Wright v. Universal Maritime Service Corp. Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

May 7, 1998

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. Universal Maritime Service Corp. Brief for Petitioner, 1998. 26c6ae78-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a75bbb49-cdf1-4184-9886-4ce1b3ac023d/wright-v-universal-maritime-service-corp-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

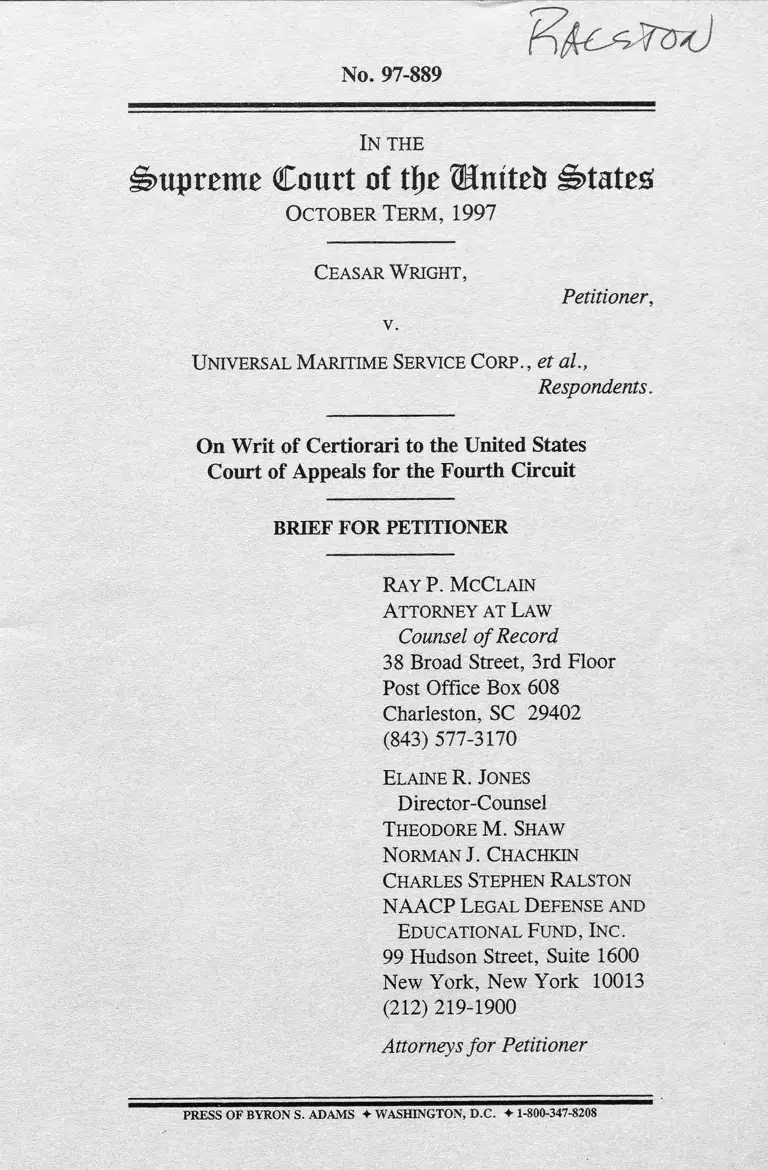

No. 97-889

IN THE

Supreme Court of tf]t ®mteb States?

October Term, 1997

C e a s a r W r ig h t ,

Petitioner,

v.

U n iv e r s a l M a r it im e S e r v ic e C o r p ., et a l ,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

R a y P. M c C l a in

A t t o r n e y a t L a w

Counsel o f Record

38 Broad Street, 3rd Floor

Post Office Box 608

Charleston, SC 29402

(843) 577-3170

E l a in e R . J o n e s

Director-Counsel

T h e o d o r e M . Sh a w

N o r m a n J . C h a c h k in

C h a r l e s S t e p h e n R a l s t o n

NAACP L e g a l D e f e n s e a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys fo r Petitioner

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS ♦ WASHINGTON, D.C. ♦ 1-800-347-8208

QUESTION PRESENTED

Was the court below correct in bolding — contrary to

this Court’s decisions in Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co. and

other cases, particularly Barrentine v. Arkansas-Best Freight

Co., and McDonald v. City o f West Branch, — that a general

arbitration clause in a collective bargaining contract bars an

employee covered by the contract from filing his own lawsuit

under a federal anti-discrimination statute?

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS

The parties are Ceasar Wright, Petitioner, and Universal

Maritime Service Corp., Stevens Shipping & Terminal

Company, Stevedoring Services o f America, Ryan-Walsh, Inc.,

Strachan Shipping Company, Ceres Marine Terminals, Inc., and

South Carolina Stevedores Association, Respondents. None of

the corporate Respondents is a publicly held corporation or a

subsidiary of a publicly held corporation, according to

disclosures filed by Counsel for Respondents in the court below.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Question Presented .............. .............. ........ .................. . i

Parties to the Proceedings................................... .............. u

Table o f Contents ......... .................................................... iii

Table o f Authorities ......... .................... .................. •• iv

Opinions Below .........................................- 1

Jurisdiction ................ .............. ......... ................... ........ 2

Statutory Provisions Involved....................... ................ . 2

Statement of the Case .............................................. . 2

Summary o f Argument...................................................... 10

Argument........................... ....... ................... .................. . 13

I. By statute, tradition, function, and intention,

“grievances” under a labor agreement, including the

agreement here, are limited to disputes about the

application of the collective bargaining

agreement......................... ........................... ............. 17

II. Because the collective bargaining process is designed to

be controlled by the majority, the rights o f victims of

discrimination cannot be waived by a bargaining

representative, and the union here did not intend to

waive those rights........... ...... .......... .................. -....... 22

]V

III. This bargaining agreement, like most labor agreements,

does not provide a mechanism for adequately

vindicating rights under employment discrimination

statutes............................................................................ 30

IV. No statute creates a national policy that a collective

bargaining agreement should supersede the judicial

remedies Congress provided to enforce the

Americans with Disabilities Act and other statutes

prohibiting employment discrimination. ....... 39

Conclusion ............................................... 48

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

CASES:

Adarand Constructors, Inc, v. Pena,

515 U.S. 200 (1995) . . . . . . . . . . . . ___ . . . . . . . . ____ 47

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) . . . 16

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36 (1 9 7 4 ) ........................................ passim

Atchison, T. & S.F.K Co. v. Buell,

480 U.S. 557 (1987) ........................................ ............. 18, 46

Austin v. Owens-Brockway Glass Container,

Inc., 78 F.3d 875 (4th Cir.), cert, denied,

U.S. 117 S.Ct. 432 (1996) . . . . . . . . . . . . . passim

V

Baltimore Regional Joint Board v. Welaster

Clothes, 596 F.2d 95 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 9 ).................................. 34

Barrentine v. Arkansas-Best Freight System,

450 U.S. 728 (1 9 8 1 ) .................... ................... .............passim

Bowen v. U.S. Postal Service, 459 U.S. 212 (1 9 8 3 )......... 37

Boys Markets v. Retail Clerks Union,

398 U.S. 235 (1 9 7 0 ) ............. ................. ............................ 23

Brisentine v. Stone & Webster Engineering Corp.,

117 F.3d 519 (11th Cir. 1997) .................................... 18n, 29

Cole v. Burns Intern. Security Services,

105 F.3d 1465 (D.C. Cir. 1997)........... ................. .. 32, 44

Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189 (1 9 7 4 ) ........... .. 34

Domino Sugar Corp. v. Sugar Workers Local Union 392,

10 F,3d 1064 (4th Cir. 1993) . . . . . ................................. 43n

Electrical Workers v. Foust, 442 U.S. 42 (1979)............ 34

Electrical Workers v. Robbins & Myers, Inc.,

429 U.S. 229 (1 9 7 6 ) ......... ..................... .. 18n, 35

Gilmer v. Interstate/Johmon Lane Corp.,

500 U.S. 20 (1 9 9 1 ) ......... ..................................... .. passim

Goodman v. Lukens Steel, 482 U.S. 656 (1987) . . 24, 26, 27

Graham Oil Co. v. ARCO Products,

43 F.3d 1244 (9th Cir. 1995) ................ .. 32

V]

Harrison v. Eddy Potash, Inc., 112 F.3d 1437

(10th CirX p e t. fo r cert, filed, 66 U.S.L.W. 3137

(Aug. 6, 1997)..................................................................... 18n

Hawaiian Airlines, Inc. v. Norris,

512 U.S. 2 4 6 (1 9 9 4 )......... ............................................ 18,46

Hetzel v. Prince William County, Virginia,

U .S .___ , 118 S.Ct. 1210(1998) .................. 39 ,42 ,48

International Union v. Murata Erie North America,

980 F.2d 889 (3d Cir. 1992) ................ ................... . . . . . 5n

Lingle v. Norge Division o f Magic Chef,

486 U.S. 3 9 9 (1 9 8 8 )............................... ...................... 21,46

Livadas v. Bradshaw,

512 U.S. 107 (1 9 9 4 ) ............................. 14, 21, 22, 29, 45, 46

Local 1422, ILA, AFL-CIO v. S.C. Stevedores

Association, etal., C.A. No. 2:97-2886-21

(D.S.C. filed Sept. 22, 1997), on appeal

No. 98-1296 ................................................... ................. .. . 9n

Local No. 391 v. Terry, 494 U.S. 558 (1990) . 16, 34, 36, 48

Mastrobuono v. Shear son Lehman Hutton, Inc.,

514 U.S. 52(1995) .................................... ............... 33

McDonald v. City o f West Branch,

466 U S. 284 (1 9 8 4 ) ................................. .......... . . . . passim

McKinney v. Missouri-Kansas-Texas R Co.,

357 U.S. 265 (1958) .................................. .......................... 19

Mitsubishi Motors Corp. v. Solar Chrysler-Plymouth,

Inc., 473 U.S. 614 (1985) .................... 14, 19, 30, 31, 32, 49

Montes v. Shearson Lehman Brothers, Inc. ,

128 F.3d 1456 (11th Cir. 1 9 9 7 ).................... ................... 36n

Nelson v. Cyprus Baghdad Copper Co., 119

F.3d 756 (9th Cir. 1997), cert, denied, ___

U .S .___, 66 U.S.L.W. 3686 (April 20, 1998) . . 32, 42n, 48n

NLRB v. Magnavox Company, 415 U.S. 322 (1974) . 25,48

Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc.,

U .S .___ , 118 S. Ct. 998 (1 9 9 8 )............................... .. 27

Perry v. Thomas, 482 U.S. 483 (1987) ......................... 45

Prudential Insurance Co. o f America v. Lai,

42 F.3d 1299 (9th Cir. 1994) . .......................................... 48n

Pryner v. Tractor Supply Co., 109 F.3d 354

(7th Cir.), cert, denied,___U .S .___ ,

118 S. Ct. 294 (1997) ...................... .. 28, 42n, 44

Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shear son/American

Express, Inc., 490 U.S. 477 (1 9 8 9 ) ......... .. 14

Shearson/American Express Inc. v. McMahon,

482 U.S. 220 (1987) ........................................ .. 14, 35

Sine v. Local No. 992, Intern. Broth,

644 F.2d 997 (4th Cir. 1981) ......................... ................. .. 43n

Steele v. Louisville&N.R.. Co., 323 U.S. 192 (1944) . . . 23

Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln Mills,

353 U.S. 448 (1 9 5 7 ) ........................................ ................... 23

Tran v. Tran, 54 F.3d 115 (2d Cir. 1995) . . . . . . . . . . . 18n

U.S. Bulk Carriers v. Argue lies,

400 U.S. 351 (1 9 7 1 ) ............. ..................................... 18n, 44

United Electrical, etc., Workers v. Miller Metal Products,

215 F.2d 221 (4th Cir. 1954)............................................. 43n

UnitedPaperworkers Intern. Union v. Misco, Inc.,

484 U.S. 2 9 (1 9 8 7 ) ........................................ .. 18

United Steelworkers v. Warrior &

G ulf Navigation Co., 363 U.S. 574 (1960) ......... .. 16,19

Vaca v. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171 (1 9 6 7 )........... .. 16, 37, 38

Varner v. National Super Markets, Inc.,

94 F.3d 1209 (8th Cir. 1996), cert, denied,

___U .S .___ , 117 S.Ct. 946 (1997) ............................... 18n

Wright v. Universal Maritime Service Corp.,

121 F.3d 702 (July 29, 1997)............................. ............. 1, 40

Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, 455 U.S. 385 (1982) . . . . 32

STATUTES:

9 U.S.C. §§ 1 et seq. ................................ 14

9 U.S.C. § 1 ................................................... .. 43

viii

IX

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ...............................................................

29 U.S.C. §§ 151, etseq. . . .................................................

29 U.S.C. §§ 171, etseq .................... ...................................

29 U.S.C. § 173(d) ............................................... 2,

29 U.S.C. § 185 . . ......................... ................................... 2,

29 U.S.C. § 206(d) ............................................... ..

29 U.S.C. § 623(c) ...................... ........................................

42 U.S.C. § 1981a(c)............................................................

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ........... .. ....................................................

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(c)............................... .......................

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(e) ........................... ............................

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f) ...................................... 2, 32, 34,

42 U.S.C. §§ 12101 etseq. . . . ___ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42 U.S.C. § 12101 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42 U.S.C. § 12102(2) ........................................................

42 U.S.C. § 12111(2) .................... ..

42 U.S.C. § 12112(b) ......................... ..............................

42 U.S.C. § 12117 .............................................. 2, 32, 34,

2

15

15

17

44

13

26

39

14

34

32

39

2

24

8

26

8

39

X

42 U.S.C. § 12212 ................................................. 2 ,8 ,4 0 ,4 1

46U.S.C. § 596 ............................................................ 18n, 44

46 U.S.C. § 597. . .................. .......................... .. 44

The Civil Rights Act of 1991, § 118, codified

at 42 U.S.C. § 1981 note ............................................... 40, 41

OTHER:

H R . Conf. Rep. No. 596, 101st Cong., 2d Sess.

(1990) , reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. 565 . . . . . . . . . . 42

H R . Rep. No. 40(1), 102d Cong., 1st Sess.,

(1991) , reprinted in 1991 U.S.C.C.A.N. 549 . . . . . . . . . . 43

H R . Rep. No. 485, 101st Cong., 2d Sess.

(1990) . . . . . ----- . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ____ 42-43

NLRB Memorandum on Collective Bargaining

and ADA (Sept. 1992), reprinted in ADA

MAN. (BNA) 70:1021 . ....................... .. 27

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1997

No. 97- 889

CEASAR WRIGHT,

Petitioner,

v.

UNIVERSAL MARITIME SERVICE CORP.. et. al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

OPINIONS BELOW

The Opinion o f the United States Court o f Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit is unreported. It is referenced in a Table at

121 F.3d 702 (July 29, 1997), and is reprinted at Petition for

Certiorari, Appendix (‘Pet. App.”) la.

The Order o f the United States District Court for the

District o f South Carolina, dated September 25, 1996, is

unreported, and is reprinted at Pet. App. 6a. That Order

adopted the ruling recommended by a Magistrate Judge in a

Report dated June 14, 1996, reprinted at Pet. App. 19a. The

further Order of the District Court, dated December 5, 1996, is

reprinted at Pet. App. 14a.

1

2

The decision o f the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit in Austin v. Owens-Brockway Glass

Container, Inc., 78 F.3d 875 (4th Cir.), cert, denied,___ U.S.

___ , 117 S. Ct. 432 (1996), on which the courts below relied

without discussion, is reprinted, for convenient reference, at Pet.

App. 34a.

JURISDICTION

Jurisdiction is conferred by 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This matter involves the enforcement o f the Ameri cans

with Disabilities Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 12101 et seq. The pertinent

portions of the Act, particularly 42 U.S.C. §§ 12117 (adopting

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)), 12212, are printed at Pet. App. 27a.

This matter also involves 29 U.S.C. §§ 173(d) and 185.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Petitioner’s Employment History

Petitioner was regularly employed as a longshoreman in

the Port of Charleston, beginning in 1970, through the hiring hall

operated by Local 1422, International Longshoreman’s

Association, AFL-CIO (ILA). His taxable income from this

employment exceeded $82,000 in 1991. Joint Appendix (“JA”)

5 la f 9. In early 1992, while working for respondent Stevens

Shipping, petitioner fell off the top of a freight container,

shattering his right heel and injuring his back. These injuries

disabled him from waterfront employment for an extended

period. His treating physician thought petitioner would probably

be permanently and totally disabled from longshore employment,

while other physicians expressed the opinion that petitioner

3

could return to waterfront work. JA 50a. In May, 1994,

petitioner settled his workers’ compensation and other claims,

including claims for permanent and total disability, for $250,000.

JA 52a.

A major factor in petitioner’s physical disability was a

bony spike in his right heel that made walking extremely painful.

In late 1994 the bony spike spontaneously resorbed. Petitioner’s

physician documented this improvement and found that

petitioner was physically able to return to work. JA 53a.

In January, 1995, after almost three years off the job,

petitioner returned to the hiring hall to seek assignments for

work. On nine o f the ten days from January 2 through January

11, 1995, petitioner was referred for employment by Local

1422, TLA, and worked for four of the respondent employers

during those nine days. Each of these respondents accepted

petitioner as qualified for his position, and none had any

complaints about his work performance. Pet. App. at 21a; JA

54a f 18. Some of these respondents asked for written approval

from petitioner’s treating physician for petitioner to return to

work, and this was provided. JA 53 a.

On January 11, 1995, the respondent employers agreed

among themselves that they would all refuse to accept petitioner

for work. In virtually identical letters to the president of Local

1422, TLA, the respondents stated that petitioner was previously

“certified as permanently and totally disabled.” They continued

that “once an individual is certified as permanently and totally

disabled, he is no longer qualified to perform longshore work of

any kind.” JA at 35a.

Petitioner immediately consulted with Benjamin Flowers,

the president of Local 1422, ILA, his bargaining representative.

As the District Court found, “Both parties agree that Plaintiff

initially followed the proper procedure under the collective

bargaining agreement for filling a grievance against Defendant.”

Pet. App. 16a. President Flowers wrote to the respondents to

4

protest that the refusal to accept petitioner for work was a

violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act and a “lockout”

violating the bargaining agreement. (The agreement lacked a

‘Nondiscrimination” clause.) The union president did not pursue

a grievance for petitioner under the agreement; instead, he

advised petitioner to retain private counsel to pursue a statutory

claim under the Americans with Disabilities Act. By the time

petitioner located counsel, just two weeks later, a grievance

under the Bargaining Agreement was “out o f time.” JA 55a.

Petitioner promptly invoked his statutory rights by filing

timely charges of discrimination with the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission (EEOC) against all respondents. After

the EEOC issued a Notice o f Right to Sue on each charge,

petitioner filed this action in January, 1996.

Two months later, the United States Corn! o f Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit issued its opinion in the case o f Austin v.

Owens-Brockway Glass Container, Inc., 78 F„3d 875 (4th Cir.

March 12, 1996), cert, denied,___U.S. ___, 117 S. Ct. 432

(1996), which held that an applicable labor arbitration agreement

“ousts a court o f jurisdiction” to hear statutory claims of

discrimination brought by individual employees. Petitioner then

offered to arbitrate, but respondents refused. JA 58a.

B. The Collective Bargaining Agreement

The bargaining agreement in this case was adopted

effective November 30, 1990. It was negotiated between the

respondents and the South Atlantic & Gulf Coast District o f the

International Longshoremen’s Association to cover ‘longshore

work” in the Port o f Charleston, a term that covered “all labor

used in connection with loading or discharging ships, barges or

other floating craft.” JA 36a.1

1 In addition to a detailed definition of the scope of “longshore

work,” JA 36a-37a, the agreement addressed job classifications, wage rates,

vacation and holiday pay, shift differentials, minimum hours of work after the

5

The grievance and arbitration provisions were stated in

Clause 15.(b) of the Agreement. That Clause did not define

“grievances,” except as “Matters under dispute which cannot be

promptly settled between the Local and an individual

Employer.” JA43a. Clause 15. (F) of the Agreement [known

as a “zipper clause”] stated that the Agreement represented

closure o f negotiations, JA 45a - 46a:2

The Union agrees that this Agreement is intended to

cover all matters affecting wages, hours, and other

terms and conditions of employment and that during the

term of this Agreement the Employers will not be

required to negotiate on any further matters affecting

these or other subjects not specifically set forth in this

Agreement. Anything not contained in this Agreement

shall not be construed as being part o f this Agreement.

day shift, special supplementary funds (container royalty and Guaranteed

Annual Income), pension and welfare Funds (see Defendants’ Motion for

Summary Judgment, Exhibit B, Attachment 1); the commitment of the parties

to adopt safe and efficient methods for stevedoring operations, JA 37a; the

Employer’s rights in hiring and discharging workers and assigning workers

subject to various limitations, such as the “minimum gang structure” “required

as determined by the class of cargo being handled by the gang,” detailed

matters not defined within the four comers of the collective bargaining

agreement, JA 38a; misconduct and punishment for various offenses, JA 39a-

42a; a prohibition on lockouts by the Employers and on work stoppages by the

union, JA 42a-43a; collection of delinquent Employer contributions to pension

and welfare funds, JA 43 a; a grievance procedure, JA 43a-45a; and safety

rules for various classes of cargo operations, including conditions

disqualifying a worker from employment (intoxication and epilepsy). JA 46a-

47a.

2 A “zipper clause” defines, not the scope of arbitration, but the

scope of the employers’ exemption from participating in “mandatory

bargaining” during the life of the collective bargaining agreement.”

International Union v. Murata Erie North America, 980 F.2d 889, 903 (3d

Cir. 1992).

6

All past port practices being observed may be reduced

to writing in each port.

The Agreement also provided in Clause 15(E): “All

interpretations of this Agreement will be made in accordance

with the provisions of Clause 15.” JA45a. As to construction

o f the Agreement, the parties also adopted a “savings clause,”

Clause 17, that states: “It is the intention and purpose of all

parties hereto that no provision or part of this Agreement shall

be violative o f any Federal or State Law.” JA 47a.

Although the bargaining agreement covered many topics,

it did not include a Nondiscrimination” clause: the agreement

includes no express provisions whatever prohibiting

discrimination by the Employers on the basis o f race, gender,

age, nationality, or disability. The Agreement makes no

reference whatsoever to the Americans with Disabilities Act, nor

to any other employment discrimination law. JA 55a f 21. The

only specific statute to which the Agreement refers is the

Occupational Safety and Health Act. JA 46a.

In the Port of Charleston, there are three local unions

(ILA affiliates with distinct work jurisdictions) and a number of

other Employers who contract with one or more o f these locals.

When Local 1422, ILA, and an individual Employer have a

“matter under dispute,” the Agreement contemplates that they

will have “such discussion” as may “promptly settle” the

dispute.3 If the parties cannot achieve a resolution, the “Matters

under dispute . . . shall, no later than 48 hours after such

3 The Agreement mentions explicitly several types of issues that will

be referred to the Port Grievance Committee if the parties cannot resolve them.

These include (1) safe and efficient methods of operation, JA 37a-38a; (2) a

claim of “hardship . . . because of unreasonable or burdensome conditions.”

JA 38a; (3) “where work methods or operations materially change in the

future,” id.; (4) “misconduct charges” against individual workers, JA 42a; and

(5) contributions allegedly delinquent to pension and welfare funds (referred

directly to District Grievance Committee). JA 42a.

7

discussion, be referred in writing covering the entire grievance

to a Port Grievance Committee” consisting o f two

representatives o f Management and two representatives of the

union. The grievance may be settled at the Port level. JA 43 a-

44a.

Only if “this Port Grievance Committee cannot reach an

agreement within five days after receipt o f the complaint” can

the matter “be referred to the Joint Negotiating Committee,

which will function as a District Grievance Committee . . . JA

44a. The Joint Negotiating Committee has five members from

Management and five members from the Union. JA 45 a. When

sitting as the District Grievance Committee, the meeting must be

attended by at least three (3) regular Employer members and

three (3) regular Union members and each side has four votes.

JA 44a.

The Agreement further provides, JA 44a-45a:

A majority decision o f this [District Grievance]

Committee shall be final and binding on both parties and

on all employers signing this Agreement. In the event

the Committee is unable to reach a majority decision

within 72 hours after meeting to discuss the case, it shall

employ a professional arbitrator. . . .

In the selection o f an arbitrator, thought will be

given to a person who is knowledgeable and familiar

with the problems of the Longshore industry.

Any decision in favor of the employee involving

monetary aspects of discharge shall require the employer

involved to make financial restitution from the time of

the complaint concerned, whereas decisions involving

working methods or interpretations shall take effect

seventy-two hours after being rendered.

8

C. Claim under the Americans With Disabilities Act

The petitioner’s union received virtually identical letters

from four stevedoring companies, all stating, "Once an

individual is certified as permanently and totally disabled, he is

no longer qualified to perform longshore work o f any kind." JA

35a. This statement, petitioner believes, was an unusually clear

violation o f the Americans with Disabilities Act.

A major purpose of the ADA is to ensure that

employment decisions are based on an individualized

determination of a person’s actual abilities and limitations. The

Act protects “individuals with a disability,” and defines a

disability as: “(1) A physical or mental impairment that

substantially limits one or more o f the major life activities of

such individual; (2) a record of such an impairment; or (3) being

regarded as having such an impairment.” 42U.S.C. § 12102(2).

Among the ADA’s specific prohibitions are: (a)

‘limiting . . . or classifying a job applicant or employee in a way

that adversely affects . . . opportunities,” and (b) “utilizing

standards or criteria that have the effect o f discrimination on the

basis o f disability. . . .” 42 U.S.C. §§ 12112(b)(1), (b)(3)(A).

Respondents’ letters constitute an admission that petitioner was

being permanently barred from his occupation because he was

regarded as being permanently and totally disabled.” They also

evidenced discrimination based on a “record” o f disability,

utilizing both an impermissible “limitation or classification” and

“standards or criteria” that screen out people with disabilities.

9

D. Proceedings Below

On cross motions for summary judgment, a Magistrate

Judge recommended that petitioner’s suit “be dismissed without

prejudice for want of jurisdiction,” on the authority o f Austin.

Pet. App. at 26a. The District Judge agreed in an Opinion dated

September 25, 1996. He later denied a timely Motion for

Reconsideration by Order dated December 5, 1996.4

Since the employers had already refused to arbitrate the

claims, the dismissal o f the suit without either compelling

arbitration or retaining jurisdiction ended the statutory claims.

The result is that petitioner has been permanently excluded from

his career occupation without having a hearing in any forum on

the merits of his ADA claims.

Petitioner prosecuted a timely appeal to the Court of

Appeals. That Court affirmed the judgment on July 29, 1997,

holding that Wright’s only recourse was a union-sponsored

grievance, and that he had no right to sue under the ADA. The

Court referred to the arbitration clause, but quoted instead from

the “zipper clause,” 15(F):

The arbitration clause at issue is particularly broad. The

clause states that the “Union agrees that this Agreement

is intended to cover all matters affecting wages, hours,

and other terms and conditions of employment.”

Pet. App. 4a. After confusing the zipper clause with the

4 In July, 1996, after the decision in Austin v. Owens-Brockway

Glass Container, the union hiring hall again referred petitioner for work.

Petitioner was again refused work. This time the union pursued a grievance.

Respondents refused to process the grievance. The union filed suit to compel

arbitration. Local 1422, ILA, AFL-CIO v. S.C. Stevedores Association, et al.,

C.A. No. 2:97-2886-21 (D.S.C. filed Sept. 22, 1997). Because the union’s

suit was not filed within six months of January 11, 1995, when the petitioner

was first refused work, the suit has been dismissed as untimely. The union has

appealed to the Fourth Circuit, Docket No. 98-1296.

10

arbitration clause, the Court continued,

An employer need not provide a laundry list o f potential

disputes in order for them to be covered by an

arbitration clause. For example, in Gilmer v.

Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991), the

Supreme Court held that a plaintiff was required to

submit his ADEA claim to arbitration where the

arbitration agreement covered “any dispute, claim or

controversy.” Id. at 23. The language of the CBA at

issue in this case is equally broad, covering “all matters”

regarding “terms and conditions o f employment.” This

language easily encompasses Wright's ADA claim

A timely petition for certiorari was granted on March 2,

1998.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Americans with Disabilities Act is one o f many

Congressional enactments that guarantee minimum substantive

rights to all individual workers covered by each statute. In

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974), this

Court held that these substantive statutory rights were

independent o f labor agreements and found that these rights

could be enforced judicially, either in addition to or instead of

contract remedies.

For organized workers only, Congress created a parallel

statutory regime promoting and regulating the exercise of

collective economic rights, including the “core” collective right,

the right to strike. Two statutes regulate collective activity.

The NLRA created the National Labor Relations Board as an

independent federal agency to oversee labor organizing and

collective bargaining. The LMRA created a system of

“industrial self-government” in which unions exchanged the right

to strike, when disputes arose, for the right to have an

independent private tribunal make a final and binding resolution

11

of disputes about the “interpretation or application” o f the labor

agreement.

Statutes conferring individual rights emphasize “make

whole” relief for the individual worker, whether or not he is

covered by any labor agreement. Under the NLRA and the

LMRA, statutes conferring collective rights, remedies are

available for individuals, but are subordinated to the purposes of

“national labor policy,” with the primary objective of promoting

industrial peace.

The LMRA established the binding authority of the

grievance-arbitration mechanism for resolving disputes about the

application or interpretation of labor agreements. The Railway

Labor Act did the same for railroads and airlines. Those

mechanisms were not created to resolve disputes involving the

“minimum substantive rights” guaranteed to workers by

employment discrimination statutes, and parties to labor

agreements do not generally intend to use the grievance

mechanism for that purpose, except where they explicitly agree

otherwise. In particular, most unions, like the union

representing petitioner, do not wish to undertake the conflicting

interests inherent in being a “gatekeeper” for the statutory rights

of individuals under employment discrimination statutes.

Logically, the enforcement of statutory rights by

individuals who seek personal “make whole” relief should be

controlled by those individuals. In contrast, access to remedies

for workers under the NLRA is controlled by the General

Counsel o f the NLRB, through his discretionary authority to

issue unfair labor practice complaints. Access to remedies for

workers under “industrial self-government” is controlled by

unions, as the official representatives o f the collective economic

power o f those workers. In this context, only the control of

enforcement of statutory rights by the injured worker is properly

analogous to commercial arbitration.

12

In the securities industry’s arbitration regime, the

Securities and Exchange Commission enforces standards for

arbitration, and no employee risks forfeiting rights because of

any special procedural rules o f that regime. In Gilmer v.

Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20 (1991), this Court

held that, on the record there presented, the industry

arrangements were adequate to assure effective vindication o f

statutory rights to be free o f age discrimination.

In stark contrast, if statutory claims are subject to “final

and binding” resolution under labor grievance procedures, union

control o f the grievance mechanism and the technical rules of

that mechanism can easily combine, as in this case, to prevent

strong claims from ever receiving a hearing on the merits. Both

union control and extremely short periods for filing claims are

well suited as an extension of collective bargaining to adjust

contract disputes. To transform those grievance mechanisms to

protect statutoiy rights, such as by recognizing the statutes of

limitations enacted by Congress, would undermine the

effectiveness o f the grievance mechanism as part o f the

continuing process o f bargaining.

Congress has never authorized unions to waive any

individual “minimum substantive rights” — including the right to

a judicial forum — under any employment discrimination statute:

in enacting the ADA, Congress explicitly endorsed Alexander;

the Federal Arbitration Act does not apply to this agreement;

and this Court has repeatedly rejected arguments that Section

301 of the LMRA requires arbitration o f claims under federal

statutes.

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver controls this case. Since

remedies under labor agreements are primarily intended to

further national labor policy, the grievance-arbitration

procedures for enforcing those remedies are very different from

commercial arbitration and give individual workers much less

opportunity to enforce statutory rights than is provided in

13

commercial arbitration. Gilmer and the cases it applied have no

relevance to labor grievance mechanisms. The decision of the

court of appeals should be reversed and the case remanded for

petitioner to proceed on the merits of his claim under the ADA.

ARGUMENT

Introduction

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974),

established a “bright-line” rule: a mandatory arbitration clause

in a labor agreement does not bar an employee’s access to the

courts to prosecute a claim based on a federal statute because,

inter alia, the union, rather than any individual employee,

controls the exercise o f the grievance-arbitration procedure

under a collective bargaining agreement and any individual’s

“waiver” of the judicial forum would have to be ‘Voluntary and

knowing.” The principles of Alexander were amplified in

Barrentine v. Arkansas-Best Freight System, 450 U.S. 728

(1981), which held that wage and hour claims under the Fair

Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. § 206(d), were not precluded

by a decision o f a joint labor-management dispute board, and

that other workers who did not file grievances could go directly

to federal court. This Court also applied these principles in

McDonald v. City o f West Branch, 466 U.S. 284 (1984), which

held that a First Amendment claim brought in federal court

under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 was not barred by an unfavorable

decision in an arbitration o f a grievance filed under a bargaining

agreement.

In Alexander, even as this Court emphasized the

importance of the right o f ultimate resort to the judicial forum

to address statutory claims, the Court also endorsed the use of

contractual procedures to resolve disputes through application

of the bargaining agreement, 415 U.S. at 55:

. . . the grievance-arbitration machinery of the collective

bargaining agreement remains a relatively inexpensive

14

and expeditious means for resolving a wide range of

disputes, including claims of discriminatory employment

practices. Where the collective-bargaining agreement

contains a nondiscrimination clause similar to Title VH,

and where arbitral procedures are fair and regular,

arbitration may well produce a settlement satisfactory to

both employer and employee, . . . eliminat[ing] those

misunderstandings or discriminatory practices that might

otherwise precipitate resort to the judicial forum.

After McDonald, this Court decided that statutory

claims were presumed to be within the scope of predispute

agreements for mandatory arbitration in commercial and

securities agreements, and were to be enforced under the

Federal Arbitration Act, 9 U.S.C. §§ 1 et seq, Mitsubishi

Motors Corp. v. Solar Chrysler-Plymouth, Inc., 473 U.S. 614

(1985); Shearson/American Express Inc. v. McMahon, 482 U.S.

220 (1987); Rodriguez de Quijas v. Shear son/American

Express, Inc., 490 U.S. 477 (1989) (the “Mitsubishi Trilogy”).

Then in Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500

U.S. 20 (1991), this Court applied the Mitsubishi Trilogy and

the Federal Arbitration Act to require arbitration o f a claim

under the Age Discrimination in Employment Act where a

registration statement executed by a securities broker required

arbitration o f disputes. The Court carefully distinguished that

individual agreement, which left the individual employee with

control o f the prosecution of his claims before the arbitrator,

from the collective bargaining context, where the arbitrator’s

authority was usually limited and the union (not the aggrieved

employee) controlled the presentation o f the claim Three years

later, in Livadas v. Bradshaw, 512 U.S. 107, 127 n.21 (1994),

this Court reaffirmed the principle that workers’ statutory rights

were not to be waived for them by a union contract.

The unique policy considerations governing labor

arbitration clauses have been recognized by every federal court

15

of appeals to address the issue since Gilmer, with the exception

of the court below.5 These policy concerns arise from the three

parallel, sometimes overlapping regimes created by Congress

to regulate employee-employer relationships in the organized

shop. First, in the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act)

(1935), 29 U.S.C. §§ 151, et seq., Congress authorized labor

organizations that obtained majority worker support to be the

exclusive bargaining representative in a workplace and

established an independent agency, the National Labor Relations

Board, to adjudicate disputes about the union’s exercise of

collective economic rights and the employer’s opposition to

union influence. Second, in Titles II and HI o f the Labor

Management Relations Act (Taft-Hartley Act) (1947), 29

U.S.C. §§ 171, et seq., Congress endorsed an exclusive system

of “industrial self-government,” in which disputes between the

parties about the application o f the bargaining agreement

(“grievances”) would be resolved by the parties or by a private

umpire -- an arbitrator, a joint labor-management council — with

virtually no court review of the umpire’s decisions. Third, in a

wide variety o f statutes addressing the rights of workers,

including pay and freedom from discrimination, Congress

provided ‘‘minimum substantive guarantees to individual

workers.” Barrentine v. Arkansas-Best Freight System, 450

U.S. 728, 737 (1981).

These parallel regimes had very different purposes. The

two labor relations statutes were designed to regularize and

legitimize the exercise o f the collective economic power of

workers (NLRA) and to establish labor peace by creating an

institutional mechanism to resolve disputes about collective

rights under the bargaining agreement (“grievances”) without

the continual disruption of strikes or other job actions (LMRA).

Although remedies for individual workers were created in both

these regimes, these remedies were strictly circumscribed. The

5 See cases cited, Petition for Certiorari at 10.

16

General Counsel for the NLRB has virtually unreviewable

discretion as to whether to issue a complaint on an unfair labor

practice charge. Vacav. Sipes, 386 U.S. 171, 182 (1967). Both

collective regimes were primarily directed at the implementation

o f collective rights and “national labor policy,” not at the

protection o f the rights of individual workers. See, e.g., Local

391 v. Terry, 494 U.S. 558, 573 (1990) (NLRA “concerned

primarily with the public interest in effecting federal labor

policy”); United Steelworkers v. Warrior & G ulf Navigation

Co., 363 U.S. 574, 578 (1960) (“A major factor in achieving

industrial peace is the inclusion of a provision for arbitration of

grievances in the collective bargaining agreement.”); and Vaca

v. Sipes, 386 U.S. at 191 (LMRA contemplates union will

supervise the grievance process and “settle grievances short of

arbitration.”).

On the other hand, federal statutes that guaranteed rights

both to organized workers and to individual, unrepresented

employees, were intended by Congress to “provide minimum

substantive guarantees to all employees.” The courts’ remedial

powers under these statutes, such as Title VII, were designed to

provide “make whole” relief to the individual worker.

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975).

These rights are personal, and have never been considered to be

within the authority o f the labor organization. Based on the

individual character o f statutory protections against

discrimination and based on the strong Congressional policy

against union waivers o f rights o f the workers they represent,

Alexander should be reaffirmed. All three distinctions this Court

noted in Gilmer support this result: (1) the union and

management did not agree to grieve statutory claims; (2) due to

majoritarian control, the union should not have authority to

waive or compromise personal statutory rights; and (3) no

statute authorizes a union-management agreement to abrogate

personal judicial remedies. In addition, the grievance mechanism

17

here, as in most labor agreements, is not suited for effective

vindication of personal statutory rights.

I. By statute, tradition, function, and intention,

“grievances” under a labor agreement, including the

agreement here, are limited to disputes about the

application of the collective bargaining agreement.

Petitioner’s representative did not intend that the

bargaining agreement would be used to process statutory claims.

Benjamin Flowers, the president o f Local 1422 who wrote

letters o f protest to the employers and advised petitioner to

retain an attorney to sue under the ADA, was the union

representative who had signed the bargaining agreement. JA

47a; Plaintiff’s Motion to Compel Arbitration, Exhibits 2, 3, 4.

The agreement has never been applied to a statutory

discrimination claim. Statement o f respondents’ counsel,

Transcript o f Hearing on Motion for Summary Judgment, May

22, 1996, page 51, line 13.

In Gilmer, 500 U.S. at 35, this Court correctly observed

that the controversy was completely different from the

Alexander line of cases, “since the employees there had not

agreed to arbitrate their statutory claims and the labor arbitrators

were not authorized to resolve such claims. . . . ” This limitation

is often expressly stated in bargaining agreements, but it derives

from the Congressional declaration that the function o f the

grievance-arbitration process is to apply the bargaining

agreement.

The generic meaning o f “grievance” as limited to the

application o f the bargaining agreement was enacted in 1947 in

Section 203(d) of the Labor Management Relations Act, 29

U.S.C. § 173(d):

Final adjustment by a method agreed upon by the parties

is hereby declared to be the desirable method for

settlement o f grievance disputes arising over the

18

application or interpretation o f an existing collective

bargaining agreement. . . . [Emphasis added.]

As this Court observed in United Paperworkers Intern. Union

v. Misco, Inc., 484 U.S. 29, 36 (1987):

Collective-bargaining agreements commonly

provide grievance procedures to settle disputes between

union and employer with respect to the interpretation

and application o f the agreement and require binding

arbitration for unsettled grievances.

This understanding of “grievances” is also congruent

with parallel labor statutes. This Court has held that

“grievances,” as used in the Railway Labor Act, is “a synonym

for disputes involving the application or interpretation o f a

CBA.” Hawaiian Airlines, Inc. v. Norris, 512 U.S. 246, 255

(1994) (state law “whistleblower” claim not subject to the

statutory grievance procedure for “minor disputes” and National

Adjustment Board). Before Norris, this Court had unanimously

held that claims under federal statutes are not subject to the

statutory grievance procedure for “minor disputes” and the

Adjustment Board. Atchison, T. & S.F.R Co. v. Buell, 480

U.S. 557 (1987) (FELA).6

6 As noted infra , pp. 47-48, the statutory procedure is completely

independent of the contract mechanism. This Court has never required

“exhaustion” of contract dispute procedures before presenting a statutory

claim, either under the Railway Labor Act, see Buell, or under Section 301.

See U.S. Bulk Carriers v. Arguelles, 400 U.S. 351,357 (1971) (grievance not

prerequisite to seaman’s statutory wage and penalty claim under 46 U.S.C. §

596); McKinney v. Missouri-Kansas-Texas R. Co. 357 U.S. 265, 268-70

(1958) (contract grievance not prerequisite to suit asserting seniority rights

under Universal Military Training and Service Act). In most of the appellate

cases that have rejected Austin, no grievance was filed. See cases cited, Pet.

at 10 (Varner,Harrison, Brisentine, Tran). Alexander and subsequent cases

make clear there is no “exhaustion” requirement. See 415 U.S. at 47 and

Electrical Workers v. Robbins &Myers, Inc., 429 U.S. 229 (1976) (grievance

does not “toll” the statutory time for filing a claim under Title VII).

19

Because of this consistent interpretation by Congress and

this Court of the term “grievance” in the grievan ce-arbitration

mechanism, the labor grievance process is completely different

from the sophisticated commercial arbitration mechanism

described in Mitsubishi Motors Corp. v. Soler Chrysler-

Plymouth, Inc., 473 U.S. 614, 634 n.18, 638 n.2G (1985), and

it is substantially different from commercial arbitration in the

securities industry, the arbitral regime this Court applied to Mr.

Gilmer’s claim under the ADEA. The wide gulf between labor

arbitration and commercial arbitration was described in the

Steelworkers Trilogy, United Steelworkers v. Warrior & G ulf

Nav. Co., 363 U.S. 574, 578, 580-81 (1960):

In the commercial case, arbitration is the substitute for

litigation. Here arbitration is the substitute for industrial

strife. . . . For arbitration o f labor disputes under

collective bargaining agreements is part and parcel o f the

collective bargaining process itself.

% 5f: 5je

Courts and arbitration in the context of most commercial

contracts are resorted to because there has been a

breakdown in the working relationship of the parties;

such resort is the unwanted exception. But the

grievance machinery under a collective bargaining

agreement is at the very heart of the system of industrial

self-government. Arbitration is the means of solving the

unforeseeable by molding a system of private law for all

the problems which may arise and to provide for their

20

solution in a way which will generally accord with the

variant needs and desires o f the parties.7

It is crucial to remember that the parties to the labor

grievance are the District Union, the Employers’ Association,

and the individual employees). JA 36a, 47a. The individual

workers are not parties.8 Individuals on either the labor side or

the management side can request that a “matter in dispute”

about the application o f the agreement be submitted to the

grievance process, but, for a worker, only the union can formally

7 Because the written agreement here has apparently evolved by

accretion over many years, it is a collection of provisions that are applied year

in and year out by permanent industry committees. The first step in the

grievance process is a “Port Grievance Committee”; the union representatives

come from several distinct local labor organizations in the Port (ILA locals

with distinct work jurisdictions). If the “matter under dispute” is not resolved

at the Port level, “the written record of the dispute shall be referred to the Joint

Negotiating Committee, which will function as a District Grievance

Committee. . . . ” JA 44a.

At either level, if a majority develops for a disposition of the

grievance, the matter ends there. Period. Neither the local union nor the

particular employer involved in the dispute can appeal from a majority vote.

No arbitrator enters the picture unless the industry committees deadlock at

both the Port level and the District level.

The Seniority Board Agreement has no relevance to an employer’s

refusal to hire (as opposed to a gang leader or header refusing to hire). If it

did, the complaint process under the Seniority Board Agreement is even more

truncated The Seniority Board is composed of two union representatives and

two Employer representatives. JA 48a-49a. A determination by a majority of

the Board is “final and binding,” If the Board “shall be unable to reach a

determination of a particular dispute, the dispute shall be submitted to a

committee of two [one union and one management, both from outside the Port

of Charleston] for final determination.” If these committee members deadlock,

the grievant has no further appeal.

8 The Fourth Circuit’s assertion in Austin that the worker was a

“party” was a fundamental error in that court’s premise from which the

majority reasoned to an erroneous conclusion. 78 F.3d at 883 n.2.

21

initiate and proceed with a “grievance” through the grievance

mechanism.

Thus, the grievance mechanism is limited to application

of the agreement, unless the parties clearly define a “grievance”

to include alleged violations of rights deriving from public law.

Violations o f discrimination statutes were defined as

“grievances” in Austin v. Owens-Brockway Glass Container,

Inc., 78 F.3d 875, 879-80 (4th Cir.) (“This Contract shall be

administered in accordance with the applicable provisions of the

Americans With Disabilities Act. . . . any disputes under this

Article as with all other Articles o f this contract shall be subject

to the grievance procedure.”), cert, denied,___U .S .___ , 117

S. Ct. 432 (1996). Only specific language like that found in

Austin could enable union and management to submit an

individual worker’s claim of a violation of a federal statute to

grievance-arbitration.

This Court’s decisions under Section 301 have

consistently taken this approach. (See infra Argument IV.C.)

Both in Lingle v. Norge Division o f Magic Chef, 486 U.S. 399

(1988), andLivadasv. Bradshaw, 512 U.S. 107 (1994), as well

as in earlier cases, the Court has held that labor agreements do

not require arbitrating state law claims that do not depend on

interpreting the bargaining agreement, unless the agreement

expresses a “clear and unmist akeable” intent to submit such

claims to arbitration. Such intent is never found.

The court below thus erred in interpreting the general

grievance provisions of the labor agreement to require

arbitration of petitioner’s federal statutory ADA claim

2 2

II. Because the collective bargaining process is designed

to be controlled by the majority, the rights of victims

of discrimination cannot be waived by a bargaining

representative, and the union here did not intend to

waive those rights.

In Alexander, in discussing why the award made by an

arbitrator who had heard the contract claim was not

automatically entitled to deference by the federal court, this

Court stated, 415 U.S. at 58 n. 19, the concern that individual

statutory rights would be compromised in the interest o f the

majority. The Court observed that “a breach o f the union’s duty

o f fair representation may prove difficult to establish.” Seven

years later, in Barrentine, this Court relied on the potential for

compromise o f individual rights as the first reason for denying

preclusion to the decision of the joint union-management council

that denied a grievance stating a wage claim. 450 U.S. at 742.

Continuing to today, the concern that the majority will decide to

forego a valid individual statutory claim has been a principal

reason this Court has refused to allow grievance-arbitration

remedies in labor agreements to supplant judicial remedies for

violation of federal statutes. See McDonald v. City o f West

Branch, 466 U.S. 284 (1984); Gilmer, 500 U.S. at 35 (1991);

Livadas, 512 U.S. at 127 n.21 (1994).

These concerns dictate that imprecise language in

bargaining agreements should not be construed as waiving

minority rights. (See cases under Section 301, infra, IV.C.)

The risk o f majority waiver in pursuing an individual

claim is substantial. The negotiations that lead to the terms of

the bargaining agreement (the pre-dispute agreement that

respondents assert waived petitioner’s judicial remedies),

present an even greater risk o f the majority’s compromising

minority rights, since the numerous considerations, all at issue

at the same time, make it impossible to identify the quid pro quo

for compromising minority rights.

23

A. The union’s role derives from its authority to

represent workers in exercising the collective

right to strike, and in exercising the collective

rights bargained for in relinquishing the

right to strike, not by compromising

statutory rights of minorities.

As this Court noted in Barrentine, 450 U.S. at 735:

“[T]o promote industrial peace, the interests o f some employees

in a bargaining unit may have to be subordinated to the

collective interests of a majority o f their co-workers.” The

Court had earlier observed in Alexander, 415 U.S. at 54, “The

primary incentive for an employer to enter into an arbitration

agreement is the union’s reciprocal promise not to strike,”

china Boys Markets v. Retail Clerks Union, 398 U.S. 235, 248

(1970). See also, e.g., Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln Mills,

353 U.S. 448, 455 (1957). The union is not permitted to

negotiate away the rights o f a protected minority in return for

concessions that benefit the majority of workers in the unit.

Steele v. Louisville &N.R.. Co., 323 U.S. 192 (1944).

The arbitration clause and the scope o f its application

must be interpreted consistently with its origins in the union’s

relinquishing the collective right to strike, and not as a waiver of

individual rights to which workers are entitled under federal

statutes applicable to those workers as individuals.9 The Fourth

Circuit’s view, as stated in Austin, 78 F.3d at 885, confuses the

fundamental nature of the collective bargain -- relinquishment of

the right to strike as quid pro quo for the right to arbitrate

disputes under the collective bargaining agreement -- by adding

relinquishment of individuals’ statutory rights to the mix of

9 “ Since an employee’s rights under Title VII may not be waived

prospectively, existing contractual rights and remedies against discrimination

must result from other concessions already made by the union as part of the

economic bargain struck with the employer.” Alexander v. Gardner-Denver

Co., 415 U.S. at 52.

24

concessions, notwithstanding that this Court has never

authorized waiver by the union of workers' individual rights.

As this Court observed in Alexander, since the union

exercises the collective rights of workers, it “may waive certain

statutory rights related to collective activity, such as the right to

strike.” 415 U.S. at 51. But in exercising that exclusive

authority, the union cannot discriminate against minorities —

whether the worker be a member o f a minority ethnic group; a

member o f a disadvantaged gender; a worker o f an advanced

age; a non-member or dissident member o f union; or an

“individual with a disability.” For example, if the union

systematically disadvantages minority workers by refusing to

process grievances for a class of minority workers, it violates

Title VII. Goodman v. Lukens Steel, 482 U.S. 656 (1987).

As discussed in Alexander and Barrentine, many federal

employment statutes are “designed to provide minimum

substantive guarantees to individual workers.” 450 U.S. at 737.

Congress has clearly stated that the purpose o f the Americans

with Disabilities Act is to provide such ‘‘minimum substantive

guarantees” for “individuals with disabilities [emphasis added],”

in many spheres o f social activity, including employment. 42

U.S.C. §§ 12101(a), (b). By the nature o f the enactments, all

employment discrimination statutes are “designed to provide

minimum substantive guarantees,” i. e., protection from

discrimination, ‘Tor individual workers.”

As with the Title VII rights discussed in Alexander, the

“substantive guarantees” to be free from discrimination cannot

be waived prospectively. It would defeat the “paramount

purpose” of each Congressional enactment to allow an employer

or a union -- separately or in concert -- to condition employment

on waiver o f substantive statutory guarantees — with the

employee left to “take it or leave it.” Such a policy would allow

sophisticated but unscrupulous business enterprises that are

“covered employers” under the terms of the ADA and other

25

statutes to “opt out” of that coverage by conditioning all jobs on

waiver o f those rights.

Unions, as well as employers, can violate the ADA. For

example, if an employee proposes several options to

accommodate his disability, the employer may object to one

proposal and the union may object both to that proposal and to

all other alternative accommodations requested. The bargaining

agreement cannot commit to grievance-arbitration the worker’s

rights against the union, which has an express conflict. Since the

union could not “waive” judicial remedies for claims filed jointly

against the union and employer, it should not have the power to

waive judicial remedies for any claims. Compare NLRB v.

Magnavox Company, 415 U.S. 322, 325 (1974). But for this

case, the Court need not decide the limits on a union’s power to

waive individual remedies; the Court need only find that a

bargaining agreement that is silent about the issue will not be

construed to waive a worker’s access to the courts.

B. The Union’s exclusive control of the

grievance process makes labor arbitration

unsuitable for enforcing minimum statutory

standards for individuals.

When this Court decided Gilmer, Justice White

emphasized that Alexander and its progeny, on which petitioner

relies, were distinguishable from Gilmer, 500 U.S. at 35:

[Bjecause the arbitration in those cases occurred in the

context of a collective bargaining agreement, the

claimants there were represented by their unions in the

arbitration proceedings. An important concern therefore

was the tension between collective bargaining

representation and individual statutory rights. . . .

This Court has identified two related reasons for this

concern: (1) the union often faces conflicting demands, which

range from reluctance to accuse management of racism or sexual

26

harassment, to outright conflicts o f interest when the union is

charged with discrimination; and (2) the union’s decisions about

pursuing a grievance can be reviewed only in a suit for breach of

the duty of fair representation (DFR), an imprecise and

inequitable means o f enforcing statutory rights.

1. Conflicting demands and conflict of interest.

In Alexander, this Court noted, 415 U.S. at 58 n. 19:

In arbitration, as in the collective bargaining process, the

interests of the individual employee maybe subordinated

to the collective interests o f all employees in the

bargaining unit. . . . Moreover, harmony of interest

between the union and the individual employee cannot

always be presumed, especially where a claim o f racial

discrimination is made. . . . Congress thought it

necessary to afford the protections o f Title VII against

unions as well as employers. [Citations omitted.]

Congress also “thought it necessary to afford the

protections” of the Americans with Disabilities Act as to unions.

42 U.S.C. § 12111(2). (“The term ‘covered entity’ means an

employer, employment agency, labor organization, or joint

labor-management committee.”) Congress has expressly

prohibited discrimination by unions in every modem federal

employment discrimination statute. See, e.g., 29 U.S.C. §

623(c) (ADEA). The union itself may be guilty of

discrimination, either in hiring or admission to membership, or

in processing grievances against the employer. Goodman v.

Lukens Steel, 482 U.S. 656 (1987).

Even if the union does not actively discriminate, it may

be inhibited in its response to a statutory claim because other

workers in the same bargaining unit are discriminating against

the claimant or because other workers resent the relief the

claimant seeks. Other workers can create a “hostile work

environment” that violates any of the federal anti-discrimination

27

statutes. While this type o f claim is currently most commonly

pursued in sexual harassment cases, e.g. Oncale v. Sundowner

Offshore Services, In c .,___U .S .___ , 118 S.Ct. 998 (1998),

and in claims of harassment of a racial or ethnic minority

employee, a ‘hostile environment’’ can also be created for a

worker with a disability protected by the ADA. For example, a

union member might reveal that a co-worker is HIV-positive,

and the infected employee might be shunned by other workers

in the unit.

A related problem appears when the relief sought by the

victim o f discrimination requires resources the union considers

scarce. As this Court observed in Barr entitle, 450 U.S. at 742:

a union balancing individual and collective interests

might validly permit some employees’ statutorily granted

wage and hour benefits to be sacrificed if an alternative

expenditure o f resources would result in increased

benefits for workers in the bargaining unit as a whole.

Unions may also be reluctant to discuss proposals for

“reasonable accommodation” that an individual with a disability

requests under the ADA. The National Labor Relations Board

has declared that a union’s refusal to bargain over a proposed

accommodation would violate § 8(b)(3) of the National Labor

Relations Act. NLRB Memorandum on Collective Bargaining

and ADA (Sept. 1992), reprinted in ADA MAN. (BNA)

70:1021. Uncertainty about the scope of obligations under the

ADA makes the union’s position especially precarious.

The on-going relationship between the union and the

employer may also make the union reluctant to assert claims of

discrimination. Allegations of racial discrimination are a “hot-

button” issue, which unions often seek to avoid because o f the

adverse effect such claims have on the bargaining relation. See

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 482 U.S. at 667-68 (union

asserted it omitted “racial discrimination claims in grievances

claiming other violations of the contract . . . because the

28

employer would ‘get its back up’ if racial bias was charged,

thereby making it more difficult to prevail”). Similarly, a claim

o f sexual harassment by a supervisor might be so potentially

explosive that the union, concerned with everyday contacts with

the supervisor, would hesitate to pursue the complaint unless the

victim presented overwhelming corroborating evidence.

2. Unions have wide latitude in handling

grievances.

As this Court observed in discussing the Fair Labor

Standards Act claims at issue in Barrentine, 450 U.S. at 742:

even if the employee’s claim were meritorious, his union

might, without breaching its duty of fair representation,

reasonably and in good faith decide not to support the

claim vigorously in arbitration.

The union may make such a decision simply on the basis of

allocation of its own scarce resources, even if the claim does not

initiate conflicting demands within the unit. As another court o f

appeals observed in rejecting the rationale of Austin, in Pryner

v. Tractor Supply Co., 109 F.3d 354, 362 (7th Cir.), cert,

denied, ___U .S .___ , 118 S.Ct. 294 (1997):

[T]he union has broad discretion as to whether or not to

prosecute a grievance. . . . Corresponding to this

expansive and ill-defined discretion, the scope o f judicial

review ofits exercise is deferential. [Citations omitted.]

The result is that a worker who asks the union to grieve

a statutory violation cannot have great confidence either

that it will do so or that if it does not the courts will

intervene and force it to do so. . . .

“[A] breach of the union’s duty o f fair representation may prove

difficult to establish.” Alexander, 415 U.S. at 58, n.19.

The facts o f this case are a particularly compelling

example o f the difficulty in proving a breach of duty by the

29

bargaining representative. Petitioner immediately sought the

union’s assistance. When the matter could not be resolved by

initial discussions with the employer, the president o f the local

union advised petitioner to retain private counsel to pursue his

statutory remedies under the ADA, rather than his contract

remedies. Since the bargaining agreement lacks any “non-

discrimination” clause, the statutory remedies fit the claim more

closely. This was not an unusual position for a union to take;

compareBrisentine v. Stone & Webster Engineering Corp., 117

F.3d 519, 521 (11th Cir. 1997), where the local union also

declined to pursue a contract claim of disability discrimination.

As respondents have repeatedly pointed out, most

recently in Respondent’s Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, page

14, petitioner has not accused the union of a breach of the duty7

o f fair representation. How could petitioner have possibly

prevailed on a DFR claim, which requires proof o f arbitrary or

discriminatory action by the union? In January, 1995, the union

had no notice that the Fourth Circuit would “overrule”

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., a year later. It was certainly

not arbitrary or irrational for the union to think that petitioner

had an administrative and judicial remedy; to this day, every

other appellate court has agreed that Alexander is still good law,

as this Court stated in Gilmer and Livadas.

As Justice White observed for the court in Gilmer, none

of the concerns discussed in this section of the argument had any

application in that case. But in this case, concerns of majority

waiver of minority rights are as fresh and compelling as they

were when this Court decided Alexander, Barrentine,

McDonald, Gilmer, and Livadas.

3 0

HI. This bargaining agreement, like most labor

agreements, does not provide a mechanism for

adequately vindicating rights under employment

discrimination statutes.

In Gilmer, the employer compelled the employee to

arbitrate his claims, rather than to sue on the claims in court.

Here, the employers have successfully avoided ever defending

the claim on the merits. The cursory manner in which the courts

below have denied petitioner any hearing on the merits o f his

ADA claim demonstrates how difficult it is to use labor

grievance-arbitration “effectively” to “vindicate a statutory cause

of action. . .

In Gilmer, this court reiterated that an employee seeking

statutory remedies cannot be required to “forgo the substantive

rights afforded by the statute. . . ” 500 U.S. at 26, quoting

Mitsubishi, 473 U.S. at 628. Thus, one requirement for

enforcement of a compulsory arbitration agreement is that “‘the

prospective litigant effectively may vindicate [his or her]

statutory cause of action in the arbitral forum. . . 500 U.S. at

28, quoting Mitsubishi Motors, 473 U.S. at 637. This Court has

also emphasized that if arbitration “clauses operated . . . as a

prospective waiver of a party’s right to pursue statutory

remedies . . . , we would have little hesitation in condemning the

agreement as against public policy.” Mitsubishi Motors v. Soler

Chrysler-Plymouth, 473 U.S. at 637 n.9. The unique nature of

labor grievance mechanisms as “part and parcel of the collective

bargaining process,” prevent individuals from effectively

vindicating causes of action based on statutes that “provide

minimum substantive guarantees” for workers.

A major concern expressed by this Court in Alexander

was that the grievance-arbitration mechanism in labor

agreements was not adequate for the determination of statutory

claims of employment discrimination. 415 U.S. at 56-58. These

concerns remain fresh today even after compulsory arbitration

31

has extended commercial arbitration to statutory claims. See,

e.g., Gilmer, 500 U.S. at 34 n.5.

Through wholesale modifications, perhaps the labor

grievance mechanism could be transformed to adopt the

procedures o f modem commercial arbitration. But such

transformation would either destroy the effectiveness of

grievance mechanisms in their current forms, or it would create

an acute tension between the limited procedures and rights of

workers in adjustment of contract grievances, on one hand, and

the more formal, sophisticated procedures to vindicate statutory

rights, on the other. The “bright-line” rule of Alexander has

worked well to preserve the collaborative bargaining processes

reflected in existing grievance mechanisms, and also to preserve

the judicial forum that Congress adopted for the vindication of

statutory rights in employment discrimination cases.

A. The Grievance Mechanisms are incompatible

with vindication of statutory rights.

Grievances are required to be asserted in

extraordinarily short time periods. The bargaining agreement

in this case is typical o f labor agreements. An extremely short

time is allowed to assert a grievance: “no later than 48 hours

after such discussion” if the grievance “cannot be promptly

settled.” JA 43a. In this case, although petitioner retained an

attorney within 15 days, petitioner’s ADA claim was already

defaulted by the union’s failure to pursue the grievance

procedures within 48 hours. JA 55a,10

10 Petitioner argued below that he was entitled to proceed in court

because this application of the grievance procedure violated the ADA’s

180/300 day statute of limitations for filing charges. The District Court stated,

without explanation, Pet. App. 16a: “The Court is not concerned that this

procedure unduly limits the time in which an employee has to bring an

employment discrimination claim.” The Court of Appeals ignored petitioner s

argument that he had complied with the statutory time limit.

32

Congress has extended the time for filing administrative

charges to 180 days, 300 days in those states, such as South

Carolina, which have state Fair Employment Practices Acts. 42

U.S.C. § 2000e - 5(e)(1), adopted for the ADA in 42 U.S.C. §

12117(a). Enforcing much shorter time limits in the grievance

process clearly prevents the “vindication o f rights” under

employment discrimination statutes, since Congress has

mandated the courts “to interpret this [statutory] time limitation

so as to give the aggrieved person the maximum benefit o f the

law. . . See Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, 455 U.S. 385, 395

(1982); cf. Graham Oil Co. v. ARCO Products, 43 F.3d 1244,

1247-48 (9th Cir. 1995) (reducing time for asserting commercial

claim from one year to six months, and other limitations,

rendered the arbitration clause unenforceable); Nelson v. Cyprus

Baghdad Copper Co., 119 F.3d 756, 761 n.8 (9th Cir. 1997),

cert, denied,___U .S.___ , 66 U.S.L.W. 3686 (April 20, 1998)

(claim under Americans with Disabilities Act); see also Cole v.

Bums Intern. Security Services, 105 F.3d 1465, 1482 (D.C. Cir.

1997).

This agreement does not guarantee access to

impartial arbitration. As discussed above, Section ELB, this

Court has consistently been concerned that the worker does not

control prosecution o f his grievance nor the demand for

arbitration. But here the problem of access to arbitration is even

more fundamental. Under the bargaining agreement, not even

the worker’s local union can take a claim to arbitration if the

industry committee rejects the worker’s claim. Arbitration is

available only when the District Negotiating Committee

deadlocks on the grievance. JA 44a. For claims before the

Seniority Board, that Board’s determination is final and binding.

There is never any access to an arbitrator. JA 48a.

For statutory claims asserted against the union, or