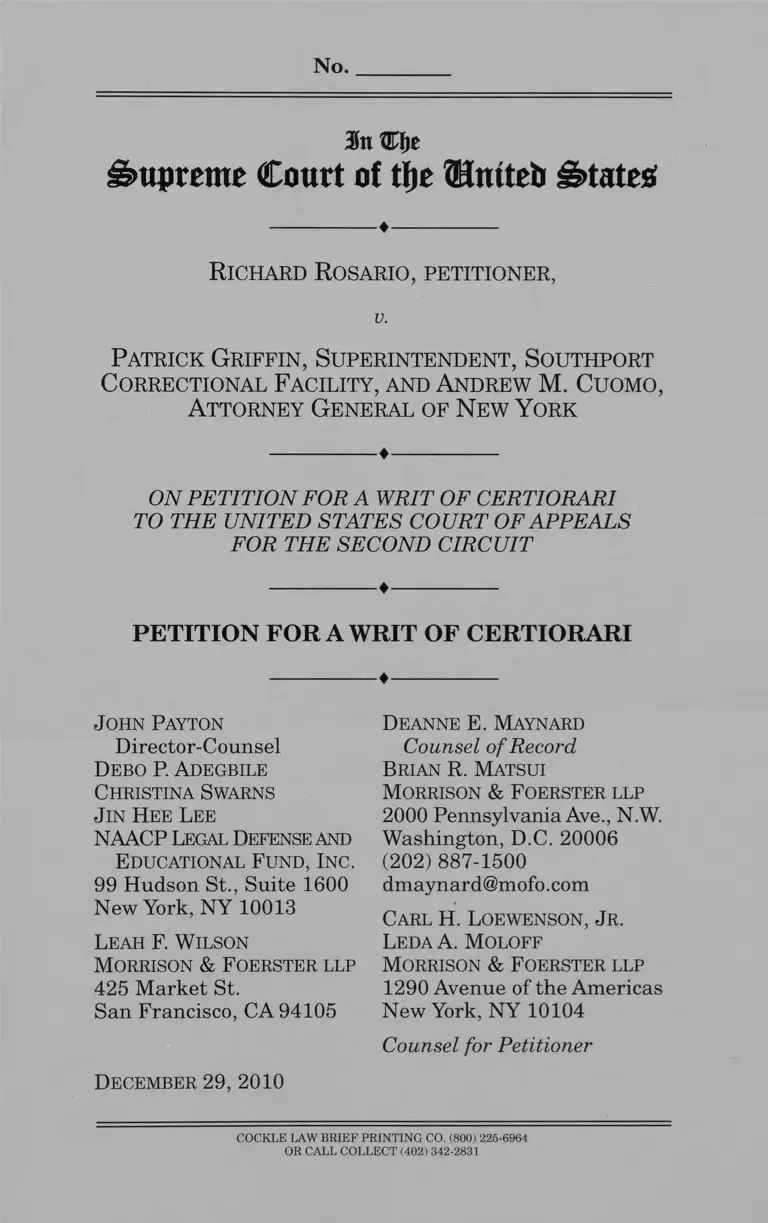

Rosario v Griffin Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

December 29, 2010

302 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rosario v Griffin Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 2010. a56cf242-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a72bfdd1-9f7d-4c87-89a9-3c4cfc2cba98/rosario-v-griffin-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No.

3fa®f)E

S u p re m e C o u r t of tfje M n tte b S ta te s ;

----------------♦----------------

R ic h a r d R o s a r io , p e t it io n e r ,

V.

P a t r ic k G r if f in , S u p e r in t e n d e n t , S o u t h p o r t

C o r r e c t io n a l F a c il it y , a n d A n d r e w M . C u o m o ,

A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l o f N e w Y o r k

----------------« ----------------

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

-------------- ♦---------------

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

John Payton

Director-Counsel

Debo P. Adegbile

Christina Swarns

Jin Hee Lee

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson St., Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

Leah F. W ilson

M orrison & Foerster llp

425 Market St.

San Francisco, CA 94105

Deanne E. Maynard

Counsel of Record

Brian R. Matsui

M orrison & Foerster llp

2000 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 887-1500

dmaynard@mofo.com

Carl H. Loewenson, Jr.

Leda A. Moloff

Morrison & Foerster llp

1290 Avenue o f the Americas

New York, NY 10104

Counsel for Petitioner

December 29, 2010

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

mailto:dmaynard@mofo.com

QUESTION PRESENTED

In Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984),

this Court set forth a two-part test for demonstrating

ineffective assistance of counsel under the Sixth

Amendment. First, a prisoner must demonstrate that

his “counsel’s performance was deficient.” Second, the

prisoner must show that “there is a reasonable prob

ability that, but for counsel’s unprofessional errors,

the result of the proceedings would have been different.”

By contrast, New York’s state constitutional standard

for ineffective assistance of counsel is limited to a

single inquiry: whether “the evidence, the law, and

the circumstances of a particular case, viewed in

totality and as of the time of the representation,

reveal that the attorney provided meaningful repre

sentation.” People v. Baldi, 429 N.E.2d 400, 405 (N.Y.

1981). This state standard “allows the gravity of

individual errors to be discounted indulgently by a

broader view of counsel’s overall performance.” App.,

infra, 244a (Jacobs, C.J., dissenting to denial of

rehearing en banc). In evaluating petitioner’s federal

constitutional claim of ineffective assistance of counsel,

the state court applied the New York state constitu

tional standard instead of Strickland, and denied

habeas relief.

The question presented is:

Whether application of New York’s state constitu

tional “meaningful representation” standard to eval

uate Sixth Amendment claims of ineffective

assistance of counsel results in decisions that are

contrary to, or involve an unreasonable application of,

clearly established federal law.

11

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

Petitioner is Richard Rosario.

Respondents are Superintendant Patrick Griffin,

Southport Correctional Facility, and New York Attor

ney General Andrew Cuomo.

I l l

QUESTION PRESENTED...................................... i

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING...................... ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS.......................................... iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................................... vi

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI....... 1

OPINIONS BELOW.................................................. 1

JURISDICTION........................................................ 1

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PRO

VISIONS INVOLVED........................................... 2

STATEMENT............................................................. 2

A. Constitutional And Statutory Framework .... 4

B. State Court Proceedings.............................. 7

C. Proceedings Below........................................ 15

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION.... 20

REVIEW IS NECESSARY BECAUSE NEW

YORK’S “MEANINGFUL REPRESENTATION”

STANDARD RESULTS IN DECISIONS THAT

ARE CONTRARY TO, OR AN UNREASON

ABLE APPLICATION OF, STRICKLAND V.

WASHINGTON..................................................... 20

A. The Ruling Below Conflicts With The

Habeas Decisions Of This Court And

Other Courts Of Appeals............................. 21

1. Contrary to clearly established federal

la w ............................................................ 21

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

IV

2. Unreasonable application of clearly

established federal law.......................... 31

B. Continued Application Of New York’s

“Meaningful Representation” Standard

Will Prejudice Habeas Petitioners And

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

Burden Federal Courts................................. 35

CONCLUSION........................................................... 38

APPENDIX A: Opinion of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, dat

ed April 12, 2010........................................................ la

APPENDIX B: Order granting Certificate of

Appealability of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Second Circuit, dated April

15, 2009..................................................................... 59a

APPENDIX C: Memorandum and Order of

the United States District Court for the

Southern District of New York, dated Octo

ber 22, 2008...............................................................60a

APPENDIX D: Report and Recommendation

of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of New York, dated De

cember 28, 2007....................................................... 99a

APPENDIX E: Certificate Denying Leave of

the Supreme Court of the State of New York,

Appellate Division: First Department, dated

September 8, 2005..................................................205a

V

APPENDIX F: Decision and Order of the

Supreme Court of the State of New York,

dated December 28, 2007......................................207a

APPENDIX G: Certificate Denying Leave of

the State of New York Court of Appeals, dat

ed March 26, 2002..................................................232a

APPENDIX H: Remittitur of the Supreme

Court of the State of New York, Appellate

Division: First Department, dated November

27, 2001...................................................................234a

APPENDIX I: Order Denying Rehearing and

Rehearing En Banc of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, dated

August 10, 2010 .....................................................237a

APPENDIX J: United States Code, Title 28,

Section 2254........................................................... 250a

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

VI

Cases

Cargle v. Mullin, 317 F.3d 1196 (10th Cir. 2003)..... 26

Castillo v. Matesanz, 348 F.3d 1 (1st Cir. 2003),

cert, denied, 543 U.S. 822 (2004)............................. 27

Cooper-Smith v. Palmateer, 397 F.3d 1236 (9th

Cir.), cert, denied, 546 U.S. 944 (2005).................. 27

Eze v. Senkowski, 321 F.3d 110 (2d Cir. 2003)...........37

Goodman v. Bertrand, 467 F.3d 1022 (7th Cir.

2006).............................................................................25

Henry v. Poole, 409 F.3d 48 (2d Cir. 2005), cert,

denied, 547 U.S. 1040 (2006).............................37, 38

Hummel v. Rosemeyer, 564 F.3d 290 (3d Cir.),

cert, denied, 130 S. Ct. 784 (2009)...........................26

Kimmelman v. Morrison, A ll U.S. 365 (1986)..............33

Lindstadt v. Keane, 239 F.3d 191 (2d Cir. 2001).........37

Loliscio v. Goord, 263 F.3d 178 (2d Cir. 2001)...........37

Magana v. Hofbauer, 263 F.3d 542 (6th Cir.

2001).............................................................................27

Manson v. Brathwaite, 432 U.S. 98 (1977)................35

Ouber v. Guarino, 293 F.3d 19 (1st Cir. 2002).......... 27

People v. Baldi, 429 N.E.2d 400 (N.Y. 1981).................6

People v. Benevento, 697 N.E.2d 584 (N.Y.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

1998)....................................................................6, 7, 23

V ll

People v. Rosario, 733 N.Y.S.2d 405 (N.Y. App.

Div. 2001), appeal denied, 97 N.Y.2d 760

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

(2002) ...........................................................................................9

People v. Turner, 840 N.E.2d 123 (N.Y 2005)..... 24, 29

Porter v. McCollum, 130 S. Ct. 447 (2009)................ 35

Rose v. Lee, 252 F.3d 676 (4th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 534 U.S. 941 (2001).......................................... 27

Saranchak v. Beard, 616 F.3d 292 (3d Cir

2010)............................................................................ 26

Skipper v. South Carolina, 476 U.S. 1 (1986)...........34

Spears v. Mullin, 343 F.3d 1215 (10th Cir.

2003), cert, denied, 541 U.S. 909 (2004)..........25, 26

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984)....passim

United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967)..............35

Wiggins v. Smith, 539 U.S. 510 (2003)....................... 31

Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362 (2000)............ passim

Young v. Dretke, 56 F.3d 616 (5th Cir. 2004).............26

Young v. Sirmons, 486 F.3d 655 (10th Cir.

2007), cert, denied, 552 U.S. 1203 (2008)...............26

Constitutions and Statutes

U.S. Const, amend. VI...........

28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1)............

.passim

passim

V lll

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act

(AEDPA), Pub. L. No. 104-132, 110 Stat.

1214(1996)................................................................... 4

N.Y. Const., art. 1, § 6..................................................... 6

N.Y. Crim. Proc. Law § 440.10.......................................9

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Richard Rosario respectfully petitions for a writ

of certiorari to review the judgment of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals (App., infra,

la-58a) is reported at 601 F.3d 118. The opinion of

the district court (App., infra, 60a-98a) is reported at

582 F. Supp. 2d 541. The report and recommendation

of the magistrate judge (App., infra, 99a-204a) is

reported at 582 F. Supp. 2d 541.

The order of the court of appeals denying the

petition for rehearing and rehearing en banc (App.,

infra, 237a-249a) is unreported but is available at

2010 U.S. App. LEXIS 16675.

JURISDICTION

The Second Circuit issued its opinion on April 12,

2010. App., infra, la-58a. On August 10, 2010, the

Second Circuit denied the petition for rehearing and

rehearing en banc. App., infra, 237a-249a. On Octo

ber 22, 2010, Justice Ginsburg granted an extension

of time within which to file a petition for a writ of

certiorari to and including December 8, 2010, and, on

November 29, 2010, Justice Ginsburg granted a

further extension to and including December 29,

2010.

This Court’s jurisdiction is invoked under 28

U.S.C. § 1254(1).

2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The relevant constitutional and statutory provi

sions are set forth in an appendix to the petition.

App., infra, 250a-253a.

STATEMENT

Petitioner Richard Rosario was denied habeas

relief by a sharply divided Second Circuit—first, a

two-to-one decision by the panel and then, in four

separate opinions, a six-to-four denial of rehearing en

banc. While acknowledging a violation of Rosario’s

Sixth Amendment right to effective assistance of

counsel, the court of appeals denied habeas relief

because it deferred to the state court’s denial of

Rosario’s claim. The court of appeals so held, even

though the state court applied only New York’s state

constitutional “meaningful representation” standard

to Rosario’s federal claim, instead of the two-part

standard of Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668

(1984). As the dissenting opinions below correctly

determined, application of that state law standard

can result—as it did here—in decisions that are

contrary to, or an unreasonable application of, federal

law.

Under this Court’s clearly established federal

law, the Sixth Amendment right to effective assis

tance of counsel is violated if there is a reasonable

probability that, but for counsel’s error, the outcome

at trial would have been different. Id. at 668. The

New York Court of Appeals, however, has rejected

3

Strickland in favor of New York’s own standard. That

state constitutional standard examines only whether

a defendant received meaningful representation—a

standard that “allows the gravity of individual errors

to be discounted indulgently by a broader view of

counsel’s overall performance.” App., infra, 244a

(Jacobs, C.J., dissenting to denial of rehearing en

banc). Although New York’s standard differs from

Strickland in that outcome-determinative errors by

counsel may not constitute ineffective assistance of

counsel, the Second Circuit repeatedly has sanctioned

application of that state standard to federal claims

raised by New York state prisoners.

Application of New York’s standard to habeas

petitioners’ federal ineffective assistance of counsel

claims has made a difference in this and other cases.

Indeed, this is not even a close case. All five of the

federal judges who examined Rosario’s claim under

Strickland—the magistrate judge, the district court

judge, and all three members of the Second Circuit

panel—concluded that Rosario had been deprived of

his Sixth Amendment right to effective assistance of

counsel. The only basis for denying federal habeas

relief was deference to the state court’s adjudication

of the Sixth Amendment claim. But the state court

never applied Strickland. Instead, in denying relief,

the state court explained that Rosario’s counsel’s

error was a mere “misunderstanding or mistake” that

“was not deliberate” and the error did “not alter the

fact that both attorneys represented defendant skill

fully, and with integrity and in accordance with the

4

standards of ‘meaningful representation’ defined by

[New York] appellate courts.” App., infra, 226a.

Thus, the state court considered the ultimate effect of

counsel’s mistake on the trial outcome to be “ rele

vant, but not dispositive” to the state constitutional

inquiry. App., infra, 223a (quoting People v. Benevon

to, 697 N.E.2d 584, 588 (N.Y. 1998)).

This important and recurring issue will not be

resolved absent this Court’s review. The Second

Circuit repeatedly has refused to hold that New

York’s state standard is contrary to Strickland, and it

denied en banc review here. As the dissent from the

denial of rehearing en banc observed, the conflict

between the state and federal standards ‘likely will

give rise to more cases that will bedevil the district

courts, which are left to sort out case-by-case a prob

lem that is systemic.” App., infra, 242a. This Court

should intervene now and prevent that result. In

deed, given that the Second Circuit is an outlier

among the courts of appeals in deferring to a state

ineffectiveness standard so contrary to Strickland,

summary reversal may be warranted. Alternatively,

the case should be set for full briefing and argument.

A. Constitutional And Statutory Framework

1. In 1996, Congress enacted the Anti terrorism

and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA), Pub. L.

No. 104-132, 110 Stat. 1214. That act imposed new

restrictions on the power of federal courts to grant

writs of habeas corpus to state prisoners. As amended

by AEDPA, Section 2254(d)(1) of Title 28 of the United

5

States Code provides that a writ of habeas corpus for

a state prisoner shall not issue unless the state court

adjudication “resulted in a decision that was contrary

to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly

established Federal law, as determined by the Su

preme Court of the United States.” 28 U.S.C.

§ 2254(d)(1).

In Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362 (2000), this

Court explained that Section 2254(d)(1) “defines two

categories of cases in which a state prisoner may

obtain federal habeas relief with respect to a claim

adjudicated on the merits in state court.” Id. at 404.

First, a state court decision applying federal law is

“contrary to [the Court’s] clearly established prece

dent if the state court applies a rule that contradicts

the governing law set forth in [the Court’s] cases,” or,

when confronting “facts that are materially indistin

guishable from a decision of this Court * * * arrives at

a result different from [the Court’s] precedent.” Id. at

405-406. Second, “[a] state-court decision that cor

rectly identifies the governing legal rule but applies it

unreasonably to the facts of a particular prisoner’s

case” constitutes an unreasonable application of

clearly established federal law. Id. at 407-408.

2. The Sixth Amendment to the United States

Constitution provides, in relevant part, that “[i]n all

criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the

right * * * to have the Assistance of Counsel for his

defence.” This Court has recognized that “the right to

counsel is the right to effective assistance of counsel.”

Strickland, 466 U.S. at 685. In Strickland, the Court

6

held that a defendant’s claim of ineffective assistance

of counsel has two parts: “First, the defendant must

show that counsel’s performance was deficient. * * *

Second, the defendant must show that the deficient

performance prejudiced the defense.” Id. at 687. The

latter prejudice component requires the defendant to

“show that there is a reasonable probability that, but

for counsel’s unprofessional errors, the result of the

proceedings would have been different.” Id. at 694.

3. Article I, Section Six of the New York Consti

tution provides in relevant part: “In any trial in any

court whatever the party accused shall be allowed to

appear and defend in person and with counsel * *

N.Y. Const., art. 1, § 6. The New York Court of Ap

peals has construed this provision to require “effec

tive” aid. People v. Benevento, 697 N.E.2d 584, 586

(N.Y. 1998).

Under the state constitution, whether a defen

dant received effective assistance is measured by

New York’s meaningful representation standard.

Rather than separately examine whether counsel’s

performance was deficient and resulted in prejudice,

the meaningful representation standard involves a

single inquiry: whether “the evidence, the law, and

the circumstances of a particular case, viewed in

totality and as of the time of the representation,

reveal that the attorney provided meaningful repre

sentation.” People v. Baldi, 429 N.E.2d 400, 405 (N.Y.

1981). This analysis is less focused on prejudice and

is “ultimately concerned with the fairness of the

process as a whole rather than its particular impact

7

on the outcome of the case.” Benevento, 697 N.E.2d at

588.

B. State Court Proceedings

1. On June 19, 1996, George Collazo was shot

and killed in the Bronx, New York, while walking

with a friend. The shooting occurred in daytime,

minutes after the victim had an argument with two

men he passed on the street. Two weeks after the

shooting, Rosario was arrested for the murder, based

solely on two stranger eyewitness identifications from

“mug books.” App., infra, 102a. A third eyewitness

had observed the confrontation between Collazo and

the two unknown men, but that witness did not

identify Rosario at trial as a participant in the crime.

App., infra, 103a. No other evidence linked Rosario

to the crime or the victim.

Rosario had been in Florida the entire month of

June 1996. When Rosario learned that police in New

York were looking for him, he left Florida on June 30,

1996 and returned to New York. Rosario arrived in

New York on July 1, 1996 and voluntarily contacted

the police that day. C.A. App. A-788. Rosario denied

any involvement in the shooting. He provided the

police with a detailed alibi statement naming 13

individuals who could confirm that he had spent the

entire previous month in Florida. App., infra, 3a. He

also provided several addresses and phone numbers.

Neither the detectives who took Rosario’s statement

nor the prosecutors who handled the case ever sought

8

to confirm the alibi information provided by Rosario

upon his arrest.

2. Joyce Hartsfield was appointed to represent

Rosario. Hartsfield filed an application in the trial

court for fees to send a defense investigator to Florida

to investigate the 13 alibi witnesses whom Rosario

had identified to the police. C.A. App. A-1042-1045,

A-1398, A-1865-1866. The trial court granted the

application for fees in March 1997. C.A. App. A-1891-

1892. Although Hartsfield remained Rosario’s coun

sel for nearly a year after the fee application had

been granted, she never instructed a defense investi

gator to travel to Florida to interview Rosario’s alibi

witnesses. C.A. App. A-1047-1048, A-1050, A-1399-

1400.

In February 1998, Hartsfield was replaced by

Steven Kaiser as Rosario’s appointed defense counsel.

C.A. App. A-1935. Kaiser mistakenly believed that

the trial court had denied the application for investi

gatory fees, when in fact the court had granted

the application. C.A. App. A-1127-1128, A-1200.

Moreover, Kaiser failed to make his own request for

such fees, and he failed to conduct an investigation in

Florida of Rosario’s alibi witnesses. C.A. App. A-1136.

At trial, the prosecution called three eyewitnesses

to testify. Two of the witnesses identified Rosario as

the shooter; the third eyewitness did not identify

Rosario as the shooter despite prompting from the

prosecutor. The defense presented two alibi witnesses

who testified that Rosario was in Florida at the time

9

of the murder: John Torres, Rosario’s close friend, and

Jenine Seda, John Torres’s fiancee. Each testified

that in June 1996 Rosario stayed at their apartment

in Deltona, Florida until the birth of their first child

on June 20, 1996. Both testified that they knew that

Rosario was in Florida on the day of the murder (on

June 19, 1996) because they specifically recalled

seeing Rosario on the day before the birth of their

son. C.A. App. A-741-742. The prosecution chal

lenged the credibility of Torres’s and Seda’s testimony

due to their close relationship with Rosario. C.A.

App. A-929.

Rosario also took the stand in his own defense.

He testified that he was in Florida at the time of the

murder. He also said that he had lived with Shannon

Beane in Florida from February through April 1996.

The prosecution impeached this latter statement with

Rosario’s Florida arrest record, which demonstrated

that he had been arrested in March 1996 and impris

oned in Florida until April 1996.

Rosario was convicted of second degree murder

and was sentenced to the maximum sentence of 25

years to life. The Appellate Division of the Supreme

Court of New York affirmed the judgment, and the

New York Court of Appeals denied review. People u.

Rosario, 733 N.Y.S.2d 405 (N.Y. App. Div. 2001),

appeal denied, 97 N.Y.2d 760 (2002) (table review).

3. Following his direct appeal, Rosario filed a

motion to vacate the judgment of conviction, pursuant

to Section 440.10 of the New York Criminal Procedure

10

Law. Rosario asserted ineffective assistance of counsel

under the federal and state constitutions.

a. The state trial court conducted an eviden

tiary hearing into Rosario’s claim of ineffective assis

tance of counsel. Rosario proffered seven alibi

witnesses, not including the two who had testified at

the trial. All of these witnesses had been identified

by Rosario in his post-arrest statement or in inter

views with his defense counsel and defense investiga

tor. They corroborated the statements of Rosario and

his trial alibi witnesses that he was in Florida

throughout June 1996, including on the date of the

murder. Their testimony would have provided cor

roboration, additional context, and credibility to the

trial testimony that Rosario was in Florida at the

time of the murder.

Two of these additional witnesses, Chenoa Ruiz

and Fernando Torres, specifically recalled seeing

Rosario in Florida on June 19, 1996, (the day of the

murder) and would have been more persuasive than

the trial alibi witnesses because they were not Ro

sario’s friends. C.A. App. A-1495, A-1501, A-1519;

C.A. App. A-1302, A-1308-1310. Ruiz was a neighbor

of John Torres and Jenine Seda. Ruiz recalled in

particular seeing Rosario in Florida on June 19, 1996,

because, while Ruiz was accompanying Seda to the

doctor on the day before Seda would give birth, Torres

“wasn’t involved like he should have been because he

was hanging out with” Rosario. C.A. App. A-1495.

11

The second additional witness, Fernando Torres,

visited his son’s and Seda’s apartment almost every

day in June 1996, and recalled that Rosario was

living there. C.A. App. A-1302. On the day of the

murder (June 19), Fernando specifically recalled

going with his son and Rosario to purchase car parts

because his son’s car had broken down. C.A. App.

A-1308-1310. Fernando Torres also saw Rosario on

the morning of June 20, when he went to his son’s

apartment. He learned then from Rosario that his

son and Seda were at the hospital and that Seda was

giving birth to his grandson. C.A. App. A-1303-1305.

Fernando Torres again saw Rosario on June 21, when

he met his grandson for the first time at his son’s

apartment. C.A. App. A-1305-1306.

A third witness and a fourth witness, Michael

Serrano and Ricardo Ruiz, further corroborated that

Rosario was in Florida around the time of the murder.

Serrano, a corrections officer, testified that he saw

Rosario frequently in June 1996. C.A. App. A-1708,

A-1712. Serrano recalled seeing Rosario among the

small group that celebrated with John Torres when

he returned from the hospital on June 20. C.A. App.

A-1714. Like Ruiz and Fernando Torres, and unlike

the two alibi witnesses from the trial, Serrano did not

consider himself to be particularly close to Rosario.

C.A. App. A-1716.

The fourth additional witness, Ricardo Ruiz, who

was Chenoa Ruiz’s brother, saw Rosario “[a]ll the

time” at Torres’s and Seda’s apartment during June

1996, both before and after their baby was born. C.A.

App. A-1455.

12

A fifth witness and a sixth witness could have

testified about a specific incident that occurred in

Florida around the time of the Bronx murder. Denise

Hernandez, who dated Rosario throughout June

1996, and her friend, Lysette Rivera, frequently saw

Rosario in Florida throughout June 1996. Hernandez

specifically recalled an argument with Rosario in

mid-June after he borrowed her car without her

permission. C.A. App. A-1620-1621. Hernandez was

upset because a present for her sister’s birthday,

which was on June 26, had been in the car. C.A. App.

A-1621.

Rivera also recalled this incident, which she

believed occurred between five and seven days before

Hernandez’s sister’s birthday on June 26. C.A. App.

A-1662-1665. To the extent Hernandez’s testimony

would have been subject to impeachment due to

Hernandez’s close relationship with Rosario, Rivera’s

testimony would have corroborated the testimony.

Finally, a seventh witness, Minerva Godoy,

testified that Rosario left New York for Florida in

May 1996. She testified that she did not see him

again until he returned to New York on July 1, 1996.

C.A. App. A-1559-1560, A-1565. Godoy explained that

she was in regular contact with Rosario while he was

in Florida during this time, that she called him at a

Florida telephone number, and that she wired money

to Florida for him via Western Union. C.A. App. A-

1562-1564. In particular, Godoy recalled that Rosario

called her from Florida the day after Seda gave birth

and said that he was going to see the baby. C.A. App.

A-1564.

13

Rosario’s counsel also testified at the post

conviction hearing.

Hartsfield testified that she believed it was

“critical” to speak with Rosario’s alibi witnesses in

person. C.A. App. A-1042-1043. She further conceded

that she did not remember that the trial court had

approved her investigator fee request or why she had

never conducted an investigation of Rosario’s Florida

alibi witnesses. C.A. App. A-1047-1048. Moreover,

Hartsfield acknowledged that the failure to investi

gate Rosario’s alibi witnesses in Florida was not a

strategic decision. C.A. App. A-1072.

Trial counsel Kaiser testified that he believed

that Hartsfield’s request for investigative fees had

been denied by the court. C.A. App. A-1127-1128, A-

1200. But he never tried to confirm his understand

ing with the court, renew the application, or pursue a

Florida investigation himself. C.A. App. A-1127-1128,

A-1136, A-1200. Kaiser testified that he would have

“loved” additional alibi witnesses. C.A. App. A-1183-

1184, A-1192-1193, A-1963-1966.

b. The state court denied Rosario’s motion to

vacate the judgment. App., infra, 207a-230a.

The state court noted that both the federal and

state constitutions guarantee the right to effective

assistance of counsel. The court explained, however,

that New York courts had “expressly rejected” the

Strickland standard in favor of New York’s meaning

ful representation requirement. App., infra, 222a n*.

14

The state court noted that the New York mean

ingful representation analysis “is ultimately con

cerned with the fairness of the process as a whole

rather than its particular impact on the outcome of

the case.” App., infra, 222a. As a result, even if a

“defendant would have been acquitted * * * but for

counsel’s errors,” that fact is only “ ‘relevant, but not

dispositive’ ” under the New York constitution. App.,

infra, 223a (quoting Benevento, 697 N.E.2d at 588).

Applying the New York standard, the court

concluded that both counsel “represented [Rosario] in

a thoroughly professional, competent, and dedicated

fashion.” App., infra, 224a. While the court acknowl

edged that Rosario’s counsel had failed to use court-

ordered funds to conduct an alibi investigation in

Florida due to a “misunderstanding or mistake,” that

failure “was not deliberate” and did “not alter the fact

that both attorneys represented Rosario skillfully,

and with integrity and in accordance with the standards

o f ‘meaningful representation’ defined by [New York’s]

appellate courts.” App., infra, 226a.

As evidence that Rosario received a fair process,

the state court also invoked the standard for a claim

of newly discovered evidence and concluded that the

discovery of Rosario’s additional alibi witnesses did

not entitle him to relief. The court reasoned that

such witnesses would not have been sufficient to

satisfy the standard for “a motion for new trial based

on a claim of newly discovered evidence.” App., infra,

227a. The state court explained that this evidence

would have been “cumulative to evidence presented

15

at the trial” and should have been discoverable “with

due diligence.” App., infra, 227a.

4. The Appellate Division denied leave to ap

peal. App., infra, 232a-233a.

C. Proceedings Below

Rosario filed a petition for a writ of habeas

corpus in the United States District Court for the

Southern District of New York.

1. The district court denied habeas relief. Both

the magistrate and district court judges concluded

that Rosario received ineffective assistance of counsel

under the Sixth Amendment. But both also concluded

that Rosario could not meet 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(l)’s

requirements for habeas relief. App., infra, 61a, 75a,

137a-138a.

2. A divided court of appeals affirmed. The

panel majority acknowledged that “some of [its]

colleagues have cautioned that there may be applica

tions of the New York standard that could be in

tension with the prejudice standard in Strickland.”

App., infra, 12a. And the court recognized that the

New York standard “creates a danger that some

courts might misunderstand the New York standard

and look past a prejudicial error as long as counsel

conducted himself in a way that bespoke of general

competency throughout the trial.” App., infra, 15a.

Nevertheless, the court of appeals reaffirmed its

prior holding that New York’s meaningful representa

tion standard is not contrary to Strickland under

16

Section 2254(d)(1). App., infra, 15a. The court thus

explained that Rosario’s only avenue for relief was

through Section 2254(d)(1)’s unreasonable applica

tion- criterion. App., infra, 16a. While the court of

appeals “conclude[d] both prongs of Strickland ha[d]

been met,” App., infra, 17a, the panel majority never

theless concluded that Rosario was not entitled to

habeas relief because the state court’s application of

Strickland was not unreasonable.

Judge Straub dissented in relevant part, noting

that the case “presented] an extraordinarily trou

bling set of circumstances.” App., infra, 21a. The

dissent explained that Rosario’s “defense attorneys

* * * failed to investigate his alibi defense adequately

and did not contact many of the[] potential witnesses.”

App., infra, 22a. Judge Straub observed that the

result of this “colossal failure” was the presentation of

“a relatively weak alibi defense, consisting of only two

alibi witnesses who were subject to impeachment as

interested witnesses because they were close friends

with Rosario.” App., infra, 22a.

As Judge Straub explained, “additional witnesses

could have made all the difference in the world.”

App., infra, 37a. Chenoa Ruiz “would have testified

that she saw Rosario both the night prior to the

murder, when she took Seda to the hospital, and

twice throughout the day of the murder, both before

and after Seda’s doctor’s appointment.” Ibid. Fer

nando Torres “would have placed Rosario in Florida

on three consecutive days beginning with the day of

the murder and would have corroborated [his son’s]

17

testimony that Rosario was with him looking for car

parts on the nineteenth.” App., infra, 37a-38a. And

the other alibi witnesses would have provided further

context “by testifying that they saw Rosario in their

Florida community throughout June of 1996.” App.,

infra, 37a.

Judge Straub noted that “the state court’s use of

the ‘meaningful representation’ standard led it to

focus on certain factors that have little bearing on a

proper Strickland analysis.” App., infra, 43a. Judge

Straub explained that the state court “relied heavily”

on its finding that Rosario’s trial counsel ‘“ represent

ed [him] in a thoroughly professional, competent, and

dedicated fashion.’ ” App., infra, 43a (quoting state

court decision). The dissent noted that the state

court’s analysis was “entirely at odds with Strick

land” because it is “axiomatic that, even if defense

counsel had performed superbly throughout the bulk

of the proceedings, they would still be * * * found

deficient in a material way.” App., infra, 44a. And, to

the extent that state constitutional standard can be,

and was, applied in a manner less favorable than

Strickland, that would constitute an error “clearly

* * * ‘contrary to’ Strickland.” App., infra, 47a.

Judge Straub noted, however, that he did not

need to confront whether application of the state

constitutional standard resulted in a decision contrary

to clearly established federal law because, at a mini

mum, it was an unreasonable application of Strick

land. The dissent explained that it was “clear from

the record that the state court not only unreasonably

18

focused on counsel’s overall performance and mini

mized their mistakes, but also unreasonably dis

counted the alibi evidence adduced at the post

conviction hearing and thus undervalued its prejudi

cial effect.” App., infra, 48a. Indeed, Judge Straub

noted that the state court ruling appeared influenced

by the irrelevant fact that Rosario might not satisfy a

new trial standard based on “newly discovered evi

dence” and that it was “unclear when, if ever, the

court returned to the ineffective assistance of counsel

analysis.” App., infra, 46a-47a.

3. The Second Circuit denied rehearing en banc

in a six-to-four vote.

In a five-judge concurrence, Judge Wesley, who

authored the panel opinion, disagreed that the New

York constitutional standard was contrary to Strick

land.

Judge Katzmann, in his separate concurrence,

noted that the New York standard “could leave room

for New York courts to find a lawyer effective by

focusing on the ‘fairness of the process as a whole’ ”

rather than Strickland’s prejudice requirement, but

that such a result did not occur in this case. App.,

infra, 241a (quoting Benevento, 697 N.E.2d at 588).

19

Four judges dissented from the denial of rehear

ing en banc.1 Chief Judge Jacobs’s opinion on behalf

of the four dissenters explained that New York’s

meaningful representation standard is “contrary to

the standard set forth in Strickland.” App., infra,

242a. The Chief Judge explained that the “New York

test averages out the lawyer’s performance while

Strickland focuses on any serious error and its conse

quences.” App., infra, 244a. This dissent noted that,

as a result of the state constitutional standard, “the

gravity of individual mistakes may be submerged in

an overall assessment of effectiveness, in a way that

violates the federal Constitution.” App., infra, 247a.

In addition to joining the Chief Judge’s dissent,

Judge Pooler filed a separate dissent. She empha

sized that the “state standard can act to deny relief

despite an egregious error from counsel so long as

counsel provides an overall meaningful representa

tion”—a result “contrary to Strickland.” App., infra,

248a.

While sharply divided as to the outcome of this

case, the full court of appeals agreed in one respect:

“that New York state courts would be wise to engage

in separate assessments of counsel’s performance

under both the federal and state standards.” App., *

In addition to the four judges dissenting from the denial of

rehearing, Senior Judge Straub also “endorsed the views ex

pressed” in Chief Judge Jacobs’s dissenting opinion. App., infra,

242a n.l.

20

infra, 240a (Wesley, J., concurring). “Such an exer

cise would ensure that the prejudicial effect of each

error is evaluated with regard to outcome * *

App., infra, 240a; see also App., infra, 241a

(Katzmann, J., concurring); App., infra, 247a (Jacobs,

C.J., dissenting); App., infra, 248a-249a (Pooler, J.,

dissenting).

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION

REVIEW IS NECESSARY BECAUSE NEW

YORK’S “MEANINGFUL REPRESENTATION”

STANDARD RESULTS IN DECISIONS THAT

ARE CONTRARY TO, OR AN UNREASONABLE

APPLICATION OF, STRICKLAND V. WASH

INGTON

This Court should grant review of the Second

Circuit’s blanket rule that application of New York’s

state constitutional meaningful representation

standard to Sixth Amendment claims of ineffective

assistance does not result in a ruling contrary to

clearly established federal law. Under the state

constitutional standard, New York courts are not

guided by whether “there is a reasonable probability

that, but for counsel’s unprofessional errors, the

result of the proceedings would have been different.”

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 694 (1984).

Rather, as the Second Circuit explained, under the

state standard, a defendant must “demonstrate that

he was deprived of a fair trial overall.” App., infra,

11a. That result squarely conflicts with Williams v.

Taylor, 539 U.S. 362 (2000), where this Court held

that it would be contrary to clearly established federal

law for a state court to compel a prisoner to prove

21

more than Strickland requires. It also conflicts with

the decisions of other courts of appeals, which have

not hesitated to grant habeas relief when a state

court, to a habeas petitioner’s detriment, has substi

tuted its own standard for Strickland. Here, applica

tion of New York’s different state standard resulted in

a decision that was contrary to, and an unreasonable

application of, Strickland. As Chief Judge Jacobs

explained in his dissent, absent review, “this defect

will likely give rise to more cases that will bedevil the

district courts, which are left to sort out case-by-case

a problem that is systemic.” App., infra, 242a.

A. The Ruling Below Conflicts With The Habe

as Decisions Of This Court And Other

Courts Of Appeals

Review by this Court is warranted because

application of the New York state constitutional

standard to federal ineffective assistance of counsel

claims results in decisions that are “contrary to” or an

“unreasonable application of” clearly established

federal law. 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1). 1

1. Contrary to clearly established federal

law

a. In this case, the Second Circuit once again

reaffirmed its previous holding that application of

New York’s state constitutional standard to federal

ineffective assistance of counsel claims is not contrary

to Strickland. But, as the dissenting judges explain,

New York’s state constitutional standard sharply

departs from Strickland. Thus, in a class of cases,

22

including this one, that different state standard

results in rulings that are contrary to Strickland.

Indeed, the panel majority and the opinions

concurring in the denial of rehearing en banc all

acknowledge, as they must, that “New York’s test for

ineffective assistance of counsel differs from the

federal Strickland standard.” App., infra, 10a, 238a

(Wesley, J., concurring); see also App., infra, 241a

(Katzmann, J., concurring). For example, rather than

examine whether “the identified acts or omissions

were outside the wide range of professionally compe

tent assistance,” Strickland, 466 U.S. at 690 (empha

sis added), the state court focused on the fact that the

error was a “misunderstanding or mistake” and was

“not deliberate.” App., infra, 226a. And contrary to

this Court’s requirements, that state standard does

not examine whether there is a “reasonable proba

bility that, but for counsel’s unprofessional errors, the

result of the proceeding would have been different.”

Strickland, 466 U.S. at 694. Instead, New York’s

standard asks “whether the error affected the fair

ness of the process as a whole.” App., infra, 222a

(citing People v. Benevento, 697 N.E.2d 584, 588 (N.Y.

1998)).

Application of this state law standard to federal

constitutional claims can and does result in decisions

that cannot be reconciled with Strickland. As the

panel majority recognized, the state law standard

“creates a danger that some courts might misunder

stand the New York standard and look past a prejudi

cial error as long as counsel conducted himself in a

way that bespoke of general competency throughout

23

the trial.” App., infra, 15a. Similarly, Judge Wesley,

while concurring in denial of en banc review,

acknowledged that the state constitutional standard

can “be misapplied to diminish prejudicial effect of a

single error.” App., infra, 238a. And Judge

Katzmann likewise recognized that the state consti

tutional standard “could leave room for New York

courts to find a lawyer effective by focusing on the

‘fairness of the process as a whole,’ rather than on

whether ‘there is a reasonable probability that. . . the

result of the proceeding would have been different’

absent defense counsel’s mistakes.” App., infra, 241a

(citations omitted) (ellipses in original).

In short, as the four judges dissenting from the

denial of rehearing en banc explain, the state consti

tutional standard “allows the gravity of individual

errors to be discounted indulgently by a broader view

of counsel’s overall performance.” App., infra, 244a.

Whereas Strickland “focuses on any serious error and

its consequences,” the New York standard “averages

out the lawyer’s performance.” App., infra, 244a.

And the Second Circuit is not misreading the

New York state constitutional standard. As the New

York Court of Appeals has explained, the state law

standard is more “concerned with the fairness of the

process as a whole rather than its particular impact

on the outcome of the case.” Benevento, 697 N.E.2d at

588. Indeed, the New York Court of Appeals has

“rejected ineffective assistance claims despite signifi

cant mistakes by defense counsel,” because that court

concluded that the counsel’s “overall performance

24

[was] adequate.” People v. Turner, 840 N.E.2d 123,

126 (N.Y. 2005). To the extent the New York Court of

Appeals has held that a single error can amount to

the absence of meaningful representation, it requires

that error to be “clear-cut and completely dispositive.”

Ibid. But Strickland does not require such absolute

proof: a habeas petitioner must demonstrate only

that, but for counsel’s errors, there is a “reasonable

probability” that the outcome would have been differ

ent.

Here, the state court ignored Strickland’s preju

dice standard, and instead expounded that under the

state standard, “whether defendant would have been

acquitted of the charge but for counsel’s errors is

‘relevant, but not dispositive’ ” to an ineffective assis

tance of counsel claim. App., infra, 223a.

b. The Second Circuit’s blanket holding that the

New York standard is not contrary to Strickland—

even though the state standard can require more

than Strickland—cannot be reconciled with the

decisions of this Court and other courts of appeals.

In Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362 (2000), this

Court held that a state court decision is contrary to

clearly established federal law “if the state court

applies a rule that contradicts the governing law set

forth in [the Court’s] cases.” Id. at 405. Thus, the

Court held that the Virginia Supreme Court’s injec

tion of a “fundamental fairness” requirement into

federal ineffective assistance of counsel claims was

contrary to Strickland. Id. at 393. This was so

25

because the state court denied the prisoner’s Sixth

Amendment claim even when he could “show that his

lawyer was ineffective and that his ineffectiveness

probably affected the outcome of the proceeding.” Id.

at 393. Indeed, like the state court ruling in this

case, the Virginia Supreme Court’s decision “turned

on its erroneous view that a ‘mere’ difference in

outcome is not sufficient to establish constitutionally

ineffective assistance of counsel.” Id. at 397.

The Second Circuit’s decision also conflicts with

the rulings of other courts of appeals. The Seventh

Circuit has held that a state court decision is contrary

to clearly established federal law if it imposes a

requirement on a habeas petitioner that is incon

sistent with Strickland. Goodman v. Bertrand, 467

F.3d 1022, 1026 (7th Cir. 2006). Thus, the Seventh

Circuit held that the Wisconsin court’s requirement

that a habeas petitioner prove that the proceeding

was “fundamentally unfair” altered Strickland’s

prejudice requirement in a manner that was “ ‘contra

ry to’ clearly established federal law.” Id. at 1028

(citation omitted).

The Tenth Circuit reached a similar conclusion.

There, the state court held that a “ ‘mere showing

that a conviction would have been different but for

counsel’s errors [did] not suffice to sustain a Sixth

Amendment claim,’ without an additional inquiry into

the fairness of the proceeding.” Spears v. Mullin, 343

F.3d 1215, 1248 (10th Cir. 2003) (citation omitted),

cert, denied, 541 U.S. 909 (2004). The Tenth Circuit

explained that application of that “more onerous

26

standard was contrary to” Strickland. Ibid.; see also

Cargle v. Mullin, 317 F.3d 1196, 1203-05 (10th Cir.

2003) (because Oklahoma’s ineffective assistance of

counsel test requires habeas petitioners to “establish

not only a meritorious omitted issue but also an

improper motive or cause behind counsel’s omission of

the issue,” state court rulings based on that standard

are not entitled to deference).

And the Fifth Circuit similarly has explained

that “to the extent that the state habeas court’s

‘decision turned on its erroneous view that a “mere”

difference in outcome is not sufficient to establish

constitutionally ineffective assistance of counsel,’ the

court’s analysis was ‘contrary to’ S tricklandY oung

v. Dretke, 356 F.3d 616, 629 (5th Cir. 2004) (quoting

Williams, 529 U.S. at 397).

Indeed, the overwhelming precedent of other

courts of appeals holds that a state ineffective assis

tance of counsel standard is contrary to clearly estab

lished federal law when it is applied in a manner that

compels a state prisoner to prove more than a “rea

sonable probability” that the outcome at trial would

have been different. Saranchak v. Beard, 616 F.3d

292 (3d Cir. 2010) (Pennsylvania Supreme Court

“subjective review” prejudice requirement contrary to

Strickland's objective standard); Hummel v. Rosemeyer,

564 F.3d 290, 305 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 130 S. Ct.

784 (2009); Young v. Sirmons, 486 F.3d 655, 680 (10th

Cir. 2007) (Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals’ re

quirement that a habeas petitioner show prejudice

by “ ‘clear and convincing evidence’ ” contrary to

27

Strickland), cert, denied, 552 U.S. 1203 (2008);

Cooper-Smith v. Palmateer, 397 F.3d 1236, 1243 (9th

Cir.) (Oregon court’s “more probable than not” preju

dice requirement contrary to Strickland), cert, de

nied, 546 U.S. 944 (2005); Magana v. Hofbauer, 263

F.3d 542 (6th Cir. 2001) (Michigan Court of Appeals’

standard requiring habeas petitioner to demonstrate

“an absolute certainty that the outcome of the pro

ceedings would be different” contrary to Strickland)',

Rose v. Lee, 252 F.3d 676, 689 (4th Cir.) (North Caro

lina court “applied the wrong burden of proof with

respect to the prejudice prong” when it required the

defendant to prove the result of the proceeding would

be different “ ‘by the preponderance of the evidence’ ”),

cert, denied, 534 U.S. 941 (2001).

To be sure, there can be instances where a state

standard is phrased differently from Strickland, yet it

is not contrary to clearly established federal law. In

such cases, however, other courts of appeals have

held that the state law standard must be “the ‘func

tional equivalent of Strickland.'1'" Castillo v.

Matesanz, 348 F.3d 1, 12 (1st Cir. 2003) (quoting

Ouber v. Guarino, 293 F.3d 19, 31 (1st Cir. 2002)),

cert, denied, 543 U.S. 822 (2004). For example, the

First Circuit has explained that the Massachusetts

and Strickland standards differ only in a “minor

variation in phraseology.” Id. at 14. But, unlike the

New York standard applied in this case, that state

law standard is only linguistically different from

Strickland. It did not conflate the performance and

prejudice requirements of Strickland, so that an

28

outcome determinative error by counsel is overlooked

due to counsel’s otherwise positive performance. By

endorsing a state law standard that allows outcome-

determinative errors to be overlooked, the Second

Circuit is so out of step with the precedent of this

Court and other courts of appeals that summary

reversal may be warranted.

c. The state court’s departure from Strickland

made the difference in this case.

Had the proper standard been applied, Rosario

unquestionably would have been entitled to relief

under Strickland. That is established by the opinions

below. Every federal judge who has reviewed the

record in this case has found a federal constitutional

violation. The magistrate judge, the district court

judge, and all three judges on the Second Circuit

panel agreed that Rosario received constitutionally

deficient representation under Strickland and would

be entitled to relief under de novo review. App., infra,

137a, 61a, 17a, 21a-23a. It was only because the

decisions below deferred to the state court ruling

under 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1) that habeas relief was

denied. But that deference was unwarranted. The

state court never applied Strickland (or any standard

sharing Strickland’s reasoning). Instead, the state

court applied a state law standard that the state

court understood as having “expressly rejected” this

Court’s approach. App., infra, 222a n*.

Nor does the fact that the New York Court of

Appeals believes that, in some circumstances, the

29

New York standard may be more favorable to defen

dants than Strickland excuse the outcome in this

case. App., infra, 11a; see also Turner, 840 N.E.2d at

125-126 (noting that the “meaningful representation”

standard may be “somewhat more favorable to de

fendants”). While the New York standard might be

more protective for defendants as applied in some

other cases, the state court’s application of its own

state law standard here led to a result that fell well

below (and thus was contrary to) what Strickland

requires. Rather than examine whether “there is a

reasonable probability that, but for counsel’s unpro

fessional errors, the result of the proceedings would

have been different,” the state court noted that

Rosario’s counsel “represented defendant in a thor

oughly professional, competent, and dedicated fashion”

and that their error was only a “misunderstanding or

mistake” rather than “deliberate.” App., infra, 226a.

Indeed, to the extent the state court examined

what effect Rosario’s counsel’s error had on the out

come at all, it erroneously did so through the prism of

the state law standard for a new trial based on newly

discovered evidence. App., infra, 227a. But this

Court in Strickland rejected that very approach.

Strickland, 466 U.S. at 694 (rejecting as “not quite

appropriate” a standard that “comports with the

widely used standard for assessing motions for new

trial based on newly discovered evidence”). Neverthe

less, the state court appeared to explain that Rosario

would not be entitled to relief under that new trial

standard because the alibi evidence was “cumulative”

30

to the evidence presented at trial and the “existence”

of his alibi witnesses “was known to the defendant”

before the trial began. App., infra, 227a-228a. That

misses the point: it was Rosario’s counsel’s failure to

investigate the abundance of known alibi witnesses

that was at issue. And the state court excused any

harm it did find based on its belief that Rosario’s

counsel otherwise performed in a professional man

ner. App., infra, 229a.

In any event, the missing alibi evidence was

anything but “cumulative.” As the panel dissent

explained, “additional witnesses could have made all

the difference in the world.” App., infra, 37a. As

discussed below (see pp. 33-35, infra), the additional

witnesses would have corroborated Rosario’s alibi,

provided a fuller picture of his presence in Florida

throughout June 1996, shown additional details at

and around the time of the murder, and been less

vulnerable to impeachment than the two friends who

testified at Rosario’s trial. Moreover, in order to

convict Rosario, rather than “disbelieving two alibi

witnesses who were good friends with Rosario and

Rosario himself, the jury would have had to discredit

at least seven additional witnesses, who would have

corroborated Rosario’s alibi, provided further context

to his defense and testified to additional facts that

had not been elicited at trial.” App., infra, 31a-32a

(Straub, J., dissenting in part and concurring in

part).

31

Because the state court applied a state law

standard incompatible with and more stringent than

Strickland, the state court ruling is contrary to the

“governing law” of this Court. Williams, 529 U.S. at

405. Application of that standard led to the denial

of Rosario’s Sixth Amendment claim. Review and

reversal by this Court is warranted.

2. Unreasonable application o f clearly es

tablished federal law

Even if New York’s one-part meaningful repre

sentation standard were not “contrary to” Strick

land’s two-part test, this Court’s review is

nevertheless necessary because the different state

constitutional standard results in decisions that are

“an unreasonable application of” clearly established

federal law. 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1).

As this Court has explained, a state court deci

sion amounts to an unreasonable application of

Strickland when it applies the “governing legal rule”

in an unreasonable manner to a particular habeas

petitioner’s case. Williams, 529 U.S. at 407-408. “In

order for a federal court to find a state court’s appli

cation of [the Court’s] precedent ‘unreasonable,’ the

state court’s decision must have been more than

incorrect or erroneous.” Wiggins v. Smith, 539 U.S.

510, 520 (2003). That standard is met here. And, if

the Second Circuit’s decision is not reversed, such

unreasonable applications of this Court’s law to

federal ineffectiveness claims by New York state

prisoners will no doubt recur.

32

Because the state court applied the New York

standard to Rosario’s Sixth Amendment claim, the

state court examined only whether Rosario received

“meaningful representation.” App, infra, 222a. It did

not separately examine Rosario’s counsel’s perfor

mance and resulting prejudice. App., infra, 222a-

223a. To salvage the state court’s analysis, the Se

cond Circuit panel majority “translated” the state

court ruling into Strickland terminology. Id. at 19a.

But that artificial dissection of the state court ruling

overlooked the fact that the state court, in applying

its own test, focused on “certain factors that have no

bearing” on Strickland. App., infra, 43a (Straub, J.,

dissenting in part and concurring in part). And those

factors infected the state court’s entire analysis.

App., infra, 246a (Jacobs, C.J., dissenting to denial of

rehearing en banc) (“a finding on a mixed question of

law and fact (such as prejudice) is suspect (at least) if

it is guided by a defective understanding of the law”).

First, the panel majority read the state court

ruling as having somehow implicitly addressed

Strickland’s performance prong. The panel majority

asserted that the state court found no deficiency in

Rosario’s counsel’s performance, and the panel con

cluded that that finding was not an unreasonable

application of Strickland. The Second Circuit ex

plained that the state court found that Rosario’s

counsel acted in a professional manner and that the

failure to investigate further alibi witnesses did “ ‘not

alter this finding.’ ” App., infra, 18a (quoting state

court). But a single error by counsel can amount to

33

deficient performance under Strickland. As the panel

dissent concluded, Rosario’s “counsel essentially

turned a blind eye to the existence of substantial

potentially exculpatory evidence of which it was

aware and, moreover, did so not on the basis of any

reasonable professional judgment, but rather as a

result of pure inadvertence.” App., infra, 48a-49a

(internal quotation marks and citation omitted).

Indeed, counsel conceded there was no legal strategy

to forgoing a more thorough alibi investigation. And

this Court has long recognized that a failure to inves

tigate available exculpatory evidence and to make an

informed judgment about whether to use it at trial is

rarely, if ever, excusable. Kimmelman v. Morrison,

477 U.S. 365, 385 (1986). In that regard, the state

court’s conclusion was an unreasonable application of

Strickland’s performance prong.

Second, as to Strickland’s prejudice prong, the

panel majority cobbled together the conclusion that

the state court implicitly found no prejudice, pointing

to the state court’s conclusion that Rosario’s counsel

put on the best witnesses and the alibi evidence was

largely cumulative. App., infra, 19a-20a. But it was

objectively unreasonable for the state court to deem

the alibi evidence cumulative. After all, the state

court’s reasoning was based at least in part on its

importation of a state law standard for a “motion for

new trial based on a claim of newly discovered evi

dence,” where relief will not be granted if the evi

dence is “cumulative to evidence presented at trial.”

App., infra, 227a.

34

Indeed, the state court compared the two trial

witnesses with the seven post-conviction witnesses,

concluding that the latter were “not as persuasive” as

the two who testified at trial. App., infra, 230a. But

the state court never considered the effect that the

additional witness testimony would have had in

confirming and supporting the testimony of the two

trial witnesses or the mutually reinforcing nature of

the additional alibi testimony. See Williams, 529 U.S.

at 397-398 (holding that the state court’s “prejudice

determination was unreasonable insofar as it failed to

evaluate the totality of the available * * * evidence—

both that adduced at trial, and the evidence adduced

in the habeas proceeding”). As the panel dissent

explained:

All of the other witnesses * * * would have

* * * testified] that they saw Rosario in their

Florida community throughout June of 1996.

They would have provided specific facts re

garding where he lived and what he was do

ing at the time. Several witnesses could have

corroborated each other’s testimony that

Rosario was in Florida on the exact day of

the murder and in the immediately sur

rounding days.

App., infra, 37a. As this Court has explained, “testi

mony of more disinterested witnesses” is not cumula

tive of a defendant’s own self-serving testimony

because it “would quite naturally be given much

greater weight by the jury.” Skipper v. South Carolina,

476 U.S. 1, 8 (1986).

35

And such evidence would have been particularly

important given the relative weakness of the prosecu

tion’s case. The prosecution based its entire case on

the testimony of two stranger eyewitnesses. No other

evidence linked petitioner to the crime. United States

v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218, 235 (1967) (noting that eye

witness accounts of strangers can be “ ‘proverbially

untrustworthy’ ” (citation omitted)); Manson v.

Brathwaite, 432 U.S. 98, 112 (1977) (“The witness’

recollection of the stranger can be distorted easily by

the circumstances or by later actions of the police.”).

This missing alibi evidence would have provided

“indisputably critical data points in establishing that

Rosario was in Florida, and not over 1000 miles away

in New York, when the victim was murdered.” App.,

infra, 38a (Straub, J., dissenting in part and concur

ring in part). In short, the state court “unreasonably

discounted” the additional evidence that was critical

to the defense that Rosario’s counsel failed to investi

gate adequately. Porter v. McCollum, 130 S. Ct. 447,

454 (2009) (per curiam).

B. Continued Application Of New York’s

“Meaningful Representation” Standard

Will Prejudice Habeas Petitioners And

Burden Federal Courts

1. Absent this Court’s review, New York courts

will continue to apply the different state constitution

al standard to federal ineffective assistance of counsel

claims. Because the Second Circuit has categorically

held that New York’s “meaningful representation”

36

standard is not contrary to Strickland, federal courts

will struggle to fit those state court rulings into

Section 2254(d)(l)’s unreasonable application analysis.

This concern is not inchoate. Each year, the New

York courts apply the State’s “meaningful representa

tion” standard to numerous cases where state prison

ers claim ineffective assistance of counsel. Many of

these cases subsequently will be filed under Section

2254 as federal habeas cases. Thus, as Chief Judge

Jacobs observed in his dissent from the denial of

rehearing en banc, “this defect likely will give rise to

more cases that will bedevil the district courts, which

are left to sort out case-by-case a problem that is

systemic.” App., infra, 242a.

Indeed, in a tacit acknowledgment that the state

law standard is contrary to Strickland and will

continue to impose a significant burden on the federal

judiciary, every active judge on the Second Circuit

recommended, in response to Rosario’s petition for

rehearing en banc, that New York state courts apply

both the federal and state standards to “ensure that

the prejudicial effect of each error is evaluated with

regard to outcome.” App., infra, 240a (Wesley, J.,

concurring); see also App., infra, 241a (Katzmann, J.,

concurring); App., infra, 247a (Jacobs, C.J., dissent

ing); App., infra, 248a-249a (Pooler, J., dissenting).

This directive from the Second Circuit to New York

state courts reveals that the active judges on the

Second Circuit have no confidence that New York

courts are actually applying the malleable New York

37

standard in a manner consistent with Strickland. If

the meaningful representation standard were in fact

always at least as protective as Strickland, this

recommendation would have been unnecessary. In

any event, Strickland is not simply a recommenda

tion to be followed only as state courts see fit. The

New York courts’ failure to apply it in this case and

many others makes this Court’s review imperative.

2. Moreover, it now should be plain that the

recurring issue raised by this petition will not be

resolved absent this Court’s review.

While the Second Circuit long has struggled to

reconcile New York’s meaningful representation

standard with Strickland, it has done so without

success. A decade ago, the court of appeals first

concluded that application of the state constitutional

standard to Sixth Amendment ineffective assistance

of counsel claims was not contrary to Strickland.

Lindstadt v. Keane, 239 F.3d 191, 198 (2d Cir. 2001);

Loliscio v. Goord, 263 F.3d 178, 193 (2d Cir. 2001).

Subsequent decisions have held that the Second

Circuit is “bound to follow” that precedent. Eze v.

Senkowski, 321 F.3d 110, 124 (2d Cir. 2003).

Although some members of the Second Circuit

have expressed the view that the New York state

standard and Strickland might conflict, the Second

Circuit has not taken the issue en banc. For example,

in Henry v. Poole, 409 F.3d 48 (2d Cir. 2005), cert,

denied, 547 U.S. 1040 (2006), the Second Circuit

38

paused on, but did not address, “whether the New

York standard is not contrary to Strickland.” Id. at

70. And, in a separate opinion in Poole, Judge Sack

concluded that, “assuming that the Supreme Court

does not give us guidance in the interim, we might be

well advised to consider the appeal for en banc review

as a means to reconsider the issue.” Id. at 72-73

(Sack, J., concurring). The denial of rehearing en

banc in this case makes clear, however, that a majori

ty of the full court of appeals has declined to heed

that advice and that this Court’s guidance is now

needed.

3. Finally, this case presents an ideal vehicle to

address the question presented. As shown above,

application of the New York standard was outcome-

determinative in this case. Every federal judge who

has examined Rosario’s Sixth Amendment ineffective

assistance of counsel claim-—the magistrate judge,

the district court judge, and all three judges on the

Second Circuit panel—has concluded that Rosario

received constitutionally deficient assistance of

counsel and was prejudiced as a result of counsel’s

error. App., infra, 137a, 61a, 17a, 21a-23a.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, the petition for a

writ of certiorari should be granted. The Court may

wish to consider summarily reversing the judgment of

39

the court of appeals; in the alternative, the Court

should set the case for briefing and oral argument.

Respectfully submitted,

John Payton

Director-Counsel

Debo P. Adegbile

Christina Swarns

Jin Hee Lee

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson St., Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

Leah F. W ilson

Morrison & Foerster llp

425 Market St.

San Francisco, CA 94105

Deanne E. Maynard

Counsel of Record

Brian R. Matsui

Morrison & Foerster llp

2000 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 887-1500

dmaynard@mofo.com

Carl H. Loewenson, Jr.

Le d aA. Moloff

M orrison & Foerster llp

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

Counsel for Petitioner

December 29, 2010

mailto:dmaynard@mofo.com

la

APPENDIX A

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For the Second C ircuit

August Term, 2009

(Argued: November 19, 2009 Decided: April 12, 2010)

Docket No. 08-5521-pr

Richard Rosario,

Petitioner-Appellant,

— v. —

Supt. Robert E rcole, Green H aven Correctional

Facility , A ttorney General E liot Spitzer,

Respondents-Appellees.

Before:

Cabranes, Straub , W esley, Circuit Judges.

Richard Rosario appeals from a judgment of the

United States District Court for the Southern District

of New York (Castel, J.), entered on October 23, 2008,

denying his petition for a writ of habeas corpus. We

hold that the state court’s review of Rosario’s ineffec

tive assistance of counsel claims was neither contrary

to, nor an unreasonable application of, Strickland v.

Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984).

2a

Affirmed. Judge Straub concurs in part and

dissents in part in a separate opinion.

Jodi K. M iller, Morrison & Foerster, LLP, New York,

N.Y. (Carl H. Loewenson, Morrison & Foerster,

LLP, New York, NY, and Jin Hee Lee, NAACP

Defense and Education Fund, Inc., on the brief),

for Petitioner-Appellant.

Joseph N. F erdenzi, Assistant District Attorney,

Bronx, N.Y. (Christopher J. Blira-Koessler, Assis

tant District Attorney, Bronx, NY, for Robert T.

Johnson, District Attorney, Bronx County), for

Respondents-Appellees.

W esley , Circuit Judge:

This case requires us to examine New York law

and analyze one sentence in a New York Court of

Appeals opinion that has troubled our circuit since its

publication.

Background

On June 19, 1996, George Collazo was shot and

killed in the Bronx while walking with his friend

Michael Sanchez. The daytime shooting followed an

argument sparked by Collazo’s racial epithet to two

men as he and Sanchez passed them. Sanchez later

identified appellant Richard Rosario as Collazo’s

assailant. Robert Davis, a porter working at a nearby

building, witnessed the murder and also identified

3a

Rosario as the shooter. A third eyewitness was also

present, but did not identify Rosario as a participant

in the crime.

Rosario was arrested for the murder on July 1,

1996, after he voluntarily returned to New York from

Florida. From the time of his arrest, Rosario claimed

he was in Florida when Collazo was shot. Rosario

provided the police with a statement, maintained his

innocence, and listed the names of thirteen people

who could corroborate his alibi.

Before Rosario’s trial began, he was assigned

Joyce Hartsfield as counsel. Hartsfield brought an

application before the court requesting funds for a

private investigator to travel to Florida and interview

the potential alibi witnesses. The court granted the

application. Hartsfield was eventually replaced as

counsel by Steven Kaiser in February of 1998. Kaiser

had a mistaken belief that the application for investi

gation fees had been denied. Kaiser did not make a

request for fees; no investigation of alibi witnesses

was done in Florida.

During the trial, the prosecution called Sanchez

and Porter, who identified Rosario as the shooter, and

the third eyewitness, who failed to identify Rosario.

The defense presented two alibi witnesses - John

Torres, a friend of Rosario, and Jenine Seda, John