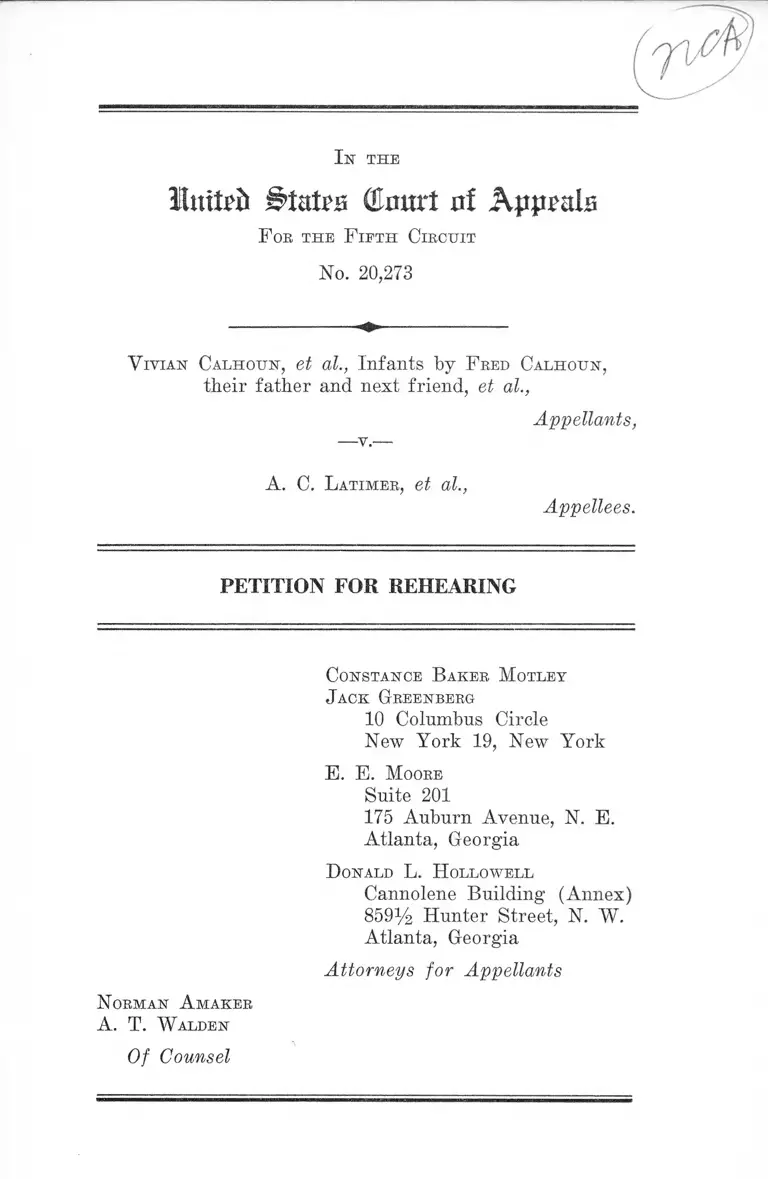

Calhoun v. Latimer Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

July 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Calhoun v. Latimer Petition for Rehearing, 1963. 9d1a378e-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a8d7e1d7-3585-4b73-8c1d-956a8d448eb9/calhoun-v-latimer-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

United States (tort nf Appeals

F oe th e F if t h Ciechit

No. 20,273

I n the

V ivian C alhotjn, et al., Infants by F eed Calh o u n ,

their father and next friend, et al.,

Appellants,

A . C. L atim er , et al.,

Appellees.

PETITION FOR REHEARING

Constance B aker M otley

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

E. E. M oore

Suite 201

175 Auburn Avenue, N. E.

Atlanta, Georgia

D onald L. H ollowell

Cannolene Building (Annex)

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

N orman A makeb

A. T. W alden

Of Counsel

I n the

ituitTii States (to rt ni Appals

F or th e F if t h Circuit

No, 20,273

V ivian Calh o u n , et al, Infants b y F red Calh o u n ,

their father and next friend, et al.,

— v .

Appellants,

A. C. L atim er , et al.,

Appellees.

PETITION FOR REHEARING

To: The Honorable Richard T. Rives and The Honorable

Griffin B. Bell, Judges, United States Court of Ap

peals, Fifth Circuit, and The Honorable David T.

Lewis, Judge, United States Court of Appeals, Tenth

Circuit, sitting by designation as a Judge of the

United States Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit.

Appellants, by their undersigned attorneys, petition this

Court for a rehearing of their appeal in this case before

the Court en banc as permitted by Rule 25(a) of the Rules

of this Court. As reasons therefor appellants show the

following:

1. The instant appeal involves the important question of

public school desegregation in the City of Atlanta, Georgia

and was taken to this Court from the denial by the District

Court of a motion for further relief which sought, in es

sence, to decrease from a period of 12 years to 7 years the

period of transition from segregated to desegregated

2

schools. The motion further sought to require the reorgan

ization of the dual school system into a unitary non-

racial school system and, as the basis for assignment of

students to school, a single nonracial school attendance

area system in lieu of the pupil assignment plan presently

in effect. Further relief was also sought with respect to

assignment of professional school personnel on a nonracial

basis.

2. The appeal was argued on May 1, 1963 before a three-

judge panel of this Court consisting of Judge Richard T.

Rives, Judge Griffin B. Bell and Judge David T. Lewis

of the Tenth Circuit sitting by designation. On June 17,

1963, the majority of the panel, consisting of Judges Lewis

and Bell, affirmed the District Court’s denial of the motion

for further relief. Judge Rives dissented.

3. The decision of the majority is contrary to prior

recent decisions of this Court in similar school desegrega

tion cases. Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306

F. 2d 862; Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d

491.

4. The majority opinion also fails to discuss the legal

significance of undisputed facts in the record with respect

to the presently existing dual school zone lines based on race

for each school in the City of Atlanta.

5. The majority opinion also fails to give weight to the

undisputed fact that Negro children seeking assignment

to white high schools in grades desegregated, pursuant to

the present desegregation timetable, are subject to a “ per

sonality interview” not required of white students and are

subject to an analysis of their scores made on certain

scholastic tests, given to white and Negro children alike,

3

in considering the eligibility of Negro children to transfer

from Negro schools to white schools.

6. This is the first case decided by this Circuit since the

Supreme Court in Watson v. City of Memphis,------U. S.

------ , No. 424, Oct. Term 1962 (decided May 27, 1963) and

in Goss, et al. v. Board of Education of the City of Knox

ville, ------ U. S .------- , No. 217, Oct. 23, 1962 (decided June

3, 1963) admonished that the passage of time since its

decision in the Brown case in 1954 required a revision of

the standards of deliberate speed now applicable to the

period of transition from a segregated to a desegregated

school system.

7. The majority opinion also does not apply the criterion

established in the Goss case, supra, with respect to deter

mining whether a school desegregation plan or any feature

thereof tends to retard or prolong desegregation or to per

petuate racial segregation in the public school system.

8. Neither the Watson case, supra, nor the Goss case,

supra, was argued or briefed when this appeal was heard

on May 1, 1963, since both of these cases were decided sub

sequent thereto.

9. The majority opinion does not secure or maintain

uniformity or continuity in the decisions of this Court in

similar cases.

10. In the light of the Watson decision the majority

opinion in this case is now of major import and should be

reheard by the court en banc.

4

W herefore, for all of the foregoing reasons, appellants

respectfully pray that the entire Court rehear this appeal.

Respectfully submitted,

Constance B aker M otley

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

E. E. M oore

Suite 201

175 Auburn Avenue, N. E.

Atlanta, Georgia

D onald L. H ollowell

Cannolene Building (Annex)

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

N orman A maker

A. T. W alden

Of Counsel

5

Certificate of Counsel

The undersigned attorney for appellants certifies to this

Court that the foregoing Petition for Rehearing is pre

sented in good faith and not for the purposes of delay.

>?/ A

Certificate of Service

T his is to certify that on the day of July 1963

I mailed to A. C. Latimer, Esq., Healey Building, Atlanta,

Georgia and Newell Edenfield, Esq., 715 Citizens and South

ern National Bank Building, Atlanta, Georgia, Attorneys

for Appellees, a true and correct copy of the foregoing Peti

tion for Rehearing in this case by mailing a true copy of

same to each of them at the addresses shown herein via

Special Delivery Airmail.

Attorney for Appellants