Plaintiffs' Brief in Opposition to Motion to Dismiss

Public Court Documents

March 3, 1975

17 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Brief in Opposition to Motion to Dismiss, 1975. e4089444-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a6e31b2c-4082-4d07-a2c1-99e4a2e64cc9/plaintiffs-brief-in-opposition-to-motion-to-dismiss. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

#

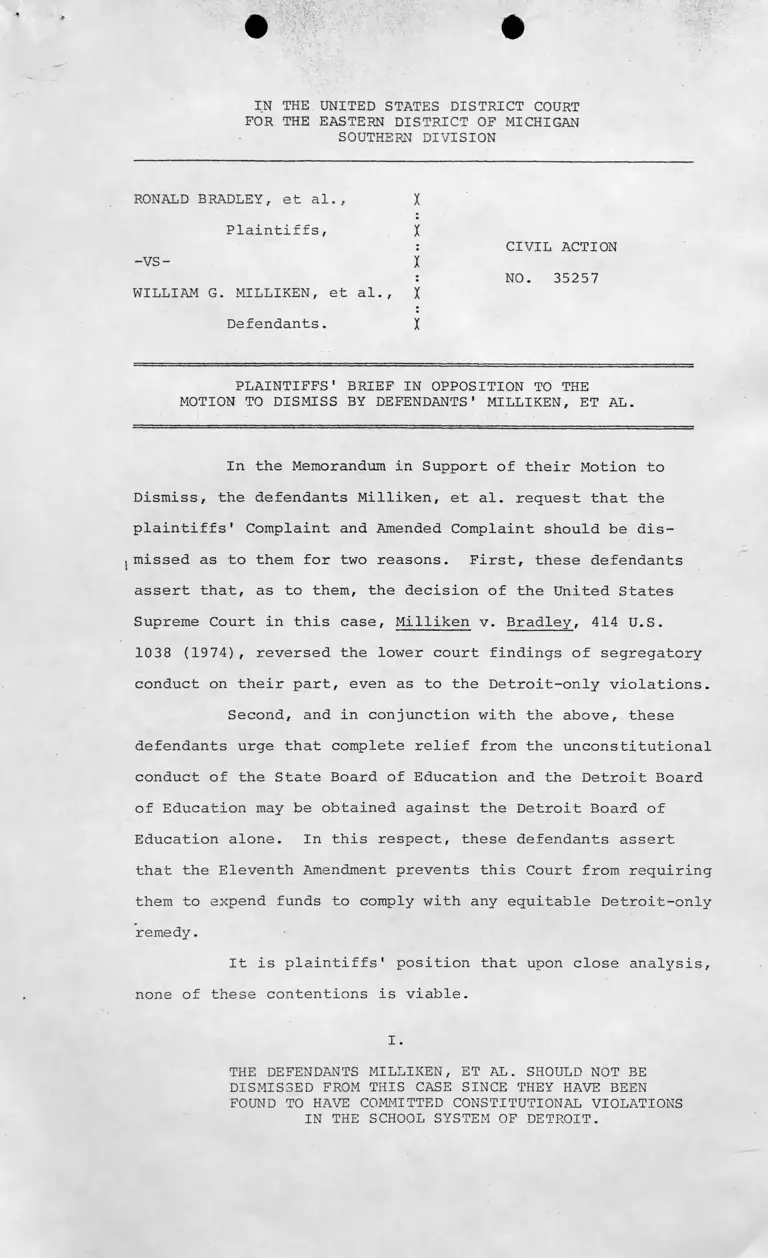

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al., X

Plaintiffs,

»

X

• CIVIL ACTION

-VS- X

: NO. 35257

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al., X

Defendants.

•

X

PLAINTIFFS 1 BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO THE

MOTION TO DISMISS BY DEFENDANTS' MILLIKEN, ET AL.

In the Memorandum in Support of their Motion to

Dismiss, the defendants Milliken, et al. request that the

plaintiffs' Complaint and Amended Complaint should be dis

missed as to them for two reasons. First, these defendants

assert that, as to them, the decision of the United States

Supreme Court in this case, Milliken v. Bradley, 414 U.S.

1038 (1974), reversed the lower court findings of segregatory

conduct on their part, even as to the Detroit-only violations.

Second, and in conjunction with the above, these

defendants urge that complete relief from the unconstitutional

conduct of the State Board of Education and the Detroit Board

of Education may be obtained against the Detroit Board of

Education alone. In this respect, these defendants assert

that the Eleventh Amendment prevents this Court from requiring

them to expend funds to comply with any equitable Detroit-only

remedy.

It is plaintiffs' position that upon close analysis,

none of these contentions is viable.

I.

THE DEFENDANTS MILLIKEN, ET AL. SHOULD NOT BE

DISMISSED FROM THIS CASE SINCE THEY HAVE BEEN

FOUND TO HAVE COMMITTED CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATIONS

IN THE SCHOOL SYSTEM OF DETROIT.

• #

A.

The district court opinion found the following con

stitutional violation to have been committed by the State

defendants as to Detroit-only violations:

The State and its agencies, in addition

to their general responsibility for and

supervision of public education, have acted

directly to control and maintain the pattern

of segregation in the Detroit schools. The

State refused, until this session of the

legislature, to provide authorization or

funds for the transportation of pupils within

Detroit regardless of their poverty or distance

from the school to which they were assigned,

while providing in many neighboring, most white,

suburban districts the full range of state

supported transportation. This and other fi

nancial limitations, such as those on bonding

and the working of the state aid formula where

by suburban districts were able to make far

larger per pupil expenditures despite less tax

effort, have created and perpetuated systematic

educational inequalities.

The State, exercising what Michigan courts

have held to be in "plenary power" which includes

5 power "to use a statutory scheme, to create,

alter, reorganize or even dissolve a school dis

trict, despite any desire of the school district,

it's board, or the inhabitants thereof," acted

to reorganize the school district of the City of

Detroit.

The State acted through Act 48 to impede,

delay and minimize racial integration in Detroit

schools. The first sentence of Sec. 12 of the

Act was directly related to the April 7, 1970 de

segregation plan. The remainder of the section

sought to prescribe for each school in the eight

districts criterion of "free choice" (open enroll

ment) and "neighborhood schools" ("nearest school

priority acceptance"), which had as their purpose

and effect the maintenace of segregation.

In view of our findings of fact already noted,

we think it unnecessary to parse in detail the

activities of the local board and the state authori

ties in the area of school construction and the

furnishing of school facilities. It is our con

clusion that these activities were in keeping,

generally, with the discriminatory practices which

advanced or perpetuated racial segregation in

these schools.

Bradley v. Milliken, 338 F.Supp 582, 589 (1971).

These findings were repeated verbatim and affirmed

by the en banc opinion of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215, 238-39 (6th Cir. 1973).

2-

As the Sixth Circuit concluded:

The discriminatory practices on the

part of the Detroit School Board and the

State of Michigan revealed by this record

are significant, pervasive and causally re

lated to the substantial amount of segrega

tion found in the Detroit school system by

the District Judge. Bradley v. Milliken,

supra, at 241.

The Opinion of the United States Supreme Court

stated:

"[t]he District Court also found that

the State of Michigan had committed several

constituional violations with respect to

its general responsibility for and super

vision of public education." Milliken v.

Bradley, 414 U.S. 1038, 41 L.Ed.2d 1069,

1081 (1974). (Footnote omitted).

More significantly, the Supreme Court stated:

School districts in the State of Michigan

are instrumentalities of the State and sub

ordinate to its State Board of Education and

legislature. The Constitution of the State of

j Michigan, Art. VIII, §2, provides in relevant

part: "The legislature shall maintain and

support a system of free public elementary and

secondary schools as defined by law." Similarly,

the Michigan Supreme Court has stated that "the

school district is a state agency. Moreover, it

is of legislative creation...." Attorney General

v. Aoweey, 131 Mich. 639 , 644 , 92 NW 2 8 9', 290

(1902); "Education in Michigan belongs to the

State. It is no part of the local self-government

inherent in the township or municipality, except

so far as the legislature may choose to make it

such. The Constitution has turned the whole

subject over to the legislature...." Attorney

General v. Detroit Board of Education, 154 Mich.

584, 590, 118 NW 606, 609 (1908).

Milliken v. Bradley, ___ U.S. ____, 41 L.Ed.2d 1069 , 1081

n. 5 (1974).

The Supreme Court then catalogued the findings of

the Court of Appeals with respect to the States* violations.

See Milliken v. Bradley, ___ U.S. ____, 41 L.Ed.2d 1069 , 1085

n. 16 (1974). Only after these recitals and in the context of

considering the appropriateness of metropolitan relief, the

Supreme Court stated:

"[0]ur assumption, arguendo... that

state agencies did participate in the main

tenance of the Detroit system, should make

3

• #

it is clear that it is not on this point

that we part company." Milliken v.

Bradley, U.S. , 41 L.Ed.2d 1069,

1092 (197471

Thus, the Opinion of the Supreme Court does not

support the contention of the State defendants that the Court

reversed the findings of constitutional violations against

the defendants Milliken, et al. In fact, the Supreme Court

accepted the findings of the district court and the Sixth Cir

cuit with respect to the state involvement in the Detroit-only

violation.

The State defendants attempt to tie the logic of

their reasoning to speculation as to the Supreme Court's action

denying plaintiffs motion to require each party to bear its

own costs in that Court merely demonstrates the slender reed

on which their argument rests. Speculation of this sort is

perhaps as weak as speculation as to the Court's reasons for

,the denial of a petition for certiorari.

The State defendants' central role in this litigation

is highlighted by the history of the case and Michigan's brand

of interposition. The Michigan Legislature enacted and the

Governor signed into law, Act 48, Public Acts of 1970. The

effect of Section 12 of this Act was to rescind for at least

one year, the attempt made by the Detroit Board of Education

to achieve integration in some of its high schools. The Sixth

Circuit stated: " [w]e hold §12 of Act 48 to be unconstitu

tional and of no effect as violative of the Fourteenth Amend

ment." Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F.2d 897, 904 (1970). This

holding was not overturned by the Supreme Court. See Milliken

v. Bradley, ____ U.S. , 41 L.Ed.2d 1069, 1094(1974).

— In fact they quite deliberately fail to advise this

Court that they made almost the precise same argument to the

Sicth Circuit, with respect to what they thought the cost dis

pute and result in the Supreme Court meant. They sought to

have the Sixth Circuit retax costs in that Court (it has pre

viously ordered each side to bear its own costs). On December

20, 1974, the Sixth Circuit, en banc without a single dissent

rejected their view and refused to retax costs. A copy of the

opinion is attached hereto as Exhibit A.

-4-

# #

These state defendants are as necessary now to

the relief state of the proceedings in this case as when the

Sixth Circuit determined them to be "proper parties" in 1970.

See' Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F.2d 897, 905 (6th Cir. 1970).

In that appeal the district court, on these same defendants'

motion, dismissed them as parties. Plaintiffs appealed and

argued that at the very least they might be needed for relief.

We pointed out then and now that many times the Courts have

been required to add State officials as parties to insure

compliance with its orders in school cases. Just as Judge

Roth, when it came time to order the purchase of transportation

equipment, or require other payments by State defendants,

found it necessary to add the State Treasurer, Allison Green,

so too this Court will require the presence of State defendants

as parties. If any one of them were to be let out of the case,

and this Court then decided they were needed to assist in

9remedy, these same lawyers would scream that due process was

violated in that an order had been entered which affected

them at a time they were not parties. What defendants would

have this Court do is fall into a trap so that the defendants

might fill their "error bag." 2/

THE ELEVENTH AMENDMENT DOES NOT BAR THE PAR

TICIPATION OF THE DEFENDANTS MILLIKEN, ET AL.

IN EQUITABLE RELIEF FROM CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATIONS.

These defendants also assert that the Eleventh

Amendment prohibits the expenditure of public funds from the

State Treasury, in order to comply with orders of a Federal

Court. See Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 657 (1974). Appar

ently, at this juncture, the defendants Milliken,et al. are

— The record reflects the Governor is an ex officio

member of the State Board of Education. He signed Act 48 into

law and he, after the recall of Detroit Board members, ap

pointed a majority of the interim members of that Board. Act

48, of course, not only rescinded the Board’s plan for pupil

assignment, it rescinded integrated regions and set up segre

gated regional boundaries. It also set up segregation by

pupil assignment methods. Bradley, supra, 433 F.2d 897, 901

(1970) .

-5

#

anticipating an order against them for the purchase of bus

ses or other expenditures to implement the future Detroit-

only remedy.

These defendants conclude from Edelman that:

[I]t is crystal clear, based on the

authority of Edelman' v. Jordan, supra, that

where, as here, the State of Michigan has not

consented to this suit in federal court, the

federal courts may not compel defendants

Milliken, et al. to provide State funds from

the State Treasury to pay for the acquisition

of busses for a Detroit-only desegregation

remedy. Brief of Defendant Milliken, et al.,

in support of their Motion to Dismiss, at 11.

These defendants, however, have overlooked the

important distinction the Court made in Edelman with respect

to prospective relief. After discussing a series of cases,

the Court concluded:

But the fiscal consequences to state

treasuries in these cases were the necessary

I result of compliance with decrees which by

their terms were prospective in nature.

State officials, in order to shape their of

ficial conduct to the mandate of the Court's

decrees, would more likely have to spend

money from the state treasury than if they

had been left free to pursue their previous

course of conduct. Such an ancillary effect

on the state treasury is a permissible and

often an inevitable consequence of the

principle announced in Ex parte Young, supra.

Edelman v. Jordan, U.S. , 39 L.Ed.2d

662, 675 (1974).

The argument of the defendants Milliken, et al. that

the Eleventh Amendment precludes Federal courts from compel

ling the payment of State funds from the State Treasury is

based on a misapprehension of the jurisdictional nature of the

Amendment. The Eleventh Amendment provides:

The judicial power of the United States

shall not be construed to extend to any suit

in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted

against one of the United States by Citizens

of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects

of any Foreign State.

The Amendment was proposed by the Congress and ratified by the

states in response to the Supreme Court's decision in Chisolm

v. Georgia, 2 Dali. 419 (1793), in which the Court held that

6

# #

federal jurisdiction under Article III of the Constitution,

encompassed a suit brought against a non-consenting state by

citizens of another state. Thus the Eleventh Amendment was

intended to clarify the intent of the Framers of the Consti

tution and to restrict the language of Article III, Section 2

which states that the federal judicial power shall extend to

"controversies... between a state and citizens of another

state."

The Eleventh Amendment limitation on suits against

states is different than the limitations arising under the

common law doctrine of sovereign immunity. While sovereign

immunity, where it applies, protects states from suit in any

forum absent consent, the Eleventh Amendment merely places

jurisdiction limitations on federal courts. Justice Marshall,

in his concurring opinion in Employees v. Department of Public

Health and Welfare, 411 U.S. 279, 294 (1973), articulatedI

this distinction:

The root of the constitutional im

pediment to the exercise of the federal

judicial power in a case such as this is

not the Eleventh Amendment but Art. Ill of

our Constitution....

■k k *

This limitation upon the judicial

power is, without question, a reflection

of concern for the sovereignty of the States,

but in a particularly limited context. The

issue is not the general immunity of the

States from private suit - a question of the

common law - but merely the susceptibility

of the States to suit before federal tribunals.

In Edelman v. Jordan, U.S. , 39 L.Ed.2d 662

(T974), the Court underscored the jurisdictional nature of the

3/Eleventh Amendment.

3/

...[I]t has been well-settled since

the decision in Ford Motor Co. v. Department

of Treasury, [323 U.S. 459 (1945)] that the

Eleventh Amendment defense sufficiently par

takes of the nature of a jurisdictional bar

so that it need not be raised in the trial

court. Edelman, supra, at 39 L.Ed.2d 681.

-7

• •

One limited purpose of the Eleventh Amendment is

to minimize the tensions of federalism "inherent in making

one sovereign appear against its will in the courts of the

other." Employees v. Department of Public Health and Welfare,

supra, 411 U.S. at 294 (Marshall, J. concurring).

The very object and purpose of the

11th Amendment were to prevent the indig

nity of subjecting a State to the coercive

process of judicial tribunals at the instance

of private parties. It was thought to be

neither becoming nor convenient that the

several states of the Union, invested with

that large residuum of sovereignty which had

not been delegated to the United States,

should be summoned as defendants to answer

the complaints of private persons, whether

citizens of other states or aliens, or that

the course of their public policy and the ad

ministration of their public affairs should

be subject to and controlled by the mandates

of judicial tribunals without their consent

and in favor of individual interests.

In re Ayers, 123 U.S. 443, 505-06 (1887). The Amendment there-

fpre denies federal courts the jurisdiction to decide certain

rights and liabilities when asserted against a state.

The jurisdictional bar of the Eleventh Amendment is

not absolute, however. A long line of cases, beginning with

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908), has established that suits

for injunctive relief against state officials may be heard in

federal courts, consistent with the Constitution, where the

complaint is that the official, acting in his capacity as

agent of the state, has engaged in unauthorized or unconstitu

tional conduct. In Ex parte Young, supra, and subsequent

cases, the Supreme Court harmonized this doctrine and the

Eleventh Amendment by holding that such a suit is against the

individual and not against the State, in spite of the fact

that injunctive relief ordered in such cases may require the

4/

expenditure of state funds and other state action.

4/

The Court in Edelman (39 L.Ed.2d 675) explicitly

noted that the kinds of relief authorized by Ex parte Young

would result in the expenditure of state funds:

State officials, in order to shape their

official conduct to the mandate of the Court’s

decrees, would more likely have to spend money

from the State Treasury than if they had been

left free to pursue their previous course of conduct.

-8-

Edelman v. Jordan, supra, marked a clarification

of the doctrine first enunciated in Ex parte Young. In

Edelman the Supreme Court held that while suits for prospec

tive injunctive relief against a state official are not barred

by the Eleventh Amendment, at least certain actions which seek

5/

the award of an accrued monetary liability are prohibited.

The Court found that there were essentially two

causes of action in Edelman: one for injunctive relief, and

one for monetary damages. On the facts before it, the Court

held that federal courts do not have jurisdiction to hear

6/

certain causes of action which closely resemble actions for

5/

It is notable that while the Court in Edelman

prohibits some kinds of monetary awards against states, nowhere

does it state that no form of expenditures may be ordered.

Indeed, the Court specifically recognizes that one of the in

evitable consequences of the adjudication of cases involving

state officials as defendants is that state funds will have to

be expended. The Court points out, however, that, n[s]uch an

ancillary effect on the state treasury is a permissible...

consequence of the principle announced in Ex parte Young,

supra." 39 L.Ed.2d 675.

£/

As Mr. Justice Marshall, in dissenting in Edelman,

noted (39 L.Ed.2d 690 n.2), the facts in Edelman did not pre

sent the question of whether the Fourteenth Amendment in any

way limits, or authorizes the Congress to limit, such immunity

as is conferred by the Eleventh Amendment. See, e.g., Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

2000e et seq. (Supp. II 1972) which authorizes suits by private

individuals and the United States against state and local

governments (42 U.S.C. 2000e(a)) for relief from employment

discrimination, including back pay (42 U.S.C. 2000e-5). See

also Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189, 196-197 (1974).

While there are considerations which suggest that the

Eleventh Amendment is limited in part by the Fourteenth, and

that issue must eventually be decided (perhaps in a case seek

ing "damages" for Fourteenth Amendment violations), we do not

feel that the Court must resolve that question to decide the

issue presented in this case. Of course, Section 718 of the

Education Amendments presents this same question in that in

effectuating the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress expressly auth

orized an award of attorney's fees against State school

authorities, cf. Mobil Oil Corp. v. Kelley, 493 F.2d 784

(Fifth Circuit, 1974) n.l at 786; Boston Chapter NAACP, Inc, v.

Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017, 1028-29 (First Circuit, 1974); Woods

v. Strickland, 43 U.S.L.W. 4293 (1975).

-9

monetary damages. "[A] suit that seeks the award of an ac

crued monetary liability which must be met from the general

revenues of a State..." is beyond the jurisdiction of the

federal courts. Edelman v. Jordan, supra, 39 L.Ed.2d 673.

The issue now before this Court is not, as it was

in Edelman, whether the district court had jurisdiction under

Article III of the Constitution, to decide the case. As

noted above, Ex parte Young established and Edelman confirmed

the jurisdiction of federal courts to hear actions for in

junctive relief against state officials. Rather, the question

presented here concerns whether a federal court, having juris

diction to decide a case, may order defendants to take action

which will cost them money. To state the question is to make

plain that Edelman itself has already, in plain and simple

language, answered the question, "yes."

In choosing to defend an action properly brought in

i

a federal forum, defendants must assume responsibility for

the normal incidents of such a suit, including the cost of

prospective relief, Court costs, witness fees, and attorneys'

Vfees.

V Indeed it follows inevitably from the doctrine of

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908), that states will be

requirecTTo expend funds in the court of litigating suits such

as those now before this Court.

10

#

CONCLUSION

The defendants suggest on the one hand that

they give large sums of money to the Detroit school

district and that it is wealthy compared to other dis

tricts. Such a simplicitic approach to school finance

can only be intentional in light of the extensive exper

ience school authorities throughout the nation have had

with big city systems. Large numbers of dollars may show

but the far higher per pupil costs because of the educa

tion deficits suffered by minority and poor youngsters

together with municipal tax over burden make such figures

entirely misleading. However, the absurdity of their

argument (footnore 2 at page 7 of their supplemental brief)

is shown by the statement that the Detroit district has

cut back on expenditures by "eighty million dollars" and

that their remains a projected "one-hundred and eighty

million dollar deficit that will have . . . to be elimi

nated by both further reductions in expenditures and obtain

ing additional revenue." Somehow or another they leap from

that point to the argument that the State Board and State

Treasurer should have no responsibility for assisting

Detroit in the desegregation process. Not since the French

Revolution has so cavalier a declaration of "let them eat

cake" been made by public officials.

This Court and the parties are faced with a

great responsibility for developing a sound and effective

remedy to desegregate the Detroit public schools within the

limits of the constitutional authority granted by the

United States Supreme Court. Even though such plan may

be on an interim basis, the interests of the children

involved must be paramount. Unfortunately, it would seem

that the state officials have no interest in Detroit’s

children, obviously because so many of them are black.

-11-

• #

In conclusion, plaintiffs respectfully submit that

there is absolutely no basis for the defendants' reading

of the Supreme Court's Decision with respect to the respons

ibilities of state school authorities for constitutional

violations within the Detroit school district. The Supreme

Court has accepted the findings of the District Court and

the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals with respect to the

state defendants.

Plaintiffs have never suggested that Allison

Green is charged with any of the de_ jure violations. He

was made a party simply because the defendants insisted

that it was necessary in order to obtain an order for pay

ment of state funds for both the desegregation panel and

the purchase of transportation equipment. That order for

purchase of transportation equipment was not directed at

metro relief only. While the order was vacated by the

Sixth Circuit in its en banc decision, it was with the

expressed suggestion that it could be reinstated when it

was necessary. Upon the reinstatement5the defendant Allison

Green will need to remain a party.

One further point illustrates the necessity

for keeping the state defendants as parties in the action.

Under Michigan law the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction of the State Board had, and has, the power

to require each board of education and the officers there

of to observe the laws relating to schools, and to compel

the observance of such law by appropriate legal proceedings,

'instituted in the proper courts under the direction of the

Attorney General. See MSA 15.2352. State law also imposes

the duty on the Superintendent of Public Instruction to do

all things necessary to promote the welfare of the public

schools and public education institutions. MSA 15.3355

sets forth that no separate school or department should be

kept for any person or persons on account of race or color.

Ultimately, the State Superintendent of Public Instruction

12

# #

has the power to remove from office, upon satisfactory

proof and proper notice, any member of a local school

board who shall have persistently and without sufficient

cause refused and neglected to discharge any of the duties

of his office, which obviously would include complying

with the probitions against racially separate schools or

the orders of this Court. See MSA 15.3253; MSA 15.3355.

With regard to the Eleventh Amendment argument

we respectfully submit that it is simply not applicable

to the prospective relief situation before this Court.

Plaintiffs submit that this Court should not only deny

state defendants’ motion but that it should consider requir

ing these defendants to assume a full measure of their own

affirmative duty to end school segregation.

RATNER, SUGARMON, LUCAS & SALKY

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

JOHN A. DZIAMBA

746 Main Street

P.O. Box D

Willimantic, Connecticut 06226

ELLIOTT S. HALL

2755 Guardian Building

500 Griswald Avenue

Detroit, Michigan

NATHANIEL JONES .

General Counsel

N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL DIMOND

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

Lawyers' Committee For Civil

Rights Under Law

733 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

Counsel for Plaintiffs

-13-

#

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing

Plaintiffs’ Brief In Opposition To The Motion To Dismiss

By Defendants’ Milliken, Et Al. has been served on all

counsel of record by depositing same to them at their

office by United States mail, postage prepaid, this 3

day of March, 1975.

-14-

Nos. 72-1809-14

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, Governor

of Michigan, etc.; Board of

EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

DETROIT,

Defendants-Appellants,

Iand

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor-Appellee,

and

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS et al.,

Defendants-Intervenors-Appellants

and

KERRY GREEN et al.,

Defendants-Intervenors-Appellees.

)

>

)

>

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

/

)

)

)

)

)

>

)

)

)

)

)

)

>

)

)

)

)

l-~t ji u { ̂ ;

U b* .

r. HEHMV ' K

ORDER

Jerk

Before PHILLIPS, Chief Judge, and WEICK, EDWARDS,

CELEBREZZE, PECK, McCREE, MILLER, LIVELY and ENGEL, Circuit

Judges.

Nos. 72-1809-14 - 2

In the decision of this court, reported at

484 F.2d 215 (1973), it was ORDERED that no costs be taxed

and that each party bear his own costs in the Court of

Appeals.

The Supreme Court reversed the decision of

this court in certain particulars in an opinion reported at

42 U.S.L.W. 5249 (July 25, 1974) and remanded the causes to

this court for further proceedings in conformity with the

opinion of the Supreme Court. This court has remanded the

causes to the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Michigan for further proceedings in conformity

with the opinion of the Supreme Court.'

The Supreme Court taxed costs in that court

against Ronald Bradley and Richard Bradley, by mother and

next friend, Verde Bradley, in the sum of $20,329.60.

Motions have been filed in this court for re-

faxation of costs in the Court of Appeals. This court con

strues the decision of the Supreme Court to reverse the

this

decision of/court in certain particulars but that the Supreme

Court did not reverse the decision of this court with respect

4

Nos. 72-1809-14 - 3

to the taxation of costs in the Court of Appeals. This

remains a question for determination by the Court of Appeals.

the responses thereto, it is ORDERED that all motions for

retaxation of costs be and hereby are overruled. It is

further ORDERED that no costs are taxed in the Court of

Appeals and that each party will bear his own costs in this

court.

Upon consideration of the various motions and -

Entered by order of the court.

i