Caston v. Sears, Roebuck and Co. Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

February 2, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Caston v. Sears, Roebuck and Co. Brief for Appellant, 1976. 6aea0e19-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a8dec82e-fb74-4ecb-bac1-e3203068fe6e/caston-v-sears-roebuck-and-co-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

''{ A

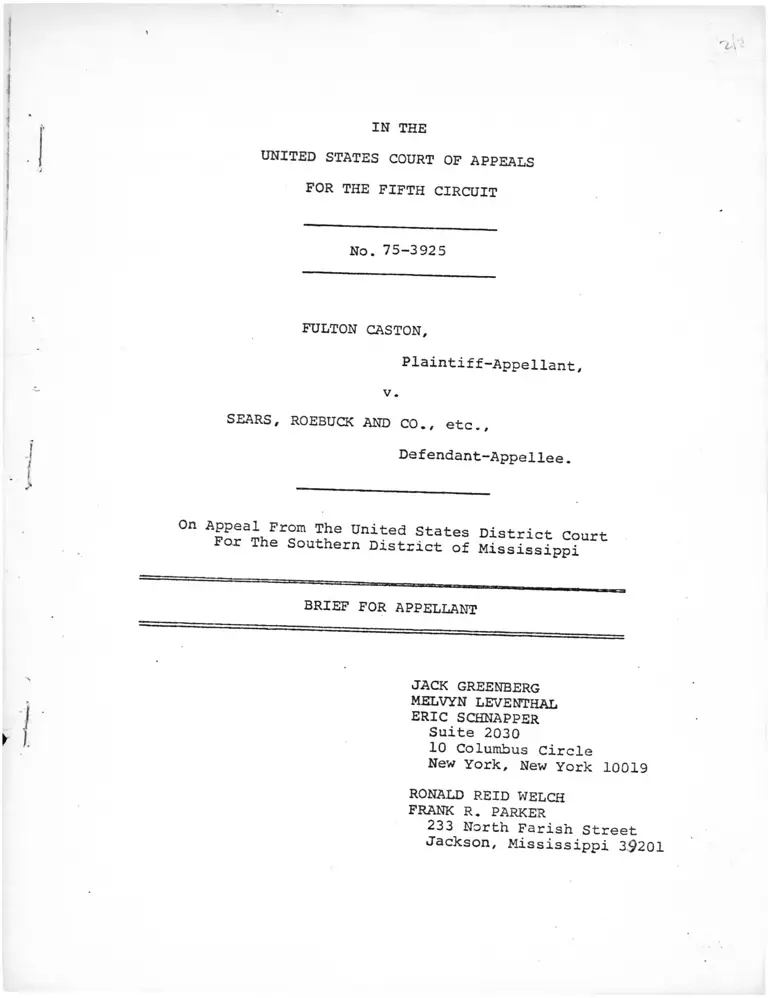

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-3925

FULTON CASTON,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

SEARS, ROEBUCK AND CO., etc.,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The southern District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

JACK GREENBERG

MELVYN LEVENTHAL

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

RONALD REID WELCH

FRANK R. PARKER

233 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-3 92 5

FULTON CASTON,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

SEARS, ROEBUCK AND CO., etc.,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District of Mississippi

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY

FIFTH CIRCUIT LOCAL RULE 12(a)

The undersigned, counsel of record for Plaintiff-

Appellant, certifies that the following listed parties have

an interest in the outcome of this case. This representa

tion is made in order that Judges of this Court may evaluate

possible disqualification or recusal pursuant to Local Rule

12(a) .

1. Fulton Caston

Sears, Roebuck and Company

Attorney of Record For Plaintiff-

Appellant

2 .

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Statement of Issues Presented For Review

Statutory Provisions Involved .........

Statement of the C a s e.................

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court's Order Denying

Appointed Counsel Is Appealable ...

II. The District Court Erred In Denying

Appointed Counsel ................

III. Procedure On Remand ................ .

CONCLUSION

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Adkins v. duPont Co.f 315 U.S. 331 (1948) .......... 15

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 45 L .Ed. 2d

280 (1975) ................... ................... 7

Allison v. Wilson, 277 F.Supp. 271 (N.D. Cal. 1967) . 16

Argersinger v. Hamlin, 407 U.S. 25 (1972) .......... 10

Beverly v. Lone Star Lead Construction Co.,

437 F . 2d 1136 (5th Cir. 1971) ................... i3

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

416 U.S. 696 (1973) .............................. i7

Burns v. Thiokol Corp., 483 F.2d 300 (5th Cir.

1973) ......... 9

Caston v. Sears, Roebuck Co., No. 75-3679 .......... 4

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167

(2d Cir. 1972) 9

Edmonds v. E. J. duPont de Nemours & Co.,

315 F.Supp. 523 (D. Kan. 1970) .................. 9, 20

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 370 F.2d 118

(2d Cir. 1966) 6

Farretta v. California, 45 L.Ed. 2d 562 (1975) ..... 6

Flowers v. Turbine Support Division, 507 F.2d

1242 (5th Cir. 1975) ............................ 4> 5

Ford v. United States Steel Corp., 520 F.2d 1043

(5th Cir, 1975) 10

Franks v . Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d

398 (5th Cir. 1974) ................... ]......... 9

Harris v. Walgreen's Distribution Center, 456

F.2d 588 (6th Cir. 1972) ........................ 14

Page

. v • r ■

-ii-

*■ * V .4 '

Huff v. N.D. Cass, 485 F.2d 710 (5th Cir. 1973) ___ 9

Huston v. General Motors Corp., 477 F.2d 1003

(8th Cir. 1973) 20

H. Kessler v. E.E.O.C., 472 F.2d 1147

(5th Cir. 1973) 8

Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969) ................................ g

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792 (1973) ..................................... g, 13, 14

Miller v. Pleasure, 296 F.2d 283 (2d Cir. 1961) ___ 5

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S

400 (1968) ..................................... 7, 10f n

Otis v. Crown-Zellerbach, 398 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1968) ........ g

Petete v. Consolidated Freightways, 313 F.Supp.

1271 (N.D. Tex. 1970) .......................... a, 15

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932) ............. 10

Roberts v. United States District Court,

339 U.S. 844 (1950) ............................ 5

Robinson v. Western Electric Co., 3 EPD f 8240

(7th Cir. 1971) 14

Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1971) ... 8

Spanos v. Penn Central Transportation Company,

470 F . 2d 806 (3d Cir. 1972) .................... 5

United States v. Birrell, 482 F.2d 896

(2d Cir. 1973) 5

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d

906 (5th Cir. 1973)............................. 10

Page

Page

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1915

42 U.S.C. § 2000e; Title VII of the

1964 Civil Rights Act .........

....... 2, 12, 18

4, 9, 10, 15, 16, 18

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (f) ; Title VII of

the 1964 Civil Rights Act, section

706(e) ....... ................. 1, 2, 6, 8, 11, 12, 13,

15, 16, 18, 19, 20

27 Stat. 252 13

86 Stat. 1127 17

Other Authorities:

1974 U.S. Code Congressional and

Administrative News 1372 ....................... 27

110 Cong. Rec. ........................ 8, 11, 12, 14, 17, 18

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ...........

-iv- V' .•

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-3925

FULTON CASTON,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

SEARS, ROEBUCK AND CO., etc.,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

(1) Is the order of the district court refusing to

appoint counsel pursuant to section 706(e) of Title VII

of the 1964 Civil Rights Act appealable?

(2) Did the district court apply the correct standards

in refusing to appoint counsel pursuant to section 706(e)?

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

Section 706(e) of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f) provides in pertinent

part:

Upon application by the complainant

and in such circumstances as the court may

deem just, the court may appoint an attorney

for such complainant and may authorize the

commencement of the action without payment of

fees, costs, or security.

Section 1915(d), 28 U.S.C., provides:

The court may request an attorney to

represent any such person unable to employ

counsel and may dismiss the case if the allegation

of poverty is untrue, of if satisfied that the

action is frivolous or malicious.

- 2 -

t

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

For several years prior to 1974 plaintiff, a

black man, was employed by the Sears, Roebuck & Company

in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. On January 28, 1974,

plaintiff was discharged. On January 30 , 1974, plain

tiff filed a timely charge with the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission alleging that he had been dis

charged because of his race. On May 29, 1975, the

Acting District Director of the Jackson Office of E.E.O.C.

issued a determination that there was not "reasonable cause

to believe that Charging Party was discharged because of

his race." A3.

On May 29, 1975. the E.E.O.C. issued to plain

tiff a Notice of Right to Sue which stated in pertinent

part:

If you are unable to retain an attorney,

the Federal District Court is authorized

in its discretion to appoint an attorney

to represent you . . . . If you decide to

institute suit and find you need assistance,

you may take this letter, along with any cor

respondence you have received from the Com

mission, to the Clerk of the Federal District

Court nearest to the placevhere the alleged

discrimination occurred, and request that a

Federal District Judge appoint counsel to

represent you. A3.

On September 15, 1975, plaintiff-appellant went to the

United States District Court in Hattiesburg, Mississippi,

and asked that such counsel be appointed to assist him.

The district court refused to do so because the E.E.O.C.

officials had not sustained plaintiff's charge of dis

crimination. A 16 The court gave plaintiff 10 days in

which to retain an attorney. A .16.

-3p£

When plaintiff

protested this denial of counsel as unfair, the district

judge, the Hon. Harold Cox, summarily found him in con

tempt of court and sentenced him to 90 days in jail.

This contempt conviction is the subject of another appeal

in this Court. Caston v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., No. 75-3679

Despite the 10 day deadline it had established for retaining

counsel in this civil action, the district court directed

that plaintiff begin serving the 90 day sentence immediately

Twelve days later, after the deadline had passed, the dis

trict court permitted plaintiff to be released on bail

pending the appeal of his criminal conviction.

Plaintiff's counsel in the instant civil appeal

have undertaken to represent him solely in connection with

this appeal from the denial of appointed counsel. They

have not agreed to represent plaintiff in any proceeding

on the merits in the district court and do not seek a

court assignment to do so.

ARGUMENT

I - The District Court's Order Denying

Appointed Counsel Is Appealable

This Court's decision in Flowers v. Turbine

Support Division, 507 F.2d 1242 (5th Cir. 1975), clearly

establishes that the denial of counsel is an appealable

order. In Flowers plaintiff, nine months after filing

suit under Title VTI, applied for in forma pauperis

status, and appealed when the request was denied. This

Court held:

4

Orders denying applications to

proceed ISU?>*M;e appealable as final

decisions for reasons similar to

those which prompted the Supreme Court

to hold that the order in Cohen v.

Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp., 337

U.S. 541, 69 S.Ct. 1221, 93 L.Ed. 1528

(1949) was appealable. An order denying

IFP status finally decides an important

issue which is collateral to the merits

of the case. It is an order which"is "too

important to be denied review and too in

dependent of the cause itself to require

that appellate consideration be deferred

until the whole case is adjudicated.

Cohen, supra, at 546 69 S.Ct. at 1226.

More importantly, it is an order the

review of which cannot be deferred until the

whole case is decided. Denial of IFP, if

— erroneous, tends to close the door of the

courthouse to the true pauper, forcing him

to forfeit his day in court. Such a person

has little hope of successfully prosecuting

his case to a traditional final judgment.

507 F.2d at 1244. The Supreme Court held such denials

appealable in Roberts v. United States District—Court,

339 U.S. 844 (1950). The reasoning of Flowers and Roberts

applies as well to a request for the appointment of

counsel, denial of which is as likely to prevent

meaningful prosecution of a case as a denial of forma paupe_ris

treatment. The Second and Third Circuits have both held

that the denial of appointed counsel is an appealable order.

Miller v. Pleasure, 296 F.2d 283, 284 (2d Cir. 1961);

Spanos v. Penn Central Transportation Company, 470 F.2d

806 807-8, n.3 (3d Cir. 1972); United States v. Birrell,

482 F.2d 896, 892 (2d Cir. 1973).

The denial of appointed counsel will be, in

most cases, "the death knell of the action." Eisen v.

5

Carlisle & Jacquelin, 370 F.2d 118, 121 (2d Cir. 1966).

In view of the complexities of Title VII law, and with

the defendant represented by skilled counsel, it would

usually be foolhardy for an aggrieved employee to attempt

to prosecute such a case pro se. Farretta v. California,

45 L.Ed. 2d 562, 581, 592 (1975). Where a request for

counsel under § 706(e) is denied, the preferred practice

is clearly to pursue an appeal directly from that order.

To require an employee to go forward without the assistance

of counsel would serve no end other than to humiliate

the plaintiff by forcing him to abandon his claim or go

through the motions of a trial which would be but a carica

ture of justice and whose conclusion would never be in

doubt.

II. The District Court Erred in Denying Appointed

Counsel

The district court refused to appoint counsel

to represent Appellant solely because an E.E.O.C. official

had not found probable cause to conclude the defendant

had discriminated against plaintiff. That refusal was

erroneous as a matter of law, and squarely in conflict

with the purposes of section 706(e) and Title VII.

Section 706(e) of Title VII of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (f) (1), provides in

pertinent part:

Upon application by the complainant

and in such circumstances as the court

may deem just, the court may appoint

an attorney for such complainant and

may authorize the commencement of the

action without the payment of fees, costs,

-6-

or security.

This provision, like all other remedies under the Act,

is one which the courts "may" invoke, but that term

does not convey broad unfettered discretion.

The scheme implicitly recognizes that

there may be cases calling for one

remedy but not another, and - owing to

the structure of the federal judiciary -

these choices are of course left in the

first instance to the district courts.

But such discretionary choices are not

left to a court's "inclination, but to

its judgment; and its judgment is to

be guided by sound legal principles."

United States v. Burr, 25 Fed Cas 30,

35 (Marshall, C. J.). The power to

award backpay was bestowed by Congress,

as part of a complex legislative design

directed at an historic evil of national

proportions. A court must exercise this

power "in light of the large objectives

of the Act," Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321

US 321 .331.

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 45 L.Ed. 2d 280, 295-96

(1975).

When Title VII was adopted in 1964,Congress

recognized "that enforcement would prove difficult and

that the Nation would have to rely in part upon private

litigation as a means of securing broad compliance with.,,, •

the law." Newman v. Pigqi'e^ark Enterprises, 3 90 U.S.

400, 401 (1968). Congress also forsaw that most aggrieved

parties would be unwilling or unable to bear the cost

of successfully prosecuting an action under the

statute. Id- at 402 • To assure that enforcement of

the law would not be hindered by these costs, Congress

-7-

provided for counsel fees for prevailing plaintiffs

and authorized court appointed counsel as well- The

latter provision was deemed necessary because the

mere possibility of a contingent court awarded fee

might not prove sufficient to persuade an attorney to

undertake a Title VII case.

Cost was not the only concern which prompted

the adoption of section 706(e). Congress was also aware

that "other justifiable reasons" might prevent an ag

grieved party from obtaining the assistance of counsel

uthrough ordinary means. This Court has long recognized

the difficulty in finding attorneys to handle cases of

this sort. In Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241, 245

(5th Cir. 1971) the Court noted:

It is no overstatement that in Mississippi

and the South generally negroes with civil

rights claims or defenses have often found

securing representation difficult. . . .

[I]n damage cases brought by negro plain

tiffs against white defendants, the slight

chance of contingent fee recovery does not

suggest that economic benefits are or will

be such as to outweigh, for appreciable

numbers of Mississippi lawyers, their re

luctance to become identified with the

negro civil rights effort.

In H. Kessler & Co. v. E.E.O.C., 472 F. 2d 1147, 1152

(5th Cir. 1973) the Court observed:

The courts of this circuit have previous-ly

found that competent lawyers are not eager

to enter the fray in behalf of a person

seeking redress under Title VII. This is

true even though provision is made for

payment of attorney's fees in the event of

success.

In Petete v. Consolidated Freightwavs, 313 F.Supp. 1271,

/ Section 706(e); 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f).

_/ See 110 Cong. Rec. 12713 (Remarks of Sen. Humphrey),

-8-

1272 (N.D. Tex. 1970), Judge Hughes found the attorneys

whom Petete had approached reluctant "to undertake the

specific and complex challenges of a Title VII lawsuit

which are not common to more frequently litigated areas

of the law," a problem similar to that noted by Judge

Templar in Edmonds v. E.J. duPont de Nemours & Co^,

315 F.Supp. 523, 524 (D. Kan. 1970).

Congress correctly forsaw that Title VII

litigation would present problems with which layman,

and in some cases ordinary practitioners, were not

equipped to deal. Over the last decade the appellate

courts have struggled with difficult questions of pro-

3 / / . . . . , . , cedure, burden of proof, definitions of violations and

6_/

limitations on remedies,creating in the process a highly

complex body of case law to be applied in each case.

The presentation of a Title VII action frequently involves

extensive discovery” analysis of complicated and sometimes

8_/ . ̂

inconsistent statistics, the assistance of a variety of

3 / See e.q. Otis v. Crown-Zellerbach, 398 F.2d 496

7*5th Cir. 1968) ; Huff v. N. D. Cass, 485 F.2d 710 (5th

Cir. 1973).

4 / see e.g. McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792 (1973) .

_5J see e.g. Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969).

6 / see e.g. Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co^, 495

F2d 398 (5th Cir. 1974), certiorari granted 420 U.S.

989.

7 / see e.g. Burns v. Thiokol Corp._, 483 F.2d 300 (5th

Cir. 1973) .

8 / See e.g. Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167

X?d Cir. 1972).

-9-

_9_/ - 10/

technical experts, and trials of substantial duration.

As a practical measure the outcome of a Title VII action

will frequently have a far more profound effect on the

life of the employee and his family than a misdemeanor

prosecution in which he would be entitled to the

assistance of counsel as a matter of constitutional

right. Argersinger v. Hamlin, 407 U.S. 25 (1972). Such

an employee clearly "requires the guiding hand of counsel

at every step in the proceedings" in a case such as this.

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45, 69 (1932).

The effectuation of the national goal of eliminat

ing discrimination "root and branch" requires that viola

tions of Title VII be enjoined, and the victims thereof

made whole, whenever those violations occur. Such litiga

tion is private in form only; in fact the aggrieved party,

often obscure, takes on the mantel of the sovereign and

vindicates "a policy Congress considered of the highest

priority." Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S.

400 (1968). That policy would be easily defeated if

private actions were not initiated in the large number

of cases in which the aggrieved employee is unable to

afford or obtain counsel, or understandably unwilling

to risk much of his meagre savings in the uncertainties

9 / see e.g. United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474

F .2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973).

10/ See e.g. Ford v. United States Steel Corp., 520 F.2d

1043 (5th Cir. 1975).

-10-

of litigation. There are real financial limitations on

the number of contingent fee Title VII cases any individual

attorney or firm can handle, particularly in view of the

many years that may pass between the filing of a complaint

and a final judgment and award of counsel fees. Section

706(e) is an essential part of the Congressional scheme

to enable and "encourage individuals injured by racial

discrimination to seeh judicial relief." Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. at 402. The respon

sibility of the district court in administering section

706(e) is to determine whether the case before it is

one presenting the problem which that section was intended

to resolve, i.e. whether the case is one which, as a

practical matter, will not be pursued without the assistance

of court appointed counsel.

In deciding whether to appoint counsel under

section 706(e) the district court is not generally

authorized to consider the merits of the underlying

claim. The legislative history of this provision, as

the identical language in Title II, indicates that the

sole consideration is whether or not the plaintiff is

able to retain counsel on his own. Senator Humphrey

explained:

Since it is recognized that the main

tenance of a suit may impose a great

burden on a poor individual complain

ant, the Federal court may, on applica

tion of the complainant, appoint an

attorney for him . . . .H /

— --------------------------------

11/ 110 Cong. Rec. 12722 (1976).

-11-

I

Regarding the same provision in Title II, Humphrey stated,

Relief would be possible for persons

experiencing denial of their rights

under Title II who, for financial or

other justifiable reasons, are unable

to bring and maintain a lawsuit.12/

The language of section 706(e) does not authorize

any judicial inquiry into the merits of the claim which

the applicant wishes to pursue. Unlike 28 U.S.C. § 1915,

which expressly contemplates consideration of whether a

proposed forma pauperis action may be "frivolous or

13/malicious", section 706(e) contains no such provision.

A court could not, consistent with section 706(e),

limit appointed counsel to cases it thought likely to

succeed. For the court to consider, in the absence of

counsel, the merits or probable outcome of the action

would be to create the very problem section 706(e) was

adopted to avoid. The statute was intended to assure

that all employees would have the assistance of counsel

before a court considering questions of law and fact;

such a court could not properly undertake to decide

those questions, even tentatively, before, and especially

in considering the desirability of, appointing such counsel.

There may appear on the face of a claim jurisdictional

or other problems likely to lead to its early demise;

to decide those questions in the absence the counsel for

plaintiff, because he was too poor or otherwise unable

12/ 110 Cong. Rec. 12713 (1975).

13/ "(d) The court may request an attorney to represent

any such person unable to employ counsel and may dismiss

-12-

to afford counsel, would perpetuate the type of unequal

treatment section 706 (e) was designed to prevent and

would raise serious problems of due process. If a claim

is indeed fatally defective, the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure provide a variety of methods for its prompt

dismissal; it is these traditional procedures, applicable

to the rich and poor alike, which should be invoked to

dispose of actions that may be frivolous, malicious, or

otherwise insubstantial.

These considerations apply, a fortiori,to

the instant case. The sole reason given by the district

court for refusing to appoint counsel was that the Acting

District Director of the Jackson Office of the E.E.O.C.

had concluded that there was not reasonable cause to

believe that plaintiff was the victim of discrimination.

A 16. But the absence of a finding of reasonable cause

by E.E.O.C. is not grounds for the dismissal of an action

under Title VII. McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411

U.S. 792, 797 (1973); Beverly v. Lone Star Lead Construc

tion Co., 437 F . 2d 1136, 1138-39 (5th Cir. 1971). As Senator

Javits pointed out in the 1964 debates:

13/ cont'd

the case if the allegation of poverty is untrue, or if

satisfied that the action if frivolous or malicious." As

originally adopted in 1892 section 1915 provided, inter

alia, "That the court may request an attorney of the

court to represent such poor person, if it deems the

case 'worthy of a trial' . . .." 27 Stat. 252.

-13-

The Commission may find the claim

invalid; yet the complainant still

can sue . . . the Commission does not

hold the key to the Courtroom door. 14./

If the district court's decision were correct, McDonnell

Douglas and Beverly would apply only to relatively affluent

employees able to retain private counsel. For all other

employees an adverse decision by officials of the E.E.O.C.

would, as a practical matter, be fatal to their claim.

Nothing in Beverly or McDonnell Douglas suggested their

holdings covered only the well to do, and nothing in the

legislative history of Title VII suggests Congress con

templated different rules for employees of different

economic standing.

The two courts of appeals which have considered

this question have both concluded that the appointment of

counsel cannot be denied because the E.E.O.C. concludes

there is not probable cause to believe the allegation of

discrimination. In Harris v. Walgreen's Distribution

Center, 456 F.2d 588 (6th Cir. 1972) the court held:

We agree that denial of counsel is not

mandated by an E.E.O.C. finding of no

probable cause. Indeed, we would regard

a record which showed this as the sole

reason for denial of counsel as founded

on error.

456 F.2d at 590. Similarly the Seventh Circuit ruled

that such a finding would not justify refusing to appoint

counsel under section 706(e). Robinson v. Western Electric

Co., 3 EPD f 8240 (7th Cir. 1971).

IdS 110 Cong. Rec. 14191 (1975).

-14-

III. Procedure on Remand

On remand the district court must consider anew

appellant's request for appointed counsel. Although

section 706(e) has been the law for a decade, the district

courts in this Circuit, as elsewhere, have not developed

clear and effective procedures for handling requests for

counsel under Title VII. For this reason, and to minimize

the need for further appeals on that issue in this case,

it would be appropriate for this Court to clarify the

standards to be applied by the district court on remand.

The economic circumstances which would warrant

the appointment of counsel must be measured with regard

to the underlying statutory purpose. Aggrieved employees

need not contribute "the last dollar they have or can

get, and thus make themselves and their dependents wholly

destitute." Adkins v. duPont Co., 315 U.S. 331, 340

(1948). In providing for private enforcement of Title VII,

Congress understood that an ordinary worker could not be

expected to risk his life savings or mortgage his home

to finance a lawsuit, no matter how meritorious his claim.

The assistance authorized by section 706(e) is not limited

to paupers, for such a limitation would exclude the employees

of modest means who could not reasonably be asked to imperil

their economic security by undertaking to bear the substan

tial cost of a Title VII action. Petete v. Consolidated

Freightways, 313 F.Supp. 1271, 1272 (N.D. Tex. 1970). A

-15-

plaintiff cannot be expected to contribute »ore to the

financing of such an action than a reasonably prudent

man in similar circumstances would choose to spend, mind

ful of the needs of himself and his family and of the

unavoidable uncertainties of such litigation. To the

extent that such a contribution would be inadequate to

bring and maintain a Title VII action, assistance under

section 706(e) is required. If on remand, a question is

raised as to whether appellant is affluent enough to pay

for his own counsel, the assistance of the court can

only be denied if it is shown by clear and convincing

evidence that such aid is unnecessary.

The district courts may employ a variety of

methods to finance the appointment of counsel, not all^

of which would involve the expenditure of court funds.

The court may, in an appropriate manner, attempt to

persuade counsel to represent the applicant without

any fee other than what may be awarded under section 706(e)

if plaintiff prevails. The court could provide, in the

appointment, that the size of any counsel fee awarded

against the defendant would be augmented because the

case had been assigned by the court. The order might

provide that any attorney's fee awarded against the

TT/ The district court in the instant case correctly recognized

it£ authority to order such expenditures ̂ A 16. _cleariy

Wilson, 277 F.Supp. 271, 274 (N-D. Cal. x Q^taile^ hy section

understood that such expendi u proposed an amendment706(e). Senator Thurmond unsuccessfully P ™ P ° = f functlon of the

£ a » £ n f t

^ r t h e r S r e ! « f i d of Title VII

Cs —

defendant would be computed on the usual basis, with the

court paying the attorneys out-of-pocket expenses and/or

overhead if the case were lost. The assignment could

provide for a fee to be computed on a pre-determined

basis and paid by the court, with any awarded counsel fee

in excess of this amount to be remitted to the court. In

a case of significant length or consuming substantial

amounts of time within a short period, an interim award

of fees or expenses may be proper. Bradley v. School

Board of the City of Richmond, 416 U.S. 696, 773 (1973).

The appropriate method of compensation should be fashioned

by the district court in the light of local conditions to

assure that aggrieved employees are represented by experienced

counsel without imposing an inappropriate financial burden

on attorneys who in many cases may already be handling a

significant number of civil rights actions on a pro bono

or contingent fee basis.

In selecting counsel for appointment the district

court should bear in mind several considerations. Because

the issues in these cases may be or become matters of sub

stantial public controversy, and because questions of law

which will arise may well affect the interests of other

employers, the court should assure itself that the attorney's

15/ cont'd-

of the substitute the proposed authority of the Court to

appoint an attorney for a complainant in suits alleging

denial of equal employment opportunities." 110 Cong.

pe. i4196 (1975). Such expenditures clearly fall within

the appropriation for "miscellaneous expenses" contained

in the Judiciary Appropriations Acts. See 86 Stat. 1127;

1974 U„S. Code Congressional and Administrative News, 1372.

-17-

advocacy is not likely to be inhibited by concern with

the competing interests of other clients, fear of unpopu

larity, or in equivocal attitude toward the statutory

goal of equal opportunity. An effort should be made to

identify attorneys who have significant experience with

the highly complex issues that may arise in a Title VII

case, especially where a class action is involved. Due

deference should be given to any preference on the part

of the employee, especially where grounded on a good

faith concern as to the comparative attitudes of attorneys

towards his minority group or the purposes of Title VII.

The district court on remand should make a

reasonable effort to locate an attorney who would welcome

the assignment of a case such as this. In the field of

civil rights, unlike an ordinary action in contract or

tort, certain attorneys may be personally indifferent or

hostile to the underlying statutory policies. To avoid

saddling an indigent plaintiff with such counsel, the

court should look first to members of the bar who have

previously undertaken voluntarily to represent civil

rights litigants. If, however, no attorney can be found

agreeable to being assigned as counsel, the court can

and must order an appropriate attorney to represent

appellant. Unlike § 1915(d) which merely permits the

court to "request an attorney to represent any such person

unable to employ counsel," section 706(e) entails the

power to "appoint" an attorney Congress expressly re

jected a proposal to limit section 706(e) by providing

18-

that the court could only make an appointment "with the

16/consent of such attorney." Section 706(e) was adopted,

in part, to give the court the power to require an attorney

to represent a plaintiff when no known attorney will do so

voluntarily; when the court cannot find such a volunteer,

that power must be exercised. If, on the other hand, a

potential plaintiff locates an attorney who would like

to handle the case but declines to do so without a court

appointment, the Court in selecting counsel should give

appropriate consideration to that expression of interest..

In carrying out its responsibilities under

section 706(e) the court must follow procedures which

reflect the fact that the plaintiff is, by definition,

without counsel and often of limited education or

1z/

familiarity with legal matters. If a plaintiff indicates

to the court, directly or through the clerk of the court,

his desire for assistance in obtaining counsel, the courc

must act. That assistance cannot be conditioned on anything

other than the possession of a Right to Sue letter and the

making of an appropriate request. Where the court needs

additional information from the plaintiff to shape its

response, that information should be sought in an efficacious

16/ 110 Cong. Rec. 14201 (1975). The proposed amend

ment by Senator Ervin would have applied to appointments

under Titles II and VII. See also 110 Cong. Rec. 14462.

(Remarks of Sen. Holland) (1975).

17/ This includes, of course, any person who has received

a Right to Sue letter but not yet filed a complaint.

Such an indication should normally be deemed to con

stitute the commencement of a civil action for the purposes

and informal manner unlikely to intimidate a layman.

If the court believes there is a reasonable possibility

that plaintiff could retain counsel on a contingent fee

or other basis, without resort to a section 706(e) appoint

ment, the court should offer appropriate assistance in

12/finding such counsel. Should such efforts prove unsuc

cessful, and the court thus conclude that the plaintiff

is unable for financial or other reasons to retain counsel

other than through an appointment under section 706(e),

such an appointment must be made. In administering section

706(e) the court has an affirmative responsibility to

carry out the congressional policy that any aggrieved

employee who wishes to pursue his claim in court shall

have the assistance of counsel.

18/

17/ cont'd.

of the deadline established by 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(e).

Huston v. General Motors Corp., 477 F.2d 1003 (8th Cir.

1973) .

1_8/ It sould be inappropriate, under ordinary circumstances,

for the court to require the filing of oaths, statements,

inventories of assets or affidavits to be prepared by the

plaintiff. Edmonds v. E.J. duPont de Nemours & Co. , 315

F.Supp. 523, 526 (D. Kan. 1970).

19/ The court is far more likely than the plaintiff

1 know which attorneys in the community have experience

i Title VII cases and have in the past indicated a

willingness to handle such matters. The court might

provide this information to plaintiff or communicate

directly with the attorney involved; it should not impose

or. plaintiff the unnecessary burden of approaching large

numbers of attorneys at random merely to deminstrate the

predictable futility of such an undertaking.

-20-

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons the order of the district

court of September 18, 1975, should be reversed and the

case remanded with instructions to appoint counsel to

represent plaintiff.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

MELVYN LEVENTHAL

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

RONALD REID WELCH

FRANK R. PARKER

233 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

-21-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 2nd day of

February, 1976, I served copies of appellant's

brief and appendix on appeal on counsel for respondent

by depositing them in the United States mail, first class

postage prepaid, addressed to Wayne Easterling, Esq., 5th

Floor, Citizens Bank Building, Hattiesburg, Mississippi

39401; Frank Nix, Esq., 1200 C & S National Bank Building,

Atlanta, Georgia 30303 and Marleigh Dover Lang, Esq.,

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2401 E. Street,

N.W. Washington, D.C. 20506.

Eric Schnapper