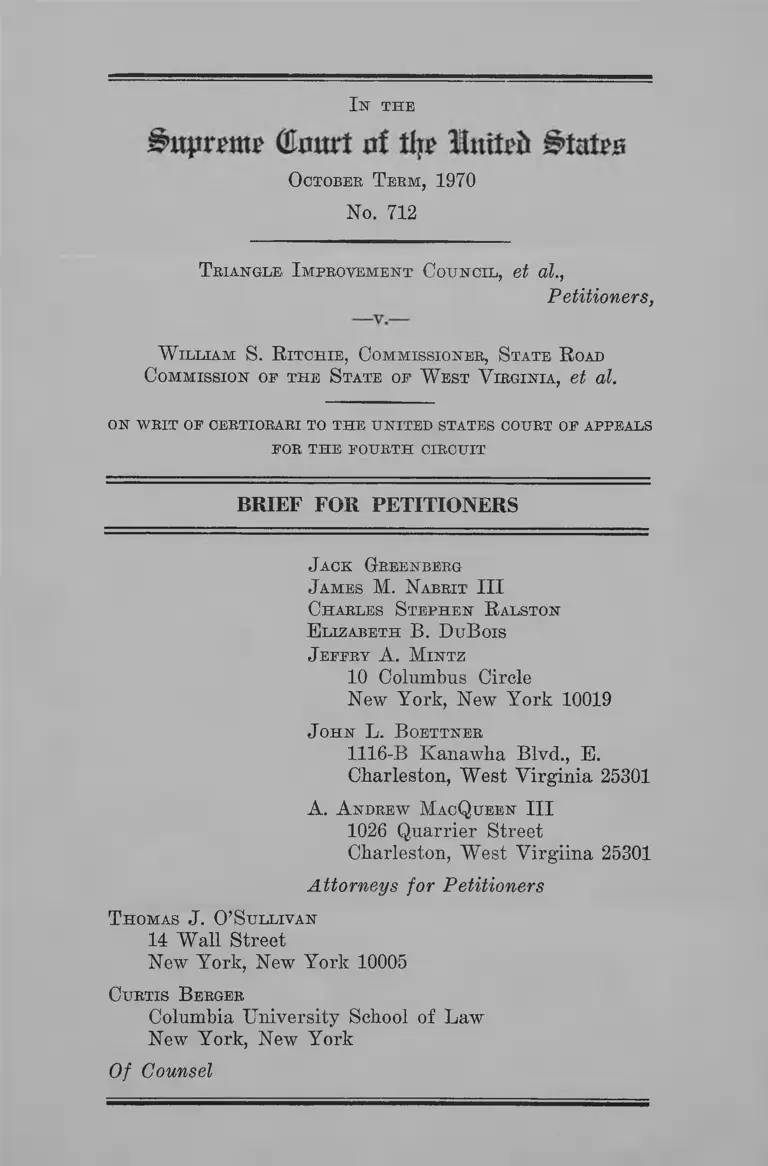

Triangle Improvement Council v. Ritchie Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Triangle Improvement Council v. Ritchie Brief for Petitioners, 1970. 45ade4f0-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a9bf04dd-d0e5-4f08-92c6-2ce1092eb0a8/triangle-improvement-council-v-ritchie-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

October Teem, 1970

No. 712

Triangle I mprovement Council, et al.,

Petitioners,

W illiam S. R itchie, Commissioner, S tate R oad

Commission op the S tate op W est V irginia, et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit III

Charles S tephen R alston

E lizabeth B . D u B ois

J effry A . Mintz

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J ohn L. B obttnee

1116-B Kanawha Blvd., E.

Charleston, West Virginia 25301

A. A ndrew MaoQueen III

1026 Quarrier Street

Charleston, West Virgiina 25301

Attorneys for Petitioners

T homas J . O’S ullivan

14 Wall Street

New York, New York 10005

Curtis B erger

Columbia University School of Law

New York, New York

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below.............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................... 2

Question Presented..................................—................. 2

Constitutional, Statutory, and Regulatory Provisions

Involved - ....... 3

Statement ....................................................................... 4

Introduction ............................................................ 4

A. Summary of Pacts ............ 6

1. Charleston, West Virginia, and the Triangle 6

2. 1-77 and the Highway Approval Process 9

3. The 1968 Relocation Amendments to the

Federal-Aid Highway Act and the Admin

istrative Regulations to Implement Them .. 11

4. The Relocation “Program” in the Triangle 14

B. Summary of Proceedings in the Courts Below 17

S ummary op A r g u m e n t ............................................................... 20

A rgument

I. The Displacement of the Black Petitioners Into

a Racially Discriminatory Housing Market

Without Adequate Governmental Measures to

Assure Non-Discriminatory Relocation Housing

Deprives Them of the Equal Protection of the

Laws Guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment ........ ................. ................. —...................... 24

11

PAGE

II. The 1968 Relocation Amendments to the Fed

eral-Aid Highway Act and Regulations There

under Grant Relocation Benefits to the Triangle

Residents Which Have Not Yet Been Admin

istratively or Judicially Accorded Them .......... 27

A. The 1968 Relocation Amendments Assure

Persons Not Yet Displaced as of the Date

of Enactment the Right to Adequate Re

placement Housing, and Pursuant Thereto

Mandate Detailed Relocation Plans ............ 27

B. In the Absence of Compliance with the Re

quirements of the 1968 Relocation Amend

ments, Administrative Action by State and

Federal Officials Cannot Be Upheld on the

Basis of General Assurances That Efforts

Are Being and WiU Be Made to Relocate

Persons Displaced, and That Adequate Re

location Housing Exists ............................... 38

1. Reversal Is Required Because the Pro

cedures Mandated by Law with Respect

to the Submission for Review and Ap

proval of a Comprehensive Relocation

Plan Were Not Followed........................ 39

2. The District Court’s Purported Finding

That Relocation Housing Was Adequate

Was Clearly Erroneous ....................... 46

III. The Questions of Retroactive Application and

Appropriate Remedy.......................................... 50

Conclusion ........................... 53

lU

PAGE

Appendix A—Statutes ......................................Br. App. 1

Appendix B—Regulations and Policy

Directives ...................................................... Br. App. 17

Appendix C—Legislative History of 1968

Relocation Amendments to Federal-Aid

Highway A ct..................................................Br. App. 47

T able op A uthorities

Cases

Arrington v. City of Fairfield, 414 F.2d 687 (5th Cir.

1969) .......................................................................... 25

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S.

288 (1936) .............. ............................................... ..... 27

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 IJ.S. 715

(1961)............................................................-............. 25

Charlton v. United States, 412 F.2d 390 (3rd Cir. 1969) 42

'V/̂ Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 432 F.2d

1307 (6th Cir. 1970), cert, granted December 7, 1970,

O.T. 1970, No. 1066 .............................. 37,47

City of Chicago v. F.P.C., 385 F.2d 629 (D.C. Cir. 1967) 26

Crowell V. Benson, 285 U.S. 22 (1932) ........................ 27

Cy Ellis Raw Bar v. District of Columbia Redevelop

ment Land Agency, 433 F.2d 543 (D.C. Cir. 1970) .... 35

D.C. Federation of Civic Associations v. Airis, 391

F.2d 478 (D.C. Cir. 1968) .......................................... 43

DeLong v. Hampton, 422 F.2d 21 (3rd Cir. 1970) ...... 42

Environmental Defense Fund v. Hardin, 428 F.2d

1093 (D.C. Cir. 1970) ............................................... 45

IV

PAGE

Environmental Defense Fund v. Euckelshans,----F.2d

—- (D.C. Cir., January 7, 1971, No. 23813) .......... 45

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961) ..................... 26

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970) ........................ 44

Jones V. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) ...... 24

Kent V. Dulles, 357 U.S. 116 (1958) ............. 39

Medical Committee for Human Rights v. Securities and

Exchange Commission, 432 F.2d 659 (D.C. Cir.

1970) .................. ...................................................... . 45

Michigan Consolidated Gas Co. v. Federal Power

Comm., 283 F.2d 204 (D.C. Cir. 1960) cert, denied,

364 U.S. 913 (1960) ........ ......................................... . 44

Moss V. C.A.B., 430 F.2d 891 (D.C. Cir. 1970) .............. 43

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency,

395 F.2d 920 (2nd Cir. 1968) ....... ............................. 25

Office of Communications of United Church of Christ

V. FCC, 359 F.2d 994 (D.C. Cir. 1966) ....................... 44

Office of Communications of United Church of Christ

V. FCC, 425 F.2d 543 (D.C. Cir. 1969) ..........41, 44, 45, 47

Pauley v. United States, 419 F.2d 1061 (7th Cir. 1969) 42

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963) .... 26

/Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) ..................... 26

̂ Koad Review Leag-ue v. Boyd, 270 F. Supp. 650

(S.D.N.Y. 1967) ............................ ............. .............. 42

•^Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v. Federal

Power Comm., 354 F.2d 608 (2nd Cir. 1965), cert,

denied, 384 U.S. 941 (1966) ....... .............................44, 45

V

PAGE

Service v. Dulles, 354 U.8. 363 (1957) ....................... 32,43

SEC V. Chenery Corp., 318 IJ.8. 80 (1943)...... ........... . 44

^ h annon v. Dept, of Housing and Urban Development,

----- F.2d ----- , (3rd Cir. December 30, 1970, No.

18,397) ............................................... .......17, 26, 44,45, 52

Shelley V. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) .............. ............ 26

Small V. Ives, 296 F. Supp. 448 (D. Conn. 1968) ..Br. App. 48

Thorpe V. Housing Authority, 393 U.S. 268 (1969) ....20, 22,

35,44

Triangle Improvement Council v. Ritchie, 314 F. Supp.

20 (S.D.W.Va. 1969)........... ............ .................... passim

^Triangle Improvement Council v. Ritchie, 429 F.2d

423 (3rd Cir. 1970) .............. ................................... passim

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U.S. 350 (1962) ........ 25

Udall V. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1 (1965) ........ .......... .......19, 34

\yWestern Addition Community Organization v. Weaver,

294 F. Supp. 433 (N.D. Cal. 1968) ........ ......... ........30, 42

Williams v. Robinson, 432 F.2d 637 (D.C. Cir. 1970) 45

Zuber v. Allen, 396 U.S. 168 (1969) ...................... ........ 35

Statutes and Regulations

1. Statutes

Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. §701

et seq........... ............................ ..18,42

Fair Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. et seq............ 26

Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1968, 23 U.S.C. §501

et seq........................... passim

Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1970, Pub. L. 91-605,

§117 .....................................................................30,51

VI

PAGE

Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965,

Pub. L. 89-117, 79 Stat. 475, 42 U.S.C.

1455(c)(2).............................................................. 30

Pub. L. 90-495, §37, 82 Stat. 831............................12, 28

23 U.S.C. §106 ..................................................... 10

23 U.S.C. §128 ..................................................... 18

23 U.S.C. §133 ..................................................... 28

West Virginia Code Cb. 17, Art. 2A, Sec. 20 .......... 12

2. Regulations, Directives, and Memoranda of Depart

ment of Transportation

Circular Memorandum, January 23, 1968 ............14, 23

Circular Memorandum, December 26, 1968 ..........28, 34

Circular Memorandum, February 12, 1969 ...... 13, 31, 34

Circular Memorandum, March 27, 1970, as amended

April 10, 1970 .................................................... 14, 35

DOT Policy and Procedure Memoranda (PPM) 10,12, 52

Instructional Memorandum 80-1-68, September 5,

1968, as amended ............................................. passim

Memorandum of Under Secretary of Transportation

James M. Beggs, November 6,1970.....................10, 37

Memorandum on Implementation of Replacement

Housing Policy by Secretary of Transportation

John A. Volpe, January 15, 1970 ...................... 13,35

35 Fed. Reg. 6322 (1970) ...................... ................... 37

Vll

PAGE

Other Authorities

Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Rela

tions, Relocation: Unequal Treatment of People and

Businesses Displaced hy Government (1965) ,.Br. App. 49

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Intergovern

mental Relations of the Senate Committee on

Government Operations, 90th Cong., 2nd Sess......... 50

Highway Relocation Assistance Study, 90th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1967) ...................... ................. 32, Br. App. 50

Charleston (W. Va.) Gazette, November 13, 1970, p. 1 10

New York Times, July 13, 1970, p. 62, col. 1 ............... 10

Note, The Federal Courts and Urban Renewal, 69

CoLUM. L. R ev. 472 (1969).......................................... 42

Reich, Individual Rights and Social Welfare: The

Emerging Legal Issues, 74 Y ale L. J. 1245 (1965) .... 41

Select Committee on Real Property Acquisition, Study

of Compensation and Assistance for Persons Affected

by Real Property Acquisition in Federal and Fed

erally Assisted Programs, 88th Cong., 2nd Sess.

(1964) ............................................................. Br. App. 48

1965 U.S. Code Cong. & Adm. News............................... 30

1966 H.S. Code Cong. & Adm. News...................Br. App. 50

1968 H.S. Code Cong. & Adm. News............29, Br. App. 47,

Br. App. 50, Br. App. 52

I n ' t h e

^m xt of #tat^0

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1970

No. 712

T r ia n g l e I m p r o v e m e n t C o u n c i l , et al.,

Petitioners,

-V .-

WlLLIAM S. E iTCHIE, COMMISSIONER, S tATB E oAD

Commission op the S tate, op W est V irginia, et al.

ON 'WRIT OP CEBTIOBARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

POB THE T’OURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of West Virginia (App. 35a-59a), ̂ is

reported at 314 P. Supp. 20 (1969). The opinions of the

United States Court of Appeals with the dissent of Judges

Soheloff and Winter from the denial of rehearing en ham

(App. 65a-66a, 69a-78a) are reported at 429 F.2d 423

(1970).

̂The Single Appendix separately filed in this case is designated

herein “App.” The Appendix of statutes and regulations attached

to this brief is designated “Br. App.” Portions of the record not

printed in the Appendix are referred to by their original exhibit

number.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit was entered May 14, 1970 and the

petition for rehearing denied July 14, 1970. The petition

for a writ of certiorari was filed in this Court on September

17, 1970, and granted on December 21, 1970. This Court’s

jurisdiction derives from 28 U.S.C. §1254(1) .

Question Presented

Petitioners, residents of the black ghetto of Charleston,

West Virginia, have been or will be displaced from their

homes by the construction of a federally aided interstate

highway. They are required to obtain new housing in a

market from which they are excluded because of racial

discrimination and a shortage of low cost housing. This

case presents the fundamental constitutional question of

whether the Fourteenth Amendment requires that when

persons are removed from housing by state and federal

action and thereby subjected to private housing discrimina

tion, government officials must first make relocation hous

ing available to them without regard to race or economic

status.

Additionally, petitioners are among the class of persons

protected by the amendments to the Federal-Aid Highway

Act of 1968, 23 U.S.C. §501 et seq., which requires adequate

assurances of relocation housing prior to their displace

ment by highway construction. Relying on a subsequently

amended regulation, the United States Department of

Transportation and the State Road Commission refused

to provide such assurances, and the district court denied

relief. The Court of Appeals affirmed, notwithstanding an

intervening change in the regulations sustaining petition

ers’ position.

Under these circumstances, and especially where a pre

cise statutory remedy is available to cure a constitutional

wrong, are petitioners entitled to the relief the Constitu

tion requires and Congress has provided, but which

neither the administrative agencies nor the lower courts

have alforded to them!

Constitutional, Statutory,

and Regulatory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Fifth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves various provisions of Title 23

of the United States Code (Highways), in particular, former

§133 (repealed effective July 1, 1970, Pub. L. 90-495, §37,

Aug. 23, 1968, 82 Stat. 836) (Br. App. 1-2); Pub. L. 89-574,

§12, Sept. 13,1966, 80 Stat. 770 (Br. App. 2-3); the Federal-

Aid Highway Act of 1968, 23 U.S.C. §501, et seq. (Br. App.

4-13); the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1970, Pub. L. 91-605,

§117 (Br. App. 13-15); and the Pair Housing Act of 1968,

42 U.S.C. §3601 et seq., particularly §3608 (Br. App. 16).

This case also involves the following regulations and

policy directives issued by the Department of Transporta

tion:

(1) Circular Memorandum, January 23, 1968 (PI. Ex.

No. 9, App. 79a-81a).

(2) Instructional Memorandum, 80-1-68, IfTfl; 2; 3; 4;

5; 6; 7; 9a, c, and g ; 11; 12; 13; and 17c, f, g, and h ; Sep

tember 5, 1968, as amended (Br. App. 17-36).

(3) Circular Memorandum, December 26,1968 (Br. App.

37-38).

(4) Circular Memorandum, February 12, 1969 (Br. App.

39-40).

(5) Memorandum on Implementation of Replacement

Housing Policy issued by Secretary of Transportation John

A. Volpe, January 15, 1970 (Br. App. 41-42).

(6) Circular Memorandum, March 27, 1970, as amended,

April 10, 1970 (Br. App. 43-44).

(7) Memorandum of Under Secretary of Transporta

tion James M. Beggs, issued November 6, 1970 (Br. App.

45-46).

Statement

Introduction.

This action involves the right, under the Constitution

and federal statutes and regulations, of persons who are

displaced by the construction of a federal highway to be

relocated by the responsible state and federal agencies into

decent, safe, and sanitary housing. The case arises in the

context of a highway, to be built through the Triangle

section of Charleston, West Virginia. In the Federal-Aid

Highway Act of 1968, Congress addressed itself to the

serious problems of persons whose homes were destroyed

by highways in finding new housing. Sections 502 and 508

require the Secretary of Transportation and the states to

develop, enforce and implement relocation plans which

would in fact result in the availability of adequate housing

for displacees. 23 U.S.C. §502, 508.

Thus, the central statutory issue in this case is whether

the 1968 Act and regulations promulgated under it by the

Department of Transportation impose obligations towards

persons faced with displacement after its enactment by

a highway project commenced before its enactment. In

addition, this case raises a broader constitutional issue:

the right under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of

black and poor white persons to assured relocation housing

when forced by highway construction to seek new homes

in a housing market restricted because of racial discrimina

tion and high prices.

The following statement will be divided into two main

parts. The first will describe the factual setting of the case,

i.e. the history of the 1-77 highway project, its relationship

to the statutes and administrative regulations, and the

problem of finding adequate relocation housing in Charles

ton, West Virginia, as it relates particularly to the situa

tion of people who are poor and black. The second will

detail the proceedings in the courts below. As this case

requires a somewhat detailed description of the history of

Interstate Highway 77 and its relationship to the events

in this lawsuit and relevant statutes and regulations, we

have set out in the margin a table outlining the sequence

of events with which we are concerned.**

̂The following are the dates of the pertinent events involved in

this case;

1. August 31, 1964: Present route of 1-77 approved by

Federal Bureau of Public Eoads.

2. April, 1966-May, 1967; Federal authorization to acquire

land on highway right-of-way given.

3. August 23, 1968: Enactment and effective date of 1968

Federal-Aid Highway Act.

4. September 5, 1968 : Issuance of implementing regulations

by the Department of Transportation (IM 80-1-68).

December 3, 1968: Present suit filed.

April 2-3, 1969: Hearing in the District Court.

July 18, 1969: Order entered dismissing complaint.

Pall, 1969: Federal authorization for construction of

5.

6.

7.

8.

1-77.

9. January 15, 1970, and March 27, 1970: Issuance of new

relocation requirements by the Department of Transportation.

10. May 14, 1970: Opinion of Fourth Circuit Affirming

Dismissal.

11. July 10, 1970: Federal order halting work on 1-77

pending reconsideration of route.

12. July 14, 1970: Denial of Eehearing en ianc.

13. November 6, 1970: Federal authorization to proceed

with construction issued.

14. December 21, 1970: Certiorari granted.

A. Summary of Facts.

1. Charleston, W est Firginia, and the Triangle.

Charleston, the capital and largest city of West Virginia,

lies in a narrow valley, along the Kanawha River, and is

bisected on the east by the Elk River, which joins the

Kanawha near the center of the city. Because the hills

rise steeply from both river valleys, there is a “sparsity of

flat land” in the city for any type of development.®

The Triangle district, located along the south side of the

Elk near its mouth, is the oldest and largest predominantly

Negro community in the state. Many of its residents are

elderly; almost all have comparatively low incomes.^

Urban housing shortage, common in many cities, is par

ticularly severe in Charleston, partly because many homes

have been demolished for public projects.® The impact in

®App. 421a; 419a.

In 1966, the average annual household income for blacks in

the city was more than $3000 below the average income of white

households, a fact resulting largely from job discrimination (PL

Ex. No. 14, p. I-D-6.) The district court took note of this fact.

App. 36a, 314 F. Supp. at 21.

From 1960 to 1966 approximately 1900 low cost housing units

were destroyed, while in the same period the only low cost hous

ing constructed has been 100 units of public housing for the

elderly, while 1500 middle to upper income units were privately

constructed. App. 300a.

In 1966, a study prepared for an urban renewal program esti

mated that total displacements to be caused by public projects in

Charleston would be:

Highway Construction

Urban Renewal

State Capital Expansion

Disaster, Condemnation and

Conversion

1094

755

280

750

Total 2879

PI. Ex No. 14, p. I-D-14. These figures represent family units, and

th ^ the total number of persons is far greater. The planned

urban renewal project was postponed.

the Triangle is even more severe. Land clearance for a

proposed expansion of a local water company, east of the

highway rente, displaced 243 persons a few years ago.®

The planned highway will remove the homes of about 300

more. The proposed urban renewal project, which has

been postponed indefinitely, largely because of the lack of

replacement housing, will, when added, displace almost all

of the district’s 2000 residents.’

Housing discrimination exacerbates the etfect of this

situation on black citizens.® Private discrimination has con

centrated Negroes in only a few areas of the city; the

Triangle is the largest.® As a result, black persons do not

have the same opportunities for finding relocation housing

in the private sector as whites.’®

This situation was recognized by the federal highway

officials in studies of relocation problems made in early

1968, before dislocation had begun. The division right-of-

way officer reported on February 20, 1968 :

. . . [0]ur major area of concern lies with those

people who have income over and above that which

would qualify them for public housing and desire to

rent. More specifically, this area would be defined as

families, with average annual incomes of from $5000

® Def. Ritchie Ex. No. 1; App. 100a.

’ Ibid.; PI. Ex. No. 14, 16, 24.

® This, of course, is in addition to the difficulties arising from the

lower incomes of blacks. See N. 4, supra.

® PI. Ex. No. 23.

’"App. 304a-306a; 331a-338a; PI. Ex. No. 25.

A community worker who made a survey of fifty homes listed as

available for relocation by the State Road Commission found that

of those available and within the financial capability of Triangle

residents, only eight would rent to Negroes. App. 332-335a: PI. Ex.

No. 25.

8

to $7500 a year and who do not want to, or cannot,

buy their own home. Urban renewal and public hous

ing is of little value to our relocation problem in these

cases, and I have reason to believe, that the private

housing market is about saturated presently}'^

He underscored his concerns again on February 26, 1968:

It appears that the relocation problem in the Charles

ton area, insofar as the State Road Commission is

concerned, could become critical in the not too distant

future due primarily to the apparent lack of rental

property in the $60-$90 per month price range. The

available replacement housing in this area is being

depleted and no new sources are available at this

time.^^

Less than 10 days later, on March 6, 1968, after meeting

with State Road Commission, Federal Housing Adminis

tration and Urban Renewal officials, the division right-of-

way officer again expressed alarm that the housing market

was being depleted:

It appears that the Federal Housing Administration

programs will provide the only source of replacement

housing in the area. The existing private market, par

ticularly in low to moderate priced rentals, is being

depleted primarily by Interstate acquisition. It also

appears that future authorization for acquisition will

be affected unless the Federal Housing Administration

programs are instituted in the very near future.^^

PI. Ex. No. 12, App. 93a.

PI. Ex. No. 12, App. 87a (Emphasis added).

PI. Ex. No. 12, App. 97a-98a. The urban renewal program then

contemplated was not approved, with the result that the additional

housing it would provide never came into being.

At trial, the division engineer was asked whether the facts

described in the right-of-way officer’s February and March,

1968 evaluations had changed during the year. The only

change he could cite was the availability of rent supple

ments, provided for under 23 U.S.C. §506(h).^̂

2. 1-77 and the Highway A pproval Process.

The section of 1-77 at issue here is part of the interstate

highway system.” Eoutes 64 from the west and 77 and 79

from the north meet on the north hank of the Elk River,

crossing southeasterly through the Triangle and the rest

of the city as 1-77.” While several alternative routes were

originally considered, at least one of which would have

avoided heavily populated areas, '̂' the state proposed the

^^App. 424a-427a. He emphasized this by saying: “I’m not at

all sure they could have gone through with the relocation program

in the area . . . without these rental supplements.” App. 427a. He

was unable to say what relief would be available when the rent

supplements, which have a statutory limit of two years, expired

for families placed in housing more expensive than they could

afford. App. 428a.

16 responsible federal agency is the Department of Transpor

tation (DOT), acting through the Federal Highway Administration

and the Bureau of Public Roads. Most of the operative work is

carried on by state agencies, in this ease the West Virginia Depart

ment of Highways (formerly the State Road Commission of West

Virginia). The governing federal statute is Title 23 of the United

States Code. The regulations in part are in 23 C.P.R., but are

primarily found in various types of memoranda (instructional,

policy and procedure, or circular) issued by DOT.

The process by which these interstate roads are built involves

both state and federal agencies. The federal government finances

90% of the cost of an interstate highway, while the planning and

construction of highways are state responsibilities. The states

choose the system of routes for development, select and plan the

individual projects to be built, acquire rights-of-way, and super

vise the construction contracts. Thus, the federal agencies finance

the road building, and exercise a veto power over the state’s

activities.

^®App. 41a, 314 P. Supp. at 24; App. 109a, Def. Ritchie Ex.

No. 1.

App. 421a.

10

present route in 1964, and it was approved by the Bureau

of Public Eoads on August 31, 1964.“ Federal authoriza

tion for right-of-way acquisition was given between April,

1966, and May, 1967.” As of the effective date of the reloca

tion amendments to the Federal-Aid Highway Act, 23

U.8.C. ^01 et seq., and indeed, at the time of trial in this

case, the final step in the approval process, authorisation of

construction, had not yet been given.^° Under that statute,

the Secretary is obliged to require “satisfactory assur

ances” of the availability of adequate relocation housing

before he may approve projects under 23 U.S.C. §106.̂ i

“ App. 41a-42a, 314 P. Supp. at 24. On July 10, 1970, as a

result of a public demonstration, a resolution by the City Council

and a recommendation by James D. Braman, Assistant Secretary

of Transportation for Environment and Urban Systems, all ad

vocating a shift of the route one block east into land preAdously

cleared by the water company but not being used, in order to

lessen the impact on the residents, Secretary of Transportation

John A. Volpe ordered work on the road to cease, while the route

was reconsidered. New York Times, Jidy 13, 1970, p. 62, col. 1.

On November 12, 1970, Undersecretary of Transportation John M.

Beggs announced that the route was reaffirmed, and authorized

construction to proceed. Br. App. 45-46; Charleston (W. Va.)

Gazette, November 13, 1970, p. 1.

“ App. 42a-43a; 314 P. Supp. at 24.

App. 132a-137a.

In the past, “plans, specifications and estimates” were required

for actual construction only, since costs of acquiring right of way

were ineligible for federal contributions. 42 Stat. 212. Thereafter,

when acquisition costs became eligible for federal contribution, 50

Stat. 838, the submission and approval of plans, specifications and

estimates were administratively divided into two major stages:

the right of way acquisition stage and the construction stage.

DOT Policy ̂ and Procedure Memorandum 21-5. (Hereinafter

“PPM.”) Right of way clearance is considered part of the con

struction stage. PPM 21-12. Pollowing the approval of plans,

specifications and estimates for a given stage, federal and state

highway officials enter into project agreements limited to such

stage. PPM 21-7. The approval of the construction stage is the

final approval given by the DOT.

11

In the Triangle district itself, only 9 of the 65 parcels

to be acquired had been optioned to the State Eoad Com

mission prior to August 23, 1968, the effective date of the

1968 relocation amendments. Between then and the time

of trial, April 2, 1969, nine additional parcels had been

optioned and one condemnation action had begun.̂ *̂" As

of February 28, 1969, shortly before trial, only 17 house

holds had been moved and some 282 persons remained to

be dislocated.^^’’ At the time the appeal was argued before

the Court of Appeals in May, 1970, petitioners counted

262 persons remaining in the right-of-way. Following the

Court of Appeals’ affirmance, displacement accelerated and,

by July, when the petition for rehearing was denied, 189

persons (150 by federal defendants’ count) remained. A

survey taken by petitioners on December 22, 1970, indi

cated that 65 persons and 14 businesses had not yet been

moved. The state respondents assert that on January 28,

1971, 35 individuals and 5 businesses remain.̂ ®

3. The 1968 Relocation Amendments to the Federal-Aid

Highway Act and the Adm inistrative Regulations to Im

plem ent Them.

Prior to 1962, there was no provision to grant assistance

to persons displaced by federally aided highway construc

tion, beyond the right they might have under state law

relating to condemnation by public agencies. In that year.

Congress enacted 23 U.S.C. §133, requiring the states to

provide “relocation advisory assistance” to dislocatees and

authorizing relocation payments to cover moving expenses.

21̂ PL Ex. No. 4.

Def. Ritchie Ex. No. 1, App. 99a-101a.

“ Response of Respondents Ritchie, et al. to application for in

junction filed in this Court January 30, 1971.

12

where “authorized by State law.” Several studieŝ ® showed

these provisions to be inadequate, as highway officials were

not obliged to curtail their displacement activities even if

they knew that relocation resources were not available.®*

Congress responded to the deficiency in the Federal-Aid

Highway Act of 1968. The new law not only required the

payment of a variety of relocation allowances, which the

states were obliged to permit no later than July 1, 1970,

23 U.S.C. §§505-507, but also a program which assures the

actual availability of adequate relocation housing for dis

placed persons, 23 U.S.C. §502 and §508.®® Section 502 re

quires the Secretary of Transportation to police the ade

quacy of state relocation programs, and prohibits him from

approving any project unless he receives “satisfactory as

surances” that relocation assistance and adequate reloca

tion housing are available. Section 508 requires the state

to ascertain the relocation needs of those to he displaced

and to assure that an adequate amount of satisfactory re

location housing is available.

Under the rule making authority authorized by the stat

ute, 23 U.S.C. §510(b), the Secretary has undertaken to

define the statutory term “satisfactory assurances.” In

structional Memorandum (IM) 80-1-68 issued September 5,

See infra at Br. App. 48-50.

The regulations under section 133 required state highway-

departments to compile information about available public and

private housing opportunities. PPM 80-5(3) (f) 4 and 5.

The Act was specifically made effective on the date of its en

actment, August 23, 1968, except to the extent that states were

unable to comply because of local law, and fully applicable on

July 1, 1970. Pub. L. 90-495, §37, set out as note under 23 U.S.C.

§502.

West Virginia amended its laws to permit full compliance on

March 7, 1969, prior to the hearing in the District Court. W. Va.

Code Ch. 17, Art. 2A, Sec. 20.

13

1968,̂ ® sets out in detail what is required. The key require

ment is that state highway departments prepare relocation

plans presenting relevant factual data pertaining to reloca

tion housing problems and their solutions, which must be

approved by federal officials prior to right of way acquisi

tion and/or construction.^^ The federal officer must then

review the plan to determine whether it “is realistic and is

adequate to provide orderly, timely and efficient relocation

of displaced individuals and families” to satisfactory hous

ing available without regard to race “with minimum hard

ship on those affected.”

A Circular Memorandum (CM) issued by the Bureau of

Public Eoads on February 12, 1969, shortly before the trial

in this ease, stated that the state should undertake the plan

ning required by IM-80-1-68 “on all active projects to the

extent that it is reasonable and proper,” and that to deter

mine this, the local federal officials should review each

project to determine the extent of dislocation remaining,

and to require the planning information where “a substan

tial number of persons remain to be relocated.”

While this case was pending before the Court of Ap

peals, new relocation instructions were issued by DOT.

These were ordered by the Court to he filed as part of the

record, one month prior to argument.®" The changes were

ordered by Secretary Volpe in a memorandum issued Jan

uary 15, 1970, requiring: “Specific written assurances that

adequate replacement housing will he available or provided

for” before approval of all projects and that construction

As amended, Br. App. 17-36.

” IM 80-1-68, Tf7, Br. App. 25-27.

^Ud. f5a(5), Br. App. 21.

Br. App. 39-40.

App. 63a-64a; see also App. 77a, 429 F.2d at 426.

14

“be authorized only upon verification that replacement hous

ing is in place and has been made available to all affected

persons.” The Federal Highway Administration imple

mented this on March 27,1970, in a memorandum applicable

to all projects authorized after May 1, 1970, and to all

previously authorized projects on which persons were not

yet displaced on that date, and requiring that federal offi

cials “shall not authorize any phase of construction . . .

which would require the displacement of individuals or

families” or permit any other dislocation until the person

has obtained for himself or has been offered by the state

adequate replacement housing immediately available.^ ̂ In

affirming the district court’s judgment, the Court of Ap

peals made no reference to the existence or impact of these

new requirements.®*

4. The Relocation “Program ” in the Triangle,

Prior to the relocation amendments, and on the basis of

the DOT study on relocation which had been submitted to

Congress, the Director of Public Roads issued a memo

randum on January 23, 1968, to his regional and state

administrators directing that relocation problems be

studied and considered more intensively.® ̂ Specifically not

ing that legislation was not needed to implement certain

aspects of the study, he stated that “the relocation plan

concept should be implemented particularly in an urban

area where there is a large number of families and busi

nesses to be dislocated.”

Br. App. 41-42.

Br. App. 43-44.

®® Cf. App. 76a-77a, 429 P.2d at 425-426, Sobeloff and Winter,

JJ., dissenting from denial of rehearing en hanc, and discussion

infra at 19-20, 35-37.

®‘‘ CM January 23, 1968, App. 79a-81a (PI. Ex. No. 9.)

Id. at 80a-81a.

15

Studies made by the federal officials in response to this

directive indicated that relocation housing in Charleston

was in fact inadequate to meet the needs of highway dis-

placees.*® Although the federal division engineer concluded

on March 25, 1968, that the State had not satisfactorily

dealt with this problem,” no remedial action was required.”

It was considered sufficient to rely on general assurances

and evidence from past performance.”

Solely in response to this lawsuit,^ the State Road Com

mission prepared a so-called “relocation plan” for the Tri

angle.“ Although the federal officials requested and ob

tained a copy of it, they made no attempt to review it, as

the regulations require.^^

The plan establishes that the overwhelming majority

of Triangle residents are tenants and are poor, with aver-

See supra pp. 6-9.

He wrote;

In the Charleston area the State did secure valuable informa

tion relative to persons to be dislocated by a survey which was

a valuable assist in defining the overall problem involved. It

would not be considered, in our opinion, a complete relocation

plan since it did not provide information either factual, esti

mated or projected as to the availability of replacement

housing.

PI. Ex. No. 9, App. 83a. See also App. 167a-168a.

App. 168a.

” App. 150a-151a; 198a-199a; 226a-227a; 384a-386a; 415a-416a.

« App. 386a.

“ Def. Ritchie Ex. No. 1 App. 99a-126a.

« IM 80-1-68, H7b.

The right-of-way officer stated, “I have not had occasion to

review it in any depth. . . . I have seen it. That’s about all.”

App. 209a. See App. 407a-408a.

16

age rentals about half those in the city as a whole.̂ ® While

containing voluminous but misleading statistics about pub

lic housing in the city,^‘ it only asserted vaguely that the

majority of displacees in the Triangle “appear to be eligible

for public housing.” It contains no information regard

ing the effects of racial discrimination on the availability

of housing.̂ ® Most important, the plan treats the Triangle

in isolation, and makes no attempt to consider the compet

ing and simultaneous needs of the several hundred persons

outside the Triangle who would he displaced hy the same

highway nor those who would lose their homes from other

causes. State Road Commission officials did not consider

competition to be relevant."*̂ As recognized by the Depart

ment of Transportation in its regulations,competition for

App. 101a.

The plan relies on the “turnover” rate in public housing, a

standard discredited in relocation planning, does not consider the

needs of other highway displacees from outside the Triangle, and

makes no finding that residents are indeed eligible under housing

authority requirements. See infra at 47-50.

4S App. 102a.

The state officers relied on the Charleston fair housing ordi

nance to support their view that discrimination was not a factor.

The ordinance, however, does not cover two or three family units

or four family owner occupied units. App. 392a. A survey taken

by a community worker of the housing on a list furnished by the

Road Commission to displacees, showed that over half had been

already rented, and that only eight of those remaining were avail

able to blacks. App. 332a-334a; PI. Ex. No. 25.

’̂ App. 395a.

80-1-68 H7b(3)(b)e(c) Br. App. 27.

17

available units is obviously highly relevant in relocation

planning.^®

B. Summary of Proceedings in the Courts Below.

This action was filed in the United States District Court

for the Southern District of West Virginia on December 3,

1968, three and one-half months after the enactment of the

relocation amendments to the Federal-Aid Highway Act, as

a class action on behalf of all persons living in the inter

state corridor in the Triangle and threatened with displace

ment by the highway.®" It challenges the failure of federal

Petitioners have deliberately confined their discussion of the

facts to those in the record as developed at trial and as presented

to the Court of Appeals. They are aware of the data relating to

relocation that has been presented to this Court by the state in

its response to petitioners’ motion for a stay injunction. They

urge, however, that this data not be considered here in deciding the

case in chief for a number of reasons.

Clearly, most, but not all, of the Triangle residents have been

uprooted and relocated someplace. But this Court does not sit as

a trial court to make findings regarding the factual dispute in this

ease, viz., whether people have been relocated to decent, safe, and

sanitary housing as required by federal statute. It surely cannot

make such findings on the basis of ex -parte and self-serving presen

tations by one of the parties.

With regard to the constitutional issue, the fact that persons

have been relocated somewhere does not mean they have been re

located on a racially nondiscriminatory basis. Placing blacks into

one ghetto from another does not satisfy the dictates of the Four

teenth Amendment, or federal law. Sha-nnon v. Dept, of Housing

and Urban Development,------ F .2 d ------ (3rd Cir. Dec. 30, 1970,

No. 18397.) The factual questions of how people were moved and

to where should be resolved by the district court on remand after

decision by this Court of the legal issues presented by petitioners

and according to valid standards and procedures.

Plaintiff-petitioners Keith Kincaid, Tennis Hogans, Robert

Bayes, Katie Dean, Sedalia Hayes and Lillian Day were all residents

of the corridor at the time the action was filed. The last named,

Lillian Day, is white, and represents the interests of low-income

white displacees. They are joined by the Triangle Improvement

Council, an organization representing' the Triangle community, and

its ofScers.

18

and state officials to assure, in accordance with the reloca

tion housing requirements of the 1968 amendments and the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the

availability of relocation housing on a non-discriminatory

basis for persons evicted from their homes by highway con

struction.® ̂ The defendant-respondents are the federal and

state officials responsible for the construction of the high

way.®̂

To prepare for trial, plaintiffs sought discovery of

pertinent administrative documents from the agencies. The

district court refused to permit any discovery.®® Following

the hearing on plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunc

tion, the case was submitted on the merits.

In its opinion, the court ruled preliminarily that the de

fendants’ objections to reviewability and standing were not

well founded, as the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C.

§701 et seq. authorized judicial review, and the plaintiffs

were “persons affected” by the agency’s actions.®* On the

merits, however, it dismissed, accepting the defendants’

The complaint (App. 9a-21a) also challenged the adequacy of

public hearings on the highway route and the failure of federal

and state highway officials to consider the adverse social effects of

the highway as required by 23 U.S.C. §128. Prior to the hearing on

the motion for a preliminary injunction, the district court limited

petitioners’ proof to the problem of relocation housing (App. 27a,

39a-40a, 44a-45a; 314 P. Supp. at 22, 23, 25.) This limitation on

petitioners’ proof, in effect a partial summary judgment made

without any proceedings to determine whether triable issues of

fact existed, was not appealed.

®̂ The City of Charleston and its officials were also named as

defendants because of their involvement in various programs af

fecting housing. Although they participated in the trial, they did

not appear in the Court of Appeals, and have not yet participated

in the proceedings in this Court.

®® App. 38a-39a; 314 P. Supp. at 22-23.

®*App. 46a-49a; 314 P. Supp. at 26-28.

19

interpretation of the statute, sug’gested by paragraph 5b

of IM 80-1-68, that the requirements for “satisfactory as

surances” of relocation housing, and particularly for a re

location plan, do not apply to projects, like this one, where

authority to acquire right-of-way preceded the 1968 Act.

Without discussing in any detail petitioners’ contention

that this interpretation undermined the clear intent of

Congress, the court held that it had a rational basis, and

should not be disturbed, relying on Udall v. Tallman, 380

U.S. 1 (1965). Finally, although the federal agencies had

contended they were not obliged, in this circumstance, to

review the adequacy of relocation housing, the court under

took independently to make that determination. On the

basis of assurances that the relocation requirements would

be met, it “assume [d] that the highway officials gave these

assurances in good faith,” and found that “adequate reloca

tion housing, on an open racial basis, will be available in

Charleston for an orderly relocation of the displacees from

the interstate corridor.” “ Apparently from the testimony

relating to the relocation plan prepared for the litigation,

and the plan itself,®® it found “that there is ample public

housing in the Charleston area to accommodate the limited

number of individuals remaining in the 1-77 corridor in the

Triangle area.” On the basis of these findings, it dis

missed the constitutional claim, holding that there was no

racial discrimination in the provision of relocation housing

to Negroes.

While the appeal was pending in the Fourth Circuit, the

Department of Transportation issued memoranda on re

location policy which altered the requirements of the earlier

App. 5 6 a -5 7 a 314 F. Supp. at 30-31.

See supra at 15-17.

” App. 57a; 314 F. Supp. at 31.

20

regulations and went far toward accepting petitioners’ in

terpretation of the Act. These documents®* were ordered

to be filed as part of the record on appeal.®® Despite this

fact, and petitioners’ supplemental brief and oral argument

which discussed them, the court made no reference to them

in its one sentence affirmance “on the opinion of the district

court.”

In their petition for rehearing with a suggestion for re

hearing e% banc, petitioners asserted that the district court’s

opinion could not properly be affirmed in light of the change

in the Department’s view of the law, since the lower court’s

ruling had specifically been based on the prior administra

tive interpretation, relying principally on this Court’s

opinion in Thorpe v. Housing Authority, 393 U.S. 268

(1969). Rehearing was denied, again without explanation.® ̂

A dissenting opinion by Judge Sobeloff, joined by Judge

Winter, did suggest the reasoning of the Court and the

majority.®^

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The record in this case reveals both racial discrimination

and a shortage of low cost housing in the Charleston hous

ing market. State and federal action which displaces black

and poor persons into such a market constitutes a violation

of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, since it results

®* See supra at 13-14.

®® App. 63a-64a.

®®App. 65a-66a; 429 F.2d 423.

SI App. 71a; 429 P.2d at 423.

s® App. 72a-78a; 429 P.2d at 423-426. See infra at 35-37.

21

in a denial of equal protection through, the combination of

state and private action. This position is supported by

decisions of this Court as well as those of lower federal

courts in directly analogous circumstances (24-26).

II

A. A constitutional determination is not, however, neces

sary to the decision of this case, as Congress has provided

a statutory remedy to insure that all persons displaced by

federally-aided highway construction are provided with

adequate replacement housing, in the relocation provisions

of the 1968 Federal-Aid High-way Act. The language of

the statute and its legislative history indicate clearly that

Congress intended it to be fully effective immediately. Any

interpretation delaying its effectiveness or diluting its bene

fits conflicts -with Congressional intent (27-30).

By regulation, the Department of Transportation has

implemented the statute by requiring comprehensive re

location planning in order to determine before displacement

the needs of those whose homes will be destroyed and the

resources available to meet those needs. By a technical re

striction contained in its own regulation, the Department

determined that such planning was not required in the Tri

angle because authority to acquire right-of-way had been

given before the effective date of the statute, although only

a small number of persons had actually moved before that

date. The district court accepted this limitation as valid,

although it conflicts with the legislation it purports to

enforce, and indeed -with other portions of the same regu

lation (30-35).

While this case was pending in the Court of Appeals, the

Department issued new relocation guidelines which sub

stantially modified the previous limitations and partially

22

adopted petitioners’ interpretation of the statute. The

Court of Appeals erred in failing to take note of the impact

of this change in the law. Thorpe v. Housing Authority, 393

U.8. 268 (1969). Those guidelines do not, however, yet

fully implement the statute (35-37).

B. Insofar as they did purport to require assurances of

adequate relocation housing for petitioners, the state and

federal officials failed to comply with procedures mandated

by law, relying solely on vague and unsupported assertions.

Where an agency is effectively given the task of policing

itself, in possible conflict with its primary function of build

ing roads, has no internal review procedures for persons

aggrieved by its actions, and has demonstrated impatience

with those who question its conduct, a reviewing court

should carefully scrutinize the administrative procedures.

The district court erred in failing to review the entire rec

ord to determine whether the agency’s conclusion was in

fact supported by substantial evidence, and in relying in

stead on vague tests and oral assurances made during trial,

which had no factual underpinning. Moreover, in making

the ultimate factual determination itself the court usurped

what should properly be an administrative function (38-

46).

The district court’s finding that relocation housing in

Charleston was adequate to meet the needs of petitioners,

in addition to being improperly made, is clearly erroneous.

The court did not require the agencies to supply the infor

mation necessary to support that conclusion, and the bulk

of the evidence which was presented contradicts it. The

finding that public housing alone would be ample fails to

consider the factors of competing displacement, and actual

ehgibility for public housing, and erroneously determines

the availability of such housing (4fi-49).

23

III

A remedy should be afforded to petitioners which will

insure that all those who are entitled to the protections

of the 1968 relocation amendments, both those who are

yet to be moved and those who have been displaced into

demonstrably inadequate housing, are afforded the bene

fits which Congress intended them to have (50-52).

24

ARGUMENT

The Displacement of the Black Petitioners Into a

Racially Discriminatory Housing Market Without Ade

quate Governmental Measures to Assure Non-Discrim-

inatory Relocation Housing Deprives Them of the

Equal Protection of the Laws Guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment.

As the record in this case demonstrates, construction of

1-77 through the Charleston Triangle has had and will have

the effect of displacing black and poor residents of the area

and throwing them into a highly constricted, racially dis

criminatory housing market.

We may assume arguendo, that the discrimination of the

housing market represents private decision m ak in g to ex

clude Negroes from areas reserved for whites, and poor

persons from those reserved for the more wealthy, and not

state action at the point of purchase and rental.®® Never

theless, it is state action which has uprooted the black and

poor jilaintiffs by destroying their homes, and placed them

at the mercy of the racial discrimination and high prices in

siteh hoiising as remains in Charleston.

$tieh governmental action, we submit, violates the Fifth

and Fottrteenth Ameitdments to the United States Constitu-

tiom although at the point of impact, private action is also

present. While “prt''‘'^te conduct abridging individnal rights

does no vioience to the Uqual Protection Clause unless to

some signi&ant extent the $tate in any of its leaxtiiestatioiis

ss A e .gsectatamtiott is bssse* n t race, rc is j f ceturse

nceuthifiei V a ^ JKmer Cv.. ^ 2 U S.

25

has been found to have become involved in it,” Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.8. 715, 722 (1961),

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U.S. 350̂ (1962), the State

and federal governments here are sigTiificant moving forces.

The question is not novel. Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk

Redevelopment Agency, 395 F.2d 920 (2nd Cir. 1968) holds

that governmental relocation which puts minorities at the

mercy of discrimination in the housing market violates the

equal protection clause:

What plaintiffs’ complaint alleges, in substance, is

that in planning and implementing the Project, the local

defendants did not assure, or even attempt to assure,

relocation for Negro and Puerto Rican displaoees in

compliance with the Contract to the same extent as

they did for whites; indeed, they intended through the

combination of the Project and the rampant discrimina

tion in rentals in the Norwalk housing market to drive

many Negroes and Puerto Ricans out of the City of

Norwalk. The argument is that proof of these allega

tions would make out a case of violation of the equal

protection clause. We agree.

Id. at 930. The court also made clear the importance of rec

ognizing the realities of private discrimination:

It is no secret that in the present state of our society

discrimination in the housing market means that a

change for the worse is generally more likely for mem

bers of minority races than for other displaceos. This

means that in many cases the relocation standard will

he easier to meet for white than for non-white dis-

placees.

Id. at 931. Similarly in Arrimglon v. City of Pair field, 414

F.2d 687 (5th Cir, 1969), where state aeiiori was irivolv(fd

26

in the destruction of the homes of Negroes by a private

builder, “the fact that the decision to discriminate may be

made by private individuals rather than a public official is

not decisive,” since, “the City may involve itself in the

discriminatory operation of the private housing market.”

Id. at 692-93.

Such a view of the law is, of course, consonant with

numerous other cases which find denial of equal protection

of the law in a combination of governmental and private

action, e.g. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), (court

enforcement of privately agreed upon restrictive cove

nants) ; Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244, 248

(1963) (“convictions cannot stand, even assuming . . .

that the manager would have acted as he did independ

ently of the existence of the ordinance”) ; cf. Garner v.

Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157, 176 (1961) (Douglas, J., concur

ring) ; Reitman v. Mulhey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967).®̂

Additionally, the failure of the federal officials to take into

consideration the diserimrnatory effects of their programs is a vio

lation of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which requires all executive

departments to act ‘-affirmatively” so as to further the national

policy of fair housing. 12 US'C. §3608(e), Br. App. 16. See

Shatim>n v. Department of Housing and Urban Development, ------

F 'ld ------- 3d Cir.. Dec. 30. 1970. No. 18397). Cf. City of Chicago

Y, FJT.C., 38-5 F.2d 629. 635 (D.C. Cir. 19671:

A regulatory agency may. should, and in some instances must,

g-,ve consaderation to objectives expressed hv Congress in other

l^tsiarion. assuming they can be related to the objectives of

the statute administered hv the agencv.

27

II

The 1968 Relocation Amendments to the Federal-

Aid Highway Act and Regulations Thereunder Grant

Relocation Benefits to the Triangle Residents Which

Have Not Yet Been Administratively or Judicially Ac

corded Them.

Petitioners have argnied in I, supra, that reversal is re

quired because the Triangle residents’ rights under the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution were violated by the State’s failure to provide

an adequate relocation program, in which they would be

free from private racial discrimination. But the Court

need not reach this Constitutional question, since reversal

is independently required by the 1968 Amendments to the

Federal-Aid Highway Act and implementing regulations.

While petitioners contend that the Federal Act and regni-

lations clearly guarantee persons not yet displaced at the

time of the Act’s enactment an adequate relocation housing

program, any ambiguity which may exist must be resolved

by construing the Act and regulations so as to avoid the

necessity for a constitutional adjudication.®^

A. The 1968 Relocation Amendments Assure Persons Not

Yet Displaced as of the Date of Enactment the Right to

Adequate Replacement Housing, and Pursuant Thereto

Mandate Detailed Relocation Plans.

The statutory language makes clear that the 1968 Relo

cation Amendments were intended to protect the rights of

persons not yet displaced as of the time of enactment.

Thus Congress did not, as it had in its first tentative

See, e.g., Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 TT.S.

288, 348 (1936); Crowell v. Benson, 285 U.S. 22, 62 (1932).

28

measure dealing with, highway dislocation/® limit the ap

plicability of the requirements to projects not yet approved.

The Act was declared effective and fully operative on the

date of its enactment.®’ Moreover, the statute defines the

term “displaced person,” the very individual which it seeks

to protect, as:

any person who moves from real property on or after

the effective date of this chapter [August 23, 1968]

as a result of the acquisition or reasonable expectation

of acquisition of such property [for a Federal-Aid

highway] .®*

This interpretation is supported by the legislative his

tory.®® The 1968 Relocation Amendments arose out of

recognition that the federal highway program had previ

ously been wholly deficient in affording protection to per

sons displaced and had therefore resulted in widespread

disruption and misery, particularly in urban areas and

among the poor and minority groups. Further, at the time

the 1968 Relocation Amendments were enacted, 32,000 of

the 41,000 miles of the entire interstate road system had

been constructed or were under construction. Of the 9,000

66 23 U.S.C. §133 (e), Br. App. 2.

6’ Pub. L. 90-495 §37, Aug. 23, 1968, 82 Stat. 831. The one

limiting feature in the act provides that until July 1, 1970, it

“shall be applicable to a state only to the extent that such state is

able under its laws to comply . . .” Ihid.

It should be emphasized that it has never been suggested in these

proceedings that West Virginia’law in any way prevented the state

from complying fully with the requirements of the 1968 amend

ments. See n. 25 supra. Moreover, the Department has determined

that these limitations apply only to relocation payments and not

to the requirements that adequate relocation housing be available.

C.M. December 26, 1968, Br. App. 37-38.

6*23 U.S.C. §511(3).

6® A summary of the relevant legislative history appears at Br.

App. 47-52.

29

remaining miles, 8,500 were in the phases of engineering

design and right of way approval, but construction and

actual displacement had not taken place, since these phases

typically occur years later.®'’'̂ Thus the main dislocation

problem facing Congress and with which it presumably at

tempted to deal was posed by the vast numbers of persons

scheduled to be displaced under highway projects already

approved. Finally, the committee reports and floor debate

relating to the 1968 Amendments reflect Congress’ recog

nition of the urgency of dislocation problems and of the

need to act immediately to remedy them.®®*’ Any interpre

tation making the Act’s protections inapplicable to persons

to be displaced by projects which had already been approved

would defeat the obvious intent of Congress.

The protections afforded by the 1968 Amendments are

detailed in Section 502, which provides specifically that the

Secretary “shall not” approve any project “which will cause

the displacement of any person . . . unless he receives satis

factory assurances from the State highway department”

that:

. . . within a reasonable period of time prior to dis

placement there will be available, to the extent that

can reasonably be accomplished, in areas not generally

less desirable in regard to public utilities and public

and commercial facilities and at rents or prices Avithin

the financial means of the families and individuals dis

placed, decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings, as defined

by the Secretary, equal in number to the number of

and available to such displaced families and indi

viduals and reasonably accessible to their places of

employment.^®

1968 U.S. Code Cong. & Adm. News. 3484.

See Br. App. 47-52.

’»23 U.S.C. §502(3); Br. App. 5.

30

This language clearly calls upon the Secretary to require

the development by State officials of a program satisfac

tory to the Secretary which would guarantee relocation

housing.’^

In order to implement this provision, the Secretary of

Transportation issued on September 5, 1968, a Memoran

dum entitled IM 80-1-68,'̂ ̂ pursuant to his rule-making

The term “satisfactory assurances” in a closely related context

appears first in section 305(a) of the Housing and Urban Develop

ment Act of 1965, Pub. L. 89-117, August 10, 1965, 79 Stat. 475;

42 U.S.C. §1455 (c) (2) which mandates that as a condition of fur

ther assistance “the Secretary [of Housing and Urban Development]

shall require, within a reasonable time prior to actual displacement,

satisfactory assurance by the local public agency” that satisfactory

housing is available for all persons displaced. The House commit

tee report on this section indicates that it was intended to “expand

and implement the existing requirement that there be a feasible

method for the temporary relocation” of urban renewal displacees.

1965 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 2672; see also id. at 2645.

Cf. Western Addition Community Organization v. Weaver, 294

P. Supp. 433 (N.D. Cal. 1968) holding that the failure of the local

agency to prepare and of the Secretary to review a relocation plan

was a violation of the statute, and enjoining the proposed project

until such a plan was submitted to the Secretary and approved

by the court.

That Congress intended Section 502 to require the actual provi

sion of relocation housing is also suggested by an amendment to the

relocation provisions contained in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of

1970. Pub. L. 91-605 §117, Dec. 31, 1970, Br. App. 13-14. That

section authorizes the Secretary to approve the cost of providing

replacement housing for dislocatees where a highway project can

not proceed to construction “because replacement housing is not

available and cannot otherwise be made available as required by

section 502 of this title.” (Emphasis added.)

Br. App. 17-36.

Paragraph 2b(2) of the memorandum states that it is applicable

All Federal-aid highway projects authorized on or before

August 23, 1968, on which individuals, families, businesses,

farm operations, and nonprofit organizations have not been

displaced.

to :

31

authority under the act.̂ ̂ Paragraph 7 of this memoran

dum specifically requires that the State highway depart

ment, “prior to proceeding with right-of-way negotiations

and/or construction shall furnish” a relocation program

plan for review and approval by the division engineer.

The federal respondents suggested in their brief to the Court

of Appeals that this language means that the requirements of the

memorandum are applicable to previously authorized projects only

if no persons had been displaced as of the effective date, and that

since a small number of persons in the Triangle had moved before

August 23, 1968, the requirements have no force here. Federal

Appellees’̂ brief at 21 N. 5. It is submitted that such an inter

pretation is not supported by the language, and is inconsistent with

the legislative history of the 1968 Amendments, and with the

statutory definition of a displaced person as “any person who moves

from real property on or after the effective date of this chapter.”

This position is also in conflict with a circular memorandum issued

February 12, 1969, which states that a relocation plan should be

required on any project where a “substantial number of persons

remain to be relocated.” C.M. February 12, 1969, Br. App. 39-40.

"'23 U.S.C. §510; Br. App. 11.

(Emphasis added.) Specifically, the State highway department

is required to submit the following information for review and

approval:

(1) The methods and procedures by which the needs of every

individual to be displaced will be evaluated and correlated with

available . . . housing. . . .

(2) The method and procedure hy which the State will as

sure an inventory of currently available comparable housing

available to persons without regard to race, color. . . .

(3) An analysis relating to the characteristics of the inven

tories so as to develop a relocation plan which will:

(a) outline the various relocation problems disclosed by

the above survey;

(b) provide an analysis of Federal, State and community

progra,ms affecting the availahility of housing currently in

operation in the project area;

(c) provide detailed information on concurrent displace

ment and relocation hy other governmental agencies or pri

vate concerns;

(d) provide an analysis of the problems involved and

the method of operation to resolve and relocate the relo-

catees . . . (Emphasis added.) IM 80-1-68 jf7, Br. App. 26-27.

32

Having issued IM 80-1-68 in order to implement Section

502, the Department of Transportation was not free to

disregard its requirements^®

However, despite Section 502 and IM 80-1-68, no reloca

tion plan whatsoever with respect to any 1-77 project was

ever required or prepared prior to this lawsuit. Further,

the plan— l̂imited to Triangle—which was prepared in re

sponse to the suit failed to meet the minimal requirements

of the statute and implementing regulation.’®

The district court held that no relocation plan or other

detailed factual demonstration of the availability of reloca

tion housing for the Triangle displacees was required under

the law because authorization to acquire right-of-way on

the projects in the Triangle had been given in 1966 and

1967.” The court relied on jf5h of IM 80-1-68, which pro-

While . . . the Secretary was not obligated to impose upon him

self these more rigorous substantive and procedural require

ments, neither was he prohibited from doing so . . . and having

done so, he could not, so long as the Regulations remained un

changed, proceed without regard to them. Service v. Dulles,

354 U.S. 363, 388 (1957).

The desirability of requiring relocation plans had been recog

nized by the Department of Transportation even prior to Section

502’s enactment. The study prepared by the Department in response

to the congressional mandate contained a recommendation that

state highway departments be required to submit relocation plans

for all projects in large urban areas. Highway Belocation Assist

ance Study, 90th Cong., 1st Sess. at 16-17, 90 (1967). Moreover, in

a memorandum to his regional and local subordinates issued Janu

ary 23, 1968, seven months before the enactment of the statute,

the Director of Public Roads urged that relocation plans be re

quired in urban areas where large numbers of persons would be

dislocated. PI. Ex. No. 9; App. 79a-81a.

” Def. Ritchie Ex. No. 1; App. 99a-126a.

” Significantly the court did not address itself to the meaning of

Section 508 which imposes an independent obligation on the State

to assure the availability of adequate replacement housing.

33

vides that state relocation assurances, which include the

U7 plan, “are not required where authorization to acquire

right-of-way or to commence construction has been given

prior to the issuance of this memorandum.”

Petitioners contend that this ruling constituted reversible

error under the statute and existing regulations.

The sentence of H5b relied on by the district court is

essentially meaningless as written since wherever author

ization to commence construction has been given, authoriza

tion to acquire a right-of-way must also have been given.

The sentence would make sense if the “or” were changed

to “and” so that it read “authorization to acquire right-

of-way and to commence construction.” That this may

well have been the intention is supported by the following

sentence of t[5b which provides that the state “will pick

up the sequence at whatever point it may be in the acquisi

tion program” on the issuing date of the regulations. This

would appear to require that where, as here, the construc

tion phase of the acquisition program had not received

federal authorization as of the date of issuance of IM 80-

1-68, the relocation requirements of T[7 were to apply. This

interpretation of H5b is supported by other sections of that

same regulation which indicate that the relocation protec

tions are applicable where construction or displacement has

not yet occurred.’* Moreover, the court’s interpretation

Thus the regulation is made applicable to all projects author

ized on or before August 23, 1970, on which persons “have not been

displaced” (l[2b(2)), and requires that relocation plans be prepared

“prior to proceeding with right-of-way negotiations and/or con

struction” (117b). (Emphasis added.) The construction phase of

the projects here in issue had not been given approval on effective

date of the statute or the regulation. App. 132a-137a. By regula

tion, right-of-way clearance is a part of the construction stage.

DOT policy and Procedure Memorandum 21-12. No clearance had

taken place in the Triangle by the effective date of the statute or

regulation, nor indeed at the time of the trial seven months later.

34

of T|5b conflicts with memoranda issued after IM 80-1-68

but before this trial which indicate the Department’s recog

nition of its obligation under Section 502 and IM 80-1-68

to require relocation plans for persons not yet displaced

regardless of when right-of-way acquisition or construction

was approved.’®

But even assuming that H5b was intended to permit the

displacement of persons after the effective date of the 1968

Amendments without adequate relocation guarantees, as

the District Court found, then it was in clear conflict with

the statutory purpose and should have been declared null

and void.

In upholding the restrictive interpretation of the statute

contained in H5b, the District Court relied on UAall v. Tail-

man ̂ 380 U.S. 1, 16 (1965): “When faced with a problem

of statutory construction, this Court shows great deference

to the interpretation given the statute by the officers or

A Circular Memorandum to regional DOT officials issued by

the Bureau of Public Roads on December 26, 1968, provides:

Under paragraph 7b(3) [of IM 80-1-68] the division engineer

should insist that the State furnish an analysis of the relocation

problems and possible solutions in sufficient detail to enable

him to determine the advisability of proceeding with the project

and to assure that no relocatee will be required to move unless

there is satisfactory replacement housing available to him.

CM, December 26, 1968; Br. App. 37-38 (PL Ex. No. 3)

(Emphasis added).

A similar memorandum issued February 12, 1969, states that 'while