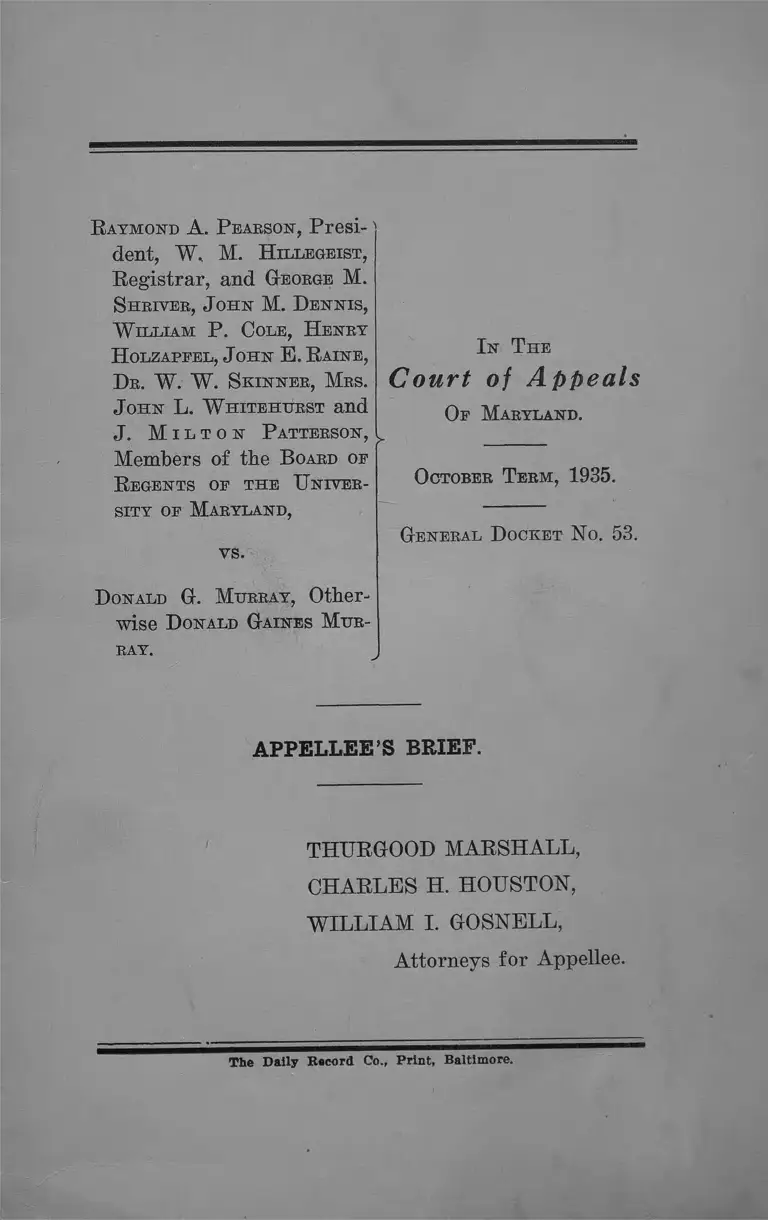

Pearson v. Murray Appellee's Brief

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1935

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Pearson v. Murray Appellee's Brief, 1935. 833764f5-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a72918b3-1540-4bfc-808d-74b59b143658/pearson-v-murray-appellees-brief. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

R aymond A. P earson. Presi

dent, W, M. H irregeist,

Registrar, and George M.

S hriver, J ohn M. D en n is ,

W irriam P. Core, H enry

H orzapeer, J ohn E . R aine ,

Dr. W . W . S k in n er , M rs.

J ohn L. W h itehurst and

J. M i r t o n P atterson,

Members o f the B oard oe

R egents oe th e U niver

sity oe M aryrand,

vs.

D onard G. M urray , Other

wise D onard G aines M u r

ray .

I n T he

Court of Appeals

O e M aryrand.

O ctober T erm , 1935.

G enerar D ocket N o. 53.

APPELLEE’S BRIEF.

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

CHARLES H. HOUSTON,

WILLIAM I. GOSNELL,

Attorneys for Appellee.

The Daily Record Co., Print, Baltimore.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Acts of Maryland:

P age

Acts of 1807, Chap. 53................................................ 10

Acts of 1812, Chap. 15A................................ ............ 11

Act of August 30, 1890................................................ 11

Acts of 1912, Chap. 90................................................9,13

Acts of 1920, Chap. 480.............................................. U

Acts of 1933, Chap 234 ............. .................... 9,14, 21, 22

Acts of 1935, Chap. 577........................................6, 21, 25

Board of Education v. Tinnon, 26 Kans. 1, 39 L. R.

A. 1020 ......................................................................... 15

Chase v. Stephenson, 71 111. 383, 385 .......................... 16

Clark v. Board of Trustees, 24 Iowa 266................. 15

Clark v. Maryland Institute, 87 Md. 643.......11,19, 30, 32

Cooley on Torts (Perm. Ed.) sec. 236 ........................ 12

Corey v. Carter, 48 Ind. 327 .......................................... 12

Cornell v. Gray, 33 Okla. 591........................................ 15

11 C. J. Civil Rights, sec. 10, p. 805 ............................ 12

Crawford v. District School Board, 68 Or. 388, 137

Pac. 217 ....................................................................... 15

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 346 ........................ 20

Foltz v. Hoge, 54 Cal. 28 ................................................ 15

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78, 84 ............................ 28

Lowery v. Board of Trustees, 52 S. E. 267................. 19

Maddox v. Neal, 45 Ark, 121, 124 .............................. 16

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. Co.,

235 U. S. 151, 160....................................................... 30

11

P age

Patterson v. Board of Education, 11 N. J. Mi sc. 179 17

People ex rel. Bibb v. Mayor, 193 111. 309, 61 N. E.

1077, 56 L. R. A. 9 5 ........ ................................... 15,19, 29

Piper v. Big Pine School District, 193 Cal. 664...12,19, 29

5 Ruling Case Law 596, sec. 2 0 .... ................................ 12

Smith v. Independent School District, 40 Iowa 518... 19

State ex rel. Weaver v. Board of Trustees of Ohio

State University, 126 Ohio St. 290, 185 N. E. 196... 17

State v. Duffy, 7 Nev. 342, 8 Am. R. 713...................12,19

State v. White, 82 Ind. 278 ............................................ 15

Tape v. Hurley, 66 Cal. 473, 6 P. 129............................ 15

II. S. v. Buntin, 10 Fed. 730 (C. C. Ohio) .................12, 29

Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36, 17 Am. R. 405.......... 12,19, 29

Whitford v. Board of Commissioners, 74 S. E. 1014... 13

Williams v. Bradford, 158 N. C. 36, 73 S. E. 154..... 12

Woolridge v. Board of Education, 157 Pac. 1184..... 19

R aymond A. P earson, Presi-

dent, W. M. H illegeist,

Registrar, and George M.

S hriver, J ohn M. D en n is ,

W illiam P. Cole, H enry

H olzapfel, J ohn E . R aine ,

D r . W. W. S k in n er , M rs.

J ohn L. W h itehurst and

J . M i l t o n P atterson,

Members o f the B oard of

R egents of th e U niver

sity of M aryland ,

vs.

D onald G. M urray, Other

wise D onald Gaines M ur

ray .

In T he

Court of Appeals

Of M aryland .

O ctober T erm , 1935.

G eneral D ocket No. 53.

APPELLEE’S BRIEF.

STATEMENT OF THE NATURE OF THE CASE.

This is an appeal by Raymond A. Pearson, President

of the University of Maryland; W. M. Hillegeist, Regis

trar of the Baltimore Schools of the University, and

George M. Shriver et al., constituting the Board of

Regents of the University, from an order of the Balti

more City Court entered the 25th day of June, 1935,

granting a Writ of Mandamus, and ordering the above

named appellants to admit Donald G. Murray, appellee,

as a first year student in the Day School of the School of

2

Law of the University of Maryland for the academic year

beginning September 25, 1935, upon his paying the neces

sary fee charged first year students in the Day School

of the School of Law of the University of Maryland, and

completing his registration in the manner required of

qualified and accepted students in the first year class of

the Day School of the School of Law of the University of

Maryland, to wit, that he be not excluded on the ground

of race or color (B. 41-42).

The trial Court rendered no formal opinion.

QUESTIONS FOR DECISION.

Question No. 1.

Whether the refusal of the appellants to admit appel

lee, a qualified student, to the first year class of the day

school of the School of Law of the University of Mary

land solely on account of his race or color was in violation

of the Constitution and laws of the State of Maryland.

The trial court held that appellants had violated the

Constitution and laws of the State of Maryland in refus

ing to admit appellee to the School of Law of the Uni

versity of Maryland solely on account of his race or

color.

Appellee contends that there is no statutory authority

for excluding him from the School of Law of the Univer

sity of Maryland solely on account of his race or color;

that in the absence of statutory authority the attempted

administrative regulation by the executive officers and

agents of the University of Maryland and by the Board

of Eegents excluding appellee from the School of Law

of the University of Maryland solely on account of his

3

race or color is void; and that appellants having conceded

of record that appellee was qualified from an educational

standpoint to be admitted into the Day School of the

School of Law of the University of Maryland (R. 44),

and basing their refusal to admit him solely on account of

his race or color (R. 18-22), the trial court was correct

in issuing the writ of mandamus herein.

Question No. 2.

Whether appellants’ attempt to exclude appellee, a.

qualified student, from the day school of the School of

Law of the University of Maryland solely on account of

race or color was a denial to him of the equal protection

of the laws within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

The trial court held that appellants could not exclude

appellee from the School of Law of the University of

Maryland solely on account of his race or color.

Appellee contends that the acts of the executive officers

and agents of the University of Maryland, and the Board

of Regents, in attempting to exclude appellee, a qualified

student, from the School of Law of the University of

Maryland was state action within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States; that the State of Maryland having established a

state university supported in part from public funds and

under public control, appellee, if otherwise qualified,

could not be excluded therefrom solely on account of his

race or color; that the State of Maryland has provided

appellee no equivalent in opportunities for legal educa

tion equal to the opportunities and advantages offered

him in the School of Law of the University of Maryland;

4

and that the attempt by appellants to exclude him from

the School of Law of the University of Maryland solely

on account of his race or color in the absence of equal

opportunities and advantages in legal education other

wise furnished him by the State of Maryland is a denial

to him of the equal protection of the laws within the

meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States.

STATEMENT OF FACTS.

Appellee, Donald G-. Murray, a Negro citizen of the

State of Maryland and a resident of the City of Balti

more, on January 24, 1935, made application in due form

for admission as a first year student in the Day School

of the School of Law of the University of Maryland (B.

6, 18). His application was rejected by the appellant

President of the University and the appellant Begistrar

solely on account of his race (B. 30-32). He appealed

from this ruling to the appellants, the Board of Begents

of the University (B. 32-33), who ratified the rejection

(B. 60-61).

Murray is a graduate of Amherst College with the

degree of Bachelor of Arts conferred upon him in 1934

after successful completion of a four-year residence

course (B. 6). Appellants stipulated that he was educa

tionally qualified to enter the Day School of the School

of Law of the University of Maryland (B. 44).

The University of Maryland is an administrative de

partment of the State of Maryland, performing an essen

tial governmental function and supported in part out of

funds derived from taxes collected from the citizens of

the State (B. 4, 17). The powers of governing the Uni

5

versity are by law vested in the Board of Regents; the

President and Registrar of the University act as agents

of the Board. The charter of the University provides

that it shall be maintained “ upon the most liberal plan,

for the benefit of students of every country and every

foreign denomination” (R. 4).

Under its charter the University conducts in the City

of Baltimore a School of Law as an integral component

part of the University. The School operates in two divi

sions: a day school and an evening school, having the

same entrance requirements, to wit, the completion of at

least one-half of the work acceptable for a Bachelor’s de

gree granted on the basis of a four-year period of study

by the University of Maryland or a principal college or

university in the State (R. 5). The School of Law of the

University of Marlyand is the only State institution

which affords a legal education to Maryland citizens, and

is the only law school in Maryland approved by the Amer

ican Bar Association and a member of the Association of

American Law Schools (R. 5, 18, 54).

All racial groups except Negroes, if otherwise quali

fied, are admitted to the University. Resident Negro

citizens are excluded; non-resident whites, Filipinos, In

dians, Mexicans, Chinese, et al., are admitted (R. 54-59).

When Murray applied for admission to the School of

Law he was advised that the University of Maryland

did not accept Negro students except at Princess Anne

Academy, the so-called Eastern Branch of the University

of Maryland (R. 30-32). No instruction in law is offered

at Princess Anne Academy (R. 47). Murray was further

referred to Chapter 34 of the Acts of 1933 which pur

6

ported to create scholarships for Negro students who de

sired to take professional courses or other work not

given at Princess Anne Academy (R. 21, 31). No money

was ever appropriated or allocated for scholarships under

said Act of 1933, nor was any scholarship under it ever

awarded (R. 62-65).

Ten thousand dollars were appropriated for Negro

scholarships under Chapter 577 of the Acts of 1935, ap

proved April 29, 1935 (R. 20, 109). The administration

of the Act was placed in the hands of a specially created

Maryland Commission on Higher Education of Negroes.

The administrative interpretation of the Act was that

the scholarships provided covered tuition only (R. 112);

and there were so many applications for scholarships

that the Commission was not in position to satisfy all

qualified applicants (R. 110-111).

Murray does not want an out-of-state scholarship (R.

48). He desires to attend the School of Law of the Uni

versity of Maryland in Baltimore where he is at home

and room and board cost him nothing (R. 45, 50). The

nearest out-of-state law school with a general standing

comparable to that of the School of Law of the University

of Maryland, which he could attend, is the Howard Uni

versity School of Law in Washington, D. C. To attend

this School Murray would be put to the expense of com

muting daily from Baltimore to Washington and return,

with attendant loss of time; or of paying for room and

board in Washington (R. 49-50).

Murray further desires to attend the School of Law

of the University of Maryland for profesisonal advant

ages. He is preparing himself to practice law in Balti

more, and attending law school in Baltimore would give

7

him the opportunity to observe the Maryland courts and

to become acquainted with other Maryland practitioners

(R. 45). Ninety-five per cent, of the enrollment in the

School of Law of the University of Maryland comes from

the State of Maryland (R. 84), and the School of Law

lays emphasis on Maryland law (R. 85). A majority of

its faculty is made up of judges and practicing attorneys

of Maryland (R. 85).

Finally Murray desires to attend the School of Law of

the University of Maryland in exercise of his rights as a

citizen to share equally the advantages offered by a pub

lic tax supported state university (R. 45).

Murray renewed the tender of his application and ex

amination fee in open Court (R. 87), and submitted him

self to be fully able to meet all legitimate demands of

the School of Law of the University of Maryland (R. 46).

The tender was refused (R. 87).

ARGUMENT.

I.

THE REFUSAL OF THE APPELLANTS TO ADMIT APPEL

LEE, A QUALIFIED STUDENT, TO THE FIRST YEAR CLASS OF

THE DAY SCHOOL OF THE SCHOOL OF LAW OF THE UNIVER

SITY OF MARYLAND SOLELY ON ACCOUNT OF HIS RACE OR

COLOR WAS IN VIOLATION OF THE CONSTITUTION AND

LAWS OF THE STATE OF MARYLAND.

There is no statutory authority for excluding appellee

from the School of Law of the University of Maryland

solely on account of his race or color.

The declaration of Rights of the State of Maryland,

Article 43, charges the legislature with the duty of en

8

couraging “ the diffusion of knowledge and virtue, the

extension of a judicious system of general education, the

promotion of literature, the arts, sciences, agriculture,

commerce and manufactures, and the general ameliora

tion of the condition of the people.” The State Consti

tution, Article VIII, Section 1, provides:

“ The General Assembly, at its first session after

the adoption of this Constitution, shall, by law, estab

lish throughout the State a thorough and efficient

system of free public schools; and shall provide by

taxation or otherwise, for their maintenance.”

Nothing in the Declaration of Rights or in the State Con

stitution requires or authorizes the separation of white

and Negro students.

In execution of its trust the General Assembly set up

a system of free public schools for the youth of the State,

and has from time to time extended the system of free

public education from the elementary, to the high school,

to the normal school level.

See Bagby, Annotated Code of Maryland, Ar

ticle 77.

Separate, but patently unequal, provisions are made in

the public school laws for colored elementary, industrial,

high and normal schools; the salaries of the colored

teachers therein, and the administrative officers thereof.

For example, see:

Code, Art. 77, Chap. 3A, sec. 35 (4 ); Chap. 18;

Chap. 19, Sec. 204; Chap. 20, Secs. 211-

214.

9

No collegiate education for either white or Negro stu

dents was provided as a part of the system of free pub

lic schools. Down to the year 1935 the collegiate and pro

fessional education which the State of Maryland offered

to its citizens was provided by it at the University of

Maryland, and through certain free scholarships to in

stitutions within the State of Maryland attended exclu

sively by white students.

See Code, Art. 77, secs. 240-257;

See Acts of 1912, Chap. 90, scholarships at

The Johns Hopkins University.

By chapter 234, Acts of 1933 (Code, Art. 77, sec. 214A)

the Legislature attempted to establish certain out-of-

state “ partial scholarships” for Negro students as fol

lows :

“ * * * The Board of Regents of the University of

Maryland may allocate such part of the state appro

priation for Princess Anne Academy or other funds

of the Academy as may be by it deemed advisable, to

establish partial scholarships at Morgan College or

at institutions outside of the State of Maryland, for

Negro students who may apply for such privileges,

and who may, by adequate tests, be proved worthy

to take professional courses or such other work as

is not offered in the said Princess Anne Academy,

but which is offered for white students in the Uni

versity of Maryland; and the Board of Regents of

the University of Maryland shall have authority to

name a Board which shall prepare and conduct such

tests as it may deem necessary and advisable in or

der to determine which applicants for scholarships

may be worthy of such awards.”

The record shows (R. 34-36, 62-65) that no money was

ever appropriated or allocated for these “ partial schol

arships ’ ’ under the Act of 1933, nor was any scholarship

under it ever awarded.

10

The first State appropriation for collegiate and pro

fessional scholarships for Maryland Negro students was

$10,000 provided by Chap. 577 of the Acts of 1935. This

Act created a special Maryland Commission on Higher

Education of Negroes, and assigned it the duty of admin

istering the said $10,000 “ for scholarships to Negroes

to attend college outside the State of Maryland, it be

ing the main purpose of these scholarships to give the

benefit of such college, medical, law, or other profes

sional courses to the colored youth of the state who do

not have facilities in the state for such courses, but the

said commission may in its judgment award any of said

scholarships to Morgan College. Each of said scholar

ships shall be of the value of not over Two Hundred Dol

lars ($200) * * (Italics ours.)

There is nothing in the charter of the University of

Maryland and the acts amendatory thereto, as con

firmed and adopted by Chapter 480, Acts of 1920, (Code,

Art. 77, sec. 240) restricting admission to the University

of Maryland to white students only.

The College of Medicine of Maryland, which was the

nucleus of the present University of Maryland, was in

corporated by Chapter 53, Acts of 1807. It was therein

provided that the College be established “ upon the fol

lowing fundamental principles, to wit: The said college

shall be founded and maintained forever upon a most

liberal plan, for the benefit of students of every country

and every religious denomination, who shall freely be

admitted to equal privileges and advantages of educa

tion, and to all the honors of the college, according to

their merit, without requiring or enforcing any religious

or civil test * *

11

In 1812 (Chap. 159, Acts of 1812) the legislature

authorized the College of Medicine “ to constitute,

appoint and annex to itself, the other three colleges

or faculties, viz., The Faculty of Divinity, the Fac

ulty of Law, and the Faculty of the Arts and Sciences;

and that the four faculties or colleges, thus united, shall

be and they are hereby constituted an University, by the

name and under the title of the University of Maryland.”

The charter provided (Sec. 2, Chap. 159 supra) :

“ That the said University shall be founded and

maintained upon the most liberal plan, for the bene

fit of students of every country and every foreign

denomination, who shall be freely admitted to equal

privileges and advantages of education, and to all

the honors of the University, according to their

merit, without requiring or enforcing any religious

or civil test, upon any particular plan of religious

worship or service * * # ’ ’

This statement of basic policy has never been modified

or limited in any way. Negro students were actually ad

mitted into the School of Law of the University of Mary

land in the 1890’s, and two graduated therefrom. (E. 86)

Until 1920 the University was a private institution

within the meaning of the decision in Clark vs. Mary

land Institute, 87 Md. 643 (1898). In 1920 by Chap. 480

supra the legislature took over the University of Mary

land as a state institution, adopted and confirmed the

former charters (R. 4, 17). The Act of 1920 gave the

State of Maryland one state university offering colle

giate and professional education. The Act makes no

distinction between the races and there is no expression

in it which could be interpreted as applying to the white

race only. In the absence of equal facilities for colie-

12

giate and professional education for qualified Negro cit

izens otherwise, the Act if interpreted to benefit white

students only would be unconstitutional.

“ * * * But the denial to children whose parents,

as well as themselves, are citizens of the United

States and of this State, admittance to the common

schools solely because of color or racial difference

without having made provision for their education

equal in all respects to that afforded persons of any

other race or color, is a violation of the provisions

of the fourteenth amendment of the Constitution of

the United States * * *” Piper v. Big Pine Schools

District 193 Cal. 664 (1924) at p. 668-669.

See also:

Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36, 17 Am. R. 405

(1874);

State v. Duffy, 7 Nev. 342, 8 Am. R. 713

(1872);

U. S. v. Buntin, 10 Fed. 730 (C. C. Ohio)

(1882);

Corey v. Carter, 48 Ind. 327 (1874);

Williams v. Bradford, 158 N. C. 36, 73 S. E.

154 (1911);

5 Ruling Case Law, 596, sec. 20;

11 C. J C i v i l Rights, sec. 10, p. 805;

Cooley on Torts (Perm. Ed.) sec. 236.

There were, and are, no other facilities for Negroes to

study law in the State of Maryland (R. 5, 18), so that

under the well established doctrine that a statute will not

be declared unconstitutional so long as a constitutional

interpretation is reasonably available, the Act of 1920

must be held to open the doors of the University of Mary

land to qualified white and black citizens of Maryland

alike.

“ We are not at liberty to declare a legislative act

void, as being unconstitutional, unless it is clearly

so, beyond any reasonable doubt. There is always

a strong presumption in force of the validity of leg

islation, which must be overcome by some convinc

ing reason to induce a court to declare it void. The

act under consideration makes no distinction be

tween the races and there is no expression in it

which leads us to think that the school was intended

for the exclusive benefit of one race or the other

* * * ” Whitford v. Board of Commissioners, 159

N. C. 160, 74 S. E. 1014 (1912) at p-1015.

The sole question remaining under this sub-heading

is whether any subsequent statute has legally modified

the effect of the Act of 1920 so as to exclude Negroes

from the School of Law of the University of Maryland.

This depends upon the interpretation of the two so-

called out-of-state scholarship acts of 1933 and 1935,

supra.

There is no express provision in either act condition

ing the scholarships upon a forfeit of the Negro stu

dent’s right to attend the University of Maryland, any

more than there is a condition of forfeiture upon the

“ Free Scholarships’ ’ established through state appro

priation at St. Mary’s Female Seminary, St. John’s Col

lege, Western Maryland College, Maryland Institute,

Washington College, Charlotte Hall School, The Johns

Hopkins University, etc.

See Code, Art. 77, secs. 241 et seq.; Acts of

1912, Chapter 90.

14

White students have the option of attending the Uni

versity of Maryland or applying for “ free scholarships”

covering the same courses at the institutions mentioned;

and in the case of The Johns Hopkins University “ free

scholarships” , for courses not offered in the Univer

sity of Maryland. The language of the act of 1933 is dis

tinctly permissive only: “ partial scholarships * * * for

Negro students who may apply for such privileges” .

Nothing in the 1933 Act says that Negro students who

do not desire to apply for such privileges cannot attend

the University of Maryland. The 1935 act is a limited

enabling act good for two years only, creating scholar

ships outside the State without reference to the limita

tion of parallel courses at the University of Maryland.

It is impossible to read into these acts of 1933 and 1935

any forfeiture of the rights of qualified Negro citizens

of Maryland to attend the state University of Maryland

without striking down the whole structure of public col

legiate and professional education in the State of Mary

land as unconstitutional because therein Negroes are

denied the equal protection of the laws.

There is no statutory authority express or implied

which excludes Negroes from the University of Mary

land.

B. In the absence of statutory authority the at

tempted administrative regulation by the executive offi

cers and agents of the University of Maryland and by the

Board of Regents excluding appellee from the School of

Law of the University of Maryland solely on account of

his race or color is void.

The right of admission to a state university is a right

which the trustees or other officers are not authorized to

15

abridge materially, and which they cannot as an abstract

proposition rightfully deny.

Foltz v. Hoge, 54 Cal. 28 (1879);

State v. White, 82 Ind. 278 (1912);

Cornell v. Gray, 33 Okla. 591 (1912).

It has been uniformly held that in the absence of express

authority by statute, a municipality, school district or

board has no authority even to separate white and col

ored children for educational purposes.

“ * * * It must be remembered that unless some

statute can be found authorizing the establishment

of separate schools for colored children that no such

authority exists; * * * ” Board of Education v.

Tinnon, 26 Kan. 1, 39 L. R. A. 1020 (1881).

Crawford v. District School Board, 68 Or. 388,

137 Pac. 217 (1913).

The administrative authority, in the absence of power

delegated by statute, cannot exclude Negro students from

schools established for white students, even though the

educational facilities in the segregated Negro school are

equal or superior to those of the white school.

People ex rel. Bibb v. Mayor, 193 111. 309, 61

N. E. 1077, 56 L. R. A. 95 (1901).

All youth stands equal before the law,

Clark v. Board, 24 Iowa 266, 277 (1868).

The question as to what the legislature might have

done is beside the point; the administrative authority

cannot arrogate to itself the legislative functions.

Tape v. Hurley, 66 Cal. 473, 6 P. 129 (1885).

16

It is noteworthy herein that appellants themselves do

not claim any statuory authority for excluding appellee

from the School of Law of the University of Maryland

solely on account of his race or color. The only authority

they rely on is a resolution of the Board of Regents April

22, 1935, recorded in the minutes of the Board and set

out in the Record pp. 60-61.

While the Board of Regents of the University of Mary

land has large and discretionary powers in regard to the

management and control of the University, it has no

power to make class distinctions or racial discrimination.

See Chase v. Stephenson, 71 111. 383, 385

(1874).

The reason is obvious. A discrimination by the Board

of Regents against Negroes today may well spread to a

discrimination against Jews on the morrow; Catholics

on the day following; red headed men the day after that.

“ # * * it is obvious that a board of directors

can have no discretionary power to single out a part

of the children by the arbitrary standard of color,

and deprive them of the benefits of the school privi

lege. To hold otherwise would be to set the discre

tion of the directors above the law. If they may

lawfully say to the one race you shall not have the

privilege which the other enjoys they can abridge the

privileges of either until the substantive right of one

or both is destroyed.” Maddox v. Neal, 45 Ark. 121,

124 (1885).

Most of the cases above cited have dealt with elemen

tary education and neighborhood schools. If a board of

education cannot of its own motion exclude Negro child

ren from a neighborhood school, although more schools

17

are available within the same community, it follows with

greater force that the administrative authority of the

only state university within the territory of the State

cannot, minus legislative authorization, exclude a quali

fied citizen of the State from the only instruction in law

which the State offers to its citizens. Counsel has been

unable to find a case with facts exactly paralleling the

instant case. The most recent case involving an apparent

ly allied problem is State ex rel. Weaver v. Board of

Trustees of Ohio State University, 126 Ohio St. 290, 185

N. E. 196 (1933). In that case, however, no attempt was

made to exclude the Negro student from the University,

nor even from the course. The court took the position

that the University was offering her its full facilities,

exactly the same as it offered to the white students in the

same courses.

Cf. Patterson v. Board of Education, 11 N. J.

Misc. 179 (1933).

As distinguished from the Weaver ease, the administra

tive authority of the University of Maryland, on its own

responsibility, attempted to withhold all the facilities of

the University from appellee solely on account of his race

or color.

The school eases establish clearly that this attempted

exclusion was void.

C. Appellants having conceded of record that appel

lee was qualified from an educational standpoint to he ad

mitted into the Day School of the School of Law of the

University of Maryland, and hasing their refusal to ad

mit him solely on account of his race or color, the trial

court was correct in issuing the ivrit of mandamus.

18

While the State is under no compulsion to establish a

state university, yet if a state university is established

the rights of white and black are measured by the test

of equality in privileges and opportunities. No arbitrary

right to exclude qualified students from the University

of Maryland is claimed by appellants except as to quali

fied Negroes, whom the administrative authority would

reject on the sole ground of race or color. As to all other

racial elements comprising the population of Maryland,

the appellants concede that if the students were other

wise qualified they would be admitted as a matter of

course. (R. 55-59.) White students from foreign states,

if otherwise qualified, would be admitted as a matter of

course. (R. 59.) In other words, assuming that a student

is qualified his admission to the proper course in the Uni

versity of Maryland, provided he is not a Negro, is a

ministerial matter. If he is a qualified Negro, he is re

jected automatically (R. 55-59).

Appellants stipulated of record that appellee was fully

qualified from an educational standpoint to be admitted

into the Day School of the School of Law of the Univer

sity of Maryland (R. 44), to which he had applied for

admission (R. 6, 10). They automatically and arbitrarily

rejected him solely on account of his race or color. (R.

18-22, 30-34, 60-61.) No element of discretion was in

volved.

Under these circumstances the writ of mandamus was

properly issued after full consideration of all the plead

ings, stipulations of record and the evidence taken, to

undo the arbitrary wrong inflicted by the appellants on

the appellee, and to compel them to the proper perform

ance of their ministerial duty to accept and register him

19

in the Day School of the School of Law of the University

of Maryland upon the same terms as any other qualified

applicant.

See

State v. Duffy, 7 Nev. 342 (1872).

Ward v. Flood, supra.

Piper v. Big Pine School District, supra.

Woolridge v. Board of Education, 157 Pac.

1184 (1916).

People ex rel. Bibb v. Mayor etc. City of

Alton, supra,

Lowery v. Board of Trustees, 52 S. E. 267

(1906).

Clark v. Board of Trustees, 24 Iowa 266

(1868).

Smith v. Independent School District, 40 Iowa

518 (1875).

II.

APPELLANTS’ ATTEMPT TO EXCLUDE APPELLEE, A QUALI

FIED STUDENT, FROM THE DAY SCHOOL OF THE SCHOOL OF

LAW OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND SOLELY ON AC

COUNT OF RACE OR COLOR WAS A DENIAL TO HIM OF THE

EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAWS WITHIN THE MEANING

OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION

OF THE UNITED STATES.

A. The acts of the executive officers and agents of the

University of Maryland, and of the Board of Regents, in

attempting to exclude appellee, a qualified student, from

the School of Law of the University of Maryland was

state action within the meaning of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

20

It being conceded of record that the University of

Maryland is an administrative department of the State

of Maryland, and a State institution performing an es

sential governmental function; that the funds for its sup

port and maintenance in part are derived from the gen

eral Treasury of the State out of funds procured by taxes

collected from the citizens of Maryland; that the appro

priations for it are made by the Legislature as a part of

the public school system; that the governing body of the

University is the Board of Regents, who are appointed

by the Governor, by and with the consent of the Senate;

and that the appellant President of the University and

the appellant Registrar function as agents of the Board

of Regents under their supervision and control (R. 4, 17-

18)—it follows that the action of the President, the Reg

istrar and the Board of Regents in attempting to exclude

appellee from the School of Law of the University of

Maryland solely on account of his race or color was state

action within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States.

“ Whoever, by virtue of public position under a

State government, deprives another of property,

life, or liberty, without due process of law, or denies

or takes away the equal protection of the laws, vio

lates the constitutional inhibition; and as he acts in

the name and for the State, and is clothed with the

State’s power, his act is that of the State. This must

be so, or the constitutional prohibition has no mean

ing. Then the State has clothed one of its agents with

power to annul or to evade it.” Ex parte Virginia,

100 U. S. 339, 346 (1879).

B. The State of Maryland having established a state

university supported in part from public funds and

under public control, appellee, if otherwise qualified,

21

could not be excluded therefrom solely on account of his

race or color.

The general proposition that a state cannot establish a

single state university and exclude Negro citizens solely

on account of race or color has already been argued supra

under Section I-A. At the trial appellants did not serious

ly challenge this general proposition, but maintained that

the State had provided appellee with equal facilities for

the study of law otherwise than in the School of Law of

the University of Maryland. The argument which fol

lows will demonstrate that no such equal facilities have

been afforded appellee.

C. That the State of Maryland has provided appellee

no equivalent in opportunities for legal education equal

to the opportunities and advantages offered him in the

School of Law of the University of Maryland.

The question whether the State of Maryland has

offered appellee any opportunities and facilities for the

study of law otherwise than in the School of Law of the

University of Maryland depends upon the two so-called

scholarship acts of 1933 and 1935 supra.

The administration of the scholarship act of 1933 was

committed to appellants, the Board of Regents. The rec

ord discloses that the interpretation of the act was that

the Board of Regents was to give the Negro student the

difference between the cost of his tuition in the foreign

school and the cost of tuition for the same course in the

University of Maryland. If the tuition in the foreign

school happened to be lower than the tuition for the same

course in the University of Maryland, the Negro student

22

was to receive nothing. (R. 71.) Appellant Pearson, Pres

ident of the University of Maryland, in rejecting appel

lee’s application solely on account of race or color re

ferred him to the scholarship act of 1933 and suggested

that he register in the Howard University School of Law.

(R. 33-34.) On the witness stand appellant Pearson was

forced to admit that if appellee had registered in How

ard University School of Law, he would not have in

tended to give appellee a single cent under the scholar

ship act of 1933 (R. 71).

Appellee is reluctantly forced to charge the appellants

with evasion throughout. The attitude of the Board

of Regents of the University of Maryland toward

Negro education in the State is illustrated in its at

tempt to avoid giving Princess Anne Academy its

fair share of the money due it under the Federal

Morrill Act. The Morrill Act of 1862 provided for Fed

eral grants in aid of State land grant colleges. It was

amended by Act of August 30, 1890, to prohibit expressly

discrimination on account of race; but it was therein pro

vided that if a State maintained separate educational in

stitutions of like character for white and colored, and a

just and equitable division of the fund received be divided

by the State between the two institutions such division

should be deemed a compliance with the Act. The State

of Maryland regularly received Federal donations under

the Morrill Act, and down to 1933 applied the same for

the benefit of white students only. In 1933 the General

Assembly provided (Acts of 1933, Chap. 34; Code, Art.

77, Sec. 214A supra) that the donations received under

the Morrill Act, which amounted to $50,000 per year,

should be “ divided on the basis of the population of the

State of Maryland as shown by the latest census, so that

23

a percentum of these funds equal to the percentum of the

Negro population to the whole population of the State,

shall be expended by the Comptroller of the State, upon

recommendation of the Regents of the University of

Maryland, for the benefit and in the interests of the Prin

cess Anne Academy.” (Italics ours.) The Census of 1930

established that Negroes constituted approximately 17%

of the total population of Maryland, which would make

the sum to be expended for the benefit of Princess Anne

Academy under the Act approximately $8,500.00.

The minutes of the Board of Regents show that less

than a year previously, to wit on September 9, 1932, (R.

61) the Board of Regents had attempted to avoid using

any of the proceeds of the Morrill Act donations for

Negro education by withdrawing $600.00 from the miser

ably small existing budget of Princess Anne Academy

to create some Junior and Senior College scholarships:

“ The Committee on Princess Anne recommends

that authority be given for the use of not to exceed

$600, payable from available funds in the Princess

Anne budget, as scholarships for students who have

completed the Freshman and Sophomore college

work now offered at Princess Anne and who desire

to take Junior and Senior years of college work. In

view of the fact that Junior and Senior work is not

given at Princess Anne it will be necessary for the

higher work in agriculture to be obtained in some

other state. These scholarships would be used to

assist such students.

‘ ‘ These scholarships would represent a smaller ex

penditure of State funds than would be required to

provide the additional education facilities at Prin

cess Anne. A precedent for such scholarships had

been provided by other states and the scholarships

are recommended by the Federal Office of Education.

24

The institution of a few of these Scholarships would

make it impossible for anyone to claim that Negroes

are not given a fair opportunity in Maryland under

the terms of the Land Grant legislation * * * ” (R. 61,

italics ours).

A specious gesture on the part of the Board of Regents

to delude the Negro population of Maryland and keep it

quiet.

It is to be noted that the Board of Regents ratified in

full the duplicity of the appellant President in dealing

with the appellee; and that this ratification coming April

22, 1935 (R. 60) antedated the scholarship act of 1935,

which was approved April 29, 1935. At that time the

Board of Regents, agents of the State of Maryland, did

not even have the semblance of an equivalent to offer ap

pellee in exchange for excluding him from the School of

Law of the University of Maryland solely on account of

his race or color; but they affirmed the conduct of the

President of the University in concealing that fact from

him.

The dual and inferior standard which appellants apply

to Negro education is evidenced by the pitiful attempt of

the President of the University on the witness stand to

assert that just as good a course was offered at Princess

Anne as at College Park. (R. 51-53, 67-69, 72-76).

Not only on the part of the Board of Regents but in

the official policy of the State as expressed in its school

laws (See Code, Art. 77, supra), it is notorious that no

real attempt is made to provide true equality between

white and Negro public education in Maryland in a single

particular: length of school term, teacher’s salaries, bus

25

transportation, high school facilities, per capita cost of

education per pupil, or otherwise. The scholarship act

of 1935 (Acts of 1935, Chap. 577) is no exception.

This scholarship act of 1935 is a special experimental

limited act providing $10,000 for the total of scholarships

for Negro collegiate, graduate and professional educa

tion. The act was interpreted to provide scholarships for

tuition only. (R. 112.)

No provision is made for the differential in mainte

nance between what it would cost the Negro student to

maintain himself at the University of Maryland and what

it would cost him to maintain himself at the foreign

school. No differential in cost of travel is provided. The

Negro student would have to bear the cost of mainte

nance and travel himself.

Appellee does not concede that it is constitutional for

a State to exile one set of its citizens beyond its borders

to obtain the same education which it is offering to citi

zens of different color at home. It is not without signifi

cance that all the “ free scholarships” which the State

provides for its white citizens are in Maryland colleges

and universities. Only its Negro citizens are exiled.

But granting for the sake of argument, that the Act is

not void for constitutional reasons regardless of its

money provisions, it still does not furnish appellee the

equivalent of a course in law at the School of Law of the

University of Maryland.

1. Even though his tuition charges of $135.00 in the

Howard University School of Law would be paid by the

State of Maryland, and he himself would have to pay

26

$203.00 to attend the Day School of the School of Law

of the University of Maryland (R. 33-34), appellee

would still be the loser to attend the Howard University

School of Law.

a. If he commuted from his home in Baltimore to

Washington and return each school day, commutation

would cost him approximately $15.00 per month for 9

months; he would have to buy at least one meal per

school day in Washington; he would lose four hours per

school day on the road from home to school and back

again, or approximately 840 hours during the school

year which he might otherwise use in relaxed, uninter

rupted work on his courses. Then there would be the

physical energy expended in the travel back and forth

catching early and late trains.

b. If he lived in Washington he would have to pay for

separate room and board, whereas attending the School

of Law of the University of Maryland he could live at

home with no maintenance expense. (R. 50.) The question

whether he can be forced into exile has already been

noted.

2. Since appellee desires to practice law in Baltimore,

the $135.00 scholarship would be no equivalent for loss

of the opportunity to observe the courts in Baltimore

during his law school career which would be possible if

he attended the School of Law of the University of Mary

land ; no equivalent for the familiarity and drill he would

get in Maryland law through the special emphasis laid

on it in the instruction given in the School of Law of the

University of Maryland; no equivalent for the oppor

tunity he would have to become acquainted with, to ap

27

praise the strength and weaknesses of the Judges and

practitioners of Maryland whom he would have to deal

with later in his practice. It must be remembered that the

law is a competitive profession, and this matter of equiv

alent must be judged in part on the basis of the handicap

which appellee would have coming from a foreign law

school in competitive practice with graduates of the

School of Law of the University of Maryland.

3. The $135.00 scholarship is but a tempting mess of

pottage held out to induce him to sell his citizenship

rights to the same treatment which other citizens of

Maryland receive, no more and no less. Equivalents must

also be considered in terms of self-respect. Appellee is a

citizen ready to pay the same rate of taxes as any other

citizen, and to go as far as any other citizen in discharge

of the duties of citizenship to state and nation. He does

not want the scholarship or any other special treatment.

4. The School of Law of the University of Maryland

is firmly established in the life of the State. Founded in

1813, the School of Law has been providing legal educa

tion to the citizens of Maryland without interruption

since 1870. The scholarship act of 1935 is frankly a tem

porary experiment with only two years of life guaranteed

it. The shortest day law course in a recognized law school

is three years. The scholarship act by the wildest stretch

of the imagination cannot be considered the equivalent

of the School of Law of the University of Maryland.

It is plain that the State of Maryland has not offered

appellee the equivalent of the opportunities and advan

tages which he would have in studying law in the School

of Law of the University of Maryland.

28

D. The attempt by appellants to exclude appellee

from the School of Law of the University of Maryland

solely on account of his race or color, in the absence of

equal opportunities and advantages in legal education

otherwise furnished him by the State of Maryland, was a

denial to him of the equal protection of the laws within

the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

The argument on this point has already been antici

pated throughout the brief.

It is the further contention of the appellee that even if

this Court should find that the General Assembly in

tended to exclude Negroes from the University of Mary

land by the so-called scholarship acts of 1933 and/or

1935, nevertheless since said acts furnished Negroes no

true equality they are unconstitutional and cannot be the

legal predicate of an exclusion of Negroes from the Uni

versity.

“ Had the petition alleged specifically that there

was no colored school in Martha Lum’s neighbor

hood to which she could conveniently go, a different

question would have been presented, and this, with

out regard to the State Supreme Court’s construc

tion of the State Constitution as limiting the white

schools provided for the education of children of the

white or Caucasian race.” Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.

S. 78, 84 (1927).

In the principal case appellee has maintained from the

beginning that the only law school in Maryland which he

could attend is the School of Law of the state University

of Maryland, and that the State has offered him no equiv

alent substitute therefor. Appellants’ attempt to exclude

29

him from the School of Law under the circumstances,

solely on account of his race or color, is a denial to him of

the equal protection of the laws within the meaning of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36 (1874).

Piper v. Bin Pine School District, 193 Cal. 664

(1924).

United States v. Buntin, 10 Fed. 730 (1882).

People, ex rel. Bibb, v. Alton, 193 111. 309

(1901).

It remains to notice some of the argument advanced

by the appellants at the trial in their attempt to defeat

the application for the writ.

1. Appellants contended that there was no demand

on the part of Maryland Negroes for collegiate and pro

fessional education (E. 21). The record however shows

that the number of applications for scholarships under

the Act of 1935 was so great that there would not be schol

arship money enough to satisfy all qualified applications.

(E. 110-111). 626 Negroes are registered in Morgan Col

lege in Baltimore. (E. 67). Further it does not sound

well for the agents of the State to complain that there is

no great demand on the part of Negroes for collegiate

and professional education, when the State itself has

made it difficult for Maryland Negroes to qualify for col

legiate and professional education because of the inferior

elementary schools which the State and counties maintain

and the absence of adequate high school facilities for

Negroes. Finally appellee is an individual. His years

and days are numbered, and he cannot wait for his educa

tion until there is a mass demand to the satisfaction of

30

the appellants. A citizen’s constitutional rights receive

protection on an individual basis.

“ This argument with respect to volume of traffic

seems to us to be without merit. It makes the Consti

tutional right depend upon the number of persons

who may be discriminated against, .whereas the es

sence of the constitutional right is a personal one.”

McCabe v. Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Rv. Co., 235

IT. S. 151, 160 (1914).

2. Appellants contended that public sentiment de

manded the exclusion of appellee from the School of Law

of the University of Maryland (R. 66), and dire predic

tions were made that there would be disorders, loss of

enrollment and general friction if appellee were admitted

to the School of Law. It is a notorious fact of public com

ment and general note in the public press of which this

Court can take judicial notice and which appellants will

not deny, that the School of Law opened for its Fall term

September 25, 1935, that appellee registered and was ad

mitted as a student, and there has been no disorder, no

friction, no loss of enrollment, but on the contrary a sub

stantial increase in enrollment both in the School of Law

and in the total enrollment in the University.

Maryland has come a long way from the days of Clark

v. Maryland Institute, 87 Md. 643 (1898), where the Su

perior Court of Baltimore City denied mandamus to com

pel the Maryland Institute to enroll a Negro student.

This Court affirmed on the ground that the Maryland In

stitute was a private institution, but went on in its opin

ion to note:

“ * * # The effect of the admission of these four

pupils was very disastrous. There was an immovable

31

and deep settled objection on the part of the white

pupils to an association of this kind. Notwithstand

ing earnest and zealous efforts on the part of the

board of managers and the faculty of teachers to

reconcile the white pupils, their parents and guar

dians to the innovation, it caused a great decrease in

the number of pupils; and the bringing of this suit

made it still greater” (p. 656).

It is the height of absurdity to say that appellee Mur

ray cannot sit in the same room and recite and study with

out friction with the same men, who within the next few

years will have to sit side by side with him within the bar

of the Court and at the counsel table.

The question was asked the President of the Univer

sity on the witness stand “ just what harm, in your opin

ion, would arise from the fact that a Negro boy might

want to occupy a seat at the law school of the University

of Maryland, the same as any other student, minding his

own business.” The President replied: “ I did not go into

that question. I felt I knew the well-established policy in

this State, the District of Columbia, and different States,

and personally, I was influenced by that policy. ’ ’ He was

asked whether the question had ever been submitted to

the students of the School as to the admission of Negro

students. He replied he did not know (B. 66). The stu

dents of the School of Law, however, have themselves

given the answer by the absence of friction due to Mur

ray’s presence in the School and no loss in enrollment

altho the order admitting him was entered and made

public property June 25, 1935, three months prior to the

opening of the autumn term.

Appellee does not concede that if public sentiment were

hostile this Court would be entitled to uphold his exclu

32

sion from the School of Law of the University on that

ground in the absence of statute.

Clark v. Board of Directors, 24 Iowa, 266

(1868).

If the constitutional right exists, the test of sovereign

ty in a government is its ability to enforce and protect

the same even in the face of a temporary manifestation

of hostile public sentiment. But appellee is gratified that

he can report in this case that there has been in the School

no manifestation of a hostile public sentiment, and no

evidence of harm done the institution or any of its mem

bers.

CONCLUSION.

For the aforegoing reasons it is respectfully submitted

that the decision of the trial court be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

CHARLES H. HOUSTON,

WILLIAM I. GOSNELL,

Attorneys for Appellee.