Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner, 1988. 6671d3d0-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a8c6a5a2-d122-4b0c-8daa-9d15abab7432/patterson-v-mclean-credit-union-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

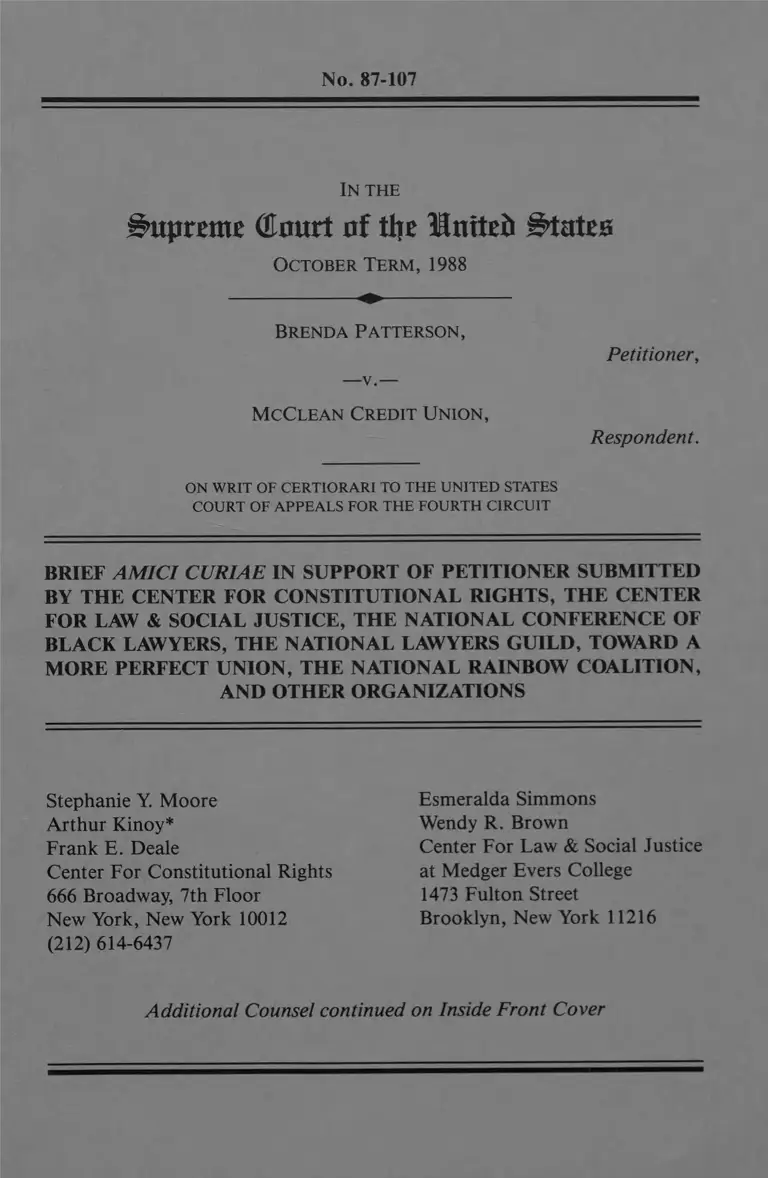

No. 87-107

In the

Supreme Court of tlie litmteft States

October Term, 1988

Brenda Patterson,

Petitioner,

McClean Credit Union,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF AM IC I CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER SUBMITTED

BY THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS, THE CENTER

FOR LAW & SOCIAL JUSTICE, THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF

BLACK LAWYERS, THE NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD, TOWARD A

MORE PERFECT UNION, THE NATIONAL RAINBOW COALITION,

AND OTHER ORGANIZATIONS

Stephanie Y. Moore

Arthur Kinoy*

Frank E. Deale

Center For Constitutional Rights

666 Broadway, 7th Floor

New York, New York 10012

(212) 614-6437

Esmeralda Simmons

Wendy R. Brown

Center For Law & Social Justice

at Medger Evers College

1473 Fulton Street

Brooklyn, New York 11216

Additional Counsel continued on Inside Front Cover

Wilhelm Joseph

National Conference of Black Lawyers

126 West 119th Street

New York, New York 10027

Haywood Burns

Steven Saltzman

National Lawyers Guild

55 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10013 *

Margery A. Greenberg

Toward A More Perfect Union

666 Broadway

New York, New York 10012

Jeanne Mallett

National Rainbow Coalition

Policy Committee

1055-H Neil Avenue

Columbus, Ohio 43201

Jeanne Mirer

* Counsel o f Record

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................... iii

CONSENT OF THE PARTIES.............. 1

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ............ 1

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .............. 1

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT . 2

ARGUMENT ............................. 6

I. THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE

UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION

PROSCRIBES PRIVATE

DISCRIMINATION ................ 6

A. The Legislative History of

the Thirteenth Amendment

Confirms Congress's

Overarching Intent to

Eradicate Slavery and its

Incidents ................ 6

B. The Precedents of This Court

Soundly Establish the Reach

of the Thirteenth Amendment

to Private Discriminatory

Conduct..................... 17

II. Runvon v. McCrary WAS PROPERLY

DECIDED AND A DECISION BY THIS

COURT TO OVERRULE Runyon WOULD

RETARD THE DEVELOPMENT OF THIS

NATION'S STRUGGLING COMMITMENT

TOWARDS A JUST AND EQUAL SOCIETY 29

A. Runvon IS CONSISTENT WITH THE

CONSTITUTIONAL MANDATE OF THE

THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT AS CONSTRUED

IN J o n e s .................. 29

B. RECONSIDERATION OF Runyon

SIGNALS A RETREAT FROM THE

FUNDAMENTAL PROTECTIONS AGAINST

INVIDIOUS RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

AND A REBURIAL OF THE WARTIME

AMENDMENTS................ 3 3

1. Section 1981 is

essential in providing

necessary remedies for

eliminating the

remaining badges and

indicia of slavery

banned by the

Thirteenth Amendment . 33

2. Overruling Runvon would

destroy the recent

expansion of the

protections of § 1981

to other oppressed

groups in American

society................ 3 9

- ii -

CONCLUSION . 43

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Brown v. Board of Education,

347 U.S. 483 (1954) ..........

Civil Rights Cases of 1883,

109 U.S. 3 (1883) ............

Fullilove v. Klutznick,

448 U.S. 448 (1980) ..........

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.,

482 U.S. ,107 S. Ct. 2617 (1987).... ........ 36

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc^,

421 U.S. 454

(1975) ....................... 30' 31' 35

Jones v. Alfred H. Maver Co

392 U.S. 409 (1968).............. passim

McCulloch v. Maryland.

17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316 (1819)........ 26

Patterson v. McClean Credit Union,

No. 87-107, slip op. (U.S. April 25, 1988) ....................... passim

Plessv v. Ferguson163 U.S. 537 (1896).......... 5, 21,

Regents of the Univ. of Calif._v_.— Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978) ..................

Runvon v. McCrary,

427 U.S. 160 (1976) . passim

iv

Saint Francis College v. Al-Khazraii

481 U.S. , 107 S. Ct. 2022 (1987)

39,

Shaare Tefila Congregation v. Cobb,

481 U.S. , 107 S. Ct. 2019 (1987)

39,

Scott v. Sandford

60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1856)

12,

Slaughterhouse Cases,

83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873) . . . 11, 18

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park.

396 U.S. 229 (1969)................... 30

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Ass'n.

410 U.S. 431 (1973)................... 30

United States v. Cruikshank.

25 F.Cas. 707 (No. 14,897)

(C.C.D. La. 1874)..................... 13

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber.

443 U.S. 193 (1979)................... 29

Vietnamese Fishermen's Ass'n v, Knights of

the Ku Klux Klan. 518 F. Supp. 993

(S.D. Tx. 1981)........................ 36

Williams v. City of New Orleans.

729 F. 2d 1554 (5th Cir. 1984)........ 28

Woods v. Miller Co..

333 U.S. 138 (1948) 32

v -

Constitutional Provisions:

U.S. Const., Amendment 13, § 1 (1865)................................... passim

Federal Statutes:

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 .................... passim

42 U.S.C. § 1982 .................... passjm

Congressional Documents:

Cong. Globe 38th Cong., 1st Sess. (1864) ......................................passim

Civil Rights Act of 1866 ............passim

Reports and Studies:

Kerner Commission Follow-Up Report,

reported in 2 Decades of Decline Chronicled

bv Kerner Follow-Up Report. N.Y. Times,

March 1, 1988 38

Report of the Commission on Minority

Participation in Education and American

Life, "One-Third of A Nation"

(1988).................................. 37

Books

Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick

Douglass 150 (1962) 34

Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished

Revolution,1863-1877 (1988)............ 4, 8, 37, 38

VI

Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom (1965)

......................................... 9

Higginbotham, In the Matter of Color (1st ed. 1978) .............................3

Williams, Eyes On The Prize: America's

Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965 (1987) . . 42

Articles

Buchanan, The Quest For Freedom: A Legal

History of the Thirteenth Amendment. 12

Hous. L. Rev. 1 (1974)

..................... 7, 17, 21, 26, 34

Comment, Developments in the Lav — Section

1981, 15 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 29,(1980)................................. ..

Larson, The Development of Section 1981 as

a Remedy for Racial Discrimination in

Private Employment. 7 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 56 (1972)...........................

Kennedy, Race and the Fourteenth Amendment

: The Power of Interpretational Choice, in

A Less Than Perfect Union 285 (J. Lobel ed. 1988)............................... 43

Kinoy, The Constitutional Right of Negro

Freedom Revisited: Some First Thoughts on

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Company. 22

Rutgers L. Rev. 537 (1969)............ 24

Kinoy, Jones v. Alfred H. Maver Co.: An

Historic Step Forward. 22 Vand. L. Rev. 475 (1969)................................... .

- vii

Kinoy, The Constitutional Right of Negro

Freedom. 21 Rutgers L. Rev. 387

(1967)............................. 3, 11

Kohl, The Civil Rights Act of 1866. Its

Hour Come Round At Last; Jones v. Alfred

Mayer Co., 55 Va. L. Rev. 272 (1969) . . 36

Note, Jones v. Maver: The Thirteenth

Amendment and the Federal Anti-

Discrimination Laws. 69 Colum. L. Rev. 1019

(1969)................................. 24

tenBroeck, Thirteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States:

Consummation to Abolition and Kev to the

Fourteenth Amendment. 39 Calif. L. Rev. 171

(1951).............................9, 15

Other Authorities

Brief Amicus Curiae of the American Civil

Liberties Union Foundation and the North

Carolina Civil Liberties Legal Foundation

in Support of Petitioner, Patterson v.

McClean Credit Union. No. 87-107 (U.S.

October Term, 1987).................. 35

CONSENT OF THE PARTIES

Amici Curiae file this brief with the

consent of both parties in support of the

position advanced by the Petitioner.

Letters of consent have been filed with the

Clerk of this Court.

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The thirty-nine organizations, groups,

and individuals joining in this brief amici

curiae (see appendix) represent many

segments of American society with diverse

interests. They share a mutual concern

that the Court will use the instant case to

reaffirm its and this nation's commitment

to rid our society of the haunting spectres

of racial discrimination and hatred.

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

On April 25, 1988, this Court restored

to the calendar for reargument the case of

Patterson v. McClean Credit Union. No. 87-

107. The Court asked that the parties

consider and brief the following question:

"Whether or not the

interpretation of 42 U.S.C. §

1981 adopted . . . in Runvon v.

McCrary. 427 U.S. 160 (1976),

should be reconsidered."

As originally briefed and argued,

2

Patterson involved the sole legal question

whether § 1981 encompassed a claim of

racial discrimination in the terms and

conditions of employment, including a claim

that the petitioner was harassed because of

her race. The holding of this Court in

Runvon — that § 1981 "reaches private

conduct," 427 U.S. at 173 — undergirds the

claim asserted in Patterson and is

essential to the protection of the freedoms

conferred by the thirteenth amendment and

by Congress through the Civil Rights Act of

1866. A decision to overrule that holding

would constitute a grave step backward in

the struggle for racial equality and would

disrupt the stability of cherished rights

long secured.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

From the original ratification of the

United States Constitution in 1787, to the

3

enactment of the thirteenth amendment in

1865, the "peculiar institution" of

American slavery has remained undefined by

the document that initially endorsed, or at

least tolerated its existence, and that

eventually eradicated it. Throughout

history, the inability and, perhaps,

unwillingness of those entrusted with the

interpretation of the legal pronouncements

abolishing that institution to honestly

assess both the nature of American slavery

and the meaning of its abolition have

unnecessarily and unjustly retarded the

growth of those fundamental freedoms

essential to a civilized society.1

1 See Kinoy, The Constitutional Right

of Negro Freedom. 21 Rutgers L. Rev. 387

(1967) ; cf. A. L. Higginbotham, In the

Matter of Color 6-7 (1st ed. 1978) ("[F]or

black Americans today . . . the early

failure of the nation's founders and their

constitutional heirs to share the legacy of

freedom with black Americans is at least

one factor in America's perpetual racial

4

Moreover, the mechanical interpretations in

the post-Reconstruction era2 of the Civil

War Amendments operated to undermine the

concepts of dignity and justice that have

been lauded as the true embodiment of the

Constitution.

What follows is amici's attempt to

persuade the Court not to recreate the

obstacles that resulted in the virtual

burial in the post-Reconstruction era of

the Civil War Amendments and legislation

enacted pursuant thereto. The central

thrust of our argument is that the

tensions."); Kinoy, Jones v. Alfred H.

Mayer Co.; An Historic Step Forward. 22

Vand. L. Rev. 475, 476-77 (1969) (same).

2 As noted historian, Eric Foner,

recently explained, "Reconstruction was not

merely a specific time period, but the

beginning of an extended historical

process: the adjustment of American society

to the end of slavery." E. Foner,

Reconstruction: America's Unfinished

Revolution, 1863-1877, at xxvii (1988).

5

thirteenth amendment unequivocally

authorizes Congressional regulation of

private discriminatory conduct. Such is

evidenced by the legislative debates on the

Amendment and, more recently, by this

Court's seminal decision in Jones v. Alfred

H. Maver Co.3 Moreover, those debates,

the reality of slavery and the national

commitment to eradicate its vestiges, all

indicate that the ground upon which members

of this Court have based reconsideration of

Runvon — "the difficulties posed by

petitioner's argument for a fundamental

extension of liability under 42 U.S.C. §

1981"4 — is infirm. Finally, lest we

return to the post-Reconstruction Plessy v.

3 392 U.S. 409 (1968).

4 Patterson v. McClean Credit Union,

No. 87-107, slip op. at 1 (U.S. April 25,

1988) (per curiam) (emphasis added).

6

Ferguson5 and Civil Rights Cases of 18836

era, amici urge this Court to reaffirm §

1981's reach to private discrimination and

to find that racial discrimination in the

terms and conditions of employment,

including racial harassment, states a

cognizable claim under § 1981.

ARGUMENT

I. THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE UNITED

STATES CONSTITUTION PROSCRIBES PRIVATE

DISCRIMINATION.

A. The Legislative History of the

Thirteenth Amendment Confirms Congress's

Overarching Intent to Eradicate Slavery and

its Incidents___________________

The thirteenth amendment7 to the United

5 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

6 109 U.S. 3 (1883).

7 Section one of the Thirteenth

Amendment provides that "[n]either slavery

nor involuntary servitude . . . shall exist

within the United States, or any place

7

States Constitution, abolishing slavery and

securing universal freedom, was enacted in

1865 amid sectional strife and socio

political controversy.8 The issuance of

the Emancipation Proclamation three years

prior was deemed by many an inadequate

measure to secure the freedom of the Black

race.9 The geographical and political

subject to their jurisdiction." U.S.

Const., Amendment 13, § 1 (1865). Section

two confers upon Congress the "power to

enforce this article by appropriate

legislation." Id. at § 2.

8 Debates around the Thirteenth

Amendment commenced in the spring of 1864

just prior to the official end of the Civil

War.

9 See. e.q.. Cong. Globe 38th Cong.,

1st Sess. 1314 (1864) (Remarks of Senator

Trumbull [R., 111.]) (". . . any and all

these laws and proclamations, giving to

each the largest effect claimed by its

friends, are ineffectual to the destruction

of slavery"); id. at 1324 (Remarks of

Senator Wilson [R., Mass.]) (noting that

notwithstanding the Emancipation

Proclamation, the thirteenth amendment was

necessary to "make impossible forevermore

the reappearing of the discarded slave

8

limitations of President Lincoln's

manumission fell far short of the needed

destruction of the entire system of chattel

slavery. Recognizing that "none of the

acts hostile to slavery . . . [at the time

of the debates] ha[d] gone beyond the fact

of making men affected by them free; that

no one of them . . . reached the root of

slavery and prepared for the destruction of

the system,"10 Representative Wilson, on

the floor of the House of Representatives,

implored his colleagues to "assert the

ultimate triumph of liberty over slavery,

system, and the returning of the despotism

of the slavemasters' domination."). See

also Buchanan, The Quest For Freedom: A

Legal History of the Thirteenth Amendment.

12 Hous. L. Rev. 1, 7 (1974).

Indeed, well before 1863 it was

generally conceded, even by proslavery

forces, that "the disintegration of slavery

had begun." E. Foner, supra note 2, at 3,

8.

10 Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess.

1203 (1864).

9

democracy over aristocracy, free government

over absolutism,"11 by passing the

thirteenth amendment.

The concern for the plight of all

Blacks — whether slaves in the South or

free in the North — was paramount to

antislavery forces within the Congress.

The horrors of the "hapless bondsman"12

were universally known. Abolitionist

Congressmen also knew, however, that the

freedman of the North "was only less

degraded, spurned, and restricted than his

enslaved fellow. He bore all the burdens,

badges and indicia of slavery save only the

technical one."13 Thus, according to its

11 Id. at 1204.

12 Id. at 1324.

13 tenBroek, Thirteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States;

Consummation to Abolition and Key to the

Fourteenth Amendment. 39 Calif. L. Rev.

171, 179 (1951). For a discussion of the

10

strongest proponents, the thirteenth

amendment was necessary to ensure enduring,

universal freedom and to create a

fundamental, national right to liberty,

eguality, and dignity for all.

Congress did not confine its vision of

universal freedom to members of the Black

race; it was to extend to all of humanity

within the jurisdiction of the United

status of Blacks in the antebellum North,

see J. Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom

151-64 (1965) . In addition to the concern

for the liberties of the freedman, the

relationship of the federal government to

the states was a major theme discussed

during the debates. See id. at 174-77.

Opponents to the thirteenth amendment

argued that the sovereignty of the states

was sacrosanct and that the Amendment

proposed "a revolutionary change in the

Government" that "essentially repudiate[d]

the principle upon which the Union was

formed." Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess.

2986 (1864) (Remarks of Representative Kelley [R., Pa]).

11

States.14 In an effort to define this new

humanity for future generations, Congress

turned to the inhumanity perpetrated

against the slaves for over two hundred

years and pledged that never again would

any group or individual be subject to such

inhumane treatment within the jurisdiction

of the Constitution.

Central to the concept of freedom

envisoned by antislavery members of the

38th Congress was the "obliterat[ion of]

the last lingering vestiges of the slave

system." (Remarks of Representative Wilson,

14 See Kinoy, supra note 1, 21 Rutgers

L. Rev. at 389-90. See also The Civil

Rights Cases of 1883, 109 U.S. at 37

(Harlan, J., dissenting) ("The terms of the

thirteenth amendment are absolute and

universal. They embrace every race which

then was, or might thereafter be, within

the United States."); Slaughterhouse Cases.

83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36, 72 (1873)

("Undoubtedly while negro slavery alone was

in the mind of the Congress which proposed

the thirteenth article, it forbids any

other kind of slavery, now or hereafter.").

12

[R. , 111.]). In turn, at the heart of the

obliteration of the vestiges of slavery

was, at a minimimum, the total renunciation

of the notorious opinion of Chief Justice

Roger Taney in Dred Scott v. Sandford15 in

which Taney declared:

at the time of the Declaration of

Independence, and when the

Constitution of the United States

was framed and adopted . . . [the

black race were] regarded as beings

of an inferior order; and

altogether unfit to associate with

the white race, either in social or

political relations; and so far

inferior, thay they had no rights

which the white man was bound to

respect.16

The goal of Congress to overrule Dred

15 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1856). For

reference to the attempt of rebel states to

"promulgate the Dred Scott decision," see,

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. 1324

(1864) (Remarks of Senator Wilson [R.,

111.]). Senator Wilson challenged "anti

slavery men of united America . . . [to]

seize the first, the last, and every

occasion to trample down and stamp out

every vestige of slavery." Id. at 1324.

16 60 U.S. at 407.

13

Scott with the enactment of the thirteenth

amendment is manifested both by specific

reference to the decision and by forceful

expressions to restore the authority and

integrity of the Constitution.17 Senator

Trumbull and Representative Wilson

charitably described the framers of the

Constitution as men of good will who

uniformly deplored the horrors of slavery. 18

17 See also Civil Rights Cases of

1883. 109 U.S. at 37 (Harlan, J. ,

dissenting) (noting that the Civil Rights

Act of 1866, enacted pursuant to the

thirteenth amendment and prior to the

adoption of the fourteenth, conferred

national citizenship upon the Black race);

United States v. Cruikshank. 25 F.Cas. 707,

711 (No. 14,897) (C.C.D. La. 1874)

(discussing the necessity of the

legislative reversal of Dred Scott

decision) (Bradley, J.), aff1d . 92 U.S. 542

(1875) .

•̂8 Representative Wilson maintained

that the framers "believed in the

incompatibility of slavery with a free

Government; but they regarded the latter to

be the stronger, not yet having had the

experience with slavery as a political

power." Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess.

14

Under this view, the framers "looked

forward to the not distant, nor as they

supposed uncertain period when slavery

should be abolished, and the Government

become in fact, what they made it in name,

one securing the blessings of liberty to

all.Il19 Restoration of the mandates of the

1200 (1864). Similarly, Senator Trumbull

declared:

Our fathers who made the

Constitution regarded [slavery] . .

. as an evil, and looked forward

to its early extinction. They felt

the inconsistency of their

position, while proclaiming the

equal rights of all to life,

liberty, and happiness, they denied

liberty, happiness, and life itself

to a whole race, except in

subordination to them.

Id. at 1313. 19

19 Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess.

1313 (1864) (Remarks of Senator Trumbull

[R., 111.]) (emphasis added).

15

Constitution could be achieved only by

extending its protections and guarantees as

originally conceived to the Black race.20

Thus, the thirteenth amendment was

intended to effect not only the immediate

emancipation of the slaves, but the

liberation of the nation. The passage of

the Amendment conferred upon Congress a

"constitutional mandate to enforce . . .

not just the liberty of blacks but the

liberty of the whites as well and included

not just freedom from personal bondage but

20 As expressed by Senator Charles

Sumner:

It is only necessary to carry the

Republic back to its baptismal

vows, and the declared sentiments

of its origin. There is the

Declaration of Independence: let

its solemn promises be redeemed.

There is the Constitution: let it

speak, according to the promises of

the Declaration.

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess. 1482

(1864) .

16

protection in a wide range of natural and

constitutional rights."21

That the intent of the thirteenth

amendment was to reach private conduct

cannot be denied. As poignantly stated by

Representative Wilson:

Slavery is defined to be "the state

of entire subjugation of one person

to the will of another." This is

despotism, pure and simple. It is

true that this definition concerns

more the relations existing between

master and slave than it does those

between the system of slavery and

the government. But we need not

hope to find a system purely

despotic acting in harmony with a

Government wholly, or even

partially, republican. An

antagonism exists between the two

which can never be reconciled.22

To be certain, support for broad

legislative authority to effectuate the

21 tenBroek, supra note 12, at 183.

22 Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess.

1200 (1864) (Remarks of Rep. Wilson [R.,

Iowa]) (emphasis added).

17

mandate of universal freedom was not

unanimous.23 The 38th Congress, however,

well aware of the various interpretations

urged by opponents and proponents alike,

nonetheless enacted the thirteenth

amendment. Neither subsequent doubts,

ambivalence, nor actual regret by a handful

of Congressmen with respect to the

potential breadth of the thirteenth

amendment as enacted operates to eviscerate

the freedoms embodied therein at its

inception.

B. The Precedents of This Court Soundly

Establish the Reach of the Thirteenth

Amendment to Private Discriminatory Conduct

As early as 1873,24 judicial

23 Nor has any legislative measure,

amici will venture to assert, ever garnered

either the unanimous consent or

understanding of its terms and effects from

both Houses of Congress.

24 The first judicial encounters with

the thirteenth amendment after its

ratification in 1865 were generally by

18

interpretations of the thirteenth amendment

in this Court reaffirmed the sentiment of

the Reconstruction Congress by recognizing

the amendment as a "grand yet simple

declaration of personal freedom of all the

human race within the jurisdiction of this

government . . . ."25 Ten years iater, in

the Civil Rights Cases of 1883. this Court

noted that the scope of the thirteenth

amendment was not restricted to the mere

emancipation of the slaves. "By its own

unaided force and effect it abolished

Supreme Court justices on circuit duty in

the lower federal courts. At least one

commentator has concluded that "most of the

circuit decisions by Supreme Court justices

gave expansive readings to the thirteenth

amendment . . . ." Buchanan, supra note 9,

12 Hous. L. Rev. at 358. Although none of

those decisions were ever adopted by a

majority of the Court, see id.. they

provide some indication of a broader view

of the amendment shortly after its

ratification. 25

25 Slaughterhouse Cases. 83 U.S.(16 Wall.) 36, 69 (1873).

19

slavery, and established universal

freedom."26 Under the thirteenth

amendment, Congress was authorized to pass

legislation "so far as necessary or proper

to eradicate all forms and incidents of

slavery and involuntary servitude . . . [;

legislation that could] be direct and

primary, operating upon the acts of

individuals, whether sanctioned by state

legislation or not."27

Thus, although the power of Congress to

enact legislation to enforce the thirteenth

amendment was clear, the historic debate in

the Civil Rights Cases of 1883 concerned

the scope of that power in terms of

defining the badges and incidents of

slavery. While Justice Bradley, for the

majority, expressed a restrictive view of

26 109 U.S. at 20.

27 Id. (emphasis added).

20

Congress's power, the first Justice Harlan,

in dissent, urged a more expansive reading:

[S]ince slavery, as the court has

repeatedly declared was the moving

or principal cause of the adoption

of [the thirteenth] amendment and

since that institution rested

wholly upon the inferiority, as a

race, of those held in bondage,

their freedom necessarily involved

immunity from; and protection

against, all discrimination against

them because of their race; in

respect of such civil rights as

belong to freemen of other races.28

Against this background, Justice Harlan

concluded that discrimination against

Blacks solely on account of race imposed a

badge of servitude in conflict with the

universal freedom guaranteed by the

thirteenth amendment.29

After the decision in the Civil Rights

28 109 U.S. at 40 (Harlan, J.,

dissenting).

29 Id.

21

Cases of 188330. the thirteenth amendment

was, in effect, abandoned as a

constitutional mandate.31 Eighty-five

30 Although the Court in the Civil

Rights Cases unanimously recognized the

power of Congress to define and legislate

against badges and incidents of slavery,

see 109 U.S. at 35 (Harlan, J.,

dissenting), a majority rejected Congress's

attempt to exercise its power through

legislation proscribing racial

discrimination in public accomodations and

amusements. Thus, while the Court adopted

a broad theoretical view of Congressional

power under the amendment, it in fact

undermined that power by narrowly

interpreting "badges and incidents of

slavery" to exclude racial discrimination

and segregation. Id. at 22-24.

31 For a collection of cases in which

the Thirteenth Amendment was narrowly

construed, if applied at all, see Buchanan,

supra note 9, 12 Hous. L. Rev. at 593-97.

The pinnacle of judicial repression of

the Thirteenth Amendment and the attendant

emasculation of the freedoms secured

thereby came in the 1896 decision in Plessv

v. Ferguson. 163 U.S. 537 (1896). Finding

the inapplicability of the Thirteenth

Amendment to segregation legislation "too

clear for argument," the Plessv Court

observed that while "[sjlavery implies

involuntary servitude, — a state of

bondage[,] . . . [a] statute [requiring

22

years later, the first Justice Harlan's

dissenting opinion in the Civil Rights

Cases of 1883 was reasserted in force in

this Court's opinion in Jones v. Alfred H.

Maver Co.. supra. In Jones this Court

resurrected the thirteenth amendment and

reaffirmed Congressional power to enact

legislation to enforce its goals. At issue

in Jones was the refusal by private

individuals to sell a home to the Joneses

solely because they were Black. Writing

for the Court,32 Justice Stewart found that

the language of the statute "[o]n its face"

prohibited all racial discrimination in the

sale or rental of property.33 Examining

separate but equal accomodations] has no

tendency to destroy the legal equality of

the two races, or reestablish a state of

involuntary servitude." Id. at 542.

32 Only two justices dissented from

the decision in Jones.

33 392 U.S at 421.

23

the origins of 42 U.S.C. § 1982, which also

grew out of the Civil Rights Act of 1866,

the Court next conducted an exhaustive

review of the legislative history and found

clear confirmation of its reading of the

statute.34 Rejecting the argument that

Congress sought only to eliminate

discriminatory laws, Justice Stewart

concluded that Congress plainly intended

"to secure . . . [the] right[s protected by

§ 1982] against interference from any

source whatever, whether governmental or

private."35 Looking then to the

constitutional authority for such

legislation the Court held that "Congress

has the power under the thirteenth

amendment rationally to determine what are

the badges and the incidents of slavery,

34 Id. at 422-37.

35 Id. at 424.

24

and the authority to translate that

determination into effective

legislation.1,36

The Jones Court's conclusions, both

statutory and constitutional, were

undoubtedly prudent, fair and right.37

36 Id. at 440.

37 The Civil Rights Cases of 1883

unanimously and unambiguously established

the authority of Congress under the

thirteenth amendment to enact direct and

primary legislation reaching the

discriminatory conduct of private actors.

See 109 U.S. at 30, 39. The Jones Court

properly concluded that § 1982 was an

appropriate exercise of that authority to

eradicate the badges and incidents of slavery.

The magnitude of the Jones Court's

resurrection of the thirteenth amendment

cannot be diminished. One commentator has

accurately described Jones as "[r]ivaling

Brown [v. Board of Educ.. 347 U.S. 483

(1954)] in historical import . . . ."

Note, Jones v. Mayer; The Thirteenth

Amendment and the Federal Anti-

Discrimination Laws. 69 Colum. L. Rev. 1019

(1969). See generally Kinoy, The

Constitutional Right of Nearo Freedom

Revisited: Some First Thoughts on Jones v.

Alfred H. Mayer Company. 22 Rutgers L. Rev. 537, 539-43 (1968).

25

The dissent's recital of contrary-

legislative intent38 suggests, at best,

spirited debate around an important piece

of legislation. Indeed, the second Justice

Harlan's assertion that a reading of the

legislative history of the Civil Rights Act

of 1866 demonstrates that "a contrary

conclusion may equally well be drawn,"39 is

hardly a riveting indictment of the Court's

reasoning. Even if one assumes that

Congress's intent was hopelessly ambiguous,

it does not follow that the Court's

interpretation of § 1982 is either

unsupported or insupportable.

The Jones Court legitimately construed

38 The central thrust of the Jones

dissent is that the Civil Rights Act of

1866, from which § 1982 emanates, was

designed to remove only legal disabilities

in the sale or rental of property. See 392

U.S. at 452-54 (Harlan, J., dissenting).

39 Jones. 392 U.S. at 455 (Harlan, J.,

dissenting) (emphasis added).

26

§ 1982's provisions to reach "modern

manifestations of racial discrimination,1,40

and thus to effectuate the clear purposes

of the Amendment under which it was

promulgated. To have done otherwise would

have deprived the statute "of all

functional utility in today's society.

Unless a statute's language and legislative

history plainly require it, [however, it] .

. . should not be construed into practical

impotence."40 41 The majority approach in

Jones reflects the fundamental and historic

understanding of this Court as expressed by

Chief Justice John Marshall in McCulloch v.

Maryland42. that "[the] constitution [is]

intended to endure for ages to come, and,

40 Buchanan, supra note 9, 12 Hous. L.

Rev. at 848.

41 Id.

42 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316 (1819).

27

consequently, to be adapted to the various

crises of human affairs."43

With respect to Jones's constitutional

conclusion, it was both static and dynamic:

Jones merely restates what even the

majority of the Court in the Civil Rights

Cases of 1883 was required to concede —

that Congress was empowered by the

thirteenth amendment to enact legislation

to eradicate the lingering badges and

incidents of slavery, whether publicly or

privately imposed. But Jones also

represents an approval of broad

Congressional definitions of the badges and

incidents of slavery.44

43 Id. at 415.

44 Under Jones the authority of

Congress to define badges and incidents of

slavery is not boundless. Congress is

constrained to rationally link its

definition to the concept of slavery. In

Jones. the Court recognized the historical

link to slavery in a long chain of racial

28

This Court must be guided in the

instant case by the Jones majority's

interpretation of Congressional power which

is consistent with both a serious

commitment to equality and with this

Court's repeated acknowledgment that

America remains "a Nation confronting a

legacy of slavery and racial

discrimination," seeking to overcome "a

lengthy and tragic history" of societal,

racial discrimination arising out of

slavery.45

discrimination in the sale and rental of

property: "Just as the Black Codes, enacted

after the Civil War to restrict the free

exercise of [the right to acquire

property], were substitutes for the slave

system, so the exclusion of Negroes from

white communities became a substitute for

the Black Codes." 392 U.S. at 441-42.

45 Regents of the Univ. of Calif, v.

Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 294, 303 (1978)

(Opinion of Powell, J.). See also Williams

v. City of New Orleans. 729 F.2d 1554,

1570-80 (5th Cir. 1984) (Wisdom, J.,

concurring in part, dissenting in part)

29

II. Runyon v. McCrary WAS PROPERLY DECIDED

AND A DECISION BY THIS COURT TO OVERRULE

Runyon WOULD RETARD THE DEVELOPMENT OF THIS

NATION'S STRUGGLING COMMITMENT TOWARDS A

JUST AND EQUAL SOCIETY.

A. Runvon IS CONSISTENT WITH THE

CONSTITUTIONAL MANDATE OF THE THIRTEENTH

AMENDMENT AS CONSTRUED IN Jones_________

Just a little over a decade ago, this

Court, in a decisive 7-2 opinion, held that

42 U.S.C. § 1981 prohibits private

discrimination in the making and

enforcement of contracts. The legislative

history of that Act, as powerfully and more

(chronicling the "effects of generations of

past discrimination against blacks as a

group" and the relationship of those

effects to thirteenth amendment).

In addition, this Court's affirmative

action decisions attest to the lingering

effects in contemporary society of concepts

of racial inferiority born and bred of

slavery. See, e.g.. Fullilove v.

Klutznick. 448 U.S. 448, 463 (1980) (noting

"ongoing efforts directed toward

deliverance of the century-old promise of

equality of economic opportunity"); United

Steelworkers of America v. Weber. 443 U.S.

193, 204 (1979) (recognizing the "centuries

of racial injustice").

30

fully presented by petitioners herein,46

demonstrates the soundness of the Runvon

decision.

In addition, the interpretation of

§ 1981 in Runvon "follows inexorably from

the language of that statute, as construed

in Jones. Tillman fv. Wheaton-Haven

Recreation Ass'n. 410 U.S. 431 (1973)], and

Johnson fv. Railway Express Agency, Inc. .

421 U.S. 454 (1975)]."47 That Runvon was

46 See generally Brief of Petitioner

on Reargument.

47 In Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park.

396 U.S. 229 (1969), this Court extended

the reasoning of Jones to sustain a claim

of racial discrimination under § 1982 for

the refusal of a nonstock corporation

organized to provide various amenities to

the Hunting Park community to recognize a

lease assignment to a Black person.

Subsequently, in Tillman, the Court

essentially reaffirmed Sullivan and

rejected the argument that Wheaton-Haven

was a "private club" and thus immune from

suit under §§ 1981, 1982, and 2000a. In a

note, the Court suggested that § 18 of the

1870 Enforcement Act preserved the

thirteenth amendment foundation of § 1981

31

properly decided is evidenced by the

strength of Jones. the clarity of the

intent of Congress in proposing and

adopting the thirteenth amendment, and the

legislative history of the Civil Rights Act

of 1866.48

The dissent in Runyon. much like that

in Jones. merely offers a competing

interpretation of the congressional debates

surrounding passage of Reconstruction

legislation. To the extent that such

interpretations are credible, they must be

read in the context of the political,

after the statute was reenacted following

the adoption of the fourteenth amendment.

Id. at

In Johnson v. Railway Express Agency,

the Court joined in the settled conviction

among the Federal Courts of Appeal "that §

1981 affords a federal remedy against

discrimination in private employment on the

basis of race." 421 U.S. at 460.

48 See generally Brief of Petitioner

on Reargument.

32

social and economic disarray that generally

characterized the period. Notwithstanding

any resultant procedural infirmities or

ambiguities in the passage of various

legislation, the substantive intent of

Congress was clear -- to become a more

perfect union, the institution of slavery

had to be eliminated, root and branch.

Particularly under such circumstances,

neither the constitutionality nor the

purpose of legislative action taken by

Congress should "depend [entirely] on

recitals of the power under which it

undertakes to exercise."49 A belated

shift in emphasis on the various

pronouncements in Congress will

unnecessarily strip away "an important part

49 Woods v. Miller Co.. 144 (1948) . 333 U.S. 138,

33

of the fabric of our law."50 This Court

must not pervert the clear substantive

intent of the Reconstruction Congress by

minimizing the magnitude and

comprehensiveness of the evil it sought to

exorcise from this nation, and which

persists in society today.

B. RECONSIDERATION OF Runyon SIGNALS A

RETREAT FROM THE FUNDAMENTAL PROTECTIONS

AGAINST INVIDIOUS RACIAL DISCRIMINATION AND

A REBURIAL OF THE WARTIME AMENDMENTS._____

1. Section 1981 is essential in

providing necessary remedies for

eliminating the remaining badges

and indicia of slavery banned by

the Thirteenth Amendment.

Overruling Runvon and thereby burying

§ 1981 would be simply disasterous,

particularly for Black Americans who were

specifically intended to benefit from the

statute. Despite the gains achieved during

the modern civil rights era, Black

50 Runvon. 427 U.S. at 190 (Stevens,

J., concurring).

34

Americans have never fully recovered from

the ordeal of slavery. The nexus between

slavery and contemporary racial

discrimination extends beyond tangible

injuries and cannot be denied:

Slavery brutalized human dignity.

In modern America, acts motivated

by arbitrary prejudice continue to

inflict the wounds that were

institutionalized under slavery.

When arbitrary prejudice blocks a

person's opportunity to discharge a

function, human dignity suffers

deeply and in a measure that

escapes precise calculation. This

human hurt was one of the tragic

products of slavery; this same hurt

remains a tragic product of

arbitrary prejudice in today'ssociety.

Since the revitalization of the concept of

badges and indicia of slavery less than

twenty years ago in Jones. courts have

continued to recognize that a deprivation

based solely on the color of a person's 51

51 Buchanan, supra note 9, at 1073.

Accord F. Douglass, Life and Times of

Frederick Douglass 150 (1962).

35

skin causes a severe injury compensable by

an award of damages.52

In the context of employment, § 1981

offers a critically important remedy to

victims of racial discrimination.53 The

right of the newly emancipated slaves to

obtain gainful employment and to be secure

in the workplace were central ingredients

of the freedom guaranteed by the thirteenth

52 See generally Comment, Developments

in the Law — Section 1981. 15 Harv. C.R.-

C.L. L. Rev. 29, 223 - 24 & n.29 (1980); E.

R. Larson, The Development of Section 1981

as a Remedy for Racial Discrimination in

Private Employment. 7 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L.

Rev. 56, 99 (1972).

53 In Johnson v. Railway Express

Agency. 421 U.S. 454 (1975), this Court

concluded that "the remedies available

under Title VII and under § 1981, although

related, and although directed to most of

the same ends are separate, distinct, and

independent." Id. at 461. See also Brief

Amicus Curiae of the American Civil

Liberties Union Foundation and the North

Carolina Civil Liberties Legal Foundation

In Support of Petitioner at 14-20,

Patterson v. McClean Credit Union. No. 87-

107 (U.S. October Term, 1987).

36

amendment and protected by the Civil Rights

Act of 1866.54

[F]reedom meant more than simply

receiving wages. Freedmen wished

to take control of the conditions

under which they labored, free

themselves from subordination to

white authority, and carve out the

greatest measure of economic

54 The Reconstruction Congress heard

testimony that indicated that "the Black

Codes told only part of the story, and a

very small part at that. At the same time

that the South was removing the Negro's

legal disabilities from its statute books,

it was covertly attempting to reintroduce a

new, privately enforced slave system."

Kohl, The Civil Rights Act of 1866. Its

Hour Come Round At Last; Jones v. Alfred

Mayer Co.. 55 Va. L. Rev. 272, 279-80

(1969). See also Goodman v. Lukens Steel

Co-. 482 U.S. ___, 107 S. Ct. 2617, 2627-28

("the legislature's central concerns in

1866 revolved around actions taken by the

States and by private parties which

consigned black Americans to lives of

perpetual economic subservience to their

former masters") (second emphasis

supplied); Vietnamese Fishermen's Ass'n v.

Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. 518 F. Supp.

993, 1008 (S.D. Tx. 1981) ("Section 1981

protects a panoply of individual rights the

primary one being the right to contract to earn a living.").

37

autonomy.55

The historical interference with the

right of Black Americans to work for wages

is a long and well documented one. The

continuing impact of such interference

cannot be understated. A recent report by

the Commission on Minority Participation in

Education and American Life, "One-Third of

a Nation," concluded that "America is

moving backward — not forward — in its

efforts to achieve the full participation

of minority citizens in the life and

prosperity of the nation." Noting steady

and widening gaps between the minority and

majority populations in "education,

employment, income, health, and other basic

measures of individual and social well

being," the report predicts grave

consequences with respect to the social

55 E. Foner, supra note 2, at 102-03.

38

harmony and security of this nation.56

Thus, now, as during the post-

Reconstruction period as recognized by

noted historian Eric Foner:

the fulfillment of blacks'

"noneconomic" aspirations, from

family autonomy to the creation of

schools and churches, all depend[ ]

in considerable measure on success

in winning control of their working

lives and gaining access to . . .

economic resources . . . . 57

Remedies for interferences with the

right to contract for employment must be as

varied and comprehensive as the injuries.

Section 1981 entitles a successful claimant

to both equitable and legal relief,

including compensatory and, under certain

56 Cf. Kerner Commission Report; 2

Decades of Decline Chronicled by Kerner

Follow-Up Report. N.Y. Times, March 1,

1988, National News page (noting a

'persistent, large and growing American

economic underclass').

57 E. Foner, supra note 2, at 110.

39

circumstances, punitive damages.58 Both as

a compensatory and deterrent measure in the

struggle for racial equality, § 1981 is an

indispensible remedy and is necessary if

the "badges and indicia of slavery" are

ever to be eradicated from this society.

2. Overruling Runvon would destroy

the recent expansion of the

protections of § 1981 to other

oppressed groups in American

society.

Just last term, in Saint Francis

College v. Al-Khazraii59. this Court

unanimously broadened the scope of § 1981

by extending its protections against racial

discrimination to persons of Arabian

ancestry.60 There, after announcing the

58 See Johnson. 421 U.S. at 453.

59 481 U.S. ___ , 107 S. Ct. 2022 (1987)

60 In a related case, the Court

similarly held that 42 U.S.C. § 1982

encompasses a claim of racial discrimation

by Jews. Shaare Tefila Congregation v.

Cobb. 481 U.S.___ , 107 S. Ct. 2019 (1987).

40

applicability of the fundamental

propositions set forth in Runvon. the Court

noted that "[t]here is no disagreement

among the parties on these propositions,"

107 S. Ct. at 2026, and proceeded to

address the issue presented. It is indeed

ironic that after such explicit

acknowledgment of the vitality of the

Runvon holding in Al-Khazraii. and with

similar acquiescence, if not consent, to

the Runvon holding by the parties in

Patterson, that some members of the Court

find its application troublesome. The

clear effect of a decision now to undercut

the very basis of not only the Court's

decisions last term, but the many judicial

decisions which squarely rely upon Runvon.

would be to wind the clock backward,

permitting widespread discrimination to

fester.

41

Only thirty-four years ago, this Court

rendered its most significant decision in

the area of race relations. Brown v . Board

of Educ..61 marked the beginning of a

national committment to genuinely address

the issue of racism, its origins and

effects. By rejecting the notion, first

endorsed by this Court in Plessv v.

Ferguson62, that the doctrine of 'separate

but equal' was a desirable and

constitutional model of conduct, Brown

began a revolution in American racial

thinking. Post-Brown years witnessed the

intense, and oft-times turbulent, struggle

of American citizens — Black and white —

to overcome historically entrenched

stereotypical, racial attitudes that

61 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

62 163 U.S.537 (1896). See also supra

note 31 (discussing the implications of

Plessv^.

42

continue to plague us today.63 During

those years, the concerted efforts of the

national government — legislative,

executive, and judicial — aided

significantly to the transitional efforts

of the era.

As evidenced by the Court's decisions

in Shaare Teflia and Al-Khazrai i. rather

than evolving into a more tolerant society,

we have become a nation rife with

prejudices. The proliferation of new hate

groups — e.g., the Skinheads, the Dot-

Bashers — and the cancerous persistence of

the old — e.g., the Ku Klux Klan, further

signifies a nation in perpetual turmoil.64

63 For a detailed account of the post-

Brown struggles, see, J. Williams, Eyes On

The Prize: America's Civil Rights Years, 1954-1965 (1987).

64 Non-violent acts of racism, such as

those inflicted upon petitioner, Brenda

Patterson, are no less indicative of a

nation in which racism is unwilling to die.

43

Section 1981 is a key legislative mandate

designed to deter and inevitably eliminate

racial discord.

Runyon v . McCrary represents sage

social policy and sound legal judgment.

Its underlying propositions must not be

disturbed. " [Protection against racial

abuse by the state is significantly

diminished if the same results can be

accomplished by private parties."65 Thus,

if the intent of the Reconstruction

Congress in adopting the Wartime Amendments

and in enacting legislation thereto is not

to be reduced to a 'mere paper

Indeed, they are probably more common of

the discriminations that reinforce the need

for a strong, national commitment towards

their elimination.

65 Kennedy, Race and the Fourteenth

Amendment : The Power of Interpretational

Choice. in A Less Than Perfect Union 285

(J. Lobel ed. 1988).

44

guarantee,'66 remedies against private

discriminatory conduct must be preserved.

CONCLUSION

Just as the Constitution by its silence

swept the ugly existence of African slavery

under the rug, a decision to overrule

Runyon may be similarly perceived as an

inability to confront reality coupled with

an unwillingness to care. For those

private individuals drunk with racial

hatred, such a decision will constitute a

green light to execute comfortably their

prejudices. For those historical and

contemporary targets of private

discrimination, — Blacks, Latinos, Jews,

Asians, Arabs, Native Americans, women,

homosexuals — such a decision may well

create a blow so great that their faith and

66 Jones, 392 U.S. at 443 (citations omitted).

45

respect in the integrity of the judiciary

will be forever lost.

Accordingly, and for the reasons set

forth above, and those expressed in

petitioner Patterson's brief, this Court

should not overrule Runyon; rather, it

should reaffirm § 1981's reach to private

discrimination as set forth in Runvon and

affirmatively determine that it encompasses

a claim of racially motivated harassment in

the workplace as destructive of the right

to make and enforce contracts free from

prohibited discrimination.

Respectfully submitted,

STEPHANIE Y. MOORE

ARTHUR KINOY *

FRANK E. DEALE

Center for Constitutional

Rights

666 Broadway, 7th Floor

New York, New York 10012

(212) 614-6437

46

ESMERALDA SIMMONS

WENDY BROWN

Center for Law & Social

Justice

1473 Fulton Street

Brooklyn, New York 11216

WILHELM JOSEPH

National Conference of Black

Lawyers

126 West 119th Street

New York, New York 10027

HAYWOOD BURNS

STEVEN SALTZMAN

National Lawyers Guild

55 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10013

MARGERY GREENBERG

Toward A More Perfect Union

666 Broadway

New York, New York 10012

JEANNE MAT,LETT

National Rainbow Coalition

Policy Committee

1055-H Neil Avenue

Columbus, Ohio 43201

JEANNE MIRER

3310 Cadillac Tower

Detroit, Michigan 48226 *

* Counsel of Record

47

Counsel would like to express their

appreciation for the assistance provided by

Paul Heinzel and H. Susan Nadler in the

preparation of this brief.

APPEN DIX

INDEX TO APPENDIX

Statements of Interest

Association of Latino

Attorneys (ALA).................... ...

Association for

Neighborhood and Housing

Development (ANHD).................. ..

Blacks In Government -

Region I I ............................

Boston Committee for a

Just Supreme Court ................ 3

Capital District Coalition

Against Apartheid

and Racism ...................... ...

Center for Constitutional

Rights ............................. 6

Center for Law and Social

Justice ........................... 7

Clergy and Laity Concerned

(CALC) ............................. 8

Cleveland-Marshall Chapter

of the National Bar

Association, Law Student

Division...........................10

Coalition of Black

Trade Unionists, Pittsburgh

Chapter (CBTU) .................. 11

Coalition for Community

Empowerment . . 13

Community Action for Legal

Services/Legal Support

Unit (CALS/LSU)..................... 14

Committee of Interns and

Residents......................... 16

Congressman Major Owens .......... 18

Franklin Pierce Law Center

Civil Practice Clinic.............. 19

Fund for Open Information

and Accountability,

Inc. (FOIA Inc.)...................19

Gay and Lesbian

Advocates and

Defenders (GLAD) ................ 22

Guardians Police

Association.........................23

Institute of Jewish Law

of Touro College,

Jacob D. Fuchsberg

Law Center.................. .. 24

Jewish Council on Urban

Affairs (JCUA).....................24

La Raza Lawyers' Association

of San Francisco...................25

Lambda Legal Defense

and Education Fund,

Inc................................. 2 6

Metro-Chicago Clergy and

Laity Concerned (CALC) 28

Mid-West Community Council —

Chicago, Illinois ................ 28

Mound City Bar

Association (MCBA).................29

Mountain State Bar

Association, Inc....................31

The Nation Institute.................32

National Conference of

Black Lawyers.................... 3 2

National Lawyers Guild -

National Executive Committee . . . .33

National Lawyers Guild -

Southern Arizona Chapter........... 3 4

National Lawyers Guild -

University of Miami

C h a p t e r ...........................3 6

National Rainbow Coalition,

Inc................................. 38

Plaintiff Employment Lawyers'

Association (PELA)................. 39

Southern California Chinese

Lawyers Association,

(SCCLA)...........................41

Spater, Gittes & Terzian,

et a l .............................43

Student Association

of the State

University of New York,

Inc.................. 44

Toward A More Perfect

U n i o n .............................45

United Automobile Workers

of America Local 2 59 .............. 4 6

United Electrical,

Radio and Machine

Workers of America (UE) 47

1

The ASSOCIATION OF LATINO ATTORNEYS

(ALA) is an association of activist

lawyers, law students, and other legal

workers committed to the political, social

and economic empowerment of the Latino

community in the United States. ALA

recognizes that Latinos have and continue

to suffer discrimination in this society.

Therefore, ALA's work focuses on the

protection of human and civil rights of all

Latinos under the law. ALA believes that a

reconsideration of the applicability of 42

U.S.C. Section 1981 to private entities

threatens established precedent which has

advanced the cause for civil rights. ALA,

as amici to this brief, seeks to urge the

Supreme Court to maintain the precedent set

regarding Section 1981 as integral to the

protection of victims of discrimination.

* * *

2

The ASSOCIATION FOR NEIGHBORHOOD AND

HOUSING DEVELOPMENT (ANHD) is a federation

of over forty non-profit housing groups

whose mission is to advocate and seek to

implement policies and programs that create

and preserve permanent affordable

economical and racially integrated housing

for low and moderate income New Yorkers.

Overruling Runvon v. McCrary would deprive

ANHD's member groups of their ability to

achieve their organizational mission.

* * *

BLACKS IN GOVERNMENT - REGION II (BIG)

is a non-profit organization concerned with

professional and cultural development of

Blacks in government employment. The

membership includes both currently employed

and retired persons from Federal, State and

Local governments. BIG-Region II is the

coordinating body for local chapters of BIG

3

in New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and

U.S. Virgin Islands. The Region II Council

of BIG coordinates the activities of local

chapters and serves as a liaison between

local chapters and the National Office.

Blacks in Government has been in the

vanguard of lobbying efforts for civil

rights statutes, and takes the position

that the reversal of Runyon v. McCrary. 427

U.S. 160 (1976) would be a major setback

for the civil rights gains made since the

reconstruction era.

Therefore, we urge the Court to

reaffirm the holding of Runyon v. McCrary.

427 U.S. 160 (1976).

* * *

The BOSTON COMMITTEE FOR A JUST

SUPREME COURT is a coalition of diverse

organizations that share a common concern

that the present Supreme Court is eroding

4

our fundamental freedoms, especially

through undermining our Constitutional

protections against racial and sexual

discrimination and reproductive freedom.

We believe that overruling Runyon v.

McCrary will set a dangerous precedent

where the Supreme Court will reach out

gratuitously and overturn hard fought civil

rights gains.

* * *

The CAPITAL DISTRICT COALITION AGAINST

APARTHEID AND RACISM (Albany, New York) was

formed in 1981 to organize opposition to a

planned visit to Albany, New York of a

rugby team from the Republic of South

Africa. The COALITION consists of

representatives of more than a dozen

organizations, including local affiliates

of the NAACP, the National Lawyers Guild,

Black Social Workers, YWCA and several

5

local organizations. The COALITION is an

activist grass roots organization dedicated

to ending United States complicity with the

apartheid government of South Africa,

supporting the liberation movement in South

Africa and Namibia, and eradicating racism

in the United States. Towards these ends,

the COALITION has presented educational

forums, has lobbied in the New York State

Legislature and the United States Congress

and has organized demonstrations and

petition campaigns. Since May, 1986 the

COALITION has also participated as a member

organization of the City of Albany's

Community/Police Relations Board.

The COALITION believes that progress

towards eradicating racism depends, in

part, on the existence of a clear mandate

from the United States Supreme Court that

civil rights of minorities are protected

6

and that victims of racism have effective

real avenues of redress. The COALITION is

concerned that if the Court's decision in

Runyon v. McCrary. 427 U.S. 160 (1976), is

overturned, it will create substantial

obstacles for victims of discrimination and

will provide an impetus to those who would

like to see a return to the blatant and

pervasive racism of the period before this

Court's unanimous and historic decision in

Brown v. Board of Education. 347 U.S. 483

(1954), which signaled the end of the legal

system's complicity in racial

discrimination. We urge this Court to re

affirm the holding of Runyon v. McCrary.

427 U.S. 160 (1976).

* * *

The CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS

(CCR) was born of the civil rights movement

and the struggles of Black people in the

7

United States for true equality. CCR

attorneys have been active in cases

involving voting rights, jury composition,

community control of schools, fair housing

and employment discrimination. Through

litigation and public education, CCR has

worked to protect and make meaningful the

constitutional and statutory rights of

women, Blacks, Puerto Ricans, Native

Americans and Chicanos.

* * *

The CENTER FOR LAW AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

at MEDGAR EVERS COLLEGE (CLSJ) is a

research and advocacy institution, created

in 1985 by a special appropriation of the

New York State Legislature, to meet an

existing need within the City of New York

for a civil rights, social justice and

legally oriented institution. The CLSJ

litigation and projects deal with matters

8

of pressing civil and human rights nature

such as employment, education, voting

rights, and housing. Discrimination in

these areas has historically impacted

adversely on the communities we serve which

primarily consist of people of African

descent. CLSJ joins with amici in urging

this Court to reaffirm the reach of Section

1981 to private discrimination and

affirmatively determine that it encompasses

a claim of racially motivated harassment in

the workplace. The continued effectiveness

of our efforts to help reach the goal of a

society free of race discrimination

requires such a ruling by this Court.

* * *

CLERGY AND LAITY CONCERNED (CALC) is a

nationwide multi-racial network of people

of faith and conscience from all walks of

life. CALC represents fifty chapters with

9

35,000 members in the United States and

West Germany. CALC exists to help build a

movement of justice and peace which will

include people of different races,

religions, ages, ethnic and economic

backgrounds. Through education, political

involvement, and the power of truth and

love in action, CALC works for fundamental

social change. CALC brings moral, ethical

and religious values to bear on issues of

human rights, racial and gender justice,

militarism and economic justice at home and

abroad. CALC challenges its members as

well as religious communities and others to

be actively engaged in doing justice and

making peace as taught by all the world's

religious traditions. Founded in 1965,

CALC is an organization committed to

building "the beloved community" called for

by one of CALC's first co-chairs , the

10

Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This

community is inspired by a liberating

spirituality grounded in the sacredness,

harmony and balance of all creation.

* * *

The CLEVELAND-MARSHALL CHAPTER OF THE

NATIONAL BAR ASSOCIATION, LAW STUDENT

DIVISION (NBA,LSD) is an organization that

advances the Science of Jurisprudence,

upholds the honor of the legal profession,

promotes social intercourse among the

members of the bar and Protect the Civil

and Political Rights of All Citizens.

The minority law students at Cleveland

State University chose to take advantage of

the networking and mentorship possibilities

and founded the Cleveland-Marshall Chapter

of the NBA,LSD.

The NBA,LSD focuses upon the concerns

of non-white law students in an effort to

11

promote social intercourse among members of

the bar and Protect the Civil and Political

Rights of All Citizens. The organization

is dedicated to effectuating change by

eradicating racism and discriminatory

policies and attitudes and sensitizing law

schools and the legal profession to the

needs of the Black Community.

Our parent organization, The National

Bar Association, was founded in 1925 and

now represents a network of over 10,000

lawyers, judges, law faculty,

administrators and students. In 1987, the

NBA expressed its commitment to reactivate

its law student division through the

passing of resolutions for that purpose.

* * *

The COALITION OF BLACK TRADE UNIONISTS

- PITTSBURGH CHAPTER (CBTU) is a local

component of a national trade union

12

organization which was established in 1972.

As an organization of Black trade

unionists, we have been concerned and

involved in societal issues which affect

and concern Black people in particular and

the American Labor Movement in general. Of

utmost concern, we have been and continue

to be involved in activities designed to

eliminate racial discrimination and

harassment in the workplace and in the

community at large.

For example, we have fought against

racial exclusion and discrimination of

minorities and women from certain

industries in our community and country,

e.g. construction. We have coalesced with

other concerned organizations to protest

against racially-motivated violence against

minorities. We have provided support to

our members who have sought to use existing

13

laws to provide adequate remedies for acts

of racial discrimination and harassment

committed by private parties and others.

Our belief, interest and concern as

demonstrated by our history is that all

heretofore enacted federal civil rights

laws be vigorously enforced and broadly

applied to prohibit public as well as

private acts of racial discrimination and

harassment. For the foregoing reasons, we

join herein.

* * *

The COALITION FOR COMMUNITY

EMPOWERMENT ("CCE") consists of public

elected officials and private citizens and

is chaired by Congressmen Major Owens. CCE

was formed to mobilize and maximize

participation of black and hispanic

communities in the electorial process. CCE

believes that the denial to blacks and

14

hispanics of the right to vote is

inexplicably linked with the perpetuation

of private discriminatory conduct

throughout our society. Therefore, CCE

joins with amici in support of its position

that private discrimination is prohibited

by the thirteenth amendment and Section

1981. We urge this Court to reaffirm this

principle, and in doing so, the principle

that race discrimination has no place in

this society.

* * *

The COMMUNITY ACTION FOR LEGAL

SERVICES/LEGAL SUPPORT UNIT (CALS/LSU) is a

legal services office that provides support

to casehandlers in neighborhood legal

services offices throughout New York City.

The CALS/LSU has coordinators in

substantive areas of legal practice that

affect poor people's lives and provides

15

training, advice, coordination and co

counselling assistance to attorneys and

paralegals in local legal services offices.

Along with local offices, the CALS-LSU is

involved in a variety of appeals and class

actions involving issues of substantial

impact on the lives of the low-income

client community. The low-income client

population in New York City is composed

overwhelmingly of members of racial

minority groups. The CALS/LSU is

interested in the outcome of the Patterson

case because among the legal rights that

the CALS-LSU defends on behalf of its

client community is the right to be free

from public and private racial

discrimination, and because access to

federal courts to pursue discrimination

claims is critical for our clients.

* * *

16

The COMMITTEE OF INTERNS AND RESIDENTS

(CIR) is a labor organization within the

meaning of the laws of the United States

and the states of New York and New Jersey.

CIR was formed and is perpetuated for the

purpose of representing house staff

officers, (which includes interns,

residents and fellows) in hospitals and

health care facilities, with respect to

compensation, benefits, hours of work,

working conditions, education and the

quality of health care services, delivery

and programs.

CIR has signed collective bargaining

agreements governing the interests of about

5000 house staff officers employed by

voluntary and public hospitals in New York,

New Jersey and Washington, D.C. All of

these contracts contain clauses prohibiting

discrimination by the employers. Typical

17

is the provision in the current contract

between CIR and Catholic Medical Center of

Brooklyn: "The CMC shall not discriminate

against any House Staff Officer on account

of race, color, creed, national origin,

handicap, place of medical education, sex

or age."

With ample justification both parties

to the agreements perceived — irrespective

of whether the hospital was public or

private — that the asserted national

policy, rooted in the Constitution of the

United States, was to remove invidious

discrimination from the life of this

country. This perception had a major

impact on the securing of these non

discrimination clauses.

CIR has a specific interest in the

prevention of invidious discrimination

against those it represents and against

20

ACCOUNTABILITY, INC. (FOIA, Inc.) is an

educational and activist organization

dedicated to fighting for an open and

accountable government. Founded in 1977 to

correct the public record and expose the

injustices suffered by Julius and Ethel

Rosenberg who were executed in 1953 during

a wave of anti-communist hysteria, FOIA,

Inc. has since devoted its activities to

exposing and interpreting a range of

governmental initiatives.

Most recently, in conjunction with the

Center for Constitutional Rights, FOIA,

Inc. obtained enough documentation (through

the Freedom of Information Act) from the

Federal Bureau of Investigation to

convincingly inform the public that the

days of witchhunts are not over. These

documents revealed the FBI's systematic and

thorough program of intimidation,

21

harassment and surveillance of individuals

who dissent from U.S. government policy in

Central America. The issue is one of civil

rights and constitutional protection. It

appears that political activists, when

attempting to reverse the government's

Central American foreign policy, run the

risk of losing their rights to

constitutional protection.

FOIA,Inc. is firmly committed to

affirmative action and to the 1976 Supreme

Court decision in Runyon v. McCrary. While

some defenders of the Constitution prefer

to interpret it as the protector of elite,

white, male slaveholders' interests that it

once was, we understand that the

improvements made to it, particularly in

the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments,

were necessary if our society were ever to

live up to the ideals expressed when this

22

Union was formed.

If the decision of Runvon v. McCrary

is successfully challenged, just as if the

intimidation of political activists

continues, we surely run the risk of

restoring the Constitution to its original

document, devoid of the Bill of Rights.

* * *

GAY AND LESBIAN ADVOCATES AND

DEFENDERS (GLAD), incorporated in

Massachusetts as Park Sguare Advocates,

Inc., a non-profit, tax-exempt corporation,

was founded in 1978 to litigate and educate

on behalf of lesbian and gay civil rights.

GLAD's commitment to broad based civil