Bradley v. State Board of Education of Virginia Opening Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bradley v. State Board of Education of Virginia Opening Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1971. 193aaeba-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a9c81cb1-f01c-46eb-9a90-3fd2fef34ba0/bradley-v-state-board-of-education-of-virginia-opening-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

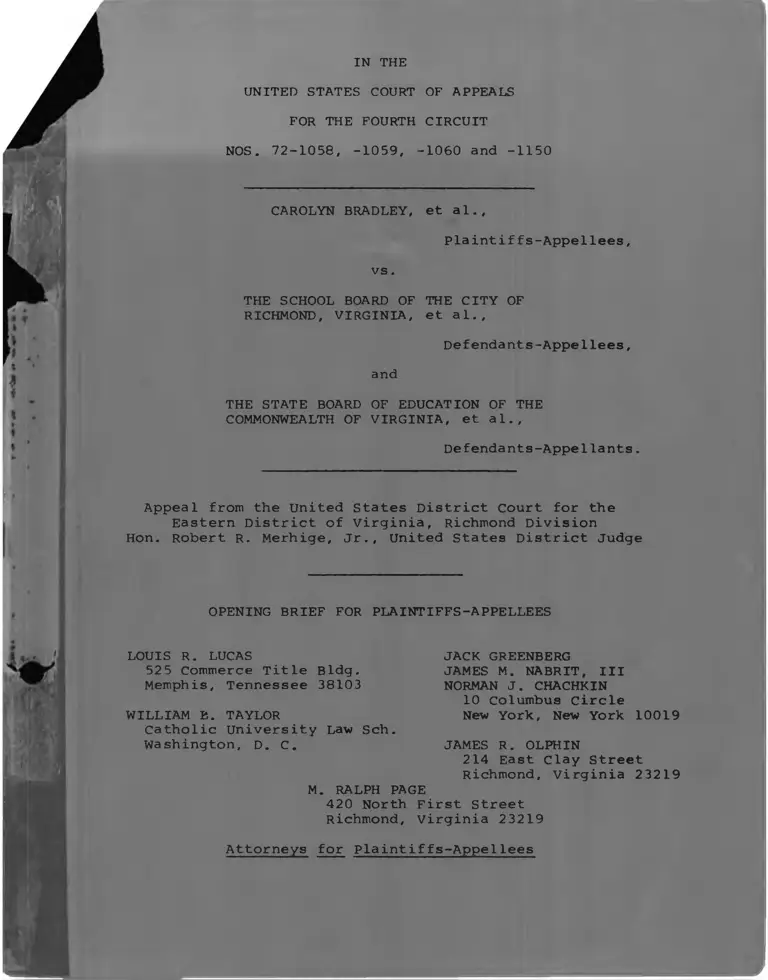

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 72-1058, -1059, -1060 and -1150

CAROLYN BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

vs.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF RICHMOND, VIRGINIA, et al..

Defendants-Appellees,

and

THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division

Hon. Robert R. Merhige, Jr., United States District Judge

OPENING BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

LOUIS R. LUCAS525 Commerce Title Bldg.

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

WILLIAM E. TAYLORCatholic University Law Sch.

Washington, D. C.

M. RALPH PAGE

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JAMES R. OLPHIN214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

I N D E X

Page

Table of Authorities.......................... ii

Issues Presented for Review .................. 1

Statement of the C a s e ........................ 3

Statement of Facts .......................... 8

I. The Violation........................ 9

A. State Educational Authorities . . . 11

B. School Segregation in Richmond,Henrico and Chesterfield ........ 18

C. Demographic Change: The

Influence of School Segregation

and Other Discrimination ........ 25

II. The R e m e d y .......................... 3 3

A. School Division Lines ............ 34

B. The Richmond School Board's Plan . 39

ARGUMENT........................................ 47

The District Court Properly Found That

A Desegregation Plan Not Limited By

School Division Lines Was Required To Vindicate Plaintiffs' Constitutional

R i g h t s .................................. 48

Conclusion...................................... 64

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Adkins v. School Bd. of Newport News,

148 F. Supp. 430 (E.D. Va.), aff'd 246

F.2d 325 (4th Cir.) cert, denied, 355

U.S. 855 (1957) 13

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ.,

396 U.S. 19 (1969) 8

Allen v. School Bd. of Prince Edward County,

207 F. Supp. 349 (E.D. Va. 1962) .................... 9n

Bradley v. Milliken, Civ. No. 35257 (E.D. Mich.,Sept. 27, 1971) ................................ 50n ,51

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 345 F.2d 310

(4th Cir. 1965) 4

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 317 F.2d 429(4th Cir. 1963) 3

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 324 F. Supp.

439 ................................................. 7n

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, No. 71-1900

(4th Cir., March 7, 1972) .......................... 61n

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, Va., 397

F. 2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968) .................. 30n, 52n, 55

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ., No. 71-3028

(5th Cir., Feb. 23, 1972) ........................... 57

Christian v. Board of Educ. of Strong, Civ.

No. ED-68-C-5 (W.D. Ark., Dec. 15, 1969) 56n

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) .............. 55n, 57

Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile,402 U.S. 33 (1971) .................................. 9

Davis v. School District of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp.734 (E.D. Mich. 1970) aff'd 443 F.2d 571

(6th Cir.), cert, denied 402 U.S. 913 (1971).... 52n, 55n

Franklin v. Quitman County Bd. of Educ.,

288 F. Supp. 509 (N.D. Miss. 1968) ................. 55n

ii

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285

(1969) ............................................. 54n

Godwin v. Johnston County Bd. of Educ.,

301 F. Supp. 1339 (E.D.N.C. 1969) .................. 55n

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

Va., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ......................... 4, 9, 57

Griffin v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward

County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ......................... 55n

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ......... 54n

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County,

410 F. 2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969) ..................... 56, 61

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County,

429 F. 2d 364 (8th Cir. 1970) ........................ 61

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

District, 433 F.2d 387 (5th Cir. 1970) .............. 56n

Holt v. City of Richmond, 334 F. Supp. 228

(E.D. Va. 1972) ..................................... 26n

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E.D. Va.)

appeal dismissed, 359 U.S. 1006 (1959) .............. 12n

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School Dist.,

Civ. No. C-70-1331 SAW (N.D. Cal., July 9,

1971) ............................................... 53n

Kelly v. Guinn, No. 71-2332 (9th Cir., Feb. 22,

1972) ............................................... 53n

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala.), aff'd 389 U.S. 215 (1967) .......... 55n

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ....... 62

Lumpkin v. Dempsey, Civ. No. 13,716 (D. Conn.,

Jan. 22, 1971) 58n

McLeod v. County School Bd. of Chesterfield

County, Civ. No. 3431 (E.D. Va.) .................. 5,19

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) .................. 11

NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (E.D. Va. 1958),

vacated on other grounds sub nom. Harrison v.

NAACP, 360 U.S. 167 (1959) ...................... 11, 53n

iii

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis,

Civ. No. 3931 (W.D. Tenn. , Dec. 10, 1971).......... 29n, 53

Plaquemines Parish School Board v. United States,

415 F. 2d 817 (5th Cir. 1969) ........................ 60n

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., Civ. No.

4916 (W.D. Tenn., Aug. 11, 1971) .................... 62

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).................. 31n

Sloan v. Tenth School District of Wilson County,

433 F. 2d 587 (6th Cir. 1970) ..................... 53n,61

Smith v. North Carolina Bd. of Educ., 444 F.2d 6

(4th Cir. 1971)...................................... 60n

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., 311 F. Supp.501 (C.D. Cal. 1970)................................. 53n

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971)................................ passim

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,No. 71-1811 (4th Cir., Feb. 16, 1972), aff'g

328 F. Supp. 1346 (W.D.N.C. 1971) ................... 57

Taylor v. Coahoma County School Dist., 330 F. Supp.

174 (N.D. Miss.), aff'd 444 F.2d 221 (5th Cir.

1971)................................................ 62

United States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County,

423 F. 2d 1013 (5th Cir. 1970)........................ 59

United States v. Board of Education, Tulsa,

429 F. 2d 1253 (10th Cir. 1970)....................... 53n

United States v. Board of School Comm'rs of

Indianapolis, 332 F.Supp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971)...... 53n

United States v. Crockett County Bd. of Educ.,

Civ. No. 1663 (W.D. Tenn., May 15, 1967)............. 61

United States v. Georgia, Civ. No. 12972 (N.D.Ga., Dec. 17, 1970), rev'd on other grounds,

428 F. 2d 377 (5th Cir. 1971) ........................ 55n

United States v. School Dist. No. 151, 286 F. Supp.

786 (N.D. 111. 1967), aff'd 404 F.2d 1125 (7th

Cir. 1968)........................................... 53n

United States v. Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043 (E.D. Tex.

1970) , supplemental opinion 330 F. Supp. 235 (E.D. Tex.), modified and affirmed 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir.),

stay denied, 404 U.S. 1206 (Mr. Justice Black, July

29, 1971), cert, denied 40 U.S.L.W. 3315 (Jan. 10,

1972)............................................ 62, 63

Statutes Page

Virginia Code Ann. §22-7 (Repl. 1969)................. lOn

Virginia Code Ann. §22-30 (Repl. 1969)

(Supp. 1971)............................ 9n, 37, 38, 60

Virginia Code Ann. §22-99 (Repl. 1969)................ lOn

Virginia Code Ann. §§22-100.1, et seq. (Repl. 1969).. 10n,37,

41

Virginia Code Ann. §22-100.9 (Supp. 1971)............. 41

Virginia Acts 1956, S.J.R. 3, p. 1213, 1 RaceRel. L. Rep. 445 ................................... 12

Virginia Acts 1956, Ex. Sess., ch. 68, p. 69,1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1103 ........................... 12

Virginia Acts 1959, Ex. Sess., ch. 32, p. 110 ........ 12n

v

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 72-1058, -1059, -1060 and -1150

CAROLYN BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

vs.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF

RICHMOND, VIRGINIA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

and

THE STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division

Hon. Robert R. Merhige, Jr., United States District Judge

OPENING BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

Issues Presented for Review

When Brown v. Board of Education was decided, 43.5% of

Richmond students were black; all attended completely segregated

schools. In the two surrounding counties, each of which had

approximately half its present population (suburbanization was

just beginning), the 10.4% of Henrico students who were black

and the 20.4% of Chesterfield students who were black also

attended segregated schools.

There followed years of outright state-wide resistance

to any public school desegregation; only the most hesitant

and inadequate steps, the district court found, were taken to

integrate the schools of Richmond and the counties until 1969

or 1970. By that time, the Richmond school division was 70.5%

black while the increasingly populous Henrico and Chesterfield

school systems were less than 10% black; the district court

found these changed circumstances reflected the results of

long-standing policies of comprehensive racial discrimination

by agencies of the Commonwealth of Virginia, including state

and local educational agencies.

1. Did the district court err in requiring a

desegregation plan encompassing the three school divisions,

in order to eliminate all vestiges of State agencies'

discrimination by ensuring that no school therein should remain

racially identifiable?

2. Did the district court err in approving, and

directing the implementation of, the plan submitted by the

Richmond School Board, having found it both effective and

feasible?

2

1/ .Statement of the Case

This suit was commenced in 1961 with the filing of a

Complaint charging officials of the Commonwealth of Virginia,

including the educational authorities of the Richmond school

division, with racial discrimination against black children

(see Appendix A to this Brief: the original and amended

complaints herein). The district court ordered only the

admission of individual pupil plaintiffs to formerly all-white

schools, and this Court reversed — directing the issuance of

an injunction running to the benefit of the entire class.

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 317 F.2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963).

1/ Throughout this Brief, the record of this case (the matter

is before the Court on the original papers) is cited as follows:

Transcript of August and September, 1971 trial, by volume letter and page. E.g., Tr. F 169-70 (Transcript consists of Volumes A-R inclusive).

Transcripts of hearings on procedural matters connected

with trial on plaintiffs' Amended Complaint and Richmond Board's Cross-Claim, or transcripts of June and August, 1970 trial

regarding 1970-71 plan for Richmond, by date and page. E.g.,Tr. 6/26/70 169-70. --

Exhibits received at August and September, 1971 trial, by

party offering and number. E.g. PX 47 (plaintiffs); RX 47

(Richmond Board); CX (Chesterfield Boards); HX 47 (Henrico Boards); SX 47 (State defendants).

District Court's January 5, 1972 Opinion relating to decreefrom which appeal is taken, by typewritten page number. E.g.,Mem. Op. 271.

Other pleadings, orders, etc., by title and date of filing. E.g., Amended Complaint, filed December 14, 1970.

Supportive citations are given both to the record and to the detailed findings of fact by the district court, which are set out

at pages 89-322 of the January 5, 1972 Memorandum Opinion.

3

After further proceedings, the case returned to this Court,

which rejected (Sobeloff and Bell, JJ., dissenting) a challenge

to free transfer desegregation plans and held also that faculty

desegregation would not be required. Bradley v. School Bd. of

Richmond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965). The Supreme Court

accepted review on the faculty issue and reversed. 382 U.S.

103 (1965).

Upon remand, a consent decree was entered which embodied

a freedom-of-choice plan, provided for faculty desegregation,

and obligated school authorities to replace free choice if it

failed to produce results. However, despite continuation of the

patterns of segregation, Richmond school officials took no action,

and on March 10, 1970 the plaintiffs filed a Motion for Further

Relief, relying upon Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968). Following a trial, the district

court on August 17, 1970 entered a decree approving an interim

plan of desegregation for the 1970-71 school year, while

explicitly holding that this plan would not establish a unitary

school system and that further measures, including the increased

use of pupil transportation, would be required. The Richmond

Board was directed to inform the court within 90 days of the

additional steps which would be taken to create a unitary system.

(On November 15, 1970, counsel for the Richmond Board informed

the district court by letter that plans would be filed in

January, 1971.)

4

November 4, 1970, the Board filed a motion to join

additional parties (the School Boards and Boards of Supervisors

2/of Henrico and Chesterfield Counties, as well as their

School Superintendents, the State Board of Education, and the

State Superintendent of Public Instruction) pursuant to Rule 19,

F.R.C.P., on the ground that full and effective relief could

2/ On February 28, 1962, a Complaint charging segregation of

black students had been filed against the County School Board

of Chesterfield county under the style McLeod v. County School

Bd. of Chesterfield County, Civ. No. 3431 (E.D. Va.) (px 147).

A decree was entered in that case on November 15, 1962 requiring

the admission of individual black pupil plaintiffs to formerly

white schools, but the case otherwise lay dormant. Although the

county initially submitted the decree to the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare to indicate its compliance with

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Mem. Op. 196; PX 118, p. 123), it

subsequently adopted a freedom-of-choice plan (Mem. Op. 197;

PX 118). Under this plan, Chesterfield County schools remained

racially identifiable (Mem. Op. 200, Appendix A(3)). All

formerly black schools, with the exception of the Matoaca

Laboratory School, were then closed (Id. at 197-98). The district

court denied a motion to consolidate McLeod with Bradley, filed

on behalf of the plaintiffs in the former case, as untimely filed (Tr. A 16).

Prior to joinder herein, Henrico County school authorities had not defended desegregation litigation, but the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare commenced enforcement proceedings

in 1968, leading to the adoption of various desegregation measures (Mem. Op. 161-62; PX 75, 76, 123; see Mem. Op. Appendix A (3)).

Formerly black schools were closed, as in Chesterfield county

(Mem. Op. 208-09; PX 120, pp. 318-22) and in September, 1971,

after joinder herein, the Central Gardens Elementary School, which

had been over 90% black, was grouped with four neighboring white

schools for purposes of desegregation (Mem. Op. 210; HX 26g;Tr. H-107).

In 1970 at the time of the filing of the motion for further

relief, and at the time the motion for joinder was filed and

granted, none of the three school divisions operated a school

system without racially identifiable facilities (Mem. Op. 66-67,

200-02, 210-12, Appendix A(3); 317 F. Supp. 555; 325 F. Supp.828) .

5

not be granted to the plaintiffs without the joinder of these

3/parties.

3/ On June 25, 1970, Dr. Thomas Little, Associate Superintendent of the Richmond public schools, testified on cross examination

that if he were directed to develop an optimum desegregation plan

for Richmond, such a plan would involve an area larger than the

Richmond City school division:

Q. Dr. Little, assuming transportation of pupils,

is there any way to achieve what you consider to be,

as an educator, an optimum of desegregation in the

Richmond area?

A. In the Richmond area, yes.

Q. How would you do that?

A. It would involve the involvement of a larger

area than the present city boundaries of the

City of Richmond.

Q. Are you talking about Henrico County,

Chesterfield County, or both?

A. Henrico County, Chesterfield County, and the

possibility of the general metropolitan area,

maybe bordering on, in other counties other than

Henrico and Chesterfield. Basically, the problem

could be solved within the City of Richmond,

Henrico and Chesterfield Counties. (6/25/70

Tr. 1122-23).

June 26, 1970, the district court rejected an HEW-prepared plan

submitted by the Richmond School Board, and required submission

of a new plan (Mem. Op. 4; 317 F. Supp. 555, 559-60, 572). On

July 2, 1970, plaintiffs filed a motion to require the Richmond

school authorities to acquire sufficient transportation facilities

in order to insure their ability to carry out a truly effective

plan. The district court denied the motion in a letter to

all counsel of July 6, in which he expressed his confidence that

the Richmond school authorities would take the necessary steps

to prepare and implement an adequate desegregation plan. Responding

to Dr. Little's testimony, the letter suggested, among other

steps to be taken by Richmond authorities, that they might wish

to inquire into the possibility of voluntary cooperative

desegregation agreements with the surrounding school divisions.

On July 23, 1970, when the interim plan was submitted (Mem. Op.

18; 355 F. Supp. at 572), the City Council of Richmond filed a

motion for leave to file a third-party complaint against the(cont 'd)

6

The district court granted the motion and directed the

plaintiffs to file an amended complaint setting forth whatever

3/ (cont'd)

Counties of Henrico and Chesterfield. This motion was withdrawn after the district court made the following comments:

Well, now, gentlemen, perhaps we can save

some time on that. Let me give you some brief

thoughts. If anybody is so naive as to think

that this Court, by virtue of suggestions to

counsel under the Court's obligation, has

suggested any lawsuit be brought by a school

system that is admittedly, has admittedly been

operating in violation of the Constitution,

a suit against school systems that, so far as

I know, are not engaged in any litigation and

apparently, I assume — I don't know anything

about the operation — but I assume they are

operating constitutionally viable or somebody

would have been after them. Now if anybody

thinks this Court suggested such a lawsuit, they

are just as sick as sick can be.

The Court suggested that counsel might consider

— I want to be careful now because I attempted

to come as close to the quote of the Chief

Justice of the United States as possible without

actually stealing his words, so to speak — suggested they might consider the feasibility

of discussions or negotiations, or something.

I have forgotten the exact phraseology. The thought occurred to me from the Northcross case

that you have mentioned, Mr. Mattox, in which

the Chief Justice of the United States says

there are still unanswered questions, including

the propriety of consolidating districts and

whether the Court has a right to do it, and that sort of thing. So I want to get it in

the proper perspective.

If anybody thinks I suggested such a complaint,

they are very, very foolish. They are wrong.

It is one thing to sit down and talk to folks

and it is another thing to drag them into court.

(8/7/70 Tr. 36-38).

After the motion for joinder was filed in November, 1970, the

added defendants sought recusal of the district judge on the

theory that he had prejudged the issue by suggesting the voluntary

inquiry referred to above. The district court properly denied that motion to recuse. Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond. 324 F.Supp. 439. 7

claims they might have, if any, against the joined defendants

(Mem. Op. 20; 51 F.R.D. 139) (see Appendix A to this brief).

Following the denial of various procedural motions (Mem. 20;

324 F. Supp. 396; 324 F. Supp. 401), trial of this cause was

held August 16-20, 23-27, 31 and September 1-2, 7-10 and 13,

1971. On January 5, 1972, the district court issued its opinion

granting relief, directing the merger of the three school

divisions, and ordering implementation of the plan prepared by

the Richmond School Board (unless a better plan is submitted to

the district court). The State and County defendants appeal

from that decree.

Statement of Facts

This is an appeal in a school desegregation action whose

object is the formulation of effective and appropriate means

to eliminate, "now and hereafter," Alexander v. Holmes County Bd.

of Educ., 396 U.S. 19, 20 (1969), the vestiges of the dual school

system for black and white pupils still maintained by the

Commonwealth of Virginia. The district court was necessarily

concerned, therefore, with determining (a) the existence and

extent of the federal constitutional violation by the

Commonwealth and its constituent agencies, Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 15-16 (1971), and (b) the

efficacy and feasibility of any proposed relief to bring about

"the greatest possible degree of actual desegregation, taking

into account the practicalities of the situation," Davis v.

8

Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971)

so as to eliminate the dual school system "root and branch,"

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430,

438 (1968).

I. The Violation

As in other states, the administration of public education

in Virginia is shared between local school authorities and

4/

central state officials, in this instance the State Board of

Education and its agents, the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction and employees of the State Department of Education.

The basic unit of Virginia school administration is the school

division, which under current law must consist of not more than

one city or county, absent local consent and State Board

ratification of larger units.

4/ See Allen v. School Bd. of Prince Edward County, 207 F. Supp. 349 (E.D. Va. 1962).

5/ Prior to the amendment of the statute in 1971, after the

joinder motion had been filed herein, see p. 38 infra, Virginia law (Va. code Ann. §22-30 (Repl. 1969)) had provided for school

divisions of at_ least one county or city, with no county or city

to be divided among more than one school division.

The law's focus upon other governmental entities — cities

and counties -- and their establishment as the smallest operating subdivision of the educational structure, dates to 1922, when the

system of individual school districts congruent with magisterial

districts was abolished, pursuant to an earlier recommendation of

the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, in order to

eliminate "[pjurely artificial differences" among the various

districts. Annual Report of the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction, 1917-18, p. 14 (PX 124). (cont'd)

9

The history of desegregation efforts since Brown v. Board

of Education, both throughout Virginia and in the Counties of

5/ (cont'd)

Since that time, further consolidation into larger units of

school administration has been consistently recommended. In 1944

[t]he [State] Superintendent presented a long-

range plan for the consolidation of school divisions

with a view to greater efficiency in the adminis

tration of school affairs. This plan would call

for the creation of between 50 and 60 school

divisions in the state to replace the present 110

divisions, and would involve the creation of

division boards of education, the membership of

which would be based upon the school population

in the counties, or in the counties and cities,

comprising a division. The board looked with

favor upon the general plan, subject to the

working out of details.

(Minutes of the State Board of Education, August 24-

25, 1944, RX 82, p. 1; Mem. Op. 95.)

In 1969, the State Board resolved:

The State Board, therefore, has favored in

principle the consolidation of school divisions

with the view to creating administrative units appropriate to modern educational needs. The

Board regrets the trend to the contrary, pursuant

to which some counties and newly formed cities

have sought separate divisional status based on

political boundary lines which do not necessarily

conform to educational needs.

(Minutes of the State Board of Education, January 3,

1969, RX 82, p. 20) (emphasis supplied).)

Virginia law provided for the operation of joint schools by

two or more school divisions, Va. Code Ann. §22-7 (Repl. 1969),

for the furnishing of educational services to a city school

division by a county school division pursuant to contract, Va.

Code Ann. §22-99 (Repl. 1969) and for the consolidation of

school divisions under a single school board, Va. Code Ann.

§§22-100.1 et seq. (Repl. 1969), as well as for the education of

pupils of one division by another on a tuition basis. However,

these provisions have never been utilized to further desegregation

but rather only to accomplish segregation. See Mem. Op. 170-73,

177-80; RX 82, pp. 11-12; PX 94, pp. 4, 7-8, 20, 30-31, 34-35, 39-41, 45, 49, 50, 47, 60; PX 109; PX 119, pp. 15, 19, 23; PX 122, pp.

70a-71.

10

Henrico and chesterfield and the City of Richmond, demonstrates

that the actions and decisions of local and central state

authorities have, singly and in combination, retarded the

process of integration, further entrenched the dual system

of education for black and white children and contributed

substantially to the present school attendance patterns in

6/the Richmond metropolitan area.

A. State Educational Authorities

The district court's opinion sets out in graphic detail,

as extensively supported by the record, the history of the

State's official reaction to Brown v. Board of Education and

to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It is an understatement to say

that the Commonwealth of Virginia massively resisted the imple

mentation of desegregation following the Supreme Court's decision

in Brown. Every available State resource was enlisted, including

the services of the legal officers of the State (Mem. Op. 154,

156; PX 122, pp. 287-88, 304; c_f. NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp.

503 (E.D. Va. 1958) (three-judge court); NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S.

415 (1963)), the State Police (Mem. Op. 138; PX 144, p. 122),

the tremendous financial resources of the Commonwealth (e_.c[. ,

Mem. Op. 168; PX 149) ($770,000 expended from one State fund

6/ "The Court finds that the officials of the City of Richmond,

Counties of Chesterfield and Henrico, as well as the State of Virginia, have by their actions directly contributed to the con

tinuing existence of the dual school system which now exists in

the metropolitan area of Richmond" (Mem. Op. 195).

11

to pay half of fees of private counsel defending school desegre

gation cases), and the power and prestige of the office of the

7/Governor (Mem. Op. 154, 160).

As the opinion below points out, even prior to the adoption

of interposition (Va. Acts 1956, S.J.R. 3, p. 1213, 1 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 445) and other massive resistance legislation by the

General Assembly of Virginia, the State Board of Education

directed local school authorities to continue to assign pupils

in accordance with Virginia's segregation statutes until such

time as the General Assembly should amend the law to provide for

desegregation (Mem. Op. 136-37; RX 82, 83; PX 119, pp. 42-43;

PX 122, pp. 161-64; Tr. F 110-13, 161-62). While such amendments

were never adopted, the State Board of Education never changed

8/its instructions to local school authorities.

In 1956 the Governor was authorized to close any school

which became integrated, Va. Acts 1956, Ex. Sess., ch. 68,

9/

p. 69, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1103. At the same time, the Pupil

7/ The State Department of Education gave wide circulation to

speeches and statements by Virginia governors opposing desegregation. See PX 122, p. 327; RX 83, pp. 38-41.

8/ As Assistant State Superintendent Blount put it, the State

Department of Education operated in accordance with Virginia

statutory law — in spite of the import of Supreme Court decisions

— at least until execution of a compliance agreement with the Department of HEW in 1965 (Tr. M 196-97).

9/ The Attorney General issued opinions explaining the law in

1957 and 1958 (Mem. Op. 137-38, Appendix B; PX 144-1). After the

statute was declared unconstitutional in James v. Almond, 170

F. Supp. 331 (E.D. Va.), appeal dismissed, 359 U.S. 1006 (1959),

local boards were authorized to close schools to which any federal

or state troops, military or civil, were sent. Va. Acts 1959,Ex. Sess., ch. 32, p. 110.

12

Placement Board was established as an independent state body with

plenary power over the assignment of all school children in

1 0/the Commonwealth; it continued in existence until 1968

(Mem. Op. 135; PX 122, p. 172; see Tr. H 58-59). The Board

was recognized by State officials as a device to prevent

integration (PX 144-F). See generally, Adkins v. School Bd.

of Newport News, 148 F. Supp. 430 (E.D. Va.), aff1d 246 F.2d 325

(4th Cir.), cert, denied, 355 U.S. 855 (1957).

The State Department of Education disseminated information

concerning Pupil Placement Board procedures to local school

officials and its employees also served the Board (Mem. Op. 138-

39; PX 122, p. 171; Tr. 1-152); in 1961 criteria essentially

identical to those of the Pupil Placement Board were promulgated

by the State Board of Education for use by localities which

wished to reassert their power to assign school children (Mem. Op

139-40; PX 122, p. 218; Tr. G 48, P 146).

Two other extensive programs for segregation were adminis

tered by state authorities; tuition grants and pupil

10/ For example, a December 29, 1956 telegram from the PupilPlacement Board to then Chesterfield Superintendent of Schools

Fred D. Thompson began: "Under the provisions of Chapter 70,

Acts of Assembly, extra session of 1956 effective December 29,

1956, the power of enrollment or placement of pupils in all

public schools of Virginia is vested in the Pupil Placement Board

The local school board. Division Superintendents, are divested

of all such powers" (emphasis supplied) (Tr. F 105-06; PX 122,

p. 91).

13

11/

scholarships. The State Board and Department played an

instrumental role in the operation of the tuition grant scheme

(cf. Memorandum No. 3713, Mem. Op. 142; PX 122, p. 198) and the

State Department of Education reimbursed local divisions for the

12/State's share of the grants. Until its termination in 1970,

state and local agencies expended almost $25 million under the

program (Mem. Op. 148; PX 110-12), including retroactive grants

to Prince Edvard County parents (Mem. Op. 145; PX 119, pp. 87-88).

The extensive state-wide use of the grant and scholarship

programs to promote segregation is revealed in the examples

set out in the district court's opinion at pp. 177-80, extending

from the programs' inception until at least 1969 (PX 94, 110,

1 1 1 ) .

Joint schools established to serve black students from

different school divisions continued to operate with State

sanction as late as 1965-68 (RX 86; PX 109A); the State Board

11/ The tuition grant law was originally adopted by the 1956

Legislature which passed the school closing laws. Prior to the

1958 school year, the State Board of Education issued regulations

to implement the statute, which provided reimbursement for

tuition paid in order to attend another school division if a

pupil was assigned to an integrated school or one which had been

closed by order of the Governor (Mem. Op. 141-42; PX 122, p. 181, 188).

12/ The program was expanded in 1960, pursuant to legislation, to

include payments to private schools (Mem. Op. 143-44; PX 122, p.

210). The new law required the State Department of Education not

only to reimburse localities for the State's share of grants or

scholarships, but in the case of divisions which refused to parti

cipate directly in the program, to make grants directly to parents

and withhold an equivalent loca1 share from other state aid funds

due the division (Mem. Op. 144; PX 119, p. 74; PX 122, pp. 225-26).

14

specifically approved construction at one such school after

Brown (Mem. Op. 172; PX 109; PX 119, p. 44).

In addition to the administration of specific segregation

programs, every supervisory function of the State Department of

Education was influenced by Virginia's commitment to segregation.

The Department has had the authority and the obligation for a

considerable number of years to review and approve all school

construction plans of local school divisions based on such factors

as proposed size and site location (Mem. Op. 107-09; RX 83,

p. 26; PX 122, pp. 63, 115-19, 158; Tr. F 82). Both before and

after Brown v. Board of Education — and continuing after the

passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the execution of

the compliance agreement between the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare and the Virginia State Department of

Education — the construction plans of local school districts

were never considered in light of their effect upon desegregation

13/(Mem. Op. 109; Tr. F 86-87). In fact, the State Department

of Education routinely continued to approve construction

applications from local school divisions which contained outright

racial school designations, at least through the 1965-66 school

13/ The current school planning manual of the State Board of

Education still does not include promotion of desegregation as

one of the factors to be considered in selecting sites for new

school construction (SX 4, §10.31).

15

14/year (Mem. Op. 109; Tr. F-84). Segregated state-wide

meetings of personnel were held well after 1954 and, in fact,

on at least one occasion after the compliance agreement with

HEW was executed in 1965 (Mem. Op. 152; RX 83; PX 122, p. 251).

The Department continued to approve the operation of regional

joint schools for black students as late as 1968 (Mem. Op. 172;

PX 109; PX 119, pp. 15, 19, 23; Tr. F-131-33). The state

continued to administer the pupil scholarship or tuition grant

programs, which allowed students to attend public schools

outside their own school division, until 1970, when the General

Assembly terminated funding for the programs (Mem. Op. 147;

PX 112).

After 1965 (when the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction executed a compliance agreement with the United

States Department of Health, Education and Welfare, in order

to retain eligibility for federal aid) (Mem. Op. 152), there

was no effort by state authorities to initiate the changes

necessary to bring about an end to the dual school system in

14/ The only action of the State Department of Education with

respect to school construction that related to the desegregation

process was the circulation to local division superintendents of

an HEW memorandum dealing with the necessity to consider furtherance of desegregation in construction planning (Mem. Op. 111-12;

PX 122, pp. 345-46), but this consideration was never made part

of the State’s approval mechanism (Tr. F-86-87). And see n. 13 supra.

16

15/

Virginia. As the district court found, prior to the passage

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, there was no official in the

State Department of Education assigned to assist local school

divisions in achieving desegregation and clearly no effort was

made to encourage local school divisions to end the dual school

16/system (Mem. Op. 151; Tr. I 129-33). Dr. Elmore, the

individual within the State Department of Education who in 1964

assumed a liason role with HEW, took what can only be charac

terized as a negative attitude towards the performance of his

duties (Mem. Op. 163-64). He expressed himself opposed to the

HEW guidelines (Mem. Op. 155-56, 162-63; RX 87; PX 123; PX 136A;

Tr. I 136-39) and on at least one occasion attempted to interfere

with the execution of HEW enforcement responsibilities by

suggesting to his superior, Dr. Wilkerson, that no effort be

made on the part of state officials to supply requested

information to HEW and that local officials not be compelled to

do so (Mem. Op. 162-63; RX 87). Elmore admitted that the state

15/ In 1971 the State Board of Education still denied it had an

affirmative duty to assist in the creation of unitary systems

throughout the Commonwealth (Answer to Amended Complaint, f 11,

filed January 15, 1971). Compare PX 96, wherein the Assistant Attorney General of the United States expressed the view to State

Superintendent Wilkerson on July 2, 1970 "that the State Board of

Education is the appropriate agency to be called upon to adjust

the conditions of unlawful segregation and racial discrimination

existing in the public school systems of Virginia, set forth in

the attached list" (Tr. G 71-72).

16/ As late as 1965, the State Department of Education held

racially segregated personnel conferences (Mem. Op. 152; PX 122,

p. 251) and distributed official speeches of the Governor opposing

the HEW guidelines and the federal enforcement effort (Mem. Op. 160;

PX 122, 327; RX 83, pp. 38-41). There never has been a like

distribution of Supreme Court decisions or those of lower courts with jurisdiction over Virginia which have laid down principles

of desegregation (Mem. Op. 168; Tr. I 204).

17

had never used its powers to compel compliance with the require

ments of the Fourteenth Amendment (Mem. Op. 166; Tr. I 168;

see, e.g., Mem. Op. 161; Tr. I 171).

After one of the private attorneys retained by the State

in 1965 to assist localities in their negotiations with HEW

reported that in light of HEW1s expected decision to disapprove

free choice plans which did not produce meaningful results,

local school divisions should prepare to utilize alternative

methods of desegregation (Mem. Op. 157-58; PX 95), no

recommendation along these lines was ever made by the state

authorities to local school divisions (ibid.). Federal funds

to provide technical assistance in the desegregation process

through the facilities of state departments of education were

available for five years, but it was not until 1971 that Virginia

employed a professional to fulfill these functions. The State

Department looked on complacently as black faculty members and

administrators were systematically removed from their positions

during the desegregation process although required statistical

reports would have revealed the phenomenon (Mem. Op. 168-69;

PX 139; Tr. M 171-77).

B. School Segregation in Richmond, Henrico and Chesterfield

The actions and failure of initiative on the part of the

State Department of Education are reflected in the history of

these three school divisions. Following Brown v. Board of

18

Education, no effort was made in either Chesterfield or Henrico

County, or the City of Richmond, to implement the decision until

lawsuits were started or federal funds were imperiled.

(1) In 1955 and 1959 the educational and civil authorities

in Chesterfield County, by resolution, opposed the Brown decision

and any implementation of integration in the County (Mem. Op.

194-95; PX 117, pp. 82, 97; PX 118, pp. 76-79, 82). Although

Chesterfield school authorities were ostensibly divested of

their power to assign students in 1956 (see n. 10 supra), at

the time the Pupil Placement Board was established, the Chesterfield

Board willingly acceded (Mem. Op. 195-96; PX 118, pp. 91-92);

the initial decree in the McLeod case ran against both the local

school officials and the Pupil Placement Board. In 1966 the

School Board adopted a freedom-of-choice plan which failed,

however, to change the racial character of any of its schools;

as late as 1968-69, nine Chesterfield County schools were

17/attended only by black students (Mem. Op. 199; PX 102).

17/ Consider the following table (PX 102):

School Year % of Elementary Stu- % of Black Elementary

dents Who Were Black Students in Black Schools

1966-67 10% 80%

1967-68 10% 7 5%

1968-69 8% 60%

1969-70 8% 3 3%

- 19 -

Chesterfield County was notified on July 16, 1968 that

it faced possible termination of federal assistance by the

Department of Health, Education and Welfare because the dual

school system was found to have continued in existence (Mem. Op.

197; PX 118, p. 214). In 1969 and 1970 all of the formerly

black schools operated by the chesterfield County School Board

were closed (Mem. Op. 197-98; PX 118, pp. 217-18) but the

following year, nine chesterfield County schools still had no

black faculty members assigned to them (Mem. Op. 198, Appendix

A (3); PX 102). At the time of trial, the Matoaca Laboratory

School, which served primarily the children of faculty members

of Virginia State College at Petersburg, but which historically

had been treated as a part of the county school system (sup

ported by contribution of ADA money from Chesterfield County),

remained an all-black school (Mem. Op. 199-202, Appendix A(3);

PX 102; PX 141a).

(2) No desegregation plan was adopted in Henrico County

until 1965, when under HEW prodding, a restricted freedom-of-

choice plan was proposed (Mem. Op. 206; PX 120, pp. 212, 218,

267, 285-89). This plan, like the one adopted in Chesterfield

County, proved unavailing to eliminate the segregated patterns

of school attendance (Mem. Op. 207) ("in fact and law, . . . a

20

18/dual system"). In 1966 and 1967 the school board refused to

confer with representatives of the Department of HEW, and in

1968 administrative enforcement proceedings were commenced

(Mem. Op. 161-62, 207; PX 120, pp. 260-61, 279-80; PX 123, pp.

75-76). In November, 1968, the School Board proposed to close

its formerly black schools upon condition that the HEW enforcement

proceedings be terminated (Mem. Op. 208; PX 120, pp. 318-19,

321-22). On January 2, 1969 HEW accepted the Henrico plan and

in September of that year all formerly black school facilities

were closed and most of the county's black principals reassigned

to other and lesser positions (Mem. Op. 208-09, Tr. N 73-75).

Many of these schools were subsequently reopened and re-named

as annexes to formerly white schools (Mem. Op. 209, Appendix

A (3) ; PX 103; PX 116).

However, the zone lines drawn by Henrico school authorities

for the remaining schools left the Central Gardens Elementary

School over 90% black (Mem. Op. Appendix A (3)) although the

distribution of population in the area would have led one to

predict that black students would be found in significant

18/ The extent of segregation is indicated by the following

table (PX 103, PX 116):

School Year % of Elementary Stu- % of Black Elementarydents Who Were Black Students in Black Schools

1966-67 8% 65%

1967-68 7.8% 50%

1968-69 8.4% 80%

1969-70 8. 5% 38%

- 21 -

numbers in the surrounding school facilities as well as in the

Central Gardens school (Tr. Q 55-58). As the black student

enrollment in the facility had increased, the school was staffed

by an increasingly black faculty assigned by the County

authorities (Mem. Op. 210, Appendix A (3); PX 103; PX 116).

After continued HEW pressure (Mem. Op. 209-10; HX 26a; PX 120,

pp. 352-53) and after the joinder motion herein had been granted,

the Henrico Board determined to pair Central Gardens with four

other schools beginning in the 1971-72 school year (Mem. Op.

210; HX 26g; Tr. H 99-109). As late as the 1970-71 school year,

ten Henrico County schools had no black faculty members; currently

there is only one black faculty member at some twenty-five

County schools and not all of these are classroom teachers to

whom students are necessarily exposed (Mem. Op. 212; PX 116;

Tr. N 98-99, 101).

(3) The history of desegregation in Richmond is very much

the history of this case. See pp. 3-8, supra. Implementation

of the interim plan within the City of Richmond for the 1970-71

school year left over 19 schools segregated (Mem. Op. 18-19,

Appendix A (3)); in its order approving the interim plan for

that year only, the district court specifically found the plan

inadequate to establish a unitary school system, 317 F. Supp.

555, 576. And while at the time of the hearing on the

metropolitan remedial aspects of this case, the district court

had already entered its order directing the implementation of

22

Plan III within the city for the 1971-72 school year, that

decree was entered with the specific caveat that the plan's

adequacy was being judged in light of the parties and issues

before the court and without prejudice to later determinations

when the joined parties had had an opportunity to litigate

the new issues. 328 F. Supp. 828, 830 n. 1.

While the public schools of the three divisions were never

closed and subjected to central state control because of

integration, the steps taken by State authorities were not

without long-lasting effect upon the schools in the area.

The State Pupil Placement Board, for example, was vested with

the power to assign all students to the public schools of

Richmond, Henrico and Chesterfield Counties, and in fact had

such power at the time this lawsuit was originally commenced

in 1961 (see Appendix A). That power was consistently exercised

to frustrate desegregation and continue dual school systems

insofar as possible. During the life of the tuition grant

and pupil scholarship programs, students in the three divisions

utilized the device to attend other schools; from 1965 to 1971

alone, grants totalled $462,000 in Chesterfield County, $286,000

in Henrico County, and $97,000 in Richmond. The three divisions

have expended nearly $1.7 million (including State reimbursements)

for tuition grants since the Brown decision (Mem. Op. 147-50;

PX 112; PX 117; PX 118; PX 120).

Similarly, the services of the State Department of Education

were utilized by the local divisions for the purpose of segregation.

23

For example, in 1957 and 1963, employees of the State Department

of Education prepared segregated bus routes for Henrico County,

including routes as long as twenty miles one way for black

students (Mem. Op. 94; PX 120, pp. 102-38). Particularly

significant were the school construction programs carried out

with State Board approval after Brown. All of the construction

in the three school divisions from 1954 to the present conforms

to racial residential patterns and was planned for segregated

use.

In Henrico County, school construction planning in 1955

included the preparation of spot maps by race (Mem. Op. 114;

PX 120, pp. 86-87, 89, 91) and selection of names for "Negro

schools under construction" (Mem. Op. 113; PX 120, p. 50).

Applications to the State Board of Education for approval of

proposed black school construction in 1957, 1958, 1960 and 1963

bore racial designations and were accompanied by statements in

justification of the proposals which referred to anticipated

19/

increases in black population (Mem. Op. 114-17; RX 90).

19/ For example, an addition was suggested in 1957 at the

Henrico Central Elementary School, which was referred to as the

"Varina Negro School." The white Varina Elementary School is

located less than a mile away. And in 1963 permission was

sought to construct an addition to Fair Oaks Elementary School

because a "Negro subdivision" was being constructed near several

white elementary schools, Fair Oaks being the closest black

school (RX 90).

24

On the other hand, during this period — from 1954 to 1971 _

31 new schools and additions to 36 schools were constructed

by the county. With the exception of one, all opened as

identifiably black or white schools (Mem. Op. 120-23; PX 103;

HX 70).

Likewise, Chesterfield County continued an uninterrupted

practice of racially planned school construction after 1954.

Racial designations appear on applications submitted in 1958,

1959, 1962, 1964 and 1965 to the State Department of Education

for black schools (Mem. Op. 128-33; RX 92; PX 117, p. 133;

PX 118, pp. 107, 111-12, 116, 132, 137, 169). A total of

33 new schools were built in Chesterfield County from 1952 to

1972 (including two schools which opened in 1971), but none

were planned with a view towards aiding in desegregation

(Mem. Op. 133-34; Tr. E 136-37).

Finally, until issuance of the district court's injunction,

school construction projects within the City of Richmond similarly

fostered segregation (Mem. Op. 6-7; 317 F. Supp. 555, 561, 566,

578; see also, 325 F. Supp. 461).

c- Demographic Change: The Influence of School Segregation and Other Discrimination

At the time of Brown v. Board of Education, the student

population of the City of Richmond was 56.5% white. Chesterfield

County's public school population was 79.6% white, and Henrico’s

25

2 0/was 89.6% white (Mem. Op. 230-32; RX 75; PX 122; PX 149).

21/By 1971-72, the county systems were less than 8% black while

the Richmond school division's student population was 70.5%

black. However, these figures represent a change in the

distribution of population within the area; overall, the pro

portion of pupils in the three school divisions has been

approximately two-thirds white and one-third black for at least

several decades (Mem. Op. 231; RX 57, 75-78). The 1971-72

figures include growth in total pupil population from natural

increases and in-migration (Ibid.; Tr. I 33-34). The district

court found that school construction within the City of Richmond

and the Counties of Henrico and Chesterfield after 1954, and

indeed after 1964, has contributed substantially to the present

disproportion between school enrollments within the city and

in the two counties (Mem. Op. 34-39).

In the years after Brown v. Board of Education, the

individual school divisions built schools which were not only

20/ Chesterfield and Henrico Counties together completely

surround the City of Richmond (see map on following page),

Chesterfield to the south and west, Henrico to the west, north and east. Originally, the entire geographical area was part of

the County of Henrico as established in 1634; both the City of

Richmond and Chesterfield County were created therefrom, although

the boundaries of each have subsequently been modified by

annexations (CX 1).

21/ Despite the recent annexation of a portion of Chesterfield County, which removed far more white students from the County

than blacks (Mem. Op. 173; Answer of School Board of Richmond to

Interrogatory No. 5 of Chesterfield Board of Supervisors,

February 17, 1971; see also, Holt v. City of Richmond, 334 F. Supp. 228 (E.D. Va. 1972), appeal pending).

26

-27-

racially identifiable within the context of the individual

divisions, but which also contributed, when combined with the

suburbanization of the two counties surrounding Richmond after

1950, to the present racial identifiability of the school systems.

The opinion below recognizes that there is a considerably

greater affinity between the City of Richmond and the two

counties today than existed at the time of Brown; the area of

urbanization then was much smaller and the counties had not yet

experienced the major spurt of population growth which came as

Richmond established suburbs, conforming to the national pattern

(Mem. Op. 223, 227, 304, 315, 318; RX 71; HX 21, p. 183; HX 24;

CX 21). In this context, the individual school divisions, with

the sanction of the State Department of Education, undertook to

construct identifiably black and white schools. Within the

city, this construction served to intensify black concentration

within the inner city and to accommodate white students located

further and further away from the core. See 324 F. Supp. 456.

As established black neighborhoods in Richmond expanded, always

on the periphery (Mem. Op. 8, 313; RX 18; Tr. I 64-65), there

was a disincentive for blacks to relocate outside the city

limits: the schools constructed in the counties just across

the Richmond line were white schools and black children were

transported, for example, to the all-black Virginia Randolph

High School in the northern part of Henrico County or the all

black Carver High School, located near Chester

28

in chesterfield County, each the only high school for blacks

22/

in the respective counties. The Richmond School Board

allowed its schools to go from white to black through the

exercise of choice and through the assignment of black faculty

as the percentage of black students attending a given facility

increased (RX 75); concurrently, the construction of county

schools just beyond the city’s boundaries attracted white

former Richmond residents and new white arrivals to the area

to locate without the boundaries of the Richmond school division

23/(cf. Tr. I 63, K 49).

The school construction programs of the three divisions,

however, were not isolated occurrences; rather, they combined

with and reinforced other discriminatory practices and policies

of state and local educational authorities, as well as those of

state officials generally; they interacted with long-standing

patterns of private discrimination against blacks. The sum

22/ See Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, Civ. No. 3931

Tw .D. Tenn., Dec. 10, 1971, typewritten opinion at p. 10)

[reprinted as Appendix B hereto].

23/ The two counties conducted a survey of their students in

T971-72 which determined that some 3300 whites then enrolled in

county schools had attended Richmond public schools in the year

immediately prior to their enrollment (Mem. Op. 204; CX 34; Tr.

0 84-85). Of course, it is not white families with children

already enrolled in Richmond schools only who would have been

motivated by the process described in text to locate in the

counties; many could have done so prior to the time their

children were to start school. The statistics demonstrating

an overwhelming change in the distribution of the black and white population in the Richmond-Henrico-Chesterfield area

during a period of time when the overall proportions remained

constant strongly suggest deliberate policy.

29

of these forces was the containment of blacks -- and black

24/pupils particularly — in the City of Richmond.

25/Extensive evidence of both public and private dis

crimination against blacks was introduced below. Racial

designations were carried in advertising for sale and rental

housing, and for employment, in the newspapers of greatest

general circulation in the Richmond area until 1968 (Mem. Op.

320; PX 41; Tr. K 87-89); thereafter, a separate, non-

geographically restricted, general housing column (in which

most property available to blacks had previously appeared) was

26/continued until 1970.

24/ Dr. Karl Taeuber, plaintiffs' expert witness, utilized

indices of dissimilarity for 1970 census tract and block residential data in Richmond-Henrico-Chesterfield to calculate

a "segregation index." He concluded that the area was more

racially segregated in 1970 than it had been in 1960 or 1950,

and that the Richmond area data was consistent with that from the

other metropolitan areas he had earlier studied (Negroes in Cities

(1962)) which indicated that discrimination, rather than economic, preferential or other factors, accounted for the stratification

(Mem. Op. 288-90; PX 131; Tr. I 9-23). The segregation index calculated for school enrollments of the three divisions showed

similar substantial isolation of black students (Mem. Op. 290-

91; PX 132; Tr. I 23-29).

25/ Cf. Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37, 41

74th cTr. 1968); Swann v. charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd, of Educ.,

431 F.2d 138, 140 (4th Cir. 1970).

26/ After notification from the United States Department of Justice that the practice was considered to be in violation of

the Fair Housing Act, the newspapers (which recognized that most

of the listings were located in black areas) agreed to eliminate

the separate category (Mem. Op. 320; PX 41, 42a-42c; Tr. K 77-

89) .

30

In 1969, the Department of Justice advised the Lawyers

Title Company (headquartered in Richmond) to end its practice

of including, in title insurance policies, racial covenants

along with valid encumbrances and restrictions (Mem. Op. 321;

27/

PX 90; Tr. E 7-14). Such covenants appeared with regularity

in deeds to subdivision lots in Richmond, Henrico and Chester

field Counties (Mem. Op. 300, 315, 318, 322; 6/22/70 Tr. 828-

40, see Tr. R 143-44; PX 127; CX 37, 38); the distribution of

black residents in the entire area is far from uniform, but

blacks are rather concentrated in identifiable clusters (Mem.

28/

Op. 314, 317; PX 98; CX 10). With little exception, county

residential areas immediately contiguous to heavily black parts

of Richmond are "occupied primarily by whites" (ibid.). Incidents

suggesting discriminatory treatment of black prospective buyers

of county properties were unrebutted and unchallenged on cross-

examination (Mem. Op. 313-14, 317; Tr. D 201-12; Tr. F 42-49;

see also, PX 92), and the existence of a pattern of discriminatory

practices confirmed by both reports of official agencies (such

27/ Although such restrictions had been declared unenforcible

in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948), the Department ofJustice expressed the view to Lawyers Title that "continued

inclusion [of such covenants] in documents affecting title contributes significantly to the perpetuation of segregation in

housing . . . " (Mem. Op. 319, 321; PX 90; Tr. E 11). See generally the testimony of M. Pope Taylor of Lawyers Title

Company, 6/22/70 Tr. 828-40, admitted herein by stipulation,

Tr. R 143-44.

28/ Dr. Campbell, the Henrico Superintendent, testified that

blacks and whites were "scattered" throughout the county, but

the district court found, on the basis of the evidence, that

"this is not the case" (Mem. Op. 313). See also, Mem. Op. 314.

31

as the Richmond Regional District Planning Commission) (PX 148,

p. 34) and the testimony of its Executive Director (Tr. F 17,

31-32).

The role of federal funding agencies such as FHA and VA

in encouraging the creation of segregated market conditions,

and the continued support of such a market by insuring agencies

(FNMA, FDIC, FHLBB) was established through the testimony of

Martin Sloane, Acting Deputy Staff Director of the United States

Civil Rights Commission (Mem. Op. 293-302; PX 127, 128, 129,

129A, 130, 130A, 137; Tr. K 7-74). Edward Councill, the

Regional Planning Commission Director, termed these practices

a "major factor leading to what are not racially identifiable

residential neighborhoods" in the Richmond area (Tr. F 29).

Currently operated FHA-financed multifamily projects in

the Richmond-Henrico-Chesterfield area are almost entirely

occupied by families of one race, and are located in the center

of established residential pockets of the same race (Mem. Op.

300; PX 129, 129A, 130). There are, however, no such projects

in the counties utilizing the rent supplement program, which

would permit occupancy by families with low incomes, including

many blacks (Mem. Op. 300-01, 316; PX 91; Tr. E 38, K 46,

L 162-63). Nor is there public housing except within the City

of Richmond — whose eight housing projects are principally

occupied by blacks and located in black residential areas

(Mem. Op. 302-03, 316; PX 39; PX 121, p. 242; PX 130; Tr. H 163).

32

These housing projects were built as segregated units in con

junction with local and state school authorities, who sited

educational facilities nearby to accommodate the pupils on a

segregated basis (Mem. Op. 6-7; PX 31). The counties have no

public housing authorities and Richmond's Housing and Redevelop

ment Agency has been unable to locate projects outside black,

low-income neighborhoods (Mem. Op. 302-03; Tr. H 164-67,

29/171-73, 177).

Finally, the entire panoply of other discrimination:

for example, the counties' failure to employ blacks in any

but menial positions (Mem. Op. 316; PX 104, 105, 106, 107a-

107c) and their historic practice of "short-changing" black

schools (Mem. Op. 190-93, 202, 253; PX 125) — in sum, the

"totally segregated society" alleged in plaintiffs' Amended

Complaint (cf. PX 114) — contributed to the failure of blacks

to reside in the counties.

II. The Remedy

The preceding sections summarize evidence concerning

various discriminatory practices of state authorities extending

across political subdivision and school division lines; there

are also a variety of cooperative ventures among separate

29/ The Richmond Authority could construct outside the city

limits with the consent of the counties, but has never requested consent since it was considered a vain act (Tr. H 167).

33

local educational authorities throughout Virginia, sanctioned

and furthered by the provisions of Virginia law. The district

court concluded that a desegregation plan which, similarly,

did not interpose political subdivision boundaries as a barrier

to student movement was not only an appropriate remedy for the

constitutional violations found, but also would, in the opinion

of the witnesses whose testimony was credited by the court,

offer substantial educational advantages for the children in

each division. The court accepted the plan proffered by the

Richmond School Board, designed to accomplish these ends, as

educationally sound, feasible, and adequate to remedy the

pervasive and persistent segregation. Both during the trial and

in its opinion and decree, the district court invited the

submission of alternative plans, but the court's order requires

implementation of the Richmond Board proposal pending such

submission and approval by the court, in order not to further

delay in effectuating the constitutional mandate.

A . School Division Lines

The tuition grant and pupil scholarship programs, and

the maintenance of regional schools for Negroes (see pp. 13-15

supra), are the outstanding examples of the Commonwealth of

Virginia's permissive attitude towards pupil attendance across

school division lines for the purpose of maintaining segregation.

Pursuant to state law, however, other educational programs

34

transcending individual division boundaries have frequently been

established. Historically, Richmond, Henrico and Chesterfield

exchanged students regularly for a variety of reasons, excepting

furtherance of desegregation (Mem. Op. 185, 203-04; PX 101;

30/Tr. H 61-62). The Richmond, Henrico and Chesterfield school

divisions currently operate several regional educational

facilities, including a trades training center, a modern voca

tional school, special education classes, and a mathematics-

science center (Mem. Op. 174-75; RX 35; Tr. D 95-100). One

Richmond school is located entirely, and another in part,

within Henrico County while the City School Board owns an

additional county site on which construction has not yet been

21/commenced (Mem. Op. 203; Tr. L 35).

These pupil exchanges typify the pragmatism expressed in

Virginia practice, which has held boundary lines no impediment

32/to the achievement of educational (and sometimes segregatory)

purposes, but they are also reflective of a more general

commonality of interest among the three divisions. The two

30/ In 1957-58, the Henrico School Board resolved to inquire

into the possibility of arranging for black students in eastern Henrico County to attend a high school within the City of Richmond

(PX 120, p. 101; Tr. H 52-53).

31/ In 1954, the current Richmond Superintendent sought to

acquire a Chesterfield County site for a Richmond white high

school (Mem. Op. 187; PX 117).

32/ The State Board of Education recognized in 1969 that

"political boundary lines . . . do not necessarily conform to

educational needs" (RX 82, p. 20. But see p. 38 infra.

35

counties and Richmond have relied upon each other for various

services such as water, sewage treatment, etc. (Mem. Op. 227-28;

RX 48-51). Relations between the jurisdictions have not always

been harmonious (Mem. Op. 222; Tr. A 104) but repeated planning

studies have consistently urged greater cooperative regional

efforts (Mem. Op. 217-19; HX 25; RX 47, 89; PX 148). This

advice was ignored particularly after the joinder motion was

filed; for example. Chesterfield County withdrew from regional

park and planning bodies (Mem. Op. 229; PX 121, pp. 9, 13, 48).

A great deal of evidence introduced concerned the extent

of Richmond’s "community of interest" with Henrico and Chester

field Counties (e.g., RX 46-51, 54-54A, 58-58A, 59-59A, 61-61A;

HX 7, 9; Tr. A 21-141, K 120-86, L 4-236, M 5-34, 70-93, 100-03);

conflicting opinions were expressed and the evidence required

interpretation rather than compelling a definitive conclusion.

It is clear from the district court's discussion (Mem. Op.

217-29) that some community of interest, of uncertain magnitude,

does exist; while perhaps insufficient to establish that

"community of interest" between Richmond and the counties

necessary under Virginia law to justify annexation and merger

of all governmental services, the evidence in the record clearly

33/

indicates the interdependency of the two counties with Richmond.

33/ But cf., for example, the April 27, 1964 opinion of the

Circuit Court of Henrico County in the 1962 annexation case between

Richmond and Henrico (pp. 8-9): "Although community of interests

is not necessarily as vital a consideration as other factors to be considered . . . this Court nevertheless feels that this factor

should be given consideration. . . . Dependence of the central city

of Richmond and the immediately surrounding county is mutual. [Record citations omitted.] The evidence shows that the commercial and civic interests of the city and county are largely identical."

(HX 7). 36

Virginia law has not restricted these divisions to isolated

operation; in fact, the development of public education has

progressed along opposite lines, steadily enlarging operating

entities (PX 124; RX 82, pp. 1, 20) and encouraging common

endeavors among divisions to improve educational quality (see

n. 5 supra), including the special educational facilities shared

by these divisions described above. Until 1971, school divisions

could be consolidated by the State Board of Education, pursuant

to Va. code Ann. §22-30 (Repl. 1969) and the Virginia Constitution's

requirement that (Art. IX, §129) "the General Assembly shall

establish and maintain an efficient system of public free schools

throughout the state. Such consolidated divisions would operate

under a single Superintendent of Schools; the district court

found, further, that the combination of school divisions

frequently resulted in the use of cooperative techniques of

pupil assignment, such as the operation of joint schools

(Mem. Op. 106). Additionally, Virginia statutes detailed

procedures for reorganization of the constituents of a conso

lidated school division under a single school board, including

general criteria for sharing operating and capital costs among

the political subdivisions (Mem. Op. 101-03; SX 10; Va. Code

Ann. §§22-100.1 et_ seq. (Repl. 1969)). State officials said

they had always interpreted the law to require local assent

(Mem. Op. 105; Tr. G 36) but there were instances in which the

State Board was reluctant to permit separate operation (Mem. Op.

96-99; RX 82, p. 10; Tr. F 134-39, G 36).

37

In 1971, a new Constitution of Virginia took effect; it

directed the General Assembly to provide for "a system of free

public elementary and secondary schools for all children of

school age throughout the Commonwealth" and "an educational

program of high duality." The Constitution also directs the

State Board of Education to adopt standards of quality for

education (Art. VIII, §2) and to divide the Commonwealth into

"school divisions of such geographic area and school age

population as will promote the realization of the prescribed

standards of quality." The General Assembly limited this

power in 1971, by providing that no school division should con

sist of more than one city or county, absent the consent of

local school boards and political bodies (Va. Code Ann. §22-30

34/(Supp. 1971)). Adoption of such an amendment had been

predicted by the Chairman of the Richmond School Board after

the joinder motion herein had been filed (Mem. Op. 102-03;

Tr. N 30); the General Assembly was conscious of the effect

it might have upon this litigation (Mem. Op. 102-03; Tr.

G 102-04).

34/ The new Constitution requires that consolidated divisions

must reorganize under a single school board pursuant to Va. Code

Ann. §§22-100.1 et seq. (Art. VIII, §5(c); Tr. F 142-44).

Pursuant to the amendment enacted by the General Assembly,

the State Board of Education dismantled all previously existing

consolidated school divisions on July 1, 1971 (Mem. Op. 103-04;

PX 122, pp. 392-93; RX 83, p. 47); at the same time, the State

Board established procedures by which now-independent school

divisions could share a single Superintendent of Schools (ibid.;

Tr. F 70). 38

B. The Richmond School Board's Plan

The plan submitted by the Richmond School Board (RX 63-66)

redivides the area consisting of the city and the two counties

35/

into six subdivisions for purposes of administration. Each

subdivision, with the exception of the sixth, would contain a

proportion of black and white students roughly equivalent to

the system-wide ratio (Mem. Op. 233; Tr. A 178). Pupils would

be assigned to schools within each subdivision or immediately

contiguous thereto (ibid.). Generally speaking, students

would be exchanged or reassigned on a school-by-school basis,

without pairing or grade restructuring (Mem. Op. 233; Tr. A 185)

The selection of schools between which students would be

exchanged was made by computer pursuant to instructions to

equalize, for all students insofar as possible, the length of

bus ride (Mem. Op. 235; Tr. A 190-94).

Assignments would be made so that the schools (except

those in Subdivision Six, in the southern part of Chesterfield

County) would range between 20% and 40% black (Mem. Op. 233-34;

36/

RX 63; Tr. A 168, 170-73, 178, 186).

3 5/ Dr. Kelly, the Chesterfield County Superintendent, came to

his position after serving as an area superintendent with the

Fairfax County school system, which has 130,000 students. He

testified that a consolidated school division such as was

proposed, containing about 106,000 students, would have to be

subdivided and decentralized for purposes of administration,

just as Fairfax County was (Tr. E 103-04).

36/ Subdivision Six is the most sparsely settled. The Richmond

Board plan proposed to take the necessary steps to eliminate all

white and all-black schools in that subdivision through pairing

or zoning, but because of the transportation which would be

necessitated, did not propose to eliminate every school disproportionate to the entire system-wide ratio (Mem. Op. 239-40;

Tr. A 174, 189-90, B 24, R 74-76).

- 39 -

The School Board's plan proposed, rather than an island

or satellite zone system for determining which pupils shall

be exchanged with other schools, that a birthday lottery be

established (Mem. Op. A 235-36, 239; Tr. A 199). Dr. Thomas C.

Little, Associate Superintendent of the Richmond School Division

(under whose supervision the plan was prepared) testified,

however, that the plan was flexible enough to permit satellite

zoning in sparsely settled areas within which a birthday lottery

might cause transportation routes of undesirable lengths

37/(Mem. Op. 235-36; Tr. A 195-201, R 74-80). (The pupil

transportation contemplated, unlike that presently in effect

in Richmond, is home-to-school busing rather than school-to-

school busing (Mem. Op. 238; Tr. B 65, 96)).

The maximum number of students who would need to be

transported under the proposed plan is 78,000 — 10,000 more

than are presently bused to school in the three school divisions

38/(Mem. Op. 237; Tr. B 25-27). Richmond, Henrico and