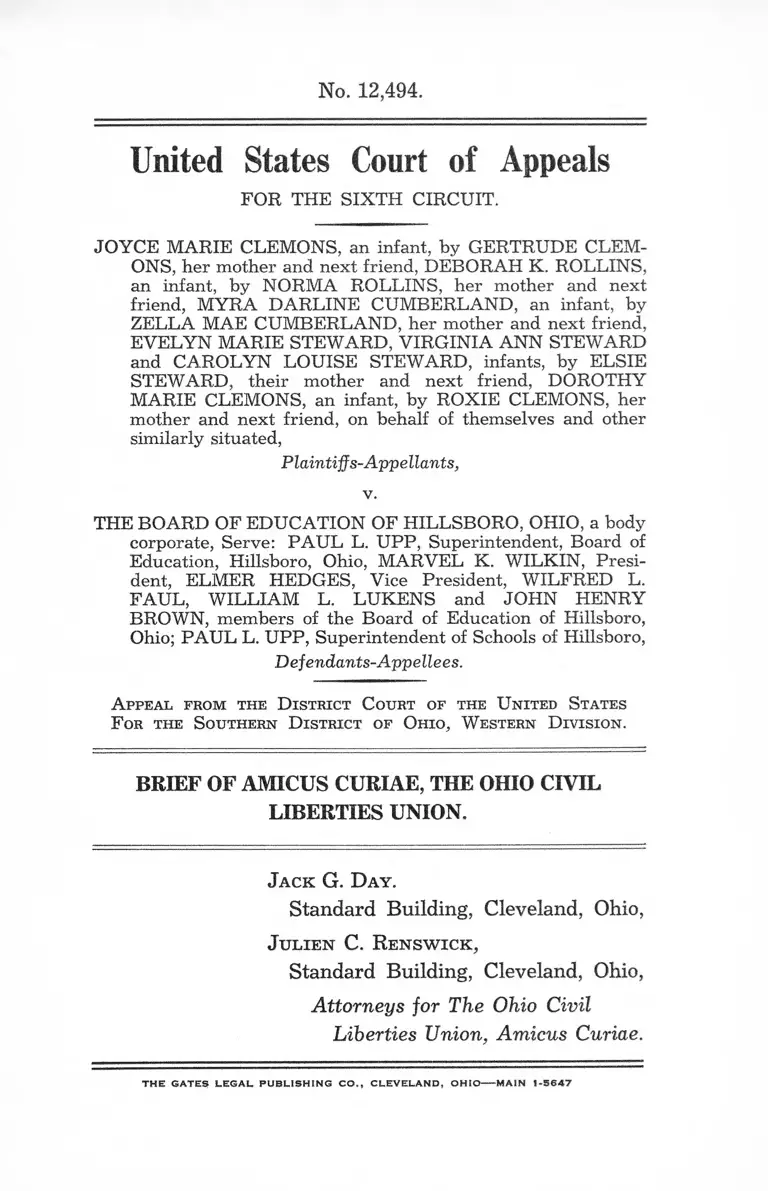

Clemons v. Hillsboro, OH Board of Education Brief of Amicus Curiae, The Ohio Civil Liberties Union

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clemons v. Hillsboro, OH Board of Education Brief of Amicus Curiae, The Ohio Civil Liberties Union, 1955. c136e9ce-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aa260c2f-bd18-4bf8-be1b-5ac3b64efbb4/clemons-v-hillsboro-oh-board-of-education-brief-of-amicus-curiae-the-ohio-civil-liberties-union. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

No. 12,494.

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT.

JOYCE MARIE CLEMONS, an infant, by GERTRUDE CLEM

ONS, her mother and next friend, DEBORAH K. ROLLINS,

an infant, by NORMA ROLLINS, her mother and next

friend, MYRA DARLINE CUMBERLAND, an infant, by

ZELLA MAE CUMBERLAND, her mother and next friend,

EVELYN MARIE STEWARD, VIRGINIA ANN STEWARD

and CAROLYN LOUISE STEWARD, infants, by ELSIE

STEWARD, their mother and next friend, DOROTHY

MARIE CLEMONS, an infant, by ROXIE CLEMONS, her

mother and next friend, on behalf of themselves and other

similarly situated,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

v.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF HILLSBORO, OHIO, a body

corporate, Serve: PAUL L. UPP, Superintendent, Board of

Education, Hillsboro, Ohio, MARVEL K. WILKIN, Presi

dent, ELMER HEDGES, Vice President, WILFRED L.

FAUL, WILLIAM L. LUKENS and JOHN HENRY

BROWN, members of the Board of Education of Hillsboro,

Ohio; PAUL L. UPP, Superintendent of Schools of Hillsboro,

Defendants-Appellees.

A ppe al fr o m the D ist r ic t C ourt of the U nited S tates

F or the S ou th ern D ist r ic t of O h io , W estern D iv is io n .

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE, THE OHIO CIVIL

LIBERTIES UNION.

Ja c k G. D a y .

Standard Building, Cleveland, Ohio,

J u lie n C. R e n s w ic k ,

Standard Building, Cleveland, Ohio,

Attorneys for The Ohio Civil

Liberties Union, Amicus Curiae.

T H E G A T E S L E G A L P U B L IS H IN G C O ., C L E V E L A N D , OHI< •MAIN 1 - 5 6 4 7

STATEMENT OF QUESTION INVOLVED.

Amicus Curiae accepts the Statement of Question In

volved as set forth by the appellants.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

Statement of Question Involved_______________Prefixed

Counter-Statement of Facts______________________ 1

Argument _____________________ 5

1. The court below abused its discretion in refus

ing to grant a permanent injunction enjoining

appellees from enforcing a policy of racial seg

regation in the elementary schools and from

requiring infant appellants to withdraw from

Washington and Webster Schools and enroll in

Lincoln School, solely because of their race

and co lo r____._____________________________ 5

Conclusion_____________________ 10

Relief ___________________ 10

Appendix: Statutes______________________________ 11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.

Cases.

Board of Education vs. The State, 45 O. S. 555______

Board of Education of School District of City of Day-

ton et al. vs. The State of Ohio ex rel. Reese, 114

O. S. 1 8 8 ________ ___________________________

Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483

Brown et al. vs. Board of Education of Topeka et al.,

349 U. S. 294 ______________________________

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. vs. Sawyer, 343 U. S.

579 ________ _________________________________

Statutes.

Revised Statutes of Ohio 1886, Chapter 9, Section

4008 _______________________________.________ 8,11

84 Laws of Ohio 1887, page 3 4 ________ .___________ 8,11

8

8

6

6

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT.

No. 12,494.

JOYCE MARIE CLEMONS, an infant, by GERTRUDE CLEM

ONS, her mother and next friend, DEBORAH K. ROLLINS,

an infant, by NORMA ROLLINS, her mother and next

friend, MYRA DARLINE CUMBERLAND, an infant, by

ZELLA MAE CUMBERLAND, her mother and next friend,

EVELYN MARIE STEWARD, VIRGINIA ANN STEWARD

and CAROLYN LOUISE STEWARD, infants, by ELSIE

STEWARD, their mother and next friend, DOROTHY

MARIE CLEMONS, an infant, by ROXIE CLEMONS, her

mother and next friend, on behalf of themselves and other

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF HILLSBORO, OHIO, a body

corporate, Serve: PAUL L. UPP, Superintendent, Board of

Education, Hillsboro, Ohio, MARVEL K. WILKIN, Presi

dent, ELMER HEDGES, Vice President, WILFRED L.

FAUL, WILLIAM L. LUKENS and JOHN HENRY

BROWN, members of the Board of Education of Hillsboro,

Ohio; PAUL L. UPP, Superintendent of Schools of Hillsboro,

Defendants-Appellees.

A ppeal from the D istr ic t C ourt of the U nited S tates

F or the S outhern D istr ic t of O h io , W estern D iv is io n .

AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS.

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF FACTS.

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of Ohio, Western

Division, denying a permanent injunction which would

have enjoined appellees from enforcing a policy of segre

gation of the public schools of Hillsboro, Ohio, and from

compelling infant appellants to withdraw from the Web

2

ster and Washington Schools, solely because of their race

and color, and from requiring infant appellants to attend

Lincoln Elementary School or any other school in Hills

boro which is attended exclusively by Negro children.

By stipulation between the parties the following facts

are not in dispute (65a-69a).

The infant plaintiffs are all Negro children residing in

the City of Hillsboro, Ohio, eligible to enroll in and attend

the elementary schools of that city which are under the

control of the defendants. Those elementary schools are

three in number, named Washington, Webster and Lincoln.

Prior to 1954 the Lincoln School had long been maintained

as an elementary school for the exclusive attendance of

Negro children, whereas for at least fifteen years prior to

September 7, 1954 no Negro pupils had attended either

Webster or Washington Schools. On September 7, 1954,

the beginning of the school year, 32 Negro pupils were reg

istered by the Webster School, and 8 Negro pupils were

registered in the Washington School. These 40 pupils were

assigned seats in regular classrooms in the schools where

they had registered on September 8, 1954.

The following was the assignment of the 7 infant

plaintiffs in the case at bar: Infant plaintiff Joyce Marie

Clemons was assigned a seat in a sixth grade classroom in

Webster School. Infant plaintiff Deborah K. Rollins was

assigned a seat in a first grade classroom in Webster

School. Infant plaintiff Myra Darline Cumberland was as

signed a seat in a first grade classroom in the Webster

School. Infant plaintiff Evelyn Marie Steward was as

signed a seat in a fifth grade classroom in the Washington

School. Infant plaintiff Virginia Ann Steward was assigned

a seat in a fourth grade classroom in Washington School.

Infant plaintiff Carolyn Louise Steward was assigned a

3

seat in a second grade classroom in Washington School.

Infant plaintiff Dorothy Marie Clemons was assigned a

seat in a second grade classroom in the Washington

School.

It was further stipulated that for several years prior

to September 7, 1954 the Washington and Webster Schools

were overcrowded, and accordingly to provide for expan

sion the Webster School was to be rebuilt in its entirety

and the Washington School to have an addition. How

ever, it appears that as between September 1953 and

1954 there was an elementary school enrollment drop

from 928 to 899 pupils in the Hillsboro district. On Sep

tember 8, 1954 the average number of pupils per room at

Washington was 35.4, at Webster 38, but at Lincoln there

was a total of 17 Negro pupils in a school with a total of 4

classrooms, only 2 of which were in use as regular class

rooms. Of the total enrollment in the school district, 593

white children were transported daily from outside the city

limits in order to attend elementary school in Hillsboro.

Of that number 177 were assigned to Webster and 166 to

Washington. None'of these pupils were assigned to the

Lincoln School and no Negro children attending elemen

tary school in Hillsboro were transported into the city.

It is stipulated, in addition, that there were two full

time Negro teachers assigned in the Lincoln School teach

ing all six elementary grades in two rooms, whereas there

were twelve elementary classrooms in the Washington

School and twelve in the Webster School, one teacher be

ing assigned to each room teaching one grade in each room.

The segregation of pupils in grades seven and eight

was discontinued by the Board of Education in Hillsboro

in 1951 and the one high school in the city is attended by

both Negro and white students.

4

On August 9, 1954 the Board of Education adopted a

resolution which reads as follows: “That the Hillsboro

City Board of Education go on record supporting the inte

gration program, for children of Lincoln School, of Supt.

Upp on completion of Washington and Webster School

buildings” (sic).

Though not stipulated it appears that the construc

tion of those school buildings will be completed about the

beginning of 1957 (46a).

In addition to the facts above stipulated, the following

was determined upon preliminary hearing and trial con

cerning the action taken by defendants following the reg

istration of the 40 Negro pupils in the elementary schools

of Hillsboro on September 8, 1954. Those pupils were ini

tially assigned seats in regular classrooms in Webster and

Washington. As a result of this there were left only 17 pu

pils attending Lincoln School (65a). In order to correct

the situation the Board of Education of Hillsboro on Sep

tember 13th attempted to reassign pupils to schools on

what was described as a geographical basis. Following

that resolution, on September 17th each of the 7 plaintiffs

received a form letter notifying him that in accordance

with the redistricting of elementary school zones he was

assigned to Lincoln School. Between 35 and 40 other Ne

gro pupils received similar letters (33a-42a).

The redistricting of the schools along geographical

lines produced a curious bit of gerrymandering. Whereas

the Washington and Webster zones were compact contig

uous areas, the Lincoln zone is composed of two non-contig-

uous land areas in the northeast and southeast sections of

the city. Those two non-contiguous areas are 9 blocks

apart and curiously enough the Lincoln School is located

in neither (48a-55a).

5

The redistricting produced the result that only Negro

families resided within the two sections of the Lincoln

zone. Within the Webster zone are 4 Negro pupils and 8

in the Washington zone, those children living on streets on

which white families live (107a, 108a). Since the estab

lishment of the school zones the Board of Education has

allowed certain pupils the choice of transferring from the

Washington and Webster Schools to the Lincoln School,

but has not allowed transfer from Lincoln to either one of

the other two (48a-55a).

Upon trial the District Court below filed its opinion

on January 18, 1955 in which it set forth its reasons for

denying the permanent injunction (139a) followed by its

order on February 16, 1955 denying the permanent injunc

tion (145a) from this order of appellants’ appeal.

ARGUMENT.

1. Did the court below abuse its discretion in refusing

to grant a permanent injunction enjoining appellees from

enforcing a policy of racial segregation in the elementary

schools and from requiring infant appellants to withdraw

from Washington and Webster Schools and enroll in Lin

coln School, solely because of their race and color?

Court below refused a permanent injunction for the

reasons set forth in its opinion.

Appellants and Amicus Curiae contend that the an

swer to the above question should be in the affirmative.

The Court below abused its discretion in refusing to

grant a permanent injunction. We believe that the Court

below in the exercise of its equity powers was bound by

the law of the state and the federal law as of the time of

the decree, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. vs. Sawyer, 343

U. S. 579 (1952). Accordingly it should have exercised its

6

discretion in accordance with the law and enjoined the il

legal acts of the defendants in their capacity as public

officials when those acts violated the constitutional rights

of the plaintiffs.

The ruling of the United States Supreme Court in the

case of Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S.

483, determined that segregation in the public high schools

and elementary schools of the United States as a result of

legislative enactment was unconstitutional. The Court in

holding that segregation was a deprival of the equal pro

tection of the laws guaranteed under the 14th Amendment,

says on page 494,

“to separate them [school children in grade and high

schools] from others of similar age and qualifications

solely because of their race, generates a feeling of in

feriority as to their status in the community that may

affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever

to be undone.”

In the above opinion the Court left open the problem

of implementation of its mandate that segregation in the

public schools be terminated pending further argument

by the parties before the Court. It recognized that there

were a variety of problems existing in the several states

which made difficult the application of universal rules for

ending school segregation. Such additional arguments

were held as a result of which a further opinion was ren

dered by the Supreme Court this year in the case

entitled Brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka,

et al, 349 U. S. 294. The Court held, to begin with, on

page 299:

“Full implementation of these constitutional principles

may require solution of varied local school problems.

School authorities have the primary responsibility of

elucidating, assessing and solving these problems.

7

Courts will have to consider whether the action of

school authorities constitutes good faith implementa

tion of the governing constitutional principles. Be

cause of their proximity to local condition and the

possible need for further hearings the courts which

originally heard these cases can best perform this

judicial appraisal. Accordingly, we believe it ap

propriate to remand the cases to those courts.”

While it recognized that the implementation in each

instance must be left to the action of local Federal Courts,

the Supreme Court nevertheless enunciated principles

which it expected those courts to follow in the course of

its implementation. The Court went on to say:

“At stake is the personal interest of the plaintiffs in

admission to public schools as soon as practicable on

a nondiscriminatory basis. * * * Courts of equity

may properly take into account the public interest in

elimination of such obstacles in a systematic and

effective manner but it should go without saying that

the vitality of these constitutional principles cannot

be allowed to yield simply because of disagreement

with them.”

The burden is placed upon the defendants when addi

tional time is asked in which to desegregate a school

system.

“The burden rests upon the defendants to establish

that such time is necessary in the public interest and

is consistent with good faith compliance at the earliest

practicable date.”

Finally, the Court enumerated some of the factors

which the local tribunals might consider in deciding

whether an extension of time is necessary to complete a

policy of desegregation:

“To that end the courts may consider problems related

to administration, arising from the physical condition

8

of the school plant, the school transportation system,

personnel, revision of school districts and attendance

areas into compact units to achieve a system of

determining admission to the public schools on a non-

racial basis and revision of local laws and regulations

which may be necessary in solving the foregoing

problems. They will also consider the adequacy of

any plans the defendants may propose to meet these

problems and to effectuate a transition to a racially

nondiscriminatory school system.”

We submit that the standards prescribed by the Su

preme Court in the second Brown case do not justify an

extension of time in which to end segregation in Hillsboro.

To begin with, Ohio is not one of the states which was in

cluded among those with segregation laws on the date of

the first segregation case. Whereas it is true that at one

time segregated schools for colored children were provided

for in the Statutes of Ohio1, that statute was repealed by

the General Assembly in 188 72. And following that action

of the 1887 legislature, the Ohio Supreme Court has held

that the effect of the 1887 Act was to abolish separate

schools for colored children and that no regulation may

be made under any other section of the Ohio Code which

does not apply to all children irrespective of race or color.3

Thus Ohio has been inhibited by neither the legal nor social

background of the southern states.

The very most that might happen, as a result of attend

ance by Negro children formerly going to Lincoln at

Washington or Webster Schools instead, is that already

1 Revised Statutes of Ohio 1886, Chapter 9, Section 4008 (see

appendix).

2 84 Laws of Ohio 1887, page 34 (see appendix).

3 Board of Education vs. The State, 45 O. S. 555; Board of

Education of School District of City of Dayton et al. vs. The State,

ex rel. Reese, 114 O. S. 188.

9

overcrowded school rooms will be slightly more crowded.

However, at the time that these 40 students were regis

tered, available seats were found for them the first week

of their attendance. And elementary school registration

at the beginning of the September term of 1954 was less

than that in the term of the previous year.

Defendants urge that upon completion of new build

ings in Webster and Washington Schools classes may be

completely integrated sometime in 1957. This is reported

as an indication showing good faith on the part of the

Hillsboro School Board. We submit that the action of that

same School Board five days after the beginning of the

school year in 1954 in creating a completely arbitrary

system of school redistricting, is a more convincing show

ing of bad faith than is their proposed construction plan

a showing of bona fides. For almost two years the Negro

students in the lower public classes in Hillsboro are being

asked by the school authorities of that city to attend

classes in a segregated school building. The psychological

factors which the Supreme Court enumerated in the first

segregation case will be ever present to burden them for

the next 24 months, and conceivably the sense of inferior

ity which may develop from segregation for two years

may continue to affect the educational and mental devel

opment of those children for many more years in the

future. During those two years, the Negro children of

Hillsboro will be compelled to attend classes in rooms

where one teacher is to supervise three classes, rather

than going to the larger schools at Webster and Washing

ton where school children are assigned to rooms which

have one class apiece. The attention given each grade

during the school day will accordingly be that much less.

There exist no local problems in Ohio which war

rant the continuance of segregation in the public schools

10

for any period of time in the future. The defendants have

utterly failed to maintain their burden by showing that

any such extension of time until 1957 is “necessary in

the public interest.” The disadvantages accruing to the

Negro children of Hillsboro as a result of their continuing

to attend a segregated public school at Lincoln are a mani

festly obvious denial of due process.

CONCLUSION.

In conclusion we submit that the action of the Board

of Education of Hillsboro in instituting segregated primary

schools in the first six grades of Hillsboro, Ohio, was un

constitutional. In view of the prohibition against such

schools by the law of the State of Ohio for almost half a

century, there is no excusable situation existing in the State

of Ohio which requires an extension of time in which

to desegregate the schools of this state completely. In

addition, there is nothing in the local situation within the

community of Hillsboro itself which requires that ad

ditional time be granted in which to integrate all of the

children into one uniform school system. There has been

a complete absence of showing on the part of the defend

ants that there are in the case at bar any of the special

factors which the Supreme Court in the second Brown

case enumerated as justification for an extension of time.

RELIEF.

Therefore Amicus Curiae respectfully urge that the

judgment of the Court below be reversed and the Court be

low be directed to enter an injunction enjoining appellees

from continuing to enforce the racial segregation policy

through enforcement of the so-called school zone lines, and

enjoining appellees from requiring infant appellants to

11

withdraw from the Washington and Webster Schools and

attend Lincoln or any other racially segregated schools in

Hillsboro.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack G. D a y ,

J U L IE N C. R E N S W IC K ,

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae.

a p p e n d ix .

Revised Statutes of Ohio 1886, Chapter 9, Section 4008:

‘When, in the judgment of the Board, [of Education]

it will be for the advantage of the district to do so, it may

organize separate schools for colored children; and boards

of two or more adjoining districts may unite in a separate

school for colored children, each board to bear its propor

tional share of each school, according to the number of

colored children from each district in the school, which

shall be under the control of the Board of Education in

the District in which the school house is situate.

84 Laws of Ohio 1887, page 34:

“ A n A ct

To repeal sections 4008, 6987 and 6988 of the Revised

Statutes of Ohio.

Section 1. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of

the State of Ohio, that Sections 4008, 6987 and 6988 of the

Revised Statutes of Ohio be and the same are hereby

repealed.

Section 2. That this act shall take effect and will be

in force from and after its passage.” (Passed February 22,

1887.)

/