Opinion and Order

Public Court Documents

October 21, 1976

56 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Opinion and Order, 1976. 470b1289-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a7f89049-78fb-4191-a0be-7db5644730cb/opinion-and-order. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

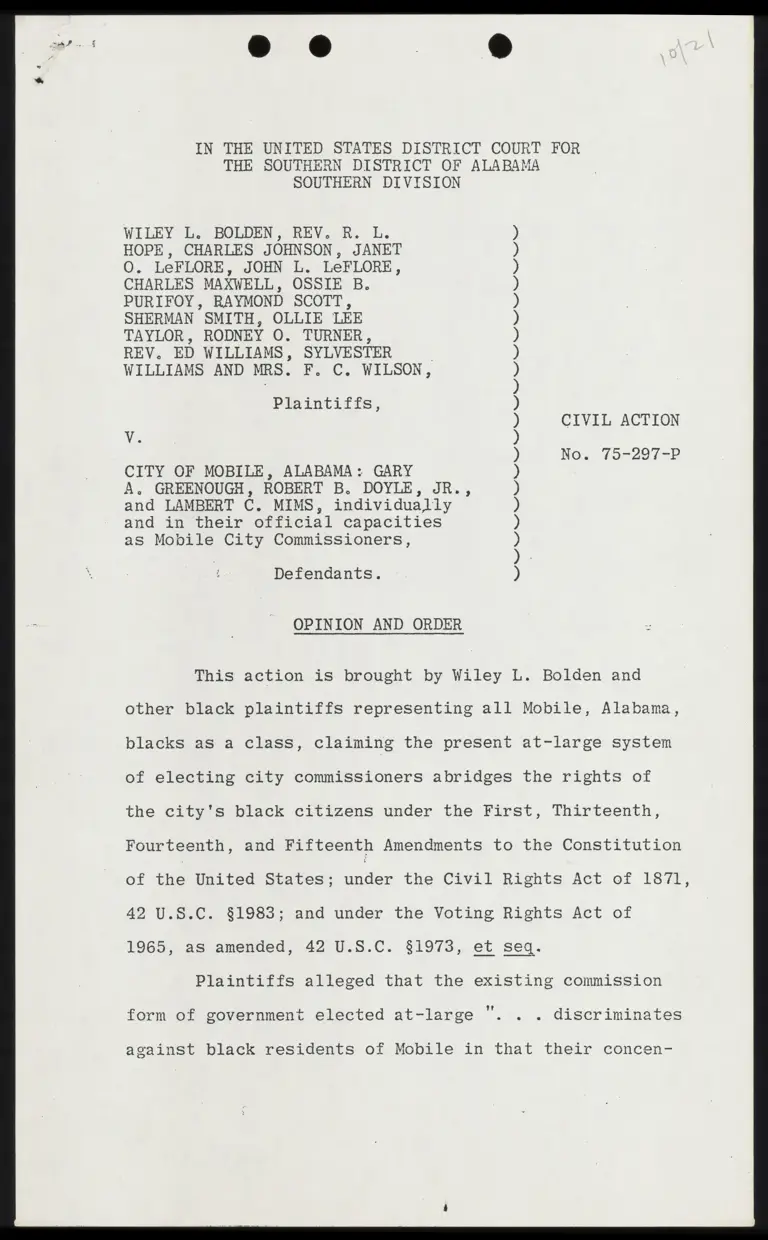

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, REV. R. L.

HOPE, CHARLES JOHNSON, JANET

0. LeFLORE, JOHN L. LeFLORE,

CHARLES MAXWELL, OSSIE B.

PURIFOY, RAYMOND SCOTT,

SHERMAN SMITH, OLLIE LEE

TAYLOR, RODNEY O. TURNER,

REV. ED WILLIAMS, SYLVESTER

WILLIAMS AND MRS. F. C. WILSON,

Plaintiffs,

CIVIL ACTION

Y.

No. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA: GARY

A. GREENOUGH, ROBERT B. DOYLE, JR.,

and LAMBERT C. MIMS, individually

and in their official capacities

as Mobile City Commissioners,

Defendants. N

e

’

No

No

S

o

N

o

No

o

Na

?

So

o

S

o

ot

No

o

oo

oo

oo

o

t

No

o?

N

o

oo

N

o

No

N

I

OPINION AND ORDER

This action is brought by Wiley L. Bolden and

other black plaintiffs representing all Mobile, Alabama,

blacks as a class, claiming the present at-large system

of electing city commissioners abridges the rights of

the city's black citizens under the First, Thirteenth,

Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States; under the Civil Rights Act of 1871,

42 U.S.C. §1983; and under the Voting Rights Act of

1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. 81973, et seq.

Plaintiffs alleged that the existing commission

(a4

form of government elected at-large . discriminates

against black residents of Mobile in that their concen-

trated voting strength is diluted and canceled out by

the white majority in the City as a whole" with a con-

sequent violation of their rights under the above

Amendments to the Constitution. It is also claimed

that their statutory rights under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973,

et seq. [Voting Rights Act of 1965] and 1983 [Civil

Rights Act of 1871] were violated. Jurisdiction is

premised upon 28 U.S.C. §1343(3) 2nd (4).

This court has jurisdiction over the claims

based on 42 U.S.C. 81983 against the City Commissioners

and over the claims grounded on 42 U.S.C. §1973 against

all defendants under 28 U.S.C. §1343(3)-(4) and §2201.

This cause was certified as a class action under

Rule 23(b)(2), F.R.C.P., the plaintiff class being all

Alabama.

A claim originally asserted under 42 U.S.C.

§1985(3) was dismissed for failure to state a claim upon

which relief can be granted.

Defendants are the three Mobile City Commissioners,

sued in both their individual and official capacities.

The prayed-for relies consists of, (1) a declara-

tion that the present at-large election system is un-

constitutional, (2) an injunction preventing the present

commissioners from holding, supervising, or certifying.

any future city commission elections, (3) the formation

of a government whose legislative members are elected

from single member districts, and (4) costs and attorney

-2-

fees,

Plaintiffs claim that to prevail they must

prove to this court's satisfaction the existence of

the elements probative of voter dilution as set forth

by White v. Regesier, 412 U. 8. 733, 93 8. Ct. 2342,

37 L.Ed.2d 314 (1973), and Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485

F.24 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) (en banc), aff'd. sub nom.

East Carroll Parish School Board V. Marshall, vis,

Lae OBS, Ct. 1083, 47 L.Ed.2d 296 (1976), contending

Zimmer is only the adoption of specified criteria by

the Fifth Circuit of the White dilution remnivensnts.

The defendants stoutly contest the claim of

unconstitutionality of the city government as measured

by White and Zimmer. They contend Washington v. Davis,

U.S. , 906 8. Ci. 2040, 48 1.54.24 597 (1976);

erects a barrier since the 1911 legislative

act forming the multi-member, at-large election of the

commissioners was without racial intent or purpose.

They assert Washington, supra, 96 S. Ct. at 2047-49,

which was an action alleging due process and equal

protection violations, held that in these constitu-

tional actions, in order to obtain relief, proof of

intent or purpose to discriminate by the defendants

must be shown. Defendants state, therefore, that since

the statute under which the Mobile Commission government

operates was passed in 1911, with essentially all blacks

disenfranchised from the electorate by the Alabama 1901

convention, there could be no intent or purpose to dis-

criminate at the time the statute was passed. Alterna-

-3-

tively, however, defendants contend that if Washington

does not preclude consideration of the dilution factors

of White and Zimmer, they should still prevail because

plaintiffs have not sustained their burden of proof

under these and subsequent cases.

Plaintiffs’ reply is to the effect that Washington

did not establish any new constitutional purpose princi-

ple and that White and Zimmer still are applicable. If,

however, this court finds Washington to require a show-

ing of racial motivation at the time of passage, or

merely in the retention of the statute, plaintiffs con-

tend they should still Prevails claiming the at-large

election system was designed and is utilized with the

motive or purpose of diluting the black vote. Plaintiffs

claim that the discriminatory intent can be shown under

the traditional tort standard.

FINDINGS OF FACT

Mobile, Aabamn, is the Rodond largest city in

Alabama located at the confluence of the Mobile River

and Mobile Bay in the southwestern part of the state.

Mobile's 1970 population was 190,026 with approximately

35.4% of the residents ARI

1/ Defendants' Exhibit No. 12. According to the 1970

Federal Census, the City of Mobile had a total pop-

ulation of 190,026 of whom 35.4%, or 67,356, were

non-white. The evidence is clear that there are .

few non-whites other than blacks.

1973 Mobile County voters statistics RUIN that

89.6% of the voting age white population is registered

to vote, 63.4% of the blacks are registered. (Plain-

tiffs’ Exhibit No. 7).

Mobile geographically encompasses 142 square

miles. Most of the white residents live in the southern

and western parts of the city, while most blacks live

in the central and northern sectors (Plaintiffs' Exhibit

No. 58). Housing patterns have been, and remain, highly

segregated. Certain areas of the city are almost totally

devoid of black residents while other areas are virtually

all black. In a recent study by the Council on Municipal

Performance, using 1970 block census data, Mobile was

found to be the 95th most residentially segregated of

the 109 municipalities surveyed (Plaintiffs’' Exhibit

No. 59). According to a study performed by the Universi-

ty of South Alabama Computer Center for the defendants,

the housing patterns in the city are so segregated it

is impossible to divide the city into three contiguous

zones of equal population without having at least one

predominantly black district (Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 60).

Segregated housing patierns have resulted in concentration

of black voting power.

Mobile presently operates under a three person

commission-type municipal government adopted in 1911.

(Ala. Act No. 281 (1911) p. 330). The commissioners

are elected to direct one of the following three municipal

departments: Public Works and Services, Public Safety,

-5--

2

and Department of Elnaieo

2/ When adopted in 1911, Mobile's commission government

did not specify that a candidate must choose the

particular commission position for which he was run-

ning. Alabama Act No. 823 (1965), p. 1539, however,

inter alia, required candidates to run for a partic-

ular numbered position with specific duties. Each

commissioner holds that position during the four

years tenure with the mayorality rotating between

commissioners every sixteen months.

The commissioners run on a place-type ballot and

are elected at-large by the voters of Mobile. While the

commission candidates must be residents of Mobile, there

is not now, or has there ever been, a requirement that

each commissioner reside in a particular part of the

city. The evidence clearly indicates that district

residence requirements with district elections would be

improvident and unsound for the commission form of :

government.

In addition to the specific position for which

a commissioner runs, each is also responsible for num-

erous appointments to the 46 committees operating under

the auspicies of the city. Some appointments are com-

pletely discretionary with the commissioner whereas

committees, such as the plumbing and air conditioning

boards which require members with a certain amount of

expertise, are filled with a nominee suggested by the

local trade association. Often, the appointing com-

missioner makes his appointment from the slate of nom-

inees presented by the particular association. This

means that if the nominating association does not propose

a black as a committee member, the commissioner will not

-6-

appoint one. It is, however, within the commission's

power to modify or change the ground rules under which

appointments are made.

In Zimmer, supra, aff'd. sub nom. East Carroll

Parish School Board, supra,(”. . . but without approval

of the constitutional views expressed by the court of

appeals.'), the Fifth Circuit synthesized the White

opinion with the Supreme Court's earlier Whitcomb v.

Chavis, 403 U. 8S. 124, 91 8, Ct. 1858, 20 L.E4.2d4 383

(1971), decision, together with its own opinion in

Lipscombe v. Jonsson, 459 F.2d 335 (5th Cir. 1972) and

set out certain factors to be considered.

Based on these. factors as set out in Zimmer,

supra, at 1305, the court makes the following findings

with reference to each of the primary and enhancing

factors:

LACK OF OPENNESS IN THE SLATING PROCESS

OR CANDIDATE SELECTION PROCESS TO BLACKS.

Mobile blacks were subjected to massive official

and private racial discrimination until the Voting Rights

Act of 1965. It has only been since that time that sig-

nificant diminution of iliese discriminatory practices

has been made. The overt forms of many of the rights

now exercised by all Mobile citizens were secured through

federal court orders together with a moral commitment of

many of its dedicated white and black citizens plus the

power generated by the restoration of the right to vote

which substantially increased the voting power of the

blacks. Public facilities are open to all persons.

Job opportunities are being opened, but the highly

visible job placements in the private sector appear

to lead job placements in the city government sector.

The pervasive effects of past discrimination still

substantially affects political black participation.

There are no formal prohibitions against blacks

- i

seeking office in Mobile.Y Since the Voting Rights

3/ The qualifying fee for candidates for the city com-

mission was found unconstitutional in Thomas v.

Mins, 317 F. Supp. 179 .(S.D. Ala. 1970). See also

Ue SB. v. State of Ala., 252 F. Supp. 95 (M.D. Ala.

1966) (three judge District Court panel) (poll

tax declared unconstitutional). =

Act of 1965, blacks register and vote without hindrance.

The election of the city commissioners is non-partisan,

i.e., there is no preceding party primary and the candi-

dates do not ordinarily run under party 1abels. However,

the court has a duty to look deeper rather than rely on

surface appearance to determine if there is true open-

ness in the process and determine whether the processes

"leading to nomination and election [are] . . .

equally open to participation by the group in ques~-

tion. . . ." White, 412 U. §. at 766. One indication

that local political processes are not equally open is

the fact that no black person has ever been elected to

"the at-large city commission

Be

I

office. This is true although the black population

level is in excess of one-third.

In the 1960's and 1970's, there has been general

polarization in the white and black voting. The polari-

zation has occurred with white voting for white and

black for black if a white is opposed to a black, or

if the race is between two white candidates and one

candidete iS identified with 4 favorable vote in the

black wards, or identified with sponsoring particularized

‘black needs. When this occurs, a white backlash occurs

which usually results in the defeat of the bizck candidate

or the white candidate identified with the blacks.

Since 1962, four black candidates have sought

election in the at-large county school board election.

Dr. Goode in 1962, Dr. Russell in 1966, Ms. Jacobs in

1970, and Ms. Gill in 1974. All of these black candi-

dates were well educated and highly respected members

of the black community. They all received good support

from the black voters and virtually no support from

whites. They all lost to white opponents in run-off elec-

tions. | |

Three black cendidaton entered the race of the

Mobile City Commission in 1973. Ollie Lee Taylor,

Alfonso Smith, and Lula Albert. They received modest

support from the black community and virtually no sup-

port from the white community. They were young, inexperi-

enced, and mounted extremely limited campaigns.

Two black candidates sought election to the Alabama

State Legislature in an at-large election in 1969. They

cng 5°

were Clarence Montgomery and T. C. Bell. Both were

‘well supported from the black community and both lost

to white opponents.

Following a three-judge federal court order

| 24

in 1072% in which single -member districts were estab-

4/ Sims v. Amos, 336 F. Supp. 924 (M.D. Ala. 1972).

lished and the house and senate seats reapportioned,

one senatorial district in Mobile County had an almost

equal division between the black and white population.

A black and white were in thé run-off. The white won

by 300 votes. There was no overt acts of racism.

Both candidates testified or asserted each appealed to

. | both races. It is interesting to note that the white

winner phblienied a simulated ASnSpaueH with both can-

didate's photographs appearing on the front page, one

under the other, one white, one black. |

One city commissioner, Yosouk N. Langan, who

served from 1953 to 1969, hod Been Slecied and reelected

with black support until the 1965 Voting Rights Act

enfranchised large numbers of blacks. His reelection

campaign in 1969 foundered mainly because of the fact

of the backlash from the black support and his identi-

fication with attempting to meet the particularized

needs of the black people of the city. He was again

defeated in an at-large county commission race in 1972.

Again the backlash because of the black support sub-

stantially contributed to his defeat.

-10-

In 19689, a black got in a Pinot against a white

in an at-large legislature race. There was an agreement

between various white. prospective candidates not to run

or place an opponent against the white in the run-off

so as not to splinter the white vote. The white won and

the black lost.

Practically all active candidates for public

office testified it is highly unlikely that anytime in

the foreseeable future, under the at-large system, that

a black can be elected against a white. Most of them

agreed that racial polarization was the basic reason.

The plaintiffs introduced statistical analyses known

as 'regression analysis" which supported this view.

Regression analysis is a proteRsionally accepted method

of analyzing data to determine the extent of correlation

between dependent and indegendent variables: In plain-

tiffs' analyses, the dependent variable was the vote

received by the candidates studied. Race and $node

were the independent variables whose influence on the

vote received was measured by the regression. There is

little doubt that race has a strong correlation with

the vote received by a candidate. These analyses

covered every city commission race in 1965, 1969, and

1973, both primary and general election of county com-

niSsion in 1968 and 1972, and selected school board

races in 1962, 1966, 1970, 1972, and 1974. They also

covered referendums held to change the form of city

government in 1963 and 1973 and a countywide legislative

race in 1969. The votes for and against white candidates

-11-

Con A AI er a, tht yt rt — a | S011 2 x oi 0 2 A — = fy WO —— nV | 5 ———_————————— po SW" S11. Sg oA Yar P—— eS tn St, Se —

x 5 . - - - - . . - - - - - Cay - -

-; J — “ve. - : we y 2 Eom. . Rs. * ta, REL Sims Swe aa A hat he I ene an a a ES SS Nh on Se a Sone WE mae Dayar rir om tr I EB 000 nl CT 2 LD 2 nr vr rem TT NT

such as Joe Langan in an at-large city commission race,

and Gerre Koffler, at-large county school board commis-

sion, who were openly associated with black community

interests, showed some of the highest racial polariza- -

tion of any elections.

Since the 1972 creation of single -member district,

three black of the present fourteen member Mobile County

delegation have been elected. Their districts are more

heavily populated with blacks than whites.

Prichard, an adjoining municipality to Mobile,

which in recent years has obtained a black majority

population, elected the first black mayor and first

black councilman in 1972.

Black candidates at this time can only have a

rams

——

reasonable chance of being elected where they have a

majority or a near majority. There is no reasonable

expectation that a black candidate could be elected

in a citywide election race because of race polariza-

tion. The court concludes that an at-large system is

an effective barrier to blacks seeking public life.

"This fact is shown by the removal of such:a barrier, 1.6.

the disestablistment of the multi-member at-large elec-

tions for the state legislature. New single member

districts were created with racial compositions that

offer blacks a chance of being elected, and they are

being elected.

The court finds that the structure of the at-large

election of city commissioners combined with strong

-

-12-

racial polarization of Mobile's electorate continues

to effectively discourage qualified black ettiuens from

seeking office or being elected thereby denying blacks

equal access to the slating or candidate selection

process.

UNRESPONSIVENESS OF THE ELECTED CITY

OFFICIALS TO THE BLACK MINORITY.

The at-large elected city commissioners have

not been responsive to the minorities’ needs. The

1970 population of the city is 64.5% white and 35.4%

black. ’

5/ See Footnote 1, supra.

The City of Mobile is one Bf the larger employers

in southwestern Alabama. It provided a living for

1,858 persons in 1975. 26.3% were black. It is Signific

cant to note, that if the lowest job classification,

service/maintenance, were removed from our consideration,

only 10.4% of the employees would be black. Likewise,

removing the lowest salary classification, less than

$5,900 per year, only 13.8% of all city ennlivens are

black. (Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 73).

The Mobile Fire Department has only fifteen

black employees out of a total of four hundred and

thirty-five employees. It took an order of this court

in Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 F. Supp. 1134 (S/D Ala.

-13-

cert. denied 412 U.S. 909 (1973)

1971, aff'd. 466 F.2d 122 (5th Cir. 1972),/ to desegregate

the Mobile Police Department. That order set out guide-

lines designed to remove racial discrimination in hiring,

promoting, assigning duties, and the rendering of ser-

vices. The city is also operating under another cont

order enjoining racial discrimination, Anderson v. Mobile

County Commission, Civil Action No. 7388-72-H (S/D Ala.

1973). The municipal golf course was desegregated only

after litigation in federal court, Sawyer v. City of

Mobile, 208 F. Supp. 548 (S/D Ala. 1961). This court

in Evans v. Mobile City Lines, Inc., Civil Action No.

2193-63 (S/D Ala. 1963), deli with segregation in

public transportation, and in Goole Lo Maniln, Civil

Action No. 2634-63 (S/D Ala. 1963), dealt with segre-

gation at the city airport. = : IRE a

| There are 46 city committees with a total member-

ship of approximately 482. Forty-seven are black and

435 are white. The total prior membership is 179 of -

which only 7 were black. (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 64).

| The Industrial Development Board has fifteen |

members and no blacks and concerns itself with imple-

menting a state law known as the "Cater Act” and the

authorization of the issuance of municipal bonds for

various business enterprises. J

| Seven committees were organized by private

investment groups for the purpose of securing municipal

bonding and the black-white makeup of these groups can-

not be charged to the city commission. That total mem-

-14-

bership is @ 21 ®uen the veibereW of these seven

committees cannot be charged to the city commissioners,

the absence of blacks indicates the permeating results

of past Facial Qiscrimination in the economic life of

Mobile business. This is indicated both from the absence

of blacks in the investment groups making use of munici-

pal bonds and ih that no black or black financial insti- 7

tutions have been able to take advantage of municipal bonds.

The Board of Adjustment, which consists of seven

members, has one black. This is 8:critical board. It

can grant variances from zoning laws and building codes

‘involving less than two acres. The Codes Advisory

Committee consists of 17 members and no blacks. This

committee Coli Ties all building regulations for all

. structures in the city. | |

The Mobile Housing Board supervises public housing.

Re

ow

Public Rousing is occupied predominantly by blacks.

Fifty thousand persons, approximately 25% of Mobile's

population, most of whom are black, cannot buy or rent

without subsidies in the private sector, or live in sub-

standard housing S/ There is one black on :that board

6/ All of these are not in public housing. There are

approximately 3,376 public housing units in the city

with approximately 12,153 occupants.

out of a membership of five.

The Rdnctionsl Board provides plans and means

to aid ta employees in a continuing education program.

It has nine members, none of whom are black. The county

school system has approximately 55% white and 45% black

-15-

7

population. The black dropout rate from school is

7/ The school system is countywide under the supervi-

sion of the Board of School Commissioners. The

school system was desegregated in the case of

Birdie Mae Davis v. Board of School Commissioners,

Civil Action No. 3003-63-H, pending, and is under

the continuing supervision of this court. The

city commission cannot be charged with any lack

of responsiveness in the Birdie Mae Davis case.

That case illustrates the permeation of racial

discrimination in the city which constitutes two-

thirds of the county's population.

higher than whites, therefore, the continuing education

is most important to them. |

There are several boards, to wit, Air-Conditioning,

Architectural Board, Board of Examining Engineers, and

Board of flectrical Examiners, which require special

skills. There are 17 members of these boards, all

white. Norio) census figures indicate that there are

far less blacks in skilled Sr ouDS than whites. The court

recognizes that qualified persons should be appointed,

but black membership becomes critical on such committees

‘because it is through these committees that licenses

are granted to skilled occupations. The absence of

blacks shows an insensitivity to this particularized

need. | |

The city has not taken ~~. affirmative action to

place blacks on these critical boards.

Most of the other committees are of various

social and cultural nature in the city. No effort has

been made to bring blacks into the mainstream of the

social and cultural life by appointing them in anything

-16-

more than token numbers. There are only three blacks

out of 46 members on the Bicentennial Committee and

only three out of 14 on the Independence Day Celebra-

tion Committee. | |

Primarily because of federal funding and prod-

ding, the city's advisory group for the mass transit -

technical group has three blacks and five whites.

‘Mobile was originally founded on the west bank

of the Mobile River. The land elevation for most of the

business and residential area until World War II was

from zero to ten feet. There has been a substantial

western expansion from the Mobile River and Bay which

lies to the east. Elevation in most of these areas

ranges from 40 to 50 feet, but in some of the areas

it

—-

it reaches as much as 160 feet. =

There are three principal watersheds in the

Mobile area. . ‘ uz, Three Mile Creek, traverses the

nortiers one-third of the city draining west to east.

The southern one-third of the city is drained by Dog

River running from west to east. The vemaining one-

third, which consists of old downtown and residential

Mobile, drains oRel to the Mobile River. Mobile has

an annual rainfall of 60 or more inches per year. It

is subject to torrential downpours. All areas of Mobile,

white and black, are traversed by open drainage ditches:

All areas, white and black, are subject to standing water

after torrential dowiponts with water in parts of all

areas reaching the depth of one to two feet.

-17-

a. = NT I LE rar T————" utp mF cnn wn . rp ee ne 1 = em . mE —— — OT wy] ee gn A a A 81 rt 0 3 OA a am a . — r—— - ; a ae” : I i gr :

SEN El

Mobile has a master drainage plan to be im-

plemented over a long period of time. Unfortunately,

most of the black residential areas are drained by the

Three Mile Creek. The drainage system for Three Mile

Creek involves issuing bonds and financing by the

city which involves millions of dollars projected over

several years. There has not been overt gross discrim-

ination against the blacks in connection with the drain-

age project. Forever, almost all temporary relief in

critical areas has been in the white areas. Somehow

the white areas get relief with little temporary relief

given the black areas. |

The resurfacing and witiensnes of streets in

black neighborhoods significantly suffers in comparison

‘with the resurfacing of steets in white aetehborhoods.

The testimony and an in-person visit of these areas

by the court sustains this conclusion.

| The g.8 Treasury Department, after a complaint

filed by the NAACP, found racial discrimination in the

city's resurfacing program. The city was advised by

letter this would have to be corrected in order for the

city to comply with the anti-discrimination provision

of the Revenue Sharing Act. (Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 111).

The construction of ~:~ first class roads, curbs,

sutters, and underground storm sewers are closely re- -

lated to the drainage system. If this type of construc-

tion is done in areas subject to repeated flooding, it

is a waste of money. The court observed that on the

-18-

southside of Three Mile Creek near the Crichton area,

which was formerly white - now mixed or predominantly

black, in the areas near the creek and subject to

flooding, the streets were paved with curb and

gutters while on the northside, near the black Trinity

Gardens area, only two streets have low-cost paving

with curbs, gutters, and underground drainage. Most

of the streets are unpaved. To put in first class

paving in that black area would be unwise financially,

but there is a significant difference and sluggishness

in the response of the city to critical needs of the

blacks compared to that in the white area.

There is the same difference and sluggishness

between whites and blacks in making provisional or

temporary mitigating improvements: pending development

of the master drainage plan throughout the city.

The Williamson School, in a predominantly black

area, is in a densely populated residential and neigh-

borhood business area. The houses are on lots large

enchzh and far enough from the streets that the placing

of sidewalks could be done without great difficulty. |

Children from low income’ families frequently walk or"

ride bicycles to and from school. Sidewalks are

critical in such areas. There was a noticeable lack or

of sidewalks in and near the Williamson School. |

The lack of sidewalks in the Plateau area presents

a different problem. The streets ave narrow and the lots

are small. The houses are built very close to the streets.

~-]19-

The personal inspection by the court revealed the

obvious difficulty in placing sidewalks in that area.

Blacks in Mobile, and their neighborhoods,

endure a greater share of infant deaths, major crimes,

T.B. deaths, welfare cases, and juvenile delinquency

than do whites in their neighborhoods. In The Neighbor-

hoods of Mobile: Their Physical Characteristics and

Needed Improvements (1969), the Mobile City Planning

Commission in Table Q of the Appendix, rates the 78

nelghiorhoods according to social blight. Nine of the

14 most blighted neighborhoods were predominantly black.

‘The causes of this blight are-multiple and it would be

inaccurate to suggest that a single member district plan

or the election of all black officials would correct fghein

them. Some of the causes, as the study in Table A

Sort

.

indicates, include inadequate drainage, water, streets,

IE sidewalks, and zoning. The city has a Yarge responsi-

bility in these areas. Although the city has not been

totally neglectful, and the expense and problems are

ponitnental , there is a singular sluggishness and low

priority in meeting these particularized black neighbor-

hood needs when compared with a higher priority of

temporary allocation of resources when the white community

is involved. | |

The Park and Recreation Program has generally been

administered in an evenhanded fashion, but i city pro-

jected park development program in the western part of

the city over a period of years involving large sums

of money indicates an expansion in predominantly white

-

-20-

.

areas without a simultaneous consideration of the

black area needs.

The black community has long complained of police

brutality. A number of investigations have been made

by the FBI but no indictments or evidence has" been

uncovered to substantiate serious charges of this

nature. On March 28, 1976, a black was arrested near

the scene of an alleged burglary. On April 8, an

attorney for the law firm of the plaintiffs' attorney

in this case reported to the Police Commissioner that

‘there had been an alleged attempted or mock” lynching

of the black person arrested.” On April 9, a meeting

was held between the commission, the black non-partisan

voters league, the district attorney's office, the

chief of police, and others concerning this instance.

The blacks claimed the charges were so serious

that the arresting officer should be suspended imme-

diately. It is claimed by the plaintiffs that this

officer at that time had pending against him a case of

alleged police brutality. The City Attorney immediately

obtained some statements of the alleged "mock" lynching

indicating there was substance in the charges. On

April 13, that officer was discharged and seven others

were suspended. Five indictments were returned in con-

‘nection with the alleged "mock" lynching. The court

does not deem it appropriate to make further comments

concerning the details. Suffice it to say, there was

a timid and slow reaction by the city commission to the

-21-

alleged "mock" lynching.

The Police Department then instituted an investiga-

tion on the older pending charges. As a result of the

investigation, two officers were discharged and six were

suspended, all in connection with charges of police

brutality but concerning unrelated incidents occurring

prior to the alleged "mock! lynching. :

Shortly thereafter there were twenty to thirty

alleged cross burnings in Mobile and adjoining Baldwin

County. Two of these were reported to have been in the

City of Mobile. The lack of reassurance by the city

commission to the black citizens and to the concerned

white citizens about the alleged "mock" lynching and

Cross birnings indicates the pervasiveness of the fear

of white backlash at the polls and evidences a failure

by elected officials to take positive, vigorous, affirma-

tive action in matters which are of such vital concern

to the black people. The sad history of lynch mobs,

racial discrimination and violence attributed to cross-

burners or fellow-travelers, justifiably raises specters

and fears of legal and social injustice in the minds |

and hearts of black people. White people Who are com-

mitted to the American ideal of equal. justice under the

law are also apprehensive. This sluggish and timid

response is anbther manifestation of the \odieniority ;

given to the needs of the black citizens and of the

political fear of a white backlash vote when black citi-

zens needs are at stake.

-22-

THERE IS NO TENUOUS STATE POLICY SHOW-

ING A PREFERENCE FOR AT-LARGE DISTRICTS.

There is no clear cut State policy either for

or against multi-member districting or at-large elec-

tions in the State of Alabama, considered as a whole.

The lack of State policy therefore must be considered

as a neutral factor. |

In considering the State policy with specific

reference to Mobile, the court finds that the city

commission form of government was passed in 1911.

That law provided for the election of the city commis-

sioners at-large. This feature has not been changed

although there have been some amendments to designate

duties for the commissioners as well as to designate

numbered places. Beginning in 1819, the year Alabama

became a state in the Union, until 1911, the great :

wajority of the time the city operated under a mayor-

alderman form of government. The election for the

mayor and aldermen was either b=lares or from multi-

member districts or wards. The manifest policy of the

City of Mobile has been to have at-large or multi-

member districting.

‘PAST RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

Prior to the Voting Rights Act: of 1965, there

was effective discrimination which precluded effective

participation of blacks in the elective system in the

State, including Mobile. |

| One of the primary Purposes of the 1901 Constitu-

tional Convention of the State of Alabama was to disen-

-23-

franchise the blacks. The Convention was singularly

successful in this objective. The history of discrim-

ination against blacks' participation, such as the

cunulative poll tax, the restrictions and impediments

to blacks registering to vote, is well established.

Local discrimination in the city and the county

has already been noted in connection with the lawsuits

concerning racial discrimination arising in this court,

to wit, the Allen, Anderson, Sawyer, Evans, and Cooke,

supra, cases. Preston v. Mandeville, 479 F.2d 127

(5th Cir. 1973) was a countywide case involving racial

r

discrimination of Mobile's jury selection practices.

Smith v. “Allwright, 321.1. S. 649, 64 8S. Ct. 157, 88 1. Ed.2d

987, (1944) (white privaties) was applicable to Alabama

and some Alabama cases of discrimination are Davis vz:

Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S/D Ala. 1949), aff'd. 336 U.S.

033, 69 S. Ct. 749, 93 L.Ed. 1093 (1048), {“interpretation”

tests for voter registration), Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 U. S. 339, 81 S. Ct. 125, 5 L.Ed.2d 110 (1960)

(racial gerrymandering of local government), Reynolds Y.

Sims, 377 U. 8S. 533, 84 S. Ct. 1362, 12 L.Ed.2d 506 (1964)

(racial gerrymandering of state government), and U. S S. v.

Alabama, 252 F. Supp. 95 (M/D Ala. 1966) (Alabama poll

tax).

The racial polarization existing in the city

elections has been discussed herein. The court finds

‘that the existence of past discrimination has helped

preclude the effective participation of blacks in the

election system today in the at-large system of electing

city commissioners.

-24-

— ee —— gt rm tp pr, A pegs cpg S| © tg ema on A | Sm tn | SS Si + cm a ga 2 ne

In the 1950's and early sixties, prior to the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, only a relatively small

percentage of the blacks were registered to vote in

8

the county and atty. ¥ Since the 1965 Voting Rights

8/ In the 1950's or 1960's the impediments placed

in the registration of blacks to vote was not

as aggravated in Mobile County as in some counties.

It was not necessary for voter registrars to be

sent to Mobile to enable blacks to register.

Act, the blacks have been able to register to vote

and become candidates.

ENHANCING FACTORS

With reference to the enhancing factors, the

court finds as follows: 3

(1) The citywide election encompasses a large

district. Mobile has an area of 142 square miles with

a population of 190,026 in 1970.

(2) The city has a vadoriiy vote requirement.

Alabama Acts 281 (1911) at 343, requires election of

commissioners by a majority vote.

(3) There is no anti-single shot voting pro-

vision but the candidates run for positions by place

9

or number.—

9/ The influence of this enhancing factor is minimal.

Voters could scarcely make an intelligent choice

for the best person to serve as a commissioner to

perform specific duties, such as Department of

Finance, without a numbered or place system. It is

this writer's opinion, born out of 15 years experi-

ence in a State judicial office subject to the elec-

-

-25-

% % %

toral process, that the public's best interest

‘is served, and it can make more intelligent

choices, when candidates run for numbered posi-

tions. The choices between candidates are

narrowed for the voter and they can be compared

head to head.

(4) There is a lack of provision for the at-

large candidates to run from a particular geographical

sub-district, as well as a lack of residence reanivonent.

The court concludes that in the aggregate, the

at-large election structure as it operates in the City

of Mobile substantially dilutes the black vote in the

City of Mobile. |

r

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

I.

There is a. threshold question faced by this

court in whether or not Washington v. Davis, B.S.

(1976)

, 96 S. Ct. 2040, 48 L.Ed.2d 597,/is dispositive

of this case so as to preclude an application of the

factors determinative of voter dilution as set forth

in White, supra, and Zimmer, supra, aff'd. sub nom.

East Carroll Parish School Board, supra.

It is the defendants’ contention that Washington

makes it clear that to prevail the plaintiffs must prove

that the city commission form of government was adopted

for Mobile in 1911 with a discriminatory purpose. They

-26-

It is argued that Washington is a benchmark decision requiring this finding in the multi-

by the District of Columbia Police Department. 71t had been alleged the test “excluded 2 disportionately high number of Negro applicants." Id. at 2044. The peti- tioners claimed the effect of this disportionate ex- clusion violated their Fifth Amendment dye process

rights and 42 y.s.c. $1981. 1d. at 2044. Evidence

indicated that four times as many blacks failed to pass the test as whites, Plaintiffs contended the impact

-27 —

in and of itself was sufficient to justify relief.

They made no claim of an tntent to discriminate. The

District Court found no intentional conduct and refused

relief. The Circuit Court reversed, relying upon

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U. S. 424, 91 S. Ct. 849,

28 L.Ed.2d 158 (1971). Griggs was a Title VII action

(42 U.S.C. §2000e, et seq.) in which the racially dis-

criminatory impact of employment tests resulted in

their invalidation by the court.

The Supreme Court in Washington reconciled

its decision with several previous holdings, distinguished

some, and expressly overruled some cases in which there

were possible conclusions different from Washington.

They made no reference to the recent pre-Washington

cases of its or appellate courts'#voting dilution deci-

sions dealing with stators or multi-member versus

single member districts, and, in particular, no mention

was made of the cardinal case in this area, White v.

Regester, 412 U. S. 755, 93 S. Ct. 2342, 37 L.Ed.2d 314,

(1973), nor fo Dnllas v. Reese, 421 U. 8S. 477, 95 8. Ct.

1706, 44 L.Ed.2d 312, (1975), and Chapman v. Meier,

420 U. S. 1, 95 S. Ct. 751, 42 L.Ed.2d 766 (1975),

nor to Zimmer, which the Court had affirmed only a

few months before, nor to Turner v. McKeithen, 490 F.2d

191 (5th Cir. 1975). No reference was made to Fortson

v. Dorsey, 379 U. S. 433, 85 S. Ct. 498, 13 L.Ed.2d

401 (1965), to Reynolds, nor to Whitcomb. Whitcomb,

-928-

403 U. S. at 143, recognized that in an at-large

election scheme, a showing that if in a particular case

the system operates to minimize or cancel out the voting

strength of racial or political elements, the courts

can alter the structure. Had the Supreme Court: intended

the Washington case to have the far reaching consequences

contended by defendants, it seems to this court reason-

able to conclude that they would have made such an

expression.

There are several reasons which may be plausi-

ny advanced as to why the Washington Court did not

expressly overrule nor discuss these cases. Courts

are not prone to attempt to decide every eventuality

of a case being decided or its effect on all previous

ji cases. The Court may have desiréd that there be further

development of the case law in the district and circuit

courts before commenting on the application of Washing-

ton to this line of cases. The cases may be disting-

uishable and reconcilable with the expressions in

Washington. Or, it may not have been the intention of

the Washington Court to include these cases within the

ambit of its ruling.

Washington spoke with approval of Wright v.

Rockefeller, 378 U. S. 52, 84 8. Ct. 603,- 11 1..BEd.24 512

(1964), setting out the "intent to gerrymander™ require-

ment established in Wright. Washington, at 2047-48.

Wright was the direct descendant of Gomillion Vv.

lichtfoot, 364 U. 8. 339,821 8, Ct. 125, 5 L.Ed.2¢ 110

-29-

(1960). These two cases involved racial gerrymandering

of political lines. Gomillion dealt with an attempt by

the Alabama legislature to exclude most black voters

from the municipal limits of Tuskegee so whites could

control the elections. The court found that the State

of Alabama impaired the voting rights of black citizens

while cloaking it in the garb of the realignment of

political subdivisions and held there was a violation

of the Fifteenth Amendment. Gomillion, at 345. There

was no direct proof of racial discriminatory intent.

Justice Stevens in his concurring opinion noted with

approval, ". . . when the disproportionate impact] .

is as dramatic as in Gomillion, . . , it really does not

matter whether the standard is phrased in terms of

" 10/ |

purpose or effect. Washington, at: 2054.7 (emphasis~added).

10/ In Paige v. Gray, 538 7,24 1108 (5th Cir. 1976),

black citizens of Albany, Georgia, brought an

action to invalidate the at-large system of elect-

ing city commissioners. At 1110, n. 3, the court

noted the above quote by Justice Stevens, but in the

body of the opinion expressed concern with unlawful

motive for discriminatory purpose as required by

Washington. However, at 1110, the court stated

“the validity of Albany's change from a ward to

an at-large system can best be handled by applying

the multifactor test enunciated in . . . Vhif{e v.

Regester . . . and Zimmer v. McKeithen." Paige,

at 1110, stated Zimmer st. still Sots the basic

standard in. this circuit.

Wright dealt with the issue.of congressional re-

districting of Manhattan. The plaintiffs alleged racially

motivated districting. The congressional lines drawn

created four districts. One had a large majority of

-30-

blacks and Puerto Ricans. The other three had large

shite majorities. The court held the districts were

not unconstitutionally gerrymandered upon the finding

that ". . . the New York legislature was [not] motivated

by racial considerations or in fact drew the districts

on racial lines.” Wright, 376 U. S. at 56. This sol

forth the principle that in gerrymandering cases in order

for the plaintiffs to obtain relief they must show racial

motivation in the drawing of the district lines.

Washington then quoted with approval from Keyes v.

School District No. I, 413 U. S. 189, 93 S. Ct. 2686,

37 L.Ed.2d 548 (1973), indicating a distinction or

reconciliation of that case with Washington. There had

not been racial purpose or motivation ab initio in Keyes.

Keyes was a Denver, Colorado, school desegregation case.

Denver schools had never been segregated by force of

state statute or city ordinance. Nevertheless, the

majority found that the actions of the School Board

144 during the 1960's were sufficiently indicative of ". . .

[a] purpose or intent to segregate” and a finding of

de jure segregation was sustained. Keyes, at 205, 208.

That court held that to find overt racial considerations

in the actions of government officials is indeed a

| 11/

difficult task.m™™

11/ In another Fifth Circuit case it was held that if ..

an official is motivated by such wrongful intent,

he or she

". . . will pursue his discriminatory

practices in ways that are devious,

by methods subtle and elusive. - for we

-31-

deal with an area in which 'subtleties

of conduct. . . play no small part.'"

U. 8S. v. Texas Bd. Azency, 532 7.24

330, 388, (5th Cir. 1976) {Austin II)

(school desegregation).

Washington further commented:

14

« « an invidious discriminatory

purpose may often be inferred from

the totality of the relevant facts,

including the fact, if it is true,

that the law bears more heavily on

one race than another." Washington,

96 8S. Ct. at 2040,

The plaintiffs contend that Washington's discus-

sion with approval of the Keyes case permits the appli-

cation of the "tort" standard in proving intent. In

his concurring opinion, Justice Stevens discussed this

point: 3

"Frequently the most probative evidence

of intent will be objective evidence ”

of what actually happened rather than

evidence describing the subjective

state of mind of the actor. For nor-

.mally the actor is presumed to have

intended the natural consequences of

his deeds. This 1s particularly true

in the case of governmental action

which is frequently the product of

compromise, of collective decision-

making, and of mixed motivation.”

Washington, 96 S. Ct. at 2054

(emphasis added).

The plaintiffs contend this circuit's use of

the tort standard of proving intent squares with the

above statements. This circuit for several years has

accepted and approved the tort standard as proof of

segregatory intent as a part of state action in school

desegregation findings. Morales v. Shannon, 516 F.2d

411, 412-13 (8th Cir. 1975), cert. den. 423 U.S. 1034

(1975).

-32-

Recently, citing Morales, supra, Cisneros v.

Corpus Christi Independent School District, 467 F.2d

142 (5th Civ. 1972) {en banc), cert. den. 413 U. 8S.

920 (1973), reh. den. 413 U. S. 922 (1973), and United

States v. Texas Educational Agency, 467 F.2d 848

(5th Cir. 1972) (en banc) (Austin I), the Fifth

Circuit in U. S. v. Texas Education Agency, (Austin

Independent School District) 532 F.2d 380 (5th Cir.

1976) (Austin II) squarely addressed the meaning of

discriminatory intent in the following language:

"Whatever may have been the origi-

nally intended meaning of the test

we applied in Cisneros and Austin I .

[U.S. v. Texas Education Agency,

. supra, ], we agree with the intervenors

that, after Keyes, our two opinions

must be viewed as incorporating in

school segregation law the ordinary

rule of tort law that 2 person in-

tends the natural and foreseeable

consequences of his aoiions.

kk * xk

Habart from the need to conform

Cisneros and Austin I to the super-

vening Keyes case, there are other

reasons for attributing responsibility

to a state official who should rea-

sonably foresee the segregative ef-

"fects of his actions. First, it is

difficult - and often futile - to obtain

direct evidence of the official's in-

tentions. . . . Hence, courts usually

rely on circumstantial evidence to

ascertain the decisionmakers' motiva-

tions." Id. at 388.

This court in its findings of fact has held that

when the 1911 statute was enacted, at a time the Nd

were disenfranchised, the statute on its face was

neutral. This is in line with Fifth Ciroult opin-

ions, McGill v. Gadsden Co. Commission, 535 F.2d, 277

-33-

(5th Cir. 1976), Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d at 633

(5th Cir. 1975), vacated 1.8. , 96 3. Ct. 1721,

48 L.Ed.2d 191 (1978). No. 74-2654 (5th Cir., Sept. 17,

1976), affirmed the District Court and Taylor v.

McKeithen, 499 F.2d 893, 896 (5th Cir. 1974). However,

in the larger context, the evidence is clear that one

of the primary purposes of the 1901 constitutional con-

vention was to disenfranchise the LY

12/ The history of Alabama indicates that there was a

populist movement at that time which sought to

align the blacks and the poor whites. The Bourbon

interests of the State sought to disenfranchise

the poor whites along with the blacks but were

unsuccessful, excepting the cumulative feature

of the poll tax. They were singularly success-

ful in disenfranchising the blacks.

Therefore, the legislature :in 1911 was acting ~

in a race-proof situation. There can be little doubt

as to what the legislature would have done to prevent

the blacks from effectively participating in the politi-

cal process had not the effects of the 1901 constitution

prevailed. The 1901 constitution and the subsequent

statutory schemes and practices throughout Alabama,

until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, effectively dis-

enfranchised most blacks.

A legislature in 1911, less than 50 years after a

- bitter and bloody civil war which resulted in the

emancipation of the black slaves, should have reason-

ably expected that the blacks would not stay disenfran-

chised. It is reasonable to hold that the present di-

lution of black Mobilians is a natural and foreseeable

-34-

consequence of the at-large election system imposed in

1911.

Under Alabama law, the legislature is responsi-

ble for passing acts modifying the form of city and

county governments. Mobile County elects or has an

effective electoral voice in the election of eleven

members of the House and three senators. The state

legislature observes a courtesy rule, that is, if

~ the county delegation unanimously endorses local

legislation the legislature perfunctorily approves all

local county legislation. The. Mobile County Senate

delesation of three members operates under a courtesy

rule that any one member can veto any local legisla-

tion. If the Senate delegation unanimously approves

-—

the legislation, it will be perfunctorily passed in

the State Senate. The county House delegation does

not operate on an unanimous rule as in the Senate, but

on a majority vote principle, that is, if the majority

of the House delegation favors local legislation, it

will be placed on the House calendar but will be sub-

ject to debate. However, the proposed county legislation

will be perfunctorily approved if the Mobile County House

delegation unanimously approves it. The evidence is il

clear that whenever a redistricting bill of any type

is proposed by a county delegation member, a major con-

cern has centered around how many, if any, blacks would

-35-

; % pe | »

be elected. These factors prevented any effective

redistricting which would result in any benefit to the

black voters passing until the State was redistricted

13

by a federal court order As There are now three blacks

13/ Sims v. Amos, 336 F. Supp. 924 (M/D Ala. 1972).

: House

on the eleven member /legislative delegation. This re-

sulted in passage in the 1975 legislature of a bill

doing away with the A t=Tatne election of the County

Board of School Commissioners and creating five single

member districts. This was promptly attacked by the

all=white ot=large elected County School Board Com-

mission in the State court. ‘The act was declared un-

constitutional for failure to have met statutory re-_

ahivements concerning advertisement. | :

This natural and foreseeable consequence of the

1911 Act, lack voter dilution, was brought to fruition

ih 50. odd yesrs, the middle 1040's, asd continues to

the present. This court sees no reason to distinguish

a school desegregation case from a voter discrimination

case. It appears to this court that the evidence sup-

ports the tort standard as advocated by the plaintiffs.

However, this court prefers not to base its decision on

this theory. A This court deems it desirable to determine

if the far-reaching consequence of Washington as ad- =

vanced by the defendants is correct without regard to

. Keyes. This court is unable to accept such a broad hold-

ing with such far-reaching consequences.

-36-

: $ % (

The case sub judice.can be reconciled with

Washington. The Washington Court, in Justice White's

majority opinion, included the following:

"This is not to say that the

necessary discriminatory racial

purpose must be express or ap-

pear on the face of the statute,

or that a law's disportionate im-

pact is irrelevant in cases in-

volving Constitution-based claims

of racial discrimination. A

statute, otherwise neutral on its

face, must not be applied so as

invidiously to discriminate on

the basis of race. Yick Wo v.

Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886).

Washington, 96 S. Ct. at 2048.

To hold that the 1911 facially’ neutral statute would

defeat rectifying the invidious discrimination on the

basis of race which the evidence has shown in this

case would fly in the face of this principle. . 2

-

it is not a long step from the systematic ex-

clusion of blacks from juries which is itself such an

"unequal application of the law. . . as to show

intentional discrimination,” Atkins v. Texas, 325 U. S.

398, 404,65 S. Ct. 1276, 89 L.Ed. 1692 (1945) and the

deliberate Systenatin denials to people from juries

because of their race, Carter v. Jury Commission,

Cassell v. Texas, Patton v. Mississippi, cited in

Washington, at 2047, to a present purpose to dilute

the black vote as evidenced in this case. There is

a "current" condition of dilution of the black vote

resulting from intentional state legislative inaction

which is as effective as the intentional state action

-37-

referred to in Keyes. Washington, at 2048.

More basic and fundamental than any of the

above approaches is the factual context of Washington

and this case. Initial discriminatory purpose in

employment and in redistricting is entirely different

from resulting voter dilution because of racial dis-

crimination. Washington's failure to expressly overrule

or comment on White, Dallas, Chapman, Zimmer, Turner,

Fortson, Reynolds, or Whitcomb, leads this court to

the conclusion that Washington did not overrule those

cases nor did it establish a new Supreme Court purpose

test and require initial discriminatory purpose where

voter dilution occurs because of racial discrimination.

18 ; i

-

--

In order for this court £0 grant relief as

prayed for by plaintiffs, it must be shown that the

political process was not open equally to the plain-

tiffs as a result of dilution of voting strength and

consequently the members of the class had less op-

portunity to participate in the political process

and elect representatives of their choice. Chapman,

420 U. S. at 18, and Whitcomb. "Access to the

political process and not [the size of the minority]

population” is the key determinant in ascertaining

whether there has been invidious discrimination so

as to afford relief. White, 412 U. S. at 766;

Zimmer, 485 F.2d at 1303.

3H

| The idea of a democratic society has since

the establishment of this country been only a sup-

position to many citizens. The Supreme Court vocalized

this realization in Reynolds where it formulated the

"one person-one vote" goal for political elections.

The precepts set forth in Reynolds are the sub-

structure for the present voter dilution cases, stating

that "every citizen has an inalienable right to full

and effective participation in the political processes

.e vais) Boynolds, 377 U. S. at 585. The Judiciary

in subsequent cases has recognized that this principle

18 violated when a particular identifiable racial

‘group is not able to fully and effectively participate

in the political process because of the system's

structure. - i | as

~ Denial of full voting rights vaie from out-

rig refusal to allow registration, Smith, to racial

gerrymandering so as to exclude persons from voting

in a particular jurisdiction, Gomillion, to establish-

ing or maintaining a political system that grants

citizens all procedural rights while neutralizing

their political strength, White. The last arrange-

ment is maintained by the City of Mobile.

Essentially, dilution cases revolve around the

"quality" of representation, Whitcomb, 403 U. S. at 142.

The touchstone for a showing of unconstitutional racial

voter dilution is the test enunciated by the Supreme Court

-39-

in White, 412 U. S. at 765: "Whether multi-member

districts are being used invidiously to cancel out

or minimize the voting strength of racial groups.”

In White, for slightly different reasons in each

county, the Supreme Court found that the multi-member

districts in Dallas and Bexar Counties, Texas, were

minimizing black and Mexican-American voting strength.

Attentive consideration of the evidence pre-

sented at the trial leads this court to conclude that

the present commission form of government in the City

of Mobile impermissibly violates the constitutional

Fights of the plaintiffs by improperly restricting

their access to the political process. White, 412

U. S. at 766; Whitcomb, 403 U. S. at 143. The plain-

tiffs have discharged the burden of proof as required

by Whitcomb.

This court reaches its conclusion by collating

the evidence produced and the law propounded by the

federal appellate courts. The controlling law of this

Circuit was enunciated by Judge Gewin in Zimmer, which

; 14/

closely parallels Whitcomb and White.” The Zimmer

14/ See also Paige v. Gray, 538 F.2d 1108 (5th Cir. 1976).

court, in an en banc hearing, set forth four primary

and several "enhancing' factors to be considered when

resolving whether there has been Supernissible voler

dilution. The primary factors are:

1"

vie leh lack of access to the process

-40-

of slating candidates, the unre-

sponsiveness of legislators to

their particularized interests,

a tenuous state policy underlying

the preference for multi-member or

at-large districting, or that the

existence of past discrimination in

general precludes the effective

participation in the election system,

a strong case [for relief] is made.”

Zimmer at 1305. . [footnotes omitted].

The enhancing factors include:

"a showing of the existence of large

~ districts majority vote requirements,

anti-single shot voting provisions

and the lack of provision for at-large

candidates running from particular

geographical subdistricts.” Zimmer

at 1305. [footnotes omitted].

1. LACK OF OPENNESS IN THE SLATING PROCESS

OR CANDIDATE SELECTION PROCESS TO BLACKS.

I BIUSE, the political parties in the City of

or i] Mobile do not slate candidates per se; rather, any 2

person interested in running for the position of city

commissioner is able to do so. There has been little

evidence to a "party" SENET Ling one candidate or

another in the city races. | :

~The system at first blush appears to be neutral,

‘but consideration of facts beneath the surface demonstrate

the effects which lead the court to conclude otherwise.

No black has ever been elected city commissioner in

Mobile. The evidence indicates that black politicians

who have previously been candidates in at-large elections

and would run again in the smaller single member districts,

shy away from city at-large elections. One of the prin-

cipal reasons is the polarization of the white and black

vote. The court is concerned with the effect of lack of

-41-

of openness in the electoral system in determining

whether the multi-member at-large election system of

the city connissioners is invidiously discriminatory.

In White, the Supreme Court expressed concern

with any type of barrier to effective participation

in the political process. Zimmer, 485 F.2d at 1305

n.20, expressed its view in this language: "The standards

we enunciate today are applicable whether it is a

specific law or custom or practice which causes dimi-

nution of a minority Voting strength.”

There is a lack of openness to blacks in the

political process in city elections.

2. UNRESPONSIVENESS OF THE ELECTED CITY

OFFICIALS TO THE BLACK MINORITY,

© It is the conclusion of the court that the city-

wine electedimmitinei commission form of government

as practiced in the City of Mobile has not aud is

not responsive to blacks on an equal basis with whites;

hence there exists racial discrimination. Past admin-

istrations aot only acauicsed to segregated folkways,

but actively enforced it by the passage of numerous

city ordinances. There have been orders from tite court

to desegregate the police department, the golf course,

public transportation, tue nirport; wid which attack

: 515

racial discrimination in employment.

15/ The County School Board, which operates both in the

city and county, has been in federal court continu-

ously since 1963 to effect meaningful desegregation.

- Davis v. Mobile County School Board, Civil Action

No. 3003-63 (S/D Ala. 1963). Incidentally, during

-

-492-

the course of the court's continuing jurisdiction

in Davis, there have been fifteen or more appeals

to The Fifth Circuit.

There has been a lack of responsiveness in em-

ployment and the use of public facilities. It is this

court's opinion that leadership should be furnished in

non-discriminatory hiring and promotion by our govern-

16/

ment, be it local, state, or federal.

16/ Norman R. McLaughlin, etc. v. Howard H. Callaway,

er al., Civili Action Xo. 74- -123-P, S/D Ala.,

9/30/74, at p. 22:

"It is only fitting that the govern-

ment take the lead in thelnttle

against discrimination by ferreting

, out and bringing an end to racial

" discrimination in its own ranks.”

Mobile has no ordinances proclaiming equal employ-

ment opportunity, either public or private, to be

its policy. There are no non- discriminatory rental

. ordinances. On the one hand, the federal courts

: are often subjected to arguments by recalcitrant

state and local officials of the encroachment of

the federal bureaucracy and assert Tenth Amendment

violations - while making no mention that were it

not for such "encroachment citizens would not have

made the progress they have to fulfillment of equal

rights. Recent history bears witness to this propo-

sition. :

Tn addition to the refisgil of officials to vol-

untarily desegregate facilities, the city commissioners

have failed to appoint blacks to municipal committees in

numbers even approaching fair veuresbntiation. Appoint-

ments to city committees are important not only to ob- ;

tain diverse opinions from all parts of the community

and share fairly what over the committees have, but

for the black community it would open parts of the gov—

-43-

ernmental processes to those to whom they have for so

long been denied. The city commission's custom or

policy of appointing disproportionately few blacks to

committees is a clear reflection of the at-large elec-

tion -system's dilution of blacks' influence ‘and par-

ticipation. The commissioners appoint citizens from

their neighborhoods and constituencies, which are

virtually all white. The commissioners have relatively

less contact with the black community and hence are not

as likely to know of black citizens who are qualified

and interested in serving on committees. Recognizing

the admonitions of the courts when judicially dealing

with discretionary appointments, Mayor of the City of

Philadelphia v. Educational Taualily AT 415 U. S.

0d 8. Ct. 1323,

605, /39 L.Ed.2d 630 (1974), and James v. Wallace,

ee

933 F.2d 963 (5th Cir. 1978), that it is not within

the authority of this court to order particular ap-

pointments, it is this court's view that the failure

to appoint a significant number of blacks is indicative

of a lack of responsiveness. |

3. NO TENUOUS STATE POLICY SHOWING A

PREFERENCE FOR AT-LARGE DISTRICTS.

The Alabama legislature has offered little

evidence of a preference one way or the other for

multi-member or at-large districts in cities the size

of" Mobile. For example, Title 7, §426, Code of Alabama

(1940 Supp. 1973), provides for a number of various

forms of either multi-member or single-member municipal

governments, with a municipality's option often dictated

-44-

by its size. Mobile, with a population exceeding

50,000 persons, is allowed by Alabars Code, Title 37,

§426, to have a mixture of single member and at-large

aldermen. Consequently, this court finds state policy

regarding multi-member at-large districting as neutral.

Mobile itself has had a mixed history concerning

its local preference for representative districting,

particularly prior to the adoption of the commission

government in 1911. Elections were usually at-large

but at times there were some ward residency requirements

and multi-member ward elections. Since 1911, however,

the cliy commission has been elected in citywide at-large

elections | |

4. PAST RACIAL DISCRIMINATION.

It is this court's opinion®that fair and effective

participation under the present electoral system 1s,

because of its structure, difficult for the black citizens

of Mobile. Past discriminatory customs and laws that :

were enacted for the sole and intentional purpose of

extinguishing or minimizing black political power is

responsible. The purposeful excesses of the past are

still in evidence today. Indeed, Judge Rives, writing

for a three-judge panel finding the Alabama poll tax to

be unconstitutional, stated forcefully:

"'The long history of the Negroes’

struggle to obtain the right to

vote in Alabama has been trumpeted

before the Federal Courts of this

State in great detail.*** If this

Court ignores the long history of

racial discrimination in Alabama,

it will prove that justice is both

-45-

blind and deaf.’ We would be

blind with indifference, not im-

partiality, and deaf with inten-

tional disregard of the cries for

equality of men before the law."

U. S. v. State of Alabama, 252

F. Supp. at 104 (M.D. Ala. 1966),

[citing Sims v. Baggett, 247 F.

Supp. 96, 108-09 (M.D. Ala. 1965)].

Without question, past discrimination:;,, some of

which continues to today as evidenced by the orders in

several lawsuits in this court against the city and

county, and demonstrated in the lack of access to the

selection process and the city's diresuonsiveness.

contributes to black voter dilution.

OS. ENHANCING FACTORS.

Zimmer, in addition to enumerating four substan-

tial criteria in proving voter dilution, listed four

"enhancing factors” that should b& considered as proof

of aggravated dilution.

a. Large Districts. The present at-large

election system is as large as possible, i.e., the city.

The city with an area of 142 square miles, and more

than 190,000 persons, can reasonably be divided into

election districts or wards. It is common knowledge

that numerous towns and cities of much less size in

Alabama are so divided and function reasonably well.

It is large enough to be considered large within the

meaning of this factor.

b. Majority Vote Requirements. Alabama Acts

No. 281 (1911) at 343, which established the Mobile com-

mission form of government, required the election of the

representatives by a majority vote.

-46-

c. Anti-single Shot Voting: There is in

Act No. 281 "no anti-single shot" voting provisions nor

is there one in the current codification, [Ala. Code,

Title 37, §89, et seq.,] or in Alabama Acts No. 823 (1965)

17

at 1539. L7/

17/ An "anti-single shot" provision obtained in all city

elections from 1951 to 1961, see Ala. Code, Title 37,

§33(1),but was repealed 9/15/61. :

The numbered place provision of Act 823 (or, if

Act 823 is invalid, Ala.Code, Title 37, §94) has to some

extent the same result. At least in part, the practical

result of an anti-single shot provision obtains in Mobile. ™

18/ See footnote 9, supra.

d. lack of Residency Requirement. Act 281

does not contain any provision requiring that any com-

19/

missioners reside in any portion of town. 2

19/ To impose residency requirements under Act 823, the

designation of duty provision, (or if Act 823 is in-

valid, Ala. Code, Title 37, §94, the numbered position

provision), as well as the 1911 establishment of at-

large election of city commissioners would at a minimum

be anomalous and probably unconstitutional. City com-

missioners in command of particular functions, such as

public safety, residing and being elected from one

particular side of town, would be accountable to only

one-third of the population notwithstanding jurisdic-

tion over the entire city. B.U.L.L. v. City of

Shreveport, F. Supp. , No. 74-272 (W.D. 1a.

July 16, 1978. ), also expresses this view.

111.

The court has made a finding for each of the

Zimmer factors, and most of them have been found in Suver

of the plaintiffs. The court has analyzed each factor

separately, but has not counted the number present or

absent in a ''score-keeping" fashion. -

-47-

ERNE : TTY : NE - [YS

Same 4 . htt 5 SN RYE.

3, a nhilin f J RATA ET, ia

The court has made a thoughtful, exhaustive

analysis of the evidence in the record ". . . paying

close attention to the facts of the particular situations

at hand," Wallace, 515 F.2d at 631, to determine whether

the minority has suffered an unconstitutional dilution of

the vote. This court's task is not to tally the presence

or absence of the particular factors, but rather, its

opinion represents ". . . a blend of history and an

intensely local appraisal of the design and impact of

the wit l-menber distr int [under scrutiny] in light of

past and present reality, political and otherwise.”

‘White, 412 U.S. at 769-70. Lg

The court reaches its conclusion by following

the teachings of White, Dallas v. Reese, 421 U. S. 477,

480, 95 S. Ct. 1706, 44 L.Ed.2d 312 (1975), Zimmer,

Fortson, and Whitcomb, et al.

The evidence when considered under these teachings

convinces this court that the at-large districts "operate

to minimize or cancel out the voting strength of racial

or political elements of the voting population.’

Whitcomb, 403 U. S. at 143, and Fortson, 379 U. 8S. at 438,

and "operates impermissibly to dilute the voting strength

of an identifiable element of the voting population,”. =

Dallas, at 480. The plaintiffs have met the burden cast

in White and Whitcomb by showing an aggregate of the

factors cataloged in Zimmer.

In SIE, this court finds that the electoral

structure, the multi-member at-large election of Mobile

City Commissioners, results in an unconstitutional dilution

of black voting strength. It is "fundamentally unfair”,

-48-