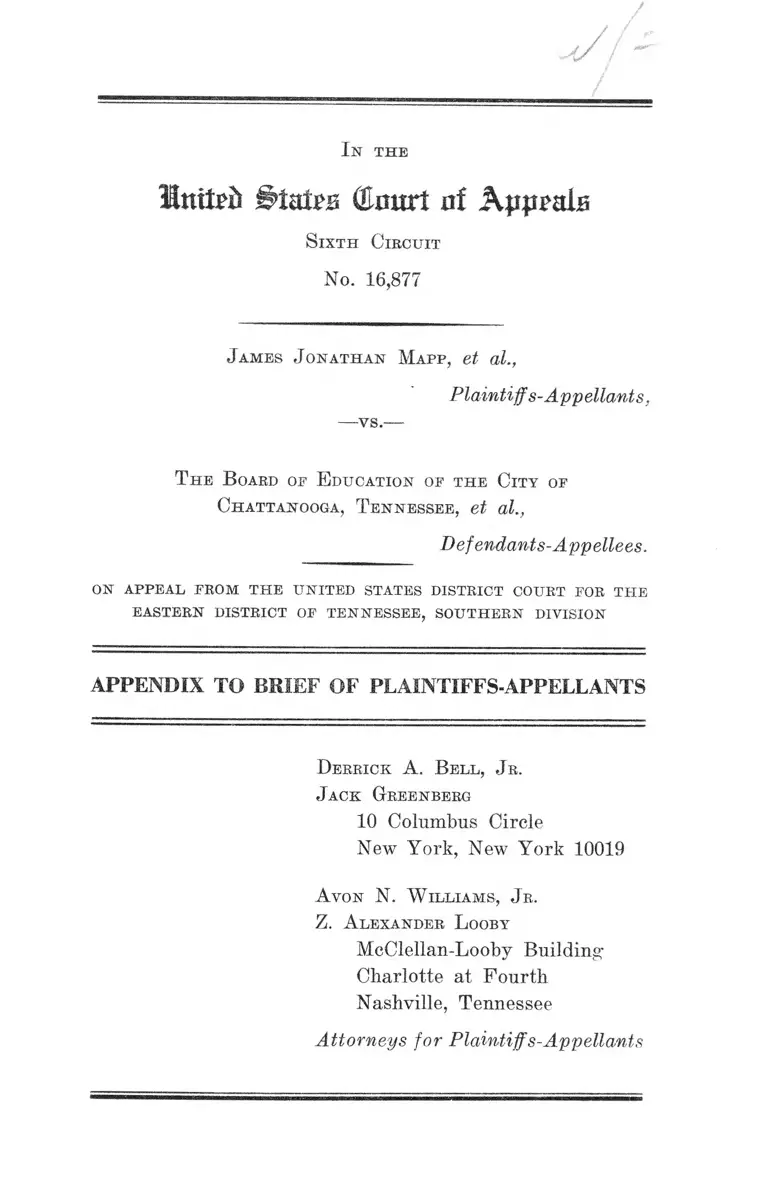

Mapp v. Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga, Tennessee Appendix to Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 11, 1964 - August 11, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mapp v. Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga, Tennessee Appendix to Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1964. a25176fc-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a9e4dbce-1ae0-449e-a7b6-07de84490bc7/mapp-v-board-of-education-of-the-city-of-chattanooga-tennessee-appendix-to-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

United States (Eourt nf Appals

S ix t h C ircu it

No. 16,877

J am es J o n ath an M a pp , et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

—vs.—

T h e B oard of E ducation of th e C it y of

Chattanooga , T ennessee , et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

ON A P PE A L FR O M T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTR IC T COURT FOR T H E

E A STE R N D ISTR IC T OF TE N N E SSE E , S O U T H E R N DIVISION

APPENDIX TO BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

D errick A. B ell , Jr.

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiam s , J r .

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building-

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF APPENDIX

PAGE

Relevant Docket Entries .............................................. la

Progress Report on Desegregation—1964-1965 ........ 6a

Plaintiffs’ Motion for Further Relief ......................... 12a

Excerpts from Transcript of Hearing Held on May 1,

1965 ............................................................................. - 16a

Opinion of Wilson, D.J., Filed August 5, 1965 .......... 156a

Order of Wilson, D.J., Filed August 11, 1965 ........ 164a

Notice of Appeal .......................................................... 166a

T estim o n y :

Plaintiffs’ Witness:

Napolean B. Patton-—

Direct ............................................................... 86a

Cross ................................................................. 87a

Redirect ............ 89a

Recross ............................................................ - 89a

Defendants’ Witness:

Benny Carmichael—

Cross ......................................................... -...... 16a

Recalled—

Direct ...................................................... -....... 92a

Cross ..... 120a

11

E x h ib its :

Offered Printed

Page Page

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits:

1— Newspaper Article ........................... 68a 122a

2— Teacher Employment Record ......... - 75a 125a

3— Transfer Record ........... ...............— 75a 136a

Relevant Docket Entries

8- 2 Complete record on appeal received from U. S.

Court of Appeals, together with copy of opinion

(Miller, Weick & O’Sullivan, Circuit Judges) and

mandates; as to the defendants, affirming judgment

of District Court, and as to plaintiffs, remanding

to the District Court for further proceedings con

sistent with the opinion, filed. Copy of mandate for

defendants mailed to Raymond Witt and for plain

tiffs to Avon Williams by Clerk.

9- 9 Order, W ilso n , D.J. that deft, submit within 45

days a further plan with respect to desegregation

of technical & vocational courses made available

in public schools of Chatta.; (2) deft, submit with

in 45 days full report on progress of desegregation

in accordance with former orders in this cause, to

include school yr. of 1962-63 & beginning Sep. ’63;

(3) pltf. submit within 45 days legal memo, with

respect as to his interpretation of Court of Appeals’

mandate with regard to teacher & principal assign

ment & with regard to issues respecting transfers

& assignments of pupils; (4) each party allowed

15 days to respond to reports above ordered; (5)

case set for further hearing on Fri. Nov. 15 at 9 :30

a.m. filed. Fmtered C.O.Bk. 18, pp. 16/17. Service

of copies by Clerk to all counsel who were present

at today’s conference, and also to Constance Motley.

10-24 Deft. Progress Report and Proposed plan for de

segregation of technical & vocational courses in

Chatta. Public Schools, filed. Service by counsel.

1963

2a

Relevant Docket Entries

11- 26 O rder, W ilson , D.J. that effective with the begin

ning of the second quarter, Dec. 9, 1963, of the

1963-64 school year, students will be admitted for

study in technologies offered in the Chattanooga

Technical Institute without regard to race. Such

admissions shall be conditional, involving the fol

lowing non-racial considerations: All applicants to

be studied as to background training which might

be substituted for the work & training completed

during the current first quarter. Regular entrance

requirements and procedures will be applied. Stu

dents will be admitted to the school for the summer

quarter under same conditions established for sec

ond quarter. With beginning of 1964-65 school year,

admissions shall be made on the basis of the use

of the standard procedures. All other matters con

sidered by the Court at the hearing on Nov. 15,

1963, are taken under advisement and a decision is

reserved, filed. Entered C. 0. Bk. 18, p. 259. Ser

vice of copies by Clerk to all counsel of record.

12- 21 Opinion, Wilson, D . J that all vocational courses

in the public schools shall be offered without re

gard to race effective Sept., 1964, filed. Service by

clerk. Order to enter.

12-31 J udgm en t , W ilson , D.J. defendants’ plan for de

segregation of Chatta. Technical Institute, effective

12/9/63, approved; all other vocational & techni

cal courses in the public schools of City of Chatta.

shall be offered without regard to race effective

beginning of school year in Sept. 1964; desegrega

1963

3a

Relevant Docket Entries

tion of all courses other than vocational & techni

cal courses, & desegregation of all schools, includ

ing Kirkman, except with reference to vocational

& technical courses, shall proceed in accordance

with orders heretofore entered; defts. may adopt

any policy or practice with reference to guidance,

counseling, or placement of students in vocational

courses as may seem proper, provided that no

policy or practice may he based upon race or have

as its primary purpose the delay or prevention of

desegregation in accordance with this order or

orders heretofore entered; allegations of the com

plaint relating to assignment of teachers & princi

pals upon a nonracial basis which were heretofore

stricken from the complaint by order of this Court,

are hereby restored to the complaint in accord

ance with the mandate of the Court of Appeals;

but no previous orders modified at this time, no

further hearings scheduled, and no cause for entry

of further orders; decision of Court made without

prejudice to right of School Board to modify its

policies with respect to teacher & principal assign

ments and without prejudice to the right of plain

tiffs to reassert the issue after a reasonable time;

pltfs.’ objections with respect to assignment &

transfer of pupils are not properly before Court

at this time & not considered. Jurisdiction retained

by the Court during period of transition to fully

desegregated school system in and for City of

Chattanooga. Entered C. 0. Bk. 18, pp. 342/44.

Service of copies by Clerk to all counsel of record.

1963

4a

Relevant Docket Entries

1965

1-11 Progress report filed by defendants, Board of Edu

cation for City of Chattanooga. Service by counsel.

3- 29 Plaintiffs’ motion for immediate further relief in

the desegregation of all phases of the school sys

tem, teachers, transportation, R.O.T.C. etc., with

brief attached. Service by counsel.

4- 30 Plaintiff’s Memorandum of points and authorities

in support of its motion for further relief filed.

Service by counsel.

5- 3 Hearing on motion of plaintiffs filed 3/29/65 for

further relief. Evidence was introduced by parties,

argued, taken under advisement by the court. Each

party is required to submit briefs by May 10 and

any response by parties must be submitted in five

days thereafter. Wilson, D.J. Entered C.O.Bk. 23,

p. 41.

5-7 Report on Projected Enrollment For Junior High

Schools Single Zone with Tables I, II, III and IV

attached as Exhibits filed. Service by counsel. (Mr.

Raymond B. Witt, Jr.)

5-8 Defendants’ Brief opposing plaintiffs’ motion for

further relief filed. Service by counsel.

5-10 Plaintiffs’ Brief in support of its motion for fur

ther relief filed. Service by counsel.

5-14 Defendants’ Reply Brief to Motion for Further

Relief filed. Service by counsel.

5a

Relevant Docket Entries

1965

8-5 Op in io n , W ilson , D.J. that no order of the court

should enter at this time regarding the further de

segregation of the school system, that the defen

dants should be allowed additional time to resolve

this issue; all remaining issues of the plaintiff’s

motion will be denied as not being supported by

the record, filed. Service of copies by Clerk to

Raymond B. Witt for defendants; Avon N. Wil

liams, Jr. & Z. Alexander Looby; Jack Greenberg

& Derrick A. Bell, Jr., and William T. Underwood

for plaintiffs.

8 - 11 Agreed O rder, W ilso n , D.J. according to next-

above opinion entered C.O.Bk. 24, p. 3, and filed.

Service of attested copies by Clerk to all counsel of

record.

9- 7 Notice of Appeal by plaintiffs, James Jonathan

Mapp and Deborah L’Tanya Mapp, b /n /f James

R. Mapp, and James R. Mapp, together with

$250.00 cost bond, filed. Service by counsel.

6a

Progress Report on Desegregation of

Chattanooga Public Schools, 1964-65

(Filed January 11, 1965)

Chattanooga Board of Education

Chattanooga, Tennessee

November 11, 1964

This report is the third presented in compliance with

the United States District Court order that a progress re

port shall be made to the United States District Court

after implementation of each annual step in the plan of

desegregation of the Chattanooga Public Schools.

I ntroduction and R eview

The initial step in the desegregation of the Chattanooga

Public Schools involved grades one through three in 16

selected elementary schools. This was carried out success

fully in the fall of 1962 when 46 Negro students enrolled

in six formerly all-white schools. The second step in the

desegregation of the Chattanooga Public Schools included

students in grades one through four in all elementary

schools. The process continued to function smoothly in

the fall of 1963 when ten formerly all white schools en

rolled 505 Negro students and two formerly all Negro

schools enrolled four white students. A supplementary

report of the 1963 fall enrollment showed five instances

of significant enrollment factors.

T hird S tep of D esegregation

The third step in the plan of desegregation of the Chat

tanooga Public Schools was effected at the beginning of

the 1964-65 school year. All elementary schools, grades

7a

Progress Report on Desegregation of

Chattanooga Public Schools, 1964-65

five and six, were included in the third step. As noted in

the Supplementary Report, 1963-64, no official records

would be received regarding enrollment by race in any

school after the third official day of the 1963-64 school year.

However, based upon a knowledge of the community the

best estimates are that there are now 900 Negro students

enrolled in eleven formerly all-white schools and 55 white

students enrolled in three formerly all-Negro schools.

Special preparations for the implementation of the third

step of desegregation followed those of the past. An

nouncements were made to the public, law enforcement

agencies were alerted and school administrative functions

and registration procedures were followed as in the previ

ous two years. No official records of enrollment by race

have been kept. All students in grades one through six

living in a specific school zone were admitted to the school

in the zone. Permits have been issued based upon ap

proved Board policy which excludes the question of race

entirely.

The following schools, containing grades one through six,

are desegregated: Avondale, G. Russell Brown, William

J. Davenport, East Chattanooga, East Fifth Street, East-

dale, Glenwood, Hemlock, Missionary Ridge, Oak Grove,

Ridgedale, St. Elmo, Louis Sanderson, and Sunnyside.

They are the only schools with pupils of both races in

elementary school zones.

Classes were opened to all students in the Chattanooga

Technical Institute in the winter of the 1963-64 school year,

but no Negroes enrolled. Three are enrolled now. The plan

for the desegregation of the vocational programs in the

secondary schools as approved by the Court was imple-

106a

toward junior high and senior high as a total group.

Q. Why! A. It violates something that I think we have

proven quite well in Chattanooga about the desegregation

of schools. That is, that the introduction of a limited num

ber of children to a successful desegregation—in other

words, you could have accomplished the same thing if this

were their intention by moving into 7 only and 10 only,

and then 8 and 9, 11 and 12, rather than the total group,

—149—

and I think there should be this kind of reasoning taking

that sort of step, you see. So, I would have disagreed

with that approach even if I were intending to achieve

the same end or objective in the same period of time.

Q. Not just because you don’t like it! A. No—

Mr. Williams: I object to his leading this witness,

your Honor.

Q. Is it educationally sound, in your opinion! A. I don’t

think it is as educationally sound.

Q. What difference do numbers make in a classroom?

What differences does it make whether you have two Negro

children or— A. It tends to push the teacher beyond the

point that she can adjust to a need and problem that she

has.

Q. Why! How? A. Because it is requiring more of

her than she can give. She has got to build gradually

toward what she can give and what she can adjust to, if

she is going to teach adequately. This is true in every

other consideration we make of a teacher. Everything. We

don’t group children homogeneously when race is not in

volved and load them on teachers all at one time. I don’t

know why we can reason that we can do the same thing

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

107a

when it comes to race without giving the same considera

tions.

—150—

Q. Do teachers prefer to teach white students? A. Yes,

they do.

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

Mr. Williams: This is objected to, if your Honor

please, whether teachers prefer to teach white stu

dents is entirely irrelevant to any consideration in

this case.

Mr. Witt: The whole purpose for us being in this

courtroom today has to do with the quality of the

education this community will get in the years ahead.

What we are talking about, we are not playing a

numbers game in the sense of so many Negroes here

and so many white people there, we’re trying to do

this in an intelligent way so that we have the first

experience—

Mr. Williams: I hate to take up the time to make

a responding speech, your Honor, but I would say

that we are not here for the purpose of having a

dissertation on quality of education and whether

teachers prefer to teach white students. The Negro

children in this city are entitled to have their con

stitutional rights, the enjoyment of their constitu

tional rights now, rather than have them in a

deferred position, and that, your Honor, has no rele

vance, whether she prefers to teach white children.

The Court: Well, state a question.

Q. Dr. Carmichael, based upon your experience, what

happens to the children in a classroom that are progressing

108a

—151—

at the slowest rate? A. They are tended to be overlooked.

Q. What do you mean, overlooked?

Mr. Williams: I object to this, if your Honor

please. It is highly incompetent and irrelevant. If

this man were testifying as an expert on the basis

of some study that he had individually made and

published, that’s one thing. He is now just asking

general questions about what happens with regard

to some hypothetical situation—

Mr. Witt: Your Honor, this study is pursuant to

an act of the United States Congress, authorizing

the expenditure of federal funds for this particular

kind of study to meet this particular kind of prob

lem. It is the first one in the United States approved.

I would like to go into in step by step. This goes

to—

The Court: Gentlemen, it is much easier, after

these hearings are over, to sort out what is relevant

and what is not relevant. It is rather difficult as we

go along to anticipate where a considerable amount

of the testimony is relevant—

Mr. Williams: It is true that this is a matter of

determination by the Court, and the Court is learned

in the law. On the other hand, the Court is a human

being. I remember the Court in Nashville refused

to allow himself to hear incompetent evidence. Who

knows the effect of the accumulation—

—152—

The Court: If I exclude the evidence and they

desire to put it in the record, they have the right to

do so. I ’ve found on these non-jury hearings that

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

109a

the better part of wisdom is to be rather broad in

allowing evidence to be put in, and then when you

go to consider the evidence just disregard that por

tion of it not proper to consider. I ’ve overruled the

immediate objection, let’s move along.

Q. I hand you what purports to be a proposal for school

board grants for programs on educational problems inci

dent to school desegregation, submitted to the United

States Commissioner of Education under the provisions of

Title 4, Section 405, Public Law 88, 352 Civil Rights Act

of 1964. Dr. Carmichael, was this proposal prepared under

your direction! A. Yes, it was.

Q. Was it submitted to the Chattanooga board of educa

tion! A. Yes, it was.

Q. Was it approved by the Chattanooga board of educa

tion? A. Yes.

Q. Was it submitted to the Department of Health, Ed

ucation and Welfare of the United States government?

A. Yes.

Q. Was it approved by the Department of Health, Ed

ucation and Welfare? A. Yes.

—153—

Q. Is it in operation? A. Yes, it is.

Q. Have you received the funds? A. Partially.

Q. Partially? A. Yes.

Q. Do you recall the section of the Civil Rights Act

under which this was authorized? A. Section 405 of Title

4, entitled Grants to Boards of Education.

Q. Do you recall the purpose for which these grants

were made? A. The purpose is to provide grants to

boards of education to conduct in-service education pro

grams on problems occasioned by desegregation.

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

110a

Q. Now, what remains to be done under this particular

study? A. The evaluation, summary evaluation, and con

clusions drawn with regard to changes that have been pro

duced in teachers, on this first phase.

Q. On the first phase? A. Yes, sir.

Q. This will take place when? A. Following the end of

the May 8 meeting, the actual preparation of the report

will begin.

— 154—

Q. Who will prepare the report? A. It is the primary

responsibility of Mr. William Smith, the director of the

project.

Q. Is he an employee of the Chattanooga board of educa

tion? A. Yes, he is.

Q. What will be done with this report once it is pre

pared? A. It will be used to extend this kind of training

and preparation of teachers on into the junior high level,

and to accomplish the kinds of things in Avondale that

are implied that should be accomplished, and some of that

has already begun. We have already identified three

specific kinds of things that must be done to carry on an

adequate program in Avondale, and I ’d like to mention

those, if I may. These are just conclusions drawn at this

time—

Q. These are just temporary conclusions? A. These

are temporary conclusions which our staff has begun.

Q. Are these your conclusions? A. My conclusions and

those of the division of instruction of the Chattanooga

school administrative staff. These are going to be the

three kinds of things we develop in order to cope with

the problem or to offer an adequate education program.

I should like to mention them if you’ll let me.

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

I l ia

— 155—

Q. Go ahead. A. One is the development of a cur

riculum adequate to meet the needs of those children,

particularly in pinning down the specific kinds of learning

skills that we must pursue in order to provide an effective

learning program for these youngsters. That gets quite

detailed and involved.

Q. Can you illustrate that before you give your other

two points? A. The best illustration that I would use

would be the need to introduce a telephonic program for

ear training for youngsters before they are introduced into

first grade work, to use a specific in the area of curriculum.

Q. Can you think of a specific in terms of the seventh

grade? A. No.

Q. What do you mean by telephonic? A. It’s a device

by which certain sounds are prerecorded in relation to

letters and certain pictures, and children are just—it’s

flashed on a screen and it is played from a record, and

children hear and identify the particular object or symbol

that goes with it. This comes directly out of the program

of the specialized Amadone school of Washington D.C.

Q. Will this be limited to Negro schools? A. It won’t

after we get it perfected and introduced. In fact, our

major objective is to introduce it and perfect it in such

— 156—

a way that we can then disseminate it to all schools, those

which may remain predominately Negro and those which

are white, and so on.

Q. Would this relate to Operation Headstart? x\. Yes,

it would.

Q. Will this relate to senior high? A. Eventually there'

must be an extension of it.

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

112a

Q. What is the second point? A. The establishment of

an adequate classroom environment in the Avondale School

per se. This is described in terms of the organization of

material in the room, even going to the point of being

sure we put lines on the chalk boards by which children

write; that certain specified materials are in every room,

such as maps and globes, as opposed to just a sundry

listing of materials that may be in a room now; and then

the area dealing with teacher attitude of types of ques

tions that are asked, how they are asked, and so on. And

the consultants give very specific guides on these kinds

of things, in order to teach children effectively. May I

go on to the third area?

Q. Yes. A. The third area is the development of an

adequate school-parent program. This is identified in

Detroit, it is identified in Pittsburgh, it’s identified in every

area where they have undertaken this kind of thing. To

—157—

develop a type of program with parents so that you have

their interest and their cooperation and their assistance

in the total program. These are kinds of things that give

rise to and are the basis for all of your major projects now

in this area of dealing with the culturally disadvantaged,

the Headstart programs, and so on. They come from the

proof that these kinds of things are necessary if we are

going to help children as they ought to be helped.

Q. How many teachers were involved in this first step?

A. 75.

Q. How many of these were junior high? A. 25. See,

you had 25 at Avondale, 25 elementary outside of Avon

dale, and 25 junior high, the make-up of the group.

Q. Were these Negro teachers and white teachers? A.

Negro teachers and white teachers. More whites than

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

113a

Negroes, more white teachers involved than white teachers.

Q. Now, what is the second step in this project? A. It

depends on which phase you are talking about?

Q. What is the second phase? A. The second phase is

a similar program conducted during the summer, in which

the consultants returned to our school system and worked

with a new group of teachers all day for 10 days. The

teachers involved observed in Avondale and analyzed

records of children and methods and procedures used

—158—

and so on.

Q. Will this idea be continued or discontinued at the

end of the second phase? A. It will be continued and

expanded. It will be continued upward first into junior

high and particularly into Hardy Junior High, where

these children will attend junior high school, and there is

a fair commitment already on the part of the principal

and this staff that it would like to pick up the kind of

thing that Avondale is doing and be sure that it continues

a similar program into the junior high school. Plans are

being formulated to do this.

Q. You selected two Negro teachers to go to Avondale?

A. Yes.

Q. Would you describe the process by which you selected

these teachers?

Mr. Williams: May it please the Court, I object,

on the ground that this is entirely irrelevant to any—

The Court: Gentlemen, could we not move on to

the junior high and high school programs? Would

that not be the area that we are concerned with here ?

Mr. Witt: Your Honor, it is fairly clear the dif

ferences between counsel for plaintiff and myself,

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

114a

this school board and the plaintiff, it has to do with

objectives. I ’m trying to identify for your Honor

the kinds of considerations that are necessary in the

opinion of this defendant and this board to make the

- 1 5 9 -

kinds of decisions with regard to people. Adminis

trative decisions that result in the kind of an educa

tion where the constitutional rights will have mean

ing. I can illustrate with these two people, that

they just didn’t pick two Negro teachers who had

graduated from college and had the necessary

courses in education. I ’m trying to get across for

your information and guidance the kinds of prob

lems that this superintendent must deal with if

he is to direct this effort at, not the number gained,

but the question of education.

The Court: It seems to me the relevant issues

are the problems confronting the school board in

the junior highs and senior highs. If you think you

can make it relevant I ’ll allow you to proceed and

we can determine whether it becomes relevant. As

I understand now, you are relating the problems that

have been confronted in the Avondale School, which

school has now been desegregated?

Mr. Witt: As the best evidence, in face the only

evidence, this superintendent and this school system

has to guide them in planning for approaching un

known territory, which is the 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th,

11th and 12th grades.

The Court: Well, so far there hasn’t been any

thing in the record, has there, to show the problem

of Avondale is the problem of a junior high or the

problem of a high school?

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

8a

Progress Report on Desegregation of

Chattanooga Public Schools, 1964-65

mented, but as of this date there have been no Negro

enrollees.

Z one C hanges

According to official Board records there have been 12

zone changes in the Chattanooga Public Schools since the

last report to the Court. All elementary school zones are

shown in Appendix A. Many factors contribute to and

make necessary the changing of school zones. However,

in no instance were there any considerations given to race

factors. The enrollment of all schools during any school

year will change almost daily and certainly from month to

month. Some school enrollments will show only slight

changes while others will vary greatly.

The following zone changes have been made since the

last report to the Court. Also noted are explanations and

primary reasons which dictated the changes:

Ft. Cheatham-Ridgedale

The Ft. Cheatham Elementary School was closed in No

vember of 1963. The school property along with adjacent

property was acquired for freeway right-of-way. The Ft.

Cheatham Elementary School zone was added to the Ridge-

dale Elementary School zone.

Cedar Hill-East Lake Elementary

A portion of the East Lake Elementary zone was made

optional for the 1964-65 school year and will become a

permanent part of the Cedar Hill zone in the fall of 1965.

This was done in order to relieve East Lake and to im

prove the program at Cedar Hill. There are no Negro

children in the zone of either school.

115a

Mr. Witt: Perhaps I can make this connection.

—160—

Q. What problems would there be in desegregating an

entire junior high school, 7th, 8th, 9th grade! A. It’s a

problem of amplifying each separate problem that you

have when the number is smaller. By separate problems

I mean such thing as learning level adjustment, boy-girl

relationships, determination of how to handle extra-cur

ricular activities, and this sort of thing.

Q. I f you have a junior high school with five Negroes

entering the 7th grade, is there any different between this

situation and the situation where you have 200 Negroes

entering the 7th grade! A. Tremendously.

Q. Detail me, please? A. The teachers will not feel that

they have a potential—potentially problem spot, to put it

in terms of explosiveness or just learning problems or

boy-girl, white-Negro relationship adjustment and so on.

In the case of the five, they will not have this feeling.

In the case of the 200, it will be on the tips of their

tongues and their thoughts at all times, and this is the

difference in the thing we are dealing with.

Q. How do you know this! A. They talk with you

about it, they stop you and talk with you.

—161—

Q. Who is they? A. The teachers who are exposed to

this. The teachers from Avondale, immediately when this

set in, would stand and talk with you by the hour about

this incident and this incident and I ’m afraid this is going

to happen, and so on. I ’m not saying these are things to

be afraid of or worried about, and I ’m not afraid of them

and worried about them. I am just saying that these are

kinds of things that are on the minds of teachers and you

have to help them get them off.

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—-Recalled—Direct

116a

Q. Are you saying there is a difference between Avon

dale and Glenwood? A. There is no difference between

Avondale at this time last year and Glenwood at this

time this year. The concerns of teachers at Glenwood

are at the stage this year that Avondale’s were last year.

And those are just sheer fear, frustration, and concern

about the problem that they are working with.

Q. Does this result from numbers? A. Yes, in large

measure it does, because it has reached the point that they

cannot continue to teach as diverse group, or to carry as

many who are having special learning problems, out of

30 children, without some kind of help.

Q. Dr. Carmichael, when you identify teachers such as

this, why don’t you just discharge them? A. First, they

have tenure. Secondly, these are genuine good teachers,

their concern is wholly with teaching children. I ’ve never

—162—

had a concern in that regard. I respect them greatly for

the concern they have. If they weren’t feeling this way

about it, the problem would be much greater.

Q. Can you identify any other problem in connection

with numbers? We’re asking this Court to justify the

plan that we proposed before and has been approved,

on the basis that what we have learned says that we should

continue at this pace. This is the reas'on I ask you these

questions. Is Sunnyside different from—in numbers, is

Sunnyside different from Glenwood? A. Yes.

Q. How? A. The number is much smaller and the num

ber per classroom with a given problem is less.

Q. If the number of pupils of another race in a classroom

is small, this means that the problem in that classroom

is small? A. If that race carries a preponderance of

children with problems, yes. It’s not the matter that it is

a different race, it’s a matter that more children have

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

117a

problems of that group with which the teacher must be

concerned.

Q. Does the number of the Negro pupils in a classroom

increase or decrease the frustrations of the teacher? A.

If they have individual problems which our groups have

had, it increases the frustrations of the individual teacher.

—163—

Q. What about the situation at Louis Sanderson, where

you have two white pupils in a formerly all-Negro school?

Any problem? A. Not that I know of. The problem is not

even one of minority grouping in a classroom so far as I

know. It’s not a case of the children being afraid of one

another or being hostile to one another. We’ve not had any

problem with this, never had. It’s learning and behavior

problems of individual children that I ’m talking about, that

teachers are concerned with.

Q. Do you think you know things to do now that will

affect the quality of education in junior high school when

we desegregate? A. We know a few things to do. We’re

going to take more of these children into junior high schools

with a specific delineation of what their problems are and

what their learning levels are.

Q. Do you have an answer to all the problems? A. No.

I don’t even know all the problems.

Q. You don’t know all the problems? A. No.

Q. Does anybody? A. Not that I know of. And from

the experience we had in trying to get help with this project,

I don’t think many people do.

—164—

Q. Where did you go for help with this project? A. I

went to Detroit, I went to the University of Florida, I went

to Vanderbilt, I went to Peabody, I went to the University

of North Carolina. I tried about 10 people.

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—-Recalled,—Direct

118a

Q. What were you. looking for? A. I was looking for

a person that knew how to deal with this problem. How

you really get in the classroom and teach a group of Negro

children, adjust your methods and so on, so that they will

fit. You will not find a person that I know of who is really

comfortable in dealing with this question, to help teachers

in a classroom.

Q. Do you have the manpower to meet these problems?

A . No.

Q. Will the accelerated desegregation that the plaintiffs

are asking for in their motion before this Court, will this

increase your problems? A. Yes.

Q. How much? A. I don’t know how to estimate it. I

would put it this way, to the point that I would not be

inclined to try to work it out, in terms of really accommodat

ing. I’cl merely keep the lid on, so to speak.

Q. You mean the problem would be so big you—

Mr. Williams: I object to that—

Mr. Witt: Excuse me, I withdraw it.

—165—

The Court: Sustained.

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

A. It’s the same thing I was referring to a minute ago.

You’ll do what you can and you’ll judge what you do by

what kinds of problems are you are dealing with. This is the

only answer that I can really give to it. If 90 per cent of

the problems are just keeping order, we’ll spend our time

on that. If 90 per cent of the problems are in dealing with

learning difficulties, we’ll spend our time on that.

Q. Can you describe briefly, based upon your experience,

what you think will be the result, viewed as the school

119a

superintendent in Chattanooga, if the plaintiff’s request

with regard to accelerated desegregation is approved?

What would you expect? A. You mean in terms of num

bers, instructional problems?

Q. The impact on the school system? Before you answer

the question, I remind you, as school superintendent, that

you have not recommended complete desegregation.

Mr. Williams: I object—

The Court: I ’ll allow him to answer the first ques

tion, if the second was a question.

A. I will answer it in terms of the impact will be one of

going beyond the point, in some instances, to where teachers

could make the kinds of adjustments to the problem that

I want them to make. Consequently, they will adapt meth

ods and procedures to adjust—contain the situation, but

—1 6 6 -

will not be inclined to move toward thoroughly under

standing it and overcoming it, with their own adaptations.

This is the best possible way that I could put it. Let me

use this as an example, if you will permit it. I had a junior

high school this year that is not even a junior high school

that we talked about before, who in foreseeing desegrega

tion said should we not stop this year, perhaps, our 9tli

grade outings, because desegregation is coming and

shouldn’t we stop them. This was not the belief or feeling

of the principal. I reasoned with them that if I were you

I would wait, when desegregation occurs in the 7tli grade

your school will make a far better adjustment to it than

you’d think. I would hope that you would not start using

this sort of method to escape doing what ought to be done

for children. I cite this to say I think you can continue

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Direct

120a

the kind of extra-curricular activities that are good for

boys and girls, if you will be sensible about it, and if you

give children time to adjust to it and parents time to ad

just to it. On the other hand, I think to go at it otherwise,

you may destroy some awfully important kinds of oppor

tunities for boys and girls. I just don’t think that we are

wise in moving this direction. I cannot say that, yes, you

are going to take the 9th grade to Lake Winnepasauka

and swim. I mean, I can’t force them to do it and I don’t

want to. If people don’t want to swim, they don’t swim,

as far as I ’m concerned. But I ’d wish they would continue

—167—

to go to Lake Winnepasauka and swim, because I think

boys and girls need to do this. There is not a thing in

the world wrong with doing it with both races. In fact,

I don’t think boys and girls are going to conduct them

selves well until they can do whatever boys and girls are

supposed to do, in the presence of both races. But this

takes time and adjustment and development for children

to do it, as I see it operating in schools.

Mr. W itt: No further questions.

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams:

Q. Dr. Carmichael, regardless of race, you have ques

tions involving cultural patterns, problems, educational

problems involving cultural patterns? A. Yes, you do.

Q. This is just by way of comment, but are you familiar

with Fisk University? A. Yes, I am.

Q. Are you aware that Fisk has a race relations depart

ment and has had an institute there for years and years,

and as a matter of fact this summer has been conducting

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Cross

121a

an institute where teachers are involved in desegregation?

A. Yes.

Q. You did not, when you said you were at a loss and

went to all these white universities up north and all over

the country, it didn’t occur to you to contact someone at

— 168—

Fisk? A. Yes, sir, I know your people at Fisk. They

don’t know how to do what I ’m talking about.

Q. I was just curious. A. Yes, sir.

* • # # *

Benny Carmichael—for Defendants—Recalled—Cross

122a

PRESS RELEASE

The Mountain City Teachers Association is greatly con

cerned with many of the existing conditions and practices

with which our teachers are faced at this time. The failure

of the School Board to integrate the teachers is not com-

patable with their often expressed belief in quality educa

tion. This continued practice of segregation can only re

sult in low morale and a feeling of insecurity of a large

segment of teachers. Dissatisfied and insecure instructors

do not beget quality education; it is the opposite.

The continued hiring of white teachers to teach the extra

classes brought about by the transfer of Negro pupils into

the so-called white schools creates a surplus of teachers

in the here-to-fore Negro school. The decrease in the stu

dent body of certain schools may well lead to the closing

of the schools and the abolition of some teaching positions.

Already more than thirty white teachers have been hired

because of the 900 or more Negro pupils tied to the so-

called white schools. This failure to integrate has already

cost the taxpayers money for surplus teachers in the sys

tem. There is no reason why the integration of the facul

ties of all the schools can not be done smoothly and har

moniously.

The children who are carrying the brunt of this great

social revolution have a right to have some of their own

teachers teach them. This certainly would alleviate some

of the pressure and minimize some of the frustrations

experienced by those children. This is certainly a deter

rent to quality education. This condition could be remedied

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1

123a

very easily and simply. Place at least one Negro and one

white teacher in every racial school; balance the person

nel in certain schools to meet the psychological needs and

racial proportion of the student body.

The integration of the staff should be an essential phase

of the desegregation program of our schools, instead,

every conceivable reason that can be found is used to delay

the inevitable; workshops to teach teachers to teach in

desegregated schools; Negro counselors (glorified disci

plinarians) assigned to schools with a large Negro pupil

population.

— 2 —

Local #428 favors total integration of teachers and stu

dents. We feel that it is impossible for teachers to teach

democracy without practicing it in the classroom as well

as in everyday living. Psychologically, children understand

democracy when they experience it in action rather than

through abstraction.

To integrate teachers in Chattanooga would not be setting

a precedence in the South. Teachers are integrated in some

cities in Kentucky, Oak Ridge and Cooksville, Tennessee;

why not Chattanooga?

Our All American City has successfully integrated City

Hall, downtown department stores, theatres, restaurants

and other public and private facilities without ill-effect.

Why has the school system not seen fit to keep pace with

other facets of the community?

Since Negro and white teachers are working together in

inservice training programs and other programs for the

betterment of Chattanooga’s youth, we should have de

veloped a relationship which would lend itself to the sue-

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1

124a

cessful integration of the faculties of Chattanooga Public

Schools.

It is our belief that the Chattanooga Public Schools can not

provide quality education for all of its pupils until the

schools are thoroughly desegrated. We further believe

that the maximum benefit of all the schools to all pupils

will only come with complete integration.

We call upon all citizens, including teachers, and the Board

of Education, to help take democracy off paper and put

it into immediate practice.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1

9a

Progress Report on Desegregation of

Chattanooga Public Schools, 1964-65

Avondale-Garber-Glenwood

The enrollment at Avondale School exceeded to a con

siderable degree all expectations and projections. In order

to prevent Avondale’s capacity from becoming untenable

certain portions of the Avondale zone adjacent to Garber

and Glenwood schools were zoned to those schools. Both

white and Negro children were affected.

Ridgedale-Oak Grove

Displacements of students because of the freeway con

struction caused the enrollment of Ridgedale School to

be more than building capacity. In order to prevent the

setting up of classes on the stage and in the hall at Ridge

dale, a small area of the Ridgedale zone was transferred

to the Oak Grove zone. All the transfers were Negro

students.

Piney Woods-Trotter

Both Piney Woods and Trotter schools are located in or

adjacent to an industrial area in the city. A number of

students who lived closer to Piney Woods were required

to attend Trotter and this necessitated their walking

through a heavily trafficked area. In order to provide for

their safety and to lessen the distance they would have

to travel, the zone was changed to allow them to go to

Piney Woods Scool. Only Negro children reside in each

school zone.

Moccasin Bend Area

The city limits of Chattanooga were recently changed by

ordinance to include an area known as the Moccasin Bend

125a

C hattanooga P ublic S chools

1161 West Fortieth Street

Box 2013

Chattanooga 9, Tennessee

April 30, 1965

Reports and Records on Teacher Employment,

Assignments, and Discharges for 1960-61 through

1964-65 in Chattanooga Public Schools as Required

by Civil Subpoena, Civil Action File No. 3564,

to Dr. Bennie Carmichael Dated April 28, 1965

These reports and records are submitted in compliance

with the Civil Subpoena cited above. For purposes of

clarification, the word “hired” used in the third line of

the second paragraph of the letter requesting that the

subpoena be issued is interpreted to mean “new teachers

employed” ; inasmuch as the last sentence of the letter

states that “In teacher information, show whether hired

as replacements or otherwise.” The report is based upon

this interpretation rather than the meaning which would

include all teachers employed by the Chattanooga Board

of Education each year whether new employees or tenure

employees. The word “respective” used in the same third

line of the second paragraph is interpreted to mean “the

schools of the Chattanooga School System” ; whereas,

“respective” used in two other places in the same sentence

is interpreted to mean the individual schools to which

teachers were assigned or from which they were discharged.

The report, beginning on the next page, shows new

employees by school years, 1960-61 through 1964-65.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

126a

Teachers for each year are shown separately by race and

according to school to which they were assigned. Numbers

of teachers discharged are shown by school, likewise, and

the new assignments are recorded in terms of replace

ments for resignations, retirements, or transfers, and for

new positions created as a result of increased enrollments

or other requirements for a new position.

This report is based upon the official minutes of all

school board meetings in which teachers were approved by

the Chattanooga Board of Education from 1960-61 to the

present date, school directories for 1959-60 and 1960-61,

and annual reports to the Board of Education showing

personnel assigned to schools as of the tenth day of school

for the 1961-62, 1962-63, 1963-64, and 1964-65 school years,

verifying the employment of teachers by individual schools.

These records are in the courtroom for substantiation of

the summary report.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

Respectfully submitted,

/s/ B e n ja m in E. C aem ich ael

Benjamin E. Carmichael

Superintendent

BEC:rl

127a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

School Year 1960-61

White Teachers

School

Num ber Num ber . , T,

N ew Teachers A ssigned P er

Teachers Dis- Replace- N ew

E m ployed charged m ent P ositions

P osition

Gain

Change

Loss

Brainerd High 5 5 26

Chattanooga High 8 8 8

Kirkman 4 3 1 1

Brainerd Junior 3 3

East Lake Junior 4 4 5

East Side Junior 5 5

Hardy Junior 5 5 2

Elbert L o n g Junior 1 i 2

Lookout Junior 4 4

North Chatta. Junior 7 5 2 2

P a rk Place Junior 10

Avondale Elementary 1 1 4

Henry L. Barger Elem. 2 2

G. Eussell Brown Elem. 1

Cedar Hill Elem. 1

Clifton Hills Elem. 2 2 2

East Chattanooga Elem. 4 3 1 1

East Lake Elem. 1 1 1

Eastdale Elementary 2 2 1

Mary Ann Garber Elem. 2

Hemlock Elementary 1

Highland Park Elem. 3 3 1

Elbert Long Elem. 1

Missionary Eidge Elem. 1

Oak Grove Elementary 1 1 1

Eidgedale Elementary 5 3 2 2

St. Elmo Elementary 1 1 1

Sunnyside Elementary 1 1 1

Woodmore Elementary 2 2 1

Central Elementary 8

Lookout Elementary 1

Jefferson St. Elem. 8

Clara Carpenter Elem. 14

Net Eesult 71 53 18 44 66

Loss — 22

128a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

School Year 1960-61

Negro Teachers

Number

New

Num ber

Teachers A ssigned F or P osition Change

Teachers Dis- Replace- New

School Em ployed charged ment P ositions Gain Loss

Howard High 13 7 6 6

Howard Junior 6 6 7

Orchard Knob Junior 5 5 7

East Fifth St. Junior 2 1 1 1

Park Place Junior 1 1 12

Second District Junior 3 2 1 1

Charles A. Bell Elem. 2 2 22

Chattanooga Ave. Elem. 3

W. J. Davenport Elem. 4 4 9

Calvin Donaldson Elem. 1 1 4

East Fifth St. Elem. 6 6 3

James A. Henry Elem. 2

Howard Elementary 1 1 3

Orchard Knob Elem. 11

Louie Sanderson Elem. 2 2 2

Joseph E. Smith Elem. 2 2

Spears Avenue Elem. 2 2

Frank H. Trotter Elem. 6 6

West Main St. Elem. 1 1 10

Clara Carpenter Elem. 4 4 14

Ft. Cheatham Elementary 1 1

Net Result 62 32 30 79 38

Gain + 41

School Year 1961-62

W hite Teachers

Brainerd High 11 11 1

Chattanooga High 2 2 7

Kirkman 5 5 10

Brainerd Junior 1 1 1

Dalewood Junior 2 2 15

East Lake Junior 3 3 1

East Side Junior 3 3 1

129a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

School Tear 1961-62

White Teachers

School

Num ber N um ber , . , T,

at m u A ssigned F or New Teachers ----------------------

Teachers D is- Replace- N ew

E m ployed charged m eat P ositions

P osition Change

Gain Loss

Hardy Junior 5 4 1 1

Elbert Long Junior 1

Lookout Junior 1 1

North Chatta. Junior 5 4 1 1

Avondale Elementary 7

Henry L. Barger Elem. 2 1 1 1

G. Russell Brown Elem. 3 2 1 1

Cedar Hill Elem. 1 1 8

Clifton Hills Elem. 1 1 1

East Chatta. Elem. 2 2 2

East Lake Elem. 3 3 4

Eastdale Elem. 2 2

Mary A n n Garber Elem. 1 1 2

Glenwood Elem. 1 1

Hemlock Elem. 2 2

Highland Park Elem. 1 1 1

Missionary Ridge Elem. 1 1 1

Normal Park Elem. 3 3

Ridgedale Elem. 4 4 4

St. Elmo Elem. 1

Sunnyside Elem. 1

Woodmore Elementary 3 3

Lookout Elementary 5

Net Result 68 57 11 27 51

Loss — 24

N egro Teachers

Howard High 8 7 1 1

Howard Junior 6 4 2 2

Orchard Knob Junior 3 3 5

Park Place Junior 2 1 1 1

Charles A. Bell Elem. 3 2 1 1

Chattanooga Ave. Elem. 3

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

School Year 1961-62

Negro Teachers

School

Number

New

Teachers

Em ployed

Num ber

Teachers

D is

charged

A ssigned F or

Replace- New

ment Positions

P osition Change

Gain Loss

W. J. Davenport Elem. 3 3 7

Calvin Donaldson Elem. 3 3

East Fifth St. Elem. 2 2

James A. Henry Elem. 3 1 2 2

Howard Elem. 6 6 11

Orchard Knob Elem. 8 8 18

Louie Sanderson Elem. 1 1 1

Frank H. Trotter 5 5 2

West Main St. Elem. 11

Clara Carpenter Elem. 1 1 3

Net Result 54 1 32 22 43 24

Gain + 19

School Year 1962-63

W hite Teachers

Brainerd High 16 5 11 11

Chattanooga High 2 2 3

Kirkman 6 2 4 4

Brainerd Junior 1 1 1

Dalewood Junior 9 3 6 6

East Lake Junior 2 2 1

East Side Junior 1 1 2

Hardy Junior 4

Elbert Long Junior 1

Lookout Junior 6 6 2

North Chatta. Junior 2 2 3

Henry L. Barger Elem. 2 2

Avondale Elementary 3

G. Russell Brown Elem. 4 4 2

Cedar Hill Elem. 1 1

Clifton Hills Elem. 5 5 2

East Chatta. Elem. 3 3

East Lake Elem. 4 4 1

131a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

School Year 1962-63

White Teachers

School

Num ber Num ber A ssigned F or

N ew Teachers ------- 2----- --------

Teachers Dis- Replace- New

Em ployed charged m eat P ositions

P osition Change

Gain Loss

Eastdale Elem. 1

Mary Ann Garber Elem. 2 2 1

Glenwood Elementary 1 1 1

Hemlock Elementary 1 1

Highland Park Elementary 1 1 1

Elbert Long Elem. 2 1 1 1

Missionary Ridge Elem. 1

Normal Park Elem. 2 2 1

Oak Grove Elem. 1 1

Ridgedale Elem. 8 8 1

St. Elmo Elementary 1 1

Sunnyside Elem. 1 1

Woodmore Elem. 1 1

Net Result 89 61 24 24 26

Loss — 2

N egro Teachers

Howard High 12 4 8 8

Alton Park Junior 5 5 33

Howard Junior 4 4 6

Orchard Knob Junior 4 4 5

East Fifth Street Jr. 4

Second District Jr. 19

Charles A. Bell Elem. 2 2

Chattanooga Ave. Elem. 2 2 1

W. J. Davenport Elem. 2 2 1

Calvin Donaldson Elem. 3 3

James A. Henry Elem. 2 2 4

Howard Elementary 2 2 11

Orchard Knob Elem. 4 2 2 2

Louie Sanderson Elementary 2

Joseph E. Smith Elem. 2 2 1

Spears Avenue Elem. 2 1 1 1

132a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

School Year 1962-63

Negro Teachers

School

Number Number Assigned For

New Teachers ----- -----------

Teachers Dis- Eeplace- New

Employed charged ment Positions

Position Change

Gain Loss

Frank H. Trotter Elem. 3 3

Ft. Cheatham Elem. 1 1 1

Clara Carpenter Elem. i

Net Result 50 28 22 61 39

Gain + 22

School Year 1963-64

W h ite Teachers

Brainerd High 10 6 4 4

Chattanooga High 7 4 3 3

Kirkman 3 2 1 1

Brainerd Junior 1

Dalewood Junior 4 4 1

East Lake Junior 5 5 1

East Side Junior 5 5 2

Hardy Junior 2 2 2

Elbert Long Junior 2 2 1

Lookout Junior 5 5 1

North Chatta. Jr. 1 1 2

Avondale Elementary 7 2 5 5

Henry L. Barger Elem. 4 4 1

G. Russell Brown Elem. 1 1 2

Cedar Hill Elem. 1

Clifton Hills Elem. 3 2 1 1

East Chatta. Elem. 1 1 2

East Lake Elem. 5 4 1 1

Eastdale Elem. 2 1 1 1

Mary Ann Garber Elem. 1 1 1

Hemlock Elem. 1

Highland Park Elem. 3 3 2

Elbert Long Elem. 3 3

Missionary Ridge 1 1

Normal Park Elem. 1 1

133a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

School Year 1963-64

White Teachers

School

Number Number Assigned For

New T e a c h e r s ---------------- -

Teachers Dis- Replace- New

Employed charged ment Positions

Position

Gain

Change

Loss

Oak Grove Elem. 2 1 .1 1

Ridgedale Elem. 8 7 1 1

St. Elmo Elem. 2 2

Sunnyside Elem. 3 3

Woodmore Elem. 1

N et Result 91 71 20 22 20

Gain + 2

N egro Teachers

Howard High 3 3 22

Riverside High 4 4 40

Alton Park Junior 5 5 1

Howard Junior 7 7

Orchard Knob Junior 1 1 1

Riverside Junior 7 7 34

East Fifth St. Junior 15

Park Place Junior 13

Charles A. Bell Elem. 2 2 i

Chattanooga Ave. Elem. i

W. J. Davenport Elem. 1

Calvin Donaldson Elem. 1 1 1

East Fifth St. Elem. 5

James A. Henry Elem.

Howard Elem. 1 1

Orchard Knob Elem. 3 3 1

Joseph E. Smith Elem. 1 1 i

Frank H. Trotter Elem. 1

Ft. Cheatham Elem. 2

Clara Carpenter Elem. 18

N et Result 35 24 11 81 79

Gain + 2

134a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

School Year 1964-65

White Teachers

Num ber

New

Num ber

Teachers

A ssigned Eor P osition Change

Teachers Dis- Replace- New

Gain LossSchool E m ployed charged ment P ositions

Brainerd High 6 4 2 2

Chattanooga High 10 6 4 4

Kirkman 6 3 3 3

Brainerd Jnnior 1 1

Dalewood Junior 4 4

East Lake Junior 5 5

East Side Junior 5 4 1 1

Hardy Junior 4 4 3

Elbert Long Junior 4 3 1 1

Lookout Junior 2 2

North Chatta. Junior 1 1

6Avondale Elementary 5 5

Henry L. Barger Elem. 4 3 1 1

G. Bussell Brown Elem. 2 2

Cedar Hill Elem. 2 2

Clifton Hills Elem. 4 4

East Chatta. Elem. 3 3

East Lake Elem. 4 4

Mary Ann Garber Elem. 4 3 1 1

Eastdale Elem. 1

Highland Park Elem. 1 1 1

Elbert Long Elem. 5 3 2 2

Missionary Ridge Elem. 1 1

Normal Park 1 1

Ridgedale Elem. 6 3 3 3

St. Elmo Elem. 2 2

1Sunnyside Elem. 3 2 1

Net Result 95 70 25 26 5

Gain + 21

10a

Progress Report on Desegregation of

Chattanooga Public Schools, 1964-65

Area. This area has been designated as an optional school

zone for grades 1-12.

C oncluding Observations

In addition to the orderly process of the court ordered

desegregation of the Chattanooga Public Schools there

have been additional instances related to desegregation

which are related and worthy of note. The Central Office

Staff of the Chattanooga Public School System has been

desegregated since the fall of 1962. Currently there are

four Negro personnel holding supervisory and admin

istrative positions in the Division of Instruction.

At the opening of the 1964-65 school year, two Negro

teachers were assigned to a school with an all-white fac

ulty. These assignments were made in connection with a

special project which was begun at one school this yeai.

This school, which has kept a special record of the prob

lems growing out of cultural differences, has committed

itself to a concentrated study devoted to determining edu

cationally sound methods for dealing with these problems.

The school in which the study will be conducted on a co

operative basis is attended by both white and Negro stu

dents.

The Manpower Development Training Program spon

sored by the United States Government and operated by

the Chattanooga Public Schools admits students regardless

of race. Classes conducted under the provisions of the

Manpower Development Training Act are open to all

students.

In the Day School Program at the Chattanooga Tech

nical Institute there are currently enrolled three Negroes.

135a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2

School Year 1964-65

Negro Teachers

School

Number Number Assigned For

New Teachers ----- 5---------—

Teachers Dis- Replace- New

Employed charged ment Positions

Position

Gain

Change

Loss

Howard Senior High 8 2 6 6

Riverside Senior High 3 3 7

Alton Park Junior 4 3 1 1

Howard Junior 3 33 1

Orchard Knob Junior 4 2 2 2

Riverside Junior 4 3 1 1

Avondale Elementary 2

Charles A. Bell Elem. 1

Chattanooga Ave. Elem. 4

W. J. Davenport Elem. 1

Calvin Donaldson Elem. 1 1

East Fifth St. Elem. 7

James A. Henry Elem. 1

Howard Elementary 2

Orchard Knob Elem. 2 2 3

Piney Woods Elem. 2 2 13

Joseph E. Smith Elem. 2

Frank H. Trotter Elem. 3

Ft. Cheatham Elem. 3

Yet Result 31 16 15 32 28

Gain + 4

136a

C hattanooga P ublic S chools

1161 West Fortieth Street

Box 2013

Chattanooga, Tennessee 37409

April 30, 1965

Summary Report and Record of Transfers of Students

Out of Zone in Chattanooga Public Schools for the

Years 1961-62 through 1964-65

In compliance with the Civil Subpoena, Civil Action File

No. 3564, to Dr. Bennie Carmichael, dated April 28, 1965,

the following reports and records are submitted. Transfers

between school zones (permission to attend school out of

zone) are permitted in Chattanooga Public Schools under

the policies of the Chattanooga Board of Education adopted

August 12, 1964, and shown on the attached sheet.

For the year 1961-62, a summary report has been pre

pared of the number of students transferred according to

the policy of the Board of Education regulating the trans

fers. The summary report is included with the file of the

individual student assignments to schools out of zone.

In the report of 1962-63 to the District Court on progress

in desegregation, a listing was made of all children in

grades 1-3 permitted to transfer between schools desegre

gated at the beginning of the 1962-63 school year. In addi

tion, a summary report of all other students permitted to

transfer, accompanied by the individual records of the

students, is submitted to substantiate the report.

In 1963-64, the report to the District Court listed all

transfers between schools which were desegregated for

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3

137a

grades 1-4. A copy of this report is included. An additional

report accompanied by the records substantiating the re

port is prepared on transfers between all other schools.

The report for 1964-65 did not carry the listing of stu

dents permitted to transfer between zones. A summary

report has been prepared on all transfers for the 1964-65

school year, and all individual student records are submit

ted to substantiate the report.

The above reports cover grades 1-9. Since there are no

school zones established for senior high schools, grades

10-12, there is no question of transfer between these schools.

Respectfully submitted,

B e n ja m in E. Carm ich ael

Benjamin E. Carmichael

Superintendent

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3

BECrrl

138a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3

(See Opposite)^"

R E Q U E S T F O R C H I L D T O E N R O L L O U T O F Z O N E

C h a t t a n o o g a P u b l i c S c h o o l s

T H I S P A R T ~ O F R E Q U E S T T O BE C ^ P L E T E D ~ B Y P A R E N T O R G U A R D I A N

N a m e o f C h i l d _________ _

H o m e A d d r e s s ____________________________

S c h o o l Z o n e d T o ________________________________________ ______________

S c h o o l Y o u W i s h C h i l d T o A t t e n d __________ ____ _________

S c h o o l A t t e n d e d L a s t Y e a r _______ ________________________ ___________

G r a d e L a s t Y e a r ______________________ G r a d e T h i s Y e a r

F u l l N a m e of: F a t h e r ______ _

M o t h e r

G u a r d i a n

D a t e

T H I S P A R T OF R E Q U E S T T O BE C O M P L E T E D B Y P R I N C I P A L

S P E C I F Y B O A R D P O L I C Y U N D E R W H I C H A P P R O V A L T O A T T E N D S C H O O L IS R E C O M M E N D E D

2. a. d. .. .. g. i. (1)

b. e. h. (2)

c. f. j.

C O M M E N T S S U P P O R T I N G R E C O M M E N D A T I O N OF A P P R O V A L U N D E R P O L I C Y i. (1) or (2)

R E C O M M E N D A T I O N O N R E Q U E S T : Y e s ________ No,

P r i n c i p a l ______________________________________ S c h o o l _____________________________ D a t e _

THIS' P A R T O F R E Q U E S T T O BE C O M P L E T E D BY S U P E R I N T E N D E N T

A P P R O V E D : Y e s :_______ N o

S u p e r i n t e n d e n t ________________________________ D a t e __________________

A d m i t t i n g P u p i l s W h o

R e s i d i n g W i t h i n the C i t yi t y L i m i t s o f C h a t t a n o o g a

SO-? T23U03H

m . , , , .aLnodoE s ild iif BgooimddarfO _ ,.T o the e x t e n t of r e a s o n a b l e b u i l d i n g c a p a c i t y , p u p i l s w h o s e p a r e n t s or g u a r d i a n s

r e s i d e w i t h i n the c i t y l i m i t s of C h a t t a n o o g a a r e a d m i t t e d as f o l l o w s :

— .1 , 1 P u p i 't g w h o s e #,p a r e n it 8 ',o r .

s c h o o l c o n c e r n e d . S u c h p u p i l s , of c o u r s e , a r e a d m i t t e d as s o o n as t h e i r » „

, , » 1 1 1 QlIUJ I O QshHW.

3 3 3 xJb h A oim H

t e m p o r a r i l y a d m i t t e d b y p e r m i t f r o m the S u p e r i n t e n d e n t u p o n w r i t ^ i ^ r e q u e s t .

b y the parents-;...T h e s e ’ w r i t t e n ’ r e q u e s t s 'tmist" i n c l u d e “t h e -parent's * n a m e s ,

a d d r e s s , p u p i l ' s n a m e , a l s o the n a m e , a d d r e s s a n d re|-Atipi^sJii|); o f t h e p e o p l e

iwtthr>"w h oiirl:he,-efa±ld~ T e 8 i 'd e 'S" ‘fi-f'.p u pi t -ii v M - wrtflffe" parents'* h o m e g i v e t h e

r e a s o n t h a t p a r e n t s a r e r e q u e s t i n g t h i s s p e c i a l permissipp.)^ a n ^ ^hje n ^ g Rforfo?.

the""srhooi~th'e'''ptrpil"will“'atrte;nd“i f " * p e r m ± t “i s ‘‘gT'anted”.

„ , , . , r e a Y a id !. o b s r D . . . . . ie $ ¥ d e a d s h s ’iO. .a ■ e h i l d r e n ' " o r " a ,d o p t e d c h i l d r e n , or othex-'mitror^ - rrring^— i n t h e h o m e or s c h o o l

p e r s o n n e l . i s d b s l :1o sm&Vi I l u l

b. C h i l d r e n p l a c e d in e s t a b l i s h e d n u r s e r i e s f o r b e f o r e - a n d a f t e r - s c h o o l c a r e

tl^mrf^dTe~Bxdrocrir“±tr"wh'ircdr’ztTire-"'tlrarTiuirffery is* l o c a t e d , ( E x a m p l e :

P r o R e B o n a , M i s s M a g , etc.) o e i b i ^ u O

c. C h i l d r e n p l a c e d in p r i v a t e or c h u r c h n u r s e r i e s for b e f o r e - a n d a f t e r - s c h o o l

c a r e m a y a t t e n d the s c h o o l i n w h i c h z o n e the nu r s e r y - i s - l o c a t e d . ( S u i t

a b i l i t y of s u c h n u r s e r y is p r o p e r l y d e t e r m i n e d . )

d . C h i l d r e n f r o m h o m e s b r o k e n b y 'iaparatlEotr"or ■̂ (i v o r c e r ~ {in iere q u e s t i o n s

rthe,child,, t h q parent,, i n w h o s e home; the, c h i l d

s t a t e m e n t f r o m the c o u r t r e g a r d i n g c u s t o d i a n s h i p . )

a r i s e as to c u s t o d y of

r e s i d e s m u s t o b t a i n a s

■ s' >, b

e. C h i l d r e n of w o r k i n g m o t h e r s w h o s e c h i l d is p l a c e d i n the h o m e of a

r e l a t i v e for b e f o r e - a n d a f t e r - s c h o o l c a re. — — Sj

f . H a n d i c a p p e d , cji^ldrep whpj.pjay .^^vp avWa»-ifc

t h e m for a s s i g n m e n t to a s c h o o l o u t s i d e t h e i r zone.

~^.™‘X h i^retr '‘frtW"hTm8B8''^ii’̂ 1:cft"'^HrltraF''l1intreffs~tnr-iiorffp4i:a±izatrttjrrr)f”'thr'-- ..~ ~

m o t h e r or g u a r d i a n p r o h i b i t s a d e q u a t e c h i l d - c a r e .

h. S i t u a t i o n s r e q u i r i n g w o r k i n g m o t h e r s to t ake c h i l d r e n to p l a c e s of

— .-~-lj-a^ ^ 'g ^ g --^ s- ’'l}^fgrE^ - atsd""'fffrer-s’ctro'ol'~'C'are"r~'" ...........

^ —pQpix^ih"Tire”'eOTe^'are^sslgtt^l3y""t*e“ StrperttrtendeTit“ Trf-Schools-.....

for r e a s o n s of a d j u s t m e n t a f t e r t h o r o u g h i n v e s t i g a t i o n a n d s t u d y b y

— _--------OTd"W'^h^"TEcmBreTrd^rton,-'rrf“-the v is iting -TegdTer-S-ervt cgr — -

...... (Z)....T O r r o r s r a r ' i i m o i r i n r m - T r o i R m t t ^ ^ ......— .......

p e r m i t , h a s always, p e p p g f t t ^ ^48tffA(ftfe»SJ8 5 6 ^ lue e n r o l l m e n t ln a

-----f S h o o l b y "'Choice w h e n a z o n e c h a n g e w a s m a d e t h a t w o u l d m o v e a

____ s t u d ffgQ to a d i f f e r e n t s c h o o l. Iootfae ................. laaionliS

j. C h i l d r e n w h o s e p a r e n t s h a v e p u r c h a s e d or a r e b u i l d i n g a h o m e in a g i v e n

— — School..zdhe."tSuch children .arp admipted ta the^ew: sphool pnly-aftep^ the '-'T ;-;;-

-------paT§hW'pta<5S"6tt“flie a*letter from architect and/or"contractdr 'estatriishihg-—™*

the f a c t t h a t the h o m e w i l l be. r e a d y for o c c u p a n c y w i t h i n a b r i e f a n d

specified period.)”

’ "5 bO ■♦/rsba**.. ‘ijciag-

139a

140a

C hattanooga P u blic S chools

1161 West Fortieth Street

Box 2013

Chattanooga, Tennessee 37409

April 29, 1965

S u m m ary of N umbers of T ransfers G ranted S tudents

in C hattanooga P ublic S chools, G rades 1-9

for 1961-62 by B oard P olicy R easons

Board Policy Item Number of Students

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3

2 a. 56

b. 38

c. 0

d. 11

e. 119

f. 93

g- 4

h. 9

i. 126

j- 0

Total 456

141a

C hattanooga P ublic S chools

1161 West Fortieth Street

Box 2013

Chattanooga, Tennessee 37409

April 29, 1965

S u m m ary of N umbers of T ransfers G ranted S tudents

in C hattanooga P ublic S chools, Grades 1-9

for 1962-63 by B oard P olicy R easons

Board Policy Item Number of Students

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3

2 a. 28

b. 4

e. 4

d. 0

e. 24

f. 7

g- 2

h. 1

i. 129

j- 3

Total 202

142a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3

Appendix A

Page 1

Student Transfers Granted in 1962-63 For

Pupils in Grades 1-3 Involving Schools

Selected For Desegregation

Transfers Under Policy 2.a,

Student School

No. Name Race

1. Charles Goode, Jr. N

2. Esther L. White N

3. Yenetia B. Jarrett N

4. Michael S. Heard N

5. James R. Henry W

6. John A. Henry W

7. David H. Haynes w

8. Angela B. Park w

9. Francis X. Park w

10. Michael Davis w

11. Patrieia Davis w

12. Becky Davis w

13. Susan Davis w

14. Melinda Walker N

15. Francia R. Holloway N

16. Vickie C. White N

17. Norman E. Williams W

18. Renata L. Tyler N

19. Balm M. Tyler

Transfers Under Policy 2.b.

N

20. Giovanna B. Heard N

21. James A. Horn W

22. Kathy E. Horn W

23. Deborah Payne

Transfers Under Policy 2.c.

N

24. Michael Dozier N

25. Marsha Ann Grimes N

26. Beverly Ann Wood N

Zoned to : Transferred to :

Orchard Knob East Fifth

Orchard Knob East Fifth

Orchard Knob James A. Henry

Orchard Knob Charles A. Bell

Glenwood Sunnyside

Glenwood Sunnyside

Glenwood Bidgedale

Clara Carpenter Glenwood

Clara Carpenter Glenwood

Glenwood G. Russell Brown

Glenwood G. Russell Brown

Glenwood G. Bussell Brown

Glenwood G. Russell Brown

East Fifth Howard

C. Donaldson Orchard Knob

Clara Carpenter East Fifth

Henry L. Barger East Chattanooga

F. H. Trotter Orchard Knob

F. H. Trotter Orchard Knob

Sunnyside East Fifth

W oodmore Avondale

W oodmore Avondale

Glenwood East Fifth

Page

Glenwood Orchard Knob

Clara Carpenter Orchard Knob

Clara Carpenter Orchard Knob

11a

Progress Report on Desegregation of

Chattanooga Public Schools, 1964-65

In the Adult Evening Program at the Clara Carpenter

Center for Continuing Education there are five Negroes

enrolled in commercial, high school review, and industrial

electricity courses.

The Practical Nurse Training Program has enrolled

eighteen Negroes and the instructor is a Negro. At the

Driver Education Center one of the two instructors is a

Negro. Students from the five high schools of the city,

without regard to race, come to the Center for driver

training.

Sound administrative planning, alert law enforcement

agencies, and cooperative community efforts have been

primarily responsible for the success of the efforts made

and plans carried out in all areas and facets of desegrega

tion in the Chattanooga Public Schools. Many problems

which were not evident to all concerned, at least in the

beginning, are being recognized and plans are being formu

lated to solve them. With the continued combined efforts

of the total community it is anticipated that desegregation

in the Chattanooga Public Schools will continue to be not

only an orderly process but, and more important, a process

that will solve many related problems thus making the

educational opportunities not only available to all students

but available under better and improved conditions.

(A ppendix O m itted )

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3

Transfers Under Policy 2.d.

Student

Appendix A

School

No. Name Race Zoned to : Transferred to :

None

Transfers Under Policy 2,e.

27. James Daugherty W Sunnyside Barger

28. Joel K. Williams W Sunnyside Avondale

29. Doyle K. Williams W Sunnyside Avondale

30. Georgeanna Johnson N Orchard Knob Howard

31. Bessie B. Rice N Orchard Knob Howard

32. Daniel J. Windham, Jr. N Orchard Knob Howard

33. Phyllis D. Baker N Orchard Knob Joseph E. Smith

34. Sarah D. Fletcher N Orchard Knob Joseph E. Smith

35. Erna Rogers W Normal Park G. Russell Brown

36. Iris Stubbs N Glenwood Orchard Knob

37. Karen Stubbs N Glenwood Orchard Knob

39. Leroy Clark N Glenwood Clara Carpenter

40. Phyllis Ann Lamb N Glenwood Orchard Knob

41. Shirley L. Lamb N Glenwood Orchard Knob

42. Willie Armour N Clara Carpenter James A. Henry

43. Freda Armour N Clara Carpenter James A. Henry

44. Patricia Armour N Clara Carpenter James A. Henry

45. Johnnie Armour N Clara Carpenter James A. Henry

46. James Scruggs N Clara Carpenter James A. Henry

47. Debra Scruggs N Clara Carpenter

Page 3

James A. Henry

48. Elizabeth D. Shoup W Henry L. Barger East Lake Elementary

49. Jaequaline Patton N Orchard Knob Chattanooga Avenue

50. Debra E. Ellis N F. H. Trotter Charles A. Bell

Transfers Under Policy 2.f.

51. Claude Troxell W St. Elmo G. Russell Brown

52. Vernon Cooper W Normal Park G. Russell Brown

53. Geraldine Durham w Normal Park G. Russell Brown

54. Larry Durham w Normal Park G. Russell Brown

55. Virginia R. Greene w Sunnyside Missionary Ridge

144a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3

Transfers Under Policy 2.f.