Brown v. Board of Education Appendix to Appellants' Briefs

Public Court Documents

September 22, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Appendix to Appellants' Briefs, 1952. b02767cf-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a759bfab-ae1e-4678-a7c9-410d65910835/brown-v-board-of-education-appendix-to-appellants-briefs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

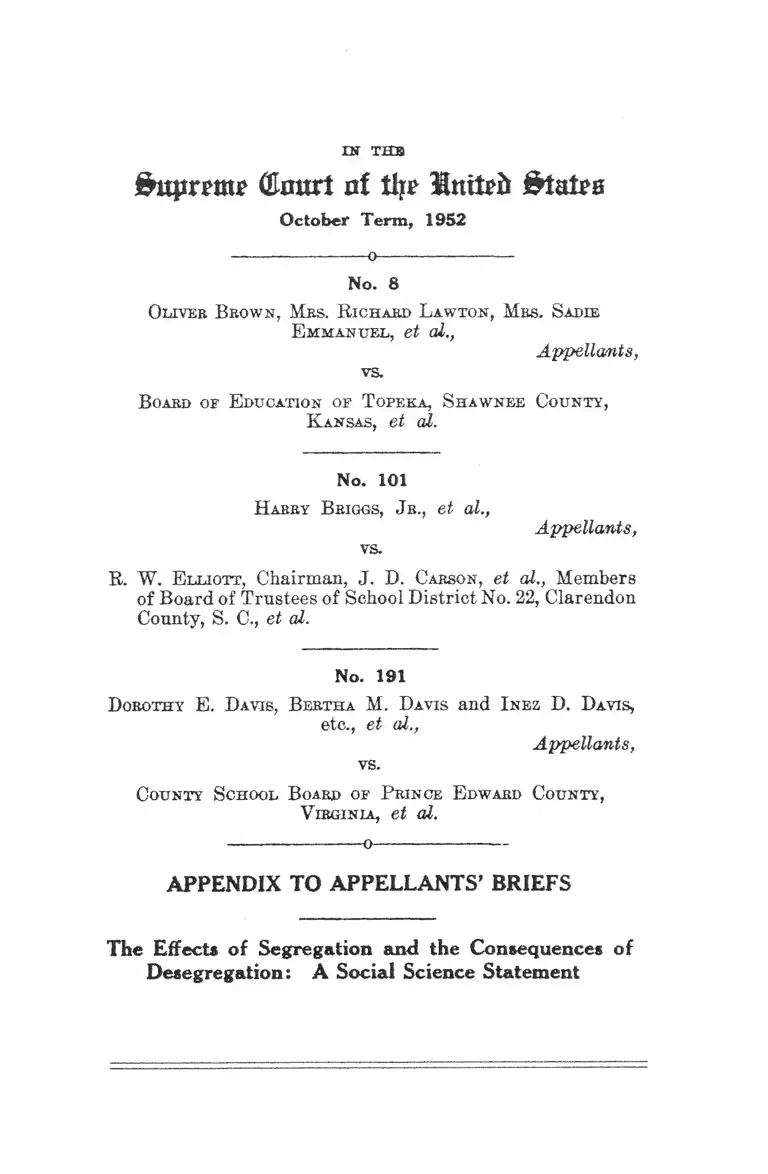

IN THB

&itpmn£ QJmtrl of the Initrh Stairs

October Term, 1952

-a

No. 8

Oliver B rown, Mrs. R ichard L awton, Mrs. Sadie

E mmanuel, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

B oard or E ducation o f T opeka, Shawnee County,

K ansas, et al.

No. 101

H arry B riggs, J r ., et al.,

vs.

Appellants,

R. W. E lliott, Chairman, J. D. Carson, et al., Members

of Board of Trustees of School District No. 22, Clarendon

County, S. C., et al.

No. 191

Dorothy E. D avis, B ertha M. Davis and I nez D. D avis,

etc., et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

County School B oard of P rince E dward County,

V irginia, et al.

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEFS

The Effect* of Segregation and the Consequences of

Desegregation: A Social Science Statement

Statement of Counsel

The following statement was drafted and signed by

some of the foremost authorities in sociology, anthropology,

psychology and psychiatry who have worked in the area

of American race relations. It represents a consensus of

social scientists with respect to the issue presented in these

appeals. As a summary of the best available scientific

evidence relative to the effects o f racial segregation on the

individual, we file it herewith as an appendix to our briefs.

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall,

S pottswood W. R obinson, III,

Counsel for Appellants.

IN THS

f^upremr (Hour! nf tin' Init^in i&atPH

October Term, 1952

— o—

No. 8

Oliver B rown, Mrs. R ichard L awton, Mrs. Sadie

E mmanuel, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

B oard of E ducation of T opeka, Shawnee County,

K ansas, et al.

No. 101

H arry B riggs, Jr., et al.,

vs.

Appellants,

R. W. E lliott, Chairman, J. D. Carson, et al., Members

of Board of Trustees of School District No. 22, Clarendon

County, S. C., et al.

No. 191

Dorothy E. Davis, B ertha M. D avis and I nez D. D avis,

etc., et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

County School B oard of Prince E dward County,

V irginia, et al.

----------------------o----------------------

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEFS

The Effects of Segregation and the Consequences of

Desegregation: A Social Science Statement

I

The problem of the segregation of racial and ethnic

groups constitutes one of the major problems facing the

2

American people today. It seems desirable, therefore, to

summarize the contributions which contemporary social

science can make toward its resolution. There are, of

course, moral and legal issues involved with respect to which

the signers of the present statement cannot speak with

any special authority and which must be taken into ac

count in the solution of the problem. There are, however,

also factual issues involved with respect to which certain

conclusions seem to be justified on the basis of the available

scientific evidence. It is with these issues only that this

paper is concerned. Some of the issues have to do with

the consequences of segregation, some with the problems

of changing from segregated to unsegregated practices.

These two groups of issues will be dealt with in separate

sections below. It is necessary, first, however, to define

and delimit the problem to be discussed.

Definitions

For purposes of the present statement, segregation

refers to that restriction of opportunities for different

types of associations between the members of one racial,

religious, national or geographic origin, or linguistic gToup

and those of other groups, which results from or is sup

ported by the action of any official body or agency represent

ing some branch of government. We are not here con

cerned with such segregation as arises from the free

movements of individuals which are neither enforced nor

supported by official bodies, nor with the segregation of

criminals or of individuals with communicable diseases

which aims at protecting society from those who might

harm it.

Where the action takes place in a social milieu in which

the groups involved do not enjoy equal social status, the

group that is of lesser social status will be referred to as

the segregated group.

3

In dealing with the question of the effects of segrega

tion, it must be recognized that these effects do not take

place in a vacuum, but in a social context. The segregation

of Negroes and of other groups in the United States takes

place in a social milieu in which ‘ ‘ race prejudice and

discrimination exist. It is questionable in the view of

some students of the problem whether it is possible

to have segregation without substantial discrimination.

Myrdal1 states: “ Segregation * * * is financially possible

and, indeed, a device of economy only as it is combined

with substantial discrimination’ ’ (p. 629). The imbeded-

ness of segregation in such a context makes it difficult to

disentangle the effects of segregation per se from the effects

of the context. Similarly, it is difficult to disentangle the

effects of segregation from the effects of a pattern of

social disorganization commonly associated with it and

reflected in high disease and mortality rates, crime and

delinquency, poor housing, disrupted family life and general

substandard living conditions. We shall, however, return

to this problem after consideration of the observable effects

of the total social complex in which segregation is a major

component.

II

At the recent Mid-century White House Conference on

Children and Youth, a fact-finding report on the effects of

prejudice, discrimination and segregation on the person

ality development of children was prepared as a basis for

some of the deliberations.2 This report brought together

the available social science and psychological studies which

were related to the problem of how racial and religious pre

1 Myrdal, G., An American Dilemma, 1944.

2 Clark, K. B„ Effect of Prejudice and Discrimination on Per

sonality Development. Fact Finding Report Mid-century White

House Conference on Children and \outh, Childrens Bureau, Fed

eral Security Agency, 1950 (mimeographed).

4

judices influenced the development of a healthy personality.

It highlighted the fact that segregation, prejudices and

discriminations, and their social concomitants potentially

damage the personality of all children—the children of the

majority group in a somewhat different way than the more

obviously damaged children of the minority group.

The report indicates that as minority group children

learn the inferior status to which they are assigned—as

they observe the fact that they are almost always segregated

and kept apart from others who are treated with more

respect by the society as a whole—they often react with

feelings of inferiority and a sense of personal humiliation.

Many of them become confused about their own personal

worth. On the one hand, like ail other human beings they

require a sense of personal dignity; on the other hand,

almost nowhere in the larger society do they find their own

dignity as human beings respected by others. Under these

conditions, the minority group child is thrown into a conflict

with regard to his feelings about himself and his group.

He wonders whether his group and he himself are worthy

of no more respect than they receive. This conflict and

confusion leads to self-hatred and rejection of his own

group.

The report goes on to point out that these children

must find ways with which to cope with this conflict. Not

every child, of course, reacts with the same patterns of

behavior. The particular pattern depends upon many

interrelated factors, among which are: the stability and

quality of his family relations; the social and economic

class to which he belongs; the cultural and educational

background of his parents; the particular minority group

to which he belongs; his personal characteristics, intelli

gence, special talents, and personality pattern.

Some children, usually of the lower socio-economic

classes, may react by overt aggressions and hostility

5

directed toward their own group or members of the dominant

group.3 Anti-social and delinquent behavior may often be

interpreted as reactions to these racial frustrations. These

reactions are self-destructive in that the larger society not

only punishes those who commit them, but often interprets

such aggressive and anti-social behavior as justification

for continuing prejudice and segregation.

Middle class and upper class minority group children

are likely to react to their racial frustrations and conflicts

by withdrawal and submissive behavior. Or, they may

react with compensatory and rigid conformity to the pre

vailing middle class values and standards and an aggressive

determination to succeed in these terms in spite of the

handicap of their minority status.

The report indicates that minority group children of

all social and economic classes often react with a generally

defeatist attitude and a lowering of personal ambitions.

This, for example, is reflected in a lowering of pupil morale

and a depression of the educational aspiration level among

minority group children in segregated schools. In pro

ducing such effects, segregated schools impair the ability

of the child to profit from the educational opportunities

provided him.

Many minority group children of all classes also tend

to be hypersensitive and anxious about their relations with

the larger society. They tend to see hostility and rejection

even in those areas where these might not actually exist.

3 Bren man, M., The Relationship Between Minority Group Iden

tification in A Group of Urban Middle Class Negro Girls, / . Sac.

Psychol., 1940, 11, 171-197; Brenman, M., Minority Group Mem

bership and Religious, Psychosexual and Social Patterns in A Group

of Middle-Class Negro Girls, J. Soc. Psychol, 1940. 12. 179-1%;

Brenman, M., Urban Lower-Class Negro Girls, Psychiatry, 1943. 6,

307-324; Davis, A., The Socialization of the American Negro Child

and Adolescent, J. Negro Educ., 1939, 8, 264-275.

6

The report concludes that while the range of individual

differences among members of a rejected minority group is

as wide as among other peoples, the evidence suggests that

all of these children are unnecessarily encumbered in some

ways by segregation and its concomitants.

With reference to the impact of segregation and its con

comitants on children of the majority group, the report

indicates that the effects are somewhat more obscure. Those

children who learn the prejudices of our society are also

being taught to gain personal status in an unrealistic and

non-adaptive way. When comparing themselves to mem

bers of the minority group, they are not required to evalu

ate themselves in terms of the more basic standards of

actual personal ability and achievement. The culture per

mits and, at times, encourages them to direct their feelings

of hostility and aggression against whole groups of people

the members of which are perceived as weaker than them

selves. They often develop patterns of guilt feelings,

rationalizations and other mechanisms which they must

use in an attempt to protect themselves from recognizing

the essential injustice of their unrealistic fears and hatreds

of minority groups.4

The report indicates further that confusion, conflict,

moral cynicism, and disrespect for authority may arise in

majority group children as a consequence of being taught

the moral, religious and democratic principles of the broth

erhood of man and the importance of justice and fair play

by the same persons and institutions who, in their support

of racial segregation and related practices, seem to be act

ing in a prejudiced and discriminatory manner. Some

individuals may attempt to resolve this conflict by intensify

ing their hostility toward the minority group. Others may

react by guilt feelings which are not necessarily reflected

in more humane attitudes toward the minority group. Still

* Adorno, T. W .; Frenkel-Brunswik, E .; Levinson, D. J.; San

ford, R. N., The Authoritarian Personality, 1951.

n(

others react by developing an unwholesome, rigid, and

uncritical idealization of all authority figures—their par

ents, strong political and economic leaders. As described

in The Authoritarian Personality,5 6 they despise the weak,

while they obsequiously and unquestioningly conform to the

demands of the strong whom they also, paradoxically, sub

consciously hate.

With respect to the setting in which these difficulties

develop, the report emphasized the role of the home, the

school, and other social institutions. Studies 6 have shown

that from the earliest school years children are not only

aware of the status differences among different groups

in the society but begin to react with the patterns described

above.

Conclusions similar to those reached by the Mid-century

White House Conference Report have been stated by other

social scientists who have concerned themselves with this

problem. The following are some examples of these con

clusions :

Segregation imposes upon individuals a distorted sense

of social reality.7

5 Adorno, T. W .; Frenkel-Brunswik, E .; Levinson, D. J . ; San

ford, R. N „ The Authoritarian Personality, 1951.

6 Clark, K. B. & Clark, M. P., Emotional Factors in Racial Iden

tification and Preference in Negro Children, J. Negro Educ., 1950,

19, 341-350; Clark, K. B. & Clark, M. P., Racial Identification and

Preference in Negro Children, Readings in Social Psychology, Ed.

by Newcomb & Hartley, 1947; Radke, M .; Trager, H .; Davis, H.,

Social Perceptions and Attitudes of Children, Genetic Psychol.

Monog., 1949, 40, 327-447; Radke, M .; Trager, H .; Children’s Per

ceptions of the Social Role of Negroes and Whites, / . Psychol., 1950.

29, 3-33.

7 Reid, Ira, What Segregated Areas Mean; Brameld, T „ Edu

cational Cost, Discrimination and Naticmal Welfare, Ed. by Maclver,

R. M., 1949.

8

Segregation leads to a blockage in the communications

and interaction between the two groups. Such blockages

tend to increase mutual suspicion, distrust and hostility.8

Segregation not only perpetuates rigid stereotypes and

reinforces negative attitudes toward members of the other

group, but also leads to the development of a social climate

within which violent outbreaks of racial tensions are likely

to occur.9

We return now to the question, deferred earlier, of

what it is about the total society complex of which segrega

tion is one feature that produces the effects described

above— or, more precisely, to the question of whether we

can justifiably conclude that, as only one feature of a com

plex social setting, segregation is in fact a significantly

contributing factor to these effects.

To answer this question, it is necessary to bring to

bear the general fund of psychological and sociological

knowledge concerning the role of various environmental

influences in producing feelings of inferiority, confusions

in personal roles, various types of basic personality struc

tures and the various forms of personal and social dis

organization.

On the basis of this general fund of knowledge, it seems

likely that feelings of inferiority and doubts about per

sonal worth are attributable to living in an underprivileged

environment only insofar as the latter is itself perceived

as an indicator of low social status and as a symbol of

inferiority. In other words, one of the important determi

nants in producing such feelings is the awareness of social

status difference. While there are many other factors that

serve as reminders of the differences in social status, there

can be little doubt that the fact of enforced segregation is

a major factor.10

8 Frazier, E., The Negro in the United States, 1949; Krech, D. &

Crutchfield, R. S., Theory and Problems of Social Psychology, 1948;

Newcomb, T., Social Psychology, 1950.

6 Lee, A. McCiung and Humphrey, N. D., Race Riot, 1943.

10 Frazier, E., The Negro in the United States, 1949; Myrdal, G.,

An American Dilemma, 1944.

9

This seems to be true for the following reasons among

others: (1) because enforced segregation results from the

decision of the majority group without the consent of the

segregated and is commonly so perceived; and (2) because

historically segregation patterns in the United States were

developed on the assumption of the inferiority of the

segregated.

In addition, enforced segregation gives official recogni

tion and sanction to these other factors of the social com

plex, and thereby enhances the effects of the latter in

creating the awareness of social status differences and

feelings of inferiority.11 The child who, for example, is

compelled to attend a segregated school may be able to

cope with ordinary expressions of prejudice by regarding

the prejudiced person as evil or misguided; but he cannot

readily cope with symbols of authority, the full force of the

authority of the State—the school or the school board, in

this instance—in the same manner. Given both the ordi

nary expression of prejudice and the school’s policy of

segregation, the former takes on greater force and seem

ingly becomes an official expression of the latter.

Not all of the psychological traits which are commonly

observed in the social complex under discussion can be

related so directly to the awareness of status differences—

which in turn is, as we have already noted, materially con

tributed to by the practices of segregation. Thus, the

low level of aspiration and defeatism so commonly ob

served in segregated groups is undoubtedly related to the

level of self-evaluation; but it is also, in some measure,

related among other things to one’s expectations with

regard to opportunities for achievement and, having

achieved, to the opportunities for making use of these

achievements. Similarly, the hypersensitivity and anxiety

displayed by many minority group children about their

11 Reid. Ira, What Segregated Areas Mean, Discrimination and

National Welfare, Ed. by Maclver, R. M., 1949.

10

relations with the larger society probably reflects their

awareness of status differences; but it may also be influ

enced by the relative absence of opportunities for equal

status contact which would provide correctives for prevail

ing unrealistic stereotypes.

The preceding view is consistent with the opinion stated

by a large majority (9 0 % ) of social scientists who replied

to a questionaire concerning the probable effects of en

forced segregation under conditions of equal facilities.

This opinion was that, regardless of the facilities which

are provided, enforced segregation is psychologically detri

mental to the members of the segregated group.12

Similar considerations apply to the question of what

features of the social complex of which segregation is a

part contribute to the development of the traits which

have been observed in majority group members. Some of

these are probably quite closely related to the awareness

of status differences, to which, as has already been pointed

out, segregation makes a material contribution. Others

have a more complicated relationship to the total social

setting. Thus, the acquisition of an unrealistic basis for

self-evaluation as a consequence of majority group member

ship probably reflects fairly closely the awareness of status

differences. On the other hand, unrealistic fears and

hatreds of minority groups, as in the case of the converse

phenomenon among minority group members, are prob

ably significantly influenced as well by the lack of oppor

tunities for equal status contact.

With reference to the probable effects of segregation

under conditions of equal facilities on majority group

members, many of the social scientists who responded to

the poll in the survey cited above felt that the evidence is

12 Deutscher, M. and Ohein, I., The Psychological Effects of

Enforced Segregation: A Survey of Social Science Opinion,

J. P s y c h o l1948, 26, 259-287.

11

less convincing than with regard to the probable effects

of such segregation on minority group members, and the

effects are possibly less widespread. Nonetheless, more

than 80% stated it as their opinion that the effects of such

segregation are psychologically detrimental to the majority

group members.13

It may be noted that many of these social scientists

supported their opinions on the effects of segregation on

both majority arid minority groups by reference to one

or another or to several of the following four lines of

published and unpublished evidence.14 * First, studies of

children throw light on the relative priority of the aware

ness of status differentials and related factors as compared

to the awareness of differences in facilities. On this basis,

it is possible to infer some of the consequences of segre

gation as distinct from the influence of inequalities of

facilities. Second, clinical studies and depth interviews

throw light o il the genetic sources and causal sequences

of various patterns of psychological reaction; and, again,

certain inferences are possible with respect to the effects

of segregation per se. Third, there actually are some

relevant but relatively rare instances of segregation with

equal or even superior facilities, as in the cases of certain

Indian reservations. Fourth, since there are inequalities

of facilities in racially and ethnically homogeneous groups,

it is possible to infer the kinds of effects attributable to

such inequalities in the absence of effects of segregation

and, by a kind of subtraction to estimate the effects of

segregation per se in situations where one finds both segre

gation and unequal facilities.

13 Deutscher, M. and Chein, I., The Psychological Effects of

Enforced Segregation: A Survey of Social Science Opinion,

J. Psychol., 1948, 26, 259-287.

14 Chein, I., What Are the Psychological Effects of Segregation

Under Conditions of Equal Facilities?, /nternational J. Opinion and

Attitude Res.. 1949, 2, 229-234.

12

III

Segregation is at present a social reality. Questions

may be raised, therefore, as to what are the likely conse

quences of desegregation.

One such question asks whether the inclusion of an

intellectually inferior group may jeopardize the education

of the more intelligent group by lowering educational

standards or damage the less intelligent group by placing

it in a situation where it is at a marked competitive dis

advantage. Behind this question is the assumption, which

is examined below, that the presently segregated groups

actually are inferior intellectually.

The available scientific evidence indicates that much,

perhaps all, of the observable differences among various

racial and national groups may be adequately explained

in terms of environmental differences.15 It has been found,

for instance, that the differences between the average

intelligence test scores of Negro and white children de

crease, and the overlap of the distributions increases, pro

portionately to the number of years that the Negro children

have lived in the North.16 17 18 Related studies have shown

that this change cannot be explained by the hypothesis of

selective migration.11 It seems clear, therefore, that fears

based on the assumption of innate racial differences in

intelligence are not well founded.

It may also be noted in passing that the argument

regarding the intellectual inferiority of one group as com

pared to another is, as applied to schools, essentially an

16 Klineberg, O., Characteristics o f American Negro, 1945;

Klineberg, O., Race Differences, 1936.

16 Klineberg, O., Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration,

1935.

17 Klineberg, O., Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration,

1935.

13

argument for homogeneous groupings of children by intelli

gence rather than by race. Since even those who believe

that there are innate differences between Negroes and

whites in America in average intelligence grant that con

siderable overlap between the two groups exists, it would

follow that it may be expedient to group together the

superior whites and Negroes, the average whites aaid

Negroes, and so on. Actually, many educators have come

to doubt the wisdom of class groupings made homogeneous

solely on the basis of intelligence.* 18 Those who are opposed

to such homogeneous grouping believe that this type of

segregation, too, appears to create generalized feelings of

inferiority in the child who attends a below average class,

leads to undesirable emotional consequences in the education

of the gifted child, and reduces learning opportunities which

result from the interaction of individuals with varied gifts.

A second problem that comes up in an evaluation of the

possible consequences of desegregation involves the ques

tion of whether segregation prevents or stimulates inter

racial tension and conflict and the corollary question of

whether desegregation has one or the other effect.

The most direct evidence available on this problem comes

from observations and systematic study of instances in

which desegregation has occurred. Comprehensive reviews

of such instances 19 clearly establish the fact that desegrega

18 Brooks, J. J., Interage Grouping on Trial-Continuous Learn

ing, Bulletin 4pS7, Association for Childhood. Education. 1951 ;

Lane, R. H., Teacher in Modern Elementary School, 1941 ; Edu

cational Policies Commission of the National Education Asso

ciation and the American Association of School Administration

Report in Education For All Americans, published by the N. E. A.

1948.

18 Delano, W., Grade School Segregation: The Latest Attack

on Racial Discrimination, Vale Law Journal, 1952, 61, 5, 730-744;

Rose, A., The Influence of Legislation on Prejudice; Chapter 53 in

Race Prejudice and Discrimination, Ed. by Rose, A., 1951; Rose, A.,

Studies in Reduction of Prejudice, Amer. Council on Race Relations,

1948.

H

tion has been carried out successfully in a variety of situa

tions although outbreaks of violence had been commonly

predicted. Extensive desegregation has taken place with

out major incidents in the armed services in both Northern

and Southern installations and involving officers and enlisted

men from all parts of the country, including the South.20

Similar changes have been noted in housing21 and in

dustry.22 During the last war, many factories both in the

North and South hired Negroes on a non-segregated, non-

discriminatory basis. While a few strikes occurred, refusal

20 Kenworthy, E. W., The Case Against Army Segregation,

Annals of the Atnerican Academy of Political and Social Science,

1951, 275, 27-33; Nelson, Lt. D. D., The Integration of the

Negrp in the U. S. Navy, 1951 ; Opinions About Negro Infantry

Platoons in White Companies in Several Divisions, Information and

Education Division, U. S. War Department, Report No. B-157,

1945.

21 Conover, R. D., Race Relations at Codornices Village, Berke

ley-Albany, California: A Report of the Attempt to Break Down

the Segregated Pattern on A Directly Managed Housing Project,

Housing and Home Finance Agency, Public Housing Administra

tion, Region I, December 1947 (mimeographed ) ; Deutsch, M. and

Collins, M. E., Interracial Housing, A Psychological Study of A

Social Experiment, 1951; Rutledge, E., Integration of Racial Minor

ities in Public Housing Projects: A Guide for Local Housing

Authorities on How to Do It, Public Housing Administration, New

York Field Office (mimeographed)

22 Minard, R. D,, The Pattern of Race Relationships in the Poca

hontas Coal Field, J. Social Issues, 1952, 8, 29-44; Southall, S. E.,

Industry’s Unfinished Business, 1951 ; Weaver, G. L-P, Negro Labor,

A National Problem, 1941.

15

by management and unions to yield quelled all strikes within

a few days.23.

Relevant to this general problem is a comprehensive

study of urban race riots which found that race riots oc

curred in segregated neighborhoods, whereas there was

no violence in sections of the city where the two races

lived, worked and attended school together.2*

Under certain circumstances desegregation not only pro

ceeds without major difficulties, but has been observed to

lead to the emergence of more favorable attitudes and

friendlier relations between races. Relevant studies may

be cited with respect to housing,25 * * 28 employment,29 the armed

23 Southall, S. E., Industry’s Unfinished Business, 1951;

Weaver, G. L-P, Negro Labor, A National Problem, 1941.

24 Lee, A. McClung and Humphrey, N. D., Race Riot, 1943;

Lee, A. McClung, Race Riots Aren’t Necessary, Public Affairs

Pamphlet, 1945.

25 Deutsch, M. and Collins, M. E., Interracial Housing, A Psy

chological Study o f A Social Experiment, 1951; Merton, R. K .;

West, P. S .; Jahoda, M., Social Fictions and Social Facts: The

Dynamics of Race Relations in HUltown, Bureau of Applied Social

Research Columbia, Univ,, 1949 (mimeographed) ; Rutledge, E.,

Integration of Racial Minorities in Public Housing Projects; A

Guide for Local Housing Authorities on How To Do It., Pubiic

Housing Administration, New York Field Office (mimeographed) ;

Wilner, D. M .; Walkley, R. P .; and Cook, S. W., Intergroup Con

tact and Ethnic Attitudes in Public Housing Projects, J. Social Issues,

1952, 8, 45-69.

28 Harding, J., and Hogrefe, R., Attitudes of White Department

Store Employees Toward Negro Co-workers, / . Social Issues, 1952,

8, 19-28; Southall, S. E., Industry’s Unfinished Business, 1951;

Weaver, G. L-P., Negro Labor, A National Problem, 1941.

16

services 27 and merchant marine,28 29 30 recreation agency,39 and

general community life,80

Mach depends, however, on the circumstances under

which members of previously segregated groups first come

in contact with others in unsegregated situations. Avail

able evidence suggests, first, that there is less likelihood

of unfriendly relations when the change is simultaneously

introduced into all units of a social institution to which

it is applicable—e.g., all of the schools in a school system

or all of the shops in a given factory.31 When factories

introduced Negroes in only some shops but not in others

the prejudiced workers tended to classify the desegregated

27 Kenworthy, E. W., The Case Against Army Segregation,

Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,

1951, 275, 27-33; Nelson, Lt. D. D., The Integration of the

Negro in the U. S. Navy, 1951; Stouffer, S., et a!., The American

Soldier, Vol. I, Chap. 19, A Note on Negro Troops in Combat,

1949; Watson, G., Actio-n for Unity, 1947; Opinions About Negro

Infantry Platoons in White Companies in Several Divisions, Infor

mation and Education Division, U. S. War Department, Report No.

B-157, 1945.

28 Brophy, I. N., The Luxury of Anti-Negro Prejudice, Public

Opinion Quarterly, 1946, 9, 456-466 (Integration in Merchant

Marine) ; Watson, G., Action for Unity, 1947.

29 Williams, D. H., The Effects of an Interracial Project Upon

the Attitudes of Negro and White Girls Within the Young Womens

Christian Association, Unpublished M. A. thesis, Columbia Univer

sity, 1934.

30 Dean, J. P., Situational Factors in Intergroup Relations'.

A Research Progress Report. Paper Presented to American Soci

ological Society, 12/28/49 (mimeographed) ; Irish, D. P„ Reactions

of Residents of Boulder, Colorado, to the Introduction of Japanese

Into the Community, / . Social Issues, 1952, 8, 10-17.

81 Minard, R. D., The Pattern of Race Relationships in the

Pocahontas Coal Field, J. Social Issues, 1952, 8, 29-44; Rutledge, E.,

Integration of Racial Minorities in Public Housing Projects; A

Guide for Local Housing Authorities on How to Do It, Public

Housing Administration, New York Field Office (mimeographed).

17

shops as inferior, “ Negro work.’ ’ Such objections were

not raised when complete integration was introduced.

The available evidence also suggests the importance of

consistent and firm enforcement of the new policy by those

in authority.32 It indicates also the importance of such

factors a s : the absence of competition for a limited number

of facilities or benefits;33 34 the possibility of contacts which

permit individuals to learn about one another as indi

viduals;31 and the possibility of equivalence of positions

and functions among all of the participants within the

unsegregated situation.35 These conditions can generally

be satisfied in a number of situations, as in the armed

services, public housing developments, and public schools.

32 Deutsch, M. and Collins, M. E., Interracial Housing, A Psy

chological Study of A Social Experiment, 1951 ; Feldman, H., The

Technique of Introducing Negroes Into the Plant, Personnel, 1942,

19, 461-466; Rutledge, E., Integration of Racial Minorities in

Public Housing Projects; A Guide for Local Housing Authorities

on How to Do It, Public Housing Administration, New York Field

Office (mimeographed) ; Southall, S. E., Industry’s Unfinished

Business, 1951; Watson, G., Action for Unity, 1947.

33 Lee, A. .McClung and Humphrey, N. D., Race Riot, 1943;

Williams, R., Jr., The Reduction of Intergroup Tensions, Social

Science Research Council, New York, 1947; Windner, A. E., White

Attitudes Towards Negro-White Interaction In An Area of Chang

ing Racial Composition. Paper Delivered at the Sixtieth Annual

Meeting of the American Psychological Association, Washington,

September 1952.

34 Wilner, D. M .; Walk ley, R. P .; and Cook, S. W., Intergroup

Contact and Ethnic Attitudes in Public Housing Projects, J. Social

Issues, 1952, 8, 45-69.

35 Allport, G. W., and Kramer, B., Some Roots of Prejudice,

J. Psychol., 1946, 22, 9-39; W'atson, J., Some Social and Psycho

logical Situations Related to Change in Attitude, Human Relations,

1950, 3, 1.

18

IV

The problem with which we have here attempted to deal

is admittedly on the frontiers of scientific knowledge.

Inevitably, there must he some differences of opinion among

us concerning the conclusiveness of certain items of evi

dence, and concerning the particular choice of words and

placement of emphasis in the preceding statement. We

are nonetheless in agreement that this statement is sub

stantially correct and justified by the evidence, and the

differences among us, if any,

and would not materially

elusions.

F loyd H. A llpoet

Gordon W. A llpoet

Charlotte B abcock, M. D.

V iola W. B ernard, M, D.

J erome S. Bruner

H adley Cantril

I sidor Chein

K enneth B. Clark

Mamie P. Clark

Stuart W. Cook

B ingham Dai

A llison Davis

E lse F ren kel-B ru nswi k

Noel P. Gist

D aniel K atz

Otto K linebebg

David K rech

A lfred McCluno Lee

R. M. MacI veb

R obert K. Merton

Gardner Murphy

T heodore M. Newcomb

Robert R edfield

are of a relatively minor order

influence the preceding con-

Syracuse, New York

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Chicago, Illinois

New York, New York

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Princeton, New Jersey

New York, New Y"ork

New York, New York

New York, New York

New York, New York

Durham, North Carolina

Chicago, Illinois

Berkeley, California

Columbia, Missouri

Ann Arbor, Michigan

New York, New York

Berkeley, California

Brooklyn, New York

New York, New York

New York, New York

Topeka, Kansas

Ann Arbor, Michigan

Chicago, Illinois

19

Ira DeA. R eid

A rnold M. R ose

Gerhart Saenger

R. Nevitt Saneord

S. Stanfield Sargent

M. B rewster S mith

Samuel A . Stouffer

W ellman W.arner

R obin M. W illiams

Dated: September 22, 1952.

Haverford, Pennsylvania

Minneapolis, Minnesota

New York, New York

Poughkeepsie, New York

New York, New' York

New York, New York

Cambridge, Massachusetts

New York, New York

Ithaca, New York

20

References

A dorno, T. W .; F renkel-B ru n sw ik , E. L evinson, D. J . ;

Santoro, R. N., The Authoritarian Personality, 1951.

A llport, G. W., and K ramer, B., Some Roots of Prejudice,

J. Psychol., 1946, 22, 9-39.

B auer, C„ Social Questions in Housing and Community

Planning, J. of Social Issues, 1951, VII, 1-34.

Brameld, T., Educational Costs, Discrimination and Na

tional Welfare, Ed. by Maclver, R. M., 1949.

B ren m an , M., The Relationship Between Minority Group

Identification in A Group of Urban Middle Class Negro

Girls, J. Soc. Psychol., 1940, 11, 171-197.

B ren m an , M., Minority Group Membership and Religious,

Psychosexuai and Social Patterns In A Group of Mid

dle-Class Negro Girls, J. Soc. Psychol., 1940, 12, 179-

196.

Bren m an , M., Urban Lower-Class Negro Girls, Psychiatry,

1943, 6, 307-324.

B rooks, J. J., Interage Grouping on Trial, Continuous

Learning, Bulletin #87 of the Association for Child

hood- Education, 1951.

B rophy, I. N., The Luxury of Anti-Negro Prejudice, Public

Opinion Quarterly, 1946, 9, 456-466 (Integration in

Merchant Marine).

C h ein , I., What Are the Psychological Effects of Segrega

tion Under Conditions of Equal Facilities!, Interna

tional J. Opinion & Attitude Res., 1949, 2, 229-234.

Clark , K. B., Effect of Prejudice and Discrimination on

Personality Development, Fact Finding Report Mid-

Century White House Conference on Children and

Youth, Children’s Bureau-Federal Security Agency,

1950 (mimeographed).

21

Clark , K. B. & Clark , M. P., Emotional Factors in Racial

Identification and Preference in Negro Children, J.

Negro Educ., 1950, 19, 341-350.

Clark, K. B. & Clark, M. P., Racial Identification and

Preference in Negro Children, Headings in Social Psy

chology, Ed. by Newcomb & Hartley, 1947.

Conover, R. D., Race Relations at Codormces Village,

Berkeley-Albany, California: A Report of the Attempt

to Break Down the Segregated Pattern On A Directly

Man-aged Housing Project, Housing and Home Finance

Agency, Public Housing Administration, Region I, 1947

(mimeographed).

D avis, A., The Socialization of the American Negro Child

and Adolescent, J. Negro Educ., 1939, 8, 264-275.

D ean , J. P., Situational Factors in Intergroup Relations:

A Research Progress Report, paper presented to

American Sociological Society, Dec. 28, 1949 (mimeo

graphed).

D elano, W ., Grade School Segregation: The Latest Attack

on Racial Discrimination, Yale Law Journal, 1952, 61,

730-744.

D eutschee, M. and C h e in , L, The Psychological Effects o f

Enforced Segregation: A Survey of Social Science

Opinion, J. Psychol., 1948, 26, 259-287.

D eutsch , M. and Collins, M. E., Interracial Housing, A

Psychological Study of A Social Experiment, 1951.

F eldman , H., The Technique of Introducing Negroes Into

the Plant, Personnel, 1942, 19, 461-466.

F razier, E., The Negro In the United States, 1949.

H arding, J., and H ogrefe, R., Attitudes of White Depart

ment Store Employees Toward Negro Co-workers, J.

Social Issues, 1952, 8, 19-28.

22

I rish , D. P., Reactions of Residents of Boulder, Colorado

to the Introduction of Japanese Into the Community,

J. Social Issues, 1952, 8, 10-17.

K en w o rth y , E. W., The Case Against Army Segregation,

Annals of the American Academy of Political and So

cial Science, 1951, 275, 27-33.

K lineberg , O., Characteristics of American Negro, 1945.

K lineberg, 0 ., Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration,

1935.

K lineberg, O., Race Differences, 1936.

K rech , D. & Crutchfield , R. S., Theory and Problems of

Social Psychology, 1948.

L ane, R. H. Teacher in Modern Elementary School, 1941.

L ee, A. M c Clung and H u m ph rey , N. D., Race Riot, 1943.

L ee, A. M cClung , Race Riot Aren’t Necessary, Public

Affairs Pamphlet, 1945.

M erton, R. K .; W est, P. S .; J ahoda, M., Social Fictions

and Social Facts: The dynamics of Race Relations

in EiUtoum, Bureau of Applied Social Research,

Columbia University, 1949 (mimeographed).

M inard, R. D., The Pattern of Race Relationships in the

Pocahontas Coal Field, J. Social Issues, 1952, 8, 29-

44.

M yrdal, G., An American DUemna, 1944.

Newcomb, T., Social Psychology, 1950.

N elson, Lt. 1). D., The Integration of the Negro in the

U. S. Navy, 1951.

R ackow , F., Combatting Discrimination in Employment,

Bulletin #5, N. Y. State School of Industrial and

Labor Relaiions, Cornell Univ., 1951.

23

R adke, M., T rager, II., Davis, H., Social Preceptions and

Attitudes of Children, Genetic Psychol, Monog., 1949,

40, 327-447.

R adke, M., T racer, H., Children’s Perceptions of the Social

Role of Negroes and Whites, J. Physcol., 1950, 29, 3-33.

R eid, Ira., What Segregated Areas Mean, Discrimination

and National W elf are, Ed. by Maclver, R. M., 1949.

R ose, A., The Influence of Legislation on Prejudice,

Chapter 53 in Race Prejudice and Discrimination, Ed.

by Rose, A., 1951.

R ose, A., Studies in Reduction of Prejudice, Amer. Council

on Race Relations, 1948.

R utledge, E., Integration of Racial Minorities in Public

Housing Projects; A guide for Local Housing Au

thorities on How to Do It. Public Housing Administra

tion, New York Field Office (mimeographed).

Saenger, G. and G ilbert, E., Customer Reactions to the

Integration of Negro Sales Personnel, International

Journal of Attitude and Opinion Research, 1950, 4,

1, 57-76.

Saenger, G. & G ordon, N. S., The Influence of Discrimina

tion on Minority Group Members in its Relation to

Attempts to Combat Discrimination, J. Soc. Psychol.,

1950, 31.

Southall, S. E., Industry’s Unfinished Business, 1951.

Stouffer, S. et ah, The American Soldier, Vol. I, Chap. 19,

A Note on Negro Troops in Combat, 1949.

W atson, G., Action for Unity, 1947.

W atson, J., Some Social and Phychological Situations

Related to Change in Attitude, Human Relations, 1950,

3, 1.

24

W eaver, G. L-P., Negro Labor, A National Problem, 1941.

W illiam s, D. H., The Effects of an Interracial Project

Upon the Attitudes of Negro and White Girls Within

the Young Women’s Christian Association, Un

published M. A. thesis, Columbia University, 1934.

W illiam s, R., Jr., The Reduction of Inter group Tensions,

Social Science Research Council, 1947.

W ilnee, D. M., W alkley , R. P .; and Cook, S. W ., Inter

group Contact and Ethnic Attitudes in Public Housing

Projects, J. Social Issues, 1952, 8, 45-69.

W indner, A. E., White Attitudes Towards Negro-White

Interaction in an Area of Changing Racial Composi

tion, Paper delivered at the Sixtieth Annual Meeting

of The American Psychological Association, Washing

ton, September 1952.

Opinions about Negro Infantry Platoons in White Com

panies in Several Divisions, Informtai&n a-nd Educalion

Division, U. S. War Department, Report No. B-157,

1945.

Educational Policies Commission of the National Education

Association and the American Association of School

Administration Report in, Education For All Amer

icans published by the N. E. A. 1948.

COMMEMORATING

THE 60TH ANNIVERSARY

OF

BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION

TDF

DEFEND EDUCATE EMPOWER

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

212.965.2200

www.naacpldf.org

http://www.naacpldf.org