Luevano v. Campbell Appendix to Background Memorandum Regarding the Settlement of the Pace Case

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Luevano v. Campbell Appendix to Background Memorandum Regarding the Settlement of the Pace Case, 1981. a4b4d404-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a75ce45b-0063-4f11-b9fc-99335201e7d5/luevano-v-campbell-appendix-to-background-memorandum-regarding-the-settlement-of-the-pace-case. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

V

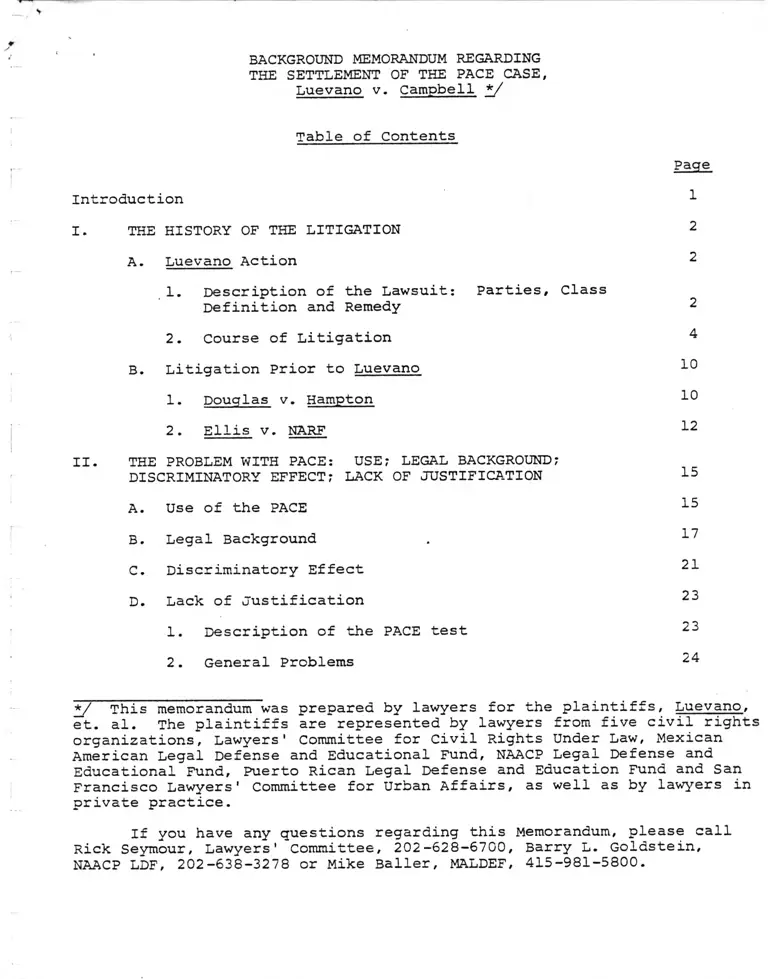

BACKGROUND MEMORANDUM REGARDING

THE SETTLEMENT OF THE PACE CASE,

Luevano v. Campbell j*/

Table of Contents

Page

oduction 1

THE HISTORY OF THE LITIGATION 2

A. Luevano Action 2

1 . Description of the Lawsuit: Parties, Class

Definition and Remedy 2

2. Course of Litigation 4

B. Litiaation Prior to Luevano 10

1 . Douqlas v. Hampton 10

2 . Ellis v. NARF 12

THE PROBLEM WITH PACE: USE? LEGAL BACKGROUND;

DISCRIMINATORY EFFECT; LACK OF JUSTIFICATION 15

A. Use of the PACE 15

B. Legal Background 17

C. Discriminatory Effect 21

D. Lack of Justification 23

1 . Description of the PACE test 23

2 . General Problems 24

*/ This memorandum was prepared by lawyers for the plaintiffs, Luevano,

et. al. The plaintiffs are represented by lawyers from five civil rights

organizations, Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Mexican

American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund and San

Francisco Lawyers' Committee for Urban Affairs, as well as by lawyers in

private practice.

If you have any questions regarding this Memorandum, please call

Rick Seymour, Lawyers’ Committee, 202-628-6700, Barry L. Goldstein,

NAACP LDF, 202-638-3278 or Mike Bailer, MALDEF, 415-981-5800.

il

Page

III. THE SOLUTIONS: PROVISIONS IN THE CONSENT

DECREE; THE REMEDY THAT WOULD BE AVAIL

ABLE IF THE PLAINTIFFS PREVAIL IN COURT 31

A. Description of the Consent Decree 31

B. Remedy Available after Litigation 36

Appendix A Letter from Dr. William Burns to the

N.Y. Times

Appendix B Affidavits executed by Dr. Barrett in

Douglas v. Hampton (PACE sample questions

attached as exhibit)

Appendix C Plaintiffs' Trial Brief Re PACE, FSEE and

the Appentice Selection System, Ellis v.

NARF, pages 1-40.

Appendix D Letter from John H. Shenefield, Former

Associate Attorney General, to the

Washington Star

INTRODUCTION:

On January 16, 1981 Judge Joyce Green provisionally approved

the Consent Decree in Luevano v. Campbell which calls for the

federal government to phase out its use of an examination which

has an enormous adverse impact upon blacks and Hispanics. This

settlement represents an important civil rights issue. In effect, the

federal government has agreed to apply to their system for selecting

individuals for hire into the civil service the Supreme Court's

admonition that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 "proscribes

not only overt discrimination but also practices that are fair in

form but discriminatory in operation. The touchstone is business

necessity. If an employment practice which operates to exclude

Negroes cannot be shown to be related to job performance, the prac

tice is prohibited." Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 431

(1971). The reasons why the Decree is a significant step towards

insuring equal employment opportunity in the federal government con

sistent with the requirements of the Civil Rights Act and why the

Decree is sound public policy are apparent if the history of the

litigation, the problem with the Professional and Administrative

Career Examination (PACE), and the solution to that problem offered

by the Decree are reviewed.

2

I. THE HISTORY OF THE LITIGATION

A. Luevano Action

1. Description of the Lawsuit; the Parties, Class

Definition and Remedy

In January 1979, the plaintiffs filed a class-action com

plaint on behalf of themselves and other blacks and Hispanics alleging

that the "adverse impact of the PACE on plaintiffs and their class is

so severe that it threatens to segregate the middle and upper

levels of the executive branch of the Federal government" and that

"despite the disproportionately adverse effect of the PACE on

blacks and Hispanics" the defendant, the Office of Personnel

Management, had never validated (demonstrated the job-relatedness)

of the PACE as required by law. Thus, plaintiffs alleged that the

PACE was discriminatory and unlawful under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 (as amended 1972), 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et.seq.

(Title VII).

The plaintiffs include Angel Luevano, an Hispanic citizen,

Melody A. Van, a black citizen, and Vicky L. Chapman, a black citizen.

All three plaintiffs took and failed the PACE in April 1978 and thus

were barred from consideration for hire into entry-level positions

for which the PACE is used. All three plaintiffs filed administrative

complaints. Additionally, there is an organizational plaintiff, I. M.

A. G. E. De California (IMAGE). IMAGE is an association of Hispanic

American governmental employees. IMAGE has approximately 80 chapters

and 3,000 members nationwide. Subsequently, a fourth individual plain

tiff, Vilma D. Diaz, an Hispanic citizen was added. She took the

PACE in March 1979, failed and thus was banned from consideration

3

for hire into all entry-level positions for which the PACE is used.

As did the other individual complainants, Ms. Diaz properly filed

an administrative complaint.

The plaintiffs are represented by lawyers from five civil

rights organizations, Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law,

Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education

Fund, and San Francisco Lawyers' Committee for Urban Affairs, as

well as by lawyers in private practice.

The plaintiffs sought to represent a class defined as follows:

All past, present, and future black and

Hispanic applicants for professional,

administrative, or technical jobs for

which the defendant administers the

Professional and Administrative Career

Examination (PACE) who have taken the

Professional and Administrative Career

Examination (PACE) within the period of

limitations or who will take it here

after, and who have been, are being, or

may in the future be, denied equal

employment or promotional opportunities

as a result of defendant's use of the

Professional and Administrative Career

Examination (PACE).

The defendant, objected to the inclusion in the class of in

dividuals who were denied promotional opportunity because the

plaintiffs do not possess the same interest as individuals who were

denied promotion. However, the District Court ruled in favor of the

plaintiffs and included in the class individuals denied promotional

opportunities as a result of the defendant's use of the PACE because

the underlying question of the litigation concerns the PACE and the

plaintiffs "are fully capable of litigating that allegation as it

applies both to initial applicants and possible promotes". Order,

November 12, 1980*

To remedy the unlawful use of the PACE, the plaintiffs sought

an injunction barring the Government from using the PACE, affirmative

action requirements designed to compensate the class for the loss of

employment opportunity, back pay to equal the loss of wages suffered

because of the denial of jobs, and other appropriate relief. The

District Court's decision to include individuals who were denied pro

motional opportunity because of the use of the PACE greatly in

creased the potential liability of the Government. The PACE was

only developed by OPM for use as a selection instrument for hire.

0PM has not even contended that the PACE is appropriate for use

as an instrument for the promotion of experienced employees. However,

agencies and departments have used the PACE to select individuals for

promotion, a purpose for which the PACE is neither designed nor in

tended. Since the Government has no justification for the use of

the PACE for promotion and since the PACE has a substantial adverse

impact, the class members denied promotional opportunity because of

the use of the PACE would in all likelihood, be entitled to affirma

tive relief and back pay, see section III, B, regardless of

whether the PACE is appropriate for selection for hire.

2. Course of Litigation

In March 1979, two months after they filed the Complaint

the plaintiffs filed a set of interrogatories inquiring as to the use,

racial effect, and justification for the use of the PACE. Also the

plaintiffs filed a request for production of documents which contained

information regarding these issues. As discussed in the following

i/section, the Luevano action is actually the third in a series of

major lawsuits which have challenged the Government's use of the PACE

or the test used immediately preceding the PACE, the Federal Service

Entrance Examination (FSEE).

17 The two prior lawsuits, Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F. 2d 976 (D.C. 1975); Ellis v. NARF, Civil Action No. C-73-1794 (N.D. Cal.)> are

described in detail in section 3.

5

As a result of information gathered during the course of these

lawsuits, the plaintiffs in Luevano had already obtained a con

siderable amount of information regarding the use, racial effect

and purported justification for the PACE.

Shortly after the filing of Luevano the parties agreed to«

explore the possibility of settlement. Discussions began within a

couple of months after the filing of the lawsuit. As a result of

representations made by the parties that settlement talks were pro

gressing the District Court entered an Order on Aprii 18, 1979, pro

viding that OPM did not have to respond to the Complaint and plaintiffs'

discovery until the middle of June 1979. In order that "further

negotiations toward a possible settlement may continue" the District

Court by Orders dated June 21, July 20, and September 6 granted further

extensions of time to the Government. In December 1979 the Government

answered the Complaint but was granted by Order entered on December 13

another extension of time to answer the discovery requests because:

the parties have conferred on several recent

occasions and as a result of these meetings a

settlement conference has been tentatively

scheduled for January 16, 1980, in California

in order to allow the full participation of

plaintiffs' co-counsel. The purpose of the

California meeting is to confer and hopefully

resolve the remaining issues necessary for the

settlement of this action.

After the January meeting in California the parties were

close to settlement and so informed the District Court. However, the

parties failed to finalize the agreement and the plaintiffs in July

1980 requested the Government to admit certain facts. This request

detailed information regarding the use, racial effect and justifica-

for the PACE. During this period the parties continued to work

6

towards settlement. On September 15 the Government answered

the plaintiffs' interrogatories and request for production of

documents. On the following day the plaintiffs informed

counsel for the Government that the answers, at least in

part, were inadequate.

A status conference was held by the District Court on

September 23, 1980. The parties informed the Court that the

negotiations were continuing but having been so informed since

April 1979, the District Court ordered the parties to take

several actions in order to expedite settlement or litigation:

ORDERED that plaintiff shall have until September 25, 1980,

to submit a motion asking the Court to consider as admitted the

Requests for Admissions filed July 17, 1980, and that the defendant

shall have until September 29, 1980, to respond to plaintiff's motion,

and it is

FURTHER ORDERED that the defendant will make an offer of

settlement no later than October 3, 1980, and that the parties

will meet to discuss that offer no later than October 8, 1980,

and that plaintiffs will respond with a counter-offer, as appro

priate, no later than October 13, 1980, and it is

FURTHER ORDERED that the defendants and the plaintiffs will

before October 3, 1980, discuss the outstanding issues regarding

discovery, and that plaintiffs shall file as appropriate and not

later than October 10, 1980, a motion to compel discovery, and it

is

FURTHER ORDERED that the parties will convene in chambers

for a Status Conference on October 23, 1980, at 9:30 A.M.

As a result of the Court's Order both litigation and

settlement discussions progressed. OPM answered the request for

admission of fact; the parties resolved the pending discovery

dispute; the plaintiffs filed a second set of interrogatories and

7

a second set of requests for production of documents; and the

parties informed the Court as to the additional time that would

be required to prepare the case for trial. Also pursuant to the

Court's direction the parties exchanged settlement terms covering

the matters that remained unresolved after 17 months of negotia

tions. As a result of this exchange, the parties reached a tenta

tive agreement. As might be expected in a case involving the

selection of candidates for 118 job categories in the federal civil

service, the negotiations were long and arduous. As a result of

the negotiations, the District Court granted six extensions of time

beginning in April 1979 and ending in September 1980 with a direct

order for the parties to exchange additional settlement proposals.

Due to the lengthy delay in the litigation, the Court

did not grant any additional extensions in the litigation. Rather,

on November 12, the Court ordered that trial would commence on June

22, 1981. After 21 months of settlement discussions and an impend

ing trial date, the parties finally concluded the settlement and it

was presented to the District Court for provisional approval on

January 9, 1981.

While engaging in settlement discussions, the plaintiffs'

counsel with the assistance of experts reviewed the evidence regarding

the adverse effect of the PACE upon minority candidates and the

evidence regarding 0PM's attempt to justify the job-relatedness or

validity of the PACE. The evidence of adverse impact was undisputed

and overwhelming, see pp. 21-22 infra. The evidence regarding

validity was complex. However, as described in greater detail in

8

section II, D, infra, we think that the evidence shows that OPM

has not demonstrated that the PACE is job-related or appropriately

used. We reached this conclusion based upon several sources of

evidence. First, we had a considerable amount of evidence which had

been gathered and analyzed in prior cases regarding the PACE or the

FSEE. Second, we examined and we had experts examine reports pre

pared by OPM regarding its attempts to justify the use of the PACE.

Third, we consulted with experts in the field of personnel testing.

We then reviewed all this evidence in light of the applicable case

law and administrative regulations.

In reviewing the PACE several experts have advised that

the PACE had not been shown to be job related. We have consulted

experts since the beginning of the lawsuit. In order to explain the

development of the litigation it is helpful to describe briefly that

consultation. We consulted Dr. William C. Burns, who is an in

dustrial psychologist, the Director of Personnel Research for Pacific

Gas and Electric Company, a former member in 1966 of Governor Reagan's

Task Force on Efficiency and Cost Control in State Government, and a

current member of the Advisory Panel on Personnel Selection Procedures,

Division of Industrial-Organizational Psychology, American Psychological

Association. Dr. Burns' opinion of the PACE is summarized in his letter

to the N.Y. Times (which is attached as Appendix A). Dr. Burns has

stated that "PACE is an affront to the merit principle" and that "PACE

is the kind of test that discriminates most severely." Moreover, he

thinks that "[ajnyone interested in trying to make the federal bureau

cracy more efficient should welcome the chance to bury PACE and re

place it with job-specific tests that give the government a way to

locate the most qualified applicants from all groups."

9

We have also contacted Dr. Richard Barrett, an industrial

psychologist and a former Member of the Advisory Panel on Personnel

Selection Procedures, Division of Industrial—Organizational Psychology,

American Psychological Association. Dr. Barrett has testified in

many fair employment cases including the landmark Supreme Court cases

of Griggs y. puke Power Company and Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody.

Dr. Barrett has followed and reviewed the development of PACE from

its inception. He served as an expert for the plaintiffs in Douglas

v. Hampton which challenged the legality of the FSEE. In affidavits

executed for Douglas on November 1, 1975 and January 2, 1976 (which

are attached as Appendix B), Dr. Barrett stated that "the tests are

similar in format, content, difficulty, and emphasis on verbal and

numerical ability.... [T]he tests are so similar that I believe that

they would be highly correlated with each other, and [that the PACE]

would have an adverse impact on blacks similar to that found [in a

study on the FSEE]". Dr. Barrett correctly predicted the enormous

impact of the PACE. Dr. Barrett stated that: \

neither PACE nor the FSEE have been properly

validated in accordance with professionally

acceptable standards. Unlike the Civil

Service Commission, private industry, the

armed forces and educational institutions have

all made substantial progress towards proper

test validation and there is no professionally

acceptable reason why the Civil Service Commission

cannot do the same.

We have also consulted Dr. James Outtz, an industrial psycholo

gist who has served as a private consultant to local governments. As

did Drs. Burns and Barrett, Dr. Outtz advised that the PACE was neither

properly validated nor properly used and that alternatives could be

developed which would have less adverse impact upon minorities.

10

B. Litigation Prior to Luevano

1. Douglas v. Hampton

Litigation challenging the PACE or its predecessor the FSEE

began almost a decade ago. In order to fully understand Luevano, a

brief review of this prior litigation is required. In 1971 a federal

civil action, Douglas v. Hampton, was filed alleging that the use of

the FSEE for the selection of individuals for hire constituted unlaw

ful racial discrimination. The plaintiffs moved for a preliminary in

junction against the use of the FSEE. The district court denied the

motion and the plaintiffs appealed. The United States Court of

Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit, in a detailed opinion rendered

by Judge Spottswood Robinson vacated the opinion of the district

court. Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F. 2d 976 (1975). The Court ruled

that the plaintiffs were "likely to succeed on the merits", that

the FSEE had a substantial adverse racial impact and that the Civil

Service Commission had not demonstrated that the FSEE was valid. The

Court commented upon the CSC's attempt to show job relatedness through

2J

the use of construct validity.

Although construct validity is a professionally

recognized technique for proving validity, we

2 / The Court defined the " [t]hree techniques for proving the validity

of testing procedures [which] have been judicially and professionally

noted. 'Empirical' validity [also termed criterion-related validity]

is demonstrated by identifying criteria that indicate successful job

performance and then showing a correlation between test scores and

those criteria. 'Construct' validity is proven when an examination is

structured to determine the degree to which applicants possess identifi

able characteristics that have been determined to be important to

successful job performance.'Content' validity is established when the

content of the test closely approximates the tasks to be performed on

the job by the applicant." (Footnote omitted).

The standards for establishing validity according to these pro

cedures are set forth in the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures, 43 Fed. Reg. 38290 (1978).

11

note that no court has found a demonstration of

construct validity sufficient to satisfy Griggs

[v. Duke Power Co;]. It may be that in a proper

case a convincing demonstration of construct

validity will suffice. It should be noted,

however, that construct validity does not con

clusively establish that test, results are

directly related to job performance. It

merely means that the test accurately measures

certain constructs; in determining whether

a showing of construct validity satisfies

Griggs, the court must also determine whether

the constructs are themselves related to job

performance. In light of the strong pref

erence expressed in reported opinions for

empirical validity and the greater reliabil

ity of empirical validity, we think construct

validity may be considered, if at all, only in

certain circumstances. (Footnote omitted).

This Opinion, by the Court of Appeals has some direct rel

evance for Luevano since OPM maintains that it showed the job re

lationship of PACE through construct validity and since the PACE, as

Dr. Barrett stated, is "similar" to the FSEE. The issue of the validity

of the FSEE or PACE was not finally decided in Douglas. In the district

court the Government had replaced the FSEE with the PACE. The district

court agreed that the issue of injunctive relief, whether to bar the

use of the FSEE was moot; but the court stated the issue regarding in

dividual relief for the plaintiffs, such as back pay, was not moot.

In Douglas the plaintiffs also attempted to challenge the successor

to FSEE, the PACE. However, the Government argued and the district

court agreed that prior to instituting a judicial challenge to the

PACE individuals had to first exhaust their federal administrative

remedies. Douglas v. Hampton, Civil Action No. 313-71 (Order,

January 20, 1976). Moreover, the Government offered to settle the

1/individual claims of the plaintiffs. Thus, the Government avoided

having the issue of the validity of the FSEE and the PACE adjudicated.

3/ The eight plaintiffs in Douglas received a total of $105,000 in

settlement of their claims. Stipulation of Compromise and Settlement;

(April 13, 1977).

- 12-

2. Ellis v. NARF

In 1973 a class of black, Hispanic, Asian and Native

American civilian employees and applicants for civilian employment

at a naval facility in Alameda, California sued the Navy for main

taining unlawful and discriminatory hiring, promotion, training

and other practices, Ellis, et al. v. Naval Air Rework Facility,

Civil Action No. C-73-1794 (N.D. Calif.). The issue of the legality

of the PACE was squarely raised by this case. Some of the counsel

for plaintiffs in Ellis are now counsel for plaintiffs in Luevano.

In Ellis the plaintiffs undertook extensive discovery of the use,

adverse impact and job relatedness of the PACE.

The evidence of the adverse racial impact of the PACE was

dramatic. It is normally necessary for an individual to score at

least 90 in order to obtain a high enough place on the register so

that the applicant may actually receive a referral to an employing

agency, see section II, A. Thus, as a practical matter, a score of

90 may be viewed as a cut-off score for PACE applicants. The data

for the San Francisco area made apparent that the PACE removed the

entire black and Hispanic applicant pool from contention. Out of

194 persons who obtained scores of 90 or higher, only one was black

and none were either Hispanic or Filipino. (Not all of the applicants

were identified by ethnic group).

Ethnic Distribution of

Applicants With PACE Scores of

90 or Higher (San Francisco Study) -

Number Who Total Who Obtained

Ethnic Grouo Took Test Scores of 90

White 683 172 (25..2%)

Black 93 1 ( 1 ..1%)Hispanic 42 0 ( 0%)

Filipino 46 0 ( 0%)

Total 1019 194 (19.0%)

13

In order for an applicant to be eligible for the PACE

Register the applicant must obtain at least a score of 70 on

the written test. The data compiled from the San Francisco

study show that approximately two-thirds of the white applicants

achieved a score of 70 or better whereas only one-tenth of black

applicants, one-third of Hispanic applicants and one-fifteenth of

the Filipino applicants attained scores of 70 or better. In other

words, nearly 90% of the black applicants, nearly 70% of the

Hispanic applicants and over 90% of the Filipino applicants were

declared to be ineligible as a result of their scores on the PACE.

Ethnic Distribution of Applicants

With PACE Scores of 70 or Higher

______ (San Francisco Study)_________

Number Who

Took Test

683

93

42

46

Number Who Obtained

Scores of 70 or Higher

460 (67.3%)

11 (11.8%)

14 (33.3%)

3 ( 6.5%)

Ethnic Group

White

Black

Hispanic

Filipino

Total 1019 559 (54.9%)

Since the PACE had a severe discriminatory effect upon

minority applicants, the Government had the burden to establish

that the PACE was job related. (See section II, B, for a descrip

tion of the applicable law). In Ellis the plaintiffs obtained the

studies and analyses prepared by the Government in its attempt to

justify the use of the PACE and took over 20 depositions of govern

ment employees who were responsible for developing the PACE or

attempting to justify its use. As a result of a detailed review

of this material and consultations with experts, the plaintiffs

- 14 -

determined that the Government had not demonstrated that the

PACE was job related or appropriately used. The position of

the plaintiffs is set forth in some detail in "Plaintiffs' Trial

Brief Re PACE, FSEE and the Apprentice Selection System". (The

pages, 1-40, which pertain to the PACE are included as Appendix C).

For example, the plaintiffs maintained that (1) the PACE was not

the result of careful job analyses and test development but was in

effect developed prior to the review of the jobs; evidence contrary

to this a priori determination was ignored. Plaintiffs' Trial

Brief in Ellis pp. 15-17, 31-33, Appendix D; (2) the abilities

identified as important for the performance of jcb s by "subject

matter experts" (government job analysts) were not tested by the

PACE, id., pp. 27-29, while "quantitative ability was included

despite the low evaluation of this ability by subject matter

experts, id., pp. 30-31; (3) the Government did not have sufficient

empirical evidence to justify its conclusion that the PACE was

justified for use in selection for 118 jobs when the effects of

the test were measured with respect to only four jobs, id., pp.

19-21, 24-26; and (4) the studies performed for the four jobs

contained critical flaws, id., pp. 21-23.

While these and other technical arguments provide a clear

basis for a district court to find that the PACE was not job related,

there are further arguments, which the plaintiffs would press in

Luevano, see section II, D. In any event, as in Douglas v. Hampton,

the issue of the validity of the PACE was not decided; rather in

1978 the parties entered into a settlement. The agreement provided

affirmative action, $500,000 in class back pay, limitations on the

use of PACE, other injunctive relief and attorneys' fees.

15

II. THE PROBLEM WITH PACE: USE; LEGAL BACKGROUND; DISCRIMINATORY

EFFECT; LACK OF JUSTIFICATION

A. Use of the PACE

In the terminology associated with the selection of federal

employees the word "examination" refers to the complete set of pro

cedures by which selection for employment is made. "Test" specifically

refers to the written test. The Professional and Administrative Career

Examination (PACE) is an assessment instrument used by OPM to identify

individuals for employment into entry-level jobs in 118 professional

and administrative occupations in the federal service. These occupa

tions vary considerably. For example, the following occupations are

covered: Bond Sales Promotion, Outdoor Recreation Specialists,

Industrial Relations, Social Insurance Administration, Computer

Specialist (Trainee), and Labor Management and Employee Relations.

(A complete list of occupations covered by the PACE is attached as

Appendix A to the Consent Decree). In order to compete for an entry-

level PACE job, the applicant must have a four-year college degree

or three years of professional experience or the equivalent combina

tion of experience and education. Over 90% of those individuals who

compete in the PACE are or will be college graduates within nine

months.

The plaintiffs in Luevano did not challenge the basic qualifi

cation standard of experience and education. The Consent Decree

leaves intact this basic qualification standard and the Government

is free to continue to use the standard. The issue in Luevano

concerns only the use of the written test portion of PACE.

The applicant must take a written test. The scores on the

written test are converted into ratings. In order to be con

sidered for competitive appointment, an individual must attain a

- 16 -

rating of 70 or higher. Due to the large number of applicants with

high PACE ratings in many areas of the country and for many jobs , an

applicant must have a rating of 90 or higher in order for the

applicant to be referred to an agency for consideration for appoint

ment. It should be noted that an applicant receives additional

points on the rating scale if he or she has a sufficiently high

grade ooint average or if, in accordance with 5 U.S.C. §3309, he

uor she qualifies for veteran's preference.

After eligible individuals with ratings of 70 or more have been

identified, OPM prepares a rank-order list of the eligible applicants.

If an agency has a vacant position in a PACE job category, the agency

requests from the local OPM Area Office a list of names of PACE

eligibles. The list is referred to as a "certificate". The agency

selects from the certificate. In considering certified candidates,

the agency must follow the "rule of three," 5 U.S.C. §3318, under

which it can select any of the top three eligibles, with special

consideration given to veterans as required by statute.

The written test portion of the PACE was first administered

during the fall of 1974. In the first two years of the use of the PACE

over 225,000 persons each year took the written test and approximately

10,000 of these persons were selected. In the last two years,

approximately 130,000 to 160,000 persons each year took the written

test and approximately 7,000 of these persons were selected.

4 7 These practices are described in detail on pp. 16-17 of the

Consent Decree.

B. Legal Background

What are the legal principles applicable to a lawsuit

which claims that a written test like the PACE is discriminatory

and unlawful? Chief Justice Burger, writing for a unanimous Supreme

Court, established the basic principles governing the legality of

a test or other employee selection standard. Griggs v, Duke Power

Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971). The Court ruled that the use of two

selection devices — a standard intelligence test and a high school

diploma requirement — violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 because the devices excluded blacks from consideration for

jobs at a higher rate than they excluded whites (an occurrance

referred to as "adverse impact" or "disparate treatment" in fair

employment cases), and had not been shown to be job related, that

is they did not "measure the person for the job," but only measured

"the person in the abstract." 401 U.S. at 436. The Supreme Court

stated that,

The objective of Congress in the enactment of Title VII

is plain from the language of the statute. It was to

achieve equality of employment opportunities and remove

barriers that have operated in the past to favor an

identifiable group of white employees over other

employees. Under the Act, practices, procedures, or

tests neutral on their face, and even neutral in

terms of intent cannot be maintained if they operate'

to ’freeze' the status quo of prior discriminatory

practices. 401 U.S. at 429-30.

The Supreme Court further commented on issues directly relevant to

the legality of the PACE that,

Congress has now provided that tests or criteria for

employment or promotion may not provide equality of opportunity merely in the sense of the fabled offer of

milk for the stork and the fox. On the contrary,

- 18 -

Congress has now required that the posture and

condition of the job seeker be taken into account...

The Act proscribes not only overt discrimination but

also practices that are fair in form but discriminatory

in operation. The touchstone is business necessity. If

an employment practice which excludes Negroes cannot be

shown to be related to job performance, the practice

is prohibited. 401 U.S. at 431.

The facts of this case demonstrate the inadequacy of

broad and general testing as well as the informality

of using diplomas or degrees as fixed measures of

capability. History is filled with examples of men

and women who rendered highly effective performance

without the conventional badges of accomplishment in

terms of certificates, diplomas, or degrees. Diplomas

and tests are useful servants but Congress has mandated

the common-sense proposition that they are not to become

masters of reality. 401 U.S. at 433.

Within one year after the decision in Griggs, Congress amended

Title VII to apply to employment in the federal government. Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub L 92-261, 86 Stat 103. The

House and Senate Committee Reports made clear in amending Title VII

that the Supreme Court properly interpreted the statute in Griggs.

Moreover, the Committees expressed their particular concern that the

selection methods used by the Civil Service Commission (now the Office

of Personnel Management) be re-examined to ensure that they meet the

Griggs standards.

Civil Service selection and promotion techniques

and requirements are replete with artificial re

quirements that place a premium on "paper" cre

dentials. Similar requirements in the private

sectors of business have often proven of questionable

value in predicting job performance and have often

resulted in perpetuating existing patterns of dis

crimination .... The inevitable consequence of this

kind of a technique in Federal employment, as it has

been in the private sector, is that classes of persons

who are socio-economically or educationally dis

advantaged suffer a very heavy burden in trying to

meet such artificial qualifications.

It is in these and other areas where discrimination

is institutional, rather than merely a matter of bad

- 19 -

faith, that corrective measures appear to be urgently-

required. For example, the Committee expects the

Civil Service Commission to undertake a thorough re

examination of its entire testing and qualification

program to ensure that the standards enunciated in the

Griggs case are fully met. S. Rep. No. 92-412 (92nd

Cong., 1st. Sess. 1971) pp. 14-15.

The House report was particularly critical of testing pro

cedures which are like the PACE.

Civil Service selection and promotion requirements are

replete with artificial selection and promotion require

ments that place a premium on "paper" credentials which

frequently proveaf questionable value as a means of pre

dicting actual job performance. The problem is further aggravated by the agency's use of general ability tests

which are not aimed to any direct relationship to specific

jobs. The inevitable consequence of this, as demonstrated

by similar practices in the private sector, and, found

unlawful by the Supreme Court, is that classes of persons

who are culturally or educationally disadvantaged are

subjected to a heavier burden in seeking employment.

(emphasis added) H. Rep. No. 92-238 (92nd Cong., 1st

Sess. 1971) p.24.

The principles in Griggs were reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in

Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) (standardized test

that excluded blacks disproportionately); and Dothard v. Rawlinson,

433 U.S. 321 (1977), (height and weight requirements that excluded

women disproportionately). In Albemarle Paper Co., the Court elaborat

ed on Griggs and addressed particularly the burden that must be met by

an employer once disparate impact has been shown. An employer may

not rest upon generalized or unsupported opinions but rather must

prove that the test has been validated and properly used according

to accepted norms of the profession. In determining the proper

norms, the Court in Albemarle Paper Co. relied upon the Guidelines

established by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission which

- 20 -

were in turn based upon the standards published by the American

5__/

Psychological Association. Subsequently, after an extensive

comment period and a thorough study by four departments of the

6 /federal government charged with reviewing employment practices,

the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures were

promulgated, 33 Fed. Reg. 38290 (1978).

The EEOC Guidelines and now the Uniform Guidelines have been

repeatedly relied upon by the lower courts. For example, the Justice

Department has used the Uniform Guidelines as a measure for deter

mining the legality of the selection practices of local governments /

and Courts of Appeal have strictly applied the Uniform Guidelines at

the Department's request. See e.g., Ensley Branch of the NAACP v.

Seibels. 616 F.2d 812 (5th Cir. 1980); Firefighters Institute v. St.

Louis. 616 F.2d 350 (8th Cir. 1980).

Even if the employer demonstrates that a device is job related

and used appropriately that does not end the inquiry. Even if the

employer has shown the validity of a selection device the plaintiff

may prevail if the plaintiff establishes "that other tests or

selection devices, without a similarly undesirable racial effect,

would also serve the employer's legitimate interest in efficient

and trustworthy workmanship." Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra,

422 U.S. at 425.

As we describe in section D there is compelling evidence and

argument that the PACE does not pass muster under these well-established

5 / Standards for Educational & Psychological Tests, (American Psycholo

gical Association, Inc. 1974).

6 / Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Department of Labor,

Justice Department and the Civil Service Commission.

21

principles. In the likely possibility that the Court declares the

PACE unlawful, the Court would impose compensatory and corrective

relief. In similar circumstances courts have imposed a variety

of remedies, including the immediate cessation of the test, the

use of interim selection procedures, the establishment of hiring

goals that will correct for the discriminatory effects of the test,

and back pay to the entire class of minorities who were harmed by

the test, see section III, B.

C. Discriminatory Effect

The PACE written test has a substantial adverse impact upon

blacks and Hispanics.

An analysis of data collected by OPM from a sample of test-

takers from the January 1978 administration of the PACE and from all

test-takers during the April 1978 administration shows:

Whites Blacks Hispanics

Total number taking the PACE 45,539 6,488 2,694

Number achieving unaugmented score

of 70 or above 19,177 323 347

% of total 42.1% 5.0% 12.9%

Number achieving augmented score

of 70 or above 21,343 940 518

% of total 46.9% 14.5% 19.2%

Number achieving unaugmented score

of 90 or above 3,861 17 40

% of total 8.5% 0.3% 1 .5%

Number achieving augmented score of

90 or above 6,030 42 69

% of total 13.2% 0.6% 2.6%

Only 42 or .6% out of 6,488 blacks who took the 1978 test scored

90 or above while 6,030 or 13.2% of 45,539 whites who took the 1978

22

test scored 90 or above. Since a score of 90 or above is necessary

for consideration for many jobs, see p. 16 / supra, the PACE has a

severe adverse impact and in fact operates to exclude blacks from

consideration for many jobs.

Moreover, the study undertaken in San Francisco regarding the

impact of the PACE upon Hispanics, blacks, and Filipinos supports

the conclusion that the PACE has a severe adverse impact. Finally,

there is expert opinion that a test constructed like the PACE will

"maximize scoring differences between whites and minorities," see

p. 3 , supra, in fact Dr. Barrett correctly predicted that the PACE

would have a severe adverse impact upon minorities, see p. 9,

supra.

23

D. Lack of Justification

The issue regarding whether the Government has demonstrated

that the PACE is job related and appropriately used requires sub

stantial and detailed discussion. In this Memorandum we attempt only

to describe briefly the many reasons which support the conclusion

that the PACE is neither job related nor appropriately used.

1. Description of the PACE Test

The written test component of PACE is a cognitive ability

test. It is designed to measure five cognitive abilities: Deduction,2/Induction, Judgment, Number, and Verbal Comprehension. All applicants

for the entire 118 occupational job categories take the identical test

regardless of the particular job or jobs in which they are interested.

The test questions are selected solely for their alleged relevance to

one of the five cognitive abilities. It is important to emphasize

that this test is designed to measure these general cognitive

abilities and it is not designed to measure actual job knowledge or

skill required for a specific job. Unlike a test for selecting an

electrician which might question the applicant's knowledge of

electrical wiring or even ask the applicant to perform a parti

cular electrical repair, or a test for admission to the bar which

might question an applicant's knowledge of local court procedure,

the questions on the PACE test are not selected on the basis of

any direct observation of the actual duties of the job. The PACE

test is described in some detail in Dr. Barrett's affidavits, see

p. 9, supra, ( sample questions from the PACE are included in an ex

hibit to Dr. Barrett's affidavit, attached as Appendix B).

7/ These terms are merely labels for the abilities; the Government's

description of these abilities is set forth on pp. 6-7 of the Plain

tiffs’ Trial Brief in Ellis, Appendix C.

2. General Problems

The major problems with the Government’s attempted justi

fication for the PACE are listed in Dr. Burns' letter to the N.Y.

Times, Appendix A:

Like many other overbroad tests...

[the PACE] chooses the best general

test-takers, not necessarily the best

workers for specific jobs. A single

test can't be expected to properly

evaluate "merit" for 118 different

jobs ranging from Bond Sales Pro

motion through Digital Computer

System Administration to Outdoor

Recreation Specialist. The use of

PACE, with insignificant variations,

for all these jobs is patently

absurd. PACE purports to test a

number of skills such as numerical

ability and deductive reasoning

yet its different questions all

come " packaged" in complex verbal

puzzles. It is more similar to

the Graduate Record Exam used to

admit students to Ph.D. programs

than it is to employment tests

used in the private sector. The

PACE is the kind of test that

discriminates most severely....

Perhaps an analogy may help to explain at least in

part the difficulty with justifying the PACE. Let us assume the

following situation. A large private employer with vacancies in

over 100 different white-collar positions in different plants

scattered across the country wants to recruit college graduates.

The employer decides to base his selection solely upon the scores

obtained by the applicants on the Graduate Record Examination. The

applicants are ranked on the basis of these scores and the personnel

managers in the employer's plants throughout the country must select

in the order of this ranking. The employer ignored and refused to

25

consider the applicants' achievements in college, their job or

other experiences, interviews or recommendations. Of course, no

private employer would follow such an arbitrary plan. Yet, in

effect, the Government follows a similar plan in using the PACE.

Without delving into too much detail, we set forth four

basic arguments which plaintiffs would advance in court and which in

other cases have led to judicial determinations that tests were unlawfully

8/used: (a) construct validity was improperly used; (b) "ranking" of

candidates was not justified; (c) the existence of "unfairness" of

the PACE to blacks and Hispanics was not investigated; and (d) the

Government did not properly consider alternatives to the PACE which

would have less or no adverse impact.

8/ In Appendices B and C more technical arguments regarding the

validity of the PACE are set forth.

It should be noted that Alan K. Campbell, Director, Office of

Personnel Management and the defendant in this lawsuit, testified

in May 1979 before a House Subcommittee on Civil Service, chaired by

Rep. Patricia Schroeder (D-Colorado). He stated several reasons

supporting the validity of PACE. However, Mr. Campbell further

stated that "we are nevertheless deeply concerned about the adverse

impact of any component of the total selection process ... and will

continue to press to reduce or eliminate this impact, especially

through searching for alternatives to measure job-related qualifi

cations ."

a. Construct validity. The Government chose to show

the job relationship of the PACE through the use of construct

9/validity. Unlike content validity which demonstrates that

a test measures the knowledge or skill for a particular job

(like a test for an electrician or a bar exam) or criterion-

related validity which demonstrates by empirical evidence that

a test measures job performance, construct validity i3 based

upon inferences and hypotheses. In developing construct

validity, one must hypothesize that a particular item (question)

measures the construct (for example, judgment) and that the

construct is a measure of job performance. In itself the proper

measurement of a construct such as judgment may be difficult and

10/

inconclusive. Construct validity was developed in the field

of educational psychology and only recently applied to the field

97 see p. 10 n. 2 for a definition of the three strategies for

validity.

The 0PM defines construct validity in the following manner:

"Construct validity requires hypothesizing of various psychological

constructs important for performance both on the test and on the

criterion; the development of measures of these constructs; and

the gathering of evidence to support both the relationship of the

predictor and the criterion via the constructs as well as to

explicate the constructs themselves." The Professional and

Administrative Career Examination: Research and Development, United

States Civil Service Commission (1977), p.5.

10/ For example, a research report prepared by the Civil Service

Commission in its investigation of the validity of the PACE states

that "empirical evidence for a Judgement factor, although present

in the literature, is relatively weak and inconsistent. This,

of course, made it difficult to find item types which could

reasonably be expected to tap an ability called judgment," (emphasis

added). Experimental Item Types to Measure Judgment, United States

Civil Service Commission (1977), p. 8.

27

of employment. Accordingly, the Uniform Guidelines provide as

follows:

Construct validity is a more complex

strategy than either criterion-related

or content validity. Construct validation

is a relatively new and developing procedure

in the employment field, and there is at

present a lack of substantial literature

extending the concept to employment practices.

The user should be aware that the effort to

obtain sufficient empirical support for

construct validity is both an extensive and

arduous effort.... Users choosing to justify

use of a selection procedure by this strategy

should therefore take particular care to

assure that the validity study meets the

standards set forth below. Section 14D(1).

The standards which users should take "particular care"

to meet include demonstrating by empirical evidence (criterion-

related studies) that the test measures job performance and

showing by a job analysis the "work behavior[s] required for

successful performance of the job ... and an identification of the

construct(s) believed to underlie successful performance of these

critical or important work behaviors in the job or jobs in question.

OPM only performed job analyses for 27 and empirical

studies for 4 of the 118 job categories for which the PACE is

used. This performance does not comply with the requirement that

OPM "take particular care to assure that the validity study meets

the standards ...." Moreover, the job analyses performed by the

OPM showed that many of the jobs, skills and abilities which were

thought important for job performance, such as the ability to

interact properly with people, were not tested by the PACE, see

e.g. Appendix C, pp. 27-30. The failure to measure a significant

part of a job may seriously undermine a claim as to the validity

of a selection instrument, see e.g. Firefighters Institute v,

Pity of st. Louis. 549 F.2d 506 (8th Cir.), cert, denied,

28

434 U.S. 819 (1977). The point was well made by Rep.

Patricia Schroeder after the hearings on the PACE by the

Subcommittee on Civil Service:

The subcommittee will continue to examine

hiring for Federal jobs to assure that

the twin goals of equal employment opportunity

and merit selection are met. We need civil

servants who cannot only handle paperwork

but who have the heart and soul to serve

the public with sensitivity. Press Release,

May 23, 1979.

Since the methodology of OPM did not meet the standards

of the Uniform Guidelines, the claim of construct validity would

not be upheld. See Douglas v. Hampton, discussed at pp.10-11,

supra .

b. Ranking. The PACE is used to rank-order applicants;

thus, if a person scores one point higher than another person

it is assumed that the higher-scoring person is more qualified,

see pp.15-16. supra.

The Guidelines state that a cutoff score

"should normally be set so as to be reasonable

and consistent with normal expectations of

acceptable proficiency within the work force."

Guidelines §5(H). This also makes sense. No

matter how valid the exam, it is the cutoff

score that ultimately determines whether a

person passes or fails [or when there is

ranking whether a person is selected]. A

cutoff score unrelated to job performance may

well lead to the rejection of applicants who

were capable of performing the job. When a

cutoff score unrelated to job performance

produces disparate racial results, Title VII

is violated.

Guardians Ass'n of New York v. Civil Service Commission

of New York, 630 F.2d 79, 105 (2nd Cir. 1980). The "Questions and

11/Answers" which provide interpretation for the Uniform

11/ The Questions and Answers were adopted by the four agencies

which promulgated the Uniform Guidelines. Their intent is to

"interpret and clarify, but not to modify, the provisions of the

Guidelines." 44 Fed. Reg. 11, 966 (1979).

29

Guidelines state:

Criterion-related and construct validity

strategies are essentially empirical....

To justify ranking under such validity

strategies, therefore, the user need show

mathematical support for the proposition

that persons who receive higher scores on

the procedure are likely to perform better

on the job. Question and Answer No. 62,

44 Fed. Reg. 12,005 (1979).

The OPM has not met the required standard for ranking

persons by use of the PACE. Even if the use of the PACE may

be shown to be valid for some purpose, it has not been shown to

be valid for the use to which it was put, ranking, and therefore,

the PACE has been used unlawfully. Guardians Ass'n of New York v.

Civil Service Commission of New York, supra; Ensley Branch of

the NAACP v. Siebels, supra, 616 F.2d at 822; Firefighters

Institute v. City of St. Louis, supra, 616 F.2d at 357-58.

c. Fairness. "When a specific score on a selection

procedure has a different meaning in terms of expected job performance

for members of one race... than the same score does for members of

another group, the use of that selection procedure may be unfair

for members of one of the groups." Question and Answer No. 62,

supra. The Uniform Guidelines require a user to investigate the

question of fairness whenever feasible. Section 14B(8). It was

feasible for OPM to investigate the question of fairness yet

OPM did not investigate fairness. In Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

supra, 422 U.S. at 433-36, the Supreme Court indicated that a

validation study was "materially deficient" because among other

reasons the study did not include an investigation of fairness

where it was not shown to be unfeasible to do so. See also,

U.S. v. Georgia Paper Co., 474 F.2d 906, 914 (5th Cir. 1973);

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340, 1350 (8th Cir.

1 975: Kirkland v. New York State Department of Correctional Services,

30

628 F .2d 796, 798-99 (2nd Cir. 1980). Moreover, the Standards

for Educational and Psychological Tests, published by the

American Psychological Association (Wash., D.C. 1974) provide for

the investigation of test fairness, pp. 43-44.

d. Failure to consider alternatives. Even if the

PACE is valid and even if it were appropriately used for ranking,

the PACE is still unlawful if the plaintiffs establish "that other

tests or selection devices, without a similarly undesirable racial

effect, would also serve the employer's legitimate interest in

efficient and trustworthy workmanship", Albermarle Paper Company v.

Moody, supra, 42 U.S. at 425. As Dr. Burns stated "the PACE

is the kind of test that discriminates most severely," Appendix

A. In any case, the Uniform Guidelines require "a user when

conducting a validity study, to make a reasonable effort to become

aware of suitable alternative selection procedures and methods of

use which have as little adverse impact as possible, and to inves

tigate those which are suitable. Section 3B." Question and

Answer No. 48, supra. In devising and using the PACE, a test

which maximizes adverse impact, the Government failed to comply

with this provision in the Uniform Guidelines.

31

III. THE SOLUTIONS: PROVISIONS IN THE CONSENT DECREE?

REMEDY THAT WOULD BE AVAILABLE IF THE PLAINTIFFS

PREVAIL IN COURT

A. Provisions in the Consent Decree

The Consent Decree is a detailed, 48-page document which

took 21 months to negotiate, see pp. 5-7, supra. The purpose of

this outline is not to re-state or interpret the Decree but rather

to provide some guidance for reading and understanding the Decree.

The provisions of the Decree are fully in accord with

Title VII law and impose substantially less stringent requirements

upon the Government than are frequently imposed by the courts or

which are contained in other consent decrees. The provisions of

the Decree reflect the compromise that developed during the months

of bargaining. As is pointed out in some detail in section B, the

plaintiffs have given up several remedies which may have been

imposed by the Court if the case had proceeded to trial. The pro

visions of the Decree are as follows:

1. The use of the PACE will be phased out gradually. By

12/

January 1, 1984, the PACE will no longer be used. Decree, paragraph

13(a).

2. The District Court retains jurisdiction over this case.

The Court retains jurisdiction with respect to any of the 118 job

12/ If the case had proceeded to trial the Court may have ordered the

government to cease using the PACE immediately, see p. 37 , infra? or,

if this were not possible, the Court may have ordered the Government to

use the PACE in a manner which would insure that the PACE would not

exclude proportionately more minorities than non-Hispanic whites, id.

This latter remedy is substantially more strict than the provision in

the Decree, which provides that the Government use "all practicable

efforts" to remove the adverse impact of the PACE through the use of special programs. Decree, paragraph 16.

32

categories for which the PACE was used for a period of five years

after the cessation of the use of PACE results and the implementation

of an alternative examining procedure for that job category. Decree,

paragraph 7. Since the use of the PACE will be completely phased

out by January 1, 1984, the Court's jurisdiction will terminate by

January 1, 1989. However, for job categories for which there are

presently alternative examining procedures, the Court's jurisdiction

will terminate in 1986.

3. During the period of interim use of the PACE or during

the retention of jurisdiction, agencies must use "all practicable

efforts" to remove "adverse impact" which may result from the use of

the PACE or the alternative examining procedure through the use

13/of special programs. Decree, paragraph 16. The special programs

include the modification and use of existing programs: the Out

standing Scholar program under which a college graduate who obtained

a grade point average of 3.5 or higher on a 4.0 scale or who stands

in the upper 10% of the graduating class may be hired without competi

tion, Decree, paragraph 16(a); certification of applicants with bi

lingual and/or bicultural skills for hire into PACE jobs where inter

action with the public or job performance would be enhanced by these

skills, Decree, paragraph 16(b); College Co-op and other work study

programs in which student participants who successfully complete the

programs may be hired without competition, Decree, paragraph 16(c).

4. The Decree provides that neither the special programs

for removing "adverse impact" nor anything else in the Decree "shall

be interpreted as requiring any Federal agency to hire any person

for a job who is unqualified...." Decree, paragraph 12(k).

1 3/ if the case had proceeded to trial the Court may have ordered a quota provision to remove adverse impact and also to remedy the dis

criminatory effects of the PACE as quickly as possible. A quota provision would remain in effect until the proportion of minorities

in the pertinent job category equaled the proportion of minorities in

+- W ^ «r C o o W Q 1 Tlf .

33

5. "Adverse impact" is measured by the Decree in a manner

consistent with well-established guidelines set by the courts and

federal agencies. The Supreme Court defined what evidence must be

shown to establish adverse impact and to shift the burden to the

employer to show that the test is "job related." The plaintiff

must demonstrate that "the tests in question select applicants for

hire or promotion in a racial pattern significantly different from

that of the pool of applicants," Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra,

422 U.S. at 425; see also Hazelwood School District v. United States,

433 U.S. 299, 308n. 14 (1977), (the Court applies the concept of statistical

significance to Title VII cases). The Decree provides that adverse

impact will be shown if the difference between the appointment rate for

blacks or for Hispanics and the appointment rate for non-Hispanic whites

is statistically significant at the .05 level of confidence or if the

appointment rate for blacks or for Hispanics is less than 80% of the

appointment rate for non-Hispanic whites. Decree, paragraph 8(b). In

paragraph 4 of the Uniform Guidelines the federal agencies have

established a similar definition of adverse impact.

The term "statistically significant at the .05 level of con-

ficence" means that there is less than a one in twenty (.05) chance

14/

that the disparity occurred as a random or chance event. The 80%

rule permits ready application of the standard by those untrained

to use statistical tests to determine significance. For example,

14/ "Significance levels refer to the risk of error we are willing

to take in drawing conclusions from our data.... Most psychological

research applies at either the .01 or the .05 levels, although other

significance levels may be employed for special reasons." a . Anastasi,

Psychological Testing (London: MacMillan, 3rd ed. 1968), p. 76.

34

if 100 whites and 100 blacks take a test, and 50 whites but only 40

blacks are appointed adverse impact has not been shown since the

appointment rate of blacks is 80% of that of whites.

6. During the period of the retained jurisdiction of the

Court, an agency does not have to use "all practicable efforts" to

remove the adverse impact which may result from an examining pro

cedure for a job category if at least 20% of all incumbents of the

job category are blacks and Hispanics. Decree, paragraph 12(c). In

other words, the Decree provides a "safe harbor" for an agency; if

blacks and Hispanics comprise 20% of the occupants of a job category

then the agency has no obligation to use "all practicable efforts" to

remove adverse impact. The 20% figure is in no way a numerical goal

or quota. Several examples suffice to explain the limited application^

of the 20% figure and the obligation to use "all practicable efforts":

a. If a job category has 7% blacks and Hispanics, the

proportion of black and Hispanic applicants is 10%^ and it has

an appointment rate of blacks and Hispanics of 10%, the agency

would have no obligation to use "all practicable efforts" since

there is no adverse impact even though the selection rate and

the minority proportion of incumbents is substantially below

20%. See Decree, paragraph 12 (b) .

b. If at the end of the period of jurisdiction, the minority

proportion of the incumbents remains at 7% and the examining procedure

15/ The remedial provision is substantially less stringent than the

quota provisions routinely applied by the courts, see pp. 38-39 , infra.

35

has an adverse impact, the agency would have no obligation under the

Decree to use "all practicable efforts" to remove adverse impact even

though the minority proportion of incumbents is substantially below

20%. Of course, an agency would remain obligated by Title VII to

use lawfully any selection procedure.

7. The Government will cease using the PACE test in the

16/

selection of employees for promotion.

8. The four named plaintiffs will receive a total of

17/$35,000. Decree, paragraph 20. Also any class member who has

taken the PACE and filed an administrative charge which is still

pending will receive $3,000 in full settlement. (OPM has been

unable to find any non-plaintiff class members who have pending

charges). Decree, paragraph 21.

9. The Decree provides reporting and monitoring require

ments in order to ensure that information will go to plaintiffs and

the Court regarding the Government1s compliance with the Decree and

development of alternative examining procedures to the PACE. See

e.g., Decree, paragraphs 23-31. The Decree emphasizes cooperative

efforts between the parties to attempt to resolve any problems with

the Decree's implementation. See e.g., Decree, paragraphs 12(e) (f),

17-18.

16/ If the case proceeded to trial the Court may have ordered .preferential promotional rights for all class members who were denied

a promotion because of the use of the PACE. See pp. 40, infra.

17/ If the plaintiffs prevailed at trial the class which includes

thousands of individuals would be entitled to receive back pay. See

pp. 40-41» infra. This amount of back pay could total millions of dollars.

36

B. Remedy Available after Litigation

A brief review of the principles for applying a judicially-

imposed remedy when violations of Title VII are determined makes it

apparent that the remedy provided in the Consent Decree is moderate

and appropriate and that if plaintiffs prevailed in litigation re

garding the PACE, the Court would,in all likelihood, order far more

extensive remedies than those provided in the Decree.

The Supreme Court has stated that there are two major

objectives of Title VII which courts must consider in determining

an appropriate remedy: "'to eliminate so far as possible the last

vestiges of an unfortunate and ignominious page [employment discrimina

tion] in this country's history’" and "to make persons whole for in

juries suffered on account of unlawful employment discrimination."

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 417-18. Accordingly,

the Supreme Court has stressed "that federal courts are empowered to

fashion such relief as the particular circumstances of a case may

require to effect restitution, making whole insofar as possible the

victims of racial discrimination...." Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., 424 U.S. 747, 764 (1976). In fact, the Supreme Court has inter

preted Title VII to restrict severely the discretion of the federal

courts not to award a full remedy, Albemarle Paper Co. , supra, 422

U. S. at 421 :

. . . given a finding of unlawful dis

crimination, backpay should be denied

only for reasons which, if applied

generally, would not frustrate the

central statutory purposes of eradicating

discrimination throughout the economy

and making persons whole for injuries

suffered through past discrimination.

37

If we apply Title VII remedial law to this case it is

likely that a court would order: (1) immediate cessation of the

use of the PACE or an immediate removal of its adverse impact;

(2) imposition of numerical goals designed to remedy the dis

criminatory effect of the PACE over the past six years; (3) pref

erential promotional rights with constructive seniority for

those individuals who were denied a promotion as a result of the

use of the PACE; and (4) class-wide back pay for those groups of

minorities who were denied hire or promotion because of the use

of the PACE.

1. If the PACE is found unlawful, the Court would enjoin

its further use, see e.g. Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc, v. Beecher,

371 F. Supp. 507, 521 (D. Mass.), aff'd, 504 F. 2d 1017 (1st Cir.

1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 910 (1975), United States v. City of

Chicago, 549 F. 2d 415 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 857 (1977) or

require that it be used in a manner which would eliminate adverse

impact. For example, the Court could order that if the Government

did not have any alternative selection device available and was re

quired to use the PACE, then the Government would have to select

minorities from the PACE register in a manner which would insure

that there would be no adverse impact until a job-related and law

ful selection device is implemented. See e.g. Local 53, Heat Frost

Insulators v. Vogler, 407 F. 2d 1047, 1055 (5th Cir. 1969) (The court

rendered a preliminary injunction which required that minorities

account for 50% of job referrals) ,* Kirkland v. N.Y. Dept, of

Corrections, 628 F. 2d 796, 798 (2nd Cir. 1980) (The court approved a

38

provision under which the test scores of minorities will be augment

ed by 250 points).

2. Where there has been class-based discrimination the 18/

Courts have regularly approved "quotas to correct past discrimina

tory practices". United States v. Lathers, Local 46, 471 F. 2d 408

(2d Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973). These remedial pro

visions generally set an "implementing ratio" and a "goal". (For ex

ample one black applicant will be selected for each white applicant who

is selected until a "goal" such as the minority representation of

the relevant labor force is reached.) The goal is determined by

estimating what the level of minority employment would have been

absent the discrimination. Cf. United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443

U.S. 193, 208 (1979). Moreover, "goals and timetables" have been

regularly used by the United States and other parties to consent

decrees. One example of a nationwide, industry-wide, decree entered

into in 1974 by the Justice Department, Department of Labor

and the EEOC clearly makes the point. United States v. Allegheny-

Ludlum Industries, Inc., Civil Action No. 74-P-339 (N.D. Ala.). This

18/ At least eight Circuits have approved numerical relief to correct

past discriminatory practices. Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc, v. Beecher,

504 F. 2d 1017, 1026 (1st Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 910 (1975);

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530 F. 2d 431 (1st Cir. 1976) (in school desegregation suit one-to-one hiring ratio approved until blacks constitute 20% of the

faculty); United States v. Elevator Constructors, Local 5, 538 F. 2d 1012

(3rd Cir. 1976) (affirmed 23% membership goal and 33% referral quota

based on area of union jurisdiction); NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th

Cir. 1974) (imposition of quota on selection of Alabama State Highway

patrol officers based on minority representation in the workforce); Stamns

v. Detroit Edison, 365 F. Supp. 87, 122-23 (E.D. Mich. 1973), aff'd sub

nom EEOC v. Detroit Edison, 515 F. 2d 301, 317 (6th Cir. 1975) (requiring

Company to hire at ratio of three blacks for every two whites), vac. on

other grounds, 431 U.S. 951 (1977); United States v. City of Chicago,

549 F. 2d 415, 436-37 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 875 (1977)

39

decree which covers approximately 150 plants operated by nine major

steel companies, provides that 50% of those selected for trade and

craft positions must be minorities or females until the goal established

for each plant has been attained. (The goal is determined by analyz

ing the available labor force). Decree, paragraph 10. Finally, the

United States Supreme Court has approved the use of voluntarily-

imposed quotas by private employers, United Steelworkers v. Weber, supra,

and Supreme Courts of three states have approved the enactment of

voluntary affirmative action programs by agencies or departments of

local or state governments. Maehren v. City of Seattle, 92 Wn. 2d 480,

599 P. 2d 1255, 20 FEP Cases 854 (1979); Price v. Civil Service

Commission, Sacremento City, 26 Cal 3d 257, 604 P. 2d 1365, 21 FEP

Cases 1512 (1980); chmill v. City of Pittsburgh, 22 FEP cases 742

(Pa. S. Ct. 1980)? see California Department of Corrections v. Minnick,

No. 79-1213, cert, granted, July 2, 1980.

18/ FOOTNOTE CONTINUED(approved requiring City to appoint at least 16% females and 42% minority

group males to fill patrolman position); United States v. N.L. Industries,

479 F. 2d 354, 377 (8th Cir. 1973); United States v. Ironworkers, Local

86, 443 F. 2d 544, 552-54 (9th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984

(1971).

Two other Circuits have stated that numerical relief in the form

of "quotas" is appropriate in certain circumstances which are present

in Luevano. Compare Kirkland v. New York State Dept, of Correctional

Services, 520 F. 2d 420 (2nd Cir.), reh. denied, 531 F. 2d 5 (1975),

cert, denied, 429 U.S. 823 (1976) with Patterson v. Newspaper Deliverers 1

Union, 514 F. 2d 767, 773-75 (2nd Cir. 1975); Patterson v. American

Tobacco Company, 535 F. 2d 257, 273-75 (4th Cir. 1976), cert, denied,

429 U.S. 920 (1976).

4

3. The plaintiff class in Luevano includes individuals

who were denied the opportunity to promote because of the use of the

PACE, see p. 3, supra. The PACE was not designed or intended to be

used as an instrument for the selection of employees for promotion,

yet agencies have used the PACE in the selection process for promotions

If this use of PACE is ruled unlawful, then class members may have pref

erential remedies. An identifiable class member who was denied a

promotion because of the use of the PACE may have the right to pref

erential selection for the next available vacancy and for placement

in that position with all the seniority or other benefits the class

member would have had if he or she had been selected rather than

rejected when the PACE was used. Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

supra, 424 U.S. at 764-68. Thus, for example in a case involving the

city of Albany, Georgia, blacks who were denied job openings were given

priority consideration for future openings. Johnson v. City of Albany,

413 F. Supp. 782 (D. Ga. 1976), 13 EPD para. 11, 324 (Order).

4. If the use of the PACE is declared unlawful, the entire

plaintiff class would be entitled to an award of back pay which would

place them in the economic position they would have been in but for the

use of the PACE. Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 421.

The Supreme Court in Albemarle Paper Co., specifically rejected as a

defense to the back pay award that the employer was acting in "good

faith," 422 U.S. at 422? moreover, a court may not deny an award of