

Anderson v. San Francisco Unified School

District, 357 F. Supp. 248 ____ 15

Associated General Contractors of Cali

fornia v. Secretary of Commerce, C.D.

Cal., No. C.A. 77-3738, decided Novem

ber 2, 1977 ________________________ 23

Bossier Parish School Board v. Lemon,

370 F.2d 847, certiorari denied, 388

U.S. 911 ___________________ _____ 24,32

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 ___ _ 4

Bradley v. School Board of the City of

Richmond, 416 U.S. 696 ____________ 34

Brown v. Pitchess, 13 Cal. 3d 518, 119

Cal. Rptr. 204, 531 P.2d 772 _____.... . 34

Califano v. Sanders, 430 U.S. 99 ____ _______ 19

Campbell v. Kruse, No. 76-1704, decided

October 3, 1977 ____________________ 33

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 559 F.2d

1063 ______________________________ 24, 33

Cardinale v. Louisiana, 394 U.S. 437 __ 4, 5, 25

Constructors Association of Western

Pennsylvania v. Kreps, W.D. Pa., No.

C.A. 77-1035, decided October 13, 1977,

appeal pending, C.A. 3, No. 77-2335 23

Cort v. Ash, 422 U.S. 6 6 ____ _____ ____ 31, 32

Evans v. Lynn, 537 F.2d 571, certiorari

denied sub nom. Evans v. Hills, 429

U.S. 1066 28

Cases—Continued

hi

Page

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 ______ 34

Flanagan v. President and Directors of

Georgetown College, 417 F. Supp. 377_. 15, 24

Florida East Coast Chapter of the Asso

ciated General Contractors of America

v. Secretary of Commerce, S.D. Fla.,

No. 77-8351-CIV-JE, decided Novem

ber 3, 1977 ___________________ _- - 23

Gautreaux v. Romney, 448 F.2d 731 .... „ 32, 33

Hanker son v. North Carolina, No. 75-

6568, decided June 17, 1977 ________ 3

Hazelwood School District v. United

States, No. 76-255, decided June 27,

1977 ______________________________ 13

Heart of A tlanta Motel, Inc. v. United

States, 379 U.S. 241 _______________ 8

International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, No. 75-636, decided

May 31, 1977 __ ______________10

Jefferson v. Hackney, 406 U.S. 535 ____..... 10, 25

Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 __ 8

Langnes v. Green, 282 U.S. 531 3

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 ____3, 6, 7,10,14,

15,25,26

Laufman v. Oakley Building & Loan Co.,

408 F. Supp. 489 ___________ __ - 24

Lear, Inc. v. Adkins, 395 U.S. 653 ....... 4

Linmark Associates, Inc. v. Township of

Willingboro, 431 U.S. 85 . ____ ___..._ 14

Marin City Council v. Marin County Re

development Agency, 416 F. Supp. 707 24

Massachusetts v. Westcott, 431 U.S. 322 4, 25

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transporta

tion Co., 427 U.S. 273 ______________ 5

IV

Cases—Continued Page

McGoldrick v. Compagnie Generate Trans-

atlantique, 309 U.S. 430 ___________ 5, 25

Miree v. DeKalb County, No. 76-607, de

cided June 21, 1977 ...............—.......—. 26

Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225 _______ 34

Montana Contractors’ Association v.

Kreps, D. Mont., No. C.A. 77-62-M,

decided November 7, 1977 __________ 23

Mt. Healthy City School District Board of

Education v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 _____ 25

Natonabah v. Board of Education, 355 F.

Supp. 716 _________ 24

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc.,

390 U.S. 400 ______________________ 27, 34

Otero v. New Yoi'k City Housing Author

ity, 484 F.2d 1122 _________________ 15

Piper v. Chris-Craft Industries, Inc., 430

U.S. 1 _______________ 32

Rosado v. Wyman, 397 U.S. 397 — 29

Securities Investor Protection Corp. v.

Barbour, 421 U.S. 4 1 2 ______________ 28

Simon v. Eastern Kentucky Welfare

Rights Organization, 426 U.S. 26 ____ 28

Singleton v. Wulff, 428 U.S. 106 _______ 25

Southern Christian Leadership Confer

ence, Inc. v. Connolly, 331 F. Supp.

940 _______________________________ 24

Strong v. Strong, 22 Cal. 2d 540, 140

P.2d 386 _ ...._____________________ - 31

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1 ......... .......... .... 14

United Jewish Organizations of Williams-

burgh, Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 7,13,14

V

Cases—Continued Page

United States v. Jefferson County Board

of Education, 372 F.2d 836, affirmed

en banc, 380 F.2d 385, certiorari de

nied sub nom. Caddo Parish School

Board v. United States, 389 U.S. 840 _ 10

Uzzell v. Friday, 547 F.2d 801 -------------- 15, 24

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 ------- 10

Williams v. Horvath, 16 Cal. 3d 834, 129

Cal. Rptr. 453, 548 P.2d 1125 _______ 34

Constitution, statutes and regulations:

United States Constitution:

Fourteenth Amendment 1, 2, 3, 10, 15, 35

California Constitution, Privileges and

Immunities Clause -------------------------- 1, 2

Civil Rights Act of 1964:

Title VI, 78 Stat. 252, 42 U.S.C.

2000d et seq. __________________ passim

Section 601, 42 U.S.C. 2000d _ passim

Section 602, 42 U.S.C. 2000d-l „ 9, 11,

15,28, 29, 30

Section 604, 42 U.S.C. 200Gd-3 12

Title VII, 78 Stat. 253, 42 U.S.C.

2000e et seq. ______________ 5,12,19

Section 703, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2 12

Section 703(a), 42 U.S.C. 2000e-

2 (a) ______ 12

Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act,

Pub. L. 94-559, 90 Stat. 2641, 42 U.S.C.

(1976 ed.) 1988 32

VI

Constitution, statutes and

regulations—Continued Page

Education Amendments of 1976, Pub. L.

94-482, 90 Stat. 2233, adding Section

440(c) to the General Education Provi

sions Act, 20 U.S.C. (1976 ed.) 1231i

(c) ----------------------------------------------- 21

Local Public Works Capital Development

and Investment Act of 1976, Pub. L. 94-

369, 90 Stat. 999, as amended _______ 22

Section 106, 42 U.S.C. (1976 ed.)

6705 _______________________ ... 23

Section 106(f) (2), 91 Stat. 117 ...... „ 23

Section 110, 42 U.S.C. (1976 ed.)

6709 __________________________ 22-23

Public Works Employment Act of 1977,

Pub. L. 95-28, Section 103, 91 Stat. 116-

117 _______________________________ 23

Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504,

87 Stat. 394, 29 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 794__ 33

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 79 Stat. 437,

42 U.S.C. 1973 ____________________ 13

81 Stat. 787 __________________________ 32

84 Stat. 121___ ___________ _________ __ 32

28 U.S.C. 1257 _____________________ 4

5 C.F.R. 900.404(b) (6) ______ 17

7 C.F.R. 15.3(b) (6) _________ _______ 17

10 C.F.R. 4.12(f) _ 17

12 C.F.R. 529.4(b) (6) ________ __ 17

13 C.F.R. 112.3(b) (3) 17

14 C.F.R. 379.3(b) (3) _______ 17

14 C.F.R. 1250.103-2 (e) ........... ........ 17

15 C.F.R. 8.4(b) (6) _________________ 17

18 C.F.R. 302.3(b) (6) _______________ 17

VII

Constitution, statutes and

regulations—Continued Page

18 C.F.R. 705.4(b) (5) _______________ 17

22 C.F.R. 141.3(b) (5) .... ______ 17

22 C.F.R. 209.4(b) (6) ______________ 17

24 C.F.R. 1.4(b) (6) ___ 17

28 C.F.R. 42.104(b)(6) _________ 17

28 C.F.R. 42.406 _________ - - - - - - - - 14

29 C.F.R. 31.3(b) (6) ____ ___________ 17

32 C.F.R. 300.4(b)(4) _______ .. -..- 17

32 C.F.R. 1704.5(f) (1974 rev.) ______ 17

38 C.F.R. 18.3(b)(6) _______________ 17

40 C.F.R. 7.5 _______________________ 17

41 C.F.R. 101-6.204-2(a) (4) __________ 17

43 C.F.R. 17.3(b)(4) ____________ 17

45 C.F.R. 80.3(b)(2) __________ 14

45 C.F.R. 80.3(b) (6) __________ ___ ~~ 16,17

45 C.F.R. 80.3(b) (6) (i) ______ _ ____ 16

45 C.F.R. 80.3(b) (6) (ii) _____________ 16

45 C.F.R. 80.5 (j) ____________________ 17

45 C.F.R. 611.3(b) (6) ________ 17

45 C.F.R. 1010.4(b) (6) .. 17

45 C.F.R. 1110.3(b) (6) _. 17

45 C.F.R. 1203.4(b)(4) _____ 17

49 C.F.R. 21.5(b) (7) ..... ........ ...... 17

Miscellaneous:

Comment, The Philadelphia Plan: A Study

in the Dynamics of Executive Power, 39

U. Chi. L. Rev. 723 (1972) _____ 19-20

49 Comp. Gen. 59 (1969) _ — 19

110 Cong. Rec. (1964):

p. 2464 _________________________ 32

p. 2467 _____________________ - 9,32

VIII

Miscellaneous—Continued Page

p. 5090 ____________ 29

p. 5243 __________________________ 9

p. 6049 ___________ 29

p. 6051 __________________________ 32

p. 6544 __________________________ 9

p. 6546 __________________________ 11

p. 7054 _______________ 10

pp. 7060-7061 ___________________ 29

p. 7062 ____________________ __- ... - 9

p. 7064 _______ 29

p. 13700 __... . _________________ 11

p. 13876 _________________________ 32

117 Cong. Rec. (1971):

p. 31981_________________________ 20

p. 31984 _________________________ 20

p. 32111 _________________________ 20

122 Cong. Rec. (daily ed., May 12, 1976):

p. H4316 ________________________ 20

p. H4317 ________________________ 20

122 Cong. Rec. (daily ed., September 21,

1976):

p. HI 2159 . ___ 33

p. H12164 ______________________ 33

p. H12165 ____ 33

p. S16251 ______________________ 33

123 Cong. Rec. (daily ed., June 17, 1977):

p. H6099 _______________________ 21, 22

p. H6103 _ . . . ____ 21

p. H6106 ______ 22

22

19

15

31

16

16

18

17

18

14

21

11

19

33

3-4

IX

Miscellaneous—Continued

123 Cong. Rec. H8330 (daily ed., Au

gust 2, 1977) --------- ----------------------

Executive Order 11246, 30 Fed. Reg.

12319, as amended by Executive Order

11375, 32 Fed. Reg. 14303 ________

Executive Order 11764, 39 Fed. Reg.

2575 ______________________ _______

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule

8(c) -------------------------- -----------------

36 Fed. Reg. 23448 __________________

36 Fed. Reg. 23448-23512 __ __________

36 Fed. Reg. 23494 __________________

38 Fed. Reg. 17919-17997 ........ ........

38 Fed. Reg. 17978 .......... .....................------

41 Fed. Reg. 52669 et seq. ... . . . . .-------

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 94-1701, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1976) -----------------------------

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1963) ____________ ________________

42 Op. A tt’y Gen. No. 37 (1969) _

S. Rep. No. 93-1297, 93d Cong., 2d Sess.

(1974) ____________________________

Stern, When to Cross-Appeal or Cross-

Petition— Certainty or Confusion?, 87

Harv. L. Rev. 763 (1974) ... —

Jin tip (Hmtrt itf tiff Imtffr i>tatf3

October Term, 1977

No. 76-811

The Regents of the University of California,

PETITIONER

v.

Allan Bakke

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A SUPPLEMENTAL

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

On October 17, 1977, this Court ordered the parties

to file “a supplemental brief discussing title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as it applies to this

case.” The United States moves for leave to file a

supplemental brief as amicus curiae to address that

question.

The United States has substantial responsibility

for enforcing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

78 Stat. 252, 42 U.S.C. 2000d to 20Q0d-4. Title VI

requires “ | ejach Federal department and agency

which is empowered to extend Federal financial as

sistance to any program or activity” (42 U.S.C.

200Qd-l) to ensure that recipients of federal funds

do not discriminate “on the ground of race, color, or

( X )

national origin” in any program (42 U.S.C. 2000d).

Title VI authorizes federal agencies to withhold funds

from non-complying recipients, and 27 agencies have

issued regulations addressed to the relationship be

tween affirmative action programs and this enforce

ment responsibility.

The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare,

which provides funds for the Medical School a t Davis,

has issued regulations (45 C.F.R. 80.3(b) (6) (ii) and

80.5( j ) ) approving minority-sensitive efforts to over

come the effects of conditions that have resulted in

limiting the participation of persons of particular

races in federally-assisted programs. The validity of

these regulations as an interpretation of Title VI

could be directly affected by this case, as could the

validity of the regulations of many other federal

agencies.

The Court permitted the United States to file a

brief as amicus curiae and to participate in the oral

argument of this case. Because of the unique federal

responsibility for construing and enforcing Title VI,

the United States has an interest, in addition to the

interest described at pages 1-3 of our main brief, in

the Court’s resolution of the question it has asked the

parties to address. The Court therefore should grant

leave for the United States to file this supplemental

brief.

Respectfully submitted.

Wade H. McCeee, J r.,

Solicitor General.

November 1977.

3u % g>ityrrmi> ( ta r t of % lotted

October Term, 1977

No. 76-811

The Regents of the University of California,

PETITIONER

V.

Allan Bakke

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE

STATEMENT

This statement of facts supplements the statement

a t pages 3-22 of our main brief.

Respondent’s complaint stated (A. 2-3) that his

claim for relief was founded on the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United

States Constitution, the Privileges and Immunities

Clause of the California Constitution, and Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.1 Petitioner pleaded,

1 The complaint erroneously refers to Title VI as “the Fed

eral Civil Rights Act (42 U.S.C. sec. 200 (d).) ” (A. 3), but the

intent of the pleading is clear.

( 1 )

as an affirmative defense (A. 7), that its special ad

missions program is consistent with Title VI. Peti

tioner filed a cross-complaint for declaratory relief.

It sought a declaratory judgment that the special

admissions program was proper, and it alleged (A.

10-11) that an “actual controversy has arisen and

now exists” between the parties “relating to whether

the special admissions program * * * violates * * *

the federal Civil Rights Act (42 U.S.C. § 2000(d)).”

The trial court found (Pet. App. 114a), as peti

tioner had admitted (A. 5, 9), that the University

received federal assistance. I t held that the special

admissions program violated not only the Fourteenth

Amendment and the California Constitution but also

Title VI (Pet. App. 112a, 117a, 118a). The court

entered a judgment declaring that “the special ad

missions program at the University of California at

Davis Medical School violates the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution, Article 1,

Section 21 of the California Constitution, and the

Federal Civil Rights Act [42 U.S.C. § 2000(d)]”

(Pet. App. 120a; bracketed material in original).

On appeal in the Supreme Court of California,

petitioner discussed Title VI and urged that that

statute, as interpreted by regulations issued by the

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, per

mits admissions programs such as the special admis

sions program at the Medical School (see Br. 34-35).

Respondent did not separately discuss Title VI, noting

(Br. 14 n. 1) that it did not require further treat-

3

ment because it “in many ways parallels the four

teenth amendment.”

The Supreme Court of California characterized re

spondent’s contention as an argument that the spe

cial admissions program violated the Equal Protec

tion Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; the court

stated that petitioner’s cross-complaint sought a de

claratory judgment that the “program was valid”

(Pet. App. 3a). The court’s decision rested entirely

on the Fourteenth Amendment (id. a t 37a), and it

mentioned Title VI only in passing (id. a t 13a n. 10).2

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The threshold question here is whether this Court

could or should decide whether Title VI either pro

hibits or authorizes the special admissions program.

The Supreme Court of California did not pass on

that question, petitioner did not present any Title VI

issue in the petition, and respondent’s brief did not

rely on Title VI as a distinct ground for affirmance

of the judgment.

The customary rule is that a “respondent may make

any argument presented below that supports the

judgment of the lower court.” Hankerson v. North

Carolina, No. 75-6568, decided June 17, 1977, slip op.

6 n. 6. See Langnes v. Green, 282 U.S. 531; Stern,

When to Cross-Appeal or Cross-Petition— Certainty

2 The court simply mentioned that Lau V. Nichols, 414 U.S.

563, had been decided under Title YI.

4

or Confusion?, 87 Harv. L. Rev. 763 (1974).3 The

Court has reached statutory issues that were pre

sented (and decided) in the state courts, but not in

this Court, when that would allow it to pretermit

resolution of difficult constitutional questions. See,

e.g., Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454, 457. I t also

has decided federal statutory issues that were not

reached by state courts in light of their disposition

of other federal issues. See Lear, Inc. v. Adkins, 395

U.S. 653; id. a t 678 (White, J., concurring in part).

The Title VI question was presented to the California

courts, and they had an opportunity to resolve it. We

therefore believe that this Court has the authority to

decide this case on Title VI grounds.

Considerations of prudence and respect for state

courts, and the limitations on review under 28 U.S.C.

1257, however, suggest that in many cases this Court

should allow state courts to consider issues before

this Court undertakes to do so. For example, in

Massachusetts v. Westcott, 431 U.S. 322, the Supreme

Judicial Court of Massachusetts had held that a state

statute was invalid under the United States Constitu

tion. This Court vacated that judgment and remanded

the case to allow the state court to consider whether

its decision also could rest upon federal statutory

grounds.4 Remanding for further consideration of the

3 See also pages 16-19 of our brief in United States v. New

York Telephone Co., No. 76-835, argued October 3, 1977. We

have furnished copies of that brief to counsel for the parties to

this case.

4 See also Cardinale v. Louisiana, 394 U.S. 437, 439 (state

courts must be given the “first opportunity” to address a

5

federal statutory issues is, similarly, an available

option here.

On the assumption that the Court has decided to

consider the Title VI question in the present case, we

tu rn to a discussion of the issues that question

raises. As a preliminary matter, we believe that

Title VI protects white persons as well as all other

persons. See McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transpor

tation Co., 427 U.S. 273, 278-285 (Title VII of the

same statute prohibits discrimination against mem

bers of any racial group). But this is only the be

ginning of the inquiry because, as the Court observed

(427 U.S. a t 281 n. 8), that case did not involve any

question concerning the propriety under the statute

of an affirmative action program.

federal question, and a question not raised in state court there

fore cannot be decided by this Court on certiorari); McGoldrick

V. Compagnie Generate Transatlantique, 309 U.S. 430, 434-435

(“due regard for the appropriate relationship of this Court to

state courts requires us to decline to consider and decide ques

tions affecting the validity of state statutes not urged or con

sidered there [, and] * * * error is not to be predicated upon

their failure to decide questions not presented”). Although

some of the discussion in McGoldrick may be taken as stating

that this Court will not consider issues that the state court did

not actually decide, we believe that the more accurate conclu

sion is that this Court has the power to pass on issues that

were either presented to or decided by the state court. Any

other conclusion would allow the state courts to compel this

Court to decide particular issues, even though prudence might

counsel disposing of the case on other grounds. As we read

Cardinale and McGoldrick, the only jurisdictional requirement

is that the federal issue sought to be raised here have been

presented to or decided by the state courts.

6

A logical precondition to respondent’s reliance on

Title VI is a conclusion that Title VI creates a claim

for relief enforceable by private parties. No provi

sion of Title VI explicitly authorizes private suits,

and this Court has not decided whether they may be

maintained, although Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563,

awarded relief to private plaintiffs in a suit to en

force Title VI. For the reasons we discuss a t pages

26-34, infra, we believe that Title VI does create

judicially-enforceable private claims, for the same

reason that other civil rights statutes do so. See, e.g.,

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 555-

557. Because the propriety of a private action to

enforce the provisions of Title VI is not a jurisdic

tional question, however, the failure of either peti

tioner or respondent to present the issue to the state

courts precludes consideration of it now.

We discuss the substantive meaning of Title VI at

pages 7-23, infra. The legislative history of that

statute reveals no hostility to voluntary plans of in

tegration. Title VI was designed to assist black

persons, and others often excluded from federally-

assisted programs, to receive the benefits of those

programs. There is no support for a conclusion that

Title VI bans minority-sensitive decisions that would

assist in achieving this objective.

This Court has held that a parallel prohibition in

Title VII of the same statute sometimes requires con

sideration of race in making employment decisions.

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405. I t has

held that a prohibition against discrimination in ap-

7

portionment of legislative districts does not prohibit

consideration of race in bringing about fa ir apportion

ments. United Jewish Organizations of Williams-

burgh, Inc, v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144. Similarly, Title

VI does not prohibit the employment of minority-

sensitive criteria in order to overcome the lingering

consequences of past discrimination and to prevent

the Medical School from denying to minority appli

cants equal opportunity for a federally-assisted medi

cal education.

Any doubt of this is resolved by the regulations

issued by the many federal agencies intei preting

Title VI. Congress instructed the agencies to issue

interpretive regulations, and they are entitled to

great deference. Lau v. Nichols, supra, 414 U.S. at

566-569 (opinion of the Court), 571 (Stewart, J.,

concurring). The regulations issued by the Depart

ment of Health, Education, and Welfare approve vol

untary affirmative action designed to include minority

persons in the programs of recipients of federal

money.

ARGUMENT

I

A MINORITY-SENSITIVE PROGRAM TAILORED TO

OVERCOME THE EFFECTS OF PAST DISCRIMINA

TION DOES NOT VIOLATE TITLE VI

Section 601 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78

Stat. 252, 42 U.S.C. 2000d, provides:

No person in the United States shall, on the

ground of race, color, or national origin, be ex-

8

eluded from participation in, be denied the bene

fits of, or be subjected to discrimination under

any program or activity receiving Federal fi

nancial assistance.

Respondent has argued that this provision forbids

affirmative action programs, including the special ad

missions program at the Medical School, because

they “exclude” applicants on racial grounds. We

argued in our principal brief (Br. 30-65) that the

Constitution does not bar the Medical School from

taking race into account in order fairly to compare

minority and non-minority applicants. We now sub

mit that Title VI does not prohibit the Medical School

from employing a minority-sensitive program that

the Constitution would permit.

A. The Legislative History Shows That Title VI Was

Designed to Assist Minority Persons in Obtaining the

Benefits of Federally-Assisted Programs

Title VI was part of a sweeping package of re

medial measures designed to eliminate racial dis

crimination from much of society. See generally

Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States, 379

U.S. 241; Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294.

Title II forbade discrimination in public accommo

dations, Title VII in employment. The Act as a whole

was intended to deal with the discrimination against

black persons then pervasive in our society, discrimi

nation depriving them of the “rights, privileges, and

opportunities which are considered to be, and must

be, the birthright of all citizens.” H.R. Rep. No. 914,

88th Cong., 1st Sess. 18 (1963).

9

At the time the Act was being considered, blacks

often were denied the benefits of programs supported

with federal funds. Title VI was designed to put an

end to federal support of discrimination and to assure

to blacks “the right to access” to federally-assisted

programs. 110 Cong. Rec. 5243 (1964) (statement of

Senator C lark).5 Representative Celler, the Chair

man of the House Judiciary Committee and the prin

cipal House proponent of Title VI, stated (id. at

2467) that:

[ i] t seems rather shocking * * * that while we

have on the one hand the 14th amendment,

which is supposed to do away with discrimina

tion since it provides for equal protection of the

laws, on the other hand, we have the Federal

government aiding and abetting those who per

sist in practicing racial discrimination.

Congress recognized that private suits were making

some progress in opening opportunities to racial

minority groups; it sought, in Title VI, to expedite

that progress both by explicitly declaring in Section

601 that discrimination was forbidden and by creat

ing, in Section 602, 42 U.S.C. 2000d-l, the remedy of

terminating federal funds for programs that contin-

5 Senator Pastore, Senate floor manager for Title VI, ex

plained: “ [T] itle VI is simply designed to insure that Federal

funds are spent in accordance with the Constitution and

our public policy” (110 Cong. Rec. 7062 (1964)). Senator

Humphrey, Senate floor manager for the entire bill, expressed

a similar view. 110 Cong. Rec. 6544 (1964). (The language

of Section 601 that is relevant here remained the same in con

sideration by both the House and Senate.)

ued to practice discrimination. See, e.g., 110 Cong.

Rec. 7054 (1964) (remarks of Senator P asto re);

see also United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 372 F.2d 836, 853 (C.A. 5), affirmed en

banc, 380 F.2d 385, certiorari denied sub nom. Caddo

Parish School Board v. United States, 389 U.S. 840.

Title VI thus was designed to strengthen enforce

ment of the constitutional guarantee of treatment of

all persons as equals, and it applied that guarantee

to federally-assisted programs whether or not the

recipients of the federal money were state bodies

directly subject to the Fourteenth Amendment. Con

gress sought to afford the full constitutional protec

tion to all intended beneficiaries of federal assist

ance.6 Title VI, which opened the doors of federal

programs to minority applicants who were formerly

excluded, should not be interpreted to close those

doors when the recipients of federal assistance have

voluntarily implemented affirmative action programs

that are consistent with the Constitution.

6 This case does not present the question whether Title VI

and the Constitution treat differently state programs that have

a racially disproportionate impact. The special admissions

program deliberately used racial criteria, and any differences

between intentional discrimination and disproportionate effect

do not require consideration here. Compare Lau V. Nichols,

414 U.S. 563, 568, with Jefferson V. Hackney, 406 U.S. 535,

549-550 n. 19. See also Washington V. Davis, 426 U.S. 229;

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, No.

75-636, decided May 31, 1977, slip op. 9 n. 15. This case in

volves only the question whether a conceded resort to race is

justified, and for that purpose it makes no difference whether

disproportionate impact is enough to establish a prima facie

case of violation of Title VI.

11

Indeed, Title VI was intended to induce voluntary

achievement of the objective of equal treatment. See,

e.g., H.R. Rep. No. 914, supra, a t 18; 110 Cong. Rec.

13700 (1964) (remarks of Senator P astu re); id. at

6546 (remarks of Senator Humphrey). The proviso

of Section 602 requiring each federal agency to seek

voluntary compliance before resorting to coercive en

forcement exemplifies this objective. For the reasons

we have discussed in our main brief, voluntary efforts

to overcome the effects of prior discrimination often

will entail use of minority-sensitive criteria. If Title

VI were understood to bar voluntary use of minority-

sensitive criteria to deal with the lingering conse

quences of prior discrimination, it would effectively

prohibit recipients of federal funds from opening

their programs to the formerly-excluded groups:—in

other words, to prohibit voluntary use of minority

sensitive criteria would be, in many cases, to prohibit

recipients of federal funds from achieving the major

objective of Title VI.7

B. Parallel Anti-Discrimination Provisions Permit the

Use of Minority-Sensitive Criteria

Section 601 prohibits “exclusion” of persons, and

other discrimination, “on the ground of race, color,

7 It would defeat the purpose of the statute—to open fed

erally-assisted programs to persons of all races—if recipients

could not attempt to deal with the lingering effects of discrimi

nation elsewhere in society that was hindering participation

by some groups in the programs. See pages 38-40 of our main

brief. Title VI therefore does not prohibit voluntary efforts

to overcome the consequences of discrimination by third

parties.

12

or national origin * * The cognate provision of

Title VII of the same statute, 42 U.S.C. 20Q0e-2,

makes it unlawful for an employer “to fail or refuse

to hire” any applicant “because of such individual’s

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin * *

These statutes have a similar effect; “excluding”

someone from the benefits of a program is not mate

rially different from not hiring that person and

thereby denying him the benefits of employment; dis

crimination “on the ground of” race is not materially

different from discrimination “because of” race. It

therefore is significant that the Court has upheld

the use of racial criteria in making employment deci

sions, when that is necessary to ensure that the em

ployer’s decisions are not racially biased. Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 425. If Title VII

permits (and, in some cases, requires) appropriate

consideration of race in making employment deci

sions, Title VI permits appropriate resort to minor

ity-sensitive criteria in making decisions about ad

mission to medical school.8

8 Title VI also applies to employment decisions by certain

programs receiving federal funds. Compare Section 604, 42

U.S.C. 2000d-3 (no employment decision is covered by Title VI

unless “a primary objective of the Federal financial assistance

is to provide employment”) with Section 703(a), 42 U.S.C.

2000e-2 (a) (employment discrimination is unlawful). It seems

unlikely that Congress would have intended Title VI and Title

VII to establish different standards for assessing the legality

of minority-sensitive decisions and thereby forbidden, in fed

eral programs that have a primary objective to provide em

ployment, employment decisions that would be permitted under

Title VII.

13

The Voting Eights Act of 1965 also contains a

provision barring any voting procedure or qualifica

tion that denies or abridges “the right of any citizen

of the United States to vote on account of race or

color” (79 Stat. 437, 42 U.S.C. 1973). This statute,

too, permits officials to take race into account in order

to make decisions that ultimately are evenhanded;

the State may take race into account in order to

apportion legislative districts in a way that fairly

represents the voting strength of different racial and

ethnic groups. United Jewish Organizations of WU-

liamsburgk, Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144. If volun

tary remedial use of race is permitted under the Vot

ing Rights Act, nothing less should be permitted un

der Title VI.

Moreover, whether or not Title VI prohibits prac

tices that have a racially disparate effect in the ab

sence of a racial motive,9 the statute surely allows

administrators of federally-assisted programs to be

suspicious when their practices result in a racial com

position for their program that does not fairly reflect

the racial composition of the pool of potential appli

cants.10 Administrators who observe such a racial

9 See note 6, swpra.

10 Petitioner has not argued that the admissions program at

the Medical School during its first two years violated Title VI

because of its disproportionate exclusion of minority appli

cants, and the present record would not permit an investiga

tion of that question. See Hazelwood School District V. United

States, No. 76-255, decided June 27, 1977 (study of relevant

population or applicant groups necessary to determine whether

statistical information about hiring rate establishes discrimi-

14

disproportion—as the Medical School experienced dur

ing its first two years (see page 9 of our main

brief)—should be entitled to take steps to overcome

whatever factors are contributing to that result. That,

we believe, is the meaning of Albemarle and United

Jewish Organizations: the federal civil rights laws,

designed to make programs meaningfully open to

minority applicants, do not prohibit the steps neces

sary to achieve that result. Indeed, federal regula

tions prohibit a recipient of funds from “u tiliz ing ]

criteria or methods of administration which have the

effect of subjecting individuals to discrimination be

cause of their race, color, or national origin, or have

the effect of defeating or substantially impairing ac

complishment of the objectives of the program as re

spect individuals of a particular race, color, or na

tional origin.” 45 C.F.R. 80.3(b) (2 ).11

The elimination of racial separation is an im

portant governmental objective. Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 16;

Linmark Associates, Inc. v. Township of Willingboro,

431 U.S. 85, 94-95. I t would require strong evidence,

evidence missing from either the structure or the leg

islative history of Title VI, to support the conclusion

that Congress has inhibited state agencies from volun-

nation); 41 Fed. Reg. 52669 et seq., to be codified at 28 C.F.R.

42.406 (Department of Justice Title VI regulations requiring

the collection of relevant population data by race).

11 This Court applied that regulation in Lau v. Nichols,

supra, in holding that a neutrally-applied school board policy

of providing instruction only in English violated the rights of

Chinese-speaking students under Title VI.

15

tarily endeavoring, in a way consistent with the Con

stitution, to attain that objective.12

C. Federal Regulations Interpreting Title VI Endorse

Minority-Conscious Programs

Section 602, 42 U.S.C. 2000d-l, requires federal

agencies to promulgate regulations interpreting Title

VI. These regulations, which are required to be ap

proved by the President,13 are entitled to the greatest

respect as guides to the meaning of Title VI. Lau

v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563, 566-569 (opinion of the

Court), 571 (Stewart, J., concurring). The regula

tions remove any doubt about the proper interpreta

tion of Title VI.

The Department of Health, Education, and Wel

fare, which provides most of the federal assistance to

institutions of higher education, has adopted regula-

12 The lower courts have reached divergent, but not neces

sarily mutually inconsistent, results under Title VI. See TJzzell

V. Friday, 547 F.2d 801 (C.A. 4) (Title VI prohibits racial

allotments of membership of student government and student

honor court); Otero V. New York City Housing Authority, 484

F.2d 1122 (C.A. 2) (Title VI permits consideration of race to

promote integration); Flanagan V. President and Directors of

Georgetown College, 417 F. Supp. 377 (D. D.C.) (Title VI pro

hibits allotment of scholarship funds by race but may permit

consideration of race in making admissions decisions); Ander

son V. San Francisco Unified School District, 357 F. Supp. 248

(N.D. Cal.) (Fourteenth Amendment and Title VI prohibit

preference for minority group members in choosing school

administrators).

13 By Executive Order 11764, dated January 21, 1974, 39

Fed. Reg. 2575, the President delegated this authoirty to the

Attorney General. This delegation took place after the adop

tion of most of the regulations referred to in this brief.

16

tions providing that recipients of assistance that

have previously engaged in racial discrimination must

undertake “affirmative action to overcome the effects”

of that discrimination. 45 C.F.R. 80.3(b) (6) (i). The

regulations also provide that, even in the absence

of prior discrimination, a recipient of federal funds

“may take affirmative action to overcome the effects

of conditions which resulted in limiting participation

[in the program!] by persons of a particular race,

color, or national origin.” 45 C.F.R. 80.3(b) (6) (ii) .14

14 Twenty-six other federal agencies have adopted regula

tions substantially identical to 45 C.F.R. 80.3(b)(6). The

similarity of the regulations represents a considered decision

by the Executive Branch.

An interagency committee recommended to the President

the uniform adoption of the following amendment to the Title

VI regulations of Federal agencies (36 Fed. Reg. 23448):

This regulation does not prohibit the consideration of race,

color, or national origin if the purpose and effect are to

remove or overcome the consequences of practices or

impediments which have restricted the availability of, or

participation in, the program or activity receiving Fed

eral financial assistance, on the grounds of race, color, or

national origin. Where previous discriminatory practice

or usage tends, on the grounds of race, color, or national

origin, to exclude individuals from participation in, to

deny them the benefits of, or to subject them to discrimi

nation under any program or activity to which this regu

lation applies, the applicant or recipient has an obligation

to take reasonable action to remove or overcome the con

sequences of the prior discriminatory practice or usage,

and to accomplish the purposes of the Act.

This and a number of other proposed amendments were pub

lished on December 9, 1971, as proposed regulations for 21

agencies. 36 Fed. Reg. 23448-23512.

The original 21 agencies and four others adopted, with

presidential approval, a regulation including either the lan-

17

The regulations provide an illustration to demon

strate the meaning of this latter provision. 45 C.F.R.

80.5(j) provides:

guage originally suggested or a modification. The Department

of Health, Education, and Welfare adopted the modified lan

guage discussed in the text; this language was intended to

clarify the responsibilities of educational institutions, not to

change the substance of the provision. The final regulations

were published on July 5, 1973. 38 Fed. Reg. 17919-17997.

The agencies included: Civil Service Commission, 5 C.F.R.

900.404(b) (6); Department of Agriculture, 7 C.F.R. 15.3(b)

(6); Atomic Energy Commission (now Nuclear Regulatory

Commission), 10 C.F.R. 4.12(f); Federal Home Loan Bank

Board, 12 C.F.R. 529.4(b) (6); Small Business Administration,

13 C.F.R. 112.3(b)(3); Civil Aeronautics Board, 14 C.F.R.

379.3(b) (3); National Aeronautics and Space Administration,

14 C.F.R. 1250.103-2 (e); Department of Commerce, 15 C.F.R.

8.4(b)(6); Tennessee Valley Authority, 18 C.F.R. 302.3(b)

(6); Department of State, 22 C.F.R. 141.3(b) (5); Agency for

International Development, 22 C.F.R. 209.4(b)(6); Depart

ment of Housing and Urban Development, 24 C.F.R. 1.4(b)

(6); Department of Justice, 28 C.F.R. 42.104(b) (6); Depart

ment of Labor, 29 C.F.R. 31.3(b) (6); Department of Defense,

32 C.F.R. 300.4(b) (4); Office of Emergency Preparedness, 32

C.F.R. 1704.5(f) (1974 rev.); Veterans Administration, 38

C.F.R. 18.3(b)(6); Environmental Protection Agency, 40

C.F.R. 7.5; General Services Administration, 41 C.F.R. 101-

6.204-2 (a) (4); Department of the Interior, 43 C.F.R. 17.3(b)

(4); Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 45 C.F.R.

80.3(b) (6); National Science Foundation, 45 C.F.R. 611.3(b)

(6); Office of Economic Opportunity (now Community Serv

ices Administration), 45 C.F.R. 1010.4(b) (6); National Foun

dation on the Arts and Humanities, 45 C.F.R. 1110.3(b) (6);

Department of Transportation, 49 C.F.R. 21.5(b) (7). Regula

tions have since been adopted by ACTION, 45 C.F.R. 1203.4

(b)(4), and the Water Resources Council, 18 C.F.R. 705.4

(b)(5).

18

Even though an applicant or recipient has

never used discriminatory policies, the services

and benefits of the program or activity it ad

ministers may not in fact be equally available

to some racial or nationality groups. In such cir

cumstances, an applicant or recipient may prop

erly give special consideration to race, color, or

national origin to make the benefits of its pro

gram more widely available to such groups, not

then being adequately served. For example, where

a university is not adequately serving members

of a particular racial or nationality group, it

may establish special recruitment policies to ™

make its program better known and more readily

available to such group, and take other steps to

provide that group with more adequate service.

The Department of Health, Education, and Wel

fare has interpreted these regulations, and with them

Title VI, as permitting consideration of race in

the university admissions, process because minority-

sensitive admissions criteria are a means to achieve

a more thorough and fa ir consideration of minority

applicants. See 38 Fed. Reg. 17978. These regula

tions, adopted “to make services more equitably avail

able” (36 Fed. Reg. 23494), are consistent with the f h

purpose of Title VI and should be sustained.15

15 Some employment decisions also are covered by Title VI

(see note 8, supra), and enforcement in these circumstances is

governed by the Policy Statement of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Coordinating Council (see Appendix C to our

main brief). This statement encourages “voluntary affirma

tive action * * * to achieve equal employment opportunity”

19

D. Developments After the Passage of Title VI Demon

strate That it Does Not Prohibit Properly Designed

Affirmative Action Programs

The propriety of affirmative action programs has

been a m atter of considerable congressional debate in

the years since Title VI was enacted. Attempts

have been made to prohibit or limit such programs,

and all of these attempts have been unsuccessful.

The fate of these attempts, gives some indication about

the meaning of Title VI. Cf. Calijano v. Sanders,

430 U.S. 99.

As our main brief discussed, perhaps the most

prominent affirmative action program was established

by Executive Order 11246, 30 Fed. Reg. 12319, as

amended by Executive Order 11375, 32 Fed. Reg.

14303, which required federal contractors to take

affirmative action to counteract disproportionately low

employment of racial minorities. The Comptroller

General concluded that this program was unlawful

under Titles VI and VII. 49 Comp. Gen. 59 (1969).

The Attorney General, on the other hand, issued an

opinion stating that the program was lawful. 42 Op.

A tt’y Gen. No. 37 (1969). The Comptroller Gen

eral then urged Congress to enact legislation that

would override the Executive Order; after lengthy

consideration by Congress, his request was rejected.

See Comment, The Philadelphia Plan: A Study in the

(id. at 5A), and this Policy Statement therefore offers further

support for the conclusion that Title VI does not prohibit

properly designed affirmative action programs.

20

Dynamics of Executive Power, 39 U. Chi. L. Rev.

723, 748-750 (1972).

The controversy was revived in 1972, when Con

gress thoroughly reconsidered the existing civil rights

legislation. Representative Dent proposed an amend

ment that would have transferred jurisdiction of the

executive order program and forbidden any “prefer

ential treatm ent” of persons of any race (see 117

Cong. Rec. 31981, 31984 (1971). The amendment

was defeated (id. a t 32111). In the Senate several

proposals were made and defeated; the proposals and

arguments are discussed in Comment, supra, a t 754-

757.

In 1976 issue was joined once more. Representa

tive Eshleman offered an amendment to the General

Education Provisions Act that would have barred the

Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare from

requiring “the imposition of quotas, goals, or any

other numerical requirements on the student admis

sion practice of an institution of higher education

* * * receiving Federal funds” (122 Cong. Rec.

H4316 (daily ed., May 12, 1976)). Representative

Chisholm objected that this amendment would bar

effective remedies for established racial discrimina

tion, and Representative Eshleman replied (id. at

H4316) that “ [t]his amendment is in no way aimed

a t [remedies for racial discrimination].” The House

adopted the amendment (id. a t H4317).

The Senate bill had no comparable provision, and

the Conference Committee resolved the difference by

modifying the legislation to provide that “ [ i] t shall

21

be unlawful for the Secretary to defer or limit any

Federal financial assistance on the basis of any fail

ure to comply with the imposition of quotas (or any

other numerical requirements which have the effect of

imposing quotas) on the student admission practices

of an institution of higher education * * The stat

ute, as so amended, was enacted. Education Amend

ments of 1976, Pub. L. 94-482, 90 Stat. 2233, adding

Section 440(c) to the General Education Provisions

Act, 20 U.S.C. (1976 ed.) 1231i(c). Thus the statute

ultimately enacted did not prohibit goals or time

tables ; moreover, it is significant that the statute ap

plied only to programs required by the federal gov

ernment, rather than to programs voluntarily adopted.

Congress therefore concluded, at least by negative im

plication, that minority-sensitive programs employing

goals and timetables do not violate Title VI.1'6

The present Congress also has considered the pro

priety of minority-sensitive programs. Representative

Levitas proposed an amendment to an appropriations

bill that, in the words of Representative Ashbrook,

would have limited the federal government’s ability

“to initiate, carry out or enforce any program of

affirmative action” (123 Cong. Rec. H6099 (daily

16 The Conference Committee stated that the amended lan

guage took no position on the question whether the Secretary

of Health, Education, and Welfare could withhold federal

funds because an institution of higher learning declined to

adopt goals or timetables. H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 94-1701, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. 243 (1976). This reservation did not pertain,

however, to the lawfulness of voluntarily-adopted minority-

sensitive programs.

22

ed., June 17, 1977)). The proposed amendment was

itself amended until it provided only that no “ratio,

quota, or other numerical requirement related to

race” could be required as a condition of federal fund

ing; the bill then was passed by the House {id. at

H6106). Representative Levitas explained that the

bill meant “simply that no numerical quotas can be in

volved and, beyond that, goals, timetables, affirmative

action, can all be implemented” {id. a t H6103). Rep

resentative Ashbrook stated {id. a t H6099) that if a

“university wants to enact a program of this type,

wants to have [an affirmative action] office, that

would be their individual right, but this [amendment]

would prevent the Government from being able to

force them.” Once more, Congress acted on the as

sumption that voluntary affirmative action programs

do not violate Title VI.”

At the same time, Congress enacted legislation in

dicating that affirmative action is not inconsistent

with the goal of the elimination of discrimination.

The Local Public Works Capital Development and

Investment Act of 1976, Pub. L. 94-369, Section 110,

90 Stat. 1002, includes a provision that bars discrimi-

17 There was no comparable provision in the Senate bill,

and the Conference Committee has deleted the House provision

because it was excessively restrictive. The Senate Conferees

relied, in part, on a letter from the Secretary of Health, Educa

tion, and Welfare objecting to the provision. See 128 Cong.

Rec. H8330 (daily ed., August 2, 1977) (remarks of Repre

sentative Flood). The entire appropriations measure has not

been reported back by the Conference Committee, however,

because of a disagreement about the provision of federal funds

to pay for abortions.

28

nation on the ground of sex and provides that com

pliance with the non-discrimination provision shall be

enforced through the administrative machinery estab

lished “with respect to racial and other discrimina

tion” under Title VI. 42 U.S.C. (1976 ed.) 6709. On

May 13, 1977, the President signed the Public Works

Employment Act of 1977, Pub. L. 95-28, 91 Stat. 116-

117. Section 103 of the 1977 statute adds subsection

(f) (2) to Section 106 of the 1976 Act, 42 U.S.C.

(1976 ed.) 6705, to require, among other things, that no

grant shall be made “unless the applicant gives satis

factory assurance * * * that a t least 10 per centum of

the amount of each grant shall be expended for

minority business enterprises.” The passage of this

provision, in light of congressional recognition of the

applicability of Title VI to projects funded under the

Act, indicates that, in the view of Congress, affirma

tive action is consistent with the prohibition against

discrimination contained in Title VI.1S

18 The constitutionality of Section 103 is currently being liti

gated in a number of suits. See, e.g., Constructors Association

of Western Pennsylvania V. Kreps, W.D. Pa., No. C.A. 77-

1035, decided October 13, 1977 (plaintiff’s motion for prelimi

nary injunction denied), appeal pending, C.A. 3, No. 77-2335;

Associated General Contractors of California v. Secretary of

Commerce, C.D. Cal., No. C.A. 77-3738, decided November 2,

1977 (plaintiffs’ request for declaratory and injunctive relief

granted in p a rt); Montana Contractors’ Association V. Kreps,

D. Mont., No. C.A. 77-62-M, decided November 7, 1977 (plain

tiffs’ motion for preliminary injunction denied); Florida East

Coast Chapter of the Associated General Contractors of Amer

ica V. Secretary of Commerce, S.D. Fla., No. 77-8351-CIV-JE,

decided November 3, 1977 (plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary

injunction denied).

PRIVATE PERSONS MAY SUE TO ENFORCE THE

ANTIDISCRIMINATION PROVISION OF TITLE VI

A. The Title VI issue was raised by respondent’s

initial pleading. Title VI does not, however, explicitly

provide for private enforcement of its terms, and it

could be argued that the provision in Section 602 for

government enforcement implicitly precludes private

suits.19 Although the United States submits that pri

vate persons may bring suit to enforce Title VI, we

believe that the question is not open in this case.

The question whether there is a private cause of

action to enforce Title VI was not raised or litigated

in the state courts. Although respondent relied on

Title VI, petitioner did not argue that Title VI may

not be enforced in private suits; to the contrary,

19 One court of appeals, in the course of holding that private

persons may not bring suits to enforce Title IX of the Educa

tion Amendments of 1972, has indicated that Title VI does not

permit private suits either. Cannon V. University of Chicago,

559 F.2d 1063 (C.A. 7). Other courts, however, have either held

or assumed that Title VI establishes a private right of action.

See, e.g., Uzzell V. Friday, 547 F.2d 801 (C.A. 4); Bossier

Parish School Board V. Lemon, 370 F.2d 847 (C.A. 5), cer

tiorari denied, 388 U.S. 911; Flanagan V. President and Direc

tors of Georgetown College, 417 F. Supp. 377 (D. D.C.); Lauf-

man V. Oakley Building & Loan Co., 408 F. Supp. 489, 498-499

(S.D. Ohio); Natonabah v. Board of Education, 355 F. Supp.

716, 724 (D. N.M.). Cf. Marin City Council V. Marin County

Redevelopment Agency, 416 F. Supp. 707, 709 n. 4 (N.D. Cal.);

Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Inc. V. Connolly,

331 F. Supp. 940 (S.D. Mich.).

25

petitioner pleaded that there is an “actual contro

versy” between the parties concerning the lawfulness

of the special admissions program under Title VI

(A. 10) and sought a declaratory judgment that the

program was lawful. Petitioner thus abandoned any

argument that the Title VI issues may not be raised

by a private plaintiff.

On review of a decision of a state court, this Court

may not reach issues that were neither presented to

nor decided by the state courts. Compare Massachu

setts v. Westcott, 431 U.S. 322, with Cardinale v.

Louisiana, 394 U.S. 437, and McGoldrick v. Com-

pagnie Generate Transatlantique, 309 U.S. 430. Cf.

Singleton v. Wulff, 428 U.S. 106, 119-121.

It would be necessary to decide the question whether

private plaintiffs may bring suit to enforce Title VI

only if that question were “jurisdictional.” See, e,g.,

ML Healthy City School District Board of Education

v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274, 278-279. But the question is

not jurisdictional; this Court twice has reached the

merits of a Title VI question in a private suit with

out discussing the ability of a private plaintiff to raise

Title VI questions, a course that would have been in

appropriate if the question were jurisdictional. See

Lau v. Nichols, supra; Jefferson v. Hackney, 406

U.S. 535, 549-550 n. 19.

Even if the question were open, this would be an

inappropriate case in which to resolve it. Private

rights of action to enforce Title VI might be viewed

in three ways. First, they might be seen as rights

“implied” from the purpose and structure of Title VI

26

and therefore authorized by Title VI itself; in that

event the case would present only issues of federal

law. Second, they might be seen as suits by third

party beneficiaries of the contracts between the fed

eral agencies and the recipients of the federal fu n d s;20

in that event the terms of the grant would be federal,

but the right to recover might depend on state law.

See Miree v. DeKalb County, No. 76-607, decided

June 21, 1977 (suit by air crash victims as third

party beneficiaries of federal airport safety grant is

governed by state law). Issues of this sort would

turn on provisions of state law that have not been

discussed at any time in this litigation and that could

not be resolved by this Court. Third, because this

suit was commenced in state court, there is a possi

bility that state law might confer a right of action

to enforce Section 601 even if no suit could be brought

in federal court. This question, too, involves state law

issues that this Court could not resolve. These differ

ent approaches complicate the question and require

careful consideration in the lower courts.

Nevertheless, the issue was raised by petitioner at

oral argument (Tr. 23), and, out of an abundance of

caution, we briefly present our views on the first of

these approaches, the existence of an implied federal

cause of action.

B. 1. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, like Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, provides that no

person shall be discriminated against because of race.

20 See Lou V. Nichols, supra, 414 U.S. at 571 n. 2 (Stewart, J.,

concurring).

27

The Voting Rights Act, like Title VI, does not ex

plicitly provide for private actions to enforce its

terms. This Court held that private persons may

bring suit to enforce the personal rights conferred

on them by the Voting Rights Act, I t reasoned that

“ [t]he achievement of the Act’s laudable goal could

be severely hampered * * * if each citizen were re

quired to depend solely on litigation instituted at the

discretion of the Attorney General.” Allen v. State

Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 556. The Court

found it significant that the Voting Rights Act ap

plied to large numbers of political subdivisions, and

that the great number of potential violators made it

infeasible for a single Department of the Executive

Branch to police all of the jurisdictions subject to

the Act.

The same reasoning applies to Title VI. Great

numbers of federally-assisted programs are subject to

the requirements of Section 601, and it is unrealistic

to suppose that the agencies of the Executive Branch

will be able to detect all violations of the statute or to

commence enforcement proceedings whenever they de

tect a violation. “When the Civil Rights Act of 1964

was passed, it was evident that enforcement would

prove difficult and that the Nation would have to rely

in part upon private litigation as a means of securing

broad compliance with the law.” Newman v. Piggie

Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 401. Private

suits to enforce the Civil Rights Act of 1964 are an

indispensible complement to enforcement initiated by

the Executive Branch. The statute “might well prove

28

an empty promise unless the private citizen were

allowed to seek judicial enforcement” (Allen, supra,

393 U.S. a t 557).21

2. The strongest argument against allowing pri

vate suits to enforce Section 601 is that Congress

established in Section 602 an elaborate mechanism for

governmental enforcement by federal agencies. The

structure of Title VI, however, cuts against a conclu

sion that the establishment of administrative enforce

ment methods precludes private judicial enforcement.

Section 601 creates personal rights. I t provides

that “,[n]o person in the United States shall, on the

ground of race, * * * be excluded” from participation

in any federally-assisted program. The rights cre

ated by Section 601 run in favor of every person.

Congress could as easily have provided that: “No pro

gram discriminating on account of race shall receive

federal funds.” If it had expressed the prohibition in

that way, there would be a strong argument that per

sons such as respondent could not bring suit.22 But

the statute actually enacted was fa r broader; it in

structs recipients of federal money not to discrimi

nate. I t was designed to end discrimination, not sim-

21 See also Securities Investor Protection Corp. v. Barbour,

421 U.S. 412, 424-425 (it was necessary to recognize a private

right of action under the Voting Rights Act because it could

not be fully enforced “against the many local governments

subject to its strictures” if only the Attorney General could

sue).

22 Cf. Simon V. Eastern Kentucky Welfare Rights Organiza

tion, 426 U.S. 26; Evans V. Lynn, 537 F.2d 571 (C.A. 2) (en

banc), certiorari denied sub nom. Evans V. Hills, 429 U.S.

1066.

29

ply to allocate federal money to programs that did not

discriminate.23 Private suits will be valuable in achiev

ing the statute’s goal.24

A private action is especially useful in light of the

practical limitations on the scope of administrative re

lief under Section 602. That provision allows federal

agencies to terminate the funding of programs that

practice unlawful discrimination, but only if “compli

ance cannot be secured by voluntary means.” The

remedy available under Section 602 is essentially pros

pective ; a program that has discriminated in the past

may continue to receive federal funds if it desists

from doing so in the future and takes the steps neces

sary to come into compliance with the statute. Al

though future compliance would include, in many

cases, rectifying the effects of past discrimination, as

a practical m atter this process may not afford effective

relief to individual victims of unlawful discrimination.

23 See, e.g., 110 Cong. Rec. 6049, 7060-7061 (1964) (re

marks of Senator Pastore); id. at 5090 (remarks of Senator

Humphrey); id. at 7064 (remarks of Senator Ribieoff).

24 See also Rosado V. Wyman, 397 U.S. 397. Rosado was a

private suit brought to challenge the state administration of a

welfare program. The State pointed out that the federal stat

ute granting funds to state welfare programs did not authorize

a private action, and it argued that termination of funds was

the exclusive remedy. This Court disagreed. It concluded that

private plaintiffs could seek to enforce the substantive require

ments of the federal statute, explaining (397 U.S. at 420) that

“ [w] e are most reluctant to assume Congress has closed the

avenue of effective judicial review to those individuals most

directly affected by the administration of its program.”

30

A private action would supplement the administra

tive process by serving as an additional deterrent to

violations before they take place, and it would enable

individual victims of discrimination to be made whole.

A private action would secure to the intended benefi

ciaries of Section 601 the full rights Congress gave

them. Once programs have accepted federal funds,

they incur the obligation not to discriminate; private

actions would serve most usefully to enforce that obli

gation for the years in which funds already have been

received, while governmental enforcement under Sec

tion 602 serves as a practical m atter principally to

bring about compliance in the future.25

Respondent seeks relief for acts during 1973 and

1974, years in which petitioner accepted federal

funds. Those funds cannot be repaid to the federal

government, and any termination of funds in the

future would be unlikely to have an effect on re-

25 Even the grant of an injunction or a declaratory judgment

in a private action would not be inconsistent with the adminis

trative program established by Section 602. The judgment

would simply declare the duties of the program so long as it

desired to retain the benefit of federal funding. The recipient

then would be free to decide whether to continue to accept

funds, and it could proceed with the negotiations contemplated

by Section 602 to define the contours of compliance. A declara

tory judgment or injunction against future discrimination

would not raise the possibility that funds would be terminated,

and it would not involve bringing the forces of the Executive

Branch to bear on state programs; it therefore would not im

plicate the concerns that led to the limitations contained in

Section 602.

A separate question is presented by the fact that Section 602

contemplates administrative remedies. Although it could be

31

spondent. If, as he maintains, respondent has been

denied lights secured by Section 601, a private action

is essential.26

3. Cort v. Ash, 422 U.S. 66, also indicates that a

private party may seek to enforce Title VI. Under

that case, a court must consider four questions (422

U.S. a t 78):

First, is the plaintiff “one of the class for whose

especial benefit the statute was enacted” * * *—

that is, does the statute create a federal right in

favor of the plaintiff? Second, is there any indi

cation of legislative intent, explicit or implicit,

either to create such a remedy or to deny one?

* * * Third, is it consistent with the underlying

purposes of the legislative scheme to imply such a

remedy for the plaintiff? * * * And finally, is

the cause of action one traditionally relegated to

state law, in an area basically the concern of the

States, so that it would be inappropriate to infer

a cause of action based solely on federal law?

argued that this creates a requirement of administrative ex

haustion before a private person seeks judicial relief, this is

an inappropriate case in which to consider that question. Re

spondent filed an administrative complaint (R. 278-281), and

petitioner has not argued that it was prejudiced in any way by

the treatment of this complaint.

26 This case does not present any question concerning the

period within which private suits must be filed. Reliance on a

period of limitations is an affirmative defense, and, at least in

the federal courts, it is waived if not pleaded in the answer to

the complaint. Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(c). In California, too, the

defense of limitations is waived if not pleaded. Strong v.

Strong, 22 Cal. 2d 540, 140 P.2d 386. This Court therefore

need not consider whether the complaint in this case was

timely.

32

See also Piper v. Chris-Cmft Industries, Inc., 430

U.S. 1, 37-41.

Section 601 creates a right in favor of all potential

beneficiaries of federally-assisted programs ; this satis

fies the first Corf test. There is no contemporaneous

legislative history concerning private actions, al

though there was an inconclusive discussion on the

question whether private persons could bring suit

to require federal officials to terminate funding for

programs that continued to engage in discrimination.27

It is more significant, however, that Congress

enacted statutes bearing on Title VI twice after the

Fifth Circuit’s decision holding that private persons

could bring suit to enforce Section 601.28 See 84 Stat.

121; 81 Stat. 787. Congress left the Fifth Circuit’s

decision undisturbed. And in 1976 Congress enacted

the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act, Pub. L.

94-559, 90 Stat. 2641, 42 U.S.C. (1976 ed.) 1988,

which authorizes courts to grant attorney’s fees to the

prevailing party in any action brought to enforce,

27 Compare 110 Cong. Rec. 6051 (1964) (remarks of Senator

Johnson), and id. at 2464 (remarks of Representative Poff),

with id. at 2467 (remarks of Representative Gill), and id. at

13876 (remarks of Senator Ervin). Two courts have held that

such suits may be maintained. Adams v. Richardson, 480

F.2d 1159 (C.A.D.C.) (en banc); Gautreaux v. Romney, 448

F.2d 731 (C.A. 7) (by implication).

28 Bossier Parish School Board v. Lemon, swpra.

29 Many of the supporters of the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees

Awards Act explicitly stated that attorney’s fees would assist

private plaintiffs in maintaining actions under Title VI. See,

33

among other civil rights statutes, Section 601.2,9 These

congressional actions appear to have ratified the Fifth

Circuit’s early decision.30

e.g., 122 Cong. Rec. S16251 (daily ed., September 21,1976) (re

marks of Senator Scott); id. at H12159 (remarks of Rep

resentative Drinan); id. at H12164 (remarks of Representa

tive Holtzman); id. at H12165 (remarks of Representative

Seiberling). The Seventh Circuit—which itself had recognized

in Gautreaux v. Romney, supra, the propriety of private suits

to enforce Section 601—has argued that the Civil Rights

Attorney’s Fees Awards Act does not demonstrate congres

sional support of private actions. See Gannon v. University

of Chicago, supra, 559 F.2d at 1078-1080. It acknowledged

that some Members of Congress believed that private suits

were authorized, but it pointed to other statements in which

Representatives stated that the new legislation did not im

plicitly authorize private actions. We agree with the Seventh

Circuit that the Attorney’s Fees Awards Act did not create a

“new” cause of action; we rely on it here only to demonstrate

that many Members of Congress assumed that it already ex

isted, and to show that Congress has not indicated that a pri

vate cause of action is inconsistent in any way with the plan of

Title VI.

30 In dealing with related issues Congress has assumed with

out question that Title VI established a private right of action.

For example, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973,

87 Stat. 394, 29 U.S.C. (Supp. V) 794, provides that no

handicapped person “shall, solely by reason of his handicap,

be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits

of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or

activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” This provision

closely tracks the language of Section 601. It was inserted in

the statute with the expectation that it “would * * * permit a

judicial remedy through a private action.” S. Rep. No. 93-1297,

93d Cong., 2d Sess. 40 (1974). This Court has instructed a

lower federal court to reach the merits of a private suit brought

under Section 504. Campbell V. Kruse, No. 76-1704, decided

October 3, 1977. The clear intent of Congress to create a pri-

34

It is “consistent with the underlying purposes of”

Title VI to permit private suits; for the reasons we

have already discussed, private suits are an essential

aid in enforcing civil rights statutes, because individ

ual violations are likely to be too numerous to be

dealt with effectively by agency enforcement alone.

Congress authorized attorney’s fees in private suits in

recognition of that fact. See Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, Inc., supra; Bradley v. School Board of

the City of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696.

Finally, enforcement of the right to be free from

unlawful discrimination on account of race is not “tra

ditionally relegated to state law.” To the contrary,

the rights conferred by Section 601 are preeminently

federal.131 See Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445;

Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225.

CONCLUSION

We conclude, therefore, that respondent may main

tain this private suit to enforce Title VI. For the

reasons we have discussed a t pages 7-23, supra, how