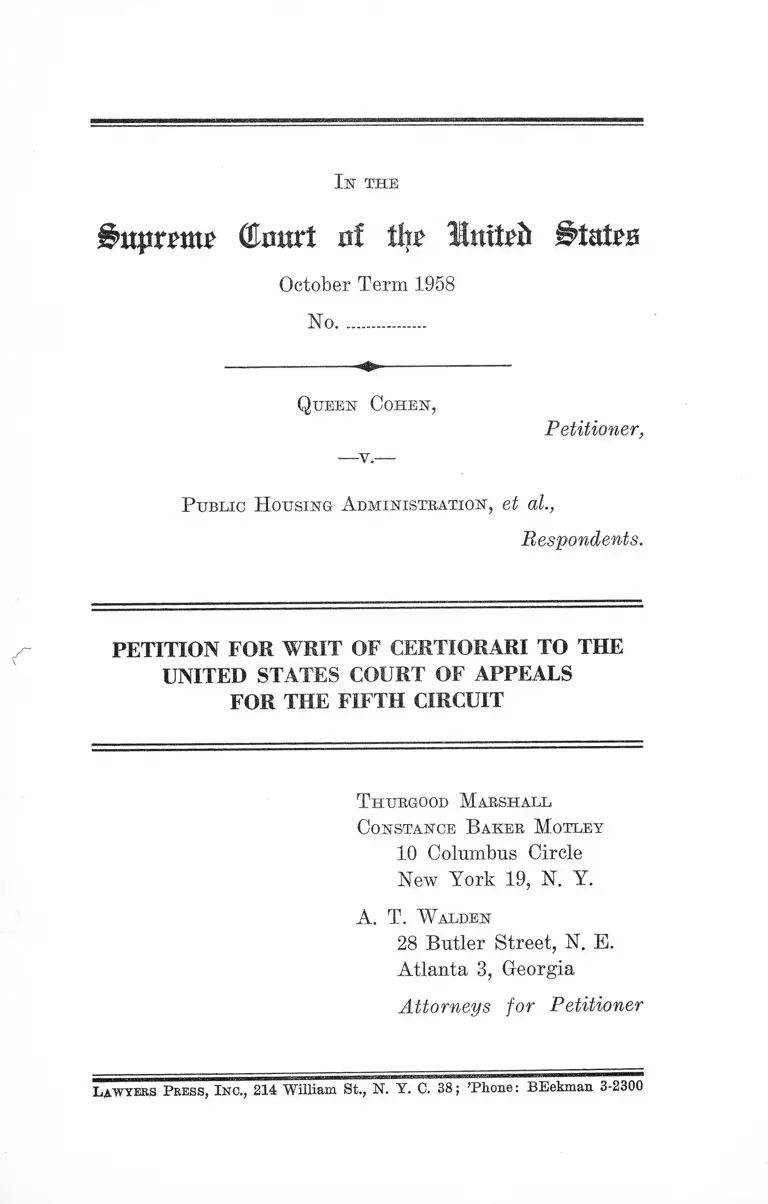

Cohen v. Public Housing Administration Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cohen v. Public Housing Administration Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1958. faa52ce1-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a7add739-d813-411e-bc46-57e8e7ae1573/cohen-v-public-housing-administration-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

(Eimrt nf tty llmtpfr i^iata

October Term 1958

No................

Q ueen C o h e n ,

•— v .

Petitioner,

P ublic H ousing A d m in istra tio n , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

T hurgood M arsh all

C onstance B ak er M otley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

A. T . W alden

28 Butler Street, N. E.

Atlanta 3, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioner

Lawyers Press, I nc., 214 William St., N. Y. C. 38; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300

SUBJECT INDEX

PAGE

Opinions B elow .................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .............................................................-......... 2

Questions Presented ........................................................ 2

Constitutional And Statutory Provisions Involved..... 2

Statement Of The Case....................................................... 3

Reasons Relied On For Allowance Of W rit ..................... 9

C o n c l u s io n ............................................................................................. 19

A p p e n d ix ............................................................................................... 20

T able of Cases

Barnes v. City of Gadsden, Alabama (U. S. D. C. N. D.

Ala, 1958), Civil Action No. 1091, 3 Race Relations

Law Reporter 712 (1958) ...........................................- 10

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ................................. 9,18

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ..................................... 18

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S.

294 .................................................................................. 17

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 TJ. S. 60 ................................. 9,18

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board (E. D. La. 1956),

138 F. Supp. 337, aff’d (5th Cir. 1957), 242 F. 2d 156,

cert. den. 354 U. S. 921....................................... -........ 13

Cohen v. Public Housing Administration (5th Cir.

1958), 257 F. 2d 7 3 ..................................................... - 1,5

County School Board of Arlington Co. Va. v. Thomp

son (4th Cir. 1958), 252 F. 2d 929 ............................ 13,17

11

Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis (6th Cir. 1955),

226 F. 2d 180.................................................................. 10

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County

(5th Cir. 1957), 246 F. 2d 913................................... 13,14

Heyward, et al. v. Housing and Home Finance Agency,

et al., unreported (U. S. D. C. D. C.), Civil Action

No. 3991-52, decided May 28, 1953 ............................... 3,11

Heyward, et al. v. Public Housing Administration

(D. C. Cir. 1954), 214 F. 2d 222 ................................... 3,11

Heyward, et al. v. Public Housing Administration, et

al. (S. D. Ga. 1955), 135 F. Supp. 217........................4,12

Heyward, et al. v. Public Housing Administration, et

al. (5th Cir. 1956), 238 F. Supp. 689 ......................4,12,13

Heyward, et al. v. Public Housing Administration, et

al. (S. D. Ga. 1957), 154 F. Supp. 589 ........................ 1,4

Housing Authority of City & County of San Francisco

v. Banks, 120 Cal. App. 2d 1, 260 P. 2d 668, cert. den.

347 U. S. 974 .................... ........................................... .. 10

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 2 4 ...........................................9,18

Johnson v. Levitt & Sons, Inc. (E. D. Pa. 1955), 133 F.

Supp. 114 ............................... ...... ................................. 10

Jones v. City of Hamtrainck (S. D. Mich. 1954), 121 F.

Supp. 123 ....................................................................... 10

Ming v. IJorgan, Superior Court, Sacramento County,

California, No. 97130, decided June 23, 1958, 3 Race

Relations Law Reporter 693 (1958) .......................... 10

New York State Commission Against Discrimination v.

Pelham Hall Apartments, 170 N. Y. S. 2d 750 (1958) 10

School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen

(4th Cir. 1956), 240 F. 2d 59, cert. den. 353 U. S. 910

13,14,17,18

PAGE

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ..................................... 9,18

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631...................... 14

Tate v. City of Enfaula, Alabama (U. S. I). C. M. D.

Ala. 1958), Civil Action No. 1442-N, nnreported,

decided August 6, 1958 ...............................................10-11

Vann v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority (N. D.

Ohio 1953), 113 F. Supp. 210.... .................................. 10

S t a t u t e s :

Title 28, United States Code, §1254(1) ............................ 2

Title 28, United States Code, §1331................................. 3, 4

Title 28, United States Code, §1343(3) ............................ 3

Title 42, United States Code, §1410(g) ........................2, 4, 6

Title 42, United States Code, §1415(8) ( a ) ................ —- 2, 6

Title 42, United States Code, §1415(8) ( b ) .....— ........... 2, 6

Title 42, United States Code, §1415(8) (c) ....................2, 4, 6

Title 42, United States Code, §1401, et seq...................... 5

Title 42, United States Code, §1402(1) ........................... 2, 6

Title 42, United States Code, §1402(14) .......................... 2

Title 42, United States Code, §1982 ................................. 2

Title 42, United States Code, §1983 ..................... - ........ - 2, 4

Oth e r A u thorities :

Johnstone, The Federal Urban Renewal Program, 25

University of Chicago Law Review 301 (1958) .......10,11

I ll

PAGE

I n t h e

Supreme (tart ni % United States

October Term 1958

No................

Q u een C o h e n ,

Petitioner,

P ublic H ousing A d m in istra tio n , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner prays that a "Writ of Certiorari issue to re

view the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit,

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit is reported. Cohen v. Public Housing Ad

ministration, et al., 257 F. 2d 73 (1958). The opinion of

the United States District Court for the Southern District

of Georgia, Savannah Division, is also reported. Heyward,

et al. v. Public Housing Administration, et al., 154 F. Supp.

589 (1957). Copies of these decisions are set forth in

Appendix A and the printed record.

2

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to the

provisions of Title 28, United States Code, §1254(1).

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit was rendered on June 30th, 1958. Peti

tion for rehearing was denied on August 11, 1958.

Questions Presented

1. Whether a plaintiff qualified for admission to feder

ally-aided public housing lacks standing to sue to enjoin

the policy of limiting certain projects to white and others

to Negro occupancy, which derives from local application

of the Public Housing Administration’s racial equity re

quirement, simply because the court, weighing disputed

testimony, found that she failed to prove formal applica

tion to and express exclusion from a particular project?

2. Whether there is any constitutional and/or statutory

duty on the Public Housing Administration to refrain from

approving and aiding racially segregated public housing

projects, and to require that federally-aided public housing

be made available on a non-discriminatory basis in accord

ance with the statutory preferences for admission?

Constitutional And Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the due process clause of the Fifth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States and

the due process and equal protection clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment thereto.

In addition, the following sections of Title 42, United

States Code are involved: 1402(1), (14); 1410(g); 1415(8)

(a), (b) and ( c ) ; 1982; 1983.

3

Also involved is the Public Housing Administration’s

regulation requiring racial equity. These statutory provi

sions and this regulation are set forth in Appendix B.

Statement Of The Case

This suit was originally brought in the United States

District Court for the District of Columbia by the filing of

a complaint against the Public Housing Administration in

September 1952 in an attempt to enjoin the expenditure of

federal funds for the construction of a project on a Negro

residential site which would be limited to white occupancy.

The district court dismissed the suit on its merits on the

ground that separate and equal facilities were being pro

vided for Negroes. Heyward, et al. v. Housing and Home

Finance Agency, et al., Civil Action No. 3991-52 unreported

(copy of opinion of May 8, 1953 set forth in Appendix C).

On appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia Circuit the dismissal was affirmed on

the ground that the Housing Authority of Savannah,

Georgia was a conditionally necessary party and plaintiffs

should therefore bring the suit where both parties could be

brought before the court. Heyward, et al. v. Public Housing

Administration, 214 F. 2d 222 (1954).

Suit was thereafter filed in May 1954 in the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Georgia, Savan

nah Division, against the Public Housing Administration

(PHA), its Atlanta Field Office Director, the Housing Au

thority of Savannah, Georgia (SHA), its members and

executive director. Jurisdiction was invoked pursuant to

Title 28, United States Code, §§1331 and 1343(3) (R. 2-3).

The district court dismissed the complaint on SHA’s motion

to dismiss and PHA’s motion for summary judgment on

the ground that separate but equal facilities was still the

4

law applicable to this case and on the ground that PH A is

not involved in the controversy. Heyward, et al. v. Public

Housing Administration, et al., 135 F. Supp. 217 (1955).

An appeal was taken from this judgment to the court

below where it was reversed in part and affirmed in part.

Heyward, et al. v. Public Housing Administration, et al.,

(5th Cir. 1956) 238 F. 2d 689. Affirmance related only

to dismissal of the complaint as to the Atlanta Field Office

Director of PHA. In reversing, the court held that the

complaint stated a cause of action within the provisions of

Title 42, United States Code, §1983 and sufficiently alleged

jurisdiction over PHA under Title 28, United States Code,

§1331.

After a full trial on the merits, the district court dis

missed petitioner’s case on the ground that the evidence

failed to establish that she had made application for admis

sion to any project and the undisputed testimony shows

that she was not entitled to a statutory preference for ad

mission. Title 42, United States Code, §1410(g) or 1415

(8) (c). Heyward, et al. v. Public Housing Administration,

et al., 154 F. Supp. 589 (1957).

Upon the second appeal to the court below it affirmed

dismissal on the ground that since petitioner did not make

application, she has no standing to sue. It ruled that 1) the

district court’s pertinent finding that petitioner did not

make application does not appear to be clearly erroneous

as required for reversal by Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure, 28 U. S. C. A.; 2) in the absence of any

attempt to apply, there is no reasonably certain proof that

petitioner actually desired in some earlier year to become

a tenant in Fred Wessels Homes; 3) an application by peti

tioner would not have been a vain act or the yielding to an

unconstitutional demand.

5

However, the court below then held in the alternative that

since this case involves voluntary segregation, such segre

gation is not subject to constitutional attack. It ruled that

both the pleadings and the proof denied segregation. It

noted testimony of the executive director of SHA to the

effect that “ in his opinion actual segregation is essential to

the success of a program of public housing in Savannah”

and ruled that,

“ If the people involved think that such is the case and

if Negroes and whites desire to maintain voluntary

segregation for their common, good, there is certainly

no law to prevent such cooperation. Neither the Fifth

nor the Fourteenth Amendments operates positively to

command integration of the races, but only negatively

to forbid governmentally enforced segregation.”

Cohen v. Public Housing Administration, et al., 257 F. 2d

73, 78 (1958).

This decision was based upon the following facts appear

ing in the record :

1. The housing program involved in this ease is low rent

public housing provided for by the United States Housing

Act of 1937, as amended.1 This is a program whereby the

federal government, through PHA, and local public housing

agencies established by law in the several states, enter into

contracts for the construction, operation and maintenance

of decent, safe and sanitary dwellings. These dwellings are

available to only those families who, because of their low

incomes, are unable to secure decent, safe and sanitary

private housing at the lowest rates at which such private

housing is being provided in the locality (R. 85). PHA and

SHA have entered into contracts for construction, opera

tion and maintenance of nine such public housing projects

in the City of Savannah (R. 81).

1 Title 42, United States Code, §1401, et seq.

6

2. The record in this case discloses that petitioner meets

the income requirements for admission which have been

established by SHA and approved by PHA.2 (R. 133, 206.

See Plaintiff’s Exhibit 10, Answer to Interrogatory No. 6.)

3. Petitioner was displaced from her home when a com

mercial enterprise which had been located on the site of

Fred Wessels Homes moved its business across the street

to the site of petitioner’s former residence (R. 204-205).

When petitioner received a thirty-day notice from her land

lord to vacate, she went to the office of SHA which is lo

cated in the Fred Wessels Homes, for the purpose of mak

ing application for a family unit (R. 131).3 She was advised

that the Fred Wessels project was not for Negro families

(R. 133). She was not given a formal application blank.

She was told to apply at Fellwood Homes, a Negro project

(R. 133). At that time the buildings were completed but

unoccupied (R. 135). Appellant desires to live in Fred

Wessels Homes (R. 139). She is the mother of four chil

dren, one of whom is in the armed services of the United

States (R. 133).4 Her husband is employed and earns fifty

dollars per week (R. 206).

4. The Director-Secretary of SHA insisted that peti

tioner and other Negroes never applied for admission to

Fred Wessels Homes. Upon the trial he was asked, “ Q. If

a negro applied for admission to the Fred Wessels Homes

2 Title 42, United States Code, §§1402(1), 1415(8) (a).

3 Families having the greatest urgency of need are given prefer

ence for admission by virtue of the provisions of Title 42, United

States Code, §1415(8) (c). See also Title 42, United States Code,

§1415(8)(b).

4 Families of servicemen have preference. Title 42, United States

Code, §1410(g). See Annual Contributions Contract, Part II, Sec

tions 206, 208, 209, Plaintiff’s Exhibit 1. PHA has the responsibility

for seeing that the preferences are applied (R. 175).

7

would you put him in there? Is that what you are saying?

A. No. He would be given consideration, but I don’t know

what I would do. . . . Q. Are you saying you would admit

negroes? A. I didn’t say that.” (E. 127)

5. The evidence shows that other Negroes also went into

the office located in Fred Wessels Homes to apply for hous

ing. Those who did so were assigned to Fellwood Homes.

None was considered for admission or assigned to Fred

Wessels Homes (E. 95-97).

6. Prior to the opening of Fred Wessels Homes for occu

pancy, SHA publicly announced that this project would be

for white occupancy (R. 112).

7. There is no central tenant application office in Savan

nah. Applicants generally apply at the particular projects

they desire to enter (R. 82). However, the ultimate deter

mination as to the project in which the applicant family

will reside remains with SHA (E. 96-97).

8. Limitation of certain projects to Negro occupancy and

the limitation of others to white occupancy is approved by

PHA through approval of SHA’s Development Programs

which must reflect application of PHA’s racial equity re

quirement (E. 54-55).5 PHA, by its administrative rules

and regulations, requires that a local program “ reflect

equitable provision for eligible families of all races deter

mined on the approximate volume of their respective needs

for such housing” (Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2, PHA Racial Pol

icy). The need of the two races is determined primarily by

the approximate volume of substandard housing occupied

by each race (E. 91-92). Application of this formula re

5 The two most recent, Development Programs were sent up to

this Court in their original form. Plaintiff’s Exhibits 7 and 8.

These programs designate the racial occupancy of each project.

8

suited in the present determination that equitable provision

for Negro families in Savannah requires that they be pro

vided with approximately 75% of the total number of fam

ily units and that equitable provision for white families

requires that they be provided with approximately 25% of

the total number of family units (E. 106-107). However,

Negroes presently occupy only 42.7% of the existing units

and whites, because of the addition of the two former PHA

owned defense housing projects to the public housing sup

ply, presently occupy 57.3% of the existing units (R. 104).

The Development Programs, when approved by PHA, be

come a part of the contracts between PHA and SHA (R.

178).

9. Once a determination is made as to the approximate

per cent of the total number of units to be occupied by

Negro and white families, PHA would object to a deviation

from these percentages by SHA (R. 181). The Director-

Secretary of SHA viewed the admission of Negroes to Fred

Wessels Homes as resulting in a violation of PHA’s racial

equity requirement (R. 121-122).

10. The most recently completed project in Savannah is

Fred Wessels Homes which opened for occupancy in 1954

(R. 188). This project has been built on a site located ap

proximately seven blocks from the main business area of

Savannah (R. 114). It contains 250 family units at a cost

of approximately $2,800,000 (R. 113). Prior to construction

of this project, the site was occupied by 250 Negro families

and 70 white families (R. 102-103). This project has been

limited to white occupancy (R. 103).

11. Petitioner did not join this suit as a named plaintiff

until action was instituted against both PHA and SHA in

Savannah (R. 137-138). When suit was filed in the District

of Columbia the action was brought by 13 named plaintiffs

9

on behalf of themselves and others similarly situated. Fred

Wessels Homes had not yet been constructed and the site

occupants had not yet been displaced. When suit was re-

instituted about two years later in Savannah, after the

decision of the Court of Appeals for the District of Colum

bia, only 4 of the original plaintiffs were named again as

plaintiffs. These 4 were joined by 14 new plaintiff's suing

on behalf of themselves and others similarly situated (R.

1, 7). By this time, Fred Wessels Homes had opened for

white occupancy (R. 188); 250 Negro families, including

15 plaintiffs, had already been displaced and relocated (R.

102-103, 116-118, 126). However, the majority of the dis

placed Negro families had found housing on their own, had

not accepted relocation assistance from SHA and had not

accepted segregated Negro public housing (R. 88-89).

12. This case did not come to trial until 3 years after it

had been instituted in Savannah. On the trial petitioner

was asked over and over again by SHA’s counsel why she

wanted to live in Fred Wessels Homes and whether she

really wanted to live there. Her answers clearly indicate a

genuine desire to live there. She has lived in the area all

her life (R. 139-140).

Reasons Relied On For Allowance Of Writ

I. The Public Importance Of This Case.

This case reveals that despite decisions of this Court

voiding legislative and judicial enforcement of residential

racial segregation, Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60; Shel

ley v. Kraemer, 334 H. S. 1; Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24;

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 H. S. 249, the executive arm of

the federal government, through an agency concerned with

the provision of housing, has continued to approve, par

ticipate in, and to finance the construction, operation and

10

maintenance of racially segregated housing developments.

The Public Housing Administration has not only approved,

participated in, and financed racially segregated public

housing developments in the southern states but has done

so in northern states as well. See e.g. Detroit Housing

Commission v. Lewis (6th Cir. 1955), 226 F. 2d 180; Hous

ing Authority of City & County of San Francisco v. Banks,

120 Cal. App. 2d 1, 260 P. 2d 668, cert. den. 347 U. S.

974; Jones v. City of Hamtramck (S. D. Mich. 1954), 121

F. Supp. 123; Vann v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Au

thority (N. D. Ohio 1953), 113 F. Supp. 210.

PHA is only one of several federal housing agencies

concerned with the provision of housing. The Federal

Housing Administration and the Veterans’ Administration

are also concerned with the provision of housing through

the federal government’s mortgage insurance programs.

These agencies are likewise involved in the development of

racially segregated housing communities. See e.g., John

son v. Levitt & Sons, Inc. (E. II. Pa. 1955), 131 F. Supp.

114; New York State Commission Against Discrimination

v. Pelham Hall Apartments, Inc., 170 N. Y. S. 2d 750 (1958);

Ming v. Horgan, Superior Court, Sacramento County,

California, June 23, 1958, No. 97130, 3 Race Relations Law

Reporter 693 (1958).

In addition to PHA, FHA and VA, it now appears that

the Urban Renewal Administration, the federal govern

ment’s newest agency concerned with the provision of

housing and the renewal of whole cities is now involved in

the redevelopment of racially segregated housing communi

ties. See Johnstone, The Federal Urban Renewal Program,

25 University of Chicago Law Rev. 301, at 337-341 (1958).

See, e.g., Barnes v. City of Gadsden, Alabama (U. S. D. C.

N. D. Ala. 1958), Civ. No, 1091, 3 Race Relations Law Re

porter 712 (1958); Tate v. City of Eufaula, Alabama (U. S.

11

D. C. M. D. Ala. 1958), Civil Action No. 1442-N, unreported,

decided August 6, 1958.

The phenomenal growth and influence of federal agencies

concerned with the provision of housing since the early

1930’s makes manifest the role of the federal administrator

in the housing market.6 Public housing, mortgaged insured

housing, and urban renewal housing, where segregated

throughout the United States, is supported by federal

funds, powers and credits. Federal administrators have,

therefore, become primary agents in the extension of segre

gated living.

Whether there is any constitutional and/or statutory

duty on the Public Housing Administration to refrain

from approving, participating in, and financing racially

segregated public housing projects and to require that

federally-aided public housing be made available on a non-

discriminatory basis in accordance with the statutory

preferences for admission is an important question of fed

eral law which has not been, but should be, settled by this

Court.

When the instant case was before the United States Dis

trict Court for the District of Columbia, Heyward, et al.

v. Housing and Home Finance Agency, et al. (unreported,

Civil No. 3991-52, opinion of May 8, 1953 in Appendix C),

that court held that the federal government could provide

public facilities on a separate but equal basis.

When an appeal was taken to the Court of Appeals for

the District of Columbia, Heyward et al. v. Public Housing

Administration, 214 F. 2d 222 (1954), that court did not

rule upon the merits as the district court had but, never

theless, did point out in its opinion that the PHA had ap

6 Johnstone, The Federal Urban Renewal Program, 25 Univ. of

Chicago Law Review. 301 (1958).

12

proved racial segregation in public housing in Savannah,

Georgia.

When suit was then instituted in Savannah against both

PHA and SHA, the district court there held that the sepa

rate but equal doctrine applied to this case and dismissed

the complaint, Heyward, et al. v. Public Housing Adminis

tration, et al., 135 F. Supp. 217 (1955).

Upon the first appeal to the court below, Heyward, et al.

v. Public Housing Administration, et al., 238 F. 2d 689

(1956), it ruled that “ the complaint sets forth allegations

which, if proven, would show a failure on the part of PHA

to comply with the . . . statutory tenant selection policy,

and this would constitute a violation of plaintiffs’ rights

to due process under the Fifth Amendment” (at 697). That

court also ruled that “at the time this action was filed the

regulations of PHA required that any local program for

the development of low-rent housing reflect equitable pro

vision for eligible families of all races, but did not require

that housing be made available on a non-segregated or non-

discriminatory basis” (emphasis ours) (at 697). In addi

tion to these rulings, the court said: ‘While it is true that

PHA has not been charged by Congress with the duty of

preventing discrimination in the leasing of housing project

units, what these plaintiffs are saying in effect is that the

federal agency is charged with that duty under the Fifth

Amendment, and that that duty should be forced upon PHA

by the courts through the medium of injunctive process”

(at 696).

II. The Court Below Has Decided This Case In Conflict With

Applicable Decisions Of This Court And Applicable Princi

ples Established By Decisions Of This Court.

A. In the court below petitioner assigned as error the

district court’s finding that she had not applied. She also

contended that prior application is not a prerequisite to

13

the maintenance of this suit since her case is, that, although

eligible for admission, she is not “permitted to make appli

cation for any project limited to white occupancy.” Hey

ward, et al. v. Public Housing Administration, et al. (5th

Cir. 1956), 238 F. 2d 689, 698. Petitioner contends that

a policy of segregation says, in effect, that she may not

apply for a white project—that she may only apply for,

would only be considered for admission to, and would

only be assigned to, a Negro project, as occurred in the

case of other Negroes who applied at Fred Wessels Homes

(R. 95-96). Petitioner contends that since segregation is

the announced policy (R. 112) application for admission

to a particular white project, prior to reversal of this

policy or a court injunction enjoining enforcement of the

policy, would be a vain act, and equity does not require

the doing of a vain act as a condition of relief. In so

contending she relied upon the Fourth Circuit’s ruling in

School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen (4th

Cir. 1956), 240 F. 2d 59, cert. den. 353 U. S. 910, which

was followed by the court below, itself, in Gibson v. Board

of Public Instruction of Dade County (5th Cir. 1957),

246 F. 2d 913. See, also, Bush v. Orleans Parish School

Board (E. D. La. 1956), 138 F. Supp. 337, aff’d (5th Cir.

1957), 242 F. 2d 156, 162, cert. den. 354 U. S. 921 and

County School Board of Arlington County, Va. v. Thomp

son (4th Cir. 1958), 252 F. 2d 929.

In the Charlottesville case the Fourth Circuit ruled:

Defendants argue, in this connection (Pupil Place

ment Law), that plaintiffs have not shown themselves

entitled to injunctive relief because they have not in

dividually applied for admission to any particular

school and been denied. The answer is that in view

of the announced policy of the respective school boards

any such application to a school other than a segre

14

gated school maintained for Colored people would

have been futile; and equity does not require the doing

of a vain thing as a condition of relief (at 63-64).

The court below sought to distinguish the instant case

from the Charlottesville case and the Gibson case on two

grounds: 1) in each of those cases the plaintiffs had placed

themselves on record as desiring practically the same

relief as that sought from the court and 2) in each of

the cases relied on by petitioner it was admitted that dis

criminatory segregation of the races was being enforced

by the defendant Board, while, . . . in the present case,

in both the pleadings and the proof, governmentally en

forced segregation is denied.

If bringing the instant case in 1954 and pressing it

over a period of more than four years does not place

petitioner on record as desiring to be considered for ad

mission and as desiring to be admitted to public housing

without discrimination against her solely because of her

race and color, then petitioner submits that she can con

ceive of no more pointed way of putting herself on record

as being opposed to racial segregation in public housing.

This Court long ago overruled the contention that a Negro

who seeks equal protection of the law must first make a

prior demand upon the state for such equal protection

and give the state an opportunity to act upon such demand

before bringing suit. Sipuel- v. Board of Regents, 332

U. S. 631.

Not only was the court below in error in stating cate

gorically that the pleadings denied segregation but it was

likewise in error in stating that the proof failed to estab

lish governmentally enforced segregation. In their answer

the defendant SHA denied on the one hand that segre

gation was being enforced and yet, on the other hand,

15

removed all doubt on this question by the following para

graphs set forth therein:

“ (a) The white citizens of the United States and the

State of Georgia are protected under the Constitution

of the United States in their rights to life, liberty,

and the pursuit of happiness. To compel the white

race to live with, affiliate with, and integrate with the

Negro race in their private lives contrary to their

wishes, desires, beliefs, customs and traditions, is a

denial of their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States and an in

vasion of their right to privacy. The right of white

tenants of Fred Wessels Homes and other projects

of the Housing Authority not to be compelled to live

with or among the Negro race, and not to affiliate and

integrate with them is a valuable and inalienable right,

and the violation of these rights will cause them great

mental, psychological and physical distress, injury and

hurt. The destruction and abrogation of these rights

is a violation of both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution and laws of the United States

(E. 28).

(b) The policy of separating the white from the

colored race in the public housing projects, adopted

by the Housing Authority of Savannah, is not based

solely because of the fact that the colored race are

Negroes, but is largely done in order to preserve the

peace and good order of the community. The State

of Georgia and the City of Savannah, Georgia, each

has a paramount duty under the police power to so

regulate its citizens as to prevent disorder and violence,

and to preserve the peace, good order and dignity of

the community. Furthermore, the separation of the

races—that is, the white people from the Negroes by

16

the Housing Authority of Savannah is based largely

on the local situation with reference to the residences

of the white people and the Negroes in Savannah.

The Negroes are assigned to houses located in districts

in which they live and which are predominantly oc

cupied by Negroes, and the white people are assigned

to units of projects located in the districts where white

people predominantly reside.7 The policy of the Hous

ing Authority of Savannah is now and has been to

treat the white race and the colored race separately

but equally,—that is to say to afford each equal but

separate facilities (R. 28-29).

(c) Experience has shown that the indiscriminate

mixing of the white and colored races,—that is to say,

white people and Negroes in residential districts leads

to frequent and violent disturbances and riots, and

such policy leads to a great disturbance of the peace,

the good order and tranquility of the community, and

often results in violence and riots; and for this reason

the separation of the races—that is to say—the white

people from the Negroes in residential units erected or

to be erected by the Housing Authority of Savannah,

is required and is necessary (R. 29).

(d) The white tenants of Fred Wessels Homes and

other projects of the Housing Authority of Savannah

have a valuable property right and interest in the

housing units they occupy in the several projects and

in the written leases therefor with the Housing Au

thority of Savannah, and these valuable property rights

are protected by the Due Process of Law Clause of the

Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

7 It should be noted that the record clearly discloses that the site

on which the white Fred Wessels Homes project was erected was

occupied by 250 Negro families and 70 white families (R. 102-103).

17

States which provides that no property of a citizen

shall be taken or destroyed except under due process

of law. The occupancy by Negroes of units in these

projects assigned to and occupied by white tenants

will immediately destroy and take away the valuable

property rights of the white tenants in their respective

units, and this without their ever having their day in

Court” (R. 30).

As for the proof in this case, the record is clear that a

policy of racial segregation is being enforced not only by

the state agency but by the federal agency also (R. 121-122,

181). As a matter of fact, the court below, in its own

opinion, points out that “Mr. Stillwell’s testimony has been

noted (footnote 7, supra) to the effect that in his opinion

actual segregation is essential to the success of a program

of public housing in Savannah.” 8 But even more important

is the fact that the federal agency representative who testi

fied finally conceded that PHA would object if the SHA

departed from PHA’s racial equity requirement (R. 181)

application of which results in the limitation of certain

units to white and other units to Negro occupancy (R. 106-

107).

As pointed out by the Fourth Circuit in the Thompson

case, supra, which was a companion case with the Char

lottesville case at 240 F. 2d 59, the theory of the segrega

tion cases is often misunderstood. A plaintiff sues to en

join the segregation policy, not for admission to a particu

lar public facility. Assignment to a particular public facility

is left to the public agency involved. If injunction enjoin

ing the policy is disobeyed, only then may admission to a

specific facility be ordered. Brown v. Board of Education

of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294.

8 Mr. Stillwell is the Director-Secretary of the Savannah Housing

Authority.

18

B. After making invalid distinctions between the Char

lottesville and other cases cited above, the court below held

alternatively that since this case involves voluntary segrega

tion, the proof failing to establish governmentallv enforced

segregation, such segregation is not constitutionally vulner

able. It noted the testimony of the Director-Secretary of

SHA that “ actual segregation is essential to the success

of a program of public housing in Savannah.” Noting this,

it then proceeded to rule that, “ If the people involved think

that such is the case and if Negroes and whites desire to

maintain voluntary segregation for their common good,

there is certainly no law to prevent such cooperation.

Neither the Fifth nor the Fourteenth Amendments operates

positively to command integration of the races, but only

negatively to forbid governmentally enforced segregation”

(at 78).

But governmentally enforced racial segregation was con

clusively alleged and proved here, not “voluntary” segrega

tion. Because of this, the court below was bound to enjoin

the segregation. Such an injunction is required by applica

tion to this case of principles firmly established by this

Court in Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497; Buchanan v.

Warley, supra; Shelley v. Kraemer, supra; Hurd v. Hodge,

supra and Barrows v. Jackson, supra.

19

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, petitioner prays that a

writ of certiorari issue to review the judgment of the

court helow.

Respectfully submitted,

T httrgood M arsh all

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

C onstance B ak er M otley

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

A. T. W alden

28 Butler Street, N. E.

Atlanta 3, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioner

20

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

A ppen d ix A—

Opinion of Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit........... 21

Judgment of Court of Appeals............................... 31

Order Denying Rehearing ....................................... 32

A ppen d ix B—

Regulations, Statutes and Constitutional Provi

sions Involved .................... .................-....... -......... 33

HHFA PITA Low-Rent Housing Manual

(February 21, 1951) Section 102.1 Racial

Policy .............................................................. 33

Title 42, United States Code, §1402(1) and

(14) ...........................-....... -............................. 33

Title 42, United States Code, §1410(g) ......... 34

Title 42, United States Code, §1415(8) (a), (b)

and (c) ............................................................ 36

Title 42, United States Code, §1982 .................. 37

Title 42, United States Code, §1983 .................. 37

Fifth Amendment to Constitution of United

States................................................................ 38

Fourteenth Amendment to Constitution of

United States ................................................. 38

A ppen d ix C—

Opinion of United States District Court, District

of Columbia, filed May 8, 1953 ............................. 39

21

APPENDIX A

Opinion of Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit

I n th e

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob t h e F if t h C ibouit

No. 16866

Q ueen C o h e n ,

versus

Appellant,

P u blic H ousing A d m in istbation , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FBOM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOB THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA.

(June 30, 1958.)

B e f o r e :

R ives, B row n and W isdom ,

Circuit Judges.

R ives, Circuit Judge:

The complaint was originally brought by eighteen Negro

residents of Savannah, Georgia for an injunction, declara

tory judgment and money damages on account of racial

22

segregation in public bousing in that City, allegedly en

forced by the Public Housing Administration (hereinafter

called P.H.A.) and the Housing Authority of Savannah

(hereinafter called S.H.A.). Earlier orders of the district

court dismissing the action1 were affirmed in part and re

versed in part and remanded.2

After remand, but prior to the commencement of trial,

seventeen parties plaintiff voluntarily withdrew,3 leav

ing the appellant, Queen Cohen, as the sole plaintiff. At

the conclusion of the trial, the district court found as

a fact, inter alia, that “ Queen Cohen never made an

application for admission in the Fred Wessels Homes or

any other public housing project in Savannah.”

The appellant’s first specification of error is that:

“ The trial court erred in dismissing appellant’s suit,

after a full trial on the merits, on the ground that

appellant failed to prove that she had ever made ap

plication for admission to Fred Wessels Homes.”

The complaint alleged that: “ Each of the plaintiffs has

been denied admission to Fred Wessels Homes solely be

cause of race and color.” In their answer, the defendants

denied “ that these defendants have determined upon and

presently enforce an administrative policy of racial segre

gation in public housing in the City of Savannah, Georgia,”

and denied the allegation that “ Each of the plaintiffs has

been denied admission to Fred Wessels Homes solely be

1 Heyward v. Public Housing Administration, S. D. Ga. 1955,

135 P. Supp. 217.

2 Heyward v. Public Housing Administration, 5th Gir. 1956,

238 P. 2d 689.

3 Mr. Stillwell, Secretary and Executive Director of S.H.A.,

testified upon the trial that none of those seventeen had ever

applied for admission to Fred Wessels Homes; that fifteen of them

had applied for and been admitted to another project, Pell wood

Homes; and that two had never applied for any kind of housing.

23

cause of race or color.” The evidence showed that P.H.A.

was operating under its regulation quoted in full in our

former opinion,4 which requires that:

“ Programs for the development of low-rent housing,

in order to be eligible for PHA assistance, must re

flect equitable provisions for eligible families of all

races determined on the approximate volume of their

respective needs for such housing.” (PHA Housing

Manual, Section 102.1)

Its policies and practices were more fully described in the

testimony of Mr. Silverman, its Assistant Commissioner for

Management, quoted in the margin.5

4 Heyward v. Public Housing Administration, 5th Cir. 1956,

238 F. 2d 689, at p. 697.

5 “ Q. Now, what are the policies and practices of the Public

Housing Administration with respect to racial occupancy of low-

rent housing projects?

“A. It is the policy of the Public Housing Administration to

assure that equitable treatment is afforded to all eligible families

in a locality, and that all eligible families who are admitted to

housing projects by housing authorities are treated equally with

respect to income limits or rents to be charged and other conditions

of occupanys (sic).

“ Q. What is the policy and position of the Public Housing

Administration with respect to low-rent housing projects in

Savannah or elsewhere as to whether or not they are operated

by the Local Authority on a segregated or non-segregated basis?

“A. We have not required Housing Authorities to either segre

gate or non-segregate in housing projects. We have required that

the housing program in every locality be available to all segments

of the eligible low income families in that locality. We have not

prescribed the precise fashion in which the Housing Authority shall

extend that equality of treatment to the residents of the locality.

“ Q. Is that policy based on your interpretation of the require

ments and policies of the Housing Act itself ?

“A. Yes. It is based upon our construction of the United States

Housing Act and particularly the 1949 Housing Act Amendment.

The very act which created the preferences that have been dis

cussed here, the preferences extended to displaced families, when

it was being considered in the Congress, in the Senate, a motion

was made to attach a non-segregated requirement to the statute.

24

The Housing Authority of Savannah operated, or had

under construction, 2170 dwelling units of which 1120 were

designated for negro occupancy and 1050 for white. The

project known as Fred Wessels Homes was intended for

white occupancy, but Mr. Stillwell, the Secretary and Execu

tive Director of S.H.A., denied in his testimony that negroes

had ever been refused admission to that project.6 At the

That was defeated. It is our view that that action was Congres

sional recognition of the fact that local practices vary in the

United States, and that some Loeal Authorities did maintain

separate projects by race and other integrated, but the failure to

enact a specific congressional prohibition against it was recognition

that a variety of practices might prevail.

“ Q. With respect to the low-rent housing program throughout

the country, that is, those projects to which PHA gives financial

assistance to what extent has there been integrated occupancy as

to those projects?

“A. As of December 31st, last, which is the last statistical tabu

lation we have, on 445 projects, approximately, containing some

163,000 dwelling units, representing about 43 percent of the entire

program, were operated on an integrated basis.

“ Q. Would there be any objection on the part of the Public

Housing Administration if the Savannah Housing Authority, or

any other Local Authority, were to determine to operate a low-rent

housing project on integrated basis?

“A. None whatsoever.”

On cross-examination, Mr. Silverman testified:

“ Q. Now, I believe you stated that your Agency interpreted the

defeat of the anti-discrimination with respect to the Public Housing

bill as an authorization from Congress that you and your Agency

might approve segregation or integration in any particular Local

Authority, or any particular locality that a Housing Authority

might want to practice in public housing. Is that right ?

“A. Mrs. Motley, I don’t mean to quibble with you, but we

didn’t recognize it as that kind of an authorization. We recognized

it as Congressional recognition of the fact that practices varied

among the various localities in the country with respect to the

low-rent housing.”

6 “ Q. Well, were you taking applications from negroes for the

Fred Wessels Homes at anytime?

“A. For occupancy in there?

“ Q- Yes.

“ A. No. I have never been asked to do so. We have never had

an application from a negro for occupancy in any white project

25

same time, Mr. Stillwell candidly admitted that Ms hope for

success of a program of public housing for people unable

to pay the cost of decent and adequate private housing lay

in the maintenance of actual segregation.* I * * * * * 7

and by the same token we have never had an application from a

white man to go into a negro project. We have never had that to

come up.

“ Q. I f a negro applied for admission to the Fred Wessels Homes

would you put him in there ? Is that what you are saying ?

“A. No. He would be given consideration, but I don’t know what

I would do.

“ Q. You wouldn’t put him in there, would you?

“A. I don’t know what I would do. I have never had the ques

tion to come up.

“ Q. You know that this case is concerning your refusal to admit

negroes to the Fred Wessels Homes?

“A. Yes, but we have never refused to take them in there.”

7 “A. Well, as you know, our white projects are predominately

(sic) occupied by what is generally known as ‘Georgia Crackers’,

and you know that he would never consent to occupy a home adja

cent to or mixed up with the colored families. Consequently, it

would mean that the white projects would eventually be over

whelmingly negro, if not a 100 percent negro, and the average

income of the negro is less than the average income of the white

population of that same caliber, and consequently the average rent

per unit would be much less and it is a question in my mind

whether the rents would maintain the property and pay off its

debts.

“ Q. In other words, do I understand you to say that if colored

people were allowed to come into the white units the white people

would move out?

“A. That’s right.

“ Q. And there would not be sufficient eligible colored people to

occupy the units sufficient to pay the amount due on the debt of

that particular property. Is that right ?

“A. Yes, and when I say that I mean sufficient eligible of the

higher groups of rents. We have to have a certain percentage of

tenants who pay a minimum rent of $15.00 and graduate on up

so as to average down to enough to meet the expenses plus the

subsistive to retire the principal and interest on the notes and

bonds as they mature, and with this lessened income I question

whether there would be enough to meet all the obligations.

“ Q. And there could be a default, in your payments?

“A. Yes, that’s right, the bonds, and another thing it would

break down the racial equity.

The appellant did not claim that she had filed any written

application. Her testimony was that she went to make her

application “ around 1952, during the time I had to move,”

that the building of the Fred Wessels Homes had then been

completed, but “ It was empty and I didn’t know who was

going to take it, white or colored, and so I went to apply

for one.” She testified that she went to the office of the Fred

Wessels Project.8 Mr. Stillwell, the Secretary and Execu

tive Director of S.H.A., and Millard Williams, an employee

of S.H.A. from 1951 to 1955, were brought into the court

room for purposes of identification. The appellant was un

able to identify either of them as the one with whom she

had talked.9

Appellant testified that her cousin, Susie Parker, had ac

companied her when she went to make her application.

When Susie Parker came to testify, she positively identified

Millard Williams as the one with whom the conversation

took place.

In rebuttal, both Stillwell and Williams denied having had

any such conversation, or ever having seen the appellant

“ Q. Explain what yon mean by breaking down the racial equity?

“A. Well, that’s the point that Miss Motley has been trying to

bring out, that if it was turned into all colored then the white

eligible tenants would be deprived of their occupancy of the white

projects and we would default in our contract with the PHA

because we did not maintain a racial equity.”

8 “When I went into the office I met a clerk boy, and so I told

him that I wanted to apply for a house there. He took me upstairs.

When I got upstairs he showed me a room and in that room were

two white ladies, and so I asked them could I put in for a house

there. She took me to another office where there was a white man

sitting there. The white woman told me to explain it to this man,

and so I explained to him, I said, T came to put in for a house.’

He said, ‘Negroes are not allowed here. Go to Fellwood.’ That was

his remarks to me and so I turned around and walked out.”

8 “ Q. It was this man here ? Is that him ?

“A. I wouldn’t say, but he was a slender built man. I only saw

him once and then for about three minutes.”

27

or her cousin prior to the trial. Mr. Stillwell testified fur

ther that the Fred Wessels Homes had not even been built

in 1952, that there were then no buildings on the site.

Stillwell and Williams denied that there had been any

application or attempt to apply for admission to Fred Wes

sels Homes specifically on the part of any one of the eighteen

original plaintiffs, and generally on the part of any other

negro. None of the seventeen other original plaintiffs testi

fied in rebuttal, nor was any reason given for their failure

to testify.

The district court had the advantage of seeing and hear

ing the witnesses, while this Court may only read their

testimony. Upon the present record, it is an understatement

to say that the pertinent fact-finding by the district court

does not appear to be clearly erroneous Rule 52(a), Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure.

That, however, is not the end of this case, for appellant

next contends that she was not required to prove that she

applied for or was denied such admission because equity

does not require the doing of a vain act. Appellant argues

that similar acts have been held to be vain in cases involving

governmentally enforced racial segregation, citing School

Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen, 4th Cir. 1956,

240 F. 2d. 59, and Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of

Dade County, 5th Cir. 1957, 246 F. 2d. 913.

School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen,

supra, involved actions in behalf of Negro school children

to enjoin School Boards from enforcing racial segregation.

Applications had been made to the Boards to take action

toward abolishing the requirement of segregation in the

schools, and no action had been taken. The Boards con

tended that, before the plaintiffs would be entitled to in

junctive relief, they must have individually applied for and

been denied admission to a particular school. The Fourth

Circuit, speaking through the late Chief Judge Parker,

said:

“ * * * The answer is that in view of the announced

policy of the respective school boards any such applica

tion to a school other than a segregated school main

tained for Colored people would have been futile; and

equity does not require the doing of a vain thing as a

condition of relief.”

School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen,

supra, 240 F. 2d. at pp. 63, 64.

The situation was almost identical in Gibson v. Board

of Public Instruction of Dade County, supra. The plaintiffs

had petitioned the Board of Public Instruction to abolish

racial segregation in the public schools as soon as practi

cable, and the Board had refused. Relying upon and quoting

from Chief Judge Parker’s opinion in the City of Charlottes

ville Case, supra, this Court held that: “Under the circum

stances alleged, it was not necessary for the plaintiffs to

make application for admission to a particular school.”

246 F. 2d. at p. 914.

At least two material distinctions exist between those

cases and the present case: First, in each of those cases

the plaintiffs had placed themselves on record as desir

ing practically the same relief as that sought from the court,

Here, in the absence of any attempt to apply for admis

sion to the Fred Wessels Homes, there is no reasonably

certain proof that the appellant actually desired in some

earlier year, say 1952, to become a tenant in that public

housing. Testimony, years after the critical event, as to

what one’s intentions were cannot take the place of acts

done at that time. Secondly, in each of the cases relied

on, it was admitted that discriminatory segregation of

the races was being enforced by the defendant Board,

while, as has already been indicated, in the present case,

in both the pleadings and the proof, governmentally en

forced segregation is denied.

29

In her reply brief, the appellant cites a third case in

support of her contention that she was not required to prove

that she applied for or was denied admission to the public

housing project, Staub v. City of Baxley, 1958, 355 U. S.

313. The pertinent holding in that case was thus expressed:

“ The first of the nonfederal grounds relied on by

appellee, and upon which the decision of the Court

of Appeals rests, is that appellant lacked standing to

attack the constitutionality of the ordinance because

she made no attempt to secure a permit under it. This

is not an adequate nonfederal ground of decision. The

decisions of this Court have uniformly held that the

failure to apply for a license under an ordinance

which on its face violates the Constitution does not

preclude review' in this Court of a judgment of convic

tion under such an ordinance. Smith v. Cahoon, 283

U. S. 553, 562; Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444, 452. ‘The

Constitution can hardly be thought to deny one sub

jected to the restraints of such an ordinance the right

to attack its constitutionality, because he has not yielded

to its demands.’ Jones v. Opelika, 316 U. S. 584, 602,

dissenting opinion, adopted per curiam on rehearing,

319 U. S. 103, 104.”

Staub v. City of Baxley, supra, 355 IT. S. at p. 319.

Clearly, that decision is not applicable here, for in that

case the appellant had a legal right to engage in the oc

cupation regardless of the ordinance, vdiile here a tenant

could not be admitted to a housing project without having

made an application. No one could reasonably contend that

by applying for admission to a public housing project the

appellant would be yielding to any unconstitutional demand.

We conclude that the appellant-plaintiff has no standing

to maintain this action when she has not been denied admis

sion to a public housing project on account of her race or

30

color. That is the very gist of her claim. Absent such

standing, there is no justiciable claim or controversy.10

Mr. Stillwell’s testimony has been noted (footnote 7,

supra) to the effect that in his opinion actual segregation

is essential to the success of a program of public housing in

Savannah. If the people involved think that such is the case

and if Negroes and whites desire to maintain voluntary

segregation for their common good, there is certainly no

law to prevent such cooperation. Neither the Fifth nor the

Fourteenth Amendment operates positively to command in

tegration of the races but only negatively to forbid govern-

mentally enforced segregation.11

The judgment of dismissal is

A f f i r m e d .

10 Associated Industries v. Iekes, 2nd Cir. 1943, 134 F. 2d 694,

700.

11 Cf Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent School District, 5th

Cir. 1957, 241 F. 2d 230, 233; Rippy v. Borders, 5th Cir. 1957,

250 F. 2d 690, 692.

31

Judgment of Court of Appeals

Extract from the Minutes of June 30, 1958

No. 16,866

Q u een C o h en ,

versus

P u blic H ousing A d m in istra tio n , et al.

This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of the

record from the United States District Court for the South

ern District of Georgia, and was argued by counsel;

On consideration whereof, It is now here ordered and ad

judged by this Court that the judgment of the said District

Court in this cause be, and the same is hereby, affirmed;

It is further ordered and adjudged that the appellant,

Queen Cohen, be condemned to pay the Costs of this cause

in this Court for which execution may be issued out of the

said District Court.

32

Order Denying Rehearing

Extract from the Minutes of August 11, 1958

No. 16,866

Qu een C o h en ,

versus

P u blic H ousing A d m in istra tio n , et al.

It is ordered by the Court that the petition for rehearing

filed in this cause be, and the same is hereby, denied.

33

APPENDIX B

Regulations, Statutes And Constitutional

Provisions Involved

HHFA

PHA

2-21-51 L ow -R e n t H ousing M an u al 102.1

Racial Policy

The following general statement of racial policy shall be

applicable to all low-rent housing projects developed and

operated under the United States Housing Act of 1937, as

amended:

1. Programs for the development of low-rent housing, in

order to be eligible for PHA assistance, must reflect

equitable provision for eligible families of all races

determined on the approximate volume and urgency of

their respective needs for such housing.

2. While the selection of tenants and the assigning of dwell

ing units are primarily matters for local determination,

urgency of need and the preferences prescribed in the

Housing Act of 1949 are the basic statutory standards

for the selection of tenants.

Title 42, United States Code, §1402:

(1) Low-rent housing. The term ‘low-rent housing’

means decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings within the

financial reach of families of low income, and developed

and administered to promote serviceability, efficiency,

economy, and stability, and embraces all necessary ap

purtenances thereto. The dwellings in low-rent hous

ing as defined in this Act [§1401 et seq. of this title]

shall be available solely for families whose net annual

income at the time of admission, less exemption of $100

34

for each minor member of the family other than the

head of the family and his spouse, does not exceed

five times the annual rental (including the value or

cost to them of water, electricity, gas, other heating

and cooking fuels, and other utilities) of the dwellings

to be furnished such families. For the sole purpose of

determining eligibility for continued occupancy, a pub

lic housing agency may allow, from the net income of

any family, an exemption for each minor member of

the family (other than the head of the family and

his spouse) of either (a) $100, or (b) all or any part

of the annual income of such minor. For the purposes

of this subsection, a minor shall mean a person less

than 21 years of age.

(14) Veteran. The term ‘veteran’ shall mean a per

son who has served in the active military or naval

service of the United States at any time (i) on or

after September 16, 1940, and prior to July 26, 1947,

(ii) on or after April 6, 1917, and prior to November

11, 1918, or (iii) on or after June 27, 1950, and prior

to such date thereafter as shall be determined by the

President, and who shall have been discharged or re

leased therefrom under conditions other than dishonor

able. The term ‘serviceman’ shall mean a person in

the active military or naval service of the United

States who has served therein at any time (i) on or

after September 16, 1940, and prior to July 26, 1947,

(ii) on or after April 6, 1917, and prior to November

11, 1918, or (iii) on or after June 27, 1950, and prior

to such date thereafter as shall be determined by the

President.

Title 42, United States Code, §1410(g ) :

(g) Veterans’ preference. Every contract made pur

suant to this Act [§1401 et seq. of this title] for annual

35

contributions for any low-rent housing project shall

require that the public housing agency, as among low-

income families which are eligible applicants for occu

pancy in dwellings of given sizes and at specified

rents, shall extend the following preferences in the

selection of tenants:

First, to families which are to be displaced by any

low-rent housing project or by any public slum-clear

ance, redevelopment or urban renewal project, or

through action of a public body or court, either through

the enforcement of housing standards or through the

demolition, closing, or improvement of dwelling units,

or which were so displaced within three years prior

to making application to such public housing agency

for admission to any low-rent housing: Provided, That

as among such projects or actions the public housing

agency may from time to time extend a prior prefer

ence or preferences: And Provided further, That, as

among families within any such preference group such

families first preference shall be given to families of

disabled veterans whose disability has been determined

by the Veterans’ Administration to be service-con

nected, and second preference shall be given to fami

lies of deceased veterans and servicemen whose death

has been determined by the Veterans’ Administration

to be service-connected, and third preference shall be

given to families of other veterans and servicemen;

Second, to families of other veterans and service

men and as among such families first preference shall

be given to families of disabled veterans whose dis

ability has been determined by the Veterans’ Admin

istration to be service-connected, and second prefer

ence shall be given to families of deceased veterans

and servicemen whose death has been determined by

the Veterans’ Administration to be service-connected.

36

Title 42, United States Code, §1415:

(8) Every contract made pursuant to this Act [§1401

et seq. of this title] for annual contributions for any

low-rent housing project initiated after March 1, 1949,

shall provide that—

(a) the public housing agency shall fix maximum

income limits for the admission and for the continued

occupancy of families in such housing, that such maxi

mum income limits and all revisions thereof shall be

subject to the prior approval of the Authority [Public

Housing Administration], and that the Authority

[Public Housing Administration] may require the pub

lic housing agency to review and to revise such maxi

mum income limits if the Authority [Public Housing

Administration] determines that changed conditions

in the locality make such revisions necessary in achiev

ing the purposes of this Act [§1401 et seq. of this title];

(b) a duly authorized official of the public housing

agency involved shall make periodic written statements

to the Authority [Public Housing Administration] that

an investigation has been made of each family ad

mitted to the low-rent housing project involved during

the period covered thereby, and that, on the basis of

the report of said investigation, he has found that

each such family at the time of its admission (i) had

a net family income not exceeding the maximum in

come limits theretofore fixed by the public housing

agency (and approved by the Authority [Public Hous

ing Administration]) for admission of families of low

income to such housing; and (ii) lived in an unsafe,

insanitary, or overcrowded dwelling, or was to be dis

placed by any low-rent housing project or by any

public slum-clearance, redevelopment or urban renewal

project, or through action of a public body or court,

37

either through the enforcement of housing standards

or through the demolition, closing or improvement of

a dwelling unit or units, or actually was without hous

ing, or was about to be without housing as a result of

a court order of eviction, due to causes other than the

fault of the tenant: Provided, That the requirement in

(ii) shall not be applicable in the case of the family of

any veteran or serviceman (or of any deceased veteran

or serviceman) where application for admission to such

housing is made not later than March 1, 1959.

(c) in the selection of tenants (i) the public housing

agency shall not discriminate against families, other

wise eligible for admission to such housing, because

their incomes are derived in whole or in part from

public assistance and (ii) in initially selecting fami

lies for admission to dwellings of given sizes and at

specified rents the public housing agency shall (subject

to the preferences prescribed in subsection 10 (g) of

this Act [§1410(g) of this title]) give preference to

families having the most urgent housing needs, and

thereafter, in selecting families for admission to such

dwellings, shall give due consideration the urgency of

the families’ housing needs; and . . .

Title 42, United States Code, §1982:

1982. Property rights of citizens.—All citizens of

the United States shall have the same right, in every

State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white citizens

thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and con

vey real and personal property.

Title 42, United States Code, §1983:

1983. Civil action for deprivation of rights.—Every

person who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

38

regulation, custom or usage, of any State or Territory,

subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the

United States or other person within the jurisdiction

thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or

immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall

be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit

in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress.

Constitution of the United States:

Amendment 5—Due Process Clause

“ No person shall be . . . deprived of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law . . . ”

Amendment 14, §1—Due Process and Equal Protection

Clauses:

“ * * * nor shall any State deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor

deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws.”

39

APPENDIX C

Opinion o f United States District Court, District

o f Columbia, Filed May 8, 1953

I n th e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob th e D isteict of C olum bia

Civil Action No. 3991—52

(Filed May 8, 1953)

H eyw ard , et al.,

Plaintiffs,

—v.—

H ousing and H ome F in an ce A gency , et al.,

Defendants.

The Court: This is an action to restrain the Commis

sioner of the Public Housing Administration from advanc

ing any funds under the United States Housing Act of 1937,

as amended, and otherwise participating, in the construc

tion and operation of certain housing projects in the City

of Savannah, Georgia.

These projects are being constructed and will be operated

by local authorities with the aid of Federal Funds.

The basis of the action is that it has been officially an

nounced that the project referred to in the complaint will

be open only to white residents. The plaintiffs are people

of the colored race who contend that such a limitation is a

violation of their Constitutional rights.

40

The Court has grave doubt whether this action lies in

the light of the doctrine enunciated in the case of Massa

chusetts v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447, but assuming, arguendo,

that the action may be maintained, the Court is of the

opinion that no violation of law or Constitutional rights

on the part of the defendants has been shown.

It appears from the affidavit submitted in support of the

defendants’ motion for a summary judgment that there

are several projects that have been or are being constructed

in the City of Savannah under the Housing Act, some of

which are limited to white residents and others to colored

residents, and that a greater number of accommodations

has been set aside for colored residents. In other words,

we have no situation here where colored people are being de

prived of opportunities or accommodations furnished by

the Federal Government that are accorded to people of the

white rice. Accommodations are being accorded to people

of both races.

Under the so-called “ separate but equal” doctrine, which

is still the law under the Supreme Court decisions, it is

entirely proper and does not constitute a violation of Con

stitutional rights for the Federal Government to require

people of the white and colored races to use separate facili

ties, provided equal facilities are furnished to each.

There is another aspect of this matter which the Court

considers of importance. The Congress has conferred dis

cretionary authority on the administrative agency to de

termine for what projects Federal funds shall be used.

There are very few limitations in the statute on the power

of the administrator, and there is no limitation as to racial

segregation.

The Congress has a right to appropriate money for such

purposes as it chooses under the General Welfare clause

of Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution. It has a right

to appropriate money for purpose “A ” but not for pur

pose “ B,” so long as purpose “A ” is a public purpose.

41

Under the circumstances, the Court is of the opinion

that the plaintiffs have no cause of action and the defen

dants’ motion for summary judgment is granted.

(Thereupon, the above entitled matter was concluded.)

A lexander H oltzoff ,

District Judge.

'