City of New York v. Richardson Complaint

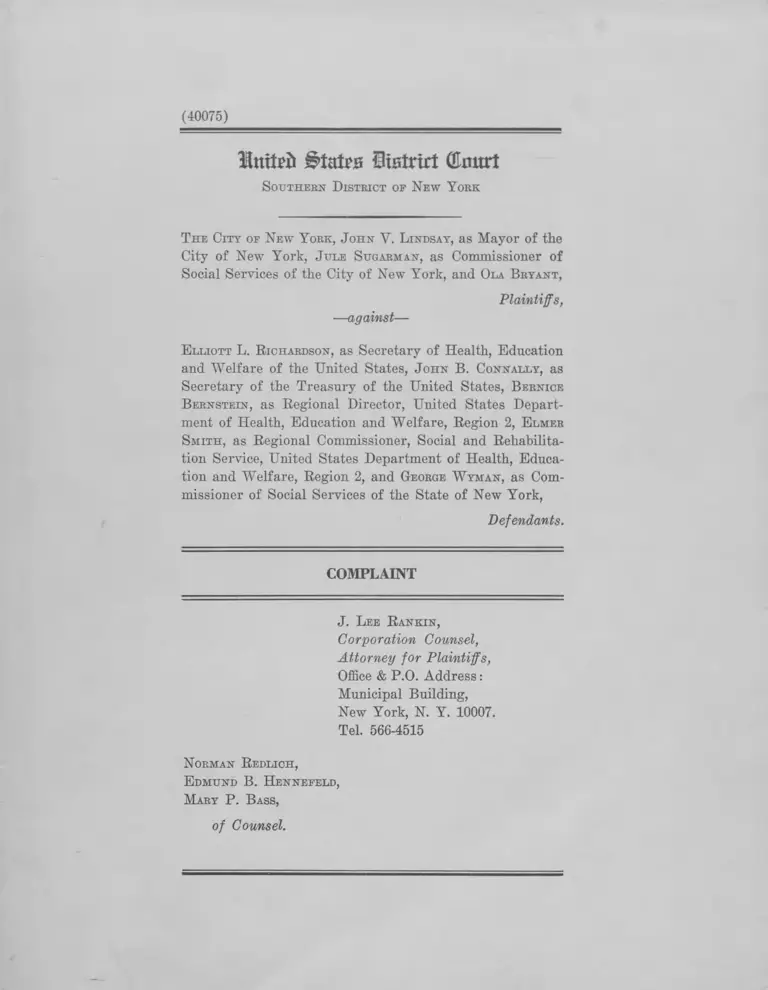

Public Court Documents

February 24, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of New York v. Richardson Complaint, 1971. 1b5cd970-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a670a4b1-fa6f-4dcf-a35b-b569c1445093/city-of-new-york-v-richardson-complaint. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

(40075)

Intteft Sistrtrt (Emtrl

Southern District of New Y ork

T he City of New Y ork, John V. L indsay, as Mayor of the

City of New York, Jule Sugarman, as Commissioner of

Social Services of the City of New York, and Ola Bryant,

—ay ains t—

Plaintiffs,

E lliott L. Richardson, as Secretary of Health, Education

and Welfare of the United States, John B. Connally, as

Secretary of the Treasury of the United States, Bernice

B ernstein, as Regional Director, United States Depart

ment of Health, Education and Welfare, Region 2, E lmer

Smith, as Regional Commissioner, Social and Rehabilita

tion Service, United States Department of Health, Educa

tion and Welfare, Region 2, and George W yman, as Com

missioner of Social Services of the State of New York,

Defendants.

COMPLAINT

J. Lee Rankin,

Corporation Counsel,

Attorney for Plaintiffs,

Office & P.O. Address:

Municipal Building,

New York, N. Y. 10007.

Tel. 566-4515

Norman Redlich,

E dmund B. Hennefeld,

Mary P. Bass,

of Counsel.

llntteii Sistrirt (Emtrl

Southern District of N ew Y ork

The City of New Y ork, John V. L indsay, as Mayor of the

City of New York, Jule Sugarman, as Commissioner of

Social Services of the City of New York, and Ola Bryant,

—against—

Plaintiffs,

E lliott L. Richardson, as Secretary of Health, Education

and Welfare of the United States, John B. Connally, as

Secretary of the Treasury of the United States, B ernice

Bernstein, as Regional Director, United States Depart

ment of Health, Education and Welfare, Region 2, E lmer

Smith, as Regional Commissioner, Social and Rehabilita

tion Service, United States Department of Health, Educa

tion and Welfare, Region 2, and George W yman, as Com

missioner of Social Services of the State of New York,

Defendants.

COMPLAINT

Plaintiffs, complaining of the defendants, show to the

Court and allege as follows:

Jurisdiction

1. Jurisdiction is conferred on this Court under 28 U.S.C.

§1331 by the existence of a Federal question and the amount

in controversy.

(a) The action arises under the Constitution of the

United States, Article I, Section 8, Clause 1 (General Wei-

4

,4s and For a First Cause of Action in Favor of the Above-

Named Plaintiffs Against the Defendants Elliott L.

Richardson, Bernice Bernstein and Elmer Smith, as

Secretary, Regional Director and Regional Commis

sioner respectively of HEW, John R. Connally, as

Secretary of the Treasury, and George Wyman, as

Commissioner of Social Services of the State of New

York.

9. The problem of rendering public assistance to per

sons in need of such assistance, including but not limited

to the categories of aid to families with dependent children,

old-age assistance, medical assistance, aid to the blind and

aid to the disabled, in recent years but more especially so

in current times, has become one of national magnitude,

constituting in that regard a distinctively, if not exclusively

national problem:

(a) The number of persons in the United States, in

January 1970, receiving federally-aided public assistance

only, exclusive of medicaid, was 10,436,197, which was 5.1%

of the entire civilian resident population of 203,796,700.

Since that date, the total has increased. Approximately

fifteen million different people received medicaid benefits

during 1970. A table showing the figures first above-cited

is attached to, and made part of this complaint as Exhibit 1.*

* All tables, graphs and schedules hereinafter referred to

are identified by Exhibit Number, with the source indicated on

the face of the Exhibit.

(b) Nor is the problem a temporary or transient one.

In the twenty years from 1950 through 1969, the number

of recipients of money payments under public assistance

has increased each year to its present peak, as appears

from the following tabulation (Exhibit 2 ):

5

Number of Public

Year Assistance Recipients

1950 .......................................... 6,051,000

1951 .......................................... 5,627,000

1952 .......................................... 5,472,000

1953 .......................................... 5,433,000

1954 .......................................... 5,930,000

1955 .......................................... 5,818,000

1956 .......................................... 5,873,000

1957 .......................................... 6,282,000

1958 .......................................... 6,605,000

1959 .......................................... 6,877,000

1960 .......................................... 7,098,000

1961 .......................................... 7,356,000

1962 .......................................... 7,399,000

1963 .......................................... 7,515,000

1964 .......................................... 7,722,000

1965 .......................................... 7,802,000

1966 .......................................... 8,074,000

1967 .......................................... 8,893,000

1968 .......................................... 9,722,000

1969 .......................................... 11,131,000

(c) The aggregate dollar total of all public assistance

payments in the calendar year 1969 was $11,547,482,000

(Exhibit 3).

(d) The amount so expended in the year 1969 represents

the peak for all twenty years preceding, as appears from

the following table (Exhibit 3 ):

6

Tear Total

1950 .................. ............... $ 2,406,288,000

1951 .................. ............... 2,382,791,000

1952 .................. ............ 2,451,080,000

1953 .................. 2,539,879,000

1954 .................. 2,642,635,000

1955 .................. ............. 2,748,135,000

1956 .................. 2,853,070,000

1957 .................. 3,090,304,000

1958 .................. .......... 3,426,459,000

1959 .................. ........... 3,657,712,000

1960 .................. ....... 3,784,995,000

1961 ................. 4,098,867,000

1962 .................. ........... 4,437,107,000

1963 .................. ............ 4,712,572,000

1964 .................. ............... 5,072,577,000

1965 .................. ........... 5,476,025,000

1966 .................. ............... 6,313,134,000

1967 .................. ........... 7,804,377,000

1968 .................. ................ 9,768,276,000

1969 .................. ................ 11,547,482,000

For the year 1971, the corresponding aggregate dollar

total of such payments is anticipated to be substantially

higher.

(e) The problem of poverty and public assistance is not

confined to any particular region of the United States but

embraces every one of the fifty states of the union and the

District of Columbia (Exhibit 1).

(f) Under the standard of poverty defined by the Social

Security Administration of the Department of HEW, more

than 25,000,000 people in the United States are below the

poverty level as so defined. The composition of these

7

people so below the poverty level is made up disproportion

ately of non-whites, particularly so in the large metropol

itan centers. The influx of large numbers of these people,

mainly blacks, into the northern cities—a large percentage

of them with low levels both of formal education and the

type of skills needed for urban labor—has been due in

considerable degree to national policies and historical de

velopments over which the individual cities have had, and

continue to have no control. These have included agri

cultural policies which speeded mechanization of Southern

farms and drove sharecroppers and farm laborers from

the land, a series of wars which attracted workers to the

North for high-paying war work without any systematic

plan for their post-war employment, laxity in enforcing

civil rights against racial oppression in the South leading

millions to emigrate to the North as refugees from oppres

sion much as former waves came from Europe, and the

failure to do adequate national planning to encourage in

dustrialization of the South to absorb the surplus farm

labor.

These waves of migrants have been generally charac

terized by low levels of education, caused either by the

lack of adequate educational facilities in the home states

or by deprivation of the opportunity to enjoy those facil

ities by the policies and laws of the home states. But

since the job opportunities in the cities to which these

migrants have come require skills which can be obtained

only through education, the newcomers often remain un

employed. The cities, which have gone to great lengths

to provide adequate education to all segments of society

to prepare them for the available work opportunities, are

thus burdened Avith the responsibility of non-self-supporting,

incoming adults to whom this education could not have

been offered by the cities.

8

(g) Three major aspects of the enormous migration

wave which has altered the face of the nation for the

reasons stated above are: the general movement from

rural to urban areas, the movement to the cities and spe

cifically the northern cities of the black population, and

the disproportionate movement, again to the northern

cities, of the welfare population.

The general movement from rural to urban areas has

seen the number of urban dwellers increase from 41.9%

of the national population in 1900 to 64.4% in 1965 and

reached a level of 67% in 1970. This rate of movement is

an accelerating one.

The movement of blacks north and to the cities has

been even more accentuated. While the total black popu

lation more than doubled from 1910 to 1966, the number

living in cities rose five-fold (from 2.6 million to 14 mil

lion) and the number outside the South rose eleven-fold

(from 880,000 to 9,700,000). In the last decade, according

to the 1970 census, the central cities as a whole went

from 18% of black population to 23%. The suburbs re

main largely white: 38% of the whites in metropolitan

areas lived outside the central cities but only 16% of the

blacks did so. .Black migration has followed three avenues:

along the Atlantic seaboard north toward Boston; from

Mississippi north toward Chicago; and from Louisiana

and Texas west toward California. Between 1955 and

1960, 50% of non-white migrants to the New York metro

politan area came from North Carolina, South Carolina,

Virginia, Georgia and Alabama.

The movement of welfare recipients has shown a sim

ilar trend (Exhibit 7). Statistics on mothers receiving

aid to families with dependent children indicate their dis

proportionate migration to the industrial north. In New

York City, in 1968 for example, 78% of AFDC mothers

9

were born out of state, although only 37.2% of all women

there aged 25 to 29 were born out of state. This migration

was principally from the South Atlantic states and Puerto

Rico. Such migrations to a most significant extent have

been caused by factors outside the control of states and

localities.

Hand in hand with the concentration of poverty in the

hearts of the large cities, there has gone the concentra

tion of welfare burden and associated problems in the

same large metropolitan areas. The concentration of poor

persons in central cities, such as New York City, imposes

vast social and physical burdens on local governments, in

addition to the direct cost of welfare programs. For illus

tration, with approximately 1/7 of its population now on

welfare, New York City has a deteriorating inventory of

residential rental housing, the incomes of welfare recipi

ents being insufficient to provide the rental income neces

sary for adequate housing maintenance. In addition, a low-

income population with few technical skills and inadequate

educational background results in higher costs of educa

tion, health care, police and fire protection and sanitation.

(h) Expenditures per inhabitant for public assistance

have increased from $15.50 in the calendar year 1950 to

$56.35 in the calendar year 1969 (Exhibit 4). In the same

period, expenditures per inhabitant on aid to families

with dependent children has increased from $3.50 to $17.25

(Exhibit 4). The per recipient monthly aid to families

with dependent children in 1950 was $20.85, in 1967 $39.50

(Exhibit 5). Per family aid in the same category in 1950

was $71.45, in 1967 $161.70 (Exhibit 5). For the year 1971,

the corresponding figures are anticipated to be substan

tially higher.

(i) In September, 1970, 4,292,000 members of the total

civilian labor force of 82,547,000 were out of work, rep

10

resenting an unemployment rate of 5.2% (Exhibit 6).

There is no indication when this 4,292,000 of unemployed

people will be returned to work.

(j) While the unemployment rate rises, inflationary

forces continue to operate throughout the country. In

the single year from September of 1969 to September of

1970, the cost of living index rose from 129.3 to 136.6 for

all items, and from 146.0 to 157.7 for all services (Ex

hibit 6).

(k) The rapid increase in welfare costs in the past few

years has been significantly affected by national economic

policies, that is, policies formed and carried out by the

federal government. The economic recession has brought

people on to the welfare rolls, with particular burden on

the urban centers. In New York City, specifically, in 1970,

more than 31% of the increases in family cases in New

York City were directly traceable to loss of employment

and decrease in the number of cases closed in New York

City by reason of employment. This was twice the rate in

1969. Moreover, the inflation caused by national policies

has substantially raised the cost of living as reflected in

the consumer price index. The operating rate of the econo

my, and the amount of unemployment are essentially the

consequence of national policy.

(l) Concerning the national need and problem herein

above described, the President of the United States has

declared the following:

“One of the first steps in the review of the federal

system was to sort out those activities that are appro

priate for the Federal Government from those that are

best performed at the State and local level or in the

private sector. We decided early on one primary Fed

eral responsibility—providing, with a combination of

11

work incentives and work requirements, an income

floor for every American family.

My welfare reform proposals . . . are an integral

part of our effort to give people the ability to make

their own decisions, to build the capacity of state and

local government, and to encourage more orderly na

tional growth.”

President Nixon’s Budget Message, New York Times,

Jan. 30, 1971, p. 13, col. 4.

The National League of Cities has stated the following:

“Welfare in the United States is a national problem

requiring a national solution. Our present system of

public assistance has been found to contribute mate

rially to the tensions and social disorganization which

permeates many areas of our cities.”

The United States Conference of Mayors has similarly

declared the following:

“One of the priorities requiring immediate attention is

restructuring and modernizing the welfare system. We

call on Congress to adopt national standards with com

plete federal funding for the welfare program.”

# # #

“We need national assumption of [welfare] costs be

cause the welfare problem is national in origin and

national in solution.”

(m) The nature and size of the problem, so deeply con

nected with the “general Welfare” of the nation as a whole

and so requiring a unified national treatment, is such as

to demand planning and funding by the one body that can

give such systematic, national treatment—the Congress.

12

10. The plaintiff City of New York as of the date of this

complaint is, and for a number of years preceding has

been, in an intolerable financial and legal situation with

respect both to its public assistance requirements and

budgetary needs and resources. This situation is, and has

been, the result primarily of legal wrongs inflicted upon

the plaintiff City through the combined action of the federal

government, and officials thereof, and the government of

the State of New York and officials thereof.

a. Under the Social Security Act of 1935, 49 Stat. 620,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 301-1396g, the respective states,

including the State of New York, are reimbursed by the

federal government on a percentage basis applied to the

amount of public assistance expenditures made by the

state, in this instance, the State of New York. This reim

bursement is effected under a “ state plan” required by the

above-cited federal statute to be submitted by the State

to the Secretary of HEW, reviewed by that Secretary and,

if found satisfactory by him, approved by him. In particu

lar, in the case of the State of New York, that State has

heretofore submitted such a state plan to the Secretary of

HEW, and that Secretary has reviewed such state plan and

granted his approval thereof. From time to time, such

state plan has been amended in like manner.

b. The State of New York submitted the state plans

above referred to without prior consultation with the plain

tiff City of New York, without the approval or consent of

the plaintiff City obtained with respect thereto, and with

out the plaintiff City having the right to the review thereof

either administratively or in the courts. The federal stat

ute, 42 U.S.C. §1316, accords a right of review of the state

plan, but only to the respective states, and not to the

political subdivisions thereof. Subsequent to such approval

13

of the state plan by the Secretary of HEW, federal reim

bursement for public assistance expenditure in the State

and City of New York has been made based upon, and in

accordance with, the state plan as so submitted and ap

proved.

c. The legislature of the State of New York has enacted

a statute, the Social Services Law, which constitutes the

basis and foundation of the state plan. The effect of such

statute, including specifically Sections 62, 91, 92, 131, 131-a,

153, 356 and 368-a thereof, is to mandate the plaintiff City

of New York to bear roughly one-quarter of the cost of its

federally-aided gross expenditures for public assistance

payments in the social services district which it comprises,

and make the requisite impositions of tax and appropria

tions out of its budget to cover such one-quarter cost to

itself. From the gross expeditures by the City in the

federally-aided categories is deducted the amount of fed

eral reimbursement funds received on account of such ex

penditures. Fifty per cent of the difference is the amount

of the expenditure mandated upon, and to be borne wholly

by the plaintiff City, without further reimbursement or

contribution by the federal or state governments. The

effect, as stated, is to mandate the plaintiff City to bear,

pay, impose taxes with respect to, and provide in its

budget for approximately 25% of such federally-aided gross

expenditures.

d. The ultimate and final cost to the plaintiff City for

public assistance payments made by it for the year 1970,

based on a gross, over-all expenditure of $1,702,056,000

(including expenditure for home relief which is not feder

ally-aided) was $499,272,000. The corresponding figures

for the eleven years preceding are shown on the attached

table (Exhibit 8). The graph below shows the trend:

14

'58 '(>0 '62 '64 '*6 'is 17o

Year

e. With regard to the above-described, non-reimbursed

expenditures, the City of New York has been deprived of

any choice as to whether to make these expenditures. The

combined mandate of the federal and state governments,

assuming it to be valid, has been obligatory upon the

plaintiff City, without right of prior consultation or prior

approval with respect to such combined mandate, or right

of objection thereof, or review thereof.

f. On the other hand, the New York State Constitution,

in its Home Rule provisions, Article IX, Sections 1, 2 and

3, grants to the plaintiff City power, and at the same time

fastens upon it responsibilities, consistent with effective

local self-government and its nature and existence as a

municipality and metropolitan community.

15

11. In this situation of mandated public assistance ex

penditures, and at the same time prescribed municipal

functions and obligations, the plaintiff City of New York

has been limited in the extreme in the matter of its tax

and other revenue sources:

a. The power of the City to raise revenue based on real

estate taxes to meet operating expenses is circumscribed

by the State Constitution, Article 8, Section 10, to 2V^%

of the average full valuation of its taxable real estate.

b. The power of the City to impose non-property taxes

is limited to the taxes authorized by the state legislature

to be so imposed by the City.

c. The City is without power to finance its annual oper

ating budget by means of long-term indebtedness.

d. The City is unable to obtain substantial additional

revenues from such sources as the personal income or cor

porate income tax, or the sales tax. The federal and New

York State governments have effectively pre-empted to

themselves the major portion of the personal and corpo

rate income taxes. The extent of such pre-emption is illus

trated by the attached tables showing the rates of per

sonal income tax imposed by the Federal, New York State

and New York City governments, respectively (Exhibit 9).

A comparable situation exists with regard to other desir

able tax sources, such as represented by death and gift

taxes and the like.

e. Any increase in such taxes would accelerate the

existing migration of middle and high income persons

out of the city, thereby further narrowing the tax

base. Tabulation of the sources of revenue increases to

the three levels of government, federal, state and local

generally, over the 20-year period 1947-48 to 1967-68, shows

the comparative unavailability to the localities of such de

sirable tax sources (Exhibit 10). The rate of sales tax in

16

New York City is already unsurpassed by any state or

city.

12. In preparing and adopting its expense budget, the

plaintiff City is faced additionally with the difficulty that

under Social Services Law, Section 91, the plaintiff City

is mandated to appropriate the amount necessary for pub

lic expenditure made by it and to cause taxes to be levied

to cover the amount of the appropriation to the extent such

taxes are authorized by the State Constitution and legis

lation. The expenditure in question is required to be in

cluded in the expense budget without diminution or reduc

tion, with the result that any inadeqacy of revenues can

only be dealt with in a realistic way by reducing or even

totally eliminating other budgetary items. The amount of

city revenue devoted to public assistance has dramatically

increased over a ten-year period, even when compared to

such expensive services as police, fire and environmental

protection. City expenditures for public assistance grew

from $77,893,476 in calendar year 1959 to $499,272,000

in calendar 1970. During the same period, expenditures for

police grew from $168,000,000 (fiscal 1960-61), to $477,000,-

000 (fiscal 1970-71); fire, from $85,000,000 (fiscal 1960-61),

to $214,000,000 (fiscal 1970-71); environmental protection

from $109,000,000 to $256,000,000 (Exhibits 2 and 11). Thus,

expenditures for public assistance have increased out of

all proportion to expenditures for Police, Fire and Environ

mental Protection have only increased by 135% to 184%.

This is illustrated in the table below.

Percentage Increase

in Expenditures Over

10 Year Period

Public Assistance

Police

Fire

Environmental Protection

540%

184

152

135

17

13. The result of these actions and policies of the federal

and state governments has been to cause the plaintiff

City to be unable properly to discharge its constitutionally-

derived and imposed functions and responsibilities to its

residents and taxpayers. For illustration, arising from

these causes, the City has been unable to build adequate

housing, to build and staff the schools necessary to cure

overcrowding or to cope in an adequate manner with the

mounting demands of waste disposal and air pollution. The

jointly-mandated cost destroys the ability of the plaintiff

City to function as a viable municipal government.

14. The combined action by the federal and state gov

ernments, in their respective legislative enactments, and

of the officials of those respective governments in pursu

ance thereof which, as set forth and described in the fore

going paragraphs, threatens the very survival of the plain

tiff City, has involved violation of provisions of the federal

and state constitutions respectively, as follows:

a. With regard to the plaintiff City, the federal statute

above-cited has exceeded, and exceeds, the power delegated

to Congress under Article I, Section 8, Clause 1, of the

federal constitution in that, whereas the power delegated

to Congress under that Clause is to lay and collect taxes

to provide for the general welfare, it has been interpreted

and employed, as above-described and set forth, to man

date the plaintiff City of New York to tax and spend for

the general welfare. Specifically, the federal government,

through the legislation referred to, and the device of re

quiring approval by the Secretary of HEW of any state-

submitted plan and then after review granting approval

of the plan, has joined with the State of New York in

mandating the plaintiff City of New York in the manner

included in the plan in suit. Without the federal approval

so given, such state-submitted plan would never have taken

18

effect and would never have produced the federal-state

mandated action of which the plaintiff City has been the

victim, and currently suffers, as herein complained of. With

such federal approval so given, moreover, the State of

New York is not in a position, acting alone and without

further federal approval and consent, to undo the unfair

and unjust burden upon the plaintiff City which the State

of New York, acting by and through its officials, in conjunc

tion with the Secretary of HEW, has placed upon the plain

tiff City. The power to mandate is the power to destroy.

The power to mandate a particular item of cost, without

bound or limit as to amount, is the power to destroy. It

is no less so than the power to tax, and for the selfsame

reason.

b. With regard to the plaintiff City, the federal statute

above-cited, as here applied, constitutes an unconstitutional

intrusion into the affairs of the State of New York and of

the City of New York, of which the plaintiff City has been

the victim, and currently suffers, in a manner violative of

the Tenth Amendment of the federal Constitution, as well

as destructive both of the quasi-sovereignty of the states

and the integrity of the federal system. The reserved

powers so illegally intruded upon have included, and pres

ently include, the portion of those reserved powers granted

to the plaintiff City of New York under the Home Rule

provision of the New York State Constitution. By making

the determinations it has, the federal government, acting

by and through its Secretary of HEW, has proceeded in

a manner inconsistent with the foundation principles of

our dual system of government and intrusive into State-

City matters which are exclusive concerns reserved to the

States.

c. With regard to the plaintiffs other than the plaintiff

City, the federal statutes and the state statutes above cited

19

and described, by combining to effect the mandate on the

plaintiff City of which that plaintiff has been, and is the

sufferer, have had the further effect of depriving the plain

tiffs other than the plaintiff City of New York of essential

services to which, under our federal system, they would have

been entitled as citizens of the State of New York and resi

dents of the City of New York, and at the same time, and

in addition thereto, have greatly added to the burden of

their taxes as citizens, residents and taxpayers, all in viola

tion of the Due Process Clause of both the federal and state

Constitutions, the Ninth Amendment of the federal Con

stitution, and the Equal Protection Clause of the federal

and state Constitutions.

d. With regard to the plaintiff Jule Sugarman, that

plaintiff has been required to take, and has taken an oath

to uphold the Constitutions of the United States and of the

State of New York. That plaintiff is in the position of

having to choose between the enforcement of the above-

cited void and unconstitutional provisions, which would be

in violation of his oath of office, or his refusal to enforce

such provisions, which would be in violation of Sections

77, 131 and 131-a of the Social Services Law of the State

of New York requiring him to administer public assistance

in New York City, and in either instance might be vulner

able to attempts to obtain his removal.

15. By reason of the foregoing, the plaintiffs are entitled

to a judgment of this Court declaring and adjudging that

the combined action of the federal and state governments,

and the respective legislative enactments thereof as above

referred to, and the acts of the respective defendant officials

pursuant thereto, are illegal, unconstitutional and void,

and that the plaintiffs are entitled to a preliminary and

final injunction of this Court enjoining and restraining the

continuance in effect of such illegal and unconstitutional

20

mandate by the combined action of sucb federal and state

governments.

As and For a Second Cause of Action, in Favor of the

Plaintiffs Against the Defendant George Wyman, as

Commissioner of Social Services of the State of New

York:

16. The plaintiffs repeat each and every allegation con

tained in paragraphs “ 1” to “ 13” , inclusive, of this com

plaint, with like force and effect as if fully set forth and

realleged as part of this second cause of action.

17. The people of the state through their Constitution

have granted “home rule” to the cities; the legislature

cannot take it away through the technique of mandated

welfare costs which make it impossible for the cities to

exercise their “home rule” powers. The sections of the

state statute above-described and set forth, as applied to

the plaintiff City of New York and to the plaintiff Sugar-

man, are in violation of the provisions of the Constitution

of the State of New York, and specifically the Home Rule

provisions, Article IX, Sections 1, 2 and 3 thereof, and,

as applied to the plaintiffs other than the plaintiff City of

New York and the plaintiff Lindsay and the plaintiff Sugar-

man, are in violation of the Due Process and Equal

Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment of the

federal Constitution and of the Constitution of the State

of New York.

18. By reason of the foregoing, the plaintiffs are en

titled to a judgment of this Court declaring and adjudging

that the action of the New York State legislature, as above

referred to, and the acts of the defendant George Wyman,

as Commissioner of Social Services of the State of New

York, pursuant thereto, are illegal, unconstitutional and

void, and that the plaintiffs are entitled to a preliminary

21

and final injunction of this Court enjoining and restrain

ing the continuance in effect as obligatory upon the plain

tiff City of such unconstitutional state mandate.

As and For a Third Cause of Action in Favor of the

Plaintiffs Against the Defendant George Wyman, as

Commissioner of Social Services of the State of New

York:

19. The plaintiffs repeat and reallege each and every al

legation contained in paragraphs “ 1” to “ 13” , inclusive, of

this complaint, with like force and effect as if fully set

forth and realleged herein.

20. For purposes of the administration of public as

sistance under the State Social Services Law, the State of

New York has been divided under Section 61 of that Law

into specified, geographical social services districts. The

plaintiff City of New York and certain other cities under

that Section each comprise a social services district. Other

social services districts under Title 3-A of that Law are

county-wide or city-wide, by city option.

21. Each social services district under Section 62 of that

Law is made responsible for the aid, care and support of

the needy found therein.

22. The result of the organization of the public assis

tance system in New York by the State is to require the

various social services districts to pay, in general, ap

proximately one-quarter of the amount of public assistance

payments made in their districts. These amounts are

passed on, in normal course, through the burden of local

taxes, to the respective taxpayers in such districts.

23. The classification geographically of the State of New

York into respective social services districts for the pur

pose of allocating costs to them (as distinguished from

22

mere administration) is arbitrary in that it is based on

the assumption that the mere presence of poor people geo

graphically in a particular locality in the State furnishes

just and adequate reason to require their most immediate

neighbors in the same district to contribute to their support.

24. The number of people receiving public assistance in

the State of New York has grown from 512,691 in 1960 to

1,371,147 in 1969 (Exhibit 12). In the City of New York,

the increase was from 325,771 in 1960 to 1,016,405 in 1970,

an increase of more than 200% (Exhibit 12). Outside of

New York City, the increase was from 186,960 in 1960 to

354,742 in 1969, an increase of 89% (Exhibit 12). During

the calendar year 1970, 13.91% of the people in New York

City were receiving public assistance, up from 4.18% in

1960 (Exhibit 13). The huge and abnormal rises indicated

in the foregoing figures reflect causes far outside the re

sponsibility and control of the City of New York. As shown

previously, some 78% of the women receiving Aid to

Families with Dependent Children were not born in the

state (Exhibit 7). They are not reasonably or validly more

the responsibility of New York City residents and tax

payers than the responsibility of other citizens, residents

and taxpayers of the State of New York.

25. The large increase in the number of persons receiving

assistance in New York City has resulted in huge increases

which have been passed on to local residents and taxpay

ers. In 1969, 11.01% of tax revenues of the plaintiff City

of New York were spent on public assistance, namely,

$431,000,000 of the $3,914,000,000 of the City-financed

budget (Exhibits 8 and 14). New York City funds spent

on public aid per capita rose from $10.24 in 1960 to $63.46

in 1970. Local funds expended per capita for public assis

tance in New York City in 1968 inclusive of medicaid and

administrative expenses, were $27.39 as compared to $6.14

outside the City (Exhibits 15 and 16). As a result of the

23

above rapid rises-in public assistance costs, residents and

taxpayers in New York City have been foreed to pay in

creased taxes. Such taxpayers, moreover, are burdened

with higher welfare costs than those imposed on residents

of counties with few welfare recipients.

26. The problem of relieving poverty in New York State

is not a local problem. The phenomenon of poverty has

long since transcended local causation and control. The

poor are constitutionally entitled to, and do, cross the

boundaries of cities and states. The New York social ser

vice system, which obligates local social services districts

to bear by local taxation one-quarter of the public assis

tance costs incurred in such district is arbitrary and un

reasonable in that it bears no relation to the problem to

be solved, and, moreover, constitutes discrimination against

taxpayers who live in districts where relatively large num

bers of welfare recipients happen to reside at the time.

Residents and taxpayers in New York City are thereby

deprived by the State of New York of Due Process and

the Equal Protection of the laws under the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States and

the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the State

Constitution. The plaintiff City is deprived of its rights

and powers under the Constitution of the State of New

York, including specifically the Home Rule provisions,

Article IX, Sections 1, 2 and 3 thereof, and under the

above-stated Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses.

27. The plaintiffs in this third cause of action are en

titled to a decree of this Court declaring and adjudging

the provisions of the State Social Services Law, specifically

Sections 62, 91, 92, 131, 131-a, 153, 154 and 356, 365 and

368a thereof, that require each social services district to

pay approximately 29% of the total public assistance costs

incurred in such district, and the imposition of local taxes

24

to meet these, are invalid as in violation of the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the federal Constitution and the like Clauses of

the Constitution of the State of New York, as well as the

Home Rule provisions of the State Constitution, and en

joining and restraining the continued allocation and distri

bution of public assistance costs in the manner herein

stated, and the requirement as to the imposition of local

taxes accordingly.

For a Fourth Cause of Action in Favor of the Plaintiffs

Against the Defendants Elliott L. Richardson, Bernice

Bernstein, and Elmer Smith, Secretary, Regional Di

rector and Regional Commissioner respectively of

HEW, and John B. Connolly, as Secretary of the

Treasury.

28. The plaintiffs repeat and reallege each and every

allegation contained in paragraphs “1” to “ 13” , inclusive,

of this complaint, with like force and effect as if fully

set forth and realleged herein.

29. Since the need for public assistance is, as herein

above shown, a national need, and the problem of poverty

a national problem, and the requisite financial means of

the respective states to cope with that national problem

wholly inadequate, the provision of the federal statute

purporting to entrust it to the option and discretion of

any given state whether to avail itself of federal reim

bursement for the financing of its public assistance pro

gram is illusory. On a simple, factual basis, the individual

state is being either mandated or coerced to accept the

federal reimbursement of its public assistance expendi

tures to the extent, and in the manner offered under the

terms of the federal statute. Every state in the union has

received and accepted, and continues to receive and accept

such federal reimbursement as offered (Exhibit 1).

25

30. The effect of the public assistance needs within each

of the respective states turns the seeming choice of right

of election of each state into a federal mandate. Thus,

the federal role rather than being one of “assisting the

States” as stated in the Social Security Act has, given the

magnitude of the problem, left the states with no viable

option but to avail themselves of such federal assistance.

While the original Congressional intent may have been

at the time to assist the states in their then problems,

the facts have since so changed that assistance has be

come coercion, with options having become mandates. The

individual states are today being compelled to tax and

spend for the purpose of financing an obligation for the

“general Welfare” , which is properly and constitutionally

the federal responsibility under its delegated power.

31. Such compulsion extends the federal power under

the “general Welfare” clause of the federal Constitution

to a power not delegated and included in that consti

tutional grant of power to Congress, as no power was

ever granted to the federal government to coerce the

states or their subdivisions to “ tax and spend to provide

for the general Welfare.”

32. The effect of such illegal exercise by Congress of

its delegated power in the statute under consideration is,

further, to invade the province of power reserved to the

states under the Tenth Amendment. Further, it denies

and disparages the rights of the people of the several

states under the Ninth Amendment in that it interferes

with the enjoyment by the people of the benefits and

services which, under the federal system of the Constitu

tion, can be provided to the people only by the state and

local governments.

33. The effect of the federal statute referred to in the

foregoing paragraphs is to vary the percentage require

ment with each of the fifty states and the District of

26

Columbia. A table showing such varying percentages as

applied in the fiscal years July 1, 1969 to June 30, 1971,

is attached (Exhibit 17). Such unequal and varying per

centages of reimbursement to the respective states in turn

produce profound dislocations in the nation as a whole,

relative to the economic factors bearing on the ability to

compete in business and industry on a fairly competitive

basis. The dislocations with regard to economic factors

result from the higher burden of taxes in the states and

localities with higher public assistance benefits and larger

number of recipients causing, in turn, higher local prices

and higher living costs, which in their turn produce higher

local wages and thereby reduce the ability to compete in

business and industry of such high public assistance ju

risdictions. In such instance, moreover, where persons are

on fixed incomes, they may be depressed by such higher

living costs below the level of subsistence, thereby add

ing to the pool of the persons requiring public assistance,

in this manner producing a spiralling effect with regard

to such dislocations.

34. As described more fully in paragraph 9 above, the

effects of World War II and the technical changes in agri

culture have caused millions of poor persons to leave their

rural homes and migrate to the cities in search of work.

Lacking in skills or education, large numbers of these citi

zens found themselves on welfare. By failing to provide

100% reimbursement, the federal statute permitted those

rural states with large numbers of politically disenfran

chised poor blacks to keep welfare payments low, while im

posing a direct burden on the urban states to which these

citizens came in search of economic opportunities. The

indirect costs to the cities in terms of disruption to the

community and the higher costs of education, police, fire

and sanitation services, compounded by a deteriorating

27

housing supply and tax base, were even greater. Thus the

federal welfare program converted this national phenom

enon into an urban nightmare.

35. The federal statute as above described, to the ex

tent it fails to provide reimbursement of 100 % to each

and every one of the fifty states and the District of Co

lumbia, and the acts of the defendant public officials in

pursuance thereto, most specifically as applied to these

plaintiffs, is invalid and unconstitutional on the following

grounds:

a. It exceeds the power delegated to Congress under

Article I, Section 8, Clause 1, of the Constitution, “ To

lay and collect Taxes * * * to * * * provide for the

general Welfare of the United States,” transforming and

distorting that power by its mandate or coercion of the

states into a power “to lay and collect Taxes to compel

the states to pay and collect taxes to provide for the gen

eral Welfare of the United States.” Such excessive exer

cise of power by mandate to, or coercion upon, the states

to provide for this national responsibility for public as

sistance as a development of our modern urban society,

can be avoided only by a determination that the legisla

tion presently in effect be limited so that federal reim

bursement to the states for their public assistance ex

penditures be a full 100% and applied without discrimina

tion to all the states of the union.

b. It exceeds the power delegated to Congress as afore

said in that it brings about regulatory effects and economic

dislocations, not authorized by the Constitution, not directly

related to the delegated power to tax and spend to provide

for the general welfare, not adapted to such purpose, and

not in exercise of the necessary and proper powers with

respect to such constitutionally delegated power to tax

and spend.

28

c. It violates the Fifth Amendment, in particular the

Due Process Clause therein contained, in that it compels

some states, political subdivisions, and the citizens, resi

dents and taxpayers thereof, to bear national public bur

dens which, under our federal system and in all fairness

and justice, should be borne on an equitable basis by the

nation, its citizens, residents and taxpayers as a whole.

d. It violates the Fifth Amendment in that it discrim

inates in its operation and effect against non-whites who

are most affected by the adverse migratory consequences

and economic effects and dislocations hereinabove described.

e. It violates the Tenth Amendment by having an ad

verse regulatory effect unrelated to the delegated federal

power being exercised, and within the proper province of

the states under their reserved powers, at the same time

that it violates the Ninth Amendment by denying and dis

paraging rights retained by the people.

f. It violates the constitutional doctrine that protects

the right to travel, and the constitutional doctrine that

protects each state in its power, dignity and authority and

equality of quasi-sovereignty along with all the other states,

and entitled, as a consequence, to receive no less in the

way of favorable treatment from the federal government

than each of the other states of the union.

36. The within statute cannot be cured, insofar as it

exceeds the power of Congress as above set forth, except

by eliminating all provisions therefrom which would allow

for reimbursement to the states of less than 100% of their

public assistance expenditures.

37. By reason of all the foregoing, the plaintiffs are

entitled to have this Court declare and adjudge that the

federal statute in question, and all acts of the defendant

29

federal officials in pursuance thereof, are unconstitutional

and invalid to the extent that they permit or require any

state or political subdivision to receive less than 100% of

its public assistance expenditures, and any individual citi

zen, resident or taxpayer to receive in the given state less

than the result and effect of such 100% reimbursement.

For a Fifth Cause of Action in Favor of the Plaintiffs

Against the Defendants Elliott L. Richardson, Bernice

Bernstein and Elmer Smith as Secretary, Regional Di

rector and Regional Commissioner respectviely of

FLEW, and John B. Connolly, as Secretary of the

Treasury.

38. The plaintiffs repeat and reallege each and every

allegation contained in paragraphs “ 1” to “13” inclusive,

of this complaint, with like force and effect as if fully set

forth and realleged herein.

39. The effect of the provisions of the federal statute

referred to in the preceding paragraphs is to measure the

reimbursement by the federal government to any par

ticular state either: (a) after a percentage of a first small

dollar bracket of grant, on the basis of the single factor

of the square of the ratio of the per capita income of the

particular state to the per capita income of the nation as

a whole, or (b) on the basis of the single factor of the

square of that ratio alone. In either situation, the lower

such square of the ratio, the higher the percentage of re

imbursement to the given state. Conversely, the higher

such square of the ratio, the lower the percentage of reim

bursement to the particular state.

40. The statutory scheme above described, while pur

porting to be based upon and to take into account, the factor

of so-called “ability to pay” , does not in fact do so. This

is because the single factor of per capita income within

any given state reflects only the average of the per capita

30

income in the state, not the ability of individual persons

to bear the burden of expense and tax. A state with a high

per capita income ratio, which is therefore limited to receiv

ing under the federal statute a low reimbursement percent

age relative to other states, may be unable to avail itself

of such high per capita income to the extent necessary to

offset the lower federal reimbursement. Where, in any

given state, there is a marked degree of polarization be

tween the few of high income and the many of low income,

but at the same time resulting in a high per capita income

for the state, that state will still be unable to reach by

taxation the pool of high income in the hands of the narrow

sector of persons having such high income. By employing

as the basis for reimbursement the square of that ratio,

as distinguished from the ratio itself, the unreasonableness

of the statute is compounded in geometric proportion.

b. Moreover, the federal government has itself pre

empted by its own high income tax rates much of that

desirable and highly productive tax source. The same holds

true also with regard to such levies as death or gift taxes.

The consequence of the foregoing is that the per capita

income of the particular state fails to reflect truly the

ability to bear the burden of public assistance in that state

and thereby negates any reason why such state should be

treated less favorably by the government in the matter of

percentage of federal reimbursement for state public as

sistance expenditures than a state of lower per capita in

come. Tables illustrating, in the matter of personal in

come tax only, the priority on that desirable tax source

enjoyed by the federal government to the consequent dis

advantage of the state and local governments have been

attached as already stated (Exhibit 10).

41. The federal statutory scheme of varying percentage

reimbursement previously referred to is unconstitutional

31

and invalid additionally in that it fails to take into account

certain further factors required to be considered if the

percentage finally arrived at for the respective states is

to reflect the minimum of justice and fair treatment re

quired by the federal Constitution. Those additional fac

tors include, without being all-inclusive:

(1) the standard of public assistance benefits accorded

to the residents of the particular states; and

(2) the number of persons actually entitled to receive,

and receiving such public assistance, in the particular

state.

42. The percent system gives the respective states the

option of setting the benefit level. This has resulted in

significant variations of benefit level from state to state.

The non-white section of the population has been the big

gest sufferer from this set of circumstances. Many states

have established benefit levels below the poverty line. This

departure from a reasonable standard of public assistance

benefits could only be maintained in an area where the poor,

and especially the non-white poor, were, and continue to

be, systematically denied the benefit of full voting rights.

43. By reason of such statutory scheme, which is de

fective as stated as being based on the single factor of

per capita income alone and failing to take into account

at least the other two factors above-noted, the federal stat

ute under consideration is violative of the federal Constitu

tion and the federal constitutional system established there

under, in the following respects:

(a) It exceeds the power delegated to Congress under

Article I, Section 8, Clause 1 (the General Welfare Clause),

and to that extent violates that Clause of the Constitution,

in that by applying an unfair and unjust reimbursement

32

formula that favors certain states above others, it is di

rected to an unrelated, regulatory effect with regard to

population influx and outgo, and with regard, additionally,

to industrial and commercial competition among the sev

eral states, in both respects being disruptive of the unity,

coherence and normal economic growth as between the sev

eral states and no less the well-being of the country as a

whole.

(b) It violates the Fifth Amendment in the matter of

the Due Process Clause therein contained, in that it compels

some states, and the citizens, residents and taxpayers

thereof, to bear to an unjust and unreasonable extent na

tional public burdens which, in all fairness and justice,

should be borne equitably by the states, and the citizens,

residents and taxpayers of the nation as a whole. This it

does by placing an unequal and discriminatory burden on

the citizens, residents and taxpayers of states, the sole

distinguishing feature of which states is a high per capita

income, in favor of the like citizens, residents and taxpayers

of states with a low per capita income. It also violates the

Fifth Amendment to the extent that that Amendment bars

discriminatory treatment amounting to, and the equivalent

of, a denial of the Equal Protection of the laws, such latter

violation and adverse effect having particular reference to

the non-white sectors of the population.

(c) It violates the Tenth Amendment in that, by being

directed and designed to have, and by having, an adverse,

regulatory effect unrelated to the particular delegated

power being exercised, namely, the power to spend to pro

vide for the general welfare, it invades the proper field of

exercise by the states of their reserved powers.

(d) It violates the constitutional doctrine that protects

the Right to Travel (including the right to settle and to

33

return) in that, by applying unjust and discriminatory per

centage reimbursements to the respective states, it has an

adverse, inhibitory effect on travel by indigents seeking

employment and other benefits. It also violates the doctrine

by preventing moderately-circumstanced persons from

migrating to those cities where they will be subject to

increasingly burdensome state and local taxes caused by

excessive federal welfare costs. Moreover, the city is de

prived of the benefits of such migration.

(e) It violates the constitutional doctrine that protects

each state in its equality of quasi-sovereignty along with

all other states, and entitled on that basis to receive no

less in the way of favorable treatment from the federal

government than the treatment accorded to all the other

states of the union.

44. By reason of all the foregoing, the plaintiffs are

entitled to have this Court declare and adjudge that the

federal statute in question is unconstitutional and invalid

to the extent that it puts into effect the presently unjust

and discriminatory statutory scheme of federal reimburse

ment based on the single factor of per capita income alone,

and permits any given state to receive less by way of fed

eral reimbursement for public assistance expenditure than

100% of such expenditure, or permits any state to receive

less by way of such federal reimbursement on a percentage

basis than any other state, and permits any individual, citi

zen, resident or taxpayer to receive in his state less than

the full benefit to which he would, under a valid statute,

be entitled.

W herefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray the Court for

judgment against the defendants, as follows:

34

On the First and Second Causes of Action:

1. Declaring and adjudging that the combined action of

the federal and state governments, and of the respective

defendant officials thereof, as alleged and described above,

is illegal, unconstitutional and void ; that the plaintiff

City of New York is entitled to a preliminary and perma

nent injunction of this Court enjoining and restraining

the continuance in effect and operation of such illegal and

unconstitutional combined mandate.

On the Third Cause of Action:

2. Declaring and adjudging that the provisions of the

State Social Services Law, specifically Sections 62, 91, 92,

131, 131-a, 153, 154 and 356, 365 and 368-a thereof, that

provide for the distribution and allocation of public assis

tance costs and payments, and the imposition of local taxes

accordingly, are invalid as in violation of the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, and the Home Rule provisions of the New York State

Constitution, and that the plaintiffs are entitled to a pre

liminary and permanent injunction enjoining and restrain

ing the continued division of the State into such social

services districts, and the allocation and distribution of

public assistance costs and the requirement as to the impo

sition of local taxes accordingly.

On the Fourth Cause of Action:

3. Declaring and adjudging: (1) that the federal statute

in question is unconstitutional and invalid to the extent

that it provides for any state to receive less than 100%

for its public assistance expenditures, and any individual

citizen, resident or taxpayer to receive in the given state

less than the benefit of such 100% reimbursement; and (2)

that the federal statute is unconstitutional and invalid to

the extent that it provides for any state to receive reim

35

bursement in a percentage less than the percentage received

by the state receiving the highest such reimbursement

percentage; and (3) granting appropriate injunctive relief,

both preliminary and final, accordingly.

On the Fifth Cause of Action:

4. Declaring and adjudging that the federal statute in

question is unconstitutional and invalid to the extent that

it puts into effect the presently unjust and discriminatory

statutory scheme of federal reimbursement, based on the

single factor of per capita income alone, and permits any

given State to receive less by way of federal reimbursement

for public assistance expenditure than 100% of such ex

penditure, or permits any State to receive a lower per

centage of federal reimbursement than any other state.

5. That plaintiffs have such other and further relief as

to this Court may seem just and proper.

Dated: New York, N. Y.

February 24, 1971.

Signed :

J. Lee Rankin,

Corporation Counsel,

Attorney for Plaintiffs,

Office & P.O. Address:

Municipal Building,

New York, N. Y. 10007.

Tel. 566-4515

Norman Redlich,

E dmund B. Hennefeld,

Mary P. Bass,

of Counsel.

36

Verification

State of New Y ork,

County of New Y ork, s s . :

John V. L indsay, being duly sworn, deposes and says

that he resides in the Borough of Manhattan, City of New

York; that he is one of the plaintiffs herein; that he has

read the foregoing complaint and knows the contents

thereof and that the same are true of his own knowledge

except as to the matters therein stated to be alleged on

information and belief, and that as to those matters he

believes them to be true.

John V. L indsay

Sworn to before me this

24th day of February, 1971.

Mary Rita Rheinwald

Notary Public, State of New York

No. 43-8555500

Certificate filed in Richmond County

Commission Expires March 30, 1972

la

Exhibit 1

TABLE 1

PROPORTION OP POPULATION OX FEDERALLY AIDED WELFARE UNDER

PRESENT LAW AND ADMINISTRATION REVISED REVISION

Civilianresidentpopulation

> eder&Uy aided welfare recipients, January 107*

Percent of Number population

Welfare recipients eligible under administration revised rcylsion

rerecut of Number population

1 ̂

Total, United

States ____ . . . 203,790,700 10, 436, 197 s 1 23, 800, 300 11. 7

Alabama.. ________ 3,505,000 255, 400 3 6G5, 800 19. 0

Alaska____________ 252,000 10, 274 4 1 25, 100 10. 0 ’|

Arizona________ . . 1,085,000 72, 410 4 3 204, 600 12. 2

Arkansas__________ 1,990,000 115, 000 5 .8 369, 700 IS. 5

California_________ 19,213,000 1, 655, 400 8,6 2, 323, 400 12. 1 1.

Colorado__________ 2,065,000 111, 110 5.5 368, 000 17. R 0

j

Connecticut___T_. . 3,009,000 97, 140 5 2 187, 900 6. 2 «

Delaware__________ 537,000 23, S60 4.4 55, 000 10. 2 I

District of Columbia. 783,000 47, 490 6. 1 65, 900 8. 4

Florida___________ 0,332,000 295, 900 4.7 683, 600 10.. 8 i j

Georgia___________ . . 4,565,000 328, 400 7.2 1, 025, 500 22. 5 I

Hawaii____________ 747,000 29, 072 3.9 02, 700 8. 4 I

Idaho_____________ 717,000 22, 100 5 1 51,400 7. 6 1

Illinois____________ 11,031,000 446, 100 4.0 S06, 300 7. 3

Indiana______ ___ 5,136,000 98, 100 1.9 298, 100 5. 8 L

Iowa___________ . . 2,785,000 92, 300 OO. O 235, 700 8. 5 K

KKansas. . _________ 2, 28S, 000 73, 940 3.2 158, 600 6. 9 I

Kentucky_________ 3, 192, 000 211, 200 6.6 523, 500 16. 4 VLouisiana__________ 3,724,000 346, 500 9.4 934, 200 25. 1

Maine____________ 967,000 43, 920 5. £ 145, 400 15. 0 M

Mai yland______ . . 3, 732,'000 157, S50 4.2 202, S00 7. 0 M

M

Massachusetts___ . . 5,475,000 282, 500 5. 2 438, 500 8. 0 \;

Michigan__________ 8, 70S, 000 310, 200 3. U 6-10, 400 7. 3 MMinnesota.... ........... 3,714,000 10S, 120 2. $ 320, 3110 8. 6

Mississippi....... ........ 2,336,000 211, 000 9. 0 806, 10U 34. 5 V '

Missouri__________ 4,637,000 255, 200 5. 5 443, 600 9. 6 y

N

Montana_____ ____ 688,000 18, SS0 2. ; 52, 200 7. G._ N

Nebraska__________ 1,437,000 43, 550 3 .0 107, 700 11. 7 N

Nevada...---------- 452,000 15, 570 3. 4 37, 000 8. 2

New Hampshire____ 720, 000 la, 200 2.0 39, S00 5. 5 N

New Jersey________ 7,128,000 3IS, 720 4. 5 50S, 800 7. 1

a

V

New Mexico_______ 976, 000 69, 260 7. 1 194, 400 19. 9 N

New York_________ 18,309,000 1, 227. 400 6. 7 1, 979, 300 10. 8 N

North Carolina. . . .. 5,110,000 194, 600 3. $ 900, 600 18. 9

North Dakota... ---- 600,000 16, 583 2.S 90, 900 16. 2 < »•

Ohio______________ 10,786,000 355, 400 3.3 799, S00 7. 4

< )i,

Oklahoma__________ 2, 545, 000 188, 700 7. 4 • 366, 200 14. 4 p.

Oregon. ---------------- 2,044,000 93, 800 4. 6 143, 500 7. 0 1:.

Pennsylvania_______ 11,797,000 511, 800 4. 3 1, 234, SU0 10. 5

Rhode Island........ . 8S6, 000 45, 810 5. 2 67, 200 7. 6 >.*

South Carolina______ 2,036,000 83, 900 3. 2 490, S00 18. G T

South Dakota---------- 650, 000 22, 110 3. 4 107, 400 16. 5 T

Tennessee__________ 3,971,000 205, 400 5. 2 741, 800 18. 7 V

Texas______ ______ 11,097,000 478, 800 4. 3 1, 521, 500 13. 7

Utah______________ 1,049,000 42, 760 4. 1 55, 100 5. 3 V,

Vermont___________ 444,000 18, 000 4. 1 46, 800 10. 5 W:

Virginia____________ 4,514,000 109, 400 2. 4 431, 300 9. 6 w

Washington------------- 3, 3S6, 000 153, 450 4. 5 312, 300 9. 2 \v

West Virginia_______ 1,819,000 115, 5S0 6. 4 275, 300 15. 1

Wisconsin.......... ........ 4,242,000 101, 180 2. 4 23S, 400 5. 6 w

Wyoming--------1 ------ 317,000 7, 447 2. 3 20, 000 6. 3

Puerto Rico----------- 2,763,000 264, 930 9. 0 800, 000 29. 0

Guam_____________ 87,700 2, 072 2. 4 3, 400 3. 9

Virgin Islands--------- 59,000 2, 319 3. 9 2, 900 4. 9

30URCE:

Congress,

Finance,

H.R. 16311,

2d bession.

The Family Assistance Act of 1970. 91st

Analysis by the staff of the Committee on

Senate, p. A13

Tab!* 1. — R ecip ient* o f p u b lic a s s is ta n c e sjoney payments and/or non-medi ndor payments and average monthly payment per r e c ip ie n t ,

by program, December o f calendar yc«ra 1936-1969 1J

Recipients (in thousands)

December

Of

each

year

Old-age

assist

ance

Aid to

the blind

Aid to

the per-

manently

and total

ly dis

abled

Aid to fondlies with

dependent children General

assist

ance \J

Emergency

assistance

(Families)

Institu

tional

services

in inter

mediate

care

facilities

Old-8ge

assist

ance

Aid to

the blind

Aid to

the per

manently

and total

ly dis

abled

Aid to

f aid lies

with de

pendent

children

General

assist

ance y

Kmcrgency

assict&nce

(p«- Jarlly)

Famines

Total

recipi

ents 2/

Children

’ 6........... 1,10 8 k5 ... 162 5k6 kok k,5k5 ... ... ne.8o 426.10 48.80 48.00 ...

1,579 56 — 229 769 568 k,8k0 — ... 19.k5 27.20 — 9.35 8.50 ...

'3........... 1,779 67 — 281 935 688 5,177 — - — 19.55 25.20 — 9.60 7.90 ...

1,912 70 — 316 l,0k2 76k k,675 — — 19.30 25 .k5 — 9.65 8.30 “

’*0........... 2,070 73 ... . 372 1,222 895 3,618 ... ... 20.25 25.35 ... 9.85 8.30 ...

1 ........... 2,238 77 — 391 1,208 9kk 2,068 — - ... 21.25 25.80 — 10.20 9.U0 —

2........... 2,230 79 — 3U9 1,15 8 851 1,000 ... ... 23.35 26.55 ... 10.95 11.6 5 —

3........... 2,lk9 76 ... 272 916 676 558 — - — 26.65 27.95 ... 12.35 lk. 55

k........... 2,066 72 — 25k 862 639 k77 ... — 28.1*5 29-30 13.kO 15.60 ...

5........... 2,056 71 ... 27k 9k3 701 507 — ... 30.90 33.50 ... 15.15 16.55 ——

5........... 2,196 77 ... 3k6 1,190 685 673 . .. ... 35.30 36.65 ... 18 .10 18.k5 ...

?(It 2,332 81 ... kl6 1 ,1*26 1,060 739 ... ... 37.kO 39.60 ... 18.1*0 20.60 ...

9........... 2,1*98 86 ... k75 1,632 1,21k 8k2 — k2.oo k3.55 20.90 22.kO . —.

9........... 2,736 93 — 599 2,ok8 1,521 1,337 ... — kk.75 k6 .10 ... 21.70 21.25 —

0........... 2,786 97 69 651 2,233 1 ,6 6 1 866 ... __ k3.05 1*6.00 4kk.l0 20.85 22.259 2,701 97 12b 592 2,0kl 1,523 66k ... ... kk.55 1*8.05 1*6 .U5 22.00 22.90 — •

2,635 98 161 5?6 i,9?l 587 — — - k8.8o 53.50 ke.ko 23>5 23.30 —

7 2,582 100 192 5U7 l,9kl l,l*6k 618 ... — - k8.90 5k.05 k7.90 23.20 22.05 --

4........ . 2,553 102 222 60k 2,173 3.639 880 ... — U8.70 5k.35 V8.35 23.23 22.85 ...

5........... 2,538 1C* 2k 1 602 2,192 l,66l 7k3 • ... — 50.05 55.55 k8.75 23.50 23.30 --

................. 2,1*99 107 266 615 2,270 1,731 731 ... ... 53.25 60.00 50.70 2k . 00 23 .k5 — •

7.......... . 2,U80 108 290 667 2,1*97 1,912 907 ... — 55.50 62.20 52.35 25. kO 22.70 —

9........... 2,k38 no • 325 755 2,1*86 2 ,18 1 l,2k6 ... ... 56.95 63.55 53.80 26.65 2k .05 ——

9.......... . 2,370 106 3>*6 776 2,9k6 2,265 1,107 ... — 56.70 65.60 5k.15 27.30 23.05 —

o ........... 2,305 107 369 803 3,073 2,370 l,2kk ... ... 58.90 67.k5 56.15 28.35 2k . 85

1 ........... 2,229 103 389 916 3,566 2,753 1,069 — - — 57.60 68.05 57.05 29.k3 26.15 — •

-2........... 2,183 99 1*28 932 3,789 2,8kk 900 — — 61.55 71.95 58.50 29.30 26.30

3........... 2,152 97 k6k 95k 3,930 2,951 872 — - — - % 62.80 73.95 59.85 29-70 27.k5 • ••

h ........... 2,120 95 509 1,0 12 **,219 3,170 779 ... ... 63.65 76.15 62.25 31.50 30.50 ...

5........... 2,087 85 557 1 ,05k k,3S6 3,316 677 ... ... 63.IO 81.35 66.50 32.85 31.65 —

6 ........... 2,073 8k 588 1 ,12 7 k,666 3,526 663 ... — 68.05 66.85 7k. 75 36.25 36.20 ...

7........... 2,073 83 6k6 1,297 5,309 3,936 782 ... —— 70.15 90.k5 80.60 39.50 39.kO ...

2 ,o n 81 702 1.522 6,036 k,555 826 ... lb 69.55 92.15 82.65 1*2.05 kk.70 —

2.077 --- 51---- 803 1.675 7.313 ?.4i3 657 8 92 73.95 93-75 90.20 • >•5’l5 50.05 T O T

2,025 00 711 1,556 6,223 k,65l 652 -- 32 69.75 93.00 83.V5 k2.95 45-30 -—

2,025 80 718 1,592 6,38k k,7k9 828 -- 58 70.10 93.15 ek.30 k2.70 k5.05 — -

March........ 2,030 80 728 1,622 6,1.87 k,821 826 ... 60 70.65 9k .25 a*.6o k2.90 W6.20 —

2,031 80 738 1,0*3 6,551 k,869 8ck — 67 70.55 9k .k5 85.10 k3.35 k7.55 —

Kay.......... 2,033 80 7k7 1,652 6,555 k,876 795 -- 69 70.65 9k. 85 85.65 k3 .10 k7.55 ———

2,036 8o 755 1 ,66k 6,577 k,893 767 — 77 70.50 95.30 85.65 k3.85 k7.65 —

.̂ ily....... 2,0kl 80 763 1,63k 6,63k k,932 73* 6 86 70.95 95.30 86.20 kk.30 k8.20 118.00

2,0kk 80 770 1,717 6,7k8 5,015 807 8 88 71.35 95.80 87.10 k5.05 k8.95 Ilk.95

Scptesber..... 2,052 80 777 1,753 6,8r6 5 .1 1 1 826 8 89 72.50 97.05 87.-5 k5.10 k7.70 123.30

2,063 So 786 1,790 6,995 5,199 822 7 90 73.30 97.95 09. -0 k5.25 k8.70 n5.50

2,070 SO 793 1,626 7,12k 5,238 821 8 92 73.kO 98.30 89.05 kk.75 k9>5 117.60

>ceber...... 2,077 81 803 1,875 7,313 5,kl3 857 8 92 73.95 98.75 90.20 k5.15 50.05 113.00

Average monthly payment per recipient

Institu

tional

services

in inter

mediate

care

fa c ilitie s

« -

ict!# '

21k.30

219.90

223.83

22k. kO

23k.70

231.03

2k3.53

2kT.60

2kk.k3

2k2.33 Jk6.80

laeluSei Putrto Rico and tha Virgin Ialnnda, beginning October 1950 (under the 1950 enendnenta to the Social Security Act) end Pv t , hfjjnnirg hily 3959 (under tba 195# aemdnanta).

Children and c m or both parenta or ooa adult caretaker relative other then a parent In fanlllei In vhlch the requlrenenta of tC'-h adult* veto < O'lAered la datenlnlng the aaount of aailvtaaca] kaferl

Ceceeixr 1950 partly eatlnatad.

Tata inco*̂ 3lets.

Urgency assistance authorized to needy families with children urier title IV-A.

I

SOURCE: Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Social and Rehabi

litation Service, National Center for Social Statistics, Public

Assistance -Annual Statistical Data - calendar year 1969 (NCSS

Report A-7 (CY 69) P« 1

E

xhibit 2

I

i

Table 3. - - Amount o f public u i l i t u c t payments, by program, calendar years 1936-1969

(Amounts In thousands)

Money payments Medical vendor payments \ j

Total

Federal ly aided programs

General

assistanca

Total

Federally

aided

programs

General

assistance

Total Old-age

assistance

Aid to

the

b lind

Aid t o the

permanently

and

t o t a l l y

disabled

Aid to

families

with

dependent

ch ild ren

Amount

Percent o f

t o t a l

payments

$6 5 5 ,0 8 6 $217,951 $1 5 5 ,6 8 6 $1 2 ,8 1 6 . _ $6 9 ,6 5 3 $637,136 . . . . . . .

802 ,93T 396,217 309,550 16,173 . . . _ 7 0 ,6 9 6 *06,720 . . . — - —

987,025 511,619 396,876 18,953 . . . 97,59* 675,606 — — . . .

1,050,790 568,670 *33.507 20,372 . . . 1 1 6 ,7 9 1 6 8 2 ,12 0 . . . — — . . .

1 , 0 2 0 ,1 1 5 6 2 7 ,9 0 6 672,778 21,735 . . . 133,393 39* .2 0 9 — — — . . .

9 8 9 ,3 9 7 716.231 5*0,07* 2 2 ,9 5 6 . . . 153,301 2 7 1 ,1 6 6 . . . — — . . .

9 56 ,8 6 6 776,608 5 0 7,6 0 0 26,559 . . . 15 8 ,6 6 9 18 0 ,* 3 8 . . .

9 2 6 ,3 2 5 815,616 6 6 9 .9 7 0 25,065 . . . 1*0,399 110,91* — . . . . . . —•

9 6 0 .3 9 9 851,051 690,727 25,256 . . . 13 5 ,0 6 8 8 9 ,3 6 7 — . . . . . .

9 8 7 ,9 3 6 901,673 725.683 26.515 . . . 1 6 9 .6 7 5 86.262 . . . . . . — . . .

1 , 1 7 9 ,3 1 8 1,058,921 819,766 30,717 . . . 2o e ,* * o 12 0 .3 9 6 . . . . . . — . . .

1 , 1*8 0 ,6 0 0 1.316,576 9 8 6 ,3 6 6 3 6 ,1 9 3 . . . 29* ,0 1 5 166,226 . . . . . . . . . . . .

1 ,7 3 0 ,7 1 3 1,532,262 1,126,190 k l , 28k -y - 352,788 198,651 . . . . . . . . . . . .

2 , 1 7 6 ,9 7 6 1,893.717 1,372,898 *8,U*8 . . a 672,371 281,257 — " r . . . . . .

*,*5* ,*85 2 ,o6 l ,7 0 0 1,653,917 52.567 $8,062 567,176 292,786 $5 1 ,8 0 3 2 .2 $21,916 $29,867

2,279,612 2,065,153 1 , 6 2 7 ,6 0 3 5 6 ,6 7 3 56.312 568,765 196.659 103,179 ■ 6.J 5 6 ,7 8 2 *6,397

* . 3 l l .5 * > 2,162,065 1,662,936 59.536 81,533 538 ,0 6 0 169.695 139.539 5.7 8 8 ,6 1 6 51,105

2 , 3 7 6 ,1 5 8 2,222,891 1,513,293 6 3 .6 0 1 1 M , 0 U 563.966 151,267 165,721 6.5 116,606 51,315

2 . 6 5 1 ,7 8 5 8,855,735 1,697.578 65,236 1 1 9 ,7 9 1 573,128 1 9 6 ,0 5 0 1 9 0 ,8 5 1 1 .2 129,117 6 1 .7 3 3

8,516,590 2,102,636 1,687,991 67,806 1 3 6 ,6 3 0 6 1 2 ,2 0 9 213,956 211.566 6 .* 1 6 3 ,6 1 7 68,127

2 , 58* . 20k 2,387,003 1 , 52 9 ,0 6 8 72.926 150,162 63*,887 isrr.2 0 1 268 ,8 66 9.* 196,705 72,161

2 ,7 8 8 ,1 6 1 2,577,082 1 , 6 0 9 ,3 9 0 T8.679 172,170 716,8*42 2 1 1 , 07? 3 0 2 ,1 6 1 9.8 226,695 77,6*8

3 ,0 6 8 ,7 0 1 8,765,393 1,667,376 81,655 1 9 6 ,6kk 8 1 9 ,9 1 8 30 3.306 357,75* 10.* 266,972 92,786

3,200,768 2 , 8 5 8 ,7 1 9 1,620,715 83,553 217,279 937,172 362.069 6 56 ,9 6 6 1 2 .5 36 0 ,6 65 96,298

3,262,769 2/ 2 , 9 6 3 ,2 6 8 1 , 6 2 6 ,0 2 1 8 6 ,0 6 0 236,*08 9 9 6 ,6 2 5 319.521 5 2 2 ,2 2 8 U - J 1..*0,*** 1 0 1 ,9 8 3

3 6̂ 10 ,5 6 8 2j 3 .0 5 9 ,1 5 3 1 ,5 68 ,9»T 8*.506 255,665 1 , 16 8 ,8 3 8 351.395 6 8 8 ,3 2 0 1 6 .8 5V3, 058 110,262

3 , 5 1 2 ,1 2 8 5 / 3,222,590 1 , 5 6 6 ,1 2 1 83,856 2 8 1 ,1 1 7 1 , 2 8 9 ,8 2 6 269,536 926,978 20.8 t n , 8 6 6 1 0 2 ,1 1 5