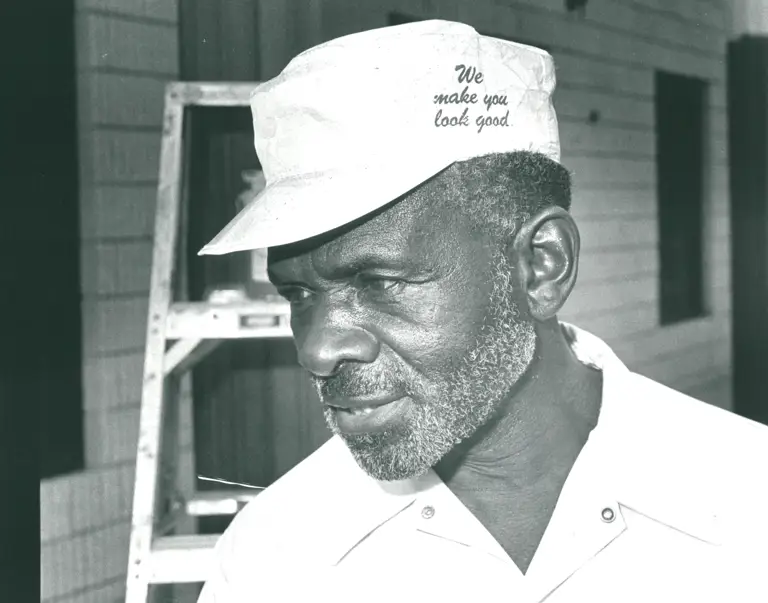

Haskins v. Wilson County, North Carolina, 1982, undated - 6 of 8

Photograph

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Photograph Collection, Political Participation. Haskins v. Wilson County, North Carolina, 1982, undated - 6 of 8, 1982. 4798f026-bd54-ef11-a317-6045bdd88b0e. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a90650fa-500c-4d6d-9017-08d724bfeeac/haskins-v-wilson-county-north-carolina-1982-undated-6-of-8. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

X-TIKA:Parsed-By org.apache.tika.parser.DefaultParser org.apache.tika.parser.gdal.GDALParser X-TIKA:Parsed-By-Full-Set org.apache.tika.parser.DefaultParser org.apache.tika.parser.gdal.GDALParser Content-Length 4994463 Content-Type image/jpeg