Watson v. Jago Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

June 14, 1977

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Watson v. Jago Court Opinion, 1977. bddea965-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a6e900e2-27f0-4d73-9158-7204ab4bd949/watson-v-jago-court-opinion. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

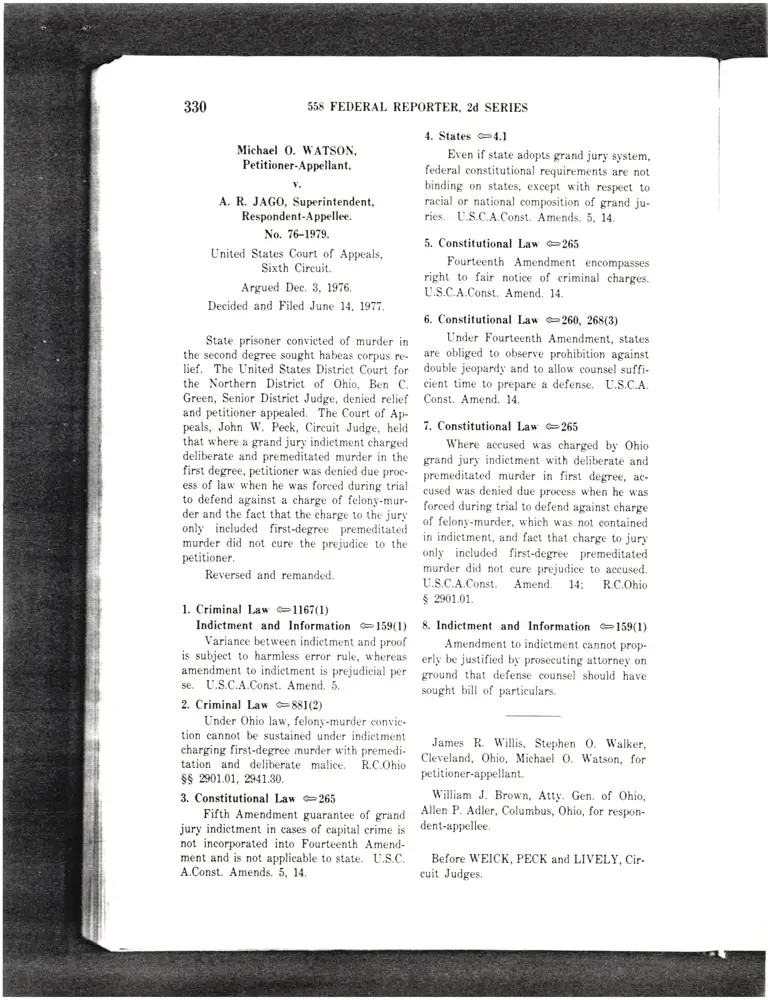

330 558 FEDERAL REPORTER.2d SERIES

Michael O. WATSON,

Petitioner.Appellant,

v.

A. R. JAGO, Superintendent,

Respondent-Appellee.

No. 76-1979.

United States Court of Appeals,

Sixth Circuit.

Argued Dec. 3, 1976.

Decided and Filed June 14. 1977.

State prisoner convicted of murder in

the second degree sought habeas corpus re-

lief. The United States District Court for

the Northern District of Ohio, Ben C.

Green, Senior District Judge, denied relief

and petitioner appealed. The Court of Ap-

peals, John W. Peck, Circuit Judge, held

that where a grand jun' indictment charged

deliberate and premeditated murder in the

first degree, petitioner was denied due proc-

ess of law when he was forced during trial

to defend against a charge of felont,-mur-

der and the fact that the charge to the jun.

onlf included first-degree premeditated

murder did not cure the prejudice to the

petitioner.

Reversed and remanded.

l. Criminal taw e115711;

Indictment and Information e.159(l)

Variance betrveen indictment and proof

is subject to harmless error rule, whereas

amendment to indictment is prejudicial per

se. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 5.

2. Criminal taw e88l(2)

Under Ohio law, felonl'-murder convic-

tion cannot be sustained under indictment

charging first-degree nrurder with premedi-

tation and deliberate malice. R.C.Ohio

ss 2901.01, 2941.30.

3. Constitutional [,aw 6265

Fifth Amendment guarantee of grand

jury indictment in cases of capital crime is

not incorporated into Fourteenth Amend-

ment and is not applicable to state. U.S.C.

A.Const. Amends. 5, 14.

4. States e4.l

Even if state adopts grand jury system,

federal constitutional requirements are not

binding on states, except u'ith respect to

racial or national composition of grand ju-

ries. U.S.C.A.Const. Amends. 5, 14.

5. Constitutional Law c=265

Fourteenth Amendment encompasses

right to fair notice of criminal charges.

U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14.

6. Constitutional Law e260, 268(3)

L]nder Fourteenth Amendment, states

are obliged to observe prohibition against

double jeopardv and to allou' counsel suffi-

eient time to prepare a defense. U.S.C.A.

Const. Amend. 14.

7. Constitutional Law F265

Slhere accused was charged by Ohio

grand jur.v indictment with deliberate and

premeditated murder in first degree, ac-

cused u'as denied due process when he was

forced during trial to defend against charge

of felonl'-murder, which \r'as not contained

in indictment, and fact that charge to jury

onll- included first-degree premeditated

murder did not cure prejudice to accused.

U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14; R.C.Ohio

s 2901.01.

8. Indictment and Information Fl59(l)

Amendment to indictment cannot prop-

erll be justified br prosecuting attornel'on

ground that defense counsel should have

sought bill of particulars.

James R. \4'illis, Stephen O. Walker,

Cleveland, Ohio, Michael O. \4'atson, for

petitioner-appellant.

\\ illiam J. Brou'n, Atty. Gen. of Ohio,

Allen P. Adler, Columbus, Ohio, for respon-

dent-appellee.

Before WEICK, PECK and LIVELY, Cir-

cuit Judges.

jurl'system,

ts are not

h respect to

of grand ju-

5. 14.

encompasses

charges

268(3)

nt, states

ition against

counsel suffi-

U.S.C.A.

by Ohio

liberate and

degree, ac-

when he was

inst charge

contained

to jury

premeditated

to accused.

; R.C.Ohio

el59(l)

cannot prop-

attorney on

should have

O. Walker,

Watson, for

of Ohio,

for respon-

VELY, Cir-

WATSON v. JAGO

Clte as 558 F.2d 330 (1977)

JOHN W. PECK, Circuit Judge.

Appellant Michael Watson was indicted

by a Cuyahoga County, Ohio, grand jury for

deliberate and premeditated murder in the

first degree, in violation of former section

2901.01 of the Ohio Revised Code. At trial,

appellant elaimed self-defense. The jury

found appellant guilty of the lesser included

offense of murder in the second degree, and

appellant was sentenced to life imprison-

ment. After appealing to the Cuyahoga

County Court of Appeals and to the Ohio

Supreme Court, appellant sought collateral

review of his conviction in the federal dis'

trict court by petition for writ of habeas

corpus. The district court, however, denied

the petition.

Appellant has brought this appeal, mak-

ing several arguments in support of his

petition.t We reach only one,2 that appel-

lant was denied due process of law under

the Fourteenth Amendment when he was

forced during the state court trial to defend

against a charge of felony'murder, which

was not contained in the indictment. Be-

cause we agree with appellant on this issue,

we reverse and remand the case to the

district court with instructions to grant the

writ of habeas corpus.

l. Appellant presented to the district court and

to this Court four contentions. First, due proc-

ess \\'as denied appellant when the prosecutor

introduced, as substantive proof of guilt, testi-

monl'shou'ing that appellant had exercised his

right to remain silent at the time of arrest'

Second, due process and effective assistance of

counsel u'ere denied appellant when he '*'as

forced to defend against charges not brought

bl the grand ju4. Third, due process was

denied appellant u'hen the prosecutor asked

inflammatory questions \'!'ithout a reasonable

belief that such questions u'ould produce ad-

missible evidence. Fourth, due process tilas

denied appellant u'hen the state tnal coun re'

quired him to prove affirmativel5', bl the pre-

ponderance of the evidence, self-defense.

2. Appellant's fourth contention, regarding the

burden of proof he had to shoulder on the issue

of self-defense, \r'as never presented to the

slate courts. Also, appellant's third conlen-

tion, regarding prosecutorial misconduct' u'as

not presented in the application for leave to the

Ohio Supreme Court. with respect to these

contentions, appellant apparently has not ex-

331

On February 6, 1973, in the late after-

noon, appellant and a friend, John Bell,

entered the store of a Cleveland, Ohio gro-

cer, William Dallas. Bell asked the grocer's

wife, who was working in the store along

with her husband, for a six-pack of beer'

Mrs. Dallas got the beer from the cooler

and set it on the counter. William Dallas

then came over and asked Bell for some

identification to show that he was of age to

buy the beer. A conversation concerning

credentials followed. The conversation

ended when appellant drew a pistol and

shot Mr. Dallas twice. One bullet struck

Dallas in his left arm' The other bullet

struck Dallas in the head, killing him. Mrs.

Dallas witnessed the shooting.

According to Mrs. Dallas, immediatell

before the shooting. appellant had said to

Mr. Dallas that he had credentials and had

asked whether Mr. Dallas wanted to see

them. According to appellant and Bell,

however, Mr. Dallas had pulled a gun, and

appellant claimed that he had fired in self-

defense. Most of the store owners in the

area were armed, and on that daY, Mr.

Dallas had carried a gun in the pocket of

his white butcher-t1'pe apron. The poliee

later found the gun owned b1' Mr. Dallas on

the floor, under the victim's bodl'. That

gun had not been fired.

hausted his state remedies Picard t'. Connor.

404 U.S 2iO, 92 S.Ct. 509. 30 L.Ed.2d 438

(1971). Appellant did exhaust hrs state reme-

dies as to his first contention. that the prosecu-

tor's eltcitation of testimon)' from a police de'

tective sho\\'rng that appellant had exercised

his rights to remain silent and to retain counsel

at time of arrest \\'as introduced as substantive

proof of guilt and thus. in vieu-of the circum-

stances of the questioning. \r'as, under Griffrn

v. California.380 U.S. 609, 85 S,Ct. 1229. 14

L.Ed.2d 106 (1965). harmful unconstitutional

prosecutorial comment upon an accused's as-

senion of his constitutional rights [as distin-

guished from proof of an accused's silence at

time of arrest offered for impeachment pur-

poses, held unconstitutional in Do.l{e v. Ohio,

426 U.S. 610. 96 S.Ct. 2240, 49 L.Ed'2o 9l

(1976)1. \f,'e have not reached that contention,

hou'ever, because of our disposition of the case

on the ground that appellant was forced to

defend against a charge of felon.'--murder when

the indictment specified only premeditated first

degree murder.

332

Imrediately after the shooting, appellant

and Bell fled the scene withoutlhe beer in

a red 1964 Cadillac, which had transported

appellant and Bell to the store and which

had carried two other friends. A descrip_

tion and the license plate number of the

automobile were given to the police by a

witness in the vicinity of the store. A

couple of hours later, the automobile was

stopped. Three males were arrested, but

appellant escaped on foot. Six days iater,

on February 12, lg71, appellant sr...nd"..j

to the police.

Appellant was indicted for deliberate and

premeditated first degree murder onlv.

Nevertheless, at the state court trial, the

prosecutor in his opening statement, after

reading the indictment for deliberate and

premeditated murder, asserted that:

558 FEDERAL REPORTER,2d SERIES

the evidence will

appellant u'ho waited in the Cadillac when

t}e k-illing took place; peter Becker, u po_

lice detective who interrogated Ford afLr

the shooting; and a police officer who ar_

nued at the scene of the crime shortly after

the killing. Much of the questioning fo_

cused on the possible robber1..

When the prosecution stated that it

would rest its case, defense counsel, out of

the jurl's hearing, moved to withdraw the

charge of first degree murder from the

jur.v's consideration. Defense counsel ar-

gued that there was no evidence to support

a pos-sible jury verdict of first degree

-mur_

der, first, because there was no evidence of

premeditation or deliberation on appellant,s

part and secondly, because there was no

evidence to show the commission of a rob_

bery. The prosecutor disagreed, responding

that the evidence did shou.u p.ur.ditut"i

killing and that he had proven a prima facie

case of robbery. The Court denied the de_

fense motion.

After a short recess, the proseeutor in

proceedings between the Court and counselin the Court's chambers, requested the

Court not to charge the jur.v on iirst degree

felon.r'-murder. The prosecutor stated that

the proof showed that some of the elemenlq

of armed robber.v u.ere present and that

such facts were reler.ant u.ith respect to the

eomplete circumstances of the case.

Defense counsel immediatell. protested.

He reminded the Court that at the start of

the trial he had moved for the exclusion of

anl reference to a felonl.-murder because

the indictment did not mention felonv_mur_

der. He further argued that because the

Court allou.ed the trial to proceed with thejnclusion of the felon.t.-murder charge and

because the defense had patterned its cross_

examination in large part on the refutation

of inferences supporting a charge of felonl.-

murder. to drop the felonr.-murder charge

u'ould be prejudicial since it would preclule

the defense counsel from talking about

u'hat he had tried to establish on .=.o.r**_

amination.

The prosecutor replied that the effect of

not charging the jury on felony-murder was

"simpll' to remove what basically and nor_

convince you beyond a reasonable doubt

that this man Watson [appellant] did info:l malieiously, p.uruditutir"iy and

while in the act of a robbery murder

Willie Dallas."

. Defense counsel, before making his open_

ing statement, moved to dismiss"the indi.t_

ment. He argued that it was an infringe_

ment of a defendant's right to notice of

crim-inal charges to be brought against him

b1, the State for the prosecutor to present a

case on the basis of felony_murder u.hen the

indictment specified only a charge of first

degree murder with deliLerat. u,ia p..r.a_

itated malice and did not include u .tu.guof felon.r.murder. The prosecutor, when

asked by the Court to reply to this argu_

ment, stated that premeditated murder Jnd

felonv-murder \.\ere both first d"gr"e ,r.-

der and that the indictment, b1. charging

first degree murder, did not hare to ir.;;;;

a statement that the indictment was for

felon.r'-murder for a defendant to be prose_

cuted on that charge. The trial court over_

ruled the motion to dismiss, and the trial

proeeeded with the presentation of the

State's case.

The prosecutor called several u.itnesses:

Mrs. Dallas, the wife of the victim: a wit_

ness who was near the scene of the crime;

Willie Waldon and Gerald Ford, friends of

ladillac when

Becker, a Po-

Ford after

icer n'ho ar-

shortll'after

ioning fo'

ed that it

nsel, out of

ithdraw the

rr from the

counsel ar-

to support

degree mur-

evidence of

appellant's

was no

of a rob-

, responding

meditated

prima facie

Lied the de-

tor in

and counsel

the

first degree

stated that

the elements

and that

:s;rcct to the

casr.

r' protested.

the start of

exclusion of

.ler because

felonv-mur-

lrccause the

td u'ith the

charge and

,d its cross-

refutation

of felony-

charge

preclude

king about

on cross-€x-

effect of

was

tllv and nor-

II'ATSON v. JAGO 333

Cite as 558 F.2d 330 (1977)

mally would [have] be[en] one count of the indictment, and (2) whether, if there was a

indictment." (State Court Trial Transcript constructive amendment, it violated appel-

1?1.) The prosecutor denied that there lant's constitutional rights under the Four-

could be prejudice in removing that one teenth Amendment in this state court, as

count since there was evidence to support a opposed to federal court, trial.

verdict of deliberate and premeditated first

degree murder. The evidence of a robbery

was characterized as "ancillarY" to the de-

liberate and premeditated murder.

The Court agreed with the prosecution

and made a tentative ruling that the jury

would be charged only on deliberate and

premeditated first degree murder' Defense

counsel stated for the record that it was a

strange situation for the State to start out

by saying that it would prove felonl'-mur-

der along with premeditated murder, to

deny that there had to be a separate indict-

ment for felony-murder from premeditated

murder, to spend a great part of its case

trying to prove felony-murder, and then,

after resting its case, to seek withdrawal of

the felony-murder charge and admit that a

separate indictment was needed for felony-

murder. Nevertheless, the Court adhered

to its tentative decision to charge onll'de-

liberate and premeditated first degree mur-

der.

The trial proceeded with the defense call-

ing appellant and John Bell and the prose-

cution calling Mrs. Dallas in rebuttal. Af-

ter the Court denied certain defense mo-

tions, the Court charged the jury on deliber-

ate and premeditated first degree murder

as charged in the indictment. The jurl'

found appellant not guilty of deliberate and

premeditated first degree murder but

guilty of the lesser included offense of

second degree murder.

Appellant appealed unsuccessfully to the

Cuyahoga Countl', Ohio Court of Appeals

and to the Ohio Supreme Court. His case is

now before us because the district court

denied his petition for a writ of habeas

corpus. The question which we reach deals

with the fact that appellant was forced to

defend against a charge of felonl'-murder

that was not brought by the grand jurf in

the indictment. There are two main issues

with respect to this question: (1) whether

there was a constructive amendment to the

II

Under the Fifth Amendment's provision

that no person shall be held to answer for a

capital crime unless on the indictment of a

grand jury, it has been the rule that after

an indictment has been returned its charges

may not be broadened except by the grand

jury itself. Stirone v. United States, 361

Li.S,212, 80 S.Ct. 270,4 L.Ed.?i 252 (1960);

Ex Parte Bain, l2l U.S. 1, 7 S.Ct. 781, 30

L.Ed. 849 (1887). See .Russel/ v. United

Stares, 369 U.S. i49, 770,82 S.Ct. 1038, 8

L.Ed.2d %0 (1962); United States r. .N'orn's,

281 Lr.S. 619,622,50 S.Ct. 4?A,74 L.Ed. 10?6

(1930). ln 188?, the Supreme Court in

Bain, supra,121 U.S. at 9-10, 7 S.Ct. 781,

held that a defendant could only be tried

upon the indictment as found by the grand

jury and that language in the charging part

could not be changed without rendering the

indictment invalid. In Stirone, supra, 361

U.S. at 21?, 80 S.Ct. at 273, the Supreme

Court stated Lhal Bain "stands for the rule

that a court cannot permit a defendant to

be tried on charges that are not made in the

indictment against him." This rule has

been reaffirmed recentll' several times in

this Circuit. L:nited Stares v. Maselli, 534

F.zd 1197, 1201 (6th Cir. 19?6); United

States r'. Pandilidis, 5% F.zd M4 (6th Cir'

19?5), cert. denied,4% tl.S. 933, 96 S.Ct.

1146, 41 L.Ed.2d 340 (19?6). Although the

language in Bain is broad, it has been rec-

ognized Lhal Bain and Stirone do not pre-

vent federal courts from changing an in-

dictment as to matters of form or surplus-

age. .Bussel/ r. L'nited States, supra, 369

U.S. at 770,82 S.Ct. 1038; United Srates r'.

Hall, 536 F.2d 313, 319 (10th Cir. 1976);

L'nited States r,. Dau'son,516 F.2d 796, 801

(gth Cir.), cert. denied,423 U.S. 855, 96 S.Ct.

104, 46 L.Ed.zd 80 (19?5); Stewart v. Unit-

ed States, 395 F.2d 484, 487-89 (8th Cir.

1968); United States r'. Fruchtman, 427

F.2d 1019, 1021 (6th Cir.), cert. denied,400

u.s. 849, 91 S.Ct. 39, 2'i L.Ed.zd 86 (1970);

United Srares r'. Huff,bt? F.zd 66 (Sth Cir.

1975).

ln Gaither v. United Stares, l3l U.S.App.

D.C. 154, 413 F.2d 1061, 10?1 (1969), this

definition of an amendment prohibited br.

Stiro.ne and Bain, as opposed to the concept

of a variance in proof from the indictment,

appears:

An amendmert of the indictment occurs

when the charging terms of the indict-

ment are altered, either literallr or in

effect, by prosecutor or court aiter the

grand jury has last passed upon them. A

variance occurs when the charging terms

of the indictment are left unaltered, but

the evidence offered at trial pror.es facts

materially different from those alleged in

the indictment.

These definitions have been quoted u-ith

approval by several courts of appeal. Unit_

ed States v. Pelose, bg8 F.2d 41, 45 n. g (2d

Cir. 1976); United Srares r.. Somcrs, 496

F.zd 7?3, 743 n. 38 (Bd Cir.), cert. tlenied,

419 U.S. 832, 95 S.Cr. 56, 42 L.Ed.zd 58

(19?a); United Srates r.. Bursten,45B F.2d

605, 607 (Sth Cir. 19?l), cerr. tleniert, 409

u.s. 843, 93 S.Cr. M, u L.Ed.zd 83 (1972).

tl] This distinction between an amend-

ment and a variance is critical because a

variance is subject to the harmless error

rule, Berger v. United Srates, 295 L.S. ?g,

82, 55 S.Cr. 629, 79 L.Ed. 1311 (1935),

whereas an amendment prohibited b1. Str-

rone and Bain is prejudicial per se. L'nited

States r'. Bryan, 488 F.2d gE, 96 (3<l Cir.

1973); United Stares r. DeCat.alcante. 410

F.2d 126/., 1271 (3d Cir. 1971); Gaither r.

United States, supra, 4lB F.2rl at 1072.

Sometimes, hou'ever, there is a problem in

identifying u'hen an amendnrent is made to

an indictment. That protrlem occurs ivhen

the charging terms of an inrlictment have

not been literalh' changed but havc treen

,effectively altered b1'er.ents at trial. L'nir-

ed States r'. Somers, supra, 4g6 F.Zd at 741.

3. Former Ohio Revised Code \ 2901.01 pror.id_

ed as follows:

No person shall purposell. and either of

deliberate and premeditated malrce. or b]

means of poison, or in perpetrattng or at_

558 FEDERAL REPORTER.2d SERIES

stirone v. uniled srares, supra, 361 u.S.

212, 80 S.Ct. 270, 4 L.Ed.?n 252, involved a

"constructive" amendment. The defendant

was found guiltl', but the Supreme Court

reversed the conviction, stating that the

defendant's right to be tried onl-v on

charges presented in an indictment re-

turned h.r' a €trand jurl' had been destrol,ed

even though the indictment had not been

formallv changed. Stirone 1.. United

States, supra,361 U.S. at zti,B0 S.Ct.2?0.

Under Stl'rone, the question to be asked

in identifying a consrructi\.e amendment is

u'hether there has been a modification at

trial in the elements of the crime charged.

Ltnited States r,. Somers, supra,4g6 F.2d at

744 Linited Srates r.. DeCavalcante, supra,

140 F.zd at l2i2; L:nited Srates v. SrJyer-

man, 430 F.2d 106, 111 (2d Cir. 1970), cerl.

denied, 402 U.S. 958, 91 S.Ct. 1619, 29

L.Ed.2d 123 (1971). Such a modification

u'ould result in a constructive amendment.

Of course, if a different crime u.as added to

the charges against u.hich the defendant

had to meet, there rrould have been a con-

structive amendment. L:nited States r-. Slr

Kue Chin, 534 F.2d 1082, 1036 (2d Cir.

1976); L'nited.Srares r'. HolL bn F.2d 981

(4th Cir. 19?5).

I2l Appl.ring this test to the present

case, there clearll' $'as a constructir.e

amen<lment made tir the indictment if ap-

pellant is correct in stating that felon-r--

murder u'as added to the charges against

u'hich alrpellant had to defend at the state

trial. L nder Ohio Iarr', 3 felonr.-murder

conliction cannot be sustained under an

indictment charging first <legree murder

u'ith premeditated and deliberate. malice.

The Ohio Supremc Court in Srate r.. Fergu-

son, 175 Ohio Sr. 390. 195 \.E.2d ?91 (1964),

hcld that although felon.r.-murder and pre-

mcditated murder u'ere both included in the

same parag'raph of the then eristing first

degree murder statute,3 felonl.-murder and

tempting to perpetrate rape, arson, robben.

or burglarr', kill another

\f,rhoever vtolates this section rs guiltl. of

murder in the frrs( degree and shall be pun-

ished bl death unless the jury. rrying rhe

accused recommends mercl , in u.hich case

334

pra, 361 U.S.

i2, involved a

he defendant

rpreme Court

ing that the

ied only on

dictment re-

:en destroyed

had not been

United

80 s.ct. 270.

r to be asked

rmendment is

odification at

rime charged.

a, 496 F.2d at

',lcante, supra,

rtes r'. SrJrer-

r. 1970), cert.

cr. 1619, 29

modification

l amendment.

was added to

he defendant

e been a con-

I States r'. Sir

1036 (2d Cir.

529 F.2d 981

the present

constructive

ctment if ap-

that felony-

arges against

i at the state

ielonl'-murder

red under an

:gree murder

rerate malice.

tate v. Fergu-

2d 794 (1964),

rder and pre-

ncluded in the

existing first

y-murder and

arson, robbery,

ion is guilty of

d shall be pun-

iur.r' trying the

in u'hich case

LIJ:3X*,JI$g 335

premeditated murder constituted separate fied that he saw either appellant or Bell

iii.nr"r. For appellant to be convicied of with something under his arm and that he

felony-murder lie *ould have had to be thought that the bar next to the Dallas

inai.La for that crime. grocer] store had been robbed'

The question that the present case poses After brief testimonl' from an interven-

is whether, under the facts of this case, ing witness, the prosecution called Gerald

r"torv-.r.a.r was effectively added to the Ford. The prosecution's sole purpose in

.i,"rg". against which appellant had to de- calling and vigorously questioning Ford was

fend. The district ,or.i t.ta that there to prove a robbery. After the prosecution

was no factual basis from which to conclude was granted permission to cross-examine

an amendment had been made to the indict- Ford as a hostile witness, he was asked

ment, even though the prosecutor, during whether in the car after the shooting if

the Shte's .ur", lrproperly tried to prove appellant had admitted to his friends that

iutony-ru.a"r.

'Thedistrici

court reasoned, in the store he told William Dallas that it

and on appeal appellee contends,{ that there was a "stickup." Ford first denied that

was no amendment to the indictment be- appellant had said anything about a stickup

*r." the prosecutor's opening statement and then asserted that he could not remem-

included a ieading of the inAlctment and ber. The prosecutor read from Ford's

because the trial court's charge to the jurl' statement, which was taken b} police after

was only for deliberate and premedi;ted he was arrested and which incriminated the

first degree murder and did not include a appellant. Ford said that he had signed the

;h;.g; if felony-mu.der. s[atement but repeated his claim that he

However, the prosecution and defense did not remember that he had stated any-

counsel throughout the State's case relied thing about a robbery' In permitting the

on the trial court's ruling and sought re- prosecutor to cross-examine Ford as a hos-

spectively to prove and negate commission tile witness' the Court gave as its "principal

of a robbery at the time of the shooting' reason" for allowing the cross-examination

On cross-examination, defense counsel elic- the fact that the State in its opening state-

ited from Mrs. Dallas the statements that ment contended that the killing took place

neither appellant nor Bell said "stick it up," during an attempted robbery'

that neiiher appellant nor Bell gave an)' \4'hen cross-examined b.v defense counsel,

indication thaf thel- were robbing or at- Ford denied that there '*'as an)' conversa-

tempting to rob the store, that neither ap- tion among the four friends in the Cadillac

pellant nor Bell took an1'thing of value in about an effort to rob the g"ocer] store'

ihe store, and that neiiher appellant nor Ford also testified that the statement he

Bell acted-until the shooting--as other gaYe \4as made under pressure of possible

than normal customers. criminal charges against him at a time

In response, the prosecution called Henrl' u'hen he was not free to leave the police

Towns, a witness in the vicinitl' of the station'

store. Towns desc..ibed seeing appellant The prosecution also called two police de-

and Bell run up a street awqy fiom the tectiles, Peter Becker, who was one of the

area of the grocery store and enter a wait- two officers who took Ford's statement'

ing red tgOi Caaittac, which quickly sped and William Vargo, who was an officer who

aiay from the scene. Towns turther teiti- arrived at the scene of the crime shortly

the punishment shall be imprisonment for

life.

Murder in the first degree is a capital crime

under Sections 9 and l0 of Article l, Ohio

Constitution.

4, Appellee also responds to appellant's- argu'

meni Uy stating that it is not properl.v- before us

because it was not raised in the Ohio courts

and that it is a different argument than present-

ed in the district court. Appellee's position is

u'ithout merit and refuted by a revie$' of the

record. Appellant raised his objection to the

constructive amendment before the Ohio courts

and the district court, and it was the same

objection as presented here on appeal.

336 558 FEDERAL REPORTER.2d SERIES

after the killing. 0n direct examination,

Becker was questioned about the nature of

his interrogation of Ford to shou' that the

statement was freell- given. On cross-ex-

amination, Becker admitted that Ford ner.-

er said that an.r of his three companions in

the Cadillac on the da1'of thc shooting ever

stated to Ford that appellant and Bell had

the intention of robbing the store. Vargo

admitted on cross-examination that u'hen

he turned over the dead bodl' of William

Dallas, he saw that the right hand of Dallas

was inches away from where his gun la1. on

the floor. Shortly thereafter, the prosecu-

tion stated that it would not ask that the

Ford statement be formalll received into

evidence.

It thus clearly appears that the strategl-

of counsel u'as vitalll' affected b1- the trial

court's ruling allowing the prosecution to

prove felonl'-murder. The trial proceeded

on the basis that, under the Ohio first de-

gree murder statute, former Ohio Revised

Code $ 2901.01, to uphold a conviction of

first degree murder, the State had to prove

that appellant purposell' killed another per-

son and that appellant either killed u.ith

deliberation and premeditation or killeti

during the commission of a felonl-. .State r'.

Farmer, 156 Ohio St. 214, 102 N.E.z(l lt

(1951); Robbins r.. Srare. E Ohio St. 131

(1857); Note, The Felonl' Nlurder Rule in

Ohio. 17 Ohio St. L.J. 130 (1956). A major

portion of the trial, during the State's case,

concerned the possible robberl' and not

facts going to a determination of premedi-

tation. The trial court ruling that the

State could prove felonl.-murder '*'as crit-

ical to defense strategJ- because appellant

at trial claimed self-defense, u.hich is not a

defense to felonl'-murder.

The trial court thus permitted a consrruc-

tive amendment and then, upon request of

the prosecution, permitted a u.ithdrau'al of

the amendment. As the prosecutor aptl.i.

put it, u'hen he asked the trial court not to

charge the jurl' on felonr-murder, the ef-

fect was "simpll' to remove u'hat basicall-v

and normalll' u'ould [have] be[en] one count

of the indictment." The Ohio grand jurl'

had not put such a felonv-murder count in

the indictment.

IIl

Because the lau of a constructive amend-

ment has developcd in the context of feder-

al court trials and the Fifth Amendment, it

must be determined whether appellant,s

constitutional rights under the Fourteenth

Amendment were violated in his state court

trial. The problem stems from the fact

that the rule against amendments contained

in Ex Parte Bain, supra, 121 U.S. 1, ? S.Ct.

781, 30 L.Ed. 849, and Strrone v. United

States, supra, 361 U.S. 212, 80 S.Ct. 2?0, 4

L.Ed.2d 252. rests on the Fifth Amend-

ment's guarantee of a grand jury indict-

ment before a person can be held to ansuer

for a capital crime. Ex Parte Bain, supra,

121 U.S. at 10, 13, ? S.Cr. at ?86, 288, made

clear the Pifth Amendment basis for the

rule:

If it lies within the province of a court

to change the charging part of an indict-

ment to suit its ou.n notions of what it

ought to have been, or what the grand

jun' u'ould probablv have made it if their

attention had lrcen ca]led to suggested

changes. the great importance which the

common la\r' attaches to an indictment b1,

a grand jun', as a prerequisite to a pris-

oner's trial for a crime, and u'ithout

u'hich the Constitution sa\.s, ',no person

shall be held to answer," ma1- be frittered

au'av until its value is almost destroved.

. IA]fter the indictment \r'as

changed it u'as no longer the indictment

of the grand jur.r' u'ho presenr.ed it. An].

other doctrine *'ould place the rights of

the citizen, rvhich were intended to be

protecterl b.v tht constitutional pror.ision,

at thc. mercl or control of the court or

prosecuting attorne.\'; for, if it be once

held that change-s can be made by the

consent or the order of the court in the

bodl of the indictment as presented by

the grand jurl', and the prisoner can be

called upon to answer to the indictment

as thus changed, the restriction which the

Constitution places upon the power of the

court, in regard to the prerequisite of an

indictment, in reality no longer exists.

WATSON v. JAGO

Clre 8s 558 F.2d 330 (1077)

337

ive amend-

it of f"d"t-

indment, it

appellant's

Fourteenth

state court

h the fact

I contained

[. r, t s.ct.

v. United

.C1.270, 4

Amend-

indict-

to answer

supra,

788, made

for the

of a court

an indict-

of what it

the grand

it if their

suggested

which the

ictment by

to a prls-

without

"no person

frittered

destroyed.

nt was

indictment

it. AnI

e rights of

.ed to be

provision,

court or

it be once

b1' the

rt in the

bv

can be

indictment

which the

of the

isite of an

t3] The Fifth Amendment's guarantee

of a grand jury indictment in cases of capi-

tal crimes, however, has never been incorpo-

rated into the Fourteenth Amendment and

hence is not applicable to the states' In

Hurtado t'. California,ll0 U.S' 516, 4 S'Ct'

111, 28 L.Fd.lS2 (1884), the Supreme Court

held that the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment did not require a

grand jury indictment in a prosecution by

itr" Stut of California for a capital crime'

While it is true Lhat Hurtado once stood in

a line of Supreme Court eases that refused

to incorporate Bill of Rights guarantees

relating to eriminal procedure into the

Fourteenth Amendment and while it is true

that such older precedent' except for Hur-

tado, has been overruled and most of the

Bili of Rights guarantees relating to crimi-

nal procedure have been incorporated into

the Fourteenth Amendment as fundamen-

tal rights,s Hurtado remains good law'

Branzburg v. Hayes,408 U.S. 665,688 n 25'

92 S.Ct. 2646, 33 L.Ed.2d 626 (1972); A/ex-

ander v. Louisiana,405 U.S. 625, 633' 92

s.ct. 1221, 31 L.Ed.zd 536 (1972); Picard v'

Connor,404 U.S. 270,273,92 S.Ct' 509' 30

L.Ed.2d 438 (19?1); Beck v. ll'ashington,

369 U.S. 541, 545, 82 S.Ct. 955, 8 L.Ed'2d 9E

5. Mapp r'. Ohio,367 U.S. &3, 8l SCt 16E4' 6

L.Ed); l08l (1961), acknoq'ledged that the

right to be free from unreasonable searches

an'd seizures had been incorporated in llblf t'

Colorado,338 U.S. 25, 69 S.Ct 1359' 93 LEd'

1782 (1949), and then incorporated the right to

have excluded from a criminal trial an1' evi-

dence illegalll'obtained, overruling V'olf t" Col-

orado. supra. on that point. Gideon r ' ll'ain'.

u'right. 3i2 u.s. 335. 83 s.ct 792. I L Ed 2d

799 (1963). incorporated the right to the assist-

ance of counsel and imposed the requtretneut

to appoint counsel in criminal cases. overrultng

Betrs'r'. Brad.r', 316 U.S. 455. 62 S Ct l252' 86

L.Ed. 1595 (1942). Mailor r. Hogan 376 L S

l.84 S.Ct. 1489, 12 L.Ed2d 653 (1964) incor-

porated the privilege against self-rnctiTllollT

and overruled Tu'ining r'. Nerl Jerser" 2l I l- S'

78, 29 S.Ct. 14, 53 L.Ed. 97 (190s) Benton t"

Marytand, 395 U.S. 784, 89 S Ct 2056' 23

L.Ed.2d 707 (1969), incorporated the guarantee

against double jeopardl and overruled el!<o;,

Connecticut,302 U.S 3l9, 58 S'Ct t49' 82

L.Ed. 288 (1937). Duncan r" Louisiana' 391

u.s. 145, 88 S.Ct. 1444,20 L.Ed-zd 491 (1968),

incorporated the right to jur)' trial, a1d

-a-c1o1d

ingto Duncan, supra,39l U S' at 148' 88 S Ct'

ti+ . tn re Oliver,333 U.S. 257. 68 S Ct 499' 92

(1962); Saunders v. Buckhoe,346 F.2d 558,

559 (6rh cir. 1965).

t4] In addition, even if a state adopts a

grand jurl' system, federal constitutional

requirements, binding in federal criminal

cases are not binding on the states, Alexan'

der v. Louisiana, supra,405 U.S. at 633, 92

S.Ct. 1221, except with respect to the racial

or national composition of grand juries'

Carter r'. Jurl' Commission, 396 U'S' 320,

330, 90 s.ct. 518, % L.Fa.zd 549 (1970).6

Thus, with respect to amendments, federal

courts have viewed their legality as "pri-

marill' a matter of state law'" United

Statei e.r' rel. lltojtycba v. Hopkins, 517

F.2d 420, 425(3d Cir. 1975). See Henderson

t-. Cardu'ell, 426 F.zd 150, 152 (6th Cir'

1970); Stone v. lltingo,416 F.zd 857' 859

(6th Cir. 1969).

81' statute, Ohio lau' allows certain

amendments. Ohio Revised Code S 2941'30

at the time of appellant's trial provided,

and now provides:

The court mal' at an1'' time before, dur-

ing, or after a trial amend the indict-

ment, information, or bill of particulars,

in respect to any defect, imperfection, or

omission in form of substance, or of any

tariance with the evidence, provided no

L.Ed. 682 (1948), incorporated the right to a

public trial. Ktopfer r'. Nonh Carolina' 386

L.s zre. 87 s.ct. 988, 18 L.Ed.2d I (1967).

incorporated the right to a speedl trial Point-

er r'. Ie.xas, 380 U S 400, 85 S Ct 1065' 13

L.Ed.2d 923 (1965). incorporated the right to

confront opposing rx'itnesses, and Washington

r'. Texas. 3-88 U.S. 14, 87 S.Ct. 1920, t8 LEdzd

l0l9 (1967), incorporated the right to compul-

son' process for obtaining

"\'itnesses'

6. In .-Ue.rander v. Lctttisiana.405 L S 625' 634'

92 S.Ct. 1221.31 L.Ed.2d 536 (1972) lDouglas'

J.. concurring). Jrtsrite Dotrglas argued that

Httnado r'. Calilornia. I l0 Lr.S 5l6 4 S Ct l I l'

2E L.Ed.232 (l8fi1). drd not suppon the propo-

sitlon that federal constitutional requlrements

\\'ere not obligator) once a state chose to adopt

the grand jur] svstem. Justice Douglas cited

Caner r'. Jury Conmission. 396 U S' 320' 90

S.Ct. 518. 24 LEd2d 549 (1970). u'hich did

appll federal consritutional requirements u'ith

r"ipl.t to the racial selection of members of a

grand jur1, in suppon of his position that once

a state chose to adopt a grand jury system'

federal constitutional requirements \[ere appli-

cable.

exists.

5s6 F.2d--4

338 558 FEDERAL BEPORTER,2d SERIES

change is made in the name or identitl' of

the c"rime charged. If an1' amendment is

made to the substance of the indictment

or information or to cure a variance be-

tween the indictment or information and

the proof, the accused is entitled to a

discharge of the jury on his motion, if a

jurl has been impaneled, and to a reason-

abli continuance of the cause, unless it

clearly appears from the whole proceed-

ings tiat [e has not been mis]ed or preju-

diced by the defect or variance in respect

to whici the amendment is made, or that

his rights will be fully protected b1' pro-

ceeding with the trial, or b1'a postpone-

ment thereof to a later da1 with the same

or another jury. In case a jury is dis-

charged from further consideration of a

case under this section, the accused was

not in jeopardy' No action of the court

in refusing a continuance or postpone-

ment under this section is reviewable ex-

cept after motion to and refusal b1' the

trial court to grant a new trial therefor,

and no appeal based upon such action of

the courf itutt l. sustained, nor reversal

had, unless from consideration of the

whole proceedings, the reviewing court

finds that the accused was prejudiced in

his defense or that a failure of justice

resulted.

In the present case the Ohio Rerised Code

S 2941.30 would not permit an amendment

ihat changed the indictment to add another,

different crime. See Breinig v' State, 124

0hio st. 39, 4243, 1?6 1{.E. 6?4 (1931):

Hasselv'orth r'. Alris, ?6 Ohio Law Abs' 238'

143 N.E.2d 862 (1956); Horsley v' 'Alris, 2E1

F.zd 440 (6th Cir. 1960). In no wal was

Ohio Revised Code S 2941'30 involved in the

present case. According to Breinig,. such. a

iar reaching amendment as occurred in the

oresent caie uould violate fundamental

iaws, cloaking the defendant with the right

under the Ohio State Constitution to "de-

mand the nature and cause of the aceusa-

tion against him." 1% Ohio St' at 42-43'

1?6 N.E.zd at 6?6.

More important to appellant's petition for

a writ of habeas corpus is the fact that an

amendment to an indictment in certain

cases can implicate rights under the United

States Constitution which are applicable to

the states, such as fair notice of criminal

charges, double jeopardy, and effective as-

sistance of counsel. See United States ex

rel. Wojtycha v. Hopkins, supra,51? F-2d

425. This Court in '[]nited States r" Pandili-

dis, supra,S%,F.2d at M8, recognized that:

. the rules governing the con'

tent of indictments, variances and

amendments are designed to protect

three important rights: the right under

the Sixth Amendment to fair notice of

the criminal charge one will be required

to meet, the right under the Fifth

Amendment not to be Placed twice in

jeopardy for the same offense, and the

rlgirt granted by the Fifth Amendment'

an'd sometimes b1' statute, not to be held

to answer for certain crimes except upon

a presentment or indictment returned b1'

a grand iury.

[5,6] There is no question that the

Fourteenth Amendment encompasses the

right to fair notice of criminal charges'

TIe Supreme Court in In re Oliver,333 U'S'

25i ,21i,68 S.Ct. 4e9, 92 L.Ed. 682 (1948)' in

dealing with the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, stated that:

A person's right to reasonable notice of a

charge against him, and an opportunttl'

to be heard in his defense-a right to his

da1- in court-are basic in our s1'stem of

jurisprudence.

Likewise, in Cole v. Arkansas,333 U'S' 196'

201, 68 S.Ct. 514, 51?, 92 L.Ed. M4 (1948)'

the Supreme Court declared that:

No principle of procedural due process is

morl clearly established than that of.no-

tice of the specific charge, and a chance

to be heard in a trial of the issues raised

b1' that charge, if desired, are among the

constitutional rights of every accused in a

criminal proceeding in all courts, state or

federal.

See United States r. Maselli, supra, 534

F.2d 119?, 1201; United States v' Beard,

436 F.zd 1084, 1086-88 (Sth Cir' 19?1); Sali-

nas v. [Jnited States, 277 F'21914,916 (gth

Cir. 1960). Also, under the Fourteenth - \-

Amendment, states are obliged to observe

rPPlrcsble

to

r ol crimlnsl

?ff('ctir.e &s-

tnl Slalc's e'r'-,a

Sl'i F'N

rc. r Pandili'

rfnrzrd that:

nrn! tht'con'

.nlnc('s and

to Protect

nght under

'rtr notice of

i tr rtquired

r thc Fifth

trrl tn'iee in

nrt. and the

,{mendment,

,,t to tx'held

ercept upon

n'turned bY

,n that the

nl[)asses the

nal charges.

rr t'r. 333 U.S.

613 (1918). in

llause of the

,l that:

r n(,tict of a

('l )[x)rtu nit]'

r right to his

ur srstem of

333 t'.S. 196,

I 611 (1948),

hat:

ue process is

r that of no-

rnd a chance

issues raised

t. among the

accused in a

rrts, state or

, supra, 534

es v. Beard,

l97l); Sa,li-

914, 916 (gth

Fourtrenth

I to observe

MATTER OF ERIE LACKAWANNA RY. CO.

Clre as 55E F.2d 3:i9 (t977)

the prohibition against double jeopard.v, L.Ed.2d 3ffi (19?0); Green v.

Benton v. Maryland, Bg5 L;.S. 784, 89 S.Ct. 855 U.S. 184, Tg S.Ct. 221,

2056,?3 L.Ed.zd 707 (1969), and allow coun- (195?).

sel sufficient time to prepare a defense.

Pou'ell v. Alabama,287 U.S. 45, 59, 53 S.Ct.

55, 7? L.Ed. 158 (1932).

[7, 8] To allow the prosecution to amend

the indictment at trial so as to enable t.he

prosecution to seek a conviction on a charge

not brought by the grand jury unquestiona-

bly constituted a denial of due process b1'

not giving appellant fair notice of criminal

charges to be brought against him.? See

DeJonge v. Oregon,299 U.S. 353, 362, 5?

s.ct. 255, 81 L.Ed. 278 (1937). As a matter

of law, appellant was prejudiced by the

constructive amendment. See Stt'rone r..

United States, supra, 361 U.S. 212, 80 S.Ct.

270, 4 L.Ed.zd 252; Ltnited States v. DeCa-

valcante, supra, 440 F.Zd l2M; Gaither v.

United States, supra,l34 U.S.App.D.C. 154,

413 F.2d 1061. The fact that the charge to

the jury only included first degree premedi-

tated murder according to the indictment

could not cure the prejudice to the appel-

lant. Furthermore, an amendment cannot

properly be justified by a prosecuting attor-

ney on the ground that defense counsel

should have sought a bill of particulars.s

Busse// v. United States, supra, 869 U.S. at

769-70, 82 S.Ct. i038; United Srate.. r'.

Norns, supra,28l U.S. at 622, S0 S.Ct. 42A.

The order of the district court is reversed,

and the case is remanded to the district

court with instructions to grant the writ of

habeas corpus, conditioned on the State's

right to retrl- the appellant. See Price r..

Georgia, 398 U.S. B2B, 90 S.Cr. 1?57, 26

7. Although not presented bl the facts of this

case, double jeopardl implications could har.e

been included because appellant's conviction

for second degree nrurder u'ould not preclude a

conviction for felonl -murder. Lovther r..,fla.,t-

v'ell, 347 F.2d 941 (6th Cir. 1965); Srare r'.

Trocodaro.40 Ohio App.2d 50, 317 N.E.2d 416

( I 973).

8. ln its unreported opinion, Stale t. V/atson.

No. 33036, June 27. 1974, rhe Cu1'ahoga Coun-

ty, Ohio, Court of Appeals stated that the con-

duct of the trial could be upheld on the basis

that the State could prove the lesser included

offense of involuntary manslaughter in first de-

gree premeditated murder. While it is true

that at the time of appeuant's trial, former Ohio

339

United States,

2 L.Ed.2d 199

In the Matter of EBIE LACXAWANNA

RAILWAY COMPANY, Debtor.

Appeal of CONSOLIDATED RAIL

CORPORATION.

No. 76-2417.

United States Court of Appeals,

Sixth Circuit.

Argued April 13, 1977.

Decided and Filed June 21, 19??.

The United States District Court for

the Northern District of Ohio, Robert B.

Krupansky, J., determined that Conrail was

not entitled to receive compensation for

serving as agent of the trustees of certain

railroad, and Conrail appealed. The Court

of Appeals, Weick, Circuit Judge, held that

Congress did not intend that Conrail should

be compensated for most of the functions it

performed as agent of trustees for railroad

pursuant to the Regional Rail Reorganiza-

tion Act. and thus amendments to agenc)

agreement providing for compensation to

Conrail as agent of trustees were not legal-

11' authorized.

Affirmed.

Revised Code g 2901.06 included involuntary

manslaughter. u'hich the Countl Coun of Ap-

peals defined as unintentional killing resulting

from the commission of an illegal acr, there is a

constitutional difference betu'een shou'ing an

illegal act as part of the surrounding circum-

stances of first degree premeditated murder

and seeking to convict a defendant for felonl.-

murder under an indictment for first degree

premeditated murder. In the latter situation, a

defendant has not been given fair notice. As

the present case illustrates, an illegal act is not

an element of first degree premeditated mur-

der.