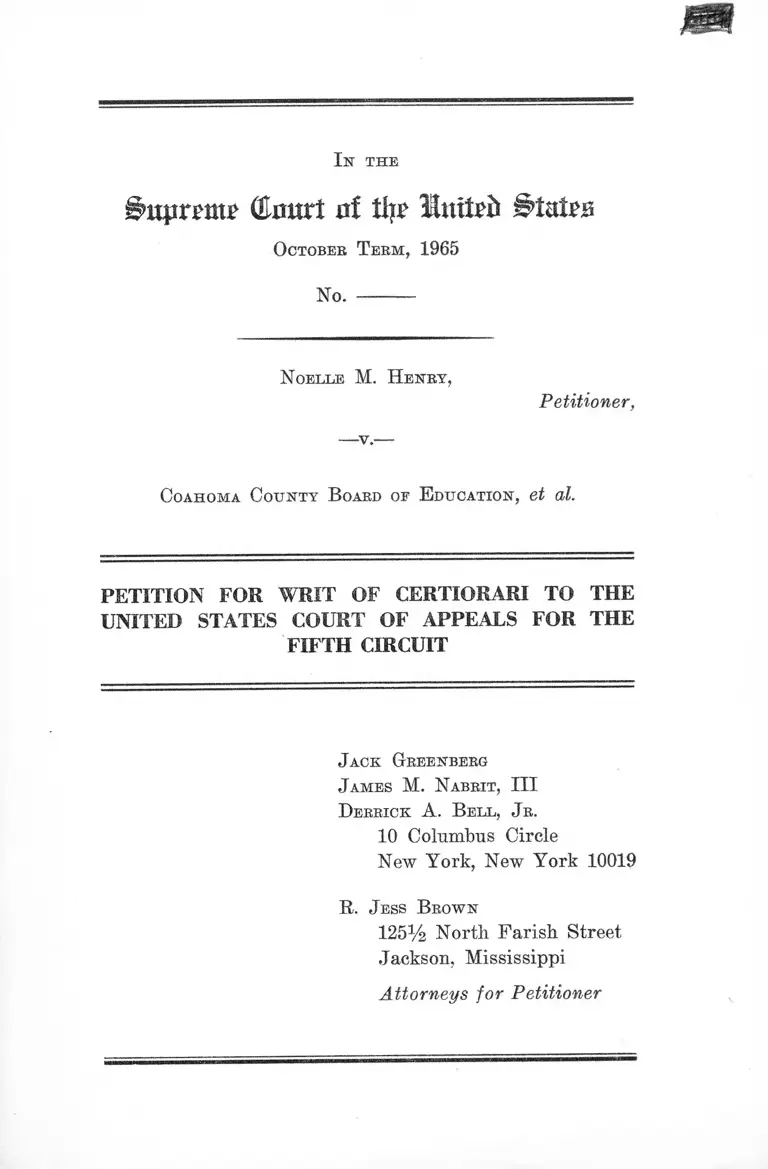

Henry v. Coahoma County Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 4, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Henry v. Coahoma County Board of Education Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1966. 3852abff-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a7963d57-f2d7-480e-bd5c-b4293557062b/henry-v-coahoma-county-board-of-education-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

(Emirt at Hit Unit?!* i ’taliTi

Octobee T eem, 1965

No. --------

Noelle M. H enry,

Petitioner,

—v.—

Coahoma Coxjnty Board of E ducation, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabbit, III

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

R. J ess Brown

125% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

Citations to Opinions Below ......... 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................... 2

Questions Presented ...................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 3

Statement of the Case .................................................. 3

Reasons for Granting the Writ ................................... 8

Introduction ........ 8

I. The Denial of Reemployment to Petitioner

Was Arbitrary and in Violation of Her

Rights Under the Fourteenth Amendment .... 9

II. Petitioner Was Discharged in Violation of

Her Fourteenth Amendment Rights Because

of Her Own Civil Rights Involvement and

Her Husband’s ................................................ 15

Conclusion ................ 21

Appendices :

Appendix A—Statutes ........................ 23

Appendix B—Opinion Below ................................ 27

•—Judgment ....................... 32

•—Order Denying Rehearing ............. 34

PAGE

11

Table of Authorities

Cases:

PAGE

Adler v. Board of Education, 342 U.S. 485 .................. 15

Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 112

F.2d 992 (4th Cir. 1940), cert, den., 311 U.S. 693 ....10,17

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 ......... .......... ...... ...... 18

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360 ............................. ..... 9,10

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F.2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963) .... 20

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103........ —........— 8

Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 (E.D. S.C. 1957),

vacated, 354 U.S. 933 ..............— .......................8,10,17

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278 —.9,10

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F.2d

150 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, den., 368 U.S. 930 ------- 12

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 ......... ............ ...... 18

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U.S. 202 .......... ......................... 17

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

328 F.2d 408 (5th Cir. 1964) ............ ..................... . 20

Frost v. Railroad Commission, 271 U.S. 583 .............. 10

Garner v. Louisiana, 370 U.S. 248 ........... .... .......... — 21

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 .................. ............. 11

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 -------- ---------- 13

Henry v. Collins, 158 So.2d 28 (1963) ........ 5

Henry v. Collins, 380 U.S. 356 _____ ____________ 5,14

Henry v. Mississippi, 154 So.2d 289 (1963) .................. 5

Henry v. Mississippi, 379 U.S. 443 ------------------ -----5,14

Henry v. Pearson, 158 So.2d 695 (1963) ..... 4,5

I l l

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp. 174

PAGE

(M.D. Tenn. 1961) .................................................... 12

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 ........................... 20

Ludley v. Board of Supervisors of L.S.U., 150 F. Supp.

900 (E.D. La. 1957), aff’d 252 F.2d 372 (5th Cir.

1958), cert, den., 358 U.S. 819 ................................ 8

Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962) .......... 21

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343 (5th Cir. 1962), cert.

den., 371 U.S. 828 ..................................................... 20

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 ............... .................... 13

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415.................. ................. 21

Napue v. Illinois, 360 U.S. 264 .......... ........................... 15

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 ............................ 15

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 ................................15,18

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 ........... ................. 20

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 ................................ 15

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 ................................... 18

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153 ................................ 20

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 ....................................... 8

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232 .... 10

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 ..... .............. .2, 8,16,17, 20

Sherbert v. Yerner, 374 U.S. 398 ....... ............... ...... 10

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87 ................. 21

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 ................ ............. 13

Slochower v. Board of Higher Education of the City

of New York, 350 U.S. 551 .................. ......... 9,10,11,13

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513................................... 10

Toreaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 ...... ........ ................ 10

XV

United States v. Brown, 381 U.S. 437 .......................... 13

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U.S. 49 ....................................... 15

Watts v. Seward School Board, 381 U.S. 126 ............. 9

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 .......................9,10,13

Statutes Involved:

Ark. Gen. Ass. of 1958, 2nd Ex. Sess., Act 10 .............. 17

Miss. Code of 1942 Annot., §§2056, 3841.3, 6220.5, 6328-

OS, 9028-31 to 9028-48 .... ........... ............................... 17

Miss. Code of 1942 Annot., §4065.3 .............................. 17

Miss. Code of 1942 Annot., §§6282-41 to 6282-45 ....3,16,17

Miss. Const., Article 8, §207 ......................................... 17

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ....................................... ................ 2

28 U.S.C. §1343(3) ....................... ............... ................ 6

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............................................................ 6

Other Authorities:

PAGE

Brown, Loyalty and Security, Yale Univ. Press. (1958) 15

Government Security and Loyalty, 31:501, GSL News

letter, Bureau of National Affairs (BNA), October

1955 ____________ ________________________ _ 15

N.E.A., “Report of Task Force Appointed to Study

the Problem of Displaced School Personnel Related

to School Desegregation,” (December 1965) ......... 8

Ozmon, “The Plight of the Negro Teacher,” The Amer

ican School Board Journal, September 1965 _____. 8

I n the

Bnpvmxt ( to r t of tf|£ Itmtrft Butts

October Term, 1965

No. --------

N oelle M. H enry ,

— v .—

Petitioner,

Coahoma County Board of E ducation, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

entered in the above-entitled cause on December 3, 1965,

rehearing having been denied on January 4, 1966.

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinion of the District Court is set forth at R. 198,

and reported at 246 F. Supp. 517.1 The opinion of the

Court of Appeals, printed in Appendix B, infra, p. 27, is

reported at 353 F.2d 648. 1

1 The District Court opinion is in the Record printed below, 9 copies

of which have been filed under Rule 21(4).

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered

December 3, 1965. Petition for rehearing was denied

January 4, 1966. This Court’s jurisdiction is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

I.

Whether petitioner, an experienced and capable Negro

public school teacher in Mississippi whose husband is a

prominent civil rights leader, was deprived of rights pro

tected by the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment when she was denied reem

ployment without a hearing, without any statement of the

grounds for the denial, and on the asserted ground that

her husband was a defendant in civil and criminal litiga

tion initiated by state officials (and in which he subse

quently prevailed in this Court), although there was no

showing that petitioner was in any way responsible for

her husband’s alleged acts or that they impaired peti

tioner’s fitness as a teacher?

II.

Whether petitioner was denied reemployment on the

basis of her civil rights affiliations and those of her hus

band in violation of her rights under the due process

and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment,

where she presented substantial evidence establishing this

claim (including the use of an affidavit statute invalidated

in Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479), and the defendants’

general denials included no showing of any reason for the

denial of reemployment which has a rational bearing on

her fitness as a teacher?

3

■ Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States. The statu

tory provisions involved are §§6282-41 to 6282-45, Miss.

Code Annot. 1942. They are printed in Appendix A, infra,

pp. 23-26.

Statement of the Case

Petitioner, Mrs. Noelle Henry, was one of the best teach

ers in the Coahoma County school system (R. 109), and

the only teacher with acknowledged connections with a

civil rights group (R. 114, 129). The School Board was

aware of this through affidavits she submitted listing her

NAACP membership (R. 74-75),2 and because it was com

mon knowledge that her husband, Hr. Aaron Henry, is

State President of the National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People (NAACP) (R. 72, 133).

Petitioner taught for eleven years in Coahoma County

schools (R. 53).3 Teaching classes with from 50 to 71

pupils, she was highly regarded by her principal and her

supervisor (R. 91-92, 98) who, in April 1962, recommended

that she be rehired for the 1962-63 school year (R. 60, 98)

in her $3,450 position as third grade teacher in the all-

Negro McCloud School (R. 54-55). But, although other

teachers recommended by principals and supervisors have

invariably been rehired (R. 71, 103), the Superintendent

announced she would not be offered a new contract (R. 99-

2 The Board’s affidavit requirement complies with a state statute

§§6282-41 to 6282-45 Miss. Code Annot. (1942), enacted in 1956, re

quiring as a condition precedent to employment the annual filing of an

affidavit listing without limitation every organization to which the teaching

applicant belonged or regularly contributed within the preceding five years.

s Prior to this she taught for 5 years in Jackson Mississippi (R. 53).

4

100). The same year petitioner was discharged, three un-

reeommended teachers from her school were rehired and

assigned to different schools (R. 88).

Seeking an explanation, petitioner made three separate

inquiries to the Board and Superintendent (R. 61-62, 65-66,

67-69). Efforts to secure a hearing before the Board failed

(R. 66, 69). Petitioner testified that the Superintendent

denied knowing why she was not rehired, and told her:

Your contract just wasn’t renewed for 1962-63, and he

said I don’t know why the board didn’t renew your

contract; in going over the contracts when they got

to your name they said we don’t choose to renew this

one. They didn’t tell me why and I don’t know why

(R. 62).

But, the Superintendent testified the Board followed his

recommendation (R. 141), denying that it was based on

petitioner’s NAACP membership and activities (R. 140,

162), although on three previous occasions school officials

expressed concern about approving her contract because

of her civil rights connections (R. 111-12, 112-13, 118).

Rather, he asserted (for the first time during the trial)4 *

that he acted on a newspaper report that petitioner’s hus

band was convicted of a misdemeanor involving “morals”

(R. 144), and later advice that petitioner’s husband was

sued for libel by the Prosecutor and Chief of Police who,

Henry charged, “framed” him, retaliating for his civil

rights activities (R. 147).6 Finally, the Superintendent said

he was told that petitioner and her husband “would be”

4 Neither the Answer to the Complaint nor the answers to interroga

tories mentioned any of the grounds subsequently given for petitioner’s

discharge (R. 12-16, 30-33).

6 The opinion below mistakenly states that Mrs. Henry was not re-

employed because of an “adverse judgment” in the libel case (353 F.2d

at 649). But, Mrs. Henry was notified that she would not be re-

5

sued by the plaintiffs in the libel suit to undo an alleged

fraudulent conveyance of property (R. 142). He testified

that the “activities” of petitioner and her husband were

“highly controversial” and that all this litigation would

be “a bad influence on children and other teachers” (R.

141-42).

The Superintendent conceded he made no investigation

concerning the conviction. He did not know there was no

jury trial in the Justice of the Peace Court, or that there

was one in the County Court (R. 144-47). He acted before

the Mississippi Supreme Court reversed the guilty verdict

on June 3, 1963, and although that Court later withdrew

this decision and affirmed on July 12, 1963, the Super

intendent took no action during the interim to reinstate

petitioner (R. 149).* * 6 Asked whether he made any in

vestigation into the basis for the libel charge, the Super

intendent asserted: “It is not my position to dig into

lawsuits. My position doesn’t entitle me to that time”

(R. 164).7

employed on June 4, 1962 (R. 60). The libel trials were held in July

1962 (Henry v. Pearson, 158 So.2d 695, 698).

6 The first opinion of the Supreme Court of Mississippi reversing the

guilty verdict was originally reported as Henry v. State of Mississippi,

154 So.2d 289 (1963). Following a Suggestion of Error submitted by the

Attorney General of Mississippi, the first opinion and judgment were

withdrawn, and a second opinion affirming the judgment of the trial

court is now reported at 154 So.2d 289. On certiorari to this Court the

conviction was vacated because based on illegally obtained evidence and

remanded for a determination as to whether counsel had intentionally

waived the right to object to such evidence. Henry v. Mississippi, 379

U.S. 443 (1965). To date, no action to obtain such a determination has

been taken by the state courts.

7 The libel suits filed against petitioner’s husband by the Clarksdale

Chief of Police, Benford Collins, and the Coahoma County Attorney

Thomas H. Pearson resulted in judgments against petitioner for $40,000.

These were affirmed by the Mississippi Supreme Court. Henry V. Collins,

158 So.2d 28 (1963) ; Henry v. Pearson, 158 So.2d 695 (1963), but were

reversed by this Court. Henry V. Collins, 380 CJ.S. 356 (1965).

6

Petitioner filed this suit against the Board and Super

intendent in October 1962 in the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Mississippi. Federal

jurisdiction and the claim for injunctive relief were

founded on 28 U.S.C. §1343(3) and 42 U.S.C. §1983. Hav

ing failed to obtain any information on the basis for her

dismissal from the Board or its Superintendent, she al

leged the discharge was caused by her NAACP member

ship and her husband’s civil rights activity (R. 2, 7).

The trial court sustained all objections (R. 164-65, 167-72)

to questions aimed at ascertaining whether growing civil

rights activity in the State influenced the decision to

replace petitioner (R. 151-52). Nevertheless, in dismissing

the complaint it ruled that petitioner failed to sustain her

burden of proving that she was discharged for NAACP

membership, associations and activities (R. 204).

Following the Superintendent’s assertion at trial that

he refused to rehire petitioner because her husband was in

litigation, petitioner’s counsel, pursuant to Rule 15(h)

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, moved to amend the

complaint to conform to this evidence, asserting in the

proposed amendment that these reasons were as uncon

stitutional as those alleged originally (R. 193-97). Denying

petitioner’s motion to amend, the trial court nevertheless

wrote that the Superintendent was not arbitrary but “had

good cause and exercised a sound discretion” (R. 202-04),

in dismissing petitioner if, in his opinion, her husband be

came notorious in the community. The court agreed that

petitioner was “tarred with the same brush” by reason of

her marriage and might eventually become personally and

unfavorably involved (R. 203). Because she was not re-

hired, the trial court deemed petitioner a “non-teacher”

lacking standing to question the validity of statutes re

quiring the filing of membership affidavits (R. 207).

7

The Fifth Circuit affirmed per curiam and adopted the

trial court’s opinion. Judge Brown, concurring, emphasized

that the broad discretion of school officials in hiring teach

ers cannot be used to interfere with, or discourage the

exercise of, federally secured civil rights. A teacher’s hus

band’s criminal record and involvement in litigation, ac

cording to Judge Brown, “in many cases may justify a

refusal to recommend her for this sensitive employment. . . ”

(App. p. 31). However, if such record and involvement

spring solely from attempts to exercise civil rights, such

circumstances would not justify a refusal to recommend.

In Judge Brown’s view, petitioner failed to prove that the

Superintendent’s refusal to recommend her was based on

her civil rights activities or her husband’s, or that his

involvement in criminal and civil litigation arose from

constitutionally protected assertions of civil rights.

On rehearing, petitioner pointed out that the trial court

would not permit her to show that the Superintendent

knew that community sentiment opposed school desegrega

tion or that civil rights leaders like petitioner’s husband

frequently are charged with violating criminal laws, but

that such prosecutions, while designed to deter civil rights

activity seldom, if ever, expressly charge violation of

segregation laws; rather, they run the gamut of other

criminal statutes.

The Fifth Circuit denied petitioner’s petition for re

hearing on January 4, 1966.

8

Seasons for Granting the Writ

Introduction

This case presents questions of substantial public im

portance, involving a claim of arbitrary and discriminatory

denial of public employment contrary to principles declared

by this Court. It involves a Negro school teacher denied

reemployment in the context of the struggle for public

school desegregation in Mississippi. The problems of

Negro teachers displaced by discrimination during the de

segregation process8 or discharged in reprisal for their

opposition to segregation9 are matters of national concern.

This Court has seen fit to closely scrutinize cases touching

on the rights of Negro teachers in relation to school de

segregation. Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.8. 479; Bryan v.

Austin, 354 U.S. 933; Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S.

103; Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198. As Mr. Justice Harlan

wrote dissenting in Shelton (364 U.S. at 496-97), “pro

tection [of constitutional rights] in the context of the

racial situation in various parts of the country demands

the unremitting vigilance of the courts.”

The case involves issues similar to those decided by this

Court in a variety of other cases involving First Amend

ment claims of teachers and, we submit, a conflict with the

8 The National Education Association has sponsored a detailed study

of the problem. See “Report of Task Force Appointed to Study the

Problem of Displaced School Personnel Related to School Desegregation

and the Employment Studies of Recently Prepared Negro College Grad

uates Certified to Teach in 17 States”, December, 1965. See also, Ozmon,

“The Plight of the Negro Teacher”, The American School Board Journal,

pp. 13-14, September, 1965.

9 See Bryan v. Austin, 354 U.S. 933, vacating 148 F. Supp. 563 (E.D.

S.C. 1957); Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479; Ludley v. Board of Super

visors of L.S.V., 150 F. Supp. 900 (E.D. La. 1957), aff’d 252 F.2d 372

(5th Cir. 1958), cert, den., 358 U.S. 819.

9

principles decided in those cases. Wieman v. Updegraff,

344 U.S. 183; Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368

U.S. 278; Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360; Slochower v.

Board of Higher Education of the City of New York, 350

U.S. 551.

Recently the Court granted certiorari in a case involving

the right of a school board to dismiss a teacher in retalia

tion for the exercise of asserted First Amendment rights,

but vacated the judgment when the cause was affected by

supervening legislation. See Watts v. Seward School Board,

381 U.S. 126, where school teachers were dismissed for

“immorality” consisting of their having urged the ouster

of the Superintendent and the Board. This Court vacated

and remanded for reconsideration in light of newT legisla

tion barring school boards from interpreting “immorality”

to restrict the right to criticize school officials.

I.

The Denial of Reemployment to Petitioner Was Arbi

trary and in Violation of Her Rights under the Four

teenth Amendment.

Petitioner has contended that the school authorities

merely used her husband’s difficulties to screen the real

reason for her dismissal, which was to combat NA A CP

sponsored school desegregation efforts. But assuming

arguendo that the Superintendent’s stated reasons were

the basis for petitioner’s dismissal, we submit that the

stated grounds were arbitrary and unreasonable in viola

tion of her Fourteenth Amendment rights.

This Court clearly has held that a state may not exclude

a person from public employment for reasons which are

“patently arbitrary or discriminatory.” Wieman v. Upde-

10

\ 9raff> 344 U.S. 183, 192; Cramp v. Board of Public Instruc-

) tion, 368 U.S. 278, 288; Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488,

495-96; Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360; Schware v. Board

of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232; Slochower v. Board of

Higher Education of the City of New York, 350 U.S. 551.

We submit that the actions of the Coahoma County school

officials in denying Mrs. Henry reemployment were indeed

patently arbitrary and unfair. Before detailing this, it

ought to be noted that while in a formal sense the action

of the authorities was to refuse to rehire petitioner, this

action, placed in its context, is tantamount to dismissing

her from her job. She had held her job eleven years, and

her principal and supervisor recommended that her employ

ment be continued. Such recommendations were invariably

followed and thus reemployment was more or less auto

matic or routine until petitioner’s case. See Judge Parker’s

dissent in Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563, 572-73 (E.D.

.S.C. 1957), vacated, 354 U.S. 933. But the school officials’

/ action violated the Fourteenth Amendment whether it is

\ viewed as a job dismissal or as a rejection of an appli-

\ cation for public employment. In neither context can the

I State impose unconstitutional conditions upon the oppor

tunity to hold public employment. Cf. Alston v. School

Board of the City of Norfolk, 112 F.2d 992, 997 (4th Cir.

1 1940), cert. den. 311 U.S. 693; Frost Trucking Co. v. Ra.il-

I road Comm., 271 U.S. 583, 594; Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S.

513; Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398.

Mrs. Henry was denied reemployment without any notice

of the charges against her. Her repeated attempts to learn

the ground for the action were unavailing. Consequently,

she had no opportunity to explain or refute the charges

against her, and no opportunity to attempt to show that

the accusations were untrue or had no bearing on her

fitness. Her requests for a hearing were denied. The

11

Superintendent informed himself of the facts solely by

newspaper accounts (R. 144), and conversations with the

lawyer representing Mr, Henry’s adversaries in a libel

suit (R. 144, 147).

The denial of notice of the charges and a hearing when

petitioner was denied reemployment violate fundamental

conceptions of fairness. This is not a case where a teacher

was denied reemployment because of dissatisfaction with

her job performance. The entitlement to a hearing in such

a case might involve different issues. But the action to

deny Mrs. Henry’s job was taken because the Superin

tendent thought petitioner and her husband were engaged

in “highly controversial” activities (R. 141). Such a charge

is so plainly susceptible of use to hide forbidden purposes

that the minimal protection of notice and a hearing is

compellingly necessary.

As this Court pointed out in Greene v. McElroy, 360

U.S. 474, 496-99, the right to notice and a hearing is funda

mental in certain administrative and regulatory actions as

well as in criminal cases. In Greene the Court said (360

U.S. at 496):

Certain principles have remained relatively immu

table in our jurisprudence. One of these is that where

government action seriously injures an individual,

and the reasonableness of the action depends

on fact findings, the evidence used to prove the Gfov-

ernment’s case must be disclosed to the individual so

that he has an opportunity to show that it is untrue.

In another context, in Slochower v. Board of Higher Edu

cation of the City of New York, 350 U.S. 551, the Court

condemned the summary dismissal of a teacher without

hearing under a statute providing for the discharge with-

12

out notice or hearing of any city employee utilizing the

privilege against self-incrimination. See Dixon v. Alabama

State Board of Education, 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961),

cert. den. 368 U.S. 930, and Knight v. State Board of Edu

cation, 200 F. Supp. 174 (M.D. Tenn. 1961), both holding

that students in state schools had a due process right to

hearings before expulsion.

When the Superintendent finally (midway through the

trial of this case) stated why he did not rehire petitioner,

he gave reasons which, we submit, demonstrate that the

action was arbitrary and unfair. The reasons were that peti

tioner’s husband had been convicted of a morals charge

and had been sued for libel by the Chief of Police and

County Attorney, and that the Superintendent was told

that a suit “would be instigated for setting aside prop

erty to Noelle Henry by her husband to avoid payment on

the libel charge” (E. 142). Thus petitioner was denied re

employment because of a criminal charge and a civil suit

against her husband and because a lawyer threatened to

file a further civil suit involving her property. There was

no claim or showing that Mrs. Henry was in any way

culpable or did any blameworthy act in connection with

any of those cases. There was no claim that she knew of

or could have prevented any of the alleged acts by her

husband. It is quite plain that the denial of reemployment

punished petitioner for the alleged acts of someone else

which she had no power to control or prevent.

We submit that it is fundamentally unfair and a denial

of due process to punish petitioner for the alleged acts of

another. There is no claim that her husband’s troubles

actually impaired petitioner’s performance of her job as

a third grade teacher. Her supervisors recommended that

she be reemployed and had nothing but praise for her

work. We submit that it is not permissible to make an

13

automatic inference or presumption that petitioner was

unfit to teach because her husband was a party to civil

litigation and was convicted of a crime. This presump

tion is no more permissible than was New York’s presump

tion that a teacher who relied on the privilege against

self-incrimination was unfit to teach. Slochower v. Board

of Higher Education of the City of New York, 350 U.S. 551.

The presumption that petitioner was unfit because her

husband was convicted, and had been sued for damages,

and because it was said that she was going to be sued in

the future, is not founded on reason. This punishment of

one for the deeds of another partakes of some of the

characteristics of Bills of Attainder which carried with

them a “ ‘corruption of the blood,’ which meant that the

attainted party’s heirs could not inherit his property” and

sometimes “exclusion of the designated party’s sons from

Parliament.” See United States v. Brown, 381 U.S. 437,

441-42.

The presumption here imputes guilt to the wife from

association with her husband. In Wieman v. Updegraff,

344 U.S. 183, the Court condemned a law which might

punish innocent as well as guilty activity. The Coahoma

County school officials have simply punished petitioner for

innocent activity.

Petitioner would have no assurance that she could re

habilitate herself in the eyes of the school officials even

by so drastic a step as separating from her husband and

seeking a divorce. But we need not stop long to ponder

that because making public employment conditional upon

obtaining a divorce is a flagrant invasion of the right of

free association in marriage. See Griswold v. Connecticut,

381 U.S. 479; cf. Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390, 399;

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 541.

14

We urge that the principle that public employees can

be deprived of their jobs because of the misdemeanors of

their spouses is totally alien to conceptions of fairness

embodied in our law. The principle that public employees

can be fired because private litigants sue their relatives for

damages is even worse. The principle that public employees

can be fired because someone merely threatens to sue them

is preposterous. However sensitive a teacher’s job—and

sensitive it is—there is no justification for conditioning

their employment on events which they can never control

and which have no necessary relation to their fitness.

The injustice of punishing Mrs. Henry because of the

alleged misdeeds of her husband is compounded by the

ironical result that while Mrs. Henry has now been pun

ished for four years, Dr. Henry was saved from criminal

punishment or from paying damages by the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. His criminal con

viction was vacated by this Court in Henry v. Mississippi,

379 U.S. 443, and no further action has been taken since

the case was remanded to the trial court. The libel judg

ments against him were also reversed by this Court in

Henry v. Collins, 380 U.S. 356, and that result mooted the

dispute over an alleged fraudulent conveyance.

The view that Mrs. Henry was “tarred with the same

brush” by reason of her marriage (R. 203) was thought

by the courts below to be sufficient to dispose of the mat

ter. The opinion below did not see fit to mention that all

of the judgments against Dr. Henry had been set aside

by this Court. Thus petitioner was tarred by the brush

of the accusations but denied the benefit of her husband’s

vindication.

The trial court recognized that this case involves the

doctrine of guilt by association and its opinion quotes and

15

relies upon language in Adler v, Board of Education, 342

U.S. 485, which is asserted to sanction that doctrine (R.

203-204). Whatever may be the permissible reach of that

doctrine where knowing and sympathetic association with

subversive groups is involved, surely the permissible scope

of its application must be narrowly circumscribed where

the association is one of marriage or kinship and has no

connection with the alleged antisocial conduct.10

II.

Petitioner Was Discharged in Violation of Her Four

teenth Amendment Rights Because of Her Own Civil

Rights Involvement and Her Husband’s.

The lower courts found petitioner failed to prove “by

a preponderance of the evidence” that the School Board

refused to rehire her because of her civil rights affiliations

and those of her husband. But these findings are con

trary to the record. The issue involves the proper in

ferences to be drawn from known facts which are deter

minative of constitutional rights. This Court has tradi

tionally exercised its power to scrutinize the record and

make its own independent examination of the facts deter

minative of constitutional claims. Napue v. Illinois, 360

U.S. 264, 271-72, and cases collected in Note 4; Watts v.

Indiana, 338 U.S. 49, 50-51; Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S.

587, 589-90; Niemotho v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268, 271;

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354, 358.

10 See Brown, Loyalty and Security, Yale Univ. Press (1958), which

summarizes public resentment to “guilt by relationship” and “guilt by

marriage and kinship” cases when they came to public attention in 1955.

Such cases are reported in Government Security and Loyalty, 31:501-502,

GSL Newsletter, Bureau of National Affairs (BNA), Oct. 1955.

16

Petitioner was an effective teacher (R. 91-92, 98) who,

despite long experience and continuing favorable super

visors’ recommendations (R. 92, 109), had nearly been

refused a teaching contract during 1955, 1956 and 1961,

because of her NAACP affiliation (R. 73, 111-12; 112-13;

118, 133). Petitioner was the only one of 200 teachers

(R. 129) in the system (all assigned to schools on a segre

gated baisis, R. 130) who professed NAACP membership

(R. 113-14), and the only one whose spouse was active in

civil rights efforts (R. 133). The Board replaced peti

tioner with a teacher without teaching experience (R. 151-

52).

The Board obtained its first official knowledge of peti

tioner’s NAACP membership (R. 113) through a teacher

affidavit statute enacted by the Mississippi Legislature in

1956, §§6282-41 to 6282-45, Miss. Code Annot. 1942 vir

tually identical to Arkansas’s provision invalidated in

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 IJ.S. 479 (1960). The law requires

all teaching personnel to submit annually as a condition

precedent to employment, an affidavit listing every organi

zation to which the applicant belonged or regularly con

tributed within the preceding five years. Such a provision,

as this Court held in Shelton v. Tucker, supra, must be

considered against the system of employment in which

teachers are hired on a year to year basis, without job

security beyond the end of each school year (R. 201, 205).

The dangers of the Mississippi law are greater than those

of Arkansas because Mississippi has continued to enforce

its statute after Shelton v. Tucker, supra.11 11

11 Even the dissenters in Shelton indicated their opposition was limited

to the statute’s validity on its face and that proof of abuses in the Act’s

administration would make a different case, 364 U.S. 499. In Mississippi,

state statutes and the Board’s continuing policy of segregation raise a

strong presumption of such abuses.

17

Because of her NAACP listing, the former Superinten

dent wanted to refuse petitioner’s application for a-'contraet

or to subject it to termination on two weeks notice (R. 112-

13) but was persuaded to change his mind. The present

Superintendent, upon reviewing the membership affidavits

in 1960 was shocked by petitioner’s NAACP entry and

had to be persuaded to offer her a contract for the 1960-61

school year (R. 118).12

When in 1962 the Superintendent overruled recommenda

tions by her principal and supervisor that petitioner be

rehired, it upset a long-established practice of honoring

such recommendations (R. 103), but accommodated a

phalanx of Mississippi statutes requiring public school

segregation13 and that public officials resist by all legal

means, the implementation of this Court’s desegregation

decisions.14 The Coahoma County schools were operated

on a completely segregated basis when petitioner was dis-

12 Petitioner’s effort to challenge the Mississippi affidavit statute were

frustrated by the lower court’s ruling that at the time suit was filed she

had not been reliired and was a “non-teacher” (E. 207). This ruling

failed to consider that all persons to whom the membership affidavit re

quirement could possibly apply are “non-teachers” since they are mere

applicants for teaching contracts at the point where the affidavit must

be completed. The Mississippi statute provides, as did the Arkansas pro

vision, th a t: “No . . . teacher shall be employed . . . , until, as a condi

tion precedent to such employment, such . . . , teacher shall have filed

. . . an affidavit. . . . ” Compare §6282-41 Miss. Code Annot. 1942 (p. 23,

infra), with Act 10 of the 2nd Ex. Sess. of Arkansas General Ass. of 1958,

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479, 480, n. 1 (1960). Moreover, petitioner

is clearly in the class affected by this legislation and may challenge the

imposition of this unconstitutional burden upon her without refusing to

sign an affidavit in order to make a test ease. Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U.S.

202 (1958). See also, Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112

F.2d 992, 996-97 (4th Cir. 1940) ; Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563,

572 (E.D. S.C. 1957) (dissent by Judge Parker), vacated, 354 U.S. 933.

13 Section 4065.3 Miss. Code of 1942 Annot., see also Article 8, §207,

Miss. Const,; §§2056, 3841.3, 6220.5, 6328-03 and 9028-31-48 Miss. Code

of 1942 Annot.

14 §4065.3 Miss. Code of 1942 Annot, requires the entire executive

branch of the Government, including “all boards of county superinten

dents of education . . . to prohibit, by any lawful, peaceful and eonsti-

18

missed (R. 130), and the system remained totally segre

gated until January 1966, when two Negro pupils were

admitted to a white school under a plan submitted to the

U. S. Office of Education under the Civil Rights Act of

1964.

Petitioner submits that these facts establish a prima

/ facie case of discrimination because of her NAACP ac

tivities and associations, and the burden shifted to the

| school authorities to produce evidence sufficient to combat

\ the clear inference. Nor could such inferences be overcome

I by the Superintendent’s mere assertions that petitioner’s

I civil rights connections played no part in her dismissal

/ (R. 140) where no reasonable alternative ground for dis

missal having a rational relation to her fitness was put

i forth. Cf. Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958);

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955); Avery v. Georgia,

345 U.S. 559 (1953); Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587

The Superintendent claimed that after learning from a

newspaper article about petitioner’s husband’s difficulties

in March, 1962 (R. 144), he refused to follow the favorable

recommendations of her principal and supervisor. Yet, in

May 1962, he gave no reason to the Supervisor of Negro

Schools why the Board had not renewed her contract

(R. 99). Then, in June, 1962, he told petitioner that it

was not he, but the Board who had refused her applica

tion, and he did not know why they had so acted (R. 62).

Finally, in September, 1962, in answer to petitioner’s re-

tutional means, the implementation of or the compliance with the Integra

tion Decisions of the United States Supreme Court, . . . [citations omitted]

and to prohibit by any lawful, peaceful and constitutional means, the

implementation of any orders, rules or regulations of any board, com

mission or agency of the federal government, based on the supposed au

thority of said Integration Decisions, to cause a mixing or integration

of the white and Negro races in public schools. . . . ”

(1935).

19

quest for a hearing or at least some explanation, the

Superintendent replied, orally and by letter, that no rea

sons had. to. be given and that the action of the Board was

final (R. 68-69). The reasons for discharge were not

mentioned in the defensive pleadings or answers to in

terrogatories. Nothing, except the Superintendent’s bare

assertion, contradicts the proposition that the stated rea

sons for denying reemployment were after-the-fact ration

alizations for the action.

The Superintendent made no investigation of the status

of the criminal charge or the libel suit against petitioner’s

husband (R. 144, 164). He made no investigation of the

rumored fraudulent conveyance (R. 147). Even the Su

preme Court of Mississippi’s reversal of petitioner’s hus

band’s conviction, albeit temporary, had no effect in his

decision (R. 148-49).

The Superintendent claimed his action was based on

concern for the welfare of Negro children (R. 141-42) and

reported that, after receiving complaints from the Negro

supervisor and the Negro community, a Negro principal

was dismissed because of his wife’s alleged “immoral”

conduct (R. 161). The Superintendent gave no details of

that episode. But there is no record of any complaints by

anyone against petitioner. She was informed by her prin

cipal that she would be recommended for the 1962-63

school year on March 21, 1962 (R. 60). Her principal made

no mention of petitioner’s husband’s arrest of March 3,

1962, or his conviction in the Justice of the Peace Court

on March 14, 1962. Obviously, the principal had no doubts

about the irrelevance of her husband’s difficulties to peti

tioner’s worth as a third grade teacher. The high esteem

in which petitioner’s principal, supervisor and the Negro

community continue to hold her demonstrates that the

Superintendent’s fears, upon which the dismissal was pur

portedly based, were unfounded.

20

Respondent’s conduct must be evaluated in the light of

its continued use of an affidavit requirement which this

Court held a serious impairment of the teacher’s right of

free association, Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479, 486, and

Mississippi statutes and policies requiring the Board to

maintain racial segregation. Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d

343 (5th Cir. 1962), cert, den., 371 U.S. 828; Bailey v. Pat

terson, 323 F.2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963); Evers v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 328 F.2d 408 ( 5th Cir.

1964).

In Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343, 360 (5th Cir. 1962),

cert, den., 371 U.S. 828, the Court set standards of review:

“to study the case as a whole, weighing all of the evidence

and rational inferences in order to reach a net result; . . . ”

and “to consider the immediate facts in the light of the

institution’s past and present policy on segregation, as

reflected not only in the evidence but in statutes and regu

lations, history and common knowledge; . . . ” Notwith

standing the State’s strenuous assertions that Meredith’s

application was denied because of (a) an alleged false voter

registration, (b) psychological problems, and (c) a had

character risk, the court, rejected the State’s reasons as

“frivolous” and “trivial”. The Court concluded he was re

jected because of his race. 305 F.2d at 361. Compare

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963); Lom

bard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 (1963); Robinson v. Florida,

378 U.S. 153 (1964).

Similar standards should be applied here. The lower

court’s conclusion that “There are no racial or civil rights

overtones in this record . . . ” (R. 205) flies in the face of

/ what the court has frequently judicially noticed about

' Mississippi’s racial policy under the truism “what every

body knows the court must know.” Meredith v. Fair, supra

\ at 344-45. By its failure to take notice of this policy,

21

and refusal to hear evidence about it, the lower court

condemned this case to “the eerie atmosphere of never-

never land,” Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696, 701 (5th

Cir. 1962). This case should be recognized for what it is—

a punishment of Mrs. Henry for her civil rights views and

her husband’s. Nothing else reasonably accounts for the

fact than an admittedly experienced and capable teacher

has been deprived of an opportunity to work in her pro

fession for four years. We urge the Court to pierce the

veil which disguises this discrimination as was done in

such cases as Garner v. Louisiana, 370 TJ.S. 248; NAACP

v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 445 (Justice Douglas concurring);

and Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87, 99 (Justice

Fortas and the Chief Justice, concurring).

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully

submitted tha t the petition for certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ambs M. Nabrit, III

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

R. J ess Brown

125% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

Attorneys for Petitioner

23

APPENDIX A

Miss. Code Annot. 1942 (Cum. Supp. 1960)

§ 8282-41. Superintendents, principals, and teachers to file

affidavit as to membership in organizations.

No superintendent, principal, or teacher shall be em

ployed or elected in any elementary or secondary school

by the trustees of the district operating such school, and

no instructor, professor or other teacher shall be employed

or elected in any junior college or institution of higher

learning, or other educational institution supported wholly

or in part by public funds, by the trustees or governing

authority thereof until, as a condition precedent to such

employment, such superintendent, principal, teacher, in

structor, professor, or other teacher shall have filed with

such board of trustees or governing authority an affidavit

as to the names and addresses of all incorporated and/or

unincorporated associations and organizations of which

such superintendent, principal, teacher, instructor, profes

sor, or other teacher is, or within the past five (5) years,

has been a member, or to which organization such super

intendent, principal, teacher, instructor, professor, or other

teacher is presently paying, or within the past five (5)

years has paid, regular dues or to which the same is mak

ing, or within the past five (5) years, has made regular

contributions.

§ 8282-42. Form of affidavit.

Such affidavit may be in substantially the following form:

State oe ....................

COUNTY on .................

I, .................. (name of affiant), being an applicant for

the position of ...... .......... at ................. (name of school

24

or institution), being first duly sworn, do hereby depose

and say that I am now or have been within the past 5

years a member of the following organizations and no

others:

Appendix A

(names and addresses of organizations)

and further, that I am now paying, or within the past five

(5) years have paid, regular dues or made regular contri

butions to the following organizations and no others:

(names and addresses of organizations)

(Signature of Affiant)

Affiant

Sworn to and subscribed before me, this the ...... (date)

day o f ................. (month), 19—.... (year).

(Signature of Official)

Title of Official

25

§ 6282-43. Contracts of employment void for failure to file

affidavit.

Any contract entered into by any board of trustees of

any school district, junior college, institution of higher

learning, or other educational institution supported wholly

or in part by public funds, or by any governing authority

thereof, with any superintendent, principal, teacher, in

structor, professor, or other instructional personnel, who

shall not have filed the affidavit required in section 1

[§ 6282-41] hereof prior to the employment or election of

such person and prior to the making of such contracts,

shall be null and void and no funds shall be paid under

said contract to such superintendent, principal, teacher,

instructor, professor, or other instructional personnel; any

funds so paid under said contract to such superintendent,

principal, teacher, instructor, professor, or other instruc

tional personnel, may be recovered from the person re

ceiving the same and/or from the board of trustees or

other governing authority by suit filed in the circuit court

of the county in which such contract was made, and any

judgment entered by such court in such cause of action

shall be a personal judgment against the defendants therein

and upon the official bonds made by such defendants, if

any such bonds be in existence.

§ 6282-44. Penalty for filing false affidavit.

Every person who shall wilfully file a false affidavit

under the provisions of this act shall be guilty of perjury,

shall be punished as provided by law, and in addition, shall

forfeit his license to teach in any of the schools, junior

colleges, institutions of higher learning, or other educa

tional institutions supported wholly or in part by public

funds in this state.

Appendix A

26

§ 8282-45. Constitutionality.

If any paragraph, sentence, clause, phrase, or word of

this act shall be held to be unconstitutional for any reason,

such holding of unconstitutionality shall not affect any

other portion of this act; nothing herein contained, how

ever, shall be construed so as to affect the validity of any

contract entered into prior to the effective date of this act.

Appendix A

27

APPENDIX B

Isr the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 21438

Noelle M. H enry,

-v -

Appellcmt,

Coahoma County B oard of E ducation, et al.,

Appellees.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r i c t c o u r t

FOR T H E NO RTH ERN DISTRICT OF M ISSISSIPPI

(December 3, 1965.)

B e f o r e :

H utcheson and B rown, Circuit Judges,

and Morgan, District Judge.

Per Curiam:

This is an appeal from a judgment of the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi,

denying plaintiff the relief she sought in her suit to re

quire by injunction that she be re-employed as a teacher

in the Public School System of Coahoma County, Missis

sippi.

Appellant, Mrs. Henry, is a negro school teacher who

has taught in the same school for eleven years. In Missis-

28

sippi teachers have no tenure but are hired on one year

contracts which are reviewed for renewal each year. The

usual or ordinary, indeed the required, procedure is that

the teacher’s principal or supervisor make his recommen

dation for renewal to the County School Superintendent,

and the superintendent in turn makes his recommendation

to the School Board. It is statutory in Mississippi1 that

the School Board cannot hire anyone not recommended

by the County Superintendent. It is also required by

statute that all teacher applicants list all organizations

to which they do belong or have belonged or to which

they have contributed money for the past five years. Mrs.

Henry was, and is, a member of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People and also the only

teacher to so state on her application. Although she was

recommended by her supervisors to Hunter, the County

Superintendent, Hunter did not recommend her, and her

contract was not renewed for the 1962-1963 school year.

Mrs. Henry testified that she made three separate at

tempts to obtain an explanation from Hunter or the School

Board as to the basis of the refusal to renew her contract,

but each time Hunter told her the Board had made the

refusal and had given him no reason therefor and that

further discussion of the matter would be useless. She

filed suit, stating as the basis for her complaint that the

Board had refused to renew her contract because she was

a member of the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People and because her husband was

and is President of that Association in Mississippi. Re

lief prayed for was that the Board be enjoined from re

fusing to renew her contract for 1962-1963 and that the

Appendix B

1 See Lott v. State, 121 So.2d. 402.

29

statute requiring teacher applicants to list their organ

izational activities be declared unconstitutional.

At the trial Hunter testified that the Board had not

renewed the contract because he had not recommended

Mrs. Henry. When questioned by the court, he stated

that his refusal to recommend her was based on the fact

that her husband had been convicted on a morals charge

and had suffered an adverse judgment in a libel suit, and

that he had reliable information that suit was about to

be filed against Mrs. Henry in respect of a fraudulent

conveyance made to her by her husband. Hunter ex

pressly testified that his decision was not due to Mrs.

Henry’s or her husband’s civil rights activities or any

N.A.A.C.P. affiliations.

At the conclusion of the hearing the Court ordered a

time for filing memorandum briefs. During this time

Mrs. Henry moved to amend her complaint under Rule

15(b) to conform to the reasons given by Hunter as a

basis for his refusal to recommend her. The district judge

refused to allow the amendment on the basis that it

would change the entire character of the case. Also he

pointed out that the evidence which formed the basis for

the motion was elicited by questions from the court and

that it came in over the objection of the plaintiff; that

with notice this point could be much more fully developed

since neither side had come prepared on this issue, and to

allow the amendment at that late date would be to do so

without such development. However, the judge stated

that in the event of appeal, in order that the appellate

court might have the benefit of the lower court’s views

in this aspect of the case, he had dealt with the case as

if the motion to amend had been granted.

Judgment was entered, refusing to enjoin the Board on

the basis that Mrs. Henry had failed to sustain her burden

Appendix B

30

of proof that the refusal to renew her contract was due

to her civil rights activities. On the contrary, the finding

was that the Board was without authority to renew the

contract due to Hunter’s failure to recommend Mrs. Henry,

and thus was not properly a party to the suit. Further

the court found that the reasons to which Hunter testified

constituted good cause and that he exercised sound dis

cretion in not recommending Mrs. Henry for re-employ

ment. The court refused to rule on the constitutionality

of the statutory requirement that teachers list their or

ganizational activities, stating that: “Inasmuch as plain

tiff in her present status as a non-teacher is not affected

by this requirement, this issue is now moot”.

The district judge filed a full opinion,2 stating the facts

and issues and the reasons and grounds for his findings,

decision and judgment.

We agree with his decision and judgment and adopt

his opinion as our own, and, because we do, it will be un

necessary for us to repeat or discuss further his f ind i n g s

and conclusions. It will be sufficient to say that we ap

prove and adopt his opinion and the findings and con

clusions stated in it and order the judgment AFFIRMED.

BROWN, Circuit Judge, Concurring.

In joining in the affirmance, I would emphasize two

things about the Court’s decision. First, though the

Superintendent may have broad discretion in recommend

ing or refusing to recommend a teacher for employment

by the Board, the Court recognizes that this discretion

does not prevent judicial inquiry into the constitutional

propriety of his motives in refusing to recommend Plain

tiff. See Hornsby v. Allen, 5 Cir., 1964, 326 F.2d 605, re

Appendix B

2 Henry v. Coahoma County Board of Education, et al. F.Supp.

31

hearing denied, 330 F.2d 55. Discretion gives much power,

hut this power may never be used to interfere with, or

discourage, the exercise of federally guaranteed civil rights

including the right to persuade or encourage others in

the exercise of their civil rights. United States v. Bruce,

5 Cir., 1965,-----F.2d — [No. 22028, Nov. 16, 1965]; see

United States v. Board of Educ. of Green County, Miss.,

5 Cir., 1964, 332 F.2d 40. Second, though a teacher’s

husband’s criminal record and involvement in litigation

undoubtedly in many cases may justify a refusal to recom

mend her for this sensitive employment, if in fact such a

record and such involvement spring wholly from attempts

by him to exercise these broadly defined civil rights, then

under such circumstances these considerations would not

justify a refusal to recommend either under the exercise

of—or the guise of exercising—such discretion.

The Court affirms because the Plaintiff failed to prove

either that the Superintendent’s refusal to recommend her

was based on the civil rights activity of her or her hus

band, or that her husband’s criminal record, which the

Superintendent did consider, arose primarily from con

stitutionally protected assertions of civil rights.

Appendix B

32

Judgment

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob the F ifth Circuit

October Term, 1965

No. 21438

D. C. Docket No. 43-62

Noelle M. H enry,

Appellant,

C o a h o m a C o u n t y B o a r d o f E d u c a t i o n , et al.,

Appellees.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r i c t c o u r t

FOR T H E NO RTH ERN DISTRICT OF M ISSISSIPPI

B e f o r e :

H utcheson and Brown, Circuit Judges,

and Morgan, District Judge.

This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of the

record from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Mississippi, and was argued by coun

sel;

On c o n s i d e r a t i o n w h e r e o f , It is now here ordered and

adjudged by this Court that the judgment of the said

District Court in this cause be, and the same is hereby,

affirmed;

33

Judgment

It is further ordered and adjudged that the appellant,

Noelle M. Henry, be condemned to pay the costs of this

cause in this Court for which execution may be issued out

of the said District Court,

December 3, 1965

Brown, Circuit Judge, Specially Concurs.

Issued as Mandate: Jan. 12, 1966

34

On Petition for Rehearing

I n t h e

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 21438

Noelle M. H enry,

Appellant,

Coahoma County Board of E ducation, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM T H E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E NO RTH ERN DISTRICT OF M ISSISSIPPI

(January 4, 1966)

B e f o r e :

H utcheson and Brown, Circuit Judges,

and Morgan, District Judge.

P er Curiam:

It is Ordered that the petition for rehearing in the

above entitled and numbered cause be, and it is hereby

Denied.

U. S. Court of Appeals

F iled

J an. 4, 1966

E dward W. W adsworth

Clerk

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. *'»