Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody Brief for Respondents, 1974. a4b26167-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aa283ba4-06fb-4784-8461-1098e21b8843/albemarle-paper-company-v-moody-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

K & L <iT£,Aj

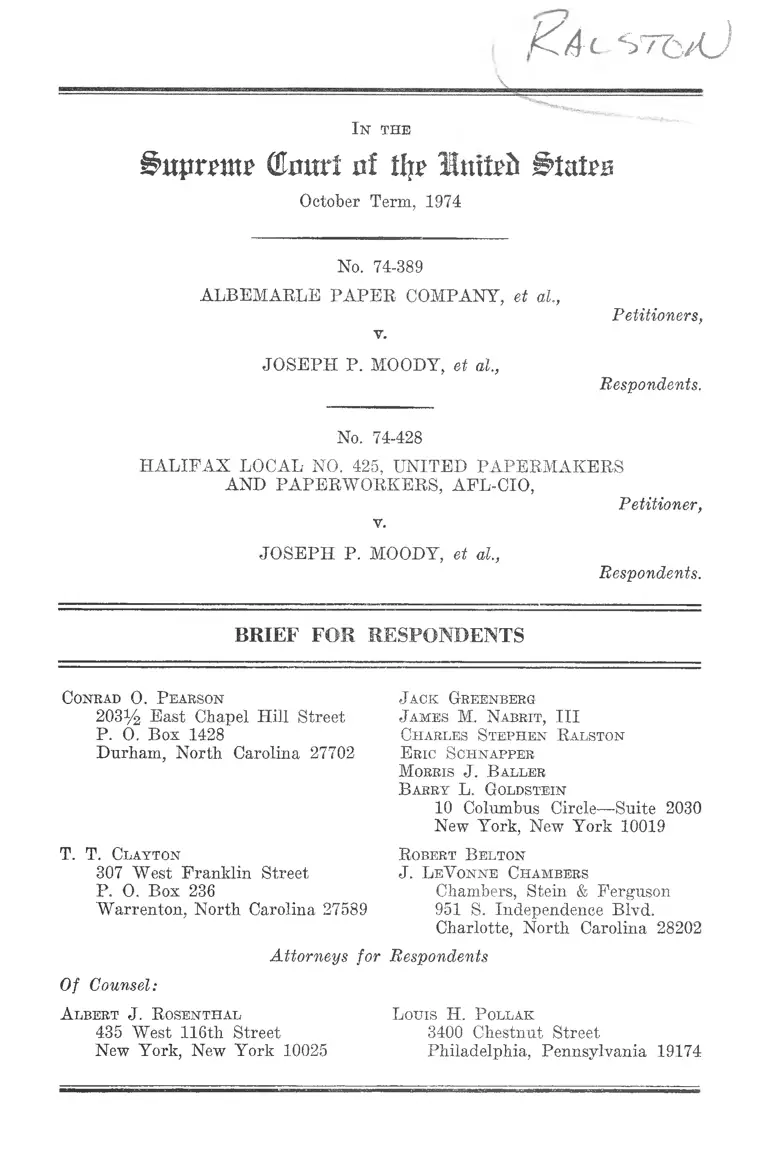

In the

Supreme dour! of tlj? Itufrft BtnUs

October Term, 1974

No. 74-389

ALBEMARLE PAPER COMPANY, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

JOSEPH P. MOODY, et al,

Respondents,

No. 74-428

HALIFAX LOCAL NO. 425, UNITED PAPEEMAKERS

AND PAPERWORKERS, AFL-CIO,

Petitioner,

v.

JOSEPH P. MOODY, et al,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Conrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

P. 0. Box 1428

Durham, North Carolina 27702

T. T. Clayton

307 West Franklin Street

P. 0. Box 236

Warrenton, North Carolina 27589

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrxt, III

Charles Stephen Ralston

E ric Schnapper

Morris J. B aller

B arry L. Goldstein

10 Columbus Circle—Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Robert Belton

J. LeVonne Chambers

Chambers, Stein & Ferguson

951 S. Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Attorneys for Respondents

Of Counsel:

Albert J. R osenthal Louis H. P ollak

435 West 116th Street 3400 Chestnut Street

New York, New York 10025 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19174

I N D E X

PAGE

Table of Authorities ................................... ............ . ii

Questions Presented ....... .._........................................... 1

Statement of the Case .................................................. 2

The Parties .......... .......... ......................... -............. 2

Factual Background .............................................. 3

Proceedings Below ........................... 12

Summary of Argument ..................................... .......... 16

A rgum ent-—

I. Albemarle’s Testing Program Is Unlawful Under

Griggs v. Duke Power Company .... ...................... 18

A. The Tests Adversely Affect Black Employees 19

B. Albemarle Failed to Prove the Job-Related-

ness of Its Testing Program .................... ...... 23

1. Results Showing Lack of Job-Relatedness 24

2. Inadequacy of the Yalidation Study ........ 27

C. Testing Should Be Enjoined............................ 34

II. Back Pay Should Be Awarded Where Discrimina

tory Practices Cause Loss of Earnings and There

Are No Special Circumstances Which Render the

Award Unjust ........ ......................................... ...... 35

A. Back Pay Is An Appropriate Remedy in Title

YII Class Actions .......................................-.... 35

11

PAGE

B. A Standard Directing District Courts to Ex

ercise Their Discretion to Award Back Pay

Unless There Are Special Circumstances

Which Make the Award Unjust Is Appropri

ate in Light of the • Clear Statutory Purpose

of Title YII .................................... ................. 43

C. Back Pay Is a Proper Remedy in This Case .... 60

Conclusion- ................................................................ . 69

Appendix—

Glossary of Technical Terms Relevant to the

Testing Issue ..................................... ................... A1

Table oe Authorities

Cases:

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974)

41, 42, 65

Barlow v. Collins, 397 U.S. 159 (1970) ......................... 30

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d

436 (5th Cir. 1974), cert, denied 42 L.Ed. 2d 308

(1974) .............. 36,43,61,68

Bon Hennings Logging Co. v. NLRB, 308 F.2d 548

(9th Cir. 1962) ................. 50

Boston Chapter N.A.A.C.P., Inc. v. Beecher, 504 F.2d

1017 (1st Cir. 1974) ........ ...................... .................. 22, 23

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir.

1969) ................................... ............. ........13, 37, 42, 44, 46

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 489 F.2d 896 (7th Cir.

1973)... ........................................................................... 37

Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416 U.S. 696

(1974) ...................................................................... 44

PAGE

Brandi v. Reynolds Metals, C.A. No. 170-72-R (E.D.

Va. 1974) (Consent Decree) .......... ... .............. .........

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Civil Service Commis

sion, 482 F.2d 1333 (2nd Cir. 1973) ......... ............. 22,

Brito v. Zia Co., 478 F.2d 1200 (10th Cir. 1973) ..... .21,

Brooklyn Savings Bank v. O’Neil, 324 U.S. 697 (1944)

Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, 339

F. Supp. 1108 (N.D. Ala. 1973), aff’d per curiam

476 F.2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1973) ....... ............................

Buncher v. NLRB, 405 F.2d 787 (3rd Cir. en bam

1969), cert, denied 396 U.S. 828 (1969) ....... ...........

Burks v. Babcock & Wilcox Company, C.A. No. 71-C-

59L (E.D. Ya. 1974) (Consent Decree) .................

Bush v. Lone Star Steel Corp., 373 F. Supp. 526 (E.D.

Tex. 1973) ....... ............. ...........................................37,

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1972),

upheld 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir. en banc), cert, denied

406 U.S. 950 (1972) ......................................... .........22,

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972) ...... .

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (2nd

Cir. 1972) ..................... ............... ............ ............ -22,

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. O’Neill, 348 F.

Supp. 1084 (E.D. Pa. 1972), aff’d in pert, part 473

F.2d 1029 (3rd Cir. en banc 1973) ___ ___ ______ 22,

Cooper v. Philip Morris, Inc., 9 EPD 1(9929 (W.D.Ky.

1974) ........................ ............ -.............................

Costello v. United States, 365 U.S. 265 (1961) ...........

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., 421 F.2d 888 (5th

Cir. 1970) .......... ....................... ................................

Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189 (1974) ..................18,56,

Davies Warehouse Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 144 (1944)

Davis v. Washington,-----F.2d ------- (D.C. Cir. No.

72-2105, Feb. 27, 1975) ..............................................

58

28

28

65

56

50

58

54

28

22

28

28

37

65

58

57

55

22

IV

PAGE

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Co., 406

F.2d 399 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied 403 U.S. 912

(1971) ........................................................................ 41

Douglas v. Hampton, ----- F.2d ----- (D.C. Cir. No.

72-1376, Feb. 27, 1975) ..................................... 22,23,28

Duhon v. G-oodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 494 F.2d 817

(5th Cir. 1974) ....................... .............. ..................... 21

EEOC v. Rank of America, Inc., C.A. No. C-71409CB-R

(N.D.Cal. 1974) (Consent Decree) ....... ...... .............. 58

EEOC v. Container Corporation of America, C.A. No.

72-336-Civ.-J-T (M.D.Fla. 1974) (Consent Decree)__ 58

EEOC v. Continental Trailways, C.A. No. SA72-

CA197 (W.D.Tex. 1973) (Consent Decree) ....... 58

EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co.,----- F.2d------ (6th Cir.

No. 74-1007, March 11, 1975), aff’g in pert, part

Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 365 F. Supp. 87 (E.D.

Mich. 1973) ........ ........................ ............................. . 37

EEOC v. Preston Trucking Co., C.A. No. 72-632-M

(D. Md. 1973) (Consent Decree) .......... ................. 58

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 417 U.S. 156 (1974)__ 65

Espinoza v. Farah Manufacturing Co., 414 U.S. 86

(1973) ..... 30

Fishgold v. Sullivan Dry Dock & Repair Corp., 328

U.S. 275 (1946) .............. 30

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495 F.2d 398

(5th Cir. 1974), cert, denied 42 L.Ed.2d 644 (1974)

21, 36, 43

Gardner v. Panama Railroad Co., 342 U.S. 29 (1951) .... 65

Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968) ................... .......... ......... ............................ 54

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)

1, 6,13,16,18,19, 21, 22, 23, 27, 30, 34, 60

V

PAGE

Hall v. Werthan Bag Co., 251 F. Supp. 184 (M.D. Tenn.

1966) ................................................ ........................... 12

Head v. Timken Boiler Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870 ( 6th

Cir. 1973) ................ .............. ................... 36, 43, 45, 61, 62

Head v. Timken Boiler Bearing Co., 6 EPD *]J8679 (S.D.

Ohio 1972), rev’d 486 F.2d 870 (6th Cir. 1973) .......... 54

In ti Ass’n of Heat, Frost & Asbestos Workers, Local

53 v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969) ............ 55

J. I. Case Co. v. Borak, 377 U.S. 426 (1964) ........ ......... 52

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 417 F.2d

1122 (5th Cir. 1969) ........ ............................. ........... 13,46

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364

(5th Cir. 1974) _______ ____19,21,36,43,48,56,61,62

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 349 F. Supp. 3

(S.D. Tex. 1972), rev’d 491 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974) 54

Johnson v. Seaboard Air Line Railroad Co., 405 F.2d

645 (4th Cir. 1968), cert, denied 394 U.S. 918 (1969) 41

Jurinko v. Wiegand Co., 477 F.2d 1036 (3rd Cir. 1973),

vacated on other grounds 414 U.S. 970 (1973), rein

stated 497 F.2d 403 (3rd Cir. 1974) ........................... 44

Kirkland v. New York State Department of Correc

tional Services, 374 F. Supp. 1361 (S.D. N.Y. 1974) 28

Kober v. Westinghouse. Electric Corp., 480 F.2d 240

(3rd Cir. 1973) ................................................... 55, 61, 62

Laffey v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 7 EPD ^9277

(D.D.C. 1974), entering order following 366 F. Supp.

763 (D.D.C. 1973) ............... ..................................... 37

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp,, 301 F. Supp. 97 (M.D.N.C.

1969), aff’d in pert, part 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971) 55

vi

PAGE

LeBlanc v. Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Co.,

460 F.2d 1228 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied 409 U.S.

990 (1973) ........ ......... .............. ........................ -.....-55, 62

Local 186, International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite

& Paper Mill Workers v. Minnesota Mining and

Manufacturing Co., 304 F. Supp. 1284 (N.D. Ind.

1969) ........... ............. .................................— -........ 38, 41

Local 189, United Papermakers & Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert.

denied 397 U.S. 919 (1970) .................... ......... ........ .. 3

Long v. Georgia Kraft Co., 450 F.2d 557 (5th Cir. 1971) 3

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965)----- 45, 54

Mack v. General Electric Co., C.A. No. 69-2653 (E.D.

Pa. 1973) (Consent Decree) ..... ............. .............— 58

Manning v. International Union, 466 F.2d 812 (6th Cir.

1972) , cert, denied 409 U.S. 1086 (1973) ......... .....55, 62

Mastro Plastics Corp. v. NLRB, 350 U.S. 270 (1956).... 50

McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) 41

Meadows v. Ford Motor Co., ----- F.2d ----- , 9 EPD

H9907 (6th Cir. 1975) .............................. ........ —36,43,56

Mitchell v. Robert De Mario Jewelry, Inc., 361 U.S. 288

(1960) .......... ............. ............................. .............45, 52, 57

Mitchell v. Robert De Mario Jewelry, Inc., 260 F.2d 929

(5th Cir. 1958) ______ _____________ __________ 52

Mize v. State Division of Human Rights, 33 N.Y.2d 53,

349 N.Y.S.2d 364 (N.Y. Ct. of Appeals, 1973) ........ 45

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134 (4th Cir.

1973) ......... .......................................... ..... ..............passim

Myers v. Gilman Paper Co., 9 EPD f[9920 (S.D. Ga.

1975)... .................... ...................................... ................ 37

Nathanson v. NLRB, 343 U.S. 25 (1952) ................... ..50, 59

NLRB v. A.P.W. Products Co., 316 F.2d 899 (2nd Cir.

1963), enfing 137 NLRB 25 (1962) 50

vn

PAGE

N.L.R.B. v. Boeing Co., 412 U.S. 67 (1973) ................... 28

NLRB v. International Union of Operating Engineers,

Local 925, 460' F.2d 589 (5th Cir. 1972) ............. ..... . 50

NLRB v. Mastro Plastics Corp., 354 F.2d 170 (2nd Cir.

1965), cert, denied 384 U.S. 972 (1966) ..................... 50

NLRB v. Rice Lake Creamery Co., 365 F.2d 888 (D.C.

Cir. 1966) .......................................................... -........ 50

NLRB v. Rutter-Rex Manufacturing Co., 396 U.S. 258

1969) .............................. ....................................-50, 59, 66

NLRB v. Seven Up Bottling Co., 349 U.S. 344 (1953) 50

National Organization of Women v. Bank of Cali

fornia, 6 EPD U8867 (N.D. Cal. 1973) .......... .......... 56

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ...... ............ ............ .......................................18, 59

Norman v. Missouri Pacific Railroad, 479 F.2d 594

(1974), cert, denied 43 LW 3416 (1975) ............. .....44,62

Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496 (5th

Cir. 1968) ................... 13,38,42

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 8 EPD ft9722

(E.D. Ya. 1974) ..... .................... .............................. 37

Patterson v. N.M.D.U., C.A. No. 73-Civ.-3058 (S.D.

N.Y. 1974) (Consent Decree) ............ 58

Pennsylvania Greyhound Lines, Inc., 1 NLRB 1 (1935),

enfd sub nom. NLRB v. Pennsylvania Greyhound

Lines, Inc., 303 U.S. 261 (1938) ................................ 50

Pettit v. United States, 488 F.2d 1026 (U.S. Ct. Cls.

1973) ........................................................................... 45

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974) ........................ 28, 36, 43, 45, 48, 56, 61, 68

Phelps Dodge Corp. v. NLRB, 313 U.S. 176 (1941) ....49, 50

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U.S. 395 (1946) ....52, 57

V lll

PAGE

Power Reactor Development Co. v. Electrical Union,

367 U.S. 396 (1961) ............................ ..................... 28

Rental Development Corp. of America v. Lavery, 304

F.2d 839 (9th Cir. 1962) ........ ......................... ......... 67

Roberts v. Hermitage Cotton Mills, Inc., 8 EPD f{9589

(D.S.C. 1973), aff’d 498 F.2d 1397 (4th Cir. 1974) .... 55

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.

1971), cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1971) ....14,36,46,

61, 65, 67, 68

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 319 F. Supp. 835 (M.D.

N.C. 1970) ................................................... 53

Rodriguez v. East Texas Motor Freight Co., 505 F.2d

40 (5th Cir. 1974) ...................................................... 36

Rogers v. International Paper Co., ----- F.2d ----- ,

9 EPD 1(9865 (8th Cir. 1975) .....3,19, 21, 22, 23, 28, 32, 33

Rosen v. Public Service Gas & Electric Co., 409 F.2d

775 (3rd Cir. 1969) ................... .................... ..........36, 66

Rosen v. Public Service Electric & Gas Co., 477 F.2d

90 (1973) ...................... 36,44,45

Rosenfeld v. Southern Pacific Company, 444 F.2d 1219

(9th Cir. 1971) ...................................... .................... 55

Russell v. American Tobacco Co., 374 F. Supp. 286

(M.D.N.C. 1973) ................................................ 37

Schaeffer v. San Diego Yellow Cabs, Inc., 462 F.2d

1002 (9th Cir. 1972) ............................ ...................... 55

Schulte v. Gangi, 328 U.S. 108 (1946) ..... ... 65

Snyder v. Harris, 394 U.S. 332 (1969) ......... 42

Sosna v. Iowa, 42 L.Ed.2d 532 (1975) ......... 43

Sprogis v. United Air Lines, Inc., 444 F.2d 1194 (7th

Cir. 1972), cert, denied 404 U.S. 991 (1971)...... 37,44,46,

58, 66

IX

PAGE

Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 365 F. Supp. 87 (E.D.

Midi. 1973), aff’d in pert, part sub nom EEOC v.

Detroit Edison Co.,----- F.2d------ (6th Cir. No. 74-

1007, March 11, 1975) .........................................- .... 21

Stevenson v. International Paper Co., 352 F. Supp.

230 (S.D. Ala. 1972), on appeal 5th Cir. No. 73-1758 22

Suggs v. Container Corporation of America, C.A. No.

7Q58-72-P (S.D. Ala, 1974) (Consent Decree) ------ 58

Swann v. Charlotte-Meeklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ...................................................... 54

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 409 TJ.S. 205

(1972) ......................................................................... 28

ITdall v. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1 (1965) .................. -......... 28

United States v. Bricklayers, Local No. 1, 5 EPD

U8480 (W.D. Tenn. 1973), aff’d sub nom United

States v. Masonry Contractors Assn, of Memphis,

Inc., 497 F.2d 871 (6th Cir. 1974) ............... -............ 54

United States v. City of Chicago, 400 U.S. 8 (1970)..- 28

United States v. East Texas Motor Freight System,

C.A. No. 3-6025-B (N.D.Tex. 1974) (Consent Decree) 58

United States v. Eastex, Inc., C.A. No. B-73-CA-81

(E.D.Tex. 1974) (Consent Decree) ........ -............... 57

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th

Cir. 1973) .............. ............. -............................ ..21,25,28,

36, 45, 48

United States v. Hayes International Corp., 456 F.2d

112 (5th Cir. 1972) ........ ..................... -......-........... 43,66

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d 544

(9th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 404 U.S. 984 (1971).— 55

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d

418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 406 U.S. 906 (1972)

21,28

X

pa g e

United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354

(8th Cir. 1973) ................................................. 37,44,45,

58, 61, 62

United States v. Philadelphia Electric Company, C.A.

No. 72-1483 (E.D.Pa. 1973) (Consent Decree).,....... 57

United States v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 464

F.2d 301 (8th Cir. en banc 1972), cert, denied 409

U.S. 1107 (1973) ......................................................44,62

United States v. United States Steel Corp., 371 F.

Supp. 1045 (N.D.Ala. 1973) ..... .............................. 56

Yogler v. McCarty, Inc., 451 F.2d 1236 (5th Cir. 1971) 55

Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d

387 (2nd Cir. 1973) ........ ........................... ............. 23,28

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., 502 F.2d 1309 (7th Cir. 1974)____ 61

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 6 EPD H8912 (S.D. Ala.

1973) , on appeal 5th Cir. No. 74-1001 ........... ....... 22

Western Addition Community Organization v. Alioto,

340 F. Supp. 1351 (N.D. Cal. 1972) ........................ 28

Young v. Edgcombe Steel Co., 499 F.2d 97 (4th Cir.

1974) ................. ...................................................19, 21, 28

Zahn v. International Paper Co., 414 U.S. 291 (1973) 42

Legislative Materials:

Statutes—

15 U.S.C. §§77b et seq. (Securities Exchange Act

of 1934) .................................. .............................. 52

28 U.S.C. §1332(a) ..................... ............. ......... 42

28 U.S.C. §1343 ...... ........................................... . 42

XI

PAGE

29 U.S.C. §§151 et seq. (National Labor Relations

Act) ............................. -........-....-17,48, 49, 50, 51, 59

29 UjS.C. §160(c) - ...............- ........... -........... 48

29 U.S.C. §209 et seq. (Fair Labor Standards Act)

52, 53

29 U.S.C. §215(a) (3) .............................................. 52

29 IT.S.C. §217 ----- -----.....- ......... -............ -......... - 53

42 U.S.C. §2000a-3(b) ................ -..............-......— 59

42 UjS.C. §§2000(e) et seq. (Title VII, Civil Rights

Act of 1964) .................................................... passim

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h) ......... -....... -.......... - ............ 18

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(b) ............................- .............. 41

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(£) (1) ............-----......... -........ -41,43

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f) (4) ............... -............. -......... 42

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5 (f)(5) ------ ------ -----........-........ 42

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g) .....-15, 37, 40, 46, 48, 49, 51, 53, 60

42 U.S.C. §3612 — -...... -.... -.......... -----.....- ............... 56

P.L. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103 (Equal Employment Op

portunity Act of 1972) ....... ...............- — 37

Legislative History—

110 Cong. Rec. 6549 (1964) .

110 Cong. Rec. 7214 (1964) .

110 Cong. Rec. 12723 (1964)

110 Cong. Rec. 12807 (1964) 51

X l l

pa g e

110 Cong. Rec. 12814 (1964) ................. ................ 51

110 Cong. Rec. 12819 (1964) ...... ............... ........... 51

117 Cong. Rec. 212 (1971) .............................. ....... 38

117 Cong. Rec. 20622 (1971) .............. 38

117 Cong. Rec. 31973 (1971) ............... 40

117 Cong. Rec. 32097 (1971) .......... 40

117 Cong. Rec. 34104 (1971) . 38

117 Cong. Rec. 38030 (1971) .. 38

118 Cong. Rec. 3808 (1972) _ 39

118 Cong. Rec. 4917 (1972) ........ 46

118 Cong. Rec. 4942 (1972) _ ...39,46,47

118 Cong. Rec. 4944 (1972) . 39

118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972) _____ ...40,46,47

118 Cong. Rec. 7170 (1972) . 40

118 Cong. Rec. 7565 (1972) . 40

118 Cong. Rec. 7573 (1972) .. . 40

H.R. 1746 (1971) .................... ........................38,39,46

H.R. 7152 (1963) ........................ .................... ....... 51

H.R. 9247 (1971) ..................................... .............. 37

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong. 1st Sess. (1963) .... 48

S. 2515 (1971) ........ .................................... ...38,39,46

S. 2617 (1971) ............................... .......................... 38

S. Rep. 415, 92 Cong. 1st Sess. (1971) 38

XU1

page

Regulations and Rules:

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure—

Rule 23 ........... .............. -....-..................................- 36

Rule 23(b)(2) .................................................... 12

Rule 23(e) ..... ................ .......- ............................. 65

Rule 54(c) ......................... ........................13,64,65,67

3 C.F.R. 339 (1965) (Executive Order 11246) ..... ... 29

29 C.F.R. § 1607 (1970) (EEOC Guidelines on Em

ployee Selection Procedures) ........................ 27, 28, 29, 30

29 C.F.R. § 1607.1(c) .......................... ........................... 28

29 C.F.R. § 1607.4 ...... ............ ....................................... 19

29 C.F.R. § 1607.4(a) .......................... .........................- 19

29 C.F.R. § 1607.4(c) (2) ................... ............................ 34

29 C.F.R. § 1607.5(a) ................................. ................... 28

29 C.F.R. § 1607.5(b)(3) ................... .............. .............. 31

29 C.F.R. §1607.5(c)(3) ............................................... . 32

29 C.F.R. § 1607.5(c) (4) ..................................... .......... 32

29 C.F.R. § 1607.7 ................. ......................................... 31

29 C.F.R. § 1607.9........................................................... 35

29 C.F.R, §1607.9(a) ..................................................... 35

29 C.F.R. § 1607.9(b) ..................................................... 35

41 C.F.R. §§ 60-3.1 et seq. (“Testing and Selecting Em

ployees by Government Contractors”) (1971), as

amended Jan. 17, 1974) ........ ............................ .......29, 31

XIV

PAGE

Other Authorities:

Advisory Committee’s Note to Proposed Buies of Civil

Procedure, Rule 23, 39 F.R.D, 69, 102 (1966) ____ 36

American Psychological Association, Standards for

Educational and Psychological Tests and Manuals

(1966) ................................... - .................. .......... 29, 30, 31

American Psychological Association, Standards for

Educational and Psychological Tests and Manuals,

(1974) ........... - ............... .......................... ............. --29, 31

Anastasi, Psychological Testing, London: MacMillan

(3rd ed. 1968) ..... ...............................31, Al, A2, A3, A4

Byham & Spitzer, The Law and Personnel Testing

(American Management Assn., publisher) (1971).... 31

Cronbach, Essentials of Psychological Testing, New

York: Harper & Row (1970)..................... 31, 33, A2, A4

Davidson, “Bach Pay” Awards Under Title VII of

the Civil Plights Act of 1964, 26 Rutgers L. Rev. 741

(1973) ................ .............................................. -......... 48

Development in the Law—Employment Discrimination

and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 84

H a r v . L. R ev. 1109 (1971) ................. ................--48,59

E. F. Wonderlic Associates, Inc., Negro Norms, A

Study of 38,452 Joh Applicants for Affirmative Ac

tion Programs (1972) .................................... .......... 21

E. F. Wonderlic Associates, Wonderlic Personnel Test

Manual (1961) ........................................................... 26

Frankfurter, Some Reflections on the Reading of

Statutes, 47 Con. L. R ev. 527 (1947) 50

XV

pa g e

Ghiselli, The Validity of Occupational Aptitude Tests,

New York: John Wiley (1966) ......... .................... . A2

Guion, Personnel Testing, New York: McGraw-Hill

(1965) ............................................ ........... -........ 31, 32, A2

Kirkpatrick et al, Testing and Fair Employment, New

York: New York University Press (1968) .............. . Al

6 Moore’s Federal Practice (2d ed. 1974) (154.62 .......... 65

NLRB Annual Report, Yol. 1 (1936) ..... ...................... 50

NLRB Annual Report, Vol. 2 (1937) ........ ..... .......... . 50

Note, Title VII, Seniority Discrimination and the In

cumbent Negro, 80 H arv. L. R ev. 1260 (1967) ...... 56

Sape & Hart, Title VII Reconsidered: The Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Act of 1972, 40 Geo. W a sh .

L. R ev. 824 (1972) .................................... ................. 46

10 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure

§§2262,2664 (1973) 65

I n t h e

imprint? OInurt of % United States

October T erm , 1974

No. 74-389

A lbemarle P aper Company , et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

J oseph P . M oody, et al.,

Respondent's.

No. 74-428

H alifax L ocal N o. 425, U nited P a p e r m a k f.bs

and P aperworkers, AFL-CIO,

Petitioners,

v.

J oseph P . M oody, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

Questions Presented

I. Whether Albemarle’s Testing Program Is Impermis

sible Under Griggs v. Duke Power Company—

A. Did Albemarle’s tests disproportionately exclude

black employees from jobs previously closed to

them by overt segregation ?

2

B. Did Albemarle fail to prove its testing program

job-related ?

C. Should Albemarle’s unlawful testing program be

enjoined?

II. Whether the Plaintiff Class Is Entitled to an Award

of Back Pay—

A. Is the class back pay award within the District

Court’s power to provide a remedy for employment

discrimination under Title ¥11?

B. Did the Court of Appeals state an appropriate

standard for the exercise of remedial power to

award back pay in keeping with the statutory

purpose?

C. Are there specific factors which would warrant

denial of the back pay remedy in this case?

Statem ent o f the Case

T he Parties

This case is a certified class action brought by a group

of black paper mill workers who seek relief from practices

of employment discrimination by their employer and union

in violation of Title VII of the Civil Eights Act of 1964,

42 IJ.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. (A. 46-7, 474).

The paper mill, located in Eoanoke Bapids, North

Carolina, is fully described in the brief of Petitioner

Albemarle (Co. Br. 4-10). The Petitioners, defendants

below, are various corporations which have or had an

interest in ownership of the mill and the local labor union

3

which represents the mill’s hourly paid employees (A.

476).1 Plaintiffs Moody and others are black employees or

former employees of Albemarle and members or former

members of Local 425. Plaintiffs represent a class of per

sons determined by the district court to include all Negro

employees at the mill as of June 30, 1967, and all Negro

employees at the mill thereafter who might be subjected

to discrimination in initial job assignment or otherwise

(A. 54, 474).

Factual Background

Albemarle’s mill is functionally similar to other primary

pulp-and-paper facilities (A. 477). As in other Southern

paper mills, prior to the effective date of the Civil Bights

Act of 1964, race was the absolute determinant of em

ployment opportunities (A. 352).2 The district court found

that

Prior to January 1, 1964, Albemarle’s lines of pro

gression were strictly segregated on the basis of race.

Those lines of progression to which black employees

were traditionally assigned were lower paying than

the “white” lines of progression (A. 480).

1 The Petitioners in No. 74-389 are referred to herein as “Albe

marle” or the “Company”. Petitioner in No. 74-428 is referred to

as “Local 425” or the “Union.” Both are sometimes referred to as

“defendants”. Respondents Moody et al. are sometimes referred

to as “plaintiffs”.

2 The Southern pulp-and-paper industry’s nearly uniform dis

crimination practices have engendered dozens of Title VII suits.

See, for example, Local 189, United Papermakers & Paperworkers

v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied 397

U.S. 919 (1970); Long v. Georgia Kraft Co., 450 F.2d 557 (5th

Cir. 1971); and Rogers v. International Paper Co.,----- F .2d------ ,

9 EPD 1J9865 (8th Cir. 1975).

4

The lines of progression (hereinafter “LOPs”) reserved

for whites included all 13 “skilled” lines.3 Blacks were

restricted to the remaining 6 LOPs.4 Whites had access to

approximately 86 jobs in the white LOPs while blacks were

limited to approximately 14 jobs in their inferior LOPs

(A. 477).

Employees promoted to the racially segregated LOPs

from racially segregated “extra boards,” which are essen

tially labor pools (A. 217). From the whites-only General

Extra Board, employees moved into the all-white “skilled”

lines of progression (A. 485, 219); the black Utility Extra

Board fed the black “unskilled” LOPs (id.). Employees

forced out of LOPs due to reduction-in-force went to the

respective extra boards, and there retained priority recall

rights to their former LOPs, in accordance with the segre

gated pattern (A. 485, 104).

In addition to the segregated production classifications

arranged in LOPs, Albemarle employed over 100 mechanics

in a Maintenance Department (A. 488-9, 484). Until 1964

no black person ever worked in Maintenance (A. 489).

Prior to the mill modernization of the 1950’s, Albemarle

had no educational or testing requirements for employees

(A. 487-8). In 1952-3 it introduced a high-school education

requirement for new hires into “skilled” progressions

3 Yard Crew LOP and Knife Grinder Job in the Woodyard

Department; Paper Machine and Beaterman LOPs in the A Paper

Mill Department; Finishing Crew, Shipping Crew, Paper Machine,

and Stockroom LOPs in the B Paper Mill Department; Digester

and C.B. Recovery LOPs in the Pulp Mill Department; Boiler

Operator LOP in the Boiler Room Department;, and the Mill and

Laboratory LOPs in the Technical Services Department (A. 89).

4 Chipper Operator and Service Crew LOPs in the Woodyard;

Brokeman and Lead Loader LOPs in the A Paper Mill; Payloader

LOP in the Pulp Mill; First Fireman LOP in the Boiler Room;

and the “dead-end” janitor job (A. 89).

5

(A. 487, 237-8). Then in 1955-6, it introduced testing re

quirements for such new employees (A. 486, 329, 338). Un

der these policies, applicants had to satisfy the educational

requirement and to achieve specified passing scores on the

Revised Beta Examination and the Bennett Test of Mechan

ical Aptitude (A. 486). Albemarle fixed the passing scores

on the basis of a concurrent validation study purportedly

done on the two tests by the Company’s then Personnel

Manager after their introduction (A. 329-331, 340, 486-7).5

Albemarle presented undocumented testimony that this

study showed a significant correlation between Beta test

scores and job performance in one department, the B Paper

Mill (A. 99, 486-7, 330, 340-1). The study of the Bennett

test, however, evidenced a negative correlation with job

performance, i.e., the higher the test score, the less likely

the testee was to succeed on the job (A. 330-1).

After about five years, Albemarle discontinued use of

the Bennett because of the negative results, and decided to

substitute a verbal intelligence test (A. 331). Based on the

Personnel Manager’s general familiarity with the Wonder-

lie Personnel test, and without attempting to validate it,

Albemarle adopted the Wonderlic late in 1963 and used it

subject to the nationally recommended cut-off score (A. 100,

487, 331-2). Since 1963, the Company has required both

high school education and scores of 100 on the Beta test

and 18 on the Wonderlic test (either Form A or Form B)

for hiring or transfer into the “skilled” LOPs and the

B The individual who performed that study, Mr. Warren, did

not testify. One witness who described the study, Mr. Bryan, was

not at Albemarle until 1963 (Bryan deposition, plaintiffs’ exhibit

32, p. 487 [not printed in Appendix]); the other witness, Mr.

Boinest, admitted that he was “not a testing expert [;] I know noth

ing about the details of tests,” and had only vague recollections of

the study (A. 340-3). The validation study results were never re

duced to writing; the only report of results was oral (A. 334-5).

6

Maintenance Department (A. 487, 99,100, 332). Employees

who worked in such positions before the introduction of

these standards, however, were not required to qualify in

order to retain their jobs or promote further in their LOPs

(A. 488). Albemarle’s application of educational and test

ing requirements to incumbent employees is closely similar

to practices held unlawful in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., see

401 TJ.S. 424, 427-8 (1971).

The Wonderlic test—the same test involved in Griggs—

is a short intelligence test designed to measure verbal

facility.6 The Beta test is a written non-verbal examination

6 The test appears at A. 297-300 (Form A) ; A. 301-304 (Form

B). The Wonderlic was developed by 1942 (A. 297, 301). Ques

tions on the Wonderlic test include the following:

[Form A] # 4 •—Answer by printing Y es or No—Does

RSVP mean “reply not necessary” ?

#23—Two of the following proverbs have the same

meaning. Which ones are they?

1. Many a good cow hath a bad calf.

2. Like father, like son.

3. A miss is as good as a mile.

4. A man is known by the company the

keeps.

5. They are seeds out of the same bowl.

#28—I ngenious I ngenuous—Do these words have

1 similar meanings, 2 contradictory, 3 mean

neither the same nor opposite?

#47—Assume that the first two statements are

true. Is the final one: 1 true, 2 false, 3 not

certain: Great men are ridiculed. I am

ridiculed. I am a great man.

#50—In printing an article of 30,000 words, a

printer decides to use two sizes of type.

Using the larger type, a page contains 1200

words. Using the smaller type, a page con

tains 1500 words. The article is allotted

22 pages in a magazine. How many pages

must be in the smaller type ?

7

designed to measure the intelligence of non-English speak

ing persons or illiterates.7 Albemarle’s employment records

show that black employees achieved lower scores than

whites on both the Beta and Wonderlic tests and that blacks

more frequently failed the tests (PL Ex. 10, PI. Ex. 73,

Co. Br. 29).

In 1964-5, the Company twice offered black employees

the opportunity to transfer to white LOPs; Albemarle still

required the employees to pass the tests but waived the

high school requirement for those found test qualified

(A. 225-6). The court found that some blacks passed and

transferred, but that “a majority of those who took the

tests failed them” (A. 488). Those who failed remained

trapped in their traditional LOPs after 1965.

[Form B] #11—Are the meanings of the following sentences:

1 similar, 2 contradictory, 3 neither similar

nor contradictory?

A faithful friend is a strong defense. They

never taste who always drink.

#26—Assume that the first 2 statements are true.

Is the final statement: 1 true, 2 false, 3 not

certain? Most business men are progres

sive. Most business men are Republicans.

Some progressive people are Republicans.

#42—Censor Censure—Do these words have

1 similar meanings, 2 contradictory, 3 mean

neither same nor opposite?

#50—Three men form a partnership and agree

to divide the profits equally. X invests

$5500, Y invests $3500, and Z invests $1000.

If the profits are $3000, how much less does

X receive than if the profits were divided in

proportion to the amount invested!

7 Because the Beta test is pictorial rather than verbal, illustrative

questions cannot conveniently be reproduced here. The test ap

pears at A. 458-71. I t was developed by the U.S. Army during

World War I and last revised in 1946 (A. 487, 458).

8

Job segregation was reinforced before and after 1965 by

a “job seniority” system governing employees’ rights of

promotion, transfer, demotion, layoff, and recall (A, 477-8).

This system, which remained in effect until 1968, recognized

three types of seniority: job seniority, defined as length of

continuous service in a particular job classification in an

LOP (or in any higher job in the same LOP) (A. 95, 288,

215-6); department seniority, defined as length of con

tinuous service in a particular department (A. 95, 288,

215); and plant or mill seniority, defined as length of

continuous service at the Roanoke Rapids facility (id.).

Job seniority governed employee movement; promotions

went to the employee with most job seniority in the next

LOP job below the vacancy (A. 288).8 Demotion due to

workforce reduction was imposed on the employee with

least job seniority (id.). Plant seniority governed layoffs

out of the labor pool (extra boards) as well as noncompeti

tive employee benefits, but had no bearing on job competi

tion (A. 216). Since black employees were not in white

jobs or LOPs, they could not, under this system, accumulate

any seniority in the “skilled” or white jobs.9

Although Albemarle and Local 425 contended that they

ceased overt discrimination by the effective date of Title

VII, July 2, 1965, the record shows and the district court

found little actual integration of jobs after 1964. As of

June 30, 1967, almost every job and LOP remained totally

segregated. Only 6 of some 105 job classifications had both

8 The seniority provisions governing production employees in

LOPs were inapplicable to Maintenance positions (A. 105, 222),

and a production worker had no seniority right to transfer to any

Maintenance job or to retain any accumulated seniority if he did

so transfer (A. 222, 295).

9 The racially discriminatory nature of this seniority system, in

the circumstances of the Southern pulp-and-paper industry, has

been widely recognized by the federal courts. See cases cited in

n.2, supra.

9

white and black employees; 21 had only blacks and 76 only

whites (2 were not occupied) (A. 481-484). Eleven LOPs10

remained all white; four LOPs11 were all black; only five

LOPs12 had both white and black employees, and they were

“integrated” to only a token degree. The Maintenance

Department consisted of 137 whites and one black, a 6th

(level) Maintenance Employee Apprentice (A. 484). The

extra boards remained racially distinct with 50 blacks and

no whites on the Utility Extra Board and 62 whites, 2

blacks on the General Extra Board (A. 484-5). Based on

these figures, the district court found that, “[t]he racial

identifiability of jobs and departments in lines of progres

sion were maintained subsequent to the effective date of

Title YII (July 2, 1965)” (A. 480).

Albemarle and Local 425 negotiated certain changes in

the seniority and transfer provisions of their collective

bargaining agreement in 1968 (A. 479-80, 227). These

changes did not eliminate the discriminatory features of

defendants’ seniority system (A. 495-7, 499).13 An unlawful

10 Service Crew (Woodyard), Digester Capper, Caustic Operator,

and C. E. Recovery Operator (Pulp Mill), Beaterman (A Mill),

Stock Room (B Mill), Shipping Crew (B Mill Product), Power

Plant, Boiler Room, Technical Service-Mill, Storeroom. Compare,

A. 110, A. 481-4.

11 Chipper Operator (Woodyard), Payloader (Pulp Mill), Broke-

man and Finishing Room (A Mill). Id.

12 Yard Crew (Woodyard) (one black in lowest job only), Paper

Machine (A Mill) (one black in next to lowest job), Paper Machine

(B Mill) (one black in lowest job), Finishing Crew (B Mill

Product) (two blacks), Technical Service—Lab (one black in lowest

job). Id.

13 The 1968 seniority changes gave employees the right to apply

in writing for transfer to another LOP (Section 10.2.1, A. 479,

214, 239-40). The. decision whether to allow such transfer and the

choice among applicants remained within the Company’s sole and

uncontrolled discretion (id.). When such transfer was allowed,

the transferring employee immediately lost his seniority in his pre

vious department, and could recover it only in the event his health

10

seniority system remained in effect until entry of the

district court’s decree (A. 499-507).

The Company and Union also agreed in the 1968 contract

to a number of structural changes in the LOPs (A. 485).

The district court found this restructuring of LOPs “had

the effect of eliminating, to -some extent, their strictly

segregated composition. However, it is to be noted that

black employees were still ‘locked’ in the lower paying job

classifications” (A. 485).14 The continuing “lock-in” of

blacks w-as predictable, since the “mergers” were imple

mented in a manner that minimized opportunities for black

employees.15 Thus, while the 1968 LOP changes may have

helped to rationalize the Company’s progressions from a

or physical condition required a transfer back; apart from this

eventuality the initial transfer was irrevocable (id.). Albemarle

recognized the right to transfer only to the bottom-level position

in a new LOP (A. 292). The contract gave transferring employees

department and job seniority in their new classification equal to

their previously accumulated seniority (Section 10.2.2, A. 479) ;

however it did not provide for the use of such “carry-over” job

seniority in subsequent promotions to positions above the classifica

tion transferred into (A. 479, 239). The contract did provide for

carry-over rate retention or “red-circling” privileges (Section 10.2.3,

A. 479-80, 233). Since the contract had no provision for posting

job vacancies or for any other formal method of informing em

ployees of particular job opportunities, it left black employees

totally dependent on a word-of-mouth network emanating, of course,

from Albemarle’s white supervision and management, for informa

tion about job openings for which they might apply (A. 241-242).

14 The court noted that blacks occupied the bottom 25 job posi

tions in the “integrated” Woodyard. The same chart shows that

whites occupied the top 26 positions (A. 485-6).

15 Thus, the black Brokeman LOP in the A Paper Mill was tacked

on to the bottom of the short and relatively low-paying white

Beater Room LOP but remained cut off from the high-paying A

Mill Paper Machine LOP (compare A. 109, 110). In the Woodyard,

the separate black Chipper Crew “dovetailed” into the white Crane

Operator LOP with the result that only one black job (Chipper

Operator #2 ) was placed ahead of a single white job (Chain

Operator) ; all other blacks remained behind all other whites,

11

functional standpoint,16 they did little to overcome the isola

tion of black employees in inferior positions.

The 1968 merger of segregated extra boards preserved

the pre-existing patterns of segregation. Although em

ployees could thereafter move from the merged extra board

into any LOP (subject to test, educational, and qualifica

tions requirements), recall priority for a particular LOP

was reserved to employees who had previously worked in

that LOP during the time of strict segregation (A. 486).

As the district court found, “ [t]he effect of this practice is

that black employees are recalled to black jobs and white

employees are recalled to white jobs” (id.).

The income disparity between white and black workers

under the regime described above was substantial. The all

black LOPs were among the lowest paying in the mill; the

all-white LOPs were among the highest paying; and in

locked in job seniority order (id.). A separate Service Department

was established by removing the black Service Crew LOP from

the Woodyard and placing it beneath the black Payloader job

from the Pulp Mill; no blacks gained access to any white jobs

by this move (id). The Pulp Mill Department underwent sub

stantial changes, without benefit to that department’s black em

ployees. The white Ivamyr Operator job was removed from the

white Digester LOP and placed at the top of the black progression

leading to Lift Truck Operator (compare A. 109, 110, A. 481-2) ;

however, within a few months the Kamyr was shut down, depriving

blacks of access to that job (A. 245). A number of other positions

(Bark Burner, Boiler Operator) were removed to another depart

ment, the Boiler Room, and there consolidated with the existing

Fireman LOP (compare A. 109, 110) ; but there is no evidence

that these black jobs were then staffed (see A. 481-4), and even

if so, they were placed beneath the white jobs brought into their

department (A. 109).

16 The record clearly shows, Albemarle’s protestations notwith

standing (Br. 5), that departments such as the Pulp Mill and the

A Paper Mill were not organized into functionally related LOPs

before the 1968 mergers. See A. 231-2. Race may well have been

the reason behind the non-functional LOPs.

12

racially mixed departments the white employees’ wages

greatly exceeded the blacks’ wages.17

P ro c ee d in g s B elow

The proceedings in this case took place against the back

ground of the historical discrimination practices described

above. Plaintiffs filed their charges before the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”) on May 9,

1966 (A. 273-285) and their complaint on August 25, 1966

(A. 6-10). Defendants immediately filed motions to dis

miss and for summary judgment challenging, inter alia, the

maintenance of the class action (A. 1). In response to one

of those motions and in reliance on newly amended Rule

23(b)(2), F.R.Civ.P., and the only then-existing precedent

17 The following table, based on the job composition data at

A. 481-5 and the hourly wage rates for June 30, 1967 shown at PL

Ex. 14, App. A, pp. 34 et seq., graphically shows the disparities:

Segregated LOPs & Departments

No. o f

Name # Mace Employees Avg. Wage

1. Woodyard Service Crew--Black 11 $2.45/hr.

2. A Mill Finishing—Black 5 2.47/hr.

3. Technical Service—White 23 (1 B) 2.5 8/hr.

4. .Storeroom—White 3 2.79/hr.

5. Power Plant—White 16 2.94/hr.

6. Maintenance—White 138 (1 B) 3.42/hr.

7. Boiler Room—White 4 3.63/hr.

Racially Mixed LOPs and Departments

Macial Average Average

Name Breakdown Black Wage W hite Wage

1. Pulp Mill 7B 57W $2.38/hr. $3.08/hr.

2. B Paper Mill 6B 69W 2.40/hr. 3.24/hr.

3. B Mill Product 5B 70W 2.40/hr. 2.56/hr.

4. A Paper Mill 6B 48W 2.42/hr. 2.71/hr.

5. Woodyard Yard Crew 26B 34W 2.43/hr. 3.21/hr.

13

on Title VII class actions, Hall v. Werthan Bag Co., 251

F. Supp. 184 (M.D. Tenn. 1966), plaintiffs filed a memo

randum stating that no back pay was sought “for any mem

ber of the class not before the court” (A. 11-14). This posi

tion was based on the belief that, “It may well be that any

employee seeking separate and specific relief such as an

individual promotion should first address his claim to the

[Equal Employment Opportunity] Commission” (A 14).18

In October, 1968, several of the corporate defendants ex

ecuted a “corporate reshuffle” (A. 35) in which the mill’s

assets and liabilities changed hands (A. 31-34, 41-42).

Thereafter, on September 29, 1970, the district court

granted plaintiffs’ motion to join the successor and parent

corporations of the initial defendant company (A. 38-39).

In its ruling, the Court noted that Rule 54(c), F.R.Civ.P,,

required it to grant plaintiffs all relief to which they were

entitled, whether specifically pleaded or not, and that the

back pay issue was “litigable” (A. 38). Plaintiffs’ claim

for back pay had in fact been explicitly stated to counsel

for Albemarle in a telephone conversation on April 8,

1970.19 Albemarle’s counsel indicated his awareness of the

claim in a letter to the Court dated June 12, 1970 (A. 29).

On March 8, 1971, this Court handed down Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., supra. Albemarle thereupon retained a

18 That possibility was subsequently rejected by the courts, see

Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1968) ;

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 417 F.2d 1122 (5th

Cir. 1969); Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th

Cir. 1969).

19 See “Memorandum of Counsel for the Defendant ‘Old’ Albe

marle Paper Company,” filed August 17, 1970, p. 9 [not reproduced

in Appendix],

This was just over 3% years after suit was brought, rather than

5 years as the district court stated in denying back pay (A. 498).

This notice came well over 15 months before trial began.

14

testing expert, Dr. Joseph Tiffin, to perform a validation

study of its test battery in the few months remaining be

fore trial (A. 489). Dr. Tiffin began to work on the study

in April or May of 1971 (A. 185-6) and produced his re

port (A. 431-8) just in time for trial in July, 1971. The

Tiffin report concluded that both the Beta and the Wonder-

lie A tests could properly be used as Albemarle was using

them (A. 438, 491, 171). The conclusion was based on a

correlation analysis which purported to demonstrate that

at least one of Albemarle’s three tests was significantly

related to performance on nine of ten job groups studied

(A. 431, 491). Dr. Tiffin conducted his study by the “con

current criterion-related validation” method (A. 490). He

selected and grouped jobs from the middle to upper range

of 10 LOPs in five different departments (A. 432-7). All

employees in those job groups, except a few who refused,

took the tests for correlation purposes (A. 490, 186). These

employees’ supervisors were asked to rate their job per

formance (A. 490, 187). No separate study was made of

correlations between test scores and job performance of

black employees.

In the months before trial the district court entered a

series of orders related to case management and the class

action. On June 15, 1971, the court defined plaintiffs’ class

and “reserved ruling” on whether it could recover back pay

(A. 46-7). On June 18, 1971, the court entered an order

barring all parties and their counsel from communicating

directly or indirectly with class members during the period

when they received notice and when final trial preparation

took place (A. 48-9). On July 8, 1971, the court held that

back pay could be. awarded under Robinson v. Lorillard

Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed 404

U.S. 1006 (1971), and directed that notice be given to class

members requiring them to file a written “proof of claim”

15

as a precondition to individual recovery (A. 50-51, 55-56).20

A total of 80 employees signed “proof of claim” forms

bringing their back pay claims “before the court” (A. TO

SS).

After trial, on November 9, 1971, the district court

entered findings of fact, conclusions of law, and judgment.

The court held that defendants’ seniority system both be

fore and after the 1968 revisions had perpetuated the

effects of past discrimination and was not required by

“business necessity” (A. 495-497). Accordingly, the court

decreed substitution of a plant seniority system with job

posting, red-circling, and minimum residency periods (A.

499-502). The court also held unlawful Albemarle’s high

school education requirement and permanently enjoined

its use (A. 497, 502).21 However, the district court examined

the test battery for job-relatedness and concluded that it

had been adequately validated and was, therefore, per

missible under Title YII (A. 497, 495). Finally, the court

allowed no back pay (A. 502). It recited three reasons for

denying plaintiffs’ claim: that Section 706(g) of Title YII,

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g), vests the district court with dis

cretion to withhold back pay; that Albemarle had exhibited

good faith in attempting (unsuccessfully) to comply with

the Act; and that plaintiffs’ allegedly late assertion of their

back pay claim might have prejudiced defendants (A.

497-8).

20 The notice provided that failure to file “proof of claim” by

July 22, 1971, four days before trial, would cause claims to be

“forever barred” (A. 56).

Plaintiffs thereupon moved for leave to communicate with class

members for purposes of trial preparation (A. 57), for clarification

of the “opt-in” notice provisions (A. 64), and for severance of

back pay proceedings from the initial determination of liability

(A. 68). The court did not rule on these motions.

21 There was no appeal from these two aspects of the court’s

ruling.

16

The Court of Appeals reversed in plaintiffs’ favor on

both the testing and back pay issues (A. 511-524). The

Court’s opinion held both that the testing program had

an adverse impact on black employees and that Albemarle

had failed to prove it demonstrably job-related as required

by Griggs (A. 513-520). The Court further held that the

purposes of Title VII require that back pay be awarded to

compensate for wages lost due to discrimination, in the

absence of “special circumstances that would render such

an award unjust” (A. 520-524), and that no such circum

stances appeared in this record (A. 524).

Summary of Argument

1=

This Court’s decision in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

U.S. 424 (1971), controls the question of whether the use of

various tests to determine promotions violated the Title

VII rights of black employees. The Court of Appeals

properly held that all of the tests used disproportionately

excluded blacks from formerly white jobs. The Company,

on the other hand, failed to meet the burden imposed by

Griggs to demonstrate “a manifest relationship to the em

ployment in question.” In particular, Albemarle did not

present sufficient proof that the tests were in fact accurate

predictors of job performance, or that they had been

validated pursuant to the guidelines established by the

Equal Employment Opportunit[y] Commission and en

dorsed by this Court in Griggs. In contending that the

guidelines should not be followed, Albemarle is asking this

Court to overrule its well-reasoned opinion in Griggs, and

to reject the consistent reliance of lower courts on that

decision. The Court should reaffirm that the guidelines,

17

which incorporate accepted professional standards, provide

the proper standards that should be met by employers in

using tests that may deny equal opportunity to blacks and

affirm the Fourth Circuit’s application of Griggs in this

case. Accordingly, the use of these unlawful tests was prop

erly enjoined in order to prevent the continued denial of

promotional opportunities to black employees.

II.

All Courts of Appeals ruling on the issue have held that

Title YII authorizes an award of back pay to the members

of the class of black (or other minority) employees ad

versely affected by discriminatory employment practices.

The legislative history of the 1972 amendments to Title VII

make it clear that Congress intended that such relief be

available. Thus, a House provision that would have re

stricted the availability of back pay was rejected by the

Senate and the Senate’s position was adopted by the Con

ference Committee. The rejection of class back pay by this

Court is thus unwarranted and would result in the substan

tial weakening of Title VII as an effective remedy against

employment discrimination.

This Court should hold that back pay should be awarded

to a class that has established a violation of Title VII un

less special circumstances would render such an award

unjust. This standard has been adopted by the Fourth,

Fifth, and Sixth Circuits. It will ensure the effectuation of

the Act’s purpose, viz., to ensure that persons economically

harmed by discrimination will receive restitution. Only if

the victims of racial discrimination obtain the most com

plete relief possible, as do victims of unfair labor practices

under the N.L.R.A., will the Congressional purpose be ful

filled. The standard does not, however, mean that district

courts will have no discretion. Rather, there are instances

18

in which a denial of back pay may be justified; there is

broad discretion in determining appropriate methods for

calculating the amount of back pay and in the allocation of

liability between defendants. Thus, the standard enunciated

by the Court of Appeals is fully consistent with this Court’s

discussion of back pay in Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189

(1974), and with the holding regarding the award of at

torneys’ fees in Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390

U.S. 400 (1968). Finally, the facts of the present case do

not present the kind of special circumstances that would

justify a failure to award back pay.

A R G U M E N T

I.

Albemarle’s Testing Program Is Unlawful Under

Griggs v. Duke Power Company.

In this case the Court must apply principles first enun

ciated in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

The facts concerning the tests involved here and their

usage by Albemarle are closely similar to those in Griggs,

see supra pp. 4-6. While Griggs provides the point of

departure, it does not specifically answer the questions

presented here. In Griggs, the employer had not attempted

an empirical demonstration of the tests’ job-relatedness

but relied on their having been “professionally developed,”

cf. 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h). Here, the employer has gone

one step farther by conducting a correlation analysis

purporting to show that its tests accurately predict job

performance.

This case is controlled by Griggs principles despite the

superficial difference in its factual context. Close scrutiny

of the results of Albemarle’s validation study demon-

39

strafes that they fail to prove the test battery “manifestly

job-related” in a majority of cases; therefore, here as in

Griggs, the employer’s test is unvalidated (part B.l, infra).

Moreover, the Company’s validation procedures were so

inadequate that even those results cannot be credited; there

fore, the employer has failed to carry its burden of show

ing its tests “manifestly job-related” (part B.2, infra).22

The significance of this case for the future of employ

ment testing litigation in the post -Griggs era is plain. If

Albemarle met its Griggs burden, then that case requires

little more than a pro forma exercise submitted to the

district court over the signature of a certified industrial

psychologist.23

A. T he Tests Adversely Affect B lack Em ployees.

Albemarle’s tests disproportionately screen out black

employees from higher paying jobs. The Company does not

deny that the statistical evidence shows a higher average

23 Both Albemarle and amicus curiae American Society for Per

sonnel Administration have sought to inject an issue concerning

the requirement of “differential validation,” see 29 C.F.R. § 1607.4

(a) (A. 309), in this case. Co. Br. at 41, ASPA Br. at 28-30.

They seek an advisory opinion. The district court found that such

study in this case was “technically infeasible,” cf. 29 C.F.R. § 1607.4

(A. 309). This was not an issue on appeal and is not before the

Court.

23 Albemarle’s widely used Wonderlic test has never survived full

judicial scrutiny in an employment discrimination ease. Every

appellate decision to pass on Wonderlic has held it unlawful in

that it adversely affects black job candidates and has not been

shown to be job-related. See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

U.S. 424 (1971) ; Rogers v. International Paper Co., supra; John

son v. Goodyear Tire & P uller Co., 491 F.2d 1364, 1372-3 (5th

Cir. 1974) ; Young v. Edgcombe Steel Co., 499 F.2d 97, 98 (4th

Cir. 1974). The Company would justify using this test on the basis

of little more than its expert’s say-so, see part B, infra.

20

score for whites than for blacks on both tests.24 Moreover,

these average scores understate the black-white disparity

because they do not take into account the large number of

black employees who failed the tests but whose numerical

scores were not recorded.26 The district court found that

when Albemarle administered the tests to incumbent black

employees in 1964-5, “a majority of those who took the

tests failed them” (A. 488).26a Furthermore, the district

court found that the “skilled” LOPs and General Extra

Board, for which the tests were required, remained

“essentially segregated because of the inability of black

employees to meet the educational and testing require

ments” (A. 496).

Plaintiffs’ expert witness, Dr. Raymond Katzell, testified

that blacks generally score lower than whites on paper and

pencil examinations; the reasons for this phenomenon are

24 Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 10 shows that whites averaged over 7 points

higher than blacks on the Wonderlic test, as Albemarle concedes,

Br. at 29. Albemarle also does not dispute the existence of a dis

parity of over 3 points in test scores on the Beta examination, id.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 10 and 73 [not printed in Appendix] list the

available test scores of Albemarle’s employees.

25 Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 10 lists 12 black employees who failed the

tests, without giving their scores. This number amounts to nearly

half the number of blacks (15), whose scores were averaged; of

those 15, only 3 failed. Thus, the average scores omit 80% of the

blacks who did not pass. The averages also exclude the scores of

at least 12 whites, listed only as “OK” on the tests, whose scores

were apparently passing. This listing does not indicate whether

unsuccessful employees failed the Wonderlic, the Beta, or both.

However, it is pertinent that every black employee whose scores

appear on Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 10 either failed both tests, or passed

both.

26a This is confirmed by the data on Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 10, see

n.25, supra, showing that of 27 blacks with recorded results 15

(56%) failed the test battery. By contrast, the exhibit shows that

of whites with scores or test success indicated, 90% passed the

Beta and over 95% passed the Wonderlic.

21

unclear but are thought to include inferior schooling26 and

the reaction of black test takers to examination situations

(A. 1382-3, 493). Dr. Katzell recalled data showing that

blacks usually score less wTell than whites on intelligence

tests similar to the Beta (A. 406). Significantly, neither

Albemarle’s expert witness nor the Company itself, which

had full access to all test scoring data, made any attempt

to introduce evidence or opinion that blacks were not dis

proportionately screened out by Albemarle’s tests or by

written examinations generally. On this showing, the Court

of Appeals held that “ [t]he plaintiffs made a sufficient

showing below that Albemarle’s testing procedures have a

racial impact,” 474 F.2d at 138 (A. 515).27

The federal courts in employment discrimination cases

have repeatedly found that tests like those used by Albe

marle have an adverse impact on black job applicants. In

particular, this Court and lower courts have consistently

found that the Wonderlic test screens out blacks.28 Re-

26 Cf. Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra, 401 U.S. at 431.

27 The Court of Appeals also referred to a study, Negro Norm-s,

A Study of 38,452 Job Applicants for Affirmative Action Programs

(1972), published by E. F. Wonderlic Associates, Inc. The study

became available only after trial and was lodged with the Court

of Appeals during briefing. I t shows a median black score of 15

on the Wonderlic and a white median of 23 (pp. 11, 13).

28 See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra, 401 U.S. at 430

(Wonderlic) ; Rogers v. International Paper Co., supra, 9 EPD at

p. 6592 (Wonderlic) ; Pranks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 495

F.2d 398, 412 (5th Cir. 1974), cert, denied 42 L.Ed.2d 644 (1974)

(“the race-oriented Wonderlic”) ; Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rub

ber Co., 494 F.2d 817, 818-819 (5th Cir. 1974) (Wonderlic) ;

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364, 1372 (5th

Cir. 1974) (Wonderlic) ; United States v. Georgia Poiver Co., 474

F.2d 906, 912 n.5 (5th Cir. 1973) ; United States v, Jacksonville

Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418, 455-6 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied

406 U.S. 906 (1972); Young v. E’dgcombe Steel Co., 499 F.2d 97,

98, 100 (4th Cir. 1974) (Wonderlic); Brito v. Zia Co., 478 F.2d

1200, 1203 (10th Cir. 1973) ; Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 365

22

spondents are not aware of any reported final decisions in

which tests like Albemarle’s were fonnd to be without ad

verse racial effect.29 The other cases, therefore, confirm

what this record shows: at Albemarle as elsewhere, written

examinations typically operate as powerful “built-in-head-

winds” to black employees, cf. Griggs, supra, 401 U.S. at

432.

This Court’s ruling in Griggs was based on far less evi

dence of adverse racial impact than is presented here. The

record in Griggs contained no evidence of actual test scores;

rather, the Court properly assumed that the general ob

servation of racial disparities would hold true, as plaintiffs’

expert had testified, 401 U.S. at 430 n.6.s0

F. Supp. 87 (E.D. Mich. 1973), aff’d in pert, part sub. nom. EEOC

v. Detroit Edison Co.,----- F .2d------ (6th Cir. No. 74-1007, March

11, 1975).

The same finding of adverse impact has consistently held true

in the case of written civil-service examinations of public em

ployers. See, e.g., Douglas v. Hampton,----- F.2d.------ (D.C. Cir.

No. 72-1376, Feb. 27, 1975) ; Davis v. Washington, —— F .2d-----

(D.C. Cir. No. 72-2105, Feb. 27, 1975) ; Castro v. Beecher, 459

F.2d 725, 729 (1st Cir. 1972) ; Boston Chapter N.A.A.C.P., Inc.

v. Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017, 1019-20 (1st Cir. 1974) ; Chance v.

Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167, 1171 (2nd Cir. 1972) ; Bridge

port Guardians, Inc. v. Civil Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333,

1335 (2nd Cir. 1972) ; Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. O’Neill,

348 F. Supp. 1084, 1089-90 (E.D. Pa. 1973), aff’d. in pert, part 473

F.2d 1029 (3rd Cir. en banc 1973) ; Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d

315, 323 (8th Cir. 1972), upheld 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir. en banc),

cert, denied 406 U.S. 950 (1972).

29 Stevenson v. International Paper Co., 352 F. Supp. 230 (S.D.

Ala. 1972), on appeal 5th Cir. No. 73-1758 (same testing program

as in Rogers v. International Paper Co., supra), and Watkins V.

Scott Paper Co., 6 EPD 8912 (S.D. Ala. 1973), on appeal 5th

Cir. No. 74-1001, are both being appealed on this issue.

30 As Judge Friendly recently observed, “complete mathematical

certainty” of proof should not be required on this issue, particu

larly since a showing of adverse impact “simply places on the

dependants a burden of justification which they should not be

23

Albemarle’s assertions that there was “absolutely no

evidence” of the Beta’s disparate effect (Br. at 29), and

“deficient” proof as to that of the Wonderlie (Br. at 30),

ignores the many uncontradicted indications summarized

above. Likewise the Company’s charge that the adverse

impact issue never arose in the district court is mistaken.

The district court knew that under Griggs it need not have

reached the issue of job-relatedness unless it found adverse

impact. The court concluded that testing practices blocked

black employes from the white lines of progression (A. 488,

496). Therefore, the court proceeded to examine the vali

dation evidence as Griggs requires (A. 489-91).

There is no basis for this Court to reverse the well-sup-

ported finding below that Albemarle’s testing program

tended to exclude black workers.

B. A lbem arle Failed to Prove the Job-Relatedness of

Its T esting Program .

Because Albemarle’s tests disqualify blacks at a higher

rate than whites, the Company must show that the tests

have “a manifest relationship to the employment in ques

tion,” Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra, 401 U.S. at 432.

The Company attempts to meet that burden primarily by

reliance on an empirical correlation analysis performed

after the Griggs decision in the Spring of 1971.31 That

unwilling to assume,” Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Commission,

490 F.2d 387, 393 (2nd Cir. 1973). See also, Rogers v. Interna

tional Paper Co., supra, 9 EPD at p. 6592; Boston Chapter NA A CP,

Inc. v. Beecher, supra, 504 F.2d at 1021; Douglas v. Hampton,

supra, slip op. at 8-13.

31 Albemarle also suggests two further bases for a finding of

job-relatedness, but these arguments are insubstantial.

First, it argues that the tests are job-related because they were

designed to measure intelligence and reading ability, which were

found to be necessary for successful performance in skilled LOPs

(Br. 32-33). But this tautological reasoning begs the question which

24

validation study will not support a finding of job-related-

ness.32

1. R esu lts Show ing Lack o f Job-R elatedness.

Albemarle’s own validation study demonstrates that the

tests are not job-related for most of the jobs for which

they are required. Albemarle’s expert, Dr. Tiffin, attempted

to validate each of three tests for each of ten job group

ings. The groups came from 8 LOPs in 5 departments

(A. 514). He reported, and the district court found,

statistically significant correlations between job perform

ance and test scores on one or another of the three tests in

nine of the ten job groups (A. 431, 491). Such correlations

were found for all three tests in only one of the ten groups

( # 4); and, for the Beta and either Wonderlic A or Won-

derlic B,33 in only one other group (#8) (A. 432). In eight

of the ten groups, Dr. Tiffin did not find a significant cor

relation for both the Beta and a Wonderlic test; in three

groups ( # s 1, 2, 5) he found only one of the three tests

Griggs frames: apart from the employer’s purpose in utilizing the

tests, is there convincing proof that the tests actually do measure

ability to perform the job?

Second, it adverts to a purported validation study of the Beta

test in 1958 (Br. at 33). The unwritten results of this study,

which were described in conclusory terms (see p. 5, supra), are

surely inadequate to meet the employer’s burden of proof. And

Albemarle made no effort to validate the Wonderlic test when

introduced or thereafter, until 1971.

The district court relied on neither argument. Its holding of

job-relatedness was based on the 1971 study.

82 Technical terms encountered in the discussion of Albemarle’s

purported demonstration of job-relatedness are defined or described

in an Appendix to this brief, “Glossary of Technical Terms Relevant

to the Testing Issue.”

33 Test success on the Beta and either Wonderlic A or Wonderlic

B is Albemarle’s selection criterion, see p. 5, supra.

25

job-related; and in one group (#6) be found none of tbe

tests had significant predictive value {id.)}*

Thus, for 80% of the job groups studied, Albemarle’s

two-test battery, as used, was not found job related. This

fact alone is dispositive. As the Court of Appeals held, “it

was also error to approve requiring applicants to pass two

tests for positions where only one test was validated” (474

F.2d at 140; A. 519). Of. United States v. Georgia Power

Go., supra, 474 F.2d at 916-7.

A close reading of the correlation data for particular

tests casts further doubt on the conclusion Dr. Tiffin drew

from the results. In ten correlations of the Beta test, he

found only three statistically significant relationships, six

correlations not deemed scientifically significant, two per

fectly random correlations,36 and one negative correlation.36

Moreover, the study finds notable discrepancies between the

34 Dr. Tiffin’s results are summarized in the following table in

terms of whether statistically significant correlations were found:

Job Group Statistically Significant Correlations ?

[by number] Beta W-A W-B All 3 B plus W (A orB)

1 No Yes No No No

2 Yes No No No No

3 No Yes Yes No No

4 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes