In Re: Campaign of Senator Bilbo Brief Submitted by the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. In Re: Campaign of Senator Bilbo Brief Submitted by the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, 1964. 4a31f3db-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a82a71c5-2b0c-4a31-b33c-e5366ae35b77/in-re-campaign-of-senator-bilbo-brief-submitted-by-the-mississippi-freedom-democratic-party. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

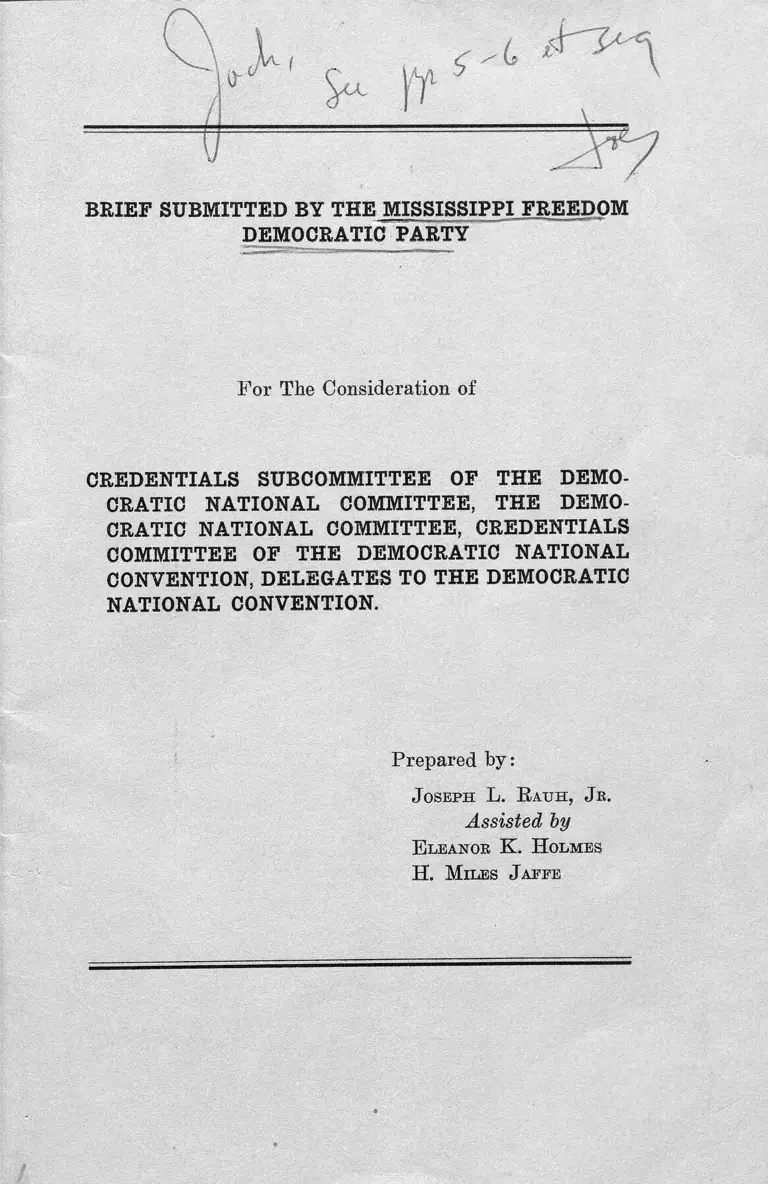

BRIEF SUBMITTED BY THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM

DEMOCRATIC PARTY

For The Consideration of

CREDENTIALS SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE DEMO

CRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE, THE DEMO

CRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE, CREDENTIALS

COMMITTEE OF THE DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL

CONVENTION, DELEGATES TO THE DEMOCRATIC

NATIONAL CONVENTION.

Prepared by:

Joseph L. Rauh , Jk.

Assisted by

E leanor K . H olmes

H. M iles Jappe

INDEX

INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF FA C TS.. ................................................... 5

I. W HY THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMO

CRATIC PARTY WAS FORM ED............................. 5

A. Negroes Have Traditionally Been Excluded From All

Participation in the Mississippi Democratic P a rty .. 5

(i) Party Runs State................................................... 5

(ii) Party Prevents Negro Registration.................... 6

(iii) Total Exclusion of Negroes......................... 11

(iv) Conclusion ................................................. 13

B. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party Desires

to Work Within the Framework of the National

Democratic Party........................................................... 14

II. ORGANIZATION AND OPERATION OF THE MIS

SISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PA R TY .......... 15

(i) Freedom Party Formed....................................... 15

(ii) Freedom Party Follows Law ............................... 15

(iii) Freedom Party Convention........ ................. . 18

(iv) Freedom Party Delegates Certified.................... 20

III. OPERATION OF THE MISSISSIPPI DEMOCRATIC

PARTY ................................................................................ 21

(i) “ Traditional” Party Asserts Independence. . . . . 21

(ii) “ Traditional” Party Opposes National Platform 22

(iii) “ Traditional” Party Attacks National Leaders 23

(iv) “ Traditional” Party Villifies Negroes................ 26

(v) “ Traditional” Party for Goldwater............... 31

(vi) Twenty Years of Political Perfidy...................... 32

(vii) “ Traditional” Party Leaders Duck Convention 33

(viii) Conclusion ............................................................. 34

Page

— 2216-0

11 INDEX

LEGAL ARGUMENTS FOR SEATING MISSISSIPPI

FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PA R TY ............................. 36

I. THE RULES OF THE CONVENTION FORBID

THE SEATING OF THE “ TRADITIONAL” MIS

SISSIPPI DEMOCRATIC PARTY DELEGATION.. 36

A. Paragraph (1) of the Rules Forbids the Seating of the

Delegation of the “ Traditional” Party Because That

Party Has Not and Can Not Give the Required As

surances Concerning the November Ballot................ 37

B. Paragraph (2) of the Rules of the Convention For

bids the Seating of the Delegation of the “ Tradi

tional” Party Because the Delegates Do Not Come

as “Bona Fide Democrats” Willing to “ Participate in

the Convention in Good Faith” ................................. 43

II. THE DELEGATION OF THE “ TRADITIONAL”

PARTY SHOULD NOT BE SEATED BECAUSE

THE STATE CONVENTION WHICH SELECTED

AND CERTIFIED IT WAS ILLEGAL AND UN

CONSTITUTIONAL ......................................................... 47

A. The Convention of the “ Traditional” Party Was

Illegal and Unconstitutional Because That Party

Runs the State of Mississippi and Uses Its Power to

Exclude Negroes From Registration and Participa

tion in the Political Processes of the State.............. 47

B. The “ Traditional” Party and Its Convention Are

Regulated in Detail By the State and Its Actions in

Excluding Negroes Are State Action in Violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment......................................... 50

Page

INDEX

HI. ANY FAIR COMPARISON OF THE TWO PARTIES

CAN, IN LAW AND IN EQUITY, LEAD ONLY TO

THE SEATING OF THE DELEGATION REPRE

SENTING THE FREEDOM PARTY .......................... 53

A. The Standard to Govern Convention Action Is Which

of the Two Groups Exhibits Good Faith to the Na

tional Party and Carries on Its Activities Openly and

Fairly .............................................................................. 56

B. The Freedom Party Delegation Must Be Seated

Under Any Standard Relating to Fairness and Good

Faith ............................................................................... 60

CONCLUSION ........................................................................... 62

APPENDIX A ................................................................. 63

APPENDIX B ........................................................................... 67

APPENDIX C ........................................................................... 72

T able of Cases

Bell v. Hill, 74 S.W. 2d 113, 123 Tex. 531 (1934).................. 48

Cain v. Page, 42 S.W. 336, 19 K.L.R. 977 (1897).................. 2

Davis v. Hambrick, 58 S.W. 779, 109 Ky. 276 (1900).......... 1

Davis v. State, 23 So. 2d 87, 156 Fla. 178 (1945).................. 47

Kearns v. Ilowley, 41 A. 273, 188 Pa. 116 (1898).................. 2

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 (1932)....................................... 47

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927)................................... 47

Phelps v. Piper, 67 N.W. 755, 48 Neb. 724 (1896).................. 1

Ray v. Blair, 343 U.S. 214 (1952)............................................. 37

Ray v. Gardner, 57 So. 2d 824, 257 Ala. 168 (1952).............. 58

Re Woodworth, 16 N.Y. Supp. 147 (1891)............................. 57

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944)........................47,48,49

Smith v. McQueen, 166 So. 788, 232 Ala. 90 (1936)...... 1

Spencer v. Maloney, 62 Pac. 850, 28 Colo. 38 ( 1900 ) . . . . . . . 57

State v. Hogan, 62 Pac. 583, 24 Mont. 383 (1900)......... 57,58

State v. Johnson, 46 Pac. 533, 18 Mont. 548 (1896)...... 58,59

State v. Rotwitt, 46 Pac. 370, 18 Mont. 502........... .............. 58,59

State v. Weston, 70 Pac. 519, 27 Mont. 185 (1902)................ 58

Page

IV INDEX

Stephenson v. Board of Election Commissioners, 76 N.W. 914,

118 Mich. 396 (1898)............................................................... 56

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953)....................................... 47,49

Tonis v. Board of Regents of XJ. of State of New York, 295

N.Y. 286, 67 N.E. 2d 245 (1946)......................................... 44

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299 (1941)........................ 47

Wood v. State, 169 Miss. 790, 142 So. 747 (1932)................. 1

M iscellaneous

Address by Judge Tom Brady to the Commonwealth Club of

; California at San Francisco, Oct. 4, 1957............................. 30

Annotation, 151 A.L.R. 1121..................................................... 52

Bfady, Tom P., Black Monday (1955) pp. 12, 73, 69............ 29,30

Cannon, Democratic Manual for the Democratic National

Convention of 1964, PP- 15, 35............................................. 5,37

18 Am. Jur., Elections, §§ 135, 136........................................... 2,57

18 U.S.C. 241, 242......................................................................... 53

Holtzman, The Loyalty Pledge Controversy in the Demo

cratic Party, 1960, p. 21........................................................... 44,45

Law Enforcement in Mississippi, a Special Report of the

' Southern Regional Council, July 14, 1964........................... 3,52

Life Magazine, February 7, 1964, p. 4 ..................................... 27

Mississippi Code...................................................................8,10, 50, 51

Mississippi Free Press, April 18, 1964, p. 1, 4 . ....................... 8

Mississippi—Subversion of the Right to Vote, Pamphlet of

1 the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Atlanta,

V-Georgia.............................................................................. 9

Official Proceedings of the Democratic National Convention,

1956, p. 822....................... 45

Platform and Principles of the Mississippi Freedom Demo

cratic Party............................................................................... 19, 63

Report on Mississippi, January, 1963, p. 23........................... 10

Report of the United States Commission mi Civil Rights,

0-1963, p. 2 0 . . . ..........i ............. ......................... ....................... 6

Page

INDEX V

Page

Resolution of the Democratic National Committee contained

in February 26, 1964 Call for the 1964 Democratic Na

tional Convention..................................................................... 2

Silver, James W., The Closed Society (1963), p. 60.............. 26,31

The Citizen, Official Journal of the Citizens’ Councils of

America, December, 1963, p. 10............................................. 29

The Johnson Journal, Vol. I l l , 1963, p. 1............................... 21

Time Magazine, August 16, 1963, p. 17................................... 23

BRIEF SUBMITTED BY

THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY

Introduction

The question whether to seat the delegation of the Mis

sissippi Freedom Democratic Party or the delegation of

the “ regular” or “ traditional” Mississippi Democratic

Party may well prove the most significant contest before

the Democratic National Convention of 1964. For the issue

is not simply which of two groups wears shiny badges of

accreditation, but, far more fundamentally, whether the

National Democratic Party takes its place with the op

pressed Negroes of Mississippi or their white oppressors,

with those loyal to the National Democratic Party or those

who have spewed hatred upon President Kennedy and

President Johnson and the principles to which they dedi

cated their lives. In the final analysis, the issue is one of

principle: whether the National Democratic Party, the

greatest political instrument for human progress in the

history of our nation, shall walk backward with the bigoted

power structure of Mississippi or stride ahead with those

who would build the State and the Nation in the image of

the Democratic Party’s greatest leaders—Thomas Jeffer

son, Andrew Jackson, and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

This is a legal brief and as such will cover both the facts

and the law. But the legal precedents are necessarily lim

ited, for the courts of this country have many times made

clear that they will not decide political questions or inter

vene in disputes between rival delegations seeking recogni

tion at a party convention.1 This Convention and only this 1

1 Davis v. Hambrack, 58 S.W. 779, 109 Ky. 276 (1900); Phelps v.

Piper, 67 N.W. 755, 48 Neb. 724 (1896); Smith v. McQueen, 166 So.

788, 232 Ala. 90 (1936); Wood v. State, 142 So. 747, 169 Miss. 790

(1932).

(1)

2

Convention can decide who are the proper delegates per

mitted to join in its deliberations.2 3 As Governor Paul B.

Johnson said in his keynote address to the Mississippi

Democratic Party Convention on July 28, 1964, the ques

tion of which delegation to seat “ is a decision that the

National Party will have to make.” And this was also

conceded ten days earlier by Mississippi Democratic Party

Chairman, Bidwell Adam, who said that the National Con

vention ‘ 4 * * could seat them [Freedom Party] if they wanted

to . . . They could seat a dozen dead dodos brought there

in silver caskets and nobody could do anything about it.” 8

Without appreciating Mr. Adam’s analogy, the principle is

clear beyond peradventure of doubt that this Convention is

the court of last resort.

But the sparsity of legal precedents does not mean an

absence of legal principles and guideposts to assist the

Convention in arriving at its choice between two rival

delegations. We believe that the rules of the Convention

and accepted legal principles, as applied to the facts of

this dispute, demonstrate overwhelmingly that the only

valid decision this Convention can make—both in law and

in equity—is to seat the delegation duly chosen by the

state convention of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic

Party on August 6, 1964.

The Freedom delegation comes as “ bona fide Democrats

who have the interests, welfare and success of the Demo

cratic Party at heart, and will participate in the Conven

tion in good faith . . J We come as volunteers to lend sup

2 18 Am. Jur., Elections, §136; Cain v. Page, 42 S.W. 336, 19

K.L.R. 977 (1897); Kearns v. Howley, 41 A. 273, 188 Pa. 116 (1898).

3 New York Times, July 20, 1964, p. 21.

4 Resolution of the Democratic National Committee contained in

February 26, 1964 Call For the 1964 Democratic National Con

vention.

3

port to the nominees of this Convention and to spread the

principles and platform of the Democratic Party. We come

as representatives of a functioning political organization;

for this and other reasons 5 6 7 8 the challenge of the Freedom

Party has no counterpart anywhere else in the South. And

we come with the support of State Democratic Conventions

or State Democratic Committees of California, Colorado,

District of Columbia, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota,

New York, Oregon, Washington and Wisconsin who have

recognized the legality of our position and the justice of

our cause.

The “ traditional” Mississippi delegation does not come

as “ bona fide Democrats” willing to “ participate in the

Convention in good faith . . .6 The delegates to the state

convention of the Mississippi Democratic Party on July

28th arrived in cars bearing Goldwater bumper stickers,7

“ openly voiced themselves during recess and prior to the

convention being called to order, as favoring the candidacy

of Senator Barry Goldwater, ’ ’ 8 adopted a Goldwater plat

form,9 and then recessed until September 9 “ for the purpose

of allowing the Convention to swing to Goldwater . . . ” 10 11

This recess is the regular short interlude which takes place

once every 4 years to attend the National Convention while

the rest of the time is spent in calling President Kennedy

a “ dimwit” 11 and President Johnson a “ counterfeit con

5 See Law Enforcement in Mississippi, a Special Report of the

Southern Regional Council, July 14, 1964, which concluded that

Mississippi is “ not like any place else” (p. 6).

6 See n. 4, supra.

7 New York Times, July 29, 1964, p. 18.

8 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, July 29, 1964, p. 18.

9 See pp. 22 to 23, infra.

10 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, July 29, 1964, p. 18.

11 See p. 24, infra.

4

federate.” 12 13 Indeed, it is not clear why the “ traditional”

Party leaders should even want to send delegates to the

Convention of a national party from which they regularly

declare their independence and to which they continuously

profess deep-seated animosity. Quite likely it is because

they do not want any other group—e.g. the Mississippi

Freedom Democratic Party—to function in Mississippi as

the representative of the National Party. Obviously, this

strategy of fighting against the National Party and still

not allowing any other group to represent it in Mississippi

is what Governor Johnson had in mind when, in his key

note to the July 28th state convention, he said “ this is a

time . . . for carefully-designed strategy . . . for judiciously-

chosen words.” But no matter how “ judiciously-chosen”

the words, the “ carefully-designed strategy” is one of “ bad

faith” to the National Democratic Party.

We are not only willing to serve the National Democratic

Party here and in Mississippi, we assert our right and

our determination to do so. We hope that the delegates of

the Freedom Party may be placed on the temporary rolls

of the Convention by the Democratic National Committee

or Subcommittee 1S and that the contest may end at that

point. If it does not, we hope that a majority of the Cre

dentials Committee of the Convention will determine that

the Freedom Party be placed on the permanent rolls of the

12 See p. 25, infra.

13 The Democratic National Committee has always heard chal

lenges prior to determining which of two groups should he placed on

the temporary rolls. For example, the Credentials Subcommittee of

the Democratic National Committee heard the dispute over which

Puerto Rican delegation should be seated in 1960 prior to the

National Committee’s action on the temporary rolls. Certainly the

challenge made by the Freedom Party is at least as significant to

the future of the Democratic Party as that made by the Puerto Rican

rivals in 1960.

5

Convention. But if unsuccessful there, too, we are deter

mined to put our case before the delegates themselves.14

We are confident that the assembled representatives of this

great, liberal Party will not turn its back on those who

have sacrificed so much to support it.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

I

WHY THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC

PARTY WAS FORMED

A. Negroes Have Traditionally Been Excluded From All

Participation in the Mississippi Democratic Party

(i) Party Runs State. The Mississippi Democratic

Party runs the State of Mississippi. It controls the Legis

lative, Executive and Judicial Branches of the Government

of the State. All 49 Senators and all but one of the 122

Representatives are Democrats. There is no substantial

Republican Party; there is no third party. There is just

the Mississippi Democratic Party and its leaders are the

State. As Governor Johnson said in his keynote to the

“ traditional” state convention, the Mississippi Democratic

Party “ holds all but a handful of the elective and appoint

ive offices, from constable to governor . . . for the past 89

14 We understand that 10% of the 108-member Credentials Com

mittee or eleven members may file a minority report (Cannon,

Democratic Manual far the Democratic National Convention of

1964, p. 35) and that a majority of eight State delegations may

obtain a roll call (Id., p. 54). We are sending a copy of this Brief to

Speaker John McCormack, the Permanent Chairman of the Con

vention, and to Senator John 0. Pastore, the Temporary Chairman

of the Convention, and are calling their attention to this footnote,

so that they may be advised of the intentions of the Freedom Party

and may in turn advise us if they have any different construction of

the rules of the Convention.

6

years, [it] is the framework, or the structure, through

which Mississippians maintain political unity, and operate

self-government. ’ ’

(ii) Party prevents Negro Registration. The Missis

sippi Democratic Party uses its powers to exclude Ne

groes from registering and voting. Though Negroes rep

resent over 40% of the State’s population, all voter regis

trars in Mississippi are white. Today only some 28,500

Negroes are registered in Mississippi, as compared to

500,000 whites. This represents only 6.7% of the 435,000

Negroes 21 years of age in the State; this 6.7% should he

compared with 39.1% in Georgia, 51.1% in Florida and

57.7% in Texas, and even Governor Wallace’s Alabama has

over three times as high a percentage of registered Negroes

as does Mississippi.15 While Negro registration in other

Southern States increased sharply in recent months and

years,16 Mississippi went in the other direction; “ the best

estimate of 1962 registration indicates a drop in registra

tion of 534.” 17

Keeping Negroes from registering and voting has been

accomplished in a myriad of ways. The legislature and the

white voter registrars have combined to make an obstacle

course out of the simple process of registration. A series

of state laws culminating in 1962 gives unlimited discre

tion to the white registrars to find that Negro applicants

cannot interpret the constitution, cannot understand the

obligations of citizenship, are not of good moral character,

15 See report of Southern Regional Council for complete study

of Negro registration in South. Washington Post, Aug. 3, 1964, p. 2.

16 Ibid. For example, in the two years ending this past April,

Negro registration in South Carolina increased by 32,140—more

than the total Mississippi Negro registration.

17 Report of the United States Commission on Civil Rights— 1963,

p. 20.

7

etc. As Professor Russell H. Barrett of the University of

Mississippi said in a recent speech:

“ First, the whole pattern of voting requirements

and of the registration form is calculated to make the

process appear to the voter to be a hopelessly for

midable one. The pattern is supposed to bristle with

complexities which culminate in the publication of the

would-be voter’s name in the local newspaper for two

weeks. A major purpose of all this is to so overwhelm

the voter that he will not have the audacity even to

attempt registration. Behind this approach is supposed

to be—and all too often is—a collection of fears that

someone will challenge the voter’s moral character,

that he may be prosecuted for perjury, or that he may

be subjected to economic or other pressures if he

attempts to register. Those who have for years con

trolled state politics assume that this fear will be a

powerful weapon against voter registration, yet the

plain fact is that it is by far the most vulnerable of

their defenses . . .

“ A second important point is that the law provides

no clear or meaningful standards for its highly general

requirements. These now familiar generalities require

the voter to be able to explain any section of the con

stitution, to describe the obligations of citizenship, and

to demonstrate to the Circuit Clerk that he is good

moral character. It is clear that those requirements

were stated vaguely for one simple reason, to permit

the Registrar to apply different standards to different

people.

“ . • • it is worth quoting what was said in 1955 by

the man who was then President of the Mississippi Cir

cuit Clerks’ Association, Rubel Phillips. In complain

ing about the burden placed by the new law on circuit

clerks, lie said, ‘ Many clerks feel the law is discrimi

natory and that a burden is placed on them to dis

franchise many persons who have been voting for

years. . . . Lawyers with less than 10 years of experi

ence probably wouldn’t be able to answer the questions

properly . . . ’ ” 18

If the Negro finally does surmount all these hurdles,

cruel economic harassment follows. Jobs are lost, credit

withdrawn, supplies refused. Indeed, the 1962 Mississippi

law expressly provides for publication of the names and

addresses of applicants in the newspapers, enabling eco

nomic pressure to be applied during the registration

process.19

If the Negro should be able to run the registration obstacle

course and brave the economic reprisals, dangers to life

and limb are very real.

* In 1955, Lamar Smith, a Negro, was killed after

urging other Negroes to vote in a gubernatorial elec

tion. He was shot to death on the Brookhaven, Miss.,

courthouse lawn. A grand jury refused to indict the

three men who were charged with the slaying.

* In 1961, Herbert Lee, a Negro active in voter regis

tration activities in Liberty, Miss., was shot to death

by a member of the Mississippi State Legislature.

Representative E. E. Hurst, a Citizens’ Council mem

ber, was vindicated by the coroner’s jury, which ruled

the murder a “ justifiable homicide.”

* In 1964, a witness to the Lee killing, Louis Allen,

was shot to death near his home. Allen had been

harassed by local police officials several times since

18 Mississippi Free Press, April 18, 1964, p. 1, 4.

19 Mississippi Code, § 3212.7, approved May 26, 1962. See also

Washington Daily News, August 12, 1964, p. 27.

9

the Lee killing. Local authorities there say they have

not come up with any clues in the Allen killing.

* In 1962, Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer of Euleville, Miss.,

Vice Chairman of the Freedom Party delegation here,

was fired from her plantation job, where she had

worked for 18 years, the same day she had gone to

the county courthouse to attempt to register. The

plantation owner informed her that she had to leave

if she didn’t withdraw her application for regis

tration.

* Leonard Davis of Euleville was a sanitation worker

for the city until 1962, when he was told by Euleville

Mayor Charles M. Dorrough, “ W e’re going to let

you go. Your wife’s been attending that school.”

Dorrough was referring to the Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee registration school in Eule

ville.

* Marylene Burkes and Vivian Hillet of Euleville were

severely wounded when an unidentified assailant fired

a rifle through the window of Miss Hillet’s grand

parents’ home. The grandparents had been active

in voter registration work.

* In Eankin County in 1963, the sheriff and two deputies

assaulted three Negroes in the courthouse who were

applying to register, driving the three out before

they could finish the forms.

* In Philadelphia, Mississippi, in 1964, three students,

part of the 1964 summer registration drive, were

killed.20

20 Mississippi—Subversion of the Right to Vote, Pamphlet of the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Atlanta, Georgia,

1964. This pamphlet reports each of the above examples except

the last—which requires no documentation.

10

In the words of the Mississippi Advisory Committee to

the United States Commission on Civil Eights, a body com

posed entirely of Mississippians, “ terror hangs over the

Negro in Mississippi and is an expectancy for those who

refuse to accept their color as a badge of inferiority. ’ ’ 21

And the Southern Eegional Council, a body composed en

tirely of Southerners, recently documented “ the almost

unrestrained lawlessness which is permitted within the

state against one class of people.” 22

Strange as it may seem, even obstacle course registra

tion, intense economic pressure and frightening terror are

not all. The statutes of Mississippi provide that “ No person

shall be eligible to participate in any primary election unless

he . . . is in accord with the statement of the principles of

the party holding such primary, which principles shall have

been declared by the state convention of the party holding

the primary . . . ” 23 And, carrying this out, the 1960 Plat

form and Principles of the Mississippi Democratic Party

adopted June 30, 1960, provides:

“ We hold as a prerequisite to voting in the Missis

sippi Democratic Primaries, or otherwise participating

in the affairs of the Mississippi State Democratic Party,

that the voter shall subscribe to the principles and plat

form of the party, and shall thereby repudiate his

affiliation with any other party whatsoever, and affirm

his allegiance to the Democratic Party of the State of

Mississippi and to its principles and platform.”

Probably the single most sacred principle of the Missis

sippi Democratic Party is segregation. The 1960 Platform

provides:

21 Report on Mississippi, January, 1963, p. 23.

22 See n. 5, supra.

28 Mississippi Code, §3129.

11

“ We believe in the segregation of the races and are

unalterably opposed to the repeal or modification of

the segregation laws of this State, and we condemn

integration and the practice of non-segregation.”

The resolution at the 1964 State Convention on July 28

provides:

“ We believe in separation of the races in all phases

of our society. It is our belief that the separation of the

races is necessary for the peace and tranquility of all

the people of Mississippi and the continuing good rela

tionship which has existed over the years.”

In a nutshell, the Mississippi Democratic Party makes a

belief in segregation a prerequisite to participation in its

affairs and thus in the political life and government of the

State. A Negro’s mere belief in his own dignity and the

United States Constitution makes him ineligible to partici

pate in the political processes of Mississippi.

(iii) Total Exclusion of Negroes. Never was the exclu

sion of Negroes more successfully carried on than in the

selection of the delegation representing the Mississippi

Democratic Party at this Convention.

Negroes in several parts of Mississippi attempted to

attend the June 16th precinct meetings of the “ traditional”

Party. These meetings, in which all registered voters are

theoretically entitled to participate, form the base of a pyra

mid which culminates in the Democratic State Convention.

It is in the course of this series of meetings (precinct,

county and state conventions) that state party officials and

National Convention delegates are elected. In this Presi

dential election year the registered Negroes, though few in

number, were fighting not only for their right to be included

in the Party, but also to insure that the State Party would

1 2

remain loyal to the candidates of the National Democratic

Party in November. To accomplish this, they pressed for the

election of delegates who shared their views, as well as for

the adoption of resolutions affirming loyalty to the national

ticket.

The amount of Negro activity in the precinct meetings was

sharply circumscribed at the outset by the outstanding fact

of Mississippi politics: the almost complete disfranchise

ment of Negro voters. The climate of fear that pervades the

state acted as a further check: a sworn affidavit from a resi

dent of Neshoba County, for example, explains that no Ne

groes went to precinct meetings there ‘ because it was im

possible . . . to make the attempt . . . without suffering-

great economic and physical harm.” 24 This is, of course,

the county where the three students were killed in June.

But despite the obstacles, many Negroes did attempt to

participate in the precinct, county and state conventions.

To no avail.

In many precincts Negroes went to their polling stations

before the time designated by statute for the precinct meet

ings (10:00 AM), but were unable to find any evidence

of a meeting. Inquiries addressed to public officials proved

futile: some officials denied knowledge of any meeting,

others claimed that the meeting had already taken place.

In these precincts Negroes proceeded to hold their own meet

ings and elected their own delegates to the county conven

tions. In other precincts Negroes found the white precinct

meetings, hut were excluded. In Hattiesburg Negroes were

told that they could not participate without poll tax receipts,

despite the recent Constitutional amendment outlawing such

requirements. In still other precincts Negroes were allowed

to attend the meetings, but were restricted in some way

24 This and other affidavits referred to are in the possession of

the counsel for the Freedom Party.

13

from exercising their full rights: some were not allowed

to vote, some were not allowed to nominate delegates from

the floor, others were not allowed to take part in choosing

those who tallied the votes. In several meetings the Negroes

were unable to introduce their resolution calling for loyalty

to the National Party; in others they were unable to bring

their “ loyalty” resolutions to a vote; and in the three

instances where “ loyalty” resolutions were brought to a

vote, they were overwhelmingly defeated.

On June 23,1964, Negroes tried to take part in the second

level of Democratic Party meetings, the county conventions.

Most of them had been elected delegates to the county level

by all-Negro precinct meetings. One, however, was a dele

gate from a multi-racial meeting in Jackson. In Madison

county, Negro delegates were excluded by a claim that the

meeting was of the County Executive Committee (not a

convention) and was thus open only to members. In Le

flore county, the white convention officials refused to recog

nize the Negroes’ credentials. In Washington county, Negro

delegates were not allowed to participate meaningfully-—

the meeting refused even to consider their resolution of

loyalty to the National Democratic Party. And so on.25

By the time the apex of the pyramid was reached—the

state convention—there was not a single Negro delegate in

a state with 435,000 Negroes of voting age. The exclusion

was complete. Furthermore, and possibly even more signifi

cant here, there was not a single delegate to the state con

vention, white or black, willing even to offer a resolution

of support for the National Democratic Party.

(iv) Conclusion. There has not been a single Negro

State office holder in Mississippi since 1892—the inevitable

25 The facts concerning the precinct and county conventions are

documented by affidavits and statements in the possession of the

counsel for the Freedom Party.

14

result of this total exclusion from the political process.

Negroes have been harassed and brutalized by the officials

of a state wholly controlled by the “ traditional” Demo

cratic Party. Yet, despite the hopelessness and tragedy of

their position, the Negroes of Mississippi have maintained

their belief in the democratic process and in the Democratic

Party.

B. The Mississipi Freedom Democratic Party Desires to

Work Within the Framework of the National

Democratic Party

At its convention on August 6,1964, the Mississippi Free

dom Democratic Party unanimously resolved that, “ We

deem ourselves part and parcel of the National Democratic

Party and proudly announce our adherence to it. We affirm

our belief that the National Democratic Platform of recent

years has been a great liberal manifesto dedicated to the

best interest of the people of our Nation of all races, creeds

and colors.”

These were not just words to bring to this Convention.

Those who organized the Freedom Party had a deep dedi

cation to the National Democratic Party. They did not

seek an alliance with Eepublicans; they did not try to form

a third party. They sought and still seek to be a part of

the National Democratic Party.

Indeed, earlier this year and despite the obstacles that

have been outlined above and more, the Freedom Party ran

candidates in the June 2nd Democratic primary. Mrs.

Victoria Gray, Freedom Party National Committeewoman,

opposed Senator John Stennis; Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer,

likewise a Freedom delegate, opposed Representative Jamie

L. Whitten; the Reverend John Cameron opposed Repre

sentative William M. Colmer; and Mr. James Houston

opposed Representative John Bell Williams. Defeat cannot

15

blur this very real effort to work within the framework of

the Democratic Party.

These primary candidates of the Freedom Party ran on

the Platform of the National Democratic Party. They

articulated the needs of all the people of Mississippi, such

as anti-poverty programs, medicare, aid to education, rural

development, urban renewal, civil rights. They identified

themselves with the National Party and its leaders. They

demonstrated, even before the August 6th Freedom Party

state convention, that they were “ part and parcel of the

National Democratic Party.”

* # # =K= * # . #

That is the story of why the Mississippi Freedom Demo

cratic Party was formed—because the Negroes of Missis

sippi, totally excluded from political life by the Mississippi

Democratic Party, nevertheless made their choice to work

within the framework of the National Democratic Party.

Now we turn from why the Mississippi Freedom Democratic

Party was formed, to its organization and its operation.

II

ORGANIZATION AND OPERATION OF THE

MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY

(i) Freedom Party Formed. The Mississippi Freedom

Democratic Party was officially established at a meeting in

Jackson, Mississippi, on April 26, 1964. The 200 to 300

delegates present elected a temporary state executive com

mittee of 12 persons and the committee met regularly there

after. The Party is open to all Democrats in Mississippi

of voting age, regardless of race, creed or color.

(ii) Freedom Party Follows Law. The Mississippi

Freedom Democratic Party has made every possible

16

effort to follow the laws of Mississippi regulating political

parties.

* It prepared a Freedom Registration Form and en

rolled voters into the Freedom Party. As of the

moment of the completion of this Brief, over 50,000

Mississippi residents of voting age were registered

in the Freedom Party. Rev. Robert Spike, Executive

Director of the Commission on Race and Religion of

the National Council of Churches, described the

Freedom Registration as “ a remarkable achievement

in the face of the most serious obstacles.” 26

* During the weeks of July 19 and 26, 1964, there were

precinct meetings in 26 counties throughout the State

of Mississippi. An estimated total of 3500 persons

participated in these meetings.

■* During the week of July 27, 1964, county conven

tions were held in 35 counties at which a total of 282

delegates were elected to the state convention. In 9

of the 35 counties the Freedom Party was unable to

hold precinct meetings in the precincts because of

various forms of harassment; instead, the precinct

meetings were held immediately preceding the county

conventions.

* Some county meetings in addition to the 35 were held

in Jackson, since holding them in the proper coun- 28

28 In November, 1963, 83,000 Mississippi citizens, largely Negroes

barred from the “ traditional'’ Party, voted for Mr. Aaron Henry

(Chairman of the Freedom delegation here) for Governor in a mock

election. Only the cruelest harassment prevented the Freedom Party

from doubling that figure in the present registration. The type of

harassment ranged from the murder of the three boys in Philadelphia

down to the beating of two Freedom registration workers driving a

truck containing Freedom registration forms.

17

ties would have endangered lives. Neshoba county,

with the county seat at Philadelphia, Mississippi, was

an example of such a county.

* On August 6, 1964, 240 delegates assembled at the

Freedom Party state convention in Jackson to elect

the officers of the Freedom Party, choose the dele

gation to this Convention and adopt a Platform and

Principles.

* Efforts were made to register the Freedom Party

with the Secretary of State of Mississippi both before

and after the state convention of August 6th, but all

such efforts were rebuffed.

The figures on Freedom Party registration and the at

tendance at precinct and county conventions demonstrate

the seriousness with which the Party has gone at its task

of organizing a state party to serve the National Party. And

all of this was accomplished in the face of ugly harass

ment and intimidation.

Harassment took a variety of forms. Bequests made in

Sunflower County, Lauderdale County, and Madison County

for maps or descriptions of precinct boundaries were not

even answered. Attempts to publicize precinct meetings as

required by state law proved futile as newspapers and radio

stations refused to print the advertisements or to announce

them. In some areas of the state it was felt that the meet

ings could not be safely publicized as earlier announcements

had led to bombings or attempted burnings in Pike County.

In Leake County a radio station requested the Party to

withdraw- its announcement. The manager of the station,

displaying letters from the mayor, the chief of police, and

the sheriff, feared reprisals against the property of the

station as well as the families of the employees of the sta

18

tion. Meeting's were often followed by arrests of local par

ticipants for minor driving offenses or interrogation of

those who had attended. In one case, a truck carrying

Freedom Registration forms was detained for over a day,

two of its occupants taken to jail and beaten and two other

of its occupants told to start walking back to Jackson.

These incidents only complemented the continual harass

ment of the Party. In one day, June 24, 1964, the Jackson

office of the Council of Federated Organizations reported

16 incidents of intimidation or violence, and other days in

which ten or more such incidents were reported were not

uncommon.27.

(iii) Freedom Party Convention. The Freedom Party

convention of August 6 democratically elected a National

Committeeman (Rev. Edwin King), a National Committee-

woman (Mrs. Victoria Gray), 44 delegates and 22 alter

nates to the Convention. They are honorable, hard-work

ing and loyal Mississippians; 28 their names are set forth in

Appendix B, but addresses and biographies, in the posses

sion of counsel, are withheld for reasons of personal safety.

Many of them are making great personal sacrifices to attend

this Convention; they do so because of their deep dedication

to the liberal principles of the National Democratic Party.29

The delegates to the state convention unanimously ex

27 The facts concerning harassment and intimidation are docu

mented by affidavits and statements in the possession of the Counsel

for the Freedom Party.

28 The delegation has 64 Negroes and 4 whites. The Party is open

to all Democrats, and the number of whites on the delegation was

limited solely by the number willing to brave certain reprisal.

29 By secret ballot, as required by Mississippi statute, Mr. Aaron

Henry and Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer were elected Chairman and

Vice Chairman of the delegation, respectively. Mrs. Annie Devine

was elected Secretary.

19

pressed their dedication to the National Party in the fol

lowing Statement of Loyalty:

“ As members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic

Party:

“ 1. "We undertake to assure that voters of the State

of Mississippi will have the opportunity to cast their

election ballots for President Lyndon B. Johnson and

the Vice Presidential nominee selected by the Demo

cratic National Convention at Atlantic City, and for

electors pledged formally or in good conscience to the

election of President Johnson and the Vice Presiden

tial nominee, under the Democratic Party label and

designation.

“ 2. We go farther than the above undertaking re

quired by the rules of the Democratic National Con

vention and pledge to work dauntlessly for the election

of President Lyndon B. Johnson and the Vice Presi

dential nominee selected by the Atlantic City con

vention.

“ 3. We deem ourselves part and parcel of the Na

tional Democratic Party and proudly announce our

adherence to it.

“ 4. We affirm our belief that the National Demo

cratic Platform of recent years has been a great liberal

manifesto dedicated to the best interest of the people

of our Nation of all races, creeds, and colors. We will

proudly support the 1964 platform and the 1964 candi

dates of the Democratic National Party.”

The Convention also adopted a platform supporting full

employment, collective bargaining, food stamp programs,

medicare, civil rights, reapportionment, job retraining, an

anti-poverty program, United Nations, foreign aid, and

20

the Peace Corps. In a word, it identified itself with the

basic programs and principles of the National Democratic

Party.30

(iv) Freedom Party Delegates Certified. The Free

dom Party delegates elected at the August 6th con

vention were certified to the Chairman, John W. Bailey,

and the Secretary, Mrs. Dorothy Vredenburgh Bush,

of the Democratic National Committee that same day and

the certification was delivered to Mr. Bailey’s office on

August 7th, the day after the convention. This certification

was contained in a letter of August 6th from Mr. Lawrence

Guyot, Chairman of the Freedom Party, to Mr. Bailey,

requesting that the delegation be seated in place of the

delegation chosen on July 28th by the Mississippi Demo

cratic Party. This challenge followed an earlier letter from

Mr. Aaron Henry, previous chairman of the Freedom Party,

to Mr. Bailey, dated July 17, 1964, challenging “ the dele

gation of the ‘ regular’ Democratic Party” and asserting

“ the right of the delegation of the Mississippi Freedom

Democratic Party to be seated at the National Convention

as the true representative of Mississippi Democrats.” Mr.

Bailey was invited in the July 17th letter to attend the state

convention on August 6th or send an observer, but he was

not able to do so. The text of the Freedom Party letters of

July 17th and August 6th are set forth in Appendix B.

30 The Platform and Principles of the Mississippi Freedom Demo

cratic Party, adopted at the state convention on August 6th, is set

forth in full in Appendix A.

21

III

OPERATION OF THE MISSISSIPPI DEMOCRATIC

PARTY

(i) “ Traditional” Party Asserts Independence. Where

as the Freedom Party has made every effort to work

within the framework of the National Democratic Party,

the “ traditional” Party has been at equal pains to

demonstrate its independence of the National Party. The

Mississippi Democratic Party has over and again declared

in public speeches and printed matter that it is not a part

of the National Democratic Party. The campaign litera

ture for the election of Governor Paul B. Johnson, in Novem

ber of 1963, could not be clearer on this point: ‘ * Our Mis

sissippi Democratic Party is entirely independent and free

of the influence or domination of any national party” . . .

“ The Mississippi Democratic Party, which long ago sepa

rated itself from the National Democratic Party, and which

has fought everything both national parties stand for . . .”

“ Both the National Democratic Party and the National

Republican Party are the dedicated enemies of the people

of Mississippi.” 31 As late as June 25th of this year, Gov

ernor Johnson announced, “ We haven’t left the National

Democratic Party, the National Democratic Party has left

us.” 32 Former Governor Ross Barnett flatly stated that

“ there is no place for Mississippi today in national Demo

cratic or Republican parties. ’ ’ 33 Former Governor J. P.

Coleman said, “ This party has always been separate and

distinct from the national party.” 34 And Bidwell Adam,

State Democratic Chairman, publicly announced he was

31 The Johnson Journal, Vol. I ll , 1963, p. 1.

32 Jackson-Clarion-Ledger, June 26, 1964, p. 14.

88 Biloxi-Gulfport Daily Herald, March 26, 1963, p. 1

34 Biloxi-Gulfport Daily Herald, May 10,1963, p. 1.

22

“ through with the National Democratic Party. The Na

tional Democratic Party will have to get somebody else to

carry their banner. ’ ’ 35 Governors Coleman, Barnett and

Johnson and State Chairman Adam, the leaders of the

“ traditional” party, may sing a different tune through their

underlings at this Convention, but they cannot hide the

words they use in Mississippi—that they will have nothing

whatever to do with the National Democratic Party.

(ii) “ Traditional” Party Opposes National Platform.

The Mississippi Democratic Party has done far more

than merely shout that it is not a part of the National

Democratic Party. More fundamentally, it has opposed, and

today opposes, everything for which the National Party

stands.

On August 16,1960, after the Kennedy-Johnson ticket was

nominated, the recessed state convention resolved “ that we

reject and oppose the platforms of both National Parties

and their candidates.” Their leaders—the same leaders

who are sending a delegation to this Convention—success

fully campaigned for unpledged electors who cast their votes

against President John P. Kennedy and Vice President

Lyndon B. Johnson.

At their state convention just last month the “ tradi

tional” Party passed resolution after resolution opposing

everything which the Democratic National Party has done

and for which it stands. The state convention called for

the repeal of the Civil Eights Act of 1964 which it denounced

“ as a naked grasp for extreme and unconstitutional Fed

eral power” and “ a betrayal of the American people.” It

favored “ getting the United States out of the United Na

tions, and the United Nations out of the United States.” It

favored limiting the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court and

removing certain of its members. The general philosophy

35 Montgomery Advertiser, September 29, 1962, p. 7A.

23

of the “ traditional” state convention was probably best

expressed in the following resolution:

“ We express our admiration, and appreciation of

Governor Eoss E. Barnett and Governor George C.

Wallace, of Alabama for their able, courageous, patri

otic and effective work in awakening the American

people to the utter necessity of the return of this

country to true Constitutional Government and indi

vidual freedom.

“ We are greatly indebted to Governor Wallace for

his tremendous visit to Mississippi, and he and Gov

ernor Barnett occupy a permanent place in the heart

of every true Mississippian. ” 86

(iff) “ Traditional” Party Attacks National Leaders.

The violent opposition of the “ traditional” party to

the National Democratic leaders is almost too well known

to repeat in this Brief. Governor Johnson may now speak

with “ judiciously-chosen” words so he can get his delega

tion seated here, but he was not so judicious in his cam

paign in 1963. Time after time he referred to the “ Ken

nedy albatross” around the neck of his opponent or around

the country’s neck.* 37 Four days before his election, Gov

ernor Johnson shouted that “ my determination is to do

anything I can to get the Kennedy dynasty out of the White

86 This resolution sanctifying Governor Wallace only highlights

the irony of excluding the Alabama delegation (apparently everyone

agrees to this exclusion), while at the same time even considering

the seating of the “ traditional” Mississippi delegation. The 20 years

of political perfidy of the “ traditional” Mississippi Party makes

the Alabama record seem almost like one of continued loyalty.

37 See e.g. Biloxi-Guljport Daily Herald, July 2, 1963, p. 11; id.,

July 18, 1963, p. 26; Jackson Clarion-Ledger, July 17, 1963, p. 1;

Time Magazine, August 16, 1963, p. 17.

24

House.” 38 Johnson’s campaign advertisement spoke of

eliminating ‘ ‘ Kennedyism from our state ” ; 39 he said the

choice was between “ political dictatorship sponsored by

John Kennedy” or constitutional government.40 He said

that unless President Kennedy is defeated in 1964, “ you’ve

seen your last free election;” 41 and only this past July

28th at the state convention, Governor Johnson repeated

his belief that this “ threatens to be the last free election

in this fair land.” Johnson said point number one in his

program “ will be to spearhead an all-out effort to secure

cooperation from other governors and leaders to get the

Kennedys out of the White House” 42—small wonder, too,

since he had already referred to them as “ dimwits” . 43 An

official Johnson campaign ad showed a picture of a bed in

which President Kennedy had slept and then stated: ‘ 4 Make

sure that Kennedy never sleeps there again . . ,” 44 As

though to clinch the matter, Governor Johnson’s victory

statement after his election proclaimed to the voters that

“ your victory is one over the Kennedys, the Adlai Steven-

sons and the northern Democratic overlords who also would

like to destroy our way of life.” 45 And as recently as

August 13 of this year, the Washington Post reported that

Governor Johnson laced into the Johnson Administration

as that “ shifting, vacillating, crawfish government in

Washington.”

Other spokesmen for the “ regular” party have also made

38 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, Nov. 2, 1963, p. 8.

39 Biloxi-Gulfport Daily Herald, August 16,1963, p. 9.

40 Biloxi-Gulfport Daily Herald, August 17, 1963, p. 1.

41 Biloxi-Gulfport Daily Herald, Sept. 5, 1963, p. 9.

42 Memphis Commercial Appeal, October 26, 1963, p. 9.

43 Biloxi-Gulfport Daily Herald, July 18, 1963, p. 26.

44 Biloxi-Gulfport Daily Herald, July 9, 1963, p. 6.

45 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, Nov. 7, 1963, p. 1.

25

clear their violent opposition to the National Party’s lead

ers. Former Governor Eoss Barnett, the true hero of the

“ traditional” state convention, has time and again referred

to President Johnson as a “ counterfeit confederate” . On

the 4th of July of this year he termed President Johnson

a “ counterfeit confederate who resigned from the South

and may one day soon resign from the white race as well

. . . ” 40 A few days later he said, “ I would vote for Senator

Goldwater before I would vote for Lyndon Johnson, a coun

terfeit confederate.” 46 47 And on July 22nd the Clarion-

Ledger reported from Houston, Texas: “ Calling Lyndon

Johnson ‘ a counterfeit confederate, ’ Barnett said ‘ he ’ll need

more than an 87-vote landslide in Texas’ to win the Novem

ber election.”

Governors Johnson and Barnett have been ably assisted

by other leaders of the “ traditional” party in their attacks

upon Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. Mrs. Florence

Sillers Ogden of Eosedale, sister of the Speaker of the Mis

sissippi House of Eepresentatives, “ flayed the Kennedy

administration and called on America’s woman-power to

turn back the tide of constitutional destruction which is en

gulfing the nation . . . Never, never vote for a liberal . . .

[We stand for] free enterprise and prayer in the schools

[and oppose] ‘Kennedys, disarmament, and Commu

nism’ ” 48 Congressman John Bell Williams said that

“ Kennedy is the most predatory chief executive of all time.

If we don’t stop him and his brother Bobby, human liberty

will disappear from this nation and the face of the earth. ’ ’ 49

Judge Thomas Brady, temporary chairman at the recent

“ traditional” state convention, went beyond attacks on

46 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, July 6, 1964, p. 5.

47 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, July 18, 1964, p. 8.

48 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, Jan. 20, 1963, p. 10.

49 Biloxi-Gulfport Daily Herald, July 23, 1963, p. 7.

26

Presidents Johnson and Kennedy and called Speaker Sam

Rayburn, who presided over Democratic National Con

ventions more often than any man in history, “ that egg-

headed man from Texas who is an arch-traitor to the

South.” 50

Quite possibly a short excerpt from the Jackson Clarion-

Ledger just after President Kennedy was assassinated best

sums up the Mississippi “ hate” campaign against the lead

ers of the National Democratic Party:

“ At Pascagoula, attorney Robert Oswald resigned

as president of the Mississippi Young Democrats. ‘ The

tragic event in Dallas, Texas, in the light of the ‘ Hate

the Kennedy’ attitude of the leadership of the Missis

sippi Democratic Party and its present administration

should require no further explanation for my ac

tion.’ ” 51

(iv) “ Traditional” Party Villifies Negroes. This atti

tude of hatred towards Presidents Kennedy and John

son, who worked so hard and effectively for civil

rights, is hardly surprising when one pauses to consider the

almost barbaric attitude of the leadership of the “ tradi

tional” Party to Negro citizens. To seat the delegation of

Paul B. Johnson and Ross Barnett, while barring the Free

dom Party from the convention door, would be a deliberate

insult to the Negroes of America who support the National

Party at the behest of those who would destroy it.

The undisputed leader of the Mississippi Democratic

Party is Governor Paul B. Johnson. Mr. Johnson’s attitude

is, purely and simply, one of bigotry. On July 9, 1963, he

bragged that “ in the past few years we lost 270,000 good-

50 Silver, James W., The Closed Society (1963), p. 50.

51 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, Nov. 23,1963, p. 5.

27

for-nothing lazy Negroes . . . ” 52 On July 27, 1963, he said

that Mississippi needs “ an education program to teach some

of our Negroes that they are wasting their time staying in

Mississippi.” 53 Along the same lines, he said, “ You can’t

ask . .. Negro leaders what they want. Y ou . . . tell ’em what

they’re going to get.” 54 And in the Citizens Council Maga

zine for December, 1963, he is quoted as saying: “ I am

proud to have been part of the resistance last Pall to Mere

dith’s entrance at Ole Miss” —resistance for which he is

now under criminal charges for contempt of federal court.

During his 1963 campaign, he repeatedly said, “ You know

what the NAACP stands for: Niggers, alligators, apes,

coons and possums.” 55 And on July 3rd of this year, when

Governor Johnson was asked if owners of public accommo

dations should comply with the Civil Eights Act signed by

President Johnson the day before, he told newsmen, “ I don’t

think they should.” 56 And a few days later, Johnson re

fused even to talk with Commerce Secretary Luther Hodges

and former Governor LeEoy Collins, President Johnson’s

civil rights relations team.57

Governor Eoss Barnett, Paul Johnson’s co-leader of the

“ traditional” Party and his co-defendant in the criminal

contempt case, has a similar attitude towards Negroes. Only

last month he cried out, “ Let there be no misunderstanding

regarding ?ny position and my determination to unflineh-

52 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, July 9, 1963, p. 10.

53 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, July 27, 1963, p. 6.

54 Life Magazine, Feb. 7, 1964, p. 4.

55 Time Magazine, Aug. 16, 1963, p. 17.

56 Jackson Daily News, July 3, 1964, p. 2. Again illustrating how

Mississippi stands aloof from, the changing South, Governor John

son’s statement on the Civil Rights Act should be compared with

that of those numerous other Southern leaders who have called for

compliance.

57 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, July 8, 1964, p. 1.

28

ingly and steadfastly continue to support Governor Wallace

as long as he is in the race.” 08 Nothing less could have

been expected from the Governor, who, like Governor Wal

lace, was in open and malicious defiance of the Supreme

Court and the President of the United States. Flatly stat

ing that “ there is no case in history where the Caucasian

race has survived social integration,” 58 59 he interposed the

rights of the Sovereign State of Mississippi against the

Federal Government. His disregard of constitutional au

thority impelled President Kennedy to use federal marshals

and troops so that a single Negro could enter the University

of Mississippi.

The bigotry of both Governors Barnett and Johnson to

ward the Negroes of their State is nowhere better evidenced

than in their successful warfare against public school in

tegration. Governor Johnson, in a speech to the Citizens

Council on October 25, 1963, made clear his determination

to keep Negro children out of white schools at any cost:

“ As your governor, and as a man, I will resist the

integration of any school anywhere in Mississippi. The

closing of our schools is not the only answer. We can

and will maintain a system of segregated schools! When

local authorities are organized to resist and not sur

render, your governor has great powers which have not

yet been used.

“ We learn from our mistakes. I am proud to have

been part of the resistance last Fall to Meredith’s en

trance at Ole Miss. Mississippi stirred the admiration

of the world by her spirited stand against the Federal

invaders. Yet, it is plain now that we might have done

more, and should do more the next time. Interposition

58 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, July 18,1964, p. 1.

59 M em phis Commercial Appeal, Sept. 14,1962, p. 1.

29

of your governor’s body between the forces of Federal

tyranny and bis people, including our children, is a

price not too great to pay for racial integrity. I pledge

you here tonight that I am prepared to pay such a price!

Remember, there is no such thing as ‘ token’ integration.

So-called ‘ token’ integration is just a break in the levee

that leads to the flood. ’ ’ 60

What this means in further Mississippi violence only time

can tell. Federal court orders are already in existence re

quiring partial integration of schools in Jackson, Biloxi and

Leake County, Governor Johnson has yet to withdraw the

position he so vigorously espoused before the Citizens

Council last fall.

Possibly the most notorious bigot in the leadership of the

“ traditional” Party is Judge Thomas Brady, who acted as

temporary chairman of the “ traditional” state convention

on July 28th and is the present “ traditional” National Com

mitteeman. He is the author of the famous ‘ ‘Black Monday”

in which he called for the formation of a 49th state where

Negroes could be sent and in. which he termed the CIO and

NAAOP “ Communist-front organizations.” 61 In 1957 in

an address to a California audience, Brady, who doubles as

a State Supreme Court Judge, told his audience:

“ I can, however, safely say that based upon the tests

which are available from World War I, and from per

sonal experience, there is a vast gulf of difference be

tween the I. Q. of the Negro of the South, as well as in

America, and the average white man. It is because of an

inherent deficiency in mental ability, of psychological

and temperamental inadequacy. It is because of in

60 The Citizen, Official Journal of the Citizens’ Councils of

America, December, 1963, p. 10.

61 Brady, Tom P., Black Monday (1955), p. 73, 69.

30

difference and natural indolence on the part of the

Negro. All the races of the earth started out at approxi

mately the same time in God’s calendar, hut of all the

races that have been on this earth, the Negro race is the

only race that lacked mental ability and the imagination

to put its dreams, hopes and thoughts in writing. The

Negro is the only race that was unable to invent even

picture writing. ’ ’ 62

Equally degrading to Negroes is this statement by Judge

Brady:

“ The purpose of this comparison is not to embarrass

or humiliate anyone. You can dress a chimpanzee,

housebreak him, and teach him to use a knife and fork,

but it will take countless generations of evolutionary

development, if ever, before you can convince him that

a caterpillar or a cockroach is not a delicacy. Likewise

the social, political, economic and religious preferences

of the negro remain close to the caterpillar and the

cockroach . . . It is merely a matter of taste. A cock

roach or caterpillar remains proper food for a chim

panzee.” 63

In 1960, Judge Brady was the only National Committee

man who refused to take the loyalty oath required by the

rules of the Democratic National Convention. He returned

to Mississippi and supported the unpledged elector slate

against those pledged to John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B.

Johnson and termed the Democratic Platform “ very similar

to the Constitution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Repub-

; 62 Address by Judge Tom Brady to the Commonwealth Club of

California at San Francisco, Oct. 4, 1957.

63 Black Monday, p. 12.

31

lies. . . . ” 64 65 Only recently he called for an economic boycott

against businessmen who voluntarily comply with the Civil

Rights A ct.66 Although he has never previously had the

gall to present his credentials to the Democratic National

Committee, the “ traditional” state convention had the

effrontery to elect him as a delegate to this Convention.00

(v) “ Traditional” Party for Goldwater. The “ tra

ditional” state convention of July 28 showed the true

colors of that Party in more ways than just electing

Brady a delegate. The delegates arrived in ears bearing

Goldwater bumper stickers,67 “ openly voiced themselves

during recess and prior to the Convention being called to

order as favoring the candidacy of Senator Barry Gold-

water” 68 and then recessed until September 9 “ for the pur

pose of allowing the Convention to swing to Goldwater

. . ,69 As Richard Corrigan reported to the Washington Post

from Jackson on August 2, 1964:

‘ ‘ In their convention last week, the Democrats muffled

their enthusiams for Sen. Goldwater to protect their

delegation to Atlantic City. They voted to send an un

instructed delegation and resolved that the national

convention’s nominees will appear on the ballot here

next November, come what may.

“ The Jackson convention took these steps to head off

64 Jackson Clarion-Ledger, October 26, I960, p. 14.

65 Jackson Daily News, July 8, 1964, p. 6.

86 Recently, Brady has even announced that he will attend the

Democratic National Committee meeting prior to the Convention.

Memphis Commercial Appeal, August 6, 1964, p. 18. Brady’s suc

cessor as committeeman will be E. K. Collins, who, on Sept. 25, 1962,

proclaimed: “ We must win this fight regardless of the cost in human

lives.” Silver, n. 50, p. 118.

67 See n. 7, supra.

68 See n. 8, supra.

69 See n. 10, supra.

32

the challenge of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic

Party, a bi-racial pro-Johnson organization which will

try to unseat the regulars at the national convention.

“ When the State convention reconvenes on Sept. 9

it is expected to endorse Sen. Goldwater.”

But all this was only the final act of 20 years of political

perfidy by the Mississippi Democratic Party, to which we

now turn.

(vi) Twenty Tears of Political Perfidy. In 1944,

the Mississippi State Democratic Convention freed its

presidential electors from the obligation to vote for the

National Convention nominees.

In 1948, the Mississippi delegates bolted the National

Democratic Convention. National committee members and

other leaders of the Mississippi Democratic Party disasso

ciated themselves from the National Democratic nominees

and supported the “ States Rights” candidates. The Gov

ernor of Mississippi, Fielding L. Wright, joined the States

Rights ticket as Vice Presidential nominee and helped cap

ture the State for Strom Thurmond.

In 1952 and 1956 the Mississippi Democratic Party con

tinued this guerrilla warfare against the National Party.

It redoubled its efforts to exclude Negroes loyal to the Na

tional Party and it “ interposed” segregation against the

principles of the National Party. Nevertheless, in both the

1952 and 1956 National Conventions, the “ regulars” were

seated at the expense of loyalist delegations seeking the

right to support the National Party.

In 1960 the 4 4 traditional ’ ’ state convention recessed so its

delegation could attend the National Convention. After the

nomination of President Kennedy and Vice President John

son, the reconvened state convention rejected these candi

dates and opposed the platform adopted by the National

33

Party. With the vociferous support of then Governor Bar

nett, the unpledged electors won the November election and

all eight Mississippi electorial votes were cast for Senator

Byrd of Virginia.

In 1964 history is about to repeat. As we have already

seen, the “ traditional” convention recessed so it could

send delegates to this Convention and then reconvene “ for

the purpose of allowing the [State] Convention to swing to

Goldwater . . .” 70 Can this Convention blind itself to what

everybody sees?

(vii) “ Traditional” Party Leaders Duck Convention.

The “ traditional” Party’s contempt for the National Party

is evidenced once more in the delegation which it is

sending to this convention. Governor Johnson is not a

delegate; neither is the Lieutenant Governor, the Attorney

General, ex-Governor Barnett, ex-Governor Coleman, Sen

ator Stennis, Senator Eastland, any of the five Congress

men, or even the Party Chairman. As George Carmack, a

Scripps-Howard staff writer, reported from Jackson the

day after the Convention, this is a “ Joe Doakes delega

tion.” 71

The state convention had obvious reasons for sending a

“ Joe Doakes delegation. ’ ’ There is no one among the group

who can be asked to make a pledge to the National Conven

tion or whose pledge, if asked and given, would bind the

leaders of the “ traditional” Party. There is no one to

pledge the leadership of the Party to support President

Johnson. There is no one to pledge the leadership to admit

Negroes to the Party in the future. There are only the

Joe Doakeses to warm the Mississippi seats at the National

Convention and thus to keep the Freedom delegates from

being seated. We believe we have the right to ask whether

70 See n. 10, supra.

71 Washington Daily News. July 29, 1964, p. 7.

34

this Convention is going to prefer the Johnson-Barnett

minions to loyal Democrats who have been crushed under

their boots.

(viii) Conclusion. For 20 years, the Mississippi Demo

cratic Party has not wanted to be a part of the National

Party. It has claimed its independence of the National

Party and its leaders have spewed hatred upon the

candidates and principles of the National Party. Why,

then, do they come here every four years and ask to

be seated in the National Party? The answer is not

far to seek. While the “ traditional” Party does not

want to be a part of the National Party, it does not want

any other group to represent the National Party in Missis

sippi.72 They want their cake and they want to eat it,

too. They want the seats at the National Convention (so no

one else can have them and represent the National Party

back in Mississippi) and they want to be independent. They

are engaged in political preclusive buying—they are trying

to buy the seats at the Convention so the Freedom delegates

won’t get them, but they don’t want to pay for the seats

with loyalty to the National Party.

The Democratic Party has permitted this political double

dealing for two decades. After 20 years, the questions before

the Convention are becoming clear: Is the National Party

once again going to seat those who oppose it? Is it going to

seat the representatives of a recessed state convention that

72 On August 12, 1964, the “ traditional” Party obtained a tem

porary restraining order forbidding the Freedom Party from using

the word “ Democratic” in its name. This order is obviously a

nullity—no state can deny Negroes participation in its Democratic

Party and then bar them from forming a state group of their own

to represent the National Democratic Party in that state. More

significantly here, this is simply another device to keep the National

Party out of Mississippi.

35

will find a method of supporting Barry Goldwater on Sep

tember 9? Or is it, at long last, going to seat loyal Demo

crats ready and willing to support the National Party, its

candidates and its principles?

We turn now to the legal answers to these questions.*

* The above statement of facts has been reviewed for accuracy

by Barney Frank, Teaching Fellow in Government and General Edu

cation at Harvard University, who spent substantial time in Mis

sissippi collecting facts for the Freedom Party. Many others assisted

in providing the facts outlined above.

36

LEGAL ARGUMENTS FOR SEATING MISSISSIPPI

FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY

I

The Rules of the Convention Forbid the Seating of the

“ Traditional” Mississippi Democratic Party Delegation.

The 1956 and 1960 Democratic National Conventions

adopted the following rules :

“ (1) It is the understanding that a State Demo

cratic Party, in selecting and certifying delegates to

the Democratic National Convention, thereby under

takes to assure that voters in the State will have the

opportunity to cast their election ballots for the Pres

idential and Vice Presidential nominees selected by

said Convention, and for electors pledged formally

or in good conscience to the election of these Presi

dential and Vice Presidential nominees, under the

Democratic Party label and designation;

“ (2) It is understood that the Delegates to the

Democratic National Convention, when certified by the

State Democratic Party, are bona fide Democrats who

have the interests, welfare and success of the Demo

cratic Party at heart, and will participate in the Con

vention in good faith, and therefore no additional

assurances shall be required of Delegates to the Demo

cratic National Convention in the absence of cre

dentials contest or challenge. . .”

The Democratic National Committee has recommended

that the rules quoted above again “ be adopted as rules

applicable to the 1964 Democratic National Convention.”

In line with this recommendation, these rules are contained

in the Call for the 1964 Democratic National Convention

issued by Chairman John M. Bailey on February 26,

1964.73

These two rules, considered separately or considered

jointly, prevent the seating of the “ traditional” Missis

sippi Democratic Party. We deal with each paragraph

of the rules separately.

A. Paragraph (1) of the Rules Forbids the Seating of

the Delegation of the “ Traditional” Party Because