Correspondence to and from co-counsel; from Blumenthal to Judge Hammer

Correspondence

August 17, 1992 - August 31, 1992

10 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Correspondence to and from co-counsel; from Blumenthal to Judge Hammer, 1992. e69c87fb-a246-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a7e7d58d-7897-4ecd-baaf-40cb993c0f0b/correspondence-to-and-from-co-counsel-from-blumenthal-to-judge-hammer. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

|

1

National Office

A A

Suite 1600

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE 99 Hudson Street

| AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. New York, N.Y. 10013-2897 (212) 219-1900 Fax: (212) 226-759:

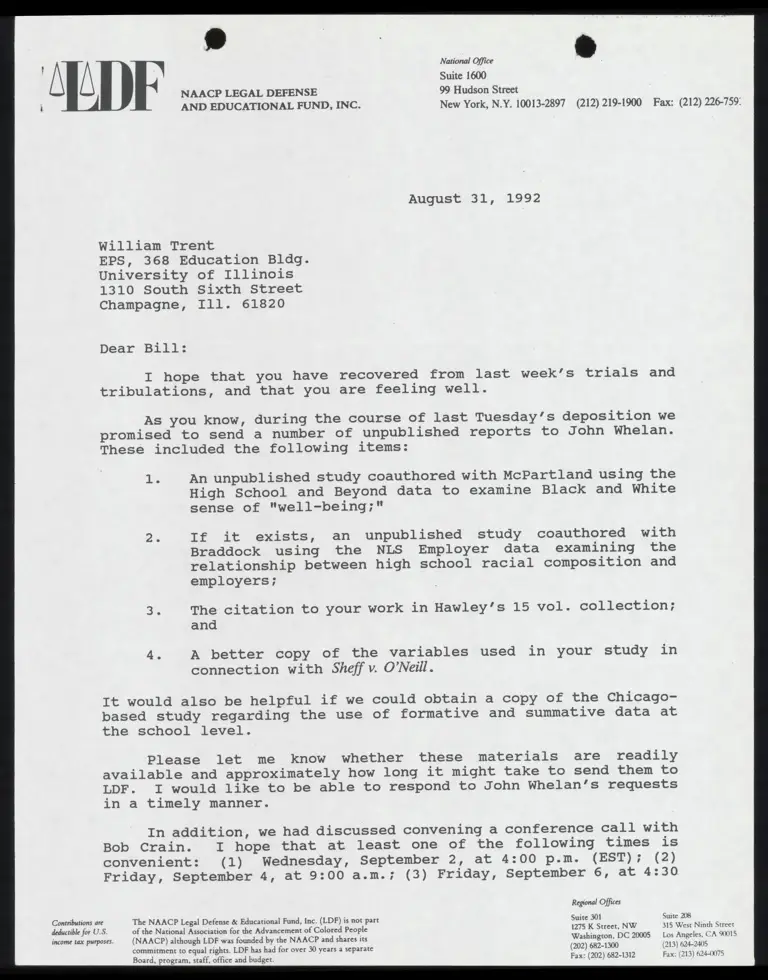

August 31, 1992

William Trent

EPS, 368 Education Bldg.

University of Illinois

1310 South Sixth Street

Champagne, Ill. 61820

Dear Bill:

I hope that you have recovered from last week’s trials and

tribulations, and that you are feeling well.

As you know, during the course of last Tuesday’s deposition we

promised to send a number of unpublished reports to John Whelan.

These included the following items:

1. An unpublished study coauthored with McPartland using the

High School and Beyond data to examine Black and White

sense of "well-being;"

2. If it exists, an unpublished study coauthored with

Braddock using the NLS Employer data examining the

relationship between high school racial composition and

employers;

3. The citation to your work in Hawley’s 15 vol. collection;

and

4. A better copy of the variables used in your study in

connection with Sheff v. O'Neill.

It would also be helpful if we could obtain a copy of the Chicago-

based study regarding the use of formative and summative data at

the school level.

Please let me know whether these materials are readily

available and approximately how long it might take to send them to

LDF. I would like to be able to respond to John Whelan’s requests

in a timely manner.

In addition, we had discussed convening a conference call with

Bob Crain. I hope that at least one of the following times is

convenient: (1) Wednesday, September 2, at 4:00 p.m. (EST): (2)

Friday, September 4, at 9:00 a.m.; (3) Friday, September 6, at 4:30

Regional Offices

Suite 208

Contributions are The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is not part Suite 301

315 West Ninth Street

deductible for U.S. of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People 1275 K Street, NW

income tax purposes. (NAACP) although LDF was founded by the NAACP and shares its Washington, DC 20005 Los Angeles, CA 90015

commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 30 years a separate (202) 682-1300

Board, program, staff, office and budget.

(213) 624-2405

Fax: (202) 682-1312 Fax: (213) 624-0075

| I J

p.m. Please let me know which times fit into your schedule. I

will call Bob Crain and Sandy DelValle to confirm arrangements.

Thank you for your continuing enthusiasm. Your participation

in this case is much appreciated.

Sincerely,

Marianne Engelman Lado

cc. Robert Crain

Sandy DelValle

Ron Ellis

i

y

I

|

|

|

|

i

i

|

;

:

-

T

A

f

i

i

$ i

§

]

{

:

y

)

|

¥

|

w

l

i

3

i

4

1

|

i

Eid

i

i

J

i

i

|

|

| !

|

]

:

J

]

|

|

|

i

|

|

Bi

1

"

I

|

|

—

i

| |

|}

4

i i)

: gon] i

Re

n

t

l

]

i

oe

$k

T ’Ly

=4

National Office

A A

Suite 1600

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE 99 Hudson Street

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. New York, N.Y. 10013-2897 (212) 219-1900 Fax: (212) 226-7592

August 20, 1992

Martha Stone, Esq.

Connecticut Civil Liberties

Union

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

Dear Martha:

Below please find a list of materials by or relating to David

Armor. Please let me know if you want these reproduced.

1. Armor Deposition, U.S v. Charleston County, S.C. , (1987):

Direct by Santos (U.S. Dept. of Justice), Cross by Henderson

(Pittsburg) ;

2. Armor Testimony, Charleston County: Direct by Lindseth, Cross

by Glassman, Henderson;

3. Armor’s Testimony on behalf of Woodland Hills School District,

Hoots: Direct and Redirect by Rutter, Cross by Henderson;

4. Armor Testimony, Nichols v. Natchez (1989): Direct by Adams,

Cross by Byrd (LDF), Beber, Redirect by Adams, Recross by

Beber;

5. Armor Deposition, Nichols v. Natchez: Examination by Chachkin

(LDF), Beber;

6. Armor Testimony, Riddick v. Norfolk (1984): Cross by Williams

(LDF), Redirect by Stalnaker with catalogue of complete

testimony and abstract of deposition;

7. Armor Testimony, Stell v. Chatham County (1988): Direct by

Lindseth, Cross by Johnston (LDF), Marks;

8. Armor Deposition, Stell v. Chatham County (1988): Examination

by Marshall (U.S. Dept. of Justice), Johnston (LDF);

9, Armor Interview, "Profiles in Education," Education Update

(Heritage Foundation: 1990);

Regional Offices

Suite 208

1275 K Street, NW 315 West Ninth Street

Washington, DC 20005 Los Angeles, CA 90015

(202) 682-1300 (213) 624-2405

Fax: (202) 682-1312 Fax: (213) 624-0075

Contributions are The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is not part Suite 301

deductible for U.S. of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

income tax purposes. (NAACP) although LDF was founded by the NAACP and shares its

commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 30 years a separate

Board, program, staff, office and budget.

10.

11.

12.

1s.

14.

15.

16.

1;.

18.

19.

20.

E

Armor, "Unwillingly to School," Policy Review (Heritage

Foundation: 1981);

Armor Report to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, "The Racial

Composition of Schools and College Aspirations of Negro

Students";

Articles with reference to Armor:

a. Pear, "Advisor to U.S. Desegregation Study

Quits, Saying It’s Biased" New York Times

(October 30, 1985);

ba Hiatt, "Norfolk Shelves Its Plan to Kill

Crosstown Busing" Washington Post (June 10, 1982);

C. Feinberg, "Busing Orders Said to Widen

Isolation" Washington Post (May 15, 1981);

qd. Seligman, "The Busing Religion" Fortune (October

9, 1978);

e. Fields, "Choosing Education Excellence"

Washington Times (July 11, 1989);

Armor, "After Busing: Education and Choice" (1989);

Armor, "The Double Double Standard: A Reply" The Public Interest ;

Armor, "School and Family Effects on Black and White

Achievement: A Re-examination of the USOE Data";

Armor, "School Busing: A Time for Change" (1988);

Armor, "White Flight Demographic Transition and the Future of

School Desegregation";

Armor, "Why Is Black Educational Achievement Rising?" Public

Interest (1992);

Armor C.V; and

Memo by Jenkins (LDF) Regarding Approaches to Expert Testimony

by Armor (May 20, 1992).

® a »

Please let me know if I can be of assistance with preparations

for Armor’s deposition. At this point, I plan to be in Hartford on

September 3 for the deposition.

Cheers,

Marianne Engelman Lado

MEL: ja

cc: Ron Ellisv

National Office

A A Suite 1600

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE 99 Hudson Street

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. New York, N.Y. 10013-2897 (212) 219-1900 Fax: (212) 226-75¢

August 20, 1992

John R. Whalen

Assistant Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General

State of Connecticut

MacKenzie Hall

110 Sherman Street

Bartford, CT 06105

Re: Sheff v. O'Neill: Lost Diskette

Dear John:

Enclosed please find a second diskette containing the

requested data used by Dr. Robert Crain. I am sending

by overnight mail in order to ensure speedy delivery.

the diskette

Please let me know if any additional problems arise regarding

this diskette.

Sincerely,

LET.

Marianne ‘Engelman Lado

cc. Philip Tegeler, Esq.

Martha Stone, Esq.

Martha M. Watts, Asst. Atty. Gen.

Contributions are The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is not part

deductible for U.S. of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

income tax purposes. (NAACP) although LDF was founded by the NAACP and shares its

commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 30 years a separate

Regional Offices

Suite 301 Suite 208

1275 K Street, NW 315 West Ninth Street

Washington, DC 20005 Los Angeles, CA 9015

(202) 682-1300 (213) 624-2405

Mackenzie flail

110 Sherman Strect

Hartord. CT 061035

RiCTLARDY BLUMENTHAL

ATTORNEY GENERAL

FAX (203) d2:3-33:36

Ottice of The Attorney General

State of Connecticut

Tel: 566-7173

August 17, 1992

The Honorable Harry Hammer

Judicial District at Hartford

95 Washington Street .. Ted i

P.O. Drawer D, Station A

Hartford, CT 06106

The Honorable Harry Hammer

Judicial District at Rockville

l Court Street

P.O. Box 424

Rockville, CT 06066

RE: SHEFF v. O'NEILL

Dear Judge Hammer:

On August 26, 1992, counsel for the parties in the

above-captioned case are scheduled to appear before Your Honor

for a. status conference. At the conference, the defendants will

be requesting that certain matters be considered on the record.

Consequently, we request that a court reporter be present at the

status conference in order to make a formal record of the

proceedings.

Thank you for your consideration.

Very truly yours,

: M&r thay.

Assistant Attorney General

MMW: ac

ce: "John ‘Brittain, Fsq. Ruben Franco, Esq.

Wilfred Rodriguez, Esg. Jenny Rivera, Esq.

Philip Tegeler, Esg. Julius Chambers, Esq.

Martha Stone, Esq. Marianne Lado, Esq.

Wessley W. Horton, Esg. John A. Powell, Esq.

Helen Hershkoff Esqg. «Helen Hershkoff, Esq.’

Adam S. Cohen, Esq. John R. Whelan, Asst. Atty. Gen.