Ford v. United States Steel Corporation Supplemental Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 17, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. United States Steel Corporation Supplemental Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1975. b448bc2d-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aa61900a-9186-4288-b6ef-515d171bc474/ford-v-united-states-steel-corporation-supplemental-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

__ Ô â e.

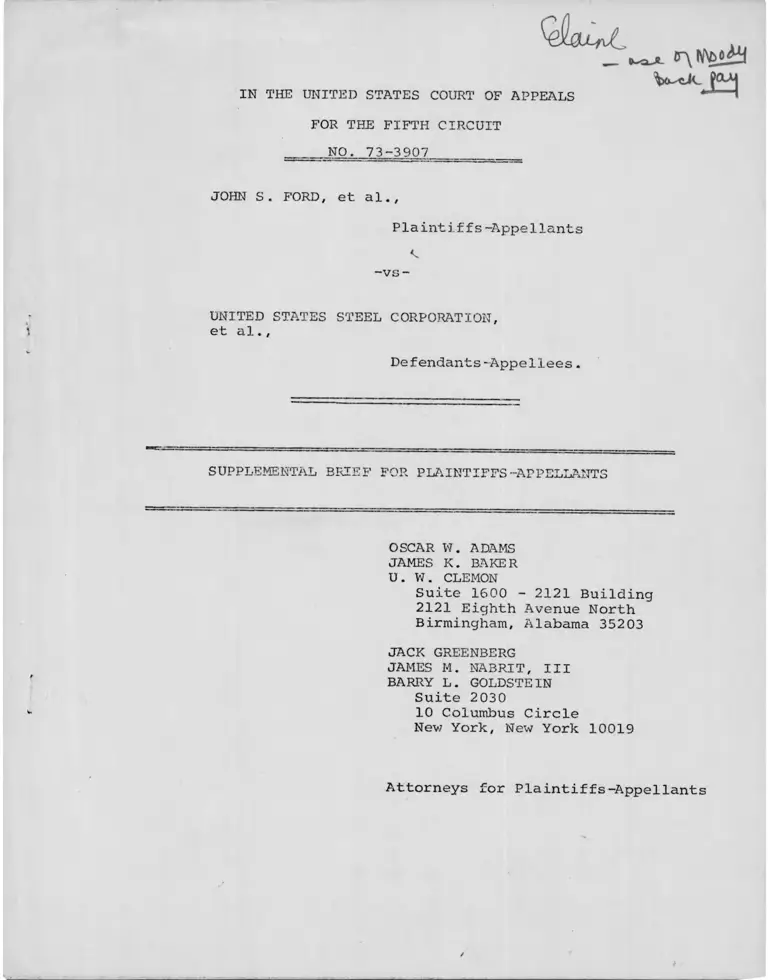

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

CPy(\|N^0^1

W u c J ^ j

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-3907________

JOHN S. FORD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

k

-vs-

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APP r»O

OSCAR W. ADAMS

JAMES K. BAKER

U. W. CLEMON

Suite 1600 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABR.IT, III

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

Nev7 York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ........................ i

BRIEF ....................................... 1

CERTIFICATE

Table of Authorities

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, Nos. 74-389 and

74-428, 43 U.S.L.W. 4880, 9 EPD

para. 10, 230 (June 25, 1975) .......... Passim

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Company,421 F. 2d 888 (5th Cir., 1970) .......... 2

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .... 4

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d

714 (5th Cir. , 1974) ................... 2

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d

1364 (5th Cir., 1974) .................. 2

Miller v. International Paper Co., 408 F.2d

283 (5th Cir., 1969) ................... 2

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d

211 (5th Cir., 1974) ................... 2, 3, 4

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

No. 74-3056 (5th Cir., appeal pending) 3

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d

906 (5th Cir., 1973) ................... 3

United States v. Hayes International, 456 F.2d

112, (5th Cir., 1973) .................. 3

United States v. N.L. Industries, 479 F.2d

354 (8th Cir., 1973) ................... 5

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-3907

JOHN S. FORD, et al.,

Plaint iffs-Appellants,

-vs -

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

This supplemental brief is filed pursuant to this

Court's request to discuss the effect of Albemarle Paper Co.

1/v. Moody on this appeal and to respond to the brief submitted

on behalf of the Union defendants-appellees.

The Supreme Court's decision in Moody made emphatic

what this court has repeatedly stated for several years:

when an employer or union has engaged in practices which result

in economic loss to blacks, then back pay is an appropriate

1/ Nos. 74-389 and 74-428, decided June 25, 1975, 43 U.S.L.W.

4880, 9 EPD H10, 230. The citation in this brief refers to

the Slip Opinion.

remedy which should ordinarily be awarded.

It follows that, given a finding of unlawful

discrimination, backpay should be denied only

for reasons which, if applied generally, would

frustrate the central statutory purposes of

eradicating discrimination throughout the

economy and making persons whole for injuries

suffered through past discrimination."^

14/It is necessary, therefore, that if a

district court does decline to award backpay,

it carefully articulate its reasons.

(Slip Opinion at 14) .

The Court's strong statement on backpay is based on

the twofold purpose of Title VII. The first purpose is to

3/"eradicate" discrimination in employment. The Supreme Court

4/stated that backpay in a sense forms a real financial incentive,

a "spur or catalyst", to insure compliance with the fair em

ployment laws. The Supreme Court's analysis adds substantial

strength to the standard established by this Circuit. This

5/Court in the Johnson-Pettway line of cases did not rely on

this argument in establishing the standard for backpay, but

2/

2/ There is no question that the unlawful practice of

defendants resulted in economic harm to the class of black

workers before this Court. Plaintiffs' Reply Brief at 10-15.

3/ This Court has repeatedly recognized this purpose of Title

VII as a necessary guide to judicial decision, see, e.g.,

Miller v. International Paper Co., 408 F.2d 283, 294 (5th Cir.,

1969); Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Company. 421 F.2d 888, 891

(5th Cir., 1970); Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 488 F.2d

714, 716 (5th Cir., 1974).

4/ See Plaintiffs' Brief at 64-66

5/ Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364 (1974);

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Company. 494 F.2d 211 (1974).

- 2 -

rather relied on the Supreme Court's second argument for an

award of backpay — i.e., compensation to the victims of dis-

6/crimination. This additional argument for awarding backpay

serves to strengthen the standard.

The second basic purpose of Title VII which "informs"

courts as to the appropriate standard for awarding backpay is

the "make-whole" purpose: to place the victims of discrimina

tion, through an award of backpay, in the economic position

in which they would have been but for the unlawful employment

practices. The Supreme Court's analysis of this primary pur-

7/

pose is basically the same as this Court's analysis.

To be made "economically whole" from the defendants

unlawful employment practices is precisely what the plaintiff

class seeks in this litigation. It is no answer to this claim,

as the defendants make, that an industry-wide consent decree,

was entered which will afford some class members some money,

see United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, No. 74-3056.

6/ This Court apparently rejected reliance on this ground in

establishing its backpay standard because it looked upon back

pay as essentially "an equitable award for past economic injury

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., supra at 253; but see

United States v. Georgia Power Company. 474 F.2d 906, 919 (5th

Cir., 1973); United States y. Hayes International, 456 F.2d

112, 119 (5th Cir., 1972). Of course, under this Court's

application of its standard there was no need to reach this

argument, since the cases before this Court, like the Ford case

presented instances where unlawful practices had economically

harmed black employees and back pay was necessary in order to

make them whole.

7/ Compare Moody, Slip Opinion at 11-15 with Johnson v. Good

year Tire & Rubber Co., supra at 1376, and Pettway v. American

Cast Iron Pipe Co., supra at 251-53.

- 3 -

There was no determination by the district court, and in

fact there were no facts presented to the district court,

that the backpay to be parcelled out pursuant to the consent

decree satisfies the "make-^whole" requirements of Moody (or

8/Pettway).

It is clear that the Supreme Court's standard in Moody9/

unmistakably rules out the defenses of "good faith" and

"uncertainty in the law" which the district court had erroneously

relied on. In fact, the Supreme Court's ruling on "good faith",

if anything, expands this Court's rejection of "good faith" as

10/

a defense.

It is important to note that the Court applied the

1970 Testing Guidelines of the EEOC to pre-1970 testing

11/

practices of Albemarle Paper Company. (Slip Opinion at 6).

8/ The method of calculation, the period covered or the

method of distribution of the amount remains a mystery.

See Plaintiffs' Reply Brief at 19-23.

9/ The Supreme Court specifically followed the rules established

in NLRA cases, that backpay is appropriate even where the employee

acted in "good faith". Slip Opinion at 15, n.16; see Johnson v.

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, supra at 1377, n.37.

10/ First, the Court stated that if the defendants acted in "bad

faith", then they may make "no claims whatever on the Chancellor's

conscience". Slip Opinion at 15. Second, the Court specifically

did not approve the cases holding that a "good faith" reliance on

a state female protective 'law is a defense to a claim for backpay.

Slip Opinion at 16, n.18; see the concurring opinion of Justice

Blackmun at pp. 2-3 which indicates that the stringent rule of

the majority removing the defense of “good faith" will require

reversal of the female protective law cases.

11/ Of course, the first authoritative judicial decision on

testing was not rendered until 1971, Griggs v. Duke Power

Company, 401 U.S. 424.

-4-

The Supreme Court did not exclude from an award of backpay

the wages lost by blacks who were denied jobs as a result

of Company's unlawful tests. Any denial of backpay because

of the "unsettled state of the law" would directly contravene

the standards established by the Supreme Court. If companies

or unions realized that they could escape backpay because

their precise discriminatory practice had not been judicially

determined unlawful, or applied in the context of their in-

12/dustry, then the award of backpay would hardly provide a

strong "spur or catalyst" to self-reform. Further, if the

"unsettled state of the law" was a valid defense, it would

totally negate the "make•-whole" purpose of Title VII.

12/ The Steelworkers ingenuous argument, that there is

a judicially created exemption from back pay for the steel

industry has been raised again in their Supplemental Brief.

This argument has been fully discussed by the plaintiffs

at pages 16-19 of their Reply Brief. The argument does not need another response here except to respond to one point

raised in the Steelworkers' brief. adoption of some

The Steelworkers argue that the Supreme Court's/language

in United States v. N.L. Industries, 479 F.2d 354, 379 (8th

Cir., 1973) , in Moody (Slip Opinion at 11) indicates that the

Court adopts a totally unrelated substantive position of the

Eighth Circuit: that since the law is not clearly settled

concerning unlawful seniority in that Circuit backpay is in

appropriate. There is no indication that the Supreme Court

in any way approved the position of the Eighth Circuit. The

Steelworkers argument is a unique interpretation of case

citation (the plaintiffs cited N.L. Industries in their

Brief at p . 65).

- 5 -

In conclusion, Moody clearly established a standard

for the award of backpay which when measured against the

clear discriminatory practices at Fairfield Works and the

resulting economic loss suffered by black workers requires

this Court to reverse the district court and remand for an

appropriate determination of back pay designed to make the

13/class economically whole.

Respectfully submitted,

OSCAR W. ADAMS

JAMES K. BAKER

U. W. CLEMON

Suite 1722 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

13/ The Supreme Court approved the award of backpay to a class.

Slip Opinion at 7-8, n.8.

- 6 -

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 17th day of July,

1975, I served two copies of the foregoing Plaintiffs-

Appellants1 Supplemental Brief upon each of the following

counsel of record by depositing copies of same in the

United States mail, adequate postage prepaid.

James R. Forman, Jr., Esq.

Thomas, Taliaferro, Forman, Burr & Murray

1600 Bank for Savings Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Jerome A. Cooper, Esq.

Cooper, Mitch & Crawford

409 North 21st Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Demetrius C. Newton, Esq.

Suite 1722 - 2121 Building

2121 Eighth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Beatrice Rosenberg

Assistant General Counsel

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Office of General Counsel

1206 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20506

Michael H. Gottesman, Esq.

Bredhopf, Barr, Gottesman, Cohen & Peer

1000 Connecticut Avenue

Suite 1300

Washington, D.C.

Robert Moore, Esq.

Department of Justice

Civil Rights Division

Washington, D.C. 20036

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants