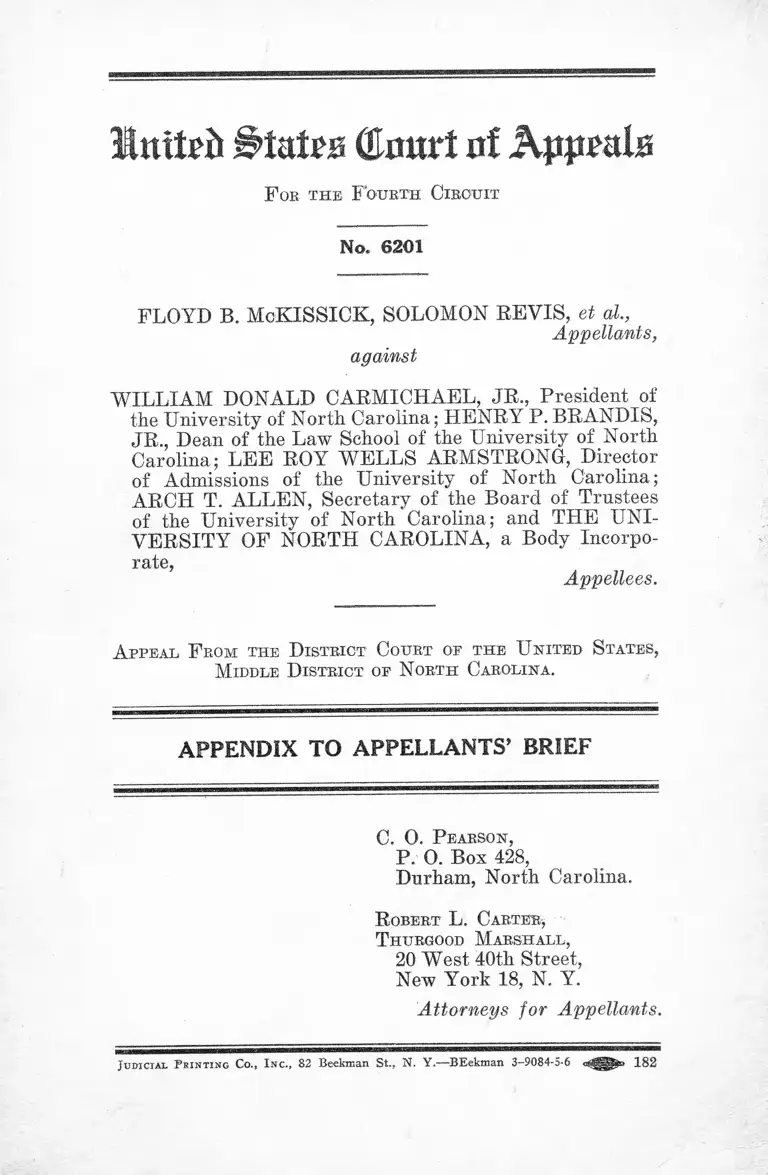

McKissick v. Carmichael Jr. Appendix to Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

October 9, 1950

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McKissick v. Carmichael Jr. Appendix to Appellants' Brief, 1950. e0e48dae-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a8c773e0-f21b-45eb-89ea-3a88577c0980/mckissick-v-carmichael-jr-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

littfceii #tatra Cttnurt of Apprata

F oe, t h e F ourth C ircu it

No, 6201

FLOYD B. McKISSICK, SOLOMON REVIS, et al„

Appellants,

against

WILLIAM DONALD CARMICHAEL, JR., President of

the University of North Carolina; HENRY P. BRANDIS,

JR., Dean of the Law School of the University of North

Carolina; LEE ROY WELLS ARMSTRONG, Director

of Admissions of the University of North Carolina;

ARCH T. ALLEN, Secretary of the Board of Trustees

of the University of North Carolina; and THE UNI

VERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, a Body Incorpo

rate,

Appellees.

A ppe al F rom the D istrict C ourt of t h e U nited S tates,

M iddle D istrict op N orth C aro lin a .

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

C. 0 . P earson ,

P. 0. Box 428,

Durham, North Carolina.

R obert L. C arter,

T hurgood M arsh a ll ,

20 West 40t,h Street,

New York 18, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants.

Judicial Printing Co., I nc., 82 Beekman St., N. Y.— BEekman 3-9084-5-6 182

I N D E X

PAGE

Complaint.......................................................................... 1

Answer .............................................................................. 7

Motion of Floyd B. MeKissick, Sol Revis, Harvey

Beech, Walter Nivins, Perry Gilliard, James Lassiter

to Intervene.................................................................. 14

Motion of J. Kenneth Lee to Intervene ..................... 17

Answer to Complaint of Intervenors .......................... 20

Excerpts From Testimony ............................................ 22

Opinion of Hayes, D. J.................................................... 281

Decree ............................................................................... 290

TESTIMONY

P l ain tiffs ’ W itnesses

William D. Carmichael, J r .:

Direct by Mr. C arter............................................... 27

J. Kenneth Lee:

Direct by Mr. P earson ........................................... 29

Cross by Mr. McMullan.............................. D O

Henry P. Brandis, J r .:

Direct by Mr. Marshall............................................ 38

Cross by Mr. McMullan................ 66

11 INDEX

Redirect by Mr. M arshall-----

Recross by Mr. McMullan

Re-redirect by Mr. Marshall ..

Re-recross by Mr. McMullan .

Re-re-redirect by Mr. Marshall

Lucille Elliott:

Direct by Mr. Pearson ...........

Cross by Mr. Ehringhaus . . .

Redirect by Mr. Pearson.......

Recross by Mr. Ehringhaus ..

Re-redirect by Mr. Pearson ..

Re-recross by Mr. Ehringhaus

Re-re-redirect by Mr. Pearson

Albert L. Turner:

Direct by Mr. Carter . . . . . . . .

Cross by Mr. McMullan........

Redirect by Mr. C arter........

Recross by Mr. McMullan . . .

Janies M. Nabrit:

Direct by Mr. C arter.............

Cross by Mr. Um stead.........

Malcolm Pitman Sharp:

Direct by Mr. Marshall.........

Cross by Mr. Um stead.........

Redirect by Mr. Marshall-----

PAGE

.. 73

.. 76

.. 77

. .. 78

.. 79

.. 79

... 86

, 9 1

. . . 92

. . . 93

. . . 94

. . . 94

. . . 97

. . . 114

. . . 124

. . . 128

. . . 130

. . . 149

. . . 185

. . . 203

. . . 213

I N D E X 111

PAGE

Ervin N. Griswold:

Direct by Mr. Marshall........................................... 216

Cross by Mr. McLendon......................................... 226

Redirect by Mr. Marshall ...................................... 266

EXHIBITS

P l ain tiffs ’ E xhibits

3—Excerpts from Bulletin of University of North

Carolina School of Law showing publication of

the faculty thereof (admitted into evidence at page

130) ........................................................................... 268

6— List of prominent alumni of the University of

North Carolina Law School in Who’s Who in

America (admitted into evidence at page 215) . . . 270

7— Schedule of all North Carolina attorneys listed

in biographical section of the 1950 edition of

the Martindale-Hubbell Law Directory showing

schools in which they received their legal education

(admitted into evidence at page 215) ................... 272

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Httitei) States (Knurl of Apprala

F or th e F ourth C ircu it

F loyd B . M cK issick , S olomon R evis, et al.,

Appellants,

against

W illiam D onald Carm ich ael , J r ., President of the Univer

sity of North Carolina; H en ry P. B randis , J r ., Dean of

the Law School of the University of North Carolina;

L ee R oy W ells A rm strong , Director o f Admissions of

the University of North Carolina; A rch T. A l l e n , Sec

retary of the Board of Trustees of the University of

North Caroline; and the U n iversity oe N orth Carolina ,

a Body Incorporate,

Appellees.

Complaint

1. (a) The jurisdiction of the Court is invoked under

Section 24 (1) of the Judicial Code (28 U.S.C.A., Section

41 (1)), this being a suit which arises under the Constitu

tion and laws of the United States, viz., the Fourteenth

Amendment of said Constitution and Sections 41 and 43 of

Title 8 of the United States Code, wherein the matter in

controversy exceeds, exclusive of interest and costs, the

sum of $3,000.

(b) The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Section 24 (14) of the Judicial Code (28 U.S.C.A., Section

41 (14)), this being a suit authorized by law to be brought

to redress the deprivation under color of law, statute, regu

lation, custom and usage of a state of rights, privileges and

2

immunities secured by the Constitution, and of rights

secured by the laws of the United States providing for equal

rights of citizens of the United States, and of all other per

sons within the jurisdiction of the United States, viz., Sec

tions 41 and 43 of Title 8 of the United States Code.

2. Plaintiffs further show that this is a proceeding for

a declaratory judgment and injunction under Section 274d

of the Judicial Code (28 U. S. C. A., Section 400) for the

purpose of determining questions in actual controversy

between the parties, to wit:

(a) The question of whether the custom and practice

of the defendants in denying, on account of race and color,

to plaintiffs and other qualified Negroes similarly situated

the right to receive educational advantages equivalent to

those offered to whites at the University of North Carolina

is unconstitutional and void as being in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

(b) The question of whether the custom and practice

of the defendants in denying, on account of race and color,

to plaintiffs and other Negroes similarly situated the right

to access to the educational facilities at the University of

North Carolina Law School which is the only facility main

tained by the state where the plaintiffs can secure an edu

cation equal to that offered to whites at the University of

North Carolina.

3. All parties to this action are residents of and citi

zens of North Carolina and of the United States.

4. This is a class action authorized under Rule 23A of

the Rules of Civil Procedure for the District Courts of the

United States. The rights here involved are of common

Complaint

3

and general interest to the members of the class repre

sented by plaintiffs, namely, Negro citizens of the United

States and residents of the State of North Carolina who

possess all the qualifications for admission to the Law

School of the University of North Carolina. The members

of the class are so numerous as to make it impracticable

to bring them all before the Court and for this reason

plaintiffs prosecute this action in their own behalf and

on behalf of the class without specifically naming the said

members therein.

5. Plaintiff, Harold Thomas Epps, is a Negro and is

a citizen of the United States and the State of North Caro

lina and is presently a third-year student in the School of

LawT of the North Carolina College for Negroes; has duly

qualified for admission to the law school of the University

of North Carolina as an advanced student and his admis

sion was refused solely because of his race and color.

6. Plaintiff, Robert Davis Glass, is a Negro and is a

citizen of the United States and the State of North Carolina

and is presently a second-year student in the School of Law

of the North Carolina College for Negroes; has duly quali

fied for admission to the law school of the University of

North Carolina as an advanced student and his admission

was refused solely because of his race and color.

7. Defendant, William Donald Carmichael, Jr., the

President of the University of North Carolina, is the Chief

Academic officer of the University to whom is delegated the

duties of executing the policy and rules adopted by the

defendant-Board of Trustees with respect to the govern

ment of the said University.

8. Defendant, Henry P. Brandis, Jr., Dean of the

University of North Carolina Law School, is the Chief

Complaint

4

Academic Officer of the law school whose duties comprise

the government of said law school, including the admission

and acceptance of applicants eligible to enroll therein as

students, including plaintiffs.

9. Defendant, Lee Roy Wells Armstrong, Director of

Admissions of the University of North Carolina is charged

with the duty of passing on the eligibility for admission

to the University of all applicants who apply therefor,

including plaintiffs.

10. Defendant, Arch T. Allen, is the Secretary of the

Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina

which has overall control of the affairs of the University

and which is incorporated under the name University of

North Carolina. (G. S. 116-03)

11. Defendant, the University of North Carolina, is a

body incorporate under and by virtue of the laws of the

State of North Carolina, and it is sued as such.

12. All defendants herein are being sued in their

official capacities as such.

13. The State of North Carolina has by law estabished

and maintained over the years, and is now maintaining, a

School of Law of the University of North Carolina as a

part of its State University System (G. S. 116-1); that the

said school of law is, as a part of the State University

System, a public institution for the youth of the State (N.

C. Constitution, Article 9, Sec. 7; G. S. 116-1), and is sup

ported by means of public funds. There is no other school

of law maintained and operated out of public funds of the

state where plaintiffs can secure educational advantages

and facilities equivalent to those maintained at the Univer

sity of North Carolina School of Law.

Complaint

5

14. The defendants herein are "by law charged with the

duty of maintaining, operating and supervising the said

school of law of the University of North Carolina and of

effectuating and carrying out its purposes of teaching law

and preparing such persons as are enrolled therein for the

legal profession; that as a part of their said supervisory

control over the school of law, these defendants are clothed

and vested with exclusive authority to pass upon the quali

fications for admission of persons who apply for study and

training in the said school.

15. In compliance and conformity with the procedure,

rules and regulations set out and adopted by these defend

ants for seeking admission to the said School of Law, plain

tiffs, and each of them on or before April 1, 1949, have

timely and properly presented applications to these defend

ants for admission to the said School of Law, and accom

panied said applications with such records of past academic

achievements, character and personality references and

other material as were required; that despite plaintiffs ’ ad

mitted possession of all the necessary qualifications, these

defendants have denied plaintiffs’ admission to said School

of Law solely because of their race and color while at the

same time admitting white applicants with equal or less

qualifications than those possessed by plaintiffs.

16. That the University of North Carolina School of

Law offers a degree of law sought by plaintiffs. They

desire and are ready, willing and able to pay the University

requisite fee and to conform to all the lawful requirements,

rules and regulations for admission.

17. That the policy, custom and usage of the defendants

and each of them of providing and maintaining legal train

ing and facilities at and in the aforesaid school of law for

Complaint

6

white citizens of the state out of public funds while failing

and refusing to provide adequate legal training and facili

ties for plaintiffs and other qualified Negro residents of the

state wholly and solely on account of their race and color

is an unlawful discrimination and constitutes a denial of the

right of plaintiffs and other qualified Negroes to the equal

protection of the laws in contravention of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

18. By virtue of such wrongful actions and illegal

customs and usages on the part of the defendants and

each of them, plaintiffs are damaged and have no adequate

remedy at law.

W herefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray this Court:

(1) That the Court adjudge and decree and declare the

rights and legal relations of the parties to the subject

matter herein controverted, in order that such declaration

shall have the force and effect of a final judgment or decree.

(2) That this Court enter a judgment or decree declar

ing that the policy, custom and usage of the defendants in

refusing admission as students to plaintiffs and other quali

fied Negroes to the School of Law of the University of

North Carolina solely on account of their race and color is

unconstitutional and violative of the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the United States Constitution.

(3) That this Court issue a permanent injunction for

ever restraining and enforcing the defendants and each

of them from denying to plaintiffs possessing the qualifica

tions for admission to the Law School of the University of

North Carolina solely because of color.

(4) That this Court will allow plaintiffs their costs

herein and such further other additional or alternative

Complaint

relief as may appear to the Court to be just and equitable

in the premises.

7

Answer

C. 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

R obert L. Carter

T httrgood M arshall

20 West 40th Street

New York, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Answer

The defendants, answering the complaint herein filed,

allege and say:

1. (a) It is denied that the jurisdiction of this Court

can be properly invoked under Section 24 (1) of the Judi

cial Code (28 U.S.C.A., Section 41 (1)), and it is denied

that this is a suit which can arise under the Constitution

and laws of the United States, to wit: the Fourteenth

Amendment of said Constitution and Sections 41 and 43 of

Title 8 of the United States Code. It is further denied that

the matter in controversy involves any sum of money what

ever, and it is further denied that the matter in controversy

exceeds, exclusive of interest and costs, the sum of $3,000.

(b) It is denied that the jurisdiction of this Court can

properly be invoked under Sections 24 (14) of the Judicial

Code (28 U.S.C.A., Section 41 (14)), as it is expressly

denied there has been any deprivation by the defendants,

under color of law, statute, regulation, custom or usage of

8

rights, privileges and immunities secured to plaintiffs by

the Constitution or laws of the United States.

2. It is admitted that the plaintiffs seek to secure a

declaratory judgment and injunction as alleged in Section

2 of the complaint, but it is denied that there is any basis

for a controversy between the parties to this action.

(a) It is denied that any custom or practice exists on

the part of the defendants or any of them of denying, on

account of race and color, to the plaintiffs or to any other

negro residents of this State, the right to receive educa

tional advantages equivalent to those offered to other resi

dents at the University of North Carolina, and it is denied

that any unconstitutional act has been done by the defend

ants, or any of them, with respect to said matters in viola

tion of the Constitution of the United States or any part

thereof.

(b) It is denied that any custom or practice exists on

the part of the State of North Carolina or defendants, or

any of them, of denying, on account of race and color, to the

plaintiffs or any other negroes who are residents of this

State, access to the educational facilities at the University

of North Carolina Law School without providing substan

tially equal facilities elsewhere in this State. It is alleged

that the State of North Carolina maintains, and has main

tained since 1940 at great expense, at North Carolina Col

lege at Durham, a School of Law at which are provided

facilities substantially equal to those provided at the Uni

versity of North Carolina Law School for the purpose of

furnishing legal education to negro residents of the State

qualified for admission to said school.

3. The allegations contained in Section 3 of the com

plaint are admitted, except, upon information and belief,

Answer

9

Answer

it is denied that Bobert Davis Glass is a resident of this

State.

4. It is denied that this is a class action authorized

under Buie 23A of the Buies of Civil Procedure for the

District Courts of the United States, or that any rights are

here involved which justify or authorize institution of any

class action by these plaintiffs. Section 4 is denied.

5. It is admitted that the plaintiff, Harold Thomas

Epps is a negro and a citizen of the United States, State

of North Carolina, and is presently a third-year student

in the School of Law of the North Carolina College at

Durham, a State educational institution maintained and

operated by the State of North Carolina. Except as ad

mitted in this Answer, Section 5 of the complaint is denied.

6. It is admitted that the plaintiff, Bobert Davis Glass,

is a negro and a citizen of the United States, but it is

denied, upon information and belief, that he is a resident

of the State of North Carolina. It is admitted that he is

presently a second-year student in the School of Law of

the North Carolina College at Durham, a State educational

institution operated and maintained by the State of North

Carolina. Except as admitted in this Answer, Section 6 of

the complaint is denied.

7. It is admitted that the defendant, William Donald

Carmichael, Jr., is the Acting President of the University

of North Carolina and is the administrative head of the

University of North Carolina on account of the said posi

tion. Except as contrary to the facts herein alleged, Sec

tion 7 of the complaint is admitted.

8. It is admitted that the defendant, Henry P. Brandis,

Jr., is now and has been since July 1, 1949 the Dean of

10

the University of North Carolina Law School, is the chief

administrative official of said Law School, and is charged

with the duty of passing upon the academic qualifications

of applicants for admission to the School. It is alleged

that, at the time plaintiffs’ applications were submitted to

the Law School and returned to them, defendant Henry P.

Brandis, Jr. was not Dean of the Law School and had no

official duties in connection with said applications. Except

as herein admitted, the allegations contained in Section 8

of the complaint are denied.

9. It is admitted that Lee Roy Wells Armstrong is

Director of Admissions of the University of North Carolina,

but it is alleged that the duty of passing upon the academic

qualifications of ajoplicants to the Law School is delegated

to the Dean of the Law School. Except as herein admitted,

Section 9 of the complaint is denied.

10. It is admitted that the defendant, Arch T. Allen, is

the Secretary of the Board of Trustees of the University

of North Carolina, which Board of Trustees has such over

all control of the affairs of the University as is provided

by law. It is admitted that the Board of Trustees of the

University of North Carolina is declared to be a body

politic and corporate to be known and distinguished by the

name of the “ University of North Carolina” as provided

in the General Statutes of North Carolina 116-3. Except

as herein admitted, Section 10 is denied.

11. It is admitted that the Board of Trustees of the

University of North Carolina is declared to be a body politic

and corporate and as such is known and distinguished by

the name of the “ University of North Carolina.” It is

admitted that the University of North Carolina may sue

and be sued to the extent and insofar as is authorized by

Answer

11

the provisions of G. S. 116-3. Except as herein admitted,

Section 11 is denied.

12. Section 12 of the complaint is not denied.

13. It is admitted that the State of North Carolina has,

by law, established and maintained over the years, and is

now maintaining, a School of Law at the University of

North Carolina as a part of its higher educational system.

It is admitted that said Law School is supported by means

of public funds. It is denied that there is no other .Law

School maintained and operated out of public funds of

the State where the plaintiffs can secure educational advan

tages and facilities substantially equivalent to those main

tained at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

It is alleged, on the contrary, that the plaintiffs are now

receiving at the State-maintained institution, The North

Carolina College at Durham, at the School of Law at said

institution, educational advantages and facilities substan

tially equivalent to those provided at the University of

North Carolina School of Law. The plaintiffs have here

tofore applied for admission as law students to the Law

School of the North Carolina College at Durham and, based

upon their applications, have been, accepted as law students

at said institution, the plaintiff, Harold Thomas Epps, being

a third-year law student therein and the plaintiff, Robert

Davis Glass, being a second-year law student therein.

14. It is admitted that the Board of Trustees of the

University of North Carolina is, by law, authorized and

empowered to maintain, operate and supervise a School of

Law at the University of North Carolina, which School of

Law has been established for the purpose of teaching law

and preparing such persons as are eligible for enrollment

therein for the legal profession. It is admitted that the

Answer

12

Dean in said Law School is authorized and empowered by

the Board of Trustees to pass upon the scholastic qualifica

tions of applicants for admission of persons who may apply

for admission to the said Law School. Except as herein

admitted, Section 14 of the complaint is denied.

15. It is admitted that the plaintiffs, while attending

the School of Law at the North Carolina College at Durham

and after being* duly enrolled at the said Law School, filed

applications for admission to the School of Law.of the Uni

versity of North Carolina, such applications being* accom

panied with records of their past academic achievements,

and other information. In response to said applications,

the plaintiffs were advised by Robert H. Wettaeh, then

Dean of the Law School of the University of North Carolina,

that they were returned as the State of North Carolina

provided for negro residents of the State a School of Law

at the North Carolina College at Durham which the plain

tiffs well knew since, at said time, both of them were regu

larly enrolled and regularly attending the said Law School.

16. It is admitted that the University of North Carolina

School of Law offers a degree of Bachelor of Laws upon

the successful completion of three years’ work in the said

Law School which is the same degree which is offered by the

North Carolina College at Durham School of Law, which

the plaintiffs are now attending and which they were attend

ing at the time they applied for admission to the Law School

of the University of North Carolina. The defendants have

no knowledge nor information sufficient to form a belief

as to whether the plaintiffs desire and are ready, willing

and able to pay the University the required fees for admis

sion to its Law School. Except as herein admitted, Section

16 is denied.

Answer

13

17. Section 17 of the complaint is denied.

18. Section 18 of the complaint is denied.

W herefore, the defen dan ts resp ectfu lly p r a y :

(1) That the plaintiffs ’ action he dismissed, and that the

Court adjudge that the plaintiffs are not entitled to any

of the relief therein prayed for.

(2) It is further prayed that the defendants recover

their cost in this behalf expended.

The defendants, above-named, pursuant to the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, and any applicable Federal con

stitutional provisions or statutes, do hereby demand trial

hy jury upon all issues raised by the pleadings in this case

or that may be raised by the evidence in this case when

the same is heard.

H arry M cM u llen

Attorney General of North Carolina

Address: Justice Bldg., Raleigh, N. C.

R a l p h M o o d y

Assistant Attorney General

Address: Justice Bldg., Raleigh, N. C.

W illiam : B. U mstead

Address: Durham, N. C.

Answer

L. P. M cL endon

Address: Greensboro, N. C.

Attorneys for Defendants.

(Verified by William Donald Carmichael on December

7, 1949.)

u

To the Judge of the District Court of the United States

for the Middle District of North Carolina, Durham Divi

sion:

Floyd B. McKissick, Sol Revis, Harvey Beech, Walter

Nivins, Perry B. Gilliard, James Lassiter, your petitioners

respectfully move this court for an order allowing them as

members of the class on behalf of which this action is

brought to intervene as party-plaintiffs and respectfully

allege and show as follows:

1. Petitioners are students presently attending North

Carolina College, School of Law at Durham, North Caro

lina. They are all citizens of the United States, residents

of North Carolina and persons of African descent. Each

of these petitioners, has applied individually and on behalf

of himself for admission to the School of Law of the Univer

sity of North Carolina and each has been denied admis

sion to said University solely because of his race and color.

2. The above entitled cause was commenced by service

of the original complaint on defendants, William Donald

Carmichael, Jr., Acting President of the University of

North Carolina; Henry P. Brandis, Jr., Dean of the School

of Law of the University of North Carolina; Lee Roy Wells

Armstrong, Director of Admissions of the University of

North Carolina; Arch T. Allen, Secretary of the Board of

Trustees of the University of North Carolina; and the

University of North Carolina, a body incorporate on the

25th day of October, 1949. The cause has not yet come to

trial but has been continued by consent of both parties until

the first week in April 1950. On February 8, 1950 this

Motion of Floyd B. McKissick, Sol Revis, Harvey

Beech, Walter Nivins, Perry B. Gilliard,

James Lassiter to Intervene

15

court is scheduled to hear argument on motion to strike

this case from the jury calendar.

3. The complaint in this action seeks a declaratory

judgment declaring the legal rights and relations of the

parties hereto and an injunction enjoining the defendants

from refusing to admit the original plaintiffs to the Law

School of the University of North Carolina, solely because

of their race and color, in violation of the 14th Amendment

to the Federal Constitution. The answer to said complaint

sets up the defense that a separate law school has been pro

vided by the State of North Carolina for plaintiffs, in which

they may receive, and are receiving, a legal education sub

stantially equal to that provided by the University of North

Carolina.

4. Petitioners have a right to intervene in the litigation

in the above entitled cause of action against defendants

herein on the ground that: 1) they are members of the class

on behalf of which the original action is brought; 2) the

present plaintiffs may not adequately represent their in

terests for the reason that one of these plaintiffs is a third-

year law student at North Carolina College at Durham and

may graduate before final adjudication of this action; 3) de

fendants have raised a substantial question concerning the

residence of the other plaintiff ; 4) they have a substantial

interest in the subject matter of the action; 5) their in

terest and the main action have questions of law and fact

in common; 6) their intervention will not to any extent

delay or prejudice the adjudication of the rights of the

original parties; 7) said right to intervene arising out of

the facts alleged in your petitioners proposed complaint

of intervention as intervenors, a copy of which is attached

hereto.

Motion of Floyd B. McKissicJc, Sol Revis, Harvey Beech,

Walter Nivins, Perry P>. Gilliard, James Lassiter

to Intervene

1 6

5. The interest of petitioners in the above entitled suit is

such that their intervention in this cause is necessary to

the protection of their interest alleged in paragraph 4 be

cause of the following facts:

1) The present applicants for intervention are all stu

dents qualified for admission to the School of Law of

the University of North Carolina.

2) Each of them has been denied admission solely be

cause of his race and color by defendants herein.

3) Each of them is a member of the class which the

original plaintiffs represent.

4) The original plaintiffs may fail for the reason that

one of them is about to graduate from the School of

Law of North Carolina College at Durham, and the

other may be found to be not a resident of North

Carolina.

5) If the original plaintiffs fail even though they have

brought a class action, the cause of action fails, un

less some other member of the class duly intervenes

as plaintiffs.

W herefore p e tition ers p ra y that th is cou rt m ake an

o rd e r g ra n tin g them leave to file the attached com pla in t

o f in terven tion h erein again st sa id de fen d an ts and f o r such

oth er and fu rth er re lie f as to th is cou rt seem ju st.

Dated 1950

Motion of Floyd B. McKissick, Sol Revis, Harvey Beech,

Walter Nivins, Perry B. Gilliard, James Lassiter

to Intervene

C onrad 0 . P earson

R obert L. Carter

Attorneys for Petitioners

To the Judge of the District Court of the United States

for the Middle District of North Carolina, Durham Divi

sion:

J. Kenneth Lee, your petitioner, respectfully moves this

Court for an order allowing him, as a member of the class

on behalf of which this action is brought, to intervene as a

party-plaintiff, and respectfully alleges and shows as fol

lows :

Motion of J. Kenneth Lee to Intervene

1. Petitioner is a student presently attending North Caro

lina College School of Law, at Durham, North Carolina.

He is a citizen of the United States, a resident of North

Carolina and a person of African descent. He has applied

individually and on behalf of himself for admission to the

School of Law of the University of North Carolina and has

been denied admission to said University solely because of

his race and color.

2. The above entitled cause was commenced by service of

the original complaint on defendants, William Donald Car

michael, Jr., Acting President of the University of North

Carolina; Henry P. Brandis, Jr., Dean of the School of Law

of the University of North Carolina; Lee Roy Wells Arm

strong, Director of Admissions of the University of North

Carolina; Arch T. Allen, Secretary of the Board of Trustees

of the University of North Carolina; and the University

of North Carolina, a body incorporate on the 25th day of

October, 1949. The cause has not yet come to trial but is

scheduled for trial on August 28, 1950.

3. The complaint in this action seeks a declaratory judg

ment declaring the legal rights and relations of the parties

hereto and an injunction enjoining the defendants from re

fusing to admit the original plaintiffs to the Law School

18

of the University of North Carolina, solely because of their

race and color, in violation of the 14th Amendment to the

Federal Constitution. The answer to said complaint sets

up the defense that a separate law school has been provided

by the State of North Carolina for plaintiffs, in which they

may receive, and are receiving, a legal education substan

tially equal to that provided by the University of North

Carolina.

4. Petitioner has a right to intervene in the litigation in

the above entitled cause of action against defendants here

in on the ground that: 1) he is a member of the class on be

half of which the original action is brought; 2) he has a

substantial interest in the subject matter of the action; 3)

his interest and the main action have questions of law and

fact in common; 4) his intervention will not to any extent

delay or prejudice the adjudication of the rights of the

original parties; 5) said right to intervene arising out of

the facts alleged in your petitioners proposed complaint

of intervention as intervenors, a copy of which is attached

hereto.

5. The interest of petitioner in the above entitled suit is

such that his intervention in this cause is necessary to the

protection of his interest alleged in paragraph 4 because of

the following facts:

1) The present applicant for intervention is a student

qualified for admission to the School of Law of the

University of North Carolina.

2) He has been denied admission solely because of his

race and color by defendants herein.

3) He is a member of the class which the original plain

tiffs and the plaintiffs by intervention represent.

Motion of J. Kenneth Lee to Intervene

19

4) If the original plaintiffs and the plaintiffs by inter

vention fail even though they have brought a class

action, the cause of action fails, unless some other

member of the class duly intervenes as plaintiff.

W herefore, petitioner prays that this Court make an

order granting them leave to file the attached complaint of

intervention herein against said defendants and for such

other and further relief as to this Court seem just.

Dated August 27, 1950.

Motion of J. Kenneth Lee to Intervene

C onrad 0 . P earson

R obert L. Carter

Attorneys for Petitioner

20

Answer to Complaint of Intervenors

Defendants, answering the Complaint of the Inter

venors, Floyd B. McKissiek, Sol Revis, Harvey Beech,

Walter Nivins, Perry B. Hilliard and James Lassister,

allege and say:

1. In answer to Section 1, defendants refer to the Com

plaint and Answer filed in this case for the allegations

therein contained. Except as therein shown to be true,

the allegations in Section 1 of the Complaint are denied.

2. The Complaint and Answer heretofore filed in this

cause are referred to for their contents and allegations.

Except as therein shown to be true, the allegations in Sec

tion 2 of the Complaint are denied.

3. Section 3 of the said Complaint is not denied.

4. Answering the allegations of Section 4 of the Com

plaint of the Intervenors, the defendants say that it is not

denied that the intervenors, all Negroes and citizens of the

United States, are also citizens of the State of North Caro

lina, except that it is denied that the intervenor, Perry

Gilliard, is a citizen of North Carolina; it is further not

denied that said intervenors are presently enrolled in the

School of Law of the North Carolina College at Durham;

it is further not denied that the intervenors, Revis and

McKissiek, possess the academic qualifications for admis

sion to the Law School of the University of North Caro

lina, and it is further not denied that the intervenors,

Gilliard, Lassiter, McKissiek and Revis, at the time of

making their motion to intervene, had applied for admis

sion to the Law School of the University of North Carolina

and were denied admission to the same. Except as herein

admitted, the allegations of said paragraph are denied.

21

Answer to Complaint of Intervenors

5. Paragraph 5 of the Complaint of the Intervenors

requires no specific answer except that in general denial

thereof, the defendants herein adopt and make reference

to their Answer heretofore filed in this cause.

W herefore, having fully answered, the defendants re

spectfully refer to and repeat the prayer contained in their

original Answer and further pray that they go without

day and recover their costs and for such other and further

relief as the Court may deem just and proper.

H arry M cM u llan

Attorney General of North Carolina

Address: Justice Bldg., Raleigh, N. C.

R a lph M oody .

Assistant Attorney General

Address: Justice Bldg., Raleigh, N. C.

\Y. B. U msteab

Address: Durham, N. C.

L . P . M cL endon

Address: Greensboro, N. C.

J. C. B. E h rin g h au s

Address: Raleigh, N. C.

22

Excerpts From Testimony

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F ob t h e M iddle D istrict of N orth C arolina—

D u r h a m D ivision

Civil Action No.........

H arold T homas E pps and R obert D avis G lass, Et Al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

W illiam D onald C arm ich ael , Jr,, President of the Uni

versity of North Carolina; H en ry P. B randis, J r ., Dean

of the Law School of the University of North Carolina;

L ee R oy W ells A rm strong , Director of Admissions of

the University of North Carolina; A rch T. A l l e n , Sec

retary of the Board of Trustees of the University of

North Carolina; and the U n iversity of N orth Caro

l in a , a Body Incorporate.

The above-entitled action came on to be heard before

His Honor, Johnson J. Hayes, United States Judge for the

Middle District of North Carolina, at Durham, North Caro

lina, on Monday, August 28, 1950, in the Court Room of the

United States Post Office and Court House Building.

A ppearances :

C. O. P earson , Durham, N. C.; T piurgood M arshall ,

New York, N. Y .; R obert L. Carter, New York,

N. Y .; and S pottswood W. R obinson , III, Rich

mond, V a.; for the plaintiffs.

Hon. H arry M cM u l la n , Attorney General of North

Carolina; Hon. R alph M oody, Assistant Attorney.

General; W. B. U mstead , Durham, N. C.; L. P.

M cL endon , Greensboro, N. C.; J. C. B . E h r in g -

hatts, Raleigh, N. C.; and W. P. B r in k le y , Raleigh,

N. C.; for the defendants.

23

Colloquy of Court and Counsel

(3 ) P roceedings

The Court: Are the plaintiffs ready!

Mr. Carter: Ready, your Honor.

The plaintiffs filed this morning with the Clerk, and

served notice on the defendants, a motion to intervene on

behalf of J. Kenneth Lee, who wants to intervene as a

party plaintiff.

Mr. McMullan: We would like to be heard on that.

The Court: Have you given a copy to the defendants!

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir, this morning.

The Court: Why did you wait until this morning?

Mr. Carter: The intervenor just appeared and desired

to intervene. There are the same issues involved as in the

main case.

The Court: I granted your motion for the intenven-

tion of five or six other plaintiffs, didn’t I—F'loyd B. Mc-

Kissick, Sol Revis, Harold Beech, Walter Nivins, Perry

Gilliard and James Lassiter!

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir. The reason the motion is being

made at this time, your Honor, is that the present inter

venor is a beginning law student. One of the original plain

tiffs in this action, Harold Epps, has graduated from the

Law School of North Carolina College. In order to ade

quately protest the interest Mr. Lee has in the action, we

thought it necessary to make this motion.

(4) The Court: What is the objection?

Mr. McMullan: This is a new name and it takes some

time to investigate these parties, their educational require

ments and whether they are residents of North Carolina.

They have to be investigated by the faculty over at the

University.

Mr. Carter: If I might say a word, Your Honor, this

Mr. Lee applied for admission to the University of North

Carolina School of Law; he secured an application from

24

the school, and the same thing that happened in the other

instances happened in his instance, that his application was

returned by the Dean of the Law School on the ground

there was a school for Negroes at North Carolina College.

The Court: Where does he live?

Mr. Carter: At Greensboro, North Carolina; he is a

citizen and resident of the State.

The Court: When was his application returned?

Mr. McMullan: We don’t known anything about it. The

name has never been presented to us at all.

Mr. Carter: His application, your Honor, was re

turned on the 27th of June by Dean Brandis, of the Univer

sity.

The Court: Well, I will tentatively allow it, and if you

can show me it is any prejudice to the defendants I will

strike it out. I don’t see that it makes any difference one

way or the other, substantially. If we don’t let him inter

vene now (5) he can bring another suit. If it causes any

delay we will give you whatever time is necessary.

Mr. McMullan: We want to file answers to the inter

ventions of all these other plaintiffs.

The Court: Proceed with the evidence for the plain

tiffs.

Mr. Carter: Your Honor, preliminarily, I would like

to get several other points cleared up, if I may.

In the answer which was filed to the complaint, the de

fendants have admitted that the plaintiffs McKissick, Niv-

ins and Revis are citizens of the United States and the State

of North Carolina; that they applied for admission to the

Law School of the University of North Carolina and that

they were refused admission because of race and color.

These two plaintiffs are here ready to testify, but, in order

to save time, I would assume that the defendants would

admit those facts to be uncontroverted and established by

the answer.

Colloquy of Court and Counsel

25

The Court: If they are admitted that establishes it.

I will take whatever facts are admitted by the pleadings.

They are already before the Coui’t.

Mr. Carter: All right, sir. The same thing would apply

to another intervenor, James Lassiter, We will ask Mr.

Lassiter to go to the stand to establish his academic quali

fications, but the defendants have admitted that he is a

citizen of the United States and of the State of North Caro

lina and that he (6) applied for admission to the North

Carolina University School of Law and was refused be

cause of race and color. They have not admitted that he

is qualified; they make no admission or denial in that re

gard.

Tour Honor, there is just one more preliminary with

regard to the status of the various plaintiffs. The original

plaintiff, Harold Thomas Epps, has now completed his

course at the North Carolina College Law School—

The Court: When did he graduate?

Mr. Carter: In June, I believe. In view of that fact,

we would like permission to withdraw him as a party plain

tiff, without prejudice.

The Court: All right, sir.

Mr. Carter: Robert Davis Glass, another original plain

tiff, after the filing of the complaint in which it was alleged

that he was a citizen of the State of North Carolina, ap

plied for and received out-of-state aid from the State of

Alabama, which is only eligible to citizens of Alabama.

Subsequently, on advice of counsel, he sought to return

that aid. Glass has maintained a continuous residence in

the State of North Carolina since that time. That hap

pened last summer. As far as the rules of the University

of North Carolina are concerned, we think that he is a resi

dent. However, we think that his presence in the case

would give rise to objections and injections not (7)

Colloquy of Court and Counsel

26

primarily concerned with the issues involved, and would

like permission to withdraw his name without prejudice.

The Court: All right, sir.

Mr. Carter: In the motion to intervene which the Court

granted on February 8th the names of Harold Beech and

Walter Nivins appeared through error.

The Court: I don’t find in the file, Mr. Clerk, the order

allowing this other intervention. I don’t see it in the papers.

The Clerk’s minutes show I granted the order of interven

tion and the complaint was ordered filed, but it seems there

was no written order filed at the time. The order was

granted here in open court, and I suppose that’s the rea

son there was no written order about it. Let’s come to your

intervenors. What is it you say about them?

Mr. Carter: Harold Beech and Walter Nivins, who are

named in the motion, appear through error. Although they

originally expressed a desire to intervene, they withdrew

and did not make application to the University of North

Carolina.

The Court: They ask to withdraw; is that right?

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir.

The Court: That is allowed.

Mr. Carter: The final one in the same motion, Perry

Gilliard, it appears that he will not be present during the

course of the hearing, and therefore we would like to with-

(8) draw as to him.

The Court: That is three of the intervenors who have

withdrawn ?

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir. That leaves as parties plaintiff

Floyd McKissick, Sol Revis, James Lassiter, and the inter-

venor who was allowed to intervene this morning, J. Ken

neth Lee.

The Court: That leaves us with four plaintiffs; is that

right now?

Mr. Carter: Yes, sir.

Colloquy of Court and Counsel

27

Now with regard to the order, if the Court desires us to

draw an order of intervention and file it as of February

8th, we will do so.

The Court: I think it ’s sufficient. The Clerk’s minutes

show that the Court allowed it in open court. It is customary

to have a written order to that effect, hut it was done in

open court and we can supply that at any time.

Mr. Carter: We would like to invoke Rule 43(b) of

Federal Procedure and call William Donald Carmichael,

Jr., Acting President of the University of North Carolina.

The Court: Let him come around.

William D. Carmichael, Jr.—for Plaintiffs—Direct

(9) WILLIAM D. CARMICHAEL, JR., called as a

witness by the plaintiffs, being duly sworn, testified as

follows:

Direct examination by Mr. Carter:

Q. Mr. Carmichael, would you state your name and

occupation, for the record, please, sir? A. William D.

Carmichael, Junior; Comptroller of the University of North

Carolina; now Acting President.

Q. How long, sir, have you been Acting President? A.

Since March, 1949.

Q. You are at present acting in that capacity? A. Yes.

Q. Mr. Carmichael, who establishes the over-all policy

affecting the University of North Carolina? A. The Legis

lature of the State of North Carolina.

Q. Do you have any policy regarding the admission

of Negroes to the University of North Carolina, and par

ticularly to the Law School of the University of North

Carolina? A. No written policy.

Q. Do you have a policy? A. We have a policy which

is implicit in the establishment by the Legislature of

28

Negro institutions in this state, and the mores and customs

long observed, which have for many years implied (10)

that Negroes would be sent to North Carolina College, to

the A. & T. College, and that white students would go to

the three institutions of the Consolidated University.

Q. Then, as I take it, as you understand the policy and

as you enforce the policy, your policy is to refuse to admit

Negroes to the University of North Carolina? A. I would

say that is the practice, rather than any explicit written

policy.

Q. Regardless of their qualifications? A. Right.

Q. Mr. Carmichael, do you have any policy regarding

the admission of students of other racial groups to the

University of North Carolina? A. I would say no. As a

matter of fact, I don’t think we have any policy in regard

to any. As I said before, we don’t have any policy in

regard to any, that is, written policy.

Q. Let’s call it practice, then. Do you have any prac

tice in regard to the admission of students of other racial

groups? A. The only one that I would recall at the moment

would be the one with regard to Indians from Robeson

County and that vicinity.

Q. What is that policy, that practice? A. There is a

special school for them known as Pembroke College, which

was established for members of that race.

(11) Q. Do you have any practice with regard to the

admission of students to the University of North Carolina

with any ancestry other than that of a Negro? A. No.

Q. Then am I correct in assuming, sir, that the practice

of the University of North Carolina is to admit all racial

groups to the University except Negroes, with the other

exception you mentioned with regard to Indians from Robe

son County? A. So far as I know, I know of no others

who have been excluded.

Mr. Carter: Your witness.

William D. Carmichael, Jr.—for Plaintiffs—Direct

29

Mr. McMullan: If your Honor pleases, we would

like to excuse the witness with the understanding

we can call him back later on.

The Court: All right.

(Witness excused.)

Mr. Carter: Your Honor, we would again like

to invoke Rule 43-(b) and call Lee Roy Wells Arm

strong, the Director of admissions of the University

of North Carolina,

Mr. McMullan: I understood, Counsellor, he was

excused because he didn’t know anything about it,

Mr. Pearson: It was our understanding he was

excused from the taking of the depositions to go to

the beach to get his wife. We did not intend to

excuse him from the trial.

Mr. McMullan: Did you have him subpoenaed

here for today?

(12) Mr. Pearson: No, sir.

The Court: He is not under subpoena?

Mr. Pearson: No, sir, he wasn’t.

The Court: Call your next witness.

J. Kenneth Lee—for Plaintiffs—Direct

J. KENNETH LEE, called as a witness by the plain

tiffs, being duly sworn, testified as follows:

Direct examination by Mr. Pearson:

Q. State for the record your name and where you live.

A. J. Kenneth Lee; and I live in Greensboro, North Caro

lina.

Q. How long have you lived in Greensboro ? A. Eleven

years.

Q. Will you please tell the Court where and when you

30

finished high school? A. I finished high school at Hamlet

High School, Hamlet, North Carolina, in 1940.

Q. After finishing high school, will yon please tell the

Court whether or not you pursued higher education? A.

Yes. I attended A. & T. College at Greensboro, North

Carolina.

Q. Will you please state whether or not you received a

degree while you were there? (13) A. Yes, a B.S. degree.

Q. B.S. in Engineering? A. That’s right.

The Court: What year?

The Witness: 1946.

Q. (By Mr. Pearson) Mr. Lee, will you jfiease tell the

Court whether or not you ever applied to the University

of North Carolina for admission to the School of Law? A.

Yes, I applied this year.

Q. Do you remember the date or month? A. It was in

June of this year. I don’t remember the exact date.

Q. How did you apply? A. I applied by letter.

Q. Did you ask them to send you an application blank?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you receive an application blank? A. Yes.

Q. Is that the blank that you received (exhibiting to

witness) ? A. Yes.

Q. What, if anything, did you do after you received

that application? A. I completed the form and returned

it to the University.

(14) Q. Who did you send it to? A. I sent it to the

Dean of the Law School.

Q. Did you ever get a reply from your application?

A. Yes.

Q. I hand you this and ask you if you know what it is.

A. Yes.

Q. What is it? A. It is the reply received from the

Law School.

J. Kenneth Lee—for Plaintiffs—Direct

31

Mr. Pearson: Yonr Honor, I would like to have

this marked as Exhibit No. 1, the application, and

No. 2, the letter he received from the University,

and I offer them in evidence.

(The documents referred to were received in evi

dence as Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 1 and 2, respectively.)

The Court: Let me see what the reply is.

Bead it.

Mr. Pearson: (Beading) “ Dear Mr. Lee: Your

application for admission to this Law School is here

with returned. As you know, our State maintains

its Law School for our Negro residents at the North

Carolina College at Durham, in which you have been

enrolled. Sincerely yours, Henry Brandis, Ji\”

Dated June 27, 1950.

Q. (By Mr. Pearson) Mr. Lee, you are now enrolled at

the North Carolina College Law School? A. Yes, sir.

The Court: When did you apply for admission

there ?

The Witness: At the North Carolina College

Law School?

(15) The Court: Yes.

The Witness: It was in December, 1949.

The Court: When were you admitted?

The Witness: February, 1950.

The Court: When did you enter that school?

The Witness: In February, 1950.

The Court: Gentlemen, I don’t want to anticipate

too much, but I just wonder if the case isn’t finally

coming right down to the question of whether the

State is providing substantially equal facilities for

higher education at the North Carolina College for

Negroes with those which are offered at the Univer

J. Kenneth Lee—for Plaintiffs—Direct

32

sity of North Carolina. In view of the President of

the Greater University of North Carolina and of the

letter by the Dean of the Law School here, it ap

pears that at present Negroes are excluded from the

Law School at the Greater University of North

Carolina because facilities are provided at the North

Carolina College for Negroes. Now, if that is the

issue, why can’t we just save a lot of time by coming

right down to a comparison and see whether the

State is meeting its obligation in that regard? I am

just asking counsel on both sides for a frank state

ment, because it seems to me that is where we are

arriving.

Mr. McMullan: Answering your Honor, as to

those who intervened in time, your Honor is entirely

correct; there is no question about those who inter

vened in time, but as to this one here there are other

questions that will be raised. We have (16) ad

mitted as to the others, who had made their standing

and grades, that the State has provided for them a

substantially equal opportunity for education at the

North Carolina College Law School.

The Court: Mr. Attorney General, isn’t it also

true, as far as this particular applicant is concerned,

that if he is a citizen of North Carolina, if he made

application for admission, he was denied admission

on the ground he was already enrolled at the North

Carolina College for Negroes?

Mr. McMullan: They wouldn’t admit anybody

who didn’t have a “ C” average.

The Court: After receiving that letter from the

Dean, what would be the use of pursuing it any

further ?

Mr. McMullan: According to the information

I have, he does not have the qualifications.

J. Kenneth Lee—for Plaintiffs—Direct

33

The Court: Are there any questions you have

of this plaintiff?

Mr. McMullan: Tour Honor, every one of these

intervenors, original plaintiffs in this case, were

students at the Law School of North Carolina Col

lege. They went there voluntarily and were pur

suing their studies at the time they applied to the

University of North Carolina. We say they had

made their selection, had been accepted there in good

faith and were pursuing their studies at that insti

tution. I don’t think you (17) will find in any

other case where a student in an institution makes

up his mind to shift in the middle of the term. If he

had any rights he waived those rights by accepting

benefits provided for him by the State.

Teh Court: All right; proceed with the examina

tion of the witness.

Mr. Pearson: We pass the witness, with right

to recall him.

Cross examination by Mr. McMullan:

Q. You say you went to A. & T. College and got your

degree of B.S. there? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And in 1948 you made application to the North Caro

lina College at Durham for admission to the Law School?

A. No.

Q. In 1949? A. In 1950.

Q. You were admitted, were you, in 1950? A. I made

the application to the North Carolina College Law School

in December, 1949, and was admitted in February, 1950.

Q. You made the application in December, 1949, and

were admitted in February, 1950? (18) A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you make that application to North Carolina

College in good faith for admission to the Law School? A.

Yes.

J. Kenneth Lee—for Plaintiffs—Cross

34

Q. You wanted to go there? A. Yes.

Q. You had made some investigation of the facilities

offered you at that Law School, had you not! A. Yes.

Q. And you found that it was a good law school, did you

not? A. It was the only law school; I had no choice at the

time.

Q. You found out it was a good school, did you not?

A. Yes.

Q. And you were admitted there in February, 1950?

A. Yes.

Q. Who was the Dean of that Law School at the time

you were admitted! A. Dr. Turner.

Q. That is Dean Turner here? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you have any complaint about the way the Dean

treated you when you were admitted?

Mr. Marshall: If Your Honor pleases, I object

to this line of testimony. Any plaintiff in a case, any

student, has a (19) right to change his school at

any time he pleases for any reason he might have.

As to what happened in the school, whether he knew

the Dean, who the Dean was, I submit has nothing to

do with the issues in this case. This first-year law

school student can not be testifying as an expert as

to what is an equal law school or good legal education.

The Court: He can testify to such facts as are

in his personal knowledge.

Mr. Marshall: Every question, though, is a con

clusion : Do you think you are getting a good educa

tion ?

The Court: I think that’s competent. Objection

overruled exception. Proceed.

Q. (By Mr. McMullan) How many students were there

in the Law School of North Carolina College when you

J. Kenneth Lee—for Plaintiffs—Cross

35

were admitted? A. I know there were around twenty-eight.

I am not sure of that.

The Court: Is that all years, first, second and

third years?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

Q. How many students were in the average class of the

courses you were taking? A. My classes averaged, I will

say, about nine students.

Q. What courses did you take when you were first

admitted? A. I took courses in torts, real property, criminal

law, contracts.

(20) Q. Can you tell us who were the instructors you

had in those courses? A. Yes.

Q. Tell us who they were, please. A. The course in

contracts was taught by Dean Turner; the course in—

Q. Did you have any complaint about your teaching or

treatment under Dean Turner? A. No. The course in

torts was taught by Mr. Caldwell.

Q. Do you know what school Mr. Caldwell is a graduate

of? A. No.

Q. Did you know he had a degree from the University

of Denver? A. No.

Q. Did you have any complaints about the teaching and

instruction you got at his hands? A. It ’s the first instruc

tion of that type I ever had. I don’t know how to com

pare it.

Q. Did you have any complaint about it? A. No, sir.

Q. Who were the others ? A. The course in criminal law

was taught by Mr. Sanson.

Q. Do you know anything about his academic qualifica

tions and experience as a teacher? (21) A. I understand

he is a graduate of North Carolina College and is practicing

here in the city.

J. Kenneth Lee—for Plaintiffs—Cross

36

Q. Did you Lave any complaint about the instruction

you got at Lis hands ? A. TLe same as the others; I didn’t.

Q. All right, what is the next one? A. The legal writing,

course in legal writing, was taught by Mr. Groves.

Q. Was he a good instructor, as far as you could tell?

A. I thought he was.

Q. Do you know anything about his academic back

ground and experience in teaching? A. No, I don’t.

Q. Who is the next one? A. The course in real prop

erty was taught by Air. McCall.

Q. That is Air. Fred D. AlcCall, of the University of

North Carolina? A. Yes.

Q. This gentleman sitting here? A. That’s right.

Q. Did you have any complaint about the instruction

he gave you? A. Not at all.

Q. Does that cover them all? A. That covers them all.

(22) Q. Now at the time you were admitted to this

institution—that is here in Durham, I believe—were they

occupying the present law building, the one they are using

at the present time? A. Yes, they were.

Q. How about that building; was that building adequate

for your purposes in attending a law school? A. Well,

there were classrooms there. I don’t know just what is

adequate for a law school, but there were classrooms, there

was a library. Now just what is an adequate library, I

don’t believe I would be able to say.

Q. You say you had classrooms and a library? A. Yes.

Q. Can you tell his Honor how many books there were

in the library? A. I am afraid I can’t. I have heard, of

course, but I don’t know.

Q. You didn’t have a chance to read them all? A. No,

not in four months.

Q. Do you understand there are about thirty thousand

volumes in that library? A. I have heard something to

that effect.

J. Kenneth Lee—for Plaintiffs—Cross

37

Q. Did you have any complaint at all about the library?

A. No, I didn’t.

Q. Do you know the man who is the librarian there!

A. Yes.

(23) Q. What is his name! A. Mr. Gray.

Q. Did he have an office there in the building? A. His

office was in the library.

Q. Did you have occasion to call on him for assistance

in the library? A. Yes, at times.

Q. Did you have any complaint about what service you

got there? A. Well, sometimes there were some things I

wanted to find that weren’t there, but I have no complaint

about the service he offered me, what was there.

Q. What did you have complaint about that you wanted?

A. There were some periodicals that were cited to us.

Q. Some magazines? A. Yes.

Q. Name one of them that you wanted you couldn’t get.

A. Offhand I couldn’t do that.

Q. In your classes you say that you had an average of

about nine, did you say? A. I would say that.

Q. On those classes how often would you be called on

to recite or discuss some matter that came up? A. I would

say an average of about once every two or three days.

(24) Q. What method of teaching did they follow at

the North Carolina College Law School? A. As far as I

understand it, the case system.

Q. Did you have any complaint about the method of

teaching that was being followed? A. No.

Q. I don’t believe that you ever presented your certifi

cate showing the grade that you made in law school to the

University of North Carolina, did you? A. No; I was

never asked for it.

Q. You had only been in law school from February

until June when you first made your application? A. Yes.

J. Kenneth Lee—for Plaintiffs-—Cross

38

Q. Was it your reason in applying that yon wanted to

get in the summer school that year? A. No.

The Court: Did you complete your course of

study in the subjects you were taking during the

spring semester?

The Witness: At North Carolina College?

The Court: Yes.

The Witness: Yes, sir.

Q. (By Mr. McMullan) If you don’t go to the University

Law School this fall are you planning to go hack to the

North Carolina College Law School in Durham? A. I

suppose so.

(25) Q. You like the study of law all right? A. So far.

Mr. McMullan: All right; come down.

(Witness excused.)

Mr. Carter: As our next witness, we would like

to again invoke Rule 43(h) and call Dean Henry

Brandis, Jr., of the University of North Carolina

Law School.

Henry P. Brandis, Jr.—for Plaintiffs—Direct

HENRY P. BRANDIS, JR., called as a witness by the

plaintiffs, being duly sworn, testified as follows:

Direct examination by Mr. Marshall:

Q. Dean Brandis, will you give your full name and posi

tion, please, sir? A. Henry Parker Brandis, Jr., Dean of

the Law School of the University of North Carolina.

Q, How long have you been Dean? A. Since July 1,

1949.

Q. You succeeded Mr. Van Hecke? A. No; I succeeded

Mr. Robert H. Wettach.

39

Q. How long have yon been a professor of law at the

University of North Carolina? A. Professor of law, as I

recall, since 1947. I take it you are talking about rank,

literally ?

(26) Yes, I am talking* about, rank. And how long have

you been teaching law at the University of North Caro

lina? A. With the exception of the war years and one

other semester, since 1940, a net total of around six years.

Q. Prior to that time had you had any teaching ex

perience at any other law school? A. No.

Q. Approximately how many years would you say your

experience has been in the teaching profession, the teach

ing* of law? A. A net of around six years, maybe six and

a half.

Q. What other work have you done? A. I practiced

law in New York City for several years; I was with the

Institute of Government, now a part of the University, at

that time a separate institution.

Q. You mean of the University of North Carolina? A.

Yes; at the time I was with it, it w*as not part of the Uni

versity. For roughly four years I was Executive Secre

tary of the State Taxation Classification Commission; I

was Chief of the Research Division of the State Depart

ment of Revenue; and I was for three and a half years in

the United States Navy.

Q. Dean Brandis, you heard the testimony of the Act

ing President as to the policy in regard to the admission

or non-admission of Negroes to the University of North

Carolina.

Do I understand that the admission of students to the

(27) Law School is under your jurisdiction and not the

Registrar’s jurisdiction? A. There is no Registrar of the

University of North Carolina.

Q. I mean the Director of Admissions. A. As a prac

tical matter, that is correct.

Henry P. Brandis, Jr.—for Plaintiffs—Direct

40

Q. What is the policy of your office in relation to the

racial restrictions, if any, as to the admission of students?

A. We follow what we understand to he the policy of the

State.

Q. Which is? A. Which is not to admit Negroes.

Q. Who do you classify as Negro? A. I don’t think I

have ever had to make a decision on that problem.

Q. Well, let’s try this one. Assuming that a person

otherwise qualified is of any racial group other than a

Negro, is it not true that no question would be raised as

to his admission? A. Actually I have never had to face

that problem either because, since I have been Dean, I have

had no application from any person whose racial situation

might raise any question, so far as my personal experience

is concerned there is no answer to it.

Q. As to your personal experience, if a person other

wise qualified is not a Negro, you make no question as to

what family (28) background he has, what ethnic group

he belongs to, or anything else about his race or ancestry?

A. So far as the applications I have processed so far, that

is true.

Q. So that the only people who get a special treatment

—and I am not speaking facetiously—who get disqualifica

tion automatically on racial grounds are those who happen

to fall within the racial group of Negro? A. That has been

true within my limited experience. I think Mr. Carmichael

mentioned one other that might lead to the same result.

Q. I understand there is no question as to the Indians

from Robeson County; that hasn’t come up in your ad

ministration so you do not know about that.

How long has the University of North Carolina Law

School been in operation as the University of North

Carolina Law School? A. I t ’s a little difficult to give a

categorical answer, because the beginnings of the Law

School go back to about 1845 when, with the approval of

Ilenry P. Brandis, Jr.—for Plaintiffs—Direct

41

the Trustees of the University, a Professorship of Law was

established, but for many years the Professor of Law was

not paid a salary by the University but received only fees

from his students. He had no assistants. He was simply

a Professor of Law, what might be called an adjunct of

the University, and a question whether you could say (29)

strictly a part of it. The Law School was not formalized

into a school with a dean, as part of the University, until

about 1900.

Q. And since that time it has operated as a law school!

A. Yes.

Q. Dean Brandis, if you were comparing two law

schools, or three or four, as to the caliber of the law school

in regard to faculty and student body, what facts would

you consider fair to be used in evaluating lawT schools! A.

You are asking me to try to give a complete list, now!

Q. Maybe I can suggest some. Let’s see if we agree

on them. The reputation of the school would be important,

would it not! A. Yes, sir.

Q. Would not the length of years that the school had

operated be considered in its reputation, as one of the

factors of its reputation! A. Yes, sir.

Q. And is it not also true that the number of years

alone is not enough; that there are other factors which

would be taken into consideration—isn’t that true? A.

Well, I take it that as to anything you raise we are agree

ing that it is simply a factor. I f I say “ yes,” it is very

obvious we couldn’t make the decision on that alone.

(30) Q. Wouldn’t the type of faculty be a point to be

considered! A. It would,

Q. In that would you include the experience as well as

the background of the faculty members? A. I would.

Q. Would you include their government service, out

side of their legal service—I mean legal government service

in government agencies—as a factor? A. Yes. I would

Henry P. Brandis, Jr.—for Plaintiffs—Direct

42

like to say this: Of course I would want to know the par

ticular type of service.

Q. Assuming it was connected with their teaching, with

the same subjects they are teaching! A. For instance, my

own government service was military service, and I

wouldn’t regard that as a factor.

Q. Mr. Van Hecke’s experience with the War Manpower

Commission helps him in his teaching! A. I agree.

Q. Would you not also consider the creative work done

by a faculty in the writing of textbooks, case books on law,

and reviewing articles! A. I would.

Q. Would you consider whether or not the school was

a member of the Association of American Law Schools a

point to be considered! (31) A. Yes, sir.

Q. And, of course, approval or non-approval of the

American Bar Association! A. Yes.

Q. As between the two on that, which of the two groups

has the strictest standards, the Association of American

Law Schools or the American Bar Association! A. May I

volunteer here that if I considered, as I would, membership

in the Association, I would consider that against the back

ground of whether or not the school had applied for mem

bership!

Q. But, surely— A. In other words, a better criterion

would be not actual membership, but whether it meets the

standards of the Association.

Q. Do you know, off band, of any longstanding law school

of high standing that doesn’t belong to the Association of

American Law Schools! A. I have never investigated that

question.

Q. You have been to the meetings of the Association!

A. I have.

Q. Don’t you find the cream of the crop of the law-teach

ing profession there! A .'I suppose that is what we think

we are.

Henry P. Branclis, Jr.—for Plaintiffs-—Direct

43

Q. Isn’t it true that in your rating, for example of stu

dents, (32) isn’t it true that, as the University of North

Carolina you don’t accept students from non-member

schools for advanced standing? A. Yes, sir.

Q. It is true? A. Yes.

Q. There is a relationship between member schools of