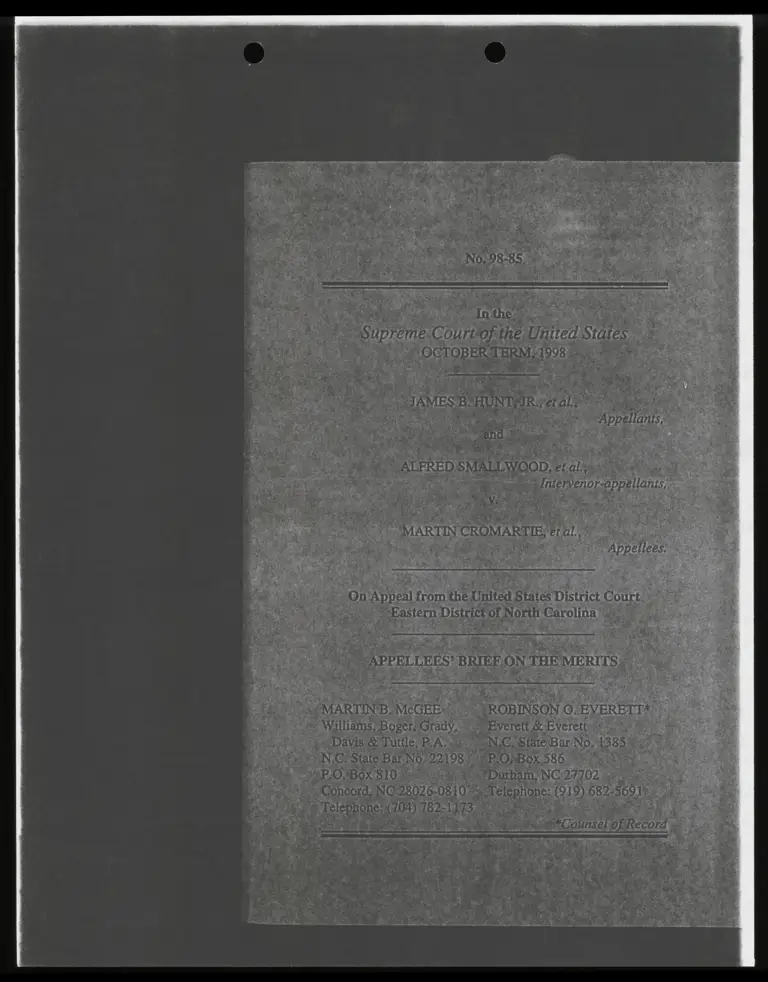

Appellees' Brief on the Merits

Public Court Documents

December 8, 1998

59 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Appellees' Brief on the Merits, 1998. 8b52cd06-d90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a9444f30-84cd-45b6-a5d9-26fd809c9eae/appellees-brief-on-the-merits. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

o

I

Dd

verett & Everett:

to

i

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Should the constitutionally mandated principles of

Shaw v. Reno be reaffirmed and fully enforced in the

review of a redistricting plan required in order to

remedy past violations of equal protection?

In granting summary judgment did the district court

properly decide that the bizarrely shaped, race-based

District 12 failed to meet the requirements of Shaw v.

Reno?

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented . vei thc devnisinsndin ss sve gees 1

Table OF ANNOFIHES .'.. . ois vers inna nse wid mga ar v

Statementofthe Case... 0 cc vo oh vu imiis 29 1

A Brief History of North Carolina’s Racial

Gerrymandering «he deidecua cons cnn rnin same ss 1

Summary of ArgUMENt . i. oc. cin vv des Sd pra Sai 8

ARGUMENT -

L The Constitutionally Mandated Principles

of Shaw v. Reno Should Be Reaffirmed

and Given Full Bffect'. . .5.... i. i000, de 11

Shaw v. Reno Properly Applies the

Equal Protection Clause to Racial

Gerrymanders.. . «a vue. sn ad Haga vies 11

Shaw v. Reno Applies Not Only to

Majority-Minority Districts .................. 14

The Continuing Evasion of the

Principles of Shaw v. Reno Should

NotBeTolerated ..... 5.0. an cain ans 17

The Shaw v. Reno Requirement of

a “Predominant” Racial Motive Should

Be Conformed to Other Equal Protection

Precedents ui iis a aie snigieies » i as 4 19

111

A Remedial Plan for Violations of

Shaw v. Reno Requires Especially

Demanding Judicial Scrutiny ................. 20

The District Court Properly

Granted Summary Judgment That

North Carolina’s Twelfth Congressional

Disirict is Unconstitutional .......0........0.. 23

The Shape and Demographics of

North Carolina’s Twelfth

Congressional District Show

Unmistakably that Race Was the

Predominant Motive for Its Design ............ 25

i. Race Dictated the Twelfth

District’s Bizarre Shape and

Lackof Compactness . i. 0. Lo. 25

2. Contiguity was Subordinated

to Racial Considerations .............. 30

3. Political Subdivisions and

Actual Communities of Interest

Were Subordinated to Racial

Considerations 774, ni gh r ah Reon 30

District 12 Cannot Be Justified by

Means of a Spurious Claim That It

Was Created with a Political,

Rather than Racial, Motive .................. 32

The Affidavits of Legislators McMahan

and Cooper Do Not Create Any

Material Issue of Fact... . ... Foo oan vo 38

iv

D. The District Court Had No Occasion

to Discuss Strict SCrLINY 5. rv dee aes i 43

E. The Summary Judgment Also was

Properon Other Grounds ......... .. canis 45

COMCIUSION ti ho EB Ss sae dnt ale senses vu ns u's in 48

\%

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Abrams v. Johnson, 117 S.Ct. 1925 QI997) ii ory Las 22

Aleyska Pipeline Serv. Co. v. U.S.E.P.A., 856 F.2d

309 O.C. Cir. 1988) ve = J Si oath Sl 24

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242

(1086) te ta LL BE aa a 24

Bread Political Action Comm. v. Fed. Election

Comm. 455 U.S. 3771982)... ol i oi ou 39

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

48301054) oti EL A 16

Brown v. Board of Education, 892 F.2d 851

(OCI 1080) oo. a ae Son 21

Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590 (1975) ............... 21

Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996)... ...:..: 0: passim

D & W, Inc. v. City of Charlotte, 268 N.C. 577

(A900Yeh it al ih oh, ray a 38

Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526

(Oy re EL arn 21

Diaz v. Silver, 978 F. Supp. 96 (E.D.N.Y. 1997),

Ad US SCL 36D: el 49

Vi

Drum v. Seawell, 250 F. Supp. 922

MD.N.C.A980Y:0. is. ah tahini shit sss annd 18

Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200 (1979) ........... 21

Empire Distribs. of N.C. v. Schieffelin & Co.,

G79 F.Supp 541 (W.DN.C. 1987) .....o ines davis 39

Hays v. Louisiana, 839 F. Supp. 1188 (W.D.La.

3 5 Er SUR As Et IE DET ee RE 1

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985) ........... 19

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983) ............. 28

Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 117 S. Ct. 2186

CVOOTY fetes sips vei Fs 2 adie nt nea vise din vs Ton 15, 27, 45

Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp.,

AIS U.S 574C18806): coc: ..... vnvn sash wis JOT 23

Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995) ........... passim

Milk Comm'n v. National Food Stores, 270 N.C.

32301067)... co Be Se en kh an we ds 39

Mt. Healthy City Sch. Dist. Bd. of Educ. v.

Doyle, 429 U.S. 278 (1977) iv vii oi wu Bins wa alii 19

Pope v. Blue, 809 F. Supp. 392 (W.D.N.C. 1992),

aff'd. 506 US. 80LA09) =.) rin. ili BN 2

Regional Rail Reorganization Act Cases, 419

US I02€1974) .... ih ons so 5 i iis te ii wives 39

vii

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ......... 14, 18, 20

Ross v. Communications Satellite Corp., 759

Fd IS (Cir 1088 vid te cosas ao 24

Ross v. Houston Independent Sch. Dist., 699

Fd 2083 Cir 1983): oo Ss So 21

School Bd. of the City of Richmond v. Baliles, 829

F2d 1308 (AE Cir. A087): vied tv iii 4 21.22

Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996) .............. passim

Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F. Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994),

reversed 317 U.S. 899(1996) ...... ..... 5. on ui le 6

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630(1993) onus ls passim

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402.U.S. L(1971) ... . ct i aE 21

Taylor v. Alabama, 457 U.S. 687 (1982) .............. 2]

Taylor v. Ouachita Parish Sch. Bd., 648 F.2d 959,

(CI A1931). os. re ae a TE LE 21

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) ............ 14

United States v. Lawrence County Sch. Dist.,

TOO F.2d 1031 (50 Cir, 1986)... .- cus. 0 a oR, 21

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Dev.

Corp. 429.US. 252 (1977)... 5. a0... us 2,19, 20, 46

Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535 R370 PRON A 22

viil

Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963) .... 21,23

CONSTITUTION AND STATUTES

U.S. Constitution, Amendment XIV... o.oo 13

Fed R.CIV.P. SOIC) onl i sands dive won vin ites 9,23

N.C. Gen. Stat. Section 183-201(2) . ..n . vv desu vin vis ain 7

N.C..Sess Laws 1998-2 . Si... Tu vino ne vileininiva nn sie sis 7

OTHER AUTHORITIES

11A Charles A. Wright, et al., Federal Practice

and Procedure Sec. 2048 hn RE ce ah 24

Richard H. Pildes & Richard G. Niemi,

Expressive Harms, “Bizarre Districts,

and Voting Rights: Evaluating

Election-District Appearances After

Shaw v. Reno, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 483 (1993) ......... 25

»

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A Brief History of North Carolina’s Racial

Gerrymandering

This appeal is yet another of the never-ending efforts by

the appellants and their allies to perpetuate racial gerrymanders

in North Carolina. To that end, they have employed specious

arguments,’ posed undue procedural objections,” and used “post

hoc rationalizations” and euphemisms to mask racial motives.’

'For example, in Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996) (hereinafter

“Shaw IT”), the Court described as “singularly unpersuasive” the State’s

claim that the Twelfth District was “narrowly tailored.” Id. at 917.

Thus, despite the clear intent of this Court’s opinion in Shaw v.

Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) (hereinafter “Shaw I’), the State continued to

claim that the plaintiffs in Shaw had no standing under the Equal Protection

Clause because they were white; and a similar argument has now been

advanced in the amicus brief of the American Civil Liberties Union. ACLU

Br. 14-16. Moreover, in the present appeal, appellants initially asserted that

an order in the Shaw litigation which approved the 1997 redistricting plan

precluded the claim for relief of Cromartie and his fellow plaintiffs — even

though (a) appellants did not allege preclusion in their answer or otherwise

assert it until filing their appeal; (b) no privity existed to support claim

preclusion or collateral estoppel; and (c) the preclusion argument was

forestalled by the language of the district court’s order in Shaw. This

contention, which was one of three advanced in the appellants’

jurisdictional statement, has apparently now been abandoned, and it is also

disavowed by the amicus brief of the United States.

*“Post hoc rationalizations” was the term used by the three-judge

district court in Hays v. Louisiana, 839 F. Supp. 1188 (W.D. La. 1993) to

characterize race-neutral defenses of Louisiana’s racial gerrymanders by

experts, some of whom also defended North Carolina’s racial gerrymanders

in the Shaw litigation. “Minority-opportunity” district was a euphemism

used in oral argument to defend the racially gerrymandered Texas districts

that were the subject of Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996).

2

The State’s history of stonewall defense of its racial

gerrymanders makes its contentions on this appeal seem

especially hollow.

To analyze properly the present appeal requires an

examination of the history of North Carolina’s racial

gerrymandering, which begins with a redistricting plan

adopted in 1991 that contained only one majority-minority

district. After the Department of Justice denied preclearance

pursuant to its “maximization policy,” that plan was replaced

in January 1992 by a redistricting plan that had two majority-

black districts. When this plan first was attacked by

Republicans as a political gerrymander,’ the State claimed that

its irregular shape reflected the demands of the Civil Rights

Division. When the Shaw plaintiffs attacked the plan a few

weeks later because it was a racial gerrymander, the State never

denied that it was race-based. Instead, the racial gerrymander

was defended — even in argument before this Court — as being

race-based for benign reasons and therefore not in violation of

the Equal Protection Clause. Moreover, the State insisted that

the Shaw plaintiffs lacked standing to make an Equal Protection

claim because they all were white.

When this Court rejected these defenses in Shaw I and

remanded the case for trial, the State adroitly changed its

“In Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Dev. Corp., 429

U.S. 252,267 (1977), the Court noted that “the historical background of the

decision is one evidentiary source, particularly if it reveals a series of

official actions taken for invidious purposes.”

>See Pope v. Blue, 809 F. Supp. 392 (W.D.N.C. 1992), aff'd, 506

U.S. 801 (1992).

3

position and contended that the 1992 plan actually was not

race-based. At trial and on appeal, reliance was placed on

novel concepts — such as “functional compactness” — to

establish that the two majority-black districts had been created

because of factors other than race and therefore the principles

enunciated in Shaw I had not been violated. Fortunately, the

State’s “post hoc rationalizations” were rejected in Shaw II°

and further use of the 1992 plan was prohibited. However,

despite strenuous efforts by the Shaw plaintiffs to persuade

either the General Assembly or the district court to put a

constitutional plan into effect in time for the 1996 elections,

those elections took place in November 1996 pursuant to the

same “bizarre” plan that this Court had held unconstitutional

several months earlier in Shaw II.” On March 31, 1997,

immediately before the deadline set by the district court, the

General Assembly enacted a new redistricting plan, which was

then precleared by the Civil Rights Division. Despite a

*These rationalizations were impossible to reconcile with the shape

and demographics of the two majority-black districts, which linked large

concentrations of African-Americans by narrow “white corridors,” utilized

“point contiguousness,” split numerous precincts along racial lines, and

violated nearly every race-neutral principle of redistricting. See Shaw II.

"Ironically, in the Texas redistricting litigation — which had

commenced some months after suit was brought in North Carolina and

which was decided by this Court at the same time as Shaw II — the three-

judge district court put a new plan into effect for the 1996 election. Of

thirty congressional districts in Texas, the new plan altered thirteen districts

— more than the entire number of districts in North Carolina. Yet North

Carolina’s legislature considered it impossible to enact a new plan for the

1996 elections and, by divided vote, the district court declined to intervene.

4

statement of opposition by the Shaw plaintiffs,’ the district

court approved the plan.

In Shaw II this Court ruled only on the challenge to the

Twelfth District of the 1992 plan because none of the plaintiff-

appellants lived in the First District. Therefore, Martin

Cromartie and two other residents of the First District filed a

complaint on July 3, 1996, which alleged that this district also

violated the Equal Protection Clause. Their action, however,

was stayed by consent to await enactment by the General

Assembly of a new redistricting plan. After the district court in

Shaw approved the 1997 plan only on a limited basis,” an

amended complaint was filed in the Cromartie action. See

Joint Appendix (hereinafter “J.A.”) 7. It sought a temporary

and permanent injunction against use of the 1997 plan. Relying

on the data available through the General Assembly’s public

access computer — data which had been submitted to the

Department of Justice in the General Assembly’s effort to

obtain preclearance for the 1997 plan — the amended complaint

not only attacked the “new” First District but also alleged that

the Twelfth District in the 1997 plan was composed of parts of

The five Shaw plaintiffs all lived in Durham County, which the

General Assembly had removed from the Twelfth District. Under Shaw II

they now lacked standing to challenge that district, although they asserted

that it still was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

’See Memorandum Opinion in Shaw v. Hunt, in Appendix to

Jurisdictional Statement (hereinafter J.S. App.) 159a. The Court

specifically stated that because of the “dimensions of this civil action as that

is defined by the parties and the claims properly before us . . . we only

approve the plan as an adequate remedy for the specific violation of the

individual equal protection rights of those plaintiffs who successfully

challenged the legislature’s creation of former District 12. Our approval

thus does not — cannot — run beyond the plan’s remedial adequacy with

respect to those parties and the equal protection violation found as to former

District 12.” J.S. App. 167a.

5

six counties'® and that each of those counties

was divided along racial lines and for a

predominantly racial motive. Of Mecklenburg

County’s black population, 84% was placed in

the Twelfth District and 16% in the Ninth; but

of its white population 27% was placed in the

Twelfth District and 73% in the Ninth. Of

Forsyth County’s black population, 65% was

placed in the Twelfth District and 35% in the

Fifth District; but of its white population, 8%

was placed in the Twelfth District and 92% in

the Fifth. Of Guilford County’s black

population, 76% was placed in the Twelfth

District and 24% in the Sixth; but of its white

population, 25% was placed in the Twelfth

District and 75% in the Sixth. Of Iredell

County’s black population, 63% was placed in

the Twelfth District and 37% in the Tenth; but

of its white population 37% was placed in the

Twelfth District and 63% in the Tenth. Of

Rowan County’s black population, 66% was

placed in the Twelfth District and 34% in the

Sixth; but of its white population, 23% was

placed in the Twelfth District and 77% in the

Sixth. Of Davidson County’s black population

80% was placed in the Twelfth District and

20% in the Sixth District; but of its white

population, 49.6% was placed in the Twelfth

District and 50.4% in the Sixth District. The

Twelfth District is the only congressional

district which under the March 1997 plan

"Some plaintiffs had been added who lived in District 12 and

therefore had standing under Shaw II.

6

contains no county which is not divided."

After the State defendants had answered, the three-

judge district court — of which only one member, Chief Judge

Richard L. Voorhees, had participated in the Shaw litigation"?

— conducted a hearing on March 31, 1998. Soon thereafter it

granted summary judgment for the plaintiffs as to the “new”

Twelfth District; and the court permanently enjoined use of the

1997 plan for any primary or general election.” However, the

court refused summary judgment for either the plaintiffs or

defendants as to the 1997 plan’s First District. The defendants

then unsuccessfully sought a stay from the district court and

thereafter from this Court. See Hunt v. Cromartie (No. A-793),

118 S. Ct. 1510 (1998). Later, still another fruitless effort was

made by the State to delay the effect of the injunction as to six

of the congressional districts — namely, the First District and

five others in the eastern part of North Carolina.

The district court allowed the General Assembly an

opportunity to enact still another plan — which was forthcoming

See J.A. 16-17. As the amended complaint also noted,

Mecklenburg and Guilford Counties — two of North Carolina’s most

populous counties — had never been in the same congressional district from

1793 until the 1992 redistricting plan was enacted; nor had Mecklenburg

been in the same district with Forsyth County — another populous county —

during any of this same period. See id. See also the corresponding

admissions in appellants’ answer. Id. at 30-31.

During the Shaw litigation Chief Judge Voorhees consistently

dissented from rulings which supported North Carolina’s flagrant racial

gerrymander. See, e.g., Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F. Supp. 408, 477 (E.D.N.C.

1994) (Voorhees, C.J. dissenting), reversed by Shaw II.

3The 1997 plan was never used in an election. The 1992, 1994,

and 1996 elections were conducted under the 1992 plan while the 1998

election took place under the 1998 plan.

7

in May 1998. Under this plan, the First District was left

unchanged; but instead of splitting six counties, the Twelfth

District now contained one entire county and split only four.

The percentage of African-Americans in this district was also

reduced from 46.67% to 35.58%, although the Twelfth District

stll linked two major urban concentrations of African-

Americans — one in Charlotte and the other in Winston-Salem.

The 1998 plan contained a unique provision that it would be

“effective for the elections for the years 1998 and 2000 unless

the United States Supreme Court reverses the decision holding

unconstitutional G.S. 163-201(a) as it existed prior to the

enactment of this act.”"*

The plaintiffs informed the district court that they

opposed the 1998 plan because — even though an improvement

on its predecessors — the plan still was an unconstitutional

racial gerrymander. However, the court authorized the State to

use this plan for the 1998 congressional primaries — which were

deferred until September — and for the general election on

November 3, 1998. See J.S. App. 175a. The district court

prescribed a discovery schedule in preparation for a trial as to

the constitutionality of the First District and stated that it also

would consider any additional evidence that plaintiffs might

offer with respect to the Twelfth District’s unconstitutionality.

After appellants filed their jurisdictional statement, the district

court, by consent of all the parties, stayed proceedings to await

the outcome of this appeal. Meanwhile, Cromartie and the

other appellees in this case appealed the order which allowed

“See N.C. Sess. Laws 1998-2, enacted May 21, 1998 (emphasis

added), which is discussed in Appellees’ Motion to Dismiss or, in the

Alternative, to Affirm at 10. Under this unique provision, if this Court

“reverses the decision” below, the more race-based 1997 plan will come

into effect for elections in the year 2000, and the Representatives elected on

November 3, 1998 will have their districts changed.

8

the 1998 plan to be used. By their appeal in Cromartie v. Hunt

(No. 98-450), they seek resolution of several issues also present

in this appeal.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The principles established by Shaw v. Reno should be

given full effect — not overturned, as some of the amici have

urged, or unduly limited, as appellants and all their amici seek.

To subject race-based congressional districts to strict scrutiny —

as required by Shaw and the Equal Protection Clause — assures

that racial stereotypes will not mar the electoral process, that

members of Congress will not feel an obligation to represent

only voters of their own race, and that voters of one race will not

feel that they lack a voice if they are represented in Congress by

someone of another race. Shaw has enhanced the confidence of

voters in the electoral process. Fears that it might diminish

racial diversity proved groundless."

Because application of the principles of Shaw v. Reno

produces a more meaningful electoral process and reduces the

incentive for racial stereotyping and polarization, those

principles should be vigorously applied, rather than left

unenforced. Thus, contrary to the position taken by the General

Assembly in enacting and defending the 1997 plan, race-based

'*Contrary to predictions by some Shaw critics, every African-

American who had been originally elected to Congress from a majority-

minority district was re-elected in redrawn districts — except for

Representative Cleo Fields, who, instead of seeking re-election, ran for

governor of Louisiana. In North Carolina, the two African-Americans,

Melvin Watt and Eva Clayton, who had been elected three times under the

1992 plan, were handily reelected on November 3, 1998 even though each

ran in a district with a lower percentage of black voters than before. Such

results demonstrate that African-American candidates do not need a

majority-black district to be elected if they campaign vigorously to gain

support of all voters, rather than only voters of their own race.

Wy

.

AV

S

R

E

Lo

T

e

SR

T

R

ER

SE

R

e

b

9

districts — whether or not majority-minority — must be eliminated

unless they pass the test of strict scrutiny. Likewise, the Court

should not allow evasion of the Shaw requirements by the resort

to amorphous concepts like “functional compactness” and by the

artful phrasing of legislative history and affidavits. Especially

in dealing with a remedial plan that the General Assembly

purportedly designed to correct the past constitutional defects,

the Court should insist that all “vestiges” of the racial

gerrymander be eliminated in order to assure that public

confidence in the electoral process is restored and that judicial

rulings are not circumvented. State appellants’ plea for further

guidance 1s surprising because the history of racial

gerrymandering in North Carolina reveals that they have

consistently disregarded guidance that has already been

provided.

The appellants and amici contend that the district court

failed properly to apply Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56(c) in

ruling on the motions for summary judgment submitted by

plaintiffs and defendants. The language of the court’s

Memorandum Opinion refutes this argument. The district

court’s opinion marshals the uncontroverted material facts to

demonstrate conclusively that the 1997 version of District 12

was the result of a predominantly racial motive on the part of the

legislature. Although “appearances” are not conclusive as to the

motive for drawing a particular district, the shape of the Twelfth

District, see map, J.S. App. 59a — especially when juxtaposed

against the race-based Twelfth District of the 1992 plan, see

map, J.S. App. 61a — is strong evidence as to the racial motive

for the plan. The demographics of the district and its violation

of traditional race-neutral principles are additional evidence.

Finally, the history of the plan — including some significant

contradictions between the plan and the stated reasons for its

enactment — constitutes still further evidence of the racial

motive. The uncontroverted evidence was more than enough to

10

warrant summary judgment for the plaintiffs.

Although the issue was not raised in the Jurisdictional

Statement or in the State appellants’ brief, intervenor-appellants

and some of the amici contend that the district court should have

engaged in “strict scrutiny” of the race-based District 12.

Nothing in the record suggests that the district was created in

response to a “compelling governmental interest” or that it

embodied “narrow tailoring.” Indeed, for appellants to claim

that the district met strict scrutiny would be inconsistent with

their insistence that there had been no racial purpose in its

design. Moreover, incumbent protection and maintaining

partisan balance — the claimed reasons for the 1997 plan - could

not be considered “compelling” governmental interests; and to

assert that the “new” Twelfth District was “narrowly tailored”

would defy this Court’s treatment of its predecessor in Shaw I1.'°

Even if the district court had not found specifically from

the uncontroverted facts that race was the General Assembly’s

predominant motive for drawing District 12, the summary

judgment was proper. Approval of a remedial plan requires

close judicial scrutiny to assure that any unconstitutional taint of

the replaced plan has been eliminated. When, as with North

Carolina’s District 12, the “new” district admittedly preserves

the “core” of the original district, retains many “appearances” of

that district, seeks to guarantee reelection of incumbent elected

from the replaced district, and violates “traditional districting

principles,” it cannot be approved.

The General Assembly’s later enactment of the less race-based,

more compact 1998 plan for the same claimed purpose of incumbent

protection and maintaining partisan balance also indicates that these stated

purposes are disguises for a predominant racial motive.

11

ARGUMENT

I. THE CONSTITUTIONALLY MANDATED

PRINCIPLES OF SHAW V. RENO SHOULD BE

REAFFIRMED AND GIVEN FULL EFFECT.

A. Shaw v. Reno Properly Applies the Equal Protection

Clause to Racial Gerrymanders.

Some of the amici, such as the American Civil Liberties

Union, wish this Court to overrule Shaw v. Reno in anticipation

of “the millennium census and the next round of redistricting.”

ACLU Br. 4. Apart from the importance of stare decisis in

assuring respect for our legal system,” the overruling of this

landmark decision would be properly perceived as a dismaying

step backwards. Public confidence in the integrity of the

electoral process would be destroyed by such a repudiation of

the Court’s perceptive observation in Shaw I that:

[W]e believe that reapportionment is one

area in which appearances do matter. A

reapportionment plan that includes in one district

In Vera, Justice O’ Connor wrote:

Our legitimacy requires, above all, that we adhere to stare

decisis, especially in such sensitive political contexts as

the present, where partisan controversy abounds.

Legislators and district courts nationwide have modified

their practices — or, rather, reembraced the traditional

districting practices that were almost universally

followed before the 1990 census — in response to Shaw

I. Those practices and our precedents, which

acknowledge voters as more than mere racial statistics,

play an important role in defining the political identity of

the American voter.

517 U.S. at 985.

12

individuals who belong to the same race, but

who are otherwise widely separated by

geographical and political boundaries, and who

may have little in common with one another but

the color of their skin, bears an uncomfortable

resemblance to political apartheid. It reinforces

the perception that members of the same racial

group — regardless of age, education, economic

status, or the community in which they live —

think alike, share the same political interests, and

will prefer the same candidates at the polls.

Shaw I, 509 U.S. at 647. A license would be granted to

resurrect the distorted race-based districts for which Shaw

spelled doom." Apparent approval would be given to the

polarizing view held by some legislators that their primary

responsibility is to represent voters of their own race." If Shaw

I had not been decided, the Civil Rights Division would have

continued to enforce its “maximization policy,” which for

Section 5 preclearance required states to create majority-black

districts in any way possible — no matter how contrary to

traditional redistricting principles. See Miller v. Johnson, 515

'* Among the bizarre districts for which Shaw v. Reno sounded a

death knell were North Carolina’s “I-85 district,” Louisiana’s “mark of

Zorro district,” Georgia’s “march to the sea district,” New York's

“Bullwinkle district,” and Texas’s “Mogllianni painting districts.”

“Representative Melvin Watt, an African-American, who in 1992

and thereafter has been elected to Congress from District 12, provided an

example of this view when he testified in the trial of Shaw v. Hunt that

“representing a district that you are consistent with in your philosophies

allows you to be consistent in voting your conscience without buckling

under or catering, as you said my statement said, to other interests that may

not predominate in my district [such as the ‘business or white community.’]”

861 F. Supp. 408, 478, n.5 (E.D.N.C. 1994) (Voorhees, C.J. dissenting)

(emphasis and brackets in original).

13

U.S. 900, 917 (1995). Retreating from Shaw would pave the

way for the Department of Justice once again to impose its will

unduly on legislatures engaged in the next decade’s redistricting.

Some amici also attack the holding of Shaw II that white

plaintiffs have standing to complain about majority-black

districts. They fail to recognize that a Shaw claim is

“analytically distinct” from a vote dilution claim, Miller, 515

U.S. at 911 (citation omitted); that the Fourteenth Amendment

provides that “no state shall deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws” (emphasis added);

and that therefore the race of the plaintiff who brings a Shaw

challenge is immaterial.”

The principles of Shaw have also been attacked on the

ground that their rigorous application will result in burdensome

litigation. However, this criticism fails to take into account that

much of the past litigation was caused by the Civil Rights

Division’s abuse of its preclearance authority. Cf. Miller, 515

U.S. at 917. Moreover, now that — “in response to Shaw I’ —

legislators and districts courts nationwide have “reembraced the

traditional districting practices that were almost universally

followed before the 1990 census,” Vera, 517 U.S. at 985, the

occasion for litigation has been greatly reduced. If North

Carolina — where Shaw arose — had done the same, there would

have been no occasion for the present appeal. It is the State’s

*Contrary to the implication in the ACLU brief at 12, nothing in

Shaw limits its application to majority-black districts. A majority-white

district is equally subject to attack if race was the predominant motive for

its boundaries — for example, if a district was intentionally “bleached.”

Indeed, in the pending case of Daly v. High, No. 5:97-CV-750-BO

(E.D.N.C.), the complaint attacks not only North Carolina’s two majority-

black districts but also some majority-white districts.

14

evasion of Shaw that has created the problem and generated

litigation. In short, those who create the need for litigation by

their non-adherence to Shaw have no standing to complain about

the resulting burden on the courts. This evasion should not be

tolerated by this Court.”! Furthermore, the purported dilemma

of legislators caught between the requirements of Shaw and the

threat of Section 2 litigation has been exaggerated. Legislatures

which adhere to traditional districting practices will have few

problems so long as they do not divide “geographically

compact” groups of minority voters.

B. Shaw v. Reno Applies Not Only to Majority-Minority

Districts.

Consistent with its refusal to accept the legitimacy of

Shaw in devising the 1997 plan, the North Carolina General

Assembly took the position that Shaw applied only to majority-

minority districts. Senator Roy Cooper, an attorney who chaired

the Senate Redistricting Committee, explained to his fellow

senators:

[When the Court struck down the 12" District it

was because the 12" District was majority

minority and it said that you cannot use race as

the predominate factor in drawing the districts.

In a leading case involving legislative districts, Chief Justice

Warren expressed for the Court this view of its responsibility: “We are

cautioned about the dangers of entering into political thickets and

mathematical quagmires. Our answer is this: a denial of constitutionally

protected rights demands judicial protection; our oath and our office require

no less of us.” Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 566 (1964).

ZSee Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50 (1986), which, under

certain conditions, requires majority-minority districts for geographically

compact groups of minority voters. In this instance, the legislature may be

“race-conscious” in order to avoid splitting such groups.

15

Well, guess what! The 12" District, under this

plan, 1s not majority minority. Therefore it is my

opinion and the opinion of many lawyers that the

test outlined in Shaw v. Hunt will not even be

triggered because it is not a majority minority

district and you won’t even look at the shape of

the district in considering whether it is

constitutional.

J.A. 132. Likewise, in proposing District 12 to his colleagues,

Representative W. Edwin McMahan, who chaired the House

Redistricting Committee, stated:

[It 1s] not a Majority/Minority District now so

shape does not create that — that was the basis the

Court used to say this was unconstitutional — not

an argument now.

J.A. 121.

This premise — presumably based on advice from the

State’s Attorney General — is in error.” In Miller, this Court

stated that the plaintiff bears the burden of showing “that race

was the predominant factor motivating the legislature’s decision

to place a significant number of voters within or without a

particular district.” 515 U.S. at 916. Although the Court was

discussing Georgia’s majority-black districts, the rationale of

Miller and Shaw is not limited to majority-black districts. In

Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 117 S. Ct. 2186, 2195 (1997),

the Court’s discussion of whether a Florida reapportionment

plan subordinated traditional redistricting principles to race does

not intimate that the legislative district under attack was immune

In his dissent in the court below, Judge Ervin made the same

error. See J.A. 30a.

16

from the application of Shaw principles simply because it was

“not a majority black district, the black voting-age population

being 36.2%.” As Miller points out, Shaw — like Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) and other leading

precedents — is based on the idea that “[a]t the heart of the

Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection lies the simple

command that the Government must treat citizens as individuals,

not as simply components of a racial, religious, sexual or

national class.” 515 U.S. at 911 (citations omitted). In creating

District 12, the General Assembly moved a “significant number”

of African-Americans into District 12 and as an inevitable

consequence moved a “significant number” of whites into

adjacent districts.”* These citizens, black and white, were not

treated as “individuals” but as components of a racial class — as

“mere racial statistics,” see Vera, 517 U.S. at 985. The very fact

that the legislators believed that Shaw I did not apply to

majority-white districts helps explain the State’s claim that the

legislators attempted to comply with Shaw even though they

created an obviously race-based district in violation of

traditional districting practices.”

**Two major concentrations of African-Americans in the northern

part of the state — 70,114 in Guilford County and 43,105 in Forsyth County

— were placed in the same district as Mecklenburg County, which is on the

South Carolina line. The obvious purpose was to link them with 113,442

African-Americans in Mecklenburg County. The district court’s

Memorandum Opinion spells out in some detail how this “significant

number” of African-Americans were placed — precinct by precinct — in

District 12. The maps lodged with the Court by appellees make quite

evident the racially motivated placement of “significant numbers” of voters

“within or without” District 12.

»This fundamental misunderstanding of Shaw by the General

Assembly contradicts the appellants’ assertion that “[t]hese legislators

[Representative McMahan and Senator Cooper] testified under oath that

they and their colleagues were well aware, when they designed and enacted

the 1997 plan, of the constitutional limitations imposed by this Court’s

decisions in Shaw and its progeny. . ..” See St. App. Br. 25.

17

C. The Continuing Evasion of the Principles of Shaw v.

Reno Should Not Be Tolerated.

Appellants and their allies have consistently derided

Shaw as being concerned only with “appearances.” However,

not only do appearances of a district have significance in

generating racial perceptions and polarization, see Shaw I, 509

U.S. at 647, but also “appearances” help establish the legislative

intent. Thus, in Miller the Court made clear that appearances

together with relevant demographics are an acceptable means of

proving a predominant racial motive. See 515 U.S. at 905; cf.

Shaw II. In urging that a direct admission by the legislature of

a predominant racial motive is necessary, appellants disregard

the Court’s own language in Miller, which clearly stated that

circumstantial evidence was a permissible alternative. Seeking

to achieve their objective indirectly, appellants insist that even

if a predominant racial motive is clearly revealed by a

redistricting plan’s shape, demographics, and violation of

traditional redistricting principles, summary judgment cannot be

entered if two legislators execute affidavits denying a racial

motive. Accepting this argument would facilitate the evasion of

Shaw principles, produce delay, and result in unnecessary trials.

Appellants’ argument is especially vulnerable when, as here, the

overwhelming evidence of racial motivation is not “directly

contradicted” by the legislators’ affidavits” and when these

affidavits not only lack specificity but also are inconsistent with

statements made by the same legislators on the floor of the

General Assembly, with the State’s own preclearance

submission, and with the demographics related to the plan.

Question 1 in State appellants’ brief assumes that plaintiffs’

evidence was “directly contradicted” by the affidavits of Senator Cooper

and Representative McMahan. As discussed later in detail, this assumption

is totally erroneous.

18

Another means for evading Shaw requirements and

masking a racial motive is use of the amorphous concept of

“functional compactness.” Because this concept — unlike

geographical compactness®’ — cannot be quantified, it can be

employed to conceal the use of racial stereotypes. As employed

by the State in the Shaw litigation to defend the 1992 plan and

now the 1997 plan — and as it has been used to defend other

racial gerrymanders — “functional compactness” assumes that

blacks who live in one city necessarily have more in common

with blacks in another city than they have in common with white

neighbors in their own city — even though their white neighbors

may work in the same offices and factories as these blacks, shop

in the same stores, have children in the same schools, read the

same newspapers, watch the same television stations, listen to

the same radio stations, have the same local government

officials, and serve on the same juries. Contrary to this

“The “perimeter measure” and “dispersion measure” of

geographical compactness are familiar to this Court and helped demonstrate

the lack of compactness of the districts involved in Shaw II and Bush v.

Vera. According to appellants’ expert, Dr. Gerald R. Webster, these

“[tJ]wo compactness measures . . . are now among the most commonly

recognized and applied by legal and academic scholars.” J.S. App. 120a.

In this case, they were used by plaintiffs’ experts — Dr. Ron Weber, Dr.

Timothy O'Rourke, Dr. Thomas Darling, and Dr. Carmen Circinione — in

reaching their unanimous opinion that the legislature designed District 12,

as well as District 1, with a predominant racial motive. Although

“compactness” and “contiguousness” of districts are not constitutional

requirements, their absence has equal protection implications, because it

contradicts the rationale for having geographically defined districts. Cf.

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. at 568, n.21 (Alabama apportionment plan

“presented little more than crazy quilts, completely lacking in rationality,

and could be found invalid on that basis alone”); Drum v. Seawell, 250 F.

Supp. 922, 925 (M.D.N.C. 1966) (setting aside North Carolina’s

redistricting plan because protection of incumbent congressmen

predominated “over the requirements of practicable equality, and we think

that compactness and contiguity are aspects of practicable equality”).

19

assumption, few residents of Charlotte — regardless of their race

and regardless of their “drive time”? to Greensboro and

Winston-Salem — would recognize their “functional” identity

with residents of Greensboro and Winston-Salem; and vice

versa. Moreover, when, as in North Carolina’s redistricting,

“functional compactness” has been used repeatedly to justify

congressional districts in which geographically separated

concentrations of blacks are linked together but has not been

used to explain how majority-white districts are linked together,

this circumstance is added proof of the legislature’s disguised

racial motive.

D. The Shaw v. Reno Requirement of a “Predominant”

Racial Motive Should Be Conformed to Other Equal

Protection Precedents.

In Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Dev.

Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 265-66 (1977), this Court ruled that in

reviewing legislative or administrative action to determine if it

violated equal protection the issue is whether “there is a proof

that a discriminating purpose has been a motivating factor in the

decision.” If so, “judicial deference” to the legislature or

administrative body “is no longer justified.” Id, cf. Mt. Healthy

City Sch. Dist. Bd. of Educ. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977).

“Once racial discrimination is shown to have been a ‘substantial’

or ‘motivating’ factor behind enactment of the law, the burden

shifts to the law’s defenders to demonstrate that the law would

have been enacted without this factor.” Hunter v. Underwood,

®Dr. Stuart's affidavit about “average driving times in an

automobile” — in which *“[n]o allowances were made for possible rush hour

traffic congestion” — not only ignores “rush hour congestion” in the cities

involved, but also makes no mention of the fact that Charlotte is in one

metropolitan area and one media market, while Greensboro and Winston-

Salem are in a different metropolitan area and media market. J.S. App.

101a.

20

471 U.S. 222, 228 (1985). The issue then is whether the same

action would have been taken in the absence of the racial motive

— whether that motive was a “but for” cause of the action. To

promote consistency with these other equal protection cases,

appellees submit that the Shaw requirement of discriminatory

intent should be phrased in terms other than a “predominant

racial motive” and that the inquiry should be whether the

legislature had a racial motive without which the redistricting

plan would not have been enacted. Although avoidance of

judicial interference with the authority of state legislatures 1s an

important goal, even more important in our democratic society

is preservation of the rights of the voters who elect the state

legislators and representatives to Congress. “The right to vote

freely for the candidate of one’s choice is of the essence of a

democratic society.” Shaw I, 509 U.S. at 639 (quoting Reynolds,

377 U.S. at 555). If the Arlington Heights test is used to prevent

other race-based violations of the right to equal protection,

consistency and the avoidance of confusion would dictate that it

be used to prevent unconstitutional racial gerrymanders.”

E. A Remedial Plan for Violations of Shaw v. Reno

Requires Especially Demanding Judicial Scrutiny.

After racial segregation in the schools was held by this

Court to violate equal protection guarantees, many federal

district courts were required to oversee the process of school

desegregation. For their guidance, the Court emphasized that

once an equal protection violation had been proven, local school

®Of course, in this case the district court expressly determined

from the uncontroverted material facts that the General Assembly’s racial

motive was predominant. Obviously the same evidence would establish

that, absent the legislature’s racial purpose, any redistricting plan enacted

would have been quite different.

Lo

re

oO

a

RR

E

R

es

ud

21

authorities must “eliminate from the public schools all vestiges

of state-imposed segregation.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 15 (1971). In another school

desegregation case, the Court made clear that the Dayton Board

of Education was “under a continuing duty to eradicate the

effects” of segregated schools. See Dayton Bd. of Educ. v.

Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526, 537 (1979). Various courts of appeal

have rendered decisions to the same effect.’’ Somewhat

analogous are cases which discuss the effects of the violation of

due process rights by government agents and which hold that

confessions are inadmissible if they result from an

unconstitutional search or arrest. See Wong Sun v. United States,

371 U.S. 471, 484 (1963); Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590

(1975); Dunaway v. New York, 442 U.S. 200, 216 (1979);

Taylor v. Alabama, 457 U.S. 687 (1982).

In line with these precedents, it deserves emphasis that

the 1997 redistricting plan reviewed by the district court was a

“remedial plan” adopted after North Carolina’s 1992 plan had

been held unconstitutional. Although alegislature must be given

*Such “vestiges” include faculty assignments, transportation,

student assignments, and “racially-identifiable” schools. See United States

v. Lawrence County Sch. Dist., 799 F.2d 1031, 1043 (5" Cir. 1986).

See, e.g., Brown v. Board of Education, 892 F.2d 851, 859 (10®

Cir. 1989) (defendant Board of Education must prove its efforts to comply

with desegregation orders had “eliminated all traces of past intentional

desegregation to the maximum feasible extent”); Taylor v. Ouachita Parish

Sch. Bd., 648 F.2d 959, 967-68 (5th Cir. 1981) (failure of school authorities

to eradicate the “vestiges” of de jure segregation is a constitutional

violation); Ross v. Houston Independent Sch. Dist., 699 F.2d 218, 225 (5*

Cir. 1983) (a school system must “eradicate, root and branch, the weeds of

discrimination”); School Bd. of the City of Richmond v. Baliles, 829 F.2d

1308, 1311 (4™ Cir. 1987) (once the equal protection violation has been

established, plaintiff is “entitled to the presumption that current disparities

are causally related to prior segregation, and the burden of proving

otherwise rests on the defendants”).

22

a reasonable opportunity to meet constitutional requirements by

adopting a substitute measure rather than for a federal court to

devise its own plan, see Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535, 540

(1978), this 1s consistent with requiring that district courts

examine the remedial plan with special care to assure that no

“vestiges” of the unconstitutional racial gerrymander remain and

that all “traces” of the earlier predominant racial motive have

been rooted out. Moreover, when — as with North Carolina’s

1992 and 1997 redistricting plans — a clear resemblance exists

between the earlier unconstitutional plan and the remedial plan,

see J.A 59a and 61a, a plaintiff is entitled to the presumption

that “current disparities are causally related” to the earlier

gerrymander and the “burden of proving otherwise rests on the

defendants.” Cf. School Bd. of the City of Richmond v. Baliles,

829 F.2d at 1311.

In defending the 1997 plan, appellants insist that their

goals were political — to protect incumbents, maintain a partisan

balance, and maintain the cores of earlier districts. See St. App.

Br. at 24-25. However, since all the incumbents were elected

pursuant to an unconstitutional plan, their “protection” — to

whatever extent it may be related to retaining the “cores” of the

districts that elected those incumbents — is the antithesis of

eliminating all “vestiges” and “traces” of the 1992 racial

gerrymander. The same holds true for “maintaining partisan

balance” which was achieved under an unconstitutional plan.

The goal of retaining the cores of districts in the 1992 plan is

reminiscent of the unsuccessful reliance by the appellants in

Abrams v. Johnson, 117 S. Ct. 1925 (1997), upon an

unconstitutional plan that had been drawn in 1991 to satisfy the

Civil Rights Division’s unlawful “maximization” policy. As this

Court made clear, the baseline for the remedial plan should

instead have been the 1982 redistricting plan, which had not

been tainted by a predominant racial motive. See id. at 1939.

Likewise, if the North Carolina General Assembly wished to use

23

an earlier plan as a baseline, that baseline should have been the

plan used for congressional elections in the 1980s — a plan that

was not race-driven.

Furthermore, in dealing with a remedial plan, a special

danger exists that — as 1n this case — the legislature will make

misleading use of labels and will claim spuriously that a racial

gerrymander 1s a “political” gerrymander. Indeed, if such a

defense were accepted uncritically, the corollary would be that

in 1997 the General Assembly could have reenacted the original

1992 redistricting plan and then defended it because now its

predominant motive was “political” — protecting incumbents and

maintaining the existing partisan balance. The “political”

defense should be summarily rejected in this case where the

“fruit” of an unconstitutional racial gerrymander are used to

justify perpetuating that same constitutional violation.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY GRANTED

SUMMARY JUDGMENT THAT NORTH

CAROLINA’S TWELFTH CONGRESSIONAL

DISTRICT IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL.

Summary judgment is appropriate when no genuine issue

exists as to any material fact and on the uncontroverted material

facts the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.

See Fed. R. Civ. Proc. 56(c). The moving party is entitled to

summary judgment when a rational trier of fact, after

considering the record as a whole, could not find for the non-

moving party. See Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Radio

**The logic of the “fruit of the poisonous tree” doctrine — which

this Court has applied to protect due process rights, cf. Wong Sun v. U.S. -

seems equally applicable in preventing violations of equal protection rights.

24

Corp., 475 U.S. 574, 587 (1986). The moving party must

demonstrate the lack of a genuine issue of fact for trial, and if

that burden is met, the party opposing the motion must show

evidence of a genuine factual dispute. The “quality and quantity

of evidence required by the governing law” is to be reviewed on

motion for summary judgment. See Anderson v. Liberty Lobby,

Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 254 (1986). The “mere existence of a

scintilla of evidence” for the non-moving party’s position is

insufficient to defeat a properly supported motion; there must be

enough evidence for a reasonable jury to find for the non-

moving party. Id. at 252; see also Aleyska Pipeline Serv. Co. v.

U.S. E.P.A., 856 F.2d 309, 314 (D.C. Cir. 1988) (“a motion for

summary judgment adequately underpinned is not defeated

simply by a bare opinion or an unaided claim that a factual

controversy persists”); Ross v. Communications Satellite Corp.,

759 F.2d. 355, 365 (4™ Cir. 1985) (“[u]lnsupported allegations as

to motive do not confer talismanic immunity from Rule 56").

Appellants cannot justly contend that Rule 56(c) was

improperly applied against them. The district court specifically

placed on the plaintiffs “the burden of proving the race-based

motive” and stated that “[i]n the final analysis, the plaintiff must

show ‘that race was the predominant factor motivating the

legislature’s decision to place a significant number of voters

within or without a particular district.”” See J.S. App. 15a

(quoting Shaw II, 517 U.S. at 905, and Miller, 515 U.S. at 916).

The district court concluded that, “based on the uncontroverted

material facts before it,” the General Assembly “utilized race as

a predominant factor in drawing” District 12. J.A.21a-22a. That

If, instead of granting summary judgment, the district court had

ruled only on the plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injunction pending a

trial, the court would have weighed the probability of plaintiffs’ success on

the merits, irreparable harm to plaintiffs’ rights, injury to defendants, and

public interest. See 11A Charles A. Wright, et al., Federal Practice and

Procedure, Sec. 2948.

25

conclusion was compelled by all the evidence before the court.

A. The Shape and Demographics of North Carolina’s

Twelfth Congressional District Show Unmistakably

That Race Was the Predominant Motive for Its

Design.

The district court, viewing the uncontroverted material

facts presented by the appellees and recognizing the dangers

articulated in Shaw I, properly found that “the General Assembly

utilized race as the predominant factor in drawing the District,

thus violating the rights to equal protection guaranteed in the

Constitution to the citizens of District 12.” J.S. App. 22a

(footnote omitted). In determining that race was “the

‘predominant’ consideration in drawing the district lines such

that ‘the legislature subordinate[s] race-neutral districting

principles . . . to racial considerations’ J.S. App. 16a (quoting

Miller, 515 U.S. at 916), the district court observed that “the

legislature disregarded traditional districting criteria such as

contiguity, geographical integrity, community of interest, and

compactness in drawing District 12 in North Carolina’s 1997

plan.” J.S. App. 22a.

1. Race Dictated the Twelfth District’s Bizarre

Shape and Lack of Compactness.

A quick glance at the map of District 12 (see J.S. App.

15a) reveals that it fails the “eyeball test” and other well-

recognized objective tests of compactness.* As the district court

**The dispersion measure and perimeter measure of compactness

developed by Richard Pildes and Richard Niemi in their 1993 Michigan

Law Review article, Expressive Harms, “Bizarre Districts,” and Voting

Rights: Evaluating Election-District Appearances After Shaw v. Reno, 92

Mich. L. Rev. 483, have been much used in Shaw litigation and in striking

down three racially-gerrymandered Texas districts, this Court noted that

26

pointed out,

“[w]hen compared to other previously challenged

and reconstituted congressional districts in North

Carolina, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, and Texas,

District 12 does not fare well. The District’s

dispersion and perimeter compactness indicators

(0.109 and 0.041, respectively) are lower than

those values for North Carolina’s District 1

(0.317 and 0.107 under the 1997 plan).

Similarly, the District suffers in comparison to

Florida’s District 3 (0.136 and 0.05), Georgia’s

District 2 (0.541 and 0.411) and District 11

(0.444 and 0.259), Illinois’ District 4 (0.193 and

0.026), and Texas District 18 (0.335 and 0.151),

District 29 (0.384 and 0.178), and District 30

(0.383 and 0.180).”

J.S. App. 20a-21a. According to Professor Timothy G.

O’Rourke, “[1]f the 1992 rankings had remained unchanged, the

new version of the 12th would still stand as the 430th least

compact district on the dispersion measure and it would rank

423 on the perimeter measure.” J.A. 249.” Professor Weber,

who has provided current rankings based on changes made to

other districts, states that “North Carolina 12 ranks either 430 or

431 out of 435 in compactness using the dispersion measure”

and “either 432 or 433 of 435 in compactness using the

perimeter measure.” J.A. 213. As these numbers make clear,

“customary and traditional districting practices” have been

they were among the twenty-eight least compact in the nation when these

measures were applied. See Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996).

350f course, since several districts have changed since 1992 as a

result of post Shaw I litigation, the actual compactness rankings of District

12 would now rank even lower in any comparison of compactness.

27

utterly disregarded and District 12 constitutes an “extreme

instance of gerrymandering.” See Miller, 515 U.S. at 928-29

(O'Connor, J., concurring).

The State’s Section 5 submission recites that “geographic

compactness” was one of five factors emphasized “in locating

and shaping the new districts.” J.S. at 63a. This assertion is

misleading and inconsistent with the facts regarding District 12.

This inconsistency suggests that in the preclearance submission

State officials sought to conceal the General Assembly’s race-

based purpose — a concealment which itself provides evidence

of that purpose. Likewise, making other districts

“geographically compact” but not doing so for District 12 helps

prove that this district was different from others — namely, that

District 12 was the product of a race-based intent.

In Lawyer, the Court pointed out that the senatorial

district under attack “is located entirely in the Tampa Bay area,

has an end-to-end distance no greater than that of most Florida

Senate districts, and in shape does not stand out as different from

numerous other Florida House and Senate districts.” 117 S. Ct.

at 2194-95. Moreover, while that district “crosses a body of

water and encompasses portions of three counties, evidence

submitted showed that both features are common characteristics

of Florida legislative districts, being products of the State’s

geography and the fact that 40 Senate districts are superimposed

on 67 counties.” Id. On the other hand, North Carolina’s

District 12 is not “located entirely” in a single metropolitan area,

and its shape surely does “stand out as different from” all other

North Carolina congressional districts. In fact, the only other

North Carolina districts with irregular boundaries are District 1,

which is race-based, and those districts which have boundaries

coinciding with District 12 or District 1. Unlike Lawyer, where

the senatorial district under attack was on both sides of Tampa

Bay, the bizarreness of District 12 is not a “product” of North

28

Carolina’s geography; nor does it result from the fact that twelve

congressional districts are “superimposed” on one hundred

counties.

As this Court explained in Miller, “[s]hape 1s relevant

not because bizarreness is a necessary element of the

constitutional wrong or a threshold requirement of proof, but

because it may be persuasive circumstantial evidence that race

for its own sake, and not other districting principles, was the

legislature’s dominant and controlling rationale in drawing its

district lines.” 515 U.S. at 913; see also Karcher v. Daggett,

462 U.S. 725, 755 (1983) (“dramatically irregular shapes may

have sufficient probative force to call for an explanation”). In

this case, the only “explanation” for the shape and demographics

of District 12 is that race was used for its own sake.

The maps and data presented to the district court showed

that District 12 meanders though six counties, splitting each

along racial lines to pick up virtually every precinct in those

counties with a black population over forty percent. See J.A.

183. Seventy-five percent of the total population of District 12

comes from parts of Mecklenburg, Forsyth and Guilford

Counties which are majority black. See J.A. 176. These three

population centers are also at the extremes of the District —

Mecklenburg at the southern and Forsyth and Guilford at the

northern. Forsyth County is divided so that 72.9 percent of the

total population allocated to District 12 is African-American,

while only 11.1 percent of the total population assigned to

District 5 is African-American. See id. In Mecklenburg county,

51.9 percent of the total population allocated to District 12 is

African-American, while only 7.2 percent of the total population

assigned to District 9 is African-American. See id. Finally, in

Guilford County, 51.5 percent of the total population allocated

to District 12 is African-American, while only 10.2 percent of

the total population assigned to adjacent District 9 is African-

29

American. See J.A. 183. For any resident of those three

counties, the inevitable perception would be that District 12 is

race-based.

In Vera, when describing the shape of a section of a

district held to be unconstitutional, this Court stated that, “the

northernmost hook of the district, where it ventures into Collin

County, is tailored perfectly to maximize minority population.”

517 U.S. at 971. This description aptly describes how District

12 slithers into Forsyth County to extract all precincts but one

with an African-American population in excess of forty percent.

See map, Exhibit O. From Forsyth County, only two precincts

with an African-American population of less than forty percent

were included in District 12; and those two precincts were at the

gateway for District 12’s entry into Forsyth from the south. See

map, Exhibit O.

According to the State’s preclearance submission,

“functional compactness (grouping together citizens of like

interest and needs)” was another of five factors employed in

shaping the districts. In this context, “functional compactness”

1s apparently another name for “community of interest.” It calls

to mind this Court’s observation in Miller: “Nor can the State’s

districting legislation be rescued by mere recitation of purported

communities of interest.” 515 U.S. at 919. The legislative

history of the 1997 plan gives no specifics as to any real

communities of interest present in District 12. The fact that

many residents of District 12 live in cities in the northemn part of

the state and many others live in a city in the southern part of the

State does not give rise to any “community of interest” —

especially since the first group is in the Piedmont Triad

metropolitan area and the second is in the Charlotte metropolitan

area. Once again the State’s concealment of motive by citing a

non-existent “factor” is an admission by conduct that helps

prove the plaintiffs’ case.

30

2 Contiguity Was Subordinated to Racial

Considerations.

A narrow land bridge, located in the south-central

portion of Mecklenburg County, prevents District 12 from

completely dividing both Mecklenburg County and adjacent

District 9. This bridge was created by splitting Precinct 77 in

such a way that a section less than two miles wide and

containing only one of the precinct’s 3,462 residents was placed

outside District 12. Thus, a single person provides a “human

link” so that District 12 does not sever adjacent District 9 and

Mecklenburg County into two non-contiguous parts.*® See J.A.

250.” Moreover, in several areas District 12 narrows to one

precinct wide as it winds through counties, cities and towns to

achieve its race-based goal. See map, Exhibit M. These narrow

corridors enable the district to stretch from Charlotte to

Greensboro but minimize the number of “filler” people in

between.

3. Political Subdivisions and Actual

Communities of Interest Were Subordinated

to Racial Considerations.

Despite their claimed goal of “avoidance of the division

of counties and precincts,” J.S. App. 63a, the General Assembly

demonstrated little respect for political subdivisions in creating

District 12 and often divided them on the basis of race. The

district court described how counties were split in the design of

District 12:

Since Precinct 77 contains a substantial percentage of African-

Americans, the legislature obviously did not want to put the whole precinct

into District 9.

"The one person in Precinct 77 who was placed in District 9

cannot cast a secret ballot in a congressional election.

31

District 12 is composed of six counties, all of

them split in the 1997 plan. The racial

composition of the parts of the six sub-divided

counties assigned to District 12 include three

with parts over 50 percent African-American,

and three in which the African-American

percentage 1s under 50 percent. However, almost

75 percent of the total population in District 12

comes from the three county parts which are

majority African-American in population:

Mecklenburg, Forsyth, and Guilford counties.

The other three county parts (Davidson, Iredell,

and Rowan) have narrow corridors which pick

up as many African-Americans as are needed for

the district to reach its ideal size.

Where Forsyth County was split, 72.9

percent of the total population of Forsyth County

allocated to District 12 is African-American,

while only 11.1 percent of its total population

assigned to neighboring District 5 is African-

American. Similarly, Mecklenburg County is

split so 51.9 percent of its total population

allocated to District 12 is African-American,

while only 7.2 percent of the total population

assigned to adjoining District 9 is African-

American.

J.S. App. 6a-7a. District 12 is the only district in North Carolina

with no intact counties. As Professor Weber stated in his

affidavit, “[nJo single district in the country is like North

Carolina 12 in splitting as many as six counties and subdividing

100 percent of them.” J.A. 209. As the district court noted,

cities, like counties, were split along racial lines in creating

32

District 12. See J.S.App. at 7a. According to Professor Weber,

9 of 13 cities or towns — including the four largest cities — were

split along racial lines to create District 12. See J.A. 184.

B. District 12 Cannot Be Justified By Means of a

Spurious Claim that It Was Created with a Political,

Rather than Racial, Motive.

Question 2 in State appellants’ brief implies that the

district court improperly relied on “isolated and sporadic party

registration data” when it should have focused on “actual voting

results.” However, the district court can not be criticized for

closely scrutinizing voter registration data because, prior to the

March 31 hearing, the defendants had represented to the court

that “[t]he leaders of the House and Senate Committee also had

available, and used, voting behavior information consisting of

precinct level voter registration data and the results of the 1990

U.S. Senate election and the 1988 Lt. Governor and Court of

Appeals elections.” Defendants’ Brief in Opposition to

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment and in Support of

Their Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment 7 (emphasis added).

This voter registration data was readily available to any member

of the General Assembly through its public access computer;

moreover, “redistricting legislatures will . . . almost always be

aware of racial demographics.” See Miller, 515 U.S. at 916.

Instead of being “sporadic and isolated,” the registration

data was quite comprehensive and demonstrated conclusively

that in Guilford, Forsyth, and Mecklenburg counties many

precincts adjacent to District 12 had high Democratic

registration but low percentages of African-Americans and that

the exclusion of these precincts from District 12 was clearly

attributable to race — not party. As the district court explained:

the legislature did not simply create a majority-

33

Democratic district amidst surrounding

Republican precincts. For example, around the

Southwest edge of District 12 (in Mecklenburg

County), the legislature included within the

district’s borders several precincts with racial

compositions of 40 to 100 percent African-

American; while excluding from the district

voting precincts with less than 35 percent

African-American population, but heavily

Democratic voting registrations.

J.S.App. at 8a. This pattern was repeated in Forsyth and

Guilford Counties. Id. These and other undisputed facts

convinced the district court that “District 12 was drawn to

collect precincts with high racial identification rather than

political identification.” Id. at 21a.

In Vera, when reviewing Houston districts held

unconstitutional, this Court stated that the “district lines

correlate almost perfectly with race, while both districts are

similarly solidly Democratic.” 517 U.S. at 975. North

Carolina’s registration data shows that the lines dividing

precincts of District 12 from the previously mentioned precincts

of other districts “correlate almost perfectly with race;” however,

both the black precincts within District 12 and the white

precincts adjacent to District 12 are “solidly Democratic.” Asin

Texas, this correlation suggests that race was the predominant

motive for the district boundaries, but that appellants attempted

to conceal this motive by referring to party data.

No one questions that for several decades a very high

percentage of African-Americans in North Carolina have

registered as Democrats. In the trial of Shaw v. Hunt, Melvin

Watt, an African-American who has represented District 12 in

Congress since 1992, testified that “95% or higher of the

34

African-Americans registered to vote in North Carolina are

registered as Democrats.” J.A. 158. Likewise, Gerry Cohen, the

staff member of the General Assembly who played the greatest

role in redistricting for the General Assembly, testified that in

“urban areas” the percentage was 95 percent, but in “rural areas”

the percentage was 97 to 98 percent. Id. Under these

circumstances, legislators can easily claim that any district with

a high percentage of blacks was drawn for “political” purposes

to obtain Democratic votes. In his affidavit, Dr. Peterson —

although admitting the high correlation of District 12’s

boundaries with race — emphasizes instead the correlation of its

boundaries with Democratic party registration and Democratic

performance. Because typically the number of black registered

voters is exceeded by the number of voters registered as

Democrats, he reasons that District 12 was designed with a

political, rather than a racial, motive. If, however, more than

95% of the black voters have registered as Democrats, the

number of registered Democrats in a precinct will exceed the

number of registered blacks — unless white registered voters

have registered almost exclusively as Republicans or

independents. Thus, the party correlation discussed by Dr.

Peterson is misleading and has no significance.

In light of the district’s history, it seems obvious that the

legislators were assuming that to concentrate large numbers of

blacks in the “new” District 12 would guarantee that a black

candidate who ran for office would receive a majority in the

Democratic primary because of the large number of black voters

registered as Democrats. Their second assumption was that the

black Democratic nominee then would be elected because he or

she had a solid core of support based on the racial loyalty of

fellow African-Americans and the party loyalty of some white

Democrats. In making these two assumptions the General

Assembly relied on “racial stereotypes” and treated a

“significant number” of black voters as “mere racial statistics.”

35

Thereby they violated the precepts of Shaw I.

Appellants complain that the district court should have

used “actual election results” instead of “party registration

data.’®® The General Assembly had available the “actual

election results” of three statewide elections; and even though

State appellants intimate that additional “results” should have