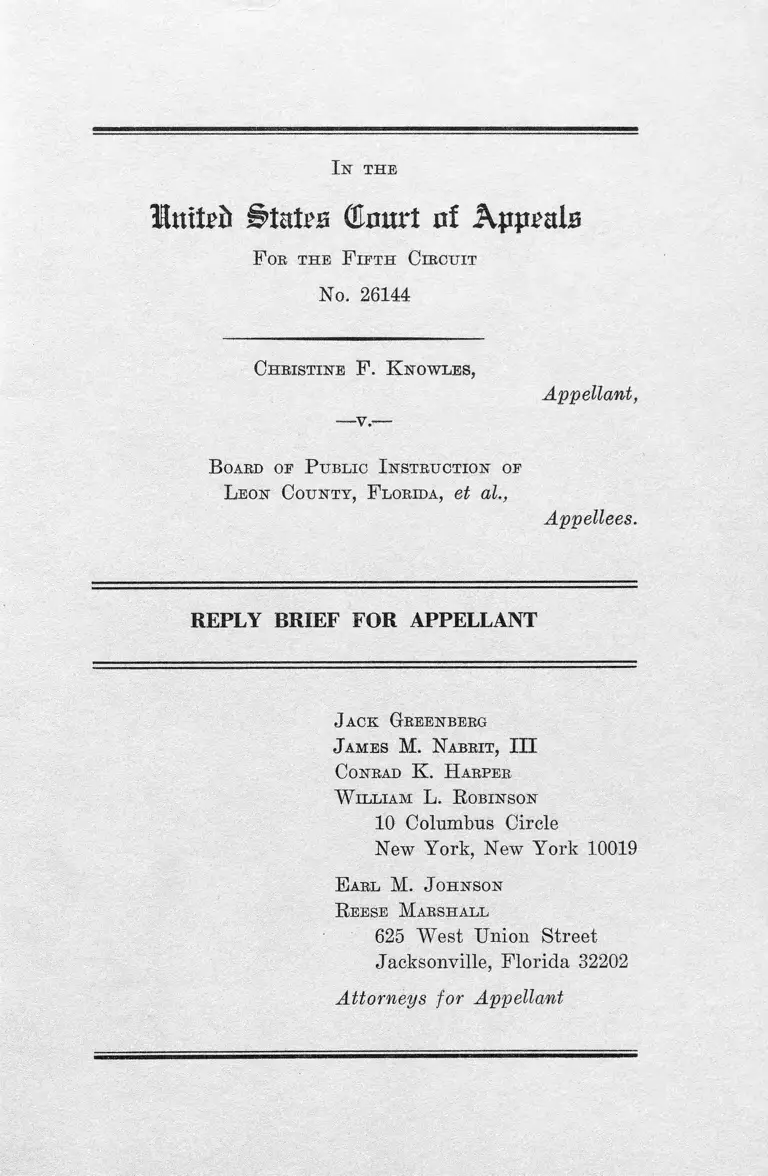

Knowles v. Board of Public Instruction of Leon County, FL Reply Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

October 28, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Knowles v. Board of Public Instruction of Leon County, FL Reply Brief for Appellant, 1968. 564a9329-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a858f076-72c1-47b0-8d4a-86917635cc88/knowles-v-board-of-public-instruction-of-leon-county-fl-reply-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

lotted States (Eourt of Appeals

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 26144

Christine F . K nowles,

B oard oe P ublic I nstruction of

L eon County, F lorida, et al.,

Appellant,

Appellees.

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Conrad K . H arper

W illiam L. R obinson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E arl M. Johnson

R eese Marshall

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

A rgument page

This Court has Jurisdiction to Determine Appel

lant’s Appeal from the District Court’s Order Dis

missing Appellant’s Complaint ............................... 1

Conclusion ........ ........... ............................ .............. .......... 7

Certificate of Service ......... ............................................. . 8

Table of A uthorities

Cases:

Atlantic Coastline R. Co. v. Mims, 199 F.2d 582 (5th

Cir. 1952) .................. ........................ ........................ . 6

Foman v. Davis, 371 U.S. 178 (1962) .............................. 4

Hoiness v. United States, 335 TT.S. 297 (1948) .............. . 3

State Farm, Mutual Automobile Ins. Co. v. Palmer,

225 F.2d 876 (9th Cir. 1955), rev’d per curiam 350

TT.S. 944 (1956) ......... .......... .............. ........................... 3,6

United States v. Arizona, 206 F.2d 159 (9th Cir.),

rev’d per curiam 346 TT.S. 907 (1953) ....................... 3

United States v. Stromberg, 227 F.2d 903 (5th Cir.

1955) ...................... 6

Woodham v. American Cystoscope Co., 335 F.2d 551

(5th Cir. 1964) .............. ........... .......... ........................... 6

Other A uthorities:

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 73(a) ....................... 2

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 73(b) .................. 4

I n t h e

In M (tart of A^prals

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 26144

Christine F . K nowles,

Appellant,

B oard op P ublic I nstruction of

L eon County, F lorida, et al.,

Appellees.

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

This brief is submitted on behalf of appellant in reply

to the brief submitted by appellees.

ARGUMENT

This Court has Jurisdiction to Determine Appellant’ s

Appeal from the District Court’s Order Dismissing Ap

pellant’s Complaint.

On February 28, 1968, the district court entered an order

rendering judgment for the defendants and dismissing

appellant’s complaint (R.192-193). Appellant filed a mo

tion for new trial on March 7, 1968 (R.193-195) which was

denied on March 8, 1968 (R.195). On April 8, 1968, ap

pellant filed a notice of appeal from the district court’s

order dated March 8, 1968 denying* appellant’s motion for

2

new trial (R.196). The text of the notice of appeal is

set out in the margin.1

Appellant’s notice of appeal was timely for appealing

the district court’s order of February 28, 1968 because

under the then applicable Federal Rules of Civil Proce

dure 73(a), appellant’s timely motion for new trial in

effect postponed the running of time for appeal until af

ter the order denying the motion for new trial. Rule 73(a)

provided in pertinent part that:

An appeal permitted by law from a district court to

a court of appeals shall be taken by filing a notice of

appeal with the district court within 30 days from the

entry of the judgment appealed from. . . . The run

ning of the time for appeal is terminated as to all

parties by a timely motion made by any party pursu

ant to any of the rules hereinafter enumerated, and

the full time for appeal fixed in this subdivision com

mences to run and is to be computed from the entry

of any of the following orders made upon a timely

motion under such rules: . . . denying a motion for

new trial under Rule 59.

1 Notice op Appeal

(Number and title omitted) (Filed: April 8, 1968)

Notice is hereby given that the plaintiff-intervenor in the above

styled cause, Christene Knowles, hereby appeals to the United

States Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit from the Order of

the Court made and entered on the 8th day of March, 1968, deny

ing Motion For New Trial.

Dated this 3rd day of April, 1968.

Johnson & Marshall

By s / Reese Marshall

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Leroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

3

Appellant’s notice of appeal was filed on April 8, 1968

within 30 days from the denial of her motion for new

trial on March 8, 1968.2

Appellant concedes the technical inaccuracy of her notice

of appeal, which specified the denial of her motion for new

trial as the judgment appealed from, instead of the order

dismissing her complaint. However, appellant submits that

her counsel’s oversight in drafting the notice of appeal

does not deprive this court of jurisdiction to determine

her appeal from the district court’s order dismissing her

complaint.

As is shown below, the Supreme Court has held that

the failure correctly to designate the judgment appealed

from in the notice of appeal does not deprive appellate

courts of jurisdiction to consider an appeal. State Farm

Mutual Automobile Ins. Co. v. Palmer, 225 F.2d 876 (9th

Cir. 1955), rev’d per curiam, 350 U.S. 944 (1956), decided

the precise'issue involved in the instant case and, there

fore, is binding on this court. In Palmer, the defendant

moved for a new trial after entry of judgment. His mo

tion for new trial was denied and he filed a notice of

appeal from the denial of the motion, identifying it by

date. The court of appeals dismissed the appeal holding

that the order appealed from was a non-appealable order

and the notice of appeal was not sufficient to give the

court jurisdiction over the judgment on the merits. The

Supreme Court summarily reversed citing Hoiness v.

United States, 335 U.S. 297 (1948). Accord, United States

v. Arizona, 206 F.2d 159 (9th Cir.), rev’d per curiam 346

U.S. 907 (1953).

Hoiness involved a district court which, on August 5,

1946, filed an order dismising a seaman’s libel action

2N.B. April 7, 1968 was a Sunday.

4

against the United States for lack of jurisdiction. On

October 14, 1946, the district court filed Findings of Fact

and Conclusions of Law and a decree. The seaman filed

a notice of appeal, timely as to either order, from the

order entered on October 14. The court of appeals dis

missed the appeal holding that the first order was the

final one and that the decree of October 14 was not ap

pealable. The Supreme Court reversed. Finding it un

necessary to determine which was the final order, the Court

concluded:

And although the petition for appeal referred solely

to the second order and not to the first, that defect

was of such a technical nature that the Court of Ap

peals should have disregarded it in accordance with

the policy expressed by Congress in Eev. Stat. §954.

28 USCA 1928 ed. §777, 8 FCA title 28, §777.

The mandate of that statute is for a court to dis

regard niceties of form and to give judgment as the

right of the cause shall appear to it. 335 U.S. at 300-

301 (footnotes omitted).

In Foman v. Davis, 371 U.S. 178 (1962), the Supreme

Court gave specific attention to the requirement of Rule

73(b) Fed. R. Civ. P., that the notice of appeal must

designate the judgment or part thereof appealed from.

In Foman, the district court dismissed the complaint on

December 19, 1960. On December 20, 1960, plaintiff filed

motions to vacate the judgment and to amend the com

plaint. January 17, 1961, plaintiff filed a notice of ap

peal from the judgment of December 19, 1960. January

23, 1961, the district court denied plaintiff’s motions to

vacate and amend. January 26, 1961, plaintiff filed a no

tice of appeal from the denial of the motions.

On appeal, the parties briefed and argued the merits of

the dismissal of the complaint and the denial of plaintiff’s

motions. The court of appeals, sua sponte, dismissed the

appeal insofar as taken from the judgment of December

19, 1960 as prematurely taken because of the pending mo

tions to vacate and amend. Treating the January 26, 1961

notice of appeal solely as an appeal of the denial of plain

tiff's motions, the. court of appeals affirmed the orders of

the district court entered January 23, 1961 on the ground

there was nothing in the record to show the circumstances

before the district court in ruling on the motions and

consequently no showing that the district court abused its

discretion.

The Supreme Court reversed this narrow reading of the

second notice of appeal holding that the court of appeals

should have treated the appeal from the denial of the

motions as an effective, although inept, attempt to appeal

from the judgment sought to be vacated.

The defect in the second notice of appeal did not mis

lead or prejudice the respondent. With both notices

of appeal before it (even granting the asserted ineffec

tiveness of the first), the Court o f Appeals should have

treated the appeal from the denial of the motions as

an effective, although inept, attempt to appeal from

the judgment sought to be vacated. Taking the two

notices and the appeal papers together, petitioner’s

intention to seek review of both the dismissal and the

denial of the motions was manifest. Not only did

both parties brief and argue the merits of the earlier

judgment on appeal, but petitioner’s statement of

points on which she intended to rely on appeal, sub

mitted to both respondent and the court pursuant , to

rule, similarly demonstrated the intent to challenge the

dismissal.

It is too late in the day and entirely contrary to the

spirit of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for

5

6

decisions on the merits to he avoided on the basis of

such mere technicalities. “The Federal Rules reject

the approach that pleading is a game of skill in which

one misstep by counsel may be decisive to the outcome

and accept the principle that the purpose of pleading

is to facilitate a proper decision on the merits.” Con

ley v. Gibson, 355 US 41, 48, 2 L ed 2d 80, 86, 78 S Ct

99. The Rules themselves provide that they are to

be construed “to secure the just, speedy, and inexpen

sive determination of every action.” Rule 1. 371 U.S.

at 181-182.

Consistent with the rulings of the Supreme Court, this

Court has uniformly held that errors in designating the

judgment appealed contained in a notice of appeal will not

deprive a party of its right of appeal. Atlantic Coastline

R. Co. v. Mims, 199 F.2d 582 (5th Cir. 1952); United States

v. Stromberg, 227 F.2d 903 (5th Cir. 1955); Woodham v.

American Cystoscope Co., 335 F.2d 551 (5th Cir. 1964).

Thus, it is now well settled that a mistake in designating

the judgment should not result in dismissal of the appeal

as long as the intent to appeal from a specific judgment

is clear from the record as a whole and the appellee is

not prejudiced by the mistake.

In the present case, the record shows appellant intended

to appeal from the judgment on the merits rendered Febru

ary 28, 1968. Both parties have prepared briefs on the

district court’s judgment and appellees’ do not assert they

were prejudiced or misled by appellant’s notice of appeal.

The teaching of Palmer and other cases cited and dis

cussed above is that appellant’s right to appeal is not

to be frustrated by formal errors in a notice of appeal

where, as here, no one has been misled.

7

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above and in appellant’s original

brief, this court should consider this appeal as being taken

from the district court’s judgment on the merits filed

February 28, 1968 and that judgment should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Conrad K. Harper

W illiam L. R obinson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E arl M. J ohnson

R eese Marshall

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Attorneys for Appellant

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that on the 28th day of October, 1968,

I served a copy of the foregoing Reply Brief for Appellant

upon C. Graham Carothers, Esq. of Aufley, Aufley, McMul

len, Michaels, McGehee & Carothers, P. 0. Box 391, Talla

hassee, Florida, by mailing a copy thereof to him at the

above address via United States mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellant

M E ilE N PRESS INC. — N. Y, C.<^§||!|^» 219