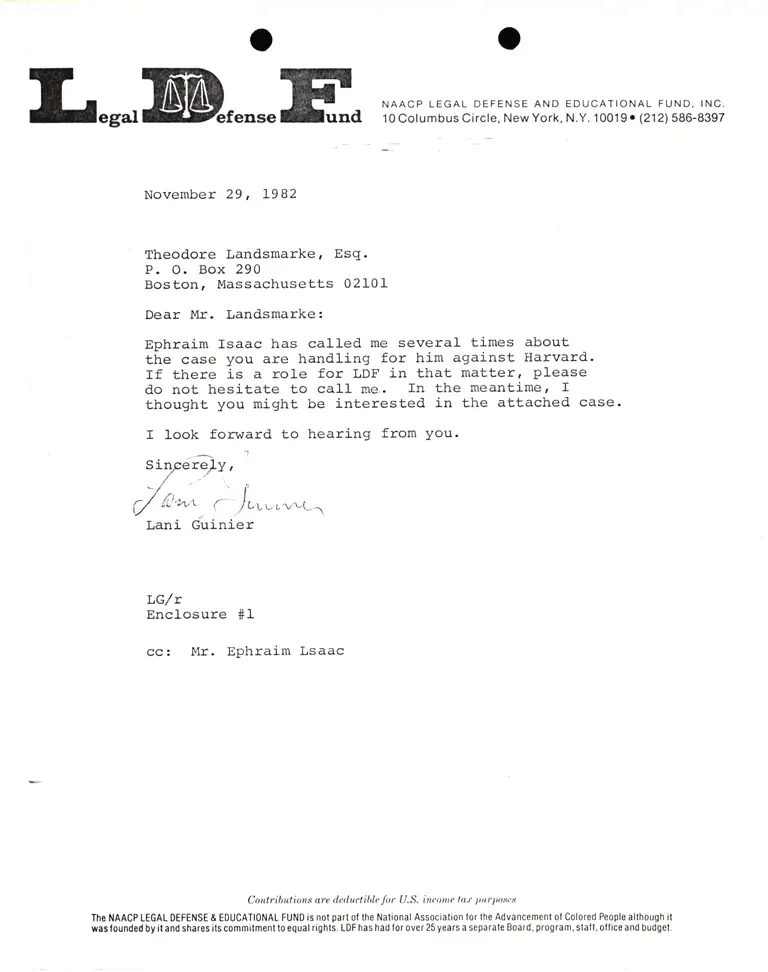

Letter from Lani Guinier to Theodore Landsmarke

Correspondence

November 29, 1982

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Letter from Lani Guinier to Theodore Landsmarke, 1982. 8cd1829d-e392-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aa6fdfda-2b12-4ce2-a2cd-bed5a5e3b884/letter-from-lani-guinier-to-theodore-landsmarke. Accessed March 06, 2026.

Copied!

Lesar@renseH.

November 29, L9B2

Theodore Landsmarke, Esq.

P. O. Box 290

Boston, Massachusetts 02101

Dear Mr. Landsmarke:

Ephraim Isaac has called me several times about

the case you are handling for him against Harvard.

If there is a role for LDF in that matter, please

d.o not hesitate to call me.. In the meantime, I

thought. you might be interested in the attached case.

I look forward to hearing from You.

a

sLnp,exely,

/ ..

1/ rl'n" r )lrr.uuw,u.(--,

Lani Guinier

LG/r

Enclosure #I

cc: Mr. Ephraim Lsaac

Contrihutions are daductililr lor tl.S, inutntr tur l)ttr1tos(:t

The NAACP LEGAL oEFENSE & EDUCATIoNAL FUND is not part ol the National Association lor the Advancement ol Colored People although it

was lounded by it and shares its commitment lo equal rights. LDF has had lor over 25 years a separate Board, program, stall, ollice and budgel.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUNO, INC.

l0Columbus Circle, NewYork, N.Y. 10019 o (212\ 586-8397